- Travel/Study

BIBLE HISTORY DAILY

The origins of judaism.

When did the laws of the Torah become the norm?

Public ritual bath from the Herodian fortress at Masada, and the origins of Judaism. The massive emergence of similar pools across Judea, in accordance with the purity laws of the Torah, corresponds with the origins of Judaism in the mid-second century BCE. Photo by Talmoryair, CC BY 3.0 .

Where can we situate the origins of Judaism? If we were able to travel back in time, would we find ancient Israelites and Judeans following the laws of the Torah during the First Temple period? Almost certainly not, claims Yonatan Adler in his recent scholarly book and a popular article that was just published in the Winter 2022 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review . So, what about during the Babylonian Exile (sixth century BCE), which is when many biblical scholars date the completion of the Torah? In his article “ The Genesis of Judaism ,” Adler asserts that even at this later date, most ordinary Judeans were not yet following the laws of the Torah. What does this mean for the origins of Judaism?

Become a Member of Biblical Archaeology Society Now and Get More Than Half Off the Regular Price of the All-Access Pass!

Explore the world’s most intriguing biblical scholarship.

Dig into more than 9,000 articles in the Biblical Archaeology Society’s vast library plus much more with an All-Access pass.

The Genesis of Judaism

For millennia, Jewish identity has been closely associated with observance of the laws of the Torah . The biblical books of Deuteronomy and Leviticus give numerous prohibitions and commandments that regulate different aspects of Jewish life—from prayers and religious rituals to agriculture to dietary prescriptions and ritual bathing. It stands to reason that the moment when people in ancient Judea recognized these laws as authoritative would mark the origins of Judaism.

As Adler discusses, however, even the Bible itself presents a somewhat different picture:

Ancient Israelite society is never portrayed as keeping the laws of the Torah. The Israelites during the time of the First Temple are never said to refrain from eating pork or shrimp, from doing this or that on the Sabbath, or from wearing mixtures of linen and wool. … Nor is anybody ever said to wear fringes on their clothing, to don tefillin on their arm and head, or to have an inscribed mezuzah on the doorposts of their homes. Whatever it is that the biblical Israelites are doing, they do not seem to be practicing Judaism!

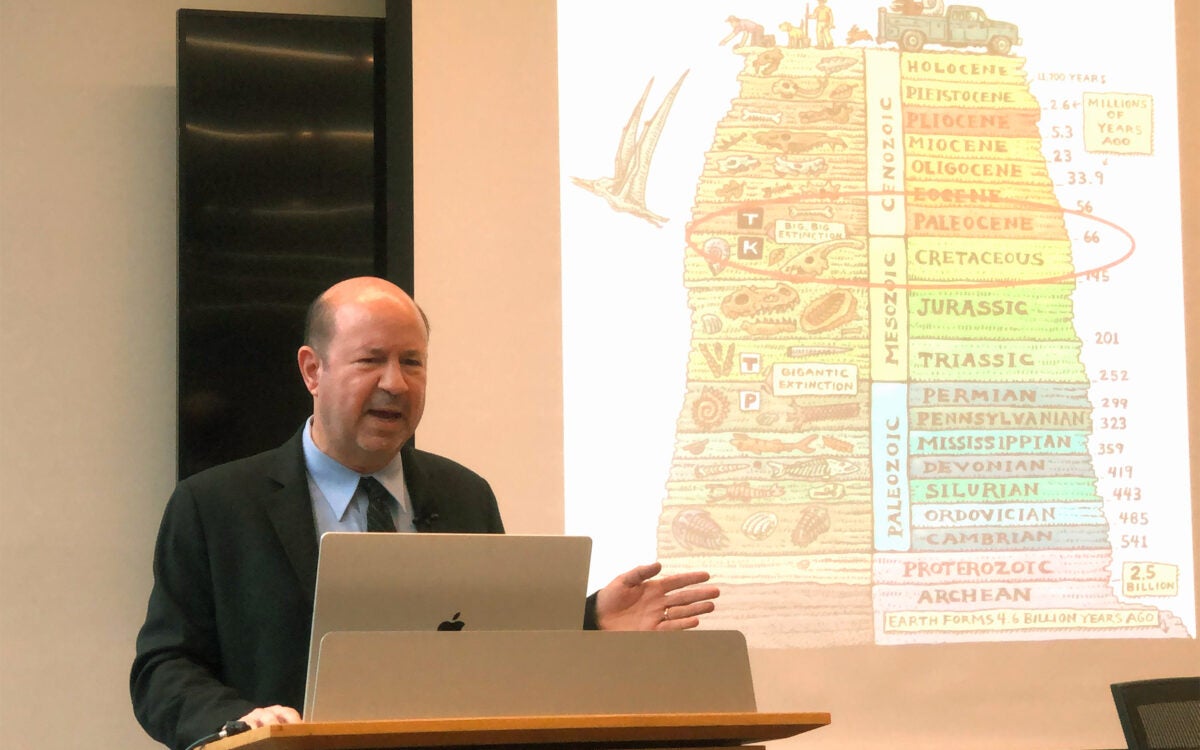

So, when can we date the actual origins of Judaism? Or, as Yonatan Adler puts it: “When did ancient Judeans, as a society, first begin to observe the laws of the Torah in their daily lives?” To answer this question, Adler looks at the archaeological evidence for widespread observance of the laws of the Torah. He suggests that our inquiry begin in the first century CE, where we have plenty of evidence. He then goes backward in time, until he reaches a point when we can no longer see material traces of typical Jewish religious and ritual practices.

The Judean community on Elephantine, in southern Egypt, produced a wealth of documents in Aramaic, including this adoption contract from October 22, 416 BCE. They provide clues also about observance (or not observance) of the laws of the Torah. Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Theodora Wilbour, from the collection of her father, Charles Edwin Wilbour.

In particular, Adler traces archaeological imprints of the biblical laws addressing dietary prohibitions, ritual purity, graven images, tefillin and mezuzot , and Sabbath observance. In every instance, the trail of archaeological evidence ends in the mid-second century BCE—moving the origins of Judaism several centuries later than even the most critical scholars previously thought.

Surprisingly, textual sources from Babylon and Egypt, including this letter from the island of Elephantine, reveal that fifth-century BCE Judeans did not celebrate Passover at a set date, were not aware of a seven-day week or the Sabbath prohibitions, and that they sometimes prayed to deities other than Yahweh.

Widespread observance of the ritual purity laws , as attested through ritual baths (later known as mikva’ot ) and the use chalk vessels, is strong in the first century BCE but gradually disappears as we look further back in time past the late second century BCE.

When it comes to the biblical command against graven images (Deuteronomy 5:8), we can see that during the Persian period even the high priests were issuing coins with depictions of human and animal figures. The pictured silver coin from around 350 BCE bears, on its obverse, a crude depiction of a human head. The reverse features a standing owl with the feathers of the head forming a beaded circle. The Hebrew inscription reads “Hezekiah the governor,” referring to the governor of the Persian province of Yehud (Judea).

Persian-period Yehud coin, from c. 350 BCE. The presence of graven images contradicts the laws of the Torah. Photo by Classical Numismatic Group, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons.

Only a century later, in the Hasmonean and Herodian periods, Judean leaders consciously refrained from using figurative imagery, which they replaced with decorative elements and more extensive texts—apparently adhering to the pentateuchal prohibition against graven images. Instead, the pictured bronze prutah of John Hyrcanus I from the late second century BCE features, on the reverse side, two cornucopias adorned with ribbons, and a pomegranate between them. Its obverse bears a lengthy Old Hebrew inscription inside a wreath that reads, “Yehohanan the High Priest and the Council of the Judeans.”

Hasmonean coin of John Hyrcanus I, from the late second century BCE. The absence of any human or animal figures seems to signal widespread acceptance of the laws of the Torah and to herald the origins of Judaism. Photo in public domain.

In sum, the archaeological evidence for observance of the laws of the Torah in the daily lives of ordinary Judeans seems to situate the origins of Judaism around the middle of the second century BCE.

To delve into the intricacies of the textual and archaeological evidence for widespread observance of the laws of the Torah and the origins of Judaism, read Yonatan Adler’s article “ The Genesis of Judaism ,” published in the Winter 2022 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review .

—————— Subscribers: Read the full article “ The Genesis of Judaism ” by Yonatan Adler in the Winter 2022 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review .

Read more in Bible History Daily:

Original Maimonides Manuscript Goes Digital

All-Access Subscribers, read more in the BAS Library:

Biblical Law

Related Posts

The Masoretic Text and the Dead Sea Scrolls

By: BAS Staff

On What Day Did Jesus Rise?

