You're signed out

Sign in to ask questions, follow content, and engage with the Community

- Canvas Instructor

- Instructor Guide

How do I create an outcome for a course?

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

in Instructor Guide

Note: You can only embed guides in Canvas courses. Embedding on other sites is not supported.

Community Help

View our top guides and resources:.

To participate in the Instructurer Community, you need to sign up or log in:

Teaching @ Purdue

Applications in Context Topics

- Overview of Applications in Context

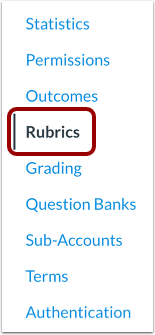

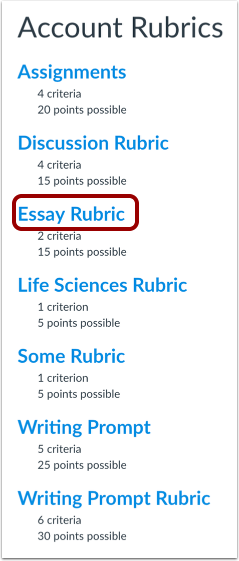

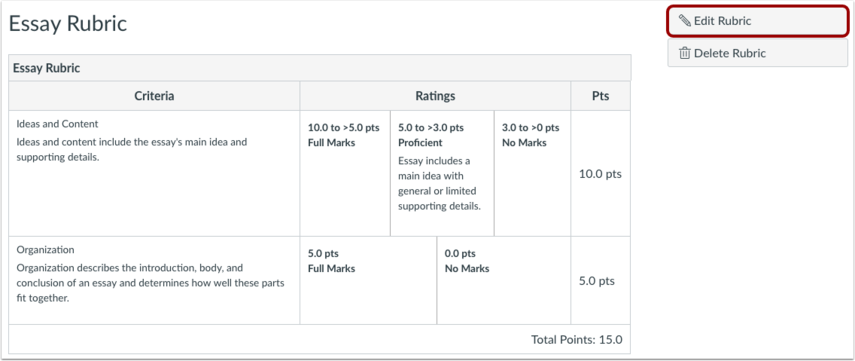

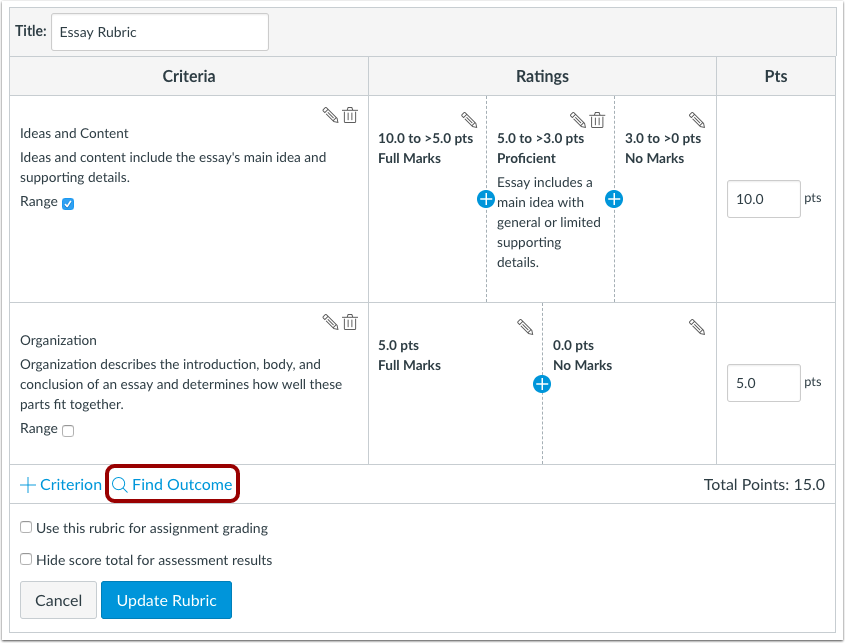

- Rubrics

- Discussions

- Lecturing

- Outcomes and Objectives

- Creating Exams

- Creating Inclusive Grading Structures

Leave Your Feedback Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Outcomes and Objectives

Home » Applications in Context » Outcomes and Objectives

Learning outcomes and objectives are the fundamental elements of most well-designed courses. Well-conceived outcomes and objectives serve as guideposts to help instructors work through the design of a course such that students receive the guidance and structure to achieve meaningful outcomes, as well as guide how those outcomes can be assessed accurately and appropriately.

The Basics of Learning Outcomes and Objectives

Defining terms.

While the terms “learning outcomes” and “learning objectives” are used with varied meanings in varied contexts across higher education, at Purdue we try to use them in a more precise manner. By Learning Outcomes we mean a set of three to five goals that reflect what students will be able to achieve or skills or attitudes they will develop during the class. We use Learning Objective to refer to the steps that lead into a particular outcome. By approaching teaching and learning goals in this way, we can help students understand the path toward successful completion of the class. Some people also use the term Learning Goals , and this can be useful especially in discussions with students about what outcomes and objectives mean, particularly if you co-construct one or more outcomes with students; so, while we do not use the term officially, learning goals may be useful in discussions with students.

Represent the result rather than the means

Outcomes define the end results of a student’s successful engagement in a class. It is important to remember that the ends are different than the means . An outcome is not the process with which students engage to reach that goal, but the end result of achieving that goal. In some cases, the end result will be learning a process, but integrating a process into one’s cognitive and skill repertoire is different than going through a process (e.g., the act of learning how to write a research paper is different than the process of writing a research paper).

A note about Foundational and Embedded learning outcomes

At Purdue, many courses are designated as fulfilling foundational and/or embedded learning outcomes. These outcomes are defined at the university level and assessed regularly. They help to define what it means for a student to complete an undergraduate degree from Purdue, and they set Purdue apart for its high standards of student achievement across a range of core topics. Each of the outcome types is approached and handled differently. Check with your department about if/how your class is designated as fulfilling these outcomes, and email [email protected] if you would like assistance incorporating them into your class.

Writing Meaningful Outcomes

There are numerous strategies for writing effective learning outcomes, and they all have various advantages and disadvantages including more or less structure. One of the most common approaches is to think of outcomes as finishing the following sentence: “Upon successfully completing this course, students will be able to…” This framing emphasizes outcomes as the forward-looking result rather than the means. It also supports transparency by prompting a discussion about what success in the course looks like.

The basics: a verb and an object

If you are just beginning to write outcomes and objectives, try aiming for three components. The following are two similar models that may be useful for thinking through this in your class:

Approach 1:

- The verb generally refers to [actions associated with] the intended cognitive process .

- The object generally describes the knowledge students are expected to acquire or construct.

- A statement regarding the criterion for successful performance .

Approach 2 (from Tobin and Behling’s book, Reach Everyone, Teach Everyone see page 181 in Chapter 7 for examples) :

- Desired behavior , with as much specificity as possible.

- Measurement that explains how you will gauge a student’s mastery.

- Level of proficiency a student should exhibit to have mastered the objective.

The implications of language

We begin with the verb because research into cognitive processes reveals that the verb has profound implications for the type and complexity of cognitive processes. In fact, there are countless lists of verbs, often associated with Benjamin Bloom, a highly influential educational theorist who defined learning around mastery and in doing so began to categorize different types of cognitive, affective, and psychomotor processes based on their difficulty in hierarchical order. In the early 2000s, this work was revised and expanded by a large team of scholars, including adding an additional dimension to the cognitive hierarchy. These verb lists can be misleading, as you may often see the same verb associated with multiple cognitive tasks. We encourage you to use the descriptors in your outcome to identify what students will actually be able to do and ensure that your use of the verb appropriately aligns.

