21 Action Research Examples (In Education)

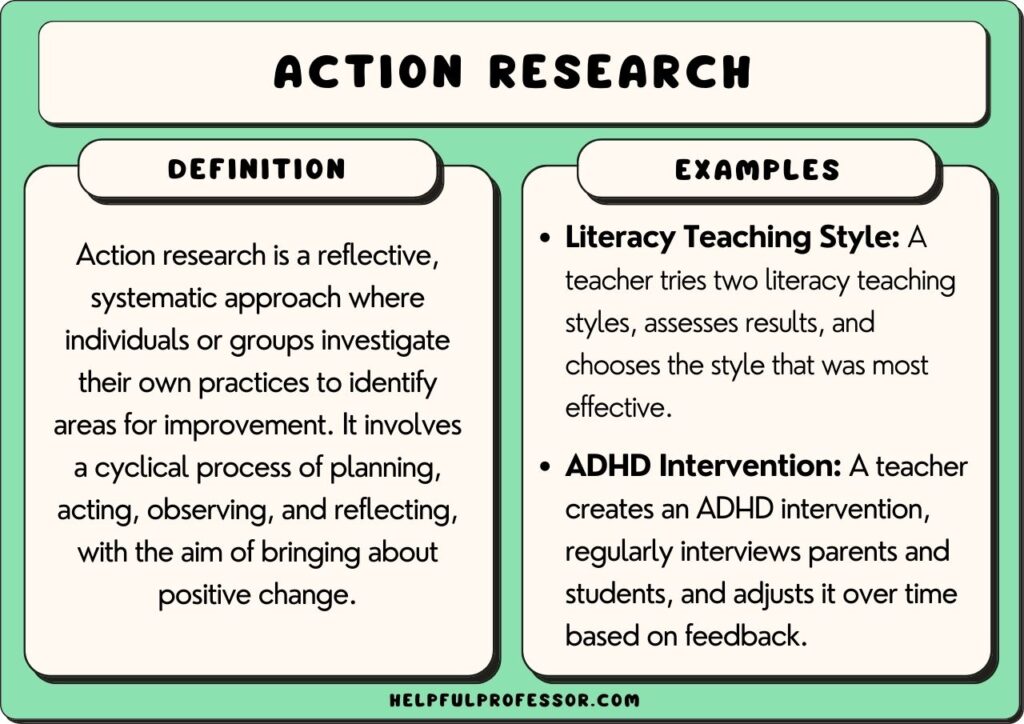

Action research is an example of qualitative research . It refers to a wide range of evaluative or investigative methods designed to analyze professional practices and take action for improvement.

Commonly used in education, those practices could be related to instructional methods, classroom practices, or school organizational matters.

The creation of action research is attributed to Kurt Lewin , a German-American psychologist also considered to be the father of social psychology.

Gillis and Jackson (2002) offer a very concise definition of action research: “systematic collection and analysis of data for the purpose of taking action and making change” (p.264).

The methods of action research in education include:

- conducting in-class observations

- taking field notes

- surveying or interviewing teachers, administrators, or parents

- using audio and video recordings.

The goal is to identify problematic issues, test possible solutions, or simply carry-out continuous improvement.

There are several steps in action research : identify a problem, design a plan to resolve, implement the plan, evaluate effectiveness, reflect on results, make necessary adjustment and repeat the process.

Action Research Examples

- Digital literacy assessment and training: The school’s IT department conducts a survey on students’ digital literacy skills. Based on the results, a tailored training program is designed for different age groups.

- Library resources utilization study: The school librarian tracks the frequency and type of books checked out by students. The data is then used to curate a more relevant collection and organize reading programs.

- Extracurricular activities and student well-being: A team of teachers and counselors assess the impact of extracurricular activities on student mental health through surveys and interviews. Adjustments are made based on findings.

- Parent-teacher communication channels: The school evaluates the effectiveness of current communication tools (e.g., newsletters, apps) between teachers and parents. Feedback is used to implement a more streamlined system.

- Homework load evaluation: Teachers across grade levels assess the amount and effectiveness of homework given. Adjustments are made to ensure a balance between academic rigor and student well-being.

- Classroom environment and learning: A group of teachers collaborates to study the impact of classroom layouts and decorations on student engagement and comprehension. Changes are made based on the findings.

- Student feedback on curriculum content: High school students are surveyed about the relevance and applicability of their current curriculum. The feedback is then used to make necessary curriculum adjustments.

- Teacher mentoring and support: New teachers are paired with experienced mentors. Both parties provide feedback on the effectiveness of the mentoring program, leading to continuous improvements.

- Assessment of school transportation: The school board evaluates the efficiency and safety of school buses through surveys with students and parents. Necessary changes are implemented based on the results.

- Cultural sensitivity training: After conducting a survey on students’ cultural backgrounds and experiences, the school organizes workshops for teachers to promote a more inclusive classroom environment.

- Environmental initiatives and student involvement: The school’s eco-club assesses the school’s carbon footprint and waste management. They then collaborate with the administration to implement greener practices and raise environmental awareness.

- Working with parents through research: A school’s admin staff conduct focus group sessions with parents to identify top concerns.Those concerns will then be addressed and another session conducted at the end of the school year.

- Peer teaching observations and improvements: Kindergarten teachers observe other teachers handling class transition techniques to share best practices.

- PTA surveys and resultant action: The PTA of a district conducts a survey of members regarding their satisfaction with remote learning classes.The results will be presented to the school board for further action.

- Recording and reflecting: A school administrator takes video recordings of playground behavior and then plays them for the teachers. The teachers work together to formulate a list of 10 playground safety guidelines.

- Pre/post testing of interventions: A school board conducts a district wide evaluation of a STEM program by conducting a pre/post-test of students’ skills in computer programming.

- Focus groups of practitioners : The professional development needs of teachers are determined from structured focus group sessions with teachers and admin.

- School lunch research and intervention: A nutrition expert is hired to evaluate and improve the quality of school lunches.

- School nurse systematic checklist and improvements: The school nurse implements a bathroom cleaning checklist to monitor cleanliness after the results of a recent teacher survey revealed several issues.

- Wearable technologies for pedagogical improvements; Students wear accelerometers attached to their hips to gain a baseline measure of physical activity.The results will identify if any issues exist.

- School counselor reflective practice : The school counselor conducts a student survey on antisocial behavior and then plans a series of workshops for both teachers and parents.

Detailed Examples

1. cooperation and leadership.

A science teacher has noticed that her 9 th grade students do not cooperate with each other when doing group projects. There is a lot of arguing and battles over whose ideas will be followed.

So, she decides to implement a simple action research project on the matter. First, she conducts a structured observation of the students’ behavior during meetings. She also has the students respond to a short questionnaire regarding their notions of leadership.

She then designs a two-week course on group dynamics and leadership styles. The course involves learning about leadership concepts and practices . In another element of the short course, students randomly select a leadership style and then engage in a role-play with other students.

At the end of the two weeks, she has the students work on a group project and conducts the same structured observation as before. She also gives the students a slightly different questionnaire on leadership as it relates to the group.

She plans to analyze the results and present the findings at a teachers’ meeting at the end of the term.

2. Professional Development Needs

Two high-school teachers have been selected to participate in a 1-year project in a third-world country. The project goal is to improve the classroom effectiveness of local teachers.

