- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

What Are Business Ethics & Why Are They Important?

- 27 Jul 2023

From artificial intelligence to facial recognition technology, organizations face an increasing number of ethical dilemmas. While innovation can aid business growth, it can also create opportunities for potential abuse.

“The long-term impacts of a new technology—both positive and negative—may not become apparent until years after it’s introduced,” says Harvard Business School Professor Nien-hê Hsieh in the online course Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability . “For example, the impact of social media on children and teenagers didn’t become evident until we watched it play out over time.”

If you’re a current or prospective leader concerned about navigating difficult situations, here's an overview of business ethics, why they're important, and how to ensure ethical behavior in your organization.

Access your free e-book today.

What Are Business Ethics?

Business ethics are principles that guide decision-making . As a leader, you’ll face many challenges in the workplace because of different interpretations of what's ethical. Situations often require navigating the “gray area,” where it’s unclear what’s right and wrong.

When making decisions, your experiences, opinions, and perspectives can influence what you believe to be ethical, making it vital to:

- Be transparent.

- Invite feedback.

- Consider impacts on employees, stakeholders, and society.

- Reflect on past experiences to learn what you could have done better.

“The way to think about ethics, in my view, is: What are the externalities that your business creates, both positive and negative?” says Harvard Business School Professor Vikram Gandhi in Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability . “And, therefore, how do you actually increase the positive element of externalities? And how do you decrease the negative?”

Related: Why Managers Should Involve Their Team in the Decision-Making Process

Ethical Responsibilities to Society

Promoting ethical conduct can benefit both your company and society long term.

“I'm a strong believer that a long-term focus is what creates long-term value,” Gandhi says in Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability . “So you should get shareholders in your company that have that same perspective.”

Prioritizing the triple bottom line is an effective way for your business to fulfill its environmental responsibilities and create long-term value. It focuses on three factors:

- Profit: The financial return your company generates for shareholders

- People: How your company affects customers, employees, and stakeholders

- Planet: Your company’s impact on the planet and environment

Check out the video below to learn more about the triple bottom line, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

Ethical and corporate social responsibility (CSR) considerations can go a long way toward creating value, especially since an increasing number of customers, employees, and investors expect organizations to prioritize CSR. According to the Conscious Consumer Spending Index , 67 percent of customers prefer buying from socially responsible companies.

To prevent costly employee turnover and satisfy customers, strive to fulfill your ethical responsibilities to society.

Ethical Responsibilities to Customers

As a leader, you must ensure you don’t mislead your customers. Doing so can backfire, negatively impacting your organization’s credibility and profits.

Actions to avoid include:

- Greenwashing : Taking advantage of customers’ CSR preferences by claiming your business practices are sustainable when they aren't.

- False advertising : Making unverified or untrue claims in advertisements or promotional material.

- Making false promises : Lying to make a sale.

These unethical practices can result in multi-million dollar lawsuits, as well as highly dissatisfied customers.

Ethical Responsibilities to Employees

You also have ethical responsibilities to your employees—from the beginning to the end of their employment.

One area of business ethics that receives a lot of attention is employee termination. According to Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability , letting an employee go requires an individualized approach that ensures fairness.

Not only can wrongful termination cost your company upwards of $100,000 in legal expenses , it can also negatively impact other employees’ morale and how they perceive your leadership.

Ethical business practices have additional benefits, such as attracting and retaining talented employees willing to take a pay cut to work for a socially responsible company. Approximately 40 percent of millennials say they would switch jobs to work for a company that emphasizes sustainability.

Ultimately, it's critical to do your best to treat employees fairly.

“Fairness is not only an ethical response to power asymmetries in the work environment,” Hsieh says in the course. “Fairness—and having a successful organizational culture–can benefit the organization economically and legally.”

Why Are Business Ethics Important?

Failure to understand and apply business ethics can result in moral disengagement .

“Moral disengagement refers to ways in which we convince ourselves that what we’re doing is not wrong,” Hsieh says in Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability . “It can upset the balance of judgment—causing us to prioritize our personal commitments over shared beliefs, rules, and principles—or it can skew our logic to make unethical behaviors appear less harmful or not wrong.”

Moral disengagement can also lead to questionable decisions, such as insider trading .

“In the U.S., insider trading is defined in common, federal, and state laws regulating the opportunity for insiders to benefit from material, non-public information, or MNPI,” Hsieh explains.

This type of unethical behavior can carry severe legal consequences and negatively impact your company's bottom line.

“If you create a certain amount of harm to a society, your customers, or employees over a period of time, that’s going to have a negative impact on your economic value,” Gandhi says in the course.

This is reflected in over half of the top 10 largest bankruptcies between 1980 and 2013 that resulted from unethical behavior. As a business leader, strive to make ethical decisions and fulfill your responsibilities to stakeholders.

How to Implement Business Ethics

To become a more ethical leader, it's crucial to have a balanced, long-term focus.

“It's very important to balance the fact that, even if you're focused on the long term, you have to perform in the short term as well and have a very clear, articulated strategy around that,” Gandhi says in Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability .

Making ethical decisions requires reflective leadership.

“Reflecting on complex, gray-area decisions is a key part of what it means to be human, as well as an effective leader,” Hsieh says. “You have agency. You must choose how to act. And with that agency comes responsibility.”

Related: Why Are Ethics Important in Engineering?

Hsieh advises asking the following questions:

- Are you using the “greater good” to justify unethical behavior?

- Are you downplaying your actions to feel better?

“Asking these and similar questions at regular intervals can help you notice when you or others may be approaching the line between making a tough but ethical call and justifying problematic actions,” Hsieh says.

Become a More Ethical Leader

Learning from past successes and mistakes can enable you to improve your ethical decision-making.

“As a leader, when trying to determine what to do, it can be helpful to start by simply asking in any given situation, ‘What can we do?’ and ‘What would be wrong to do?’” Hsieh says.

Many times, the answers come from experience.

Gain insights from others’ ethical decisions, too. One way to do so is by taking an online course, such as Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability , which includes case studies that immerse you in real-world business situations, as well as a reflective leadership model to inform your decision-making.

Ready to become a better leader? Enroll in Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability —one of our online leadership and management courses —and download our free e-book on how to be a more effective leader.

About the Author

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.3: Ethics and Profitability

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 2603

lEARNING oBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Differentiate between short-term and long-term perspectives

- Differentiate between stockholder and stakeholder

- Discuss the relationship among ethical behavior, goodwill, and profit

- Explain the concept of corporate social responsibility

Few directives in business can override the core mission of maximizing shareholder wealth, and today that particularly means increasing quarterly profits. Such an intense focus on one variable over a short time (i.e., a short-term perspective ) leads to a short-sighted view of what constitutes business success.

Measuring true profitability, however, requires taking a long-term perspective. We cannot accurately measure success within a quarter of a year; a longer time is often required for a product or service to find its market and gain traction against competitors, or for the effects of a new business policy to be felt. Satisfying consumers’ demands, going green, being socially responsible, and acting above and beyond the basic requirements all take time and money. However, the extra cost and effort will result in profits in the long run. If we measure success from this longer perspective, we are more likely to understand the positive effect ethical behavior has on all who are associated with a business.