When we ask ourselves questions about the implications of our verb choices, we are often forced to reckon with overused generic terms. The most common example is “understand.” For many, this is the first verb that comes to mind when thinking about what students should be able to do at the end of a course. Consider the popular YouTube series by Wired in which an expert explains a topic at five levels of complexity : a child, a teen, an undergraduate, a graduate student, and a peer expert. At the end of these explanations all have developed or demonstrated an understanding of the concept, but their understanding is vastly different. One mode of working out outcomes and objectives is to start with “understand” and then add a second verb that clarifies the level (what a student at this level will be able to do). Often this use of “understand” lacks clarity unless we add a second verb, in which case it often become clearer and more precise to remove the generic “understand.”

Be transparent: avoid secrets and highlight challenges

Valuing and caring are legitimate outcomes.

Instructors often use what might be termed “secret” learning outcomes or objectives, which are often affective rather than cognitive in nature. For example, in some classes an instructor may want students to appreciate the importance of the subject matter. Often, this involves teaching material that students perceive as tangential to their degree program, but instructors and departments believe is essential. Some common examples involve writing and communication skills, ethics, or legal knowledge in fields where practitioners make use of these competencies every day, but students are often more focused on what they perceive as more quantifiable skills. In the affective learning domain, you may consider outcomes focused on valuing or caring about something (see the alternate outcomes below).

Reveal bottlenecks

Another type of secret or hidden outcome or objective involves something instructors have identified as bottlenecks in their course or discipline. These bottlenecks often reflect ideas, concepts, or skills that may seem small, but when not mastered can pose long-lasting challenges for many students. Sometimes these may seem tangential, like those values described above, other times a bottleneck may be part of a process that students tend to skip (varying modes of checking for errors, for example), or sometimes they require that a student take a different perspective when engaging with a source or problem. Students may often experience these bottlenecks by relying on learning methods that worked with low-complexity topics but cannot handle the complex elements of your course. Some topics are counterintuitive to how we experience the world, and to avoid bottlenecks, students need to overcome their preconceptions and experiences. By highlighting these bottlenecks as explicit outcomes or objectives, making them transparent, pointing to the challenges they pose, and highlighting why it is vital to overcome them, we support students’ long-term success as they move beyond our class as well.

Consider different types of outcomes and objectives

The vast majority of learning outcomes and advice related to outcomes focuses on discrete cognitive skills that are measurable through simple means. For example, a common approach to an outcome may read something like: “Apply the first law of thermodynamics in a closed system.” These discrete and easily measurable skills are vital in many disciplines, but you may also think about learning outcomes that focus on other aspects of one’s life and development. L. Dee Fink, the author of the book Creating Significant Learning Experiences , describes six different outcome categories. The first three deal with these cognitive skills and the second three with affective, interpersonal, and intrapersonal development. By including this second set of goals in our course design and development, we introduce opportunities to support students’ ability to engage in more meaningful ways with each other and, by extension, their feeling of belongingness, connection, and individuality in the class.

- Foundational knowledge : understanding and remembering information and ideas

- Application : skills, critical thinking, creative thinking, practical thinking, and managing projects (e.g., the thermodynamics example above)

- Integration : connecting information, ideas, perspectives, people, or realms of life

- Human dimension : learning about oneself and others

- Caring : developing new feelings, interests, and values

- Learning how to learn : becoming a better student, inquiring about a subject, becoming a self-directed learner

Try treating students as partners around outcomes

Co-construction.

While the broad shape of an outcome will almost always be carefully crafted ahead of time, one approach to help students feel connected to the class is to enlist them in co-constructing parts of an outcome. Most frequently, this co-construction revolves around what success will look like, and it is particularly useful when it is an outcome that in which different students can succeed in different ways. For example, in a discussion-oriented class, one of the outcomes may focus on students developing their communication skills through class participation. But personality and other differences may mean that students have vastly different needs in terms of developing these skills. At a basic level, some students may have greater challenges with speaking up and sharing their thoughts in front of their peers and instructor. Other students may need to better develop their skills in listening to peers and responding productively. By approaching this outcome through co-construction, each student can set and be measured by appropriate goals that will pose a challenge to that student and help them develop important skills.

When outcomes are fixed, focus on communicating and responding to students

In most classes, outcomes and objectives are pre-determined and sometimes must adhere to standards beyond an instructor’s control, whether fitting university requirements or those of national accreditors. Especially in cases where outcomes are fixed, it is too easy to assume that students’ goals are also fixed. Even when classes are required as part of a sequence for a major, students often have widely varying goals for their lives and careers, and sometimes even thoughts regarding how this particular class may fit into achieving their goals. When we start the semester, we can ask students about their goals and what they hope to get out of a class and use existing outcomes and objectives to highlight connections and possibilities. Remember that, because students have not yet engaged with this material, they are much less prepared to make the connections. What may seem obvious to an expert instructor may seem opaque to a learner.

Ask students about the achievements related to outcomes

One common model for understanding student achievement involves asking students about their success specifically related to the course outcomes. This can be done to gauge their perception of success: As a result of your work in this class, what gains did you make in [course outcome]” or to gauge the effectiveness of specific teaching practices: “How much did the following aspects of the course help you in your learning? (Examples might include class and lab activities, assessments, particular learning methods, and resources).” Both of these questions come from the SALG (Student Assessment of Learning Gains) survey/tool (note: the website is rather dated). Studies demonstrate that, while students tend to overestimate their competence relative to instructors, their input broadly is informative, and when these disparities emerge, they can be useful for instructors to interrogate teaching and assessment practices.

Share and reference outcomes and objectives early and often

Discuss outcomes and objectives in every class session.

One of the most common instructor complaints is that students do not pay attention to the outcomes and objectives of a class. This is often a case of mutual neglect. In addition to including class outcomes in your syllabus, highlight outcomes and their connections to objectives in each class session and in instructions for assignments. During class sessions, find opportunities to remind students of these connections. By creating a culture of outcomes and objectives integrated throughout elements of the class, students are better able to follow their progression and understand how different class components and learning integrates and synthesizes with each other.

Build outcomes into the design of assignments

When sharing instructions or guidelines for an assessment, make sure to share and discuss how the assignment fits into the structure of learning outcomes and objectives for the class. See the Creating Inclusive Grading Structures page for more detail and structures.

Write outcomes that reflect your students’ experiences and abilities

Prepare for different academic experiences.

One challenge in planning a class is that it is easy to imagine an idealized student who will enroll in your class. They will have completed certain other classes, possibly had certain experiences, may have certain goals. This ideal student assumption leads many instructors to complain that students were not properly prepared for their class. When writing outcomes, it is valuable to write them for the reality of students present. In reality, students will take a variety of paths, and prerequisite classes may have been completed at other institutions or with a variety of instructors who may have emphasized different elements. Even in situations where every student took the exact same class with the exact same instructor the exact semester prior, students’ strengths and weaknesses with particular topics and skills covered will vary. This does not mean you must re-teach prerequisite courses but building in objectives that highlight particular elements of previous classes will help strengthen and clarify previous learning in addition to helping students identify existing gaps to fill.

