Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Stress management

Positive thinking: Stop negative self-talk to reduce stress

Positive thinking helps with stress management and can even improve your health. Practice overcoming negative self-talk with examples provided.

Is your glass half-empty or half-full? How you answer this age-old question about positive thinking may reflect your outlook on life, your attitude toward yourself, and whether you're optimistic or pessimistic — and it may even affect your health.

Indeed, some studies show that personality traits such as optimism and pessimism can affect many areas of your health and well-being. The positive thinking that usually comes with optimism is a key part of effective stress management. And effective stress management is associated with many health benefits. If you tend to be pessimistic, don't despair — you can learn positive thinking skills.

Understanding positive thinking and self-talk

Positive thinking doesn't mean that you ignore life's less pleasant situations. Positive thinking just means that you approach unpleasantness in a more positive and productive way. You think the best is going to happen, not the worst.

Positive thinking often starts with self-talk. Self-talk is the endless stream of unspoken thoughts that run through your head. These automatic thoughts can be positive or negative. Some of your self-talk comes from logic and reason. Other self-talk may arise from misconceptions that you create because of lack of information or expectations due to preconceived ideas of what may happen.

If the thoughts that run through your head are mostly negative, your outlook on life is more likely pessimistic. If your thoughts are mostly positive, you're likely an optimist — someone who practices positive thinking.

The health benefits of positive thinking

Researchers continue to explore the effects of positive thinking and optimism on health. Health benefits that positive thinking may provide include:

- Increased life span

- Lower rates of depression

- Lower levels of distress and pain

- Greater resistance to illnesses

- Better psychological and physical well-being

- Better cardiovascular health and reduced risk of death from cardiovascular disease and stroke

- Reduced risk of death from cancer

- Reduced risk of death from respiratory conditions

- Reduced risk of death from infections

- Better coping skills during hardships and times of stress

It's unclear why people who engage in positive thinking experience these health benefits. One theory is that having a positive outlook enables you to cope better with stressful situations, which reduces the harmful health effects of stress on your body.

It's also thought that positive and optimistic people tend to live healthier lifestyles — they get more physical activity, follow a healthier diet, and don't smoke or drink alcohol in excess.

Identifying negative thinking

Not sure if your self-talk is positive or negative? Some common forms of negative self-talk include:

- Filtering. You magnify the negative aspects of a situation and filter out all the positive ones. For example, you had a great day at work. You completed your tasks ahead of time and were complimented for doing a speedy and thorough job. That evening, you focus only on your plan to do even more tasks and forget about the compliments you received.

- Personalizing. When something bad occurs, you automatically blame yourself. For example, you hear that an evening out with friends is canceled, and you assume that the change in plans is because no one wanted to be around you.

- Catastrophizing. You automatically anticipate the worst without facts that the worse will happen. The drive-through coffee shop gets your order wrong, and then you think that the rest of your day will be a disaster.

- Blaming. You try to say someone else is responsible for what happened to you instead of yourself. You avoid being responsible for your thoughts and feelings.

- Saying you "should" do something. You think of all the things you think you should do and blame yourself for not doing them.

- Magnifying. You make a big deal out of minor problems.

- Perfectionism. Keeping impossible standards and trying to be more perfect sets yourself up for failure.

- Polarizing. You see things only as either good or bad. There is no middle ground.

Focusing on positive thinking

You can learn to turn negative thinking into positive thinking. The process is simple, but it does take time and practice — you're creating a new habit, after all. Following are some ways to think and behave in a more positive and optimistic way:

- Identify areas to change. If you want to become more optimistic and engage in more positive thinking, first identify areas of your life that you usually think negatively about, whether it's work, your daily commute, life changes or a relationship. You can start small by focusing on one area to approach in a more positive way. Think of a positive thought to manage your stress instead of a negative one.

- Check yourself. Periodically during the day, stop and evaluate what you're thinking. If you find that your thoughts are mainly negative, try to find a way to put a positive spin on them.

- Be open to humor. Give yourself permission to smile or laugh, especially during difficult times. Seek humor in everyday happenings. When you can laugh at life, you feel less stressed.

- Follow a healthy lifestyle. Aim to exercise for about 30 minutes on most days of the week. You can also break it up into 5- or 10-minute chunks of time during the day. Exercise can positively affect mood and reduce stress. Follow a healthy diet to fuel your mind and body. Get enough sleep. And learn techniques to manage stress.

- Surround yourself with positive people. Make sure those in your life are positive, supportive people you can depend on to give helpful advice and feedback. Negative people may increase your stress level and make you doubt your ability to manage stress in healthy ways.

- Practice positive self-talk. Start by following one simple rule: Don't say anything to yourself that you wouldn't say to anyone else. Be gentle and encouraging with yourself. If a negative thought enters your mind, evaluate it rationally and respond with affirmations of what is good about you. Think about things you're thankful for in your life.

Here are some examples of negative self-talk and how you can apply a positive thinking twist to them:

Practicing positive thinking every day

If you tend to have a negative outlook, don't expect to become an optimist overnight. But with practice, eventually your self-talk will contain less self-criticism and more self-acceptance. You may also become less critical of the world around you.

When your state of mind is generally optimistic, you're better able to handle everyday stress in a more constructive way. That ability may contribute to the widely observed health benefits of positive thinking.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Forte AJ, et al. The impact of optimism on cancer-related and postsurgical cancer pain: A systematic review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2021; doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.09.008.

- Rosenfeld AJ. The neuroscience of happiness and well-being. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2019;28:137.

- Kim ES, et al. Optimism and cause-specific mortality: A prospective cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2016; doi:10.1093/aje/kww182.

- Amonoo HL, et al. Is optimism a protective factor for cardiovascular disease? Current Cardiology Reports. 2021; doi:10.1007/s11886-021-01590-4.

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition. Accessed Oct. 20, 2021.

- Seaward BL. Essentials of Managing Stress. 4th ed. Burlington, Mass.: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2021.

- Seaward BL. Cognitive restructuring: Reframing. Managing Stress: Principles and Strategies for Health and Well-Being. 8th ed. Burlington, Mass.: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2018.

- Olpin M, et al. Stress Management for Life. 5th ed. Cengage Learning; 2020.

- A very happy brain

- Being assertive

- Bridge pose

- Caregiver stress

- Cat/cow pose

- Child's pose

- COVID-19 and your mental health

- Does stress make rheumatoid arthritis worse?

- Downward-facing dog

- Ease stress to reduce eczema symptoms

- Ease stress to reduce your psoriasis flares

- Forgiveness

- Job burnout

- Learn to reduce stress through mindful living

- Manage stress to improve psoriatic arthritis symptoms

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Meditation is good medicine

- Mountain pose

- New School Anxiety

- Seated spinal twist

- Standing forward bend

- Stress and high blood pressure

- Stress relief from laughter

- Stress relievers

- Support groups

- Tips for easing stress when you have Crohn's disease

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Positive thinking Stop negative self-talk to reduce stress

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Exercise cuts heart disease risk in part by lowering stress, study finds

How to realize immense promise of gene editing

Women rarely die from heart problems, right? Ask Paula.

A Harvard study found that women who were optimistic had a significantly reduced risk of dying from several major causes of death over an eight-year period, compared with women who were less optimistic.

Credit: Estitxu Carton/Creative Commons

How power of positive thinking works

Karen Feldscher

Harvard Chan School Communications

Study looks at mechanics of optimism in reducing risk of dying prematurely

More like this.

Can happiness lead toward health?

