- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Patient Perspectives

- Methods Corner

- Science for Patients

- Invited Commentaries

- ESC Content Collections

- Knowledge Translation

- Author Guidelines

- Instructions for reviewers

- Submission Site

- Why publish with EJCN?

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Read & Publish

- About European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing

- About ACNAP

- About European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- War in Ukraine

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

The problem: how do i reach consensus, the solution: different delphi techniques for reaching consensus, example of the delphi technique.

- < Previous

Coming to consensus: the Delphi technique

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Marlen Niederberger, Stefan Köberich, members of the DeWiss Network, Coming to consensus: the Delphi technique, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing , Volume 20, Issue 7, October 2021, Pages 692–695, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvab059

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Delphi techniques are used in health care and nursing to systematically bring together explicit and implicit knowledge from experts with a research or practical background, often with the goal of reaching a group consensus. Consensus standards and findings are important for promoting the exchange of information and ideas on an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary basis, and for guaranteeing comparable procedures in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Yet, the development of consensus standards using Delphi techniques is challenging because it is dependent on the willingness of experts to participate and the statistical definition of consensus.

Understanding the potential and challenges of Delphi techniques for reaching consensus.

Being aware of possible reasons for dissenting findings.

Understanding strategies for reaching consensus with a Delphi technique.

Knowing CREDES—a reporting guideline for Delphi studies.

In the health care and nursing sector, consensus standards play a central role. Consensus is important to make sure that, for instance, all healthcare actors use uniform terminology and definitions, apply the same criteria in the diagnostic process, or implement therapies or interventions in a comparable manner. Ideally, consensus should not only be reached amongst experts in the relevant scientific disciplines but also by practitioners, and importantly by those affected, such as patients, caregivers, and relatives. If all three groups can agree on the terms, standards, and recommendations, it can help (i) to avoid misunderstandings, (ii) to support the exchange of information and ideas on an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary basis, (iii) to make it easier to compare, understand and assess different approaches, and (iv) to help to find a common pathway to targeted future developments.

One particular method to reach consensus is the Delphi technique. 1 , 2 In particular, consensus is sought on:

Clinical guidelines 3

Definitions and terminologies 4

White papers 5

Reporting guidelines 6

Appropriate and feasible treatment methods or healthcare-related interventions 7

Recommendations for action for politics and society 8 , 9

Quality indicators for healthcare-related interventions 10

Possible future developments 11

The question is, however, how a Delphi study can be used to reach consensus, and how different scientific disciplines and spheres of experience can be brought together.

Delphi techniques are established methods for reaching consensus among experts and practitioners, and more recently among those affected. 12 Typically, Delphi participants are asked to evaluate issues where knowledge is uncertain and incomplete. 13 , 14 Questionnaires with rating scales and open-ended questions are used in multiple rounds to determine argumentation patterns. From the second Delphi round onwards, alongside the questionnaire, those surveyed also receive statistical feedback on the results of the previous round. In doing so, they are able to reconsider their judgements on this basis and revise the ratings where appropriate. The feedback is usually provided in the form of frequency tables or using descriptive measurement values.

Experience has shown that there are fewer statistical outliers with every additional Delphi round and also less open-ended comments. Accordingly, consensus does not mean that all of the participants reach the same judgement but rather that a maximum level of convergence is sought. This is achieved using two methodological principles:

The multitude of experiences on the panel: The purpose of a Delphi study is to integrate all groups and perspectives relevant to a research topic in the most balanced way possible. 15 This often includes the perspectives of scientists, medical specialists, caregivers, patients, and relatives. 16 , 17 It is also recommended in some cases that the study should aim to achieve the right balance between the gender, age, position, and institutional affiliation of the participants. 18

The mental model: Delphi techniques initiate a process of cognitive reflection amongst participants that is described as the mental model. 19 By carrying out the study in multiple rounds and providing feedback on the intermediate results, the participants have the opportunity to revise their judgements, especially when they were not sure of their judgement in the first place. This may be the case when it comes to target and transformation knowledge, 20 i.e. the participants are asked to draw conclusions for other specialist fields or future developments. 21 Alongside their existing knowledge, the participants can also recall previously overlooked information, take account of the feedback from previous Delphi rounds, or draw on external sources of knowledge as new information from the second Delphi round onwards. Ultimately, this expands the knowledge base and enables a better or more reliable assessment of the issue than when using just one questionnaire. 19

However, there is no uniform definition for consensus. 13 , 22 , 23 Consensus is typically measured statistically using per cent agreement or based on the variation in the answers. For the development of medical guidelines, consensus is considered to have been reached at 75% agreement, and a high level of consensus at 95% agreement. 24 When using measures of dispersion, a precisely defined interquartile range (e.g. IQR < 1 for a five-level rating scale) or the standard deviation (e.g. standard deviation < 1 for a five-level rating scale) are commonly used to define consensus. 22 The open-ended judgements and arguments are evaluated using exploratory, thematic, or content-based analytic methods. 3 They can be sent back to the experts as feedback together with the statistical findings and thus become part of the process for reaching consensus.

It should be noted that consensus can be manipulated. 25 , 26 Methodological studies have demonstrated, for example, that the way in which consensus is defined, the size of the rating scale and the selection of the statistical measure have an influence on the results, especially with regards to the question of how many items the experts still disagree on. 26 In contrast, the number of items on the questionnaire does not appear to be relevant.

Consensus is also not generally reached for all items on a questionnaire. 13 For pragmatic research reasons, Delphi studies are usually concluded after two or three rounds. There are various reasons for dissenting judgements. Alongside differences between the specialist fields, personality traits and methodological aspects of the voting behaviour of the experts can have an influence:

Individual value systems, experience and power structures, personal interpretations of the items, and the perceived quality of the existing healthcare 25 , 27 have an impact on the answers given. It is also not possible to exclude conscious attempts to manipulate the participants, especially in the case of politically sensitive issues. 19

The design of the questions and the precise formulation of the items have been proven to have an influence. This includes the sentence structure, sentence length, or open-ended vs. closed-ended questions. 28

How the feedback is designed is also important. Studies indicate that group effects exist within the participating groups. 29 Patients appear to change their judgements more frequently than experts from healthcare professions. If peer feedback is provided, i.e. statistical findings from the participants’ own group, the judgements tend to converge more than if combined feedback is provided.

Dissenting judgements are usually not considered any further in Delphi studies and are rarely reflected on scientifically, whether from a specialist, epistemological or methodological perspective. 22

The same software used to collect or analyse quantitative or qualitative data can also be used to carry out Delphi studies. For an online survey, the questionnaire can be programmed using something like Soscisurvey or Surveymonkey. Standardized items can be evaluated using R, SPSS, or Excel and open-ended questions can be analysed using qualitative software tools such as ATLAS.ti or MAXQDA. It is important to note when programming online questionnaires that the software being used is generally not explicitly designed for Delphi techniques. Essential elements of the process, such as providing feedback on the results, may thus have to be programmed manually. There are specific programs available for real-time Delphi studies. 30

Table 1 shows an example of a classical Delphi technique in which patients have been integrated. 31 The methodological approach used for selecting the number of rounds, the use of Likert scales, and the definition of consensus, as well as the process for developing the questionnaire, can be considered typical for Delphi techniques. 14 The number of experts is comparatively high at 74 people. As in many other Delphi studies, the stability of the consensus was not verified in this example. 22 This could have been checked using an additional Delphi round.