Outcomes can reflect a multitude of expressive processes

As outcomes — particularly their language — are intimately intertwined with assessment processes, think carefully about how wording choices may limit students’ ability to express their learning. If the outcome specifies writing, is learning to write in the appropriate format and for the appropriate audience central or is writing one common way (e.g., written language) enough for students to express the more central component of an outcome? What if “write” were turned into “express,” “share,” or “present,” all of which open up greater flexibility in modality of conveying a student’s understanding of content or mastery of skills that are not specific to the written form?

Use the Learning Outcomes Worksheet to practice writing at least one outcome and identifying what category you would place it in. You will find a variety of actual examples from Purdue instructors on the second page of the worksheet.

Learning Outcomes

After you have developed one or more outcomes, view the Creating Inclusive Grading Structures and/or Lecturing pages to consider ways of putting your new outcome(s) into practice in your class.

Hanstedt, P. (2018). Creating wicked students: Designing courses for a complex world . Stylus Publishing.

In this book, Hanstedt argues for creating courses to prepare students to deal with complex problems that do not have simple answers and often draw on a variety of different disciplinary skills and techniques. Chapter 2 , in particular, focuses on writing goals (his term for outcomes), with numerous examples.

Fink, L. D. (2013) Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college course . John Wiley & Sons.

As noted above, Fink's approach focuses on creating outcomes (also using the term goals) that fit six distinct categories. Like Handstedt, Fink provides guidance and numerous examples of how to construct such goals.

Anderson L. W. & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives . Longman.

This update/revision to Bloom's cognitive domain includes numerous resources and examples as well as adds a cognitive process dimension, recognizing that any of the six cognitive categories can also be broken down into four processes: factual knowledge, conceptual knowledge, procedural knowledge, and metacognitive knowledge.

Note: Purdue Libraries only has a print version of this book. You can find online resources developed by Iowa State University, including detailed information about the knowledge dimension.

Module Navigation

- Next Module: Creating Exams

- Previous Module: Lecturing

- Current Topic: Applications in Context

- Next Topic: Certificate Program

Teaching Commons Conference 2024

Join us for the Teaching Commons Conference 2024 – Cultivating Connection. Friday, May 10.

Creating Learning Outcomes

Main navigation.

A learning outcome is a concise description of what students will learn and how that learning will be assessed. Having clearly articulated learning outcomes can make designing a course, assessing student learning progress, and facilitating learning activities easier and more effective. Learning outcomes can also help students regulate their learning and develop effective study strategies.

Defining the terms

Educational research uses a number of terms for this concept, including learning goals, student learning objectives, session outcomes, and more.

In alignment with other Stanford resources, we will use learning outcomes as a general term for what students will learn and how that learning will be assessed. This includes both goals and objectives. We will use learning goals to describe general outcomes for an entire course or program. We will use learning objectives when discussing more focused outcomes for specific lessons or activities.

For example, a learning goal might be “By the end of the course, students will be able to develop coherent literary arguments.”

Whereas a learning objective might be, “By the end of Week 5, students will be able to write a coherent thesis statement supported by at least two pieces of evidence.”

Learning outcomes benefit instructors

Learning outcomes can help instructors in a number of ways by:

- Providing a framework and rationale for making course design decisions about the sequence of topics and instruction, content selection, and so on.

- Communicating to students what they must do to make progress in learning in your course.

- Clarifying your intentions to the teaching team, course guests, and other colleagues.

- Providing a framework for transparent and equitable assessment of student learning.

- Making outcomes concerning values and beliefs, such as dedication to discipline-specific values, more concrete and assessable.

- Making inclusion and belonging explicit and integral to the course design.

Learning outcomes benefit students

Clearly, articulated learning outcomes can also help guide and support students in their own learning by:

- Clearly communicating the range of learning students will be expected to acquire and demonstrate.

- Helping learners concentrate on the areas that they need to develop to progress in the course.

- Helping learners monitor their own progress, reflect on the efficacy of their study strategies, and seek out support or better strategies. (See Promoting Student Metacognition for more on this topic.)

Choosing learning outcomes

When writing learning outcomes to represent the aims and practices of a course or even a discipline, consider:

- What is the big idea that you hope students will still retain from the course even years later?

- What are the most important concepts, ideas, methods, theories, approaches, and perspectives of your field that students should learn?

- What are the most important skills that students should develop and be able to apply in and after your course?

- What would students need to have mastered earlier in the course or program in order to make progress later or in subsequent courses?

- What skills and knowledge would students need if they were to pursue a career in this field or contribute to communities impacted by this field?

- What values, attitudes, and habits of mind and affect would students need if they are to pursue a career in this field or contribute to communities impacted by this field?

- How can the learning outcomes span a wide range of skills that serve students with differing levels of preparation?

- How can learning outcomes offer a range of assessment types to serve a diverse student population?

Use learning taxonomies to inform learning outcomes

Learning taxonomies describe how a learner’s understanding develops from simple to complex when learning different subjects or tasks. They are useful here for identifying any foundational skills or knowledge needed for more complex learning, and for matching observable behaviors to different types of learning.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a hierarchical model and includes three domains of learning: cognitive, psychomotor, and affective. In this model, learning occurs hierarchically, as each skill builds on previous skills towards increasingly sophisticated learning. For example, in the cognitive domain, learning begins with remembering, then understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and lastly creating.

Taxonomy of Significant Learning

The Taxonomy of Significant Learning is a non-hierarchical and integral model of learning. It describes learning as a meaningful, holistic, and integral network. This model has six intersecting domains: knowledge, application, integration, human dimension, caring, and learning how to learn.

See our resource on Learning Taxonomies and Verbs for a summary of these two learning taxonomies.

How to write learning outcomes

Writing learning outcomes can be made easier by using the ABCD approach. This strategy identifies four key elements of an effective learning outcome:

Consider the following example: Students (audience) , will be able to label and describe (behavior) , given a diagram of the eye at the end of this lesson (condition) , all seven extraocular muscles, and at least two of their actions (degree) .

Audience

Define who will achieve the outcome. Outcomes commonly include phrases such as “After completing this course, students will be able to...” or “After completing this activity, workshop participants will be able to...”

Keeping your audience in mind as you develop your learning outcomes helps ensure that they are relevant and centered on what learners must achieve. Make sure the learning outcome is focused on the student’s behavior, not the instructor’s. If the outcome describes an instructional activity or topic, then it is too focused on the instructor’s intentions and not the students.

Try to understand your audience so that you can better align your learning goals or objectives to meet their needs. While every group of students is different, certain generalizations about their prior knowledge, goals, motivation, and so on might be made based on course prerequisites, their year-level, or majors.

Use action verbs to describe observable behavior that demonstrates mastery of the goal or objective. Depending on the skill, knowledge, or domain of the behavior, you might select a different action verb. Particularly for learning objectives which are more specific, avoid verbs that are vague or difficult to assess, such as “understand”, “appreciate”, or “know”.

The behavior usually completes the audience phrase “students will be able to…” with a specific action verb that learners can interpret without ambiguity. We recommend beginning learning goals with a phrase that makes it clear that students are expected to actively contribute to progressing towards a learning goal. For example, “through active engagement and completion of course activities, students will be able to…”

Example action verbs

Consider the following examples of verbs from different learning domains of Bloom’s Taxonomy . Generally speaking, items listed at the top under each domain are more suitable for advanced students, and items listed at the bottom are more suitable for novice or beginning students. Using verbs and associated skills from all three domains, regardless of your discipline area, can benefit students by diversifying the learning experience.

