- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

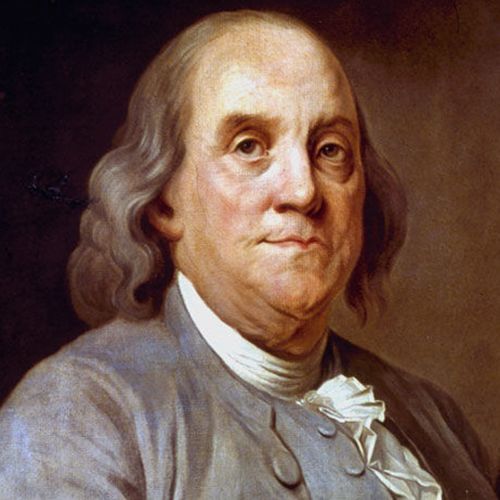

Benjamin Franklin

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 28, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

One of the leading figures of early American history, Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) was a statesman, author, publisher, scientist, inventor and diplomat. Born into a Boston family of modest means, Franklin had little formal education. He went on to start a successful printing business in Philadelphia and grew wealthy. Franklin was deeply active in public affairs in his adopted city, where he helped launch a lending library, hospital and college and garnered acclaim for his experiments with electricity, among other projects. During the American Revolution , he served in the Second Continental Congress and helped draft the Declaration of Independence in 1776. He also negotiated the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War (1775-83). In 1787, in his final significant act of public service, he was a delegate to the convention that produced the U.S. Constitution .

Benjamin Franklin’s Early Years

Benjamin Franklin was born on January 17, 1706, in colonial Boston. His father, Josiah Franklin (1657-1745), a native of England, was a candle and soap maker who married twice and had 17 children. Franklin’s mother was Abiah Folger (1667-1752) of Nantucket, Massachusetts , Josiah’s second wife. Franklin was the eighth of Abiah and Josiah’s 10 offspring.

Did you know? Benjamin Franklin is the only Founding Father to have signed all four of the key documents establishing the U.S.: the Declaration of Independence (1776), the Treaty of Alliance with France (1778), the Treaty of Paris establishing peace with Great Britain (1783) and the U.S. Constitution (1787).

Franklin’s formal education was limited and ended when he was 10; however, he was an avid reader and taught himself to become a skilled writer. In 1718, at age 12, he was apprenticed to his older brother James, a Boston printer. By age 16, Franklin was contributing essays (under the pseudonym Silence Dogood) to a newspaper published by his brother. At age 17, Franklin ran away from his apprenticeship to Philadelphia, where he found work as a printer. In late 1724, he traveled to London, England, and again found employment in the printing business.

Benjamin Franklin: Printer and Publisher

Benjamin Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1726, and two years later opened a printing shop. The business became highly successful producing a range of materials, including government pamphlets, books and currency. In 1729, Franklin became the owner and publisher of a colonial newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette , which proved popular—and to which he contributed much of the content, often using pseudonyms. Franklin achieved fame and further financial success with “Poor Richard’s Almanack,” which he published every year from 1733 to 1758. The almanac became known for its witty sayings, which often had to do with the importance of diligence and frugality, such as “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.”

In 1730, Franklin began living with Deborah Read (c. 1705-74), the daughter of his former Philadelphia landlady, as his common-law wife. Read’s first husband had abandoned her; however, due to bigamy laws, she and Franklin could not have an official wedding ceremony. Franklin and Read had a son, Francis Folger Franklin (1732-36), who died of smallpox at age 4, and a daughter, Sarah Franklin Bache (1743-1808). Franklin had another son, William Franklin (c. 1730-1813), who was born out of wedlock. William Franklin served as the last colonial governor of New Jersey , from 1763 to 1776, and remained loyal to the British during the American Revolution . He died in exile in England.

Benjamin Franklin and Philadelphia

As Franklin’s printing business prospered, he became increasingly involved in civic affairs. Starting in the 1730s, he helped establish a number of community organizations in Philadelphia, including a lending library (it was founded in 1731, a time when books weren’t widely available in the colonies, and remained the largest U.S. public library until the 1850s), the city’s first fire company , a police patrol and the American Philosophical Society , a group devoted to the sciences and other scholarly pursuits.

Franklin also organized the Pennsylvania militia, raised funds to build a city hospital and spearheaded a program to pave and light city streets. Additionally, Franklin was instrumental in the creation of the Academy of Philadelphia, a college which opened in 1751 and became known as the University of Pennsylvania in 1791.

Franklin also was a key figure in the colonial postal system. In 1737, the British appointed him postmaster of Philadelphia, and he went on to become, in 1753, joint postmaster general for all the American colonies. In this role he instituted various measures to improve mail service; however, the British dismissed him from the job in 1774 because he was deemed too sympathetic to colonial interests. In July 1775, the Continental Congress appointed Franklin the first postmaster general of the United States, giving him authority over all post offices from Massachusetts to Georgia . He held this position until November 1776, when he was succeeded by his son-in-law. (The first U.S. postage stamps, issued on July 1, 1847, featured images of Benjamin Franklin and George Washington .)

Benjamin Franklin's Inventions

In 1748, Franklin, then 42 years old, had expanded his printing business throughout the colonies and become successful enough to stop working. Retirement allowed him to concentrate on public service and also pursue more fully his longtime interest in science. In the 1740s, he conducted experiments that contributed to the understanding of electricity, and invented the lightning rod, which protected buildings from fires caused by lightning. In 1752, he conducted his famous kite experiment and demonstrated that lightning is electricity. Franklin also coined a number of electricity-related terms, including battery, charge and conductor.

In addition to electricity, Franklin studied a number of other topics, including ocean currents, meteorology, causes of the common cold and refrigeration. He developed the Franklin stove, which provided more heat while using less fuel than other stoves, and bifocal eyeglasses, which allow for distance and reading use. In the early 1760s, Franklin invented a musical instrument called the glass armonica. Composers such as Ludwig Beethoven (1770-1827) and Wolfgang Mozart (1756-91) wrote music for Franklin’s armonica; however, by the early part of the 19th century, the once-popular instrument had largely fallen out of use.

READ MORE: 11 Surprising Facts About Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin and the American Revolution

In 1754, at a meeting of colonial representatives in Albany, New York , Franklin proposed a plan for uniting the colonies under a national congress. Although his Albany Plan was rejected, it helped lay the groundwork for the Articles of Confederation , which became the first constitution of the United States when ratified in 1781.

In 1757, Franklin traveled to London as a representative of the Pennsylvania Assembly, to which he was elected in 1751. Over several years, he worked to settle a tax dispute and other issues involving descendants of William Penn (1644-1718), the owners of the colony of Pennsylvania. After a brief period back in the U.S., Franklin lived primarily in London until 1775. While he was abroad, the British government began, in the mid-1760s, to impose a series of regulatory measures to assert greater control over its American colonies. In 1766, Franklin testified in the British Parliament against the Stamp Act of 1765, which required that all legal documents, newspapers, books, playing cards and other printed materials in the American colonies carry a tax stamp. Although the Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, additional regulatory measures followed, leading to ever-increasing anti-British sentiment and eventual armed uprising in the American colonies .

Franklin returned to Philadelphia in May 1775, shortly after the Revolutionary War (1775-83) had begun, and was selected to serve as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, America’s governing body at the time. In 1776, he was part of the five-member committee that helped draft the Declaration of Independence , in which the 13 American colonies declared their freedom from British rule. That same year, Congress sent Franklin to France to enlist that nation’s help with the Revolutionary War. In February 1778, the French signed a military alliance with America and went on to provide soldiers, supplies and money that proved critical to America’s victory in the war.