By: Biblical Archaeology Society Staff

The Last Days of Jesus: A Final “Messianic” Meal

By: James Tabor

The Exodus: Fact or Fiction?

10 responses.

David Holland said >>Wondering if the rise of the Pharisaic movement was related to the forces driving the revolt<<

I wasn't alive in those days (contrary to what my kids say), and can only say they were the people's choice and party of the common people at least as early as Alexander Yannai ("Jannæus"). But I do know one thing:

The Pharisees were not happy that after the battles were history, the Khasmonayeem ("Hasmoneans") had both the kingship and the priesthood. Previously there was a balance of power: Kings were of the Davidic line, and priests were descendants of Aharon" {Aaron").

Now the priests, labeled "Sadducees" (derived from the ancient high priest Tzadok) controlled both powerful positions. Clashes were inevitable.

The monotheism of Judaism developed the same way as that of Islam by evolving from a polytheistic belief in many gods. Originally both Yahweh & Allah were only one of many different gods in Canaan & Arabia but eventually Yahweh was selected as the sole god to be worshiped just as Mohammed selected Allah to be the sole god when he formed Islam (using tenets and history from Judaism as a guide). This evolutionary path is glimpsed in the Bible when it had been reduced to one male god and one female goddess, Yahweh and Asherah, before Asherah was eliminated by, IIRC, King Josiah.

Baseless unadulterated nonsense! Allah (Satan) was invented around 600 AD and based on an apparent demonic encounter by Muhammad. The worship of Yahweh (God) dates back to the beginning of creation (albeit under some different name probably), certainly long before the entry of the Israelites into Canaan. As a consequence of Joshua’s conquest not eradicating all the Canaanites along with their idolatry, Asherah along with other Satanic idols were eventually incorporated into the Israelites’ worship, which was naturally followed by God’s judgment, resulting in said idols being eliminated, rightfully leaving only Yahweh left to be worshipped. The Bible blatantly contradicts your evidently false narrative!

Can’t help but think about the Maccabean Revolt when presented that suggested dating. Wondering if the rise of the Pharisaic movement was related to the forces driving the revolt, or perhaps a separate but related response to Hellenistic pressures.

As a believer (of which BAR has no understanding), I will state the obvious as found in the Bible. God does not change, therefore the laws of God were extant even before man was created. Avraham knew and understood the entirety of the statutes, commandments, and law (Gen. 26:5 …and Avraham kept my keeping, my commandments my stautes and my laws.) From that time on the law was observed. Since the commandments, statutes, and law were considered holy, you would not find extra biblical sources relating to it.

Jump to the time of Yeshua and it is clear the rabbinics had removed God from the law. The law was now on equal footing as the rabbinics and was being manipulated by the rabbinics, hence Yeshua’s issue with the Pharisees and the Sadducees. This why you will find extra biblical documents regarding the law just pior to and from this time forth. I think that maybe BAR scholars (as they call themselves) need to wake up a bit.

And that’s why he fornicated with Hagar.

He and Sarai were apparently following a known Babylonian law that called on the sterile wife to provide her husband with a servant to produce a child. The consequences of the situation make it clear it was a terrible idea. But one of the fascinating things about the Bible is that the heroes of the People of God actually make all kinds of mistakes and commit all kinds of infidelities, while God keeps trying to teach them and set them right, and is always faithful.

Interesting article but the Bible is clear that many did not follow the practices laid down by God to the people of Israel. Even kings are recorded as violating Gods laws. While finding graven images is evidence of those who did not follow Judaism, it is not proof that others were not following Judaism or not making graven images for religious reasons. And a lack of written material during this time stating their beliefs is understandably absent since any kind of writing except on clay or stone carvings is almost non-existent. Therefore, finding evidence that these laws were violated is not necessarily evidence that the laws did not exist during that time.

It’s funny that even scholars conveniently ignore the next words of the 10 Commandments. The prohibition against graven images is immediately followed by its rationale: “You shall not bow down to them nor serve them.” Ergo, it does not follow that Jews were prohibited to make coins that had a face carved into them, just as long as they didn’t worship them.

Well said. The Mt Ebal Curse Tablet appears to reinforce the Biblical events referred to in Deuteronomy and Joshua regarding the Israelites worshipping at Ebal, uttering the curses in the Law of Moses. It seems to date from the 1400s BCE (nice knowing ya, Ramesside Exodus theory), mentions Yahweh by name 4 times, written in Proto-Sinaitic script. Michael Shelomo Bar-Ron’s recent translations of the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions also support the historicity of Exodus-related events.

Write a Reply or Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Recent Blog Posts

Biblical “Chamber” Identified in Jerusalem?

Akhenaten and Moses

Roman Construction Site Uncovered at Pompeii

Must-read free ebooks.

50 Real People In the Bible Chart

The Dead Sea Scrolls: Past, Present, and Future

Biblical Peoples—The World of Ancient Israel

Who Was Jesus? Exploring the History of Jesus’ Life

Want more bible history.

Sign up to receive our email newsletter and never miss an update.

By submitting above, you agree to our privacy policy .

All-Access Pass

Dig into the world of Bible history with a BAS All-Access membership. Biblical Archaeology Review in print. AND online access to the treasure trove of articles, books, and videos of the BAS Library. AND free Scholar Series lectures online. AND member discounts for BAS travel and live online events.

Signup for Bible History Daily to get updates!

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

Judaism within modernity : essays on Jewish history and religion

Available online, at the library.

Green Library

More options.

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português do Brasil

Featured Content

Find topics of interest and explore encyclopedia content related to those topics

Find articles, photos, maps, films, and more listed alphabetically

For Teachers

Recommended resources and topics if you have limited time to teach about the Holocaust

Explore the ID Cards to learn more about personal experiences during the Holocaust

Timeline of Events

Explore a timeline of events that occurred before, during, and after the Holocaust.

- Introduction to the Holocaust

- Liberation of Nazi Camps

- Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

- Boycott of Jewish Businesses

- Axis Invasion of Yugoslavia

- Antisemitism

- How Many People did the Nazis Murder?

- The Rwanda Genocide

Introduction to Judaism

Judaism is a monotheistic religion, believing in one god. It is not a racial group. Individuals may also associate or identify with Judaism primarily through ethnic or cultural characteristics. Jewish communities may differ in belief, practice, politics, geography, language, and autonomy. Learn more about the practices and beliefs of Judaism.

Jews have lived in many different countries around the world through the centuries.

Major events in the history of Judaism include the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE, the Holocaust, and the founding of the State of Israel in 1948.

Judaism in the 21st century is very diverse, ranging from very Orthodox to more modern denominations.

- Jewish communities before the war

Jewish Life and Religious Practices

There is a wide variety of acceptance and observance of the following practices by denominations and individual Jews.

Jewish life is guided by its annual and life cycle calendars. The annual calendar is a lunar calendar with approximately 354 days in one year on a 12-month cycle, with an extra month (Adar II) added occasionally to compensate for the difference between the lunar and solar calendars.

The Torah is read ritually in synagogue three times a week, on Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays, following a yearly cycle through the entirety (or a third, depending on community) of the Five Books of Moses. Additionally, on holidays, special sections are read in synagogue that tie to the themes or origin story of the holiday being observed.

Jewish prayer services are conducted in the Hebrew language in the more traditional denominations of Judaism, and include varied levels of English (or the native language of the community’s Jews) in denominations such as Reform, Reconstructionist and Renewal. A rabbi can lead services but is not required. On weekdays, daily prayers are recited three times—morning, afternoon, and evening—with a fourth prayer service added on the Sabbath and holidays. While many prayers can be recited individually, certain prayers and activities, such as the reading of the Torah, the mourner’s prayer (the kaddish ), require a minyan or quorum of ten Jewish adults. As with the distinctions regarding English in the prayer service, some traditional denominations only count male adults in a minyan , while others count all adults.

Other central aspects of Jewish ritual observance include the dietary laws (laws of kashrut ) which forbid consumption of certain foods (like pork or shellfish), prohibit the mixing of milk and meat, and prescribe special rules for the slaughter of meat and poultry. Denominations and individual Jews may or may not follow these dietary laws strictly.

Major life-cycle events in Jewish tradition include the brit milah (ritual circumcision on the eighth day of a Jewish boy’s life), Bnai Mitzvah (a ceremony marking the passage from childhood to adulthood, at 12 years for a girl and 13 for a boy), marriage, and death.

