Social Construction of Race: Examples, Definition, Criticism

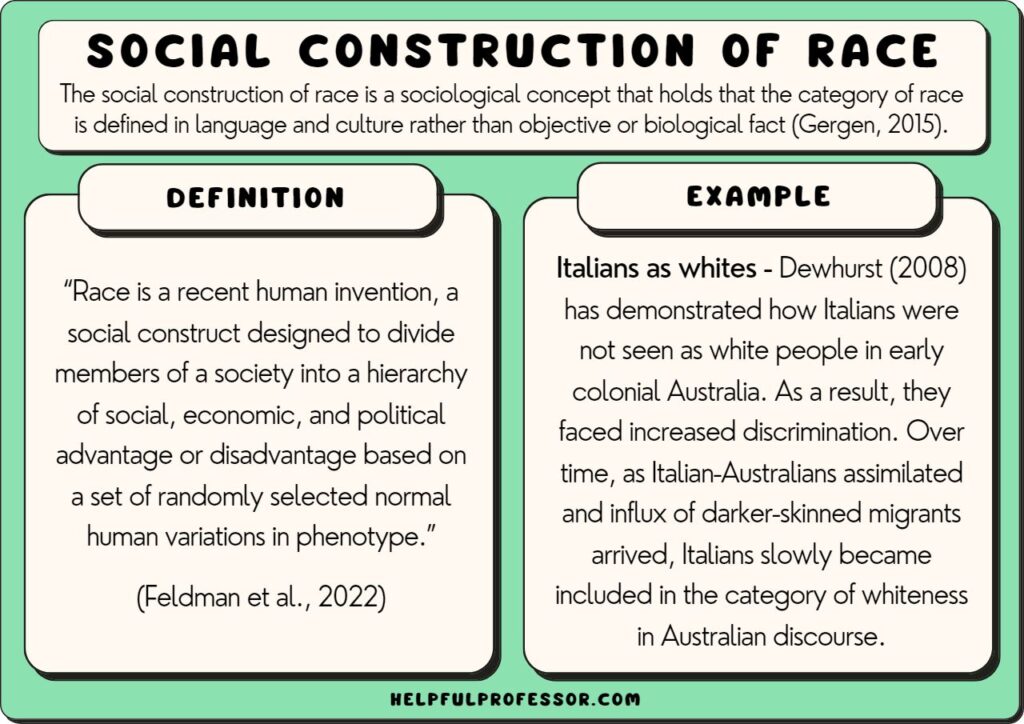

The social construction of race is a sociological concept that holds that the category of race is defined in language and culture rather than objective or biological fact (Gergen, 2015).

It emphasizes that race is not a biological fact, but rather a socially constructed concept that is constructed differently across different societies and cultures, and that can change over time.

From this perspective, society is seen as the source of racial categories. To exemplify this model, scholars have shown how the racial category of “white” has change over time. Whereas once Italians were considered non-whites, they tend to be seen as white people today.

Critics, however, argue that the idea that identity categories like race are “socially constructed” lacks any basis in science and fails to acknowledge biological differences between racial groups.

How is Race a Social Construct?

A social construct is a category that is primarily defined socially. Often, we consider gender, social class, and beauty to be ideas that are constructed by society.

The simplest way to understand this idea is to compare current ideas about categories to past ideas about the same things.

For example, 150 years ago, the idea of ideal beauty was different to today. There was a time when plump women were seen as the epitome beautiful because it was a sign that they were wealthy and had good taste for cuisine!

We can then look at this idea for social categories that we tend to believe to be more biological, such as race and gender.

For example, the social idea of a woman as ‘property’ or incapable of leadership was once normal but is now entirely unacceptable. Here, gender as a social construct changed, and now our idea of what a woman is (and is not) has changed (Butler, 2004).

For race, we can look at the era of slavery in the USA. A mere 200 years ago, African-Americans were literally seen as unintelligent and property with the same status as animals. Clearly, the concept of an African-American in the public imagination today versus back then is completely different (Burr, 2015).

Here, we can see that the idea of an African American has been socially constructed , and this social construct has changed over time.

Racialization: From Skin Pigmentation to Moral Capacity

Many scholars argue that race is one of the most important social categories by which arbitrary social hierarchies are created.

The argument is that skin pigmentation, geographical location, and culture were used as key ways to classify people into racialized groups – black, white, etc.

This categorization is seen to be somewhat arbitrary because there are more differences between people within races than across races. Why were intelligence, height, skill, age, or body weight not used as categories for constructing hierarchies instead of skin color?

As Feldman et al. (2022) argue:

“Race is a recent human invention, a social construct designed to divide members of a society into a hierarchy of social, economic, and political advantage or disadvantage based on a set of randomly selected normal human variations in phenotype.” (Feldman et al., 2022)

This isn’t to say that there weren’t physical differences in ethnic groups throughout history, but rather than the idea of race as a key way to construct social hierarchies and prejudices is relatively new in human history.

History shows that choosing race as a key way to produce social heirarchies and prejudices has led to devastating damage to hundreds of millions of people. The effects of the racialization of society continues to this day.

Thus, scholars today attempt to explore how normal variations in phenotype were used to construct race categories that extended beyond just minor physical variations and arbitrarily superimposed ideas about intellect and morality onto social ideas about racial groups:

“The ideology of race became a means of maintaining a social system that stratified people based on physical appearance and assigned individuals from each racial group with inherent cognitive, emotional, physical, behavioral, and moral characteristics, which were ultimately adopted as societal beliefs.” (Morukian, 2022)

Interestingly, a lot of the research on the social construction of disability directly follows-on from this logic.

Note that there are arguments against this perspective, e.g. from medical scientists who explore the unique healthcare disparities across racial categories – see the criticisms section at the end of this piece.

Social Construction of Race Examples

- Racial stereotyping – The central way of exploring social construction of race is to examine the stereotypes that exist in the social imaginary. As stereotypes about racial categories change, the very definition of those categories change. As a result, the ways people interact with racial groups also change, which dramatically affects the lives those people can live.

- Italians as whites – Interesting historical research by Dewhurst (2008) has demonstrated how Italians were not seen as white people in early colonial Australia. As a result, they faced increased discrimination. Over time, as Italian-Australians assimilated and influx of darker-skinned migrants arrived, Italians slowly became included in the category of whiteness in Australian discourse.

- African Americans – Whereas in the 18th and early 19th Centuries, African Americans were considered in parts of the USA as the property of whites, lacking legal rights, and being seen as lesser humans. Over time, thankfully, African-American civil rights have been embraced as social construction of African Americans has changed significantly.

- Orientalism – Famous postcolonial scholar Edward Said wrote in Orientalism that Westerners socially construct people Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and the Pacific in simplistic and stereotypical ways. They were seen as backward, simple, irrational, and exotic. Over time, as people have increased their understanding of other cultures, this paternalistic perspective has been tempered, leading to a change in the social construction of nonwhite people.

- Police encounters with black people – Most Western nations have reported disproportionately negative encounters between the police and people of color. Often, but not always, this is based on police stereotypes of black people as untrustworthy or criminal. Were people of color socially constructed in a more positive way in dominant discourse, these encounters may change over time.

- Racialized langauge – The way people are spoken about in media, movies, news, etc. affects how they are socially constructed. 150 years ago, the ways people of color were talked about were horrific by today’s standards. That language helped construct in our social imaginary negative racial stereotypes that worked to construct people of color as a particular type of people.

How Race is Socially Constructed (Still!)

According to poststructural theorists, race is socially constructed whenever it is spoken about. It is through speaking about a race category – repeatedly by many people – that the category is defined and re-defined.

Key ways in which we speak about, and therefore construct, race, include:

- Language – The words we use, the phrases, and the metaphors employed in society all subtly send messages about what to expect of a racial group before you even encounter them.

- Historical Events – The social construction of race can be changed through important historical events. For example, the key events of the Civil Rights era, and the activism of African Americans and allies to change how being black is seen in America, caused a shift in American social understandings of people of color in America.

- Media – Media, including television, movies, and news, all affect how we think about racial groups. Continued negative stereotypes or negative depiction of people of color on media help to perpetuate prejudicial perceptions. Furthermore, the fact media narratives center the experiences of white people contines to caste whites as heroes and non-whites as irrelevant or dehumanized.

- Discourse – Discourse is a term to describe the social narratives that are repeated over and over again until they are seen as natural. Normative racialized discourse is repeated everywhere we look (see also: discourse analysis ).

The way race is socially constructed changes upon two axes:

- Time – Across generations, definitions of racial groups change, and so too do our cross-racial interactions.

- Culture – Social constructs also change across cultures. Different cultures may perceive different racial groups in different ways (so, in this case, we can consider race to be culturally constructed )

Criticisms of the Social Construction of Race

1. race is a biological reality.

If we took a purely biological perspective on the issue of race, it becomes clear that there are clear biological differences between people that can be categorized under scientific categories of race.

Examples of biological differences include skin pigmentation, facial features, height, and susceptibility to certain diseases. These features are hereditary and biological fact (Burr, 2015).

As a result, many people – particularly in the hard sciences – contest the notion of social construction of race .

The primary argument against this criticism is that there are more biological differences within races than between races. No matter the race, humans share a significant majority of features, and race is but one way to categorize and dissect society. Despite this, societies have gotten very hung up on racial categories as a way to divide and discriminate (Smedley & Smedley,. 2005).

Furthermore, the biological categorization of race in medical science is not fixed, either. As science progresses and changes, so too do the definitions of the categories presented in scientific literature.

2. The Social Constructionist Perspective Detracts from Individual Experiences of Racialized People

Many racialized groups believe that their race is a fixed and essential feature of how they self-identify. For example, the unique experience of being Black in America is something many people choose to celebrate.

For these people, a claim that their race is socially constructed may detract from their experience of identity, much in the same way that claiming homosexuality is socially constructed might undermine an LGBTQI+ person’s claim that their sexuality is an inherent part of who they are (Smedley & Smedley,. 2005)..

Nevertheless, most scholars of social constructionism – whose research comes from a symbolic interactionist, postcolonialist , postmodernist, or poststructuralist perspective – tend to hold both that race is a social construct and that a person’s socially constructed race is a part of that person’s lived experience.

Therefore, they tend to examine how a person has been racialized (their race has been socially constructed, often against their will), and then go on to examine how those people relate to, embrace, subvert, and utilize this social construction as part of their identity (Here’ we’re going deep into postmodernism – for more, see my article on postmodernism here ).

Why Study the Social Construction of Race?

If we were to proceed from the premise that race is socially constructed, several lines of academic inquiry are opened up that have important implications.

Most importantly, the knowledge that race is socially constructed opens up opportunities to explore ways to re-construct race in more socially equitable ways.

For example, scholars will often examine how race is constructed in movies and, seeing inequities, advocate for more inclusive representation. This advocacy has made headway in recent years with, as but one example, CBC reality shows committing to a 50% people of color cast for all future seasons.

The idea that race is socially constructed is based on the premise that the definitions of all social categories – including race, gender, and even disability – are socially and culturally mediated. Moving from this premise, scholars can explore how the way we define people can marginalize, normalize, include, or exclude people within society.