Profitability and Success: Thinking Long Term

Decades ago, some management theorists argued that a conscientious manager in a for-profit setting acts ethically by emphasizing solely the maximization of earnings. Today, most commentators contend that ethical business leadership is grounded in doing right by all stakeholders directly affected by a firm’s operations, including, but not limited to, stockholder s, or those who own shares of the company’s stock. That is, business leaders do right when they give thought to what is best for all who have a stake in their companies. Not only that, firms actually reap greater material success when they take such an approach, especially over the long run.

Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman stated in a now-famous New York Times Magazine article in 1970 that the only “social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits.” 2 This concept took hold in business and even in business school education. However, although it is certainly permissible and even desirable for a company to pursue profitability as a goal, managers must also have an understanding of the context within which their business operates and of how the wealth they create can add positive value to the world. The context within which they act is society, which permits and facilitates a firm’s existence.

Thus, a company enters a social contract with society as whole, an implicit agreement among all members to cooperate for social benefits. Even as a company pursues the maximizing of stockholder profit, it must also acknowledge that all of society will be affected to some extent by its operations. In return for society’s permission to incorporate and engage in business, a company owes a reciprocal obligation to do what is best for as many of society’s members as possible, regardless of whether they are stockholders. Therefore, when applied specifically to a business, the social contract implies that a company gives back to the society that permits it to exist, benefiting the community at the same time it enriches itself.

Link to learning

What happens when a bank decides to break the social contract? This press conference held by the National Whistleblowers Center describes the events surrounding the $104 million whistleblower reward given to former UBS employee Bradley Birkenfeld by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. While employed at UBS, Switzerland’s largest bank, Birkenfeld assisted in the company’s illegal offshore tax business, and he later served forty months in prison for conspiracy. But he was also the original source of incriminating information that led to a Federal Bureau of Investigation examination of the bank and to the U.S. government’s decision to impose a $780 million fine on UBS in 2009. In addition, Birkenfeld turned over to investigators the account information of more than 4,500 U.S. private clients of UBS. 3

In addition to taking this more nuanced view of profits, managers must also use a different time frame for obtaining them. Wall Street’s focus on periodic (i.e., quarterly and annual) earnings has led many managers to adopt a short-term perspective, which fails to take into account effects that require a longer time to develop. For example, charitable donations in the form of corporate assets or employees’ volunteered time may not show a return on investment until a sustained effort has been maintained for years. A long-term perspective is a more balanced view of profit maximization that recognizes that the impacts of a business decision may not manifest for a longer time.

As an example, consider the business practices of Toyota when it first introduced its vehicles for sale in the United States in 1957. For many years, Toyota was content to sell its cars at a slight loss because it was accomplishing two business purposes: It was establishing a long-term relationship of trust with those who eventually would become its loyal U.S. customers, and it was attempting to disabuse U.S. consumers of their belief that items made in Japan were cheap and unreliable. The company accomplished both goals by patiently playing its long game, a key aspect of its operational philosophy, “The Toyota Way,” which includes a specific emphasis on long-term business goals, even at the expense of short-term profit. 4

What contributes to a corporation’s positive image over the long term? Many factors contribute, including a reputation for treating customers and employees fairly and for engaging in business honestly. Companies that act in this way may emerge from any industry or country. Examples include Fluor, the large U.S. engineering and design firm; illycaffè, the Italian food and beverage purveyor; Marriott, the giant U.S. hotelier; and Nokia, the Finnish telecommunications retailer. The upshot is that when consumers are looking for an industry leader to patronize and would-be employees are seeking a firm to join, companies committed to ethical business practices are often the first to come to mind.

Why should stakeholders care about a company acting above and beyond the ethical and legal standards set by society? Simply put, being ethical is simply good business. A business is profitable for many reasons, including expert management teams, focused and happy employees, and worthwhile products and services that meet consumer demand. One more and very important reason is that they maintain a company philosophy and mission to do good for others.

Year after year, the nation’s most admired companies are also among those that had the highest profit margins. Going green, funding charities, and taking a personal interest in employee happiness levels adds to the bottom line! Consumers want to use companies that care for others and our environment. During the years 2008 and 2009, many unethical companies went bankrupt. However, those companies that avoided the “quick buck,” risky and unethical investments, and other unethical business practices often flourished. If nothing else, consumer feedback on social media sites such as Yelp and Facebook can damage an unethical company’s prospects.

CASES FROM THE REAL WORLD

Competition and the markers of business success.

Perhaps you are still thinking about how you would define success in your career. For our purposes here, let us say that success consists simply of achieving our goals. We each have the ability to choose the goals we hope to accomplish in business, of course, and, if we have chosen them with integrity, our goals and the actions we take to achieve them will be in keeping with our character.

Warren Buffet ( Figure 1.4 ), whom many consider the most successful investor of all time, is an exemplar of business excellence as well as a good potential role model for professionals of integrity and the art of thinking long term. He had the following to say: “Ultimately, there’s one investment that supersedes all others: Invest in yourself. Nobody can take away what you’ve got in yourself, and everybody has potential they haven’t used yet. . . . You’ll have a much more rewarding life not only in terms of how much money you make, but how much fun you have out of life; you’ll make more friends the more interesting person you are, so go to it, invest in yourself.” 5

The primary principle under which Buffett instructs managers to operate is: “Do nothing you would not be happy to have an unfriendly but intelligent reporter write about on the front page of a newspaper.” 6 This is a very simple and practical guide to encouraging ethical business behavior on a personal level. Buffett offers another, equally wise, principle: “Lose money for the firm, even a lot of money, and I will be understanding; lose reputation for the firm, even a shred of reputation, and I will be ruthless.” 7 As we saw in the example of Toyota, the importance of establishing and maintaining trust in the long term cannot be underestimated.

For more on Warren Buffett’s thoughts about being both an economic and ethical leader, watch this interview that appeared on the PBS NewsHour on June 6, 2017.

Stockholders, Stakeholders, and Goodwill

Earlier in this chapter, we explained that stakeholders are all the individuals and groups affected by a business’s decisions. Among these stakeholders are stockholders (or shareholder s), individuals and institutions that own stock (or shares) in a corporation. Understanding the impact of a business decision on the stockholder and various other stakeholders is critical to the ethical conduct of business. Indeed, prioritizing the claims of various stakeholders in the company is one of the most challenging tasks business professionals face. Considering only stockholders can often result in unethical decisions; the impact on all stakeholders must be considered and rationally assessed.

Managers do sometimes focus predominantly on stockholders, especially those holding the largest number of shares, because these powerful individuals and groups can influence whether managers keep their jobs or are dismissed (e.g., when they are held accountable for the company’s missing projected profit goals). And many believe the sole purpose of a business is, in fact, to maximize stockholders’ short-term profits. However, considering only stockholders and short-term impacts on them is one of the most common errors business managers make. It is often in the long-term interests of a business not to accommodate stockowners alone but rather to take into account a broad array of stakeholders and the long-term and short-term consequences for a course of action.

