Lyrical Nonsense

Yoko Takahashi - The Cruel Angel's Thesis (残酷な天使のテーゼ) [Zankoku na Tenshi no Thesis] Lyrics (Romanized)

Home » Artists » Yoko Takahashi » The Cruel Angel's Thesis Lyrics / English Translation

The Cruel Angel's Thesis Lyrics (Romanized)

- Translations

- SIDE-BY-SIDE

zankoku na tenshi no you ni shounen yo shinwa ni nare

aoi kaze ga ima mune no doa wo tataitemo Watashi dake wo tada mitsumete hohoenderu anata Sotto fureru mono motomeru koto ni muchuu de Unmei sae mada shiranai itaike na hitomi

dakedo itsuka kizuku deshou sono senaka ni wa Haruka mirai mezasu tame no hane ga aru koto

zankoku na tenshi no teeze madobe kara yagate tobitatsu Hotobashiru atsui patosu de omoide wo uragiru nara Kono sora wo daite kagayaku shounen yo shinwa ni nare

zutto nemutteru watashi no ai no yurikago Anata dake ga yume no shisha ni yobareru asa ga kuru Hosoi kubisuji wo tsukiakari ga utsushiteru Sekaijuu no toki wo tomete tojikometai kedo

moshi mo futari aeta koto ni imi ga aru nara Watashi wa sou jiyuu wo shiru tame no baiburu

zankoku na tenshi no teeze kanashimi ga soshite hajimaru Dakishimeta inochi no katachi sono yume ni mezameta toki Dare yori mo hikari wo hanatsu shounen yo shinwa ni nare

hito wa ai wo tsumugi nagara rekishi wo tsukuru Megami nante narenai mama watashi wa ikiru

View Favorites

Japanese music enthusiast and lyrical translator. JLPT N1 certified with more than 15 years of experience in the Japanese and Global music communities.

Come to our Discord server to join the LN Community and connect with fellow music lovers!

Want to help add your favorite songs and artists, or discover something completely new? Check out how to join our team!

And you can always send me a coffee to keep me going! 💙 (/・ω・)/ ☕彡 ヽ(^。^)ノ

Yoko Takahashi - The Cruel Angel's Thesis Lyrics (Romanized)

Yoko Takahashi - Zankoku na Tenshi no Thesis Lyrics (Romanized)

Yoko Takahashi - 残酷な天使のテーゼ Lyrics (Romanized)

Neon Genesis Evangelion Opening Theme Lyrics (Romanized)

Shinseiki Evangelion Opening Theme Lyrics (Romanized)

残酷な天使のように 少年よ神話になれ

蒼い風がいま 胸のドアを叩いても 私だけをただ見つめて微笑んでるあなた そっとふれるもの もとめることに夢中で 運命さえまだ知らない いたいけな瞳

だけどいつか気付くでしょう その背中には 遥か未来めざすための羽根があること

残酷な天使のテーゼ 窓辺からやがて飛び立つ ほとばしる熱いパトスで 思い出を裏切るなら この宇宙(そら)を抱いて輝く 少年よ神話になれ

ずっと眠ってる 私の愛の揺りかご あなただけが夢の使者に呼ばれる朝がくる 細い首筋を 月あかりが映してる 世界中の時を止めて閉じこめたいけど

もしもふたり逢えたことに意味があるなら 私はそう 自由を知るためのバイブル

残酷な天使のテーゼ 悲しみがそしてはじまる 抱きしめた命のかたち その夢に目覚めたとき 誰よりも光を放つ 少年よ神話になれ

人は愛をつむぎながら歴史をつくる 女神なんてなれないまま 私は生きる

残酷な天使のテーゼ 窓辺からやがて飛び立つ ほとばしる熱いパトスで 思い出を裏切るなら この宇宙を抱いて輝く 少年よ神話になれ

- English (Official)

- + Submit a translation

Like a cruel angel, young boy, become a legend!

A blue wind is now knocking at the door to your heart, And yet you are merely gazing at me and smiling. Something gently touches, you’re so intent on seeking it out, That you can’t even see your fate yet, with such innocent eyes.

