Schizophrenia

Apr 14, 2013

780 likes | 1.54k Views

Schizophrenia. Features, Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Etiology, Treatment, Neurochemistry Jack Foust, MD Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Medical University of South Carolina. Features of Schizophrenia - Positive Symptoms. Hallucinations

Share Presentation

- moghaddam b et al

- hallucinations

- environmental influences

- less likely

- temporal lobe structures

- res brain res rev

Presentation Transcript

Schizophrenia • Features, Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Etiology, Treatment, Neurochemistry • Jack Foust, MD • Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences • Medical University of South Carolina

Features of Schizophrenia - Positive Symptoms • Hallucinations • Disorganized speech/thinking/behavior • Delusions

(from The Hour of the Wolf, directed by Ingmar Bergman)

Features of Schizophrenia - Negative Symptoms • Affective flattening • Alogia • Avolition • Anhedonia • Social Withdrawal

Features of Schizophrenia - Cognitive Deficits • Attention • Memory • Executive functions (organization, planning)

Schizophrenia - DSM Diagnostic Criterion “A” • Characteristic Sxs (2 + for 1 month) • delusions • hallucinations • disorganized speech • grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior • negative Sxs (flat affect, alogia, avolition) • (Only one element required if delusions bizarre, • or hallucinations commentary 2 voices conversing )

Schizophrenia - DSM Diagnostic Criteria B - F • Social/occupational dysfunction (decline) • Duration - 6 months total, 1 month “A” Sxs • Exclusion - SAFD, mood d/o • Exclusion - sub abuse, gen med condition • PDD/Autism - at least 1 month delusions or hallucinations

Schizophrenia - Comorbid Conditions • Depression • Anxiety • Aggression • Substance use disorder

Schizophrenia: Who is at Risk? • Lifetime prevalence • Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study: 1.3% • National Comorbidity Survey: 0.7% • Demographic characteristics • Age - typical onset late teens/early twenties • Gender - earlier age of onset among men • Marital status - less likely to be married

Schizophrenia: Who is at Risk? • Predisposing factors • Season of birth • Pregnancy and birth complications • Genetic background • Precipitating factors • Stress • Substance Abuse

“In addition to interfering with normal brain development, heavy marijuana use in adolescents may also lead to an earlier onset of schizophrenia in individuals who are genetically predisposed” Dr Sanjiv Kumra, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

“Carriers of the COMT valine158 allele were most likely to exhibit psychotic symptoms and to develop schizophreniform disorder if they used cannabis. Cannabis use had no such adverse influence on individuals with two copies of the methionine allele.” Caspi A, et al. Biological Psychiatry.2005; 57:1117-1127.

Genetic Risk Factors

Etiology: Neurodevelopmental Hypothesis • Possible insult during gestation, environmental influences • Disturbance in normal brain maturation • Reduced size medial temporal lobe structures - amygdala, hippocampus • Disturbed cytoarchitecture in hippocampus, entorhinal cortex

Treatment: Psychosocial Interventions • Supportive therapy • Behavioral family therapy • Family education • Social skills training • Community support • Lower relapse; improved functioning, compliance and social adjustment

Treatment: Antipsychotics • Used to treat psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, mania, psychotic depression • Include both “typicals” (Haldol) and “atypicals” (Clozaril, Risperdal)

Typical Antipsychotics • Chlopromazine (Thorazine) - prototype • Thioridazine (Mellaril) • Fluphenazine (Prolixin) • Haloperidol (Haldol)

Typical Antipsychotics: Drug/Receptor Effects • Antidopaminergic (D2) • Anticholinergic • Antihistaminic • Anti-alpha 1

Effects of Typical Antipsychotics • Four dopamine pathways • Mesocortical (negative symptoms) • Mesolimbic (positive symptoms) • Nigrostriatal (EPS, TD) • Tuberoinfundibular (hyperprolactinemia)

Guillin O and Laruelle M. Cellscience Reviews. 2005; 2:79-107

DA Receptor Distribution • D1- prefrontal cortex, striatum • D5 - hippocampus and entorhinal cortex • D2 – striatum, low concentration in medial temporal structures (hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, amygdala), thalamus, prefrontal cortex • D3 – striatum and ventral striatum • D4 - prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (have not been detected in the striatum)

Side Effects of Typical Neuroleptics • Extra-pyramidal syndrome (EPS) • Tardive dyskinesia (TD) • Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) • Prolactin elevation

Extra-Pyramidal Syndrome (EPS) • Acute dystonia • Akathesia • Muscle rigidity • Bradykinesia • Treatment – typically treated with anticholinergic compounds (Cogentin, Benadryl, Artane), Beta-blockers

Tardive Dyskinesia(TD) • 25-year continuous exposure risk: 68% in Yale Incidence Study • Annual incidence: 5% • Risk factors • Increased age • African-American race • Dose and duration of drug exposure • Early and severe EPS

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) • Potentially fatal complication of neuroleptic Tx • Temperature dysregulation: T >104°F/40°C • Muscle rigidity • Elevated CPK • Elevated WBC • Associated with TaqI A polymorphism in DRD2 • Tx: withdraw neuroleptics, cooling, dantrolene, bromocriptine (DA agonist)

Summary: Limitations of Typical Antipsychotics • Limited efficacy against negative symptoms • A substantial portion of patients (25% to 40%) respond poorly to treatment • EPS occurs at clinically effective doses • Side effects other than EPS (such as NMS) • Liable to cause tardive dyskinesia • Serum prolactin elevation

Advantages of Typical Antipsychotics • No blood monitoring • Efficacious for positive symptoms • Parenteral and depot preparations available • Low-cost

Antipsychotics: Atypical • Clozapine (Clozaril) - prototype • Risperidone (Risperdal) • Olanzepine (Zyprexa) • Quetiapine (Seroquel) • Ziprasidone (Geodon) • Aripiprazole (Abilify)

Atypical Antipsychotics: Clinical and Drug/Receptor Characteristics • Clinically display less EPS, more effective against negative symptoms, some improvement in cognition • Balanced D2/D1 antagonism • Strong 5HT2 antagonists

Serotonin-Dopamine Antagonists and TD: Hypothesized “Site-Specific” Neuromechanisms Psychosis EPS and TD Limbic Cortical Caudate/Putamen A10 A9 Ventral Tegmental Area Substantia Nigra Dopamine/5HT Antagonist Conventional Antipsychotic Agents

Atypical Antipsychotics

Antipsychotic Receptor Affinities • Haloperidol (Haldol)

Antipsychotic Receptor Affinities • Clozapine (Clozaril)

Antipsychotic Receptor Affinities • Risperidone (Risperdal)

Antipsychotic Receptor Affinities • Olanzepine (Zyprexa)

Antipsychotic Receptor Affinities • Quetiapine (Seroquel)

Ziprasidone (Geodon) • High affinity (antagonist) for D2, D3, 5HT2a, 5HT2c, 5HT1d • High affinity (agonist) for 5HT1a • Inhibits re-uptake of 5HT and NE • Moderate affinity for H1, α1 • Low affinity for D1, α2 • Negligible affinity for M1

Ziprasidone (Geodon), cont. • Positive symptoms improved (PANSS) • Negative symptoms improved (PANSS) • Depressive symptoms improved (MADRS) • Low EPS (5HT2a/D2, 5HT1a) • Low weight gain (H1) • Low sexual dysfunction • Minimal CYP450, CBC, LFT or CV effects (some QTc prolongation)

Neurotransmitter Systems Implicated in Schizophrenia Dopamine Acetylcholine Serotonin Norepinephrine GABA Neuropeptides Glutamate

Dopamine Hypothesis • Induction or worsening of psychotic symptoms with dopamine agonists • Amelioration of psychotic symptoms with antipsychotic drugs that are D2-receptor antagonists

Serotonin (5HT) Hypothesis • M-CPP (m-chlorophenylpiperazine) selective 5HT receptor agonist worsens psychotic symptoms • Pretreatment with ritanserin (5HT antagonist) attenuates psychotic symptoms

Glutamate Hypothesis • Psychotomimetic effects of phencyclidine (PCP), a potent N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) type glutamate receptor antagonist - mimics negative, positive and disorganization symptoms • Possible beneficial effects of cycloserine, glutamate receptor agonist

Glutamate, Dopamine, Ketamine • “Subanesthetic doses of ketamine, a noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist, impair prefrontal cortex (PFC) function in the rat and produce symptoms in humans similar to those observed in schizophrenia.” • “These findings suggest that ketamine may disrupt dopaminergic neurotransmission in the PFC as well as cognitive functions associated with this region, in part, by increasing the release of glutamate, thereby stimulating postsynaptic non-NMDA glutamate receptors.” Moghaddam B et al. J Neurosci 1997; 17: 2921-2927.

