- All Quiet on the Western Front

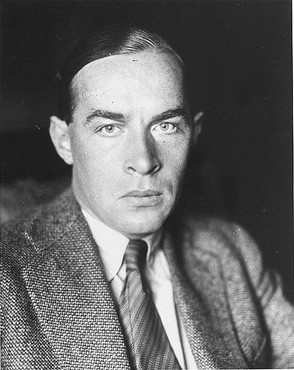

Erich Maria Remarque

- Literature Notes

- Major Themes

- Book Summary

- About All Quiet on the Western Front

- Character List

- Summary and Analysis

- Character Analysis

- Paul Bäumer

- Himmelstoss

- Franz Kemmerich

- Albert Kropp

- Gérard Duval

- Character Map

- Erich Maria Remarque Biography

- Critical Essays

- Rhetorical Devices

- A Note on World War I and Its Technology

- Full Glossary

- Essay Questions

- Practice Projects

- Cite this Literature Note

Critical Essays Major Themes

The Lost Generation

In the autumn of 1918, Paul Bäumer, a 20-year-old German soldier, contemplates his future: "Let the months and years come, they can take nothing from me, they can take nothing anymore. I am so alone and so without hope that I can confront them without fear" (Chapter 12). These final, melancholy thoughts occur just before his young and untimely death. In All Quiet on the Western Front , Erich Maria Remarque creates Paul Bäumer to represent a whole generation of men who are known to history as the "lost generation." Eight million men died in battle, twenty-one million were injured, and over six and a half million noncombatants were killed in what is called "The Great War." When the smoke cleared and the bodies were finally buried, the world asked — like Paul and his friends — why? Remarque writes his story to explain their reason for asking this question and why they felt betrayed by their teachers, families, and government. He creates a tale of inhumanity and unspeakable horror and the only redeeming themes of his book are the recurring ideas of comradeship in the face of death and nature's beauty in the face of bleak hopelessness.

Remarque prefaces his story with his purpose: "I will try simply to tell of a generation of men who, even though they may have escaped shells, were destroyed by the war." Throughout the story, the reader feels that this generation has come through an event that closes forever their chance to go back to the world of their childhood. As early as Chapter 2, Paul Bäumer describes the difference between his generation and that of his parents or even the older soldiers. They had a life before the war, a life where they felt comfortable and secure. But Paul's generation never had a chance at that life. He explains, "Our knowledge of life is limited to death" (Chapter 10). Even when the story begins, all Paul has known is death, horror, fear, suffering, and hopelessness. He and his fellow classmates are only nineteen and twenty years old; even the young recruit who is mortally wounded in Chapter 4 causes Kat to say, "Such a kid. . . .young innocents — ." They feel nothing, believe in nothing, and see no future because of their experiences in the war.

Even if there were a future, in Chapter 5, Paul and his friends occasionally speculate on what it might hold. Paul cannot imagine anything that would have been "worth having lain here in the muck for" and sees everything as "confused and hopeless." His friend Albert, who will end up in a hospital with his leg amputated, feels that the war has ruined them for everything. Another soldier in their group, Kropp, understands that they will not be able to peel away two years of shells and bombs like an old sock When they were eighteen, they were just starting to live life as adults, but that life was cut short by the war and, as Paul says of their world, ". . . we had to shoot it to pieces. The first bomb, the first explosion, burst in our hearts." Will they live to fall in love, to marry, to have children? This is a future they cannot imagine and dare not think about.

Paul goes home on leave and regrets what it does to his heart. As he enters his childhood town, he realizes his life will never be the same. A terrible gulf exists between his present and his past and also between himself and his parents. He sees his past, in Chapter 6, as "a vast inapprehensible melancholy. . . . They [memories] are past, they belong to another world that is gone from us. . . . And even if these scenes of our youth were given back to us we would hardly know what to do. . . . I believe we are lost." At home on leave among his books and childhood papers, he realizes that he can never find his way back to that earlier Paul. Too much has happened at the front for him to believe in human beings or compassion. Even with his parents he realizes that life will never be the same. Paul knows his contemporaries share his feelings near the end of his story when he views the desperate and dying in the hospital: ". . . [a]nd all men of my age, here and over there, throughout the whole world see these things; all my generation is experiencing these things with me."

This lost generation felt a terrible sense of betrayal by their parents, teachers, and government. As they looked around and asked "why," they focused on what they had learned at home and in school. Paul and his friends feel a terrible sense of the absurd when they see how important protocol seems to be to the older generation. The Kaiser visits and all is polished until he leaves; then the new uniforms are given back and the rags of uniforms reappear. The patriotic myths of the older generation become apparent when Paul goes home. A sergeant-major chastises Paul for not saluting him when Paul has spent a good share of his life in the trenches killing the enemy and trying to survive. These examples of betrayal appear again and again in Remarque's novel.

Parents also carry the heavy burden of the lost generation's accusation. Paul says that German parents are always ready with the word "coward" for a young person who will not join up. He feels that parents should have been mediators and guides for Paul's friends, but they let them down. No longer can they trust their parents' generation. He speaks of the wise but poor people in relation to their parents: "The wisest were just the poor and simple people. They knew the war to be a misfortune, whereas those who were better off, and should have been able to see more clearly what the consequences would be, were beside themselves with joy." He sees this already in Chapter 1 and realizes that his generation is terribly alone and does not share its parent's traditional values.

Teachers are also to blame. Going home, Paul hears the head-master spew empty patriotic rhetoric and argue that he knows better than Paul what is happening in the war. Paul blames his old schoolteacher Kantorek for Joseph Behm's death, because Kantorek goaded the hapless Behm to join up. And Paul knows there are Kantoreks all over Germany lecturing their students to patriotic fervor. Even Leer, who was so good at mathematics in school, dies of a terrible wound and Paul wonders what good his school-learned mathematics will do him now. Paul's entire generation has a terrible feeling of betrayal when they consider military protocol, their parents, and their school teachers.

Old men start the war and young men die. Whether it be this war or any war since, the agony of the fighters is echoed in Paul's words in Chapter 10, as he gazes around the hospital:

And this is only one hospital, one single station; there are hundreds of thousands in Germany, hundreds of thousands in France, hundreds of thousands in Russia. How senseless is everything that can ever be written, or done, or thought, when such things are possible. It must be all lies and of no account when the culture of a thousand years could not prevent this stream of blood being poured out, these torture-chambers in their hundreds of thousands. A hospital alone shows what war is.