As minister to France starting in 1778, Franklin helped negotiate and draft the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War.

Benjamin Franklin’s Later Years

In 1785, Franklin left France and returned once again to Philadelphia. In 1787, he was a Pennsylvania delegate to the Constitutional Convention. (The 81-year-old Franklin was the convention’s oldest delegate.) At the end of the convention, in September 1787, he urged his fellow delegates to support the heavily debated new document. The U.S. Constitution was ratified by the required nine states in June 1788, and George Washington (1732-99) was inaugurated as America’s first president in April 1789.

Franklin died a year later, at age 84, on April 17, 1790, in Philadelphia. Following a funeral that was attended by an estimated 20,000 people, he was buried in Philadelphia’s Christ Church cemetery. In his will, he left money to Boston and Philadelphia, which was later used to establish a trade school and a science museum and fund scholarships and other community projects.

More than 200 years after his death, Franklin remains one of the most celebrated figures in U.S. history. His image appears on the $100 bill, and towns, schools and businesses across America are named for him.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin is best known as one of the Founding Fathers who never served as president but was a respected inventor, publisher, scientist and diplomat.

(1706-1790)

Quick Facts

Silence dogood, living in london, wife and children, life in philadelphia, poor richard's almanack, scientist and inventor, electricity, election to the government, stamp act and declaration of independence, life in paris, drafting the u.s. constitution, accomplishments, who was benjamin franklin.

Benjamin Franklin was a Founding Father and a polymath, inventor, scientist, printer, politician, freemason and diplomat. Franklin helped to draft the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution , and he negotiated the 1783 Treaty of Paris ending the Revolutionary War .

His scientific pursuits included investigations into electricity, mathematics and mapmaking. A writer known for his wit and wisdom, Franklin also published Poor Richard’s Almanack , invented bifocal glasses and organized the first successful American lending library.

FULL NAME: Benjamin Franklin BORN: January 17, 1706 BIRTHPLACE: Boston, MA DIED: April 17, 1790

Franklin was born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, in what was then known as the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Franklin’s father, English-born soap and candlemaker Josiah Franklin, had seven children with first wife, Anne Child, and 10 more with second wife, Abiah Folger. Franklin was his 15th child and youngest son.

Franklin learned to read at an early age, and despite his success at the Boston Latin School, he stopped his formal schooling at 10 to work full-time in his cash-strapped father’s candle and soap shop. Dipping wax and cutting wicks didn’t fire the young boy’s imagination, however.

Perhaps to dissuade him from going to sea as one of his other sons had done, Josiah apprenticed 12-year-old Franklin at the print shop run by his older brother James.

Although James mistreated and frequently beat his younger brother, Franklin learned a great deal about newspaper publishing and adopted a similar brand of subversive politics under the printer’s tutelage.

When James refused to publish any of his brother’s writing, 16-year-old Franklin adopted the pseudonym Mrs. Silence Dogood, and “her” 14 imaginative and witty letters delighted readers of his brother’s newspaper, The New England Courant . James grew angry, however, when he learned that his apprentice had penned the letters.

Tired of his brother’s “harsh and tyrannical” behavior, Franklin fled Boston in 1723 although he had three years remaining on a legally binding contract with his master.

He escaped to New York before settling in Philadelphia and began working with another printer. Philadelphia became his home base for the rest of his life.

Encouraged by Pennsylvania Governor William Keith to set up his own print shop, Franklin left for London in 1724 to purchase supplies from stationers, booksellers and printers. When the teenager arrived in England, however, he felt duped when Keith’s letters of introduction never arrived as promised.

Although forced to find work at London’s print shops, Franklin took full advantage of the city’s pleasures—attending theater performances, mingling with the locals in coffee houses and continuing his lifelong passion for reading.

A self-taught swimmer who crafted his own wooden flippers, Franklin performed long-distance swims on the Thames River. (In 1968, he was inducted as an honorary member of the International Swimming Hall of Fame .)

In 1725 Franklin published his first pamphlet, "A Dissertation upon Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain," which argued that humans lack free will and, thus, are not morally responsible for their actions. (Franklin later repudiated this thought and burned all but one copy of the pamphlet still in his possession.)

In 1723, after Franklin moved from Boston to Philadelphia, he lodged at the home of John Read, where he met and courted his landlord’s daughter Deborah.

After Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1726, he discovered that Deborah had married in the interim, only to be abandoned by her husband just months after the wedding.

The future Founding Father rekindled his romance with Deborah Read and he took her as his common-law wife in 1730. Around that time, Franklin fathered a son, William, out of wedlock who was taken in by the couple. The pair’s first son, Francis, was born in 1732, but he died four years later of smallpox. The couple’s only daughter, Sarah, was born in 1743.

The two times Franklin moved to London, in 1757 and again in 1764, it was without Deborah, who refused to leave Philadelphia. His second stay was the last time the couple saw each other. Franklin would not return home before Deborah passed away in 1774 from a stroke at the age of 66.

In 1762, Franklin’s son William took office as New Jersey’s royal governor, a position his father arranged through his political connections in the British government. Franklin’s later support for the patriot cause put him at odds with his loyalist son. When the New Jersey militia stripped William Franklin of his post as royal governor and imprisoned him in 1776, his father chose not to intercede on his behalf.

After his return to Philadelphia in 1726, Franklin held varied jobs including bookkeeper, shopkeeper and currency cutter. In 1728 he returned to a familiar trade - printing paper currency - in New Jersey before partnering with a friend to open his own print shop in Philadelphia that published government pamphlets and books.

In 1730 Franklin was named the official printer of Pennsylvania. By that time, he had formed the “Junto,” a social and self-improvement study group for young men that met every Friday to debate morality, philosophy and politics.

When Junto members sought to expand their reading choices, Franklin helped to incorporate America’s first subscription library, the Library Company of Philadelphia, in 1731.

In 1729 Franklin published another pamphlet, "A Modest Enquiry into The Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency," which advocated for an increase in the money supply to stimulate the economy.

With the cash Franklin earned from his money-related treatise, he was able to purchase The Pennsylvania Gazette newspaper from a former boss. Under his ownership, the struggling newspaper was transformed into the most widely-read paper in the colonies and became one of the first to turn a profit.

He had less luck in 1732 when he launched the first German-language newspaper in the colonies, the short-lived Philadelphische Zeitung . Nonetheless, Franklin’s prominence and success grew during the 1730s.

Franklin amassed real estate and businesses and organized the volunteer Union Fire Company to counteract dangerous fire hazards in Philadelphia. He joined the Freemasons in 1731 and was eventually elected grand master of the Masons of Pennsylvania.

At the end of 1732, Franklin published the first edition of Poor Richard’s Almanack .

In addition to weather forecasts, astronomical information and poetry, the almanac—which Franklin published for 25 consecutive years—included proverbs and Franklin’s witty maxims such as “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise” and “He that lies down with dogs, shall rise up with fleas.”

In the 1740s, Franklin expanded into science and entrepreneurship. His 1743 pamphlet "A Proposal for Promoting Useful Knowledge" underscored his interests and served as the founding document of the American Philosophical Society , the first scientific society in the colonies.

By 1748, the 42-year-old Franklin had become one of the richest men in Pennsylvania, and he became a soldier in the Pennsylvania militia. He turned his printing business over to a partner to give himself more time to conduct scientific experiments. He moved into a new house in 1748.

Franklin was a prolific inventor and scientist who was responsible for the following inventions:

- Franklin stove : Franklin’s first invention, created around 1740, provided more heat with less fuel.

- Bifocals : Anyone tired of switching between two pairs of glasses understands why Franklin developed bifocals that could be used for both distance and reading.

