Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory posits that an individual’s development is influenced by a series of interconnected environmental systems, ranging from the immediate surroundings (e.g., family) to broad societal structures (e.g., culture).

These systems include the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem, each representing different levels of environmental influences on an individual’s growth and behavior.

Key Takeaways

- Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory views child development as a complex system of relationships affected by multiple levels of the surrounding environment, from immediate family and school settings to broad cultural values, laws, and customs.

- To study a child’s development, we must look at the child and their immediate environment and the interaction of the larger environment.

- Bronfenbrenner divided the person’s environment into five different systems: the microsystem, the mesosystem, the exosystem, the macrosystem, and the chronosystem.

- The microsystem is the most influential level of the ecological systems theory. This is the most immediate environmental setting containing the developing child, such as family and school.

- Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory has implications for educational practice.

The Five Ecological Systems

Bronfenbrenner (1977) suggested that the child’s environment is a nested arrangement of structures, each contained within the next. He organized them in order of how much of an impact they have on a child.

He named these structures the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem and the chronosystem.

Because the five systems are interrelated, the influence of one system on a child’s development depends on its relationship with the others.

1. The Microsystem

The microsystem is the first level of Bronfenbrenner’s theory and is the things that have direct contact with the child in their immediate environment.

It includes the child’s most immediate relationships and environments. For example, a child’s parents, siblings, classmates, teachers, and neighbors would be part of their microsystem.

Relationships in a microsystem are bi-directional, meaning other people can influence the child in their environment and change other people’s beliefs and actions. The interactions the child has with these people and environments directly impact development.

For instance, supportive parents who read to their child and provide educational activities may positively influence cognitive and language skills. Or children with friends who bully them at school might develop self-esteem issues. The child is not just a passive recipient but an active contributor in these bidirectional interactions.

2. The Mesosystem

The mesosystem is where a person’s individual microsystems do not function independently but are interconnected and assert influence upon one another.

The mesosystem involves interactions between different microsystems in the child’s life. For example, open communication between a child’s parents and teachers provides consistency across both environments.

However, conflict between these microsystems, like parents and teachers blaming each other for a child’s poor grades, creates tension that negatively impacts the child.

The mesosystem can also involve interactions between peers and family. If a child’s friends use drugs, this may introduce substance use into the family microsystem. Or if siblings do not get along, this can spill over to peer relationships.

3. The Exosystem

The exosystem is a component of the ecological systems theory developed by Urie Bronfenbrenner in the 1970s.

It incorporates other formal and informal social structures. While not directly interacting with the child, the exosystem still influences the microsystems.

For instance, a parent’s stressful job and work schedule affects their availability, resources, and mood at home with their child. Local school board decisions about funding and programs impact the quality of education the child receives.

Even broader influences like government policies, mass media, and community resources shape the child’s microsystems.

For example, cuts to arts funding at school could limit a child’s exposure to music and art enrichment. Or a library bond could improve educational resources in the child’s community. The child does not directly interact with these structures, but they shape their microsystems.

4. The Macrosystem

The macrosystem focuses on how cultural elements affect a child’s development, consisting of cultural ideologies, attitudes, and social conditions that children are immersed in.

The macrosystem differs from the previous ecosystems as it does not refer to the specific environments of one developing child but the already established society and culture in which the child is developing.

Beliefs about gender roles, individualism, family structures, and social issues establish norms and values that permeate a child’s microsystems. For example, boys raised in patriarchal cultures might be socialized to assume domineering masculine roles.

Socioeconomic status also exerts macro-level influence – children from affluent families will likely have more educational advantages versus children raised in poverty.

Even within a common macrosystem, interpretations of norms differ – not all families from the same culture hold the same values or norms.

5. The Chronosystem

The fifth and final level of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory is known as the chronosystem.

The chronosystem relates to shifts and transitions over the child’s lifetime. These environmental changes can be predicted, like starting school, or unpredicted, like parental divorce or changing schools when parents relocate for work, which may cause stress.

Historical events also fall within the chronosystem, like how growing up during a recession may limit family resources or growing up during war versus peacetime also fall in this system.

As children get older and enter new environments, both physical and cognitive changes interact with shifting social expectations. For example, the challenges of puberty combined with transition to middle school impact self-esteem and academic performance.

Aging itself interacts with shifting social expectations over the lifespan within the chronosystem.

How children respond to expected and unexpected life transitions depends on the support of their ecological systems.

The Bioecological Model

It is important to note that Bronfenbrenner (1994) later revised his theory and instead named it the ‘Bioecological model’.

Bronfenbrenner became more concerned with the proximal development processes, meaning the enduring and persistent forms of interaction in the immediate environment.

His focus shifted from environmental influences to developmental processes individuals experience over time.

‘…development takes place through the process of progressively more complex reciprocal interactions between an active, evolving biopsychological human organism and the persons, objects, and symbols in its immediate external environment.’ (Bronfenbrenner, 1995).

Bronfenbrenner also suggested that to understand the effect of these proximal processes on development, we have to focus on the person, context, and developmental outcome, as these processes vary and affect people differently (Bronfenbrenner & Evans, 2000).

While his original ecological systems theory emphasized the role of environmental systems, his later bioecological model focused more closely on micro-level interactions.

The bioecological shift highlighted reciprocal processes between the actively evolving individual and their immediate settings. This represented an evolution in Bronfenbrenner’s thinking toward a more dynamic developmental process view.

However, the bioecological model still acknowledged the broader environmental systems from his original theory as an important contextual influence on proximal processes.

The bioecological focus on evolving person-environment interactions built upon the foundation of his ecological systems theory while bringing developmental processes to the forefront.

Classroom Application

The Ecological Systems Theory has been used to link psychological and educational theory to early educational curriculums and practice. The developing child is at the center of the theory, and all that occurs within and between the five ecological systems are done to benefit the child in the classroom.

- According to the theory, teachers and parents should maintain good communication with each other and work together to benefit the child and strengthen the development of the ecological systems in educational practice.

- Teachers should also be understanding of the situations their student’s families may be experiencing, including social and economic factors that are part of the various systems.

- According to the theory, if parents and teachers have a good relationship, this should positively shape the child’s development.

- Likewise, the child must be active in their learning, both academically and socially. They must collaborate with their peers and participate in meaningful learning experiences to enable positive development (Evans, 2012).

There are lots of studies that have investigated the effects of the school environment on students. Below are some examples:

Lippard, LA Paro, Rouse, and Crosby (2017) conducted a study to test Bronfenbrenner’s theory. They investigated the teacher-child relationships through teacher reports and classroom observations.

They found that these relationships were significantly related to children’s academic achievement and classroom behavior, suggesting that these relationships are important for children’s development and supports the Ecological Systems Theory.

Wilson et al. (2002) found that creating a positive school environment through a school ethos valuing diversity has a positive effect on students’ relationships within the school. Incorporating this kind of school ethos influences those within the developing child’s ecological systems.

Langford et al. (2014) found that whole-school approaches to the health curriculum can positively improve educational achievement and student well-being. Thus, the development of the students is being affected by the microsystems.

Critical Evaluation

Bronfenbrenner’s model quickly became very appealing and accepted as a useful framework for psychologists, sociologists, and teachers studying child development.

The Ecological Systems Theory provides a holistic approach that is inclusive of all the systems children and their families are involved in, accurately reflecting the dynamic nature of actual family relationships (Hayes & O’Toole, 2017).

Paat (2013) considers how Bronfenbrenner’s theory is useful when it comes to the development of immigrant children. They suggest that immigrant children’s experiences in the various ecological systems are likely to be shaped by their cultural differences. Understanding these children’s ecology can aid in strengthening social work service delivery for these children.

