Case Report vs Cross-Sectional Study: A Simple Explanation

A case report is the description of the clinical story of a single patient. A cross-sectional study involves a group of participants on which data is collected at a single point in time to investigate the relationship between a certain exposure and an outcome.

Here’s a table that summarizes the relationship between a case report and a cross-sectional study:

Further reading

- Case Report: A Beginner’s Guide with Examples

- Case Report vs Case-Control Study

- Cohort vs Cross-Sectional Study

- How to Identify Different Types of Cohort Studies?

- Matched Pairs Design

- Randomized Block Design

- Chapter 8. Case-control and cross sectional studies

Case-control studies

Selection of cases, selection of controls, ascertainment of exposure, cross sectional studies.

- Chapter 1. What is epidemiology?

- Chapter 2. Quantifying disease in populations

- Chapter 3. Comparing disease rates

- Chapter 4. Measurement error and bias

- Chapter 5. Planning and conducting a survey

- Chapter 6. Ecological studies

- Chapter 7. Longitudinal studies

- Chapter 9. Experimental studies

- Chapter 10. Screening

- Chapter 11. Outbreaks of disease

- Chapter 12. Reading epidemiological reports

- Chapter 13. Further reading

Follow us on

Content links.

- Collections

- Health in South Asia

- Women’s, children’s & adolescents’ health

- News and views

- BMJ Opinion

- Rapid responses

- Editorial staff

- BMJ in the USA

- BMJ in South Asia

- Submit your paper

- BMA members

- Subscribers

- Advertisers and sponsors

Explore BMJ

- Our company

- BMJ Careers

- BMJ Learning

- BMJ Masterclasses

- BMJ Journals

- BMJ Student

- Academic edition of The BMJ

- BMJ Best Practice

- The BMJ Awards

- Email alerts

- Activate subscription

Information

Cross-Sectional Study: Definition, Designs & Examples

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A cross-sectional study design is a type of observational study, or descriptive research, that involves analyzing information about a population at a specific point in time.

This design measures the prevalence of an outcome of interest in a defined population. It provides a snapshot of the characteristics of the population at a single point in time.

It can be used to assess the prevalence of outcomes and exposures, determine relationships among variables, and generate hypotheses about causal connections between factors to be explored in experimental designs.

Typically, these studies are used to measure the prevalence of health outcomes and describe the characteristics of a population.

In this study, researchers examine a group of participants and depict what already exists in the population without manipulating any variables or interfering with the environment.

Cross-sectional studies aim to describe a variable , not measure it. They can be beneficial for describing a population or “taking a snapshot” of a group of individuals at a single moment in time.

In epidemiology and public health research, cross-sectional studies are used to assess exposure (cause) and disease (effect) and compare the rates of diseases and symptoms of an exposed group with an unexposed group.

Cross-sectional studies are also unique because researchers are able to look at numerous characteristics at once.

For example, a cross-sectional study could be used to investigate whether exposure to certain factors, such as overeating, might correlate to particular outcomes, such as obesity.

While this study cannot prove that overeating causes obesity, it can draw attention to a relationship that might be worth investigating.

Cross-sectional studies can be categorized based on the nature of the data collection and the type of data being sought.

Analytical Studies

In analytical cross-sectional studies, researchers investigate an association between two parameters. They collect data for exposures and outcomes at one specific time to measure an association between an exposure and a condition within a defined population.

The purpose of this type of study is to compare health outcome differences between exposed and unexposed individuals.

Descriptive Studies

- Descriptive cross-sectional studies are purely used to characterize and assess the prevalence and distribution of one or many health outcomes in a defined population.

- They can assess how frequently, widely, or severely a specific variable occurs throughout a specific demographic.

- This is the most common type of cross-sectional study.

- Evaluating the COVID-19 positivity rates among vaccinated and unvaccinated adolescents

- Investigating the prevalence of dysfunctional breathing in patients treated for asthma in primary care (Wang & Cheng, 2020)

- Analyzing whether individuals in a community have any history of mental illness and whether they have used therapy to help with their mental health

- Comparing grades of elementary school students whose parents come from different income levels

- Determining the association between gender and HIV status (Setia, 2016)

- Investigating suicide rates among individuals who have at least one parent with chronic depression

- Assessing the prevalence of HIV and risk behaviors in male sex workers (Shinde et al., 2009)

- Examining sleep quality and its demographic and psychological correlates among university students in Ethiopia (Lemma et al., 2012)

- Calculating what proportion of people served by a health clinic in a particular year have high cholesterol

- Analyzing college students’ distress levels with regard to their year level (Leahy et al., 2010)

Simple and Inexpensive

These studies are quick, cheap, and easy to conduct as they do not require any follow-up with subjects and can be done through self-report surveys.

Minimal room for error

Because all of the variables are analyzed at once, and data does not need to be collected multiple times, there will likely be fewer mistakes as a higher level of control is obtained.

Multiple variables and outcomes can be researched and compared at once

Researchers are able to look at numerous characteristics (ie, age, gender, ethnicity, and education level) in one study.

The data can be a starting point for future research

The information obtained from cross-sectional studies enables researchers to conduct further data analyses to explore any causal relationships in more depth.

Limitations

Does not help determine cause and effect.

Cross-sectional studies can be influenced by an antecedent consequent bias which occurs when it cannot be determined whether exposure preceded disease. (Alexander et al.)

Report bias is probable

Cross-sectional studies rely on surveys and questionnaires, which might not result in accurate reporting as there is no way to verify the information presented.

The timing of the snapshot is not always representative

Cross-sectional studies do not provide information from before or after the report was recorded and only offer a single snapshot of a point in time.

It cannot be used to analyze behavior over a period of time

Cross-sectional studies are designed to look at a variable at a particular moment, while longitudinal studies are more beneficial for analyzing relationships over extended periods.

