- Skip to right header navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary navigation

- Skip to footer

Business Continuity and Crisis Management Consultants

9 significant workplace violence incidents from 2019

January 14, 2020 By // by Bryan Strawser

Note : This article covers workplace violence incidents from 2019. For a more up-to-date free briefing on significant workplace violence incidents for the past few years, see our free report on Notable Workplace Violence Incidents , updated annually.

According to the National Safety Council , the fourth leading cause of deaths at work is from assaults. In 2017, there were 18,400 workplace violence incidents involving assault. Of those, 458 people died. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) defines workplace violence as “any threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior” at a work site. Employers, employees and customers alike should be concerned about workplace violence. When someone who is upset with a co-worker or his or her boss, that person may assault anyone in his or her way, including shooting people in their sights.

In order to illustrate how serious workplace violence should be taken within your organization, here are 9 significant workplace violence incidents from 2019.

1. Henry Pratt Shooting, Aurora, Illinois (U.S.)

An industrial warehouse employee , Gary Martin, killed five people and injured one unidentified person and five police officers when he went on a shooting rampage after being fired from his job. Martin had worked at the plant for 15 years. Police stated that they were shot at as soon as they arrived on the scene, which was about 4 minutes after the first 911 calls. All of the fatalities were men. All of the police officers suffered injuries that were not life-threatening. The disgruntled employee was told he was being fired that day. During the meeting, Martin pulled out a gun and started firing and continued shooting as he moved through the plant.

More and more, we hear about people who are fired or laid off shooting up the workplace, whether the firing was the result of the employee’s actions or because of cut-backs or other administrative lay-offs.

About Bryan Strawser

Bryan Strawser is Founder, Principal, and Chief Executive at Bryghtpath LLC, a strategic advisory firm he founded in 2014. He has more than twenty-five years of experience in the areas of, business continuity, disaster recovery, crisis management, enterprise risk, intelligence, and crisis communications.

At Bryghtpath, Bryan leads a team of experts that offer strategic counsel and support to the world’s leading brands, public sector agencies, and nonprofit organizations to strategically navigate uncertainty and disruption.

Learn more about Bryan at this link .

PO Box 131416 Saint Paul, MN 55113 USA

Our Capabilities

- Active Shooter Programs

- Business Continuity as a Service (BCaaS)

- IT Disaster Recovery Consulting

- Resiliency Diagnosis®️

- Crisis Communications

- Global Security Operations Center (GSOC)

- Emergency Planning & Exercises

- Intelligence & Global Security Consulting

- Workplace Violence & Threat Management

Our Free Courses

Active Shooter 101

Business Continuity 101

Crisis Communications 101

Crisis Management 101

Workplace Violence 101

Our Premium Courses

5-Day Business Continuity Accelerator

Communicating in the Critical Moment

Crisis Management Academy®️

Managing Threats Workshop

Preparing for Careers in Resilience

Our Products

After-Action Templates

Business Continuity Plan Templates

Communications & Awareness Collateral Packages

Crisis Plan Templates

Crisis Playbook®

Disaster Recovery Templates

Exercise in a Box®

Exercise in a Day®

Maturity Models

Ready-Made Crisis Plans

Resilience Job Descriptions

Pre-made Processes & Templates

Workplace violence: A nurse tells her story

It’s not okay, and it is a big deal..

By Lillee Gelinas, MSN, RN, CPPS, FAAN

“Personal boundary violation is not part of our job description. That statement is powerful because boundary setting is a part of our job. I believe that if we fail to establish and maintain personal boundaries, then we’ve compromised the safe and therapeutic environment in which we’re able to truly care and advocate for our patients. We have an obligation to stand up against that which is unsafe, and I believe that ending nurse abuse is critical.”

That’s how my conversation began with Karen*, an emergency department (ED) nurse who recently experienced on-the-job violence. I promised her that her story is not over. Nor is the story of thousands of nurses who have been harmed by patients while at work. The importance of the American Nurses Association (ANA) #EndNurseAbuse movement became very real for me the day I spoke with Karen.

Out of the blue

Karen worked as a nurse extern for 4 years, volunteering in the ED and in other settings to get real-world experience before becoming an RN. She’s the type of nurse I try to hire as frequently as I can because she’s enthusiastic about the profession, worked hard to become a nurse, and strives to be the best she can be. But this shining star in the nursing universe has lost some of the glow after her experience.

Out of the blue, a patient hit her hard in the jaw while she was trying to perform an electrocardiogram. The violence was so unexpected that she immediately left the bedside in disbelief. Karen says she was “overwhelmed by my feelings of being hurt.”

Karen says “it’s the aftermath” that’s so important. Being angry with the patient at first is easy, but Karen says, “I can’t stress enough how much this event hurt my feelings, and I’m still not fully over it months later.” The physical injury may have healed, but the emotional injury still stings.

Our role as nurses is to establish a trusting relationship with patients, and when that relationship is compromised after an assault, we may be left with a lasting fear for our personal safety. When you walk into a patient’s room, you enter with a sense of confidence. But this type of event jars that confidence. Getting back to the level of how it felt pre-assault takes a long time and may require long-term support systems that healthcare facilities may not yet have in place.

In addition to ANA’s call to action ( read the American Nurse Today article ), The Joint Commission issued a Sentinel Event Alert to bring more awareness to the seriousness of the issue and outline seven actions every healthcare setting must implement to create safer workplaces. ( Read the alert .)

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 75% of nearly 25,000 workplace assaults reported annually occur in healthcare and social service settings. But we know that number is grossly underreported because only about 30% of nurses report violent incidents. ANA President Pam Cipriano, PhD, RN, NEA-BC, FAAN, states the urgency best: “Abuse is not part of anyone’s job and has no place in healthcare settings. Time’s up for employers who don’t take swift and meaningful action to make the workplace safe for nurses.”

I agree. And Karen agrees. We add the following: It’s not okay, and it is a really big deal.

Lillee Gelinas, MSN, RN, CPPS, FAAN Editor-in-Chief [email protected]

*Name has been changed.

2 Comments .

I was assaulted in 2015 while working inpatient behavioral health. It occurred in an area where there had been previous problems. In order to discredit me and a co-worker who came to my aid, we were fired. I was never given an opportunity to tell my story. I was blamed for the incident and reported to my Board of Nursing. My employer presented falsified documentation and lied. I spent $10,000 and over a year fighting for keep my license (which I eventually did). I suffered a head and neck injury which has caused me permanent difficulty. My four top front teeth and my glasses were broken. Compared to the emotional hell I went through because of my employer and the Board’s “investigation,” my injuries were nothing. Oh, the Board’s investigator had just started her position and was a former associate of my employer. I live in a small state. My employer has a lot of clout and there is little protection for workers in any field. I never felt to alone.

Thank you for the editorial. A similar incident occurred early in my practice while I was performing a bedside cardiac assessment. Shock is probably the best way to describe my initial reaction. I took a step back, rubbed my jaw in disbelief and actually wondered out loud, “Why would you do that?” Many years have come and gone and I no longer remember the answer, as if it could possibly have made any sense. I don’t remember being angry, I felt, if anything a bit foolish that a 100 pound little lady well into her 80s, who was so sweet earlier in the shift, took me off guard, and hit me so squarely with such force. It did, however, make me realize that it was important to be vigilant in assessing the potential for physical violence at ALL times – even from those that might not fit the standard profile. Looking back and having heard many similar stories from my colleagues that resulted in more significant injury (both physical and emotional), I realize that I was fairly lucky to learn such a valuable lesson for no more cost than both a bruised ego and jaw.

Comments are closed.