Aghajanian GK, Marek GJ. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2000; 31:302-312.

Neuronal Circuits in Schizophrenia • Thalamic nuclei relay sensory information to pyramidal neurons in limbic cortex and neocortex through glutaminergic excitatory afferents • Excessive response of pyramidal neurons is putative mechanism of psychosis (overstimulation) Freedman R. Schizophrenia. NEJM. 2003; 349:1738-1749.

- More by User

A group of severe disorders characterized by… disorganized and delusional thinking disturbed perceptions inappropriate emotions and behaviors. Schizophrenia. Often linked to the neurotransmitter dopamine. How Prevalent is Schizophrenia?.

3.29k views • 14 slides

Schizophrenia. Chapter 16. Schizophrenia. Fascinated and confounded healers for centuries One of most severe mental illnesses 1/3 of population 2.5% of direct costs of total budget $46 billion in indirect costs. History of Schizophrenia.

1.52k views • 55 slides

Schizophrenia. Tutorial (6/7/06) O.Arikawe. Definition: Splitting of psychic functions . Incidence : Low incidence but relatively high prevalence Annual incidence using current diagnostic criteria is 0.17 and 0.54 per 1000 population. Types. Acute and chronic

538 views • 16 slides

Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia: The Facts. Affects about .8% of Americans are afflicted Throughout the world over 24 million people suffer from this disease Strikes most commonly in early twenties Affects men and women equally “split mind”. 2. Symptoms of Schizophrenia.

379 views • 11 slides

Schizophrenia. Definition. Schizophrenia is a mental illness that effects the brain that makes the person view reality abnormally. This can consist of delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior. Types.

342 views • 7 slides

Schizophrenia. Chapter 11. Schizophrenia. Positive Symptoms: Type I Delusions Persecutory Delusions of Reference Grandiose Delusions. Schizophrenia. Hallucinations Disorganized Thoughts and Speech Disorganized or Catatonic Behavior http://www.wimp.com/schizophrenicsymptoms/.

372 views • 14 slides

Schizophrenia. By Garren Richardson. What is Schizophrenia?. Schizophrenia is a psychological disorder classified separately from other disorders because it is not easily categorized as an anxiety or mood disorder

379 views • 10 slides

Schizophrenia. The Unwell Brain. Disturbance in the Neurochemistry. The first discovery in the mid 1950s was that chronic usage of large daily doses of Amphetamines could produce a psychosis that was virtually indistinguishable from schizophrenia.

299 views • 12 slides

Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia. Two or more of the following, each present for a significant portion of the time during a 1-month period** Delusions Hallucinations Disorganized speech Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior Negative symptoms . Schizophrenia.

966 views • 20 slides

Schizophrenia. By Rebecca Stipp. History. Definition. a severe mental disorder characterized by some, but not necessarily all, of the following features: emotional blunting, intellectual deterioration, social isolation, disorganized speech and behavior, delusions, and hallucinations.

268 views • 10 slides

Schizophrenia. What is schizophrenia?. Most disabling and chronic of all mental illnesses Psychosis: type of mental illness- cannot distinguish reality from imagination Psychotic episodes Distorts: Thinking (may believe others are controlling their thoughts) Expression of emotions

296 views • 14 slides

Schizophrenia. Definition Psychotic disorder Thought Disorder Loose associations “Split” from reality NOT split or multiple personality. Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Positive Symptoms Loose associations Word salad Delusions Hallucinations Negative Symptoms Poverty of speech content

546 views • 24 slides

SCHIZOPHRENIA

SCHIZOPHRENIA. Andy Cortez Julian Cruz Period 05. Peter Green. He is the founder of Fleetwood Mac, a famous band He was diagnosed with schizophrenia in the mid 70’s Spent time in psychiatric hospitals and went through electroconvulsive therapy

349 views • 7 slides

Schizophrenia. Unfolding Case Study By Amanda Eymard , DNS, RN and Linda Manfrin-Ledet , DNS, APRN. Assigned Reading to be completed prior to case study. Prior to conducting this unfolding case study, students should read the following:

3.89k views • 82 slides

Schizophrenia. Lecture of 2-14-07. Symptoms. Psychosis Lack of touch with reality Delusions Erroneous beliefs Hallucinations False sensory perceptions Too much dopamine or not enough glutamate. Paranoid Schizophrenia. Delusions of grandeur Believe they are special with special powers

395 views • 22 slides

Schizophrenia. Stacy Zeigler. NIMH. Schizophrenia is a chronic, severe, and disabling brain disorder Affects 1.1% of the U.S. population age 18 and older in a given year.

755 views • 60 slides

Schizophrenia. A group of severe disorders characterized by disorganized and delusional thinking, disturbed perceptions, and inappropriate emotions and behaviours. Those with paranoid tendencies are particularly prone to delusions of persecution.

1.51k views • 7 slides

Schizophrenia. Lyudmyla T. Snovyda. Schizophrenia -.

996 views • 36 slides

Schizophrenia. www.psychlotron.org.uk. Schizophrenia is not a multiple personality A psychotic disorder involving a break with reality Many different manifestations with a few shared features. Schizophrenia diagnosis. Positive Symptoms:

856 views • 24 slides

Schizophrenia. Tiffany Becker Denise Keown Heather Baltz. Overview of Schizophrenia. What is schizophrenia? Schizophrenia behaviors Does schizophrenia affect the brain? What causes schizophrenia? Who gets schizophrenia? Early Onset Schizophrenia Schizophrenia Facts.

1.09k views • 37 slides

Rochelle Blumenstock. Schizophrenia. Etiology. Genetics 10% chance of developing the disorder if you have an immediate relative with it 40-65% chance of both twins being diagnosed with the disorder No single gene associated Many rare genetic mutations . Environment

346 views • 17 slides

schizophrenia

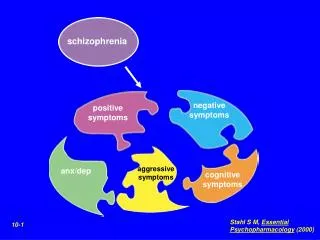

schizophrenia. negative symptoms. positive symptoms. aggressive symptoms. anx/dep. cognitive symptoms. Stahl S M, Essential Psychopharmacology (2000). 10-1. Positive Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Stahl S M, Essential Psychopharmacology (2000). 10-20.

648 views • 14 slides

Module 11: Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

Case studies: schizophrenia spectrum disorders, learning objectives.