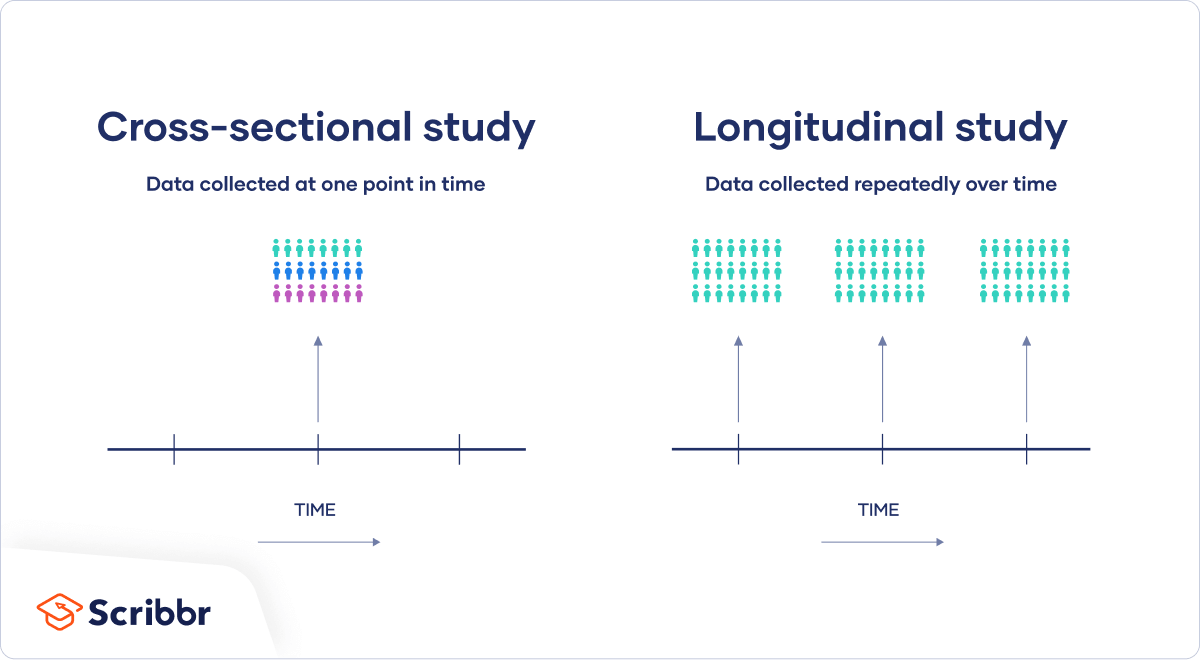

Cross-Sectional vs. Longitudinal

Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies are observational and do not require any interference or manipulation of the study environment.

However, cross-sectional studies differ from longitudinal studies in that cross-sectional studies look at a characteristic of a population at a specific point in time, while longitudinal studies involve studying a population over an extended period.

Longitudinal studies require more time and resources and can be less valid as participants might quit the study before the data has been fully collected.

Unlike cross-sectional studies, researchers can use longitudinal data to detect changes in a population and, over time, establish patterns among subjects.

Cross-sectional studies can be done much quicker than longitudinal studies and are a good starting point to establish any associations between variables, while longitudinal studies are more timely but are necessary for studying cause and effect.

Alexander, L. K., Lopez, B., Ricchetti-Masterson, K., & Yeatts, K. B. (n.d.). Cross-sectional Studies. Eric Notebook. Retrieved from https://sph.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/112/2015/07/nciph_ERIC8.pdf

Cherry, K. (2019, October 10). How Does the Cross-Sectional Research Method Work? Verywell Mind. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-cross-sectional-study-2794978

Cross-sectional vs. longitudinal studies. Institute for Work & Health. (2015, August). Retrieved from https://www.iwh.on.ca/what-researchers-mean-by/cross-sectional-vs-longitudinal-studies

Leahy, C. M., Peterson, R. F., Wilson, I. G., Newbury, J. W., Tonkin, A. L., & Turnbull, D. (2010). Distress levels and self-reported treatment rates for medicine, law, psychology and mechanical engineering tertiary students: cross-sectional study. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry, 44(7), 608–615.

Lemma, S., Gelaye, B., Berhane, Y. et al. Sleep quality and its psychological correlates among university students in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 12, 237 (2012).

Wang, X., & Cheng, Z. (2020). Cross-Sectional Studies: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Recommendations. Chest, 158(1S), S65–S71.

Setia M. S. (2016). Methodology Series Module 3: Cross-sectional Studies. Indian journal of dermatology, 61 (3), 261–264.

Shinde S, Setia MS, Row-Kavi A, Anand V, Jerajani H. Male sex workers: Are we ignoring a risk group in Mumbai, India? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:41–6.

Further Information

- Setia, M. S. (2016). Methodology series module 3: Cross-sectional studies. Indian journal of dermatology, 61(3), 261.

- Sedgwick, P. (2014). Cross sectional studies: advantages and disadvantages. Bmj, 348.

1. Are cross-sectional studies qualitative or quantitative?

Cross-sectional studies can be either qualitative or quantitative , depending on the type of data they collect and how they analyze it. Often, the two approaches are combined in mixed-methods research to get a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem.

2. What’s the difference between cross-sectional and cohort studies?

A cohort study is a type of longitudinal study that samples a group of people with a common characteristic. One key difference is that cross-sectional studies measure a specific moment in time, whereas cohort studies follow individuals over extended periods.

Another difference between these two types of studies is the subject pool. In cross-sectional studies, researchers select a sample population and gather data to determine the prevalence of a problem.

Cohort studies, on the other hand, begin by selecting a population of individuals who are already at risk for a specific disease.

3. What’s the difference between cross-sectional and case-control studies?

Case-control studies differ from cross-sectional studies in that case-control studies compare groups retrospectively and cannot be used to calculate relative risk.

In these studies, researchers study one group of people who have developed a particular condition and compare them to a sample without the disease.

Case-control studies are used to determine what factors might be associated with the condition and help researchers form hypotheses about a population.

4. Does a cross-sectional study have a control group?

A cross-sectional study does not need to have a control group , as the population studied is not selected based on exposure.

In a cross-sectional study, data are collected from a sample of the target population at a specific point in time, and everyone in the sample is assessed in the same way. There isn’t a manipulation of variables or a control group as there would be in an experimental study design.

5. Is a cross-sectional study prospective or retrospective?

A cross-sectional study is generally considered neither prospective nor retrospective because it provides a “snapshot” of a population at a single point in time.

Cross-sectional studies are not designed to follow individuals forward in time ( prospective ) or look back at historical data ( retrospective ), as they analyze data from a specific point in time.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Cross-Sectional Study | Definitions, Uses & Examples

Cross-Sectional Study | Definitions, Uses & Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Lauren Thomas .

A cross-sectional study is a type of research design in which you collect data from many different individuals at a single point in time. In cross-sectional research, you observe variables without influencing them.

Researchers in economics, psychology, medicine, epidemiology, and the other social sciences all make use of cross-sectional studies in their work. For example, epidemiologists who are interested in the current prevalence of a disease in a certain subset of the population might use a cross-sectional design to gather and analyse the relevant data.

Table of contents

Cross-sectional vs longitudinal studies, when to use a cross-sectional design, how to perform a cross-sectional study, advantages and disadvantages of cross-sectional studies, frequently asked questions about cross-sectional studies.

The opposite of a cross-sectional study is a longitudinal study . While cross-sectional studies collect data from many subjects at a single point in time, longitudinal studies collect data repeatedly from the same subjects over time, often focusing on a smaller group of individuals connected by a common trait.

Both types are useful for answering different kinds of research questions . A cross-sectional study is a cheap and easy way to gather initial data and identify correlations that can then be investigated further in a longitudinal study.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

When you want to examine the prevalence of some outcome at a certain moment in time, a cross-sectional study is the best choice.

Sometimes a cross-sectional study is the best choice for practical reasons – for instance, if you only have the time or money to collect cross-sectional data, or if the only data you can find to answer your research question were gathered at a single point in time.

As cross-sectional studies are cheaper and less time-consuming than many other types of study, they allow you to easily collect data that can be used as a basis for further research.

