Dictionaries

- Urdu Dictionary

- Punjabi Dictionary

Pashto Dictionary

- Balochi Dictionary

- Sindhi Dictionary

- Saraiki Dictionary

- Brahui Dictionary

- Names Dictionary

- More Dictionaries

Language Tools

- Transliteration

- Inpage Converter

- Web Directory

- Telephone Directory

- Interesting

- Funny Photos

- Photo Comments

Facebook Covers

- Congratulations

- Independence Day

- Love/Romantic

- Miscellaneous

SMS Messages

- Good Morning

- Baap or Beta

- Miya or Biwi

- Ustaad or Shagird

- Doctor or Mareez

- Larka or Larki

- Mehndi Designs

- #latestnews

- #thisdayinhistory

- #ReleaseDate

- Food Recipes

- Pakistan Flag Display Photo

- Farsi Dictionary

- Name Dictionary

English to Pashto Dictionary

Definitions

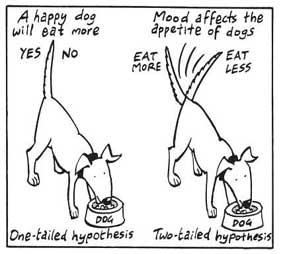

English definition for hypothesis

1. n. a tentative theory about the natural world; a concept that is not yet verified but that if true would explain certain facts or phenomena

2. n. a message expressing an opinion based on incomplete evidence

3. n. a proposal intended to explain certain facts or observations

Synonyms and Antonyms for hypothesis

Related Images

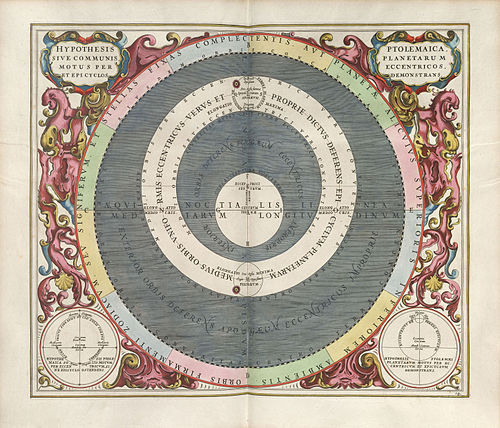

Related Images/Visuals for hypothesis

International Languages

Meaning for hypothesis found in 56 Languages.

Near By Words

- hypothesist

Sponored Video

- Vocabulary Games

- Words Everyday

- Pashto to English Dictionary

- Favorite Words

- Word Search History

English to Pashto Meaning of hypothesis - فرضيه

فکر, فرضيه, د ګمانونو, له پرتلي

I finally have time to test my HYPOTHESIS about the separation of water molecules...

You have a backup HYPOTHESIS ?

Let's say for a moment that I accept the bath-item-gift HYPOTHESIS .

Okay. All right. Let's assume your HYPOTHESIS .

Meaning and definitions of hypothesis, translation in Pashto language for hypothesis with similar and opposite words. Also find spoken pronunciation of hypothesis in Pashto and in English language.

What hypothesis means in Pashto, hypothesis meaning in Pashto, hypothesis definition, examples and pronunciation of hypothesis in Pashto language.

Topic Wise Words

Learn 3000+ common words, learn common gre words, learn words everyday.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 28 August 2023

The diminutive morphological function between English and Pashto languages: a comparative study

- Afzal Khan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8705-9205 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 536 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1514 Accesses

Metrics details

- Language and linguistics

This study aimed to investigate the phenomenon of diminutive morphological function in terms of productivity, similarities, and differences in inflectional bound morphemes between English and Pashto, particularly in the categories of nouns and adjectives. The study also aims to examine the possible influence of ancient languages, such as Greek, on the diminutive morphological function and productivity of these two languages. It is generally assumed that languages descending from similar parental groups share the same diminutive function and productivity pattern in marking morphological mechanisms such as number, gender, and case. Different online sources, libraries, and publication papers were consulted to make a comparison between these two varieties. The findings revealed that both English and Pashto retain a morphological function, but English uses limited inflectional morphemes. Pashto, on the other hand, employs a wide range of suffixations, particularly in marking the diminutive aspect, and that differentiates it from English in semantic and pragmatic expressions. The findings aligned with the initial hypothesis developed that languages descending from similar parental groups use a similar pattern of morphological mechanisms. The only difference is that English drops the inflections to a greater extent because it underwent different phases of modifications, while Pashto still retains the inflections and, in turn, reveals greater productivity. Moreover, the findings disclosed that Pashto is closer to Greek in its inflectional nature and functioning of diminutives than English.

Similar content being viewed by others

Conformity to the obligatory contour principle and the strict layer hypothesis: the avoidance of initial gemination in Maltese

Mufleh Salem M. Alqahtani

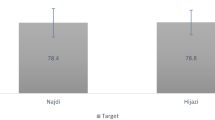

The interaction between Nunation and English definiteness: the case of L1 Najdi and Hijazi speakers

Abdulrahman Alzamil

Meaning patterns of the NP de VP construction in modern Chinese: approaches of covarying collexeme analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis

Jiangping Zhou

Introduction

Morphology relates to the function of productivity in a language, and in turn, the speakers’ lexical entry probes the interlocutors to access the unconscious lexical entry of the mental lexicon during communication. The speakers’ unconscious morphological rules function to decompose a lexical unit and predict its features for pragmatic and productivity purposes in a given context. Inflectional morphemes are a kind of affixes attached to the end of the words to indicate grammatical functions (Khan and Sohail, 2021 ; Shamsan and Attayib, 2015 ). These affixes do not affect the syntactic construction of a language but add to the meaning and enhance the grammatical effects of the language. The relationship of words in a structure in comparison to other words is largely indicated by the inflectional endings of morphemes. The errors in the acquisition of L2 in terms of morphological features are largely committed by L2 learners due to the interference of their L1 (Nazary, 2008 ). This study pinpoints the diminutive morphological function between English and Pashto by highlighting similarities and differences through contrastive analysis that helps the learners and teachers identify the points where the morphological errors occur and adopt preemptive measures to enhance the effect of L2 acquisition. The study also sheds light on the effects of productivity between the two languages as a result of the diminutive morphological function and the influence of high inflectional languages. It also brings forth significant aspects of the morphological mechanism involved in the pragmatic and semantic context that helps researchers and linguists to explore it further. Given the delimitations of the study, the current study is limited to the Yousafzai dialect of the Pashto language particularly, spoken in major parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Other dialects may have different diminutive morphological functions and productivity mechanisms, but this study could be generalized to all speakers who are native to the Pashto language in any part of the world.

The diminutive function of morphology

Diminutives are defined as cross-cultural linguistic segments which contribute semantically and pragmatically to the meaning of size. However, it is generally believed that diminutives refer to expressing the entity in a small connotation. Though diminutives’ semantic and pragmatic function goes much beyond the narrow sense, it explains ‘small’, ‘young’, ‘incomplete’, and ‘insignificant’. Moreover, some languages show the diminutive strategy by employing prefix diminutives and others through suffix diminutives (Gibson et al., 2017 ; Grandi, 2015 ; Jurafsky, 1996 ). Diminutive refers to smallness and loveliness (Wang, 2020 ). Diminutive becomes effective when the social distance between the speakers is minimal as it conveys affection, cuteness, smallness, contempt, and familiarity (Drake, 2018 ; Schneider, 2003 ). The diminutive function of morphology is present in languages such as English, Dutch, and Russian that help in segmenting the lexical constituents used by infants such as ‘horsie’, ‘doggie’, and ‘birdie’ (Kempe et al., 2007 ).