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Supporting the multi-generational nursing workforce

Vital practitioners

From data to action

It’s All Pro Nursing Team awards season

Many travel nurses opt for temporary assignments because of the autonomy and opportunities − not just the big boost in pay

Effective clinical learning for nursing students

Nurse safety in the era of open notes

Collaboration: The key to patient care success

Health workers fear it’s profits before protection as CDC revisits airborne transmission

Why COVID-19 patients who could most benefit from Paxlovid still aren’t getting it

Human touch

Leadership style matters

My old stethoscope

Nurse referrals to pharmacy

Lived experience

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Vivamus convallis sem tellus, vitae egestas felis vestibule ut.

Error message details.

Reuse Permissions

Request permission to republish or redistribute SHRM content and materials.

Workplace Violence

A study on workplace violence, including how common incidents are, whether employees feel safe at work, and how prepared employees are to respond to incidents.

Read the full report: Workplace Violence 2019

Download the infographic

For more guidance on workplace violence see SHRM's online toolkit:

Understanding Workplace Violence Prevention and Response

Related Content

Rising Demand for Workforce AI Skills Leads to Calls for Upskilling

As artificial intelligence technology continues to develop, the demand for workers with the ability to work alongside and manage AI systems will increase. This means that workers who are not able to adapt and learn these new skills will be left behind in the job market.

Employers Want New Grads with AI Experience, Knowledge

A vast majority of U.S. professionals say students entering the workforce should have experience using AI and be prepared to use it in the workplace, and they expect higher education to play a critical role in that preparation.

Advertisement

Artificial Intelligence in the Workplace

An organization run by AI is not a futuristic concept. Such technology is already a part of many workplaces and will continue to shape the labor market and HR. Here's how employers and employees can successfully manage generative AI and other AI-powered systems.

HR Daily Newsletter

New, trends and analysis, as well as breaking news alerts, to help HR professionals do their jobs better each business day.

Success title

Success caption

Workplace Violence Research

In the 1980’s a series of shootings at post offices drew public attention towards the issue of workplace violence. While mass shootings receive a lot of media attention, they actually account for a small number of workplace violence events . NIOSH has been studying workplace violence since the 1980s. In 1993, NIOSH released the document Preventing Homicide in the Workplace . This was the first NIOSH publication to identify high-risk occupations and workplaces. The research revealed that taxicab establishments had the highest rate of workplace homicide–nearly 40 times the national average and more than three times the rate of liquor stores which had the next highest rate. NIOSH worked to further inform workers and employers about the risk and encourage steps to prevent homicide in the workplace in the 1996 document Violence in the Workplace which reviewed what was known about fatal and nonfatal workplace violence to focus needed research and prevention strategies. The document addressed workplace violence in various settings such as offices, factories, warehouses, hospitals, convenience stores, and taxicabs, and identified risk factors and prevention strategies.

Workplace violence is the act or threat of violence, ranging from verbal abuse to physical assaults directed toward persons at work or on duty. The impact of workplace violence can range from psychological issues to physical injury, or even death. Violence can occur in any workplace and among any type of worker, but the risk for fatal violence is greater for workers in sales, protective services, and transportation, while the risk for nonfatal violence resulting in days away from work is greatest for healthcare and social assistance workers.

There continues to be groups of workers who are disproportionately affected by workplace violence. In 2013, NIOSH researchers contributed to a publication focused on health disparities and inequalities. [i] Number and rates of homicide deaths over a 5-year span for industry and occupation groups were presented by race/ethnicity and nativity. Further analyses published in 2014 in the American Journal of Industrial Medicine controlling for other factors reported elevated homicide rate ratios for workers who are Black, American Indian, Alaska Natives, Asian, or Pacific Islanders, and those who were born outside of the United States.[ii] NIOSH researchers continue to work towards identifying disparities where they exist so we can better focus our research and translation efforts to the workforces and communities of workers that need them. See below for examples of research conducted by NIOSH on identifying disparities in specific workforces.

Health Care

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, U.S. healthcare workers accounted for two-thirds of the nonfatal workplace violence injuries in all industries involving days away from work.[iii] To address the issue of violence in healthcare, in 2002, NIOSH published Violence: Occupational Hazards in Hospitals which discussed prevention strategies in terms of environmental (installing security devices), administrative (staffing patterns), and behavioral (training).

NIOSH and its partners recognized the lack of workplace violence prevention training available to nurses and other healthcare workers. To address this need, in 2013, NIOSH and healthcare partners developed a free on-line course aimed at training nurses in recognizing and preventing workplace violence. This award-winning course, Workplace Violence Prevention for Nurses , has been completed by more than 65,000 healthcare workers. Violence remains an issue for healthcare workers. Home healthcare workers are also at risk for violence as they work closely with patients and often are in close contact with the public while they provide healthcare services to patient. The issue of violence in home healthcare will likely increase as the industry is projected to grow dramatically in the coming years.

Convenience Stores

Robbery-related homicides and assaults are the leading cause of death in retail businesses. In 2019, workers in convenience stores had a 14 times higher rate of deaths due to work-related violence than in private industry overall (6.8 homicides per 100,000 workers vs. 0.48 per 100,000 workers). With these deaths are disparities among the homicide victims. Specifically, Black, Asian, and Hispanic men have disproportionately higher homicide rates than white men. Additionally, foreign-born men have disproportionately higher homicide rates than U.S.-born men, and men 65 and older have disproportionately higher homicide rates than any other age group.[iv]

NIOSH research demonstrated that retail establishments using Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) programs, which suggest that environments can be modified to reduce robberies, experienced 30%–84% decreases in robberies and a 61% decrease in non-fatal injuries. A recent analysis of crime reports spanning 10 years found robbery rates decreased significantly in convenience stores and small retail establishments after a Houston ordinance based on CPTED countermeasures became effective.[v]

Taxicab Drivers

Driving a taxi remains a dangerous job. The most serious workplace violence issues facing taxi drivers are homicide and physical assaults which are often related to a robbery. Deaths due to workplace violence among taxi drivers occur disproportionately among drivers who are men (6 times higher than women), drivers who are Black or Hispanic (double that of drivers who are Non-Hispanic and White), and drivers in the South United States (almost triple that of drivers in Northeast).[vi] NIOSH research evaluated the effect of cameras installed citywide on taxi driver homicide rates in 26 U.S. cities spanning 15 years and found those cities with camera-equipped taxis experienced a 3-fold reduction in driver homicides compared with control cities. [vii] NIOSH and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration together identified prevention measures to reduce the risk of violence including increasing visibility into the taxi, minimizing cash transactions, and security measures such as security cameras, silent alarms, and bullet-resistant barriers. [viii]

Teachers and School Staff

In 2008, NIOSH undertook a large state-wide study to measure physical and non-physical violence directed at teachers and school staff in Pennsylvania. Working with national, state, and local education unions, the study described and quantified physical workplace violence against teachers and school staff and measured the impact of violence on job satisfaction and the mental health of teachers and staff. Some of the most significant findings from that study include:

- Special education teachers were at the highest risk of all teachers and school staff for both physical and nonphysical workplace violence.

- While physical assaults were rare, non-physical violence was not. Over 34% of teachers and school staff had experienced either bullying, threats, verbal abuse, or sexual harassment. Coworkers were the most common source of the violence.

- Both physical and non-physical violence significantly impacted teachers and school workers’ job satisfaction, stress, and quality of life. Those who experienced physical violence were over 2 times more likely to report work as stressful, 2.4 times more likely to report dissatisfaction with their jobs, 11 times more likely to consider leaving the education field and had a higher mean number of poor physical health and mental health days.