Nevertheless, the notion of social constructionism has received significant pushback in recent years, with people arguing that this perspective is undermining reality – i.e. that race is real and we can find objective definitions of racial categories that can last the test of time and, perhaps more importantly, help scientists and researchers focus on improving the health outcomes of people from disadvantaged racial groups.

Read Next: The Social Construction of Childhood

Burr, V. (2015). Social constructionism. New York: Routledge.

Butler, J. (2004). Undoing gender . Cambridge: Routledge.

Dewhirst, C. (2008). Collaborating on whiteness: representing Italians in early White Australia. Journal of Australian Studies , 32 (1), 33-49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050801993800

Feldman, H. M., Blum, N. J., Elias, E. R., Jimenez, M., & Stancin, T. (2022). Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics E-Book . Elsevier Health Sciences.

Gergen, K. J. (2015). An invitation to social construction . An Invitation to Social Construction. London: Sage Publications.

Morukian, M. (2022). Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for Trainers: Fostering DEI in the Workplace . American Society for Training and Development.

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism . London: Sage.Smedley, A., & Smedley, B. D. (2005). Race as biology is fiction, racism as a social problem is real: Anthropological and historical perspectives on the social construction of race. American psychologist , 60 (1), 16. doi: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.16

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The New York Times

Advertisement

The Opinion Pages

Race and racial identity are social constructs.

Angela Onwuachi-Willig , a professor of law at the University of Iowa College of Law, is the author of "According to Our Hearts : Rhinelander v. Rhinelander and the Law of the Multiracial Family."

Updated September 6, 2016, 5:28 PM

Race is not biological. It is a social construct. There is no gene or cluster of genes common to all blacks or all whites. Were race “real” in the genetic sense, racial classifications for individuals would remain constant across boundaries. Yet, a person who could be categorized as black in the United States might be considered white in Brazil or colored in South Africa.

Unlike race and racial identity, the social, political and economic meanings of race, or rather belonging to particular racial groups, have not been fluid.

Like race, racial identity can be fluid. How one perceives her racial identity can shift with experience and time, and not simply for those who are multiracial. These shifts in racial identity can end in categories that our society, which insists on the rigidity of race, has not even yet defined.

As I explain in my book " According to Our Hearts ," whites in interracial black-white marriages or relationships frequently experience a shift in how they personally understand their individual racial identity. In a society where being white (regardless of one’s socioeconomic class background or other disadvantages) means living a life with white skin privileges — such as being presumed safe, competent and noncriminal — whites who begin to experience discrimination because of their intimate connection with someone of another race, or who regularly see their loved ones fall prey to racial discrimination, may begin to no longer feel white. After all, their lived reality does not align with the social meaning of their whiteness.

That all said, unlike race and racial identity, the social, political and economic meanings of race, or rather belonging to particular racial groups, have not been fluid. Racial meanings for non-European groups have remained stagnant. For no group has this reality been truer than African-Americans. What many view as the promising results of the Pew Research Center’s data on multiracial Americans, with details of a growing multiracial population and an increasing number of interracial marriages, does not foreshadow as promising a future for individuals of African descent as it does for other groups of color.

Unlike their multiracial peers of Asian and Native American ancestry who tend to view themselves as having more in common with monoracial whites than with Asians or Native Americans, respectively, multiracial adults with a black background — 69 percent of whom say most people would view them as black — experience prejudice and interactions in ways that are much more closely aligned with members of the black community. In fact, the consequences of the social, political and economic meanings of race are so deep that my co-author Mario Barnes and I have argued that whites who find themselves discriminated against based on racial proxies such as name (for example, Lakisha or Jamal), should have actionable race discrimination claims based on such conduct. In sum, the fact that race is a social construct, defined by markers such as skin color, hair texture, eye shape, ancestry, identity performance and even name, does not mean that racial classifications are free of consequence or tangible effects.

More than 50 years ago, Congress enacted the most comprehensive antidiscrimination legislation in history, the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Half a century later in 2015, the same gaps in racial inequality remain or have grown deeper. Today, the unemployment rate for African-Americans remains more than double that for whites, public schools are more segregated now than they were in the 1950s and young black males are 21 times more likely to be shot and killed by the police than their white male peers. Even a white fourth-grade teacher in Texas, Karen Fitzgibbons, openly advocated for the racial segregation of the 1950s and 1960s on her Facebook page.

Where will we be 50 years from now? Need I answer that question? It definitely won't be in a post-racial society.

Join Opinion on Facebook and follow updates on twitter.com/roomfordebate .

Topics: race

Why We Should Embrace the Racial Chaos

Racial Fluidity Complicates the Value of Race

How fluid is race, identity is your lived experience.

Race and Racial Identity Are Social Constructs

Hispanic and latino identity is changing.

Being Able to Negotiate Identity is Important

Related Discussions

Recent Discussions

Social Construction of Race in the United States Essay

Introduction, racialism in the usa, view of race in brazil, language affects, social construction, concluding remark.

Race, one of the significant inventions of 18th Century, categorizes people on the bases of some biological traits. Moreover, it is a social outlook that artificially divides people into different groups based on characteristics such as physical features (specifically skin color), personal characteristics, ancestral heritage, cultural affiliation, cultural history, ethnic classification, and “the social, economic and political needs of a society at a given period of time” (UC Davis, December, 2003).

Racial outlook in US focuses on the white-nonwhite dichotomy till 1967 there were prohibitions on marriages and sexual relation between a man and a woman of different races. The one drop rule (one drop of black blood makes someone black) let white people consider themselves eligible to “pass” as white when there arises questions of black people. But the present condition exposes a view that new immigrant groups have been successful to be White.

Skin color determines courses of racism in Brazil. In terms of class and status Brazilian system of racism is practiced. The proper observation of the practice of racism arises the question that how race gets constructed in classrooms when status and social class standard determines racism. Any inquiry led among the teachers will simply show that taking a student into account is categorized by “color prejudice” though teachers claim that individually they are away from this outlook as they often say, “For me, it doesn’t exist” (Barlett , p.8).

Student to student interactions also often shows prevalent state of racism. A racist acts in the classroom, e.g. nicknaming, by addressing a teacher or a student “”burnt ember,” “devil,” or “vulture.” Though occurred in a playful, joking manner creates an even greater problem and difficulty for the person being addressed, because if s/he takes the “joke” too seriously then that person is marginalized on socialatand point. So Brazilians who are darker in color are often forced to cooperate even under this type of discrimination without any argument. Again, speech and literacy shame unlike in the US darker people in Brazil experience speech as racialized, as a student in an NGO adult literacy class speaks out:

“I used to be ashamed to enter places. For example, if there was a party, I wouldn’t go, because I thought since I was black I couldn’t mix with whites.… For us, being black, and not knowing how to speak, and not knowing how to read you are isolated. Because you don’t know how to speak, other people don’t attention to you, because you don’t know how… to converse with people.” (Barlett , p.8)

Furthermore, Speech and literacy shame are not limited to race; while speaking, people sharply remain aware of their race, class, gender, rural/urban origin, regional origin, and other driving forces that affect the reception of their speech. It is also observed that a student has who has been ignored by his/her respective teacher has got dropped out of his school after such experience that address to them was associated with the varied consideration of being a whiter or wealthier South and Southeast. The worst case can be like a teacher is reinforcing literacy and speech shame by forcing students to read aloud and correcting them publicly. “Lack of recognition of connections between language” (Barlett, p.9) and power thus complicates any positive racial identification.

That race is a social construction does not mean denial of the obvious differences in skin color and physical characteristics that people normally manifest; rather, these physical differences should be understood as “an assortment of differences on a continuum of diverse physical possibilities rather than as reflecting the presence of innate genetic differences among people” (Fitchue, 1998, p.3). Different goals and objects come into the “play” when race is in talk about social experiences, identities or statuses (Otieno, July 07).

Race is a phenomenon as such is scientifically flawed and politically compromised. Some concludes that if race is socially constructed, it is an illusion that does not have any real existence. Again, it is an idea that the race is “a diffuse, massive, socially constructed social fact with real consequences in people’s lives”. Moreover, for the use of Omi and Winant’s famous formulation (1986:68)” (Otieno, July 07).… an unstable and ‘de-centered’ complex of social meanings constantly being transformed by political struggle ” (Otieno, July 07).

No single characteristic is ever found that shows the exclusive belonging to individuals in one racial group and not to any individuals in another racial group. Scientific status or the biological difference helps a scientist consider racism or race as something constructed by biological issues. This also often agrees race is biologically based prevalent in society, determining traits and abilities. Rockquemore and Brunsma (2002) write “racial identity is malleable, rooted in both macro and micro social processes, and that it has structurally and culturally defined parameters” (Shih, et.al., 2007).

A heightened awareness of race as social construction among multiracial individuals arises from the unique experiences as multiracial individuals often encounter during their upbringing (Shih, 2007, p.126). These experiences of multiracial individuals can bring into consideration when they are “grappling with issues surrounding their racial identity” (Shih, et.al., 2007, p.126). Viewing race as a social construction lets race to be less informative about an Individuals’ innate characteristics and traits, more likely to identify less strongly with their racial identity. Although, unidentification and viewing race as a social construction likely to be closely related, are not the similar of construction.

One can easily unidentify himself from an identity without believing that the identity is a social construction. Many of these experiences questions on racial differences. For instance, multiracial individuals encounter the home directions directly contradicting to the messages sent by the society barrierring between racial groups and the inescapable and inevitable nature of racial conflicts. Emphasizing race as a social construction and the de-emphasis of the biological basis of race can diminish the impact of race-based stereotypes (Shih, et.al., 2007, p.126).

When race is a social construction to an African American man, he identifies strongly himself with his race because he finds himself that his race affects his experiences in his social context. That is why, rejection of the biological basis of race can lessen one’s identification with the stereotyped identity. It has often been seen by the multiracial individuals that they are more likely to emphasize the social construction of race and this emphasis reduces vulnerability to racial stereotypes. Biological differences, e.g. skin colour; hair colour and texture; and eye, nose and lip shapes were thought to reflect distinctive biological and behavioral differences between people. Recent findings in genetics reject the scientific evolution of the concept of race.

“Advances in DNA research in the last 20 years demonstrate that, on average, 99.9 percent of the genetic features of humans are the same; of the remaining percentage that accounts for variation, differences within groups are larger than between groups; only six genes out of at least 100,000 that make up the human genome account for differences in skin colour; variations in colour are not discrete, but are distributed along a continuum, which reflects different levels of melanin in the skin; and many physical differences are due to environmental adaptations” (UNRISD, 2001). Racial ideas often influence discourses on “social integration or accommodation, encourage insular or xenophobic practices, and distort perceptions about rights and citizenship” (UNRISD, 2001).

It is suggested that education and encouraging people to be thoughtful about issues of race may be an important tool in the fight against the negative consequences of racism and prejudice. Government of every respective countries should assure effective protection and remedies against any acts created beceuse of racial discrimination. Organizing and mobilizing education and information relevant to the protection of all human rights can promot the issuses related to racism (Otieno, July 2007).

