The Science of Improving Motivation at Work

The topic of employee motivation can be quite daunting for managers, leaders, and human resources professionals.

Organizations that provide their members with meaningful, engaging work not only contribute to the growth of their bottom line, but also create a sense of vitality and fulfillment that echoes across their organizational cultures and their employees’ personal lives.

“An organization’s ability to learn, and translate that learning into action rapidly, is the ultimate competitive advantage.”

In the context of work, an understanding of motivation can be applied to improve employee productivity and satisfaction; help set individual and organizational goals; put stress in perspective; and structure jobs so that they offer optimal levels of challenge, control, variety, and collaboration.

This article demystifies motivation in the workplace and presents recent findings in organizational behavior that have been found to contribute positively to practices of improving motivation and work life.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

Motivation in the workplace, motivation theories in organizational behavior, employee motivation strategies, motivation and job performance, leadership and motivation, motivation and good business, a take-home message.

Motivation in the workplace has been traditionally understood in terms of extrinsic rewards in the form of compensation, benefits, perks, awards, or career progression.

With today’s rapidly evolving knowledge economy, motivation requires more than a stick-and-carrot approach. Research shows that innovation and creativity, crucial to generating new ideas and greater productivity, are often stifled when extrinsic rewards are introduced.

Daniel Pink (2011) explains the tricky aspect of external rewards and argues that they are like drugs, where more frequent doses are needed more often. Rewards can often signal that an activity is undesirable.

Interesting and challenging activities are often rewarding in themselves. Rewards tend to focus and narrow attention and work well only if they enhance the ability to do something intrinsically valuable. Extrinsic motivation is best when used to motivate employees to perform routine and repetitive activities but can be detrimental for creative endeavors.

Anticipating rewards can also impair judgment and cause risk-seeking behavior because it activates dopamine. We don’t notice peripheral and long-term solutions when immediate rewards are offered. Studies have shown that people will often choose the low road when chasing after rewards because addictive behavior is short-term focused, and some may opt for a quick win.

Pink (2011) warns that greatness and nearsightedness are incompatible, and seven deadly flaws of rewards are soon to follow. He found that anticipating rewards often has undesirable consequences and tends to:

- Extinguish intrinsic motivation

- Decrease performance

- Encourage cheating

- Decrease creativity

- Crowd out good behavior

- Become addictive

- Foster short-term thinking

Pink (2011) suggests that we should reward only routine tasks to boost motivation and provide rationale, acknowledge that some activities are boring, and allow people to complete the task their way. When we increase variety and mastery opportunities at work, we increase motivation.

Rewards should be given only after the task is completed, preferably as a surprise, varied in frequency, and alternated between tangible rewards and praise. Providing information and meaningful, specific feedback about the effort (not the person) has also been found to be more effective than material rewards for increasing motivation (Pink, 2011).

They have shaped the landscape of our understanding of organizational behavior and our approaches to employee motivation. We discuss a few of the most frequently applied theories of motivation in organizational behavior.

Herzberg’s two-factor theory

Frederick Herzberg’s (1959) two-factor theory of motivation, also known as dual-factor theory or motivation-hygiene theory, was a result of a study that analyzed responses of 200 accountants and engineers who were asked about their positive and negative feelings about their work. Herzberg (1959) concluded that two major factors influence employee motivation and satisfaction with their jobs:

- Motivator factors, which can motivate employees to work harder and lead to on-the-job satisfaction, including experiences of greater engagement in and enjoyment of the work, feelings of recognition, and a sense of career progression

- Hygiene factors, which can potentially lead to dissatisfaction and a lack of motivation if they are absent, such as adequate compensation, effective company policies, comprehensive benefits, or good relationships with managers and coworkers

Herzberg (1959) maintained that while motivator and hygiene factors both influence motivation, they appeared to work entirely independently of each other. He found that motivator factors increased employee satisfaction and motivation, but the absence of these factors didn’t necessarily cause dissatisfaction.

Likewise, the presence of hygiene factors didn’t appear to increase satisfaction and motivation, but their absence caused an increase in dissatisfaction. It is debatable whether his theory would hold true today outside of blue-collar industries, particularly among younger generations, who may be looking for meaningful work and growth.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory proposed that employees become motivated along a continuum of needs from basic physiological needs to higher level psychological needs for growth and self-actualization . The hierarchy was originally conceptualized into five levels:

- Physiological needs that must be met for a person to survive, such as food, water, and shelter

- Safety needs that include personal and financial security, health, and wellbeing

- Belonging needs for friendships, relationships, and family

- Esteem needs that include feelings of confidence in the self and respect from others

- Self-actualization needs that define the desire to achieve everything we possibly can and realize our full potential

According to the hierarchy of needs, we must be in good health, safe, and secure with meaningful relationships and confidence before we can reach for the realization of our full potential.

For a full discussion of other theories of psychological needs and the importance of need satisfaction, see our article on How to Motivate .

Hawthorne effect

The Hawthorne effect, named after a series of social experiments on the influence of physical conditions on productivity at Western Electric’s factory in Hawthorne, Chicago, in the 1920s and 30s, was first described by Henry Landsberger in 1958 after he noticed some people tended to work harder and perform better when researchers were observing them.

Although the researchers changed many physical conditions throughout the experiments, including lighting, working hours, and breaks, increases in employee productivity were more significant in response to the attention being paid to them, rather than the physical changes themselves.

Today the Hawthorne effect is best understood as a justification for the value of providing employees with specific and meaningful feedback and recognition. It is contradicted by the existence of results-only workplace environments that allow complete autonomy and are focused on performance and deliverables rather than managing employees.

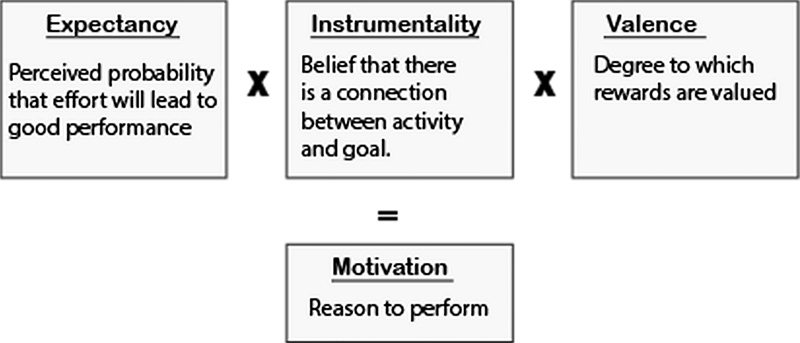

Expectancy theory

Expectancy theory proposes that we are motivated by our expectations of the outcomes as a result of our behavior and make a decision based on the likelihood of being rewarded for that behavior in a way that we perceive as valuable.

For example, an employee may be more likely to work harder if they have been promised a raise than if they only assumed they might get one.

Expectancy theory posits that three elements affect our behavioral choices:

- Expectancy is the belief that our effort will result in our desired goal and is based on our past experience and influenced by our self-confidence and anticipation of how difficult the goal is to achieve.

- Instrumentality is the belief that we will receive a reward if we meet performance expectations.

- Valence is the value we place on the reward.

Expectancy theory tells us that we are most motivated when we believe that we will receive the desired reward if we hit an achievable and valued target, and least motivated if we do not care for the reward or do not believe that our efforts will result in the reward.