Example of the Delphi technique: healthcare needs of adolescents

This example Delphi study demonstrates that judgements can differ between the different groups. The reasons for this were not discussed in this study. This could have provided useful insight into the potential offered by Delphi techniques for identifying and reaching consensus.

There are no recognized reporting guidelines for Delphi techniques, although some authors have formulated initial recommendations. 12 , 32 One of these recommendations has been published under the name CREDES (Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies) in the EQUATOR Network. 1 It describes eight key themes for the publication of Delphi studies:

A clearly defined purpose of the study and a discussion of the appropriateness of the use of the Delphi technique.

The methods and analyses employed need to be comprehensible.

Illustrate the stages of the Delphi process in a flow chart.

A declaration of how consensus was achieved throughout the process.

Reporting of results for each round separately.

Discussion of limitations of the Delphi.

An adequate reflection of the outcomes of the Delphi study.

Formulate a dissemination plan.

Delphi techniques have proven to be successful when it comes to developing consensus standards and guidelines in the health care and nursing sector. 13 However, personality traits, the design of the questionnaire, and the feedback and affiliation to a particular group can influence the answers given by individual participants. It is thus important to follow a methodological and reflective approach. The following tips for the completion of Delphi studies are useful for achieving the maximum level of consensus between the judgements:

Research the relevant groups involved in advance and integrate them into the process in the most balanced way possible, taking into account all relevant perspectives. If you are successful, it will reduce the influence that individual groups may have on the manipulation of the results and improve the chances of reaching a consensus that can be applied and implemented later on.

Use the current state of research and employ this knowledge to support the mental model of the participants in the study. Integrate relevant background information on the current state of knowledge into the first Delphi round. Alongside standardized items, integrate open-ended questions into the questionnaire to identify arguments that may not yet have been considered and then feed them back into the process.

Test the questionnaire in advance, especially with respect to the semantics. This is particularly important when integrating various groups with different standards of formal education into the Delphi process.

Define what is considered as consensus in advance, also to counteract any suspicion of conscious manipulation.

Analyse the dissenting judgements after every round to find out whether there are any specialist or semantic reasons behind them. If necessary, modify the items or add new ones. Take the answers given by the participants to open-ended questions into account in this process.

As all human perceptions and actions are shaped by differences in personality, it is sensible to assess the individual personalities of the participants and the reliability of their judgements. 33 This could reveal possible reasons for any dissenting judgements. This can be done by using questions on self-assessment, personal involvement, psychological scales, or established competency models.

Work on the Delphi study in a team that includes experts on the Delphi technique and its methodology. This will ensure that the process complies with the highest standards of expertise and methodological competence.

Delphi techniques are not the only methods used to reach consensus. The nominal group technique and consensus conferences are also used. 34 Based on their prevalence, however, the Delphi technique can be viewed as the standard method used in the health care and nursing sector.

The DeWiss Network ist supported by the German research foundation (Project Number: 429572724).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Jünger S , Payne SA , Brine J , Radbruch L , Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review . Palliat Med 2017 ; 31 : 684 – 706 .

Google Scholar

Humphrey-Murto S , Varpio L , Wood TJ , Gonsalves C , Ufholz LA , Mascioli K , Wang C , Foth T. The Use of the Delphi and other consensus group methods in medical education research: a review . Acad Med 2017 ; 92 : 1491 – 1498 .

Deckert S , Arnold K , Becker M , Geraedts M , Brombach M , Breuing J , Bolster M , Assion C , Birkner N , Buchholz E , Carl E-G , Diel F , Döbler K , Follmann M , Harfst T , Klinkhammer-Schalke M , Kopp I , Lebert B , Lühmann D , Meiling C , Niehues T , Petzold T , Schorr S , Tholen R , Wesselmann S , Voigt K , Willms G , Neugebauer E , Pieper D , Nothacker M , Schmitt J. Methodischer Standard für die Entwicklung von Qualitätsindikatoren im Rahmen von S3-Leitlinien—Ergebnisse einer strukturierten Konsensfindung . Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2021 ; 160 : 21 – 33 .

Bishop DVM , Snowling MJ , Thompson PA , Greenhalgh T ; the CATALISE-2 Consortium. Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: terminology . J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017 ; 58 : 1068 – 1080 .

Centeno C , Sitte T , de Lima L , Alsirafy S , Bruera E , Callaway M , Foley K , Luyirika E , Mosoiu D , Pettus K , Puchalski C , Rajagopal MR , Yong J , Garralda E , Rhee JY , Comoretto N. White paper for global palliative care advocacy: recommendations from a PAL-LIFE expert advisory group of the pontifical academy for life, Vatican City . J Palliat Med 2018 ; 21 : 1389 – 1397 .

Swart E , Bitzer EM , Gothe H , Harling M , Hoffmann F , Horenkamp-Sonntag D , Maier B , March S , Petzold T , Röhrig R , Rommel A , Schink T , Wagner C , Wobbe S , Schmitt J. A Consensus German Reporting Standard for Secondary Data Analyses, Version 2 (STROSA-STandardisierte BerichtsROutine für SekundärdatenAnalysen) . Gesundheitswesen 2016 ; 78 : e145 – e160 .

Harwood R , Allin B , Jones CE , Whittaker E , Ramnarayan P , Ramanan AV , Kaleem M , Tulloh R , Peters MJ , Almond S , Davis PJ , Levin M , Tometzki A , Faust SN , Knight M , Kenny S ; PIMS-TS National Consensus Management Study Group. A national consensus management pathway for paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (PIMS-TS): results of a national Delphi process . Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2021 ; 5 : 133 – 141 .

Syed AM , Camp R , Mischorr-Boch C , Houÿez F , Aro AR. Policy recommendations for rare disease centres of expertise . Eval Program Plan 2015 ; 52 : 78 – 84 .

Buettner D , Nelson T , Veenhoven R. Ways to greater happiness: a Delphi study . J Happiness Stud 2020 ; 21 : 2789 – 2806 .

Boulkedid R , Abdoul H , Loustau M , Sibony O , Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review . PLoS One 2011 ; 6 : e20476 .

Ravensbergen WM , Drewes YM , Hilderink HBM , Verschuuren M , Gussekloo J , Vonk RAA. Combined impact of future trends on healthcare utilisation of older people: a Delphi study . Health Policy 2019 ; 123 : 947 – 954 .

Sinha IP , Smyth RL , Williamson PR. Using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials: recommendations for the future based on a systematic review of existing studies . PLoS Med 2011 ; 8 : e1000393 .

Niederberger M , Spranger J. Delphi technique in health sciences: a map . Front Public Health 2020 ; 8 : 457 .

Linstone HA , Turoff M , eds. The Delphi-Method. Techniques and Applications . 2nd ed. Reading, Mass: New Jersey Institute of Technology ; 2002 .

Google Preview

Duncan E , athain A , Rousseau N , Croot L , Sworn K , Turner KM , Yardley L , Hoddinott P. Guidance for reporting intervention development studies in health research (GUIDED): an evidence-based consensus study . BMJ Open 2020 ; 10 : e033516 .

Turnbull AE , Sahetya SK , Needham DM. Aligning critical care interventions with patient goals: a modified Delphi study . Heart Lung 2016 ; 45 : 517 – 524 .