Article 12 of the Declaration on the Prevention of Genocide, adopted on 11 March 2005 by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), “urges the international community to look at the need for a comprehensive understanding of the dimensions of genocide, including in the context of situations where economic globalization adversely affects disadvantaged communities, in particular indigenous peoples” (Otieno, July 07). Lack of effective enforcement of laws should be removed. States must prohibit racial discrimination and enact laws in order to protect citizens as it is clear that genocidal activities can be linked to the Government’s violations of human rights.

Bartlett, Lesley. (2002). How Schools Mediate the Social Construction of Race in Latin America. Policies and Reforms in Latin American Education Teachers College. Web.

Fitchue, M. Anthony. (1998). Alain LeRoy Locke on The Social Construction of Race. Third Annual National Conference (1998). People of Color in Predominantly White Institutions. University of Nebraska – Lincoln. Web.

Otieno, Alex. (07). Eliminating Racial Discrimination: The Challenges of Prevention and Enforcement of Prohibition. The Soliderity of People. 3132 TS Vol. 35. Web.

Shih, Margaret. et. al., (2007). The Social Construction of Race: Biracial Identity and Vulnerability to Stereotypes. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. the American Psychological Association. Vol. 13, No. 2, 125–133. Web.

UC Davis. (2003). The Principles of Community. Web.

UNRISD, (2001). The Social Construction of Race and Citizenship. Racism and Public Policy Conference. Durban, South Africa. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, August 17). Social Construction of Race in the United States. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-construction-of-race-in-the-united-states/

"Social Construction of Race in the United States." IvyPanda , 17 Aug. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/social-construction-of-race-in-the-united-states/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Social Construction of Race in the United States'. 17 August.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Social Construction of Race in the United States." August 17, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-construction-of-race-in-the-united-states/.

1. IvyPanda . "Social Construction of Race in the United States." August 17, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-construction-of-race-in-the-united-states/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Social Construction of Race in the United States." August 17, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-construction-of-race-in-the-united-states/.

- Multiracial Categorization of Ambiguous Group Members

- Marked Language in Multiracial Youth

- Multiracial Issues in Modern Society

- Race Relations Between the U.S.A. and Brazil

- Family Counseling: Resolving Conflict and Promoting Wellness

- American Urbanism: The Changing Face

- Biracial People in Modern Society

- Colour composition and Polarised Light

- Biological Determinism: Race, Nationality and the New Immigrant Working Class

- Destructive Shame: The Silent Struggle of Minority Groups

- Chicano Discrimination in Higher Education

- Racism and Ethnicity in Latin America

- Problem of Racism to Native Americans in Sport

- Race and Ethnicity in Three Pop Culture Artifacts

- Racial Discrimination in Song 'Strange Fruit'

Race and Ethnicity

Race as a social construction, we often hear that race is a social construction. but what does that mean.

Posted December 5, 2016 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Trevor Noah , host of The Daily Show , recently released an autobiography entitled Born a Crime : Stories from a South African Childhood . As a biracial man born and raised in South Africa, he shares fascinating insights into how we racially categorize people and the consequences of such categorization.

He recounts how, as the son of a Black mother and a White father, his biracial status put in him a middle ground, considered “inferior” by half of his family and “superior” by the other half. After all, in South Africa, there have historically existed many gradations of whiteness and blackness as social categories, each of which comes with different social standing.

For instance, Noah describes how his Black grandmother was much less severe with him relative to his Black cousins, given his privileged status as half-White. He also explains how under the apartheid system one’s racial category or status could change, both socially and legally.

This is in sharp contrast to how race is conceptualized in the US, where the “one-drop rule” has long dominated. Although American culture recognizes the biracial category, people are generally considered Black (and treated as such) if they have descended from any Black relatives to any degree. That is, even a “drop” of Black blood has rendered someone Black (but even this varies depending on whether the perceiver is White or Black, among other factors).

As such, even being 1/16th Black historically resulted in your categorization as Black. (Incidentally, the Nazis held similar views, where having Jewish ancestry, even in a distant sense, categorized one as Jewish).

This is known as hypodescent , a process whereby a biracial person is categorized fully or primarily in terms of the lower status (or disadvantaged) social group. The fact that status plays a role in social categorization clearly demonstrates that categorization (e.g., as White, as Black) is a social construction.

Yet when I talk about race in class, it becomes apparent that students grapple with the notion of race as a social construction. Some will say, “But I can see race. I can see that you’re White, that she is Asian, and that he is Black." Others, including those in the media, are suspicious of the notion of race as a social construction, fearing that such ideas represent a left-wing ploy. A trick. A trap.

But recognizing race as a social construction does not make race less “real." Marriages are social constructions, but they have serious legal, cultural, and interpersonal implications. Oftentimes the social aspect is what makes a phenomenon so central to our lives.

So what do we mean by social construction in the racial context? Rather than draw on scientific or philosophical discussions of race and essentialism, my goal here is to describe some concrete examples that might help to elucidate what is meant by race as social construction.

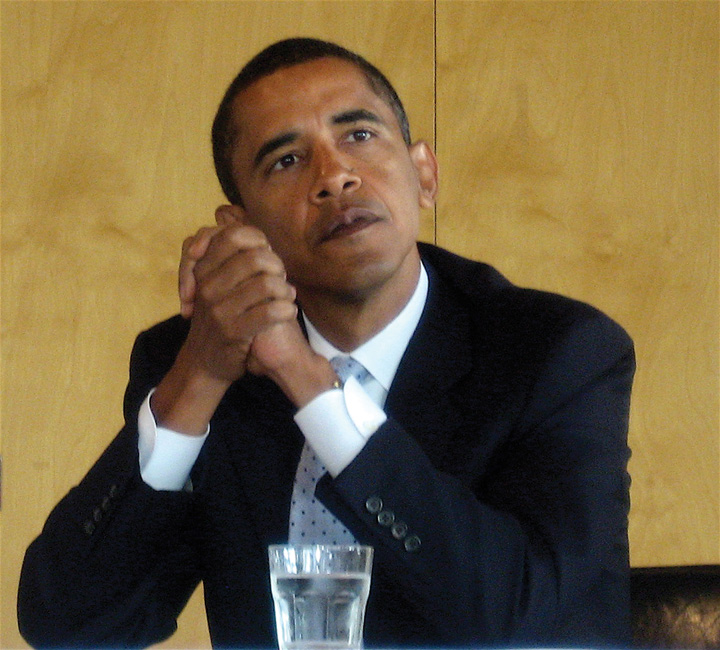

Let’s start with President Barack Obama. When he was running for president, we witnessed a range of responses from the voters and pundits. To some, he was clearly “too Black." For others, he was clearly “not Black enough." Even within social groups, there were disagreements. For some Black Americans he was not Black enough because he did not descend from slavery in an American context (i.e., his father moved from Kenya).

The fact that there exists disagreement, whether between Whites and Blacks, or within Whites and Blacks, drives home the point of this article: Race is a social construction with no true or absolute biological basis. If we can disagree about whether someone is of Race X or Y, and if there are consensual rules for determining such designations (e.g., based on social status, slave history), and if such a designation can change over time or across cultures (e.g., US vs. South Africa), then we are dealing with a social construct, not a biological one. As a society we develop cultural rules about race and then we apply these rules when psychologically categorizing people.

Need more convincing? Let’s turn to some interesting science. Kemmelmeier and Chavez (2014), using a variety of different methods across studies, exposed White participants to a range of photos of Barack Obama. Cleverly, the researchers darkened or lightened the photos systematically. The task of the participant was to identify which photo reflected Obama’s true skin colour.

In both studies, those higher in symbolic racism (i.e., feeling resentment toward Black demands for equality; denial of anti-Black discrimination ) selected the darker photos to reflect his true colour, and this was true both before and after each election cycle. Interestingly, those with stronger identification as a Republican supporter also perceived Obama’s skin to be significantly darker, but this latter effect was observed only prior to the election, not after the election.

Think about that for a minute. Political partisanship predicted “how Black” Obama is, but only in the context of a political race where a Black man might subsequently take or retain power of the White House. In the words of the authors, “… partisan biases in the perception of skin tone are activated as a function of political intergroup conflict” (p. 149).

Put simply, Obama’s “blackness” was systematically determined by racial biases of the perceiver, by the political partisanship of the perceiver, and by the temporal proximity of the testing session to an election. These patterns reflect the social construction of race. If Obama were Black or biracial simply as a matter of biological race, we would not see such patterns, whereby his degree of Blackness is a moving target and a topic of debate. Obama is who he is, but people categorize him as more or less Black as a function of their own psychological processing. When the target stands still but his categorization “as X” or “as Y” moves, there is a reasonable conclusion: Categorization is a social construction with psychological roots.

And let’s keep in mind some basic differences between cultures in how they think about race. In the US, one has historically been considered “Coloured” (although that term is becoming increasingly disavowed) to the extent that one has Black ancestry.

In South Africa, “Coloured” refers to someone of mixed White-Black background, not someone of a Black-only background. In South Africa, therefore, Black is Black and Coloured is mixed White-Black. Comparing these countries, it is clear that being “Black” (or not) varies as a function of social and cultural conventions, not biology.

Obama is widely considered as Black in the US, but as Coloured (and higher status) when he steps off of Air Force One in South Africa. Prior to becoming an international symbol and one of the world’s most powerful men, he would have also been treated very differently as a result of being Black (US) or Coloured (South Africa). Again, race is a social construction, where societies generate informal or formal rules about what we see (i.e., perception) and how to act and treat others (i.e., discrimination).

Scientists generally do not recognize races as biologically meaningful. Yet scientists, including me, discuss race and describe the racial composition of our samples.

To be clear, I am not advocating that we ignore race. In fact, there are many dangers in ignoring race as a social topic. Race is “real." But race is socially real, not biologically real.

Socially important categories can be very real and meaningful, but arguably nonetheless arbitrary in nature. From a Social Dominance Theory perspective, “the arbitrary-set system is filled with socially constructed and highly salient groups based on characteristics such as clan, ethnicity, estate, nation, race, caste, social class, religious sect, regional groups, or any other socially relevant group distinction that the human imagination is capable of constructing” (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999, p. 33).

Like race, nations are arbitrary but real. What we call Belgium is not biologically or essentially Belgium; what is called Belgium is a region that the international community agrees is Belgium. It is socially constructed. It might not have the same boundaries in the future, and it certainly did not in the past. This doesn’t make Belgium unreal. On the contrary, it has very real meaning and is of psychological, political, and legal significance. But humans created it as a concept. Belgium itself has no essence in a biological sense, and race works much the same way.

As I’ve argued, the degree to which a person is categorized into a racial category can vary as a function of the social context (e.g., power differentials between groups; temporal proximity to elections), personal factors (e.g., racism in the perceiver; political partisanship in the perceiver), or an interaction between personal and social factors. And how the person personally identifies is yet another valid factor to consider (as is the case with sexual identity , a topic I may revisit in a future column). All of this renders “race” a social construction. We make it, we agree on it, we reward and punish people as a result of it.

http://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-december-5-2016-1.38… (for a lengthy interview with Trevor Noah).