But someday I think you’ll find out that what’s on your back Are wings that are for heading for the far-off future.

The cruel angel’s thesis will soon take flight through the window, With surging hot pathos, if you betray your memories. Embracing this universe and shining, young boy, become a legend!

Sleeping for a long time in the cradle of my love The morning is coming when you alone will be called by a messenger of dreams. Moonlight reflects off the nape of your slender neck. Stopping time all throughout the world, I want to confine them, but…

So if two people being brought together by fate has any meaning, I think that it is a “bible” for learning freedom.

The cruel angel’s thesis. The sorrow then begins. You held tight to the form of life when you woke up from that dream. You shine brighter than anyone else. Young boy, become a legend!

People create history while weaving love. Even knowing I’ll never be a goddess, or anything like that, I live on.

Do you have a translation you'd like to see here on LN? You can submit it using the form below!

* Which language is your translation in?

—Please choose an option— English English (Official Source) Dutch French Indonesian Japanese Malay Portuguese Spanish Turkish

(If your language is not listed, we are currently unable to accept it at this time. If you are interested in becoming a community translation checker for your language, please get in touch via our official Discord!)

* Your Translation

Please ensure that the number of lines in each paragraph match the original lyrics whenever possible.

* Your Email

* What is the source of your translation? (Personal, official subtitles, etc.)

Do not submit auto-translated content. Submissions from automated translation services will be denied.

Do not copy unofficial translations from other sites. Submissions reposting someone else's work without permission will be denied.

☆ Please note: If accepted, your translation will be credited as an LN Community submission, where other members can provide input and submit improvements.

You can join the LN Community and meet other translators on our Discord .

If you're interested in translating regularly as part of the LN Team, check out the application details on our About / Recruitment page.

As always, thank you for sharing your translations with the world!

Yoko Takahashi『The Cruel Angel's Thesis』Official Music Video

- Official Music Video

* Which type of video are you submitting?

—Please choose an option— Official Music Video Official Lyric Video Official Audio Official Visualizer Topic Video (Provided to YouTube by...) Acoustic Version Animation MV Choreography Video Dance Video Dance Performance Video Dance Practice Video Ending Video Instrumental Live MV Live Performance MV Behind the Scenes MV Making MV Reaction Opening Video Performance Video Recording Video Special Video THE FIRST TAKE

( Via this form, we can only accept YouTube videos from official channels. If you would like to advertise a cover of your own, or someone else's, please check out how you can promote a video !)

* Video URL

* Please Enter Your Email

Your Thoughts: Cancel reply

Related yoko takahashi - the cruel angel's thesis related lyrics.

NEW & RECOMMENDED

TOP RANKING

- ABOUT / JOIN US!

Anime Lyrics . Com

- Japanese Tests

- J-Pop / J-Rock

- Dance CD List

- # , A , B , C , D , E , F , G , H , I , J , K , L , M , N , O , P , Q , R , S , T , U , V , W , X , Y , Z

- Search: All Show Title Performer Song Lyrics in All Categories Anime Game J-pop / J-Rock Dancemania Dance CD List Doujin

- Neon Genesis Evangelion

- Zankoku na Tenshi no TE-ZE - Cruel Angel's Thesis

Contributed by Takayama Miyuki [email protected] >

See an error in these lyrics? Let us know here!

- Privacy Policy

- Advertise on AnimeLyrics

Takahashi Youko - Zankoku na Tenshi no TE-ZE Lyrics

Neon genesis evangelion opening theme lyrics.

- Side by Side

- Neon Genesis Evangelion Ending Theme Lyrics

- More Neon Genesis Evangelion Lyrics

- Music Video

- Shin Seiki Evangelion

- Shinseiki Evangelion

- EVANGELION:1.0 YOU ARE (NOT) ALONE

- EVANGELION:2.0 YOU CAN (NOT) ADVANCE

- EVANGELION:3.0 YOU CAN (NOT) REDO

- Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time

- Movie: REVIVAL OF EVANGELION (DEATH (TRUE)² / Air/Magokoro wo Kimi ni): March 7, 1998

- Movie: The End of Evangelion (Air/Magokoro wo Kimi ni): July 19, 1997

- Movie: Death and Rebirth (Shito Shinsei): March 15, 1997

- Original TV: October 4, 1995

Soundtracks: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z #

List of artists: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z #

A Cruel Angel's Thesis Lyrics - Yoko Takahashi

Soundtrack: neon genesis evangelion, a cruel angel's thesis song lyrics.