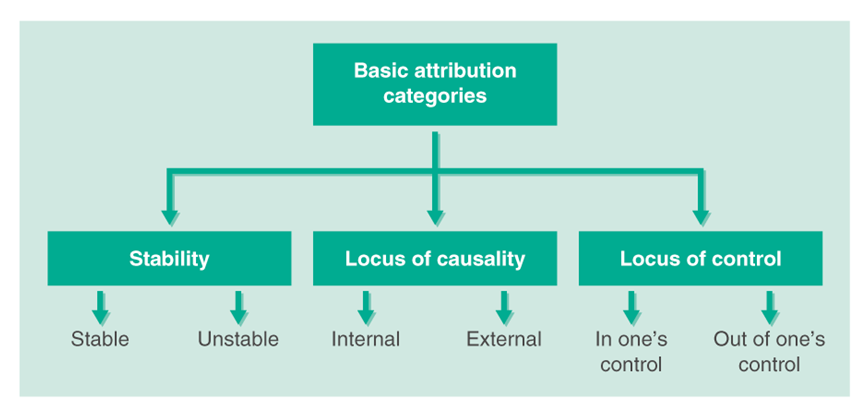

Three-dimensional theory of attribution

Attribution theory explains how we attach meaning to our own and other people’s behavior and how the characteristics of these attributions can affect future motivation.

Bernard Weiner’s three-dimensional theory of attribution proposes that the nature of the specific attribution, such as bad luck or not working hard enough, is less important than the characteristics of that attribution as perceived and experienced by the individual. According to Weiner, there are three main characteristics of attributions that can influence how we behave in the future:

Stability is related to pervasiveness and permanence; an example of a stable factor is an employee believing that they failed to meet the expectation because of a lack of support or competence. An unstable factor might be not performing well due to illness or a temporary shortage of resources.

“There are no secrets to success. It is the result of preparation, hard work, and learning from failure.”

Colin Powell

According to Weiner, stable attributions for successful achievements can be informed by previous positive experiences, such as completing the project on time, and can lead to positive expectations and higher motivation for success in the future. Adverse situations, such as repeated failures to meet the deadline, can lead to stable attributions characterized by a sense of futility and lower expectations in the future.

Locus of control describes a perspective about the event as caused by either an internal or an external factor. For example, if the employee believes it was their fault the project failed, because of an innate quality such as a lack of skills or ability to meet the challenge, they may be less motivated in the future.

If they believe an external factor was to blame, such as an unrealistic deadline or shortage of staff, they may not experience such a drop in motivation.

Controllability defines how controllable or avoidable the situation was. If an employee believes they could have performed better, they may be less motivated to try again in the future than someone who believes that factors outside of their control caused the circumstances surrounding the setback.

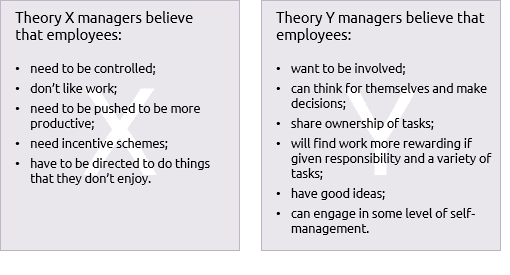

Theory X and theory Y

Douglas McGregor proposed two theories to describe managerial views on employee motivation: theory X and theory Y. These views of employee motivation have drastically different implications for management.

He divided leaders into those who believe most employees avoid work and dislike responsibility (theory X managers) and those who say that most employees enjoy work and exert effort when they have control in the workplace (theory Y managers).

To motivate theory X employees, the company needs to push and control their staff through enforcing rules and implementing punishments.

Theory Y employees, on the other hand, are perceived as consciously choosing to be involved in their work. They are self-motivated and can exert self-management, and leaders’ responsibility is to create a supportive environment and develop opportunities for employees to take on responsibility and show creativity.

Theory X is heavily informed by what we know about intrinsic motivation and the role that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs plays in effective employee motivation.

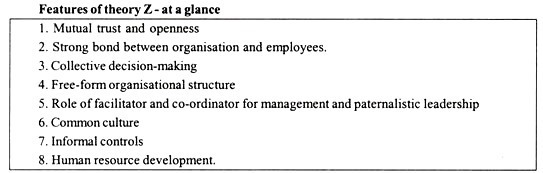

Taking theory X and theory Y as a starting point, theory Z was developed by Dr. William Ouchi. The theory combines American and Japanese management philosophies and focuses on long-term job security, consensual decision making, slow evaluation and promotion procedures, and individual responsibility within a group context.

Its noble goals include increasing employee loyalty to the company by providing a job for life, focusing on the employee’s wellbeing, and encouraging group work and social interaction to motivate employees in the workplace.

There are several implications of these numerous theories on ways to motivate employees. They vary with whatever perspectives leadership ascribes to motivation and how that is cascaded down and incorporated into practices, policies, and culture.

The effectiveness of these approaches is further determined by whether individual preferences for motivation are considered. Nevertheless, various motivational theories can guide our focus on aspects of organizational behavior that may require intervening.

Herzberg’s two-factor theory , for example, implies that for the happiest and most productive workforce, companies need to work on improving both motivator and hygiene factors.

The theory suggests that to help motivate employees, the organization must ensure that everyone feels appreciated and supported, is given plenty of specific and meaningful feedback, and has an understanding of and confidence in how they can grow and progress professionally.

To prevent job dissatisfaction, companies must make sure to address hygiene factors by offering employees the best possible working conditions, fair pay, and supportive relationships.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs , on the other hand, can be used to transform a business where managers struggle with the abstract concept of self-actualization and tend to focus too much on lower level needs. Chip Conley, the founder of the Joie de Vivre hotel chain and head of hospitality at Airbnb, found one way to address this dilemma by helping his employees understand the meaning of their roles during a staff retreat.

In one exercise, he asked groups of housekeepers to describe themselves and their job responsibilities by giving their group a name that reflects the nature and the purpose of what they were doing. They came up with names such as “The Serenity Sisters,” “The Clutter Busters,” and “The Peace of Mind Police.”

These designations provided a meaningful rationale and gave them a sense that they were doing more than just cleaning, instead “creating a space for a traveler who was far away from home to feel safe and protected” (Pattison, 2010). By showing them the value of their roles, Conley enabled his employees to feel respected and motivated to work harder.

The Hawthorne effect studies and Weiner’s three-dimensional theory of attribution have implications for providing and soliciting regular feedback and praise. Recognizing employees’ efforts and providing specific and constructive feedback in the areas where they can improve can help prevent them from attributing their failures to an innate lack of skills.

Praising employees for improvement or using the correct methodology, even if the ultimate results were not achieved, can encourage them to reframe setbacks as learning opportunities. This can foster an environment of psychological safety that can further contribute to the view that success is controllable by using different strategies and setting achievable goals .

Theories X, Y, and Z show that one of the most impactful ways to build a thriving organization is to craft organizational practices that build autonomy, competence, and belonging. These practices include providing decision-making discretion, sharing information broadly, minimizing incidents of incivility, and offering performance feedback.

Being told what to do is not an effective way to negotiate. Having a sense of autonomy at work fuels vitality and growth and creates environments where employees are more likely to thrive when empowered to make decisions that affect their work.