The two teachers arrive in the country and begin to plan their action research. First, they decide to conduct a survey of teachers in the nearby communities of the school they are assigned to.

The survey will assess their professional development needs by directly asking the teachers and administrators. After collecting the surveys, they analyze the results by grouping the teachers based on subject matter.

They discover that history and social science teachers would like professional development on integrating smartboards into classroom instruction. Math teachers would like to attend workshops on project-based learning, while chemistry teachers feel that they need equipment more than training.

The two teachers then get started on finding the necessary training experts for the workshops and applying for equipment grants for the science teachers.

3. Playground Accidents

The school nurse has noticed a lot of students coming in after having mild accidents on the playground. She’s not sure if this is just her perception or if there really is an unusual increase this year. So, she starts pulling data from the records over the last two years. She chooses the months carefully and only selects data from the first three months of each school year.

She creates a chart to make the data more easily understood. Sure enough, there seems to have been a dramatic increase in accidents this year compared to the same period of time from the previous two years.

She shows the data to the principal and teachers at the next meeting. They all agree that a field observation of the playground is needed.

Those observations reveal that the kids are not having accidents on the playground equipment as originally suspected. It turns out that the kids are tripping on the new sod that was installed over the summer.

They examine the sod and observe small gaps between the slabs. Each gap is approximately 1.5 inches wide and nearly two inches deep. The kids are tripping on this gap as they run.

They then discuss possible solutions.

4. Differentiated Learning

Trying to use the same content, methods, and processes for all students is a recipe for failure. This is why modifying each lesson to be flexible is highly recommended. Differentiated learning allows the teacher to adjust their teaching strategy based on all the different personalities and learning styles they see in their classroom.

Of course, differentiated learning should undergo the same rigorous assessment that all teaching techniques go through. So, a third-grade social science teacher asks his students to take a simple quiz on the industrial revolution. Then, he applies differentiated learning to the lesson.

By creating several different learning stations in his classroom, he gives his students a chance to learn about the industrial revolution in a way that captures their interests. The different stations contain: short videos, fact cards, PowerPoints, mini-chapters, and role-plays.

At the end of the lesson, students get to choose how they demonstrate their knowledge. They can take a test, construct a PPT, give an oral presentation, or conduct a simulated TV interview with different characters.

During this last phase of the lesson, the teacher is able to assess if they demonstrate the necessary knowledge and have achieved the defined learning outcomes. This analysis will allow him to make further adjustments to future lessons.

5. Healthy Habits Program

While looking at obesity rates of students, the school board of a large city is shocked by the dramatic increase in the weight of their students over the last five years. After consulting with three companies that specialize in student physical health, they offer the companies an opportunity to prove their value.

So, the board randomly assigns each company to a group of schools. Starting in the next academic year, each company will implement their healthy habits program in 5 middle schools.

Preliminary data is collected at each school at the beginning of the school year. Each and every student is weighed, their resting heart rate, blood pressure and cholesterol are also measured.

After analyzing the data, it is found that the schools assigned to each of the three companies are relatively similar on all of these measures.

At the end of the year, data for students at each school will be collected again. A simple comparison of pre- and post-program measurements will be conducted. The company with the best outcomes will be selected to implement their program city-wide.

Action research is a great way to collect data on a specific issue, implement a change, and then evaluate the effects of that change. It is perhaps the most practical of all types of primary research .

Most likely, the results will be mixed. Some aspects of the change were effective, while other elements were not. That’s okay. This just means that additional modifications to the change plan need to be made, which is usually quite easy to do.

There are many methods that can be utilized, such as surveys, field observations , and program evaluations.

The beauty of action research is based in its utility and flexibility. Just about anyone in a school setting is capable of conducting action research and the information can be incredibly useful.

Aronson, E., & Patnoe, S. (1997). The jigsaw classroom: Building cooperation in the classroom (2nd ed.). New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Gillis, A., & Jackson, W. (2002). Research Methods for Nurses: Methods and Interpretation . Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of SocialIssues, 2 (4), 34-46.

Macdonald, C. (2012). Understanding participatory action research: A qualitative research methodology option. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 13 , 34-50. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v13i2.37 Mertler, C. A. (2008). Action Research: Teachers as Researchers in the Classroom . London: Sage.

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

2 thoughts on “21 Action Research Examples (In Education)”

Where can I capture this article in a better user-friendly format, since I would like to provide it to my students in a Qualitative Methods course at the University of Prince Edward Island? It is a good article, however, it is visually disjointed in its current format. Thanks, Dr. Frank T. Lavandier

Hi Dr. Lavandier,

I’ve emailed you a word doc copy that you can use and edit with your class.

Best, Chris.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Action research in the classroom: A teacher's guide

November 26, 2021

Discover best practices for action research in the classroom, guiding teachers on implementing and facilitating impactful studies in schools.

Main, P (2021, November 26). Action research in the classroom: A teacher's guide. Retrieved from https://www.structural-learning.com/post/action-research-in-the-classroom-a-teachers-guide

What is action research?

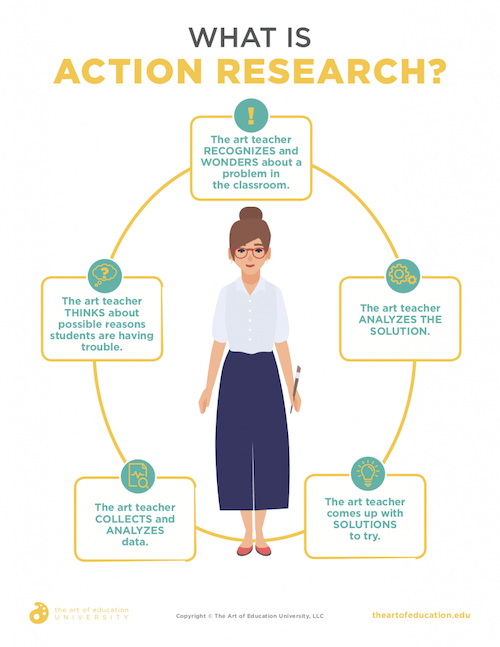

Action research is a participatory process designed to empower educators to examine and improve their own practice. It is characterized by a cycle of planning , action, observation, and reflection, with the goal of achieving a deeper understanding of practice within educational contexts. This process encourages a wide range of approaches and can be adapted to various social contexts.

At its core, action research involves critical reflection on one's actions as a basis for improvement. Senior leaders and teachers are guided to reflect on their educational strategies , classroom management, and student engagement techniques. It's a collaborative effort that often involves not just the teachers but also the students and other stakeholders, fostering an inclusive process that values the input of all participants.

The action research process is iterative, with each cycle aiming to bring about a clearer understanding and improvement in practice. It typically begins with the identification of real-world problems within the school environment, followed by a circle of planning where strategies are developed to address these issues. The implementation of these strategies is then observed and documented, often through journals or participant observation, allowing for reflection and analysis.

The insights gained from action research contribute to Organization Development, enhancing the quality of teaching and learning. This approach is strongly aligned with the principles of Quality Assurance in Education, ensuring that the actions taken are effective and responsive to the needs of the school community.

Educators can share their findings in community forums or through publications in journals, contributing to the wider theory about practice . Tertiary education sector often draws on such studies to inform teacher training and curriculum development.