Ho, A.K., Sidanius, J., Levin, D.T., & Banaji, M.R. (2011). Evidence for hypodescent and racial hierarchy in the categorization and perception of biracial individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 492-506. DOI: 10.1037/a0021562

Kemmelmeier, M., & Chavez, H.L. (2014). Biases in the perception of Barack Obama’s skin tone. Analyses of Social Issues and Policies, 14, 137-161. DOI: 10.1111/asap.12061

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gordon Hodson, Ph.D. is a professor at Brock University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

The Impact of Race as a Social Construct

This essay about the constructed nature of race and its implications discusses how the concept, while often perceived as biologically rooted, is actually shaped by social, historical, and political forces. It highlights the documentary series “Race: The Power of an Illusion,” which reveals the lack of genetic basis for racial categories and traces the origins of racial thinking to justify inequalities. The essay explores the consequences of racial constructs, including disparities in education, healthcare, and justice, while acknowledging how these constructs also foster community and resistance against oppression. It argues for the importance of education in dismantling racial myths and promoting equity, emphasizing that recognizing race as a social construct is crucial for moving toward a more just and inclusive society. The essay underscores the need to view human diversity beyond the myths of racial difference, advocating for an approach that celebrates shared humanity and cultural richness.

How it works

The notion of ethnicity, often perceived as a biological determinant, is indeed a potent mirage sculpted by socio-cultural, historical, and political currents. This illusion, though abstract, yields tangible repercussions that pervade societies universally, molding perceptions, actions, and systemic frameworks. The documentary series “Ethnicity: The Potency of a Mirage” elucidates this intricate theme, uncovering how ethnicity has been fabricated and wielded to rationalize disparities and how its apparent authenticity impacts us collectively. This discourse probes the origins of ethnic constructs, their ramifications on civilization, and the imperative of deconstructing these divisive barriers.

Central to the issue is the realization that ethnicity lacks a genetic or empirical foundation. Historical testimony and genomic exploration attest that the diversities within purported ethnic cohorts are as consequential as those amidst them, dismantling the fallacy of discrete biological ethnicities. Nonetheless, the genesis of ethnicity as a concept served to legitimize imperial conquests, enslavement, and the subjugation of non-European populations by deeming them inherently inferior. Across epochs, these notions were enshrined into statutes and conventions, entrenching ethnic stratifications into societal tapestries.

The repercussions of ethnic constructs are profound and extensive. They have sculpted social dynamics, access to assets, and life prospects, frequently to the detriment of those categorized as belonging to particular ethnicities. Education, livelihood, healthcare, and legal systems evince stark disparities that often stem from ethnic biases and prejudice. Such imbalances are not innate but are the upshot of measures and norms that have systematically favored particular cohorts over others predicated on ethnicity.

The potency of the mirage of ethnicity also lies in its capacity to nurture identities and communities. While wielded as an instrument of disunion and oppression, the socio-cultural fabric of ethnicity has also facilitated the genesis of opulent cultural legacies, solidarity amidst marginalized factions, and endeavors for civil liberties and parity. The endeavor against ethnic injustice has precipitated momentous societal metamorphoses and strides toward parity, albeit the odyssey remains incomplete.

Acknowledging ethnicity as a socio-cultural construct constitutes the primary stride in disassembling its divisive potency. Education assumes a pivotal function in this endeavor, as it can elucidate the historical and societal origins of ethnicity, counter stereotypes, and foster comprehension and compassion amidst heterogeneous groups. Furthermore, policies aimed at redressing ethnic disparities must transcend colorblindness, which habitually disregards the lived experiences of prejudice, to actively disassemble systemic obstacles and foster equity.

In summation, “Ethnicity: The Potency of a Mirage” compels us to scrutinize and confront the entrenched preconceptions of ethnicity. By apprehending ethnicity as a mirage with substantive repercussions, we can commence disentangling the intricate fabric of social, economic, and political facets that perpetuate ethnic disparities. This awareness is indispensable for cultivating a more equitable and just civilization where individuals are not delimited by the capricious confines of ethnicity. As we progress, it is the shared humanity and the opulence of diverse heritages that ought to delineate our interactions, not the myths of ethnic disparity.

Cite this page

The Impact of Race as a Social Construct. (2024, Apr 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-race-as-a-social-construct/

"The Impact of Race as a Social Construct." PapersOwl.com , 1 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-race-as-a-social-construct/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Impact of Race as a Social Construct . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-race-as-a-social-construct/ [Accessed: 25 Apr. 2024]

"The Impact of Race as a Social Construct." PapersOwl.com, Apr 01, 2024. Accessed April 25, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-race-as-a-social-construct/

"The Impact of Race as a Social Construct," PapersOwl.com , 01-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-race-as-a-social-construct/. [Accessed: 25-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Impact of Race as a Social Construct . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-impact-of-race-as-a-social-construct/ [Accessed: 25-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.2 The Meaning of Race and Ethnicity

Learning objectives.

- Critique the biological concept of race.

- Discuss why race is a social construction.

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of a sense of ethnic identity.

To understand this problem further, we need to take a critical look at the very meaning of race and ethnicity in today’s society. These concepts may seem easy to define initially but are much more complex than their definitions suggest.

Let’s start first with race , which refers to a category of people who share certain inherited physical characteristics, such as skin color, facial features, and stature. A key question about race is whether it is more of a biological category or a social category. Most people think of race in biological terms, and for more than 300 years, or ever since white Europeans began colonizing populations of color elsewhere in the world, race has indeed served as the “premier source of human identity” (Smedley, 1998, p. 690).

It is certainly easy to see that people in the United States and around the world differ physically in some obvious ways. The most noticeable difference is skin tone: some groups of people have very dark skin, while others have very light skin. Other differences also exist. Some people have very curly hair, while others have very straight hair. Some have thin lips, while others have thick lips. Some groups of people tend to be relatively tall, while others tend to be relatively short. Using such physical differences as their criteria, scientists at one point identified as many as nine races: African, American Indian or Native American, Asian, Australian Aborigine, European (more commonly called “white”), Indian, Melanesian, Micronesian, and Polynesian (Smedley, 1998).

Although people certainly do differ in the many physical features that led to the development of such racial categories, anthropologists, sociologists, and many biologists question the value of these categories and thus the value of the biological concept of race (Smedley, 2007). For one thing, we often see more physical differences within a race than between races. For example, some people we call “white” (or European), such as those with Scandinavian backgrounds, have very light skins, while others, such as those from some Eastern European backgrounds, have much darker skins. In fact, some “whites” have darker skin than some “blacks,” or African Americans. Some whites have very straight hair, while others have very curly hair; some have blonde hair and blue eyes, while others have dark hair and brown eyes. Because of interracial reproduction going back to the days of slavery, African Americans also differ in the darkness of their skin and in other physical characteristics. In fact it is estimated that about 80% of African Americans have some white (i.e., European) ancestry; 50% of Mexican Americans have European or Native American ancestry; and 20% of whites have African or Native American ancestry. If clear racial differences ever existed hundreds or thousands of years ago (and many scientists doubt such differences ever existed), in today’s world these differences have become increasingly blurred.

Another reason to question the biological concept of race is that an individual or a group of individuals is often assigned to a race on arbitrary or even illogical grounds. A century ago, for example, Irish, Italians, and Eastern European Jews who left their homelands for a better life in the United States were not regarded as white once they reached the United States but rather as a different, inferior (if unnamed) race (Painter, 2010). The belief in their inferiority helped justify the harsh treatment they suffered in their new country. Today, of course, we call people from all three backgrounds white or European.

In this context, consider someone in the United States who has a white parent and a black parent. What race is this person? American society usually calls this person black or African American, and the person may adopt the same identity (as does Barack Obama, who had a white mother and African father). But where is the logic for doing so? This person, as well as President Obama, is as much white as black in terms of parental ancestry. Or consider someone with one white parent and another parent who is the child of one black parent and one white parent. This person thus has three white grandparents and one black grandparent. Even though this person’s ancestry is thus 75% white and 25% black, she or he is likely to be considered black in the United States and may well adopt this racial identity. This practice reflects the traditional “one-drop rule” in the United States that defines someone as black if she or he has at least one drop of “black blood,” and that was used in the antebellum South to keep the slave population as large as possible (Wright, 1993). Yet in many Latin American nations, this person would be considered white. In Brazil, the term black is reserved for someone with no European (white) ancestry at all. If we followed this practice in the United States, about 80% of the people we call “black” would now be called “white.” With such arbitrary designations, race is more of a social category than a biological one.

President Barack Obama had an African father and a white mother. Although his ancestry is equally black and white, Obama considers himself an African American, as do most Americans. In several Latin American nations, however, Obama would be considered white because of his white ancestry.

Steve Jurvetson – Barack Obama on the Primary – CC BY 2.0.

A third reason to question the biological concept of race comes from the field of biology itself and more specifically from the studies of genetics and human evolution. Starting with genetics, people from different races are more than 99.9% the same in their DNA (Begley, 2008). To turn that around, less than 0.1% of all the DNA in our bodies accounts for the physical differences among people that we associate with racial differences. In terms of DNA, then, people with different racial backgrounds are much, much more similar than dissimilar.

Even if we acknowledge that people differ in the physical characteristics we associate with race, modern evolutionary evidence reminds us that we are all, really, of one human race. According to evolutionary theory, the human race began thousands and thousands of years ago in sub-Saharan Africa. As people migrated around the world over the millennia, natural selection took over. It favored dark skin for people living in hot, sunny climates (i.e., near the equator), because the heavy amounts of melanin that produce dark skin protect against severe sunburn, cancer, and other problems. By the same token, natural selection favored light skin for people who migrated farther from the equator to cooler, less sunny climates, because dark skins there would have interfered with the production of vitamin D (Stone & Lurquin, 2007). Evolutionary evidence thus reinforces the common humanity of people who differ in the rather superficial ways associated with their appearances: we are one human species composed of people who happen to look different.

Race as a Social Construction

The reasons for doubting the biological basis for racial categories suggest that race is more of a social category than a biological one. Another way to say this is that race is a social construction , a concept that has no objective reality but rather is what people decide it is (Berger & Luckmann, 1963). In this view race has no real existence other than what and how people think of it.

This understanding of race is reflected in the problems, outlined earlier, in placing people with multiracial backgrounds into any one racial category. We have already mentioned the example of President Obama. As another example, the famous (and now notorious) golfer Tiger Woods was typically called an African American by the news media when he burst onto the golfing scene in the late 1990s, but in fact his ancestry is one-half Asian (divided evenly between Chinese and Thai), one-quarter white, one-eighth Native American, and only one-eighth African American (Leland & Beals, 1997).

Historical examples of attempts to place people in racial categories further underscore the social constructionism of race. In the South during the time of slavery, the skin tone of slaves lightened over the years as babies were born from the union, often in the form of rape, of slave owners and other whites with slaves. As it became difficult to tell who was “black” and who was not, many court battles over people’s racial identity occurred. People who were accused of having black ancestry would go to court to prove they were white in order to avoid enslavement or other problems (Staples, 1998). Litigation over race continued long past the days of slavery. In a relatively recent example, Susie Guillory Phipps sued the Louisiana Bureau of Vital Records in the early 1980s to change her official race to white. Phipps was descended from a slave owner and a slave and thereafter had only white ancestors. Despite this fact, she was called “black” on her birth certificate because of a state law, echoing the “one-drop rule,” that designated people as black if their ancestry was at least 1/32 black (meaning one of their great-great-great grandparents was black). Phipps had always thought of herself as white and was surprised after seeing a copy of her birth certificate to discover she was officially black because she had one black ancestor about 150 years earlier. She lost her case, and the U.S. Supreme Court later refused to review it (Omi & Winant, 1994).