This study is only concerned with examining the diminutive function of inflectional morphemes in English and Pashto and the possible influences of other high inflectional languages on them, such as Greek. According to Yule ( 2016 ), the study of Morphology is to examine forms in a language instead of relying only on ascertaining words. The diminutive function of morphology exists in many parts of the world through employing suffixes in languages like English uses ‘ling’, ‘let’, and ‘iely’; German uses ‘chen’ and ‘lein’; Farsi uses ‘cheh’, and ‘ak’; Spanish uses ‘itola’; and Italian uses ‘ino’, ‘ettola’, and ‘ellola’ (Drake, 2018 ). English is said to have no diminutives (Khaled, 2018 ; Wierzbicka, 2009 ). English has an analytical diminutive marking mechanism that denotes a few lexical markers in distinctive forms such as ‘tiny’, ‘small’, and ‘little’ before the noun categories (Bin Mukhashin, 2018 ; Naciscione, 2010 ). The morphological process of a language plays a significant role in the composition of syntactic units, but when it comes to the diminutive and productivity function, it is more crucial; a language that has more than one form with a similar meaning distinguishes it from other languages in terms of productivity (Aronoff, 1976 ). It is intuitive to realize that the productivity effect of cuteness and smallness in English is expressed by using the inflectional suffixes such as ‘i’, and ‘iely’ in words like ‘Nicky’, ‘Lizzy’, and ‘Bobby’. English speakers do not use less-productive morphemes for nicknames such as ‘ling’ and ‘let’ in ‘Robbling’ and ‘Nicklet’ (Aronoff, 1976 ), for example.

Given its strength, morphology permits the language to espouse new lexemes from the current vocabulary through derivational morphology or to modify the syntactic features of a lexeme by way of its usage in a particular situation via inflectional morphology. Speakers tend to unconsciously learn the combinations of morphemes and suffixations by heart (Manova and Knell, 2021 ). The current study only focuses on the inflectional bound morphemes in the categories of nouns and adjectives to reflect the comparative function of diminutives in them. The complexity in acquiring inflectional morphemes in the English language by Pashto speakers arises due to the different linguistic affiliations and syntactic structures they encounter. Ali et al. ( 2016 ) argue that due to the complexity and dissimilarity in the inflectional patterns of English and Pashto, Pashto-speaking L2 learners find it difficult to learn English morphology.

Von Humboldt and von Humboldt ( 1999 ) have classified the contemporary vernaculars concerning the morphological and productive features in place, in the whole world today, into three main diverse groups: one is “isolating”; second is “agglutinative”; and the third is “inflectional”. Palmer ( 1984 ) states that Chinese is a good illustration of isolating language it does not have morphology. While agglutinative languages are those where the entire linguistic features take place distinctly in a linguistic construction, like the Swahili language, in which the words in sentences do not have patterns of any kind. Finally, coming inflectional languages whose syntactic components are composed together cannot be parted in the real sense of using the language, such as in Greek and Latin languages (Palmer, 2001 ).

Moreover, morphology is divided into two main branches; one is known as derivational morphology, and the second is called inflectional morphology. Both of these branches are characterized by their unique features. Inflectional morphology has got nothing to do with the construction to form new lexemes. Rather, it functions to demonstrate the grammatical aspects like’s of the lexemes to produce specific lexical items for agreement with other linguistic elements in the desired sentence. Conversely, unlike inflectional morphology, derivational morphology deals with the formation of words and the changes that words undergo when they make other categories. Inflectional morphemes do not change the category of the words but mark the agreement and check the features in a given construction, such as the morpheme ‘s’ attached to the word’ book demonstrates the plural number in a given construction. Different languages employ different inflectional strategies, influencing their productivity and diminutive function.

Joseph ( 2005 ) states that Pashto and English are two distinct verities descending from the same Indo-European Family. Momma and Matto ( 2009 ) argue that historical linguistics reveals these two vernaculars to have identical historical connections with the same parental languages, such as the West Germanic Group and that further branched into the Indo-Iranian sub-group where Pashto finds its origin. Therefore, investigating the diminutive inflectional aspects through contrastive analysis would reveal significant insights into these two languages and show the point of similarity and dissimilarity, a branch of Comparative Linguistics.

Previous studies mainly focused on showing the inflectional similarities and differences between English and Pashto. The diminutive morphological function between English and Pashto has not received attention from previous scholars. The current study focuses on examining the similarities and differences in inflectional bound morphemes in nouns and adjectives, focusing on the diminutive functions of these categories and investigating the possible influences of Greek and other natural languages like Bantu and Swahili on them.

In addition, the study attempts to reveal the nature of productivity concerning the diminutive features in both these languages and pinpoint possible measures to avoid issues faced by Pashto speakers in learning English as an L2. The study also has implications for the interlocutors of both languages to help them communicate more effectively cross-culturally through semantic and pragmatic contexts (Khan and Sohail, 2021 ). The study helps teachers, text designers, administrators, and L2 learners understand the problematic areas and plan well for effective learning and teaching of these languages.

Review of literature

Due to the unavailability of relevant studies concerning the diminutive morphological function between English and Pashto, the following available studies are reviewed on other languages, such as Spanish, Persian, Azerbaijani, Chinese, Bantu, and Arabic. It is generally assumed that the numerous inflections with a wide range of diminutive functions in Pashto make it morphologically diverse from other languages descended from the same group, thereby posing difficulties to learners in acquiring English in L2 settings. It is pertinent to mention that English is considered analytical regarding the diminutive function and employs a few lexical markers such as ‘tiny’, ‘little’, and ‘small’ (Bin Mukhashin, 2018 ). Conversely, Pashto has a system of synthetic diminutives that uses different inflectional morphological processes; the meaning of the word undergoes changes, but the word remains intact such as the word ‘motor’ (car). In diminutive pejorative expression, it changes to ‘motorgy’ (a small car) to convey a distaining expression. Similarly, in depreciating expression, the word ‘sigrat’ (cigarette) modifies to ‘sigratgy’ (a small and disdaining sigrat). Pashto is morphologically rich and is the most conservative vernacular among other languages in this family in the region. Pashto has preserved the archaic features that the rest of the languages have almost lost by way of their development over time (Zuhra and Khan, 2009 ). But, so far, no attention has been paid to the diminutive morphological function of Pashto by previous scholars, and in this regard, this study fills the gap and adds to the body of literature.

Hägg ( 2016 ) examined the expression of synthetic diminutives in English and Spanish to reveal the formation’s productivity and denote these languages’ semantic features. The study used two corpora: Corpus of Historical American English and Corpus del Español, along with some academic texts, newspapers, and magazines. The findings demonstrated that Spanish is more productive than English in inflecting different categories regarding diminutive morphological function. The study also revealed that Spanish has strong features about diminutives that enable it to convey a wide range of meaning through different inflectional formations as opposed to English. Wang’s ( 2020 ) study on the Lingchuan dialect’s appellations in China revealed that adding the inflection ‘zi’ mainly to the names or nicknames in Chinese increases intimacy between the interlocutors regarding diminutive expression. However, the meaning of this expression is not much obvious.

Kazemian and Hashemi ( 2014 ) investigated the inflectional bound morphemes of English, Azerbaijani and Persian languages to demonstrate variations and similarities in these languages. The findings revealed that several inflections functioned to mark grammatical categories in each language. Significant findings revealed that the Azerbaijani language retains more inflections in comparison to English and Persian. However, there were some commonalities in the patterns of inflections in all these three languages. English and Persian demonstrated a significantly irregular pattern of inflections in nouns and verb categories for marking plurality, but Azerbaijani witnessed extensive patterns of inflections in all categories of words, which enables the pragmatic and diminutive aspects of it to be broader compared to English. Moreover, the findings demonstrated that numerous operations of inflections that make it difficult for L2 learners to acquire the English language exist in Azeri and Persian. The study suggests that teaching English to native speakers of Azeri and Persian requires an in-depth understanding of these issues to effectively teach L2 learners.