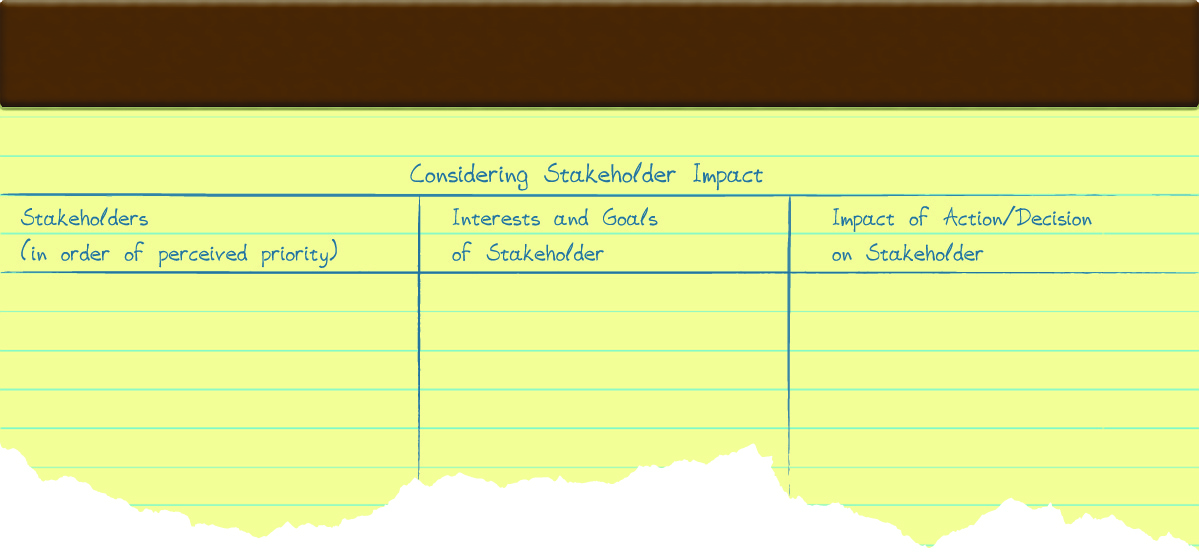

Here is a simple strategy for considering all your stakeholders in practice. Divide your screen or page into three columns; in the first column, list all stakeholders in order of perceived priority ( Figure 1.5 ). Some individuals and groups play more than one role. For instance, some employees may be stockholders, some members of the community may be suppliers, and the government may be a customer of the firm. In the second column, list what you think each stakeholder group’s interests and goals are. For those that play more than one role, choose the interests most directly affected by your actions. In the third column, put the likely impact of your business decision on each stakeholder. This basic spreadsheet should help you identify all your stakeholders and evaluate your decision’s impact on their interests. If you would like to add a human dimension to your analysis, try assigning some of your colleagues to the role of stakeholders and reexamine your analysis.

The positive feeling stakeholders have for any particular company is called goodwill , which is an important component of almost any business entity, even though it is not directly attributable to the company’s assets and liabilities. Among other intangible assets, goodwill might include the worth of a business’s reputation, the value of its brand name, the intellectual capital and attitude of its workforce, and the loyalty of its established customer base. Even being socially responsible generates goodwill. The ethical behavior of managers will have a positive influence on the value of each of those components. Goodwill cannot be earned or created in a short time, but it can be the key to success and profitability.

A company’s name, its corporate logo, and its trademark will necessarily increase in value as stakeholders view that company in a more favorable light. A good reputation is essential for success in the modern business world, and with information about the company and its actions readily available via mass media and the Internet (e.g., on public rating sites such as Yelp), management’s values are always subject to scrutiny and open debate. These values affect the environment outside and inside the company. The corporate culture , for instance, consists of shared beliefs, values, and behaviors that create the internal or organizational context within which managers and employees interact. Practicing ethical behavior at all levels—from CEO to upper and middle management to general employees—helps cultivate an ethical corporate culture and ethical employee relations.

Learning Objectives

Which Corporate Culture Do You Value?

Imagine that upon graduation you have the good fortune to be offered two job opportunities. The first is with a corporation known to cultivate a hard-nosed, no-nonsense business culture in which keeping long hours and working intensely are highly valued. At the end of each year, the company donates to numerous social and environmental causes. The second job opportunity is with a nonprofit recognized for a very different culture based on its compassionate approach to employee work-life balance. It also offers the chance to pursue your own professional interests or volunteerism during a portion of every work day. The first job offer pays 20 percent more per year.

Critical Thinking

- Which of these opportunities would you pursue and why?

- How important an attribute is salary, and at what point would a higher salary override for you the nonmonetary benefits of the lower-paid position?

Positive goodwill generated by ethical business practices, in turn, generates long-term business success. As recent studies have shown, the most ethical and enlightened companies in the United States consistently outperform their competitors. 8 Thus, viewed from the proper long-term perspective, conducting business ethically is a wise business decision that generates goodwill for the company among stakeholders, contributes to a positive corporate culture, and ultimately supports profitability.

You can test the validity of this claim yourself. When you choose a company with which to do business, what factors influence your choice? Let us say you are looking for a financial advisor for your investments and retirement planning, and you have found several candidates whose credentials, experience, and fees are approximately the same. Yet one of these firms stands above the others because it has a reputation, which you discover is well earned, for telling clients the truth and recommending investments that seemed centered on the clients’ benefit and not on potential profit for the firm. Wouldn’t this be the one you would trust with your investments?

Or suppose one group of financial advisors has a long track record of giving back to the community of which it is part. It donates to charitable organizations in local neighborhoods, and its members volunteer service hours toward worthy projects in town. Would this group not strike you as the one worthy of your investments? That it appears to be committed to building up the local community might be enough to persuade you to give it your business. This is exactly how a long-term investment in community goodwill can produce a long pipeline of potential clients and customers.

The Equifax Data Breach

In 2017, from mid-May to July, hackers gained unauthorized access to servers used by Equifax, a major credit reporting agency, and accessed the personal information of nearly one-half the U.S. population. 9 Equifax executives sold off nearly $2 million of company stock they owned after finding out about the hack in late July, weeks before it was publicly announced on September 7, 2017, in potential violation of insider trading rules. The company’s shares fell nearly 14 percent after the announcement, but few expect Equifax managers to be held liable for their mistakes, face any regulatory discipline, or pay any penalties for profiting from their actions. To make amends to customers and clients in the aftermath of the hack, the company offered free credit monitoring and identity-theft protection. On September 15, 2017, the company’s chief information officer and chief of security retired. On September 26, 2017, the CEO resigned, days before he was to testify before Congress about the breach. To date, numerous government investigations and hundreds of private lawsuits have been filed as a result of the hack.

- Which elements of this case might involve issues of legal compliance? Which elements illustrate acting legally but not ethically? What would acting ethically and with personal integrity in this situation look like?

- How do you think this breach will affect Equifax’s position relative to those of its competitors? How might it affect the future success of the company?

- Was it sufficient for Equifax to offer online privacy protection to those whose personal information was hacked? What else might it have done?