Although race is a social construction, it is also true, as noted in an earlier chapter, that things perceived as real are real in their consequences. Because people do perceive race as something real, it has real consequences. Even though so little of DNA accounts for the physical differences we associate with racial differences, that low amount leads us not only to classify people into different races but to treat them differently—and, more to the point, unequally—based on their classification. Yet modern evidence shows there is little, if any, scientific basis for the racial classification that is the source of so much inequality.

Because of the problems in the meaning of race , many social scientists prefer the term ethnicity in speaking of people of color and others with distinctive cultural heritages. In this context, ethnicity refers to the shared social, cultural, and historical experiences, stemming from common national or regional backgrounds, that make subgroups of a population different from one another. Similarly, an ethnic group is a subgroup of a population with a set of shared social, cultural, and historical experiences; with relatively distinctive beliefs, values, and behaviors; and with some sense of identity of belonging to the subgroup. So conceived, the terms ethnicity and ethnic group avoid the biological connotations of the terms race and racial group and the biological differences these terms imply. At the same time, the importance we attach to ethnicity illustrates that it, too, is in many ways a social construction, and our ethnic membership thus has important consequences for how we are treated.

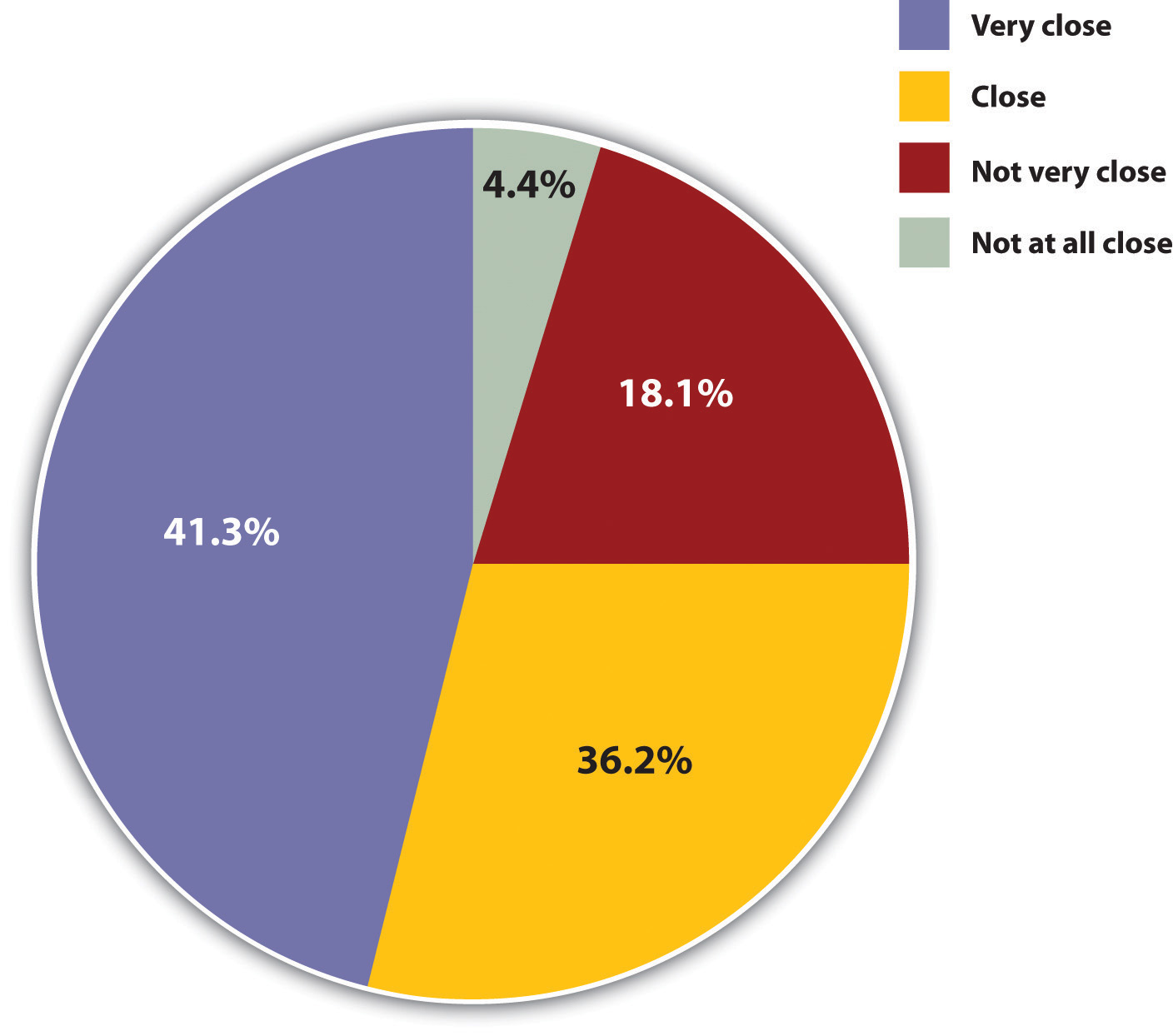

The sense of identity many people gain from belonging to an ethnic group is important for reasons both good and bad. Because, as we learned in Chapter 6 “Groups and Organizations” , one of the most important functions of groups is the identity they give us, ethnic identities can give individuals a sense of belonging and a recognition of the importance of their cultural backgrounds. This sense of belonging is illustrated in Figure 10.1 “Responses to “How Close Do You Feel to Your Ethnic or Racial Group?”” , which depicts the answers of General Social Survey respondents to the question, “How close do you feel to your ethnic or racial group?” More than three-fourths said they feel close or very close. The term ethnic pride captures the sense of self-worth that many people derive from their ethnic backgrounds. More generally, if group membership is important for many ways in which members of the group are socialized, ethnicity certainly plays an important role in the socialization of millions of people in the United States and elsewhere in the world today.

Figure 10.1 Responses to “How Close Do You Feel to Your Ethnic or Racial Group?”

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2004.

A downside of ethnicity and ethnic group membership is the conflict they create among people of different ethnic groups. History and current practice indicate that it is easy to become prejudiced against people with different ethnicities from our own. Much of the rest of this chapter looks at the prejudice and discrimination operating today in the United States against people whose ethnicity is not white and European. Around the world today, ethnic conflict continues to rear its ugly head. The 1990s and 2000s were filled with “ethnic cleansing” and pitched battles among ethnic groups in Eastern Europe, Africa, and elsewhere. Our ethnic heritages shape us in many ways and fill many of us with pride, but they also are the source of much conflict, prejudice, and even hatred, as the hate crime story that began this chapter so sadly reminds us.

Key Takeaways

- Sociologists think race is best considered a social construction rather than a biological category.

- “Ethnicity” and “ethnic” avoid the biological connotations of “race” and “racial.”

For Your Review

- List everyone you might know whose ancestry is biracial or multiracial. What do these individuals consider themselves to be?

- List two or three examples that indicate race is a social construction rather than a biological category.

Begley, S. (2008, February 29). Race and DNA. Newsweek . Retrieved from http://www.newsweek.com/blogs/lab-notes/2008/02/29/race-and-dna.html .

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1963). The social construction of reality . New York, NY: Doubleday.

Leland, J., & Beals, G. (1997, May 5). In living colors: Tiger Woods is the exception that rules. Newsweek 58–60.

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (1994). Racial formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Painter, N. I. (2010). The history of white people . New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Smedley, A. (1998). “Race” and the construction of human identity. American Anthropologist, 100 , 690–702.

Staples, B. (1998, November 13). The shifting meanings of “black” and “white,” The New York Times , p. WK14.

Stone, L., & Lurquin, P. F. (2007). Genes, culture, and human evolution: A synthesis . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Wright, L. (1993, July 12). One drop of blood. The New Yorker, pp. 46–54.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

The Social Construction of Racism in the United States

by Coleman Hughes

In the 1980s, people all around America became convinced that day care centers were secretly practicing demonic ritual sex abuse on children. These allegations stayed in the national news for the better part of a decade. Hapless day care workers were falsely convicted of running sex rings. Evidence of their guilt was manufactured as necessary. In hindsight, this episode looks absurd. How could anyone have believed that there were Satanic day care centers throughout the country? Yet at the time, many reasonable people were swept up in the delusion—as were the prosecutors and elected officials who promised to put a stop to the fake problem. Such is the nature of moral panics. What looks like obvious absurdity from the outside seems totally reasonable to those on the inside.

Some moral panics are mysterious in origin. Others are the product of specific ideas. Since about 2014, we have been facing a new moral panic surrounding race, gender, and sexuality. Unlike Satanic day cares, this one is not a complete fabrication. Bigotry is real. Yet the public perception of bigotry has surpassed the reality to such an extent that it has become a moral panic. White supremacy is said to be rampant. Black people should fear for their lives when going for a jog, one New York Times op-ed argued.

Yet as political scientist Eric Kaufmann lays out in this paper, the public has a mistaken perception of how much racism exists in America today. This misperception is not only driven by cognitive biases such as the availability heuristic, it is also driven by ideas. Critical race theory and intersectionality—formerly confined to graduate seminars—have seeped into corporate America and Silicon Valley, as well as into many K–12 education systems. With their spread has come an increase in the misperception that bigotry is everywhere, even as the data tell a different story: racism exists, but there has never been less racism than there is now.

If America’s racial tensions ever heal, it will be because we were able to align our perceptions with our reality and leave moral panics at the door.

Executive Summary

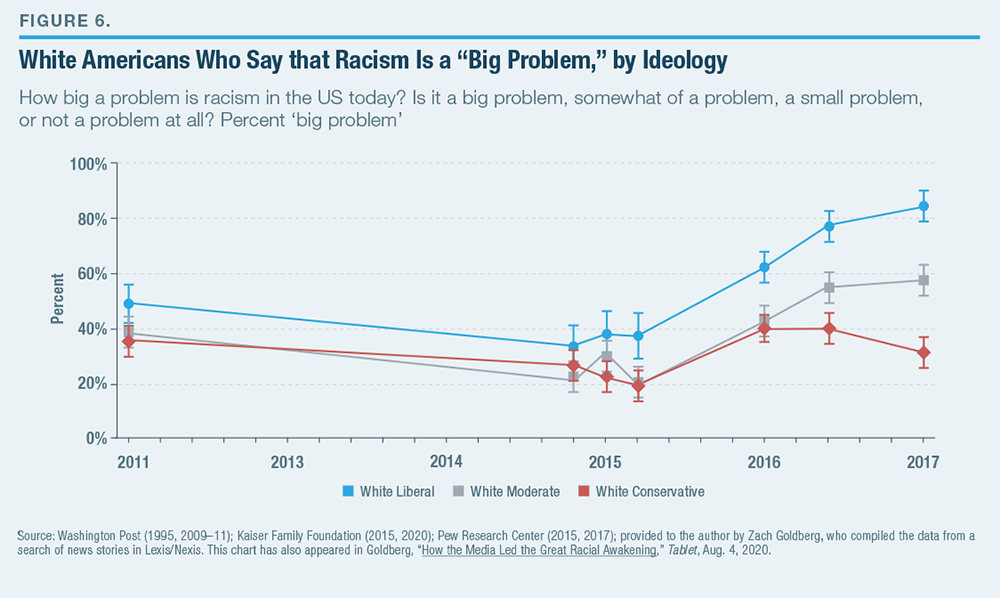

This paper begins with a version of Tocqueville’s paradox:[ 1 ] at a time when measures of racist attitudes and behavior have never been more positive, pessimism about racism and race relations has increased in America.