Descriptive vs analytical studies

Cross-sectional studies can be used for both analytical and descriptive purposes:

- An analytical study tries to answer how or why a certain outcome might occur.

- A descriptive study only summarises said outcome using descriptive statistics.

To implement a cross-sectional study, you can rely on data assembled by another source or collect your own. Governments often make cross-sectional datasets freely available online.

Prominent examples include the censuses of several countries like the US or France , which survey a cross-sectional snapshot of the country’s residents on important measures. International organisations like the World Health Organization or the World Bank also provide access to cross-sectional datasets on their websites.

However, these datasets are often aggregated to a regional level, which may prevent the investigation of certain research questions. You will also be restricted to whichever variables the original researchers decided to study.

If you want to choose the variables in your study and analyse your data on an individual level, you can collect your own data using research methods such as surveys . It’s important to carefully design your questions and choose your sample .

Like any research design , cross-sectional studies have various benefits and drawbacks.

- Because you only collect data at a single point in time, cross-sectional studies are relatively cheap and less time-consuming than other types of research.

- Cross-sectional studies allow you to collect data from a large pool of subjects and compare differences between groups.

- Cross-sectional studies capture a specific moment in time. National censuses, for instance, provide a snapshot of conditions in that country at that time.

Disadvantages

- It is difficult to establish cause-and-effect relationships using cross-sectional studies, since they only represent a one-time measurement of both the alleged cause and effect.

- Since cross-sectional studies only study a single moment in time, they cannot be used to analyse behavior over a period of time or establish long-term trends.

- The timing of the cross-sectional snapshot may be unrepresentative of behaviour of the group as a whole. For instance, imagine you are looking at the impact of psychotherapy on an illness like depression. If the depressed individuals in your sample began therapy shortly before the data collection, then it might appear that therapy causes depression even if it is effective in the long term.

Longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies are two different types of research design . In a cross-sectional study you collect data from a population at a specific point in time; in a longitudinal study you repeatedly collect data from the same sample over an extended period of time.

Cross-sectional studies are less expensive and time-consuming than many other types of study. They can provide useful insights into a population’s characteristics and identify correlations for further research.

Sometimes only cross-sectional data are available for analysis; other times your research question may only require a cross-sectional study to answer it.

Cross-sectional studies cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship or analyse behaviour over a period of time. To investigate cause and effect, you need to do a longitudinal study or an experimental study .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Thomas, L. (2022, May 05). Cross-Sectional Study | Definitions, Uses & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/cross-sectional-design/

Is this article helpful?

Lauren Thomas

Other students also liked, longitudinal study | definition, approaches & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples, correlational research | guide, design & examples.

How to choose your study design

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Medicine, Sydney Medical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

- PMID: 32479703

- DOI: 10.1111/jpc.14929

Research designs are broadly divided into observational studies (i.e. cross-sectional; case-control and cohort studies) and experimental studies (randomised control trials, RCTs). Each design has a specific role, and each has both advantages and disadvantages. Moreover, while the typical RCT is a parallel group design, there are now many variants to consider. It is important that both researchers and paediatricians are aware of the role of each study design, their respective pros and cons, and the inherent risk of bias with each design. While there are numerous quantitative study designs available to researchers, the final choice is dictated by two key factors. First, by the specific research question. That is, if the question is one of 'prevalence' (disease burden) then the ideal is a cross-sectional study; if it is a question of 'harm' - a case-control study; prognosis - a cohort and therapy - a RCT. Second, by what resources are available to you. This includes budget, time, feasibility re-patient numbers and research expertise. All these factors will severely limit the choice. While paediatricians would like to see more RCTs, these require a huge amount of resources, and in many situations will be unethical (e.g. potentially harmful intervention) or impractical (e.g. rare diseases). This paper gives a brief overview of the common study types, and for those embarking on such studies you will need far more comprehensive, detailed sources of information.

Keywords: experimental studies; observational studies; research method.

© 2020 Paediatrics and Child Health Division (The Royal Australasian College of Physicians).

- Case-Control Studies

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Research Design*

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Do Cross-Sectional Studies Work?

Gathering Data From a Single Point in Time

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

What Is a Cross-Sectional Study?

- Defining Characteristics

Advantages of Cross-Sectional Studies

Challenges of cross-sectional studies, cross-sectional vs. longitudinal studies.

Verywell / Jessica Olah

A cross-sectional study looks at data at a single point in time. The participants in this type of study are selected based on particular variables of interest. Cross-sectional studies are often used in developmental psychology , but this method is also used in many other areas, including social science and education.

Cross-sectional studies are observational in nature and are known as descriptive research, not causal or relational, meaning that you can't use them to determine the cause of something, such as a disease. Researchers record the information that is present in a population, but they do not manipulate variables .

This type of research can be used to describe characteristics that exist in a community, but not to determine cause-and-effect relationships between different variables. This method is often used to make inferences about possible relationships or to gather preliminary data to support further research and experimentation.

Example: Researchers studying developmental psychology might select groups of people who are different ages but investigate them at one point in time. By doing this, any differences among the age groups can be attributed to age differences rather than something that happened over time.

Defining Characteristics of Cross-Sectional Studies

Some of the key characteristics of a cross-sectional study include:

- The study takes place at a single point in time

- It does not involve manipulating variables

- It allows researchers to look at numerous characteristics at once (age, income, gender, etc.)

- It's often used to look at the prevailing characteristics in a given population

- It can provide information about what is happening in a current population

Think of a cross-sectional study as a snapshot of a particular group of people at a given point in time. Unlike longitudinal studies, which look at a group of people over an extended period, cross-sectional studies are used to describe what is happening at the present moment.This type of research is frequently used to determine the prevailing characteristics in a population at a certain point in time. For example, a cross-sectional study might be used to determine if exposure to specific risk factors might correlate with particular outcomes.

A researcher might collect cross-sectional data on past smoking habits and current diagnoses of lung cancer, for example. While this type of study cannot demonstrate cause and effect, it can provide a quick look at correlations that may exist at a particular point.

For example, researchers may find that people who reported engaging in certain health behaviors were also more likely to be diagnosed with specific ailments. While a cross-sectional study cannot prove for certain that these behaviors caused the condition, such studies can point to a relationship worth investigating further.

Cross-sectional studies are popular because they have several benefits that are useful to researchers.

Inexpensive and Fast

Cross-sectional studies typically allow researchers to collect a great deal of information quickly. Data is often obtained inexpensively using self-report surveys . Researchers are then able to amass large amounts of information from a large pool of participants.

For example, a university might post a short online survey about library usage habits among biology majors, and the responses would be recorded in a database automatically for later analysis. This is a simple, inexpensive way to encourage participation and gather data across a wide swath of individuals who fit certain criteria.

Can Assess Multiple Variables

Researchers can collect data on a few different variables to see how they affect a certain condition. For example, differences in sex, age, educational status, and income might correlate with voting tendencies or give market researchers clues about purchasing habits.