In summary, the significant parts of action research include:

- A continuous cycle of planning, action, observation, and reflection.

- A focus on reflective practice to achieve a deeper understanding of educational methodologies.

- A commitment to inclusive and participatory processes that engage the entire school community.

Creating an action research project

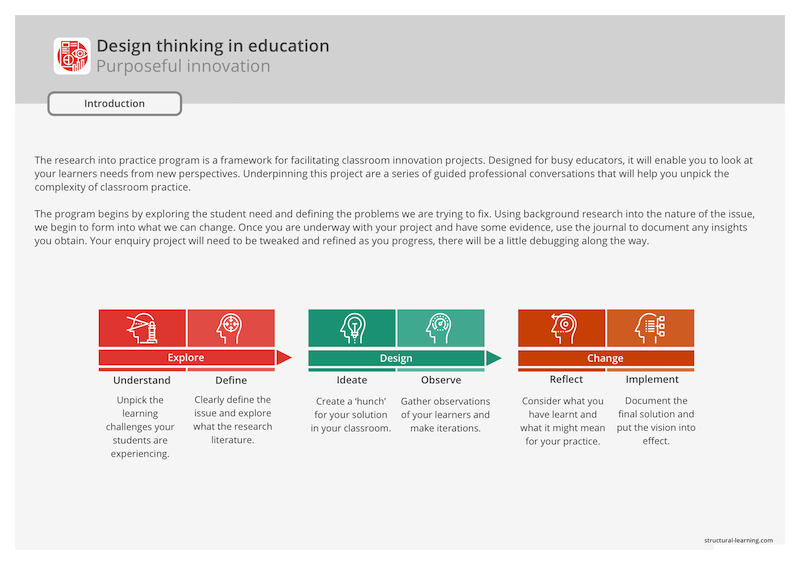

The action research process usually begins with a situation or issue that a teacher wants to change as part of school improvement initiatives .

Teachers get support in changing the ' interesting issue ' into a 'researchable question' and then taking to experiment. The teacher will draw on the outcomes of other researchers to help build actions and reveal the consequences .

Participatory action research is a strategy to the enquiry which has been utilised since the 1940s. Participatory action involves researchers and other participants taking informed action to gain knowledge of a problematic situation and change it to bring a positive effect. As an action researcher , a teacher carries out research . Enquiring into their practice would lead a teacher to question the norms and assumptions that are mostly overlooked in normal school life . Making a routine of inquiry can provide a commitment to learning and professional development . A teacher-researcher holds the responsibility for being the source and agent of change.

Examples of action research projects in education include a teacher working with students to improve their reading comprehension skills , a group of teachers collaborating to develop and implement a new curriculum, or a school administrator conducting a study on the effectiveness of a school-wide behavior management program.

In each of these cases, the research is aimed at improving the educational experience for students and addressing a specific issue or problem within the school community . Action research can be a powerful tool for educators to improve their practice and make a positive impact on their students' learning.

Potential research questions could include:

- How can dual-coding be used to improve my students memory ?

- Does mind-mapping lead to creativity?

- How does Oracy improve my classes writing?

- How can we advance critical thinking in year 10?

- How can graphic organisers be used for exam preparation?

Regardless of the types of action research your staff engage in, a solid cycle of inquiry is an essential aspect of the action research spiral. Building in the process of reflection will ensure that key points of learning can be extracted from the action research study.

What is an action research cycle?

Action research in education is a cycle of reflection and action inquiry , which follows these steps:

1. Identifying the problem

It is the first stage of action research that starts when a teacher identifies a problem or question that they want to address. To make an a ction research approach successful, the teacher needs to ensure that the questions are the ones 'they' wish to solve. Their questions might involve social sciences, instructional strategies, everyday life and social management issues, guide for students analytical research methods for improving specific student performance or curriculum implementation etc. Teachers may seek help from a wide variety of existing literature , to find strategies and solutions that others have executed to solve any particular problem. It is also suggested to build a visual map or a table of problems, target performances, potential solutions and supporting references in the middle.

2. Developing an Action Plan

After identifying the problem, after r eviewing the relevant literature and describing the vision of how to solve the problem; the next step would be action planning which means to develop a plan of action . Action planning involves studying the literature and brainstorming can be used by the action research planner to create new techniques and strategies that can generate better results of both action learning and action research. One may go back to the visual map or table of contents and reorder or colour-code the potential outcomes. The items in the list can be ranked in order of significance and the amount of time needed for these strategies.

An action plan has the details of how to implement each idea and the factors that may keep them from their vision of success . Identify those factors that cannot be changed –these are the constants in an equation. The focus of action research at the planning stage must remain focused on the variables –the factors that can be changed using actions. An action plan must be how to implement a solution and how one's instruction, management style, and behaviour will affect each of the variables.

3. Data Collection

Before starting to implement a plan of action , the researcher must have a complete understanding of action research and must have knowledge of the type of data that may help in the success of the plan and must assess how to collect that data. For instance, if the goal is to improve class attendance, attendance records must be collected as useful data for the participatory action. If the goal is to improve time management, the data may include students and classroom observations . There are many options to choose from to collect data from. Selecting the most suitable methodology for data collection will provide more meaningful , accurate and valid data. Some sources of data are interviews and observation. Also, one may administer surveys , distribute questionnaires and watch videotapes of the classroom to collect data.

4. Data Analysis and Conclusions

At this action stage, an action researcher analyses the collected data and concludes. It is suggested to assess the data during the predefined process of data collection as it will help refine the action research agenda. If the collected data seems insufficient , the data collection plan must be revised. Data analysis also helps to reflect on what exactly happened. Did the action researcher perform the actions as planned? Were the study outcomes as expected? Which assumptions of the action researcher proved to be incorrect?

Adding details such as tables, opinions, and recommendations can help in identifying trends (correlations and relationships). One must share the findings while analysing data and drawing conclusions . Engaging in conversations for teacher growth is essential; hence, the action researcher would share the findings with other teachers through discussion of action research, who can yield useful feedback. One may also share the findings with students, as they can also provide additional insight . For example, if teachers and students agree with the conclusions of action research for educational change, it adds to the credibility of the data collection plan and analysis. If they don't seem to agree with the data collection plan and analysis , the action researchers may take informed action and refine the data collection plan and reevaluate conclusions .

5. Modifying the Educational Theory and Repeat

After concluding, the process begins again. The teacher can adjust different aspects of the action research approach to theory or make it more specific according to the findings . Action research guides how to change the steps of action research development, how to modify the action plan , and provide better access to resources, start data collection once again, or prepare new questions to ask from the respondents.

6. Report the Findings

Since the main approach to action research involves the informed action to introduce useful change into the classroom or schools, one must not forget to share the outcomes with others. Sharing the outcomes would help to further reflect on the problem and process, and it would help other teachers to use these findings to enhance their professional practice as an educator. One may print book and share the experience with the school leaders, principal, teachers and students as they served as guide to action research. Or, a community action researcher may present community-based action research at a conference so people from other areas can take advantage of this collaborative action. Also, teachers may use a digital storytelling tool to outline their results.

There are plenty of creative tools we can use to bring the research projects to life. We have seen videos, podcasts and research posters all being used to communicate the results of these programs. Community action research is a unique way to present details of the community-related adventures in the teacher profession, cultivate expertise and show how teachers think about education , so it is better to find unique ways to report the findings of community-led action research.