Following the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE, the synagogue (derived from a Greek word meaning “assembly”), or Jewish prayer and study house, became the focal point of Jewish life. The role of the priesthood, so central to the Temple service, diminished, and the rabbi (literally, “my master”), or scholar versed in Jewish law, rose to a position of prominence in the community.

After the Holocaust

Before the Nazi takeover of power in 1933, Europe had a vibrant and mature Jewish culture.

By 1945, after the Holocaust , most European Jews—two out of every three—had been killed. Most of the surviving remnant of European Jewry decided to leave Europe. Hundreds of thousands established new lives in Israel , the United States , Canada, Australia, Great Britain, South America, and South Africa.

As of 2016, there were approximately 15 million Jews around the world. About 85% of world Jewry lives in Israel or the United States.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Investigate the wide range of observances and traditions in the Jewish communities before, during, and after the Holocaust.

- Learn about the history of the Jewish community in your country.

Thank you for supporting our work

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies and the Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

- Email Signup

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology

Overview Essay

See also Hava Tirosh-Samuelson's article on Judaism from the Routledge Handbook of Religion and Ecology

Hava Tirosh-Samuelson, Arizona State University

Any generalization about Judaism and ecology should take into consideration the ambiguity of the term “Judaism” and the fact that the Jewish experience encompasses both religious and secular forms. Indeed, the various conceptualizations of “nature” or “environment” illustrate the complexity of the modern Jewish experience. Thus the contribution of Jews to environmentalism is more extensive and the impact of environmentalism on contemporary Judaism is more profound than is commonly acknowledged. In Israel and in the diaspora the ecological crisis has generated many Jewish responses as Jewish theologians, scholars, educators and activists have subjected the entire Jewish tradition to rigorous reinterpretation, identified relevant literary sources, distilled the ecological insights of the tradition, articulated new ecological theologies, and spelled out policies and educational programs (Tirosh-Samuelson 2002a; 2005; 2006).

Judaism and Ecology: Ambiguities and Possibilities

As the oldest of the Western monotheistic religions, Judaism is indispensable to the discourse on religious and ecology (Bauman, Bohannon and O’Brien 2010; Grim and Tucker 2014), but Judaism also occupies an ambiguous position in this discourse. To begin, Judaism problematizes a generic definition of “religion.” Although Judaism had articulated the concepts that framed the western religious vocabulary (e.g., creation, revelation, covenant, prophecy, Scripture, redemption, and messiah), Judaism differs from other traditions because it is a religion of one group of people—the Jews. Thus Jewishness consists not only of beliefs, rituals, norms and practices that cohere into a way of life, but also a collective identity, be it ethnic or national. In the modern period, however, processes of secularization have problematized Jewish existence, giving rise to secular Jews, namely born Jews who do not live by the strictures of the Jewish religious tradition. Interestingly, secular (i.e., non-observant) Jews have been at the forefront of the environmental movement, a point that has received little recognition.

For example, Barry Commoner, the Jewish ecologist and who led the campaign for nuclear disarmament made environmentalism into a political cause (Commoner, 1971). Murray Bookchin, another son of East-European Jewish immigrants in America, articulated Social Ecology, insisting that human responsibility toward nature could be carried out only if humans first eliminate social exploitation, domination and hierarchy by developing communitarianism (Bookchin 1990; Biel 1997; Light 1998). Peter Singer, the son of Jewish refugees from Austria who settled in Australia, theorized the Animal Liberation movement, arguing that humans have an obligation to serve the interests or at least to protect the lives of all animals who suffer or are killed, whether on the farm or in the wild (Singer 1975[1990]). Hans Jonas, the German-Jewish philosopher and student of Heidegger, is regarded as the “father” of the European Green movement because he applied the “imperative of responsibility” to the environment criticizing modern technology (Jonas 1984). Starhawk (aka Miriam Simos), an American Jewish feminist, environmentalist and peace activist, has promoted the Goddess religion, giving rise to Earth-based feminist spirituality (Starhawk 1995; Salomonsen 2002). Finally, David Abram is an American eco-phenomenologist who coined the term “the more-than-human world” to signify the broad commonwealth of earthy life which both includes and exceeds human culture (Abram 1996; 2010). These are all born Jews who have profoundly shaped the theory and practice of contemporary environmentalism, but without appealing to Judaism as an authoritative tradition. In some cases, their ideas reflect the secularization of traditional Jewish ideas and beliefs, and more often their environmentalist vision either substitutes for a commitment to Judaism or directly critiqued Judaism for its presumed limitations or failures.

In the context of the discourse on religion and ecology Judaism is ambiguous for yet another reason: the Bible, the foundation document of Judaism, was accused of being the very cause of ecological crisis (White 1967). Lynn White Jr., the medieval historian, was the first to charge that the Bible commanded humanity to rule the Earth (Gen. 1:28), giving human beings the license to exploit the Earth’s resources for their own benefit. A lay Presbyterian, White intended the charge as prophetic self-criticism that will generate self-examination (Santmire 1984), and indeed he was exceedingly successful: his short essay compelled Jews and Christians to examine the Bible anew in light of the ecological crisis. Is the Bible and “inconvenient text” (Habel 2009) or is the Bible a text whose ecological wisdom has been ignored or misinterpreted? Does the Bible authorize human domination and exploitation of the Earth or rather does the Bible set clear limits on human interaction with the non-human world and commands humans to care responsibly for the Earth and all its non-human inhabitants? Since 1970 Jewish religious environmentalists have examined the Bible in light of the ecological crisis whether to defend the Bible against various (Christian) misreadings (e.g., Cohen 1989), identify a distinctive ecological sensibility (Kay 1988 [2001]; Artson 1991-92 [2001]; Bernstein and Fink 1992; Bernstein 2000; 2005; Benstein 2006; Troster 2008), or articulate Jewish environmental ethics of responsibility (E. Schwartz 1997 [2001]); Waskow 2000; Troster 1991-92 [2001]). For the past four decades the close study of the Bible has made clear that the Jewish sacred text espouses deep concern for the well-being of the Earth and all its inhabitants, because it asserts that “the Earth belongs to God” (Ps. 24:1) and humans are but temporary care takers, or stewards, of God’s Earth; their task is “to till and protect” the Earth (Gen. 2:15) not as controlling managers but as loving gardeners (Tirosh-Samuelson 2017).

A third source of ambiguity is the fact that in Judaism ecological wisdom is found not in the natural order itself but in divinely revealed commands that instruct humans how to treat the Earth and its inhabitants. Scripture declares that the world God had created is “very good” (Gen. 1: 31) but it is neither perfect nor intrinsically holy. Only human beings, who are created “in the image of God” (Gen. 1:28), are able to perfect the world by acting in accordance with divine command. At Sinai God revealed His Will to the Chosen People, Israel, by giving them the Torah (literally, “instruction) which specifies how Israel is to conduct itself in all aspects of life, including conduct toward the physical environment. In the Judaic sacred myth, divine revelation establishes the eternal covenant between God and Israel, an unconditional contract whose collateral is the Land of Israel. As long as Israel observes the Will of God, the Land of Israel is fertile and fecund and Israel flourishes, but when Israel sins, the Land loses its fertility and the people suffer (Deut. 6:10-15). When the sins become egregious, God punishes Israel by exiling the people from the Land. In this manner the Bible set up the causal connection between religious morality and the wellbeing of the environment.

Biblical law spells how Israel is to treat the Earth, vegetation and animals. Viewing Israel as God’s tenant-farmers, Scripture commands that a portion of the land’s yield be returned to its rightful owner, God (Leviticus 19:23). Since creation was an act of separation, Scripture prohibits mixing of plants, fruit trees, fish, birds, and land animals thereby protecting biodiversity (Deut. 22: 9-11). The human being is indeed given responsible authority over other animals and is allowed to consume animals, but human consumption of animals is presented as divine concession to human craving, suggesting that vegetarianism is the ideal (R. Schwartz 2001) and radically limiting what humans are allowed to consume. Scriptural legislation is also attentive to the perpetuation of species by prohibiting the killing of the mother hen with her off-springs (Deut. 22:6) or the cutting of fruit-bearing trees in time of siege (Deut. 20:19). Compassion to domestic animals is evident in the prohibition on the yoking together of animals of uneven strength and is praised as a desired virtue. Since Scripture allows for human sacrifice of animals, the relationship between humans and animals exhibits inequality, but “this inequality is relative not absolute … because it is based on an analogy: as God is to Israel, so is Israel to its flocks and herds” (Klawans 2006, 74). Most importantly, the Bible commands rest on the Sabbath for humans and domestic animals putting “moral limits to economic exchange and commercial exploitation” (Sacks 2012, 169). Extending the Sabbath to the land, the laws of the Sabbatical year ( shemitah ) protects the socially marginal (i.e., the poor, the hungry, the widow, and the orphan) by making sure that crops that grow untended are to be left ownerless for all to share including poor people and animals. In the Bible the allocation of nature’s resources is a religious issue of the highest order and social justice is eco-justice. Divinely revealed environmental legislation enables Israel to sanctify itself and the Land of Israel.