- This study highlighted the need for specific prevention efforts and post-event responses that address the risk factors for violence, especially among special education workers. [ix] [x]

Workplace Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Over the last 50 years, NIOSH has seen changes in the risk of workplace violence. The COVID-19 pandemic has presented unique instances of workplace violence. Since the pandemic began in early 2020, U.S. media have reported on retail workers and workers in other industries being verbally assaulted, spit on, and physically attacked while enforcing COVID-19 mitigation practices such as mask wearing or physical distancing. Several international studies have examined violence toward healthcare personnel during the pandemic. Unfortunately, the significant time-lag from the occurrence of these events to data delivery using traditional occupational safety and health surveillance sources means that COVID-19-related workplace violence data will not be available for some time. To address this lag, NIOSH has undertaken multiple studies that used media reports to provide more timely information on the number and characteristics of workplace violence events (WVEs) occurring in U.S. workplaces in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Preliminary results from the unpublished analysis reveal:

- At least 400 WVEs related to COVID-19 were reported in the media between March 1 and October 31, 2020. Twenty-seven percent involved non-physical violence, 27% involved physical violence, and 41% involved both physical and non-physical violence. Non-physical violence is using words, gestures, or actions with the intent of intimidating or frightening an individual and physical violence is any action that leads to physical contact with the intention of injuring such as hitting, kicking, choking, or grabbing.

- A majority occurred in retail and dining establishments and were perpetrated by a customer or client. Most perpetrators were males (59%) and mostly acted alone (79%).

- The majority of COVID-19-related WVEs were due to mask disputes (72%), and 22% involved perpetrators coughing or spitting on workers.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to evolve, employers and employees may have to continue to enforce COVID-19 mitigation policies—which could lead to COVID-19-related WVEs. Clearly, WVEs have impacted industries and occupations differently, especially those requiring workers to be physically present at work during the pandemic. Aside from those noted above, one of the worker groups that has been negatively impacted is public health workers. Other published NIOSH research has found that nearly 12% of state, local, territorial, and tribal public health workers have received job-related threats because of their work, and an additional 23% felt bullied, threatened, or harassed. [xi] While NIOSH has a long history in workplace violence research and prevention, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented unique situations where typical workplace violence prevention strategies may not be effective. NIOSH will continue to conduct research on these events and identify possible prevention strategies to address these unique situations.

This blog is part of a series for the NIOSH 50 th Anniversary. Stay up to date on how we’re celebrating NIOSH’s 50 th Anniversary on our website .

Dawn Castillo, MPH, is the Director of the NIOSH Division of Safety Research.

Cammie Chaumont Menéndez, PhD, MPH, MS, is a Research Epidemiologist in the NIOSH Division of Safety Research.

Dan Hartley, EdD, is the former NIOSH Workplace Violence Prevention Coordinator.

Suzanne Marsh, MPA, is a Team Lead in the NIOSH Division of Safety Research.

Tim Pizatella, MSIE, is the Deputy Director of the NIOSH Division of Safety Research.

Marilyn Ridenour, BSN, MPH, is a Nurse Epidemiologist in the NIOSH Division of Safety Research.

Hope M. Tiesman, PhD, is a Research Epidemiologist in the NIOSH Division of Safety Research.

[i] CDC [2013]. CDC health disparities and inequalities report – United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl 62(3):1-187.

[ii] Steege A, et al. [2014]. Examining occupational health and safety disparities using national data: a cause for continuing concern. Am J of Ind Med 57:527-538.

[iii] BLS [2020]. Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. United States Department of Labor, U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.pdf

[iv] Chaumont Menéndez et al. [2013]. Disparities in work-related homicide rates in selected retail industries in the United States, 2003-2008. J Safety Res 44:25-29.

[v] Davis J, Casteel C, Menendez C [2021]. Impact of a crime prevention ordinance for small retail establishments. Am J Ind Med 64:488-495, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim23239 .

[vi] Menendez C, Socias-Morales C, Daus M [2017]. Work-related violent deaths in the US taxi and limousine industry 2003 to 2013. J Occup Environ Med 59:768-774.

[vii] [vii]Menéndez C, et al. [2013]. Effectiveness of taxicab security equipment in reducing driver homicide rates. Am J Prev Med 45(1):1-8.

[viii] NIOSH/OSHA [2019]. NIOSH fast facts: taxi drivers—how to prevent robbery and violence. By Chaumont Menendez C, Dalsey E. Morgantown, WV: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication 2020-100 (revised 11/2019), https://doi.org/10.26616/NIOSHPUB2020100revised112019. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, DOL (OSHA) Publication No. 3976, https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3976.pdf

[ix] Tiesman H, et al. [2013]. Workplace violence among Pennsylvania education workers: differences among occupations. J Safety Res 44: 65–71.

[x] Konda S, Tiesman HM, Hendricks S, Grubb PL [2020]. Nonphysical workplace violence in a state-based cohort of education workers. J School Health 90: 482-491, https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12897 .

[xi] Bryant-Genevier J, et al. [2021]. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation among state, tribal, local, and territorial public health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, March–April 2021. MMWR 70:947-952.

36 comments on “Workplace Violence Research”

Comments listed below are posted by individuals not associated with CDC, unless otherwise stated. These comments do not represent the official views of CDC, and CDC does not guarantee that any information posted by individuals on this site is correct, and disclaims any liability for any loss or damage resulting from reliance on any such information. Read more about our comment policy » .

Great blog! Thank you for shedding light on this serious problem.

is this study available in pdf. I want to use it as a reference for my master’s thesis. Thank you in advance

Thank you for your comment You asked “is this study available in pdf? ” The blog itself is not available in a PDF. The blog is a summary of various studies, most of which are included in the reference list. Let us know if you need more information on a particular study.

taxicabs are dangerous .

i did not know some these things thanks

awesome possum

the blog is very reliable. thanks for sharing

At this moment any enviroment has become dangerous. We have to be careful.

Thank you for sharing this.

very dangerous

Thanks for all this information.

thank you for that informative article.

thank you for the information

Interesting and have seen more aggressiveness from family members.

Thanks for the info.

Patient population and family members are becoming more demanding, aggressive and non compliant resulting in an increasingly tense/stressful environment. Due to HCAPS scores driving hospital decisions, these behaviors are often times overlooked to maintain patient satisfaction. Hospital staff are receiving the brunt of this bad behavior which is causing a decrease in interest in bedside nursing.

All this is Great information very helpful.

Even though I usually have good patients ,is true that patients and family members are more demanding.

unfortunately this is nursing environment , stay safe!!

Violence should never be considered part of a typical work environment. NIOSH and its partners are working to address issues related to violence in health care. For example, the creation of the online training Workplace Violence Prevention for Nurses that was referenced in this blog.

Thanks for the information it was very interesting .

Thanks for the information.

Thank you for this helpful Information .

Thanks for make us aware about a good practices on the work place.

This was great. very insightful and helpful

informative, thanks

This information is always good to know, Thank you !

Imformative Thanks

very educational article

Do you have any statistics on workplace violence in longterm care?

Thank you for your comment. This paper published from the Ohio Bureau of Workers Compensation briefly covers workplace violence in skilled nursing.

From the publicly available data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses for 2021-2022, the number of nonfatal injuries associated with ‘intentional injury by other person’ were as follows ( see table for more information): • ‘skilled nursing facilities’ = 3,060 cases with days away from work (DAFW) • ‘residential intellectual and developmental disability, mental health, and substance abuse facilities’ = 4,900 cases with DAFW • ‘continuing care retirement communities and assisted living facilities for the elderly’ = 1,410 cases with DAFW

Data for comparison purposes can be extracted from the table that these numbers were extracted from.