- Armonica : Franklin’s inventions took on a musical bent when, in 1761, he commenced development on the armonica, a musical instrument composed of spinning glass bowls on a shaft. Both Ludwig van Beethoven and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed music for the strange instrument.

- Rocking chair

- Flexible catheter

- American penny

Franklin also discovered the Gulf Stream after his return trip across the Atlantic Ocean from London in 1775. He began to speculate about why the westbound trip always took longer, and his measurements of ocean temperatures led to his discovery of the existence of the Gulf Stream. This knowledge served to cut two weeks off the previous sailing time from Europe to North America.

Franklin even devised a new “scheme” for the alphabet that proposed to eliminate the letters C, J, Q, W, X and Y as redundant.

Franklin’s self-education earned him honorary degrees from Harvard , Yale , England’s University of Oxford and the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.

In 1749, Franklin wrote a pamphlet concerning the education of youth in Pennsylvania that resulted in the establishment of the Academy of Philadelphia, now the University of Pennsylvania .

In 1752, Franklin conducted the famous kite-and-key experiment to demonstrate that lightning was electricity and soon after invented the lightning rod.

His investigations into electrical phenomena were compiled into “Experiments and Observations on Electricity,” published in England in 1751. He coined new electricity-related terms that are still part of the lexicon, such as battery, charge, conductor and electrify.

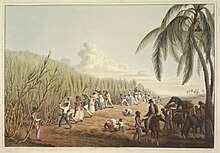

In 1748, Franklin acquired the first of several enslaved people to work in his new home and in the print shop. Franklin’s views on slavery evolved over the following decades to the point that he considered the institution inherently evil, and thus, he freed his enslaved people in the 1760s.

Later in life, he became more vociferous in his opposition to slavery. Franklin served as president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and wrote many tracts urging the abolition of slavery . In 1790 he petitioned the U.S. Congress to end slavery and the trade.

Franklin became a member of Philadelphia’s city council in 1748 and a justice of the peace the following year. In 1751, he was elected a Philadelphia alderman and a representative to the Pennsylvania Assembly, a position to which he was re-elected annually until 1764. Two years later, he accepted a royal appointment as deputy postmaster general of North America.

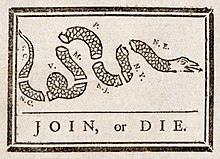

When the French and Indian War began in 1754, Franklin called on the colonies to band together for their common defense, which he dramatized in The Pennsylvania Gazette with a cartoon of a snake cut into sections with the caption “Join or Die.”

He represented Pennsylvania at the Albany Congress, which adopted his proposal to create a unified government for the 13 colonies. Franklin’s “Plan of Union,” however, failed to be ratified by the colonies.

In 1757 Franklin was appointed by the Pennsylvania Assembly to serve as the colony’s agent in England. Franklin sailed to London to negotiate a long-standing dispute with the proprietors of the colony, the Penn family, taking William and his two enslaved people but leaving behind Deborah and Sarah.

He spent much of the next two decades in London, where he was drawn to the high society and intellectual salons of the cosmopolitan city.

After Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1762, he toured the colonies to inspect its post offices.

After Franklin lost his seat in the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1764, he returned to London as the colony’s agent. Franklin returned at a tense time in Great Britain’s relations with the American colonies.

The British Parliament ’s passage of the Stamp Act in March 1765 imposed a highly unpopular tax on all printed materials for commercial and legal use in the American colonies. Since Franklin purchased stamps for his printing business and nominated a friend as the Pennsylvania stamp distributor, some colonists thought Franklin implicitly supported the new tax, and rioters in Philadelphia even threatened his house.

Franklin’s passionate denunciation of the tax in testimony before Parliament, however, contributed to the Stamp Act’s repeal in 1766.

Two years later he penned a pamphlet, “Causes of the American Discontents before 1768,” and he soon became an agent for Massachusetts, Georgia and New Jersey as well. Franklin fanned the flames of revolution by sending the private letters of Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson to America.

The letters called for the restriction of the rights of colonists, which caused a firestorm after their publication by Boston newspapers. In the wake of the scandal, Franklin was removed as deputy postmaster general, and he returned to North America in 1775 as a devotee of the patriot cause.

In 1775, Franklin was elected to the Second Continental Congress and appointed the first postmaster general for the colonies. In 1776, he was appointed commissioner to Canada and was one of five men to draft the Declaration of Independence.

After voting for independence in 1776, Franklin was elected commissioner to France, making him essentially the first U.S. ambassador to France. He set sail to negotiate a treaty for the country’s military and financial support.

Much has been made of Franklin’s years in Paris, chiefly his rich romantic life in his nine years abroad after Deborah’s death. At the age of 74, he even proposed marriage to a widow named Madame Helvetius, but she rejected him.

Franklin was embraced in France as much, if not more, for his wit and intellectual standing in the scientific community as for his status as a political appointee from a fledgling country.

His reputation facilitated respect and entrees into closed communities, including the court of King Louis XVI . And it was his adept diplomacy that led to the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which ended the Revolutionary War. After almost a decade in France, Franklin returned to the United States in 1785.

Franklin was elected in 1787 to represent Pennsylvania at the Constitutional Convention , which drafted and ratified the new U.S. Constitution.

The oldest delegate at the age of 81, Franklin initially supported proportional representation in Congress, but he fashioned the Great Compromise that resulted in proportional representation in the House of Representatives and equal representation by state in the Senate . In 1787, he helped found the Society for Political Inquiries, dedicated to improving knowledge of government.

Franklin was never elected president of the United States. However, he played an important role as one of eight Founding Fathers, helping draft the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

He also served several roles in the government: He was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly and appointed as the first postmaster general for the colonies as well as diplomat to France. He was a true polymath and entrepreneur, which is no doubt why he is often called the "First American."

Franklin died on April 17, 1790, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at the home of his daughter, Sarah Bache. He was 84, suffered from gout and had complained of ailments for some time, completing the final codicil to his will a little more than a year and a half prior to his death.

He bequeathed most of his estate to Sarah and very little to his son William, whose opposition to the patriot cause still stung him. He also donated money that funded scholarships, schools and museums in Boston and Philadelphia.

Franklin had actually written his epitaph when he was 22: “The body of B. Franklin, Printer (Like the Cover of an Old Book Its Contents torn Out And Stript of its Lettering and Gilding) Lies Here, Food for Worms. But the Work shall not be Lost; For it will (as he Believ'd) Appear once More In a New and More Elegant Edition Revised and Corrected By the Author.”

In the end, however, the stone on the grave he shared with his wife in the cemetery of Philadelphia’s Christ Church reads simply, “Benjamin and Deborah Franklin 1790.”

The image of Franklin that has come down through history, along with his likeness on the $100 bill, is something of a caricature—a bald man in a frock coat holding a kite string with a key attached. But the scope of things he applied himself to was so broad it seems a shame.

Founding universities and libraries, the post office, shaping the foreign policy of the fledgling United States, helping to draft the Declaration of Independence, publishing newspapers, warming us with the Franklin stove, pioneering advances in science, letting us see with bifocals and lighting our way with electricity—all from a man who never finished school but shaped his life through abundant reading and experience, a strong moral compass and an unflagging commitment to civic duty. Franklin illuminated corners of American life that still have the lingering glow of his attention.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- A house is not a home unless it contains food and fire for the mind as well as the body.

- Do not fear mistakes. You will know failure. Continue to reach out.

- From a child I was fond of reading, and all the little money that came into my hands was ever laid out in books.

- So convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do.