Having an optimistic outlook on life — a general expectation that good things will happen — may help people live longer, according to a new study from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The study found that women who were optimistic had a significantly reduced risk of dying from several major causes of death — including cancer, heart disease, stroke, respiratory disease, and infection — over an eight-year period, compared with women who were less optimistic.

The study appears online today in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

“While most medical and public health efforts today focus on reducing risk factors for diseases, evidence has been mounting that enhancing psychological resilience may also make a difference,” said Eric Kim , research fellow in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences and co-lead author of the study. “Our new findings suggest that we should make efforts to boost optimism, which has been shown to be associated with healthier behaviors and healthier ways of coping with life challenges.”

The study also found that healthy behaviors only partially explain the link between optimism and reduced mortality risk. One other possibility is that higher optimism directly impacts our biological systems, Kim said.

The study analyzed data from 2004 to 2012 from 70,000 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study, a long-running study tracking women’s health via surveys every two years. They looked at participants’ levels of optimism and other factors that might play a role in how optimism may affect mortality risk, such as race, high blood pressure, diet, and physical activity.

The most optimistic women (the top quartile) had a nearly 30 percent lower risk of dying from any of the diseases analyzed in the study compared with the least optimistic (the bottom quartile), the study found. The most optimistic women had a 16 percent lower risk of dying from cancer; 38 percent lower risk of dying from heart disease; 39 percent lower risk of dying from stroke; 38 percent lower risk of dying from respiratory disease; and 52 percent lower risk of dying from infection.

While other studies have linked optimism with reduced risk of early death from cardiovascular problems, this was the first to find a link between optimism and reduced risk from other major causes.

“Previous studies have shown that optimism can be altered with relatively uncomplicated and low-cost interventions — even something as simple as having people write down and think about the best possible outcomes for various areas of their lives, such as careers or friendships,” said postdoctoral research fellow Kaitlin Hagan, co-lead author of the study. “Encouraging use of these interventions could be an innovative way to enhance health in the future.”

Other Harvard Chan School authors of the study included Professor Francine Grodstein and Associate Professor Immaculata De Vivo, both in the Department of Epidemiology, and Laura Kubzansky, Lee Kum Kee Professor of Social and Behavioral Sciences and co-director of the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness. Harvard Medical School Assistant Professor Dawn DeMeo was also a co-author.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Share this article

You might like.

Benefits nearly double for people with depression

Nobel-winning CRISPR pioneer says approval of revolutionary sickle-cell therapy shows need for more efficient, less expensive process

New book traces how medical establishment’s sexism, focus on men over centuries continues to endanger women’s health, lives

Harvard announces return to required testing

Leading researchers cite strong evidence that testing expands opportunity

When will patients see personalized cancer vaccines?

Sooner than you may think, says researcher who recently won Sjöberg Prize for pioneering work in field

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

How the Power of Positive Thinking Won Scientific Credibility

Psychologist Michael F. Scheier reflects on his groundbreaking 1985 research, which provided the scientific framework for exploring the real power of optimism.

In just the last year, hundreds of academic papers have been published studying the health effects of expecting good things to happen, which researchers call "dispositional optimism." They've linked this positive outlook on life to everything from decreased feelings of loneliness to increased pain tolerance .

Oddly enough, three decades ago, the outlook for research on optimism didn't look very good. But then, in 1985, Michael F. Scheier and Charles S. Carver's published their seminal study , "Optimism, Coping, and Health: Assessment and Implications of Generalized Outcome Expectancies" in Health Psychology . Researchers immediately embraced the simple hopefulness test they included in the paper and their work has now been cited in at least 3,145 other published works. Just as importantly, by testing the effect of a personality variable on a person's physical health, Scheier and Carver helped bridge the gap between the worlds of psychology and biology. After the paper, scientists had a method for seriously studying the healing powers of positive thinking.

In the Q&A below, Scheier reflects on his influential work with Carver and shares how their humble study on human motivation ultimately inspired countless studies on mind-body interactions. He also assesses why their optimism scale was an instant hit in the scientific community, how their findings have been adapted by other researchers, and the future of our understanding of hope and well-being.

How did the research come about?

Chuck Carver from the University of Miami and I were doing research on human motivation. We were trying to understand how to think about goal-directed behavior, and expectancies were an important part of our approach. The idea was, and still is, that when people encounter difficulties doing what it is that they intend to do, some sort of mental calculation takes place that results in the generation of an outcome expectancy -- the person's subjective assessment of the likelihood that he or she will succeed. We thought these expectancies played a role in the nature of the affect that was experienced and the person's subsequent behavior.

Initially, we considered outcome expectancies in a very circumscribed way. We focused on specific situations manipulated in controlled experimental contexts to validate our ideas. For example, we studied snake phobics who approached a boa constrictor in a cage. We weren't interested in snakes or phobias per se but in how these expectations drove behaviors.

At some point in the early 1980s, things changed. A number of our colleagues in health psychology -- my wife, Karen Matthews , included -- urged or maybe even challenged us to consider applying some of our ideas to real-world settings, particularly those that might be relevant to well-being. Our formal area of study in graduate school was also personality, and I started to hear the voice of my advisor, Arnie Buss , in my head gently pushing us to do what it was that we had been trained to do.

This confluence of events started us thinking about expectancies in a broader way that might be more reflective of stable expectancies for positive or negative things to occur. And voila! We found ourselves interested in dispositional optimism, which we define as the general expectation that good, versus bad, things will happen across important life domains.

What were your goals? Was there a research gap you were hoping to fill back then?

Once we knew what we wanted to study, we looked around the literature to see if there was a scale that assessed dispositional optimism that was consistent with how we viewed the construct. We couldn't find anything that was right on the mark, so we set out to make our own measure for dispositional optimism using a self-report questionnaire ( PDF of updated version ). Along with that came the job of establishing the statistical characteristics, or psychometric properties, of the scale. This became part of the purpose of our original paper too.

We also wanted to show that differences in optimism and pessimism predicted some health-relevant outcomes, so we explored the development of physical symptoms reported among a group of undergraduates during a particularly stressful portion of the academic semester. We were fortunate to get the paper published in a journal, Health Psychology , that enabled a lot of researchers to become familiar with the scale, findings, and ideas.

I think one reason the work was picked up so much is that we provided a tool that enabled scientists to ask their own questions and do their own research in the area. Prior to the publication of our scale, there were well-known testimonials on "the power of positive thinking," but there was no simple way to verify if the testimonials were correct. I think it also helped that our scale was easy to use and score. It only has six items on it! The brevity enabled lots of people to include it in their work, even if that involved very large epidemiological studies where issues of respondent burden and time limitations are paramount. As a result, an enormous amount of research on optimism has been generated over the years.

How far has our understanding of optimism come since?

A lot of research has been done since we published our first paper, and the vast majority has examined the relationship of optimism and well-being. I think it's now safe to say that optimism is clearly associated with better psychological health, as seen through lower levels of depressed mood, anxiety, and general distress, when facing difficult life circumstances, including situations involving recovery from illness and disease. A smaller, but still substantial, amount of research has studied associations with physical well-being. And I think most researchers at this point would agree that optimism is connected to positive physical health outcomes, including decreases in the likelihood of re-hospitalization following surgery, the risk of developing heart disease, and mortality.

We also know why optimists do better than pessimists. The answer lies in the differences between the coping strategies they use. Optimists are not simply being Pollyannas; they're problem solvers who try to improve the situation. And if it can't be altered, they're also more likely than pessimists to accept that reality and move on. Physically, they're more likely to engage in behaviors that help protect against disease and promote recovery from illness. They're less likely to smoke, drink, and have poor diets, and more likely to exercise, sleep well, and adhere to rehab programs. Pessimists, on the other hand, tend to deny, avoid, and distort the problems they confront, and dwell on their negative feelings. It's easy to see now why pessimists don't do so well compared to optimists.