Limitations

A limitation of the Ecological Systems Theory is that there is limited research examining the mesosystems, mainly the interactions between neighborhoods and the family of the child (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Therefore, the extent to which these systems can shape child development is unclear.

Another limitation of Bronfenbrenner’s theory is that it is difficult to empirically test the theory. The studies investigating the ecological systems may establish an effect, but they cannot establish whether the systems directly cause such effects.

Furthermore, this theory can lead to assumptions that those who do not have strong and positive ecological systems lack in development. Whilst this may be true in some cases, many people can still develop into well-rounded individuals without positive influences from their ecological systems.

For instance, it is not true to say that all people who grow up in poverty-stricken areas of the world will develop negatively. Similarly, if a child’s teachers and parents do not get along, some children may not experience any negative effects if it does not concern them.

As a result, people need to avoid making broad assumptions about individuals using this theory.

How Relevant is Bronfenbrenner’s Theory in the 21st Century?

The world has greatly changed since this theory was introduced, so it’s important to consider whether Bronfenbrenner’s theory is still relevant today.

Kelly and Coughlan (2019) used constructivist grounded theory analysis to develop a theoretical framework for youth mental health recovery and found that there were many links to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory in their own more recent theory.

Their theory suggested that the components of mental health recovery are embedded in the ‘ecological context of influential relationships,’ which fits in with Bronfenbrenner’s theory that the ecological systems of the young person, such as peers, family, and school, all help mental health development.

We should also consider whether Bronfenbrenner’s theory fits in with advanced technological advancements in the 21st century. It could be that the ecological systems are still valid but may expand over time to include new modern developments.

The exosystem of a child, for instance, could be expanded to consider influences from social media, video gaming, and other modern-day interactions within the ecological system.

Neo-ecological theory

Navarro & Tudge (2022) proposed the neo-ecological theory, an adaptation of the bioecological theory. Below are their main ideas for updating Bronfenbrenner’s theory to the technological age:

- Virtual microsystems should be added as a new type of microsystem to account for online interactions and activities. Virtual microsystems have unique features compared to physical microsystems, like availability, publicness, and asychnronicity.

- The macrosystem (cultural beliefs, values) is an important influence, as digital technology has enabled youth to participate more in creating youth culture and norms.

- Proximal processes, the engines of development, can now happen through complex interactions with both people and objects/symbols online. So, proximal processes in virtual microsystems need to be considered.

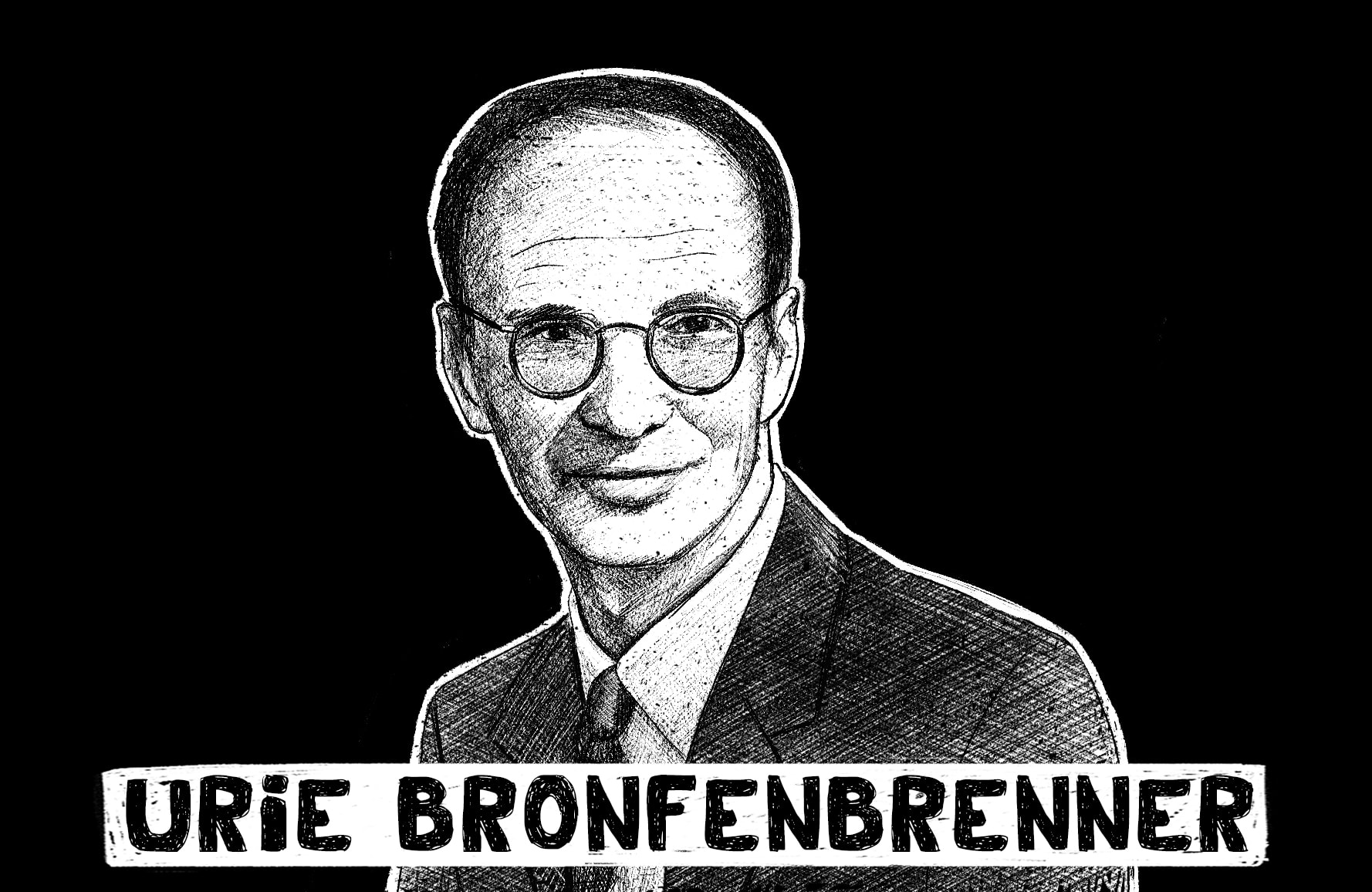

Urie Bronfenbrenner was born in Moscow, Russia, in 1917 and experienced turmoil in his home country as a child before immigrating to the United States at age 6.

Witnessing the difficulties faced by children during the unrest and rapid social change in Russia shaped his ideas about how environmental factors can influence child development.

Bronfenbrenner went on to earn a Ph.D. in developmental psychology from the University of Michigan in 1942.

At the time, most child psychology research involved lab experiments with children briefly interacting with strangers.

Bronfenbrenner criticized this approach as lacking ecological validity compared to real-world settings where children live and grow. For example, he cited Mary Ainsworth’s 1970 “Strange Situation” study , which observed infants with caregivers in a laboratory.

Bronfenbrenner argued that these unilateral lab studies failed to account for reciprocal influence between variables or the impact of broader environmental forces.

His work challenged the prevailing views by proposing that multiple aspects of a child’s life interact to influence development.

In the 1970s, drawing on foundations from theories by Vygotsky, Bandura, and others acknowledging environmental impact, Bronfenbrenner articulated his groundbreaking Ecological Systems Theory.

This framework mapped children’s development across layered environmental systems ranging from immediate settings like family to broad cultural values and historical context.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological perspective represented a major shift in developmental psychology by emphasizing the role of environmental systems and broader social structures in human development.