Feedback satisfies the psychological need for competence. When others value our work, we tend to appreciate it more and work harder. Particularly two-way, open, frequent, and guided feedback creates opportunities for learning.

Frequent and specific feedback helps people know where they stand in terms of their skills, competencies, and performance, and builds feelings of competence and thriving. Immediate, specific, and public praise focusing on effort and behavior and not traits is most effective. Positive feedback energizes employees to seek their full potential.

Lack of appreciation is psychologically exhausting, and studies show that recognition improves health because people experience less stress. In addition to being acknowledged by their manager, peer-to-peer recognition was shown to have a positive impact on the employee experience (Anderson, 2018). Rewarding the team around the person who did well and giving more responsibility to top performers rather than time off also had a positive impact.

Stop trying to motivate your employees – Kerry Goyette

Other approaches to motivation at work include those that focus on meaning and those that stress the importance of creating positive work environments.

Meaningful work is increasingly considered to be a cornerstone of motivation. In some cases, burnout is not caused by too much work, but by too little meaning. For many years, researchers have recognized the motivating potential of task significance and doing work that affects the wellbeing of others.

All too often, employees do work that makes a difference but never have the chance to see or to meet the people affected. Research by Adam Grant (2013) speaks to the power of long-term goals that benefit others and shows how the use of meaning to motivate those who are not likely to climb the ladder can make the job meaningful by broadening perspectives.

Creating an upbeat, positive work environment can also play an essential role in increasing employee motivation and can be accomplished through the following:

- Encouraging teamwork and sharing ideas

- Providing tools and knowledge to perform well

- Eliminating conflict as it arises

- Giving employees the freedom to work independently when appropriate

- Helping employees establish professional goals and objectives and aligning these goals with the individual’s self-esteem

- Making the cause and effect relationship clear by establishing a goal and its reward

- Offering encouragement when workers hit notable milestones

- Celebrating employee achievements and team accomplishments while avoiding comparing one worker’s achievements to those of others

- Offering the incentive of a profit-sharing program and collective goal setting and teamwork

- Soliciting employee input through regular surveys of employee satisfaction

- Providing professional enrichment through providing tuition reimbursement and encouraging employees to pursue additional education and participate in industry organizations, skills workshops, and seminars

- Motivating through curiosity and creating an environment that stimulates employee interest to learn more

- Using cooperation and competition as a form of motivation based on individual preferences

Sometimes, inexperienced leaders will assume that the same factors that motivate one employee, or the leaders themselves, will motivate others too. Some will make the mistake of introducing de-motivating factors into the workplace, such as punishment for mistakes or frequent criticism, but negative reinforcement rarely works and often backfires.

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

There are several positive psychology interventions that can be used in the workplace to improve important outcomes, such as reduced job stress and increased motivation, work engagement, and job performance. Numerous empirical studies have been conducted in recent years to verify the effects of these interventions.

Psychological capital interventions

Psychological capital interventions are associated with a variety of work outcomes that include improved job performance, engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors (Avey, 2014; Luthans & Youssef-Morgan 2017). Psychological capital refers to a psychological state that is malleable and open to development and consists of four major components:

- Self-efficacy and confidence in our ability to succeed at challenging work tasks

- Optimism and positive attributions about the future of our career or company

- Hope and redirecting paths to work goals in the face of obstacles

- Resilience in the workplace and bouncing back from adverse situations (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017)

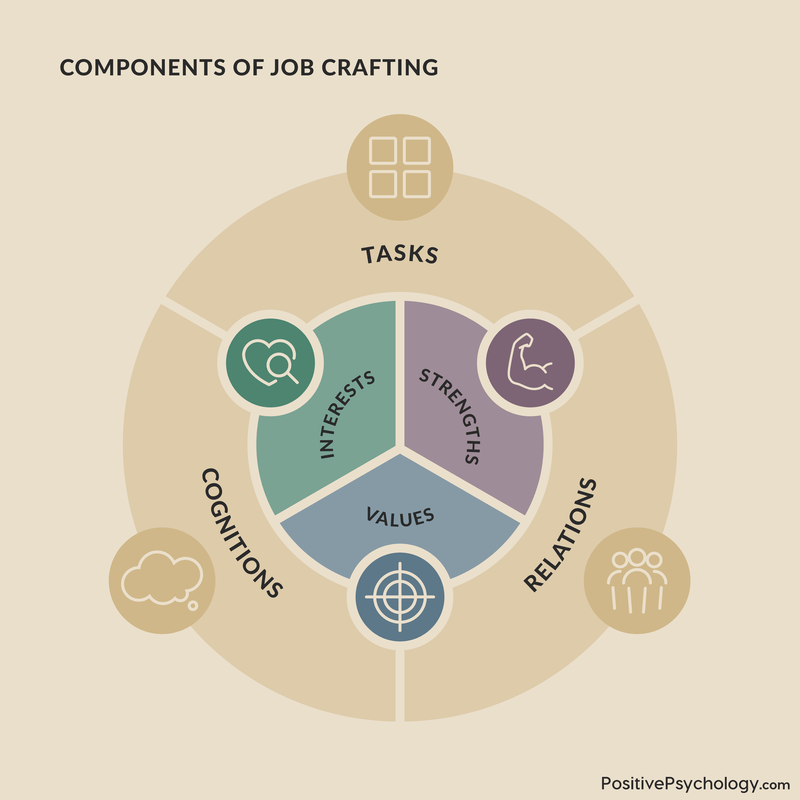

Job crafting interventions

Job crafting interventions – where employees design and have control over the characteristics of their work to create an optimal fit between work demands and their personal strengths – can lead to improved performance and greater work engagement (Bakker, Tims, & Derks, 2012; van Wingerden, Bakker, & Derks, 2016).

The concept of job crafting is rooted in the jobs demands–resources theory and suggests that employee motivation, engagement, and performance can be influenced by practices such as (Bakker et al., 2012):

- Attempts to alter social job resources, such as feedback and coaching

- Structural job resources, such as opportunities to develop at work

- Challenging job demands, such as reducing workload and creating new projects

Job crafting is a self-initiated, proactive process by which employees change elements of their jobs to optimize the fit between their job demands and personal needs, abilities, and strengths (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001).

Today’s motivation research shows that participation is likely to lead to several positive behaviors as long as managers encourage greater engagement, motivation, and productivity while recognizing the importance of rest and work recovery.

One key factor for increasing work engagement is psychological safety (Kahn, 1990). Psychological safety allows an employee or team member to engage in interpersonal risk taking and refers to being able to bring our authentic self to work without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career (Edmondson, 1999).

When employees perceive psychological safety, they are less likely to be distracted by negative emotions such as fear, which stems from worrying about controlling perceptions of managers and colleagues.

Dealing with fear also requires intense emotional regulation (Barsade, Brief, & Spataro, 2003), which takes away from the ability to fully immerse ourselves in our work tasks. The presence of psychological safety in the workplace decreases such distractions and allows employees to expend their energy toward being absorbed and attentive to work tasks.

Effective structural features, such as coaching leadership and context support, are some ways managers can initiate psychological safety in the workplace (Hackman, 1987). Leaders’ behavior can significantly influence how employees behave and lead to greater trust (Tyler & Lind, 1992).