Final thoughts on action-research for teachers

As we have seen, action research can be an effective form of professional development, illuminating the path for teachers and school leaders seeking to refine their craft. This cyclical process of inquiry and reflection is not merely a methodological pursuit but a profound professional journey. The definition of action research, as a systematic inquiry conducted by teachers, administrators, and other stakeholders in the teaching/learning environment, emphasizes the collaborative nature of improving educational strategies and outcomes.

Action research transcends traditional disciplinary practices by immersing educators in the social contexts of their work, prompting them to question and adapt their methods to meet the evolving needs of their students . It is a form of reflective practice that demands critical thinking and flexibility, as one navigates through the iterative stages of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting.

The process of action research is inherently participatory, encouraging educators to engage with their learning communities to address key issues and social issues that impact educational settings. This method empowers professionals within universities and schools alike to take ownership of their learning and development, fostering a culture of continuous improvement and participatory approaches.

In summary, action research encapsulates the essence of what it means to be a learning professional in a dynamic educational landscape. It is the embodiment of a commitment to lifelong learning and a testament to the capacity of educators to enact change . The value of action research lies in its ability to transform practitioners into researchers, where the quest for knowledge becomes a powerful conduit for change and innovation. Thus, for educators at every level, embracing the rigorous yet rewarding path of action research can unveil potent insights and propel educational practice to new heights.

Key Papers on Action Research

- Utilizing Action Research During Student Teaching by James O. Barbre and Brenda J. Buckner (2013): This study explores how action research can be effectively utilized during student teaching to enhance professional pedagogical disposition through active reflection. It emphasizes developing a reflective habit of mind crucial for teachers to be effective in their classrooms and adaptive to the changing needs of their students.

- Repositioning T eacher Action Research in Science Teacher Education by B. Capobianco and A. Feldman (2010): This paper discusses the promotion of action research as a way for teachers to improve their practice and students' learning for over 50 years, focusing on science education. It highlights the importance of action research in advancing knowledge about teaching and learning in science.

- Action research and teacher leadership by K. Smeets and P. Ponte (2009): This article reports on a case study into the influence and impact of action research carried out by teachers in a special school. It found that action research not only helps teachers to get to grips with their work in the classroom but also has an impact on the work of others in the school.

- Teaching about the Nature of Science through History: Action Research in the Classroom by J. Solomon, Jon Duveen, Linda Scot, S. McCarthy (1992): This article reports on 18 months of action research monitoring British pupils' learning about the nature of science using historical aspects. It indicates areas of substantial progress in pupils' understanding of the nature of science.

- Action Research in the Classroom by V. Baumfield, E. Hall, K. Wall (2008): This comprehensive guide to conducting action research in the classroom covers various aspects, including deciding on a research question, choosing complementary research tools, collecting and interpreting data, and sharing findings. It aims to move classroom inquiry forward and contribute to professional development.

These studies highlight the significant role of action research in enhancing teacher effectiveness, student learning outcomes, and contributing to the broader educational community's knowledge and practices.

Enhance Learner Outcomes Across Your School

Download an Overview of our Support and Resources

We'll send it over now.

Please fill in the details so we can send over the resources.

What type of school are you?

We'll get you the right resource

Is your school involved in any staff development projects?

Are your colleagues running any research projects or courses?

Do you have any immediate school priorities?

Please check the ones that apply.

Download your resource

Thanks for taking the time to complete this form, submit the form to get the tool.

Classroom Practice

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

How to Do Action Research in Your Classroom

You are here

This article is available as a pdf. please see the link on the right..

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A Collaborative Action Research Project in the Kindergarten: Perspectives and Challenges for Teacher Development through Internal Evaluation Processes

2010, New Horizons in Education

Related Papers

International Journal of Early Childhood Learning, 19, 13-28

Αργύρης Κυρίδης

Evaluation constitutes an integral part of the learning process and seeks to improve the education provided. In addition, it can emphasize the importance of children’s knowledge, skills and interests, describe their progress in specific learning goals as well as document their development in time. If well applied, evaluation can evolve into a powerful tool in the hands of kindergarten teachers, reinforce children’s learning and constitute the keystone of meaningful discussion between families and kindergarten teachers. The present paper examines kindergarten teachers’ views on the process of evaluation in the area of Western Macedonia, Greece. It comprises three parts: The first part presents the theoretical framework on which the research was based; the research project is described in the second part, finally, the results are discussed the third part.

türker Sezer

In this study, before and after they become teachers, the views of preschool teacher candidates on knowledge, skills and practices regarding child assessment and evaluation were determined. This study utilizes qualitative research method, and interview technique was used to obtain data. The study group consists of 20 preschool teacher candidates who are senior students at a public university's department of preschool education. As data collection tool, 8 open-ended questions were designed and asked to participants. Among study group, nine teachers who work as teachers were volunteered to participate in the study. Four open-ended questions were transmitted to them electronically and descriptive analyses of all obtained data were conducted. As a result of the study, it was found that teacher candidates generally think that they have sufficient level of knowledge regarding assessment and evaluation. Teacher candidates also stated that the knowledge they gain during undergraduate ed...

International Research in Higher Education

Maria Sakellariou

The evaluation of the pedagogical process in early childhood care and education is an up-to-date and controversial subject of study in the context of scientific and policy choices and actions (Charisis, 2006; Doliopoulou & Gourgiotou, 2008;·McAfee, Leong, Bodrova, 2010). The purpose of this paper is to investigate the evaluation techniques applied in preschool education by the teachers and prospective teachers in kindergartens, who are also the sample of our research, in the region of Epirus and at the University of Ioannina. In our research we used the structured questionnaire with closed and some clarifying open-ended questions. The data of the research highlighted the prospective teachers’ more positive attitude to apply alternative evaluation techniques to kindergarten but ultimately the difficulty in their practical implementation. Despite the limitations of the research, the data is the trigger for further exploration of the subject of teacher education and the reform of the c...

Erken Çocukluk Çalışmaları Dergisi

TÜRKER SEZER

In this study, before and after they become teachers, the views of preschool teacher candidates on knowledge, skills and practices regarding child assessment and evaluation were determined. This study utilizes qualitative research method, and interview technique was used to obtain data. The study group consists of 20 preschool teacher candidates who are senior students at a public university’s department of preschool education. As data collection tool, 8 open-ended questions were designed and asked to participants. Among study group, nine teachers who work as teachers were volunteered to participate in the study. Four open-ended questions were transmitted to them electronically and descriptive analyses of all obtained data were conducted. As a result of the study, it was found that teacher candidates generally think that they have sufficient level of knowledge regarding assessment and evaluation. Teacher candidates also stated that the knowledge they gain during undergraduate educat...