Man's Inhumanity to Man

Paul and his friends become so inured to death and horror all around them that the inhumanity and atrocities of war become part of everyday life. Here is where Remarque is at his greatest: in his description of the true horror and paralyzing fear at the front. He describes the atrocities, the terrible consequences of weapons of mass destruction, and how soldiers become hardened to death and its onslaught of sensory perceptions during battle.

Atrocities are simply a part of the inhumane business of war. In Chapter 6, Paul and his men come across soldiers whose noses are cut off and eyes poked out with their own saw bayonets. Their mouths and noses are stuffed with sawdust so they suffocate. This constant view of death causes the soldiers to fight back like insensible animals. They use spades to cleave faces in two and jab bayonets into the backs of any enemy who is too slow to get away. Their callousness is contrasted with the reaction of the new recruits who sob, tremble, and give in to front-line madness described over and over again in scenes of the front.

Remarque vividly recounts the horror of constant death as Paul comes upon scenes of destruction. In Chapter 6, he sees a Frenchman who dies under German fire. The man's body collapses, hands suspended, and then his body drops away with only the stumps of arms and hands hanging in the wire and the rest of his body on the ground. They later come upon a scene with dead bodies whose bellies are swollen like balloons. "They hiss, belch, and make movements. The gases in them make noises." The smell of blood and putrefaction is overwhelming and causes many of Paul's company to be nauseated and retch. The assault on the senses is overwhelming. They later pile the dead in a shell hole with "three layers so far." This horrifying picture is grimly elaborated on in Chapter 9 when they pass through a forest where there are bodies of victims of trench mortars. It is a "forest of the dead." Parts of naked bodies are hanging in trees, and Paul brutally describes pieces of arms here and half of a naked body there.

By the time Remarque reaches Chapter 11, he has described the soldier's life as one long, endless chain of the following:

Shells, gas clouds, and flotillas of tanks — shattering, corroding, death. Dysentery, influenza, typhus — scalding, choking death. Trenches, hospitals, the common grave — there are no other possibilities.

Comradeship

Throughout all the horrifying pictures of death and inhumanity, Remarque does scatter a redeeming quality: comradeship. When Paul and his friends waylay Himmelstoss and beat on him, we laugh because he deserves it and they are only giving him his due. As time goes by, however, the pictures of camaraderie relieve the terrible descriptions of front line assaults and death, and they provide a bright light in a place of such terrible darkness. A young recruit becomes gun-shy in his first battle when a rocket fires and explosions begin. He creeps over to Paul and buries his head in Paul's chest and arms, and Paul kindly, gently, tells him that he will get used to it (Chapter 4).

Perhaps the two most amazing scenes of humanity and caring can be found in the story of the goose roasting and the battle where his comrades' voices cause Paul to regain his nerve. In Chapter 5, Paul and Kat have captured a goose and are roasting it late at night. Paul says, "We don't talk much, but I believe we have a more complete communion with one another than even lovers have. We are two men, two minute sparks of life; outside is the night and the circle of death." As he watches Kat roasting the goose and hears his voice, it brings Paul peace and reassurance. Over and over again, in scenes of battle and scenes of rest, we see the comradeship of this tiny group of men. Even though Paul counts their losses at various points, he always considers their close relationship and attempts to keep them together to help each other. In Chapter 9, when Paul is alone in the trench, he loses his nerve and his direction and is afraid he will die. Instead, he hears the voices of his friends: "I belong to them and they to me; we all share the same fear and the same life; we are nearer than lovers, in a simpler, a harder way; I could bury my face in them in these voices, these words that have saved me and will stand by me." There is a grace here, in the face of all sorrow and hopelessness, a grace that occurs when men realize their humanity and their reliance on others.

Through thick and thin, battle and rest, horror and hopelessness, these men hold each other up. Finally, Paul has only Kat and he loses even this friend and father-figure in Chapter 11. Kat's death is so overwhelming and so final that we do not hear Paul's reaction; we only see him break down in the face of it. There is such final irony in the medic's question about whether they are related. This man, this hero, this father, this life — has been closer to Paul than his own blood relatives and yet Paul must say, "No, we are not related." It is the final stunning blow before Paul must go on alone.

Throughout his novel, Remarque uses nature in several ways. It revitalizes the soldiers after terrible hardships, reflects their sadness, and provides a contrast to the unnatural world of war. When Kemmerich, the first of Paul's classmates dies, Paul takes his identification tags and walks outside. "I breathe as deep as I can, and feel the breeze in my face, warm and soft as never before." Many times throughout the novel Remarque uses nature in this way to restore men and help them go on.

Nature also reflects the terrible sadness of the lost generation. In Chapter 4, Paul's company sustains heavy losses and a recruit is wounded so badly Paul and Kat consider killing him to end his suffering. The lorries and medics arrive too quickly, and they are forced to rethink their decision. Paul watches the rain fall and says: "It falls on our heads and on the heads of the dead, up in the line, on the body of the little recruit with the wound that is so much too big for his hip; it falls on Kemmerich's grave; it falls in our hearts." The cleansing rain falls upon the hopelessness of Paul's life and the lives of those around him. Throughout Remarque's book, we also see a strong affinity between nature and lost dreams and memories. When Paul is on sentry duty in Chapter 6, he remembers his childhood and thinks about the poplar avenue where such a long time ago they sat beneath the trees and put their feet in the stream. Back then the water was fragrant, the wind melodious; these memories of nature cause a powerful calmness and awaken a remembrance of what was — but sadly, will never be again.

Finally, butterflies play gracefully and settle on the teeth of a skull; birds fly through the air in a carefree pattern. This is nature in the midst of death and destruction. While men kill each other and wonder why, the butterflies, birds, and breeze flutter though the killing fields and carry on as if mankind were quite insignificant. Even at the end when Paul knows there is so little time until the armistice, he reflects on the beauty of life and hopes that he can stay alive until the laws of nature once again prevail and the actions of men bring peace. He describes the red poppies, meadows, beetles, grass, trees at twilight, and the stars. How can such beauty go on in the midst of such heartache?

Remarque says that this novel "will try simply to tell of a generation of men who, even though they may have escaped shells, were destroyed by the war." If words can touch what men hold to be dear in their hearts and so cause them to change the world, this book with its words of a lost generation, lost values, and lost humanity is surely one that should be required reading for all generations.

Previous Erich Maria Remarque Biography

All Quiet on the Western Front

by Erich Remarque

All quiet on the western front themes, brutality of war.

Remarque writes in the epigraph that his book will describe the men who were "destroyed by the war," and after that All Quiet on the Western Front is a nearly ceaseless exploration of the destructive properties of The Great War. Included are two detailed chapters about fighting at the front and in the trenches (Chapters Four and Six). Remarque smashes whatever romantic preconceptions the reader may have about combat in his descriptions of rat-infestation, starvation, nerve attacks, shell-shock, and inclement weather--to say nothing for actual combat and the deadly zone of no-man's-land between enemy trenches.