- Neon Genesis Evangelion

- A Cruel Angel's Thesis Lyrics

- Track Name: "A Cruel Angel's Thesis"

- Genre: J-Pop, Anime Soundtrack

- Release Date: 1995

- Composers: Hidetoshi Satō

- Lyricist: Neko Oikawa

- Arrangement: Toshiyuki Ōmori

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

A Cruel Angel's Thesis

Audio with external links item preview.

Share or Embed This Item

Flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

5,155 Views

8 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

In collections.

Uploaded by Hououin Kyouma on August 3, 2019

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

A Cruel Angel's Thesis - Single

April 17, 2024 1 Song, 4 minutes ℗ 2024 V0RA

More By V0RA

Select a country or region, africa, middle east, and india.

- Côte d’Ivoire

- Congo, The Democratic Republic Of The

- Guinea-Bissau

- Niger (English)

- Congo, Republic of

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- South Africa

- Tanzania, United Republic Of

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

Asia Pacific

- Indonesia (English)

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Malaysia (English)

- Micronesia, Federated States of

- New Zealand

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Solomon Islands

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- France (Français)

- Deutschland

- Luxembourg (English)

- Moldova, Republic Of

- North Macedonia

- Portugal (Português)

- Türkiye (English)

- United Kingdom

Latin America and the Caribbean

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Argentina (Español)

- Bolivia (Español)

- Virgin Islands, British

- Cayman Islands

- Chile (Español)

- Colombia (Español)

- Costa Rica (Español)

- República Dominicana

- Ecuador (Español)

- El Salvador (Español)

- Guatemala (Español)

- Honduras (Español)

- Nicaragua (Español)

- Paraguay (Español)

- St. Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- St. Vincent and The Grenadines

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Turks and Caicos

- Uruguay (English)

- Venezuela (Español)

The United States and Canada

- Canada (English)

- Canada (Français)

- United States

- Estados Unidos (Español México)

- الولايات المتحدة

- États-Unis (Français France)

- Estados Unidos (Português Brasil)

- 美國 (繁體中文台灣)

select all of the qualities of a valid hypothesis

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Biology library

Course: biology library > unit 1, the scientific method.

- Controlled experiments

- The scientific method and experimental design

Introduction

- Make an observation.

- Ask a question.

- Form a hypothesis , or testable explanation.

- Make a prediction based on the hypothesis.

- Test the prediction.

- Iterate: use the results to make new hypotheses or predictions.

Scientific method example: Failure to toast

1. make an observation..

- Observation: the toaster won't toast.

2. Ask a question.

- Question: Why won't my toaster toast?

3. Propose a hypothesis.

- Hypothesis: Maybe the outlet is broken.

4. Make predictions.

- Prediction: If I plug the toaster into a different outlet, then it will toast the bread.

5. Test the predictions.

- Test of prediction: Plug the toaster into a different outlet and try again.

- If the toaster does toast, then the hypothesis is supported—likely correct.

- If the toaster doesn't toast, then the hypothesis is not supported—likely wrong.

Logical possibility

Practical possibility, building a body of evidence, 6. iterate..

- Iteration time!

- If the hypothesis was supported, we might do additional tests to confirm it, or revise it to be more specific. For instance, we might investigate why the outlet is broken.

- If the hypothesis was not supported, we would come up with a new hypothesis. For instance, the next hypothesis might be that there's a broken wire in the toaster.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

What Are the Elements of a Good Hypothesis?

Hero Images/Getty Images

- Scientific Method

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Projects & Experiments

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

A hypothesis is an educated guess or prediction of what will happen. In science, a hypothesis proposes a relationship between factors called variables. A good hypothesis relates an independent variable and a dependent variable. The effect on the dependent variable depends on or is determined by what happens when you change the independent variable . While you could consider any prediction of an outcome to be a type of hypothesis, a good hypothesis is one you can test using the scientific method. In other words, you want to propose a hypothesis to use as the basis for an experiment.

