Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 05 October 2018

Interviews and focus groups in qualitative research: an update for the digital age

- P. Gill 1 &

- J. Baillie 2

British Dental Journal volume 225 , pages 668–672 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

25k Accesses

48 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

Highlights that qualitative research is used increasingly in dentistry. Interviews and focus groups remain the most common qualitative methods of data collection.

Suggests the advent of digital technologies has transformed how qualitative research can now be undertaken.

Suggests interviews and focus groups can offer significant, meaningful insight into participants' experiences, beliefs and perspectives, which can help to inform developments in dental practice.

Qualitative research is used increasingly in dentistry, due to its potential to provide meaningful, in-depth insights into participants' experiences, perspectives, beliefs and behaviours. These insights can subsequently help to inform developments in dental practice and further related research. The most common methods of data collection used in qualitative research are interviews and focus groups. While these are primarily conducted face-to-face, the ongoing evolution of digital technologies, such as video chat and online forums, has further transformed these methods of data collection. This paper therefore discusses interviews and focus groups in detail, outlines how they can be used in practice, how digital technologies can further inform the data collection process, and what these methods can offer dentistry.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Interviews in the social sciences

Eleanor Knott, Aliya Hamid Rao, … Chana Teeger

Professionalism in dentistry: deconstructing common terminology

Andrew Trathen, Sasha Scambler & Jennifer E. Gallagher

A review of technical and quality assessment considerations of audio-visual and web-conferencing focus groups in qualitative health research

Hiba Bawadi, Sara Elshami, … Banan Mukhalalati

Introduction

Traditionally, research in dentistry has primarily been quantitative in nature. 1 However, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in qualitative research within the profession, due to its potential to further inform developments in practice, policy, education and training. Consequently, in 2008, the British Dental Journal (BDJ) published a four paper qualitative research series, 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 to help increase awareness and understanding of this particular methodological approach.

Since the papers were originally published, two scoping reviews have demonstrated the ongoing proliferation in the use of qualitative research within the field of oral healthcare. 1 , 6 To date, the original four paper series continue to be well cited and two of the main papers remain widely accessed among the BDJ readership. 2 , 3 The potential value of well-conducted qualitative research to evidence-based practice is now also widely recognised by service providers, policy makers, funding bodies and those who commission, support and use healthcare research.

Besides increasing standalone use, qualitative methods are now also routinely incorporated into larger mixed method study designs, such as clinical trials, as they can offer additional, meaningful insights into complex problems that simply could not be provided by quantitative methods alone. Qualitative methods can also be used to further facilitate in-depth understanding of important aspects of clinical trial processes, such as recruitment. For example, Ellis et al . investigated why edentulous older patients, dissatisfied with conventional dentures, decline implant treatment, despite its established efficacy, and frequently refuse to participate in related randomised clinical trials, even when financial constraints are removed. 7 Through the use of focus groups in Canada and the UK, the authors found that fears of pain and potential complications, along with perceived embarrassment, exacerbated by age, are common reasons why older patients typically refuse dental implants. 7

The last decade has also seen further developments in qualitative research, due to the ongoing evolution of digital technologies. These developments have transformed how researchers can access and share information, communicate and collaborate, recruit and engage participants, collect and analyse data and disseminate and translate research findings. 8 Where appropriate, such technologies are therefore capable of extending and enhancing how qualitative research is undertaken. 9 For example, it is now possible to collect qualitative data via instant messaging, email or online/video chat, using appropriate online platforms.

These innovative approaches to research are therefore cost-effective, convenient, reduce geographical constraints and are often useful for accessing 'hard to reach' participants (for example, those who are immobile or socially isolated). 8 , 9 However, digital technologies are still relatively new and constantly evolving and therefore present a variety of pragmatic and methodological challenges. Furthermore, given their very nature, their use in many qualitative studies and/or with certain participant groups may be inappropriate and should therefore always be carefully considered. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a detailed explication regarding the use of digital technologies in qualitative research, insight is provided into how such technologies can be used to facilitate the data collection process in interviews and focus groups.

In light of such developments, it is perhaps therefore timely to update the main paper 3 of the original BDJ series. As with the previous publications, this paper has been purposely written in an accessible style, to enhance readability, particularly for those who are new to qualitative research. While the focus remains on the most common qualitative methods of data collection – interviews and focus groups – appropriate revisions have been made to provide a novel perspective, and should therefore be helpful to those who would like to know more about qualitative research. This paper specifically focuses on undertaking qualitative research with adult participants only.