Ekberg S , Herbert A , Johns K , Tarrant G , Sansone H , Yates P , Danby S , Bradford NK. Finding a way with words: Delphi study to develop a discussion prompt list for paediatric palliative care . Palliat Med 2020 ; 34 : 291 – 299 .

Spickermann A , Zimmerman M , von der Gracht H. Surface and deep-level diversity in panel selection—exploring diversity effects on response behaviour in foresight . Technol Forecast Soc Change 2014 ; 85 : 105 – 120 .

Häder M. Delphi-Befragungen. Ein Arbeitsbuch . 3rd ed. Wiesbaden : Springer VS ; 2014 .

Jahn T. Transdisziplinarität in der Forschungspraxis. In: Bergmann M , Schramm E , eds. Transdisziplinäre Forschung. Integrative Forschungsprozesse Verstehen und Bewerten . Frankfurt/New York : Campus Verlag ; 2008 . p 21 – 37 .

Ecken P , Pibernik R. Hit or miss: what leads experts to take advice for long-therm judgments? Manag Sci 2016 ; 62 : 2002 – 2021 .

Von der Gracht HA. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies . Technol Forecast Soc Change 2012 ; 79 : 1525 – 1536 .

Diamond IR , Grant RC , Feldman BM , Pencharz PB , Ling SC , Moore AM , Wales PW. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies . J Clin Epidemiol 2014 ; 67 : 401 – 409 .

German Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF). Standing Guidelines Commission. AWMF Guidance Manual and Rules for Guideline Development, 2013 . https://www.awmf.org/en/clinical-practice-guidelines/awmf-guidance.html (21 February 2021).

Birko S , Dove ES , Özdemir V. Evaluation of nine consensus indices in Delphi foresight research and their dependency on Delphi survey characteristics: a simulation study and debate on Delphi design and interpretation . PLoS One 2015 ; 10 : e0135162 .

Lange T , Kopkow C , Lützner J , Günther KP , Gravius S , Scharf HP , Stöve J , Wagner R , Schmitt J. Comparison of different rating scales for the use in Delphi studies: different scales lead to different consensus and show different test-retest reliability . BMC Med Res Methodol 2020 ; 20 : 28 .

Campbell SM , Shield T , Rogers A , Gask L. How do stakeholder groups vary in a Delphi technique about primary mental health care and what factors influence their ratings? Qual Saf Health Care 2004 ; 13 : 428 – 434 .

Markmann C , Spickermann A , von der Gracht HA , Brem A. Improving the question formulation in Delphi-like surveys: analysis of the effects of abstract language and amount of information on response behavior . Futures Foresight Sci 2020 ; 3 : e56 .

MacLennan S , Kirkham J , Lam TBL , Williamson PR. A randomized trial comparing three Delphi feedback strategies found no evidence of a difference in a setting with high initial agreement . J Clin Epidemiol 2018 ; 93 : 1 – 8 .

Aengenheyster S , Cuhls K , Gerhold L , Heiskanen-Schüttler M , Huck J , Muszynska M. Real-time Delphi in practice—a comparative analysis of existing software-based tools . Technol Forecast Soc Change 2017 ; 118 : 15 – 27 .

Chen CW , Su WJ , Chiang YT , Shu YM , Moons P. Healthcare needs of adolescents with congenital heart disease transitioning into adulthood: a Delphi survey of patients, parents, and healthcare providers . Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2017 ; 16 : 125 – 135 .

Hasson F , Keeney S , McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique . J Adv Nurs 2000 ; 32 : 1008 – 1015 .

Mauksch S , von der Gracht HA , Gordon TJ. Who is an expert for foresight? A review of identification methods . Technol Forecast Soc Change 2020 ; 154 : 119982 .

McMillan SS , King M , Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques . Int J Clin Pharm 2016 ; 38 : 655 – 662 .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1873-1953

- Print ISSN 1474-5151

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Delphi methodology in healthcare research: How to decide its appropriateness

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Critical Care Medicine, NMC Specialty Hospital, Dubai 00000, United Arab Emirates. [email protected].

- 2 Critical Care Medicine, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur 302001, Rajasthan, India.

- 3 Institute of Critical Care Medicine, Max Super Speciality Hospital, New Delhi 110017, India.

- PMID: 34322364

- PMCID: PMC8299905

- DOI: 10.5662/wjm.v11.i4.116

The Delphi technique is a systematic process of forecasting using the collective opinion of panel members. The structured method of developing consensus among panel members using Delphi methodology has gained acceptance in diverse fields of medicine. The Delphi methods assumed a pivotal role in the last few decades to develop best practice guidance using collective intelligence where research is limited, ethically/logistically difficult or evidence is conflicting. However, the attempts to assess the quality standard of Delphi studies have reported significant variance, and details of the process followed are usually unclear. We recommend systematic quality tools for evaluation of Delphi methodology; identification of problem area of research, selection of panel, anonymity of panelists, controlled feedback, iterative Delphi rounds, consensus criteria, analysis of consensus, closing criteria, and stability of the results. Based on these nine qualitative evaluation points, we assessed the quality of Delphi studies in the medical field related to coronavirus disease 2019. There was inconsistency in reporting vital elements of Delphi methods such as identification of panel members, defining consensus, closing criteria for rounds, and presenting the results. We propose our evaluation points for researchers, medical journal editorial boards, and reviewers to evaluate the quality of the Delphi methods in healthcare research.

Keywords: Consensus; Coronavirus disease 2019; Delphi studies; Delphi technique; Expert panel; Quality tools for methodology; Research methods; SARS-CoV-2.

©The Author(s) 2021. Published by Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

The Delphi Method As a Research Tool: An Example, Design Considerations and Applications

2004, Information & Management

Related papers

The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 2019

After almost 30 years of being used in the information system (IS) discipline, only a few studies have focused on how IS scholars apply the method's guidelines to design Delphi studies. Thus, this paper focuses on the use of the Delphi method in IS research. To do so, articles published between 2004 and 2017 in the Senior IS Scholars' collection of journals of the Association of Information Systems (AIS), describing Delphi studies, were analised. Based on analysis of sixteen (16) retrieved IS studies, we concluded that IS researchers have applied the method's most important phases and the procedural recommendations to promote rigor were considered in the majority of the analised studies. Nonetheless, IS researchers still need to include detailed information about (1) the steps taken to ensure the validity of the achieved results, (2) better describe the process of selecting and recruiting the experts, and (3) experiment with innovative techniques to keep participants involved in the Delphi process.

Electronic journal of business research methods, 2019

Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 2015

Information & Management, 2013

Ranking-type Delphi is a frequently used method in IS research. However, besides several studies investigating a rigorous application of ranking-type Delphi as a research method, a comprehensive and precise step-by-step guide on how to conduct a rigorous ranking-type Delphi study in IS research is currently missing. In addition, a common critic of Delphi studies in general is that it is unclear if there is indeed authentic consensus of the panelists, or if panelists only agree because of other reasons (e.g. acquiescence bias or tiredness to disagreement after several rounds). This also applies to ranking-type Delphi studies. Therefore, this study aims to (1) Provide a rigorous step-by-step guide to conduct ranking-type Delphi studies through synthesizing results of existing research and (2) Offer an analytical extension to the ranking-type Delphi method by introducing Best/Worst Scaling, which originated in Marketing and Consumer Behavior research. A guiding example is introduced to increase comprehensibility of the proposals. Future research needs to validate the step-by-step guide in an empirical setting as well as test the suitability of Best/Worst Scaling within described research contexts.