Cause and Effect or 'If, Then' Relationships

A good experimental hypothesis can be written as an if, then statement to establish cause and effect on the variables. If you make a change to the independent variable, then the dependent variable will respond. Here's an example of a hypothesis:

If you increase the duration of light, (then) corn plants will grow more each day.

The hypothesis establishes two variables, length of light exposure, and the rate of plant growth. An experiment could be designed to test whether the rate of growth depends on the duration of light. The duration of light is the independent variable, which you can control in an experiment . The rate of plant growth is the dependent variable, which you can measure and record as data in an experiment.

Key Points of Hypothesis

When you have an idea for a hypothesis, it may help to write it out in several different ways. Review your choices and select a hypothesis that accurately describes what you are testing.

- Does the hypothesis relate an independent and dependent variable? Can you identify the variables?

- Can you test the hypothesis? In other words, could you design an experiment that would allow you to establish or disprove a relationship between the variables?

- Would your experiment be safe and ethical?

- Is there a simpler or more precise way to state the hypothesis? If so, rewrite it.

What If the Hypothesis Is Incorrect?

It's not wrong or bad if the hypothesis is not supported or is incorrect. Actually, this outcome may tell you more about a relationship between the variables than if the hypothesis is supported. You may intentionally write your hypothesis as a null hypothesis or no-difference hypothesis to establish a relationship between the variables.

For example, the hypothesis:

The rate of corn plant growth does not depend on the duration of light.

This can be tested by exposing corn plants to different length "days" and measuring the rate of plant growth. A statistical test can be applied to measure how well the data support the hypothesis. If the hypothesis is not supported, then you have evidence of a relationship between the variables. It's easier to establish cause and effect by testing whether "no effect" is found. Alternatively, if the null hypothesis is supported, then you have shown the variables are not related. Either way, your experiment is a success.

Need more examples of how to write a hypothesis ? Here you go:

- If you turn out all the lights, you will fall asleep faster. (Think: How would you test it?)

- If you drop different objects, they will fall at the same rate.

- If you eat only fast food, then you will gain weight.

- If you use cruise control, then your car will get better gas mileage.

- If you apply a top coat, then your manicure will last longer.

- If you turn the lights on and off rapidly, then the bulb will burn out faster.

- Null Hypothesis Definition and Examples

- Six Steps of the Scientific Method

- What Is a Hypothesis? (Science)

- Understanding Simple vs Controlled Experiments

- Dependent Variable Definition and Examples

- How To Design a Science Fair Experiment

- Null Hypothesis Examples

- Scientific Method Vocabulary Terms

- Scientific Method Flow Chart

- What Are Independent and Dependent Variables?

- Definition of a Hypothesis

- Scientific Variable

- What Is an Experiment? Definition and Design

- What Is a Testable Hypothesis?

- What Is a Control Group?

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.5: Developing A Hypothesis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 75017

- University of Missouri–St. Louis

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis, it is important to distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition (1965). He pro- posed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are atheoretical and only after a set of observations has been made is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observations before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relation- ship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster and through a branching runway more slowly when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus, deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feel- ings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991). Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged them- selves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