In the Second Temple period (516 BCE-70 CE) the Bible became the canonic Scripture of the Jews, shaping the life of the People of Israel in the Land of Israel and in the diaspora. With the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 CE, Jewish political sovereignty in the Land of Israel came to an end, but Jewish religious and legal autonomy remained intact under the leadership of small scholarly elite, the rabbis. Seeking to fathom the meaning of the divinely revealed Torah, the rabbis expanded biblical legislation through creative exegesis, giving their interpretations the status of Oral Torah which became normative Judaism. For example, from Deuteronomy 22:19 the rabbis derived the principle “Do not Destroy” ( bal tashchit ) which prohibits wanton destruction, a precept that defines the unique Jewish contribution to environmentalism: Judaism focuses on the duties of humans toward nature as opposed to the intrinsic or inherent rights of nature (Schwartz 1997 [2001])). Similarly, on the basis of Deut. 22:6 the rabbis articulated the general principle of tza`ar ba`aley hayyim prohibits the affliction of needless suffering of animals. Although rabbinic ethics is undoubtedly hierarchical and human centered, for example, cruelty to animals is forbidden because it leads to cruelty toward humans (Kalechowsky 1992; 2006; R. Schwartz 2012; ), the rabbis often presented animals as moral exemplars and recognized special animals as “animals of the righteous,” who live in perfect harmony with their Creator (Rosenberg, 2002).

While the rabbis praised virtues that can be conducive to creation care, rabbinic Judaism also generated a certain distance between Jews and the natural world, which is the fourth source of ambiguity. Because the rabbis regarded Torah study to be the ultimate commandment, equal in value to all the other commandments combined, the Torah itself (both Written and Oral) became the prism through which Jews experienced the natural world. From the second century onward rabbinic Judaism has evolved as a textual, scholastic culture that privileges the study of sacred texts at the expense of interest in the natural world for its own sake. The urbanization of Roman Palestine in the 3 rd and 4 th centuries, the Jewish transition from agriculture to commerce and trade in the early centuries of Islam and the limits on Jewish ownership of land in the Christian West exacerbated the departure of Jews from agriculture and the emergence of Jewish culture as a text-based community. This is not to say that Jews were oblivious to their physical surroundings, but that pre-modern Jews interacted with the natural world through textual exegesis. Thus rationalist Jewish philosophers in Spain and Italy sought to fathom how the laws of nature (as understood by Aristotle) reflect the inner esoteric structure of Torah; Pietists in Germany regarded nature as a secret code that could be decoded by the use of secret magical, verbal, and numerical formulas; and kabbalists in Spain saw nature as a symbolic text that mirrors the structure of the Godhead (Shyovitz 2017). All three intellectual strands of pre-modern Judaism treated nature as a linguistic text that has to be interpreted rather than a physical reality that can be sensually experienced by embodied humans (Tirosh-Samuelson 2002; 2011a).

The centrality of sacred texts in Jewish life was critiqued in the modern period first by the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah) and later by Zionism. For the proponents of the Jewish Enlightenment ( maskilim ), knowledge of physical nature was necessary for the modernization of the Jews and their entry into European society and culture. In their journals, novels, and satires, the maskilim presented knowledge about the natural world as conditional to the healing of Jews from excessive bookishness and called for the return of Jews to productive labor, especially agriculture. Going further, Zionism, the Jewish nationalist movement which was an offshoot of the Haskalah, preached the return of Jews to the Land of Israel as the solution to the ills of exilic life. The Zionist movement generated a fifth source of ambiguity in the Jewish relationship to nature. Zionism sought to create a new type of Jews as well as a new, Hebraic, modern culture that will be rooted in the remote agricultural past of ancient Israel, by passing rabbinic Judaism. Zionism endowed the physical environment of the Land of Israel, its topography, flora and fauna, with spiritual (albeit secular) significance, inculcating intimate knowledge of the Land through nature hikes, field trips, and camping.

Paradoxically, the resulting outdoor culture has enabled secular Israelis to understand the natural imagery and metaphors of the Bible (Feliks 1990; Hareuveni 1980), the document that legitimized the Zionist national project (Schweid 1985). More problematically, the successes of the Zionist project exacted a toll on the fragile environment of the Land of Israel (Tal 2002): steep rise in population, rapid urbanization, the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict, and initial mistakes about natural resource management have generated a long list of environmental problems (e.g., air and water pollution; soil erosion, over use of water, etc.) requiring legislative solutions (Tal, Orenstein and Miller 2013). Today the state of Israel addresses these environmental challenges through a mixture of policies, legislation, and alternative technologies and environmentalism thrives in Israel through green political parties, numerous environmental NGOs, and creative educational and training programs (Tirosh-Samuelson 2012). Many of these environmental initiatives and organizations (e.g., Adam, Teva ve-Din; Sevivah Israel, or Hayyim u-Sevivah) deal with concrete environmental problems without reference to Judaism, but some organizations (e.g., Teva Ivri, Shatil, and the Heschel Center for Sustainability) draw direct inspiration from Jewish religious sources in their theoretical justification and educational programs. The degree to which Israeli environmentalism should be grounded in traditional Jewish sources is hotly debated in Israel and the movement is quite different from its American counterpart (Mann 2012, 148-15).

Eco-Judaism: Practice and Theology

In Israel, where Jews are the majority, environmentalism encompasses advocacy, education, public policy, legislation, sustainable architecture and agriculture, science and technology with limited appeal to the religious sources of Judaism. By contrast, in the diaspora, where Jews are small religio-ethnic minority, Jewish environmental public discourse has to be carried explicitly in religious categories. Since its emergence in the mid-1980s, Jewish environmental activism has brought about the “greening” of Jewish institutions (e.g., synagogues, schools, communal organizations, Jewish community centers, and youth movements). Today, a variety of organizations, programs, and initiatives promote sustainable practices (e.g., energy efficiency, elimination of plastics, recycling and waste reduction programs), reduce consumption and promote new eating habits, plant community gardens, link sustainable agriculture to urban Jewish life and education, include environmental issues in the education of youngsters and adults, organize nature walks and outdoor activities, celebrate Jewish holidays (especially Sukkot, Shavuot and Tu Bishvat) with attention to environmental agricultural themes; promote justice in food production with attention to sustainable agriculture and compassionate treatment of farm animals, and encourage Jews to live sustainably. These programs transcend congregational and denominational boundaries and are often carried out in inter-faith settings in collaboration with non-Jewish organizations. Eco-Judaism consists of environmental activism and eco-theology.

As a grass root movement, Jewish environmental activism educates Jews about environmental matters, inspires Jews to lead an environmentally correct life, implements “green” communal practices, and rallies Jews to support environmental legislation and interfaith activities. The main activities of Jewish environmental organizations and initiatives consist of nature education, environmental awareness, advocacy on environmental legislation, and community building. The programs of Teva Learning Alliance (previously called Teva Learning Center) exemplify how activities are structured to sensitize the participants to nature’s rhythms, inspiring them to develop a meaningful relationship with nature and their own Jewish practices. Through traditional Jewish rituals (e.g., blessings, prayers, and reflections) participants become aware of nature as divine creation or learn about the vital connection between Judaism and environmental stewardship. Elat Chayyim Center for Jewish Spirituality is another example where various programs promote environmentally concerned Judaism as a spiritual practice. One of its programs, ADAMAH: The Jewish Environmental Fellowship, offers leadership training program that teaches the Fellows to live communally and engage in a hands-on curriculum that integrates organized agricultural and sustainable living skills, Jewish learning and living, leadership development and community building. The newly reconstituted Aytzim: Ecological Judaism is an example how environmental education, advocacy, and activism link the Jewish religion with Zionism and how the Internet is used to advance environmentalism: the website Jewcology is now managed by Aytzim. These programs and the Coalition of Jewish and Environmental Life (COEJL), which focuses on educational, legislative, and interfaith programming, illustrate eco-Judaism in practice.