What don't we know still?

Two things. First, how do optimism and pessimism develop? We know from studies with twins that dispositional optimism is heritable, although the specific genes that underlie the differences in personality have yet to be identified. It's also likely that parenting styles and early childhood environment play a role. For example, research has shown that children who grow up in impoverished families have a tendency toward pessimism in adulthood. Still, the specifics have not been delineated.

The other missing link has to do with how to construe optimism and pessimism. I've been describing them as though they are opposite ends of a continuum, and this may not be the case. Optimism and pessimism may represent related, but somewhat distinct dimensions. This possibility is suggested by the fact that not expecting bad things to happen, doesn't necessarily imply that the person expects good things to happen. The fact that they're somewhat separable leads to the question of what is important for the beneficial health outcomes we see: the absence of pessimism or the presence of optimism?

What have been some surprising reactions to your research?

Three reactions are noteworthy. One comes from the research community, the second from the media, and the third from patients.

For whatever reason, there has been a group of researchers who have been very skeptical of the findings. The work has been criticized because it's not really optimism and pessimism that drive results, but rather characteristics that are related to optimism, such as the depressed mood that comes along with a pessimistic orientation. Others have found fault with individual studies or large scale reviews that have been done. Much of this criticism is part of the healthy process of science, being dubious and wanting further verification, but some of the skepticism seems to go beyond that. It's never been clear to me why this has been the case.

As for the media, they seem to love the work. Whenever a major study gets published showing the benefits of optimism on health, the findings are picked up quickly and get widely distributed. Part of this is prompted, I think, by folklore that surrounds the concepts of optimism and pessimism. I think that people are intrigued that these caricatures have some basis in fact. Whatever the reason, our findings are quick to make their way to the public.

But perhaps what's most salient to me is the reaction that some patients have expressed about their recovery. They have told me that they feel guilty. They read that optimism is associated with better health among patients recovering from illness, and they think, "If only I would be more optimistic, I'd do better." Yet, they can't put themselves in that frame of mind. Family members may chastise them too for not promoting their recovery by simply expecting good things to happen. Perhaps it was naïve not to have imagined these reactions. Regardless, it is troubling that they have occurred.

How has this study affected your life?

My guess is that, if you asked the research community what I'm known for, they'd say the work that I've done on optimism and pessimism. I've spent the better part of my professional life studying optimism and it's effect on psychological and physical well-being. So if I'm known for something, it might as well be that. Still, the salience of this work has distracted people from other work that I've done that I think is equally interesting, including some of the ideas we've expressed about why people experience emotion.

I also spend a fair amount of time trying to figure out if I'm more optimistic or pessimistic, or how my wife and kids are. I'm guessing that I'm somewhere in the middle, which puts me in some sort of expectational limbo. On the other hand, maybe that view provides the detachment that is necessary to allow a researcher to approach work in an objective way.

Ultimately, I find it very gratifying that a large number of colleagues in the field have found the work valuable enough to incorporate into their own work. Collectively, we've been able to document that links between optimism and physical health do exist.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Think Positive

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Marko Geber / Getty Images

You have probably heard a thing or two about the benefits of positive thinking . Research suggests that positive thinkers have better stress coping skills, stronger immunity, and a lower risk of cardiovascular disease.

While it is not a health panacea, taking an optimistic view rather than ruminating on negative thoughts can benefit your overall mental well-being. Fortunately, there are things that you can do to learn how to think more positively.

Benefits of Thinking Positively

Being a positive thinker can have a number of important health benefits. In one study, researchers found that people who had a more optimistic outlook had a lower risk of dying of a number of serious illnesses including:

- Breast cancer

- Colorectal cancer

- Heart disease

- Lung cancer

- Ovarian cancer

- Respiratory diseases

Studies have also shown that optimists tend to be both physically and mentally healthier than their more pessimistic counterparts. For example, research has shown that thinking more positively is associated with improved immunity, increased resilience to stress, and lower rates of depression.

How to Think More Positively

So what can you do to become a more positive thinker? A few common strategies involve learning how to identify negative thoughts and replacing these thoughts with more positive ones. While it might take some time, eventually you may find that thinking positively starts to come more naturally.

Avoid Negative Self-Talk

Self-talk involves the things you mentally tell yourself. Think of this as the inner voice inside your mind that analyzes how you perform and interact with the world around you. If your self-talk centers on negative thoughts , your self-esteem can suffer.

So what can you do to combat these negative self-talk patterns? One way to break the pattern is to start noticing when you have these thoughts and then actively work to change them.

When you start thinking critical thoughts about yourself, take a moment to pause and assess.

Paying attention to your self-talk is a great place to start when trying to think more positively. If you notice that you tend to engage in negative self-talk, you can start looking for ways to change your thought patterns and reframe your interpretations of your own behaviors.

It can be tough to stay optimistic when there is little humor or lightheartedness in your life. Even when you are facing challenges, it is important to remain open to laughter and fun.

Sometimes, simply recognizing the potential humor in a situation can lessen your stress and brighten your outlook. Seeking out sources of humor such as watching a funny sitcom or reading jokes online can help you think more positive thoughts.

Cultivate Optimism

Learning to think positively is like strengthening a muscle; the more you use it, the stronger it will become. Researchers believe that your explanatory style , or how you explain events, is linked to whether you are an optimist or a pessimist.

Optimists tend to have a positive explanatory style. If you attribute good things that happen to your skill and effort, then you are probably an optimist.

Pessimists, on the other hand, usually have a negative attributional style. If you credit these good events to outside forces, then you likely have a more pessimistic way of thinking.

The same principles hold true for how you explain negative events. Optimists tend to view bad or unfortunate events as isolated incidents that are outside of their control while pessimists see such things as more common and often blame themselves.

By taking a moment to analyze the event and ensure that you are giving yourself the credit you are due for the good things and not blaming yourself for things outside of your control, you can start to become more optimistic.

Practice Gratitude

Consider keeping a gratitude journal where you can regularly write about the things in life that you are grateful for. Research has found that writing down grateful thoughts can improve both your sense of optimism as well as your overall well-being.

When you find yourself dwelling on more negative thoughts or feelings, spend a few minutes writing down a few things in life that bring you joy. This simple activity can help shift your focus to a more optimistic mindset.

Keep Practicing

There is no on-off switch for positive thinking. Even if you are a natural-born optimist, thinking positively when faced with challenging situations can be difficult. Like any goal, the key is to stick with it for the long term. Even if you find yourself dwelling on negative thoughts, you can look for ways to minimize negative self-talk and cultivate a more optimistic outlook.

Finally, do not be afraid to enlist the help of friends and family.

When you start engaging in negative thinking, call a friend or family member whom you can count on to offer positive encouragement and feedback.

Remember that to think positively, you need to nurture yourself. Investing energy in things you enjoy and surrounding yourself with optimistic people are just two ways that you can encourage positive thinking in your life.

When to Seek Help

If you are finding it difficult to think positively and instead feel like negative thoughts or emotions are taking over your life, you should talk to your doctor or therapist. Negative emotions that are causing distress or interfering with your ability to function normally may be a sign of a mental health condition such as depression or anxiety .

A doctor or mental health professional can evaluate your symptoms and recommend treatments that can help. Psychotherapy and medications may be used to address symptoms and improve your ability to think more positively.