Salim ( 2013 ) investigated the morphological features of the noun category in Arabic and English to reveal the differences between them. The study aimed to show the differences that would help L2 teachers be well-versed in the areas where the two languages differ. The findings revealed that every root word in the Arabic language is significant and retains three different phonological aspects. Through morphological affixation in Arabic, internal vowel modification occurs and causes infinite derivation for the formation of noun and verb classes. The morphological system of Arabic compared to English is very complex, which may cause problems for students learning English as L2. The findings demonstrated that English nouns have two numbers: singular and plural, but Arabic have three numbers: singular, plural and dual. English inflects the nouns only for genitive cases, while Arabic inflects them for three cases: nominative, accusative, and genitive. The findings revealed glaring differences between English and Arabic in morphological construction. The diminutive morphological function is not only to bring modification to the form in a given language but facilitate productivity and meaning connotations (Arabiat and Al-Momani, 2021 ; Hazimy, 2006 ). The diminutive morphological function in the Arabic language predominantly enhances the effect of revealing contempt and belittlement, targeting the decrease or smallness of an expression in a given context. It includes several expressions such as the reduction of size; quantity; disparagement (reducing someone’s respect), and psychological barriers such as pity, gentleness, and endearment (Yahya, 2012 ). Differences in forms lead the L2 learners to the barriers they encounter in acquiring a target language (Baker, 1992 ). Understanding these variations would help the interlocutors to communicate effectively in cross-cultural interaction and enable the L2 learners to acquire either of these languages without facing any problems.

Ibrahim ( 2010 ) examined the process of noun formation in Standard English and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) to demonstrate their similarities and differences and reveal their productivity features. The data for the study was collected from different sources and analyzed to demonstrate the morphological formation of nouns in both languages for productivity purposes. The findings demonstrated some universal similarities between the languages, such as affixation, blending, and formation of onomatopoeic expressions. The study also revealed that Modern Standard Arabic showed influences of foreign languages (borrowing) in the process of forming noun categories. The study revealed eight major morphological affixations that make MSA more productive than English, which uses limited morphological processes to form the noun category. Thus, the findings illustrated that language with extensive inflectional morphological affixations espouses greater productivity in terms of diminutive functions.

Joseph ( 2005 ) suggests that ‘one of the initial language families to be familiar with, and accordingly the most meticulously examined of all so far, is the family that Greek belongs to or recognized by means of the Indo-European language family. This view regarding the genesis of these languages is further reinforced by “Grimm’s law about phonetic modification”, keeping in view their phonetic resemblances and systematic variations. According to early linguists like Gamkrelidze and Ivanow ( 1990 ), their reconstruction is based on ancestral Indo-European languages. The linguists’ view largely depends on Grimm’s Law about Lautverschiebung, i.e., sound modification, which refers to a group of consonants in languages that predictably displace one another due to the evolutionary nature of languages and enhance the aspects of pragmatic productivity.

English inflectional morphology is generally considered by its simplicity, which is revealed by its widespread use of default, base or uninflected forms. The inflectional morphology in English influences nouns, pronouns, verbs, and adjectives, besides a few adverbs (Karaminis and Thomas, 2010 ; McCarthy, 2002 ). These inflectional morphemes function similarly for all lexemes. Nonetheless, there also exist some irregular morphemes. For instance, the words ‘take’ and ‘took’ create difficulties for non-native English language learners. English belongs to the West-Germanic branch of languages that are descended from the Indo-European group. Moreover, the West-Germanic branch is of particular interest for the reason that it is the branch from which the English language is derived (Baugh and Cable, 1993 ). In this way, Pashto seems inherently associated with the same group of languages, although it is a branch of the Iranian sub-group. Its main bordering languages currently consist of languages such as Persian, Tajik, Balochi, Kurdish, and Ossetian, spoken in the surrounding areas of Afghanistan (Habibullah and Robson, 1996 ).

Valeika and Buitkiene ( 2003 ) state that inflection in gender in old English was largely grammatical because nouns were disconnected by their grammar. Concerning morphological construction, old English is divided into three main distinct classes. For instance, masculine categories consisted of words such as ‘stan’ (stone), feminine ‘duru’ (door) and finally, ‘reced’ (house) used to indicate the neuter class. In this regard, the formal or grammatical gender disappeared over time with the loss of inflections in English. This aspect of dropping inflection in English seems to have largely decreased semantic and pragmatic productivity in it.

The gradual changes over time in the English language can be divided into three main historical periods regarding inflections that led to the reduction in its productivity. Baugh and Cable ( 1993 ) categorized these periods as (1) 450 to 1150 A.D., the Old English period, or the period of high inflections in the language when the endings in word forms like nouns, verbs, and adjectives were inseparable in terms of inflections; (2) 1100 to 1500 A.D., the Middle English period; and (3) 1500 to date. The Modern English and Middle English periods are considered the periods of “leveled inflection” or the periods of “loss of inflection”.

Many linguists have tried to find out the gender scheme of Indo-European languages in order to demarcate how these two kinds of gender, the grammatical gender and the biological gender, are communicated in a language in terms of inflections and pragmatic productivity (Corbett, 1991 ). Although gender is believed in some way to be unpredictable because it is a societal construct and not universal, some languages, such as Pashto, have strong gender inflections. In contrast, others, such as Persian, have totally lost them (Fernández, 2011 ).

Palmer ( 1984 ) believes that the Proto-language, a sub-branch of the Indo-European language family Greek, seems to be ‘highly inflectional in nature based on its grammatical composition as it cannot be separated’. He argues that the features of morphemes that exist in the Greek language can be classified into aspects like tense, gender, number, person, and case. Also, he associates the morphological structure of the English language with that of Greek by locating similarities and differences.

The available reviewed literature regarding the diminutive morphological function between English and other languages revealed that certain similarities and differences exist between them. These differentiate English in terms of morphological aspects and productivity from other languages worldwide. The reviewed studies identified a drastic gap in which no attention has been paid to the important aspect of comparison between English and Pashto to show the diminutive morphological function and reflect the semantic and pragmatic features of productivity in them.

Methodology

For the investigation, this research followed a qualitative design. The study is based on library research, where the researcher consulted different books about the target languages besides examining former studies on the characteristics of diminutive morphological analysis on some of the world languages. The study adopted the textual and archival interpretative analysis technique (Arabiat and Al-Momani, 2021 ). The design of the study is based on the framework of the Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis (CAH) proposed by (Lefer, 2011 ) and developed by (Krzeszowski, 2011 ; Chesterman, 1998 ; James 1980 ). The data of this study comprises the language segments of English and Pashto that include inflectional morphemes in two-word classes in terms of diminutive function with relation to nouns and adjective categories. Furthermore, personal observation for this data collection seemed preferable and suitable because of the researcher’s extensive exposure to the Pashto language as his First Language (L1) and English as a Second Language (L2), as well as the language of the researcher’s profession, i.e., being a teacher of English (Linguistics) for about 14 years. Traditional research methodologies and approaches such as recordings, interviews, and questionnaires do not suffice for the required information. Therefore, the researcher investigated comparative analysis through personal observation as a native speaker of Pashto and triangulated the analysis by consulting previous research findings and available literature on these two languages. The current study explores the following research questions:

What are the similarities and differences in diminutive morphological function and productivity between English and Pashto in nouns and adjective categories?

What is the degree of foreign influence of high inflectional languages, such as Greek, on the diminutive morphological function in English and Pashto?

The textual and archival interpretative analysis technique (Arabiat and Al-Momani, 2021 ) was adopted for this study. The reason for choosing this design was to compare and contrast the morphological function of diminutives in English and Pashto, which required a deeper understanding that could only be achieved through a corpus-based approach, as suggested by Arabiat and Al-Momani ( 2021 ). This methodology allowed for a comprehensive analysis of the data collected from various sources, including libraries and literary figures, to gain a better understanding of the similarities and differences in the diminutive morphological function of the two languages. The textual and archival interpretative analysis technique was deemed suitable for this research as it allowed for a detailed examination of the data and provided a means to interpret the findings in a meaningful way.