The theory sparked enduring influence across many fields, including psychology, education, and social policy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main contribution of bronfenbrenner’s theory.

The Ecological Systems Theory has contributed to our understanding that multiple levels influence an individual’s development rather than just individual traits or characteristics.

Bronfenbrenner contributed to the understanding that parent-child relationships do not occur in a vacuum but are embedded in larger structures.

Ultimately, this theory has contributed to a more holistic understanding of human development, and has influenced fields such as psychology, sociology, and education.

What could happen if a child’s microsystem breaks down?

If a child experiences conflict or neglect within their family, or bullying or rejection by their peers, their microsystem may break down. This can lead to a range of negative outcomes, such as decreased academic achievement, social isolation, and mental health issues.

Additionally, if the microsystem is not providing the necessary support and resources for the child’s development, it can hinder their ability to thrive and reach their full potential.

How can the Ecological System’s Theory explain peer pressure?

The ecological systems theory explains peer pressure as a result of the microsystem (immediate environment) and mesosystem (connections between environments) levels.

Peers provide a sense of belonging and validation in the microsystem, and when they engage in certain behaviors or hold certain beliefs, they may exert pressure on the child to conform. The mesosystem can also influence peer pressure, as conflicting messages and expectations from different environments can create pressure to conform.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood . Child development, 45 (1), 1-5.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development . American psychologist, 32 (7), 513.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1995). Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective .

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Evans, G. W. (2000). Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings . Social development, 9 (1), 115-125.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Ceci, S. J. (1994). Nature-nurture reconceptualised: A bio-ecological model . Psychological Review, 10 (4), 568–586.

Hayes, N., O’Toole, L., & Halpenny, A. M. (2017). Introducing Bronfenbrenner: A guide for practitioners and students in early years education . Taylor & Francis.

Kelly, M., & Coughlan, B. (2019). A theory of youth mental health recovery from a parental perspective . Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24 (2), 161-169.

Langford, R., Bonell, C. P., Jones, H. E., Pouliou, T., Murphy, S. M., Waters, E., Komro, A. A., Gibbs, L. F., Magnus, D. & Campbell, R. (2014). The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well‐being of students and their academic achievement . Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (4) .

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes . Psychological Bulletin, 126 (2), 309.

Lippard, C. N., La Paro, K. M., Rouse, H. L., & Crosby, D. A. (2018, February). A closer look at teacher–child relationships and classroom emotional context in preschool . In Child & Youth Care Forum 47 (1), 1-21.

Navarro, J. L., & Tudge, J. R. (2022). Technologizing Bronfenbrenner: neo-ecological theory. Current Psychology , 1-17.

Paat, Y. F. (2013). Working with immigrant children and their families: An application of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory . Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 23 (8), 954-966.

Rhodes, S. (2013). Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory [PDF]. Retrieved from http://uoit.blackboard.com

Wilson, P., Atkinson, M., Hornby, G., Thompson, M., Cooper, M., Hooper, C. M., & Southall, A. (2002). Young minds in our schools-a guide for teachers and others working in schools . Year: YoungMinds (Jan 2004).

Further Information

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Development, 45.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

A Comprehensive Guide to the Bronfenbrenner Ecological Model

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

d3sign/Moment/Getty images

- Five Ecological Systems

- Interactions

Bronfenbrenner's ecological model is a framework that can be utilized to understand the complex systems that influence human development . In particular, this model emphasizes the importance of environmental factors and social influences in shaping development and behavior.

The model takes a holistic approach, suggesting that child development involves a dynamic interaction between environment, societal, biological, and psychological factors. In Bronfenbrenner's model, there is a reciprocal interplay between the individual and the various levels of influence that affect development.

Introduction to the Bronfenbrenner Ecological Model

The theory suggests that a child's development is affected by the different environments that they encounter during their life, including biological, interpersonal, societal, and cultural factors.

What Does Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Model Describe?

This model describes the interactions between individuals and their environments and how these complex relationships affect development over time. According to this model, many interconnected systems make up a person's environment that all interact to influence and shape how people grow and respond.

The factors that influence development include a person's immediate setting and the broader culture in which they live.

The theory stresses the interdependency and interaction between people and their environments. Bronfenbrenner suggested that more nurturing and encouraging environments led to better developmental outcomes.

History and Development of the Model

This model, also known as the ecological systems theory, was introduced by Russian-American psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner. Bronfenbrenner was born in Russia and immigrated to the United States when he was six. His early experiences shaped his ideas about how children adjust to new environments and how factors such as environment, language, and culture can play a part in how children learn and grow.

Bronfenbrenner earned his PhD in developmental psychology from the University of Michigan in 1942. He began developing his influential theory during the 1970s and presented his ideas in his 1979 book "The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design." The book elaborated the key aspects of his theory.

Over time, Bronfenbrenner continued refining his ideas. In addition to emphasizing the importance of understanding how humans develop within their environmental contexts, he also stressed that this influence is bidirectional; humans also actively shape their surroundings.

Ecological systems theory has gained widespread acceptance, significantly influencing developmental psychology and related disciplines. The theory has also been applied in many different contexts, including family therapy , education, political policy, and social work .

Bronfenbrenner died in 2005, but his theory continues to profoundly influence our understanding of the dynamic interactions that affect how humans develop and change during childhood and throughout their lives.

Five Ecological Systems in Bronfenbrenner’s Model

Bronfenbrenner's theory is organized into a series of five nested systems or levels. The five main elements of Bronfenbrenner’s theory are the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem.

You can visualize the framework by imagining the individual at the center of a circle, surrounded by five concentric rings starting with the first circle (the microsystem) and expanding outward to the outermost circle (the chronosystem).

Microsystem

The microsystem is the innermost level, composed of an individual's immediate environment. It includes the people the person interacts with daily, including their family members, friends, classmates, teachers, and others.

The microsystem has the most direct, immediate impact on the individual.

The relationships and interactions within the microsystem are also bidirectional; people are influenced by their close contacts, but they also affect the people and environments around them. Because of these relationships' close, direct nature, they have a powerful effect on shaping an individual’s development and behavior.

Personal characteristics, including mental abilities, physical attributes, temperament, and personality , also impact a person's development.

A proposed update to Bronfenbrenner's theory suggests two types of microsystems: physical and virtual. Given the importance of digital influences on young people today, it is essential to recognize how virtual environments may influence child development.

The microsystem accounts for the experiences that directly involve and affect the individual and shape their behavior, learning, values, and beliefs.

The mesosystem is the next level of the model, comprised of all the relationships and interactions between the microsystems. Examples of mesosystems in a child’s life include the interactions between their family and school or between their friends and family.

Like the microsystem, the mesosystem has a direct effect on the individual.

The different microsystems are connected at this level. This means that changes in one microsystem can then impact other microsystems.

In other words, how these elements interact can influence how a child develops. For example, a child's family and school interaction can impact learning and academic performance.

The exosystem refers to environments in which the individual is not an active participant but still impacts development. This level encompasses the social context in which a person lives and other aspects of the environment, including government policies, social services, community resources, and mass media.

The individual does not have direct contact with these influences, but they still shape how a child develops.

For example, government policies and community resources impact a child's access to healthcare, quality child care, and education.

Macrosystem

The macrosystem involves the broader society and cultural forces that contribute to individual development. Important components of this level of Bronfenbrenner's theory include values, social norms, customs, traditions, ideology, and cultural beliefs.

These cultural beliefs are often shared by groups of people with a similar history or identity. Such beliefs can also shift over time. Such beliefs can also vary based on geographic location and socioeconomic status.