Supportive, coaching-oriented, and non-defensive responses to employee concerns and questions can lead to heightened feelings of safety and ensure the presence of vital psychological capital.

Another essential factor for increasing work engagement and motivation is the balance between employees’ job demands and resources.

Job demands can stem from time pressures, physical demands, high priority, and shift work and are not necessarily detrimental. High job demands and high resources can both increase engagement, but it is important that employees perceive that they are in balance, with sufficient resources to deal with their work demands (Crawford, LePine, & Rich, 2010).

Challenging demands can be very motivating, energizing employees to achieve their goals and stimulating their personal growth. Still, they also require that employees be more attentive and absorbed and direct more energy toward their work (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014).

Unfortunately, when employees perceive that they do not have enough control to tackle these challenging demands, the same high demands will be experienced as very depleting (Karasek, 1979).

This sense of perceived control can be increased with sufficient resources like managerial and peer support and, like the effects of psychological safety, can ensure that employees are not hindered by distraction that can limit their attention, absorption, and energy.

The job demands–resources occupational stress model suggests that job demands that force employees to be attentive and absorbed can be depleting if not coupled with adequate resources, and shows how sufficient resources allow employees to sustain a positive level of engagement that does not eventually lead to discouragement or burnout (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001).

And last but not least, another set of factors that are critical for increasing work engagement involves core self-evaluations and self-concept (Judge & Bono, 2001). Efficacy, self-esteem, locus of control, identity, and perceived social impact may be critical drivers of an individual’s psychological availability, as evident in the attention, absorption, and energy directed toward their work.

Self-esteem and efficacy are enhanced by increasing employees’ general confidence in their abilities, which in turn assists in making them feel secure about themselves and, therefore, more motivated and engaged in their work (Crawford et al., 2010).

Social impact, in particular, has become increasingly important in the growing tendency for employees to seek out meaningful work. One such example is the MBA Oath created by 25 graduating Harvard business students pledging to lead professional careers marked with integrity and ethics:

The MBA oath

“As a business leader, I recognize my role in society.

My purpose is to lead people and manage resources to create value that no single individual can create alone.

My decisions affect the well-being of individuals inside and outside my enterprise, today and tomorrow. Therefore, I promise that:

- I will manage my enterprise with loyalty and care, and will not advance my personal interests at the expense of my enterprise or society.

- I will understand and uphold, in letter and spirit, the laws and contracts governing my conduct and that of my enterprise.

- I will refrain from corruption, unfair competition, or business practices harmful to society.

- I will protect the human rights and dignity of all people affected by my enterprise, and I will oppose discrimination and exploitation.

- I will protect the right of future generations to advance their standard of living and enjoy a healthy planet.

- I will report the performance and risks of my enterprise accurately and honestly.

- I will invest in developing myself and others, helping the management profession continue to advance and create sustainable and inclusive prosperity.

In exercising my professional duties according to these principles, I recognize that my behavior must set an example of integrity, eliciting trust, and esteem from those I serve. I will remain accountable to my peers and to society for my actions and for upholding these standards. This oath, I make freely, and upon my honor.”

Job crafting is the process of personalizing work to better align with one’s strengths, values, and interests (Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Any job, at any level can be ‘crafted,’ and a well-crafted job offers more autonomy, deeper engagement and improved overall wellbeing.

There are three types of job crafting:

- Task crafting involves adding or removing tasks, spending more or less time on certain tasks, or redesigning tasks so that they better align with your core strengths (Berg et al., 2013).

- Relational crafting includes building, reframing, and adapting relationships to foster meaningfulness (Berg et al., 2013).

- Cognitive crafting defines how we think about our jobs, including how we perceive tasks and the meaning behind them.

If you would like to guide others through their own unique job crafting journey, our set of Job Crafting Manuals (PDF) offer a ready-made 7-session coaching trajectory.

Prosocial motivation is an important driver behind many individual and collective accomplishments at work.

It is a strong predictor of persistence, performance, and productivity when accompanied by intrinsic motivation. Prosocial motivation was also indicative of more affiliative citizenship behaviors when it was accompanied by motivation toward impression management motivation and was a stronger predictor of job performance when managers were perceived as trustworthy (Ciulla, 2000).

On a day-to-day basis most jobs can’t fill the tall order of making the world better, but particular incidents at work have meaning because you make a valuable contribution or you are able to genuinely help someone in need.

J. B. Ciulla

Prosocial motivation was shown to enhance the creativity of intrinsically motivated employees, the performance of employees with high core self-evaluations, and the performance evaluations of proactive employees. The psychological mechanisms that enable this are the importance placed on task significance, encouraging perspective taking, and fostering social emotions of anticipated guilt and gratitude (Ciulla, 2000).

Some argue that organizations whose products and services contribute to positive human growth are examples of what constitutes good business (Csíkszentmihályi, 2004). Businesses with a soul are those enterprises where employees experience deep engagement and develop greater complexity.

In these unique environments, employees are provided opportunities to do what they do best. In return, their organizations reap the benefits of higher productivity and lower turnover, as well as greater profit, customer satisfaction, and workplace safety. Most importantly, however, the level of engagement, involvement, or degree to which employees are positively stretched contributes to the experience of wellbeing at work (Csíkszentmihályi, 2004).

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Daniel Pink (2011) argues that when it comes to motivation, management is the problem, not the solution, as it represents antiquated notions of what motivates people. He claims that even the most sophisticated forms of empowering employees and providing flexibility are no more than civilized forms of control.

He gives an example of companies that fall under the umbrella of what is known as results-only work environments (ROWEs), which allow all their employees to work whenever and wherever they want as long their work gets done.

Valuing results rather than face time can change the cultural definition of a successful worker by challenging the notion that long hours and constant availability signal commitment (Kelly, Moen, & Tranby, 2011).

Studies show that ROWEs can increase employees’ control over their work schedule; improve work–life fit; positively affect employees’ sleep duration, energy levels, self-reported health, and exercise; and decrease tobacco and alcohol use (Moen, Kelly, & Lam, 2013; Moen, Kelly, Tranby, & Huang, 2011).

Perhaps this type of solution sounds overly ambitious, and many traditional working environments are not ready for such drastic changes. Nevertheless, it is hard to ignore the quickly amassing evidence that work environments that offer autonomy, opportunities for growth, and pursuit of meaning are good for our health, our souls, and our society.

Leave us your thoughts on this topic.

Related reading: Motivation in Education: What It Takes to Motivate Our Kids

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

- Anderson, D. (2018, February 22). 11 Surprising statistics about employee recognition [infographic]. Best Practice in Human Resources. Retrieved from https://www.bestpracticeinhr.com/11-surprising-statistics-about-employee-recognition-infographic/

- Avey, J. B. (2014). The left side of psychological capital: New evidence on the antecedents of PsyCap. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21( 2), 141–149.

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands–resources theory. In P. Y. Chen & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (vol. 3). John Wiley and Sons.

- Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations , 65 (10), 1359–1378

- Barsade, S. G., Brief, A. P., & Spataro, S. E. (2003). The affective revolution in organizational behavior: The emergence of a paradigm. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (pp. 3–52). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B. J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81-104) . American Psychological Association.

- Ciulla, J. B. (2000). The working life: The promise and betrayal of modern work. Three Rivers Press.

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology , 95 (5), 834–848.