For the cognitive domain:

- Create, investigate, design

- Evaluate, argue, support

- Analyze, compare, examine

- Solve, operate, demonstrate

- Describe, locate, translate

- Remember, define, duplicate, list

For the psychomotor domain:

- Invent, create, manage

- Articulate, construct, solve

- Complete, calibrate, control

- Build, perform, execute

- Copy, repeat, follow

For the affective domain:

- Internalize, propose, conclude

- Organize, systematize, integrate

- Justify, share, persuade

- Respond, contribute, cooperate

- Capture, pursue, consume

Often we develop broad goals first, then break them down into specific objectives. For example, if a goal is for learners to be able to compose an essay, break it down into several objectives, such as forming a clear thesis statement, coherently ordering points, following a salient argument, gathering and quoting evidence effectively, and so on.

State the conditions, if any, under which the behavior is to be performed. Consider the following conditions:

- Equipment or tools, such as using a laboratory device or a specified software application.

- Situation or environment, such as in a clinical setting, or during a performance.

- Materials or format, such as written text, a slide presentation, or using specified materials.

The level of specificity for conditions within an objective may vary and should be appropriate to the broader goals. If the conditions are implicit or understood as part of the classroom or assessment situation, it may not be necessary to state them.

When articulating the conditions in learning outcomes, ensure that they are sensorily and financially accessible to all students.

Degree

Degree states the standard or criterion for acceptable performance. The degree should be related to real-world expectations: what standard should the learner meet to be judged proficient? For example:

- With 90% accuracy

- Within 10 minutes

- Suitable for submission to an edited journal

- Obtain a valid solution

- In a 100-word paragraph

The specificity of the degree will vary. You might take into consideration professional standards, what a student would need to succeed in subsequent courses in a series, or what is required by you as the instructor to accurately assess learning when determining the degree. Where the degree is easy to measure (such as pass or fail) or accuracy is not required, it may be omitted.

Characteristics of effective learning outcomes

The acronym SMART is useful for remembering the characteristics of an effective learning outcome.

- Specific : clear and distinct from others.

- Measurable : identifies observable student action.

- Attainable : suitably challenging for students in the course.

- Related : connected to other objectives and student interests.

- Time-bound : likely to be achieved and keep students on task within the given time frame.

Examples of effective learning outcomes

These examples generally follow the ABCD and SMART guidelines.

Arts and Humanities

Learning goals.

Upon completion of this course, students will be able to apply critical terms and methodology in completing a written literary analysis of a selected literary work.

At the end of the course, students will be able to demonstrate oral competence with the French language in pronunciation, vocabulary, and language fluency in a 10 minute in-person interview with a member of the teaching team.

Learning objectives

After completing lessons 1 through 5, given images of specific works of art, students will be able to identify the artist, artistic period, and describe their historical, social, and philosophical contexts in a two-page written essay.

By the end of this course, students will be able to describe the steps in planning a research study, including identifying and formulating relevant theories, generating alternative solutions and strategies, and application to a hypothetical case in a written research proposal.

At the end of this lesson, given a diagram of the eye, students will be able to label all of the extraocular muscles and describe at least two of their actions.

Using chemical datasets gathered at the end of the first lab unit, students will be able to create plots and trend lines of that data in Excel and make quantitative predictions about future experiments.

- How to Write Learning Goals , Evaluation and Research, Student Affairs (2021).

- SMART Guidelines , Center for Teaching and Learning (2020).

- Learning Taxonomies and Verbs , Center for Teaching and Learning (2021).

Sign In / Sign Out

- News/Events

- Arts and Sciences

- Design and the Arts

- Engineering

- Future of Innovation in Society

- Health Solutions

- Nursing and Health Innovation

- Public Service and Community Solutions

- Sustainability

- University College

- Thunderbird School of Global Management

- Polytechnic

- Downtown Phoenix

- Online and Extended

- Lake Havasu

- Research Park

- Washington D.C.

Learning Objectives Builder

About learning objectives.

Learning Objectives are statements that describe the specific knowledge, skills, or abilities students will be able to demonstrate in the real world as a result of completing a lesson. Learning objectives should not be assignment-specific, however, an assignment should allow students to demonstrate they have achieved the lesson objective(s). All of the learning objectives should support the course outcomes.

Examples of Learning Objectives

- Describe individual, behavioral, and social factors positively influencing health in the Blue Zones.

- Calculate the median of a set of values using Excel.

- Create a needs analysis using Gilbert’s Performance Matrix.

- Revise a company operations manual to reduce energy consumption.

- Diagram the main constructs of social cognitive theory.

- Summarize the scope and source of food waste in the United States.

Objectives Builder Tool

Use the below objectives builder tool to begin designing objectives. If it’s your first time click “Start Project”. If this is a return visit, click “Resume” to pick up where you left off or “Restart” to start the tutorial over. Follow the on-screen instructions to build your learning objective(s)!

Join the conversation

Quite an impressive tool. With the right verb in place, the learning objectives become clear – in fact they fall into place effortlessly.

The tool is very helpful to know the right verbs to use from the lowest level to the highest in blooms taxonomy.

This tool is very helpful, thank you

Thank you so much for taking the time to share this post about the Objectives Builder Tool. It’s an awesome resource for anyone who wants to create objectives that are clear, measurable, and achievable. Not only will the Objectives Builder Tool help you to create objectives quicker, but it will also make sure that the objectives you set are aligned with the mission and values of your organization. It’s a great way to make sure that everyone is working towards the same goals and that the objectives are measurable and realistic. So thank you for bringing this fantastic tool to our attention. It’s sure to be a beneficial resource for many!

I absolutely love this tool! I am definitely going to use this if I need to create LOs

This tool is very helpful to design online course development

Ok, I love this tool. It helps come up with the best words to use when determining objectives. The statement can then be used to assist with the Backward Design.

This was very helpful!

this embedded app is very useful to create learning objectives

Great steps in online course development

This helped me to organize the objectives for the presentation of my lesson on fluids from statics to dynamics.

This really helped me to create learning objectives for my 6th grade math class!

- Pingback: 3-2-w-cbt-module-assignment-4-writing-objective-redo-1 | Term Paper Tutors

- Pingback: Learning Objectives – Learning at a Distance

- Pingback: Learning objectives and outcomes – Online Teaching at Michigan

- Pingback: LEARN Lesson Detailed Guide – K20 Instructional Design

- Pingback: Why Groupwork is Important, and How to Get it Right – Corpasa

- Pingback: Why Groupwork is Important, and How to Get it Right - Online Education Blog of Touro College

- Pingback: QM Standard 2 – Learning Outcomes – Teaching, Learning, and Instructional Design

- Pingback: Authentic Learning Objectives | Learning Innovations | Washington State University

- Pingback: Learning Objective Generators – Burnt Pixel

- Pingback: Learning Objectives – CAES Instructional Design Support Tutorials

- Pingback: Journal – The Beautiful Thing

- Pingback: Blackboard workshop – Penny's Classroom

- Pingback: Learning Objectives Builder – Ringling Canvas blog

Leave a comment Cancel

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Search Teach Online resources

Course stories podcast.

In this podcast , we tell an array of course design stories alongside other ASU Online designers and faculty.

Design, development and delivery resources for teaching online

Subscribe to our email list.

- Copyright & Trademark

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Contact ASU

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Instructional Technologies

- Teaching in All Modalities

Designing Assignments for Learning

The rapid shift to remote teaching and learning meant that many instructors reimagined their assessment practices. Whether adapting existing assignments or creatively designing new opportunities for their students to learn, instructors focused on helping students make meaning and demonstrate their learning outside of the traditional, face-to-face classroom setting. This resource distills the elements of assignment design that are important to carry forward as we continue to seek better ways of assessing learning and build on our innovative assignment designs.