- Identify schizophrenia and psychotic disorders in case studies

Case Study: Bryant

Thirty-five-year-old Bryant was admitted to the hospital because of ritualistic behaviors, depression, and distrust. At the time of admission, prominent ritualistic behaviors and depression misled clinicians to diagnose Bryant with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Shortly after, psychotic symptoms such as disorganized thoughts and delusion of control were noticeable. He told the doctors he has not been receiving any treatment, was not on any substance or medication, and has been experiencing these symptoms for about two weeks. Throughout the course of his treatment, the doctors noticed that he developed a catatonic stupor and a respiratory infection, which was identified by respiratory symptoms, blood tests, and a chest X-ray. To treat the psychotic symptoms, catatonic stupor, and respiratory infection, risperidone, MECT, and ceftriaxone (antibiotic) were administered, and these therapies proved to be dramatically effective. [1]

Case Study: Shanta

Shanta, a 28-year-old female with no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, was sent to the local emergency room after her parents called 911; they were concerned that their daughter had become uncharacteristically irritable and paranoid. The family observed that she had stopped interacting with them and had been spending long periods of time alone in her bedroom. For over a month, she had not attended school at the local community college. Her parents finally made the decision to call the police when she started to threaten them with a knife, and the police took her to the local emergency room for a crisis evaluation.

Following the administration of the medication, she tried to escape from the emergency room, contending that the hospital staff was planning to kill her. She eventually slept and when she awoke, she told the crisis worker that she had been diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) a month ago. At the time of this ADHD diagnosis, she was started on 30 mg of a stimulant to be taken every morning in order to help her focus and become less stressed over the possibility of poor school performance.

After two weeks, the provider increased her dosage to 60 mg every morning and also started her on dextroamphetamine sulfate tablets (10 mg) that she took daily in the afternoon in order to improve her concentration and ability to study. Shanta claimed that she might have taken up to three dextroamphetamine sulfate tablets over the past three days because she was worried about falling asleep and being unable to adequately prepare for an examination.

Prior to the ADHD diagnosis, the patient had no known psychiatric or substance abuse history. The urine toxicology screen taken upon admission to the emergency department was positive only for amphetamines. There was no family history of psychotic or mood disorders, and she didn’t exhibit any depressive, manic, or hypomanic symptoms.

The stimulant medications were discontinued by the hospital upon admission to the emergency department and the patient was treated with an atypical antipsychotic. She tolerated the medications well, started psychotherapy sessions, and was released five days later. On the day of discharge, there were no delusions or hallucinations reported. She was referred to the local mental health center for aftercare follow-up with a psychiatrist. [2]

Another powerful case study example is that of Elyn R. Saks, the associate dean and Orrin B. Evans professor of law, psychology, and psychiatry and the behavioral sciences at the University of Southern California Gould Law School.

Saks began experiencing symptoms of mental illness at eight years old, but she had her first full-blown episode when studying as a Marshall scholar at Oxford University. Another breakdown happened while Saks was a student at Yale Law School, after which she “ended up forcibly restrained and forced to take anti-psychotic medication.” Her scholarly efforts thus include taking a careful look at the destructive impact force and coercion can have on the lives of people with psychiatric illnesses, whether during treatment or perhaps in interactions with police; the Saks Institute, for example, co-hosted a conference examining the urgent problem of how to address excessive use of force in encounters between law enforcement and individuals with mental health challenges.

Saks lives with schizophrenia and has written and spoken about her experiences. She says, “There’s a tremendous need to implode the myths of mental illness, to put a face on it, to show people that a diagnosis does not have to lead to a painful and oblique life.”

In recent years, researchers have begun talking about mental health care in the same way addiction specialists speak of recovery—the lifelong journey of self-treatment and discipline that guides substance abuse programs. The idea remains controversial: managing a severe mental illness is more complicated than simply avoiding certain behaviors. Approaches include “medication (usually), therapy (often), a measure of good luck (always)—and, most of all, the inner strength to manage one’s demons, if not banish them. That strength can come from any number of places…love, forgiveness, faith in God, a lifelong friendship.” Saks says, “We who struggle with these disorders can lead full, happy, productive lives, if we have the right resources.”

You can view the transcript for “A tale of mental illness | Elyn Saks” here (opens in new window) .

- Bai, Y., Yang, X., Zeng, Z., & Yang, H. (2018). A case report of schizoaffective disorder with ritualistic behaviors and catatonic stupor: successful treatment by risperidone and modified electroconvulsive therapy. BMC psychiatry , 18(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1655-5 ↵

- Henning A, Kurtom M, Espiridion E D (February 23, 2019) A Case Study of Acute Stimulant-induced Psychosis. Cureus 11(2): e4126. doi:10.7759/cureus.4126 ↵

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by : Wallis Back for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- A tale of mental illness . Authored by : Elyn Saks. Provided by : TED. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f6CILJA110Y . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- A Case Study of Acute Stimulant-induced Psychosis. Authored by : Ashley Henning, Muhannad Kurtom, Eduardo D. Espiridion. Provided by : Cureus. Located at : https://www.cureus.com/articles/17024-a-case-study-of-acute-stimulant-induced-psychosis#article-disclosures-acknowledgements . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Elyn Saks. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elyn_Saks . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- A case report of schizoaffective disorder with ritualistic behaviors and catatonic stupor: successful treatment by risperidone and modified electroconvulsive therapy. Authored by : Yuanhan Bai, Xi Yang, Zhiqiang Zeng, and Haichen Yangcorresponding. Located at : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5851085/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Family Med Prim Care

- v.7(6); Nov-Dec 2018

Very early-onset psychosis/schizophrenia: Case studies of spectrum of presentation and management issues

Jitender aneja.

1 Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

Kartik Singhai

Karandeep paul.

Schizophrenia occurs very uncommonly in children younger than 13 years. The disease is preceded by premorbid difficulties, familial vulnerability, and a prodromal phase. The occurrence of positive psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations depends on the level of cognitive development of child. Furthermore, at times it is very difficult to differentiate the psychopathology and sustain a diagnosis of schizophrenia in view of similarities with disorders such as autism, mood disorders, and obsessive compulsive disorders. Here, we present three case studies with varying presentation of childhood-onset psychosis/schizophrenia and associated management issues.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic severe mental illness with heterogeneous clinical profile and debilitating course. Research shows that clinical features, severity of illness, prognosis, and treatment of schizophrenia vary depending on the age of onset of illness.[ 1 , 2 ] Hence, age-specific research in schizophrenia has been emphasized. Although consistency has been noted in differentiating early-onset psychosis (onset <18 years of age) and adult-onset psychosis (onset >18 years), considerable variation is observed with regard to the age of childhood-onset schizophrenia or very early-onset psychosis/schizophrenia (VEOP/VEOS).[ 2 , 3 ] Most commonly, psychosis occurring at <13 years of age has been considered to be of very early onset and that between 13 and 17 years to be of adolescent onset.[ 4 ] Furthermore, VEOS has been considered to be rare and shown to have differing clinical features (including positive and negative symptoms, cognitive decline, and neuroimaging findings), course, and outcome when compared with that of early-onset or adult-onset schizophrenia.[ 3 ] Progress in acknowledgement of psychotic disorders in children in the recent times has led primary care physicians and paediatricians to increasingly serve as the principal identifiers of psychiatrically ill youth. In recent years, there has been substantial research in early intervention efforts (e.g., with psychotherapy or antipsychotic medicines) focused on the early stages of schizophrenia and on young people with prodromal symptoms.[ 5 ] Here, we report a series of cases with very early onset of psychosis/schizophrenia who had varying clinical features and associated management issues.

Case Reports

A 14-year-old boy, educated up to class 6, belonging to a family of middle socioeconomic status and residing in an urban area was brought with complaints of academic decline since 3 years and hearing voices for the past 2 years. The child was born out of a nonconsanguineous marriage, an unplanned, uneventful, but wanted pregnancy. The child attained developmental milestones as per age. From his early childhood, he was exposed to aggressive behavior of his father, who often attempted to discipline him and in this pursuit at times was abusive and aggressive toward him. Marital problems and domestic violence since marriage lead to divorce of parents when the child attained age of 10 years.