A Brief Introduction to Corporate Social Responsibility

If you truly appreciate the positions of your various stakeholders, you will be well on your way to understanding the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) . CSR is the practice by which a business views itself within a broader context, as a member of society with certain implicit social obligations and environmental responsibilities. As previously stated, there is a distinct difference between legal compliance and ethical responsibility, and the law does not fully address all ethical dilemmas that businesses face. CSR ensures that a company is engaging in sound ethical practices and policies in accordance with the company’s culture and mission, above and beyond any mandatory legal standards. A business that practices CSR cannot have maximizing shareholder wealth as its sole purpose, because this goal would necessarily infringe on the rights of other stakeholders in the broader society. For instance, a mining company that disregards its corporate social responsibility may infringe on the right of its local community to clean air and water if it pursues only profit. In contrast, CSR places all stakeholders within a proper contextual framework.

An additional perspective to take concerning CSR is that ethical business leaders opt to do good at the same time that they do well. This is a simplistic summation, but it speaks to how CSR plays out within any corporate setting. The idea is that a corporation is entitled to make money, but it should not only make money. It should also be a good civic neighbor and commit itself to the general prospering of society as a whole. It ought to make the communities of which it is part better at the same time it pursues legitimate profit goals. These ends are not mutually exclusive, and it is possible—indeed, praiseworthy—to strive for both. When a company approaches business in this fashion, it is engaging in a commitment to corporate social responsibility.

Link to Learning

U.S. entrepreneur Blake Mycoskie has created a unique business model combining both for-profit and nonprofit philosophies in an innovative demonstration of corporate social responsibility. The company he founded, TOMS Shoes, donates one pair of shoes to a child in need for every pair sold. As of May 2018, the company has provided more than 75 million pairs of shoes to children in seventy countries. 10

1.2 Ethics and Profitability

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Differentiate between short-term and long-term perspectives

- Differentiate between stockholder and stakeholder

- Discuss the relationship among ethical behavior, goodwill, and profit

- Explain the concept of corporate social responsibility

Few directives in business can override the core mission of maximizing shareholder wealth, and today that particularly means increasing quarterly profits. Such an intense focus on one variable over a short time (i.e., a short-term perspective ) leads to a short-sighted view of what constitutes business success.

Measuring true profitability, however, requires taking a long-term perspective. We cannot accurately measure success within a quarter of a year; a longer time is often required for a product or service to find its market and gain traction against competitors, or for the effects of a new business policy to be felt. Satisfying consumers’ demands, going green, being socially responsible, and acting above and beyond the basic requirements all take time and money. However, the extra cost and effort will result in profits in the long run. If we measure success from this longer perspective, we are more likely to understand the positive effect ethical behavior has on all who are associated with a business.

Profitability and Success: Thinking Long Term

Decades ago, some management theorists argued that a conscientious manager in a for-profit setting acts ethically by emphasizing solely the maximization of earnings. Today, most commentators contend that ethical business leadership is grounded in doing right by all stakeholders directly affected by a firm’s operations, including, but not limited to, stockholder s , or those who own shares of the company’s stock. That is, business leaders do right when they give thought to what is best for all who have a stake in their companies. Not only that, firms actually reap greater material success when they take such an approach, especially over the long run.

Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman stated in a now-famous New York Times Magazine article in 1970 that the only “social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits.” 2 This concept took hold in business and even in business school education. However, although it is certainly permissible and even desirable for a company to pursue profitability as a goal, managers must also have an understanding of the context within which their business operates and of how the wealth they create can add positive value to the world. The context within which they act is society, which permits and facilitates a firm’s existence.

Thus, a company enters a social contract with society as whole, an implicit agreement among all members to cooperate for social benefits. Even as a company pursues the maximizing of stockholder profit, it must also acknowledge that all of society will be affected to some extent by its operations. In return for society’s permission to incorporate and engage in business, a company owes a reciprocal obligation to do what is best for as many of society’s members as possible, regardless of whether they are stockholders. Therefore, when applied specifically to a business, the social contract implies that a company gives back to the society that permits it to exist, benefiting the community at the same time it enriches itself.

Link to Learning

What happens when a bank decides to break the social contract? This press conference held by the National Whistleblowers Center describes the events surrounding the $104 million whistleblower reward given to former UBS employee Bradley Birkenfeld by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. While employed at UBS, Switzerland’s largest bank, Birkenfeld assisted in the company’s illegal offshore tax business, and he later served forty months in prison for conspiracy. But he was also the original source of incriminating information that led to a Federal Bureau of Investigation examination of the bank and to the U.S. government’s decision to impose a $780 million fine on UBS in 2009. In addition, Birkenfeld turned over to investigators the account information of more than 4,500 U.S. private clients of UBS. 3

In addition to taking this more nuanced view of profits, managers must also use a different time frame for obtaining them. Wall Street’s focus on periodic (i.e., quarterly and annual) earnings has led many managers to adopt a short-term perspective, which fails to take into account effects that require a longer time to develop. For example, charitable donations in the form of corporate assets or employees’ volunteered time may not show a return on investment until a sustained effort has been maintained for years. A long-term perspective is a more balanced view of profit maximization that recognizes that the impacts of a business decision may not manifest for a longer time.

As an example, consider the business practices of Toyota when it first introduced its vehicles for sale in the United States in 1957. For many years, Toyota was content to sell its cars at a slight loss because it was accomplishing two business purposes: It was establishing a long-term relationship of trust with those who eventually would become its loyal U.S. customers, and it was attempting to disabuse U.S. consumers of their belief that items made in Japan were cheap and unreliable. The company accomplished both goals by patiently playing its long game, a key aspect of its operational philosophy, “The Toyota Way,” which includes a specific emphasis on long-term business goals, even at the expense of short-term profit. 4

What contributes to a corporation’s positive image over the long term? Many factors contribute, including a reputation for treating customers and employees fairly and for engaging in business honestly. Companies that act in this way may emerge from any industry or country. Examples include Fluor, the large U.S. engineering and design firm; illycaffè, the Italian food and beverage purveyor; Marriott, the giant U.S. hotelier; and Nokia, the Finnish telecommunications retailer. The upshot is that when consumers are looking for an industry leader to patronize and would-be employees are seeking a firm to join, companies committed to ethical business practices are often the first to come to mind.

Why should stakeholders care about a company acting above and beyond the ethical and legal standards set by society? Simply put, being ethical is simply good business. A business is profitable for many reasons, including expert management teams, focused and happy employees, and worthwhile products and services that meet consumer demand. One more and very important reason is that they maintain a company philosophy and mission to do good for others.

Year after year, the nation’s most admired companies are also among those that had the highest profit margins. Going green, funding charities, and taking a personal interest in employee happiness levels adds to the bottom line! Consumers want to use companies that care for others and our environment. During the years 2008 and 2009, many unethical companies went bankrupt. However, those companies that avoided the “quick buck,” risky and unethical investments, and other unethical business practices often flourished. If nothing else, consumer feedback on social media sites such as Yelp and Facebook can damage an unethical company’s prospects.

Cases from the Real World

Competition and the markers of business success.

Perhaps you are still thinking about how you would define success in your career. For our purposes here, let us say that success consists simply of achieving our goals. We each have the ability to choose the goals we hope to accomplish in business, of course, and, if we have chosen them with integrity, our goals and the actions we take to achieve them will be in keeping with our character.