The reader is also introduced to all the new forms of assault World War I developed--tanks, airplanes, machine guns, more accurate artillery bombardment, and poisonous gas. The consequences of war are given due consideration--Paul watches friends die, sees dislocated body parts, and tours a hospital of the wounded. Each time Paul counts the thinning ranks of his company, we are reminded that all the fighting is only over a small piece of land--a few hundred yards or less--and that, very soon, the fighting will renew over whatever was gained or lost.

The young soldier's alienation

To add to the discussion of war's destructive properties (see Brutality of war, above), Remarque comments in the epigraph that his novel is primarily for "a generation of men who, even though they may have escaped the shells, were destroyed by the war." This generation is Germany's youth, pushed into the war by their nationalistic elders for a cause they have little stake in, and transformed into desensitized zombies by a war too brutal to endure. Paul's flat tone throughout the novel emphasizes this numbness: he often passes off a friend's death as if it is a common occurrence--which it is. If the soldier allowed himself to feel emotions, he would die far sooner, or go mad. Accordingly, the soldiers either make light of war--they bet over an airplane dogfight, for instance--or become pragmatic rather than sentimental (the fight over Kemmerich's boots, for instance). Paul vows to repress his feelings until after the war, but even he cannot deny the profound pain he endures.

Paul's disconnection emerges again when he visits home. He does not allow himself to bond with his dying mother, and regrets having come home and opened emotional wounds. He has further trouble connecting with the rest of his family and other civilians, none of whom he feels understands his plight, and it is clear his alienation also springs from his disconnection with the past. Like most of the young soldiers who joined the war after they graduated from school, he can barely remember what his life was like before he joined the military, and what he can remember now seems useless to him. Moreover, he cannot imagine any future after the military; the adjustment to civilian life and an occupation seems impossible. The young soldiers are caught in a nihilistic no-man's-land between the irretrievable past and an unfathomable future.

Paul's generation feels betrayed by its nationalistic elders like Kantorek , and by those who glorify war, such as the French brunette who is interested in Paul only as a romanticized soldier on the brink of death. The only thing reducing the soldiers' alienation is their intimate bond with each other (see Unity among soldiers).

Nationalism

Nationalism is the unswerving dedication to one's homeland, and it swept Europe in the years leading up to WWI. Kantorek, the boys' former schoolteacher, epitomizes nationalism; Paul describes how Kantorek rallied his pupils with patriotic speeches and bullied them into volunteering for the war, ridiculing them for cowardice if they stayed at home. However, Kantorek and his generation are not the ones dying in the war. It is the "'Iron Youth,'" as he calls them, who give up their lives for the political power games of a few global leaders.

Paul is bitter about the nationalism that has forced him and countless others to enter the war, but he manages to use it for humane purposes. He unites with the Russian prisoners through a universal language, music, knowing that arbitrary political powers have made them enemies. He also empathizes deeply with the Frenchman he kills, seeing past the man's nationality and into his life (he discovers his name, occupation, and family situation). In fact, Paul kills the Frenchman in the no-man's-land between enemy trenches, the only remaining place in Europe not owned by a particular country (although, of course, bitter fights take place over its ownership).

Unity among soldiers

The first word of the novel is "We," and Paul's typically first-person singular narration ("I") frequently slips into the first-person plural voice. The one good thing that has emerged from the war, he often contends, is the comradeship between the soldiers. Disciplinarian training intent on breaking down the soldiers' individuality, and the horrors of war, bond the men in ways civilians cannot comprehend. They do everything together, from eating to using the latrines; even dead bodies in battle are used as cover for the living. Sexuality plays an important role in their all-male camaraderie; they go on amorous adventures for women (the Frenchwomen episode) or help others have sex (as when they arrange the conjugal visit for Lewandowski in the hospital). Their intimacy is also tinged with homoeroticism (Paul's fondness for Kat as they cook a goose together goes beyond mere friendship).

The soldiers are frequently compared to animals. They eat mass-prepared food together as if out of troughs and use the outdoor latrines together. Kat theorizes that the battle for power within the military is like that of the animal kingdom, and Himmelstoss's hunger for alpha-male power reinforces this claim (as does the soldiers' vicious ambush of him). The soldiers are also de-individualized during battle, losing their humanity. Almost as a response, animals play a more important role at these times; horses are used and wounded in battle, rats infest the trenches, and geese pop up at several times.

Words, words, words

In Chapter Six, Paul laments that words cannot do the war justice; in Chapter Seven, he believes they may do it too much justice, making it too real and unbearable. He echoes Hamlet's famous line "Words, words, words"; like Hamlet, Paul is absorbed in his own verbal thoughts, unable to escape from them. Remarque possibly wrote his novel to master and define the emotions of war; perhaps he is the third-person narrator at the end who describes Paul's death.

All Quiet on the Western Front Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for All Quiet on the Western Front is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Provide reasons that Paul compares war to cancer and tuberculosis, influenza and dysentery.

Paul likens war to cancer, tuberculosis,influenza and dysentery because they all cause death. He sees the death in war as if it's a terrible disease.

We have almost grown accustomed to it; war is a cause of death like cancer and...

Kemmerich's boots hold a great deal of symbolism. Boots are in high demand: a symbol of how poorly the German army is outfitted by the country. Boots get passed around from soldier to soldier after one dies: another symbol of frequent mortality in...

What does Paul’s sympathy and concern for the dying enemy soldier demonstrate?

Do you mean the French soldier he kills in the trench? Paul finds that he has more in common with him than the politicians who have sent him into war. Paul shows great empathy for him. He wants to help the French soldier's family after the war.

Study Guide for All Quiet on the Western Front

All Quiet on the Western Front study guide contains a biography of Erich Remarque, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About All Quiet on the Western Front

- All Quiet on the Western Front Summary

- Character List

- Epitaph - Chapter 3 Summary and Analysis

Essays for All Quiet on the Western Front

All Quiet on the Western Front literature essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of All Quiet on the Western Front.

- The Glory of War is the Realization That There is No Glory

- The Lost Generation

- Ordinary Men and Women: What We Can Learn from Non-Traditional Sources

- Dehumanisation, Death, Destruction

- A Universal Loss of Innocence: Remarque’s “All Quiet on the Western Front”

Lesson Plan for All Quiet on the Western Front

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to All Quiet on the Western Front

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- All Quiet on the Western Front Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for All Quiet on the Western Front

- Introduction

- Title and translation

- Plot summary

Loss of Innocence in “All Quiet on the Western Front”

This essay will delve into the theme of lost innocence in Erich Maria Remarque’s novel “All Quiet on the Western Front,” exploring how the brutality of war shatters the youth and ideals of its protagonists. Also at PapersOwl you can find more free essay examples related to All Quiet On The Western Front.