Chronosystem

The chronosystem is the outermost level of the model, accounting for the role that time plays in influencing individual development. This includes personal experiences that occur over the course of life, the various life transitions that people experience, historical events, and societal changes.

Challenges and transitions that can affect development, including the birth of siblings, moving to a new place, parental divorce, and the death of family members, can affect the family's dynamic or structure.

The model recognizes that environments are not static; they change over time, and these changes can have a significant effect on how people develop.

Interactions Among the Systems: A Dynamic View

The interactions between different systems in Bronfenbrenner's theory interact in intricate, bidirectional ways. The changes in one level can have a resounding impact on the other levels.

Examples of Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Model

You can better understand the different levels of Bronfenbrenner’s model by looking at examples of influences at each level:

Each system within the model interacts with other systems in complex ways. A child's family (microsystem), for example, can impact how they interact with others at school (microsystem). The relationship between these microsystems (the mesosystem), can then impact a child's behavior and academic success.

These systems don't just interact with the levels that proceed or follow them. And interactions that occur at one level can have cascading effects on other levels of influence

For example, workplace stress can impact how parents interact with their children at home. And economic changes that occur in a society (chronosystem) can influence the type of resources that are available in communities (exosystem), which can then play a role in the dynamics within individual families (microsystem).

By examining these influences more closely, we can gain a better appreciation of the dynamic interactions and interdependencies between the different levels of Bronfenbrenner's theory.

The Relevance of the Model Today

Bronfenbrenner's theory significantly impacted how researchers, psychologists, and educators view human development. The ecological model continues to inform our understanding of how children develop and how different aspects of their environment may positively or negatively impact their growth.

The framework’s holistic approach emphasizes the need to understand all aspects of a person's environment to appreciate the complex, interrelated factors that influence their development.

Some of the ways in which Bronfenbrenner's model has influenced our understanding of human development include:

The theory has been applied extensively within the field of education to help design effective learning environments that emphasize the classroom experience and focus on the influence of families, communities, societies, and the broader culture.

The early childhood education program, Head Start, is an example of an intervention informed by Bronfenbrenner's model. First introduced in 1965, Urie Bronfennbrenner served as a government advisor for the development of the program. The program takes a holistic approach and supports infants, toddlers, and preschoolers to promote school readiness.

Research suggests the program has numerous benefits, including the long-term effects of increased high school completion, college enrollment, and college completion.

Mental Health Care

The ecological model also plays a role in informing mental health care. Mental health treatments that take a holistic approach often lead to better outcomes. And looking at the community, societal, and cultural influences that affect a person's development and well-being can help mental health professionals understand the issues people face.

The framework has also affected approaches to mental health, both in terms of treatment and public policy. For example, it has contributed to the development of the ecological approach to counseling , which focuses on understanding personal and environmental factors when treating mental health issues.

Cultural Sensitivity

Because the model stresses how cultural factors can influence development, it can support greater cultural sensitivity among therapists , educators, and others.

Understanding ecological factors, for example, can produce greater cultural competency among therapists who work with diverse populations.

Bronfenbrenner's ecological model offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the many factors that affect development. In addiction to describing the different levels of influence, the ecological model also describes the dynamic interaction that occurs between the different levels, from the direct relationships at the microsystem level through the broader societal, cultural, and temporal factors that play a role.

Understanding these influences and their complex connections is important. By doing so, parents, educators, social program developers, and policy makers can gain greater insight and create supportive interventions that foster healthy development.

Tudge J, Maria Rosa E. Bronfenbrenner's ecological theory . In: Hupp S, Jewell J, eds. The Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Development . 1st ed. Wiley; 2020. doi:10.1002/9781119171492.wecad251

Haleemunnissa S, Didel S, Swami MK, Singh K, Vyas V. Children and COVID19: Understanding impact on the growth trajectory of an evolving generation . Child Youth Serv Rev . 2021;120:105754. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105754

Ceci SJ. Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005) . Am Psychol . 2006;61(2):173-174. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.2.173

Hyde LW, Gard AM, Tomlinson RC, Burt SA, Mitchell C, Monk CS. An ecological approach to understanding the developing brain: Examples linking poverty, parenting, neighborhoods, and the brain . Am Psychol . 2020;75(9):1245-1259. doi:10.1037/amp0000741

Navarro JL, Tudge JRH. Technologizing Bronfenbrenner: Neo-ecological Theory [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jan 21]. Curr Psychol . 2022;1-17. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-02738-3

Backonja U, Hall AK, Thielke S. Older adults' current and potential uses of information technologies in a changing world: A theoretical perspective . Int J Aging Hum Dev . 2014;80(1):41-63. doi:10.1177/0091415015591109

Zwemer E, Chen F, Beck Dallaghan GL, et al. Reinvigorating an academy of medical educators using ecological systems theory . Cureus . 2022;14(1):e21640. doi:10.7759/cureus.21640

Bailey MJ, Sun S, Timpe B. Prep school for poor kids: The long-run impacts of Head Start on human capital and economic self-sufficiency . Am Econ Rev . 2021;111(12):3963-4001. doi:10.1257/aer.20181801

Shafran R, Bennett SD, McKenzie Smith M. Interventions to support integrated psychological care and holistic health outcomes in paediatrics . Healthcare (Basel) . 2017;5(3):44. Published 2017 Aug 16. doi:10.3390/healthcare5030044

Eriksson M, Ghazinour M, Hammarström A. Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: what is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice ? Soc Theory Health . 2018;16(4):414-433. doi:10.1057/s41285-018-0065-6

Counseling Today. Using an ecological perspective .

Paat YF. Working with immigrant children and their families: an application of bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory . Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment . 2013;23(8):954-966. doi:10.1080/10911359.2013.800007

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

- PMC10801006

Review of studies applying Bronfenbrenner's bioecological theory in international and intercultural education research

1 School of International Education, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

Irene Shidong An

2 Discipline of Chinese Studies, School of Languages and Cultures, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Rebeca Lima, University of Fortaleza, Brazil

The Russian-born American psychologist Bronfenbrenner's bioecological perspective on human development is an ideal framework for understanding how individuals negotiate the dynamic environment and their own identities in international and intercultural education settings. However, a review of the current literature shows that most studies either adopted the earlier version of the theory (i.e., the ecological systems theory) or inadequately presented the most recent developments of the bioecological model (i.e., the process-person-context-time model). The construct of proximal processes—the primary mechanisms producing human development according to Bronfenbrenner—has seldom been explored in depth, which means the true value of bioecological theory is largely underrepresented in international and intercultural education research. This article first presents a review of studies that adopt Bronfenbrenner's theory and then offers future directions for the scope and design of international and intercultural education research.

1 Introduction

Bronfenbrenner's ecological theory on human development 1 is one of the most influential and widely cited theories in the fields of human development and educational psychology (Weisner, 2008 ). Dissatisfied with the lack of child development research directly addressing how development is impacted by wider environments, Bronfenbrenner proposed an ecological model that can provide a framework and common language for conceptualizing the environment and identifying how the interactions and relationships among the components of the ecosystem may affect children's development (Shelton, 2019 ). A popular visual representation of Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems model is a diagram of the ecological system within which a toddler sits at the center, surrounded by a series of concentric circles demonstrating micro-, meso-, exo-, and macrosystems (Darling, 2007 ). An arrow representing the chronosystem (the influence of time) (Bronfenbrenner, 1994 ) 2 is also added in some diagrams (e.g., Porter and Porter, 2020 ). Although Bronfenbrenner initially formulated the framework to delineate these ecological systems, he later refined it into the Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) model (Bronfenbrenner, 1994 , 1999 ; Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 1998 , 2006 ) to comprehensively consider interactions among developmental processes, contextual and individual biological characteristics, and temporal aspects.