- Csíkszentmihályi, M. (2004). Good business: Leadership, flow, and the making of meaning. Penguin Books.

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands–resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology , 863) , 499–512.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly , 44 (2), 350–383.

- Grant, A. M. (2013). Give and take: A revolutionary approach to success. Penguin.

- Hackman, J. R. (1987). The design of work teams. In J. Lorsch (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 315–342). Prentice-Hall.

- Herzberg, F. (1959). The motivation to work. Wiley.

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits – self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability – with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology , 86 (1), 80–92.

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal , 33 (4), 692–724.

- Karasek, R. A., Jr. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 (2), 285–308.

- Kelly, E. L., Moen, P., & Tranby, E. (2011). Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: Schedule control in a white-collar organization. American Sociological Review , 76 (2), 265–290.

- Landsberger, H. A. (1958). Hawthorne revisited: Management and the worker, its critics, and developments in human relations in industry. Cornell University.

- Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4 , 339-366.

- Moen, P., Kelly, E. L., & Lam, J. (2013). Healthy work revisited: Do changes in time strain predict well-being? Journal of occupational health psychology, 18 (2), 157.

- Moen, P., Kelly, E., Tranby, E., & Huang, Q. (2011). Changing work, changing health: Can real work-time flexibility promote health behaviors and well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(4), 404–429.

- Pattison, K. (2010, August 26). Chip Conley took the Maslow pyramid, made it an employee pyramid and saved his company. Fast Company. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/1685009/chip-conley-took-maslow-pyramid-made-it-employee-pyramid-and-saved-his-company

- Pink, D. H. (2011). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Penguin.

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2) , 1-9.

- Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 25) (pp. 115–191). Academic Press.

- von Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2016). A test of a job demands–resources intervention. Journal of Managerial Psychology , 31 (3), 686–701.

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26 (2), 179–201.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Good and helpful study thank you. It will help achieving goals for my clients. Thank you for this information

A lot of data is really given. Validation is correct. The next step is the exchange of knowledge in order to create an optimal model of motivation.

A good article, thank you for sharing. The views and work by the likes of Daniel Pink, Dan Ariely, Barry Schwartz etc have really got me questioning and reflecting on my own views on workplace motivation. There are far too many organisations and leaders who continue to rely on hedonic principles for motivation (until recently, myself included!!). An excellent book which shares these modern views is ‘Primed to Perform’ by Doshi and McGregor (2015). Based on the earlier work of Deci and Ryan’s self determination theory the book explores the principle of ‘why people work, determines how well they work’. A easy to read and enjoyable book that offers a very practical way of applying in the workplace.

Thanks for mentioning that. Sounds like a good read.

All the best, Annelé

Motivation – a piece of art every manager should obtain and remember by heart and continue to embrace.

Exceptionally good write-up on the subject applicable for personal and professional betterment. Simplified theorem appeals to think and learn at least one thing that means an inspiration to the reader. I appreciate your efforts through this contributive work.

Excelente artículo sobre motivación. Me inspira. Gracias

Very helpful for everyone studying motivation right now! It’s brilliant the way it’s witten and also brought to the reader. Thank you.

Such a brilliant piece! A super coverage of existing theories clearly written. It serves as an excellent overview (or reminder for those of us who once knew the older stuff by heart!) Thank you!

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Victor Vroom’s Expectancy Theory of Motivation

Motivation is vital to beginning and maintaining healthy behavior in the workplace, education, and beyond, and it drives us toward our desired outcomes (Zajda, 2023). [...]

SMART Goals, HARD Goals, PACT, or OKRs: What Works?

Goal setting is vital in business, education, and performance environments such as sports, yet it is also a key component of many coaching and counseling [...]

How to Assess and Improve Readiness for Change

Clients seeking professional help from a counselor or therapist are often aware they need to change yet may not be ready to begin their journey. [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (3)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

3 Goal Achievement Exercises Pack

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Job Satisfaction and Motivation, Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 1087

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Job satisfaction implies to contentment that is attributed to interaction of the positive and the negative feelings inherent in an employee toward the work that his or her performs. Job satisfaction entails more of a journey than a destination because is is applicable to the employee and the employer alike. There lacks a definitive way of evaluating job satisfaction and ensuring that it exists (Armstrong, 2005).

Job satisfaction among the involves the process through which all requirements as well as demands of workers are efficiently addressed by team leaders, managers, as well as any other responsible person in the business. Job satisfaction may results from competently addressing the employees’ needs as well as wants in the workplace. People are different as a result of cultural along with personally differences, this therefore require greater examination in order to address all employees needs effectively. From time to time employee demands and wants keep on changing due to the dynamics and technological advancements in the society. This has consequently made employees to have changes in their needs at theworkplace which need to be looked properly in order to ensure satisfaction.

Job satisfaction factors

Employees in any organization have constantly admired to be treated properly in harmony with their needs as well as want in order to experience satisfaction and honor. Most of the organizations are implementing any potential strategies to identify how they can install satisfaction among their employees. Failure to satisfy employees is a significant factor in low productivity as they may find no reason to perform effectively.

The overall satisfaction with regard to his or her job is determined by several factors that work in combination. The most important of these factors involve financial compensation. Others include working conditions, opportunity for advancement, the level workload and stress, respect from the co-workers, relationship with the supervisors and financial rewards.

Opportunities of training and development in the workplace are also a key factor in determining if the employees will be satisfied or not in their workplace. It is therefore the responsibility of the management to create room for employees to advance their skills as well as knowledge. This is efficiently achievable through setting up training centers within the organization and also paying seminar fees for them. It is critical to pay bills associated with the employees medical expenses in case of injury while at work in the organization and also create a secure working environment by putting in place sound security measures.

Importance of Job Satisfaction at the workplace

Job satisfaction has important implications on the working environment of employees this consequently affects the level of performance and output of the employee. The level of performance depends on the happiness in employees that comes from job satisfaction.

Employees are the most valued assets in a company. Thus the management must consider sufficient investment in their human capital to facilitate for the creation of a positive environment in the workplace, empowerment of employees by means of trusted relationships and provision of secondary benefits which ideally prop up the work life, interests as well as the general well being of the employee.

Employee Motivation

Maslow’s theory of motivation and the 5 stage levels

Maslow’s theory gives a detailed discussion of the understanding of relative creation of individual realization in individuals turning out to be further refined particularly when to making an explicit understanding in as far as they are concerned (Armstrong, 2005). Maslow has divided the elements of employment satisfaction into five (5) stage levels. The stage levels comprise of self-actualization, the esteem, love or belonging, the safety as well as the physiological appreciation of what purposely makes up human beings to have a better feeling associated with their self worth.

Why Maslow’s theory is the most effective in the organization?

These theories compel the strike a balance on their policies and growth and development among the employees in their business enterprises. It could be implicit that these theories are particularly intended to make an unambiguous indication on the best possible approach of treating employees in the work place and consequently motivate them so that they can effectively respond accordingly to the requirements that the organization management anticipates that they give attention to (Armstrong, 2005). The ability to strike such a balance is an important precursor in the growth of employees which would occur especially in relation to the connection that the organization management have towards their employees hence creating a more unified organization that is geared up towards progress.