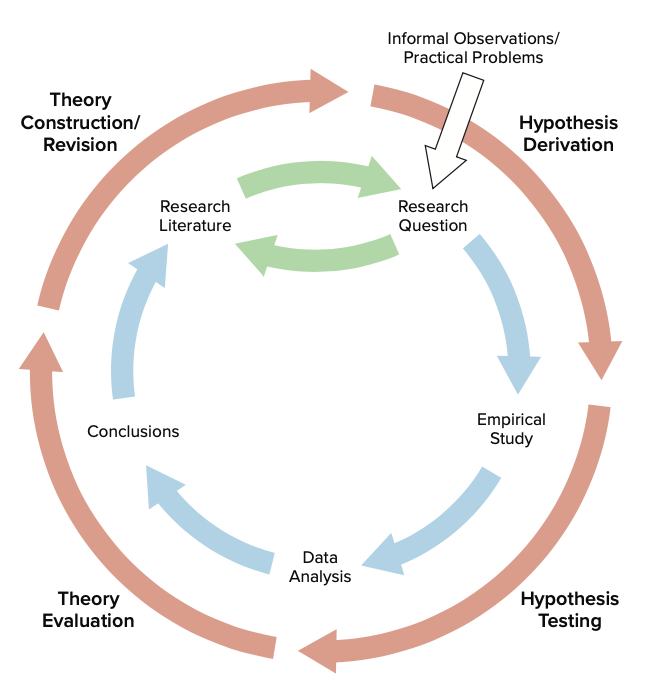

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is some- times called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). Researchers begin with a set of phenomena and either construct a theory to explain or interpret the phenomena or choose an existing theory to work with. They then make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this pre- diction is called a hypothesis. The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they reevaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969). The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cock- roach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cock- roaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans [Zajonc & Sales, 1966] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science, and it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical . As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, how- ever, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive . That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that it really does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

The Scientific Method

Hypothesis format.

Falsifiability of a hypothesis, operational definitions, types of hypotheses, hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

Frequently Asked Questions

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study.

One hypothesis example would be a study designed to look at the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance might have a hypothesis that states: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. It is only at this point that researchers begin to develop a testable hypothesis. Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore a number of factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk wisdom that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in a number of different ways. One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. How would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

In order to measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming other people. In this situation, the researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests that there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent variables and a dependent variable.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative sample of the population and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- Complex hypothesis: "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have scores different than students who do not receive the intervention."

- "There will be no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will perform better than students who did not receive the intervention."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when it would be impossible or difficult to conduct an experiment . These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can then be used to look at how the variables are related. This type of research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

A Word From Verywell

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Some examples of how to write a hypothesis include:

- "Staying up late will lead to worse test performance the next day."

- "People who consume one apple each day will visit the doctor fewer times each year."

- "Breaking study sessions up into three 20-minute sessions will lead to better test results than a single 60-minute study session."

The four parts of a hypothesis are:

- The research question

- The independent variable (IV)

- The dependent variable (DV)

- The proposed relationship between the IV and DV

Castillo M. The scientific method: a need for something better? . AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(9):1669-71. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A3401

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

2.4 Developing a Hypothesis

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis it is imporant to distinguish betwee a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition. He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observation before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [1] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). A researcher begins with a set of phenomena and either constructs a theory to explain or interpret them or chooses an existing theory to work with. He or she then makes a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researcher then conducts an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, he or she reevaluates the theory in light of the new results and revises it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researcher can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.2 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

Figure 2.2 Hypothetico-Deductive Method Combined With the General Model of Scientific Research in Psychology Together they form a model of theoretically motivated research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [2] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans (Zajonc & Sales, 1966) [3] in many other studies afterward).

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that really it does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

Key Takeaways

- A theory is broad in nature and explains larger bodies of data. A hypothesis is more specific and makes a prediction about the outcome of a particular study.

- Working with theories is not “icing on the cake.” It is a basic ingredient of psychological research.

- Like other scientists, psychologists use the hypothetico-deductive method. They construct theories to explain or interpret phenomena (or work with existing theories), derive hypotheses from their theories, test the hypotheses, and then reevaluate the theories in light of the new results.

- Practice: Find a recent empirical research report in a professional journal. Read the introduction and highlight in different colors descriptions of theories and hypotheses.

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Hypothesis Testing | A Step-by-Step Guide with Easy Examples

Published on November 8, 2019 by Rebecca Bevans . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics . It is most often used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses, that arise from theories.

There are 5 main steps in hypothesis testing:

- State your research hypothesis as a null hypothesis and alternate hypothesis (H o ) and (H a or H 1 ).

- Collect data in a way designed to test the hypothesis.

- Perform an appropriate statistical test .

- Decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis.

- Present the findings in your results and discussion section.

Though the specific details might vary, the procedure you will use when testing a hypothesis will always follow some version of these steps.