The corpus selection process prioritized peer-reviewed journals that focused on the function of morphology between English and Pashto. As no single study had been conducted to reveal the diminutive morphological function between these two languages, a review of available studies was necessary. Different libraries, such as Swat Public Library and Hazara University Library, were searched to find relevant studies. Over 80 corpus studies were consulted, and irrelevant studies were excluded and not cited in this study. Online research papers and theses were also reviewed, but only a few of them provided information on the morphological aspects of these languages, as cited in the text and the reference section of this study. To gain further insight into the investigation, the researcher approached literary figures in Pashto literature. Due to ethical considerations, the names of these individuals cannot be mentioned in this study.

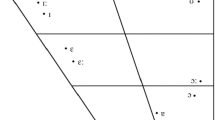

Data analysis and interpretation

The data is presented in the tables by incorporating two techniques known as linear tables and a theoretical discussion. The tables contain illustrations of inflectional morphemes in English and Pashto languages. Each table illustrates different uses of the morphemes for a specific way of speech in these languages, such as marking nouns. The instances demonstrated in the tables are additionally clarified by analytical discussion. Every aspect of a peculiar inflection in a certain word class is reasonably argued from various perspectives to determine the similarities and differences of morphology in English and Pashto concerning the diminutive function and productivity aspect of them.

Analysis and discussion

The findings revealed that the processes regarding the function of inflectional morphemes, particularly bound class morphemes, in Pashto and English, inflections like ‘s’ in English and ‘una’ in the Pashto language can never be used distinctly as meaningful segments in isolation. Rather, these morphemes can be seen attached to the nouns to mark plurality (Khan et al., 2016 ). In terms of inflectional morphology, Pashto has very extensive inflections by way of the phonological composition of its words. Consequently, the lexemes ending with ‘l’ sounds are constantly inflected with the inflection ‘una’, e.g., ‘pul’ a singular noun ending with ‘l’, changes to ‘Puluna’ in Pashto. The inflexion pattern for forming the plural in Pashto is morphologically more complex and productive than in English, where simply an’s’ or ‘es’ morpheme is added.

Similarities and differences between English and Pashto

The English language typically follows the addition of ‘s’ as an inflection. However, certain exceptions exist, for example changing the vowel sound of ‘man’ to ‘men’, ‘thesis’ to ‘theses’ and ‘analysis’ to analyses’. On the other hand, Pashto morphology largely depends on animacy, gender and the case of declensions in forming plurality (Lange, 2015 ). The masculine and feminine, direct and oblique cases are the distinguishing characteristics of Pashto. The final segment of the noun and the initial segment of the suffixes that attach to the words often change phonologically by forming plural in the Pashto language (David, 2013 ). Table 1 provides examples regarding the cases of declensions in the Pashto language and shows various inflectional patterns in the formation of nouns and level of productivity through the reduplication of the diminutive function.

Pashto is rich in inflections compared to English since it employs several diminutives in a variety of ways, while English uses just a few. Almost every noun category, which is similar in function to Bantu, refers to singular and plural and shows smallness, but the pragmatic context varies from that of English. In Pashto, smallness is often associated with demonstrating contempt, such as the word ‘motor’ being used for a single car, ‘motary’ for many cars and ‘motargay’ referring to a small car that conveys a pejorative sense. The noun ‘halak’ as demonstrated in Table 1 , refers to a boy, ‘halak an ’ is used for plurality and ‘halak oty ’ is employed for conveying a pejorative connotation. Most of the time, the inflections ‘ty’, ‘tay’, ‘gy’and ‘gay’are suffixed to the noun category in Pashto to denote the diminutive function with certain exceptions such as the noun ‘kor’ is used for a house, ‘kor akay ’ is used to convey the singular diminutive expression, while ‘kor oona ’ is employed for plural houses and the diminutive inflected form for the plural is ‘koraky’. The findings demonstrated that Pashto is rich in inflections as opposed to English and has various ways of expressing a particular meaning depending on the speaker’s intention. Moreover, the findings are dissimilar to the previous studies (Yahya, 2012 ) on the diminutive function between English and Arabic. In the Arabic Language, the diminutive largely reduces the size, quality, and quantity of an expression, but Pashto reflects an extensive mechanism in interaction. The study aligns with the findings by (Aronoff, 1976 ) that a language that has more than one form makes it dissimilar to other languages and creates the features of productivity in it.

Pashto has a vocative case used for addressing a person or thing, such as ‘halak’ used for a ‘boy’, but the vocative case is ‘halak a ’ and similarly, ‘spay’ is a noun meaning a dog, but in the vocative case, it changes to ‘spy ia ’. The vocative is a direct expression by the speaker to the addressee. Historically, the vocative case was the dominant feature of the languages descending from the ‘Indo-European family’, but over time they have lost it, though some of them, like modern Greek, Albanian and the Baltic languages such as Lithuanian, and Latvian still retain it. Almost all names about humans or animals are used with the inflectional morpheme like ‘a’ at the ending of the word, mostly in the case of masculine names, which denotes marking of the vocative case in proper masculine nouns in Pashto. On top of that, Pashto uses the vocative case to convey a diminutive function by employing an inflection form, such as the word ‘spa ia ’ (dog) is used for calling someone’s attention in a pejorative sense when the speaker shows anger to the addressee. Though the singular form of the word is ‘spay’ (dog), when changing it to a vocative case, it is inflected with ‘ ia ’ inflection and the meaning is changed. This feature of Pashto seems to be the sole diminutive function by employing a vocative case, using animal names to convey the highest contempt for humans, including both males and females. Even at times, the Pashto speakers use ‘Khar a ’ (donkey) as a vocative expression for the word ‘khar’ (donkey) to call the attention of someone with extreme abhorrence. The findings regarding the diminutive function of English are similar to the previous study conducted by (Karaminis and Thomas, 2010 ; McCarthy, 2002 ), which revealed that English inflectional morphology is generally considered by its simplicity, which is manifested by its widespread use of default, i.e., base or uninflected forms.

On the contrary, the vocative case is almost dropped in Modern English, although the meaning is communicated differently in a semantic context, such as ‘ Jim , are you serious?’’ and ‘ Alice , come here’ (Moro, 2003 ). In Modern English, the vocative expression is communicated through the nominative case and is distinct in the rest of the sentence by putting commas. Historically, Old English prefaced vocative expression in poetry and prose by using ‘O’ such as ‘ O ye of little faith’ (Beare and Mathers, 1981 ).

However, the Pashto language is more inflectional than English, as demonstrated by the findings in Table 1 . While English mainly confines itself to three kinds of inflections in forming plurality in noun categories such as ‘s’, ‘es’ and ‘zero’, Pashto has an oblique case as well as diminutives in noun categories that function differently from the diminutives available in English. English diminutives function to show the small size of the entity by adding suffixes like ‘-let’ as in ‘book let ’ which means a small book, ‘-ling’ as in ‘duck ling ’ used for a small duck, ‘-ock’ as in ‘hill ock ’ used for a small hill, ‘-ette’ as in ‘novel ette ’ used for a small novel with fewer pages, and ‘-net’ as in ‘coro net ’ meaning a small crown (Dehham and Kadhim, 2015 ). Diminutives are not a common feature of Standard English as found in other world languages. Wierzbicka ( 2009 ) argues that the form of productive diminutive in English rarely exists except in the isolated general forms used by the children such as ‘doggie’, ‘handies’ and ‘girlie’.The diminutives in semantic and pragmatic contexts extend beyond narrow perceptions and associations of meaning, such as in the English glossary. The diminutive morphological function of Pashto revealed a closer resemblance to the Bantu language researched by (Gibson et al., 2017 ), who argue that diminutives in Bantu entail encoding pejoration, affection, and admiration, as well as communicate disdain and contempt, which are the prospective uses alongside a mere concept of ‘young’. For example, in the Bantu language, the noun ‘or u vyo’ is used for a knife, but adding an inflection such as ‘o ka ruvyo’ changes the meaning to a small knife and adding another inflection like ‘o u tuvyo’ changes the meaning to represent knives.