This theory, although originated in the field of developmental psychology, is also useful for educational studies since it informs practical applications for the construction of better educational environments. In one of his earlier works, Bronfenbrenner ( 1977 ) introduced an ecological approach to education, emphasizing the dynamic relationships between learners and their environments. He challenged the traditional view of relying solely on laboratory experiments in educational research and advocated for a more holistic and ecologically valid approach to studying educational systems and processes. His focus was on the significance of real-life settings and the dynamic interactions between learners and their environments. Bronfenbrenner emphasized that understanding how individuals learn within educational settings is contingent upon the interplay between the characteristics of learners and the contexts they engage with, highlighting the intricate connections among these environments. His later article (1994), titled Ecological Models of Human Development , published in the International Encyclopedia of Education , demonstrates his considerable influence in educational research. While Bronfenbrenner's theory is most applied in child development and parental education research, it has also found use in various education-related studies, such as educational accountability (Johnson, 2008 ), educational transition (O'Toole et al., 2014 ), computer-assisted language learning (Blin, 2016 ), early childhood education (Tudge et al., 2017 ), and higher education (Mulisa, 2019 ). For instance, Mulisa ( 2019 ) drew inspiration from Bronfenbrenner's theory and advocated for a holistic approach that emphasizes the proximal and active interplay between students and their environments. This approach emphasizes that students' learning should not be disconnected from the social ecology of higher education. Furthermore, educational outcomes should not be attributed solely to students' competence and curriculum quality. Educators and practitioners should employ comprehensive strategies to effectively manage multilevel socioecological factors that impact students' learning.

Specifically for the field of international and intercultural education, the merits of an ecological perspective are elucidated by Elliot and Kobayashi ( 2019 , p. 913):

[A] beautifully complex co-existence of two ecological systems develops once international students move away from their original (home country) ecological system to pursue an education in a new (host country) ecological system. Reciprocally interacting elements from various systems that affect personal, social and learning practices in particular are arguably crucial for these educational sojourners as they can lead to valuable learning opportunities as well as potential conflicts arising from competing influences emanating from the original and the new ecological systems.

Therefore, Bronfenbrenner's theory offers a nuanced and holistic framework that aids educators and policymakers in understanding, respecting, and effectively responding to the environmental complexities inherent in international and intercultural education. It helps educators appreciate the significance of diverse cultural contexts, values, and norms that influence learners, identify the crucial interactions and relationships in the intercultural settings that contribute to a student's adaptation and learning, and encourages students to engage with diverse environments for the development of intercultural competence.

This study aims to review and evaluate the application of Bronfenbrenner's developmental theory, as represented in empirical work on international and intercultural education. As noted in some critical reviews (Darling, 2007 ; Tudge et al., 2009 , 2016 ; Tudge, 2016 ; Jaeger, 2017 ), the ecological theory was evolving as Bronfenbrenner continuously revised, tested and expanded his understanding of development throughout his long career (Shelton, 2019 ), whereas not all studies are aware of its mature version, that is, the bioecological model. Therefore, it is crucial for researchers to recognize the updated version of the theory, which reflects the most recent advance of such a powerful framework. Our objectives are threefold: First, to provide a brief overview of the evolution of the ecological theory and its historical evolution. Second, to evaluate whether the researchers in the fields of international and intercultural education adequately represented the theory in their empirical research. Third, to clarify the value of the updated version of the theory and direct future research.

We will first explain the evolution of Bronfenbrenner's ecological theory and then present some scholars' critics of its misuse in the literature. This is followed by a review and evaluation of the international/intercultural education research that has applied different versions of the theory. It will reveal that the theory is underrepresented in the current international/intercultural education literature. The paper concludes with a discussion of future directions for international and intercultural research.

2 The evolution and different versions of Bronfenbrenner's theory

Several scholars have provided extensive discussion on how Bronfenbrenner's ecological theory of development changed over time, from one that appears to focus primarily on contexts of development to one in which proximal processes are foregrounded (e.g., Rosa and Tudge, 2013 ).

In brief, Bronfenbrenner's early work in the 1970s initially spotlighted environmental contexts in human development due to the prevailing lack of attention to contextual influences within developmental psychology. Therefore, his original ecological perspective “offers a foundation for integrating context into the research model” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979 , p. 21) and provides a theoretical framework that allows for the observation of a wide range of contextual influences on development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979 ). However, Bronfenbrenner was dissatisfied with the fact that the studies applying the model had a pervasive focus solely on contextual elements, resulting in an imbalanced focus on “context without development” (Bronfenbrenner, 1986b , p. 288). This overemphasis on context prompted a pivotal shift in the 1980s toward the integration of person, process, and time variables within the framework (Jaeger, 2017 ). Bronfenbrenner reformulated his model into the bioecological model by the late 1990s. This revised model positioned “proximal processes,” defined as “progressively more complex reciprocal interaction between an active, evolving biopsychological human organism and the persons, objects, and symbols in its immediate external environment” (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 1998 , p. 996), at its core. This evolution culminated in the process-person-context-time (PPCT) model, a refined iteration that accentuated the interplay of proximal processes, individual characteristics, environmental contexts, and temporal dimensions in human development (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 1998 , 2006 ).

While the earlier ecological model predominantly focused on environmental contexts, its emphasis on context may have led to a narrow perspective, overlooking the dynamic interplay between individuals and their immediate environment. This approach often merely compared individuals in various social or geographical contexts without delving into the developing mechanisms behind observed outcomes, assuming that all individuals in a given environment undergo the same developmental trajectory. Such an approach may, as Bronfenbrenner ( 1988 ) notes, “yield results that are not only likely to be redundant but also highly susceptible to misleading interpretations” (p. 27–28). One of the significant theoretical advancements in the bioecological model is the introduction of a critical distinction between environment and process, absent in the original ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1999 ). While the former (environment) encompasses phenomena like mother-infant interaction and the behavior of others toward the developing person, the latter (process) is defined by its functional relationship both to the environment and to the characteristics of the developing person. The bioecological model proposes that the effects of proximal processes are more influential than those of the environmental contexts in which they occur. The evolution toward the bioecological model integrated the multifaceted interrelationships between developmental processes, individuals, contexts, and time, thereby offering a more comprehensive framework to comprehend the complexities of human development.

Bronfenbrenner ( 1995 ) highlighted Drillien ( 1964 )'s research to exemplify the nature and scientific promise of the updated version of the bioecological model. This longitudinal study assessed factors affecting the development of children with low birth weight compared to those with normal birth weight, across different social classes over 2 years. It found that a proximal process, in this case, mother-infant interaction over time, emerges as a significant predictor of developmental outcomes, as positive maternal interaction significantly reduces behavioral issues observed in the child. The study reveals that the power of this process varies systematically based on environmental context (i.e., social class) and individual characteristics (i.e., birth weight). It highlights that the moderating effects of person and context on the proximal process of mother-infant interaction are not symmetrical. In disadvantaged environments, this interaction has the most significant effect, especially benefiting infants with normal birth weight. Conversely, in more privileged social class settings, it is low-birth-weight infants who derive the greatest advantage from maternal attention during this interaction. Therefore, one should not over- or underestimate the power of any of these factors without considering their interaction with each other. Bronfenbrenner ( 1999 ) suggests that one distinct advantage of the bioecological model, compared to other analytic designs used for analyzing environmental influences on development, lies in its recognition of the interdependency and contextual variations among influencing factors. Thus, it can address the limitations of linear multiple regression models commonly used in psychological research, which assume additive effects, and offer a more differentiated understanding of how these factors contribute to developmental outcomes by considering their synergistic effects.