On this page:

Rethinking traditional tests, quizzes, and exams.

- Examples from the Columbia University Classroom

- Tips for Designing Assignments for Learning

Reflect On Your Assignment Design

Connect with the ctl.

- Resources and References

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2021). Designing Assignments for Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/teaching-with-technology/teaching-online/designing-assignments/

Traditional assessments tend to reveal whether students can recognize, recall, or replicate what was learned out of context, and tend to focus on students providing correct responses (Wiggins, 1990). In contrast, authentic assignments, which are course assessments, engage students in higher order thinking, as they grapple with real or simulated challenges that help them prepare for their professional lives, and draw on the course knowledge learned and the skills acquired to create justifiable answers, performances or products (Wiggins, 1990). An authentic assessment provides opportunities for students to practice, consult resources, learn from feedback, and refine their performances and products accordingly (Wiggins 1990, 1998, 2014).

Authentic assignments ask students to “do” the subject with an audience in mind and apply their learning in a new situation. Examples of authentic assignments include asking students to:

- Write for a real audience (e.g., a memo, a policy brief, letter to the editor, a grant proposal, reports, building a website) and/or publication;

- Solve problem sets that have real world application;

- Design projects that address a real world problem;

- Engage in a community-partnered research project;

- Create an exhibit, performance, or conference presentation ;

- Compile and reflect on their work through a portfolio/e-portfolio.

Noteworthy elements of authentic designs are that instructors scaffold the assignment, and play an active role in preparing students for the tasks assigned, while students are intentionally asked to reflect on the process and product of their work thus building their metacognitive skills (Herrington and Oliver, 2000; Ashford-Rowe, Herrington and Brown, 2013; Frey, Schmitt, and Allen, 2012).

It’s worth noting here that authentic assessments can initially be time consuming to design, implement, and grade. They are critiqued for being challenging to use across course contexts and for grading reliability issues (Maclellan, 2004). Despite these challenges, authentic assessments are recognized as beneficial to student learning (Svinicki, 2004) as they are learner-centered (Weimer, 2013), promote academic integrity (McLaughlin, L. and Ricevuto, 2021; Sotiriadou et al., 2019; Schroeder, 2021) and motivate students to learn (Ambrose et al., 2010). The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning is always available to consult with faculty who are considering authentic assessment designs and to discuss challenges and affordances.

Examples from the Columbia University Classroom

Columbia instructors have experimented with alternative ways of assessing student learning from oral exams to technology-enhanced assignments. Below are a few examples of authentic assignments in various teaching contexts across Columbia University.

- E-portfolios: Statia Cook shares her experiences with an ePorfolio assignment in her co-taught Frontiers of Science course (a submission to the Voices of Hybrid and Online Teaching and Learning initiative); CUIMC use of ePortfolios ;

- Case studies: Columbia instructors have engaged their students in authentic ways through case studies drawing on the Case Consortium at Columbia University. Read and watch a faculty spotlight to learn how Professor Mary Ann Price uses the case method to place pre-med students in real-life scenarios;

- Simulations: students at CUIMC engage in simulations to develop their professional skills in The Mary & Michael Jaharis Simulation Center in the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and the Helene Fuld Health Trust Simulation Center in the Columbia School of Nursing;

- Experiential learning: instructors have drawn on New York City as a learning laboratory such as Barnard’s NYC as Lab webpage which highlights courses that engage students in NYC;

- Design projects that address real world problems: Yevgeniy Yesilevskiy on the Engineering design projects completed using lab kits during remote learning. Watch Dr. Yesilevskiy talk about his teaching and read the Columbia News article .

- Writing assignments: Lia Marshall and her teaching associate Aparna Balasundaram reflect on their “non-disposable or renewable assignments” to prepare social work students for their professional lives as they write for a real audience; and Hannah Weaver spoke about a sandbox assignment used in her Core Literature Humanities course at the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning Symposium . Watch Dr. Weaver share her experiences.

Tips for Designing Assignments for Learning

While designing an effective authentic assignment may seem like a daunting task, the following tips can be used as a starting point. See the Resources section for frameworks and tools that may be useful in this effort.

Align the assignment with your course learning objectives

Identify the kind of thinking that is important in your course, the knowledge students will apply, and the skills they will practice using through the assignment. What kind of thinking will students be asked to do for the assignment? What will students learn by completing this assignment? How will the assignment help students achieve the desired course learning outcomes? For more information on course learning objectives, see the CTL’s Course Design Essentials self-paced course and watch the video on Articulating Learning Objectives .

Identify an authentic meaning-making task

For meaning-making to occur, students need to understand the relevance of the assignment to the course and beyond (Ambrose et al., 2010). To Bean (2011) a “meaning-making” or “meaning-constructing” task has two dimensions: 1) it presents students with an authentic disciplinary problem or asks students to formulate their own problems, both of which engage them in active critical thinking, and 2) the problem is placed in “a context that gives students a role or purpose, a targeted audience, and a genre.” (Bean, 2011: 97-98).

An authentic task gives students a realistic challenge to grapple with, a role to take on that allows them to “rehearse for the complex ambiguities” of life, provides resources and supports to draw on, and requires students to justify their work and the process they used to inform their solution (Wiggins, 1990). Note that if students find an assignment interesting or relevant, they will see value in completing it.

Consider the kind of activities in the real world that use the knowledge and skills that are the focus of your course. How is this knowledge and these skills applied to answer real-world questions to solve real-world problems? (Herrington et al., 2010: 22). What do professionals or academics in your discipline do on a regular basis? What does it mean to think like a biologist, statistician, historian, social scientist? How might your assignment ask students to draw on current events, issues, or problems that relate to the course and are of interest to them? How might your assignment tap into student motivation and engage them in the kinds of thinking they can apply to better understand the world around them? (Ambrose et al., 2010).

Determine the evaluation criteria and create a rubric

To ensure equitable and consistent grading of assignments across students, make transparent the criteria you will use to evaluate student work. The criteria should focus on the knowledge and skills that are central to the assignment. Build on the criteria identified, create a rubric that makes explicit the expectations of deliverables and share this rubric with your students so they can use it as they work on the assignment. For more information on rubrics, see the CTL’s resource Incorporating Rubrics into Your Grading and Feedback Practices , and explore the Association of American Colleges & Universities VALUE Rubrics (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education).

Build in metacognition

Ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the assignment. Help students uncover personal relevance of the assignment, find intrinsic value in their work, and deepen their motivation by asking them to reflect on their process and their assignment deliverable. Sample prompts might include: what did you learn from this assignment? How might you draw on the knowledge and skills you used on this assignment in the future? See Ambrose et al., 2010 for more strategies that support motivation and the CTL’s resource on Metacognition ).

Provide students with opportunities to practice

Design your assignment to be a learning experience and prepare students for success on the assignment. If students can reasonably expect to be successful on an assignment when they put in the required effort ,with the support and guidance of the instructor, they are more likely to engage in the behaviors necessary for learning (Ambrose et al., 2010). Ensure student success by actively teaching the knowledge and skills of the course (e.g., how to problem solve, how to write for a particular audience), modeling the desired thinking, and creating learning activities that build up to a graded assignment. Provide opportunities for students to practice using the knowledge and skills they will need for the assignment, whether through low-stakes in-class activities or homework activities that include opportunities to receive and incorporate formative feedback. For more information on providing feedback, see the CTL resource Feedback for Learning .