Modern English mainly follows a predictable pattern for forming plurality in noun categories by adding affixes such as ‘s’, ‘es’, ‘en’, and zero morphemes. The affixation of ‘en’ for the formation of plurality in English is irregular inflection; zero morphemes are confined to several noun class words such as ‘sheep’ and ‘deer’. Moreover, the addition of the suffix ‘s’ to nouns like ‘table’, ‘dog’, ‘cat’, etc., turns them into plural, i.e., ‘tables’, ‘dogs’, and ‘cats’. English inflects the noun by ‘es’ and changes it to plural, such as the word ‘watch’, by adding ‘es’, turns into plural. The pattern of vowel alteration exists in the formation of plurality in certain English nouns, and the vowel structure undergoes changes, but the morphological patterns stay the same such as ‘goose’ changes into ‘geese’. The inflection of vowel alterations, also known as ablauts and umlauts, is particularly used in the language by inflecting the words through the alteration of the sounds, such as in German. These kinds of inflections occur due to the alteration of vowel sounds in English that changes the noun to plural. The internal phonological structure of the word is changed, and resultantly, the meaning also gets altered. Similarly, the word ‘ox, and ‘child’ are singular nouns, but the addition of ‘en’ and ‘ren’ changes them to ‘oxen’ and ‘children’, respectively. The alteration of sounds and irregular inflection exists in English lexicology but is confined to minimal English words. Resultantly, reduces productivity in terms of pragmatic and diminutive context. On the other hand, Pashto has an extensive system of noun declension that constitutes a rich mechanism by employing plurality, vocative case, and diminutive inflections with a wide spectrum of appreciative and depreciative expressions that lead to pragmatic productivity and enhance diminutive effects. This is illustrated in Table 2 , where the symbol ‘ǿ’ demonstrated zero inflection which is quite consistent as compared to Pashto. This is due to Modern English’s inflectional nature, which has extensively dropped the inflectional and archaic features of Old English. One reason is that English has undergone great changes, but Pashto seems to have stayed the same. This question is out of the current study’s scope and needs further research to be answered.

In English, the ‘s’ or ‘es’ inflection is a common phenomenon for marking plurality in noun class categories, but Pashto has a wide range of inflections depending on the final morpheme, particularly it’s being voiced or voiceless to determine the plural. For example, Pashto-nouns ending with ‘b’ like ‘kitab’ (book), ‘gulab’ (rose) and ‘sawab’ (virtue) form plural categories by adding the inflection ‘una’ such as ‘kitab una ’ (books), ‘gulab una ’ (roses) and ‘sawab una ’ (virtues). Similarly, the nouns ending with vowel sounds get the ‘ay’ inflection for plurality, such as the words ‘parda’ ( hijab ) and ‘jarga’ (council) are inflected with ‘ay’ to form plural categories like ‘pard ay ’( hijab ) and jarg ay ’ (councils) (Khan et al., 2016 ). However, the diminutive morphological function in Pashto is dissimilar and irregular in marking the lexical items. Unlike English, which only forms plurality, Pashto goes beyond marking plurality, such as carrying the inflections ‘una, and ‘gay’. For the diminutive expressions, the word ‘kitab’, a singular book, inflects with ‘gay’ unlike ‘una’. For marking plural diminutives, the word ‘kitabuna’ (books) changes to ‘kitab gi ’; the inflection ‘gi’ indicates smallness or littleness about the books or refers to the limited knowledge of the addressee.

The English language typically uses two types of inflections in noun categories for marking genitive cases(possessive inflections). First, English employs for singular nouns to demonstrate genitive cases such as ‘John’s book’.Second, it uses (‘) for plural nouns to reveal possessive cases like ‘schools’ buses’. The English language is limited in terms of inflections in morphology in the noun classes, and similarly, its usage is also largely restricted compared to the Pashto language. Only two major dominant morphemes in English are often employed for marking plurality and demonstrating genitive cases such as ‘s’.

The noun class words in English do not mark gender as a general feature except in limited instances in which the isolated words refer to gender categories such as grandmother, granddaughter, aunt, niece, girls, mother, and wife, but these words function as isolated units, unlike affixation. English also has a generic category of nouns that denote general expressions such as heroine, air hostess, waitress, and princess. The categories of bound suffixes for marking gender are very limited to certain words, for example, lioness, hostess, and tigress, which are mostly restricted to the names of animals and hardly used for diminutive functions. Pashto, on the other hand, has an extended mechanism of inflections in noun categories related to animals for marking gender, such as ‘spay’ (dog) changes into ‘sp ai ’ (bitch), ‘oakh’ (camel) to ‘oakh a ’ (female camel), and ‘ghwa’ (cow) to ‘ghwa ya ’ (bull). The word ‘sp ai ’ (bitch) is used in Pashto for addressing a singular girl to denote a diminutive expression indicating contempt for someone, particularly for the women class. Similarly, the word ‘ghwa’ (cow) is also used in the Pashto language for addressing to show a pejorative and disdaining diminutive function for someone. Likewise, ‘ghwa y ’ (bull) is used for a singular man to convey a diminutive function such as being stupid or senseless. The Pashto language also seems to have a greater level of phonological modification in the process of forming plurality, as exemplified through the above names for animals, unlike the English Language. It is not only that English does not have phonological modifications through suffixation in these words, but it also lacks the process of forming plurality for the category of these nouns. It seems that English may have lost inflectional affixes for these nouns as they underwent transformational phases. That is why it does not bear the effects of inflectional features inherited from ancient languages, as does Pashto. The findings in this study are similar to the previous studies carried out by Fernández ( 2011 ) and Valeika and Buitkiene ( 2003 ) that some of the languages inherited from the same parental group have lost the inflections over time while others still retain them. Resultantly, the diminutive function of languages such as English is significantly affected by the loss of their morphological inflection that happened over time, making it susceptible to limit its productivity.

The findings demonstrated that the formation process of the noun category in Pashto is much more extensive and quite intricate than in English. The dissimilarity in terms of bound morphemes in nouns between the two languages is that inflections in the Pashto language include more diverse diminutive morphological functions. In contrast, the English language inflects its nouns merely for marking plurality and the genitive case by employing ‘s’ and ‘s’ in both cases, respectively. Conversely, the Pashto language inflects nouns in several ways, such as singular, plural, masculine, feminine, and the vocative case. Most importantly, as opposed to English, Pashto has a comprehensive system of diminutives that denotes a wide range of conveying semantic and pragmatic productivity, which are not available in the English glossary. Hence, the findings align with the previous studies that morphological inflection does not merely modify the form but facilitates productivity in a language (Arabiat and Al-Momani, 2021 ; Hazimy, 2006 ).

English does not have inflections for forming plurality in adjective categories, but Pashto has several cases that mark plurality depending on the context. The adjective ‘poor’ in English is used for an animate and inanimate entity without inflection. However, Pashto uses the word ‘poor’ to form a plurality, such as ‘gharib/gharib an ’, and uses it solely with animate masculine or feminine. Moreover, Pashto has two different categories of adjectives to denote the diminutive expressions used for the adjective poor, such as ‘khwar ano ’ and ‘ghariban ano ’. The inflection ‘ano’ attached to the root of the adjectives changes the connotation in a semantic and pragmatic context to indicate smallness and something depreciative. Compared to English, this morphological aspect of adjective formation in Pashto provides choices and productivity in the language for interlocutors in communication.

Unlike Pashto, the English language typically uses three broader categories in positive adjectives, comparative, and superlative, which are discrete like Pashto. Pashto is unique in marking adjectives through numbers, and masculine case, as the word ‘khkulay’ (beautiful) denotes masculine singular; for marking masculine plural, it changes to ‘khkul i ’, and the sound from ‘y’ changes to ‘i’, while for marking feminine plural the ending of the word changes to ‘ay’ sound which is similar to English diphthongization to indicate feminine plurality in Pashto such as ‘khkul ai ’. Similarly, the adjective ‘spin’ (white) denotes masculine singular, but for marking the feminine singular, the final segment of the word ‘spin’ gets ‘a’ inflection such as ‘spin a ’.For denoting the feminine plural, it changes to ‘spin y ’; the ‘y’ suffix changes the meaning and sound to reveal the gender. Finally, in pejorative expression, the plural feminine adjective ‘white’, ‘spin y ’ changes to ‘spin chakai ’, and the masculine plural white ‘spin o ’ changes to ‘spin chako ’ to convey the idea of disparaging someone.