Overview of qualitative research

Qualitative research is an approach that focuses on people and their experiences, behaviours and opinions. 10 , 11 The qualitative researcher seeks to answer questions of 'how' and 'why', providing detailed insight and understanding, 11 which quantitative methods cannot reach. 12 Within qualitative research, there are distinct methodologies influencing how the researcher approaches the research question, data collection and data analysis. 13 For example, phenomenological studies focus on the lived experience of individuals, explored through their description of the phenomenon. Ethnographic studies explore the culture of a group and typically involve the use of multiple methods to uncover the issues. 14

While methodology is the 'thinking tool', the methods are the 'doing tools'; 13 the ways in which data are collected and analysed. There are multiple qualitative data collection methods, including interviews, focus groups, observations, documentary analysis, participant diaries, photography and videography. Two of the most commonly used qualitative methods are interviews and focus groups, which are explored in this article. The data generated through these methods can be analysed in one of many ways, according to the methodological approach chosen. A common approach is thematic data analysis, involving the identification of themes and subthemes across the data set. Further information on approaches to qualitative data analysis has been discussed elsewhere. 1

Qualitative research is an evolving and adaptable approach, used by different disciplines for different purposes. Traditionally, qualitative data, specifically interviews, focus groups and observations, have been collected face-to-face with participants. In more recent years, digital technologies have contributed to the ongoing evolution of qualitative research. Digital technologies offer researchers different ways of recruiting participants and collecting data, and offer participants opportunities to be involved in research that is not necessarily face-to-face.

Research interviews are a fundamental qualitative research method 15 and are utilised across methodological approaches. Interviews enable the researcher to learn in depth about the perspectives, experiences, beliefs and motivations of the participant. 3 , 16 Examples include, exploring patients' perspectives of fear/anxiety triggers in dental treatment, 17 patients' experiences of oral health and diabetes, 18 and dental students' motivations for their choice of career. 19

Interviews may be structured, semi-structured or unstructured, 3 according to the purpose of the study, with less structured interviews facilitating a more in depth and flexible interviewing approach. 20 Structured interviews are similar to verbal questionnaires and are used if the researcher requires clarification on a topic; however they produce less in-depth data about a participant's experience. 3 Unstructured interviews may be used when little is known about a topic and involves the researcher asking an opening question; 3 the participant then leads the discussion. 20 Semi-structured interviews are commonly used in healthcare research, enabling the researcher to ask predetermined questions, 20 while ensuring the participant discusses issues they feel are important.

Interviews can be undertaken face-to-face or using digital methods when the researcher and participant are in different locations. Audio-recording the interview, with the consent of the participant, is essential for all interviews regardless of the medium as it enables accurate transcription; the process of turning the audio file into a word-for-word transcript. This transcript is the data, which the researcher then analyses according to the chosen approach.

Types of interview

Qualitative studies often utilise one-to-one, face-to-face interviews with research participants. This involves arranging a mutually convenient time and place to meet the participant, signing a consent form and audio-recording the interview. However, digital technologies have expanded the potential for interviews in research, enabling individuals to participate in qualitative research regardless of location.

Telephone interviews can be a useful alternative to face-to-face interviews and are commonly used in qualitative research. They enable participants from different geographical areas to participate and may be less onerous for participants than meeting a researcher in person. 15 A qualitative study explored patients' perspectives of dental implants and utilised telephone interviews due to the quality of the data that could be yielded. 21 The researcher needs to consider how they will audio record the interview, which can be facilitated by purchasing a recorder that connects directly to the telephone. One potential disadvantage of telephone interviews is the inability of the interviewer and researcher to see each other. This is resolved using software for audio and video calls online – such as Skype – to conduct interviews with participants in qualitative studies. Advantages of this approach include being able to see the participant if video calls are used, enabling observation of non-verbal communication, and the software can be free to use. However, participants are required to have a device and internet connection, as well as being computer literate, potentially limiting who can participate in the study. One qualitative study explored the role of dental hygienists in reducing oral health disparities in Canada. 22 The researcher conducted interviews using Skype, which enabled dental hygienists from across Canada to be interviewed within the research budget, accommodating the participants' schedules. 22

A less commonly used approach to qualitative interviews is the use of social virtual worlds. A qualitative study accessed a social virtual world – Second Life – to explore the health literacy skills of individuals who use social virtual worlds to access health information. 23 The researcher created an avatar and interview room, and undertook interviews with participants using voice and text methods. 23 This approach to recruitment and data collection enables individuals from diverse geographical locations to participate, while remaining anonymous if they wish. Furthermore, for interviews conducted using text methods, transcription of the interview is not required as the researcher can save the written conversation with the participant, with the participant's consent. However, the researcher and participant need to be familiar with how the social virtual world works to engage in an interview this way.

Conducting an interview

Ensuring informed consent before any interview is a fundamental aspect of the research process. Participants in research must be afforded autonomy and respect; consent should be informed and voluntary. 24 Individuals should have the opportunity to read an information sheet about the study, ask questions, understand how their data will be stored and used, and know that they are free to withdraw at any point without reprisal. The qualitative researcher should take written consent before undertaking the interview. In a face-to-face interview, this is straightforward: the researcher and participant both sign copies of the consent form, keeping one each. However, this approach is less straightforward when the researcher and participant do not meet in person. A recent protocol paper outlined an approach for taking consent for telephone interviews, which involved: audio recording the participant agreeing to each point on the consent form; the researcher signing the consent form and keeping a copy; and posting a copy to the participant. 25 This process could be replicated in other interview studies using digital methods.