A Word From Verywell

Learning how to think positively is not a quick fix, and it is something that may take some time to master. Analyzing your own thinking habits and finding new ways to incorporate a more positive outlook into your life can be a great start toward adopting a more positive thinking approach.

Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. The heart's content: the association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health . Psychological Bulletin , 2012;138(4):655-91. doi:10.1037/a0027448

Kim ES, Hagan KA, Grodstein F, DeMeo DL, De Vivo I, Kubzansky LD. Optimism and cause-specific mortality: a prospective cohort study . Am J Epidemiol . 2017;185(1):21-29. doi:10.1093/aje/kww182

Segerstrom SC, Sephton SE. Optimistic expectancies and cell-mediated immunity: the role of positive affect . Psychol Sci . 2010;21(3):448-455. doi:10.1177/0956797610362061

Naseem Z, Khalid R. Positive thinking in coping with stress and health outcomes: literature review . Journal of Research and Reflections in Education , 2010;4(1):42-61.

Santos V, Paes F, Pereira V, et al. The role of positive emotion and contributions of positive psychology in depression treatment: systematic review . Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health . 2013;9:221-237. Published 2013 Nov 28. doi:10.2174/1745017901309010221

Gillham JE, Shatté AJ, Reivich KJ, Seligman MEP. Optimism, pessimism, and explanatory style . In: Chang EC, ed. Optimism & Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001:53-75. doi:10.1037/10385-003

Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Gratitude and well being: the benefits of appreciation . Psychiatry (Edgmont) . 2010;7(11):18-22.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

What Is Positive Psychology? A Starting Point

In doing so, it attempts to answer several key questions, including: What is the good life? And, what makes life worth living?

Positive psychology does not suggest that we should dismiss the rest of psychology or that therapists should ignore the very real problems people face (Snyder, 2021).

Here, we bring together many of our most popular articles, exploring this exciting and rapidly developing area of research and its application to human wellbeing.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains

What is positive psychology an introduction, positive psychology vs traditional psychology.

- Martin Seligman & the History of Positive Psychology

Why Is Positive Psychology Important?

6 examples of positive psychology in practice, 5 key concepts and topics in positive psychology, 4 theories, principles, and models explained, is positive psychology evidence-based 60+ research findings, positive psychology in therapy and coaching, applied positive psychology in the workplace and education, 30+ positive psychology techniques to apply, 20+ popular interventions for your sessions, 28 exercises and activities for individuals and groups, helpful worksheets, workbooks, and resources, assessment tools: 24 tests, questions, and questionnaires, positive psychology training: 20+ bachelor’s degrees and master’s programs, 100+ best courses and online options, 270+ fascinating positive psychology books, common criticisms of positive psychology, a take-home message.

“Positive psychology is the scientific study of what makes life most worth living” (Snyder, 2021, p. XXIII). While not rejecting the psychology that has gone before, it redresses a previous imbalance by focusing attention on our strengths as much as our weaknesses and fostering our most fulfilling lives while repairing the worst (Snyder, 2021).

Positive psychology is more than a one-sided focus on positive thinking and emotions; it uses science-led research to uncover “what makes individuals and communities flourish, rather than languish” (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019, p. 2).

In our article What Is Positive Psychology & Why Is It Important? , we learn more about what positive psychology is and is not. We also clear up some misunderstandings and introduce the tools and techniques that enhance clients’ wellbeing in therapy and outside, in education, the workplace, and beyond.

Positive psychology complements – rather than replaces – traditional psychology (sometimes referred to as the “disease model”), fostering wellbeing in individuals through identifying and cultivating virtues and strengths and creating a path toward meaningful and valued living (Seligman, 2011).

While traditional psychology is typically viewed as studying and treating “disease, weakness, and damage” – or what went wrong – positive psychology focuses on “strength and virtue” and “building on what is right” in our lives (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019, p. 5).

Martin Seligman & the History of Positive Psychology

It then continues by laying out the four waves of psychology that went before its introduction.

In Who Is Martin Seligman and What Does He Do? , we gain a deeper understanding of Seligman’s work on learned helplessness, character strengths, and virtues, along with the introduction of (perhaps) the definitive model of optimal human functioning and wellbeing: the PERMA model (Seligman, 2011; Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019).

In the decades since Seligman’s presidency, positive psychology has gained momentum, with a wealth of supporting research and therapeutic interventions taking the theory and practice further and becoming an established field of study in many high-profile academic institutions (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019).

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

The benefits of positive psychology are many and varied. Most importantly, they are backed up by theory and research and have become an established part of many coaches’, counselors’, and therapists’ toolkits.

The importance and benefits of the approach have been recognized in research through the identification of many triggers and their consequences associated with flourishing and wellbeing, including the following (Snyder, 2021; Lomas et al., 2014).

- Positive emotions are contagious in the workplace, boosting job performance and, ultimately, customer satisfaction.

- Small, simple changes can have a huge impact on creating a fulfilling and meaningful life.

- Focusing on happiness in the present should be accompanied by thinking about our past and future to create meaning.

- Giving creates more meaning in life, but taking can increase happiness in the present. Therefore, by giving back to others while showing gratitude and accepting people’s kindness, it is possible to create a meaningful yet happy existence.

- Positive emotions, such as happiness, are contagious. It is vital to recognize the impact we can have on others and their effect on us.

Positive psychology is vital and exciting because it studies and attempts to understand and promote optimal functioning by stimulating the factors that allow individuals and communities to flourish.

Importantly, positive psychology is not solely a focus on what makes life better. It is more than a prescription for happiness. It is facilitative, encouraging us to identify and use our strengths and virtues to overcome difficult times and create a more fulfilling life (Lomas et al., 2014).

In What Is Applied Positive Psychology? , we learn that the approach is successful for those seeking help and, equally, for those unaware it is needed. By adopting a theory that attends to what goes right in life, making it worthwhile and meaningful, therapists can work with clients to determine and steer them toward their goals.

Positive psychology is so powerful and far reaching that it is being theoretically explored and practically applied in a diverse range of fields of human endeavors, including:

- Social work

- Economics and politics

- Management and leadership

- Business organization

The wide-ranging practical application of positive psychology is evident when we consider that it “encompasses the entire field of psychology”; indeed, “links can be drawn to humanistic psychology, psychiatry, sociology, biology” and far beyond (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019, p. 13).

As we see below, and in our article sharing positive psychology examples , when applied directly or as part of other approaches, positive psychology can positively impact therapy and counseling , education , parenting , the workplace , and even specific communities, such as through building a positive community .

We have included several topics below, along with articles written to better understand the key concepts in more detail.

While we have an immense range of emotions, we often recognize very few (such as being happy, sad, and angry). Each feeling we experience has a strong and intimate connection with our cognition and behavior.

Becoming more aware of our emotions and the difference between positive and negative ones is extremely helpful to our wellbeing (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019), as explored in the following articles:

- Understanding Emotions: 15 Ways to Identify Your Feelings

- What Are Positive and Negative Emotions and Do We Need Both?

- What Are Negative Emotions and How to Control Them?

- What Are Positive Emotions in Psychology? (+List & Examples)

- The Pursuit of Happiness: Using the Power of Positive Emotions

Character strengths and Values in Action

Knowing and using our character strengths and values can boost our positive emotions and engagement (Niemiec, 2018). In the following articles, we explore their importance to positive psychology and individual wellbeing.