Moreover, Pashto has a similar mechanism of employing the categorical system through adjectives by using words such as ‘lag ghat’ bigger and ‘der ghat’ ‘the biggest’, though pragmatic variations exist between the two languages in these terms. The English language strictly uses the comparative degree for comparing two groups and the superlative degree for more than two, but these adjectives do not make such distinctions in Pashto. Pashto is a vocative language because it inflects the adjectives to address the addressee by adding the suffix to the end of the word. For instance, ‘khkulay’ is an adjective used for beautiful, and it changes to ‘khkuli a ’. In addition, the inflection ‘a’ at the end of this adjective functions to call forth the attention of someone. In this context, the message is communicated by raising the pitch to attract the attention of the addressee. Hence, the word for the singular masculine ‘khkuli a ’ (beautiful) signifies the speaker’s love for the addressee when used in an appreciative context and indicates the productivity of the Pashto language in employing adjectives. By using various inflections that change the tone and the final segment of the words to communicate the intended message, Pashto is a pragmatically rich language compared to English. The word ‘tone’ does not mean tonal language; it is used for the alteration of sounds that results due to the suffixes attached to the noun and adjective categories in Pashto.

Adjectives in English do not mark numbers and gender but only inflect the grammatical construction through gradable and non-gradable morphemes. Gradable adjectives in English are ‘small’ and ‘big’ used for comparative and superlative construction by employing ‘er’ and ‘est. Secondly, English does not have a system of denoting diminutives in adjective class except for certain general expressions in the noun category, while Pashto has a wide range of diminutive expressions in the formation of adjectives that makes it more productive in conveying multi-layers of connotations through a single unit. The findings regarding the declensions in adjective categories in English in this study are similar to the previous studies conducted by Bin Mukhashin ( 2018 ) and Naciscione ( 2010 ) in that it has an analytical diminutive marking mechanism that denotes a few lexical markers in distinctive forms such as ‘tiny’, ‘small’, and ‘little’ before the noun categories which limits its productivity and diminutive function.

The inflections in Old English indicate marking case, gender, and degree of comparison. In Middle English (1100 to 1500 A.D), the inflections for marking, gender, and case entirely dropped out. In Old English (450 to 1150 A.D), the adjective ‘eald’ (old) denoted masculine singular nominative case but inflected with ‘e’ for demonstrating masculine plural nominative case such as ‘ealde’ attached with the ‘e’ inflection. The word ‘eald’ (old) indicated a feminine singular nominative case in Old English but inflected for plurality with ‘ae’ to mark the feminine plural nominative case. Old English employed the adjective ‘eald’ (old) to denote-neuter singular nominative case. For indicating neuter plural nominative case, it was inflected with ‘e’ such as in ‘ealde’. The adjective used for marking masculine singular accusative case was ‘ealdne’ (old). For denoting the feminine singular, it changed to ‘ealde’ and the adjective was altered to ‘eald’ form to indicate the neuter singular accusative. The Old English language was a highly inflectional language that marked the number, gender, and case, unlike Modern English. Modern English has limited inflections in marking adjectives, while Pashto retains an extensive inflectional system that marks numbers, gender, and case and has a strong diminutive mechanism.

Influences of high inflectional languages on English and Pashto

The analysis demonstrated two distinct patterns of diminutive morphological function in nouns and adjective categories between English and Pashto. Interestingly, the findings revealed that the mechanism of inflection in Pashto associates it with ancient languages such as Greek because they were highly inflectional and, consequently, facilitated productivity in communication to a larger extent. In Ancient Greek, all words were formed through inflectional suffixes such as ‘eu’ that denote masculine, feminine, singular, and plural. This element plays an important role in the distinction of gender. ‘Wall’ in Greek denotes masculine gender, while ‘door’ refers to feminine and ‘floor’ is neutral. All nouns and adjectives are peculiar for the inflection of nominative, accusative, and vocative cases and reflect the language’s productivity aspects (Davies, 1968 ). These characteristics of the Greek language are common to Pashto in marking the nouns and adjectives on the one hand and distinguishing English from Pashto on the other. Swanson ( 1958 ) argues that in the Greek language, there exist eight different types of diminutives used by Aristophanes for producing various kinds of comic formation in the text. Watt ( 2014 ) ascertains that in Modern Greek, the diminutives play a depreciative function through adjectives and nouns. An adjective such as ‘ksinos’ is used to indicate ‘sour’ in Modern Greek, but to denote a diminutive connotation, it changes to ‘ksino tsiko s’, which means ‘sourish’. Similarly, the adjective ‘askimos’ meaning ‘ugly’ changes to ‘askimu li s’ to convey a diminutive expression. Modern Greek has an extensive noun and adjective formation process through inflectional morphemes, which provide choices to the interlocutors, conveying a wide spectrum of semantic and pragmatic connotations. The classical Greek language had numerous diminutive morphological compositions. It carried a variety of inflectional morphemes in terms of nouns and adjectives that represented many declensions (word endings). Furthermore, these grammatical associations were represented by the endings as well as in-fixations of the nouns and adjectives rather than any other external isolated segments.

Greek is considered a highly inflectional language because the suffixes attached to the end of the words mark all cases, but English employs a has a simple and predictable mechanism for marking genitive cases (possessive). The genitive case is represented by the inflection ‘s’, for example, in the word ‘boy’ ‘boys’, and ‘girl’ ‘girls’. The Pashto language has a different system that includes numbers, gender, and case. The vocative case, which morphologically marks the masculine as well as the feminine, like the word ‘mashom’ (baby), denotes a masculine singular baby, and the declension form ‘mashom an ’ indicates the plural ‘babies’., The inflected form ‘mashom a ’ represents the feminine singular baby, and the inflected form ‘mashom ano ’ shows the vocative plural form. Interestingly, even all these words could convey a diminutive function depending on the intention of the speaker to employ them either in a pragmatic context by simply conveying the literal meaning or making it a depreciative expression to convey the meaning that someone is adult, but yet acts like a child or is being silly (Table 3 ).

Pashto seems to be as similar to Greek as it is different from English in diminutive morphological function. Both Pashto and Greek retain grammatical gender where all nouns and adjectives are categorized according to the gender system employed by the grammar in their languages and, consequently, have a higher level of productivity. The only variation between Pashto and Greek gender patterns is that the neutral gender does not exist in Pashto. Hence, the Pashto morphological system of nouns and adjectives is largely influenced by the Greek morphological system than by English. However, to a certain extent, English and Pashto inflectional morphology, particularly in terms of nouns, is similar to that of the Greek language. Here, the findings resonate with the previous studies carried out by Fernández ( 2011 ) and Valeika and Buitkiene ( 2003 ), who assert that of the languages descended from the same parental group, some have lost the inflections over time while others still retain them as in the case of Pashto.

Two basic reasons account for the dissimilarity of the inflectional mechanism in these two languages. First, Cook ( 1985 ) argues that Chomsky’s theory about Universal Grammar divides languages into two components: parameters and principles. Every natural language operates in similar principles, but the parametric variations bifurcate them into different sections and, resultantly, involve dissimilar morphological functions. Second, all-natural languages of the world are non-linear, i.e., they are emerging and open to changes due to the evolutionary process involved over time. Kozulin ( 2003 ) argues that new lexemes enter into languages due to socio-cultural impacts on languages. Kozulincompared the evolution of natural languages with the eddy of water, which gyrates across and changes into multiple shapes. Every language attains new features to serve the grammatical, pragmatic, and semantic components, dropping out many archaic features. Similarly, all modern languages, English, for example, have lost the inflectional features it inherited from parental proto-languages to a greater extent. Old English had rich morphological inflections and was known as a highly inflectional language, but it is no longer inflectional. In this way, it is logical to ascertain that English has given up the influences from complex Greek morphology to a larger extent. As a result, Modern English has extensively lost the diminutive function and productivity in a pragmatic context. Conversely, Pashto retains significant productivity in contrast to English. By virtue of being more inflectional like Greek, it seems to be morphologically closer to the Greek language in function than English and has an extensive diminutive morphological mechanism.