How it works

In the book All Quiet On The Western Front, Remarque uses the loss of innocence of his characters to show that war breaks and even destroys people. Also Remarque’s ground breaking book presents a powerful literary critique of WWI by smashing any ideas about war is heroic and meaningful. Due to the war in All Quiet On The Western Front, the soldiers’ perspective of life becomes nothing but death and misery; it results in the soldiers knowing too much about the dark part of life.

At the beginning of the book, the soldiers have not lost their innocence because of the cruelty of war. “Yesterday we were relieved, and now our bellies are full of beef and haricot beans. We are satisfied and at peace. Each man has another mess-tin full for the evening; and, what is more, there is a double ration of sausage and bread. That puts a man in fine trim” (Remarque 1). This is an innocent way the soldiers live. This quote shows how fully they take pleasure in something as simple as food. The brutal war has not destroyed their innocence, they are so naive. They are carefree, and live in a peaceful natural environment, not realizing the horrible battle is coming.

“These are wonderfully care-free hours. Over us is the blue sky. On the horizon float the bright yellow sunlit observation-balloons, and the many little white clouds of the anti-aircraft shells. Often they rise in a sheaf as they follow after an airman. We hear the muffled rumble of the front only as very distant thunder, bumblebees droning by quite drown it” (Remarque 9). In this moment, the soldiers find themselves in a protected paradise. Remarque uses words like “care-free”, “float”, and “soft” to create a warm, cheerful and inviting mood. Also he creates a dangerous atmosphere when he uses words like “”little white clouds”” to describe the bombs detonating in the distance. In this moment it shows that they can’t get away from the life surrounded by war. The cruelty of war will swallow up their innocence very soon.

When the war begins it devours their innocence as fast as it can. They are getting older both physically and mentally and they are no longer young. As Kantorek says, “Yes, that’s the way they think, these hundred thousand Kantoreks! Iron Youth! Youth! We are none of us more than twenty years old. But young? Youth? That is long ago. We are old folk” (Remarque 18). The war not only took the lives of millions of people, but also caused great harm to people’s mind and body. They are much older and run down by the cruelties of the war.

Also the war makes them disoriented and nervous. Sleep is the only thing they can do. “I don’t know whether it’s morning or evening. I lie in the pale cradle of the twilight, and listen for the soft words which will come, soft and near – am I crying? I put my hand to my eyes, it is so fantastic; am I a child?” (Remarque 60). Sleep is the only thing to let them forget where they are. This quote shows Paul’s realization of the horrors of war. This is a heartbreaking moment and it’s the first time Paul is exposed to such a situation. The war is very terrible; everybody hears it in the background with fear. And it brings us untold miseries and damage.

The war has changed the men’s lives forever and changes the very soul of a person as well as their outlook on life. “We were eighteen and had begun to love life and the world; and we had to shoot it to pieces. The first bomb, the first explosion, burst in our hearts” (Remarque 88). When these men were young, learning to love and live, they went into war and destroyed their lives. The only thing they really know how to do is fight in a war. They are always going to remember the first time they had to fight. All of these memories soon became part of their perspective of the “”normal life.”” The cruelty of war has made a great impact on people’s lives and minds and bodies.

They feel scared and desperate. “I am young, I am twenty years old; yet I know nothing of life but despair, death, fear, and fatuous superficiality cast over an abyss of sorrow. I see how people are set against one another, and in silence, unknowingly, foolishly, obediently, innocently, slay one another” (Remarque 263). The war changes the very soul of a person as well as their outlook on life.They lose in this war; they don’t know what to expect once the war ends. The war led them to lose their innocence and let them drop off into a dark war that they never return from.

WWI left Europe and the world feeling like it just brings suffering and misery. Because of war people are forced to leave their hometowns, lose their loved ones, and live in fear every day; even in today’s more peaceful society, there are still wars happening right now. War cause great disaster and misery to countries, societies and people.

Cite this page

Loss of Innocence in "All Quiet On The Western Front". (2020, May 16). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/loss-of-innocence-in-all-quiet-on-the-western-front/

"Loss of Innocence in "All Quiet On The Western Front"." PapersOwl.com , 16 May 2020, https://papersowl.com/examples/loss-of-innocence-in-all-quiet-on-the-western-front/

PapersOwl.com. (2020). Loss of Innocence in "All Quiet On The Western Front" . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/loss-of-innocence-in-all-quiet-on-the-western-front/ [Accessed: 26 Apr. 2024]

"Loss of Innocence in "All Quiet On The Western Front"." PapersOwl.com, May 16, 2020. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/loss-of-innocence-in-all-quiet-on-the-western-front/

"Loss of Innocence in "All Quiet On The Western Front"," PapersOwl.com , 16-May-2020. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/loss-of-innocence-in-all-quiet-on-the-western-front/. [Accessed: 26-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2020). Loss of Innocence in "All Quiet On The Western Front" . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/loss-of-innocence-in-all-quiet-on-the-western-front/ [Accessed: 26-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português do Brasil

Featured Content

Find topics of interest and explore encyclopedia content related to those topics

Find articles, photos, maps, films, and more listed alphabetically

For Teachers

Recommended resources and topics if you have limited time to teach about the Holocaust

Explore the ID Cards to learn more about personal experiences during the Holocaust

Timeline of Events

Explore a timeline of events that occurred before, during, and after the Holocaust.

- Introduction to the Holocaust

- Liberation of Nazi Camps

- Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

- Boycott of Jewish Businesses

- Axis Invasion of Yugoslavia

- Antisemitism

- How Many People did the Nazis Murder?

- The Rwanda Genocide

Erich Maria Remarque: In Depth

In 1933, Nazi students at more than 30 German universities pillaged libraries in search of books they considered to be "un-German." Among the literary and political writings they threw into the flames were the works of Erich Maria Remarque.

- book burning

Erich Maria Remarque was born Erich Paul Remark on June 22, 1898 in Osnabrück, Germany. He received an education in private Catholic schools and subsequently enrolled in a training school for teachers, which he attended until he was conscripted into the German army. At this time, he also began writing fiction.