The following year, the child and the mother moved to maternal grandparents’ home and his school was also changed. Within a year of this, a decline in his academic performance with handwriting deterioration, and irritable and sad behaviour was noted. Complaints from school were often received by the mother where the child was found engaged in fist fights and undesirable behavior. He also preferred solitary activities and resented to eat with the rest of the family. In addition, a decline in performance of daily routine activities was seen. No history suggestive of depressive cognitions at that time was forthcoming. A private psychiatrist was consulted who treated him with sodium valproate up to 400 mg/day for nearly 2 months which led to a decline in his irritability and aggression. But the diagnosis was deferred and the medications were gradually tapered and stopped. Over the next 1 year, he also started hearing voices that fulfilled dimensions of commanding type of auditory hallucinations. He suspected that family members including his mother collude with the unknown persons, whose voices he heard and believed it was done to tease him. He eventually dropped out of school and was often found awake till late night, seen muttering to self, shouting at persons who were not around with further deterioration in his socialization and self-care. Another psychiatrist was consulted and he was now diagnosed with schizophrenia and treated inpatient for 2 weeks with risperidone 3 mg, olanzapine 2.5 mg, and oxcarbazepine 300 mg/day with some improvement in his symptoms. Significant weight gain with the medication lead to poor compliance which further led to relapse within 3 months of discharge. Frequent aggressive episodes over the next 1 year resulted in multiple hospital admissions. He was brought to us with acute exacerbation of symptoms and was receiving divalproex sodium 1500 mg/day, aripiprazole 30 mg/day, trifluperazine 15 mg/day, olanzapine 20 mg/day, and lorazepam injection as and when required. He was admitted for diagnostic clarification and rationalization of his medications. He had remarkable physical features of elongated face with large ears. Non-cooperation for mental state examination, and aggressive and violent behavior were noted. He was observed to be muttering and laughing to self. His mood was irritable, speech was laconic, and he lacked insight into his illness. We entertained a diagnosis of very early-onset schizophrenia and explored for the possibilities of organic psychosis, autoimmune encephalitis, and Fragile X syndrome. The physical investigations done are shown in Table 1 . Further special investigations in the form of rubella antibodies (serum IgG = 64.12 U/mL, IgM = 2.44 U/mL) and polymerase chain reaction for Fragile X syndrome (repeat size = 24) were normal. His intelligence quotient measured a year ago was 90, but he did not cooperate for the same during present admission. Initially, we reduced the medication and only kept him on aripiprazole 30 mg/day and added lurasidone 40 mg twice a day and discharged him with residual negative symptoms only. However, his hallucinations and aggression reappeared within 2 weeks of discharge and was readmitted. This time eight sessions of bilateral modified electroconvulsive therapy were administered and he was put on aripiprazole 30 mg/day, chlorpromazine 600 mg/day, sodium divalproex 1000 mg/day, and trihexyphenidyl 4 mg/day. The family was psychoeducated about the illness, and mother's expressed emotions and overinvolvement was addressed by supportive psychotherapy. Moreover, an activity schedule for the child was made, and occupational therapy was instituted. Dietary modifications in view of weight gain were also suggested. In the past 6 months, no episodes of violence came to our notice, though irritability on not meeting his demands is persistent. However, poor socialization, lack of motivation, apathy, weight gain subsequent to psychotropic medications, and aversion to start school are still unresolved. Influence of his multiple medications on bone marrow function is an impending issue of concern.

Details of investigations done in the three children

An 11-year-old boy, educated up to class 3, belonging to a rural family of lower socioeconomic status was brought with complaints of academic decline since 2 years, repetition of acts, irritability since a year, and adoption of abnormal postures since 6 months. He was born out of a nonconsanguineous marriage, uneventful birth, and pregnancy. He was third in birth order and achieved developmental milestones at an appropriate age. Since 2 years, he would not attend to his studies, had poor attention, and difficult memorization. He attributed it to lack of friends at school and asked for school change. There was no history of low mood, depressive cognitions, conduct problems, or bullying and he performed his daily routine like his premorbid self at that time. Since a year, he was observed to repeat certain acts such as pacing in the room from one end to another, continuously for up to 1–2 h, with intermittent stops and often insisted his mother to follow the suit, stand nearby him, or else he would clang on her. He prohibited other family members except his mother near him and would accept his meals only from her. He repeatedly sought assurance of his mother if he had spoken everything right. He also washed his hands repeatedly, up to 10–20 times at one time, and was unable to elaborate reason for the same. His mood during that period was largely irritable with no sadness or fearfulness. He mostly wore the same set of clothes, would be forced to take bath or get nails/hair trimmed, and efforts to these were often met with aggression from the patient. Eventually, he stopped going to school and his family sought faith healing. Within the next 5–6 months, his illness worsened. Fixed gaze, reduced eye blinking, smiling out of context, diminished speech, and refusal to eat food were the reasons for which he was brought to us. His physical examination was unremarkable and his mental state examination using the Kirby's method showed an untidy and ill-kempt child, with infrequent spontaneous acts, and occasional resentment for examination. He had an expressionless face, with occasional smiling to self, negativism, and mutism. No rigidity in any of the limb was observed. He was diagnosed with catatonic schizophrenia and probable obsessive compulsive disorder (vs mannerisms). We performed a battery of physical investigation to rule out organic psychosis [ Table 1 ]. He responded to injection lorazepam with which catatonia melted away. He was also prescribed olanzapine up to 15 mg/day, fluoxetine 20 mg/day, and dietary modification and lactulose for constipation. The family left against medical advice with 50%–60% clinical improvement [rating on Bush Francis Catatonia Rating scale (BFCRS) reduced from 10 to 4]. He relapsed within a month of discharge, initially with predominance of the probable obsessive compulsive symptoms. Fluoxetine was further increased to up to 60 mg/day. But within the next 2 months, the catatonic symptoms reappeared and he was readmitted. He had received olanzapine up to 25 mg/day, which was replaced with risperidone. In view of nonresponse to intravenous lorazepam, we administered him five sessions of modified bilateral Electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) (rating on BFCRS reduced from 8 to 0). The family was psychoeducated about the child's illness and the need for continuous treatment was emphasized. He was discharged with up to 80%–90% improvement. At follow-ups, he started participating at farm work of the family, took care of self, with some repetition of acts such as washing of hands, and denied any associated anxiety symptoms. However, efforts to re-enroll in school had been futile as the child did not agree for it. He has been maintaining at the same level since 6 months of discharge.

A 7-year-old girl, student of second class, belonging to a high socioeconomic status family living in an urban locality was brought with complaints of academic decline, irritability, and abnormal behavior for the past 9 months. The child was born out of a nonconsanguineous marriage, is first in order, and was a wanted child. Maternal health during pregnancy was normal, but the period of labor was prolonged beyond 18 h, so a lower segment caesarean section was performed. There was no history of birth-related complications and the child's birth weight was 2.80 kg. The child attained developmental milestones as per age. The child had a temperament characterized by high activity levels, below average threshold of distractibility, average ability to sustain attention and persist, easy to warm up, adaptation to new situations, and regular bowel and bladder habits. She was enrolled in school at the age of 4 years and progressed well till 9 months back when a decline in her academic interest was observed by her class teacher. Deterioration of her handwriting skills and avoidance of group activities in school were observed. Similarly, at home persistent irritable behavior was seen and her play activities with her siblings reduced. However, her biofunctions were normal during this period.