Might Prompt Further Study

Although researchers can't use cross-sectional studies to determine causal relationships, these studies can provide useful springboards to further research. For example, when looking at a public health issue, such as whether a particular behavior might be linked to a particular illness, researchers might utilize a cross-sectional study to look for clues that can spur further experimental studies.

For example, researchers might be interested in learning how exercise influences cognitive health as people age. They might collect data from different age groups on how much exercise they get and how well they perform on cognitive tests. Conducting such a study can give researchers clues about the types of exercise that might be most beneficial to the elderly and inspire further experimental research on the subject.

No method of research is perfect. Cross-sectional studies also have potential drawbacks.

Difficulties in Determining Causal Effects

Researchers can't always be sure that the conditions a cross-sectional study measures are the result of a particular factor's influence. In many cases, the differences among individuals could be attributed to variation among the study subjects. In this way, cause-and-effect relationships are more difficult to determine in a cross-sectional study than they are in a longitudinal study. This type of research simply doesn't allow for conclusions about causation.

For example, a study conducted some 20 years ago queried thousands of women about their consumption of diet soft drinks. The results of the study, published in the medical journal Stroke , associated diet soft drink intake with stroke risk that was greater than that of those who did not consume such beverages. In other words, those who drank lots of diet soda were more prone to strokes. However, correlation does not equal causation. The increased stroke risk might arise from any number of factors that tend to occur among those who drink diet beverages. For example, people who consume sugar-free drinks might be more likely to be overweight or diabetic than those who drink the regular versions. Therefore, they might be at greater risk of stroke—regardless of what they drink.

Cohort Differences

Groups can be affected by cohort differences that arise from the particular experiences of a group of people. For example, individuals born during the same period might witness the same important historical events, but their geographic regions, religious affiliations, political beliefs, and other factors might affect how they perceive such events.

Report Biases

Surveys and questionnaires about certain aspects of people's lives might not always result in accurate reporting. For example, respondents might not disclose certain behaviors or beliefs out of embarrassment, fear, or other limiting perception. Typically, no mechanism for verifying this information exists.

Cross-sectional research differs from longitudinal studies in several important ways. The key difference is that a cross-sectional study is designed to look at a variable at a particular point in time. A longitudinal study evaluates multiple measures over an extended period to detect trends and changes.

Evaluates variable at single point in time

Participants less likely to drop out

Uses new participant(s) with each study

Measures variable over time

Requires more resources

More expensive

Subject to selective attrition

Follows same participants over time

Longitudinal studies tend to require more resources; these are often more expensive than those used by cross-sectional studies. They are also more likely to be influenced by what is known as selective attrition , which means that some individuals are more likely to drop out of a study than others. Because a longitudinal study occurs over a span of time, researchers can lose track of subjects. Individuals might lose interest, move to another city, change their minds about participating, etc. This can influence the validity of the study.

One of the advantages of cross-sectional studies is that data is collected all at once, so participants are less likely to quit the study before data is fully collected.

A Word From Verywell

Cross-sectional studies can be useful research tools in many areas of health research. By learning about what is going on in a specific population, researchers can improve their understanding of relationships among certain variables and develop additional studies that explore these conditions in greater depth.

Levin KA. Study design III: Cross-sectional studies . Evid Based Dent . 2006;7(1):24-5. doi:10.1038/sj.ebd.6400375

Morin JF, Olsson C, Atikcan EO, eds. Research Methods in the Social Sciences: An A-Z of Key Concepts . Oxford University Press; 2021.

Abbasi J. Unpacking a recent study linking diet soda with stroke risks . JAMA . 2019;321(16):1554-1555. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.2123

Setia MS. Methodology series module 3: Cross-sectional studies . Indian J Dermatol . 2016;61(3):261-4. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.182410

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 20, Issue 1

- Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Department of Accident and Emergency Medicine, Taunton and Somerset Hospital, Taunton, Somerset, UK

- Correspondence to: Dr C J Mann; tonygood{at}doctors.org.uk

Cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies are collectively referred to as observational studies. Often these studies are the only practicable method of studying various problems, for example, studies of aetiology, instances where a randomised controlled trial might be unethical, or if the condition to be studied is rare. Cohort studies are used to study incidence, causes, and prognosis. Because they measure events in chronological order they can be used to distinguish between cause and effect. Cross sectional studies are used to determine prevalence. They are relatively quick and easy but do not permit distinction between cause and effect. Case controlled studies compare groups retrospectively. They seek to identify possible predictors of outcome and are useful for studying rare diseases or outcomes. They are often used to generate hypotheses that can then be studied via prospective cohort or other studies.

- research methods

- cohort study

- case-control study

- cross sectional study

https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.20.1.54

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies are often referred to as observational studies because the investigator simply observes. No interventions are carried out by the investigator. With the recent emphasis on evidence based medicine and the formation of the Cochrane Database of randomised controlled trials, such studies have been somewhat glibly maligned. However, they remain important because many questions can be efficiently answered by these methods and sometimes they are the only methods available.

The objective of most clinical studies is to determine one of the following—prevalence, incidence, cause, prognosis, or effect of treatment; it is therefore useful to remember which type of study is most commonly associated with each objective (table 1)

- View inline

While an appropriate choice of study design is vital, it is not sufficient. The hallmark of good research is the rigor with which it is conducted. A checklist of the key points in any study irrespective of the basic design is given in box 1.

Study purpose

The aim of the study should be clearly stated.

The sample should accurately reflect the population from which it is drawn.

The source of the sample should be stated.

The sampling method should be described and the sample size should be justified.

Entry criteria and exclusions should be stated and justified.

The number of patients lost to follow up should be stated and explanations given.

Control group

The control group should be easily identifiable.

The source of the controls should be explained—are they from the same population as the sample?

Are the controls matched or randomised—to minimise bias and confounding.

Quality of measurements and outcomes

Validity—are the measurements used regarded as valid by other investigators?

Reproducibility—can the results be repeated or is there a reason to suspect they may be a “one off”?

Blinded—were the investigators or subjects aware of their subject/control allocation?

Quality control—has the methodology been rigorously adhered to?

Completeness

Compliance—did all patients comply with the study?

Drop outs—how many failed to complete the study?

Missing data—how much are unavailable and why?

Distorting influences

Extraneous treatments—other interventions that may have affected some but not all of the subjects.

Confounding factors—Are there other variables that might influence the results?

Appropriate analysis—Have appropriate statistical tests been used?

All studies should be internally valid. That is, the conclusions can be logically drawn from the results produced by an appropriate methodology. For a study to be regarded as valid it must be shown that it has indeed demonstrated what it says it has. A study that is not internally valid should not be published because the findings cannot be accepted.

The question of external validity relates to the value of the results of the study to other populations—that is, the generalisability of the results. For example, a study showing that 80% of the Swedish population has blond hair, might be used to make a sensible prediction of the incidence of blond hair in other Scandinavian countries, but would be invalid if applied to most other populations.

Every published study should contain sufficient information to allow the reader to analyse the data with reference to these key points.