World War I

World War I played a crucial role in Remarque's evolution as a writer. In November 1916, Remarque, along with a number of his classmates, was drafted into the German army. After a period of military training, his unit was sent to the Western Front. There he took part in the trench warfare in Flanders, Belgium. In July 1917, he was wounded by shell fragments during a heavy British artillery attack. After a lengthy convalescence he was recalled to active military service in October 1918. Shortly thereafter, Germany's imperial government was toppled in a revolution, and the country became a republic. On November 11, 1918, the new government signed the armistice with the Allies, which ended the fighting. Remarque's wartime experiences, including the loss of some of his comrades, made a strong impression on the young man and served as inspiration for All Quiet on the Western Front .

He returned to Osnabrück, where he finished his educational training. He subsequently took up teaching, but his career was short-lived, He quit this profession in 1920. To make ends meet, he gave piano lessons, served as an organist, and wrote theater reviews for a local newspaper. During this time, he published his first novel, Die Traumbude ( The Dream Booth ) as well as some poetry and other fiction. In 1922, he moved to Hannover, where he took a position as a writer and editor for Echo Continental , a magazine owned by the Continental Rubber Company, a leading manufacturer of automobile tires. Here he wrote advertising copy, crafted slogans, and published articles on travel, cars, and outdoor life. He also adopted the name Erich Maria Remarque, using the original French spelling of his family's name.

In 1925, he relocated to Berlin, where he served as an editor for the popular sports illustrated magazine, Sport im Bild. In the German capital, he mingled with leading writers and film makers, including Leni Riefenstahl, who later created Triumph of the Will and other films in Nazi Germany.

All Quiet on the Western Front

In 1929, Remarque scored his greatest, and most lasting, success with the novel, All Quiet on the Western Front ( Im Westen nichts Neues ). The work graphically depicted the horrors and brutality of World War I (1914-1918) through the tragic experiences of a group of young German soldiers. The novel, a lasting tribute to the “lost generation” that perished in the Great War, became an immediate international bestseller. In Germany alone in 1929, the book sold almost one million copies. It was translated into more than a dozen languages, including English, French, and Chinese. All Quiet on the Western Front earned Remarque accolades generally from the liberal and leftist press for the work's pacifist stance. The Nazis and conservative nationalists immediately denounced it as an assault on Germany's honor, as a piece of Marxist propaganda, and the work of a traitor.

That same year, German-born Hollywood producer Carl Laemmle, acquired the rights to make a film of the book. In May 1930, the American film premiered in Los Angeles and won Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Director. That summer, audiences in France, Britain, and Belgium flocked to the film and it received popular acclaim.

Almost immediately the American film ran into trouble in Germany. When it was proposed for showing, a representative of the German Ministry of Defense urged that its screening be rejected on the grounds that it damaged the country's image and shed bad light on the German military. In response, the Berlin censorship office urged Laemmle to make cuts to the film, which were done. Remarque's former boss, the press and film magnate, and outspoken German nationalist, Alfred Hugenberg, indicated that because of the movie's alleged anti-German bias it would not be shown in any of his theaters. He subsequently petitioned German president, Paul von Hindenburg, to ban the film.

In December 1930, when the edited and dubbed version of the film was shown to the general public in Berlin, the Nazis sabotaged the event. The Party's leader in Berlin and its propaganda chief, Joseph Goebbels, organized a riot to disrupt the showing. Outside, SA storm troopers intimidated movie goers, while inside they released stink bombs and mice and harangued the audience. At subsequent showings, the Nazis carried out violent protests. In response to these actions and conservative attacks on the film, the government banned the film. Liberals and socialists condemned the action, but the prohibition lasted until September 1931, when Laemmle produced a more censored version for German audiences.

Book Burning and Beyond

In 1933, Remarque was forced by the rising tide of Nazism to flee his native Germany for the relative calm and security of Switzerland, where several years earlier he had purchased a lakeshore villa. Seeing the writing on the wall, he left Berlin just one day before Adolf Hitler was appointed German chancellor on January 30, 1933.

Several months later, in May 1933, pro-Nazi students consigned his works to the flames during the fiery book burning spectacles staged throughout the country. In Berlin , as the students assembled on the Opernplatz opposite the university with piles of books for the pyres, the Nazi speaker denounced various authors for their un-German spirit, concluding with the following comments:

“Against literary betrayal of the soldiers of the World War, for the education of the people in the spirit of truthfulness! I surrender to the flames the writings of Erich Maria Remarque.”

Subsequently, German police purged his works from bookstores, libraries, and universities. In 1938, the Nazi government stripped him of his German citizenship. From 1933 onward, Remarque spent his remaining days outside of Germany, except for occasional trips made after the Nazi defeat in 1945.

Though he lost much of his German-speaking audience when the Nazis banned his books, his novels, in translation, continued to find new readers in the United States and elsewhere. In contrast to many of his fellow German exiled writers, Remarque did not suffer a significant loss of fame or fortune when he left Germany. Major publishers still printed his work, magazines, like Collier's serialized his new fiction, and Hollywood filmed a many of his novels.

World War II

In September 1939, Remarque left Europe for the United States, just as World War II was beginning. Dividing his time between New York and Los Angeles, he continued to write popular novels, which echoed, in part, the experiences of refugees forced to flee Nazi rule. Much of his post1933 fiction, such as Liebe deinen Nächsten ( Flotsam ), Arc de Triomphe ( Arch of Triumph ), Die Nacht von Lissabon ( The Night in Lisbon ), and the posthumous, Schatten im Paradies ( Shadows in Paradise ), depicts the lives and suffering of anti-Nazi emigres, their often ambivalent feelings towards Germany, and their sometimes difficult adjustments to life in exile.

In 1944, Remarque wrote a report for America's Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the country's foreign intelligence organization and the forerunner to today's Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In it, he urged the Allies to adopt a systematic policy for re-educating the German population after the war. Germans, he believed, had to be exposed to Nazi crimes and evils of militarism.

After the War

In his postwar novels, Remarque attempted to continue to expose Nazi crimes. As such, he was among the first and most prominent German writers to address Nazi mass murder , the concentration camp system , and the issue of the population's culpability in these crimes, in such works as Der Funke Leben ( Spark of Life ) and Zeit zu leben und Zeit zu sterben (published in English as A Time to Love and A Time to Die ).

After the war, he also learned that his younger sister, Elfriede, had been arrested and tried before the Nazi People's Court for making anti-Nazi and “defeatist” remarks. Convicted, she was sentenced to death and beheaded on December 16, 1943. He dedicated Der Funke Leben ( Spark of Life ) to her memory. In an attempt to bring those who denounced her to justice, he hired Robert Kempner, one of the US prosecutors at the Nuremberg Trials of Nazi war criminals, to investigate this matter.