One month prior to visiting us, she started insisting on wearing the same dress. She wore the same colored or at times the same dress which she would not take off even at bed or bath time. In addition, a change in her mood from largely irritable to cheerful was noted. Her activity levels were increased and it would be difficult to make her sit quietly in class. Her speech output was more than her usual self and she talked incessantly. Her sleep duration also decreased and she started getting up 3–4 h earlier than her usual routine. In view of these symptoms, her family made first contact with us. Her physical examination was normal and mental state examination revealed her to be cheerful, overactive, and difficult to interrupt. She sang and danced during the interview. We diagnosed her with acute mania on the basis of clinical evaluation and assessment on MINI Kid 6.0.[ 6 ] The details of her physical examination are depicted in Table 1 . She was initially treated with olanzapine 5 mg/day which was later on increased to 10 mg/day. However, no response was observed with it in the next 2 weeks, so it was cross tapered with sodium valproate which was built up to 400 mg/day. She improved by nearly 50%, but her mood still remained cheerful/irritable. She did not resume her school and was brought irregularly for the follow-up. Within the next 2 months, she also started muttering to herself and made certain abnormal gestures. She often feared staying alone, or while going to bed insisted the lights to be kept on and ask someone to accompany her in the toilet unlike her previous self. When asked, she reported seeing a lady in white clothes, with no other details. She stopped asking for food on her own and remained lost in her fantasy world. However, her interest in dressing and appreciating herself in mirror persisted. Her mood during this period was mostly labile and often changed from cheerful to sad or irritable. As per the family, the medications were continued as advised. So in view of the emerging picture, the diagnosis was revised to schizo-affective disorder, and in addition to hike in dose of sodium valproate to 500 mg/day, risperidone 2 mg/day was also added. However, even after 8 weeks of treatment with this combination with hike of risperidone to 4 mg/day, there was no relief. The child is still symptomatic, does not go to school, and has significant dysfunction. Psychosocial intervention in the form of psychoeducation, activity scheduling for the child, and occupational therapy has been instituted in addition to the existing treatment regimen, but results are yet to be seen.

The older concept of neurodegenerative etiology of schizophrenia has been superseded by evolving neurodevelopmental nature of this disease. The latter has been attributed to initiation of the underlying pathophysiological processes long before the onset of clinical disease and interaction of the various genetic and environmental factors. The more accommodating theorist propose schizophrenia to be of neurodevelopmental in origin which in turn speeds the process of neurodegeneration.

On clinical front, VEOS is associated with a more insidious onset, prominent negative symptoms, auditory hallucinations, poorly formed delusions which is in part due to less developed cognitive abilities.[ 7 ] The presence of history of speech and language delay as well as motor development deficits have been observed in major studies on childhood-onset schizophrenia, be it the Maudsley early-onset schizophrenia project or the NIMH study.[ 8 , 9 ] Premorbid deficits in social adjustments and presence of autistic symptoms have also been shown. Moreover, the early onset of psychosis is associated with poor prognosis, worse overall functioning, and multiple hospitalizations.[ 7 ] The duration of untreated psychosis in childhood-onset psychosis has been shown to be smaller in hospital-based studies[ 10 ] and larger in community settings.[ 11 ] In addition, the presence of comorbidities and an organic etiology or history of maternal illness during pregnancy is a common finding in VEOS.[ 10 ] In addition, obsessive compulsive symptoms are frequently observed in first-episode drug-naive schizophrenia patients and have a poorer outcome, more severe impairment of social behavior, and lower functioning.[ 12 ] However, in many instances it is very difficult to differentiate the obsessive compulsive symptoms from the motor symptoms of schizophrenia such as stereotypy and mannerisms and varying degree of insight.[ 13 ]

In the present case series, all the children had an insidious onset of illness, with initial symptom of academic decline, and poorly formed psychotic symptoms/psychotic-like experiences. All the children reported here had dropped out of school, showed a shift in their interests, withdrew from social circle, appeared to be distant, had impaired self-care, and often lacked concern for others along with a range of mood disturbances. All these symptoms fit into the classical description of prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia.[ 14 ] In contrast to available evidence, no history of motor, speech, or language delay was noted in any of the child. Furthermore, no history suggestive of autistic features or problems in social adjustments prior to onset of illness was forthcoming.

However, the diagnosis of schizophrenia could be clearly made in the first case, while the second child had predominant catatonic and probably obsessive compulsive symptoms. It is difficult to ascertain the diagnosis of schizophrenia on the basis of presence of only catatonic symptoms and no delusions and hallucinations or negative symptoms as required by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision. However, it is very difficult to sustain any other diagnosis for the second child. In the third child, the illness has been evolving and the clinical picture changed from predominant mood symptoms to psychotic-like experiences at later stage. Therefore, at present a diagnosis of schizo-affective disorder is entertained. We could not find any possible organic etiology in any of the three cases with the best of our efforts.

With provision of pharmacological and psychosocial treatment in accordance to the available treatment guidelines,[ 15 ] remission was not achieved in two of the three children. Currently, the available evidence also suggests that the prognosis of childhood-onset schizophrenia is mainly poor as it disrupts the social and cognitive development and thus nearly two-third of children do not achieve remission.[ 16 ] On a positive note, we have been able to retain all the children in treatment.

Other issues faced by the families of three children and the treating team are briefly discussed below. In countries like India, where significant expenses are born by patients/family, associated stigma, limited social services, and the anti-psychotic related adverse effects raise the burden of care exponentially. In 2/3 index patients, the family bore the costs of special investigations, which was not possible in the second child and led to financial difficulties for the single mother of the first child. Adding on, the availability of rehabilitation services for children with major mental illnesses is scarce in various parts of our country. Furthermore, we successfully used ECT for management of acute disturbance in two of the three patients prior to the notification of Mental Health Care Act, 2017 that prohibits its use in minors. The case series also put forward a strong case for strengthening and sensitizing primary care physicians and pediatricians in identifying and treating cases of VEOP, since they are more likely to be the first points of contact with patients of the discussed age group. In view of the duration of untreated psychosis being a very eloquent prognostic factor for VEOP and the symptomatology of the same showing significant heterogeneity, armoring primary care physicians and pediatricians with the right skills to identify, treat, or refer patients with VEOP, especially in the prodromal period, might profoundly contribute in decreasing the morbidity and improving prognosis. Citing this lacuna which could be filled and used to our advantage, Stevens et al .[ 17 ] elaborated and discussed various questions which practitioners might find useful.

Childhood-onset schizophrenia is a rare occurrence. The current case series highlights differing clinical presentation of VEOS/VEOP in children and adolescents. Certain other issues pertinent to the management of VEOS/VEOP are also touched upon in this article. With the early recognition of childhood mental health illnesses, we need to build and strengthen ample child and adolescent mental health services in India.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Sonam Arora, MD, DNB (Pathology), for providing assistance in laboratory investigations and article writing.

- 3D Brain Atlas

- Alzheimer’s

- Schizophrenia

- Parkinson’s

Schizophrenia – Neurobiology and Aetiology

This presentation covers aetiology of Schizophrenia.

A working knowledge of the normal structure and function of the nervous system is key to understanding psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia. This slide deck presents an introduction to neuroanatomy, the key components of neurosynaptic transmission, neurotransmitters and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Last, it includes a discussion of some underlying causes of schizophrenia, such as genetic and environmental factors.

This slide deck has been developed in collaboration with the former Lundbeck International Neuroscience Foundation.

Index for slide deck

Neurobiology and aetiology, introduction to neuroanatomy, organisation of the nervous system.

To understand psychiatric disorders, it is important to have a working understanding of the normal structure and function of the nervous system. The central nervous system (CNS; brain, spinal cord) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) are made up of neurones and glial cell…

The neurone constitutes the functional unit of the nervous system; there are over 100 billion neurones in the brain. [Purves et al., 2008; Martin, 2003; Kandel et al., 2000] Each neurone has the ability to interact with and influence many other cells, which creates a syste…

Anatomical regions of the brain

The brain is divided into four anatomical regions: the diencephalon, brainstem, cerebrum, and cerebellum, as described on the slide. [Kandel et al., 2000; Tortora & Derrickson, 2009]

References: Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM (eds). Principles of Neural Science. 4th e…

The cerebral cortex is the main functional unit of the cerebrum. [Tortora & Derrickson, 2009] The three main functional areas of the cerebral cortex are: [Tortora & Derrickson, 2009; Prise & Wilson, 2003]

- motor areas that control voluntary movement (primary, secondary, an…

Lobes of the brain

The brain can be thought of as comprising five ‘lobes’ – the four lobes of the cerebral cortex and a fifth lobe, the insula, deep within the brain, as shown on the slide. [Martin, 2003; Tortora & Derrickson, 2009; Price & Wilson, 2003] The lobes of the cerebral cortex are …

Neurosynaptic transmission

Neurotransmission.