Communicate about the assignment

Share the purpose, task, audience, expectations, and criteria for the assignment. Students may have expectations about assessments and how they will be graded that is informed by their prior experiences completing high-stakes assessments, so be transparent. Tell your students why you are asking them to do this assignment, what skills they will be using, how it aligns with the course learning outcomes, and why it is relevant to their learning and their professional lives (i.e., how practitioners / professionals use the knowledge and skills in your course in real world contexts and for what purposes). Finally, verify that students understand what they need to do to complete the assignment. This can be done by asking students to respond to poll questions about different parts of the assignment, a “scavenger hunt” of the assignment instructions–giving students questions to answer about the assignment and having them work in small groups to answer the questions, or by having students share back what they think is expected of them.

Plan to iterate and to keep the focus on learning

Draw on multiple sources of data to help make decisions about what changes are needed to the assignment, the assignment instructions, and/or rubric to ensure that it contributes to student learning. Explore assignment performance data. As Deandra Little reminds us: “a really good assignment, which is a really good assessment, also teaches you something or tells the instructor something. As much as it tells you what students are learning, it’s also telling you what they aren’t learning.” ( Teaching in Higher Ed podcast episode 337 ). Assignment bottlenecks–where students get stuck or struggle–can be good indicators that students need further support or opportunities to practice prior to completing an assignment. This awareness can inform teaching decisions.

Triangulate the performance data by collecting student feedback, and noting your own reflections about what worked well and what did not. Revise the assignment instructions, rubric, and teaching practices accordingly. Consider how you might better align your assignment with your course objectives and/or provide more opportunities for students to practice using the knowledge and skills that they will rely on for the assignment. Additionally, keep in mind societal, disciplinary, and technological changes as you tweak your assignments for future use.

Now is a great time to reflect on your practices and experiences with assignment design and think critically about your approach. Take a closer look at an existing assignment. Questions to consider include: What is this assignment meant to do? What purpose does it serve? Why do you ask students to do this assignment? How are they prepared to complete the assignment? Does the assignment assess the kind of learning that you really want? What would help students learn from this assignment?

Using the tips in the previous section: How can the assignment be tweaked to be more authentic and meaningful to students?

As you plan forward for post-pandemic teaching and reflect on your practices and reimagine your course design, you may find the following CTL resources helpful: Reflecting On Your Experiences with Remote Teaching , Transition to In-Person Teaching , and Course Design Support .

The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) is here to help!

For assistance with assignment design, rubric design, or any other teaching and learning need, please request a consultation by emailing [email protected] .

Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) framework for assignments. The TILT Examples and Resources page ( https://tilthighered.com/tiltexamplesandresources ) includes example assignments from across disciplines, as well as a transparent assignment template and a checklist for designing transparent assignments . Each emphasizes the importance of articulating to students the purpose of the assignment or activity, the what and how of the task, and specifying the criteria that will be used to assess students.

Association of American Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) offers VALUE ADD (Assignment Design and Diagnostic) tools ( https://www.aacu.org/value-add-tools ) to help with the creation of clear and effective assignments that align with the desired learning outcomes and associated VALUE rubrics (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education). VALUE ADD encourages instructors to explicitly state assignment information such as the purpose of the assignment, what skills students will be using, how it aligns with course learning outcomes, the assignment type, the audience and context for the assignment, clear evaluation criteria, desired formatting, and expectations for completion whether individual or in a group.

Villarroel et al. (2017) propose a blueprint for building authentic assessments which includes four steps: 1) consider the workplace context, 2) design the authentic assessment; 3) learn and apply standards for judgement; and 4) give feedback.

References

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., & DiPietro, M. (2010). Chapter 3: What Factors Motivate Students to Learn? In How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching . Jossey-Bass.

Ashford-Rowe, K., Herrington, J., and Brown, C. (2013). Establishing the critical elements that determine authentic assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 39(2), 205-222, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.819566 .

Bean, J.C. (2011). Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom . Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Frey, B. B, Schmitt, V. L., and Allen, J. P. (2012). Defining Authentic Classroom Assessment. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. 17(2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.7275/sxbs-0829

Herrington, J., Reeves, T. C., and Oliver, R. (2010). A Guide to Authentic e-Learning . Routledge.

Herrington, J. and Oliver, R. (2000). An instructional design framework for authentic learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(3), 23-48.

Litchfield, B. C. and Dempsey, J. V. (2015). Authentic Assessment of Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 142 (Summer 2015), 65-80.

Maclellan, E. (2004). How convincing is alternative assessment for use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 29(3), June 2004. DOI: 10.1080/0260293042000188267

McLaughlin, L. and Ricevuto, J. (2021). Assessments in a Virtual Environment: You Won’t Need that Lockdown Browser! Faculty Focus. June 2, 2021.

Mueller, J. (2005). The Authentic Assessment Toolbox: Enhancing Student Learning through Online Faculty Development . MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. 1(1). July 2005. Mueller’s Authentic Assessment Toolbox is available online.

Schroeder, R. (2021). Vaccinate Against Cheating With Authentic Assessment . Inside Higher Ed. (February 26, 2021).

Sotiriadou, P., Logan, D., Daly, A., and Guest, R. (2019). The role of authentic assessment to preserve academic integrity and promote skills development and employability. Studies in Higher Education. 45(111), 2132-2148. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1582015

Stachowiak, B. (Host). (November 25, 2020). Authentic Assignments with Deandra Little. (Episode 337). In Teaching in Higher Ed . https://teachinginhighered.com/podcast/authentic-assignments/

Svinicki, M. D. (2004). Authentic Assessment: Testing in Reality. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 100 (Winter 2004): 23-29.

Villarroel, V., Bloxham, S, Bruna, D., Bruna, C., and Herrera-Seda, C. (2017). Authentic assessment: creating a blueprint for course design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 43(5), 840-854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice . Second Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wiggins, G. (2014). Authenticity in assessment, (re-)defined and explained. Retrieved from https://grantwiggins.wordpress.com/2014/01/26/authenticity-in-assessment-re-defined-and-explained/

Wiggins, G. (1998). Teaching to the (Authentic) Test. Educational Leadership . April 1989. 41-47.

Wiggins, Grant (1990). The Case for Authentic Assessment . Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation , 2(2).

Wondering how AI tools might play a role in your course assignments?

See the CTL’s resource “Considerations for AI Tools in the Classroom.”

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Creating and Adapting Assignments for Online Courses

Online teaching requires a deliberate shift in how we communicate, deliver information, and offer feedback to our students. How do you effectively design and modify your assignments to accommodate this shift? The ways you introduce students to new assignments, keep them on track, identify and remedy confusion, and provide feedback after an assignment is due must be altered to fit the online setting. Intentional planning can help you ensure assignments are optimally designed for an online course and expectations are clearly communicated to students.

When teaching online, it can be tempting to focus on the differences from in-person instruction in terms of adjustments, or what you need to make up for. However, there are many affordances of online assignments that can deepen learning and student engagement. Students gain new channels of interaction, flexibility in when and where they access assignments, more immediate feedback, and a student-centered experience (Gayten and McEwen, 2007; Ragupathi, 2020; Robles and Braathen, 2002). Meanwhile, ample research has uncovered that online assignments benefit instructors through automatic grading, better measurement of learning, greater student involvement, and the storing and reuse of assignments.

In Practice

While the purpose and planning of online assignments remain the same as their in-person counterparts, certain adjustments can make them more effective. The strategies outlined below will help you design online assignments that support student success while leveraging the benefits of the online environment.