- In reality, there is, perhaps, no one of our natural passions so hard to subdue as pride. Disguise it, struggle with it, beat it down, stifle it, mortify it as much as one pleases, it is still alive, and will every now and then peep out and show itself; you will see it, perhaps, often in this history; for, even if I could conceive that I had compleatly overcome it, I should probably be proud of my humility.

- Human felicity is produced not so much by great pieces of good fortune that seldom happen, as by little advantages that occur every day.

- There never was a good war or a bad peace.

- In this world nothing is certain but death and taxes.

- Freedom of speech is a principal pillar of a free government; when this support is taken away, the constitution of a free society is dissolved, and tyranny is erected on its ruins.

- He does not possess wealth, it possesses him.

- Experience keeps a dear school, yet fools will learn in no other.

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

American Revolutionaries

Cesare Beccaria

Samuel Adams

Andrew Jackson

George Rogers Clark

Roger Sherman

James Monroe

Martha Washington

Benjamin Franklin

January 17, 1706–April 17, 1790

Benjamin Franklin was a Founding Father, member of the Continental Congress, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and signer of the United States Constitution. Arguably, the most accomplished individual in American history, he was also a successful printer, publisher, scientist, inventor, diplomat, civic leader, statesman, philosopher, and helped negotiate French support during the American Revolutionary War.

Portrait of Benjamin Franklin by Joseph Duplessis. Image Source: Wikimedia.

Biography of Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin was an American printer, scientist, inventor, politician, diplomat, statesman, author, and one of the most colorful characters of the American Revolution.

Franklin was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1706 to Josiah Franklin and Abiah Folger. He was the 15th and youngest son of Josiah’s seventeen children.

Franklin learned the printing trade while working for the weekly Boston newspaper, New England Courant . The paper was owned by his brother James. When the brothers quarreled over letters young Benjamin published under a pseudonym, he left Boston before his apprenticeship expired. Franklin ran off to Philadelphia.

To London and Back

In Philadelphia, Franklin worked as a printer at several different shops. Encouraged by the Governor of Pennsylvania, Sir William Keith, he traveled to London to purchase equipment to start his own newspaper. Unfortunately, this did not work out and Franklin found employment as a typesetter in the Smithfield area of London. A Quaker merchant, Thomas Denham, loaned him the money for passage on a ship back to Philadelphia. In debt to Denham, Franklin worked in his shop until he passed away.

Franklin in Philadelphia

Franklin formally attended school for less than three years, but he read a considerable amount and in 1727 he created the Junto. The Junto was a group of “like minded aspiring artisans and tradesmen who hoped to improve themselves while they improved their community.” The members of the Junto created a library, which eventually led to the creation of the Library Company. In 1731, Franklin chartered the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Marriage to Deborah Read

In 1730, Franklin married Deborah Read by common-law and adopted his illegitimate son, William. The identity of William’s mother remains unknown. Franklin had two other children with Deborah, Francis, born in 1732, and Sarah, born in 1743.

Business Success and Political Connections

Franklin began saving money and became a successful businessman selling books and publishing the weekly Pennsylvania Gazette . He also clerked for the House of Representatives and promoted civic enterprises, such as the library, that still thrive today. He was on good terms with Lord Thomas Penn and was rewarded with local offices. He aligned himself with Penn’s secret agent, William Smith, in opposition to a large influx of German immigrants from the Rhineland, which seemed to threaten English sovereignty. The Germans had been aided by the Quakers in their move to the colony, and in return, the Germans supported Quaker politicians. Franklin was ambivalent toward the Quakers, who were pacifists. Although he respected their toleration, he hated their pacifism. During King George’s War (1744–1748), he organized an extralegal military association that helped him gain popular support, to the dismay of Penn, who feared popular leaders.

Franklin Gains Fame with the Kite Experiment

Franklin’s most famous scientific experiment is likely that of flying a kite in a thunderstorm with a key attached to a piece of twine. The purpose of the experiment was to prove that lightning is a form of electricity. He published the proposal for the experiment in 1750, although there is some debate as to whether or not he actually conducted the experiment himself, due to the danger of electrocution. His experiments and research into electricity, a new science at the time, led the London Royal Society to award him the Copley Gold Medal. As a result, his name became well-known both in America and abroad.

Deputy Postmaster and Pennsylvania Assembly

Franklin was appointed as deputy postmaster of the colonies in 1753 and served in that capacity until 1774. During his tenure, he made the post offices profitable and essentially franchised several printers by supplying them with equipment on a profit-sharing basis. In 1751 he was elected to the Assembly, where he had to cooperate with the dominant Quakers. In 1755 he persuaded German farmers to rent their heavy wagons to Major General Edward Braddock for his doomed campaign against the French and Fort Duquesne.

Albany Congress and Plan of Union

In 1754, the French and Indian War , pitting Great Britain against France and its allies from the Native Tribes, loomed on the horizon. Sensing the need to strengthen the alliance with the powerful Iroquois Confederacy , British officials called for a conference between the American colonies and Iroquois leaders in Albany, New York. Franklin was selected as a delegate from Pennsylvania for the Albany Congress .

The most significant part of the conference was the development of the Albany Plan of Union , which Franklin proposed. The plan outlines a permanent federation of the colonies, as a means to reform colonial-imperial relations and to more effectively address shared colonial interests. The plan was introduced on June 19, and the commissioners adopted a final version on July 10.

Despite the support of those who attended the Albany Congress, the Albany Plan of Union was rejected by King George II and by all of the individual colonial governments that considered its adoption. The Congress and the plan were significant milestones, however, as they marked the first official attempts to develop inter-colonial cooperation among the American colonies.

Franklin Organizes and Leads Pennsylvania Militia

During the French and Indian War (1754–1763), Franklin served in the Pennsylvania Assembly. He helped to organize a legal militia and was chosen as its commanding colonel. He used Tun Tavern in Philadelphia as a recruiting station. The Pennsylvania Militia was organized as Pennsylvania’s 103rd Artillery and 11th Infantry Regiment at the Continental Army. He set up a ring of garrisoned forts for defense against Indian raids and eventually learned that the Indians were upset over being cheated out of their lands by Lord Thomas Penn. This led to Franklin eventually turning against the Quakers.

Franklin Opposes the Stamp Act

In 1764, Franklin found himself embroiled in disputes between members of the Pennsylvania Assembly and the heirs of William Penn. He was dispatched to London where in 1765 he was on hand to voice American opposition to the Stamp Act . His testimony to the House of Commons helped lead to its repeal and he emerged as a leading voice for American interests in England.

Franklin Leaks Massachusetts Letters

For several years, Franklin traveled throughout Europe, where his popularity continued to grow due to his eccentric personality. Yet while in England he grew weary of corruption and was able to obtain the private letters of Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson and Lieutenant Governor, Andrew Oliver. These letters made it clear that they were encouraging the British to come down hard on the rights of the citizens of Boston. He left London in March 1775.

Second Continental Congress and Declaration of Independence

Upon arriving in America, he became a leading figure in the Second Continental Congress , which led to the Declaration of Independence . He served on the Committee of Five, which was tasked with drafting a document that would proclaim to the world the reasons for removing the colonies from the British Empire. The other members were John Adams , Thomas Jefferson , Robert Livingston , and Roger Sherman . Jefferson produced a draft that was reviewed by Adams and Franklin, who recommended minor changes. The document was presented to Congress on Friday, June 28, 1776. At the signing, he supposedly said “Yes, we must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

Peace Negotiations

In December of 1776, Franklin was sent to France to serve as an ambassador of the United States, in an effort to gain aid from the French in the Revolutionary War. He helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which brought peace with Great Britain. He returned to the United States in 1785.