The Delphi technique provides different opportunities to researchers than survey research. Essential components of the Delphi technique include the communication process, a group of experts, and essential feedback. This paper provides the foundations of the Delphi Technique, discusses its strengths and weaknesses, explains the use and stages followed, discusses panel selection, and explains how consensus among participants is reached.

Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2000

Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1987

Arkhaia Anatolika , 2023

Latin American Antiquity, 2010

International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 2017

JAMS (Journal of Adventist Mission), 2024

I Cátedra Internacional José Saramago, 2024

A collaboration between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Piraeus and the Islands and the Swedish Institute at Athens., 2021

Water Resources Research, 2024

MAKALAH MANAJEMEN RISIKO Kelompok 4, 2023

Physiotherapy Research International, 2023

SSRG international journal of electronics and communication engineering, 2023

Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research), 2022

Acta scientific pharmaceutical sciences, 2024

International Journal of Computing, 2020

Ciencia latina, 2024

Papers in Literature, 2020

Young Scientist USA, 2015

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Using the Delphi Technique to Determine Which Outcomes to Measure in Clinical Trials: Recommendations for the Future Based on a Systematic Review of Existing Studies

Ian p sinha, rosalind l smyth, paula r williamson.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

* E-mail: [email protected]

ICMJE criteria for authorship read and met: IPS RLS PRW. Agree with the manuscript's results and conclusions: IPS RLS PRW. Designed the experiments/the study: IPS RLS PRW. Analyzed the data: IPS PRW. Collected data/did experiments for the study: IPS PRW. Wrote the first draft of the paper: IPS. Contributed to the writing of the paper: IPS RLS PRW. Conceived the initial idea for the review: PRW.

¶ These authors share joint last authorship.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collection date 2011 Jan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are properly credited.

Ian Sinha and colleagues advise that when using the Delphi process to develop core outcome sets for clinical trials, patients and clinicians be involved, researchers and facilitators avoid imposing their views on participants, and attrition of participants be minimized.

Summary Points

Studies that use the Delphi process for gaining consensus around a core outcome set for clinical trials should be of sufficiently high quality in order for their recommendations to be considered valid.

We report a systematic review of 15 studies that used the Delphi technique for this purpose, in which we identified variability in methodology and reporting.

To improve the quality of studies that use the Delphi process for developing core outcome sets, we recommend that patients and clinicians be involved, researchers and facilitators avoid imposing their views on participants, and attrition of participants be minimised.

Methodological decisions should be clearly described in the main publication in order to enable appraisal of the study.

What Are Core Outcome Sets and Why Are They Useful?

Good clinical trial design requires researchers to specify in advance, in the protocol, those outcomes to be measured. If research has not been conducted to identify the most appropriate clinical trial outcomes in a given condition, three problems may impair the usefulness of the research in informing clinical practice. Firstly, researchers can select outcomes that suit their needs, at the expense of outcomes that are of most importance to patients or clinicians [1] – [3] . Secondly, heterogenous selection and measurement of outcomes in clinical trials can impair the ability to synthesise results across studies in systematic reviews [4] . Thirdly, in the absence of a set of outcomes that should be measured and reported in all clinical trials in the same condition, it can be difficult to ascertain, in the final publication, whether authors report all results or only those that they find favourable [5] , [6] .

As a result, the standardisation of outcomes for clinical trials has been proposed as a solution to the problems of inappropriate and non-uniform outcome selection [4] , [7] and reporting bias [5] , [8] . The most notable work relating to outcome standardisation has been conducted by the OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatology) collaboration, which advocates the use of core outcome sets designed using consensus techniques that are then measured and reported in clinical trials in rheumatology [9] . However, such initiatives are uncommon. In some specialties, such as paediatrics, the number of conditions covered is low and the quality of existing studies variable [10] . In addition, there is limited guidance in the literature regarding the development of a core outcome set. This paper aims to contribute to the methodology of determining which outcomes to measure in clinical trials, or systematic reviews of clinical trials.

The Delphi Technique as a Method of Developing Core Outcome Sets

One method for reaching consensus around which outcomes to measure is the Delphi technique, which comprises sequential questionnaires answered anonymously by a panel of participants with relevant expertise. After each questionnaire, the group response is fed back to participants [11] . In terms of the overall validity of the final consensus, this approach has advantages over less structured methods of reaching consensus such as round-table discussions. Participants in a Delphi study do not interact directly with each other, so situations where the group is dominated by the views of certain individuals can be avoided. When participants consider whether to change their opinion or stick to their original answers, after seeing the group response this decision is not affected by the desire to be seen to agree with senior, overly vocal, or domineering individuals. Improvements in global communication have made it feasible to use the Delphi technique to involve geographically distant participants in larger numbers than are traditionally used in studies employing face-to-face discussion, and so it is also increasingly being used to reach consensus around many topics in medicine, such as education, development of clinical guidelines, and prioritisation of research topics.

There is little guidance for researchers who wish to use the Delphi technique, even though aspects of its methodology can be interpreted in a variety of ways. Most published work has provided guidance based on authors' experiences, rather than empirical research or theoretical justification for the methodological decisions made. One systematic review describes a variety of consensus techniques used for designing clinical guidelines [12] . The authors highlighted important methodological decisions that may affect the overall quality of the final consensus, such as the types of participants involved, the questions they are asked, the information they receive to inform their answers, the manner of the interaction between them, and the way in which consensus is agreed. These have also been variously highlighted as important aspects of methodology in other commentaries about the Delphi technique [13] – [15] .

To our knowledge, there is no guidance related to methodological considerations or reporting for studies using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes or domains to measure in clinical research studies. The objective of the systematic review summarised below (and included in full in Text S1 ) was to examine studies that used the Delphi technique for this purpose. Our recommendations from this review are then summarised to help inform the conduct and reporting of future initiatives.

A Systematic Review of Studies That Have Used the Delphi Technique to Identify Which Outcomes to Measure in Clinical Trials

We searched Medline (no date restrictions) in January 2010 to identify studies that used the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials or systematic reviews of clinical trials. From each eligible study, the following methodological aspects were noted: the participants involved, the types of questions asked, whether the study was completely anonymised, whether non-responders in earlier rounds were included or excluded from subsequent rounds, and the definition of consensus used by the authors. We also evaluated the quality with which the methods and results were reported. These assessments enabled us to identify variations in the methods applied within these studies, and areas of reporting quality that could be improved.

Of 656 abstracts, 20 full text articles were retrieved, of which five were excluded because they aimed to identify outcomes for use in clinical practice, and the authors did not state whether the participants considered their use in clinical research studies. Many of the 636 studies excluded on the basis of the abstract described the use of the Delphi process to develop clinical guidelines and educational curricula. Of 15 studies included in the review, eight developed core outcome sets for rheumatological conditions. Others identified outcomes for pain in children, degenerative ataxia, gastro oesophageal reflux disease, infantile spasms, maternity care, multiple sclerosis, and thyroid eye disease.

Studies varied in terms of group composition and the manner in which the Delphi process was conducted. Participation in such studies was dominated by researchers, with patients and families seldom involved.