In this article each of the three important observational research methods will be discussed with emphasis on their strengths and weaknesses. In so doing it should become apparent why a given study used a particular research method and which method might best answer a particular clinical problem.

COHORT STUDIES

These are the best method for determining the incidence and natural history of a condition. The studies may be prospective or retrospective and sometimes two cohorts are compared.

Prospective cohort studies

A group of people is chosen who do not have the outcome of interest (for example, myocardial infarction). The investigator then measures a variety of variables that might be relevant to the development of the condition. Over a period of time the people in the sample are observed to see whether they develop the outcome of interest (that is, myocardial infarction).

In single cohort studies those people who do not develop the outcome of interest are used as internal controls.

Where two cohorts are used, one group has been exposed to or treated with the agent of interest and the other has not, thereby acting as an external control.

Retrospective cohort studies

These use data already collected for other purposes. The methodology is the same but the study is performed posthoc. The cohort is “followed up” retrospectively. The study period may be many years but the time to complete the study is only as long as it takes to collate and analyse the data.

Advantages and disadvantages

The use of cohorts is often mandatory as a randomised controlled trial may be unethical; for example, you cannot deliberately expose people to cigarette smoke or asbestos. Thus research on risk factors relies heavily on cohort studies.

As cohort studies measure potential causes before the outcome has occurred the study can demonstrate that these “causes” preceded the outcome, thereby avoiding the debate as to which is cause and which is effect.

A further advantage is that a single study can examine various outcome variables. For example, cohort studies of smokers can simultaneously look at deaths from lung, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular disease. This contrasts with case-control studies as they assess only one outcome variable (that is, whatever outcome the cases have entered the study with).

Cohorts permit calculation of the effect of each variable on the probability of developing the outcome of interest (relative risk). However, where a certain outcome is rare then a prospective cohort study is inefficient. For example, studying 100 A&E attenders with minor injuries for the outcome of diabetes mellitus will probably produce only one patient with the outcome of interest. The efficiency of a prospective cohort study increases as the incidence of any particular outcome increases. Thus a study of patients with a diagnosis of deliberate self harm in the 12 months after initial presentation would be efficiently studied using a cohort design.

Another problem with prospective cohort studies is the loss of some subjects to follow up. This can significantly affect the outcome. Taking incidence analysis as an example (incidence = cases/per period of time), it can be seen that the loss of a few cases will seriously affect the numerator and hence the calculated incidence. The rarer the condition the more significant this effect.

Retrospective studies are much cheaper as the data have already been collected. One advantage of such a study design is the lack of bias because the outcome of current interest was not the original reason for the data to be collected. However, because the cohort was originally constructed for another purpose it is unlikely that all the relevant information will have been rigorously collected.

Retrospective cohorts also suffer the disadvantage that people with the outcome of interest are more likely to remember certain antecedents, or exaggerate or minimise what they now consider to be risk factors (recall bias).

Where two cohorts are compared one will have been exposed to the agent of interest and one will not. The major disadvantage is the inability to control for all other factors that might differ between the two groups. These factors are known as confounding variables.

A confounding variable is independently associated with both the variable of interest and the outcome of interest. For example, lung cancer (outcome) is less common in people with asthma (variable). However, it is unlikely that asthma in itself confers any protection against lung cancer. It is more probable that the incidence of lung cancer is lower in people with asthma because fewer asthmatics smoke cigarettes (confounding variable). There are a virtually infinite number of potential confounding variables that, however unlikely, could just explain the result. In the past this has been used to suggest that there is a genetic influence that makes people want to smoke and also predisposes them to cancer.

The only way to eliminate all possibility of a confounding variable is via a prospective randomised controlled study. In this type of study each type of exposure is assigned by chance and so confounding variables should be present in equal numbers in both groups.

Finally, problems can arise as a result of bias. Bias can occur in any research and reflects the potential that the sample studied is not representative of the population it was drawn from and/or the population at large. A classic example is using employed people, as employment is itself associated with generally better health than unemployed people. Similarly people who respond to questionnaires tend to be fitter and more motivated than those who do not. People attending A&E departments should not be presumed to be representative of the population at large.

How to run a cohort study

If the data are readily available then a retrospective design is the quickest method. If high quality, reliable data are not available a prospective study will be required.

The first step is the definition of the sample group. Each subject must have the potential to develop the outcome of interest (that is, circumcised men should not be included in a cohort designed to study paraphimosis). Furthermore, the sample population must be representative of the general population if the study is primarily looking at the incidence and natural history of the condition (descriptive).

If however the aim is to analyse the relation between predictor variables and outcomes (analytical) then the sample should contain as many patients likely to develop the outcome as possible, otherwise much time and expense will be spent collecting information of little value.

Cohort studies

Cohort studies describe incidence or natural history.

They analyse predictors (risk factors) thereby enabling calculation of relative risk.

Cohort studies measure events in temporal sequence thereby distinguishing causes from effects.

Retrospective cohorts where available are cheaper and quicker.

Confounding variables are the major problem in analysing cohort studies.

Subject selection and loss to follow up is a major potential cause of bias.

Each variable studied must be accurately measured. Variables that are relatively fixed, for example, height need only be recorded once. Where change is more probable, for example, drug misuse or weight, repeated measurements will be required.

To minimise the potential for missing a confounding variable all probable relevant variables should be measured. If this is not done the study conclusions can be readily criticised. All patients entered into the study should also be followed up for the duration of the study. Losses can significantly affect the validity of the results. To minimise this as much information about the patient (name, address, telephone, GP, etc) needs to be recorded as soon as the patient is entered into the study. Regular contact should be made; it is hardly surprising if the subjects have moved or lost interest and become lost to follow up if they are only contacted at 10 year intervals!

Beware, follow up is usually easier in people who have been exposed to the agent of interest and this may lead to bias.

There are many famous examples of Cohort studies including the Framingham heart study, 2 the UK study of doctors who smoke 3 and Professor Neville Butler‘s studies on British children born in 1958. 4 A recent example of a prospective cohort study by Davey Smith et al was published in the BMJ 5 and a retrospective cohort design was used to assess the use of A&E departments by people with diabetes. 6

CROSS SECTIONAL STUDIES

These are primarily used to determine prevalence. Prevalence equals the number of cases in a population at a given point in time. All the measurements on each person are made at one point in time. Prevalence is vitally important to the clinician because it influences considerably the likelihood of any particular diagnosis and the predictive value of any investigation. For example, knowing that ascending cholangitis in children is very rare enables the clinician to look for other causes of abdominal pain in this patient population.

Cross sectional studies are also used to infer causation.

At one point in time the subjects are assessed to determine whether they were exposed to the relevant agent and whether they have the outcome of interest. Some of the subjects will not have been exposed nor have the outcome of interest. This clearly distinguishes this type of study from the other observational studies (cohort and case controlled) where reference to either exposure and/or outcome is made.