Information moves through the nervous system via two integrated forms of communication – electrical neurotransmission and chemical neurotransmission, as shown on the slide. [Kandel et al., 2000] An action potential is generated at the origin of the axon following sufficien…

The synapse

Neurones do not physically touch one another; two neurones are separated by a gap, known as a synaptic cleft. [Kandel et al., 2000] Because neurones do not touch, and an action potential cannot ‘jump’ across a synaptic cleft, the signal must be converted to a chemical sign…

Process of chemical neurotransmission

The idea that neurotransmission occurs at synapses and is mediated by chemicals was, at first, a contentious issue. [Purves et al., 2008] It was in the first half of the 1900s that experiments proved chemical neurotransmission occurred. [Purves et al., 2008] The process is …

Related content

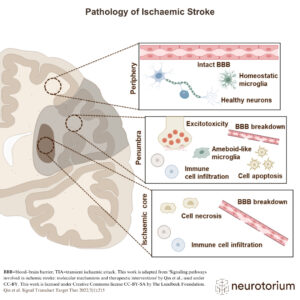

The pathology of ischaemic stroke is complex, but commonly involves the formation of a clot that travels in the blood to or within the brain and becomes lodged in the blood vessels of the brain (a thromboembolism), which can reduce or block blood flow (an occlusion).

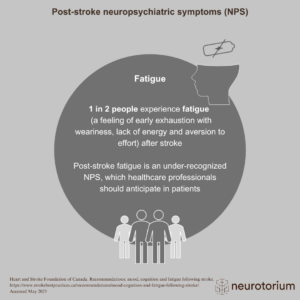

Post-stroke fatigue is an under-recognized NPS, which healthcare professionals should anticipate in patients.

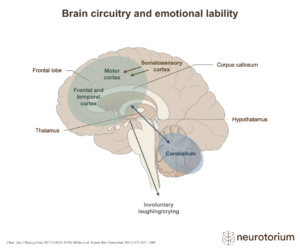

Emotional lability describes episodes of involuntary and uncontrollable crying and/or laughing, outside of socially appropriate circumstances and when it is incongruent with the patient’s emotional state.

-300x169.jpg)

Permissions

Permissions for creative use of the resources from neurotorium.

Permission is granted to download images, slides and videos and use them in your own presentations, provided that copyright notices and the Neurotorium logo are not hidden or removed. For use in publications and on websites, proper attribution must be provided together with a link to Neurotorium.org

Your slides will download now. Do you want to get our latest information?

Sign up to our newsletter and receive news in your inbox. We send newsletters every 1-2 months.

You have been subscribed to our newsletter!

Share or print.

Share content with anyone.

Save to workspace

Select language.

We have detected that you are from “France”. You have the option of switching the language to French, if you would prefer that?.

This site uses cookies

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Sign up for our newsletter

Fill in you information below and stay up to date with the latest content on Neurotorium.

We publish newsletters every 2-3 months, keeping you up to date with the latest content on the website. You will receive a welcome e-mail immediately after you sign up for our newsletter. If you do not receive an e-mail, please check your spam folder. Contact support at [email protected] if you require help.

Welcome back

Please enter your details below.

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- March 15, 2024 | VOL. 77, NO. 1 CURRENT ISSUE pp.1-42

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Metacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy for Schizophrenia: Case Study of a Patient With a Co-Occurring Substance Use Disorder

- Alison V. James , Psy.D. ,

- Bethany L. Leonhardt , Psy.D. ,

- Kelly D. Buck , CNS

Search for more papers by this author

Decrements in metacognitive functioning, or the ability to form complex and integrated representations of oneself and others, have been identified as a core feature of schizophrenia. These deficits have been observed to be largely independent of the severity of psychopathology and neurocognitive functioning and are linked to poor outcomes for those with the disorder. This study is a case illustration of the efficacy of metacognitive reflection and insight therapy (MERIT) in increasing the metacognitive capacity of an individual diagnosed as having co-occurring schizophrenia and a substance use disorder during three years of individual therapy. The eight elements of MERIT, which promote metacognitive growth, are presented as they apply to the present case. Case conceptualization, outcomes, and prognosis are also presented. These eight elements enabled the patient to move from a state of gross disorganization—unable to identify his thoughts or present them in a linear fashion—to one in which he was able to develop increasingly complex ideas about himself and others and integrate this understanding into a richer sense of himself, of his psychological challenges, and of the role that substance use played in his life. Results of the study also illustrate the foundational necessity of self-reflectivity in order to facilitate understanding of the mind of others and the relationship between psychological pain and the emergence of disorganization.

Metacognition refers to a spectrum of mental activities that range from discrete acts, such as thinking about one’s own thinking or contemplating the mental activity of others, to an increasingly more complex synthesis of these abilities into an integrated sense of oneself and others ( 1 , 2 ). The absence of these abilities results in difficulties with appropriately responding to psychosocial challenges and, therefore, hinders recovery. Although some researchers consider metacognition to be a component of social cognition ( 3 ), metacognition differs from social cognition in that it is not concerned with the accuracy of one’s emotional or social judgments. Instead, it focuses on how this information is integrated into a more complex understanding of oneself and others. This distinction between social cognition and metacognition as conceptually different factors has been illustrated in previous studies using principal-components analyses ( 4 ).

Deficits in metacognitive capacity among those with schizophrenia have been recognized and observed for more than two decades and are considered to be a stable and key feature that underlies symptoms of the disorder ( 5 ). Intact metacognitive functioning has been found to be associated with psychosocial outcomes, including higher work performance ( 6 ) and intrinsic motivation and learning ( 7 ). Decrements in metacognitive function, in contrast, have been linked to poorer functioning and outcomes ( 8 ). Although metacognition is correlated with severity of psychopathology, previous research suggests that deficits in metacognition cannot solely be explained as reflections of symptoms or features of the disorder ( 9 , 10 ).

Given the identification of metacognitive deficits as a core feature of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, novel interventions that target rebuilding atrophied metacognitive capacities are of paramount importance ( 11 ). One such integrative intervention is metacognitive reflection and insight therapy (MERIT) ( 12 ). MERIT is an integrative treatment that seeks to promote synthetic metacognitive capacity and was developed to target deficits in the four elements of metacognition among individuals with psychotic disorders.

Although MERIT is a manual-based intervention, it does not follow a prescribed treatment protocol. It is instead a flexible and target-driven approach whereby therapists and patients think together, and patients are encouraged to reflect on their ideas of themselves and others. Metacognitive ability is operationalized as a hierarchical capacity within MERIT, with each level of functioning building on the abilities needed for the previous level. As such, interventions within this framework should be tailored to the patient’s current metacognitive capacity and aim to facilitate metacognitive growth toward increasingly complex and integrative metacognitive acts.

MERIT consists of eight interrelated therapeutic elements that should be present in each session. These include attending to the client’s agenda, including the therapist’s thoughts as part of a dialogue, eliciting narrative episodes, defining a psychological problem, discussing interpersonal processes within the session, evaluating progress, stimulating reflective acts about oneself and others, and stimulating the use of knowledge about oneself and others to respond to psychological problems. These elements are each discussed below in the context of the case presented.

Several previous case studies ( 13 – 15 ) have demonstrated the efficacy of MERIT in assisting individuals with schizophrenia with forming more complex ideas about their own mental states and the mental states of others. In addition, MERIT has been shown to help individuals synthesize that information into an integrated sense of themselves and others. These case studies have evaluated patients in both early and later phases of their illness and have included individuals with a range of clinical presentations.