Table of contents

Step 1: state your null and alternate hypothesis, step 2: collect data, step 3: perform a statistical test, step 4: decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis, step 5: present your findings, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about hypothesis testing.

After developing your initial research hypothesis (the prediction that you want to investigate), it is important to restate it as a null (H o ) and alternate (H a ) hypothesis so that you can test it mathematically.

The alternate hypothesis is usually your initial hypothesis that predicts a relationship between variables. The null hypothesis is a prediction of no relationship between the variables you are interested in.

- H 0 : Men are, on average, not taller than women. H a : Men are, on average, taller than women.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

For a statistical test to be valid , it is important to perform sampling and collect data in a way that is designed to test your hypothesis. If your data are not representative, then you cannot make statistical inferences about the population you are interested in.

There are a variety of statistical tests available, but they are all based on the comparison of within-group variance (how spread out the data is within a category) versus between-group variance (how different the categories are from one another).

If the between-group variance is large enough that there is little or no overlap between groups, then your statistical test will reflect that by showing a low p -value . This means it is unlikely that the differences between these groups came about by chance.

Alternatively, if there is high within-group variance and low between-group variance, then your statistical test will reflect that with a high p -value. This means it is likely that any difference you measure between groups is due to chance.

Your choice of statistical test will be based on the type of variables and the level of measurement of your collected data .

- an estimate of the difference in average height between the two groups.

- a p -value showing how likely you are to see this difference if the null hypothesis of no difference is true.

Based on the outcome of your statistical test, you will have to decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis.

In most cases you will use the p -value generated by your statistical test to guide your decision. And in most cases, your predetermined level of significance for rejecting the null hypothesis will be 0.05 – that is, when there is a less than 5% chance that you would see these results if the null hypothesis were true.

In some cases, researchers choose a more conservative level of significance, such as 0.01 (1%). This minimizes the risk of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis ( Type I error ).

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The results of hypothesis testing will be presented in the results and discussion sections of your research paper , dissertation or thesis .

In the results section you should give a brief summary of the data and a summary of the results of your statistical test (for example, the estimated difference between group means and associated p -value). In the discussion , you can discuss whether your initial hypothesis was supported by your results or not.

In the formal language of hypothesis testing, we talk about rejecting or failing to reject the null hypothesis. You will probably be asked to do this in your statistics assignments.

However, when presenting research results in academic papers we rarely talk this way. Instead, we go back to our alternate hypothesis (in this case, the hypothesis that men are on average taller than women) and state whether the result of our test did or did not support the alternate hypothesis.

If your null hypothesis was rejected, this result is interpreted as “supported the alternate hypothesis.”

These are superficial differences; you can see that they mean the same thing.

You might notice that we don’t say that we reject or fail to reject the alternate hypothesis . This is because hypothesis testing is not designed to prove or disprove anything. It is only designed to test whether a pattern we measure could have arisen spuriously, or by chance.

If we reject the null hypothesis based on our research (i.e., we find that it is unlikely that the pattern arose by chance), then we can say our test lends support to our hypothesis . But if the pattern does not pass our decision rule, meaning that it could have arisen by chance, then we say the test is inconsistent with our hypothesis .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Descriptive statistics

- Measures of central tendency

- Correlation coefficient

Methodology

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Types of interviews

- Cohort study

- Thematic analysis

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Survivorship bias

- Availability heuristic

- Nonresponse bias

- Regression to the mean

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bevans, R. (2023, June 22). Hypothesis Testing | A Step-by-Step Guide with Easy Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/statistics/hypothesis-testing/

Is this article helpful?

Rebecca Bevans

Other students also liked, choosing the right statistical test | types & examples, understanding p values | definition and examples, what is your plagiarism score.

University of Lethbridge

Science Toolkit

What is a Hypothesis?