Governor of Pennsylvania

On October 18, 1785, he was elected the sixth President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, a role that is equivalent to Governor. He replaced fellow Founding Father John Dickinson . He was re-elected to a full term on October 29, 1785, then again in the Fall of 1786 and 1787.

Constitutional Convention of 1787

In 1787 he served as a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention which resulted in the United States Constitution. Franklin signed the Constitution, becoming the only Founding Father to have signed the four major documents that helped to found and establish the nation. The other documents were the Declaration of Independence, Treaty of Paris, and Treaty of Alliance with France.

Supporter of Abolition

In his later years, Franklin wrote several essays concerning the abolition of slavery. Those essays were, An Address to the Public , published in 1789, A Plan for Improving the Condition of the Free Blacks , also in 1789, and Sidi Mehemet Ibrahim on the Slave Trade in 1790.

On April 17, 1790, Franklin passed away. His body was laid to rest at Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia.

Significance

Benjamin Franklin is important because he helped write the Declaration of Independence, was involved in negotiating the Treaty of Alliance with France, helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris with Britain that ended the American Revolutionary War, participated in the Constitutional Convention, and signed the United States Constitution. Very few Americans participated in so many key moments in American history and the founding of the nation.

Founding Father

Benjamin Franklin is considered a Founding Father for all of his dedication to the cause of American liberty and freedom. He represented American interests in Europe during the Stamp Act Crisis and after the War for Independence. During the war, he played a vital role in helping shape the direction of the Second Continental Congress, which culminated in the Declaration of Independence. It is quite possible that no other American played as important a role in the political formation of the United States of America as Benjamin Franklin.

Benjamin Franklin — Quick Facts

- Born January 17, 1706, Boston, Massachusetts.

- Attended Boston Latin School from 1714 to 1716.

- Began working as a printer apprenticed to his brother from 1718 to 1723.

- Moved o Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1724.

- Bought the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1729.

- Began publishing Poor Richard’s Almanac in 1733.

- Helped launch the American Philosophical Society in 1743.

- Conducted experiments and verified the nature of electricity during the 1750s.

- Credited with inventing the Franklin Stove, bifocal glasses, and the lightning rod.

- Was instrumental in establishing a library, hospital, fire company, and an insurance company in the City of Philadelphia.

- Moved to London and represented the interests of Pennsylvania, Georgia, New Jersey, and Massachusetts before Parliament from 1757 to 1775.

- Elected to the Second Continental Congress and worked on a committee of five that helped to draft the Declaration of Independence.

- Signed Declaration of Independence in 1776.

- Served as the American Ambassador to France during the American Revolution and during the Confederation Era.

- Signed the Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution, in 1783.

- Served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention and signed the U.S. Constitution.

- Died April 17, 1790, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Buried at Christ Church Burial Ground, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Benjamin Franklin Quotes from “Poor Richard’s Almanack”

“God heals, and the doctor takes the fees.”

“God helps them that help themselves.”

“Work as if you were to live 100 years; pray as if you were to die tomorrow.”

“Keep your eyes open before marriage, half shut afterwards.”

“My father convinced me that nothing was useful which was not honest.”

“Freedom is not a gift bestowed upon us by other men, but a right that belongs to us by the laws of God and nature.”

“Virtue alone is sufficient to make a man great, glorious and happy.”

“Only a virtuous people are capable of freedom. As nations become corrupt and vicious, they have more need of masters.”

- Content for this article has been compiled and edited by Randal Rust .

Biography Online

Benjamin Franklin Biography

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) was a scientist, ambassador, philosopher, statesmen, writer, businessman and celebrated free thinker and wit. Franklin is often referred to as ‘America’s Renaissance Man’ and he played a pivotal role in forging a united American identity during the American Revolution.

Early life Benjamin Franklin

At an early age, he also started writing articles which were published in the ‘New England Courant’ under a pseudonym; Franklin wrote under pseudonyms throughout his life. After several had been published, he admitted to his father that he had written them. Rather than being pleased, his father beat him for his impudence. Therefore, aged 17, the young Benjamin left the family business and travelled to Philadelphia.

“The Constitution only guarantees the American people the right to pursue happiness. You have to catch it yourself.”

- Benjamin Franklin

In Philadelphia, Benjamin’s reputation as an acerbic man of letters grew. His writings were both humorous and satirical, and his capacity to take down powerful men came to the attention of Pennsylvania governor, William Keith. William Keith was fearful of Benjamin’s satire so offered him a job in England with all expenses paid. Benjamin took the offer, but once in England, the governor deserted Franklin, leaving him with no funds.

Benjamin Franklin frequently found himself in awkward situations, but his natural resourcefulness and determination always overcame difficult odds. Benjamin found a job at a printer in London. Here he was known as the “Water American” – as he preferred to drink water rather than the usual six pints of beer daily. Franklin remarked there was ‘more nourishment in a pennyworth of bread than in a quart of beer.’

In 1726, a Quaker Merchant, Mr Denham offered him a position in Philadelphia. Franklin accepted and sailed back to the US.

On his journey home, Benjamin wrote a list of 13 virtues he thought important for his future life. Amongst these were temperance, frugality, sincerity, justice and tranquillity. He originally had 12, but, since a friend remarked he had great pride, he added a 13th – humility (Imitate Jesus and Socrates.)

Virtues of Benjamin Franklin

1. “TEMPERANCE. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.”

2. “SILENCE. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.”

3. “ORDER. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.”

4. “RESOLUTION. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.”

5. “FRUGALITY. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing.”

6. “INDUSTRY. Lose no time; be always employed in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.”

7. “SINCERITY. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly.”

8. “JUSTICE. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.”

9. “MODERATION. Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.”

10. “CLEANLINESS. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, cloaths, or habitation.”

11. “TRANQUILLITY. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.”

12. “CHASTITY. Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation.”

13. “HUMILITY. Imitate Jesus and Socrates.”

Franklin sought to cultivate these virtues throughout the remainder of life. His approach to self-improvement lasted throughout his life.

Back in America, Franklin had many successful endeavours in business, journalism, science and statesmanship.

Scientific Achievements of Benjamin Franklin

Science experiments were a hobby of Franklin. This led to the:

- Franklin stove – a mechanism for distributing heat throughout a room.

- The famous kite and key in the thunderstorm. This proved that lightning and electricity were one and the same thing.

- He was the first person to give electricity positive and negative charges

- The first flexible urinary catheter

- Glass harmonica (also known as the glass armonica)

- Bifocal glasses.

Franklin never patented his inventions, preferring to offer them freely for the benefit of society. As he wrote:

“… as we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours; and this we should do freely and generously.”

Benjamin Franklin as Ambassador

Franklin was chosen as an ambassador to England in the dispute over taxes. For five years he held conferences with political leaders as well as continuing his scientific experiments and musical studies.

Later on, Franklin played a key role in warning the British government over the dangers of taxing the American colonies. In a contest of wills, Franklin was instrumental in encouraging the British Parliament to revoke the hated Stamp Act. However, this reversal was to be short-lived. And when further taxes were issued, Franklin declared himself a supporter of the new American independence movement.

In 1775, he returned to an America in conflict. He was one of the five representatives chosen to draw up the American Declaration of Independence with Thomas Jefferson as the author.

Franklin was chosen to be America’s ambassador to France, where he worked hard to gain the support of the French in America’s war effort. During his time in French society, Franklin was widely admired, and his portrait was hung in many houses.

At the age of 75, the newly formed US government beseeched Franklin to be America’s representative in signing a peace treaty with Great Britain which was signed in 1783.

He was finally replaced as French ambassador by Thomas Jefferson, who paid tribute to his enormous capacity Jefferson remarked; “I succeed him; no one can replace him.”