The advantage of such studies is that subjects are neither deliberately exposed, treated, or not treated and hence there are seldom ethical difficulties. Only one group is used, data are collected only once and multiple outcomes can be studied; thus this type of study is relatively cheap.

Many cross sectional studies are done using questionnaires. Alternatively each of the subjects may be interviewed. Table 2 lists the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Any study with a low response rate can be criticised because it can miss significant differences in the responders and non-responders. At its most extreme all the non-responders could be dead! Strenuous efforts must be made to maximise the numbers who do respond. The use of volunteers is also problematic because they too are unlikely to be representative of the general population. A good way to produce a valid sample would be to randomly select people from the electoral role and invite them to complete a questionnaire. In this way the response rate is known and non-responders can be identified. However, the electoral role itself is not an entirely accurate reflection of the general population. A census is another example of a cross sectional study.

Market research organisations often use cross sectional studies (for example, opinion polls). This entails a system of quotas to ensure the sample is representative of the age, sex, and social class structure of the population being studied. However, to be commercially viable they are convenience samples—only people available can be questioned. This technique is insufficiently rigorous to be used for medical research.

How to run a cross sectional study

Formulate the research question(s) and choose the sample population. Then decide what variables of the study population are relevant to the research question. A method for contacting sample subjects must be devised and then implemented. In this way the data are collected and can then be analysed

The most important advantage of cross sectional studies is that in general they are quick and cheap. As there is no follow up, less resources are required to run the study.

Cross sectional studies are the best way to determine prevalence and are useful at identifying associations that can then be more rigorously studied using a cohort study or randomised controlled study.

The most important problem with this type of study is differentiating cause and effect from simple association. For example, a study finding an association between low CD4 counts and HIV infection does not demonstrate whether HIV infection lowers CD4 levels or low CD4 levels predispose to HIV infection. Moreover, male homosexuality is associated with both but causes neither. (Another example of a confounding variable).

Often there are a number of plausible explanations. For example, if a study shows a negative relation between height and age it could be concluded that people lose height as they get older, younger generations are getting taller, or that tall people have a reduced life expectancy when compared with short people. Cross sectional studies do not provide an explanation for their findings.

Rare conditions cannot efficiently be studied using cross sectional studies because even in large samples there may be no one with the disease. In this situation it is better to study a cross sectional sample of patients who already have the disease (a case series). In this way it was found in 1983 that of 1000 patients with AIDS, 727 were homosexual or bisexual men and 236 were intrvenous drug abusers. 6 The conclusion that individuals in these two groups had a higher relative risk was inescapable. The natural history of HIV infection was then studied using cohort studies and efficacy of treatments via case controlled studies and randomised clinical trials.

An example of a cross sectional study was the prevalence study of skull fractures in children admitted to hospital in Edinburgh from 1983 to 1989. 7 Note that although the study period was seven years it was not a longitudinal or cohort study because information about each subject was recorded at a single point in time.

A questionnaire based cross sectional study explored the relation between A&E attendance and alcohol consumption in elderly persons. 9

A recent example can be found in the BMJ , in which the prevalence of serious eye disease in a London population was evaluated. 10

Cross sectional studies

Cross sectional studies are the best way to determine prevalence

Are relatively quick

Can study multiple outcomes

Do not themselves differentiate between cause and effect or the sequence of events

CASE-CONTROL STUDIES

In contrast with cohort and cross sectional studies, case-control studies are usually retrospective. People with the outcome of interest are matched with a control group who do not. Retrospectively the researcher determines which individuals were exposed to the agent or treatment or the prevalence of a variable in each of the study groups. Where the outcome is rare, case-control studies may be the only feasible approach.

As some of the subjects have been deliberately chosen because they have the disease in question case-control studies are much more cost efficient than cohort and cross sectional studies—that is, a higher percentage of cases per study.

Case-control studies determine the relative importance of a predictor variable in relation to the presence or absence of the disease. Case-control studies are retrospective and cannot therefore be used to calculate the relative risk; this a prospective cohort study. Case-control studies can however be used to calculate odds ratios, which in turn, usually approximate to the relative risk.

How to run a case-control study

Decide on the research question to be answered. Formulate an hypothesis and then decide what will be measured and how. Specify the characteristics of the study group and decide how to construct a valid control group. Then compare the “exposure” of the two groups to each variable.

When conditions are uncommon, case-control studies generate a lot of information from relatively few subjects. When there is a long latent period between an exposure and the disease, case-control studies are the only feasible option. Consider the practicalities of a cohort study or cross sectional study in the assessment of new variant CJD and possible aetiologies. With less than 300 confirmed cases a cross sectional study would need about 200 000 subjects to include one symptomatic patient. Given a postulated latency of 10 to 30 years a cohort study would require both a vast sample size and take a generation to complete.

In case-control studies comparatively few subjects are required so more resources are available for studying each. In consequence a huge number of variables can be considered. This type of study is therefore useful for generating hypotheses that can then be tested using other types of study.

This flexibility of the variables studied comes at the expense of the restricted outcomes studied. The only outcome is the presence or absence of the disease or whatever criteria was chosen to select the cases.

The major problems with case-control studies are the familiar ones of confounding variables (see above) and bias. Bias may take two major forms.

Sampling bias

The patients with the disease may be a biased sample (for example, patients referred to a teaching hospital) or the controls may be biased (for example, volunteers, different ages, sex or socioeconomic group).

Observation and recall bias

As the study assesses predictor variables retrospectively there is great potential for a biased assessment of their presence and significance by the patient or the investigator, or both.

Overcoming sampling bias

Ideally the cases studied should be a random sample of all the patients with the disease. This is not only very difficult but in many instances is impossible because many cases may not have been diagnosed or have been misdiagnosed. For example, many cases of non-insulin dependent diabetes will not have sought medical attention and therefore be undiagnosed. Conversely many psychiatric diseases may be differently labelled in different countries and even by different doctors in the same country. As a result they will be misdiagnosed for the purposes of the study. However, in reality you are often left studying a sample of those patients who it is possible to recruit. Selecting the controls is often a more difficult problem.

To enable the controls to represent the same population as the cases, one of four techniques may be used.

A convenience sample—sampled in the same way as the cases, for example, attending the same outpatient department. While this is certainly convenient it may reduce the external validity of the study.

Matching—the controls may be a matched or unmatched random sample from the unaffected population. Again the problems of controlling for unknown influences is present but if the controls are too closely matched they may not be representative of the general population. “Over matching” may cause the true difference to be underestimated.

The advantage of matching is that it allows a smaller sample size for any given effect to be statistically significant.

Using two or more control groups. If the study demonstrates a significant difference between the patients with the outcome of interest and those without, even when the latter have been sampled in a number of different ways (for example, outpatients, in patients, GP patients) then the conclusion is more robust.

Using a population based sample for both cases and controls. It is possible to take a random sample of all the patients with a particular disease from specific registers. The control group can then be constructed by selecting age and sex matched people randomly selected from the same population as the area covered by the disease register.