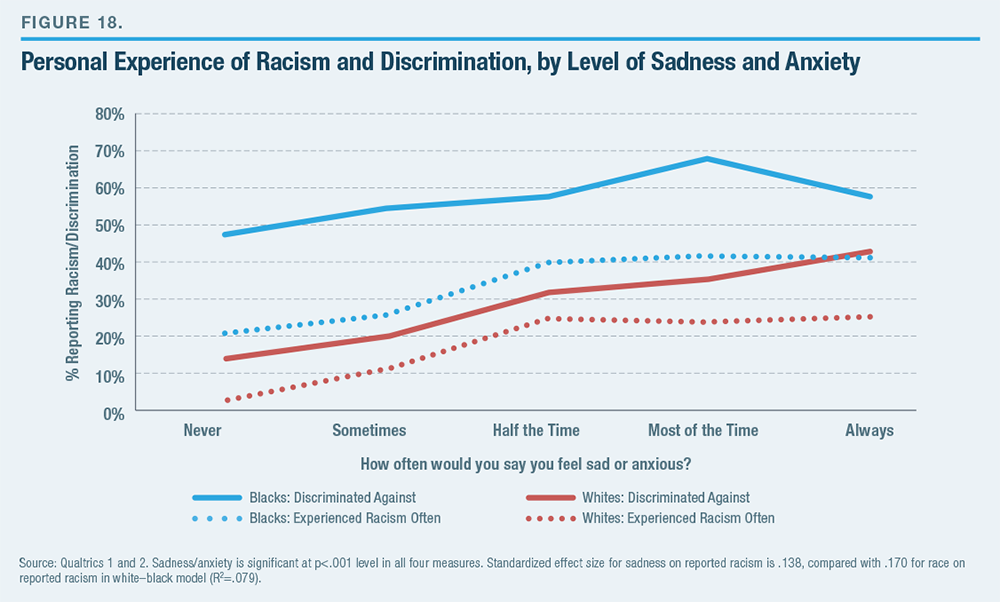

Why? An analysis of a wide variety of data sources, including several new surveys that I conducted, suggests that the paradox is best explained by changes in perceptions of racism rather than an increase in the frequency of racist incidents. That is, ideology, partisanship, social media, and education have inclined Americans to “see” more bigotry and more racial prejudice than they previously did. This is true not only regarding the level of racism in society but even of their personal experiences. My survey findings suggest that an important part of the reported experience of racism is ideologically malleable. Reports of increased levels of racism during the Trump era, for example, likely reflect perception rather than reality—just as people have almost always reported rising violent crime when it has been declining during most of the past 25 years. In addition, people who say that they are sad or anxious at least half the time, whether white or black, are about twice as likely as others to say that they have experienced racism and discrimination.

None of this means that racism is an imaginary problem. However, efforts to reduce it should be based on strong empirical evidence and bias-free measures. The risks of overlooking racism are clear: injustice is permitted to persist and grow. Yet there are also clear dangers in overstating its presence. These go well beyond majority resentment and polarization. A media-generated narrative about systemic racism distorts people’s perceptions of reality and may even damage African-Americans’ sense of control over their lives.

Key Findings Include:

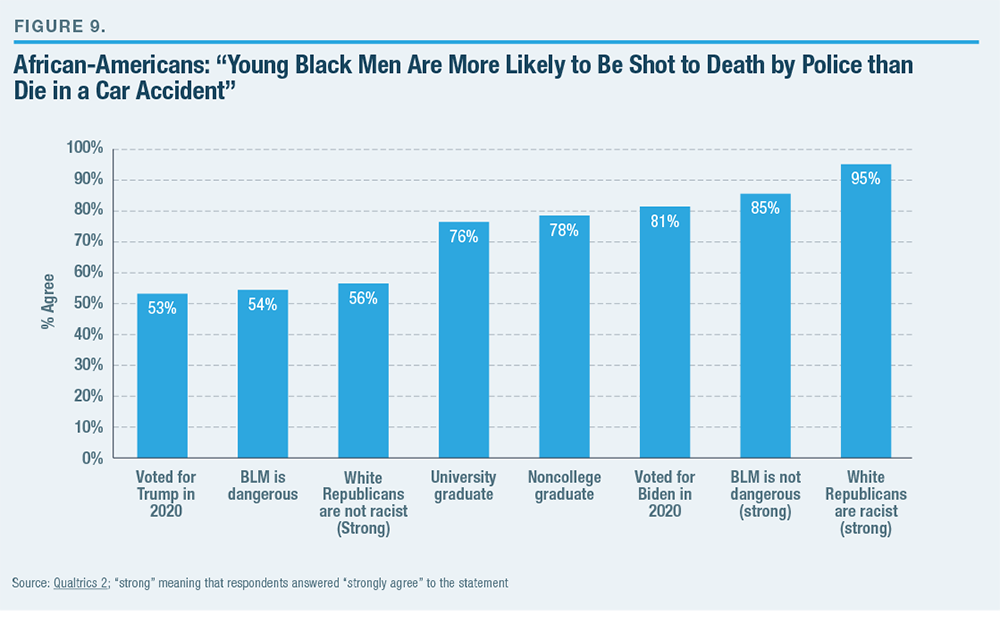

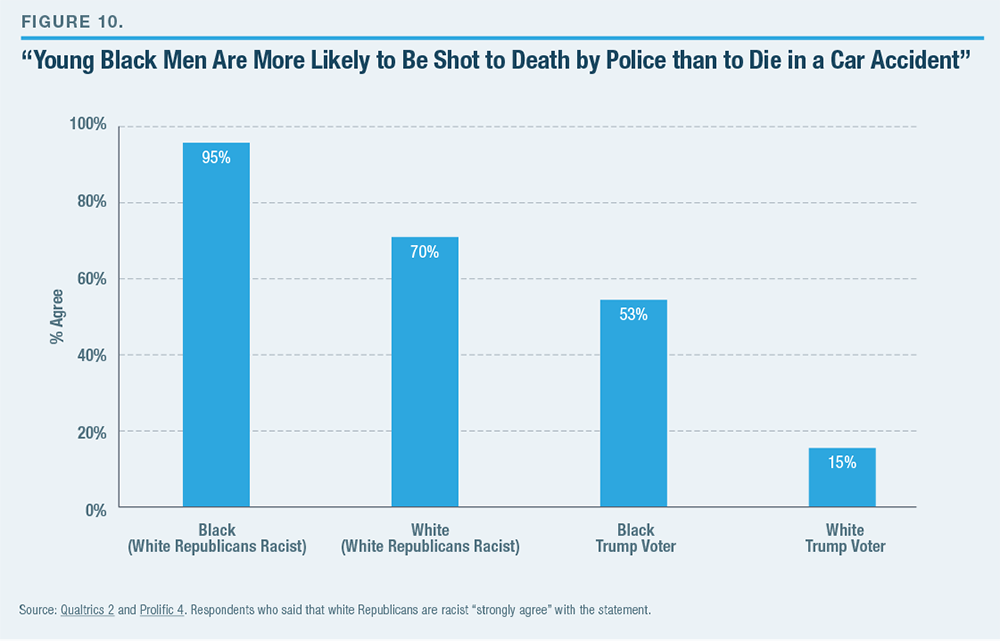

- Eight in 10 African-American survey respondents believe that young black men are more likely to be shot to death by the police than to die in a traffic accident; one in 10 disagrees. Among a highly educated sample of liberal whites, more than six in 10 agreed. In reality, considerably more young African-American men die in car accidents than are shot to death by police.

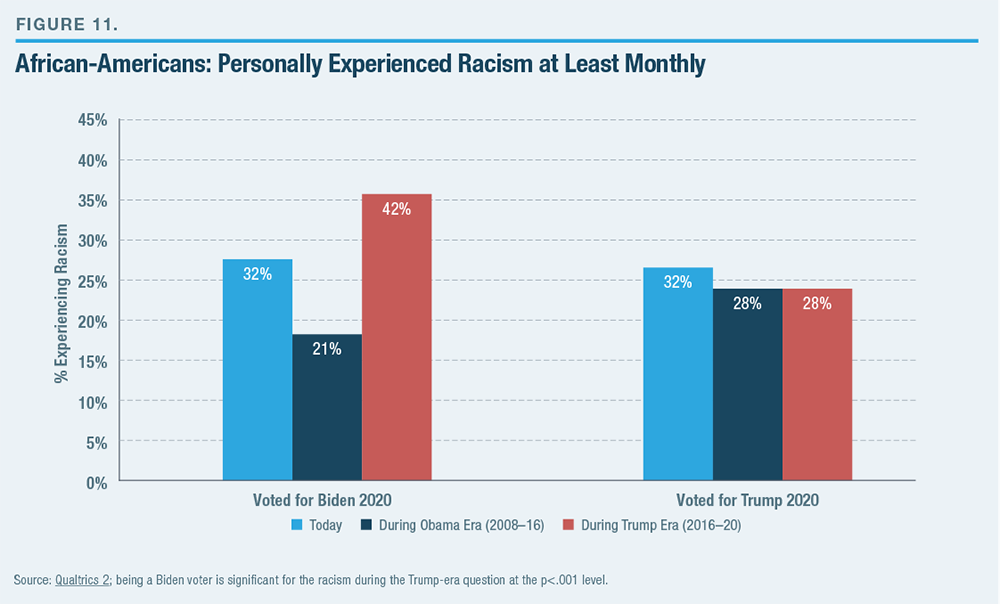

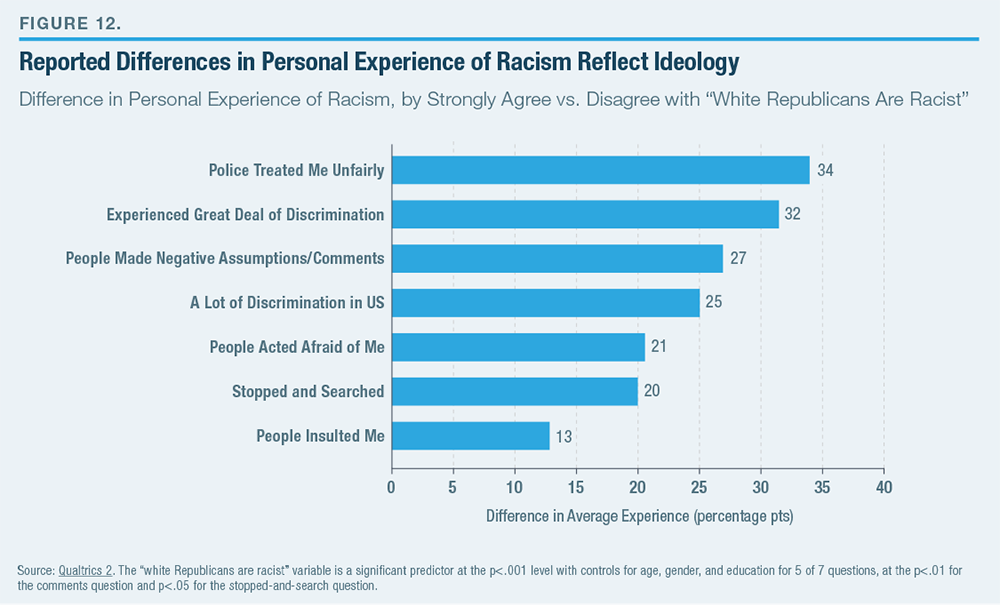

- Black Biden voters are twice as likely as black Trump voters to say that they personally experienced more racism under Trump than under Obama. Black Trump voters reported a consistent level of racism under both administrations. Black respondents who strongly agree that white Republicans are racist are 20–30 points more likely to say that they experience various personal forms of racism than African-Americans who strongly disagree that white Republicans are racist.