The upcoming sections will outline the key elements in both the earlier and updated versions of Bronfenbrenner's theory. This will serve as a groundwork for our subsequent analysis of existing studies utilizing these distinct versions of the theory. Many studies adopting the early model of concentric circles of environments use the name ecological systems theory (EST) (e.g., Porter and Porter, 2020 ; Trevor-Roper, 2021 ; Tong et al., 2022 ), which is an outmoded version and a facile representation of Bronfenbrenner's theory (Tudge et al., 2009 , 2016 ). Navarro et al. ( 2022 ) suggest that unless there are justified reasons for utilizing the earlier version, researchers should employ the latest version of the theory—the bioecological theory of human development along with the PPCT research model—and any modifications should be explicitly outlined. A summary of the key constructs in EST and the PPCT model is provided below.

2.1 The EST model

According to Bronfenbrenner ( 1986a , 1989 , 1994 ), the ecological environment of development encompasses the four layered systems detailed in his 1979 monograph and the concept of the chronosystem introduced in his later works. Several studies (e.g., Porter and Porter, 2020 ; Trevor-Roper, 2021 ; Tong et al., 2022 ) examining the influence of these ecological systems on development have referred to Bronfenbrenner ( 1989 )'s theory as EST. Although in a subsequent chapter titled “Ecological Systems Theory”, Bronfenbrenner re-evaluated his ideas from the 1979 monograph, shifting focus from context to person and process, studies using a model named after EST predominantly rely on his earlier conceptualization of ecological systems as developmental contexts. To accurately represent Bronfenbrenner's theory in the articles reviewed in this study, we use EST to denote his earlier attempt to define distinct ecological systems, namely the earlier version of his ecological theory. However, we will cite his definitions from the 1994 entry, as this is where the chronosystem was introduced as the fifth system, providing a comprehensive understanding of all five contextual influences on development as envisioned by Bronfenbrenner.

In the EST model, the development of an individual is influenced by four environmental forces, represented by nested circles (micro-, meso-, exo-, and macrosystem) and the flow of time (chronosystem). The innermost circle is the Microsystem , which is “a pattern of activities, social roles, and interpersonal relations experienced by the developing person in a given face-to-face setting with particular physical, social, and symbolic features that invite, permit, or inhibit engagement in sustained, progressively more complex interaction with, and activity in, the immediate environment” (Bronfenbrenner, 1994 , p. 39). Settings such as family, school, peer group and workplace are all regarded as microsystems. The next layer of the circle is the Mesosystem , which “comprises the linkages and processes taking place between two or more settings containing the developing person” (Bronfenbrenner, 1994 , p. 40), representing a system of microsystems. For instance, the linkage between school and family may affect a child's development. Then, there is the Exosystem , consisting of the “linkages and processes taking place between two or more settings, at least one of which does not contain the developing person, but in which events occur that indirectly influence” (Bronfenbrenner, 1994 , p. 40) the person's development. One example is the relationship between a child's home and their parents' workplace. The outermost circle is the Macrosystem , or “the overarching pattern of micro-, meso-, and exosystems characteristic of a given culture or subculture” (Bronfenbrenner, 1994 , p. 40). Finally, the Chronosystem “encompasses change or consistency over time not only in the characteristics of the person but also of the environments in which the person lives” (Bronfenbrenner, 1994 , p. 40).

As Bronfenbrenner's thinking progressed, he called into question the overemphasis on the central role of the environment in human development and gradually made the “marked shift” to a focus on processes and a more prominent role of the developing person, reconceptualizing his theory as a bioecological model (Bronfenbrenner and Ceci, 1994 ). He later labeled his work a PPCT (Process-Person-Context-Time) model of development (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 1998 , p. 996). Each element of this newly evolving framework is outlined below.

2.2 The PPCT model

The PPCT model comprises the four defining properties of the bioecological model, emphasizing a simultaneous investigation of all these elements (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006 ).

Process in the model, specifically encompassing proximal processes , refers to the “progressively more complex reciprocal interaction between an active, evolving biopsychological human organism and the persons, objects, and symbols in its immediate external environment” (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 1998 , p. 996) over time. Notably, the sense in which Bronfenbrenner used the term “process” (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1986a , b ) in his earlier writings was different from the later concept of proximal process (Merçon-Vargas et al., 2020 ). The later formulations of proximal process illustrate the uniqueness of the concept and its importance to the theory. What is emphasized here is the joint function, involving complex interactions rather than simply the additive effects, of both human traits and the environment. It comprises the “primary mechanisms producing human development” (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006 , p. 795). It is crucial to clarify the distinctiveness of this concept to grasp its meaning fully and prevent confusion with related concepts such as interaction. In the context of international and intercultural education, proximal processes may involve student-teacher interactions, peer relationships, and engagement with culturally relevant learning materials. However, to qualify as proximal processes, these interactions must adhere to the criteria outlined in Bronfenbrenner and Morris ( 2006 , p. 798). In simple terms, their measurement should encompass: (a) increasing complexity leading to either competence or dysfunction, (b) duration and frequency, and (c) reciprocal interaction (Navarro et al., 2022 , p. 236).

The Person in PPCT model is in contrast to most developmental studies' treatment of the cognitive and socioemotional characteristics of the person as measures of developmental outcomes. It is featured both as an initial factor influencing proximal processes and as a result shaped by the interplay between person, context, and proximal processes across time. It attempts to identify process-relevant person characteristics, which was labeled person forces/disposition (differences of temperament, motivation, persistence, etc.), resources (relate to mental and emotional resources such as past experiences, skills and intelligence and to social and material resources) and demands (personal stimulus such as age, gender, skin color and physical appearance) (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006 ). These have the “capacity to influence the emergence and operation of proximal processes” (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006 , p. 810). While Context includes the micro-, meso-, exo-, and macrosystems in the earlier EST model, the macrosystem was addressed more implicitly in writings about bioecological theory and the PPCT model (Navarro et al., 2022 ). The emphasis is on introducing a more significant domain within the microsystem structure, highlighting the unique impact of proximal processes involving interaction with objects and symbols, rather than solely with individuals (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006 ). Finally, Time extends the original chronosystem (macro-time) to include another two levels: micro-time (what is occurring during some specific activity or interaction) and meso-time (the extent to which activities and interactions occur with some consistency in the developing person's environment) (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006 ; Tudge et al., 2009 ).

All these elements in the PPCT model work interdependently and synergistically. Synergy is a key concept in the PPCT model, which refers to the cooperative action of these four elements, such that the total effect is greater than the sum of their individual effects (Navarro et al., 2022 ). To operationalize synergy in research, Bronfenbrenner and Morris ( 2006 ) suggest studying interactions between person and context, using multigroup models to analyze differences in developmental trajectories and outcomes across time. Navarro et al. ( 2022 ) demonstrate that the PPCT model has a minimum of four comparison groups by choosing two levels of a person characteristic and two levels of a contextual influence. These groups allow for an analysis to identify significant differences in developmental paths and outcomes among different person/context combinations over time.