Warren Buffet ( Figure 1.4 ), whom many consider the most successful investor of all time, is an exemplar of business excellence as well as a good potential role model for professionals of integrity and the art of thinking long term. He had the following to say: “Ultimately, there’s one investment that supersedes all others: Invest in yourself. Nobody can take away what you’ve got in yourself, and everybody has potential they haven’t used yet. . . . You’ll have a much more rewarding life not only in terms of how much money you make, but how much fun you have out of life; you’ll make more friends the more interesting person you are, so go to it, invest in yourself.” 5

The primary principle under which Buffett instructs managers to operate is: “Do nothing you would not be happy to have an unfriendly but intelligent reporter write about on the front page of a newspaper.” 6 This is a very simple and practical guide to encouraging ethical business behavior on a personal level. Buffett offers another, equally wise, principle: “Lose money for the firm, even a lot of money, and I will be understanding; lose reputation for the firm, even a shred of reputation, and I will be ruthless.” 7 As we saw in the example of Toyota, the importance of establishing and maintaining trust in the long term cannot be underestimated.

For more on Warren Buffett’s thoughts about being both an economic and ethical leader, watch this interview that appeared on the PBS NewsHour on June 6, 2017.

Stockholders, Stakeholders, and Goodwill

Earlier in this chapter, we explained that stakeholders are all the individuals and groups affected by a business’s decisions. Among these stakeholders are stockholders (or shareholder s ), individuals and institutions that own stock (or shares) in a corporation. Understanding the impact of a business decision on the stockholder and various other stakeholders is critical to the ethical conduct of business. Indeed, prioritizing the claims of various stakeholders in the company is one of the most challenging tasks business professionals face. Considering only stockholders can often result in unethical decisions; the impact on all stakeholders must be considered and rationally assessed.

Managers do sometimes focus predominantly on stockholders, especially those holding the largest number of shares, because these powerful individuals and groups can influence whether managers keep their jobs or are dismissed (e.g., when they are held accountable for the company’s missing projected profit goals). And many believe the sole purpose of a business is, in fact, to maximize stockholders’ short-term profits. However, considering only stockholders and short-term impacts on them is one of the most common errors business managers make. It is often in the long-term interests of a business not to accommodate stockowners alone but rather to take into account a broad array of stakeholders and the long-term and short-term consequences for a course of action.

Here is a simple strategy for considering all your stakeholders in practice. Divide your screen or page into three columns; in the first column, list all stakeholders in order of perceived priority ( Figure 1.5 ). Some individuals and groups play more than one role. For instance, some employees may be stockholders, some members of the community may be suppliers, and the government may be a customer of the firm. In the second column, list what you think each stakeholder group’s interests and goals are. For those that play more than one role, choose the interests most directly affected by your actions. In the third column, put the likely impact of your business decision on each stakeholder. This basic spreadsheet should help you identify all your stakeholders and evaluate your decision’s impact on their interests. If you would like to add a human dimension to your analysis, try assigning some of your colleagues to the role of stakeholders and reexamine your analysis.

The positive feeling stakeholders have for any particular company is called goodwill , which is an important component of almost any business entity, even though it is not directly attributable to the company’s assets and liabilities. Among other intangible assets, goodwill might include the worth of a business’s reputation, the value of its brand name, the intellectual capital and attitude of its workforce, and the loyalty of its established customer base. Even being socially responsible generates goodwill. The ethical behavior of managers will have a positive influence on the value of each of those components. Goodwill cannot be earned or created in a short time, but it can be the key to success and profitability.

A company’s name, its corporate logo, and its trademark will necessarily increase in value as stakeholders view that company in a more favorable light. A good reputation is essential for success in the modern business world, and with information about the company and its actions readily available via mass media and the Internet (e.g., on public rating sites such as Yelp), management’s values are always subject to scrutiny and open debate. These values affect the environment outside and inside the company. The corporate culture , for instance, consists of shared beliefs, values, and behaviors that create the internal or organizational context within which managers and employees interact. Practicing ethical behavior at all levels—from CEO to upper and middle management to general employees—helps cultivate an ethical corporate culture and ethical employee relations.

What Would You Do?

Which corporate culture do you value.

Imagine that upon graduation you have the good fortune to be offered two job opportunities. The first is with a corporation known to cultivate a hard-nosed, no-nonsense business culture in which keeping long hours and working intensely are highly valued. At the end of each year, the company donates to numerous social and environmental causes. The second job opportunity is with a nonprofit recognized for a very different culture based on its compassionate approach to employee work-life balance. It also offers the chance to pursue your own professional interests or volunteerism during a portion of every work day. The first job offer pays 20 percent more per year.

Critical Thinking

- Which of these opportunities would you pursue and why?

- How important an attribute is salary, and at what point would a higher salary override for you the nonmonetary benefits of the lower-paid position?

Positive goodwill generated by ethical business practices, in turn, generates long-term business success. As recent studies have shown, the most ethical and enlightened companies in the United States consistently outperform their competitors. 8 Thus, viewed from the proper long-term perspective, conducting business ethically is a wise business decision that generates goodwill for the company among stakeholders, contributes to a positive corporate culture, and ultimately supports profitability.

You can test the validity of this claim yourself. When you choose a company with which to do business, what factors influence your choice? Let us say you are looking for a financial advisor for your investments and retirement planning, and you have found several candidates whose credentials, experience, and fees are approximately the same. Yet one of these firms stands above the others because it has a reputation, which you discover is well earned, for telling clients the truth and recommending investments that seemed centered on the clients’ benefit and not on potential profit for the firm. Wouldn’t this be the one you would trust with your investments?

Or suppose one group of financial advisors has a long track record of giving back to the community of which it is part. It donates to charitable organizations in local neighborhoods, and its members volunteer service hours toward worthy projects in town. Would this group not strike you as the one worthy of your investments? That it appears to be committed to building up the local community might be enough to persuade you to give it your business. This is exactly how a long-term investment in community goodwill can produce a long pipeline of potential clients and customers.

The Equifax Data Breach

In 2017, from mid-May to July, hackers gained unauthorized access to servers used by Equifax, a major credit reporting agency, and accessed the personal information of nearly one-half the U.S. population. 9 Equifax executives sold off nearly $2 million of company stock they owned after finding out about the hack in late July, weeks before it was publicly announced on September 7, 2017, in potential violation of insider trading rules. The company’s shares fell nearly 14 percent after the announcement, but few expect Equifax managers to be held liable for their mistakes, face any regulatory discipline, or pay any penalties for profiting from their actions. To make amends to customers and clients in the aftermath of the hack, the company offered free credit monitoring and identity-theft protection. On September 15, 2017, the company’s chief information officer and chief of security retired. On September 26, 2017, the CEO resigned, days before he was to testify before Congress about the breach. To date, numerous government investigations and hundreds of private lawsuits have been filed as a result of the hack.

- Which elements of this case might involve issues of legal compliance? Which elements illustrate acting legally but not ethically? What would acting ethically and with personal integrity in this situation look like?

- How do you think this breach will affect Equifax’s position relative to those of its competitors? How might it affect the future success of the company?

- Was it sufficient for Equifax to offer online privacy protection to those whose personal information was hacked? What else might it have done?