Motivation is a phenomenon that is translated in a varied manner among different individuals. Every person is unique in terms of their individual needs, attitudes, wants, beliefs as well as expectations. There is no solitary motivational method that works for every employee. A supervisor therefore should not think that factors that motivate him personally are the same as the ones that motivate junior employees. In turn, things that motivate one employee are not the same as those for another employee. In addition, the level of motivation between individuals is differs depending on the situation.

Examples on how companies use this theory to motivate employees

The theories postulated by Maslow are applicable in many business organizations because the self-actualization as well as self-esteem mentioned in these theories has a significantly critical impact on how an individual develops to become a better person. In an attempt to motivate employees, Maslow theories enforce the creation of balance on company policies which serve an important role in advancing the growth and development among the company employees for the mutual benefit of the employer and the employee.

It is imperative for managers to become skilled at the determinants of motivation in a business. Employees who are not motivated are likely to conduct their work with little or no effort, which results to low output. In worst scenarios, unmotivated employees have been known to exit the company. This in turn will not make the organization achieve its goals and objectives. In work places that have constant changing environments, motivated employees help organizations to endure and survive through hardships

Motivation is a very important aspect in the management of human resources. The continuance of an organization relies on the motivation of its employees. The senior management in the organization need to appreciate and recognize the importance of motivating employees. Many managers do not realize the effect that motivation can have on their businesses

Organization management plays a crucial role in enhancing firm performance. It is the duty of the management to enforce policies as well as structures that concern employees’ behaviour along with attitudes.

Armstrong, M, A Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice , 9 th Ed. Kogan Page, London, 2005.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Change Theory in the Implementation of Lactation Education Program, Essay Example

African American History Before 1877, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

How Does Work Motivation Impact Employees’ Investment at Work and Their Job Engagement? A Moderated-Moderation Perspective Through an International Lens

1 Independent Researcher, Netanya, Israel

Takuma Kimura

2 Graduate School of Career Studies, Hosei University, Tokyo, Japan

Associated Data

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

This paper aims at shedding light on the effects that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, as predictors, have on heavy work investment of time and effort and on job engagement. Using a questionnaire survey, this study conducted a moderated-moderation analysis, considering two conditional effects—worker’s status (working students vs. non-student employees) and country (Israel vs. Japan)—as potential moderators, since there are clear cultural differences between these countries. Data were gathered from 242 Israeli and 171 Japanese participants. The analyses revealed that worker’s status moderates the effects of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on heavy work investment of time and effort and on job engagement and that the moderating effects were conditioned by country differences. Theoretical and practical implications and future research suggestions are discussed.

Introduction

Our world today has been described by the acronym VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous). In this rapidly changing world, organizations and individuals need to engage in continuous learning. To achieve a competitive advantage, organizations need to develop organizational learning, which can be achieved by acquiring learning individuals. From the latter’s viewpoint, it is getting more necessary for workers to learn continuously to enhance and maintain their employability. As shown in previous research, the number of people engaging in lifelong learning has significantly increased ( Corrales-Herrero and Rodríguez-Prado, 2018 ).

In such an era, an organization needs to acquire and retain learning individuals. However, it is not an easy task because they might have turnover intentions, even when they are motivated to work. Since learning individuals enhance their skills continuously and have a “third place” for new encounters (e.g., school), they are likely to find other attractive job opportunities. Therefore, it is valuable for us to explore how motivation affects learning individuals’ attitudes and behavior. However, to the best of our knowledge, researchers have not addressed this issue.

Recently, researchers and practitioners have paid increasing attention to employees’ job engagement (JE) ( Bailey et al., 2017 ). Previous studies suggested that engaged workers are likely to achieve high performance and have low intention to leave ( Rich et al., 2010 ; Alarcon and Edwards, 2011 ). However, JE does not necessarily represent workers’ favorable attitude ( van Beek et al., 2011 ). In the case of working individuals, their appearance of being “highly engaged” can be caused by time constraints or impression management motive.

Recognizing the ambiguous nature of “engaged workers,” this study also focuses on a relatively new construct called heavy work investment (HWI). People high in HWI are apparently similar to those high in JE. However, as will be discussed later, these two constructs are distinct. By focusing on both engagement and HWI, we can reveal the underlying mechanism of how motivation affects the learning individuals’ engagement.

To address these issues, we analyzed quantitative data which include both learning individuals (hereafter called “working students”) and non-student workers. The choice of employees who are students as opposed to “regular” employees was based on arguments presented in the conservation of resources (COR) theory ( Hobfoll, 1989 , 2011 ). It will be elaborated further in this paper.

Besides, since the contexts of lifelong learning and work in an organization can affect the focal mechanism, we collected data from two countries—Israel and Japan—and conducted a between-country comparative analysis. As we will discuss below, these two countries widely differ in cultural dimensions, as suggested by Hofstede (1980 , 2018) . We limit the scope of the research to Israel and Japan to concentrate on a specific issue which was not investigated in previous studies, especially in a comparison between these two countries (to the best of our knowledge). The sample and analysis of this study can provide insightful implications because these two countries are widely different in their national cultural contexts.

Work Motivation

A general definition of motivation is the psychological force that generates complex processes of goal-directed thoughts and behaviors. These processes revolve around an individual’s internal psychological forces alongside external environmental/contextual forces and determine the direction, intensity, and persistence of personal behavior aimed at a specific goal(s) ( Kanfer, 2009 ; Kanfer et al., 2017 ). In the work domain, work motivation is “a set of energetic forces that originate within individuals, as well as in their environment, to initiate work-related behaviors and to determine their form, direction, intensity and duration” (after Pinder, 2008 , p. 11). As mentioned, work motivation is derived from an interaction between individual differences and their environment (e.g., cultural, societal, and work organizational) ( Latham and Pinder, 2005 ). In addition, motivation is affected by personality traits, needs, and even work fit, while generating various outcomes and attitudes, such as satisfaction, organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs), engagement, and more (for further reading, see Tziner et al., 2012 ).

Moreover, work motivation, as an umbrella term under the self-determination theory (SDT), is usually broken down into two main constructs—intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation ( Ryan and Deci, 2000b ). On the one hand, intrinsic motivation is an internal driver. Employees work out of the excitement, feeling of accomplishment, joy, and personal satisfaction they derive both from the processes of work-related activities and from their results ( Deci and Ryan, 1985 ; Bauer et al., 2016 ; Legault, 2016 ). On the other hand, extrinsic motivation maintains that the individual’s drive to work is influenced by the organization, the work itself, and the employee’s environment. These can range from social norms, peer influence, financial needs, promises of reward, and more. As such, being extrinsically motivated is being focused on the utility of the activity rather than the activity itself (see Deci and Ryan, 1985 ; Legault, 2016 ). However, this does not, by any means, point that extrinsic motivation is less effective than intrinsic motivation ( Deci et al., 1999 ).

Furthermore, the SDT ( Ryan and Deci, 2000b ) argues that each type of motivation is on opposite poles of a single continuum. However, we agree with the notion that they are mutually independent, as Rockmann and Ballinger (2017) wrote:

“…there is increasing evidence that intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are independent, each with unique antecedents and outcomes … in organizations, because financial incentives exist alongside interesting tasks, individuals can simultaneously experience extrinsic and intrinsic motivation for doing their work.” (p. 11)

Literature-wise, the intrinsic–extrinsic outlook of motivation lacks coherent research, and to the best of our knowledge, most of the past research addressed the intrinsic part (e.g., Rich et al., 2010 ; Bauer et al., 2016 ). As such, we would align with the approach to distinguish the two work motivations as was reviewed in this section and consequently treat it as a predictor in our research.