Bronfenbrenner's bioecological model is no doubt a complex theory (see a summary of its constructs in Table 1 ). Bronfenbrenner ( 1986a ; 1988 ; 1999 ) acknowledged the complexity and ambition of such a comprehensive paradigm, recognizing that very few researchers can address all its components simultaneously in one comprehensive analysis. It is more feasible for researchers to break down these components into smaller combinations that work together cohesively (Bronfenbrenner, 1999 ). He also emphasizes that the purpose of presenting this ambitious design is not to set rigid criteria for all researchers but to offer promising paradigms that generate different research questions. The goal is to alert researchers to the complexities and potential interpretative ambiguities arising from the omission of crucial elements in their selected research designs. Many scholars agree that it is not necessary to include all the factors of the PPCT model in a single study (e.g., Tudge et al., 2016 ; Jaeger, 2017 ). However, Tudge et al. ( 2009 ) asserted that to employ bioecological theory to guide a study, all four elements of the model should be present, or it should be clearly acknowledged why one or more of the elements are not adequately assessed in a research design, so as to preserve the integrity of the theory.

Four constructs and their components in Bronfenbrenner's PPCT model [based on Bronfenbrenner and Morris ( 1998 ) and Tudge et al. ( 2009 )].

2.3 Critics of the misuse of Bronfenbrenner's theory

Some review articles found that the bioecological model had been misused in many studies. These studies either cited the outmoded version or inadequately explored its components while claiming to employ the PPCT model, disregarding the resulting ambiguity due to the omission of certain constructs. For instance, Tudge et al. ( 2009 ) reviewed 25 papers published between 2001 and 2009 and showed that all but four adopted the outmoded version of the theory, which resulted in conceptual confusion and inadequate testing of the theory. After 5 years, Tudge et al. ( 2016 ) conducted a reevaluation of 20 more recent publications. The study found that although 18 of them cited the mature version (after the mid-1990s) of Bronfenbrenner's theory, only two appropriately described, tested, and evaluated the four constructs of the PPCT model. In another commentary, Tudge ( 2016 ) indicates that there are explicit and implicit ways of using Bronfenbrenner's bioecological theory: the former explicitly links research variables and methods to bioecological theory, while the latter only examines person–context interactions over time without explicitly connecting these observations to the theory's constructs. This emphasizes the necessity for the appropriate application of Bronfenbrenner's updated theory, requiring explicit recognition of its constructs as influential variables for development, as detailed in Table 1 .

These reviews collectively underscore the persistent issue of inadequate adoption and exploration of the updated bioecological model, especially the nuanced constructs within the PPCT framework. The gaps identified in the literature necessitate a more thorough examination and explicit utilization of the updated theory to advance a comprehensive understanding of human development within international and intercultural education settings.

Their reviews included research up to 2016, when the model was not yet often extended to fields other than developmental science. In fact, the publications included in their reviews are mostly in the realms of family studies and child development. Therefore, this paper will review the current literature on international and intercultural education and evaluate how Bronfenbrenner's theory has been adopted in this research field.

3 Status of employing Bronfenbrenner in international and intercultural education: a review of current studies

The papers to be reviewed in this section are empirical studies in the fields of international and intercultural education that claim to adopt Bronfenbrenner's ecological theory. We followed the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021 ) to identify and screen the papers in the databases. The PRISMA flow chart is presented in Figure 1 .

PRISMA flow diagram for searching, identifying, screening, and evaluating studies [adapted from Page et al. ( 2021 )].

The terms used for searching studies using Bronfenbrenner's theory followed Tudge et al. ( 2009 ) and Jaeger ( 2017 ): Bronfenbrenner/bioecological/ecological systems theory/process–person–context–time/PPCT. We also used the keywords international/intercultural/study abroad/exchange/mobility/overseas to constrain the research field to international or intercultural education. We searched the Web of Science (WoS) databases (SSCI/SCI-Expanded/ESCI/A&HCI) (up until 12 September 2023) to ensure that the articles obtained were of good quality. We also conducted searches using a specialized database, EBSCO-ERIC (Educational Resource Information Center), up until September 12, 2023, to identify any additional studies specifically relevant to education. The following inclusion criteria were applied to the initial searches in both databases: (a) studies published in peer-reviewed academic journals, (b) studies published in English, and (c) empirically designed studies, excluding other types such as editorials and review articles. Additionally, we limited the WoS Categories to psychology, education, and related fields like linguistics and social sciences. We also included multidisciplinary categories to retrieve potential studies. Detailed search strategies, including filters and limits used for both databases, are specified in the Appendix . These searches yielded 182 results in the WoS databases and 130 in the ERIC database, totaling 283 after discarding duplicates.

The two researchers screened these records, encompassing titles, abstracts, and keywords, to determine their eligibility for further evaluation. Initially, they conducted independent screenings, resolving disagreements through collaboration. Subsequently, studies were manually eliminated if they: (a) were non-empirical, (b) did not pertain to intercultural or international education (for example, studies merely containing the keyword “international” but not related to international education), and (c) did not apply Bronfenbrenner's theory (for instance, studies related to ecological and environmental education containing the keyword “ecological” but not employing an ecological perspective to investigate educational issues). Studies with uncertainties regarding their article type, research scope, or theoretical perspective were reserved for further examination. Following this screening, 37 reports were initially considered for retrieval, although the authoritative versions of one article could not be retrieved. The researchers then thoroughly examined the full papers of the remaining 36 studies, discarding ten articles based on the aforementioned criteria. Consequently, 26 studies remained for inclusion in this review, as summarized in Table 2 .

Studies on international and intercultural education employing Bronfenbrenner's ecological theory reviewed in this study.

* Most recent Bronfenbrenner work cited by the author(s). ** Although there is a citation of Bronfenbrenner's work in 2009, the original publication dates back to 1979, so the most recent work cited is Bronfenbrenner's publication in 1993.

Some initial observations can be made from Table 2 . First, although we did not set the starting year for our search period, most eligible studies were published in the recent decade, suggesting that Bronfenbrenner's theory has been applied only to the field of international and intercultural education quite recently. Second, 18 studies cited Bronfenbrenner's work before the mid-1990s or named the theory EST or ecological model/theory; thus, they did not use the mature version. Another seven studies cited his work after 2000 and used the term “bioecological” (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 1998 ; Bronfenbrenner, 2005 ), demonstrating the researchers' awareness of the recent update on the framework. The remaining study (Bhowmik et al., 2018 ), although cited Bronfenbrenner and Morris's ( 2006 ) work, did not use the term “bioecological” (instead, they named the theory “a socioecological model”) 3 . Third, most studies relied solely on qualitative methods to collect and analyze data.

The studies can be grouped into several categories according to how Bronfenbrenner's theory is used: loosely connected to Bronfenbrenner's theory, EST-based, and based on the updated version of the bioecological model (see detailed categorization in Table 3 ). Recognizing that the application of Bronfenbrenner's theory is still in its infancy in international and intercultural education research, our objective is not to critique individual articles but to understand the extent to which the empirical studies we reviewed reflect the recent development of the theory.

Categorization of the studies reviewed.

3.1 Studies loosely connected to Bronfenbrenner's theory

Four studies (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2010 ; Bhowmik et al., 2018 ; Elliot and Kobayashi, 2019 ; Trevor-Roper, 2021 ) are only loosely connected to Bronfenbrenner's theory, although they cite his work, either the early or the mature version. These studies only mention Bronfenbrenner in their papers but have not systematically applied his theory. Bhowmik et al. ( 2018 ) cite Bronfenbrenner's work without using the constructs of his theory for data analysis. Elliot and Kobayashi ( 2019 ) only mention the coexistence of two ecosystems of international students but have not specified the components in each layer of the ecosystem. Suárez-Orozco et al. ( 2010 ) reference Bronfenbrenner's early work (Bronfenbrenner, 1977 ) to highlight the significance of contexts and characteristics affecting students' performance. However, while their research explores the influences of school, family, and individual characteristics on immigrant children's academic trajectories, it lacks a systematic foundation based on Bronfenbrenner's theory. Moreover, the study findings are not explicitly interpreted in connection with Bronfenbrenner's framework. Similarly, Trevor-Roper ( 2021 ) only briefly discusses that the EST model is helpful in appreciating the complexity of higher education environments in international education but does not follow the model's constructs to frame the data analysis.