An important aspect of contemporary eco-Judaism is attention to food, since food is the intersection point of humans and animals as well as the intersection between diverse social groups of producers and consumers. Hazon: Jewish Lab of Sustainability is a case in point because it has given rise to the Jewish Food Movement that stresses the redemptive aspect of land cultivation and just production, distribution, and consumption of food. The Jewish Food Movement, which supports organic farming attempts to change the relationship between farm workers, processing/packing house workers, truckers, hospitality and hotel workers and other people involved in the food production industry. As an educational effort the Jewish Food Movement is connected with other environmental initiatives, including the Jewish Farm School in Philadelphia (which focuses on urban permaculture), the Eden Village Camp in Putnam Valley NY (an eco-summer camp that teaches sustainability and outdoor activities), Shomrei Adamah (a Hazon program for Jewish day schools that emphasizes energy flow, natural cycles, biodiversity and interdependence), Kayam Farm at the Pearlstone Center in Maryland (which harvests food for the retreat center and teaches stewardship and sustainability), Ekar Farm in Denver (a communal project that combines food security, environmentalism and urban farming) and Farm Forward in Oregon (a non-profit organization that promotes humane and sustainable animal agriculture) are all designed to bring Jews to integrate knowledge about food and farming with the Jewish tradition.

The concept that gives coherence to eco-Judaism is Eco-Kosher Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi coined the term in 1968 during the labor protests in California led by Cezar Chávez. Schachter-Shalomi defines Eco-Kosher as “a new kind of kashrut that would combine the ancient ways of thought, consumption, and avoidance of cruelty and violence with the new awareness of the wider repercussions of some of our actions” (Schachter-Shalomi and Segel 2013, 157). Eco-Kosher connects concerns about industrial agriculture, global warming, and fair treatment of workers with the Jewish dietary laws about food production, preparation and eating. Eco-Kosher means that Jews should only consume products that meet both Jewish dietary laws as well as Jewish ethical standards, and eco-kosher consumers should encourage food producers to care for the environment, animals and their workers. Since the 1970s Arthur Waskow translated the concept into a full-fledged program of environmental justice in regard to economic and racial inequity, the unjust labor practices, and the causal connection between the exploitation of the Earth resources and unjust political policies, especially in Israel (Waskow 1996). Other rabbis have fused Eco-Kosher with kabbalistic principles as well as with non-Jewish traditions such as the ancient Chinese art of Feng Shui, an ecologically based art of spatial arrangement that incorporates human-made objects with natural surroundings. The concept of Eco-Kosher has also inspired Jewish entrepreneurs to market eco-kosher meat products and the Conservative Movement to issue the Magen Tzedek Initiative, a certification program that assures consumers and retailers that “kosher food products have been produced in keeping with exemplary Jewish ethics in regard to labor, animal welfare, environmental impact, consumer issue and corporate integrity” ( http://www.magentzedek.org )

Combining sustainable agriculture, fair labor practices, and ethical treatment of animals, “eco-Kosher” generates a comprehensive life style whose goal is to bring about Tikkun Olam (literally, “repair of the world”). In rabbinic texts (e.g., Mishna, Gittin 4:2) “ letaken olam ” means to act in accordance to Jewish law so as to usher the Kingdom of God. This utopian notion was given an abstract, cosmic, metaphysical meaning in medieval Kabbalah, especially the 16 th century version of Lurianic Kabbalah. According to Lurianic Kabbalah, rituals performed with kabbalistic intention can bring about not only the amelioration of the human world or even the physical cosmos, but also the divine world (the world of the ten Sefirot) which experiences brokenness and disharmony (symbolized by the separation of the masculine and feminine aspects of the Godhead), due to human sinfulness. In the second half of the 20 th century Tikkun Olam has become the slogan of Jewish social activism, including environmentalism, although few Jews who invoke the term understand its original kabbalistic meaning. In Jewish environmental organizations, the goal of Tikkun Olam is usually linked to two other ethical values: responsibility and interconnectedness . The former highlights human responsibility toward the Earth and its inhabitants and the latter insists on the relationality of all living beings. Both of these values are derived from biblical and rabbinic sources and are invoked in a wide variety of educational programs (Tirosh-Samuelson 2012).

If Jewish environmental activists use “Tikkun Olam” as slogan to mobilize Jews to social actions, with little understanding of its kabbalistic underpinning, several Jewish eco-theologians deliberately build on Kabbalah and Hasidism to articulate Jewish ecological spirituality that could address the ecological crisis. Schachter-Shalomi, the founder of Jewish Renewal Movement, was the first to call for a “paradigm shift” within Judaism, signifying a shift from transcendence to immanence, from monotheism to pantheism, from dualistic to non-dualistic thinking, from patriarchy to egalitarianism (Schachter-Shalomi, 1993). He called this shift “Gaian Consciousness” and argued that Judaism has a distinctive (albeit not exclusive) role to play in the healing of the cosmos: the key ecological precept of Judaism—“Do Not Destroy”—enables Jews to act in ways that prevent what he called, the crime of “planetcide.” Recasting Judaism as pantheistic monism that reframes all the major themes of traditional Judaism and gives rise to new rituals, this New-Age thinker saw his project as “trying to help the Earth rebuild her organicity and establish a healthy governing principles” (Magid 2006, 65; Magid 2013).

Schachter-Shalomi’s friend and colleague, Rabbi Arthur Green has gone further to articulate a systematic ecological Jewish spirituality promoted as “Neo-Hasidism” (Green and Mayse 2019; 2019a) In Green’s “mystical panentheism” Kabbalah and Hasidism are fused with the theory of evolution into a worldview that depicts the “bio-history of the universe” as “sacred drama” (Green 2003, 111). Green presents a holistic view of reality in which all existents are in some way an expression of God and are to some extent intrinsically related to one another (Ibid, 118-119; Green 2010). Although Green’s lyrical depiction of evolution is closer to medieval Neoplatonism than to Darwinism, Green offers contemporary Jews “a Kabbalah for the environmental age” (Green 2002). The systematic fusion of Kabbalah, Hasidism, and environmentalism is presented in the work of Rabbi David Seidenberg who argues that by “applying the principles of Kabbalah to constructive theology, we can train ourselves to see the image of God in all of these dimensions, in a species, in an ecosystem, in the water cycles, in the entirety of this planet, and so on” (Seidenberg 2015, 312). Seidenberg is one example of Jewish spiritual teachers, artists, story tellers, and healers who find in Kabbalah, as well as other spiritual traditions (either Native American or Asian) resources for a syncretistic Jewish ecological spirituality. This ecological spirituality is given a feminist twist in the work of Rabbi Jill Hammer (Hammer 2016; Hammer and Shere 2015), the founder of Tel Shemesh, a web-based spiritual resource center that merges kabbalah and Earth-based feminist spirituality ( http://www.telshemesh.org ). The syncretism of Jewish ecological spirituality brought some critics to question the Jewishness of Jewish environmentalism and to view it as an unacceptable revival of paganism (e.g., Gerstenfeld 1999).

Jewish Environmentalism and Environmental Humanities

The humanities are the disciplines that inquire about the values, norms, meanings, languages and cultures. Beginning in the 1970s, but increasingly in the 1980s and 1990s, a growing number of humanities scholars have begun to argue that ecological matters are not marginal but foundational to their disciplines. The discourse of religion and ecology is considered today part of the environmental humanities, a multi-disciplinary and multi-perspectival inquiry that comprises also of environmental history, environmental philosophy and ethics, ecocriticism, animal studies, queer ecologies, ecofeminism, environmental sociology, political ecology, eco-materialism and posthumanism) (Glotfelty and Fromm 1996; Buell, 2005; Clark 2011; Opermann and Iovino 2017).

The ecological reinterpretation of Judaism has developed with relatively little attention to the environmental humanities. Why? First, the discourse of the environmental humanities is decidedly secular, whereas Jewish environmentalism (at least in the diaspora) is a religious endeavor that uses religious categories. Second, the environmental humanities are theoretical discourses carried out within the bounds of the academy, whereas Jewish environmentalism is a grass-root movement of non-academic activists who care about praxis rather than theory. Third, the academic discourse of environmental humanities is inherently critical, displaying skepticism, distance, and irony, whereas Jewish environmentalism calls for conviction, action, and social transformation. Finally, while some environmental humanities, especially eco-criticism, have attempted to bring the material sciences to the foreground of the humanities in order to understand the relationship between human and non-human organisms, Jewish environmentalism (and one could say Jewish public discourse in general) has been insufficiently attentive to the natural sciences. This is not to say that Jewish environmentalism cannot or should not become informed of the environmental humanities. To the contrary: familiarity with the environmental humanities (i.e., the various strands of environmental philosophy and ethics and eco-criticism) can enrich Jewish environmentalism immensely, but such dialogue could take place only if the academic interlocutors become more informed about and interested in Judaism not as the culprit of the ecological crisis, but as a tradition that could creatively address the crisis.