Universal Journal of Educational Research

Horizon Research Publishing(HRPUB) Kevin Nelson

This paper investigates the feedback and assessment routines that are being established in the subject of pedagogy in the new model of Kindergarten Teacher Education (Barnehagelaererutdanning-BLU) in Norway. This scope is chosen due to the particular role of the subject of pedagogy in strengthening the understanding of the practice field, and in ensuring a coherent, professionally oriented perspective. The data comprise group interviews with three pedagogy teachers, two pedagogues from in-service kindergartens and one interview with one student. The gathered data were analysed according to guidelines for qualitative content analysis [1], and interpreted in the light of Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT). Results show that pedagogues both at BLU and in-service kindergartens experience many challenges connected to formative assessment and feedback practice: (a) a tacit, private and low-priority assessment culture; (b) current practice characterized by summative assessment methods; and (c) minimal collaboration between involved participants. In conclusion, the paper suggests the following improvements in the area of feedback and assessment in the new BLU: (a) establishing a closer and more reciprocal collaboration between all participants; (b) encouraging a shared understanding of central goals and methods in formative assessment, and (c) increasing the status of assessment work and ensuring time resources to involved teachers.

Anastasios Pekis

Jurnal Basicedu

Aqiel Mutawalli

This study aims to describe the competence of SD/MI level teachers in the learning evaluation process. This is intended as an effort to classify the form of assessment of elementary age children. This study uses a qualitative approach with the method of literature study. Sources of data and study analysis materials are relevant scientific works including books, articles and proceedings. This study concludes that a teacher is required to be able to carry out assessments and evaluations of learning processes and outcomes and to utilize the results of these assessments and evaluations in an effort to take reflective action to improve the quality of learning. Evaluation is interpreted as a systematic process carried out to assess an object based on certain criteria and prerequisites. Some of the evaluation principles needed as a guide in evaluation activities include; valid, objective, fair, integrated, open, comprehensive and continuous, systematic, based on criteria, and accountable. ...

Academy of Educational Leadership Journal

Mariandri Kazi

The ultimate goal of this article is to present and understand the possibilities that arise through the evaluation of the educational project in the teacher's professional development, as well as the improvement of the school unit, which has emerged in recent years from modern international literature. The evaluation should be approached in the sense of improvement, emphasizing effective, but at the same time, alternative practices, which have multiple benefits to the levels of the teacher, the Principal, the school unit, and, by extension, the education system. In addition, it should focus on the essence of the process and, at the same time, promote the cultivation of evaluation culture as a process of improving the quality of the education provided. By focusing on promotion and utilizing alternative evaluation practices, educational systems can achieve effectiveness at all levels. In particular, through the adoption of alternative evaluation practices, such as mentoring, peer coaching, teaching observation, self-assessment of the teacher, and evaluation by the leader/external evaluator and/or by the students promoting continuous improvement. In the current time of uncertainty, alternative evaluation practices can be applied in a similar way through digital methods. The utilization of multiple resources for evaluation is the key to providing an effective evaluation system. Keywords: Evaluation Practices, Teacher’s Development, School Improvement.

International Journal of Leadership in Education

Yiasemina Karagiorgi

This case study aims to enquire into the journey of a Greek-Cypriot primary school through a self-evaluating process, in accordance to the respective guidelines proposed in the national educational reform documents. The article outlines the phases involved, beginning from the collection of information, moving to the formulation of a school development plan and ending with some preliminary impressions of teachers as implementers. Analyses of minutes of the weekly staff meetings as well as questionnaires distributed to participating teachers indicate that this self-initiated participatory approach apparently had vitality and drive but also suffered due to the lack of wider systemic support. This study underlines the significance of the ideographic and nomothetic dimension of school culture for the development of school self-evaluation (SSE). Emerging considerations appear to resemble issues of school effectiveness and school improvement underpinning SSE worldwide and the need to draw links between the two paradigms. In pursuit of a mixed approach, measures such as a focus on SSE outcomes along with the establishment of school autonomy, which could facilitate the initiation and sustainability of SSE practices in Greek-Cypriot schools, are further discussed.

Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences

RELATED PAPERS

Dina astriani sijabat

International braz j urol

Kavina Jani

Environmental Science and Engineering

Hailleen Varela

izzatul Mardhiah

Belén Galletero Campos

Núria Pérez-Escoda

Nilambar Sethi

Archivos de medicina veterinaria

Ana Gonzalez

Diwan: Jurnal Bahasa dan Sastra Arab

muhammad adek

Chilean journal of agricultural research

Mario D'Antuono

Journal of Documentation

Emmanuel Yannakoudakis

Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences

knezevic miroslav

Academic Emergency Medicine

mauricio romero

DR. KARUNA MARKAM

Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking

Microwave and Optical Technology Letters

Javier Alda

Wietske Prummel

Valerie Standen

Postmigration

Hans Christian Post

Current Biology

Jaideep Mathur

Roman Ozimec

Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pengabdian Masyarakat

Januardi Januardi

Journal of Computer Science

Dr.Khaled Alalayah

Pedro d'Alte

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Action research: The benefits for early childhood educators

- This article introduces the purpose, process and benefits of engaging in action research in early childhood settings.

- Engaging in action research is an effective form of professional learning for educators.

- Action research is authentic because it allows educators to respond to issues of importance unique to their own settings.

- Educators have ownership over their action research projects, resulting in ‘transformative’ rather than ‘transmissive’ professional learning.

- Using action research in early childhood settings invites collaboration between educators, families and community.

- The focus of an action research project can be personalised to respond to educators’ interests and passions.

- The cycle of action research invites a sustained engagement in a particular aspect of educators’ work, providing many opportunities to question and reflect on the research topic.

Publication

Miller, M. (2017). Action research: The benefits for early childhood educators. Belonging: Early Years Journal , 6 (3) , pp. 26- 3 2 https://eprints.qut.edu.au/114335/

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Preparing for Action Research in the Classroom: Practical Issues

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What sort of considerations are necessary to take action in your educational context?

- How do you facilitate an action plan without disrupting your teaching?

- How do you respond when the unplanned happens during data collection?

An action research project is a practical endeavor that will ultimately be shaped by your educational context and practice. Now that you have developed a literature review, you are ready to revise your initial plans and begin to plan your project. This chapter will provide some advice about your considerations when undertaking an action research project in your classroom.

Maintain Focus

Hopefully, you found a lot a research on your topic. If so, you will now have a better understanding of how it fits into your area and field of educational research. Even though the topic and area you are researching may not be small, your study itself should clearly focus on one aspect of the topic in your classroom. It is important to maintain clarity about what you are investigating because a lot will be going on simultaneously during the research process and you do not want to spend precious time on erroneous aspects that are irrelevant to your research.

Even though you may view your practice as research, and vice versa, you might want to consider your research project as a projection or megaphone for your work that will bring attention to the small decisions that make a difference in your educational context. From experience, our concern is that you will find that researching one aspect of your practice will reveal other interconnected aspects that you may find interesting, and you will disorient yourself researching in a confluence of interests, commitments, and purposes. We simply want to emphasize – don’t try to research everything at once. Stay focused on your topic, and focus on exploring it in depth, instead of its many related aspects. Once you feel you have made progress in one aspect, you can then progress to other related areas, as new research projects that continue the research cycle.

Identify a Clear Research Question

Your literature review should have exposed you to an array of research questions related to your topic. More importantly, your review should have helped identify which research questions we have addressed as a field, and which ones still need to be addressed . More than likely your research questions will resemble ones from your literature review, while also being distinguishable based upon your own educational context and the unexplored areas of research on your topic.