One limitation of the case work to date is a lack of inclusion of clinical cases of individuals presenting with co-occurring substance use disorders. Epidemiological data have shown that approximately 40% to 50% of individuals with schizophrenia also have a substance use disorder ( 16 ). Moreover, substance use disorders among this population are associated with poor outcomes, including poor response to treatment, hospitalization, suicide, and homelessness ( 17 ).

It, therefore, seems especially important to consider this group, given that integrative psychotherapy interventions may reduce the risk of these poor outcomes. People with schizophrenia and co-occurring substance use disorder also appear to possess low levels of metacognition and lower levels of metacognitive mastery, which enables individuals to identify a psychological problem and use their knowledge about themselves to appropriately respond to that problem. Therefore, the current article presents a comprehensive case study of the application of MERIT in the treatment of an individual diagnosed as having co-occurring schizophrenia and substance use disorder.

Case Illustration

Presenting problem and client description.

We refer to the client for this case as Dylan. We have modified details of this case report, such as name and other identifying information, to protect his confidentiality while preserving the illustrative value of the case. Dylan was a Caucasian man in his late 40s who lived in a rural midwestern town with his older brother. He was single and had never married, and he did not have any children.

Dylan’s parents divorced when he was four years old, and he was the youngest of three children. At the time of this therapy, his mother and brother lived in the same state as Dylan, and his father lived in a neighboring state. His eldest brother died approximately 10 years prior from a drug overdose. It was not clear whether there was a history of schizophrenia in Dylan’s family; however, he described instances of his mother’s disorganized behavior, including examples of times when she apparently shouted at someone who was not there and other occasions when she discussed her unusual beliefs with Dylan. He also endorsed a family history significant for alcoholism.

Dylan described a chaotic and conflict-ridden household prior to his parents’ divorce; his father was often drunk and volatile, and his parents frequently fought. After his parents’ divorce, Dylan and his older siblings were raised by his mother. He described a nomadic childhood characterized by poor living conditions. He and his siblings moved to a new home every few years, first moving within the state and then ultimately settling in the southeastern United States.

Largely absent during his childhood and young adulthood were close connections with others, both outside the family (as a result of his frequent moves) as well as within the family in his relationships with his siblings and mother. At the age of 16, frustrated by his mother’s increasingly erratic and disorganized behavior, Dylan decided to hitchhike back home to the Midwest, where he completed high school while living with his uncle. After high school, he worked odd jobs at home before joining the military.

Dylan was diagnosed with schizophrenia in his early 20s, two years into his military career and in the wake of a recent rejection by a woman he was dating. Dylan reported that at this time his drinking and social isolation significantly increased. He was admitted to the hospital by his commander after displaying strange and disorganized behavior and speech, and he remained in the hospital for approximately six months, after which he was discharged from the military.

After his discharge, Dylan moved back to the Midwest to live with his mother in an environment similar to that of his nomadic formative years. During this time, Dylan’s drinking continued to escalate, which he attributed to the stress of living with his mother. His drinking culminated in a citation for driving under the influence of alcohol and a short jail stay, during which his disorganized behavior also briefly intensified.

Ultimately, Dylan chose to move back to his home state to live with his brother, first in a series of trailer homes and later in a home Dylan purchased in a rural town. Over the next several years, his drinking persisted. Coupled with his limited insight and difficulties connecting with others, his alcohol use led Dylan to surround himself with and take in as roommates people who also abused substances. This pattern of behavior ultimately led to a drug-related arrest two years prior to the start of psychotherapy with this provider (AJ).

At the start of psychotherapy, Dylan had been clinically stable with his medication-management regimen for several years. He was serving probation for his drug charge, for which he was required to participate in group psychotherapy and 12-step programming. Prior to psychotherapy with this provider, Dylan had previously participated in individual therapy for a period of one year, but he demonstrated limited engagement in the therapeutic relationship and his treatment.

When Dylan started therapy, he demonstrated significant disorganization of his thoughts and speech and possessed a fragmented account of the narrative events of his psychosocial history. He described hearing voices and seeing strange figures, and he possessed vague delusional beliefs about the government and religion. Dylan also presented with profoundly flat affect, and his sporadic emotional expressions were frequently incongruent with the subject matter being discussed. With regard to his substance use, he demonstrated some awareness that his past drug and alcohol use had caused problems for him, but he lacked an understanding of the factors precipitating his use. Similarly, Dylan’s descriptions of past use contained images of himself as a passive recipient of drugs and alcohol, devoid of any agency or volitional accounts of his use.

Case Formulation

We conceptualized Dylan’s psychosocial difficulties as resulting from low metacognitive capacity, and we therefore used the Metacognition Assessment Scale–Abbreviated (MAS-A) ( 18 ) to illustrate these deficits. The MAS-A is an adaptation of the Metacognition Assessment Scale, which was originally created by Semerari and colleagues ( 2 ) to assess metacognitive function during psychotherapy. The abbreviated version was modified to allow for the assessment of metacognition in personal narratives and was created in conjunction with the original authors.

The MAS-A is subdivided into four scales, each of which measures a separate facet of metacognition. These four subscales include self-reflectivity, or the ability to identify and ultimately integrate information regarding one’s own internal states; understanding the mind of the other, or one’s ability to identify and synthesize information with regard to the mental states of others; decentration, or the capacity to recognize and consider the unique perspective of others; and mastery, or one’s ability to identify a valid psychological problem and use knowledge of oneself to decrease psychological distress. Higher scores on each of the four subscales are reflective of higher metacognitive capacity, whereby individuals are able to form and then synthesize complex representations of themselves and others.

Regarding self-reflectivity, at the onset of psychotherapy Dylan was able to recognize that his thoughts were his own, but he was unable to recognize and differentiate among a variety of cognitive operations aside from his thoughts and memories. Similarly, Dylan was unable identify or distinguish among his emotional states or integrate how his thoughts or feelings might affect his actions, such as his substance use. During these initial stages of treatment, Dylan’s thoughts were often disorganized, resulting in nonlinear and often confusing narratives interjected with delusional thinking and abstractions.

In terms of understanding the mind of the other, Dylan was initially capable of only the most fundamental interpersonal reflections. At a basic level, Dylan was able to recognize the existence of mental functions within the other, but he was unable to distinguish among mental states or identify emotional states within other people. Regarding decentration, Dylan was initially unable to see things from multiple perspectives or differentiate others’ experiences from his own. Thus, he did not possess the capacity to understand that others might possess differing opinions or perceive events differently than he did.

Last, in terms of mastery, at the onset of therapy Dylan was unable to articulate a psychological problem in a nuanced way. Although he was able to acknowledge himself as having a mental illness and recognize a desire to “stay out of trouble” (given that he was on probation at the time), Dylan was unable to articulate more specifically what this meant to him. As a result, his psychological problem appeared to be more a reflection of something he was socialized to report.

Course of Treatment

Element 1: the preeminent role of the client’s agenda..

This first element of MERIT focuses on what the client wants during each therapy session. It is important to note that a client may present with differing agendas in each session, may present with several different agendas simultaneously, or may even be unaware of some or all of the agendas he or she brings to session. Awareness of and attendance to agendas both known and unknown by the client are of paramount importance in the context of the therapeutic relationship.

At first, it was difficult for the therapist to deduce what Dylan wanted out of therapy. In their initial sessions, Dylan described a general desire to “stay out of trouble,” but he was unable to explain in any detail what this meant to him. Given that Dylan was on probation as a result of a recent drug arrest at this time, it was unclear to the therapist whether Dylan attended their sessions for any reason other than meeting his probation requirements for weekly contacts with a mental health provider.