The dialogue between Jewish environmentalism and environmental humanities could begin in the context of postmodern environmental thought (Oeschlaeger 1995; Zimmerman 1994) and the field of eco-phenomenology (Brown and Toadvine 2003), since Jewish philosophers have greatly contributed to them. Eco-phenomenology is the merger of phenomenology and contemporary environmental thought, according to which the human cognition that “nature has value, that it deserves or demands a certain proper treatment from us, must have its roots in an experience of nature” (ibid, xi). Eco-phenomenology consists of two claims: “first, that an adequate account of our ecological situation requires the methods and insight of phenomenology; and, second, that phenomenology, led by its own momentum, becomes a philosophical ecology, that is, a study of the interrelationship between organism and world in its metaphysical and axiological dimensions” (ibid., xii-xiii). Jewish philosophers trained in the phenomenological tradition—Martin Buber (d. 1965), Hans Jonas (d. 1993), and Emmanuel Levinas (d. 1995) and Derrida (d. 2004)— contributed to eco-phenomenology by framing the relationship between humanity to the natural world in dialogical terms, emphasizing nature as a subject to whom humans are deeply responsible , and by erasing rigid boundaries between humans and animals.

Martin Buber was the first to speak about nature as a subject and to call for a non-instrumental (I-Thou) relationship with nature. Although Buber was not an environmentalist, his relational, dialogical philosophy has exerted deep influence on Christian environmental ethics (McFague 1997; Santmire 2008). If Buber made nature into a moral subject with whom humans can have personal relationship, Hans Jonas endowed life itself with intrinsic moral value as he exposed the ontological basis of the ethics of responsibility, and conversely made ontology informed by ethics (Jonas 1984). Jonas’s philosophy of nature highlighted the purposiveness of all life, arguing that nature commands ultimate respond, allegiance, and final moral commitment (Donnelley 2008). It is the objective goodness of things that determines not only what ought to be but also what humans ought to feel, think, and do, since humans are an integral part of organic life. For Jonas, the “imperative of responsibility” encompasses human responsibility for the continued existence of life in a planet where life is seriously endangered by modern technology. Awareness of the looming disaster generates a “heuristic of fear” that guides us to act so as to protect nature from the possibility of destruction. Humanity is responsible for its own future and must act with concern toward future generations, ensuring that they will have the conditions for life. Jonas’s philosophy of nature was developed in response to the devastation of WWII in which Auschwitz and Hiroshima came about because of modern technology.

Like Jonas, Emmanuel Levinas (yet another student of Heidegger) saw responsibility as the core of the ethical, but went further than Jonas by arguing that responsibility comes first: each person is responsible for the other who faces him. If Jonas argued for collective responsibility of humanity, Levinas argues for infinite individual responsibility : every person has an obligation to his/her neighbor, expanding gradually to cover all living humanity. Levinas’ ethics is decidedly human-centered since he insisted that ethics is “against-nature, against the naturality of nature (Levinas 1998, 171). However, several postmodernist environmentalists have applied Levinas’ ethics to nature which is identified with the absolute Other (Llewelyn 1991; Atternon 2004, and Edelgrass, Hatley and Diehm 2012). How should Levinas’s ethics be applied to nature is still a matter of debate but no one can correctly understand Levinas without acknowledging his Jewishness.

Even more influential than Buber, Jonas, and Levinas, another Jewish philosopher trained in phenomenological tradition—Jacque Derrida—has stimulated postmodernist environmental thought and the field of eco-phenomenology. Derrida’s deconstruction of traditional binary dichotomies characteristic of Western philosophy (e.g., nature/culture; human/animal; transcendence/immanence) exposed the connection between phallologocentrism and “carnivorous virility” (Gross 2015, 142). Derrida criticized the “sacrificial structure of subjectivity” and exposed the links between the hatred of the Other, the hatred of animals, and the hatred of Jews that run throughout Western history and culture (Benjamin 2011). The deconstruction of human/animal boundaries (Derrida 2008) has stimulated the newly emerging field of Animal Studies (e.g., De Mello 2012; Gross and Vallely 2012; Waldau 2013) although the Jewishness of Derrida is often glossed over. Recently scholars of Judaism have begun to interpret the canonic sources of Judaism in light of the insights and methodologies of Animal Studies and environmental humanities (e.g., Belser 2015; Wasserman 2017; Berkowtiz 2018; and Geller 2018), highlighting the connection between constructions of Jews, animals, and difference. Jewish Animal Studies consists of reflections on textual representation of otherness rather than on addressing environmental problems that result from the ecological crisis.

Jewish environmentalism is still a small but growing strand in contemporary Judaism that is attractive to previously unaffiliated Jews, to Jews who have limited or no Jewish education, to seekers who have walked other spiritual and religious paths, and to Jews who are traditionally observant. Commitment to Jewish environmentalism can mean different things: for some, Jewish environmentalism means extending the ethics of responsibility to include the environment, for others environmentalism means a new, holistic, ecological consciousness that overcomes the disruptive dualism of scripture and nature, and for still others, environmentalism signifies the return to earth-based spirituality that links Judaism to other traditions. However interpreted, a plethora of Jewish environmental organizations promote communitarianism, environmental and social justice, and a range of educational programs based on outdoors activities that inculcate respect for nature. Benefiting from the creation of the Internet, Jewish environmental activism disseminates ideas and information about activities through social media and the websites of these organizations make available relevant literary sources, commentaries, organized activities, fellowship programs, and leadership training. While the work of Jewish environmentalism rarely engages the environmental humanities, the dialogue between these discourses could enrich both: Jewish environmentalism could become more theoretically informed and the environmental humanities could openly acknowledge its debt to Jewish ethics of responsibility.

Abram, David. 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology . New York: Vintage Books

____. 1996. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human-World . New York: Vintage Books.

Artson, Bradley Shavit. 1991-92 [2001]. “Our Covenant with Stones: A Jewish Ecology of Earth. Conservative Judaism 44: 25-35. Reprinted in Judaism and Environmental Ethics: A Reader , ed. Martin D. Yaffe, 161-170. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books..

Atterton, Peter. 2004. “Face to Face” with the Other Animal?” In Levinas and Buber: Dialogue & Difference , ed. Peter Atterton, Matthew Calarco and Maurice S. Friedman, 262-281. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press.

Bauman, Whitney, Richard Bohannon, and Kevin O’Brien (eds.). 2010. Grounding Religion: A Field Guide to the Study of Religion and Ecology . New York: Routledge.

Belser, Julia Watts. 2015. Power, Ethics and Ecology in Jewish Late Antiquity: Rabbinic Responses to Drought and Disaster . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Benjamin, Andrew. 2011. Of Jews and Animals: Frontiers of Theory . Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press.

Berkowitz, Beth A. 2018. Animals and Animality in the Babylonian Talmud . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Benstein, Jeremy. 2006. The Way into Judaism and the Environment . Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights..

Bernstein, Ellen. 2005. The Splendor of Creation: A Biblical Ecology. Cleveland: Pilgrim Press.

Bernstein, Ellen (ed.) 2000. Ecology & the Jewish Spirit: Where Nature and the Sacred Meet . Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing.

Bernstein, Ellen and Dan Fink. 1992. Let the Earth Teach You Torah: A Guide to Teaching Jewish Ecological Wisdom . Wyncote, PA: Shomrei Adamah.

Biel, Janet (ed.). 1997. The Murray Bookchin Reader . Montreal, New York, London: Black Rose Books.

Bookchin, Murray. 1990. Remaking Society: Pathways to a Green Future . Boston, MA: South End Press.

Brown, Charles S. and Ted Toadvine. 2003. Eco-Phenomenology: Back to the Earth . Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Buell, Lawrence. 2005. The Future of Environmental Criticism: Environmental Crisis and Literary Imagination . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Clark, Timothy. 2011. The Cambridge Introduction to Literature and the Environment . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, Jeremy. 1989. “Be Fertile and Increase, Fill the Earth and Master It: The Ancient and Medieval Career of a biblical Text . Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Commoner, Barry. 1971. The Closing Circle . New York: Bantam Books.

De Mello, Margo (ed.). 2012. Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-Animal Studies. New York: Columbia University Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 2008. The Animal That Therefore I am , trans. David Wills. New York: Fordham University Press.