According to the publicly available BLS Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) data for 2022 ( see table for more information), the number of fatalities associated with ‘violence and other injuries by persons or animals’ was not reportable. Please note that this doesn’t mean that there were no fatalities associated with violence but that the number did not meet BLS reporting requirements.

This is a great article. Thanks for providing more insight on this topic.

Very Informative

Post a Comment

Cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- 50th Anniversary Blog Series

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aging Workers

- Agriculture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Back Injury

- Bloodborne pathogens

- Cardiovascular Disease

- cold stress

- commercial fishing

- Communication

- Construction

- Cross Cultural Communication

- Dermal Exposure

- Education and Research Centers

- Electrical Safety

- Emergency Response/Public Sector

- Engineering Control

- Environment/Green Jobs

- Epidemiology

- Fire Fighting

- Food Service

- Future of Work and OSH

- Healthy Work Design

- Hearing Loss

- Heat Stress

- Holiday Themes

- Hydraulic Fracturing

- Infectious Disease Resources

- International

- Landscaping

- Law Enforcement

- Manufacturing

- Manufacturing Mondays Series

- Mental Health

- Motor Vehicle Safety

- Musculoskeletal Disorders

- Nanotechnology

- National Occupational Research Agenda

- Needlestick Prevention

- NIOSH-funded Research

- Nonstandard Work Arrangements

- Observances

- Occupational Health Equity

- Oil and Gas

- Outdoor Work

- Partnership

- Personal Protective Equipment

- Physical activity

- Policy and Programs

- Prevention Through Design

- Prioritizing Research

- Reproductive Health

- Research to practice r2p

- Researcher Spotlights

- Respirators

- Respiratory Health

- Risk Assessment

- Safety and Health Data

- Service Sector

- Small Business

- Social Determinants of Health

- Spanish translations

- Sports and Entertainment

- Strategic Foresight

- Struck-by injuries

- Student Training

- Substance Use Disorder

- Surveillance

- Synthetic Biology

- Systematic review

- Take Home Exposures

- Teachers/School Workers

- Temporary/Contingent Workers

- Total Worker Health

- Translations (other than Spanish)

- Transportation

- Uncategorized

- Veterinarians

- Wearable Technologies

- Wholesale and Retail Trade

- Work Schedules

- Workers' Compensation

- Workplace Medical Mystery

- Workplace Supported Recovery

- World Trade Center Health Program

- Young Workers

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Jennifer Kramer

- Brandon Ruiz

- Shoshee Hui

- Dat T. Phan

- Courtney Luengo

- Veronica Gomez

- Employment Law

- Sexual Harassment

- Age Discrimination

- Disability & ADA Compliance

- Gender Discrimination

- Pregnancy & FMLA

- Race & National Origin

- Religious Discrimination

- Sexual Orientation & Gender Identification

- Wrongful Termination

- Retaliation

- Contract Workers Rights

- Minimum Wage

- Salary Hourly Classification

- Wage & Hour Class Action

- Civil Right Federal Subsection 1983

- Qui Tam Government Contract Fraud

- Pharmaceutical Sales

- Refuser Cases

- Privacy Rights

- Claims By Public Entity Employees

- In The News

- Case Results

True Stories of Workplace Bullying: Case Examples to Help You Understand Your Rights

Do you think you’re being bullied at work? If so, your workplace bully could be violating California and Federal law due to their harassing behaviors. While bullying itself is not unlawful, there are anti-bullying legislative measures being brought to the forefront all across the country, including the Healthy Workplace Bill. In addition to anti-bullying legislation, the Workplace Bullying Institute is also striving to eradicate bullying on the job by dedicating their efforts to anti-bullying education, research, and consulting for individuals, professionals, employers, and organizations.

Workplace bullying comes in many forms and can be unlawful if this type of harassment is based on an employee’s national origin, age, gender, disability, or other protected characteristics. Bullies also typically engage in these unlawful behaviors more than once rather than in isolated incidents.

In the spirit of the Workplace Bullying Institute’s Freedom from Workplace Bullies Week, we’ve decided to offer some insight into real workplace bullying, retaliation and discrimination cases from around the country that can help you understand your own rights when it comes to employment harassment.

Real Workplace Bullying Case Examples

Microsoft to pay $2 million in workplace bullying case.

AUSTIN, TX – After seven years, Michael Mercieca finally saw the courts order Microsoft to pay for workplace bullying that almost led him to the breaking point.

The Texas employment labor law case judge, Tim Sulak, found Microsoft guilty of “acting with malice and reckless indifference” in an organized program of office retaliation against Mercieca.

“They (Microsoft Corporation) remain guilty today, tomorrow and in perpetuity over egregious acts against me and racist comments by their executive that led to the retaliation and vendetta resulting in my firing,” said Mercieca.

Previously, a jury, by unanimous agreement, found that Microsoft knowingly created a hostile work environment that led to Mercieca’s constructive dismissal. Mercieca was a highly regarded member of the tech giant’s sales department and had an unblemished record, but found himself trapped in a workplace conspiracy where his supervisors and coworkers undermined his work, falsely accused him of sexual harassment, and expense account fraud, marginalized him, and blocked his promotions. These harassing behaviors began when Mercieca ended a relationship with a woman who then went on to become his boss. Human relations at Microsoft did nothing to stop the bullying, either.

“Rather than do the right thing, the management team went after Michael by getting a female employee to file a sexual harassment complaint and a complaint of retaliation against him,” says Paul T. Morin. “Microsoft could have taken Mercieca’s charges seriously and disciplined the senior manager but instead it engaged in the worst kind of corporate bullying.”

Read the full story

King Soopers to Pay $80,000 to Settle EEOC Disability Discrimination Lawsuit

DENVER, CO – Dillon Companies, Inc., owners of the King Soopers supermarket chain in Colorado will pay $80,000 for bullying a learning-disabled employee who worked at its Lakewood, Colorado store.

According to the EEOC’s disability discrimination lawsuit, two store supervisors repeatedly subjected Justin Stringer, an employee who worked at King Soopers for a decade, to repeated bullying and taunting in the workplace because of his learning disability. The EEOC alleged that the bullying resulted in Stringer’s termination.

“Employees with disabilities must be treated with the same dignity and respect as all other members of the work force,” said EEOC Regional Attorney Mary Jo O’Neill. “The EEOC will continue to enforce the ADA to protect the rights of disabled employees and applicants.”

DHL Global Forwarding Pays $201,000 to Settle EEOC National Origin Discrimination Suit

DALLAS, TX – Air Express International, USA, Inc. and Danzas Corporation, doing business as DHL Global Forwarding, will pay $201,000 to nine employees and provide other significant relief to settle a national origin hostile environment lawsuit brought by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

The EEOC charged DHL Global with subjecting a class of Hispanic employees to bullying, discrimination, and harassment due to their national origin. According to the suit, Hispanic employees at DHL’s Dallas warehouse were bullied at work by being subjected to taunts and derogatory names such as “wetback,” “beaner,” “stupid Mexican” and “Puerto Rican b-h”. The Hispanic workers, who included persons of Mexican, Salvadoran and Puerto Rican heritage, were often ridiculed by DHL personnel with demeaning slurs which included referring to the Salvadoran worker as a “salvatrucha,” a term referring to a gangster. Other workers were identified with other derogatory stereotypes.

Robert A. Canino, regional attorney for the EEOC’s Dallas District Office, stated, “Bullying Hispanic workers for speaking a language other than English is a distinct form of discrimination, which, when coupled with ethnic slurs, is clearly motivated by prejudice and national origin animus. Sometimes job discrimination isn’t just about hiring, firing or promotion; it’s about an employer promoting disharmony and disrespect through an unhealthy work environment.”