Religious Beliefs of Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin believed in God throughout his life. In his early life, he professed a belief in Deism. However, he never gave too much importance to organised religion. He was well known for his religious tolerance, and it was remarked how people from different religions could think of him as one of them. As John Adams noted:

“The Catholics thought him almost a Catholic. The Church of England claimed him as one of them. The Presbyterian’s thought him half a Presbyterian, and the Friends believed him a wet Quaker.”

Franklin embodied the spirit of the enlightenment and spirituality over organised religion.

Franklin was a keen debater, but his style was to avoid confrontation and condemnation. He would prefer to argue topics through the asking of awkward questions, not dissimilar to the Greek philosopher Socrates .

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “Biography of Benjamin Franklin ”, Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net , 5th Feb 2010. Last updated 5 March 2019.

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life at Amazon

The Autobiography Of Benjamin Franklin

The Autobiography Of Benjamin Franklin at Amazon

Related pages

Famous Americans – Great Americans from the Founding Fathers to modern civil rights activists. Including presidents, authors, musicians, entrepreneurs and businessmen.

- US politicians

- People who built America

- Quotes by Benjamin Franklin

- Ben Franklin at PBS

Biography of Benjamin Franklin, Printer, Inventor, Statesman

The Image Bank / Getty Images

- Famous Inventors

- Famous Inventions

- Patents & Trademarks

- Invention Timelines

- Computers & The Internet

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706–April 17, 1790) was a scientist, publisher, and statesman in colonial North America, where he lacked the cultural and commercial institutions to nourish original ideas. He dedicated himself to creating those institutions and improving everyday life for the widest number of people, making an indelible mark on the emerging nation.

Fast Facts: Benjamin Franklin

- Born : January 17, 1706 in Boston, Massachusetts

- Parents : Josiah Franklin and Abiah Folger

- Died : April 17, 1790 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Education : Two years of formal education

- Published Works : The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard's Almanack

- Spouse : Deborah Read (common law, 1730–1790)

- Children : William (unknown mother, born about 1730–1731), Francis Folger (1732–1734), Sarah Franklin Bache (1743–1808)

Benjamin Franklin was born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, Massachusetts, to Josiah Franklin, a soap and candlemaker, and his second wife Abiah Folger. Josiah Franklin and his first wife Anne Child (m. 1677–1689) immigrated to Boston from Northamptonshire, England in 1682. Anne died in 1689 and, left with seven children, Josiah soon married a prominent colonist named Abiah Folger.

Benjamin was Josiah's and Abiah's eighth child and Josiah's 10th son and 15th child—Josiah would eventually have 17 children. In such a crowded household, there were no luxuries. Benjamin's period of formal schooling was less than two years, after which he was put to work in his father's shop at the age of 10.

Colonial Newspapers

Franklin's fondness for books finally determined his career. His older brother James Franklin (1697–1735) was the editor and printer of the New England Courant , the fourth newspaper published in the colonies. James needed an apprentice, so in 1718 the 13-year-old Benjamin Franklin was bound by law to serve his brother. Soon after, Benjamin began writing articles for this newspaper. When James was put in jail in February 1723 after printing content considered libelous, the newspaper was published under Benjamin Franklin's name.

Escape to Philadelphia

After a month, James Franklin took back the de facto editorship and Benjamin Franklin went back to being a poorly treated apprentice. In September 1723, Benjamin sailed for New York and then Philadelphia, arriving in October 1723.

In Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin found employment with Samuel Keimer, an eccentric printer just beginning a business. He found lodging at the home of John Read, who would become his father-in-law. The young printer soon attracted the notice of Pennsylvania Governor Sir William Keith, who promised to set him up in his own business. For that to happen, however, Benjamin had to go to London to buy a printing press .

London and 'Pleasure and Pain'

Franklin set sail for London in November 1724, engaged to John Read's daughter Deborah (1708–1774). Governor Keith promised to send a letter of credit to London, but when Franklin arrived he discovered that Keith had not sent the letter; Keith, Franklin learned, was known to have been a man who dealt primarily in "expectations." Benjamin Franklin remained in London for nearly two years as he worked for his fare home.

Franklin found employment at the famous printer's shop owned by Samuel Palmer and helped him produce "The Religion of Nature Delineated" by William Wollaston, which argued that the best way to study religion was through science. Inspired, Franklin printed the first of his many pamphlets in 1725, an attack on conservative religion called "A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain." After a year at Palmer's, Franklin found a better paying job at John Watt's printing house; but in July 1726, he set sail for home with Thomas Denham, a sensible mentor and father figure he had met during his stay in London.

During the 11-week voyage, Franklin wrote "Plan for Future Conduct," the first of his many personal credos describing what lessons he had learned and what he intended to do in the future to avoid pitfalls.

Philadelphia and the Junto Society

After returning to Philadelphia in late 1726, Franklin opened a general store with Thomas Denham and when Denham died in 1727, and Franklin went back to work with the printer Samuel Keimer.

In 1727 he founded the Junto Society, commonly known as the "Leather Apron Club," a small group of middle-class young men who were engaged in business and who met in a local tavern and debated morality, politics, and philosophy. Historian Walter Isaacson described the Junto as a public version of Franklin himself, a "practical, industrious, inquiring, convivial, and middle-brow philosophical [group that] celebrated civic virtue, mutual benefits, the improvement of self and society, and the proposition that hardworking citizens could do well by doing good."

Becoming a Newspaper Man

By 1728, Franklin and another apprentice, Hugh Meredith, set up their own shop with funding from Meredith's father. The son soon sold his share, and Benjamin Franklin was left with his own business at the age of 24. He anonymously printed a pamphlet called "The Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency," which called attention to the need for paper money in Pennsylvania. The effort was a success, and he won the contract to print the money.

In part driven by his competitive streak, Franklin began writing a series of anonymous letters known collectively as the "Busy-Body" essays, signed under several pseudonyms and criticizing the existing newspapers and printers in Philadelphia—including one operated by his old employer Samuel Keimer, called The Universal Instructor in All Arts and Sciences and Pennsylvania Gazette . Keimer went bankrupt in 1729 and sold his 90-subscriber paper to Franklin, who renamed it The Pennsylvania Gazette . The newspaper was later renamed The Saturday Evening Post .

The Gazette printed local news, extracts from the London newspaper Spectator , jokes, verses, humorous attacks on rival Andrew Bradford's American Weekly Mercury , moral essays, elaborate hoaxes, and political satire. Franklin often wrote and printed letters to himself, either to emphasize some truth or to ridicule some mythical but typical reader.

A Common Law Marriage

By 1730, Franklin began looking for a wife. Deborah Read had married during his long stay in London, so Franklin courted a number of girls and even fathered an illegitimate child named William, who was born between April 1730 and April 1731. When Deborah's marriage failed, she and Franklin began living together as a married couple with William in September 1730, an arrangement that protected them from bigamy charges that never materialized.

A Library and 'Poor Richard'

In 1731, Franklin established a subscription library called the Library Company of Philadelphia , in which users would pay dues to borrow books. The first 45 titles purchased included science, history, politics, and reference works. Today, the library has 500,000 books and 160,000 manuscripts and is the oldest cultural institution in the United States.

In 1732, Benjamin Franklin published "Poor Richard's Almanack." Three editions were produced and sold out within a few months. During its 25-year run, the sayings of the publisher Richard Saunders and his wife Bridget—both aliases of Benjamin Franklin—were printed in the almanac. It became a humor classic, one of the earliest in the colonies, and years later the most striking of its sayings were collected and published in a book.