Job Engagement

Work engagement is typically defined as “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” ( Schaufeli et al., 2002 , p. 74). As such, engaged employees appear to be hardworking ( vigor ), are more involved in their work ( dedication ), and are more immersed in their work ( absorption ) (see also Bakker et al., 2008 ; Chughtai and Buckley, 2011 ; Taris et al., 2015 ). JE was initially proposed as a positive construct ( Kahn, 1990 ), and empirical studies revealed that a high level of JE leads to positive work outcomes. For example, recent studies exhibited its positive effect on individual job performance and adverse effect on turnover intention ( Breevaart et al., 2016 ; Owens et al., 2016 ; Shahpouri et al., 2016 ; Kumar et al., 2018 ). Therefore, employees’ JE has been regarded as one of the performance indicators of human resource management.

In terms of antecedents and predictors, it is broadly accepted that JE may be affected by both individual differences (e.g., Sharoni et al., 2015 ; Latta and Fait, 2016 ; Basit, 2017 ) and environmental/contextual elements (e.g., Sharoni et al., 2015 ; Basit, 2017 ; Gyu Park et al., 2017 ; Lebron et al., 2018 ) (see also Macey and Schneider, 2008 ) or even an interaction between these two factors (e.g., Sharoni et al., 2015 ; Hernandez and Guarana, 2018 ).

Intrinsic/Extrinsic Motivation and JE

To the best of our knowledge, only a few papers examined the association between work motivation and JE. For instance, Rich et al. (2010) tested a model in which both intrinsic motivation and JE were tested “vertically,” meaning they were both mediators (in the model) rather than two factors in a predictor–outcome relationship. This offers a further incentive to examine the association between (intrinsic/extrinsic) work motivation and JE.

Because JE is “…driven by perceptions of psychological meaningfulness, safety, and availability at work” ( Hernandez and Guarana, 2018 , p. 1), a vital notion behind work motivation is the perception of the job as a place for fulfilling different needs: extrinsic needs, such as income and status, and intrinsic needs, such as enjoyment, and personal challenge. This perception, very likely, bolsters the association between the employees’ drive to work and the workplace or the work themselves, increasing the involvement and the amount of work they put into their work (i.e., JE). These assumptions lead us to hypothesize the following:

- H1 : Intrinsic motivation positively associates with JE.

- H2 : Extrinsic motivation positively associates with JE.

Heavy Work Investment

Fundamentally different from being immersed or involved at work (e.g., JE), employees usually invest time and energy at their workplace with various manifestations, which ultimately barrel down to the concept of HWI. This umbrella term encompasses two major core aspects: (1) investment of time (i.e., working long hours) and (2) investment of effort and energy (i.e., devoting substantial efforts, both physical and mental, at work) ( Snir and Harpaz, 2012 , Snir and Harpaz, 2015 ). These dimensions are, respectively, called (a) time commitment (HWI-TC) and work intensity (HWI-WI). Notably, many studies deal with the implications of working overtime (e.g., Stimpfel et al., 2012 ; Caruso, 2014 ). However, to the best of our knowledge, empirical studies regarding the investment of efforts at work as an indicator of HWI (e.g., Tziner et al., 2019 ) are scarce. Therefore, the current research addresses both of the core dimensions of HWI (i.e., time [HWI-TC] and effort [HWI-WI]).

In reality, HWI consists of many different constructs (e.g., workaholism and work addiction or passion to work) but conclusively revolves around the devotion of time and effort at work (see Snir and Harpaz, 2015 , p. 6). HWI is apparently similar to JE, but these two constructs are distinct. As shown in previous studies, the correlation between workaholism—one component of HWI—and JE is generally weak, and engaged individuals can be not only high in HWI but also low in HWI ( van Beek et al., 2011 ).

For HWI’s possible predictors, Snir and Harpaz (2012 , 2015) have differentiated between situational and dispositional types of HWI (based on Weiner’s, 1985 , attributional framework). Examples of situational types are financial needs or employer-directed contingencies (external factors), while dispositional types are characterized by individual differences (internal factors), such as work motivation.

Intrinsic/Extrinsic Motivation and HWI

As previously mentioned, employees may be driven to work by both intrinsic and extrinsic forces, motivating them to engage in work activities to fulfill different needs (e.g., salary, enjoyment, challenge, and promotion). Ultimately, these two mutually exclusive elements would translate into the same outcome—increased investment at work. At this juncture, however, we cannot say what type of work motivation (intrinsic/extrinsic) would more tightly link to either (1) the heavier devotion of time (HWI-TC) or (2) the heavier investment of effort (HWI-WI) at work. Consequently, we hypothesize further the following:

- H3 : Intrinsic motivation positively associates with both HWI-TC and HWI-WI.

- H4 : Extrinsic motivation positively associates with both HWI-TC and HWI-WI.

It is important to emphasize that, again, HWI and JE are mutually independent constructs. Nevertheless, HWI points at two different investment “types”—in time and effort. Theoretically, we see that although both aspects of investment are, probably, linked to JE, we may also conclude that these associations would differ based on the type of investment. For example, while workers may allegedly spend a great deal of time on the job, in actuality, they may not be working (studiously) on their given tasks at all, a situation labeled as “presenteeism” (see Rabenu and Aharoni-Goldenberg, 2017 ). However, exerting more effort at work, by definition, means that one is more engaged, to whatever extent, in work (e.g., investing more effort, basically, means investing time as well, but not vice versa). In other words, while we expect that JE will be positively related to dimensions of HWI (one must devote time and invest more effort to be engaged at work), we also assume that JE will be more strongly correlated with the effort dimension, rather than time . As such, we hypothesize the following:

- H5a : JE positively associates with HWI-TC.

- H5b : JE positively associates with HWI-WI.

- H5c : JE has a stronger association with HWI-WI than with HWI-TC.

The purpose of H5a–H5c is to differentiate JE from HWI-WI and HWI-TC, as they may have some overlaps. However, they are still stand-alone constructs, which is the reason the current research gauge them both and correlate them, though they are both outcome variables (an issue of convergent and discriminant validity).

Worker’s Status—Buffering Effect

An organization or a workplace is usually composed of several types of employees, albeit not all of them exhibit the same attitudes and behaviors at work. For example, temporary workers report greater job insecurity and lower well-being than permanent employees ( Dawson et al., 2017 ). Another example is of students (i.e., working students vs. non-student employees). The motivators and incentives needed to drive corporate/working students differ from others. They are, for instance, more interested in salary, promotion, tangible rewards in their job, and other such benefits ( Palloff and Pratt, 2003 ).