Regardless of how your research question took shape, it is important to be clear about what you are researching in your educational context. Action research questions typically begin in ways related to “How does … ?” or “How do I/we … ?”, for example:

Research Question Examples

- How does a semi-structured morning meeting improve my classroom community?

- How does historical fiction help students think about people’s agency in the past?

- How do I improve student punctuation use through acting out sentences?

- How do we increase student responsibility for their own learning as a team of teachers?

I particularly favor questions with I or we, because they emphasize that you, the actor and researcher, will be clearly taking action to improve your practice. While this may seem rather easy, you need to be aware of asking the right kind of question. One issue is asking a too pointed and closed question that limits the possibility for analysis. These questions tend to rely on quantitative answers, or yes/no answers. For example, “How many students got a 90% or higher on the exam, after reviewing the material three times?

Another issue is asking a question that is too broad, or that considers too many variables. For example, “How does room temperature affect students’ time-on-task?” These are obviously researchable questions, but the aim is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables that has little or no value to your daily practice.

I also want to point out that your research question will potentially change as the research develops. If you consider the question:

As you do an activity, you may find that students are more comfortable and engaged by acting sentences out in small groups, instead of the whole class. Therefore, your question may shift to:

- How do I improve student punctuation use through acting out sentences, in small groups ?

By simply engaging in the research process and asking questions, you will open your thinking to new possibilities and you will develop new understandings about yourself and the problematic aspects of your educational context.

Understand Your Capabilities and Know that Change Happens Slowly

Similar to your research question, it is important to have a clear and realistic understanding of what is possible to research in your specific educational context. For example, would you be able to address unsatisfactory structures (policies and systems) within your educational context? Probably not immediately, but over time you potentially could. It is much more feasible to think of change happening in smaller increments, from within your own classroom or context, with you as one change agent. For example, you might find it particularly problematic that your school or district places a heavy emphasis on traditional grades, believing that these grades are often not reflective of the skills students have or have not mastered. Instead of attempting to research grading practices across your school or district, your research might instead focus on determining how to provide more meaningful feedback to students and parents about progress in your course. While this project identifies and addresses a structural issue that is part of your school and district context, to keep things manageable, your research project would focus the outcomes on your classroom. The more research you do related to the structure of your educational context the more likely modifications will emerge. The more you understand these modifications in relation to the structural issues you identify within your own context, the more you can influence others by sharing your work and enabling others to understand the modification and address structural issues within their contexts. Throughout your project, you might determine that modifying your grades to be standards-based is more effective than traditional grades, and in turn, that sharing your research outcomes with colleagues at an in-service presentation prompts many to adopt a similar model in their own classrooms. It can be defeating to expect the world to change immediately, but you can provide the spark that ignites coordinated changes. In this way, action research is a powerful methodology for enacting social change. Action research enables individuals to change their own lives, while linking communities of like-minded practitioners who work towards action.

Plan Thoughtfully

Planning thoughtfully involves having a path in mind, but not necessarily having specific objectives. Due to your experience with students and your educational context, the research process will often develop in ways as you expected, but at times it may develop a little differently, which may require you to shift the research focus and change your research question. I will suggest a couple methods to help facilitate this potential shift. First, you may want to develop criteria for gauging the effectiveness of your research process. You may need to refine and modify your criteria and your thinking as you go. For example, we often ask ourselves if action research is encouraging depth of analysis beyond my typical daily pedagogical reflection. You can think about this as you are developing data collection methods and even when you are collecting data. The key distinction is whether the data you will be collecting allows for nuance among the participants or variables. This does not mean that you will have nuance, but it should allow for the possibility. Second, criteria are shaped by our values and develop into standards of judgement. If we identify criteria such as teacher empowerment, then we will use that standard to think about the action contained in our research process. Our values inform our work; therefore, our work should be judged in relation to the relevance of our values in our pedagogy and practice.

Does Your Timeline Work?

While action research is situated in the temporal span that is your life, your research project is short-term, bounded, and related to the socially mediated practices within your educational context. The timeline is important for bounding, or setting limits to your research project, while also making sure you provide the right amount of time for the data to emerge from the process.

For example, if you are thinking about examining the use of math diaries in your classroom, you probably do not want to look at a whole semester of entries because that would be a lot of data, with entries related to a wide range of topics. This would create a huge data analysis endeavor. Therefore, you may want to look at entries from one chapter or unit of study. Also, in terms of timelines, you want to make sure participants have enough time to develop the data you collect. Using the same math example, you would probably want students to have plenty of time to write in the journals, and also space out the entries over the span of the chapter or unit.

In relation to the examples, we think it is an important mind shift to not think of research timelines in terms of deadlines. It is vitally important to provide time and space for the data to emerge from the participants. Therefore, it would be potentially counterproductive to rush a 50-minute data collection into 20 minutes – like all good educators, be flexible in the research process.

Involve Others

It is important to not isolate yourself when doing research. Many educators are already isolated when it comes to practice in their classroom. The research process should be an opportunity to engage with colleagues and open up your classroom to discuss issues that are potentially impacting your entire educational context. Think about the following relationships:

Research participants

You may invite a variety of individuals in your educational context, many with whom you are in a shared situation (e.g. colleagues, administrators). These participants may be part of a collaborative study, they may simply help you develop data collection instruments or intervention items, or they may help to analyze and make sense of the data. While the primary research focus will be you and your learning, you will also appreciate how your learning is potentially influencing the quality of others’ learning.

We always tell educators to be public about your research, or anything exciting that is happening in your educational context, for that matter. In terms of research, you do not want it to seem mysterious to any stakeholder in the educational context. Invite others to visit your setting and observe your research process, and then ask for their formal feedback. Inviting others to your classroom will engage and connect you with other stakeholders, while also showing that your research was established in an ethic of respect for multiple perspectives.

Critical friends or validators

Using critical friends is one way to involve colleagues and also validate your findings and conclusions. While your positionality will shape the research process and subsequently your interpretations of the data, it is important to make sure that others see similar logic in your process and conclusions. Critical friends or validators provide some level of certification that the frameworks you use to develop your research project and make sense of your data are appropriate for your educational context. Your critical friends and validators’ suggestions will be useful if you develop a report or share your findings, but most importantly will provide you confidence moving forward.

Potential researchers

As an educational researcher, you are involved in ongoing improvement plans and district or systemic change. The flexibility of action research allows it to be used in a variety of ways, and your initial research can spark others in your context to engage in research either individually for their own purposes, or collaboratively as a grade level, team, or school. Collaborative inquiry with other educators is an emerging form of professional learning and development for schools with school improvement plans. While they call it collaborative inquiry, these schools are often using an action research model. It is good to think of all of your colleagues as potential research collaborators in the future.

Prioritize Ethical Practice

Try to always be cognizant of your own positionality during the action research process, its relation to your educational context, and any associated power relation to your positionality. Furthermore, you want to make sure that you are not coercing or engaging participants into harmful practices. While this may seem obvious, you may not even realize you are harming your participants because you believe the action is necessary for the research process.

For example, commonly teachers want to try out an intervention that will potentially positively impact their students. When the teacher sets up the action research study, they may have a control group and an experimental group. There is potential to impair the learning of one of these groups if the intervention is either highly impactful or exceedingly worse than the typical instruction. Therefore, teachers can sometimes overlook the potential harm to students in pursuing an experimental method of exploring an intervention.