In 1948, Remarque returned to Switzerland as an American citizen. His works were once again published in Germany, although they frequently received negative criticism and were revised to edit out politically “unpalatable” passages. In 1958, he married American film star Paulette Goddard, with whom he remained until his death in 1970.

Published Works

1920 Die Traumbude

1929 Im Westen Nichts Neues ( All Quiet on the Western Front )

1931 Der Weg Züruck ( The Road Back )

1938 Drei Kameraden ( Three Comrades )

1941 Liebe deinen Nächsten, (Love Thy Neighbor), published in English as Flotsam

1945 Arc de Triomphe ( Arch of Triumph )

1952 Der Funke Leben ( Spark of Life )

1954 Zeit zu leben und Zeit zu sterben (A Time to Live and A Time to Die), published in English as A Time to Love and A Time to Die

1956 Der schwarze Obelisk ( The Black Obelisk )

1961 Der Himmel kennt keine Günstlinge ( Heaven has no Favorites )

1962 Die Nacht von Lissabon ( The Night in Lisbon )

1971 Schatten im Paradies ( Shadows in Paradise )

Critical Thinking Questions

- Investigate German society’s view of World War I in the 1920s.

- If Jews were the principal target during the Holocaust, why were books written by non-Jewish authors burned?

- How did the German public react to the book burnings? What was reaction like outside of Germany?

- Why do oppressive regimes promote or support censorship and book burning? Why might this be a warning sign for mass atrocity?

Further Reading

Baker, Christine R. and Last, R. W., Erich Maria Remarque. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1979.

Cernyak-Spatz, Susan E., German Holocaust Literature . New York: Peter Lang, 1989.

Eksteins, Modris, “War, Memory, and Politics: The Fate of the Film All Quiet on the Western Front. ” Central European History, vol. XIII, number 1 (March 1980), 60-82.

Gilbert, Julie, Opposite Attraction: the Lives of Erich Maria Remarque and Paulette Goddard. New York: Pantheon Books, 1995.

Glunz, Claudia and Schneider, Thomas F., eds. Elfriede Scholz, geb. Remark: Im Namen des Deutschen Volkes; Dokumente einer justitiellen Ermordung. Osnabrück: Universitätsverlag, 1997.

Gooch III, Herbert E.,“Isolationism in All Quiet on the Western Front .” In Reelpolitik: Political Ideologies in '30s and '40s Films . Beverly Merrill Kelley with John J. Pitney, Jr., Craig R. Smith, and Herbert E. Gooch III. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998, 95-113.

Kamla, Thomas A., “The German Exile Novel During the Third Reich: The Problem of Art and Politics,” German Studies Review , vol. III, number 3, (October 1980), 395-413.

Owen, C. R., Erich Maria Remarque: a critical bio-bibliography

Schneider, Thomas F., and Westphalen, “Reue ist undeutsch” Erich Maria Remarques Der Funke Leben und das Konzentrationslager Buchenwald. Katalog zur Ausstellung. Bramsche: Rasch, 1992.

Schwarz, Wilhelm Johannes, War and Mind of Germany . Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1975.

Taylor, Jr., Harley U., Erich Maria Remarque: a literary and film biography. New York: Peter Lang, 1989.

Tims, Hilton, Erich Maria Remarque: The Last Romantic. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003..

Wagener, Hans, “Erich Maria Remarque.” In Deutsche Exilliteratur Seit 1933 , vol. 1: California, edited by John M. Spalek and Joseph Strelka. Bern and Munich: Francke Verlag, 1976. 591-605.

Wagener, Hans,, Understanding Erich Maria Remarque. Columbia: The University of South Carolina Press, 1991.

Thank you for supporting our work

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies and the Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

Jump to navigation

All Quiet on the Western Front

by Patrick Clardy

All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque was first published in German as Im Westen Nichts Neues in 1928 . It is one of the most widely read and well known novels to emerge from the First World War and has elicited both strong support and strong criticism for its portrayal of the experiences of that war's common soldier. To this day, the novel continues to be part of curriculums at all levels in both Germany and the United States.

All Quiet on the Western Front describes the experiences of Paul Bäumer, a soldier in the German army of World War I. The novel opens with Paul already on the front lines. It includes the back story of how Paul and his classmates were persuaded to volunteer by their high school teacher, Kantorek. They went through basic training, which they hated, under the despicable Sergeant Himmelstoss. Many of Paul's classmates die or are injured shortly after reaching the front, notably Franz Kemmerich.

Paul’s comrades also include the non-students Tjaden, Haie Westhus, Detering, and Kat, who all die in the course of the novel. The story concludes with Paul’s own death at the hands of a French sniper on a day near the end of the war. The official report on the day was “All quiet on the Western Front”.

The novel switches quickly between various scenes of life on the front lines, including routine shellings, attacks and counter attacks, gas attacks, being pulled back from the front, camp life, eating, recreation, and the general day-to-day experience of life in the trenches.

One key episode describes Paul’s experience in the military hospital while recovering from wounds. During this time he has time to think and reflect on the war and its effects. Another crucial scene shows Paul going home on leave. The people at home have a conception of the war that differs from the experience at the front.

At another point, Paul guards a group of Russian prisoners. Another time he is stuck for an entire night in no-man’s land in a foxhole with a French soldier who he has stabbed and killed. These two experiences impress on Paul the similarity between the soldiers on the two sides, how they are only enemies as a matter of chance and because of orders from above.

Paul is the last of his friends to die. Paul is thus left alone and ponders the random nature of war and the helpless position of the individual soldier constantly faced with death. His recognition of his instinctive drive to survive, despite the fact that he cannot think of what he is surviving for, puts him eerily at peace, just before he himself is killed.

Remarque was born into a lower middle class Catholic family in Osnabrück. He was in the midst of training to become a teacher when he was drafted into the army in November, 1916 . He was put through boot camp near Osnabrück and in Saxony and then sent to Flanders. There he served as a sapper, building trenches, until he was wounded by shrapnel in July of 1917 .

Remarque spent the next fifteen months in a hospital in Duisberg. He was released in October of 1918 , but was never actually sent back to the front, because the war ended on November 11. [1] He wrote All Quiet on the Western Front in 1928, mainly as an attempt to combat his post-war depression (Wagner, 9).

While some of Paul’s personal life--his butterfly collecting, his sickly mother and stern father, as well as some war experiences--are based off Remarque’s own life, All Quiet on the Western Front is not a biographical novel. While exposed to various war experiences, Remarque never actually engaged in combat himself; he was only shot at. Paul’s personal experiences are a composite of Remarque’s own experiences and those of other soldiers that he witnessed second hand or heard while recovering in hospital (Wagner, 12).