- Understanding the CliftonStrengths™ Assessment: A Guide

- Strength-Spotting Interviews: 20+ Questions and Techniques

- Strength-Based Leadership: 34 Traits of Successful Leaders

- 10+ Ways to Build Character Strengths at Work (& Examples)

“Resilience is actually about managing emotions, not suppressing them” and finding a way forward during difficult times; crucially, it can be grown (Neenan, 2018, p. 9). As such, it is a key feature of positive psychology and learning to flourish (Seligman, 2011).

- Resilience Counseling: 12 Worksheets to Use in Therapy

- 5+ Ways to Develop a Growth Mindset Using Grit and Resilience

- Resilience Theory: A Summary of the Research (+PDF)

- What Is Emotional Resilience? (+6 Proven Ways to Build It)

Growth and psychological development are “supported and characterized by intrinsic motivation and active internalization and integration” (Ryan & Deci, 2018, p. 100). The following articles explore motivation and its importance to performance and, ultimately, wellness.

- Intrinsic Motivation Explained: 10 Examples & Key Factors

- What Is Extrinsic Motivation? (Incl. Types & Examples)

- How to Increase Intrinsic Motivation (According to Science)

While reflection is crucial to wellness, so too is learning how “to form intentions and to direct oneself towards a certain path or goal” (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019, p. 158). The following articles introduce why goal setting is key and how it can be performed.

- Goal Setting: 20 Templates & Worksheets for Achieving Goals

- How to Set and Achieve Life Goals the Right Way

In this section, we explore several of the models, theories, and principles that combine multiple elements of positive psychology and how they can be applied.

PERMA model

Perhaps the most pervasive model within positive psychology is Seligman’s (2011) own: the PERMA model (Csikszentmihalyi, 2016).

The articles Martin Seligman’s Positive Psychology Theory and Seligman’s PERMA+ Model Explained: A Theory of Wellbeing provide the ideal introduction.

The five elements that make up the PERMA acronym form the foundation of a flourishing life and a helpful breakdown for working with clients. The following three intrinsic properties characterize each one:

- They contribute to wellbeing.

- They are pursued for their own sake.

- They can be measured and defined individually.

We include each one below along with additional links for more information:

- Positive emotions Fostering our feel-good emotions helps build our skills and resources, improving relationships and creativity.

Check out Positive Mindset: How to Develop a Positive Mental Attitude .

- Engagement When we experience flow, our concentration is heightened, causing us to ignore distractions and perform optimally.

Check out Flow at Work: How to Boost Engagement in the Workplace .

- Relationships Forming relationships and connecting with others is a fundamental human need and helps ensure our health and happiness.

Check out What Is Social Wellbeing? 12+ Activities for Social Wellness .

- Meaning “Meaning within life is essential to fulfilled individuals,” and searching for it may be more important than chasing happiness (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019, p. 98).

Check out 9 Powerful Existential Therapy Techniques for Your Sessions , 15 Ways to Find Your Purpose of Life & Realize Your Meaning , and What Is the Meaning of Life According to Positive Psychology ?

- Accomplishments Those who feel personally engaged and involved in achieving their goals typically experience better health. We must all become better at goal setting and goal achievement for a fulfilling life.

Check out The Science & Psychology of Goal Setting 101 .

Hope theory

Hope (while difficult to define) is a powerful positive emotion that can benefit our lives and help us achieve our goals (Tomasulo, 2020).

In What Is Hope in Psychology? + 7 Exercises & Worksheets , you can find out more about the potential of hope to strengthen your resolve, bolster your resilience, and overcome the most challenging obstacles.

While an important theory and set of practical applications for positive psychology, it is a therapy in its own right and can be explored further in How to Perform Hope Therapy: 4 Best Techniques .

Flow theory

Those moments, however fleeting, when we feel totally immersed in an activity, oblivious to time or our environment, are described as flow by psychologists (Csikszentmihalyi, 2016).

What Is Flow in Psychology? explores this highly enjoyable state of being that has the potential to heighten our creativity, productivity, and happiness, even when performing the most mundane tasks.

In the article Flow Theory in Psychology , we further explore the theory of flow and assess its potential to impact our lives positively, as well as its role in work, education, and sports.

The Sailboat Metaphor

For those new to positive psychology or getting to grips with its terminology, it can be helpful to adopt a metaphor. In PositivePsychology.com’s Sailboat Metaphor , we learn how to create a common language for therapy sessions and interventions that requires little upfront knowledge yet can stimulate ongoing discussions and insights.

The theory and practice of positive psychology are research led; each aspect of the approach is backed by “science that focuses on the development and facilitation of a flourishing environment and individuals” (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019, p. 2).

Over the last few decades, a great deal of research has confirmed the principles of positive psychology and the benefits that related interventions have on our wellbeing and moving toward more fulfilling lives (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019; Seligman, 2011; Snyder, 2021).

We have several articles that include further information on such research findings.

- Money does not influence happiness as much as we may think (Aknin et al., 2009).

- Gratitude is a big contributor to our happiness (Seligman et al., 2005).

- Authenticity is more important to a sense of meaning than putting on a pretense of happiness (Baumeister et al., 2012).

- Being generous to others with our time and money leads to greater happiness for the giver (Baumeister et al., 2012).

- Job satisfaction (Spector, 1986; Miglianico et al., 2020; Hartmann et al., 2020)

- Positive coping (Langford et al., 1997)

- Self-worth (Langford et al., 1997)

- Psychological wellbeing (Langford et al., 1997)

- Commitment (Spector, 1986; Castka et al., 2001; Miglianico et al., 2020; Hartmann et al., 2020)

- Information sharing (Castka et al., 2001)

- Continuous learning (Castka et al., 2001)

- Adaptivity (Miglianico et al., 2020; Hartmann et al., 2020)

- Learning skills faster

- Greater insight into the origins of consciousness

- Improved workplace design

- Invest in their own and their employees’ strengths

- Surround themselves with a good team

- Understand and meet the needs of their followers

- Cardiovascular health (via increased work engagement; Bakker et al., 2014)

- Job performance (work engagement; Bakker et al., 2014)

- Productivity (happiness; Wright & Cropanzano, 2007)

- Satisfaction (work engagement; Bakker et al., 2014)

Positive psychology is backed by science and shaped by research. The theory and interventions continue to be challenged and tested to ensure that it remains at the forefront of scientific research.

Here are two articles that provide useful positive psychology maps for counseling and therapy:

- Applied Positive Psychology Coaching: The Ultimate Guide

- Applied Positive Psychology in Therapy: Your Ultimate Guide

Other favorite topics include:

General skills

Learning communication, social, and parenting skills can support coping and build on our existing positive emotions, benefiting clients inside and outside treatment (Magyar-Moe, 2009).

- Providing Psychoeducation in Groups: 5 Examples & Ideas

- How to Improve Communication Skills: 14 Best Worksheets

- Relationship Therapy Sessions: 45 Questions & Worksheets

- Social Skills Training for Adults: 10 Best Activities + PDF

Positive psychology in therapy builds upon individuals’, couples’, and families’ strengths (Conoley & Conoley, 2009). The following articles embrace many of the principles of the positive psychology approach.

- What Is Positive Psychotherapy? (Benefits & Model)

- What Is ACT? The Hexaflex Model and Principles Explained

- What Is Marriage Psychology? +5 Relationship Theories

- 19 Best Narrative Therapy Techniques & Worksheets [+PDF]

Positive psychology offers a powerful stimulus to coaching sessions, encouraging clients to live their best lives (Driver, 2011).