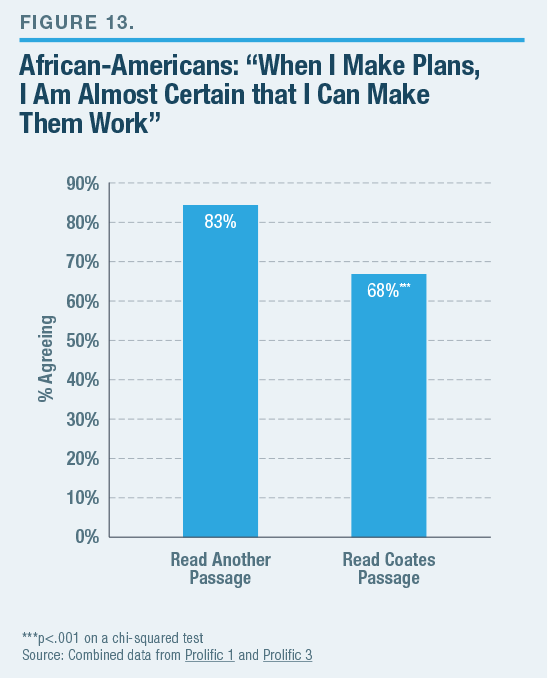

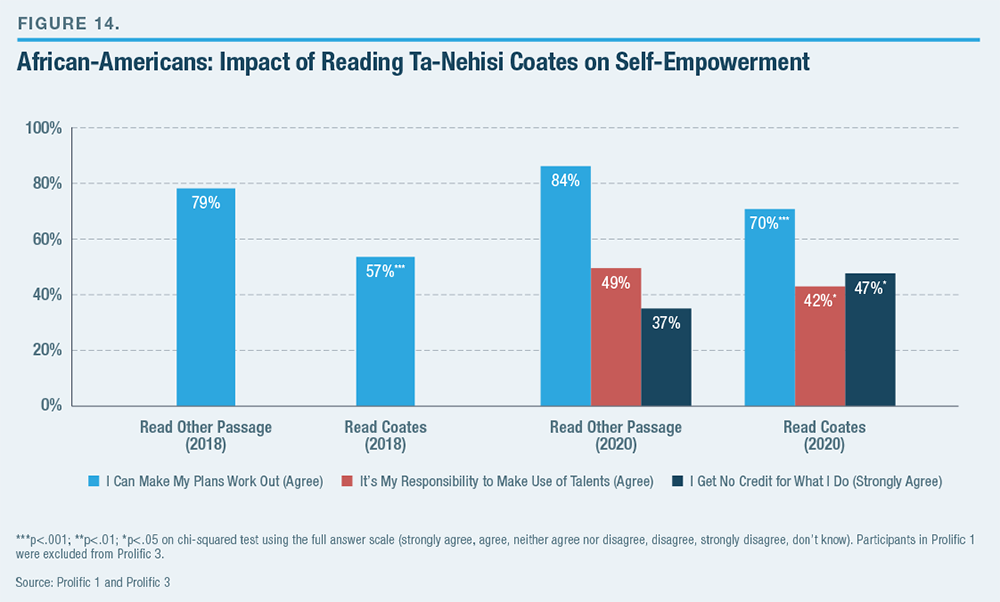

- Reading a passage from critical race theory author Ta-Nehisi Coates results in a significant 15-point drop in black respondents’ belief that they have control over their lives.

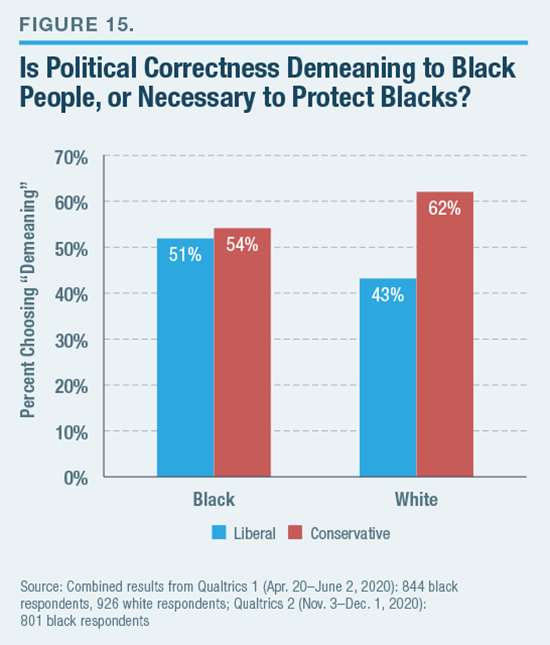

- A slight majority of African-Americans and whites overall felt that political correctness on race is demeaning to black people rather than necessary to protect them. Among blacks, the difference between liberals and conservatives was 3 points (51% of the liberals thought it was demeaning vs. 54% of the conservatives). Among whites, however, there was a nearly 20-point divide between liberals and conservatives (43% of the liberals thought it was demeaning vs. 62% of the conservatives).

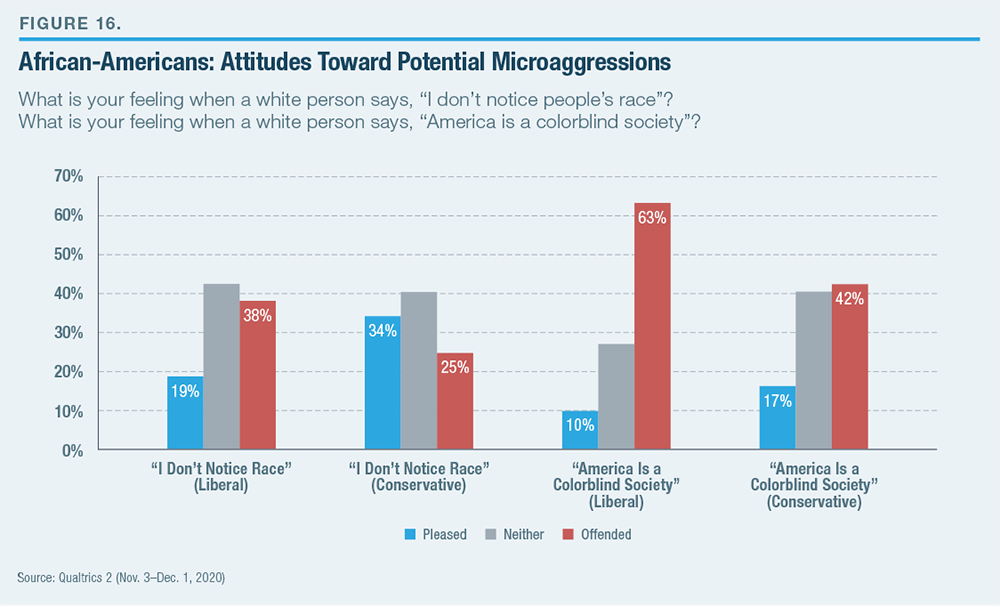

- Liberal African-Americans with a college degree are nearly 30 points more likely to find a statement by a white person such as “I don’t notice people’s race” or “America is a colorblind society” offensive than African-Americans without degrees who identify as conservative. Among whites, the gap between liberals and conservatives is 50 points.

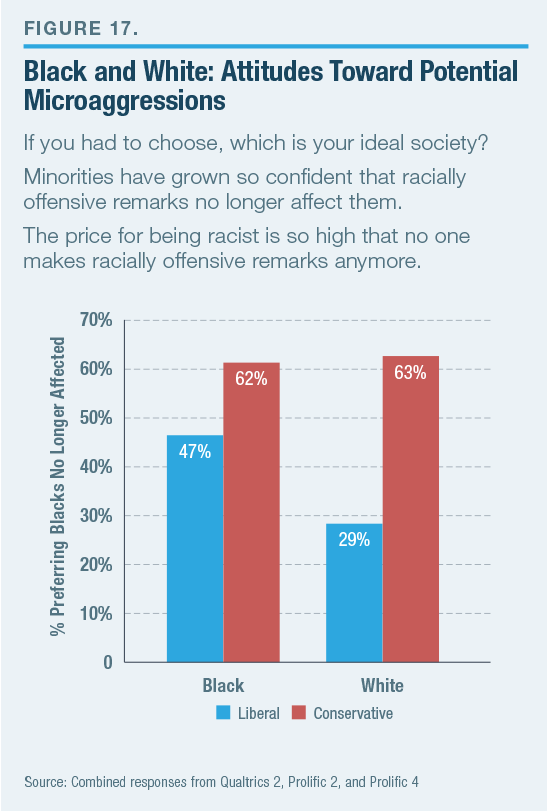

- When asked to choose between a future in which racially offensive remarks were so heavily punished as to be nonexistent and one where minorities were so confident that they no longer felt concerned about racial insults, black respondents overall preferred, by a 53%–47% margin, the resilience option. White liberals preferred the punitive option, by a 71%–29% margin; black liberals chose the second option by just 6 points, 53%–47%.