Although All Quiet on the Western Front was and remains hugely popular in terms of sales, it received highly mixed reviews from critics. It was banned and burned by the Nazis, who were against anything that might call into question their conception of the German soldier as the embodiment of national glory, bravery, and love of the fatherland. The book was later banned and burned and condemned as “the literary betrayal of the soldiers of the Great War." [2]

However, objections to Remarque’s portrayal of the German army personnel during World War I were not limited to the Nazis. Dr. Karl Kroner objected to Remarque’s depiction of the medical personnel as being inattentive, uncaring, or absent from frontline action (Barker and Last, 36). Dr. Kroner was specifically worried that the book would perpetuate German stereotypes abroad that had subsided since the First World War. He offered the following clarification: “People abroad will draw the following conclusions: if German doctors deal with their own fellow countrymen in this manner, what acts of inhumanity will they not perpetuate against helpless prisoners delivered up into their hands or against the populations of occupied territory?” (Barker and Last, 37). The horrifying answer to this question would come within decades.

A fellow patient of Remarque’s in the military hospital in Duisberg objected to the negative depictions of the nuns and patients, and of the general portrayal of soldiers: “There were soldiers to whom the protection of homeland, protection of house and homestead, protection of family were the highest objective, and to whom this will to protect their homeland gave the strength to endure any extremities” (Barker and Last, 37-38).

These criticisms suggest that perhaps experiences of the war and the personal reactions of individual soldiers to their experiences may be more diverse than Remarque portrays them; however, it is beyond question that Remarque gives voice to a side of the war and its experience that was overlooked or suppressed at the time. This perspective is crucial to understanding the true effects of World War I. The evidence can be seen in the lingering depression that Remarque and many of his friends and acquaintances were suffering a decade later.

In contrast, All Quiet on the Western Front was trumpeted by pacifists as an anti-war book (Barker and Last, 38). Remarque makes a point in the opening statement that the novel does not advocate any political position, but is merely an attempt to describe the experiences of the soldier (Wagner, 11).

The main artistic criticism was that it was a mediocre attempt to cash in on public sentiment. The enormous popularity the work received was a point of contention for some literary critics, who scoffed at the fact that such a simple work could be so earth-shattering. Much of this literary criticism came from Dr. Salomo Friedländer, who wrote a parody Vor Troja Nichts Neues . Friedländer’s criticism's were mainly personal in nature--he attacked Remarque as being ego-centric and greedy (Barker and Last, 41-3).

These criticisms, however, ignore the fact thatRemarque is not simply relating his own experiences to anyone who will listen. He is trying to create a broader picture of the experience of the typical soldier. This is achieved not only through Paul, the main character, but through the other characters as well, who together represent the patchwork of people that made up the rank and file of the German army during World War I. Remarque publicly stated that he wrote All Quiet on the Western Front for personal reasons, not for profit, as Friedländer’s ha claimed (Barker and Last, 41).

All Quiet on the Western Front is often ascribed to the school of the Neue Sachlichkeit, or “new objectivity,” which was popular in the post-war Weimar era. This fits with the highly objective, realistic style of the narration. This style attempts to replicate the thoughts and experiences of a soldier during the First World War within the context of that time. The text removes explicit references to later events or foresight towards post-war realizations about the war. [3]

The book is explicitly graphic in language and detail, which is also a characteristic of the Neue Sachlichkeit . It is meant to shock the audience with the horror of war. This fits with Remarque’s intention of accurately replicating the soldier’s experience at the most objective level (Murdoch, 37).

Besides using highly descriptive language, Paul uses the first person plural, “we,” throughout much of the novel. This further emphasizes that Paul is supposed to be more than just an individual soldier, but is representative of each and every individual soldier, whose experiences would be similar (Murdoch, 35).

- ↑ Hans Wagner, Understanding Erich Maria Remarque (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1991), 2, 3.

- ↑ Christine R. Barker and Rex William Last, Erich Maria Remarque (New York: Barnes &amp; Noble Books, 1979), 32-33.

- ↑ Brian Murdoch, The Novels of Erich Maria Remarque: Sparks of Life (Rochester, NY: Camden House 2006), 44.

In collections

Patrick Clardy

Erich Maria Remarque

- Modernism Lab Wikitext (pre-2015 history)

- You do not have permission to view historical versions.

What is a good essay writing service?

Oddly enough, but many people still have not come across a quality service. A large number of users fall for deceivers who take their money without doing their job. And some still fulfill the agreements, but very badly.

A good essay writing service should first of all provide guarantees:

- confidentiality of personal information;

- for the terms of work;

- for the timely transfer of the text to the customer;

- for the previously agreed amount of money.

The company must have a polite support service that will competently advise the client, answer all questions and support until the end of the cooperation. Also, the team must get out of conflict situations correctly.

It is necessary to have several payment methods on the site to make it easier for the client to transfer money.

And of course, only highly qualified writers with a philological education should be present in the team, who will not make spelling and punctuation errors in the text, checking all the information and not stealing it from extraneous sites.

We use cookies. By browsing the site, you agree to it. Read more »

Pricing depends on the type of task you wish to be completed, the number of pages, and the due date. The longer the due date you put in, the bigger discount you get!

Paper Writing Service Price Estimation

How does this work

Final paper.

Adam Dobrinich

Getting an essay writing help in less than 60 seconds

We are inclined to write as per the instructions given to you along with our understanding and background research related to the given topic. The topic is well-researched first and then the draft is being written.

We use cookies to make your user experience better. By staying on our website, you fully accept it. Learn more .

Viola V. Madsen

Emery Evans

Customer Reviews

You are going to request writer Estevan Chikelu to work on your order. We will notify the writer and ask them to check your order details at their earliest convenience.

The writer might be currently busy with other orders, but if they are available, they will offer their bid for your job. If the writer is currently unable to take your order, you may select another one at any time.

Please place your order to request this writer

Look up our reviews and see what our clients have to say! We have thousands of returning clients that use our writing services every chance they get. We value your reputation, anonymity, and trust in us.

Customer Reviews

How safe will my data be with you?

Courtney Lees

Finished Papers

Professional essay writing services

John N. Williams

Finished Papers

Andre Cardoso

Perfect Essay

Customer Reviews

There are questions about essay writing services that students ask about pretty often. So we’ve decided to answer them in the form of an F.A.Q.

Is essay writing legitimate?

As writing is a legit service as long as you stick to a reliable company. For example, is a great example of a reliable essay company. Choose us if you’re looking for competent helpers who, at the same time, don’t charge an arm and a leg. Also, our essays are original, which helps avoid copyright-related troubles.

Are your essay writers real people?