A Brief Introduction to Corporate Social Responsibility

If you truly appreciate the positions of your various stakeholders, you will be well on your way to understanding the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) . CSR is the practice by which a business views itself within a broader context, as a member of society with certain implicit social obligations and environmental responsibilities. As previously stated, there is a distinct difference between legal compliance and ethical responsibility, and the law does not fully address all ethical dilemmas that businesses face. CSR ensures that a company is engaging in sound ethical practices and policies in accordance with the company’s culture and mission, above and beyond any mandatory legal standards. A business that practices CSR cannot have maximizing shareholder wealth as its sole purpose, because this goal would necessarily infringe on the rights of other stakeholders in the broader society. For instance, a mining company that disregards its corporate social responsibility may infringe on the right of its local community to clean air and water if it pursues only profit. In contrast, CSR places all stakeholders within a proper contextual framework.

An additional perspective to take concerning CSR is that ethical business leaders opt to do good at the same time that they do well. This is a simplistic summation, but it speaks to how CSR plays out within any corporate setting. The idea is that a corporation is entitled to make money, but it should not only make money. It should also be a good civic neighbor and commit itself to the general prospering of society as a whole. It ought to make the communities of which it is part better at the same time it pursues legitimate profit goals. These ends are not mutually exclusive, and it is possible—indeed, praiseworthy—to strive for both. When a company approaches business in this fashion, it is engaging in a commitment to corporate social responsibility.

U.S. entrepreneur Blake Mycoskie has created a unique business model combining both for-profit and nonprofit philosophies in an innovative demonstration of corporate social responsibility. The company he founded, TOMS Shoes, donates one pair of shoes to a child in need for every pair sold. As of May 2018, the company has provided more than 75 million pairs of shoes to children in seventy countries. 10

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Stephen M. Byars, Kurt Stanberry

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Business Ethics

- Publication date: Sep 24, 2018

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-2-ethics-and-profitability

© Mar 31, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Business Ethics Journal Review

Edited by alexei marcoux & chris macdonald — issn 2326-7526.

- About BEJR — Now 10 years in!

- Books Received

- Instructions for Authors

- Past Issues

- The Editors

Student’s Guide to Writing Critical Essays in Business Ethics (and beyond)

Here is some advice for writing critical essays, in business ethics but also in other fields. There is of course much more to say on the topic, but this is a start.

Writing your own critical essay:

What kinds of criticisms should you offer in your essay? There are a nearly infinite number of errors or problems that you might spot in an essay or book that you want to critique. Here are a few common ones to look for, to get you started:

- Point out one or more logical fallacies. Did the author present a false dilemma , for example? Or an argument from ignorance ? Has the author presented a false analogy or a hasty generalization ?

- Critique the scope of the author’s claim. For example, does the author claim that his or her conclusion applies to all cases, rather than just to the small number of cases he or she has actually argued for?

- Point out unjustified assumptions. Has the author made questionable assumptions about some matter of fact, without providing evidence? Alternatively, has the author assumed that readers share some questionable ethical starting point, perhaps a belief in a particular debatable principle?

- Point out internal contradictions. Does the author say two things that, perhaps subtly, contradict each other?

- Point out undesirable implications / consequences. Does the author’s position imply, perhaps accidentally, some further conclusion that the author (or audience) is unlikely to want to accept, upon reflection?

In general, a good critical essay should:

- Describe and explain in neutral terms the article or book being critiqued. Before you start offering criticism, you should demonstrate that you understand the point of view you are critiquing.

- Be modest. Your goal should be to offer some insight, rather than to win a debate. Rather than to “show that Smith is wrong” or “prove that Sen’s view is incorrect,” you should set your aims on some more reasonable goal, such as “casting doubt” on the view you are critiquing, or “suggesting reason why so-and-so should modify her view.”

- Be fair. Sometimes this is referred to as the “principle of charity.” It has nothing to do with donating money. Rather, it is about giving the other side what you owe them, namely a fair reading. Your goal is not to make the author whose work you are criticizing sound dumb. Rather, the goal is to make her sound smart, but then to make yourself sound smart, too, but showing how her view could be improved.

- Be well structured . Professors love structure. Remember: a critical essay is not just a bunch of ideas; it is an orderly attempt to convince someone (in most cases, your professor) of a particular point of view. Your ideas will only have real punch if you put them in a suitable structure. That’s not all that hard. For example, make sure your opening paragraph acts as a roadmap for what follows — telling the reader where you’re going and how you propose to get there. Make sure each paragraph in the body of your essay has a main point (a point connected to the goal of your essay!) and that its point is clearly explained.

- Stick to two or maybe three main arguments . “The three main problems with Jones’s argument are x, y, and z.”

- Be clear. That means not just that your essay should be clearly structured, but also that each sentence should be clear. Proof-reading is important: get someone with good writing skills to proof-read your essay for you. If you can’t do that before your deadline, you can proof-read your essay yourself by reading it out loud. We’re serious. It is much easier to spot errors in your own writing if you read out loud.

A few more tips:

- Cite your sources carefully. Use whichever citation method your professor says to use. If in doubt, use one of the established methods (such as APA or Chicago ). But whatever you do, make sure to give credit to the people whose ideas you use, if you want to avoid being charged with plagiarism.

- Use what you’ve learned in class. Your professor would love nothing more than to know that you’ve been paying attention. So try to make use of some of the concepts discussed in class, or in your course textbook.

- Don’t try to sound like an author. Just say what you want to say. Trying to sound like an author just leads people to use big words they don’t understand and to write complex sentences that overshoot their grammatical skills. Just write it more or less the way you would say it out loud, in short, clear sentences.

- Follow instructions. Failing to follow instructions is easily the most common way students screw up when writing critical essays. Read the assignment instructions through carefully — twice! — and then if anything is unclear, ask your professor for clarification.

Looking for essay topics? Check out Business Ethics Highlights .

See also: The Concise Encyclopedia of Business Ethics

Share this:

3 comments on “student’s guide to writing critical essays in business ethics (and beyond)”.

This is a useful resource – thanks Chris

“Shack”

Arthur Shacklock (Griffith University Queensland, Australia)

I’m currently a student at Arizona Christian University taking a Business Ethics course. I’m in the midst of completing an assignment that requires me to post on an open blog forum. It was very difficult for me to find something interesting and that pertained to my class. Then I stumbled across your blog then more specifically, this article. The purpose of this specific assignment is to share my individual and collective experiences derived from collaborative learning and expressed through the narrative, as “actionable knowledge.” Actionable knowledge reflects the learning capability of individuals and organizations to connect elements including; social, political, economic, technological.

Knowing how to write critical essays in Business Ethics is an important element of success. I enjoyed reading through these helpful tips. This is useful information that will help in college and beyond.

Supporting evidence is an important part of writing a sound paper. Like you mentioned in the blog, it can’t be based on bias or ignorance. Rather, backed up by factual evidence to help support your claim. I love the general key points as well. Describe and explain, be modest, be fair, be well structured, and be clear. I am very familiar with these key elements as we have spoken on them in class. They are very important components of business ethics. We’ve learned things about leading in the business world, Capitalism, Socialism, and Communism, Business advertising, and more. In the essay I write in this course, I will refer back to this blog.

Like any other course, it is important to cite your sources like you’ve mentioned above as well as use information that we’ve learned in class. Sound like yourself and speak from your own understanding. The last tip was to follow instructions WHICH IS THE KEY TO SUCCESS! It’s all in the fine print. Read until you understand and ask questions if you don’t.