This study examined the diminutive morphological function in noun and adjective categories between Pashto and English. The data analysis revealed that Pashto and English have a distinct pattern of diminutive morphological function in nouns and adjectives despite certain similarities in noun class. The noun’s inflectional pattern in English marks it for plurality, generally known as the number. As for adjectives, they are employed to add to the meaning of nouns. Contrary, inflectional bound morphemes in the Pashto function for marking numbers, gender, case, and other features besides a wide range of diminutives’ semantic and pragmatic functions. Significantly, the findings revealed that the diminutive morphological function in Pashto is quite the opposite of English. The diminutive function in Pashto is similar in fashion to that of Swahili, Bantu, and Greek languages, making it more productive than English. By way of the similarities in the use of declensions, Pashto seems closer and more similar to Greek than to English. The diminutive morphological patterns of Greek and Pashto mark common nouns and adjectives for plurality, i.e., number and vocative case. Moreover, both languages mark masculine and feminine, i.e., gender, the case features even more strikingly, have a vast mechanism of employing diminutive connotations compared to English.

The following recommendations are made for future researchers to investigate the questions raised in this study, which were left unanswered due to the limitation of this study. Further investigation into the use and function of diminutives in other languages, such as Swahili, Bantu, and Greek, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms and variations in diminutive morphological function across languages. A comparative study of the diminutive morphological function in other similar languages, such as Urdu and Hindi, to explore the similarities and differences in their diminutive systems. An investigation into the potential impact of cultural factors on the use and perception of diminutives, such as how they are used in different social settings and reflect cultural values and attitudes.

This study has contributed to understanding the diminutive morphological function in Pashto and English, revealing distinct patterns and differences in their use of diminutives in noun and adjective categories. The findings suggest that Pashto employs a wide range of diminutive semantic and pragmatic functions, making its diminutive morphological function more productive than English. Moreover, the study has revealed similarities between the diminutive systems of Pashto and Greek, adding to our understanding of the historical and cultural influences on language development. This study has significant implications for language teaching and learning, especially for those learning Pashto or English as a second language.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this research as no data were generated or analyzed.

Ali A, Khan B, Awan N (2016) Contrastive analysis of the English and Pashto adjectives. Glob Lang Rev 1(1):74–84

Article Google Scholar

Arabiat RM, Al-Momani IM (2021) Diminution in Arabic: a suggested strategy to Mona Baker’s non-equivalence problem “differences in form”. J Lang Linguist Stud 18:1

Google Scholar

Aronoff M (1976) Word formation in generative grammar. Linguist Inq Monogr 1:1–134

Baker M (1992) A coursebook on translation. Routledge, London

Baugh AC, Cable T (1993) A history of the English language. Routledge, London, England

Beare FW, Mathers A (1981) The gospel according to Matthew: a commentary. Blackwell, Oxford

Chesterman A (1998) Contrastive functional analysis, vol. 47. John Benjamins Publishing, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Cook VJ (1985) Chomsky’s universal grammar and second language learning. Appl Linguist 6(1):2–18

Corbett GG (1991) Gender. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

David A (2013) Descriptive grammar of Pashto and its dialects, vol. 1. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany

Davies AM (1968) Gender and the development of the Greek declensions. Trans Philol Soc 67(1):12–36

Dehham SH, Kadhim HM (2015) The problematic use of noun diminutive forms in English. J Hum Sci 4(22):1–18

Drake S (2018) The form and productivity of the Maltese morphological diminutive. Morphology 28(3):297–323

Fernández R (2011) Does culture matter? In Handbook of social economics, vol. 1. pp 481–510. North-Holland

Gamkrelidze TV, Ivanov VV (1990) The early history of Indo-European languages. Sci Am 262(3):110–116

Gibson H, Guerois R, Marten L (2017) Patterns and developments in the marking of diminutives in Bantu. Nord J Afr Stud 26(4):40

Grandi N (2015) Edinburgh handbook of evaluative morphology. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, Scotland

Habibullah T, Robson B (1996) A reference grammar of Pashto; Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, DC

Hägg AT (2016) A contrastive study of English and Spanish synthetic diminutives. Master’s thesis

Hazimy O (2006) Diminution in Arabic language. Um Al-Qura University, Mecca, Saudi Arabia, pp. 1–16

von Humboldt W, von Humboldt FW (1999) Humboldt: ‘on language’: On the diversity of human language construction and its influence on the mental development of the human species. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England

Ibrahim AI (2010) Noun formation in Standard English and Modern Standard Arabic: a contrastive study. J Lang Teach Res 1:5

James C (1980) Contrastive analysis. Longman, London

Joseph BD (2005) The Indo-European family—the linguistic evidence. History of the Greek Language from the beginnings up to later antiquity, pp 128–134

Jurafsky D (1996) Universal tendencies in the semantics of the diminutive. Language, 72(3), 533–578. Linguistic Society of America, Washington, DC

Karaminis T, Thomas M (2010) A cross-linguistic model of the acquisition of inflectional morphology in English and Modern Greek. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, vol. 32, no. 32

Kazemian B, Hashemi S (2014) A contrastive linguistic analysis of inflectional bound morphemes of English, Azerbaijani and Persian languages: a comparative study. J Educ Hum Dev 3(1):593–614

Kempe V, Brooks PJ, Gillis S, Samson G (2007) Diminutives facilitate word segmentation in natural speech: cross-linguistic evidence. Mem Cogn 35(4):762–773

Khaled (2018) Diminutives in English and Hadhrami Arabic. J Humanit 15(1):2018

Khan A, Sohail A (2021) Teachers’ communication strategies in ESL/EFL Pakistani classrooms at intermediate level. Kashmir J Lang Res 24:1

CAS Google Scholar

Khan S, Akram W, Khan A (2016) Functions of inflectional morphemes in English and Pashto languages. J Appl Linguist Lang Res 3(1):197–216

Kozulin A (2003) Psychological tools and mediated learning. Vygotsky’s educational theory in cultural context, pp 15–38

Krzeszowski TP (2011) Contrasting languages: The scope of contrastive linguistics, vol. 51. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany

Lange N (2015) Nominal plurality in languages of the Greater Hindukush

Lefer MA (2011) Contrastive word-formation today: retrospect and prospect. Pozn Stud Contemp Linguist 47(1):645

Manova S, Knell G (2021) Two-suffix combinations in native and non-native English. In All things morphology: Its independence and its interfaces (pp. 305–323). John Benjamins, Amsterdam, Netherlands

McCarthy AC (2002) An introduction to English morphology: words and their structure. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Momma H, Matto M (eds) (2009) A companion to the history of the English language. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ

Moro A (2003) Notes on vocative case. A case study in clause structure. Amst Stud Theory History Linguist Sci Ser 4:247–262

Bin Mukhashin KH (2018) Diminutives in English and Hadhrami Arabic. Hadhramout Univ J Humanit 15:257–266

Naciscione A (2010) Stylistic use of phraseological units in discourse. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Nazary M (2008) The role of L1 in L2 acquisition: attitudes of Iranian university students. Novitas-ROYAL 2:2

Palmer FR (1984) Grammar: A concise explanatory guide to the complex set of relations that links the sounds of the language, or its written symbols, with the message they have to convey. Penguin Books Publishers, London, England

Palmer FR (2001) Mood and modality. Cambridge University Press

Salim JA (2013) A contrastive study of English-Arabic noun morphology. Int J English Linguist 3(3):122