Overcoming observation and recall bias

Overcoming retrospective recall bias can be achieved by using data recorded, for other purposes, before the outcome had occurred and therefore before the study had started. The success of this strategy is limited by the availability and reliability of the data collected. Another technique is blinding where neither the subject nor the observer know if they are a case or control subject. Nor are they aware of the study hypothesis. In practice this is often difficult or impossible and only partial blinding is practicable. It is usually possible to blind the subjects and observers to the study hypothesis by asking spurious questions. Observers can also be easily blinded to the case or control status of the patient where the relevant observation is not of the patient themselves but a laboratory test or radiograph.

Case-control studies

Case-control studies are simple to organise

Retrospectively compare two groups

Aim to identify predictors of an outcome

Permit assessment of the influence of predictors on outcome via calculation of an odds ratio

Useful for hypothesis generation

Can only look at one outcome

Bias is an major problem

Blinding cases to their case or control status is usually impracticable as they already know that they have a disease or illness. Similarly observers can hardly be blinded to the presence of physical signs, for example, cyanosis or dyspnoea.

As a result of the problems of matching, bias and confounding, case-control studies, are often flawed. They are however useful for generating hypotheses. These hypotheses can then be tested more rigorously by other methods—randomised controlled trials or cohort studies.

Case-control studies are very common. They are particularly useful for studying infrequent events, for example, cot death, survival from out of hospital cardiac arrest, and toxicological emergencies.

A recent example was the study of atrial fibrillation in middle aged men during exercise. 11

USING DATABASES FOR RESEARCH (SECONDARY DATA)

Pre-existing databases provide an excellent and convenient source of data. There are a host of such databases and the increasing archiving of information on computers means that this is an enlarging area for obtaining data. Table 3 lists some common examples of potentially useful databases.

Such databases enable vast numbers of people to be entered into a study prospectively or retrospectively. They can be used to construct a cohort, to produce a sample for a cross sectional study, or to identify people with certain conditions or outcomes and produce a sample for a case controlled study. A recent study used census data from 11 countries to look at the relation between social class and mortality in middle aged men. 12

These type of data are ordinarily collected by people other than the researcher and independently of any specific hypothesis. The opportunity for observer bias is thus diminished. The use of previously collected data is efficient and comparatively inexpensive and moreover the data are collected in a very standardised way, permitting comparisons over time and between different countries. However, because the data are collected for other purposes it may not be ideally suited to the testing of the current hypothesis, additionally it may be incomplete. This may result in sampling bias. For example, the electoral roll depends upon registration by each individual. Many homeless, mentally ill, and chronically sick people will not be registered. Similarly the notification of certain communicable diseases is a statutory responsibility for doctors in the UK: while it is probable that most cases of cholera are reported it is highly unlikely that most cases of food poisoning are.

Causes and associations

Because observational studies are not experiments (as are randomised controlled trials) it is difficult to control many external variables. In consequence when faced with a clear and significant association between some form of illness or cause of death and some environmental influence a judgement has to be made as to whether this is a causal link or simply an association. Table 4 outlines the points to be considered when making this judgement. 13

None of these judgements can provide indisputable evidence of cause and effect, but taken together they do permit the investigator to answer the fundamental questions “is there any other way to explain the available evidence?” and is there any other more likely than cause and effect?”

Qualitative studies can produce high quality information but all such studies can be influenced by known and unknown confounding variables. Appropriate use of observational studies permits investigation of prevalence, incidence, associations, causes, and outcomes. Where there is little evidence on a subject they are cost effective ways of producing and investigating hypotheses before larger and more expensive study designs are embarked upon. In addition they are often the only realistic choice of research methodology, particularly where a randomised controlled trial would be impractical or unethical.

Cohort studies look forwards in time by following up each subject

Subjects are selected before the outcome of interest is observed

They establish the sequence of events

Numerous outcomes can be studied

They are the best way to establish the incidence of a disease

They are a good way to determine causes of diseases

The principal summary statistic of cohort studies is the relative risk ratio

If prospective, they are expensive and often take a long time for sufficient outcome events to occur to produce meaningful results

Cross sectional studies look at each subject at one point in time only

Subjects are selected without regard to the outcome of interest

Less expensive

They are the best way to determine prevalence

The principal summary statistic of cross sectional studies is the odds ratio

Weaker evidence of causality than cohort studies

Inaccurate when studying rare conditions

Case-control studies look back at what has happened to each subject

Subjects are selected specifically on the basis of the outcome of interest

Efficient (small sample sizes)

Produce odds ratios that approximate to relative risks for each variable studied

Prone to sampling bias and retrospective analysis bias

Only one outcome is studied

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

The inclusion of subjects or methods such that the results obtained are not truly representative of the population from which it is drawn

The process by which the researcher and or the subject is ignorant of which intervention or exposure has occurred.

Cochrane database

An international collaborative project collating peer reviewed prospective randomised clinical trials.

Is a component of a population identified so that one or more characteristic can be studied as it ages through time.

Confounding variable

A variable that is associated with both the exposure and outcome of interest that is not the variable being studied.

A group of people without the condition of interest, or unexposed to or not treated with the agent of interest.

False positive

A test result that suggests that the subject has a specific disease or condition when in fact the subject does not.

Is a rate and therefore is always related either explicitly or by implication to a time period. With regard to disease it can be defined as the number of new cases that develop during a specified time interval.

A period of time between exposure to an agent and the development of symptoms, signs, or other evidence of changes associated with that exposure.

The process by which each case is matched with one or more controls, which have been deliberately chosen to be as similar as the test subjects in all regards other than the variable being studied.

Observational study

A study in which no intervention is made (in contrast with an experimental study). Such studies provide estimates and examine associations of events in their natural settings without recourse to experimental intervention.

The ratio of the probability of an event occurring to the probability of non-occurrence. In a clinical setting this would be equivalent to the odds of a condition occurring in the exposed group divided by the odds of it occurring in the non-exposed group.

Is not defined by a time interval and is therefore not a rate. It may be defined as the number of cases of a disease that exist in a defined population at a specified point in time.

Randomised controlled trial

Subjects are assigned by statistically randomised methods to two or more groups. In doing so it is assumed that all variables other than the proposed intervention are evenly distributed between the groups. In this way bias is minimised.

Relative risk

This is the ratio of the probability of developing the condition if exposed to a certain variable compared with the probability if not exposed.

Response rate

The proportion of subjects who respond to either a treatment or a questionnaire.

Risk factor

A variable associated with a specific disease or outcome.

Validity—internal

The rigour with which a study has been designed and executed—that is, can the conclusion be relied upon?

Validity—external

The usefulness of the findings of a study with respect to other populations.

A value or quality that can vary between subjects and/or over time

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Study design for cohort studies.

Study design for cross sectional studies

Study design for case-control studies.

- Fowkes F , Fulton P. Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. BMJ 1991 ; 302 : 1136 –40.