Furthermore, capitalizing upon the COR theory ( Hobfoll, 1989 , 2011 ), the main argument is that employees invest various resources (e.g., time, energy, money, effort, and social credibility) at work. The more resources devoted, the less will remain at the individual’s disposal, and prolonged state of depleted resources without gaining others may result in stress and, ultimately, burnout. As such, a worker who is also a student will, by definition, have fewer resources at either domain (work, social life, or family), as opposed to a worker who does not engage in any form of higher education at all. Working students are under severer time constraints than non-student employees because they face “work–study conflict.” Therefore, compared to non-student workers, working students have difficulty in devoting so much time and physical as well as psychological effort to work. Specifically, working students with a low level of motivation may take an interest in studies and thus not be likely to devote much effort to work. However, motivated working students will maintain their effort through effective time management because they highly value their current work. Thus, JE and HWI of working students will depend on their motivation to a greater degree than non-student workers. Ergo, we posit that the associations between intrinsic/extrinsic motivation and HWI and JE are conditioned by the type of worker under investigation.

For the current study, the notion of working students versus non-student employees would be gauged, as not much attention was given to distinguishing both groups in research. Usually, samples were composed of either group distinctively, not in tandem with one another. Hence, we hypothesize the following, based on our previous hypotheses:

- H6 : Worker’s status moderates the relationship between intrinsic motivation and HWI-TC, HWI-WI, and JE, such that the relationship will be weaker for working students than for non-student employees.

- H7 : Worker’s status moderates the relationship between extrinsic motivation and HWI-TC, HWI-WI, and JE, such that the relationship will be weaker for working students than for non-student employees.

Country Difference—Buffering Effect

Worker’s status’ moderation of the links between intrinsic/extrinsic motivation to HWI and JE, as mentioned above, does not appear in a vacuum. This conditioning may also be dependent on international cultural differences. That is to say, we assume that we would receive different results based on the country under investigation because the social, work, cultural, and national values differ from one country to another. Firstly, culture, in this sense, may be defined as “common patterns of beliefs, assumptions, values, and norms of behavior of human groups (represented by societies, institutions, and organizations)” ( Aycan et al., 2000 , p. 194). As mentioned, countries differ from one another in many aspects. The most prominent example is the cultural/national dimensions devised by Hofstede (1980 , 1991) . Different countries display different cultural codes, norms, and behaviors, which may affect their market and work values and behaviors. As such, it is safe to assume that work-related norms and codes differ from one country to another to the extent that working students may exhibit or express certain attitudes and behaviors in country X, but different ones in country Y. The same goes for non-student (or “regular”) workers, as well.

In this study, we examine the case of Israel’s versus Japan’s different situation and cultural perspectives in the work sense. Japan’s culture is more hierarchical and formal than the Israeli counterpart. Japanese believe efforts and hard work may bring “anything” (e.g., prosperity, health, and happiness), while in Israel, there is much informal communication, and “respect” is earned by (hands-on) experience, not necessarily by a top-down hierarchy. Japanese emphasize loyalty, cohesion, and teamwork ( Deshpandé et al., 1993 ; Deshpandé and Farley, 1999 ). Compared to Israeli, Japanese employees are more strongly required to conform to the organization’s norm and dedicate themselves to the organization’s future. Such cultural characteristics may affect the working attitudes and behavior of working students. Specifically, in Japan, working students try to devote as much time as possible even if they are under severe time constraints caused by the study burden. Moreover, sometimes, they experience guilt because they use their time for themselves (i.e., study) rather than for the firm (e.g., socializing with colleagues). Thus, they engage in much overtime work as a tactic of impression management ( Leary and Kowalski, 1990 ) to make themselves look loyal and hard working.

In addition, in Israel, there is high value to performance, while in Japan, competition (between groups, usually) is rooted in society and drives for excellence and perfection. Also, Israelis respect tradition and normative cognition. They tend to “live the present,” rather than save for the future, while Japanese people tend to invest more (e.g., R&D) for the future. Even in economically difficult periods, Japanese people prioritize steady growth and own capitals rather than short-term revenues such that “companies are not here to make money every quarter for the shareholders, but to serve the stakeholders and society at large for many generations to come” (for further reading, see Hofstede, 2018 ).

In Hofstede’s use of the term, some aspects of these cultural differences can be summarized as Japan being higher in power distance, masculinity, and long-term orientation than Israel ( Hofstede, 2018 ). These cultural differences led us to formulate the following hypotheses:

- H8 : Country differences condition the moderation of worker’s status on the relationship between intrinsic motivation and HWI-TC, HWI-WI, and JE, such that the effect of worker’s status suggested in H6 will be weaker for Japanese than for Israelis.

- H9 : Country differences condition the moderation of worker’s status on the relationship between extrinsic motivation and HWI-TC, HWI-WI, and JE, such that the effect of worker’s status suggested in H7 will be weaker for Japanese than for Israelis.

It is important to note, however, that H8 and H9 are also developed to increase the external validity of the research and its generalizability beyond a single culture, as Barrett and Bass (1976) noted that “most research in industrial and organizational psychology is done within one cultural context. This context puts constraints upon both our theories and our practical solutions to the organizational problem” (p. 1675).

Figure 1 portrays the overall model.

Research model. Worker’s status: 1 = working students, 2 = non-student employees. Country: 1 = Israel, 2 = Japan. HWI-TC = time commitment dimension of heavy work investment. HWI-WI = work intensity dimension of heavy work investment.

Materials and Methods

For hypothesis testing, this study conducted questionnaire-based research using samples of company employees who also engage in a manner of higher education (i.e., working students) and those who do not (i.e., “regular” or non-student employees). Since working students in both countries do not concentrate in specific age groups, industries, or functional areas, participants were recruited from various fields. Moreover, to reduce the impact of organization-specific culture, we collected data from various companies rather than from a specific company, in both countries.

Participants

The research constitutes 242 Israeli (70.9% response rate) and 171 Japanese (56.6% response rate) participants, from various industries and organizations. The demographical and descriptive statistics for each sample are presented in Table 1 . The table also contains the result of group difference tests, pointing at some demographic differences between Israeli and Japanese samples. Therefore, the following analyses include these demographics as control variables to control their potential influence on the research model and reduce the problem that would arise from said differences between the two countries.

Demographical and descriptive statistics for the Israeli ( N = 242) and the Japanese ( N = 171; in parenthesis) samples.

The items of the questionnaire were initially written in English and then translated into Hebrew and Japanese, utilizing the back-translation procedure ( Brislin, 1980 ).

Work motivation was gauged by the Work Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation Scale (WEIMS; Tremblay et al., 2009 ), consisting of 18 Likert-type items ranging from 1 (“Does not correspond at all”) to 6 (“Corresponds exactly”). Intrinsic motivation had a high reliability (α Israel = 0.92, α Japan = 0.86; e.g., “…Because I derive much pleasure from learning new things”) as did extrinsic motivation (α Israel = 0.73, α Japan = 0.75; e.g., “…For the income it provides me”).

HWI (see Snir and Harpaz, 2012 ) was tapped by 10 Likert-type items ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 6 (“Strongly agree”), five items for each dimension, namely, time commitment (HWI-TC; e.g., “Few of my peers/colleagues put in more weekly hours to work than I do”) and work intensity (HWI-WI; e.g., “When I work, I really exert myself to the fullest”), respectively. HWI-TC had a high reliability (α Israel = 0.85, α Japan = 0.92) as did HWI-WI (α Israel = 0.95, α Japan = 0.91).

JE was gauged by the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-9 (UWES-9; Schaufeli et al., 2006 ) consisting of nine Likert-type items ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 6 (“Strongly agree”). The measure had a very high reliability (α Israel = 0.95, α Japan = 0.94; e.g., “I am immersed in my work”).