Schneider KP (2003) Diminutives in English. Max Niemeyer Verlag Gmbh, Tübingen

Shamsan MAHA, Attayib AM (2015) Inflectional morphology in Arabic and English: a contrastive study. Int J English Linguist 5(2):139

Swanson DC (1958) Diminutives in the Greek New Testament. J Biblic Lit 77:134–151

Valeika L, Buitkienė J (2003) An introductory course in theoretical English grammar

Wang Z (2020) The analysis of diminutive in Lingchuan dialect from the phonological and morphological aspect. Open Access Lib J 7(6):1–6

Watt JM (2014) Diminutive suffixes in the Greek New Testament: a cross-linguistic study. Biblic Ancient Greek Linguist 2(2):29

Wierzbicka A (2009) Cross-cultural pragmatics. De Gruyter, Mouton

Yahya M (2012) The theoretical, semantic, and aesthetic aspects for analysing and grammaticalizing diminution in Sibaweh’s Book. Tishreen Univ J Res Sci Stud Art Humanit Ser 34(4):2013

Yule G (2016) The study of language. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England

Zuhra F, Khan A (2009) A corpus-based finite-state morphological analyzer for Pashto. In Proceedings of the Conference on Language & Technology

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

English Language Skills Department (ELSD), Common First Year Al Khaleej Training and Education-King Saud University, Science Building, Second Floor, Office: 2182, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AK visited libraries, collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. He was responsible for the study’s design and the paper’s critical review. AK read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Afzal Khan .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any study with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Khan, A. The diminutive morphological function between English and Pashto languages: a comparative study. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 536 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02004-2

Download citation

Received : 14 March 2023

Accepted : 28 July 2023

Published : 28 August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02004-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Welcome to our website!

Thank you for visiting Pohyar Dictionary website! This dictionary offers a comprehensive resource for users to search for words in Pashto, English, Dari, and Arabic. It allows for translation between English and Pashto or Dari, as well as between Pashto, Dari, and Arabic. It is a valuable tool for non-Afghans who wish to learn Pashto or Dari. The dictionary includes 400K words in various fields such as legal, medical, literature, and more. Additionally, we offer professional translation services, writing and editing in Pashto, and teaching Pashto to Afghans abroad.

Pohyar Dictionary

We have a selection of dictionaries available to suit your needs. You can choose from the following options to translate words, phrases, or expressions:

Proper Pronunciation Rules in English

English pronunciation can be challenging because it is not always consistent or predictable. However, there are some general rules and patterns that can help you improve your pronunciation. Here are some key guidelines:

- Pay attention to vowel sounds: English has 12 vowel sounds, but only five vowel letters (A, E, I, O, U). It's important to learn the different ways these letters can be pronounced, such as the "a" in "cat" versus the "a" in "cake." Listen carefully to native speakers and try to imitate their vowel sounds.

- Watch out for silent letters: English has many silent letters, such as the "k" in "knight" or the "b" in "comb." Pay attention to spelling and try to memorize words with silent letters to avoid mispronunciation.

- Learn stress and intonation patterns: English is a stress-timed language, which means that stressed syllables are pronounced more prominently than unstressed syllables. Intonation patterns, such as rising or falling pitch, can also change the meaning of a sentence. Practice stress and intonation patterns to sound more natural and expressive.

- Practice consonant clusters: English has many consonant clusters, or groups of consonants that appear together in a word. For example, "strength" has six consonant sounds in a row. Practice pronouncing these clusters slowly and clearly, and gradually increase your speed.

- Listen and repeat: The best way to improve your pronunciation is to listen to native speakers and practice imitating their sounds. Watch movies, listen to music, and speak with native speakers whenever possible to improve your pronunciation and gain confidence.

Remember, mastering English pronunciation takes time and practice. Don't be discouraged if you don't get it right the first time. Keep practicing and you'll get there!

How to Memorize Words

- Repetition: One of the most effective ways to memorize words is through repetition. Repeat the word several times until it sticks in your mind.

- Create associations: Create a mental association or connection between the word and something else that you already know. For example, you can associate the word "apple" with the color red or with a fruit.

- Use visual aids: Use pictures, diagrams, or videos to help you remember the word. Visual aids can help you to create a stronger mental image of the word.

- Use context: Learn new words in context. Reading a sentence or a paragraph that includes the word you want to learn will help you to understand its meaning and remember it better.

- Use mnemonics: Create a mnemonic device, such as a rhyme, acronym, or phrase that helps you to remember the word. For example, the word "HOMES" can help you remember the names of the Great Lakes (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior).

- Break words into smaller parts: If a word is difficult to remember, break it down into smaller parts. Focus on the smaller parts first, and then work on putting them together to form the complete word.

- Use flashcards: Create flashcards with the word on one side and the definition on the other. Review the flashcards regularly until you have memorized the words.

- Practice, practice, practice: The more you use a word, the easier it is to remember. Use new words in sentences or in conversations to help you remember them.

- Use technology: There are many apps and websites that can help you to memorize words. Some of these apps use gamification techniques to make learning more fun and engaging.

- Stay motivated: Learning new words can be challenging, but don't give up! Stay motivated and keep practicing. The more words you learn, the easier it becomes to learn new ones.

How to Say Hypothesis in Pashto

- hypoglycemia

- hypothermia

- hypothesize

- hypothetical

- hypothetically

- connotation

- full rights

- once in a while

- postal service

Hypothesis meaning in Pashto

Hypothesis meaning in Pashto. Here you learn English to Pashto translation / English to Pashto dictionary of the word ' Hypothesis ' and also play quiz in Pashto words starting with H also play A-Z dictionary quiz . To learn Pashto language , common vocabulary and grammar are the important sections. Common Vocabulary contains common words that we can used in daily life. This way to learn Pashto language quickly and learn daily use sentences helps to improve your Pashto language. If you think too hard to learn Pashto language, 1000 words will helps to learn Pashto language easily, they contain 2-letter words to 13-letter words. Below you see how to say Hypothesis in Pashto.

How to say 'Hypothesis' in Pashto

Learn also: Hypothesis in different languages

Play & Learn Pashto word starts with H Quiz

Top 1000 pashto words.

Here you learn top 1000 Pashto words, that is separated into sections to learn easily (Simple words, Easy words, Medium words, Hard Words, Advanced Words). These words are very important in daily life conversations, basic level words are very helpful for beginners. All words have Pashto meanings with transliteration.

Daily use Pashto Sentences

Here you learn top Pashto sentences, these sentences are very important in daily life conversations, and basic-level sentences are very helpful for beginners. All sentences have Pashto meanings with transliteration.

Pashto Vocabulary

Pashto Grammar

Pashto dictionary.

Fruits Quiz

Animals Quiz

Household Quiz

Stationary Quiz

School Quiz

Occupation Quiz

All languages

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

PASHTO LANGUAGE: SOLVING THE MYSTERIES OF THE PAST TENSE

Related Papers

Ghani Abdur Rahman

The tense driven asymmetry of the Pashto clause is analyzed from the perspective of the minimalist framework The study proves that the split ergativity in Pashto is tense based and does not have the aspect driven features proposed by Roberts 2000 The study argues that the object is assigned a theta role by the V and the subject is assigned a theta role by the little v The accusative case is assigned by the little v but the nominative and ergative cases are assigned by T It claims that the T head assigns multiple cases as the split ergativity is tense driven It highlights the syntactic effects of the possible phonological processes in combining some of the closely adjacent words and making a single phonological word The study also discusses clitic placement and prosodic inversion to refute the assumption that perfective feature is a strong feature in Pashto

naghme ghasemi

Ibrahim Khan

The purpose of this article is to get a glimpse of a possible connection between the Karlāṇ dialects and the Tarino dialect; despite the geographical distance between the dialects. This article will explore lexical and phonological features of the two dialects. This dialect is known to Iranianologists as "Wanetsi"; I have used the term Tarino which is the term used by the dialect speakers use to self-identify the dialect.

Emil Perder

Languages of Northern Pakistan: Essays in Memory of Carla Radloff

Henrik Liljegren