In other words, Bronfenbrenner's theory only serves as an overarching philosophical perspective rather than an operational model that guides detailed data analysis procedures in these studies. Such an approach partially overlaps with Tudge ( 2016 ) description of the “implicit way” of using Bronfenbrenner's theory, which only examines person–environment interactions and the complexity of the environment. This can be problematic since it oversimplifies the richness of Bronfenbrenner's theory and does not sufficiently demonstrate its value for international and intercultural education.

3.2 Studies based on EST

Twenty studies (McBrien, 2011 ; Jessup-Anger and Aragones, 2013 ; Elliot et al., 2016a , b ; Li and Que, 2016 ; Taylor and Ali, 2017 ; Vardanyan et al., 2018 ; Zhang, 2018 ; Emery et al., 2020 ; Merchant et al., 2020 ; Porter and Porter, 2020 ; Conceição et al., 2021 ; Winer et al., 2021 ; Chkaif et al., 2022 ; Ngo et al., 2022a , b ; Tong et al., 2022 ; Xu and Tran, 2022 ; Marangell, 2023 ; Rokita-Jaśkow et al., 2023 ) are based on the early version, that is, the EST model, although some of them cite Bronfenbrenner's later work and use the term “bioecological.” Three sub-categories can be identified: partial adoption, full adoption, and extended adoption of EST.

3.2.1 Partial adoption of EST

Ten of the 20 studies, including Jessup-Anger and Aragones ( 2013 ), Elliot et al. ( 2016b ), Li and Que ( 2016 ), Taylor and Ali ( 2017 ), Vardanyan et al. ( 2018 ), Emery et al. ( 2020 ), Merchant et al. ( 2020 ), Porter and Porter ( 2020 ), Winer et al. ( 2021 ), and Rokita-Jaśkow et al. ( 2023 ) are all classified as partial adoption.

Elliot et al. ( 2016b )'s study on international students' academic acculturation focuses exclusively on the chronosystem in the EST model. They identify different forms of personal transition, societal transition, and academic transition of international students. Conversely, Emery et al. ( 2020 )'s study explores the experiences of internationally adopted youths across various systems (micro-, meso-, exo-, and macrosystems), with a specific focus on the mesosystem, where schools are pivotal in providing support. Their study does not address the chronosystem.

Jessup-Anger and Aragones ( 2013 ) primarily delve into the influence of developmentally instigative characteristics (Bronfenbrenner, 1993 ) on interactions of study abroad students in host countries, discussing micro- and mesosystems. In Merchant et al. ( 2020 )'s work on refugee students, they highlight the mesosystem (interactions between families, peers, and schools) and exosystem (neighborhood and community organizations) as influential in shaping students' wellbeing. Li and Que ( 2016 )'s study focuses on integration challenges faced by newcomer youths in a Canadian city, emphasizing themes related to the exosystem (public transportation), microsystem (family support, social interaction), and individual factors like language barriers and job pressures. Porter and Porter ( 2020 ) analyze factors influencing Japanese college students' decisions to study abroad, considering various ecosystem layers (micro- and mesosystems as immediate environments, and exo-, macro-, and chronosystems as distant environments). They omit the mesosystem due to limited participant input. Conversely, Taylor and Ali ( 2017 ) incorporate the mesosystem while excluding the exosystem in their examination of international students' adjustment to studying in the UK. They do not distinctly explain the rationale for excluding the exosystem, potentially due to data limitations.

Rokita-Jaśkow et al. ( 2023 )'s study on the school socialization of bi/multilingual children examines the microsystem (teachers), mesosystem (classmates and parents), and exosystem (representatives of the education system). However, it omits the macro- and chronosystems within the EST framework without providing an explanation. Vardanyan et al. ( 2018 ) employ Bronfenbrenner's EST concepts in their data analysis, emphasizing the micro- and mesosystems, with limited focus on the chronosystem. In contrast, Winer et al. ( 2021 ) explore immigrants' children's sense of belonging within the microsystem (their rooms in their homes), mesosystem (a shared living building), and macrosystem (their neighborhood). However, they do not introduce or investigate the exo- and chronosystems.

These studies collectively illustrate that the EST is a multifaceted model, demanding multiple investigations to comprehensively explore the entire ecological system (Elliot et al., 2016b ). However, there is a need for more explicit justification when certain constructs within the model are excluded from analysis, as this exclusion affects the overall comprehensiveness of the theory.

3.2.2 Full adoption of EST

Four studies investigate all the components of EST. McBrien ( 2011 ) delves into the challenges encountered by refugee mothers as they adapt to settled lives and explores their children's schooling experiences in the context of all the components within the EST. Ngo et al. ( 2022b ) investigate the impact of contextual factors on the professional development experiences of Vietnamese English as a foreign language lecturers across different contextual levels within the EST model. Tong et al. ( 2022 ) use the EST model to offer a visual metaphorical illustration of the major themes at each level of an Australian–Chinese student's developmental ecosystem in Hong Kong and tease out the risk and protective elements in this ecosystem that influenced the student's developmental trajectory. Zhang ( 2018 ) examines how academic advising with international students was shaped by individual backgrounds and multiple layers of environmental influences.

These studies meticulously examine each construct of EST within the context of international and intercultural education and demonstrate the relevance of the model in fostering positive interactions in intercultural settings.

3.2.3 Extended adoption of EST

Six articles extend the model to some degree. Chkaif et al. ( 2022 ) combine EST with Yu et al. ( 2021 ) to generate a refined model for international education, with the macrosystem being revised to include the global dimension. Conceição et al. ( 2021 ) expand upon the investigation of the chronosystem within the EST by integrating transformative learning theory to illustrate the personal growth and development of study abroad students over time. Elliot et al. ( 2016a ) propose an academic acculturation model illustrating the transition between two ecosystems of a study-abroad sojourn. Marangell ( 2023 )'s study on students' experiences at an internationalized university applies a person-in-context (PiC) model (Volet, 2001 ), which adapts Bronfenbrenner's EST. The PiC model centers on the “experiential interface,' where individual and environmental dimensions interact, and explores how congruence between these dimensions fosters motivated and productive learning. Ngo et al. ( 2022a ) incorporate EST into an integrated framework for effective professional development, encompassing three dimensions: context, content, and process. Finally, Xu and Tran ( 2022 ) extend the investigation of the person at the center of EST by employing the needs–response agency theory.

These studies provide nuanced perspectives that enhance EST's applicability in international and intercultural education and underscore the importance of the continuous evolution of the theory to address the complexities of educational systems in an increasingly interconnected world. However, the expansion of the theory also introduces extra complexity and challenges in operationalizing and measuring the constructs, and care should be taken to disentangle various factors.

The EST-based studies reviewed above offer valuable insights into international and intercultural education within Bronfenbrenner's early EST model by discussing various aspects, such as the impact of cultural contexts, policy frameworks, academic transitions, peers, and advisors, all of which are crucial in understanding educational experiences in diverse cultural settings. Nevertheless, the absence of the PPCT model in these studies limits the exploration of the dynamic processes and interactions between individuals, their contexts, and the outcomes of international and intercultural education.

3.3 Studies based on the updated version of the bioecological model