Align assignments to learning outcomes.

All assignments work best when they align with your learning outcomes. Each online assignment should advance students' achievement of one or more of your specific outcomes. You may be familiar with Bloom's Taxonomy, a well-known framework that organizes and classifies learning objectives based on the actions students take to demonstrate their learning. Online assignments have the added advantage of flexing students' digital skills, and Bloom's has been revamped for the digital age to incorporate technology-based tasks into its categories. For example, students might search for definitions online as they learn and remember course materials, tweet their understanding of a concept, mind map an analysis, or create a podcast.

See a complete description of Bloom's Digital Taxonomy for further ideas.

Provide authentic assessments.

Authentic assessments call for relevant, purposeful actions that mimic the real-life tasks students may encounter in their lives and careers beyond the university. They represent a shift away from infrequent high-stakes assessments that tend to evaluate the acquisition of knowledge over application and understanding. Authentic assessments allow students to see the connection between what they're learning and how that learning is used and contextualized outside the virtual walls of the learning management system, thereby increasing their motivation and engagement.

There are many ways to incorporate authenticity into an assignment, but three main strategies are to use authentic audiences, content, and formats . A student might, for example, compose a business plan for an audience of potential investors, create a patient care plan that translates medical jargon into lay language, or propose a safe storage process for a museum collection.

Authentic assessments in online courses can easily incorporate the internet or digital tools as part of an authentic format. Blogs, podcasts, social media posts, and multimedia artifacts such as infographics and videos represent authentic formats that leverage the online context.

Learn more about authentic assessments in Designing Assessments of Student Learning .

Design for inclusivity and accessibility.

Adopting universal design principles at the outset of course creation will ensure your material is accessible to all students. As you plan your assignments, it's important to keep in mind barriers to access in terms of tools, technology, and cost. Consider which tools achieve your learning outcomes with the fewest barriers.

Offering a variety of assignment formats is one way to ensure students can demonstrate learning in a manner that works best for them. You can provide options within an individual assignment, such as allowing students to submit either written text or an audio recording or to choose from several technologies or platforms when completing a project.

Be mindful of how you frame and describe an assignment to ensure it doesn't disregard populations through exclusionary language or use culturally specific references that some students may not understand. Inclusive language for all genders and racial or ethnic backgrounds can foster a sense of belonging that fully invests students in the learning community.

Learn more about Universal Design of Learning and Shaping a Positive Learning Environment .

Design to promote academic integrity online.

Much like incorporating universal design principles at the outset of course creation, you can take a proactive approach to academic integrity online. Design assignments that limit the possibilities for students to use the work of others or receive prohibited outside assistance.

Provide authentic assessments that are more difficult to plagiarize because they incorporate recent events or unique contexts and formats.

Scaffold assignments so that students can work their way up to a final product by submitting smaller portions and receiving feedback along the way.

Lower the stakes by providing more frequent formative assessments in place of high-stakes, high-stress assessments.

In addition to proactively creating assignments that deter cheating, there are several university-supported tools at your disposal to help identify and prevent cheating.

Learn more about these tools in Strategies and Tools for Academic Integrity in Online Environments .

Communicate detailed instructions and clarify expectations.

When teaching in-person, you likely dedicate class time to introducing and explaining an assignment; students can ask questions or linger after class for further clarification. In an online class, especially in asynchronous online classes, you must anticipate where students' questions might arise and account for them in the assignment instructions.

The Carmen course template addresses some of students' common questions when completing an assignment. The template offers places to explain the assignment's purpose, list out steps students should take when completing it, provide helpful resources, and detail academic integrity considerations.

Providing a rubric will clarify for students how you will evaluate their work, as well as make your grading more efficient. Sharing examples of previous student work (both good and bad) can further help students see how everything should come together in their completed products.

Technology Tip

Enter all assignments and due dates in your Carmen course to increase transparency. When assignments are entered in Carmen, they also populate to Calendar, Syllabus, and Grades areas so students can easily track their upcoming work. Carmen also allows you to develop rubrics for every assignment in your course.

Promote interaction and collaboration.

Frequent student-student interaction in any course, but particularly in online courses, is integral to developing a healthy learning community that engages students with course material and contributes to academic achievement. Online education has the inherent benefit of offering multiple channels of interaction through which this can be accomplished.

Carmen Discussions are a versatile platform for students to converse about and analyze course materials, connect socially, review each other's work, and communicate asynchronously during group projects.

Peer review can be enabled in Carmen Assignments and Discussions . Rubrics can be attached to an assignment or a discussion that has peer review enabled, and students can use these rubrics as explicit criteria for their evaluation. Alternatively, peer review can occur within the comments of a discussion board if all students will benefit from seeing each other's responses.

Group projects can be carried out asynchronously through Carmen Discussions or Groups , or synchronously through Carmen's Chat function or CarmenZoom . Students (and instructors) may have apprehensions about group projects, but well-designed group work can help students learn from each other and draw on their peers’ strengths. Be explicit about your expectations for student interaction and offer ample support resources to ensure success on group assignments.

Learn more about Student Interaction Online .

Choose technology wisely.

The internet is a vast and wondrous place, full of technology and tools that do amazing things. These tools can give students greater flexibility in approaching an assignment or deepen their learning through interactive elements. That said, it's important to be selective when integrating external tools into your online course.

Look first to your learning outcomes and, if you are considering an external tool, determine whether the technology will help students achieve these learning outcomes. Unless one of your outcomes is for students to master new technology, the cognitive effort of using an unfamiliar tool may distract from your learning outcomes.

Carmen should ultimately be the foundation of your course where you centralize all materials and assignments. Thoughtfully selected external tools can be useful in certain circumstances.

Explore supported tools

There are many university-supported tools and resources already available to Ohio State users. Before looking to external tools, you should explore the available options to see if you can accomplish your instructional goals with supported systems, including the eLearning toolset , approved CarmenCanvas integrations , and the Microsoft365 suite .

If a tool is not university-supported, keep in mind the security and accessibility implications, the learning curve required to use the tool, and the need for additional support resources. If you choose to use a new tool, provide links to relevant help guides on the assignment page or post a video tutorial. Include explicit instructions on how students can get technical support should they encounter technical difficulties with the tool.

Adjustments to your assignment design can guide students toward academic success while leveraging the benefits of the online environment.

Effective assignments in online courses are:

Aligned to course learning outcomes

Authentic and reflect real-life tasks

Accessible and inclusive for all learners

Designed to encourage academic integrity

Transparent with clearly communicated expectations

Designed to promote student interaction and collaboration

Supported with intentional technology tools

- Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty (e-book)

- Making Your Course Accessible for All Learners (workshop reccording)

- Writing Multiple Choice Questions that Demand Critical Thinking (article)

Learning Opportunities

Conrad, D., & Openo, J. (2018). Assessment strategies for online learning: Engagement and authenticity . AU Press. Retrieved from https://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b8475002~S7

Gaytan, J., & McEwen, B. C. (2007). Effective online instructional and assessment strategies. American Journal of Distance Education , 21 (3), 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640701341653

Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia learning . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ragupathi, K. (2020). Designing Effective Online Assessments Resource Guide . National University of Singapore. Retrieved from https://www.nus.edu.sg/cdtl/docs/default-source/professional-development-docs/resources/designing-online-assessments.pdf

Robles, M., & Braathen, S. (2002). Online assessment techniques. Delta Pi Epsilon Journal , 44 (1), 39–49. https://proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eft&AN=507795215&site=eds-live&scope=site

Swan, K., Shen, J., & Hiltz, S. R. (2006). Assessment and collaboration in online learning. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks , 10 (1), 45.