A hypothesis (plural: hypotheses) is in its simplest form nothing more than an idea about how the world works. For example, “the moon is made of green cheese” is a valid hypothesis. But there are several characteristics which separate useful scientific hypotheses from those which are impractical. First and foremost, a hypothesis must be testable. We must (at least in principle) be able to design an experiment which will allow us to determine whether the hypothesis is false. Keep in mind that we can never prove any hypothesis is completely true because we can always

English chemist Robert Boyle (1627-1691) was one of the first scientists to explicitly adopt a program of hypothesis testing. imagine new circumstances in which it has not been tested, or other possible explanations for the results we have obtained. It is much easier to show, with a high degree of confidence, that a hypothesis is false. If it is not consistent with the results of a well designed and executed experiment, we are forced to accept that the hypothesis is false. If a hypothesis is not falsifiable, it is outside the realm of science. Note that the “green-cheese hypothesis” meets this test. A hypothesis should also be plausible. That is, the hypothesis, should be consistent with what we already know about the subject being investigated, and its parts should be logically and mathematically sound. We often celebrate the creative spark by which new hypotheses come to light. But typically that moment of inspiration follows a great deal of perspiration racked up in a thorough review of previous research in the subject. A hypothesis may in the end be a guess, but it should be the best guess possible. Given what we know about astronomy (and cheese production) the”green-cheese hypothesis” is not plausible, and not worth investing much of our time and resources in testing. What are predictions?

The predictions of a hypothesis set out what we expect to see if the hypothesis is true. (This is where we use deductive “If-Then” logic.) Experiments are designed to test specific predictions of the hypothesis. The “green-cheese hypothesis” predicts that material collected from the moon would contain milk proteins and fungi. These predictions could be tested by bringing material back from the moon, and testing its chemical structure. The hypothesis also makes predictions about the wavelengths of light reflected from the moon, a field called spectroscopy. (These predictions have actually been tested, believe it or not. Needless to say the hypothesis was not supported!) Three main factors make a prediction useful in testing a hypothesis: The prediction should be specific to the hypothesis (i.e. no other hypotheses make the same prediction). If several hypotheses predict the same outcome of an experiment, we will need to do further experiments to distinguish between them. The prediction should provide results which are unambiguous. It should be practical and economically feasible to run the experiment. A prediction is really nothing more than a simpler hypothesis — practical to test — derived from a larger hypothesis. Note that a prediction does not have be about the future, but it does have to apply to a situation we have not looked at yet. We are free to use the results of previous experiments to develop a new hypothesis, but we can’t then test our predictions against the results of those old experiments — to do so would be arguing in circles. Are theories different from hypotheses?

A “theory” has no formal definition in science (Style Manual Committee, CBE 1994). Hypotheses which have considerable support from experiments, and which are useful in explaining a fairly wide range of phenomena, are “upgraded” to theories, for example Darwin’s Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection, or the Theory of Plate Tectonics (which explains the movement of continents). So a theory is simply a well-tested and widely useful hypothesis, and there’s no strict rules defining when a hypothesis becomes a theory. Theories which are extremely well supported by experiments, particularly those which can be expressed as simple mathematical equations, are often called laws, e.g. Newton’s Law of Gravitation, Kepler’s Laws of Motion, or Mendel’s Laws of Genetics. Again, no one has yet laid out a strict set of rules for defining a natural law. A final term that scientists use to describe their ideas is a model. This dates back to the time when physical models were one of the few tools researchers had in investigating phenomena which were too big or too small to manipulate directly. Physical models are still used in science. Francis Crick and James Watson used a scale model of a DNA molecule to help them deduce its structure (Giere 1997). But scientists also use mathematical models to help them understand how different factors will interact. The development of computers has vastly increased the scope of mathematical models, and made them accessible even to non-mathematicians. Why are hypotheses important?

Philosopher of science Karl Popper likened a hypothesis to a searchlight, which the researcher shines on the relevant portion of nature (Davies 1973). It tells us which experiments are the important ones to perform, and which observations the important ones to make, out of an infinite number of possibilities. Without hypotheses scientists would be reduced to bean counters, and science to a collection of facts without organization or purpose. A hypothesis is the cornerstone used in building an elegant, structured body of knowledge from the apparent chaos of nature. (So they’re pretty important, eh!)

The Best PhD and Masters Consulting Company

Characteristics Of A Good Hypothesis

What exactly is a hypothesis.