Good luck with your studies, Deon!

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Recent posts.

- v11n2: von Kriegstein Responds to Ancell

- v11n1: Hargrave and Smith on Stakeholder Governance

- v10n5: Ancell on von Kriegstein on the ‘Radical Behavioral Challenge’

- v10n4: Scharding Responds to Allison

- v10n3: Young on Singer on Disruptive Innovation

Peer-Reviewed Business Ethics Journals (not an exhaustive list!)

Editors’ favourite blogs, useful links, we’re social.

BEJR is published by

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Business Ethics

Exchange is fundamental to business. ‘Business’ can mean an activity of exchange. One entity (e.g., a person, a firm) “does business” with another when it exchanges a good or service for valuable consideration, i.e., a benefit such as money. ‘Business’ can also mean an entity that offers goods and services for exchange, i.e., that sells things. Target is a business. Business ethics can thus be understood as the study of the ethical dimensions of the exchange of goods and services, and of the entities that offer goods and services for exchange. This includes related activities such as the production, distribution, marketing, sale, and consumption of goods and services (cf. Donaldson & Walsh 2015; Marcoux 2006b).

Questions in business ethics are important and relevant to everyone. Almost all of us “do business”, or engage in a commercial transaction, almost every day. Many of us spend a major portion of our lives engaged in, or preparing to engage in, exchange activities, on our own or as part of organizations. Business activity shapes the world we live in, sometimes for good and sometimes for ill.

Business ethics in its current incarnation is a relatively new field, growing out of research by moral philosophers in the 1970’s and 1980’s. But scholars have been thinking about the ethical dimensions of commerce at least since the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1750 BC).

This entry summarizes research on central questions in business ethics, including: What sorts of things can be sold? How can they be sold? In whose interests should firms be managed? Who should manage them? What do firms owe their workers, and what do workers owe their firms? Should firms try to solve social problems? Is it permissible for them to try to influence political outcomes? Given the vastness of the field, of necessity certain questions are not addressed.

1. Varieties of business ethics

2. corporate moral agency, 3.1 ends: shareholder primacy or stakeholder balance, 3.2 means: control by shareholders or others too, 4. important frameworks for business ethics, 5.1 the limits of markets, 5.2 product safety and liability, 5.3 advertising, 5.5 pricing, 6.1 hiring and firing, 6.2 compensation, 6.3 meaningful work, 6.4 whistleblowing, 7.1 corporate social responsibility, 7.2 corporate political activity, 7.3 international business, 8. the status of business ethics, other internet resources, related entries.

Many people engaged in business activity, including accountants and lawyers, are professionals. As such, they are bound by codes of conduct promulgated by professional societies. Many firms also have detailed codes of conduct, developed and enforced by teams of ethics and compliance personnel. Business ethics can thus be understood as the study of professional practices, i.e., as the study of the content, development, enforcement, and effectiveness of the codes of conduct designed to guide the actions of people engaged in business activity. This entry will not consider this form of business ethics. Instead, it considers business ethics as an academic discipline.

The academic field of business ethics is shared by social scientists and normative theorists. But they address different questions. Social scientists try to answer descriptive questions like: Does corporate social performance improve corporate financial performance, i.e., does ethics pay (Vogel 2005; Zhao & Murrell 2021)? Why do people engage in unethical behavior (Bazerman & Tenbrunsel 2011; Werhane et al. 2013). How can we make them stop (Warren, Gaspar, & Laufer 2014)? I will not consider such questions here. This entry focuses on questions in normative business ethics, most of which are variants on the question: What is ethical and unethical in business?

Normative business ethicists (hereafter the qualifier ‘normative’ will be assumed) tend to accept the basic elements of capitalism. That is, they assume that the means of production can be privately owned and that markets—featuring voluntary exchanges between buyers and sellers at mutually agreeable prices—should play an important role in the allocation of resources. Those who reject capitalism will see some debates in business ethics (e.g., about firm ownership and control) as misguided.

Some entities “do business” with the goal of making a profit, and some do not. Pfizer and Target are examples of the former; Rutgers University and the Metropolitan Museum of Art are examples of the latter. An organization identified as a ‘business’ is typically understood to be one that seeks profit, and for-profit organizations are the ones that business ethicists focus on. But many of the ethical issues described below arise also for non-profit organizations and individual economic agents.

One way to think about business ethics is in terms of the moral obligations of agents engaged in business activity. Who can be a moral agent? Individual persons, obviously. What about firms? This is treated as the issue of “corporate moral agency” or “corporate moral responsibility”. Here ‘corporate’ does not refer to the corporation as a legal entity, but to a collective or group of individuals. To be precise, the question is whether firms are moral agents and morally responsible considered as ( qua ) firms, not considered as aggregates of individual members of firms.

We often think and speak as if corporations are morally responsible. We say things like “Costco treats its employees well” or “BP harmed the environment in the Gulf of Mexico”, and in doing so we appear to assign agency and responsibility to firms themselves (Dempsey 2003). We may wish to praise Costco and blame BP for their behavior. But this may be just a metaphorical way of speaking, or a shorthand way of referring to certain individuals who work in these firms (Velasquez 1983, 2003). Corporations are different in many ways from paradigm moral agents, viz., people. They don’t have minds, for one thing, or bodies, for another. The question is whether corporations are similar enough to people to warrant ascriptions of moral agency and responsibility.

In the business ethics literature, French is a seminal thinker on this topic. In early work (1979, 1984), he argued that firms are morally responsible for what they do, and indeed should be seen as “full-fledged” moral persons. He bases this conclusion on his claim that firms have internal decision-making structures, through which they cause events to happen, and act intentionally. Some early responses to French’s work accepted the claim that firms are moral agents, but denied that they are moral persons. Donaldson (1982) claims that firms cannot be persons because they lack important human capacities, such as the ability to pursue their own happiness (see also Werhane 1985). Other responses went further and denied that firms are moral agents. Velasquez (1983, 2003) argues that, while corporations can act, they cannot be held responsible for their actions, because those actions are brought about by the actions of their members. In later work, French (1995) recanted his claim that firms are moral persons, though not his claim that they are moral agents.

Debate about corporate moral agency and moral responsibility rages on in important new work (Orts & Smith 2017; Sepinwall 2016). One issue that has received sustained attention is choice. Appealing to discursive dilemmas, List & Pettit (2011) argue that the decisions of corporations can be independent of the decisions of their members (see also Copp 2006). This makes the corporation an autonomous agent, and since it can choose in the light of values, a morally responsible one. Another issue is intention. A minimal condition of moral agency is the ability to form intentions. Some deny that corporations can form them (S. Miller 2006; Rönnegard 2015). If we regard an intention as a mental state, akin to a belief or desire, or a belief/desire complex, they may be right. But not if we regard an intention in functionalist terms (Copp 2006; Hess 2014), as a plan (Bratman 1993), or in terms of reasons-responsiveness (Silver forthcoming). A third issue is emotion. Sepinwall (2017) argues that being capable of emotion is a necessary condition of moral responsibility, and since corporations aren’t capable of emotion, they aren’t morally responsible. Again, much depends on what it means to be capable of emotion. If this capability can be given a functionalist reading, as Björnsson & Hess (2017) claim, perhaps corporations are capable of emotion (see also Gilbert 2000). Pursuit of these issues lands one in the robust and sophisticated literature on collective responsibility and intentionality, where firms feature as a type of collective. (See the entries on collective responsibility , collective intentionality , and shared agency .)