- ↵ Lerner DJ , Kannel WB. Patterns of coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality in the sexes: a 26 year follow-up of the Framingham population. Am Heart J 1986 ; 111 : 383 –90. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Doll R , Peto H. Mortality in relation to smoking. 40 years observation on female British doctors. BMJ 1989 ; 208 : 967 –73. OpenUrl

- ↵ Alberman ED , Butler NR, Sheridan MD. Visual acuity of a national sample (1958 cohort) at 7 years. Dev Med Child Neurol 1971 ; 13 : 9 –14. OpenUrl PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Davey Smith G , Hart C, Blane D, et al . Adverse socioeconomic conditions in childhood and cause specific mortality: prospective observational study. BMJ 1998 ; 316 : 1631 –5. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Goyder EC , Goodacre SW, Botha JL, et al . How do individuals with diabetes use the accident and emergency department? J Accid Emerg Med 1997 ; 14 : 371 –4. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Jaffe HW , Bregman DJ, Selik RM. Acquired immune deficiency in the US: the first 1000 cases. J Inf Dis 1983 ; 148 : 339 –45. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- Johnstone AJ , Zuberi SH, Scobie WH. Skull fractures in children: a population study. J Accid Emerg Med 1996 ; 13 : 386 –9. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ van der Pol V , Rodgers H, Aitken P, et al . Does alcohol contribute to accident and emergency department attendance in elderly people? J Accid Emerg Med 1996 ; 13 : 258 –60. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Reidy A , Minassian DC, Vafadis G, et al . BMJ 1998 ; 316 : 1643 –7. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Karjaleinen , Kujala U, Kaprio J, et al . BMJ 1998 ; 316 : 1784 –5. OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Kunst A , Groenhof F, Mackenbach J. BMJ 1998 ; 316 : 1636 –42. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Hill AB , Hill ID. Bradford Hills principles of medical statistics. 12th edn. London: Edward Arnold, 1991.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A case report describes the medical case of 1 particular patient. A cross-sectional study is a snapshot in time of a sample of participants chosen from the population. Goal. To report an interesting or unusual case of a patient. To describe the association between an exposure and an outcome.

A cross-sectional study is a cheap and easy way to gather initial data and identify correlations that can then be investigated further in a longitudinal study. Cross-sectional vs longitudinal example. You want to study the impact that a low-carb diet has on diabetes. You first conduct a cross-sectional study with a sample of diabetes patients ...

A case-control study differs from a cross-sectional study because case-control studies are naturally retrospective in nature, looking backward in time to identify exposures that may have occurred before the development of the disease. On the other hand, cross-sectional studies collect data on a population at a single point in time. The goal ...

cross-sectional studies take a snap shot (at a specific point of time) from the population and they assess the prevalence. case-control studies: sample cases based on the outcome. it helps if you ...

Cross sectional studies. A cross sectional study measures the prevalence of health outcomes or determinants of health, or both, in a population at a point in time or over a short period. Such information can be used to explore aetiology - for example, the relation between cataract and vitamin status has been examined in cross sectional surveys.

Observational studies monitor study participants without providing study interventions. This paper describes the cross-sectional design, examines the strengths and weaknesses, and discusses some methods to report the results. Future articles will focus on other observational methods, the cohort, and case-control designs.

The main types of studies are randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case-control studies and qualitative studies. An official website of the United States government. ... Cross-sectional studies. Many people will be familiar with this kind of study. The classic type of cross-sectional study is the survey: A representative group ...

Cross-Sectional vs. Longitudinal. A cross-sectional study design is a type of observational study, or descriptive research, that involves analyzing information about a population at a specific point in time. This design measures the prevalence of an outcome of interest in a defined population. It provides a snapshot of the characteristics of ...

Both types are useful for answering different kinds of research questions.A cross-sectional study is a cheap and easy way to gather initial data and identify correlations that can then be investigated further in a longitudinal study.. Example: Cross-sectional vs longitudinal. You want to study the impact that a low-carb diet has on diabetes.. You first conduct a cross-sectional study with a ...

Abstract. Cross-sectional study design is a type of observational study design. In a cross-sectional study, the investigator measures the outcome and the exposures in the study participants at the same time. Unlike in case-control studies (participants selected based on the outcome status) or cohort studies (participants selected based on the ...

3.1. Strengths: when to use cross-sectional data. The strengths of cross-sectional data help to explain their overuse in IS research. First, such studies can be conducted efficiently and inexpensively by distributing a survey to a convenient sample (e.g., the researcher's social network or students) (Compeau et al., 2012) or by using a crowdsourcing website (Lowry et al., 2016, Steelman et ...

Cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies are collectively referred to as observational studies. Observational studies are often the only practicable method of answering questions of aetiology, the natural history and treatment of rare conditions and instances where a randomised controlled trial might be unethical.

While there are numerous quantitative study designs available to researchers, the final choice is dictated by two key factors. First, by the specific research question. That is, if the question is one of 'prevalence' (disease burden) then the ideal is a cross-sectional study; if it is a question of 'harm' - a case-control study; prognosis - a ...

Cross-Sectional vs. Longitudinal Studies . Cross-sectional research differs from longitudinal studies in several important ways. The key difference is that a cross-sectional study is designed to look at a variable at a particular point in time. A longitudinal study evaluates multiple measures over an extended period to detect trends and changes.

between cause and effect. Cross sectional studies are used to determine prevalence. They are relatively quick and easy but do not permit distinction between cause and effect. Case controlled studies compare groups retrospectively. They seek to identify possible predictors of outcome and are useful for studying rare diseases or outcomes.

In medical research, social science, and biology, a cross-sectional study (also known as a cross-sectional analysis, transverse study, prevalence study) is a type of observational study that analyzes data from a population, or a representative subset, at a specific point in time—that is, cross-sectional data. [definition needed]In economics, cross-sectional studies typically involve the use ...

Cross-Sectional vs Longitudinal. Cross-sectional study. A cross-sectional study is an observational one. This means that researchers record information about their subjects without manipulating the study environment. In our study, we would simply measure the cholesterol levels of daily walkers and non-walkers along with any other ...

Cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies are collectively referred to as observational studies. Often these studies are the only practicable method of studying various problems, for example, studies of aetiology, instances where a randomised controlled trial might be unethical, or if the condition to be studied is rare.

Cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies are collectively referred to as observational studies. Often these studies are the only practicable method of studying various problems, for example, studies of aetiology, instances where a randomised controlled trial might be unethical, or if the condition to be studied is rare. Cohort studies are used to study incidence, causes, and prognosis ...

Longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies are two different types of research design. In a cross-sectional study you collect data from a population at a specific point in time; in a longitudinal study you repeatedly collect data from the same sample over an extended period of time. Longitudinal study.

The nested case-control study is a special situation in which cases and controls are both identified from within a cohort. ... Cohort and case-control study designs are not "opposites" as are prospective vs. retrospective, or cross-sectional vs. longitudinal, or controlled vs. uncontrolled research designs. Rather, like the randomized ...

Amber S Gordon. Beverly Claire Walters. Case-control (case-control, case-controlled) studies are beginning to appear more frequently in the neurosurgical literature. They can be more robust, if ...