If you are working with a university researcher, ethical concerns will be covered by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). If not, your school or district may have a process or form that you would need to complete, so it would beneficial to check your district policies before starting. Other widely accepted aspects of doing ethically informed research, include:

Confirm Awareness of Study and Negotiate Access – with authorities, participants and parents, guardians, caregivers and supervisors (with IRB this is done with Informed Consent).

- Promise to Uphold Confidentiality – Uphold confidentiality, to your fullest ability, to protect information, identity and data. You can identify people if they indicate they want to be recognized for their contributions.

- Ensure participants’ rights to withdraw from the study at any point .

- Make sure data is secured, either on password protected computer or lock drawer .

Prepare to Problematize your Thinking

Educational researchers who are more philosophically-natured emphasize that research is not about finding solutions, but instead is about creating and asking new and more precise questions. This is represented in the action research process shown in the diagrams in Chapter 1, as Collingwood (1939) notes the aim in human interaction is always to keep the conversation open, while Edward Said (1997) emphasized that there is no end because whatever we consider an end is actually the beginning of something entirely new. These reflections have perspective in evaluating the quality in research and signifying what is “good” in “good pedagogy” and “good research”. If we consider that action research is about studying and reflecting on one’s learning and how that learning influences practice to improve it, there is nothing to stop your line of inquiry as long as you relate it to improving practice. This is why it is necessary to problematize and scrutinize our practices.

Ethical Dilemmas for Educator-Researchers

Classroom teachers are increasingly expected to demonstrate a disposition of reflection and inquiry into their own practice. Many advocate for schools to become research centers, and to produce their own research studies, which is an important advancement in acknowledging and addressing the complexity in today’s schools. When schools conduct their own research studies without outside involvement, they bypass outside controls over their studies. Schools shift power away from the oversight of outside experts and ethical research responsibilities are shifted to those conducting the formal research within their educational context. Ethics firmly grounded and established in school policies and procedures for teaching, becomes multifaceted when teaching practice and research occur simultaneously. When educators conduct research in their classrooms, are they doing so as teachers or as researchers, and if they are researchers, at what point does the teaching role change to research? Although the notion of objectivity is a key element in traditional research paradigms, educator-based research acknowledges a subjective perspective as the educator-researcher is not viewed separately from the research. In action research, unlike traditional research, the educator as researcher gains access to the research site by the nature of the work they are paid and expected to perform. The educator is never detached from the research and remains at the research site both before and after the study. Because studying one’s practice comprises working with other people, ethical deliberations are inevitable. Educator-researchers confront role conflict and ambiguity regarding ethical issues such as informed consent from participants, protecting subjects (students) from harm, and ensuring confidentiality. They must demonstrate a commitment toward fully understanding ethical dilemmas that present themselves within the unique set of circumstances of the educational context. Questions about research ethics can feel exceedingly complex and in specific situations, educator- researchers require guidance from others.

Think about it this way. As a part-time historian and former history teacher I often problematized who we regard as good and bad people in history. I (Clark) grew up minutes from Jesse James’ childhood farm. Jesse James is a well-documented thief, and possibly by today’s standards, a terrorist. He is famous for daylight bank robberies, as well as the sheer number of successful robberies. When Jesse James was assassinated, by a trusted associate none-the-less, his body travelled the country for people to see, while his assailant and assailant’s brother reenacted the assassination over 1,200 times in theaters across the country. Still today in my hometown, they reenact Jesse James’ daylight bank robbery each year at the Fall Festival, immortalizing this thief and terrorist from our past. This demonstrates how some people saw him as somewhat of hero, or champion of some sort of resistance, both historically and in the present. I find this curious and ripe for further inquiry, but primarily it is problematic for how we think about people as good or bad in the past. Whatever we may individually or collectively think about Jesse James as a “good” or “bad” person in history, it is vitally important to problematize our thinking about him. Talking about Jesse James may seem strange, but it is relevant to the field of action research. If we tell people that we are engaging in important and “good” actions, we should be prepared to justify why it is “good” and provide a theoretical, epistemological, or ontological rationale if possible. Experience is never enough, you need to justify why you act in certain ways and not others, and this includes thinking critically about your own thinking.

Educators who view inquiry and research as a facet of their professional identity must think critically about how to design and conduct research in educational settings to address respect, justice, and beneficence to minimize harm to participants. This chapter emphasized the due diligence involved in ethically planning the collection of data, and in considering the challenges faced by educator-researchers in educational contexts.

Planning Action

After the thinking about the considerations above, you are now at the stage of having selected a topic and reflected on different aspects of that topic. You have undertaken a literature review and have done some reading which has enriched your understanding of your topic. As a result of your reading and further thinking, you may have changed or fine-tuned the topic you are exploring. Now it is time for action. In the last section of this chapter, we will address some practical issues of carrying out action research, drawing on both personal experiences of supervising educator-researchers in different settings and from reading and hearing about action research projects carried out by other researchers.

Engaging in an action research can be a rewarding experience, but a beneficial action research project does not happen by accident – it requires careful planning, a flexible approach, and continuous educator-researcher reflection. Although action research does not have to go through a pre-determined set of steps, it is useful here for you to be aware of the progression which we presented in Chapter 2. The sequence of activities we suggested then could be looked on as a checklist for you to consider before planning the practical aspects of your project.

We also want to provide some questions for you to think about as you are about to begin.

- Have you identified a topic for study?

- What is the specific context for the study? (It may be a personal project for you or for a group of researchers of which you are a member.)

- Have you read a sufficient amount of the relevant literature?

- Have you developed your research question(s)?

- Have you assessed the resource needed to complete the research?

As you start your project, it is worth writing down:

- a working title for your project, which you may need to refine later;

- the background of the study , both in terms of your professional context and personal motivation;

- the aims of the project;

- the specific outcomes you are hoping for.

Although most of the models of action research presented in Chapter 1 suggest action taking place in some pre-defined order, they also allow us the possibility of refining our ideas and action in the light of our experiences and reflections. Changes may need to be made in response to your evaluation and your reflections on how the project is progressing. For example, you might have to make adjustments, taking into account the students’ responses, your observations and any observations of your colleagues. All this is very useful and, in fact, it is one of the features that makes action research suitable for educational research.

Action research planning sheet

In the past, we have provided action researchers with the following planning list that incorporates all of these considerations. Again, like we have said many times, this is in no way definitive, or lock-in-step procedure you need to follow, but instead guidance based on our perspective to help you engage in the action research process. The left column is the simplified version, and the right column offers more specific advice if need.

Figure 4.1 Planning Sheet for Action Research

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Our Mission

How Teachers Can Learn Through Action Research

A look at one school’s action research project provides a blueprint for using this model of collaborative teacher learning.

When teachers redesign learning experiences to make school more relevant to students’ lives, they can’t ignore assessment. For many teachers, the most vexing question about real-world learning experiences such as project-based learning is: How will we know what students know and can do by the end of this project?

Teachers at the Siena School in Silver Spring, Maryland, decided to figure out the assessment question by investigating their classroom practices. As a result of their action research, they now have a much deeper understanding of authentic assessment and a renewed appreciation for the power of learning together.

Their research process offers a replicable model for other schools interested in designing their own immersive professional learning. The process began with a real-world challenge and an open-ended question, involved a deep dive into research, and ended with a public showcase of findings.