- What Is the GROW Coaching Model? (Incl. Examples)

- Health Coaching: Your Ultimate Template Toolkit for Success

- 11 Best Tools & Questions for Work-Life Balance Coaching

- 18 Financial Coaching Worksheets, Software & Tools

Positive psychology is less about prescribing behavior and more about facilitating a meaningful life (Lomas et al., 2014).

As such, positive psychology has the potential to be used in a wide variety of situations and with various clients beyond therapy, counseling, and coaching.

The following articles include applications in education, criminology, and at work.

- Positive Psychology in Education: Your Ultimate Guide

- What is Positive Criminology? (+ 14 Theories & Worksheets)

- What Is Positive Organizational Psychology?

For further examples, see the article What Is Applied Positive Psychology?

The following articles offer a sample of the many techniques available that are inspired by or closely aligned to the principles of positive psychology.

- 12 Inspiring Real-Life Positive Psychology Examples – This article introduces five of the most popular positive psychology interventions and how to use them.

- The Science of Coping: 10+ Strategies & Skills (Incl. Wheel) – Our lives are more difficult when we are overwhelmed and stressed, yet there are helpful techniques that support our ability to cope.

- What Is Openness to Experience & How Do We Measure It? – Being open to new opportunities contributes to our authenticity and wellbeing and increases our engagement in relationships and activities.

- Visualization in Therapy: 16 Simple Techniques & Tools – Our imagination can help us explore aspects of our self and possible futures and promote behavior change.

- How to Apply the Wheel of Life in Coaching – One of our favorites for achieving balanced living, the wheel of life helps clients identify and fulfill each of their psychological needs.

- 19 Top Positive Psychology Interventions + How to Apply Them – These techniques focus on building strengths and promoting wellbeing, rather than dwelling on problems.

Activities for individuals and groups that promote wellbeing and life fulfillment can occur inside and outside treatment sessions.

The following offer some valuable ideas for exercises and activities.

- Your Ultimate Online Group Coaching Toolkit (+ Exercises) – This article explores how to set up and structure coaching sessions and introduces some of the best activities and exercises available.

- 19 Top Positive Psychology Exercises for Clients or Students – These exercises support the central tenets of positive psychology, building on clients’ strengths and helping them experience more satisfying and fulfilling lives.

- How to Successfully Teach Positive Psychology in Groups – Positive psychology can be taught to students and clients through a series of exercises that increase positive emotions, behaviors, and thinking in groups.

The following articles include some of our most effective downloads for promoting positive psychology and implementing the tools and techniques that support wellness and working toward life fulfillment.

- 8 PERMA Model Activities and Worksheets to Apply With Clients – These vital downloads support Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model, overcoming challenges while helping live more enriched lives.

- 56 Free Positive Psychology PDF Handouts – These exceptional downloads promote self-awareness, problem-solving, replacing irrational beliefs, and fostering core values and beliefs.

- How to Overcome Perfectionism: 15 Worksheets & Resources – Setting impossibly high standards may lead to increased self-criticism. The techniques within this article help clients recognize that our imperfections and vulnerability are not failings.

- How to Use Mindfulness Therapy for Anxiety: 15 Exercises – The mindfulness workbooks and worksheets help clients develop awareness and a sense of compassion and can reduce anxiety (Shapiro, 2020) by reducing or removing judgment.

The following articles include key assessments, questions, and questionnaires that can be used alongside positive psychology coaching and therapy.

- 5 Quality of Life Questionnaires and Assessments – Recognizing a person’s attitude toward life and their values is particularly valuable in positive psychology.

- 10 Positive Psychology Surveys, Measures, and Questionnaires – These research-led tools have been created to capture life satisfaction, gratitude, and flow scores and can be used in research or treatment.

- 3 Most Accurate Character Strengths Assessments and Tests – Backed up by research, these three character strengths assessments are invaluable for coaching sessions.

- 6 Happiness Tests & Scales to Measure Happiness – Several scientifically validated tests and surveys are available to measure happiness.

Becoming effective as a positive psychologist, coach, or therapist requires training and typically begins at college. The following sample of bachelor’s degrees and master’s programs are available at the time of writing but should be followed up by a thorough online search.

- 20 Top Positive Psychology Degrees & Certificates – This article contains an invaluable list of some of the best institutions for higher study in positive psychology.

- Master of Applied Positive Psychology: The MAPP Program – While the Master of Applied Positive Psychology degree is typically considered the gold standard of training in this exciting field, there are other opportunities to explore as well, which we mention below.

While not necessarily specific to positive psychology, the following course articles offer coaches and therapists valuable educational (online and in-person) opportunities to hone their skills.

- 19 Best Coaching Training Institutes and Programs

- 20 Coaching Courses and Online Opportunities

- How to Become a Relationship Coach: 7 Certification Courses

- Emotional Intelligence Certification & Coaching Programs

- 6 Best Executive Coaching Certifications & Training Programs

- What Is Leadership Coaching? (Including Certification Options)

- How To Become a Therapist: Types & Requirements

- Training in Narrative Therapy: 21 Courses & Online Options

- 18 Behavioral Therapist Certifications & Training Courses

- Training in Educational Psychology: 22 Master’s & Degrees

Before signing up, it is worth considering their location (for example, onsite or remote), cost, and what certification and accreditations are needed for your future career and area.

We have included some of our favorites below, along with others outside the field that bring additional insights.

Books on all aspects of positive psychology

- 88+ Must-Read Positive Psychology Books

- Fostering Self-Forgiveness: 25 Powerful Techniques and Books

- How to Improve Self-Knowledge: 21 Books, Tests, and Questions

- 18 Psychology Books on Authenticity and Being Your True Self

- 27 Books to Improve Self-Esteem, Self-Worth, and Self-Image

- 7 Best Books to Help You Find the Meaning of Life

Coaching and therapy books

- The Top-20 Life Coaching Books You Should Read

- 14 Must-Read Acceptance & Commitment Therapy Books

- 15 Motivational Interviewing Books to Help Clients Change

- 30 Best CBT Books to Master Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Books on other skills and areas of psychology

- Building Assertiveness Skills: Top 12 Books & Workbooks

- 20 Best Sports Psychology Books for Motivating Athletes

- The 20 Best Books on Appreciative Inquiry

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

In our article defining positive psychology , we learn about people’s common misconceptions and some of the most common criticisms, including:

- It is not possible to be perpetually happy.

- The focus is too much on the individual.

- There is a cultural and ethnocentric bias.

- There is too much emphasis on self-report.

While positive psychology’s creation and ongoing development are driven by research (and typically well validated), it is vital to consider its challenges and what learning or new areas of scientific study they offer.

Positive psychology is the scientific study of what makes individuals, couples, families, and communities flourish. It attempts to answer the difficult questions of what makes us happy and our existence meaningful.

Positive psychology is not simply a focus on what is good in our lives; it recognizes the troubles we face and the obstacles we overcome.

While aware of the psychological theories and ideas that have gone before, Seligman (2011) and others have created a series of models and approaches that direct research, coaching, and therapy toward helping us create fulfilling lives that focus on our strengths rather than our weaknesses.

Research has already identified considerable successes in using positive psychology with diverse populations in various situations, including the workplace, education, and healthcare.

The potential of this relatively recent approach to understanding and improving the human condition is considerable. By following the links within the article, it is possible to explore in depth the vast body of research and literature on positive psychology and pick up many of the powerful techniques, skills, and tools for use in your own or your clients’ lives.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Aknin, L. B., Norton, M. I., & Dunn, E. W. (2009) From wealth to well-being? Money matters, but less than people think. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 523–527.

- Attridge, M. (2008). A quiet crisis: The business case for managing employee mental health . Human Solutions.