Deborah gave birth to Francis Folger Franklin in 1732. Francis, known as "Franky," died of smallpox at the age of 4 before he could be vaccinated. Franklin, a fierce advocate of smallpox vaccination, had planned to vaccinate the boy but the illness intervened.

Public Service

In 1736, Franklin organized and incorporated the Union Fire Company, based on a similar service established in Boston some years earlier. He became enthralled by the Great Awakening religious revival movement , rushing to the defense of Samuel Hemphill, attending George Whitefield's nightly outdoor revival meetings, and publishing Whitefield's journals between 1739 and 1741 before cooling to the enterprise.

During this period in his life, Franklin also kept a shop in which he sold a variety of goods. Deborah Read was the shopkeeper. He ran a frugal shop, and with all his other activities, Benjamin Franklin's wealth rapidly increased.

American Philosophical Society

About 1743, Franklin moved that the Junto society become intercontinental, and the result was named the American Philosophical Society . Based in Philadelphia, the society had among its members many leading men of scientific attainments or tastes from all over the world. In 1769, Franklin was elected president and served until his death. The first important undertaking was the successful observation of the transit of Venus in 1769; since then, the group has made several important scientific discoveries.

In 1743, Deborah gave birth to their second child Sarah, known as Sally.

An Early 'Retirement'

All of the societies Franklin had created up to this point were noncontroversial, in so far as they kept with the colonial governmental policies. In 1747, however, Franklin proposed the institution of a volunteer Pennsylvania Militia to protect the colony from French and Spanish privateers raiding on the Delaware River. Soon, 10,000 men signed up and formed themselves into more than 100 companies. It was disbanded in 1748, but not before word of what Pennsylvania colony's leader Thomas Penn called "a part little less than treason" was communicated to the British governor.

In 1748 at the age of 42, with a comparatively small family and the frugality of his nature, Franklin was able to retire from active business and devote himself to philosophical and scientific studies.

Franklin the Scientist

Although Franklin had neither formal training nor grounding in math, he now undertook a vast amount of what he called " scientific amusements. " Among his many inventions was the "Pennsylvania fireplace" in 1749, a wood-burning stove that could be built into fireplaces to maximize heat while minimizing smoke and drafts. The Franklin stove was remarkably popular, and Franklin was offered a lucrative patent that he turned down. In his autobiography, Franklin wrote, "As we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours, and this we should do freely and generously." He never patented any of his inventions.

Benjamin Franklin studied many different branches of science. He studied smoky chimneys; he invented bifocal glasses ; he studied the effect of oil upon ruffled water; he identified the "dry bellyache" as lead poisoning; he advocated ventilation in the days when windows were closed tight at night, and with patients at all times; and he investigated fertilizers in agriculture. His scientific observations show that he foresaw some of the great developments of the 19th century.

Electricity

His greatest fame as a scientist was the result of his discoveries in electricity . During a visit to Boston in 1746, he saw some electrical experiments and at once became deeply interested. His friend Peter Collinson of London sent him some of the crude electrical apparatuses of the day, which Franklin used, as well as some equipment he had purchased in Boston. He wrote in a letter to Collinson: "For my own part, I never was before engaged in any study that so engrossed my attention and my time as this has lately done."

Experiments conducted with a small group of friends and described in this correspondence showed the effect of pointed bodies in drawing off electricity. Franklin decided that electricity was not the result of friction, but that the mysterious force was diffused through most substances, and that nature always restored its equilibrium. He developed the theory of positive and negative electricity, or plus and minus electrification.

Franklin carried on experiments with the Leyden jar, made an electrical battery, killed a fowl and roasted it upon a spit turned by electricity, sent a current through water to ignite alcohol, ignited gunpowder, and charged glasses of wine so that the drinkers received shocks.

More importantly, he began to develop the theory of the identity of lightning and electricity and the possibility of protecting buildings with iron rods. He brought electricity into his house using an iron rod, and he concluded, after studying electricity's effect on bells, that clouds were generally negatively electrified. In June 1752, Franklin performed his famous kite experiment, drawing down electricity from the clouds and charging a Leyden jar from the key at the end of the string.

Peter Collinson gathered Benjamin Franklin's letters together and had them published in a pamphlet in England, which attracted wide attention. The Royal Society elected Franklin a member and awarded him the Copley medal with a complimentary address in 1753.

Education and the Making of a Rebel

In 1749, Franklin proposed an academy of education for the youth of Pennsylvania. It would be different from the existing institutions ( Harvard , Yale , Princeton , William & Mary) in that it would be neither religiously affiliated nor reserved for the elites. The focus, he wrote, was to be on practical instruction: writing, arithmetic, accounting, oratory, history, and business skills. It opened in 1751 as the first nonsectarian college in America, and by 1791 it became known as the University of Pennsylvania .

Franklin also raised money for a hospital and began arguing against British restraint of manufacturing in America. He wrestled with the idea of enslavement, personally enslaving and then selling an African American couple in 1751, and then keeping an enslaved person as a servant on occasion later in life. But in his writings, he attacked the practice on economic grounds and helped establish schools for Black children in Philadelphia in the late 1750s. Later, he became an ardent and active abolitionist.

Political Career Begins

In 1751, Franklin took a seat on the Pennsylvania Assembly, where he (literally) cleaned up the streets in Philadelphia by establishing street sweepers, installing street lamps, and paving.

In 1753, he was appointed one of three commissioners to the Carlisle Conference, a congregation of Native American leaders at Albany, New York, intended to secure the allegiance of the Delaware Indians to the British. More than 100 members of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora) attended; the Iroquois leader Scaroyady proposed a peace plan, which was dismissed almost entirely, and the upshot was that the Delaware Indians fought on the side of the French in the final struggles of the French and Indian War.

While in Albany, the colonies' delegates had a second agenda, at Franklin's instigation: to appoint a committee to "prepare and receive plans or schemes for the union of the colonies." They would create a national congress of representatives from each colony, who would be led by a "president general" appointed by the king. Despite some opposition, the measure known as the "Albany Plan" passed, but it was rejected by all of the colonial assemblies as usurping too much of their power and by London as giving too much power to voters and setting a path toward union.

When Franklin returned to Philadelphia, he discovered the British government had finally given him the job he had been lobbying for: deputy postmaster for the colonies.

Post Office

As deputy postmaster, Franklin visited nearly all the post offices in the colonies and introduced many improvements into the service. He established new postal routes and shortened others. Postal carriers now could deliver newspapers, and the mail service between New York and Philadelphia was increased to three deliveries a week in summer and one in winter.

Franklin set milestones at fixed distances along the main post road that ran from northern New England to Savannah, Georgia, to enable the postmasters to compute postage. Crossroads connected some of the larger communities away from the seacoast with the main road, but when Benjamin Franklin died, after also serving as postmaster general of the United States, there were still only 75 post offices in the entire country.

Defense Funding

Raising funds for the defense was always a grave problem in the colonies because the assemblies controlled the purse-strings and released them with a grudging hand. When the British sent General Edward Braddock to defend the colonies in the French and Indian war, Franklin personally guaranteed that the required funds from the Pennsylvania farmers would be repaid.

The assembly refused to raise a tax on the British peers who owned much of the land in Pennsylvania (the "Proprietary Faction") in order to pay those farmers for their contribution, and Franklin was outraged. In general, Franklin opposed Parliament levying taxes on the colonies—no taxation without representation—but he used all his influence to bring the Quaker Assembly to vote for money for the defense of the colony.

In January 1757, the Assembly sent Franklin to London to lobby the Proprietary faction to be more accommodating to the Assembly and, failing that, to bring the issue to the British government.