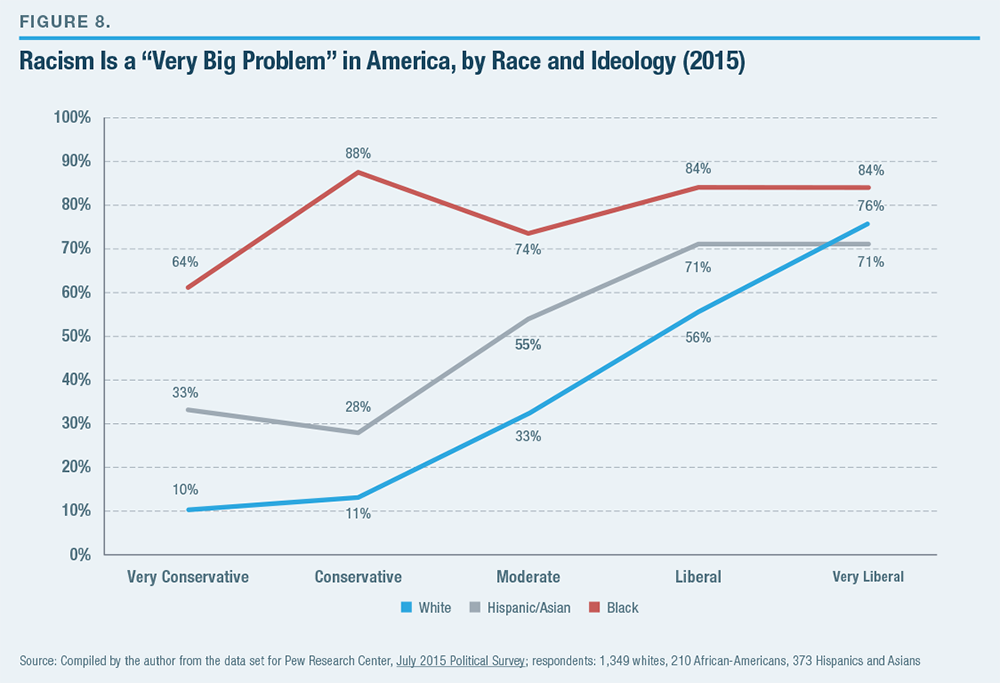

- In general, African-Americans’ opinion on race issues appears to be less affected by ideology and partisanship than white opinion. In a 2015 Pew survey, 20 points separated “very conservative” and “very liberal” African- Americans on whether racism is a very big problem. The gap between “very conservative” and “very liberal” whites was 65 points; the gap between “very conservative” and “very liberal” Hispanics and Asians was 40 points.

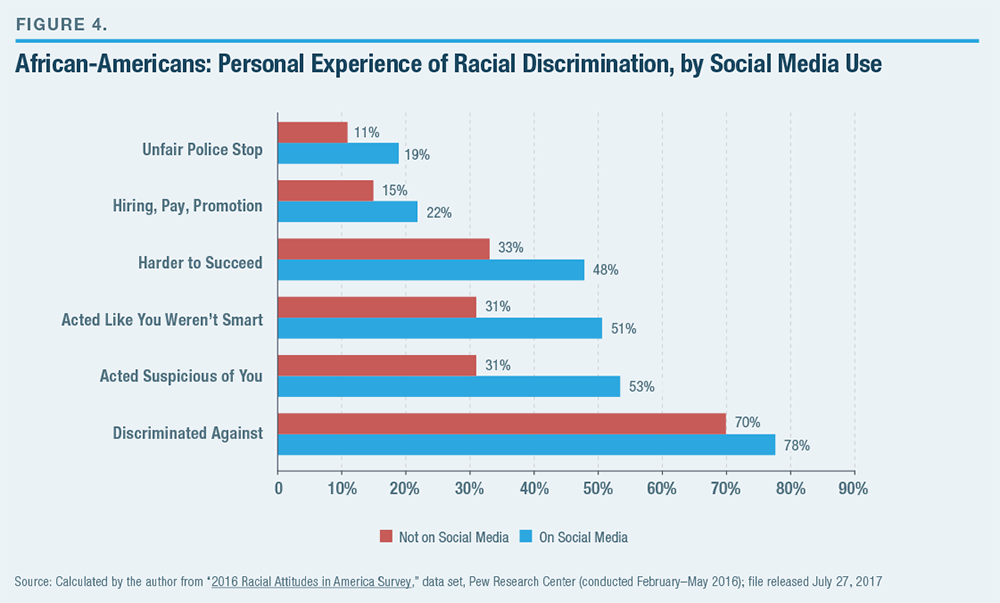

- Exposure to social media and other media appears to be related to survey respondents’ views of both the national prevalence of racism and their personal experience of it.

DOWNLOAD PDF

Introduction

Is racism real or is it, to some significant degree, socially constructed? While it is important to be skeptical of social scientists who overstate the malleability of categories like race, there is no question that perception does play a role in how people view social reality. This paper uses survey data to make the case that racism in America lies, in significant measure, in the eyes of the beholder. This not only concerns people’s perceptions of the prevalence of racism in society but even of their personal experience.

In their landmark work, The Social Construction of Reality , Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann argued that the dominant ideology in society shapes the way people think about the social world, defining roles, norms, and expectations. Ideology is central to the social constructionist argument, defining right and wrong, and what constitutes a violation of moral “reality”; that is, the norms and social facts everyone “knows” to be true (even if they are not based on objective truth).[ 2 ]

The dominant ideology in today’s cultural institutions is what I have elsewhere termed left-modernism, a hybrid worldview that applies socialist theories of conflict to identity categories first developed by liberalism.[ 3 ] From liberalism comes the idea that majorities are often tyrannical while racial, religious, gender, or sexual minorities require protection. From socialism comes the notion that society is best understood as a struggle between oppressive and oppressed groups. Freudianism, with its focus on the subjective, has also shaped left-modernism through its focus on psychological sensitivity, which has fused with left-modernism’s outlook to produce demands not only for material but for therapeutic equality and safety.

Religions typically concentrate on a handful of totemic issues. For example, conservative Christian politics has, over time, focused on causes such as restricting the sale of alcohol, the teaching of evolution, or the provision of abortion. Left-modernism is instead centered around a trinity of totemic categories: race, gender, and sexuality. Race stands at the apex of the system, producing what John McWhorter concludes is a religion of antiracism.[ 4 ] For Jonathan Haidt, the sacralization of race, sexuality, and gender lies at the heart of the progressive worldview.[ 5 ] This means that it becomes difficult to objectively assess the scientific validity of claims made about disadvantaged identity groups, lest one transgress the sacred values of the ideology and even be perceived as having committed an act of blasphemy.

Moreover, racism itself is not a fixed term. While expanding the range of phenomena covered by a term like racism can make sense in some circumstances, we are arguably well past that point.

Given the prevalence of left-modernism in the elite institutions of society—universities, much of the media, large corporations, and foundations—there has been considerable cultural distortion in the definition of racism. Psychologist Nick Haslam calls the expanding meaning of clinical terms “concept creep,” which applies also to concepts such as bullying, abuse, trauma, and mental disorder. Left-modernism’s therapeutic ethos, combined with the centrality of race in its pantheon of sacred values, helps explain this “conceptual stretching” of racism.[ 6 ] For the writer Coleman Hughes, expanding the meaning of racism is part of an ideological project that seeks to heighten minority threat perceptions to underpin claims of harm that can justify silencing.[ 7 ] The endpoint of this logic is to criminalize such dissent as “hate.”[ 8 ]

The Media and Public Perception of Racism

It is well known that the media, with their ability to frame events and social trends, have an impact on public opinion. This is especially the case when it comes to the visibility and political prominence of certain issues, what political scientists call issue “salience.” For example, there is a close relationship in Europe between media coverage of immigration and salience—the number of people saying that immigration is the most important issue facing their country.

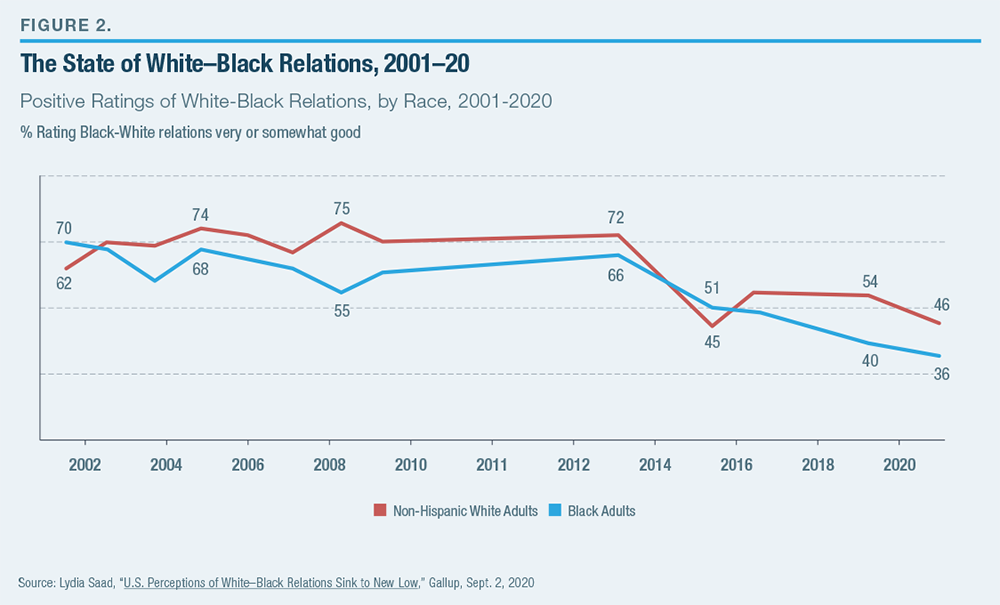

The same appears to be true for race. Gallup data show that the civil rights era of the 1950s and early 1960s, as well as the race riots in the late 1960s, saw the public salience of race spike ( Figure 1 ). The public salience of race then remained muted until 1992, when the Los Angeles riots, in the wake of Rodney King’s beating, sent questions of race to the top of 15% of the public’s priority lists. Since 2014, a series of events (including the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, after the shooting death of Michael Brown by a police officer; and the election of Donald Trump) pushed the race issue above 10% salience. In 2020, despite the Covid-19 pandemic, the George Floyd/Black Lives Matter protests elevated race back to the top spot: it was named as the leading concern by nearly 20% of the public in mid-June 2020. This was the highest salience level recorded for race since the late 1960s, eclipsing the Rodney King spike.

Media events affect the prominence of issues of race and racism in the public consciousness, but they also shape how people evaluate the quality of race relations. Other Gallup data show that during 2001–14, nearly 70% of Americans said that relations between whites and blacks were good. After the Ferguson protests, this fell to 47%, hovered in the low 50s between 2015 and 2019, and has since tumbled to 44% following the BLM protests ( Figure 2 ).

The Decline of Racist Attitudes

The increasing pessimism over race relations stands in contrast to the steady, long-term liberalization among white Americans across a range of racial attitudes measured in the leading General Social Survey (GSS) since 1972. In the 1970s, for example, nearly 60% of white Americans agreed with the statement that blacks shouldn’t “push themselves where they’re not wanted.” This response had declined to 20% by 2002, when the question was discontinued. The share of white Americans who agree that it is permissible to racially discriminate when selling a home declined from 60% as late as 1980 to 28% by 2012.[ 9 ]

For decades, American National Election Studies (ANES) posed a question of whether minorities/ blacks should help themselves or whether the government should help them more. There was a gradual rise in support for government assistance to blacks during 1970–2016 of about a half-point on a seven-point scale.[ 13 ] Meanwhile, police killings of African-Americans declined by 60%–80% from the late 1960s to the early 2000s and have remained at this level ever since.[ 14 ] Racist attitudes and behaviors have sharply declined, though the problem has not been eradicated.

The Racism Paradox

The increasingly sour national mood on race relations in the U.S. may likely be related to the higher salience of race since the 2014 Ferguson protests. While it is too early to be definitive, the emergence and rapid spread of social media may account for this. Combined with smartphone citizen journalism, social media mean that knowledge of white-police-on-black-suspect violence is more likely to circulate widely, where it can ignite riots and boost the salience of the race question. Thus, even as the number of such incidents is declining, each event is more likely to be captured alive and to possess a higher media multiplier effect.