The reporting quality of studies also varied. Important methodological aspects that were generally less well reported were the information provided to participants at the start of the Delphi process, the information fed back to participants after each round, and the level of anonymity. A summary of the reporting quality of the studies is shown in Table 1 . Each of the items included in the table had been highlighted, by one or more of the commentaries mentioned earlier [13] – [15] , as an important methodological consideration when using the Delphi technique. We tailored the statements so they were relevant for the Delphi process as a method of developing consensus around a core outcome set.

Table 1. Reporting quality of the 15 included studies.

Reaching a final consensus was not the aim of the Delphi process, so a definition of consensus was not given.

All participants responded to each round, so no discussion was made regarding non-responders.

Although an assessment of response rate to each round could be made in 14/15 studies, it was only possible to accurately assess attrition rates in 11/15 studies, which reported the proportion of first round respondents who also completed the final round. Of these, only six studies reported the proportion of participants who completed every round in the Delphi process, from start to finish. Only seven reports presented a measure and distribution of the group opinion for each outcome listed in the final round. No study reported the results, in each round, for every outcome that was considered by the group.

Guidance about Using the Delphi Technique to Determine Core Outcome Sets

Involve clinicians and patients.

Informed clinical decisions can only be based on the results of trials that have measured outcomes of importance to both clinicians and patients. Initiatives to identify which outcomes to measure in clinical trials, however, focus on the opinions of researchers. This means that outcomes included in existing core sets may be selected to serve the needs of researchers in academia or industry, rather than considering how important they are to patients.

Patients have a variety of perspectives about living with a condition, which may differ from those of clinicians and researchers. In one study, involvement of patients in the design of a systematic review highlighted certain outcomes as being of particular importance, but these had not been measured in any of the included trials [16] . Research conducted within the OMERACT group also suggests that clinicians and researchers may not realise that certain outcomes are very important for patients [17] . The perspective of patients is now routinely incorporated into the work conducted by OMERACT [18] . Another important initiative, which actively promotes the involvement of patients and families in identifying priorities in clinical research, is the James Lind Alliance ( http://www.lindalliance.org/ ). In a recent systematic review, this group found a few examples of conditions in which patients and clinicians have worked, together, to identify important research questions [19] , and we feel that similar collaboration is necessary to develop core outcome sets. Determining which outcomes are important may be useful to groups who aim to identify important research questions.

The opinions of different groups can be analysed either together or separately. The use of multiple panels, each comprising a different group [17] , acknowledges that there may be differences in opinion. If different groups with potentially conflicting views are included in a single panel, they may not be equally represented in the final consensus. This can happen either because the panel includes more participants from a certain group, so the final consensus is numerically dominated by their responses [20] , or because participants tailor their answers to agree with a group they perceive to be more authoritative.

In studies that use a single panel, comprising a mixture of participants, authors should report a measure of the distribution of scores for each outcome considered in the final round. This is because cut-off scores, used in most studies, do not describe how strongly the minority feel, and so an apparent consensus could actually be masking major disagreement within the group [13] .

Begin by Asking Open Questions

So that researchers do not impose their views on participants and thus introduce bias into the study, participants are traditionally asked open questions in the first round of a Delphi process. In the context of identifying which outcomes to measure in clinical research studies, this means that participants should suggest potential outcomes that they feel should be considered in the Delphi process, without being prompted or guided by facilitators, steering committees, or reviews of the literature. Most studies we identified did not take this approach. It is not clear whether providing a list to participants for initial consideration may overstate the importance of outcomes that are favourable to the researchers, rather than those which may be of more importance to clinicians and patients. Outcomes measured in previous clinical trials do not always reflect those deemed most appropriate by all stakeholders [1] , [2] , [21] .

Try to Minimise Attrition

People with minority opinions may be more likely to drop out of studies that use the Delphi process, so attrition as rounds progress can lead to overestimation of the degree of consensus in the final results. Strategies to prevent attrition bias are to only invite people who respond to a pre-Delphi invitation to participate in the first round [22] or to list, in the publication, only those participants who either completed the entire Delphi process, or agreed the final consensus statement [23] . An example of a paragraph that could be used to explain to participants the importance of completing the whole Delphi process is shown in Box 1 .

Box 1. Example Text to Emphasize to Participants the Importance of Completing the Whole Delphi Process

Thank you for agreeing to participate in our study. It is very important that you complete the questionnaires in each round. The reliability of the results could be compromised if people drop out of the study before it is completed, because they feel that the rest of the group does not share their opinions. If people drop out because they feel their opinions are in the minority, the final results will overestimate how much the sample of participants agreed on this topic.

Report Certain Aspects of the Methodology and Results

In order to enable appraisal of the quality of studies that use the Delphi process to identify outcomes that should be measured in clinical research, which may in turn affect whether the recommendations are implemented, authors should describe certain important methodological features in the study report. Criticisms of the Delphi technique are that “expertise” of the panel is arbitrarily defined, and that the validity of the final consensus is questionable because individual participants are not accountable for their responses, and they may be led towards conformity with the group, rather than consensus of true opinions [24] . As described earlier, attrition of participants may mean the degree of consensus reached in the final round is overestimated [25] . A recommended checklist of study characteristics and results that should be reported in all studies that use the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical research studies is shown in Table 2 . Given the variation across previous studies, it would be helpful if authors explained their methodological choices, and discussed the effects these may have on the results.

Table 2. Recommended checklist that should be reported in studies using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials or systematic reviews.

Determining how to measure the outcomes included in the core set.

Following the determination of which outcomes to include in a core set, guidance is then required as to how to measure them. One established method for doing so is the OMERACT approach. Once core outcomes are agreed upon, potential instruments to measure them are identified. The psychometric properties of these instruments are then reviewed in terms of feasibility, validity, and responsiveness before the preferred instruments are agreed [9] . A more detailed review of the possible approaches to this question of how to measure the chosen outcomes is beyond the scope of this paper.

Future Areas of Methodological Research

Given variations in methodology between studies, we feel there is a need for research to determine how best to develop core outcome sets. An agenda for this research could be designed through the COMET Initiative (Core Outcome Measures for Effectiveness Trials), which is an international network of individuals and organisations with interest or experience in the development, application, and promotion of core outcome sets ( http://www.liv.ac.uk/nwhtmr/comet/comet.htm ). One such area of ongoing research and discussion relates to whether core outcome sets designed for clinical practice, such as those developed in the five studies we excluded, should be the same as those designed for research. Another priority is research to identify the most effective ways to incorporate the views of different groups of participants, especially patients, in the design of core outcome sets.

Supporting Information

Full report (and PRISMA checklist) of the systematic review of studies that used the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials.

(0.87 MB DOC)

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the National Institute for Health Research, through the MCRN.

RLS is a member of the PLoS Board of Directors.