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior , 1 (1), 389–411.

- Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., Aaker, J., & Garbinsky, E. N. (2012). Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. Journal of Positive Psychology, 8, 505–516.

- Boniwell, I., & Tunariu, A. D. (2019). Positive psychology: Theory, research and applications . Open University Press.

- Castka, P., Bamber, C. J., Sharp, J. M., & Belohoubek, P. (2001). Factors affecting successful implementation of high performance teams. Team Performance Management: An International Journal , 7 (7–8), 123–134.

- Conoley, C. W., & Conoley, J. C. (2009). Positive psychology and family therapy: Creative techniques and practical tools for guiding change and enhancing growth . Wiley.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2016). Flow and the foundations of positive psychology: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi . Springer.

- Driver, M. (2011). Coaching positively: Lessons for coaches from positive psychology . Open University Press.

- Hartmann, S., Weiss, M., Newman, A., & Hoegl, M. (2020). Resilience in the workplace: A multilevel review and synthesis. Applied Psychology , 69 (3), 913–959.

- Langford, C. P. H., Bowsher, J., Maloney, J. P., & Lillis, P. P. (1997). Social support: A conceptual analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 25 (1), 95–100.

- Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Ivtzan, I. (2014). Applied positive psychology: Integrated positive practice . Sage.

- Magyar-Moe, J. L. (2009). Therapist’s guide to positive psychological interventions . Academic Press.

- Miglianico, M., Dubreuil, P., Miquelon, P., Bakker, A. B., & Martin-Krumm, C. (2020). Strength use in the workplace: A literature review. Journal of Happiness Studies , 21 (2), 737–764.

- Neenan, M. (2018). Developing resilience: A cognitive-behavioural approach . Routledge.

- Niemiec, R. M. (2018). Character strengths interventions: A field guide for practitioners . Hogrefe.

- Rath, T. (2017). Strengths based leadership: Great leaders, teams, and why people follow . Gallup Press.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2018). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness . Guilford Press.

- Seligman, M. E. (2011). Authentic happiness . Random House Australia.

- Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, S. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60 , 410–421.

- Shapiro, S. L. (2020). Rewire your mind: Discover the science + practice of mindfulness . Aster.

- Snyder, C. R. (2021). The Oxford handbook of positive psychology . Oxford University Press.

- Spector, P. E. (1986). Perceived control by employees: A meta-analysis of studies concerning autonomy and participation at work. Human Relations , 39 (11), 1005–1016.

- Tomasulo, D. (2020). Learned hopefulness: The power of positivity to overcome depression . New Harbinger.

- Wright, T. A., & Cropanzano, R. (2007). The happy/productive worker thesis revisited. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management , 26 , 269–307.

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Applying Positive Psychology at Work: Your Ultimate Guide

In 1998, positive organizational psychology at work gained legitimacy when the father of the movement, Martin Seligman, chose it as the theme for his term [...]

What Is Validation in Therapy & Why Is It Important?

Validation means that you understand where the other person is coming from, even if you disagree with what they say or do (Rather & Miller, [...]

How to Build Rapport With Clients: 18 Examples & Questions

As every good clinician knows, diving into deep discussions without first establishing rapport is a sure-fire way to derail the therapeutic process. It can also [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

- IE Corporate Relations

- IE University

Positivity Is Not Magic. It’s Science.

Achieving workplace positivity comes down to neuroscience and psychology, not mystery and chance, writes Ana García Villas-Boas.

How can I keep my team motivated in the face of uncertainty? How can I inspire individuals to be proactive and take action? How can I encourage innovation? These are just some of the questions I hear from my clients these days. Leading people has always been a challenge – and these days particularly so, thanks to the pandemic and the increased stress it has caused for organizations and the people inside them.

Thus, in addition to the traditional business activities, leaders must now manage the emotions of their teams. To do this, leaders must also manage their own emotions more mindfully and learn to focus on and prioritize their own self-care.

Yet, the end of the quarter is always looming, the bottom line ever-present. So how can leaders keep this in mind, sustain motivation and productivity among workers while conveying a sense of calmness? Advances in neuroscience and the science of positive psychology provide insight here.

Barbara Fredrickson, a professor of Psychology and Director of the Positive Emotions and Psychophysiology Laboratory at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has been investigating the effect of positive emotions for more than thirty years. Her research shows that people with a positive attitude overcome difficulties more quickly and are more resilient. Based on her research, she developed the broaden-and-build theory , which uses positive emotions to solve developmental and growth challenges instead of solving survival issues.

A positive mindset is the breeding ground for creativity, expansive and visionary thinking, empathy, cooperation, and connection. Moreover, broadening one’s mindset makes people better equipped to overcome adversity. Her findings shed light on how people with a positive mindset become stronger and develop exponentially in overcoming obstacles. In the world of business, Frederickson’s research shows that high-performing teams use at least a 3:1 ratio of positive messages as opposed to negative ones.

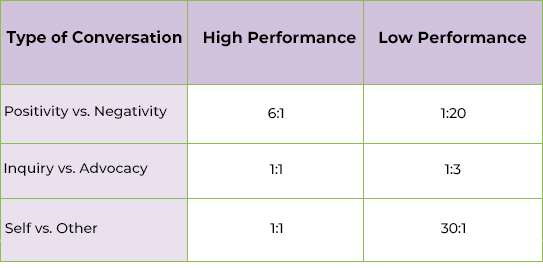

Marcial Losada and Emily Heaphy, who studied the impact of team conversations , calculate that the ratio of positive versus negative interactions in high-performing teams is 6:1. Their research clearly demonstrates the impact of the type of conversations on team performance, and therefore on results:

The first question leaders should ask themselves is: what type of conversations do we have amongst the team? in the hallways? via email and web chats? with superiors and with colleagues? Are these productive conversations or do they stir up emotions that are unproductive, even toxic and destructive?

Resonant leaders attract while dissonant leaders repel. Richard Boyatzis, a professor at Case Western University, has studied the relationship between inspirational leadership and its impact on relationships from a neuroscience perspective. In their book, Primal Leadership: Unleashing the Power of Emotional Intelligence , Boyatzis, Daniel Goleman, and Annie McKee coined the term “resonant leader” to describe a figure who is “attuned to people’s feelings” and “moves them in a positive emotional direction.”

Thanks to advances in magnetic resonance research on the movement of brain neurons, studies have shown that resonant leaders connect and activate one part of the brain, while dissonant leaders, who send out negative emotions, activate another part of the brain. This is produced by the effect of mirror neurons which, as their name indicates, reproduce the reflection of what they perceive. This brain-to-brain transmission takes place primarily below consciousness.

Resonant leaders turn on brain circuitry that makes people become receptive to new ideas and enables them to observe and analyze business and social environments. However, a different circuit is triggered in dissonant leaders. The socializing brain circuit is disabled and the areas of the brain that focus on problem-solving and efficient job performance are activated. When the task-execution circuit is turned on, the circuit that activates receptiveness to new ideas and environmental observation is turned off.

Therefore, when leaders help people around them to feel positive, these people are receptive to building relationships; they can think creatively and they are open to different ideas, thus ratifying Frederickson’s broaden-and-build theory. Dissonant leaders, however, have the opposite effect – by focusing primarily on weaknesses and problems, these leaders make others feel threatened and activate their brain’s survival mode, which literally encourages them to flee.

What can leaders do to ensure teams are motivated and with a positive attitude?

- Use consistently positive language. Construct sentences around what you want to achieve and avoid what you don’t want. For example, instead of saying “we cannot afford the number of incidents to increase,” say “let’s do everything we can to increase service quality and decrease the number of incidents.”