Start With an Authentic Need to Know

Siena School serves about 130 students in grades 4–12 who have mild to moderate language-based learning differences, including dyslexia. Most students are one to three grade levels behind in reading.

Teachers have introduced a variety of instructional strategies, including project-based learning, to better meet students’ learning needs and also help them develop skills like collaboration and creativity. Instead of taking tests and quizzes, students demonstrate what they know in a PBL unit by making products or generating solutions.

“We were already teaching this way,” explained Simon Kanter, Siena’s director of technology. “We needed a way to measure, was authentic assessment actually effective? Does it provide meaningful feedback? Can teachers grade it fairly?”

Focus the Research Question

Across grade levels and departments, teachers considered what they wanted to learn about authentic assessment, which the late Grant Wiggins described as engaging, multisensory, feedback-oriented, and grounded in real-world tasks. That’s a contrast to traditional tests and quizzes, which tend to focus on recall rather than application and have little in common with how experts go about their work in disciplines like math or history.

The teachers generated a big research question: Is using authentic assessment an effective and engaging way to provide meaningful feedback for teachers and students about growth and proficiency in a variety of learning objectives, including 21st-century skills?

Take Time to Plan

Next, teachers planned authentic assessments that would generate data for their study. For example, middle school science students created prototypes of genetically modified seeds and pitched their designs to a panel of potential investors. They had to not only understand the science of germination but also apply their knowledge and defend their thinking.

In other classes, teachers planned everything from mock trials to environmental stewardship projects to assess student learning and skill development. A shared rubric helped the teachers plan high-quality assessments.

Make Sense of Data

During the data-gathering phase, students were surveyed after each project about the value of authentic assessments versus more traditional tools like tests and quizzes. Teachers also reflected after each assessment.

“We collated the data, looked for trends, and presented them back to the faculty,” Kanter said.

Among the takeaways:

- Authentic assessment generates more meaningful feedback and more opportunities for students to apply it.

- Students consider authentic assessment more engaging, with increased opportunities to be creative, make choices, and collaborate.

- Teachers are thinking more critically about creating assessments that allow for differentiation and that are applicable to students’ everyday lives.

To make their learning public, Siena hosted a colloquium on authentic assessment for other schools in the region. The school also submitted its research as part of an accreditation process with the Middle States Association.

Strategies to Share

For other schools interested in conducting action research, Kanter highlighted three key strategies.

- Focus on areas of growth, not deficiency: “This would have been less successful if we had said, ‘Our math scores are down. We need a new program to get scores up,’ Kanter said. “That puts the onus on teachers. Data collection could seem punitive. Instead, we focused on the way we already teach and thought about, how can we get more accurate feedback about how students are doing?”

- Foster a culture of inquiry: Encourage teachers to ask questions, conduct individual research, and share what they learn with colleagues. “Sometimes, one person attends a summer workshop and then shares the highlights in a short presentation. That might just be a conversation, or it might be the start of a school-wide initiative,” Kanter explained. In fact, that’s exactly how the focus on authentic assessment began.

- Build structures for teacher collaboration: Using staff meetings for shared planning and problem-solving fosters a collaborative culture. That was already in place when Siena embarked on its action research, along with informal brainstorming to support students.

For both students and staff, the deep dive into authentic assessment yielded “dramatic impact on the classroom,” Kanter added. “That’s the great part of this.”

In the past, he said, most teachers gave traditional final exams. To alleviate students’ test anxiety, teachers would support them with time for content review and strategies for study skills and test-taking.

“This year looks and feels different,” Kanter said. A week before the end of fall term, students were working hard on final products, but they weren’t cramming for exams. Teachers had time to give individual feedback to help students improve their work. “The whole climate feels way better.”

200+ List of Topics for Action Research in the Classroom

In the dynamic landscape of education, teachers are continually seeking innovative ways to enhance their teaching practices and improve student outcomes. Action research in the classroom is a powerful tool that allows educators to investigate and address specific challenges, leading to positive changes in teaching methods and learning experiences.

Selecting the right topics from the list of topics for action research in the classroom is crucial for ensuring meaningful insights and improvements. In this blog post, we will explore the significance of action research in the classroom, the criteria for selecting impactful topics, and provide an extensive list of potential research areas.

Understanding: What is Action Research

Table of Contents

Action research is a reflective process that empowers teachers to systematically investigate and analyze their own teaching practices. Unlike traditional research, action research is conducted by educators within their own classrooms, emphasizing a collaborative and participatory approach.

This method enables teachers to identify challenges, implement interventions, and assess the effectiveness of their actions.

How to Select Topics From List of Topics for Action Research in the Classroom

Choosing the right topic is the first step in the action research process. The selected topic should align with classroom goals, address students’ needs, be feasible to implement, and have the potential for positive impact. Teachers should consider the following criteria when selecting action research topics:

- Alignment with Classroom Goals and Objectives: The chosen topic should directly contribute to the overall goals and objectives of the classroom. Whether it’s improving student engagement, enhancing learning outcomes, or fostering a positive classroom environment, the topic should align with the broader educational context.

- Relevance to Students’ Needs and Challenges: Effective action research addresses the specific needs and challenges faced by students. Teachers should identify areas where students may be struggling or where improvement is needed, ensuring that the research directly impacts the learning experiences of the students.

- Feasibility and Practicality: The feasibility of the research is crucial. Teachers must choose topics that are practical to implement within the constraints of the classroom setting. This includes considering available resources, time constraints, and the level of support from school administrators.

- Potential for Positive Impact: The ultimate goal of action research is to bring about positive change. Teachers should carefully assess the potential impact of their research, aiming for improvements in teaching methods, student performance, or overall classroom dynamics.

List of Topics for Action Research in the Classroom

- Impact of Mindfulness Practices on Student Focus

- The Effectiveness of Peer Tutoring in Mathematics

- Strategies for Encouraging Critical Thinking in History Classes

- Using Gamification to Enhance Learning in Science

- Investigating the Impact of Flexible Seating Arrangements

- Assessing the Benefits of Project-Based Learning in Language Arts

- The Influence of Classroom Decor on Student Motivation

- Examining the Use of Learning Stations for Differentiation

- Implementing Reflective Journals to Enhance Writing Skills

- Exploring the Impact of Flipped Classroom Models

- Analyzing the Effects of Homework on Student Performance

- The Role of Positive Reinforcement in Classroom Behavior

- Investigating the Impact of Classroom Libraries on Reading Proficiency

- Strategies for Fostering a Growth Mindset in Students

- Assessing the Benefits of Cross-Curricular Integration

- Using Technology to Enhance Vocabulary Acquisition

- The Impact of Outdoor Learning on Student Engagement

- Investigating the Relationship Between Attendance and Academic Success

- The Role of Parental Involvement in Homework Completion

- Assessing the Impact of Classroom Rituals on Community Building

- Strategies for Increasing Student Participation in Discussions

- Exploring the Influence of Classroom Lighting on Student Alertness

- Investigating the Impact of Daily Agendas on Time Management

- The Effectiveness of Socratic Seminars in Social Studies

- Analyzing the Use of Graphic Organizers for Concept Mapping

- Implementing Student-Led Conferences for Goal Setting

- Examining the Effects of Mind Mapping on Information Retention