IPS was funded by the NIHR Medicines for Children Research Network Clinical Trials Unit and Co-ordinating Centre. The Medicines for Children Research Network is part of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and is funded by the Department of Health. IPS was funded by Department of Health grant RNC/013/011. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

- 1. Sinha IP, Williamson PR, Smyth RL. Outcomes in clinical trials of inhaled corticosteroids for children with asthma are narrowly focussed on short term disease activity. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006276 . [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Gandhi GY, Murad MH, Fujiyoshi A, Mullan RJ, Flynn DN, et al. Patient-important outcomes in registered diabetes trials. JAMA. 2008;299:2543–2549. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.21.2543. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Guyatt GH, Meade MO. Outcome measures: methodologic principles. Sepsis. 1997;1:21–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Clarke M. Standardising outcomes in paediatric clinical trials. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050102 . [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Williamson PR, Gamble C, Altman DG, Hutton JL. Outcome selection bias in meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 2005;14:515–524. doi: 10.1191/0962280205sm415oa. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, Bloom J, Chan AW, et al. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003081 . [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Clarke M. Standardising outcomes for clinical trials and systematic reviews. Trials. 2007;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-39. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Kirkham JJ, Dwan KM, Altman DG, Gamble C, Dodd S, et al. The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ. 2010;340:c365. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c365. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Tugwell P, Boers M, Brooks P, Simon L, Strand V, et al. OMERACT: an international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials. 2007;8:38. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-38. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Sinha I, Jones L, Smyth RL, Williamson PR. A systematic review of studies that aim to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials in children. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e96. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050096 . [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management Science. 1963;9:458–467. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CF, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2:i–iv, 1–88. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Goodman CM. The Delphi technique: a critique. J Adv Nurs. 1987;12:729–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1987.tb01376.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–1015. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Hsu CC, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation. 2007;12:1–8. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Serrano-Aguilar P, Trujillo-Martín MM, Ramos-Goñi JM, Mahtani-Chugani V, Perestelo-Pérez L, et al. Patient involvement in health research: a contribution to a systematic review on the effectiveness of treatments for degenerative ataxias. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:920–925. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.005. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Mease PJ, Arnold LM, Crofford LJ, Williams DA, Russell IJ, et al. Identifying the clinical domains of fibromyalgia: contributions from clinician and patient Delphi exercises. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:952–960. doi: 10.1002/art.23826. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Kirwan JR, Newman S, Tugwell PS, Wells GA. Patient perspective on outcomes in rheumatology—A position paper for OMERACT 9. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2067–2070. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090359. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Stewart R, Caird J, Oliver K, Oliver S. Patients' and clinicians' research priorities. Health Expect. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00648.x. In press. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M, Horey D, OBoyle C. Evaluating maternity care: A core set of outcome measures. Birth. 2007;34:164–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00145.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Duncan PW, Jorgensen HS, Wade DT. Outcome measures in acute stroke trials: a systematic review and some recommendations to improve practice. Stroke. 2000;31:1429–1438. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.6.1429. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Ruperto N, Ravelli A, Murray KJ, Lovell DJ, Andersson-Gare B, et al. Preliminary core sets of measures for disease activity and damage assessment in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus and juvenile dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:1452–1459. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg403. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Lux AL, Osborne JP. A proposal for case definitions and outcome measures in studies of infantile spasms and West syndrome: Consensus statement of the west Delphi group. Epilepsia. 2004;45:1416–1428. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.02404.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Sackman H. Delphi critique. Lexington (Massachusetts): DC Health; 1975. [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Bardecki MJ. Participants' response to the Delphi method: an attitudinal perspective. Technological Forecasting and social change. 1984;25:281–292. [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (87.1 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 18 August 2021

Applying real-time Delphi methods: development of a pain management survey in emergency nursing

- Wayne Varndell 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Margaret Fry 4 , 5 &

- Doug Elliott 4

BMC Nursing volume 20 , Article number: 149 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

9092 Accesses

21 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

The modified Delphi technique is widely used to develop consensus on group opinion within health services research. However, digital platforms are offering researchers the capacity to undertake a real-time Delphi, which provides novel opportunities to enhance the process. The aim of this case study is to discuss and reflect on the use of a real-time Delphi method for researchers in emergency nursing and cognate areas of practice. A real-time Delphi method was used to develop a national survey examining knowledge, perceptions and factors influencing pain assessment and management practices among Australian emergency nurses. While designing and completing this real-time Delphi study, a number of areas, emerged that demanded careful consideration and provide guidance to future researchers.

Peer Review reports

The Delphi technique is an established and effective research method with multifaceted applications for health services research. The Delphi technique is uniquely designed to explore health issues and topics where minimal information or agreement currently exists, a relatively common situation within nursing practice. Secondly, the Delphi technique allows for the introduction and integration of viewpoints, opinions, and insights from a wide array of expert stakeholders. With increasing accessibility to the Internet and proliferation of smart device technology, changes from paper-based surveys to the development of online software systems, such as the real-time Delphi method, has significantly extended the potential research for the research population and sample, and efficiency of data collection and analysis. However, a recent systematic review highlighted a gap between available methodological guidance and publishing primary research in conducting real-time Delphi studies [ 1 , 2 ].

In this paper, we seek to examine the methodological gap in applying real-time Delphi methods, by providing a specific case example from a real-time Delphi study conducted to develop a self-reporting survey tool to explore pain management practices of Australian emergency nursing in critically ill adult patients [ 3 ]. Insight into the procedural challenges and enablers encountered in conducting a real-time Delphi study are provided. Importantly, key characteristics of the method are presented, followed by the case-based exemplars to illustrate important methodological considerations. Reflections from the case are then presented, along with recommendations for future researchers considering the use of a real-time Delphi technique approach.

Overview of the Delphi Technique

The Delphi technique was developed in the late 1950s’ by the Research and Development (RAND) Corporation [ 4 ] as a method for enabling a group of individuals to collectively address a complex problem, through a structured group communication process without bringing participants together physically [ 5 ]. Delphi has value in the healthcare sector, as it is characterised by multi-disciplinary teams and hierarchical structures [ 6 ]. The Delphi technique has since become popular with nursing researchers exploring a wide range of topics including role delineation [ 7 , 8 , 9 ], priorities for nursing research [ 10 , 11 , 12 ], standards of practice [ 13 , 14 ] and instrument development [ 15 , 16 ].

The four main characteristics of the classic Delphi method are anonymity, iteration, controlled feedback and statistical aggregation of group responses [ 17 ]. Data collection within the classic Delphi typically includes at least two [ 18 ] or three [ 19 ] rounds of questionnaires facilitated by a moderator. Round one represents what Ziglio [ 20 ] termed the ‘exploration phase’, in which the topic is fully explored using broad open-ended questions. Each following round then becomes part of an ‘evaluation phase’, where results of the previous round, interspersed with controlled feedback from a moderator, are used to frame another set of questions. Each round provides an opportunity for expert panel members to respond to and revise their answer in view of the previous responses from other panel members [ 21 ]. Since its introduction, over 20 variations of the classic Delphi method have evolved, with researchers modifying the approach to suit their needs. Most common Delphi versions include modified, decision, policy, internet, and more recently real-time Delphi, and have empaneled varying numbers of experts ranging from 6 to 1,142 [ 22 , 23 ] (Table 1 ).

The ubiquitous and interactive capacity of the Internet and smart device technology offers benefits that are intimately linked with contemporary research innovations in healthcare [ 24 ]. Two clear limitations of the classic Delphi technique were prolonged study durations and high panel member attrition [ 25 ]. Aiming to overcome these issues, Gordon and Pease [ 26 ] developed the concept of an information technology-enabled contemporaneous extension called real-time Delphi, to improve speed of the data collection process and syntheses of opinions. Conducting a real-time Delphi relies on specially designed software to administer the survey; the functionality or capabilities of which can negatively impact on the success of a study. Initial thoughts of using technology to facilitate the Delphi process emerged as early as 1975 [ 27 ]. The first specifically designed real-time Delphi software was developed in 1998 called Professional Delphi Scan [ 28 ], with the first real-time Delphi surveys performed and published in the early 2000 s [ 29 ]. Since then, several real-time software-based tools have been developed, often by researchers for the purposes of their study [ 30 , 31 , 32 ]. However, these have not been evaluated in detail in the literature.