Although seemingly unrelated, it is also of note that during these first several sessions, Dylan presented to therapy with various objects for what he called “show and tell.” These items largely consisted of kitschy household knickknacks, many of which were acquired from garage sales or passed on unceremoniously to Dylan by acquaintances. Although he expressed a desire to share these items with the therapist, the narrative details of the events surrounding his acquisition of the items quickly revealed a lack of emotional attachment to the items. Given this behavior, Dylan’s apparent lack of psychological distress, and his disorganized thought processes during these initial sessions, the therapist had to be willing to endure the uncertainty and discomfort associated with her desire to make sense of his experiences and understand Dylan’s agenda. Thus, she accepted his agenda as unclear and framed it as something they could mutually explore to later establish his psychological problem and clarify the goals of treatment.

With time, the therapist noticed that Dylan’s disorganization often arose at specific times, such as after discussion of difficult interpersonal interactions or losses, or toward the end of sessions spent integrating these interactions throughout his life. For example, in the wake of discussing a narrative about the loss of his brother during one session, Dylan’s thought processes became increasingly more disorganized, and he began to explain his delusional ideas about the role a government conspiracy played in his loss. Dylan also became notably more disorganized for a few sessions at the end of therapy, during which the therapist and Dylan processed the upcoming termination of their work together.

Similarly, with time the therapist also noticed that Dylan’s pattern of substance use primarily occurred within interpersonal contexts. His use was often spurred by attempts at or failed connections with others, or an apparent desire to elicit caring or concern from his therapist. For example, on one occasion after a sustained period of sobriety, Dylan relapsed with a new acquaintance during the therapist’s extended vacation.

The therapist’s observation of Dylan’s disorganization ultimately led her to form the idea that his disorganization served to protect him from the distress caused by his conflicts or lost connection with others. This understanding afforded her a framework for understanding other behaviors, such as Dylan’s “show and tell” and his pattern of substance use, as attempts to connect with others. Thus, the therapist’s understanding of Dylan’s agenda came to be that his objective was to connect with others, but that this effort was impeded by his low abilities to reflect on the minds of others and view others as distinct individuals with lives independent of his own.

Element 2: introduction of the therapist’s thoughts in ongoing dialogue.

This second element involves discussion of the therapist’s thoughts during therapy in a manner that facilitates an open dialogue between client and therapist. Accomplishment of this element requires that the therapist disclose the contents of his or her mind while also encouraging joint reflection about these thoughts. This reflection on the thoughts of the therapist aids in stimulating the client’s metacognitive capacity to understand the mind of the other. It also increases clients’ self-reflectivity as they explore their own reactions to the mental content of the therapist.

During the early stages of therapy, Dylan frequently presented as disorganized and tangential in session and was unable to recognize his own mental activities or those of others. As a result, the therapist was often confused and left therapy sessions frustrated and exhausted from the strain of attempting to follow Dylan’s train of thought. To address this issue, the therapist inserted her own thoughts during sessions to establish her mind as independent from Dylan’s and to reflect her feelings of confusion. She offered comments such as, “I’m confused; help me understand what made you think of that just now,” or, “I’ve noticed that when you have many thoughts in your head, I find myself confused.” These remarks assisted in scaffolding Dylan’s ability to reflect on his own thinking, which ultimately led to more linear and sequential thought processes.

At later stages in therapy, the therapist offered relatively more complex and integrated reflections to increase the salience of the relationship among Dylan’s substance use, emotions, and interpersonal interactions. For example, she offered comments such as, “I notice that you usually drink only when you’re around others. I wonder if that is because it’s harder to get along with others when you’re sober?” or, “When I was away, you chose to use. I’m wondering what I should make of that?” Dylan was invited to reflect on the thoughts of the therapist and whether he agreed with her interpretations. These reflections helped Dylan to differentiate his thoughts from those of the therapist while also laying the groundwork for establishing a shared sense of his psychological problem.

Element 3: the narrative episode.

The third element of MERIT emphasizes eliciting narrative episodes from the client to facilitate construction of a storied sense of the client’s life events. This eliciting of narrative episodes enables a shared sense by therapist and client of the client over time. In addition, it aids the therapist’s conceptualization of the client as a unique and complex being, rather than as merely a compilation of his or her symptoms.

At the start of therapy, Dylan lacked a storied sense of his life, and, as a result, this was a difficult task to engage in. His thought processes vacillated from barren to disorganized, both between as well as within sessions. He was often unable to temporally anchor when events in his life occurred, and he provided vague overviews of interactions and events. For example, Dylan was unable to identify how old he was or where he was living when a given event occurred. This inability to construct a linear narrative was difficult for the therapist as well, because she had to endure barrages of Dylan’s disorganized thoughts. As a result, she also struggled against feelings of confusion and frustration that arose out of her desire to force integration on Dylan’s life and thoughts.

To stimulate narrative episodes, the therapist inquired about whether there were other times in Dylan’s life when a similar event, thought, or feeling occurred or, conversely, whether there had been times when things were different than the event being described. To elicit narrative details when Dylan provided narratives that were barren, the therapist made numerous specific inquiries about the event (e.g., “How old were you when this happened?” or “Where were you living?”) in an effort to model the level of detail necessary for her to formulate a picture in her mind of the event. When Dylan provided disorganized narratives, the therapist intervened without judgment or correction, with questions aimed at eliciting linear thought, such as, “We were just talking about your mom, and now we’re suddenly talking about your car. Did you notice that, too?”

The therapist also maintained a similarly nonjudgmental and nondirective approach while obtaining narrative details about Dylan’s substance use. In gathering these narrative details, the therapist sought to better understand the context in which Dylan used through questions such as, “Who else was there?” “What time of day was it?” or “What were the thoughts in your mind just before using?”

Over time, Dylan began to provide richer and more detailed narrative episodes and started to self-monitor the tangential shifts in his narratives. He also became better able to reflect on the potential internal catalysts to his use of substances (e.g., “Maybe I was bored?”), which afforded a first step in the establishment of Dylan as an active agent in his decisions and life. As Dylan provided more narrative episodes, the therapist was also able to establish a timeline of his life events, which enabled the therapist and Dylan to possess a joint understanding of his life over time as well as the relationship among these events. Themes of isolation, interpersonal conflict, and loneliness arose from narratives describing his frequent and abrupt moves as a child, the end of his only significant romantic relationship, alcohol and drug use throughout his adult life, and his pattern of taking in people in need as roommates. These themes aided in the conceptualization of Dylan’s psychological problem, which is discussed in more detail below.

Element 4: the psychological problem.

The fourth element to be attended to during therapy is the formulation of a psychological problem. To achieve this element, the client and therapist must jointly identify and agree on a valid and plausible psychological problem. Examples of psychological problems that may manifest in treatment include feelings of loneliness stemming from difficulties in connecting with others, interpersonal conflict resulting from a lack of understanding of the mind of others, and feelings of anger and resentment stemming from past events.

During the early stages of therapy, Dylan was unable to clearly articulate a psychological problem. He expressed a desire to “stay out of trouble” but was unable to describe in any nuanced detail what he meant by that statement. It was clear to the therapist that these utterances were largely related to his recent drug-related arrest with a former friend and were likely parroted from his 12-step program or his interactions with his probation officer.

As therapy progressed and Dylan offered more personal narratives, he began to share narratives with themes of his struggles to connect with others and difficulties in understanding the mental states of others and judging their intentions. He described an unstable childhood with frequent moves, which made it difficult for him to form and maintain relationships; a past confusing and abrupt break-up with a former girlfriend; and his more recent behavior of taking in as roommates people who later became problematic and took advantage of Dylan.

At this point, Dylan’s psychological problem became more clearly defined, given that many of his attempts for connection were thwarted by his difficulties in understanding others. This understanding of Dylan’s psychological problem as a difficulty in connecting with others also afforded the therapist a framework for conceptualizing his actions. For example, his substance use with others provided Dylan with a shared experience that he lacked while sober. Similarly, his attendance at 12-step meetings enabled Dylan to establish relationships with individuals who were also stigmatized as part of an “outgroup.”