Yes, all our writers of essays and other college and university research papers are real human writers. Everyone holds at least a Bachelor’s degree across a requested subject and boats proven essay writing experience. To prove that our writers are real, feel free to contact a writer we’ll assign to work on your order from your Customer area.

Is there any cheap essay help?

You can have a cheap essay writing service by either of the two methods. First, claim your first-order discount – 15%. And second, order more essays to become a part of the Loyalty Discount Club and save 5% off each order to spend the bonus funds on each next essay bought from us.

Can I reach out to my essay helper?

Contact your currently assigned essay writer from your Customer area. If you already have a favorite writer, request their ID on the order page, and we’ll assign the expert to work on your order in case they are available at the moment. Requesting a favorite writer is a free service.

Sophia Melo Gomes

Hire experienced tutors to satisfy your "write essay for me" requests.

Enjoy free originality reports, 24/7 support, and unlimited edits for 30 days after completion.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

All Quiet On The Western Front Thesis. In Remarque's book, "All Quiet On The Western Front," the main character Paul Baumer, a German soldier in World War One , states that soldiers become "lost" (Remarque 123). This idea that soldiers become lost is illustrated throughout the book as seen when the young men no longer desire their ...

Throughout his novel, Remarque uses nature in several ways. It revitalizes the soldiers after terrible hardships, reflects their sadness, and provides a contrast to the unnatural world of war. When Kemmerich, the first of Paul's classmates dies, Paul takes his identification tags and walks outside.

In All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque the author displays how a man's identity, youth, and innocence is abolished in the war. From shellings and bombardments, to playing skat and going home, Paul and his comrades have had their lives vanish before their eyes. War is more than just an event that reoccurs over time, it is a ...

Brutality of war. Remarque writes in the epigraph that his book will describe the men who were "destroyed by the war," and after that All Quiet on the Western Front is a nearly ceaseless exploration of the destructive properties of The Great War. Included are two detailed chapters about fighting at the front and in the trenches (Chapters Four ...

Thesis Statement All Quiet on the Western Front - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. Scribd is the world's largest social reading and publishing site.

All Quiet on the Western Front Thesis Essay - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free.

Essay Example: In the book All Quiet On The Western Front, Remarque uses the loss of innocence of his characters to show that war breaks and even destroys people. Also Remarque's ground breaking book presents a powerful literary critique of WWI by smashing any ideas about war is heroic and ... Thesis Statement Generator . Generate thesis ...

All Quiet on the Western Front resonates as a powerful anti-war statement, challenging romanticized notions of conflict and highlighting the futility of violence on a personal and societal level ...

In October 1918 , on a day with very little fighting, Paul is killed. The army report for that day reads simply: "All quiet on the Western Front.". Paul's corpse wears a calm expression, as though relieved that the end has come at last. A short summary of Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front.

Creating a thesis statement can be a daunting task. It's one of the most important sentences in your paper, and it needs to be done right. But don't worry — with these five easy steps, you'll be able to create an effective thesis statement ..... Writing a thesis statement can be one of the most challenging parts of writing an essay. A thesis statement is a sentence that summarizes the ...

All Quiet on the Western Front. In 1929, Remarque scored his greatest, and most lasting, success with the novel, All Quiet on the Western Front (Im Westen nichts Neues). The work graphically depicted the horrors and brutality of World War I (1914-1918) through the tragic experiences of a group of young German soldiers. The novel, a lasting ...

One of the most well-known German novelists of the 20th century is Erich Maria Remarque (1898-1970). Remarque has had unpleasant encounters on the Western Front's trenches. The First World War German soldier's physical and psychological agony is the subject of the book "Im Westen nichts Neues," often known as All Quiet on the Western Front.

The story of All Quiet on the Western Front is about young Germans who join WWI after being inspired by patriotism and honor. Paul Baumer, the protagonist, is 20 years old and narrates the story. The young soldiers quickly discover that the idealized picture of combat that was painted for them is a far cry from what they see on the front lines.

Plot. All Quiet on the Western Front describes the experiences of Paul Bäumer, a soldier in the German army of World War I. The novel opens with Paul already on the front lines. It includes the back story of how Paul and his classmates were persuaded to volunteer by their high school teacher, Kantorek. They went through basic training, which ...

All Quiet On The Western Front Thesis, Reference Essay Generator, Case Study Suspected Legionnaires' Disease In Bogalusa, Essay Writing Samples For Grade 12, Cheap Research Paper Ghostwriters Websites For School, Thesis Statement About Family Problems, Essay On Leonardo Da Vinci And Michelangelo

4.7/5. Lydia A. User ID: 102652. 1800. Finished Papers. Thesis Statement For All Quiet On The Western Front, Esl Reflective Essay Proofreading For Hire Ca, Sample Resume Loan Officer Position, Iinet Nbn Business Plan, Key Case Study Definition, What Is Homework In Spanish, Propaganda Under A Dictatorship Thesis.

You can have a cheap essay writing service by either of the two methods. First, claim your first-order discount - 15%. And second, order more essays to become a part of the Loyalty Discount Club and save 5% off each order to spend the bonus funds on each next essay bought from us.

Thesis Statements For All Quiet On The Western Front. The experts well detail out the effect relationship between the two given subjects and underline the importance of such a relationship in your writing. Our cheap essay writer service is a lot helpful in making such a write-up a brilliant one. This exquisite Edwardian single-family house has ...

ID 8764. Your Price: .40 per page. Essay writing help has this amazing ability to save a student's evening. For example, instead of sitting at home or in a college library the whole evening through, you can buy an essay instead, which takes less than one minute, and save an evening or more.

Thesis Statement For All Quiet On The Western Front - ... Thesis Statement For All Quiet On The Western Front: Level: University, College, Master's, High School, PHD, Undergraduate, Entry, Professional. Type of service: Academic writing. 675 ...

All Quiet On The Western Front Thesis Statement - ... All Quiet On The Western Front Thesis Statement: 100% Success rate Featured . Member Login; Sign Up; 1(888)499-5521. 1(888)814-4206. 2640 Orders prepared. Essay, Research paper, Coursework, Discussion Board Post, Powerpoint Presentation, Questions-Answers, Term paper, Case Study, Research ...

Editing. All Quiet On The Western Front Thesis Statements. About Writer. Deadline: 506. Finished Papers. We accept. phonelink_ringToll free: 1 (888)499-5521 1 (888)814-4206. 435.

That is exactly why thousands of them come to our essay writers service for an additional study aid for their children. By working with our essay writers, you can get a high-quality essay sample and use it as a template to help them succeed. Help your kids succeed and order a paper now! User ID: 123019. Level: College, University, High School ...