Wal-Mart to Pay $150,000 to Settle EEOC Age and Disability Discrimination Suit

DALLAS, TX – Wal-Mart Stores of Texas, L.L.C. (Wal-Mart) has agreed to pay $150,000 and provide other significant relief to settle an age and disability discrimination lawsuit brought by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The EEOC charged in its suit that Wal-Mart discriminated against the manager of the Keller, Texas Walmart store by subjecting him to bullying, harassment, discriminatory treatment, and discharge because of his age.

According to the EEOC, David Moorman was ridiculed with frequent bullying and taunts at work from his direct supervisor, including being called “old man” and “old food guy.” The EEOC also alleged that Wal-Mart fired Moorman because of his age.

“Mr. Moorman was subjected to taunts and bullying from his supervisor that made his working conditions intolerable,” said EEOC Senior Trial Attorney Joel Clark. “The EEOC remains committed to prosecuting the rights of workers through litigation in federal court.”

Under the terms of the two-year consent decree settling the case, Wal-Mart will pay $150,000 in relief to Moorman under the terms of the two-year consent decree. Wal-Mart also agreed to provide training for employees on the ADA and the ADEA, which will include an instruction on the kind of conduct that could constitute unlawful discrimination or harassment.

Everyone deserves to work in a safe, supportive environment and workplace bullies should be dealt with accordingly. If you are being bullied at work, contact our expert California employment lawyers today for your free consultation.

Recent Posts

Schedule a free case evaluation.

Fields Marked With An * Are Required

" * " indicates required fields

more than 25 years of experience

Trusted counsel when you need it most.

- Practice Areas

Local Office

3600 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 1908 Los Angeles, CA 90010

Copyright © 2024 Hennig Kramer Ruiz & Singh, LLP . All rights reserved.

- Open access

- Published: 13 October 2023

Contemporary evidence of workplace violence against the primary healthcare workforce worldwide: a systematic review

- Hanizah Mohd Yusoff 1 ,

- Hanis Ahmad ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6657-8698 1 ,

- Halim Ismail 1 ,

- Naiemy Reffin 1 ,

- David Chan 1 ,

- Faridah Kusnin 2 ,

- Nazaruddin Bahari 2 ,

- Hafiz Baharudin 1 ,

- Azila Aris 1 ,

- Huam Zhe Shen 1 &

- Maisarah Abdul Rahman 3

Human Resources for Health volume 21 , Article number: 82 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3274 Accesses

1 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Violence against healthcare workers recently became a growing public health concern and has been intensively investigated, particularly in the tertiary setting. Nevertheless, little is known of workplace violence against healthcare workers in the primary setting. Given the nature of primary healthcare, which delivers essential healthcare services to the community, many primary healthcare workers are vulnerable to violent events. Since the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978, the number of epidemiological studies on workplace violence against primary healthcare workers has increased globally. Nevertheless, a comprehensive review summarising the significant results from previous studies has not been published. Thus, this systematic review was conducted to collect and analyse recent evidence from previous workplace violence studies in primary healthcare settings. Eligible articles published in 2013–2023 were searched from the Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed literature databases. Of 23 included studies, 16 were quantitative, four were qualitative, and three were mixed method. The extracted information was analysed and grouped into four main themes: prevalence and typology, predisposing factors, implications, and coping mechanisms or preventive measures. The prevalence of violence ranged from 45.6% to 90%. The most commonly reported form of violence was verbal abuse (46.9–90.3%), while the least commonly reported was sexual assault (2–17%). Most primary healthcare workers were at higher risk of patient- and family-perpetrated violence (Type II). Three sub-themes of predisposing factors were identified: individual factors (victims’ and perpetrators’ characteristics), community or geographical factors, and workplace factors. There were considerable negative consequences of violence on both the victims and organisations. Under-reporting remained the key issue, which was mainly due to the negative perception of the effectiveness of existing workplace policies for managing violence. Workplace violence is a complex issue that indicates a need for more serious consideration of a resolution on par with that in other healthcare settings. Several research gaps and limitations require additional rigorous analytical and interventional research. Information pertaining to violent events must be comprehensively collected to delineate the complete scope of the issue and formulate prevention strategies based on potentially modifiable risk factors to minimise the negative implications caused by workplace violence.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Events where healthcare workers (HCWs) are attacked, threatened, or abused during work-related situations and that present a direct or indirect threat to their security and well-being are referred to as workplace violence (WPV) [ 1 ]. Violence in the health sector has increased over the last decade and is a primary global concern [ 2 ]. Recent statistical data demonstrated that HCWs were five times more likely to experience violence than workers in other sectors and are involved in 73% of all nonfatal violent work incidents [ 3 ]. The experience of WPV is linked to reduced quality of life and negative psychological implications, such as low self-esteem, increased anxiety, and stress [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. WPV is often linked to poor work performance caused by lower job satisfaction, higher absenteeism, and reduced worker retention [ 7 , 8 ], which may disrupt patient care quality and other healthcare service productivity [ 9 ]. Decision-makers and academics worldwide now recognise the seriousness of WPV in the health sector, which has been extensively examined in tertiary settings, particularly emergency and psychiatric departments. Nonetheless, understanding of WPV in primary healthcare (PHC) settings is minimal.

The modern health system has experienced a fundamental shift in delivery systems while moving towards universal health coverage and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [ 7 ]. Despite the focus on tertiary-level individual disease management, the healthcare system recently moved towards empowering primary-level patient and community health needs [ 10 ]. Robust PHC system delivery provides deinstitutionalised patient care, which includes health promotion, acute disease management, rehabilitation, and palliative services, via primary health units in the community, which are referred to with different terms across countries, such as family health units, family medicine and community centres, and outpatient physician clinics [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. In developing and developed countries, PHC services are associated with improved accessibility, improved health conditions, reduced hospitalisation rates, and fewer emergency department visits [ 14 ]. The backbone of this health system delivery is a PHC team of family physicians, physician assistants, nurses, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, social workers, administrative staff, auxiliaries, and community workers [ 15 ].

Nevertheless, the nature of PHC service, which delivers essential services to the community, requires direct interaction with patients and family members, thus increasing the likelihood of experiencing violent behaviour [ 10 ]. Understaffing occurs mainly due to the lack of comprehensive national data that could offer a complete view of the PHC workforce constitution and distribution, which results in increased responsibilities and compromised patient communication [ 15 ]. Considering the current worldwide employment patterns, a shortage of approximately 14.5 million health workers in 2030 is anticipated based on the threshold of human resource needs related to the SDG health targets [ 16 ]. Other challenges at the PHC level recently have also been addressed, including long waiting times, dissatisfaction with referral systems, high burnout rates, and limited accessibility in rural areas, which exacerbate existing WPV issues [ 14 ].

As PHC system quality relies entirely on its workers, the issue of WPV requires more attention. WPV issues must be examined separately between PHC and other clinical settings to support an effective violence prevention strategy for PHC, given that the violence characteristics and other relevant factors can vary by facility type. In addition, PHC workers also have distinct services, work tasks, and work environments [ 11 ]. Since the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978, interest in conducting empirical studies investigating WPV in the PHC setting has increased worldwide [ 17 ]. Nevertheless, a comprehensive systematic review summarising the results from previous studies has never been published. Understanding this issue among workers who serve under a robust PHC system would be equally essential and requires attention to critical dimensions on par with WPV incidents in other clinical settings, especially hospitals. Therefore, this preliminary systematic review of WPV against the PHC workforce analysed and summarised the current information, including the WPV prevalence, predisposing factors, implications, and preventive measures in previous research.