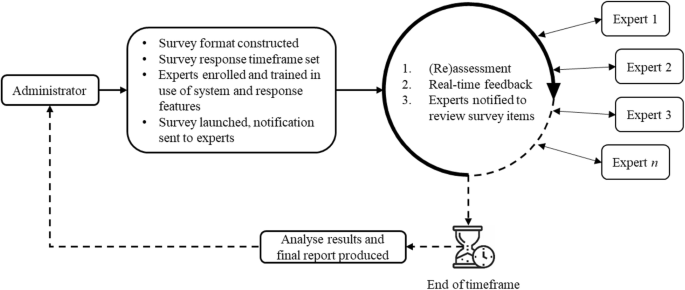

In a real-time Delphi process, participants are provided with access to an online questionnaire portal for a specific amount of time. On accessing the portal, expert panel members see all their responses to items and the ongoing, hence real-time, anonymised responses from other panel members. The core innovation of real-time Delphi studies is the simultaneous calculation and feedback. Unlike the classic method, in a real-time Delphi participants do not judge at discrete intervals (i.e. rounds), but can change their opinion as often as they like within the set timeframe [ 33 ] (Fig. 1 ).

Real-time Delphi processes

A real-time Delphi case exemplar

A real-time Delphi study was conducted to develop a context specific instrument (i.e. survey) to investigate emergency nurses’ practices in managing acute pain in critically ill adult patients. The following steps were followed in designing and conducting our real-time Delphi study: study design, pilot testing, recruiting experts, retention, data analysis and reporting. Findings from this study are reported elsewhere [ 34 ]. The real-time Delphi method was selected to: maximise participation from expert panel members geographically separated, minimise the amount of time demanded of experts, enable equal flow of information to and from all members, real-time presentation of results to enable experts to reassess and adjust their opinion, and allow panel members a greater degree of expression [ 35 , 36 ]. Prior to commencing the study, a comprehensive literature review was conducted by the research team to generate initial survey items, and used the following questions:

What indicators would signify that acute pain in the critically ill adult patient has or has not been adequately detected?

What indicators would imply that acute pain in the critically ill adult patient has or has not been adequately managed?

What indicators would suggest that acute pain in the critically ill adult patient has or has not been communicated adequately?

A total of 74 items were initially generated from the literature, and organised into six domains: clinical environment, clinical governance, practice, knowledge, beliefs and values, and perception. Next, commercially available real-time Delphi survey systems were evaluated for their suitability. This process was guided by reviewing the literature [ 33 ], trialing available platforms and examining fee structures. Following this review, Surveylet (Calibrum Inc., Utah) was selected [ 37 ]. Survey items were then uploaded into Surveylet software system. Pilot testing was then conducted by the research team to evaluate software settings, automation, flow and ease of navigation. Average time to complete the survey was 38 min (SD 8 min).

An expert panel size of 12 to 15 was selected. Identification and selection of experts occurred in three stages: defining the relevant expertise, identifying individuals with desired knowledge and experience, and retaining panel members. First, a pro forma listing the type of skills, experience, qualifications, relevant professional memberships and academic outputs (e.g. peer-reviewed publications) as traits of a desired expert panel member. Second, the research team added potential experts to the list: names of academics were identified via a review of the pertinent literature, with emergency nursing clinicians identified from contacting the College of Emergency Nursing Australasia. Third, initial contacts were approached and provided with a brief overview of the study; pertinent biographical information was then obtained. In addition, they were invited to nominate other experts to be approached for inclusion. Contacts were then independently ranked, with the top 15 experts invited to participate. Twelve accepted the invitation to participate: eight emergency nurses, most nurse consultants (n = 6), two pain management nurse consultants, and two emergency nursing academics from across Australia with an average of 18 years clinical experience. All experts held postgraduate qualifications and half had published in emergency nursing practice and/or pain management.

In Delphi studies, an a priori level of consensus and stability sought for the items the experts will rate is set by the research team. In this study, consensus was achieved if ≥ 83 % (10 out of 12 panel members) of experts ranked the item ≥ 7 on the 9-point Likert scale. Secondary measures of consensus among experts included stability of response, evaluated using coefficient of quartile variation (< 5 %) and interclass correlations (≥ 0.75) [ 38 , 39 ]. Items were retained if primary and secondary measures were met. Data were analysed using median, range and interquartile range. Descriptive statistics were then developed in tabular form and scatterplots.

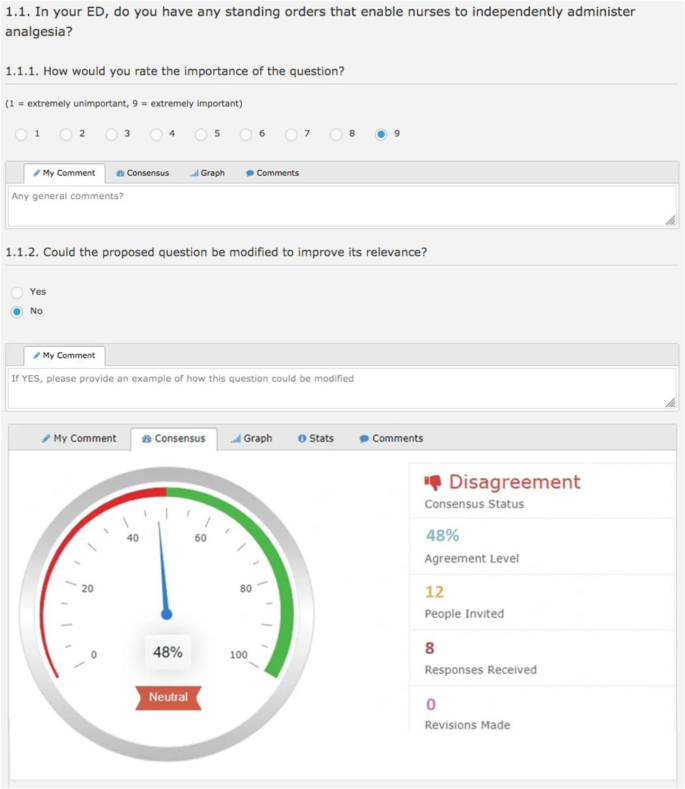

The Delphi panel members were introduced to each survey domain as they navigated through the real-time Delphi software system, including descriptions of the domain and response format to rate each item. For ease of navigation, one item was presented per page, which included a real-time statistical summary and anonymised remarks from other experts (Fig. 2 ) [ 37 ].

Example of review screen

Experts were asked to rate the importance of each question using a 9-point Likert scale (1, extremely unimportant to 9, extremely important), and whether the question could be modified to improve its relevance (Yes/No). If modifications were suggested, respondents were able to provide an example of how the proposed question could be revised, which could then be subsequently voted on by the expert panel.

Participation was asynchronous with experts able to independently re-visit the real-time Delphi survey portal and modify their responses at any point in time between 1st February and March 14th 2019 (a total of 35 days). On accessing the survey portal, panel members can engage in the consensus process from the outset by viewing other panel members’ have responded. Panel members could view not only their own quantitative responses but also the median, range and interquartile range of all given quantitative responses. In the same way, panel members could also view all qualitative arguments submitted by panel members including their own. Panel members could then review or change any or all their responses, or add new arguments, up until the survey closed. Prior to launching the Delphi study, the research team piloted accessing the survey portal, data collection and analysis methods.