Donnelley, Strachan. 2008. “Hans Jonas and Ernst Mayr: An Organic Life and Human Responsibility.” In The Legacy of Hans Jonas: Judaism and the Phenomenon of Life , ed. Hava Tirosh-Samuelson and Christian Wiese, 261-286. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Edelglass, William, James Hatley and Christina Diehm. 2012. Facing Nature: Levinas and the Environment . Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press.

Feliks, Yehuda. 1990. Nature and Man in the Bible: A Chapter in Biblical Ecology . New York: The Soncino Press.

Geller, Jay. 2017. Bestiarum Judaicum: Unnatural Histories of the Jews . New York: Fordham University Press.

Gerstenfeld, Manfred. 1999. “Neo-Paganism in the Public Square and its Relevance to Judaism.” Jewish Political Studies Review 11 (3-4): 11-38.

Glotfelty, Cheryll and Harold Fromm (eds.). 1996. Ecocriticism Reader . Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Gottlieb, Roger S. (ed.) 2006. The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology . Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Green, Arthur. 2010. Radical Judaism: Rethinking God and Tradition . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

_____. 2003. EHYEH: A Kabblaah for Tomorrow . Woodstock, VT: Jewish Light Publishing.

_____. 2002. “A Kabalah for the Environmental Age.” In Judaism and Ecology: Created World and Revealed Word , ed. Hava Tirosh-Samuelson, 3-16. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Green, Arthur and Ariel Evan Mayse (eds.). 2019. A New Hasidism: Roots . Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society/Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

_____. 2019a. A New Hasidism: Branches . Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society/Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Grim John and Mary Evelyn Tucker. 2014. Ecology and Religion . Washington, DC: Island Press.

Gross, Aaron S. 2015. The Question of the Animal and Religion: Theoretical Stakes, Practical Implications . New York: Columbia University Press.

Gross, Aaron and Anne Vallely (eds.). 2012. Animals and the Human Imagination: A Companion to Animal Studies . New York: Columbia University Press.

Habel, Norman C. 2009. An Inconvenient Text: Is a Green Reading of the Bible Possible? Adelaide, Australia: ATF Press.

Hammer, Jill. 2016. The Book of Earth and Other Mysteries . Morrisville NC: Lulu Press.

Hammer, Jill and Taya Shere. 2015. The Hebrew Priestess: Ancient and New Visions of Jewish Women’s Spiritual Leadership. Teaneck, NJ: Ben Yehuda Press.

Hareuveni, Nogah. 1980. Nature in Our Biblical Heritage . Kiryat Ono, Israel: Neot Kedumim.

Jonas, Hans. 1984. The Imperative of Responsibility: In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age . Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Kalechofsky, Roberta. 2006. “Hierarchy, Kinship, and Responsibility: The Jewish Relationship to the Animal World. In A Communion of Subjects: Animals in Religion, Science, and Ethics , ed. Paul Waldau and Kimberly Patton, 91-99. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kaleschofsky, Roberta (ed.). 1992. Judaism and Animal Rights: Classical and Contemporary Responses . Marblehead, MA: Micah Publications.

Kay, Jeanne. 1988 [2001]). “Concepts of Nature in the Hebrew Bible.” Environmental Ethics 10: 309-27. Reprinted in Judaism and Environmental Ethics: A Reader , ed. Martin Yaffe. Lanham, MD: Lexington Press

Klawans, Jonathan. 2006. “Sacrifice in Ancient Israel: Pure Bodies, Domesticated Animals, and the Divine Shepherd.” In A Communion of Subjects: Animals in Religion, Science, and Ethics , ed. Paul Waldau and Kimberly Patton, 65-80. New York: Columbia University Press

Levinas, Emmanuel. 1998. Of God Who Comes to Mind , trans. Bettina Bergo. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Light, Andrew. 1998. Social Ecology after Bookchin . New York and London: The Guilford Press.

Llewelyn, John. 1991. The Middle Voice of Ecological Conscience: A Chiastic Reading of Responsibility in the Neighborhood of Levinas, Heidegger and Others . New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Magid, Shaul. 2013. American Post-Judaism: Identity and Renewal in a Postethnic Society . Bloomington, IN.: Indiana University Press.

_____. 2006. “Jewish Renewal, American Spirituality, and Post-Monotheistic Theology,” Tikkun Magazine (May/June); 62-67.

Mann, Barbara E. 2012. Space and Place in Jewish Studies . New Brunswick, NJ and London: Rutgers University Press.

McFague, Sallie. 1997. Super, Natural Christians: How We Should Love Nature . Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Oeschlaeger, Max (ed.). 1995. Postmodern Environmental Ethics . Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Oppermann, Serpil and Serenella Iovino (eds.). 2017. Environmental Humanities: Voices from the Anthropocene . London and New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Rosenberg, Shalom. 2002. “Torah and Nature in Jewish Thought.” In Judaism and Ecology: Created World and Revealed Word , ed. Hava Tirosh-Samuelson, 189-226.

Salomonsen, Jone. 2002. Enchanted Feminism: The Reclaiming Witches of San Francisco . London and New York: Routledge

Santmire, Paul H. 1984 “The Liberation of Nature: Lynn’s White Challenge Anew. The Christian Century 102: 18: 530-33.

_____. 2008. Nature Reborn: The Ecological and Cosmic Promise of Christian Theology . Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Schachter-Shalomi, Zalman and Joel Segel. 2013. Jewish with Feeling: A Guide to Meaningful Jewish Practice . Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing.

Schachter-Shalomi, Zalman, 1993. Paradigm Shift: From the Jewish Renewal Teachings of Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi , ed. Ellen Singer. Northvale, NJ and Jerusalem: Jason Aronson.

Schwartz, Eilon. 1997 [2001]). “Bal Tashchit: A Jewish Environmental Precept.” Environmental Ethics 19: 355-74. Reprinted in Judaism and Environmental Ethics: A Reader , ed. Martin D. Yaffe. 230-249. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Schwartz, Richard. 2012. “Jewish Traditions.” In Animals and World Religions , ed. Lisa Kemmerer, 169-204. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schweid, Eliezer. 1985. The Land of Israel: National Home or Land of Destiny . Rutherford, Madison, Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, and London and Toronto: Associated University Presses.

Seidenberg, David Mevorach. 2015. Kabbalah and Ecology: God’s Image in the More-Than-Human World . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shyovitz, David I. 2017. A Remembrance of His Wonders: Nature and the Supernatural in Medieval Ashkenaz . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Singer, Peter. 1975 [1990]. Animal Liberation . 2 nd ed. New York: Random House.

Starhawk. 1995. The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess . San Francisco: Harper and Row.

Tal, Alon. 2002. Pollution in the Promised Land: An Environmental History of Israel . Berkeley, CA and London: The University of California Press.

Tal, Alon, Daniel Orenstein, and Char Miller (eds.). 2013. From Ruin to Restoration: Israel’s Environmental History . Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press.

Tirosh-Samuelson, Hava. 2017. “Jewish Environmental Ethics: The Imperative of Responsibility.” In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Religion and Ecology , ed. John Hart, 179-194. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

_____. 2012. “Jewish Environmentalism: Faith, Scholarship and Activism. In Jewish Thought, Jewish Faith , ed. Daniel Lasker (English section), 1-53. Beer Sheba: Ben Gurion University Press.

____. 2011. “Judaism and the Science of Ecology.” In Routledge Companion of Religion and Science , ed. James Haag, Gregory R. Peterson, and Michael L. Spezio, 345-355. New York and London: Routledge.

_____. 2011a. “Kabbalah and Science in the Middle Ages: Preliminary Remarks.” In Science in Medieval Jewish Cultures , ed. Gad Freudenthal, 476-510. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

_____. 2006. “Judaism.” In Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology , ed. Roger S. Gottlieb, 25-64. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

_____. 2005. “Judaism.” Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature , ed. Bron R. Taylor, 525-537. London: Continuum.

____. 2002. “The Textualization of Nature in Jewish Mysticism.” In Judaism and Ecology: Created World and Revealed Word , ed. Hava Tirosh-Samuelson, 389-402. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tirosh-Samuelson, Hava (ed.). 2002a. Judaism and Ecology: Created World and Revealed Word . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Troster, Lawrence. 2008. “God Must Love Beetles: A Jewish View of Biodiversity and Extinction of Species.” Conservative Judaism 60.3: 3-21.

_____. 1991-92 [2001]. “Created in the Image of God: Humanity and Divinity in an Age of Environmentalism.” Conservative Judaism 44: 14-24. Reprinted in Judaism and Environmental Ethics: A Source Reader , ed. Martin D. Yaffe. Lanham: Md., Lexington Books.