Literature sources

This systematic review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 review protocol [ 18 ]. A comprehensive database search of the Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed databases was conducted in February 2023 using key terms related to WPV (“violence”, “harassment”, “abuse”, “conflict”, “confrontation”, and “assault”), workplace setting (“primary healthcare”, “primary care”, “community unit”, “family care”, “general practice”), and victims (“healthcare personnel”, “healthcare provider”, “medical staff”, “healthcare worker”). The keywords were combined using advanced field code searching (TITLE–ABS–KEY), phrase searching, truncation, and the Boolean operators “OR” and “AND”.

Eligibility criteria

All selected studies were original articles written in English and published within the last 10 years (2013–2023) on optimal sources or current literature. The articles were selected based on the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Described all violence typology (Types I–IV) and its form (verbal abuse, physical assault, physical threat, racism, bullying, or sexual assault);

The topic of interest concerned every category of PHC personnel (family doctor, general practitioner, nurse, pharmacist, administrative staff).

Exclusion criteria

The violence occurred in a tertiary or secondary setting (during training/industrial attachment at a hospital);

Case reports or series, and technical notes.

Study selection and data extraction

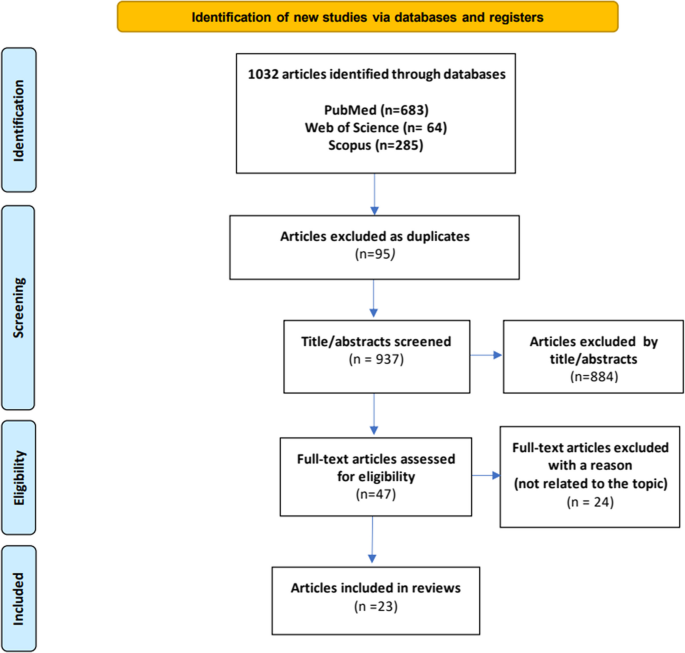

All research team members were involved in screening the titles and abstracts of all articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All potentially eligible articles were retained to evaluate the full text, which was conducted interchangeably by two teams of four members. Differences in opinion were resolved with the research team leader’s input. Before the data extraction and analysis, the methodological quality of the finalised article was assessed using the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Based on the outcomes of interest, the information obtained from the included articles was compiled in Excel and grouped into the following categories: (i) prevalence, typology, and form of violence, (ii) predisposing factors, (iii) implications, and (iv) preventive measures. Figure 1 depicts the article selection process flow.

PRISMA flow diagram

General characteristics of the studies

Forty-three articles were potentially eligible for further consideration, but only 23 articles provided information that answered the research questions (Table 1 ) [ 13 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. The studies mainly covered 16 countries across Asia, Europe, and North and South America, thus providing good ethnic or cultural background diversity. All included articles were observational studies. Sixteen studies were quantitative descriptive studies conducted through self-administered surveys using different validated local versions of WPV study tools (response rate: 59–94.47%). Four qualitative studies collected data through in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. The remaining studies were mixed-method studies that combined quantitative and qualitative research elements. Of the 23 studies, 15 involved various categories of healthcare personnel, seven involved primary clinicians, and one involved pharmacist.

Prevalence, typology, and form of violence

14 studies focused on the prevalence of patient- or family-perpetrated violence (Type II), three studies focused on co-worker-perpetrated violence (Type III), while six studies reported on both type II and III violence (Table 2 ). Evidence of domestic- and crime-type violence (Types I and IV) was not found in the literature. In most studies, the primary outcome was determined based on recall incidents over the previous 12 months. The reported prevalence of violence against was 45.6–90%. The incidence rate of verbal abuse was 46.9–90.3%, which rendered it the most commonly identified form of violence, followed by threats or assault (13–44%), bullying (19–27%), physical assault (15.9–20.6%), and sexual harassment (2–17%). The reported prevalence of violence against doctors was 14.0–73.0%, followed by that against nurses (6.0–48.5%), pharmacists (61.8%), and others (from 40% to < 5%). Patients and their families were the main perpetrators of violence, followed by co-workers or supervisors (Table 2 ).

Predisposing factors of WPV

Victims’ personal characteristics

Several socio-demographic factors were identified as predictors of WPV. Male gender and female gender were associated with risk of physical violence [ 21 , 22 , 23 ] and non-physical violence [ 12 , 19 , 24 , 32 , 35 , 39 ], respectively. Nevertheless, a specific form of non-physical violence, such as coercion, was also reported less frequently among women [ 34 ]. A minority group of HCWs with individual sexual identities perceived a severe form of intra-profession violence, such as threats to their licenses [ 24 ]. Being young presented a higher risk for violence, especially sexual harassment, and was frequently complicated by physical injury [ 23 , 27 , 34 ]. A personality trait study demonstrated a significant association between aggression incidents with “reserved” and “careless” personality types [ 20 ]. Regarding professional background, medical workers were more vulnerable to physical violence compared to non-medical workers [ 12 , 22 , 34 ]. Nurses faced a higher risk of WPV than others [ 19 , 23 , 27 , 37 ]. Nevertheless, non-medical staff were also vulnerable to physical violence [ 35 ]. Due to less work experience, certain HCWs were identified as vulnerable to violence [ 22 , 26 , 35 ]. Furthermore, violent clinic incidents could occur due to poor professional–client relationships triggered by workers’ attitudes, such as a lack of communication and problem-solving skills [ 25 , 26 ] (Table 3 ).

Perpetrators’ personal characteristics

Patients and their family members mainly triggered WPV, and some exhibited aggressive behaviours, such as psychiatric disorders or drug influence [ 20 , 23 , 28 ]. Female patients in a particular age group were noted as being at risk of causing both physical and non-physical violence [ 34 ]. WPV was also prevalent in clinics, which was attributable to poor patient–professional relationships triggered by the perpetrator’s inappropriate attitude, such as being excessively demanding, or when clients did not fully understand the role of HCWs or used PHC services for malingering [ 25 , 26 , 31 ] (Table 3 ).

Community/Geographical factors

We identified the role of the local community, where WPV was prevalent among HCWs who served at PHC facilities in drug trafficking areas [ 27 ] and that were surrounded by a population of lower socio-economic status [ 28 ]. Furthermore, WPV was increased in clinics in urban and larger districts, which have a lower HCW density per a given population compared to the national threshold of human resource requirement [ 29 , 32 , 39 ], whereas WPV reduced in rural areas, where medical service was perceived more accessible due to lower population density [ 39 ] (Table 3 ).

Workplace factors

The operational service, healthcare system delivery, and organisational factors were identified as the three major sub-themes of work-related predictors of WPV. Specific operational services increased the likelihood of WPV, for example, during home visit activities, handling preschool students, dealing with clients at the counter, and triaging emergency cases [ 27 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. WPV was more prevalent if the service was delivered by HCWs who worked extra hours with multiple shifts, particularly during the evening and night shifts [ 30 , 36 , 37 , 39 ]. HCWs who worked in clinics with poor healthcare delivery systems due to ineffective appointment systems, uncertainty of service or waiting times, and inadequate staffing [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 37 ] faced higher potential exposure to aggressive events compared to those working in clinics with better systems. WPV was also linked to a lack of organisational support, mainly in fulfilling workers’ needs, such as providing sufficient human resources, capital, and on-job training, or equal pay schedule and job task distribution, or ensuring a safety climate and clear policy for WPV management [ 22 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. We also determined that the lack of a multidisciplinary work team and devalued family medicine speciality by other specialists caused many HCWs to remain in poor intra- or inter-profession relationships and be vulnerable to co-worker-perpetrated incidents in PHC settings [ 24 , 26 , 33 , 39 ] (Table 3 ).