A hypothesis is a conclusion reached after considering the evidence. This is the first step in any investigation, where the research questions are translated into a prediction. Variables, population, and the relationship between the variables are all included. A research hypothesis is a hypothesis that is tested to see if two or more variables have a relationship. Now let’s have a look at the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Characteristics of

A good hypothesis has the following characteristics.

Ability To Predict

Closest to things that can be seen, testability, relevant to the issue, techniques that are applicable, new discoveries have been made as a result of this ., harmony & consistency.

- The similarity between the two phenomena.

- Observations from previous studies, current experiences, and feedback from rivals.

- Theories based on science.

- People’s thinking processes are influenced by general patterns.

- A straightforward hypothesis

- Complex Hypothesis

- Hypothesis with a certain direction

- Non-direction Hypothesis

- Null Hypothesis

- Hypothesis of association and chance

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

1.1: Scientific Investigation

- Page ID 6252

Chances are you've heard of the scientific method. But what exactly is the scientific method?

Is it a precise and exact way that all science must be done? Or is it a series of steps that most scientists generally follow, but may be modified for the benefit of an individual investigation?

"We also discovered that science is cool and fun because you get to do stuff that no one has ever done before." In the article Blackawton bees, published by eight to ten year old students: Biology Letters (2010) http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2010/12/18/rsbl.2010.1056.abstract .

There are basic methods of gaining knowledge that are common to all of science. At the heart of science is the scientific investigation, which is done by following the scientific method . A scientific investigation is a plan for asking questions and testing possible answers. It generally follows the steps listed in Figure below . See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KZaCy5Z87FA for an overview of the scientific method.

Steps of a Scientific Investigation. A scientific investigation typically has these steps. Scientists often develop their own steps they follow in a scientific investigation. Shown here is a simplification of how a scientific investigation is done.

Making Observations

A scientific investigation typically begins with observations. You make observations all the time. Let’s say you take a walk in the woods and observe a moth, like the one in Figure below, resting on a tree trunk. You notice that the moth has spots on its wings that look like eyes. You think the eye spots make the moth look like the face of an owl.

Figure 2: Marbled emperor moth Heniocha dyops in Botswana. (CC-SA-BY-4.0; Charlesjsharp ).

Does this moth remind you of an owl?

Asking a Question

Observations often lead to questions. For example, you might ask yourself why the moth has eye spots that make it look like an owl’s face. What reason might there be for this observation?

Forming a Hypothesis

The next step in a scientific investigation is forming a hypothesis . A hypothesis is a possible answer to a scientific question, but it isn’t just any answer. A hypothesis must be based on scientific knowledge, and it must be logical. A hypothesis also must be falsifiable. In other words, it must be possible to make observations that would disprove the hypothesis if it really is false. Assume you know that some birds eat moths and that owls prey on other birds. From this knowledge, you reason that eye spots scare away birds that might eat the moth. This is your hypothesis.

Testing the Hypothesis

To test a hypothesis, you first need to make a prediction based on the hypothesis. A prediction is a statement that tells what will happen under certain conditions. It can be expressed in the form: If A occurs, then B will happen. Based on your hypothesis, you might make this prediction: If a moth has eye spots on its wings, then birds will avoid eating it.

Next, you must gather evidence to test your prediction. Evidence is any type of data that may either agree or disagree with a prediction, so it may either support or disprove a hypothesis. Evidence may be gathered by an experiment . Assume that you gather evidence by making more observations of moths with eye spots. Perhaps you observe that birds really do avoid eating moths with eye spots. This evidence agrees with your prediction.

Drawing Conclusions

Evidence that agrees with your prediction supports your hypothesis. Does such evidence prove that your hypothesis is true? No; a hypothesis cannot be proven conclusively to be true. This is because you can never examine all of the possible evidence, and someday evidence might be found that disproves the hypothesis. Nonetheless, the more evidence that supports a hypothesis, the more likely the hypothesis is to be true.

Communicating Results

The last step in a scientific investigation is communicating what you have learned with others. This is a very important step because it allows others to test your hypothesis. If other researchers get the same results as yours, they add support to the hypothesis. However, if they get different results, they may disprove the hypothesis.