Waldau, Paul. 2013. Animal Studies: An Introduction . Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Wasserman, Mira. 2017. Jews and Gentiles and Other Animals: The Talmud after the Humanities . Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press.

Waskow, Arthur. 1996. “What is Eco-Kosher.?” In This Sacred Earth: Religion, Nature, Environment , ed. Roger S. Gottlieb, 297-300. New York and London: Routledge.

Waskow, Arthur (ed.). 2000. Torah of the Earth: 4000 Years of Jewish Ecological Thinking . Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publication.

White, Lynn. 1967. “The Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis.” Science 155:153-157.

Yaffe, Martin D. (ed.). 2001. Judaism and Environmental Ethics: A Reader . Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Zimmerman, Michael. 1994. Contesting Earth’s Future: Radical Ecology and Postmodernity . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Header photo: ©Hava Tirosh-Samuelson, Sea of Galilee

Ancient Jewish diaspora: essays on Hellenism

Jocelyn burney , university of missouri. [email protected].

For over a century, scholars of ancient Judaism have asked how diaspora Jews adapted to living as a minority population in towns and cities around the Mediterranean. To what degree did Jewish communities want to—or, conversely, to what degree were they permitted to—integrate into Greco-Roman civic and cultural life? How did their liturgical and textual practices compare to those in their homeland, and how central to their identity was that homeland? These questions remain unresolved, in large part due to the conflicting nature of the evidence. In cities like Alexandria and Rome, which boasted robust Jewish populations, ancient sources preserve misunderstandings, confusion, and prejudice-driven fears about Judaism that occasionally boiled over into violence. On the other hand, we also possess evidence for Jewish stability and success in the diaspora: synagogue buildings funded by wealthy community members (Sardis is the preeminent example), epigraphic evidence for non-Jewish patrons, and, of course, the writings of Philo of Alexandria, the beneficiary of a good Greek education who famously called Hellenistic Egypt his fatherland ( patris ). How, then, should we understand what it was like to live as an ancient Jew in diaspora?

The present volume takes up this big question, drawing much of its evidence from Hellenistic Alexandria. The volume collects sixteen of Bloch’s essays published between 1999 and 2022, dividing them into four thematic sections. Four essays appear here in English for the first time (chapters 2, 6, 12, and 14). Covering a range of topics, from Philo’s depiction of Moses to ancient Jewish tourism and theater-going, Bloch sheds light on the sophisticated negotiation necessitated by life in the diaspora. On the whole, Bloch argues that diaspora Jews, especially in Alexandria, were well integrated into their Hellenistic milieu. Rather than seeing their cultural negotiation as a symptom of outsiderness and discomfort, Bloch suggests instead that such negotiation was inherent to the Hellenistic Period. In an era of globalism, migration, and new religious movements, diaspora Jews “did not really differ from other peoples of the Hellenistic age, least of all from the Greeks” (3). As such, Bloch argues, those interested in any aspect of Hellenism will benefit from studying the experience of diaspora Jews in the Hellenistic world.

The volume opens with four chapters on “Moses and Exodus.” These chapters investigate how Philo’s depiction of Moses in De vita Mosis sheds light on Philo’s own life and the position of Alexandrian Jews, whom Bloch characterizes as “at times embracing and at other times resisting acculturation” (2). In “Alexandria in Pharaonic Egypt: Projections in De vita Mosis ,” Bloch outlines the autobiographical parallels that Philo wrote into his story of Moses: both Philo and his Moses consider Egypt their fatherland, are philosophers, and reluctantly assume the role of political leader in times of trouble. On this basis, Bloch makes two arguments. First, Philo’s portrayal of Moses as a reluctant leader suggests that De vita Mosis was written near the time of the embassy to Rome in 38 CE, rather than at the beginning of Philo’s career. The second argument is vaguer. “I am not suggesting that Philo was presenting himself as a Moses redivivus, ” Bloch says, but rather that Philo occasionally “slipped” into the role of Moses and used Moses to evaluate his own life. Thus, a study of Philo’s Moses should shed light on the character of Philo, about whom we know very little. Chapters 2–4 also focus on Philo’s Moses to make the case that Philo and his Alexandrian community had mixed feelings about their diasporic status. Like Moses, they were both Jewish and Egyptian, recipients of Greek education, and more concerned with local issues in Alexandria than distant Jerusalem. Few will disagree with this middle ground approach. Bloch does not push the envelope, but his close readings of Philo are insightful and employ a refreshing mix of rabbinic and Greco-Roman comparanda.

The three essays in part 2, “Places and Ruins,” center on issues of memory, or how Jews remembered their past and how they were described by others. One of the highlights is chapter 5, “Geography without Territory: Tacitus’s Digression on the Jews and Its Ethnographic Context,” in which Bloch makes an astute observation about Tacitus’s commentary on Jews and Judaism in book 5 of the Histories . Whereas Tacitus typically follows the tradition of Greek anthropogeography by attributing the ethos of a particular people to the physical environment of its homeland, he fails to mention many of the standard ethnographic topoi in his description of Judaism, including clothing, housing, and armor and customs of war. According to Bloch, Tacitus omitted these topoi because ancient Jews lived in many lands, not just their ethnic homeland of Judea, causing them to fall outside the standard dichotomy of Greek and barbarian. While some aspects of Judaism were consistent from place to place—abstaining from eating pork, observance of the Sabbath, circumcision—Tacitus could not cover the standard range of cultural topoi because of the diversity within diaspora Judaism.

Chapter 7 offers a thought experiment: “What If the Temple of Jerusalem Had Not Been Destroyed by the Romans?” Bloch argues that if Titus had spared the Temple, the practice of animal sacrifice would nevertheless have petered out on its own within a few centuries (136). Citing critiques of sacrifice in Isaiah 1:11–17 and Matthew 9:13 (quoting Hosea 6:6), Bloch argues that Second Temple Judaism was already moving away from animal sacrifice before 70 CE. Furthermore, diaspora Jews had operated without access to the Temple for generations, illustrating the waning importance of the sacrificial cult. Thus, the chapter’s title is somewhat misleading. It is really about the decline of the sacrificial cult over the course of the late Second Temple period, not about the decreasing importance of the Temple in general (which held significance for ancient Jews beyond the sacrificial cult), nor the historical circumstances in the first to fourth centuries CE that would have impacted how long the Temple cult could actually have continued to function. Setting aside whether or not Hadrian would have taken control of the Temple when he rebuilt Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolina, once Jerusalem came under Christian rule, it is reasonable to assume that Christians would have seized the Temple and put an end to the sacrificial cult. As Bloch points out, the destruction of the Temple was critical for Christians, who viewed it as confirmation that God had abandoned the Jews. This would be sufficient reason to capture and/or destroy the Temple in the fourth century, if not earlier. Bloch also raises the possibility that the survival of the Temple after 70 would have suppressed the growth of the rabbinic movement, a fascinating hypothetical worthy of further discussion.

Part 3, “Theater and Myth,” contains chapters on Philo’s reconciling of Jewish myth and allegorical interpretation, Jewish attendance of and participation in the theater, and Egyptian-Jewish relations in Joseph and Aseneth . As in part 1, Bloch characterizes diaspora as a state of constant cultural negotiation. In chapter 8, he argues that Philo struggled to reconcile widespread belief in the historicity of Jewish mythological stories, such as the transformation of Lot’s wife into a pillar of salt (Genesis 19:26), with his method of allegorical interpretation. Such struggle, according to Bloch, makes Philo “part of a common and widespread intellectual discourse” among Hellenistic writers, who likewise doubted the historicity of Greek myths but accepted that myths had some heuristic value, especially for the common person. Likewise, chapter 9 argues for a spectrum of Jewish responses to the theater, from rabbinic prohibitions on entering theaters except in dire circumstances to evidence for Jewish actors and reserved seating for Jews in public theaters. Finally, in chapter 10, Bloch outlines the similarities between Joseph and Aseneth and early Greek novels: an initially reluctant couple eventually falls in love; the occasional erotic moment; suffering and longing; and final resolution. Bloch argues that Joseph and Aseneth has been unjustly singled out as a “Jewish novel” despite its clear embeddedness in Greek literary tradition. “It is not a Jewish reaction to the literary genre of the Greek novel,” Bloch argues, but rather a very early example—perhaps even the earliest—of what came to be known as the Greek novel. Moreover, Aseneth’s shift from frenetic and preoccupied to tranquil and poised after her conversion to Judaism suggests to Bloch “a confident Diaspora Judaism that is less interested in a confrontation with the Egyptians than in highlighting Jewish presence and competence” (215).