Effects of WPV

The most frequently reported implications by the victims of WPV involved their professional life, where most studies mentioned reduced performance, absenteeism, the decision to change practice, and feeling dissatisfied or overlooked in their roles. This was followed by poor psychological well-being (anxiety, stress, or burnout), and emotional effects (feeling guilty, ashamed, and punished) [ 13 , 21 , 24 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 38 ]. Three studies reported on physical injuries [ 13 , 21 , 34 ], while only one study reported a deficit in victims’ cognitive function, which might lead to near-miss events involving patients’ safety elements, and social function defects, where some victims refused to deal with patients in the future [ 31 ]. Only one study reported the WPV implication of being environmentally damaged [ 34 ] (Table 3 ).

Victims’ coping mechanisms and organisational interventions

The coping strategies adopted by HCWs varied depending on the timing of the violent events. Safety approaches such as carrying a personal alarm, bearing a chevron, and other similar steps were used, especially by female HCWs, as a proactive coping measure against potentially hazardous incidents [ 21 ]. “During an aggressive situation triggered by patients, certain workers used non-technical skills, which included leadership, task management, situational awareness, and decision-making [ 31 ]. During inter-professional conflict (physician–nurse conflict), the most predominant conflict resolution styles were compromise and avoiding, followed by accommodating, collaborating, and competing [ 40 ]. Avoiding conflict resolution was most common among nurses, whereas compromise was most common among doctors [ 40 ]. Post-violent event, most HCWs chose to take no action, while some utilised a formal reporting channel either via their supervisors, higher managers, police officers, or legal prosecution. Some HCWs also utilised informal channels by sharing problems with their social network members, such as colleagues, friends, or family members [ 13 , 30 , 36 , 39 ]. Only one article mentioned health managers’ organisational preventive interventions, which included internal workplace rotation, staff replacement, and writing formal explanation letters [ 34 ] (Table 3 ).

We analysed the global prevalence and other vital information on WPV against HCWs who serve in the PHC setting. We identified noteworthy findings not reported in earlier systematic reviews and meta-analyses, where the healthcare setting type was not taken into primary consideration [ 2 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ].

Determining a definite judgement on WPV incidence against PHC workers worldwide is challenging, given that several of the studies selected for analysis were conducted using convenience sampling with low response rates. Nevertheless, notable results were obtained. WPV prevalence varied significantly, where the highest prevalence was reported in Germany (91%) and the lowest was reported in China (14%). Based on the average 1-year prevalence rate of WPV, we determined that the European and American regions had a greater WPV prevalence than others, which was consistent with a recent meta-analysis [ 50 ]. One reason might be the more effective reporting system in these regions, which facilitate more reports through a formal channel, as mentioned previously [ 51 ]. Contrastingly, opposite circumstances might cause WPV events to go unreported in other parts of the world. We also revealed a need for more evidence on WPV in the PHC context in Southeast–East Asia and African regions. The number of peer-reviewed articles from these regions could have been much higher, which inferred that the issue in these continents still requires resolution.

Various incidents of violence, including those of a criminal or domestic nature, commonly occur in the tertiary setting. The Healthcare Crime Survey by the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS) reported that within a 10-year period (2010–2022), the number of hospital workers who experienced ten types of crime-related events in the workplace, such as murder, rape, robbery, burglary, theft (Type I), increased by the year [ 52 ]. In contrast, most studies conducted in PHC settings focused on providing more evidence of Type II violence, whereby other types (I and IV) were rarely detected. The scarcity of evidence does not necessarily indicate that PHC workers are not vulnerable to criminal or domestic violence. Rather, it implies that WPV is still not entirely explored in the PHC setting, which undermines the establishment of a comprehensive violence prevention strategy that encompasses all types of violence [ 53 ].

Hospital-based studies reported diverse forms of violence, where both physical and verbal violence were dominant [ 47 , 54 , 55 , 56 ]. Violence as a whole and physical violence in particular tend to occur in nursing homes and certain hospital departments, such as the psychiatric department, emergency rooms, and geriatric nursing units [ 47 , 55 , 56 ]. Volatile individuals with serious medical conditions or psychiatric issues or who are under the influence of drugs or alcohol were mainly responsible for this severe physical aggression [ 53 ]. Similar to previous hospital-based studies, diverse forms of violence (verbal abuse, physical attacks, bullying, sexual-based violence, psychological abuse) were recorded in PHC settings. Despite this, most of the studies determined that the perpetrators’ disparate characteristics resulted in more frequent documentation of verbal violence than physical violence. Dissatisfied patients or family members were more likely to perpetrate greater incidents of verbal abuse [ 25 , 26 , 31 ], either due to their medical conditions or dissatisfaction with the services provided [ 30 ]. This noteworthy discovery prompted new ideas, indicating that variance in the form of violence might also be determined by the healthcare setting role [ 57 ].

Our findings demonstrated that sexual-based violence was the least frequently documented form of violence, with a regional differences pattern indicating relatively lower sexual-based violence reporting in the Middle Eastern region [ 13 , 30 ]. This result contrasted with a previous systematic review of African countries that reported that sexual-based violence was one of the dominant forms of WPV. This lower incidence was possibly due to under-reporting by female employees who were reluctant to report sexual harassment aggravated by cultural sensitivities regarding sexual assault exposure [ 58 ]. Such culturally driven decision-making practices are worrying, as they could lead to underestimation of the true extent of the issues and cause more humiliating incidents and the lack of a proper response.

We identified considerable numbers of significant predisposing factors, which were determined via advanced multivariate modelling. Most factors were comparable with that in previous WPV research, especially those related to the victims’ individual socio-demographic and professional backgrounds [ 2 , 41 , 42 ]. Several studies consistently reported that nurses were vulnerable to WPV compared to physicians and others, which was supported by numerous prior systematic studies [ 19 , 23 , 27 , 37 ]. This could be explained by the accessible nature of nurses as healthcare professionals to patients and families [ 50 ]. Furthermore, nurses interact first-hand with clients during treatment, rendering them more likely to become the initial victims of WPV before others. Nevertheless, this result should not necessarily suggest that other professions are not at risk for violence. Due to the shortage of evidence regarding the remaining category of PHC workers, it is impossible to provide a more conclusive and realistic assessment of the above.

The results demonstrated that many PHC clinics were built in community areas with a variety of settings, such as high-density commercial developments in urban or rural areas, resource-limited locations, or areas with a high crime concentration [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 32 , 39 ]. Therefore, an additional new sub-theme under predisposing factors, namely, “community and geographical factors”, was created to include all evidence on the relationship between WPV vulnerability and community social character and geo-spatial factors. Although several hospital-based studies deemed this topic less significant, several studies in the present review that examined the relationship between geographic information and the surrounding population characteristics with WPV reported valuable and constructive information for PHC prevention framework efforts.