- Look on the bright side. Try starting meetings with an appreciative warmer by asking, “What is the best thing that has happened to you this week? What has been the best business or customer service interaction?” These simple questions tap into positive emotions and activate the brain’s circuitry of expansion, building, and connection.

- Ask generative questions that focus on making the best of the situation, and even improving it. For example, when is your customer most satisfied? How can everyone contribute to the success of this project? If you were starting the project from scratch, how would you go about it? What is important to you in this particular project?

- Nurture the positive energy. It is important to surround yourself with people with whom you can have productive conversations and a mutual investment in each other’s goals. In addition, building a network of positive relationships – and this requires an investment of time and focus – create a support system for when we are discouraged or confused.

- Take responsibility for your self-care. Looking after one’s mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual health is a priority for everyone and particularly so for leaders because they have many others who depend on them. It is important to find the time to recharge, relax, and open up space for reflective thinking. This can be done through regular exercise, healthy eating, mindfulness practice, and spending time with family and friends.

MADAVI, where I work as an appreciative facilitator, recently conducted a project with the Spanish supermarket chain, Eroski, in which we focus on helping managers and employees discover what they do best in terms of customer service and find ways to improve upon it even more. Just nine months after the initiative got off the ground, Eroski customer satisfaction rose from 68% to 87%.

It’s not magic, it’s science. By cherishing and nurturing the emotions and connections between the people of an organization, leaders can create positive results that make an impact on individuals and on business.

© IE Insights.

Technology’s Role in the ESG Evolution

Not all stakeholders are created equal: a tribute to michael jensen, retaining talent in the age of resignation, eu elections explainer: what are they and why do they matter, would you like to receive ie insights.

Sign up for our Newsletter

RELATED CONTENT

After financial economist Michael Jensen sadly passed away on April 2, 2024, Mikko Ketokivi draws onDr. Jensen’s insights on corporate governance to discuss stakeholder analysis.

Gender Diversity in the Boardroom: A Catalyst for Pay Parity

Quantum Leadership: A Theory in Forward Flux

Vision, Tech, and Learning. The Secret Sauce of AI-Powered Enterprises

Tech Transformation Is Human (Not Digital)

Taking Inclusive Leadership from Buzz to Action

Board as Sovereign Steward not Shareholders’ Agent

The Art of Effective Communication

Latest news, share on mastodon.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 01 March 2023

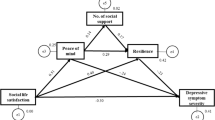

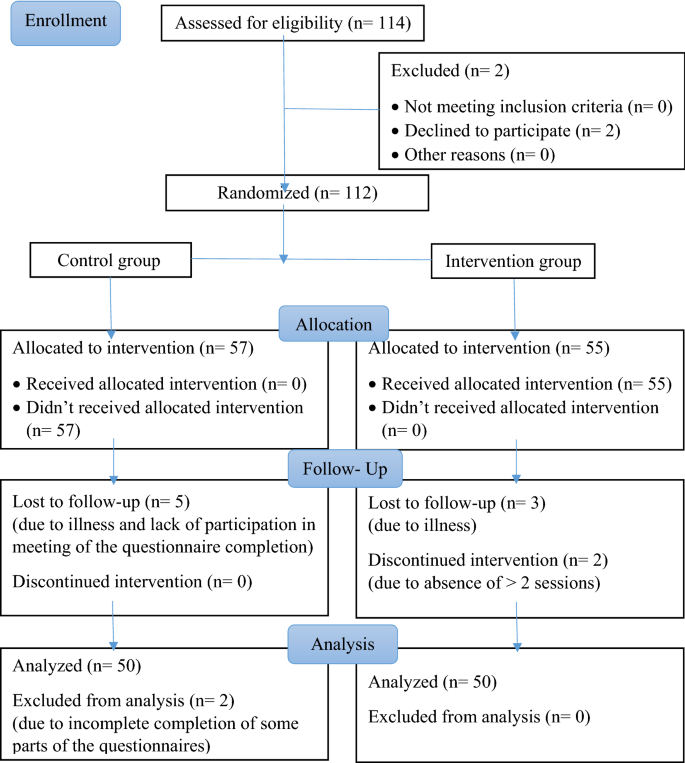

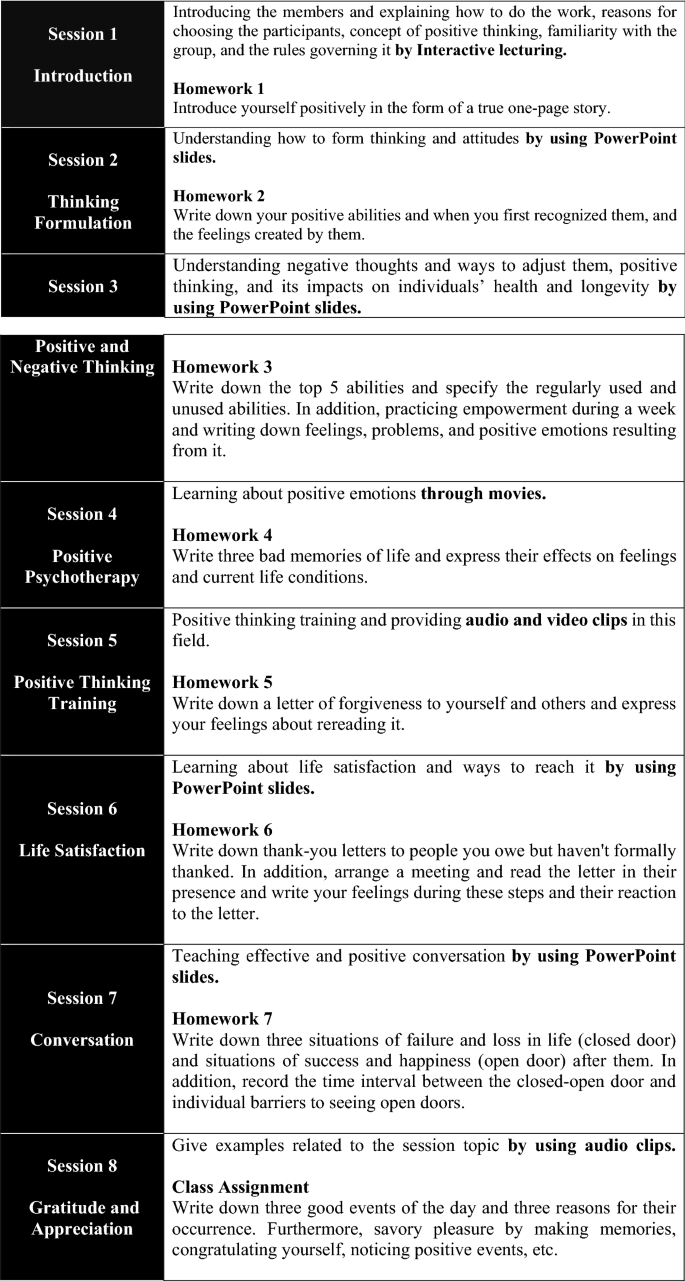

The effect of positive thinking on resilience and life satisfaction of older adults: a randomized controlled trial

- Zahra Taherkhani 1 ,

- Mohammad Hossein Kaveh 2 ,

- Arash Mani 3 ,

- Leila Ghahremani 1 &

- Khadijeh Khademi 4

Scientific Reports volume 13 , Article number: 3478 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

4640 Accesses

4 Citations

223 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care