Another question asked about corporate moral agency is: Does it matter? Perhaps BP itself was morally responsible for polluting the Gulf of Mexico. Perhaps certain individuals at BP were. What hangs on this? Some say: a lot. In some cases there may be no individual who is morally responsible for the firm’s behavior (List & Pettit 2011; Phillips 1995), and we need someone to blame, and perhaps punish. Blame may be the fitting response, and blame (and punishment) incentivizes the firm to change its behavior. Hasnas (2012) says very little hangs on this question. Even if firms are not morally responsible for the harms they cause, we can still require them to pay restitution, condemn their culture, and subject them to regulation. Moreover, Hasnas says, we should not blame and punish firms, for our blame and punishment inevitably lands on the innocent.

3. The ends and means of corporate governance

There is significant debate about the ends and means of corporate governance, i.e., about who firms should be managed for, and who should (ultimately) manage them. Much of this debate is carried on with the large publicly-traded corporation in view.

There are two main views about the proper ends of corporate governance. According to one view, firms should be managed in the best interests of shareholders. It is typically assumed that managing firms in shareholders’ best interests requires maximizing their wealth (cf. Hart & Zingales 2017; Robson 2019). This view is called “shareholder primacy” (Stout 2012) or—in order to contrast it more directly with its main rival (to be discussed below) “shareholder theory”. Shareholder primacy is the dominant view about the ends of corporate governance in business schools and in the business world.

A few writers argue for shareholder primacy on deontological grounds, i.e., by appealing to rights and duties. On this argument, shareholders own the firm, and hire managers to run it for them on the condition that the firm is managed in their interests. Shareholder primacy is thus based on a promise that managers make to shareholders (Friedman 1970; Hasnas 1998). In response, some argue that shareholders do not own the firm. They own stock, a type of corporate security (Bainbridge 2008; Stout 2012); the firm itself may be unowned (Strudler 2017). Others argue that managers do not make, explicitly or implicitly, any promises to shareholders to manage the firm in a certain way (Boatright 1994). More writers argue for shareholder primacy on consequentialist grounds. On this argument, managing firms in the interests of shareholders is more efficient than managing them in any other way (Hansmann & Kraakman 2001; Jensen 2002). In support of this, some argue that, if managers are not given a single objective that is clear and measurable—viz., maximizing shareholder value—then they will have greater opportunity for self-dealing (Stout 2012). The consequentialist argument for shareholder primacy run into problems that afflict many versions of consequentialism: in requiring all firms to aim at a certain objective, it does not allow sufficient scope for personal choice (Hussain 2012). Most think that people should be able to pursue projects, including economic projects, that matter to them, even if those projects do not maximize shareholder value.

The second main view about the proper ends of corporate governance is given by stakeholder theory. This theory was first put forward by Freeman in the 1980s (Freeman 1984; Freeman & Reed 1983), and has been refined by Freeman and collaborators over the years (see, e.g., Freeman 1994; Freeman et al. 2010; Freeman, Harrison, & Zyglidopoulos 2018; Jones, Wicks, & Freeman 2002; Phillips, Freeman, & Wicks 2003). According to stakeholder theory—or at least, early formulations of it—instead of managing the firm in the best interests of shareholders only, managers should seek to “balance” the interests of all stakeholders, where a stakeholder is anyone who has a “stake”, or interest (including a financial interest), in the firm. Blair and Stout’s (1999) “team production” theory of corporate governance offers similar guidance.

To be clear, in a firm in which shareholders’ interests are prioritized, other stakeholders will benefit too. Employees will receive wages, customers will receive goods and services, and so on. The debate between shareholder and stakeholder theorists is about what to do with the residual revenues, i.e., what’s left over after firms meet their contractual obligations to employees, customers, and others. Shareholder theorists think they should be used to maximize shareholder wealth. Stakeholder theorists think they should be used to benefit all stakeholders.

To its critics, stakeholder theory has seemed both incompletely articulated and weakly defended. With respect to articulation, one question that has been pressed is: Who are the stakeholders (Orts & Strudler 2002, 2009)? The groups most commonly identified are shareholders, employees, the community, suppliers, and customers. But other groups have stakes in the firm, including creditors, the government, and competitors. It makes a great deal of difference where the line is drawn, but stakeholder theorists have not provided a clear rationale for drawing it in one place rather than another. Another question is: What does it mean to “balance” the interests of all stakeholders, other than not always giving precedence to shareholders’ interests (Orts & Strudler 2009)? With respect to defense, critics have wondered what the rationale is for managing firms in the interests of all stakeholders. In one place, Freeman (1984) offers an instrumental argument, claiming that balancing stakeholders’ interests is better for the firm strategically than maximizing shareholder wealth (see also Blair & Stout 1999; Freeman, Harrison, & Zyglidopoulos 2018). (Defenders of shareholder primacy say the same thing about their view.) In another, he gives an argument that appeals to Rawls’s justice as fairness (Evan & Freeman 1988; cf. Child & Marcoux 1999).

In recent years, questions have been raised about whether stakeholder theory is appropriately seen as a genuine competitor to shareholder primacy, or is even appropriately called a “theory”. In one article, Freeman and collaborators say that stakeholder theory is simply “the body of research … in which the idea of ‘stakeholders’ plays a crucial role” (Jones et al. 2002). In another, Freeman describes stakeholder theory as “a genre of stories about how we could live” (1994: 413). It may be, as Norman (2013) says, that stakeholder is now best regarded as “mindset”, i.e., a way of looking at the firm that emphasizes its embeddedness in a network of relationships. In this case, there may be no dispute between shareholder and stakeholder theorists.

Resolving the debate between shareholder and stakeholder theorists (assuming they are competitors) will not resolve all or even most of the ethical questions in business. This is because it is a debate about the ends of corporate governance. It cannot answer questions about the moral constraints that must be observed in pursuit of those ends (Goodpaster 1991; Norman 2013), including duties of beneficence (Mejia 2020). Neither shareholder theory nor stakeholder theory is plausibly interpreted as the view that corporate managers should do whatever is possible to maximize shareholder wealth and balance all stakeholders’ interests, respectively. Rather, these views should be interpreted as views that managers should do whatever is consistent with the requirements of morality to achieve these ends. A large part of business ethics is trying to determine what these requirements are.

Answers to questions about the means of corporate governance often mirror answers to question about the ends of corporate governance. Often the best way to ensure that a firm is managed in the interests of a certain party P is to give P control. Conversely, justifications for why the firm should be managed in the interests of P sometimes appeal P’s rights to control it.

Friedman (1970), for example, thinks that shareholders’ ownership of the firm gives them a right to control the firm (which they can use to ensure that the firm is run in their interests). We might see control rights for shareholders as following analytically from the concept of ownership. To own a thing is to have a bundle of rights with respect to that thing. One of the standard “incidents” of ownership is control. (See the entry on property and ownership .)