In general, we identified a similar correlation between work-related factors and WPV as in hospital-based studies, particularly on healthcare system delivery and organisational support elements [ 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ]. Nonetheless, the evidence on operational service was vastly distinct. As several PHC services are expanded outside facilities, there is increased potential for violence against HCWs when they provide out of clinic services, for example, during home visits and school health services [ 21 , 37 , 39 ]. Such situations might require more comprehensive prevention measures compared to violent events that occur within health facilities. Unfortunately, the available literature that describes and assesses the safety elements of HCWs in PHC settings mainly focused on services inside the health facilities, indicating that WPV prevention and management should be expanded to outdoor services [ 21 ].

The studies included in this review comprehensively described the observed implications on WPV victims in PHC settings. Nonetheless, additional vital information on the adverse effects on organisational elements remains lacking, especially regarding the quality of patient care involving potential near-miss events, negligence, and reduced safety elements [ 31 ]. The economic effect is another important aspect that requires further consideration. Recent financial expense data were only available from hospital-based research. A systematic review revealed that WPV events resulting in 3757 days of absence at one hospital over 1–3 years involved a cost exceeding USD 1.3 billion that was mainly due to reduced productivity [ 43 ].

The magnitude of under-reporting among HCWs was concerning, as most respondents admitted that they declined to report WPV cases through formal reporting channels, such as via electronic notification systems, supervisors, or police officers [ 13 , 30 , 36 , 39 ]. Although the included articles mentioned several impediments to reporting, such as fear of retaliation, fear of missing one’s job, and feelings of regret and humiliation, [ 13 , 30 , 36 ], the main reason for under-reporting was a lack of trust in existing WPV preventive institutional policies. Most respondents perceived that reporting the case would not lead to positive changes and were dissatisfied with how the policy was administered [ 13 , 30 ]. Despite much evidence on proactive coping mechanisms utilised by the HCWs, which were either behaviour change technique or conflict resolution style, we did not obtain additional crucial information on existing regional WPV policies or specific intervention frameworks at institutional level [ 31 , 40 ]. Furthermore, reports of the mediating functions of federal- or state-level central funding and legal acts or regulatory support in establishing effective regional violence policies were also absent in primary settings. Further discussion in this area is crucial as significant federal or state government support would improve HCWs’ perceptions of regional prevention program and would potentially reduce the rate of violence against HCWs.

Opportunities for future research

Only a few studies discussing WPV in the PHC setting have been published over the 10 years covered in this review. Local researchers and stakeholders should define and prioritise important areas of study. Given the heterogeneity of the forms of violence, it might be advantageous to conduct additional observational research in the future to describe the situation and investigate the associations between the rate of violence and its multiple predictors using Poisson regression analysis [ 59 ]. At the present stage, quasi-experimental evidence is ambitious. Therefore, more longitudinal studies are required to evaluate the efficacy of any newly introduced violence prevention and management measures designed in primary healthcare settings [ 60 ].

A comprehensive investigation of WPV occurrences beyond Type II violence is required to accurately reflect the breadth of the issue and focus on prevention efforts. In the present study, the association pattern between the consequences of WPV for specific perpetrators was not investigated as in prior research due to the scarcity of evidence on Type I, III, and IV violence. For example, Nowrouzi-Kia et al. revealed that the victims of inter-professional perpetuation (Type III) experienced more severe consequences involving their professional life (low job satisfaction, increased intention to quit) than those who experienced patient or family-perpetrated violence (Type II), which involved psychological and emotional changes [ 61 , 62 ]. In addition, the study scope must also be expanded to include assaults against both healthcare personnel and patients in primary settings. A hospital-based investigation by Staggs 2015 revealed a significant association between the number of staff at psychiatric patient units and the frequency of violent incidents. Surprisingly, this rigorous investigation determined that higher levels of hospital staffing of registered nurses were associated with a higher assault rate against hospital staff and a lower assault rate against patients [ 63 ].

Despite universal exposure to WPV, the incidence rates and types of violence vary between regions. Thus, the primary investigation focus should be tailored to specific violence issues in a particular setting. Our results highlighted the need for further research into strengthening WPV policy, particularly concerning the reporting systems in regions outside European and American countries. Compared to other regions, local academicians in Southeast Asia and Africa are encouraged to increase their efforts to perform more epidemiological WPV studies in the future to better understand the WPV issue. It is crucial to identify the underlying causes of low prevalence of sexual harassment, particularly in the Middle East, which might be caused by under-reporting influenced by culture or gender bias. Although it is asserted that sexual-based violence is likely to occur commonly in cultures that foster beliefs of perceived male superiority and female social and cultural inferiority, the reported prevalence rate of such violence in certain regions [ 64 ], particularly in the Middle East, was low, possibly due to under-reporting. Thus, to address this persistent problem, the existing reporting mechanisms must be improved and sexual-based violence should be distinguished from other forms of violence to encourage more case reporting. Simultaneously, sexual-based violence should also be defined differently across countries and various social and cultural contexts to reduce impediments to reporting [ 64 ].

In existing studies, the main focus of work-related predisposing factors is based on superficial situational analysis, which is identified using the local version of the standard WPV instrument tool via a quantitative approach. Nevertheless, this weak evidence would not support a more effective preventive WPV framework. This issue should be addressed in more depth and involve psychosocial workplace elements that cover interpersonal interactions at work and individual work and its effects on employees, organisational conditions, and culture. Qualitative investigations that complement and contextualise quantitative findings is one means of obtaining a greater understanding and more viewpoints.

Implications of WPV policies

The results had major effects on WPV prevention and intervention policies in the PHC setting. The results highlighted the importance of enacting supportive organisational conditions, such as providing adequate staffing, adjusting working hours to acceptable shifts, or developing education and training programmes. As part of a holistic solution to violence, training programmes should focus on recognising early indicators of possible violence, assertiveness approaches, redirection strategies, and patient management protocols to mitigate negative effects on physical, psychological, and professional well-being. While previous WPV studies focused more on physical violence and inspired intervention efforts in many organisational settings, our results necessitate attention on non-physical forms of violence, which include verbal harassment, sexual misconduct, and intimidation. The increased potential of domestic- and crime-type violence in PHC settings necessitates expanded prevention programmes that address patients, visitors, healthcare providers, the surrounding community, and the general population.

Our results demonstrated that under-reporting of violent events remains a key issue, which is attributable to a lack of standardised WPV policies in many PHC settings. The initial action that should be implemented in accordance with human resource policy is to establish a system that renders it mandatory for victims, witnesses, and supervisors to report known instances of violence to HCWs. Unnecessary and redundant reporting processes can be reduced by an advanced system for rapidly recording WPV incidents, such as in hospital settings, where WPV is reported via a centralised electronic system. However, healthcare professional and organisational advocacy remains necessary. These parties must promote the value of routine procedures to ask employees about their encounters with patient violence and to foster an environment, where the organisation encourages reporting of violent incidents.

In addition to insufficient reporting, it is crucial to draw attention to the manner in which violent incident investigations are currently conducted in most workplaces. In reality, the incident reporting focuses on the violence itself and its superficial or circumstantial analysis, as opposed to an in-depth examination of the causes of violence, which are due to workplace psychosocial hazards, poor clinic environment, or poor customer service. For example, if any patient-inflicted violence occurred as a result of unsatisfactory conditions caused by poor clinic service, such as unnecessary delay, the tendency is to report on the perpetrator’s behaviour or on the violence itself rather than the unmet health service provision issue. In the long-term, however, the findings of such an investigation would not support the development of a violence prevention and management guideline, as it focuses on addressing aggressive patients rather than enhancing clinic service quality. Therefore, the relevant authorities should formulate a proper plan to improve the existing reporting and investigations mechanism to ensure that it is more comprehensive, structured, and detailed, either by providing proper training for the investigators or conducting institutional-level routine root cause analysis discussions, so that the violence hazard risk assessment can be framed effectively to resolve the antecedent factors in the future.