TILT Higher Ed. (n.d.). TILT Examples and Resources . Retrieved from https://tilthighered.com/tiltexamplesandresources

Tallent-Runnels, M. K., Thomas, J. A., Lan, W. Y., Cooper, S., Ahern, T. C., Shaw, S. M., & Liu, X. (2006). Teaching Courses Online: A Review of the Research. Review of Educational Research , 76 (1), 93–135. https://www-jstor-org.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/stable/3700584

Walvoord, B. & Anderson, V.J. (2010). Effective Grading : A Tool for Learning and Assessment in College: Vol. 2nd ed . Jossey-Bass. https://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b8585181~S7

Related Teaching Topics

Designing assessments of student learning, strategies and tools for academic integrity in online environments, student interaction online, universal design for learning: planning with all students in mind, related toolsets, carmencanvas, search for resources.

Learning Outcomes 101: A Comprehensive Guide

For those trying to figure out what are learning outcomes, its types, steps, and assessments, this article is for you. Read on to find out more about this guide in developing your teaching strategies.

Table of Contents

Introduction.

In today’s education landscape, learning outcomes play a pivotal role in shaping the educator’s teaching strategies and heralding the academic progress of students. Defining the road map of a learning session, the learning outcomes focus on the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that learners should grasp upon the completion of a course or program.

The relevance and applicability of learning outcomes extend to both the educators and the learners, providing the former with a clear teaching structure and the latter with expectations for their learning.

In the broader sense, understanding these integral aspects of our education system would be incomplete without delving into the types of learning outcomes, elucidating the steps involved in formulating them, exploring their assessment, and shedding light on their impacts and challenges.

Defining Learning Outcomes

What are learning outcomes.

Learning outcomes are statements that describe the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that students should have after completing a learning activity or program. These outcomes articulate what students should know or be able to do as a result of the learning experience. This includes knowledge gained , new skills acquired , a deepened understanding of the subject matter , attitudes and values influenced by learning, as well as changes in behavior that can be applied in specific contexts.

Learning outcomes are statements that describe the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that students should have after completing a learning activity or program.

Learning outcomes are critical in the educational setting because they guide the design of curriculum , instruction, and assessment methods. They are the foundation of a course outline or syllabus, providing clear direction for what will be taught, how it will be taught, and how learning will be assessed. They hold teachers accountable for delivering effective instruction that leads to desired learning outcomes and help students understand what is expected of them, enhancing their learning experience.

Learning outcomes also equip students with transferrable skills and knowledge. They provide a clear description of what the learner can apply in real-world contexts or in their further studies. This makes learning outcomes not only crucial in the academic setting but also in preparing learners for the workforce.

Differentiating Learning Outcomes from Learning Objectives

Learning outcomes and learning objectives are often used interchangeably. However, they have distinct meanings and roles in education.

Learning Objectives

Learning objectives are more teacher-centered and describe what the teacher intends to teach or what the instruction aims to achieve in the scope of a lesson or unit. These may involve specific steps or methodologies used to impart knowledge or skills to the students.

Learning Outcomes

On the other hand, learning outcomes are student-centered and focus on what the student is expected to learn and demonstrate at the end of a learning period. These are usually measurable and observable, making them useful tools for assessing a student’s learning progress and the effectiveness of a lesson or course.

For instance, a learning objective may state, “The teacher will explain the process of photosynthesis.” The associated learning outcome could be, “Students will be able to describe the process of photosynthesis and explain its importance to plant life.”

Examples of Learning Outcomes

Various academic disciplines utilize explicit learning outcomes to provide students with a clear understanding of what they are expected to achieve by the end of a course, unit, or lesson. Here are some examples:

- Mathematics: By the close of the course, students should be capable of solving linear equations and inequalities.

- Science: Upon finishing the module, students will be equipped to accurately elucidate the importance of DNA in genetic inheritance.

- English: Students should be proficient in crafting an organized, eloquent essay that effectively puts forth an argument.

- Social Studies: By the term’s conclusion, students should possess the ability to assess the impacts of World War II from varied perspectives.

- Arts: After completing the lesson, learners should be adept at recreating a piece of art employing learnt techniques, such as watercolor painting.

These specific learning outcomes are instrumental in steering the progress of students throughout their educational journey. They provide key alignment within the education system, ensuring that instructions, learning activities, assessments, and feedback are all constructed around accomplishing these predefined objectives.

3 Types of Learning Outcomes

1. knowledge outcomes.

Knowledge outcomes represent a student’s capacity to remember and comprehend the information and concepts imparted during lessons. These outcomes are usually assessed through examinations or tests, which gauge how well the student has retained the information.

To illustrate, a history student may be tested on their ability to remember specific dates or events, whereas a science student may be required to understand and demonstrate the process of photosynthesis.

This strand of learning outcomes is generally divided into two categories: declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge . Declarative knowledge outcomes evaluate the student’s aptitude to recollect and identify factual information , such as the capital city of a country. In contrast, procedural knowledge outcomes measure the student’s ability to utilize rules and processes fruitfully to solve problems , such as mathematical calculations. Thus, both these subsets form the bedrock of a student’s academic accomplishments.

2. Skill Outcomes

Skill outcomes assess a student’s ability to apply learned theories or concepts within real-world contexts. These are practical skills often developed through hands-on experience and active participation, such as fieldwork or lab experiments. They may also stem from the application of theoretical knowledge to solve practical problems.

For instance, a student studying biology may be required to carry out a dissection as part of their assessments. Similarly, a computer science student might be assessed based on their problem-solving skills using programming languages.

Skill outcomes are commonly split into two categories: generic skills and specific skills . Generic skills are transferable skills that can be used across various fields , such as communication or teamwork skills. Specific skills pertain to specific fields or jobs, such as the ability to use laboratory equipment correctly or the ability to compile code in a specific programming language.

3. Attitudinal Outcomes

When assessing a student’s growth and learning, attitudinal outcomes come into play. These are used to measure a student’s attitudes, values, and beliefs . Given their inherent subjectivity, these outcomes can be a challenge to measure. However, educators utilize various methods such as surveys , reflective journals , and direct observations to evaluate them accurately.

For example, in an ethics course, an attitudinal outcome may include the student’s ability to comprehend, value, and respect different cultural or ethical contexts. Similarly, in an environmental studies course, an outcome could involve evaluating the student’s attitudes towards sustainable practices.

Such outcomes play a significant role in shaping a student’s viewpoint and actions, both in the classroom and beyond. Attitudinal outcomes can reflect changes in attitudes, enhanced appreciation of alternate perspectives, or an inclination to engage with different individuals or groups.

While these outcomes may be more challenging to assess than knowledge or skill-based outcomes, they are imperative for nurturing lifelong learners dedicated to ongoing personal and professional development .

Steps in Formulating Learning Outcomes

1. determine the knowledge, essential skills, and attitude expected.

Once an understanding of knowledge, skills, and attitudinal outcomes is obtained, educators then identify the necessary knowledge, skills and attitude (KSA) that students need to acquire in a specific subject. This stage involves identifying the important competencies and understandings that should be mastered by the end of a course or learning program.

For example, in a mathematics course, core skills that a student may need to develop could include solving linear equations, while key knowledge to be absorbed might involve grasping the principles of calculus.