Franklin reached London in July 1757, and from that time on his life was to be closely linked with Europe. He returned to America six years later and made a trip of 1,600 miles to inspect postal affairs, but in 1764 he was again sent to England to renew the petition for a royal government for Pennsylvania, which had not yet been granted. In 1765, that petition was made obsolete by the Stamp Act, and Franklin became the representative of the American colonies against King George III and Parliament.

Benjamin Franklin did his best to avert the conflict that would become the American Revolution. He made many friends in England, wrote pamphlets and articles, told comical stories and fables where they might do some good, and constantly strove to enlighten the ruling class of England upon conditions and sentiment in the colonies. His appearance before the House of Commons in February 1766 hastened the repeal of the Stamp Act . Benjamin Franklin remained in England for nine more years, but his efforts to reconcile the conflicting claims of Parliament and the colonies were of no avail. He sailed for home in early 1775.

During Franklin's 18-month stay in America, he sat in the Continental Congress and was a member of the most important committees; submitted a plan for a union of the colonies; served as postmaster general and as chairman of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety; visited George Washington at Cambridge; went to Montreal to do what he could for the cause of independence in Canada; presided over the convention that framed a constitution for Pennsylvania; and was a member of the committee appointed to draft the Declaration of Independence and of the committee sent on the futile mission to New York to discuss terms of peace with Lord Howe.

Treaty With France

In September 1776, the 70-year-old Benjamin Franklin was appointed envoy to France and sailed soon afterward. The French ministers were not at first willing to make a treaty of alliance, but under Franklin's influence they lent money to the struggling colonies. Congress sought to finance the war with paper currency and by borrowing rather than by taxation. The legislators sent bill after bill to Franklin, who continually appealed to the French government. He fitted out privateers and negotiated with the British concerning prisoners. At length, he won from France recognition of the United States and then the Treaty of Alliance .

The U.S. Constitution

Congress permitted Franklin to return home in 1785, and when he arrived he was pushed to keep working. He was elected president of the Council of Pennsylvania and was twice reelected despite his protests. He was sent to the 1787 Constitutional Convention, which resulted in the creation of the Constitution of the United States . He seldom spoke at the event but was always to the point when he did, and all of his suggestions for the Constitution were followed.

America's most famous citizen lived until near the end of the first year of President George Washington's administration. On April 17, 1790, Benjamin Franklin died at his home in Philadelphia at age 84.

- Clark, Ronald W. "Benjamin Franklin: A Biography." New York: Random House, 1983.

- Fleming, Thomas (ed.). "Benjamin Franklin: A Biography in His Own Words." New York: Harper and Row, 1972.

- Franklin, Benjamin. "The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin." Harvard Classics. New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1909.

- Isaacson, Walter. "Benjamin Franklin: An American Life." New York, Simon and Schuster, 2003.

- Lepore, Jill. "Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin." Boston: Vintage Books, 2013.

- American History Timeline: 1726 to 1750

- History of the United States Postal Service

- The Pennsylvania Colony: A Quaker Experiment in America

- American History Timeline - 1701 - 1725

- Brief History of the Declaration of Independence

- Major Events That Led to the American Revolution

- Samuel Morse and the Invention of the Telegraph

- American Revolution: General Sir Henry Clinton

- American Revolution: Boston Tea Party

- American Revolution: Marquis de Lafayette

- American History Timeline 1601 - 1625

- Biography of Samuel Adams, Revolutionary Activist and Philosopher

- Biography of John Adams, 2nd President of the United States

- American Revolution: General Sir William Howe

- American History Timeline: 1783-1800

- American Revolution: Commodore John Paul Jones

World History Edu

- Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin: Biography and 12 Major Accomplishments

by World History Edu · July 3, 2019

Benjamin Franklin Biography and Accomplishments | Commonly called, the “First American”, Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) was one of America’s most influential Founding Father.

Benjamin Franklin was a prominent Founding Father and a statesman of the United States of America. Over the course of his life, Benjamin pushed himself in areas far and beyond politics. Hence, he ended up becoming one of America’s most renowned inventors, postmasters, printers, civic activists, scientists, authors and diplomats.

He holds the singular honor of having his signature on all four of America’s most sacred documents – the Declaration of Independence ; the Alliance Treaty with France in 1778; the Treaty of Paris in 1783; and the U.S. Constitution in 1787.

Below is an in-depth look at the biography, facts and major accomplishments of Benjamin Franklin, America’s greatest statesman and diplomat.

Early Life and his Printing Businesses

On January 17, 1706, Benjamin Franklin was born in Boston, Massachusetts to Josiah Franklin and Abiah Folger. He was born into a very large family. He had 9 siblings and 7 half-siblings. The relatively large size of the family meant that the Franklins had to do the best that they could to make ends meet since money was not always easy to come by.

Benjamin Franklin’s father, Josiah Franklin, was an English-born soap and candle maker. This form of artisanship was considered one of the lowest paid and ill-attractive jobs in 18th century America. Although he hated doing so, the young Benjamin had no option than to help out at his father’s soap and candle shop.

His favorite pastime was rather reading. At the age of 10, Benjamin Franklin began to self-educate himself by extensively reading and writing, a habit that ended up paying huge dividends in Franklin’s future endeavors.

Benjamin’s father wanted him to become a clergyman. However, and owing to financial difficulties, there was very little to go around the family. As a result, Benjamin Franklin could only get two years’ worth of (formal) schooling in his life. He spent some of those two years at the Boston Latin School.

Silence Dogood

Upon attaining the age of 12, Franklin took up apprenticeship training at his older brother’s (James) printing shop in Boston. Gradually, the young Benjamin expertly built skill sets in writing, printing and editing. Under the pseudonym Silence Dogood , Benjamin Franklin penned several essays in James’ newspaper- the New-England Courant . Benjamin resorted to such cunning tactics because the older Franklin refused publishing his works in the newspaper.

However, all hell broke lose when James discovered that the middle-aged Mrs Silence Dogood was none other than Benjamin Franklin. The fallout between the two brothers was massive; and in 1723, Benjamin Franklin left James’ shop in Boston and set his sights on Philadelphia. The reason why he left was because he felt James failed to treat him well.

With the experience he garnered at his brother’s printing business, Benjamin was able to get a job as printer in Philadelphia. A year later, he was again on the move. This time around, he journeyed across the Atlantic and made his way to London, England. Over there, he worked in Samuel Palmer’s printing shop as a typesetter.

Benjamin Franklin in Poor Richard’s Almanack, 1736

The Pennsylvania Gazette and Poor Richard’s almanack

After a couple of years abroad, Benjamin Franklin returned to America and collaborated with Thomas Denhem to setup a successful printing business in 1726. By 1729, he had started publishing extensively in a Pennsylvania newspaper ( The Pennsylvania Gazette ) that had reasonably wide distribution in the state.

The most famous piece of writing published by Franklin in the newspaper has to be “ Poor Richard’s Almanack ”. The publication, which ran from 1732 to 1758, was fondly received by the public because of its message of frugality and diligence. The newspaper went on to sell about 10,000 copies of the Poor Richard’s Almanack for close to 25 years.

His ultimate goal in entering the printing business, aside from financial reasons, was to propagate what we might now call the “American Dream”. He tried to use the print media to construct a very morally upright and industrious society across the American colonies. Politically, his association with the “Pennsylvania Chronicle” enabled him drum up support for the American Revolution.

Tags: Benjamin Franklin Declaration of Independence Famous Scientists Treaty of Paris 1783 U.S. Founding Fathers

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Next story Alan Turing: Biography, Accomplishments and Death

- Previous story 6 Major Accomplishments of Sir Winston Churchill

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

Antigone in Greek Mythology – Origin Story & Death

History of Saint Patrick: When and Why he became Patron Saint of Ireland