All panel members participated in the survey, providing on average four responses per survey item. Further, of the 74 items initially proposed, 58 (78.4 %) reached consensus in the first week of the study commencing. Following feedback from the expert panel, of the initial 74 items proposed, 12 (16.2 %) were modified to improve clarity, and a further 17 items were added by the expert panel to improve survey depth. At the conclusion of the real-time Delphi, the final survey contained 91 items.

While completing the real-time Delphi, several areas were identified as needing consideration when using this technique: software selection, rating scale, piloting, recruiting experts, consensus and stability, retention and reporting. Key issues are discussed in the following section.

Software and survey design

This case study has highlighted that to conduct a real-time Delphi requires specialised software. A recent review [ 33 ] independently evaluated the characteristics of four commercially available real-time Delphi software solutions (Risk Assessment and Horizon Scanning, eDelfoi, Global Futures Intelligence System and Surveylet) for their range of features and available question formats; data analytics; user friendliness; and, intuitive system operation (Table 2 ). Surveylet (Calibrum Inc., Utah) [ 37 ] was rated the highest for its flexibility, breadth of inbuilt data management options, anonymity of participants and security. While the Surveylet system can amply conduct a real-time Delphi, the system is sophisticated and requires additional time and guidance to configure correctly. Training is provided by way of video tutorials, and support options are available to assist in survey setup at an additional cost. We recommend that prior to conducting a real-time Delphi, researchers comprehensively review, and where possible, trial available software solutions.

Advantages of conducting an online Delphi study include: reduced data entry errors due to automated entry, fewer instances of panelists missing questions resulting in incomplete data, length of time decreases for data collection, and automated aggregation of results and feedback to panelists [ 40 ]. The principle difference between a conventional online Delphi and real-time Delphi software systems is the immediate calculation and provision of group responses, which can assist in generating time-sensitive guidance. While there are advantages (Table 3 ), there are also challenges, which are principally associated with software complexity [ 35 ] and cost [ 41 ].

Internet accessibility, system navigation difficulties and the inconvenience of entering data into a computer-based data screen are recognised as challenges [ 44 ]. While the internet is a tool for extending the potential research population and sample, navigating an unfamiliar virtual landscape may frustrate panel members and therefore limit the number of completed surveys [ 45 ]. To minimise potential software complexity issues in our study, panel members were sent detailed written instructions on how to access and navigate the real-time Delphi software system, and could attend a one-to-one videoconference with a member of the research team to assist in using the platform [ 17 , 46 ]. Cost-efficiency is often stated as a key benefit of using online survey tools to conduct an electronic survey [ 41 ]. However, in our review of commercially available real-time Delphi software systems, we found that it can become expensive with system providers potentially charging per survey, the number of system administrators or participants enrolled, the duration of the survey, and/or system support to aid survey customisation. While further evidence is needed to substantiate the claim concerning the efficiency of the real-time Delphi method compared to multi-round Delphi designs, current multi-round Delphi studies investigating topics relating to emergency nursing practice, have taken 60 [ 43 ] to 273 [ 13 ] days to complete.

Rating scale

Currently, there is no agreement about what rating scale size should be used in Delphi studies; despite being a common reason cited for study failure [ 47 , 48 , 49 ]. Rating scales used in previous Delphi studies exploring aspects of emergency nursing practice have ranged from 4 to 11 [ 1 ]. While 5 and 7-point scales are the most common forms of Likert scales used in surveys [ 50 , 51 ], 9-point Likert scales are frequently used in Delphi studies, particularly during the consensus process [ 47 , 49 , 52 ]. A wide range of Likert rating scale sizes can be set within Surveylet. In addition, to underline their rating, experts can also detail their reasoning behind their selection, which can be viewed by other panel members. According to Best [ 53 ], accuracy can be improved if experts are provided with both quantitative and qualitative arguments. In a real-time Delphi experts are able to immediately react on each other’s responses, increasing the degree of information experts can interact with, which may aid in recapturing their own point of view [ 26 ].

Despite the administrative complexity of conducting any Delphi method, there is limited discussion on pilot testing in the literature. Pilot testing can be conducted to test and adjust the Delphi survey to improve comprehension [ 54 ]. When using online software, such as when conducting a real-time Delphi, to conduct and collect multiple responses, the potential impact on cost, time, participant motivation and data integrity should an error occur, could jeopardise the overall study. Pilot testing is therefore vital to identify potential technical or system configuration errors, data collection irregularities (i.e. logic settings) and strengthen participant orientation, prior to commencing the study [ 55 ]. Prior to initiating the real-time Delphi, we first verified system configuration and all settings (e.g. timeframe, communication templates), panel member contact details, and that survey items were uploaded correctly. Second, members of the research team independently piloted the survey as mock participants and system administrators, to evaluate the survey flow and ease of navigation. Average time to complete the survey was 38 min (SD 8 min).

Recruiting experts

The formulation of an expert panel and its makeup is of critical importance for all Delphi studies, yet raises methodological concerns that can negatively impact on the quality of the results [ 36 , 56 , 57 ]. Despite criticism in the literature about Delphi as a methodological approach [ 2 , 17 , 35 , 36 , 40 , 58 ], there remains little agreement as to what defines an expert [ 36 ]. Keeney et al. [ 59 ] in their review identified several definitions of ‘expert’ ranging from someone who has knowledge about a specific topic, recognised as a specialist in the field, to an informed individual. A recent systematic review of the Delphi method in emergency nursing [ 1 ] found similar emphasis in the criteria commonly used to identify experts: length of clinical experience, professional role (e.g. educator, clinical nurse consultant), professional college membership, peer-reviewed publications and postgraduate qualifications. From the current literature, it suggests that defining who is an expert may not be about the role they occupy, but what attributes they possess: knowledge and experience [ 36 , 59 , 60 , 61 ].

Recruiting experts in our study required: defining the relevant expertise, identifying individuals with desired knowledge and experience, and retaining panel members. Melynk et al. [ 62 ] suggests that a minimum threshold for participation as an expert on a Delphi panel should include those measurable characteristics that each participant group would acknowledge as those defining expertise, appropriate to the context, scope and aims of the particular study. While selection of panel experts in Delphi studies typically involves non-probability sampling techniques, which potentially reduces representativeness [ 17 , 57 ], the aim of our study was to recruit academic and emergency nurses with knowledge and clinical experience in the phenomena being explored – pain management practices for adult critically ill patients [ 55 ]. To achieve this, the procedure detailed by Delbecq et al. [ 63 ] was followed.

Expert panel size

Presently there is no agreement in the literature concerning expert panel size [ 2 ]. A recent review of 22 Delphi studies within emergency nursing reported a wide range of panel sizes - from fewer than 12 up to 315. Duffield [ 64 ] suggests that when a Delphi panel is homogenous 10 to 15 people are adequate. In a similar Delphi study seeking to develop a self-completed survey to examine triage practice, 12 experts were recruited [ 16 ]. As noted earlier, the target panel size in our study was 12 to 15, however, as Hartman and Baldwin [ 65 ] highlight, due the higher degree of automation of real-time Delphi software systems, typically web-based, the number of experts over a large geographic area participating in a real-time study can be increased.