There are advantages and disadvantages of using face-to-face and digital methods for research interviews. Ultimately, for both approaches, the quality of the interview is determined by the researcher. 16 Appropriate training and preparation are thus required. Healthcare professionals can use their interpersonal communication skills when undertaking a research interview, particularly questioning, listening and conversing. 3 However, the purpose of an interview is to gain information about the study topic, 26 rather than offering help and advice. 3 The researcher therefore needs to listen attentively to participants, enabling them to describe their experience without interruption. 3 The use of active listening skills also help to facilitate the interview. 14 Spradley outlined elements and strategies for research interviews, 27 which are a useful guide for qualitative researchers:

Greeting and explaining the project/interview

Asking descriptive (broad), structural (explore response to descriptive) and contrast (difference between) questions

Asymmetry between the researcher and participant talking

Expressing interest and cultural ignorance

Repeating, restating and incorporating the participant's words when asking questions

Creating hypothetical situations

Asking friendly questions

Knowing when to leave.

For semi-structured interviews, a topic guide (also called an interview schedule) is used to guide the content of the interview – an example of a topic guide is outlined in Box 1 . The topic guide, usually based on the research questions, existing literature and, for healthcare professionals, their clinical experience, is developed by the research team. The topic guide should include open ended questions that elicit in-depth information, and offer participants the opportunity to talk about issues important to them. This is vital in qualitative research where the researcher is interested in exploring the experiences and perspectives of participants. It can be useful for qualitative researchers to pilot the topic guide with the first participants, 10 to ensure the questions are relevant and understandable, and amending the questions if required.

Regardless of the medium of interview, the researcher must consider the setting of the interview. For face-to-face interviews, this could be in the participant's home, in an office or another mutually convenient location. A quiet location is preferable to promote confidentiality, enable the researcher and participant to concentrate on the conversation, and to facilitate accurate audio-recording of the interview. For interviews using digital methods the same principles apply: a quiet, private space where the researcher and participant feel comfortable and confident to participate in an interview.

Box 1: Example of a topic guide

Study focus: Parents' experiences of brushing their child's (aged 0–5) teeth

1. Can you tell me about your experience of cleaning your child's teeth?

How old was your child when you started cleaning their teeth?

Why did you start cleaning their teeth at that point?

How often do you brush their teeth?

What do you use to brush their teeth and why?

2. Could you explain how you find cleaning your child's teeth?

Do you find anything difficult?

What makes cleaning their teeth easier for you?

3. How has your experience of cleaning your child's teeth changed over time?

Has it become easier or harder?

Have you changed how often and how you clean their teeth? If so, why?

4. Could you describe how your child finds having their teeth cleaned?

What do they enjoy about having their teeth cleaned?

Is there anything they find upsetting about having their teeth cleaned?

5. Where do you look for information/advice about cleaning your child's teeth?

What did your health visitor tell you about cleaning your child's teeth? (If anything)

What has the dentist told you about caring for your child's teeth? (If visited)

Have any family members given you advice about how to clean your child's teeth? If so, what did they tell you? Did you follow their advice?

6. Is there anything else you would like to discuss about this?

Focus groups

A focus group is a moderated group discussion on a pre-defined topic, for research purposes. 28 , 29 While not aligned to a particular qualitative methodology (for example, grounded theory or phenomenology) as such, focus groups are used increasingly in healthcare research, as they are useful for exploring collective perspectives, attitudes, behaviours and experiences. Consequently, they can yield rich, in-depth data and illuminate agreement and inconsistencies 28 within and, where appropriate, between groups. Examples include public perceptions of dental implants and subsequent impact on help-seeking and decision making, 30 and general dental practitioners' views on patient safety in dentistry. 31

Focus groups can be used alone or in conjunction with other methods, such as interviews or observations, and can therefore help to confirm, extend or enrich understanding and provide alternative insights. 28 The social interaction between participants often results in lively discussion and can therefore facilitate the collection of rich, meaningful data. However, they are complex to organise and manage, due to the number of participants, and may also be inappropriate for exploring particularly sensitive issues that many participants may feel uncomfortable about discussing in a group environment.

Focus groups are primarily undertaken face-to-face but can now also be undertaken online, using appropriate technologies such as email, bulletin boards, online research communities, chat rooms, discussion forums, social media and video conferencing. 32 Using such technologies, data collection can also be synchronous (for example, online discussions in 'real time') or, unlike traditional face-to-face focus groups, asynchronous (for example, online/email discussions in 'non-real time'). While many of the fundamental principles of focus group research are the same, regardless of how they are conducted, a number of subtle nuances are associated with the online medium. 32 Some of which are discussed further in the following sections.

Focus group considerations

Some key considerations associated with face-to-face focus groups are: how many participants are required; should participants within each group know each other (or not) and how many focus groups are needed within a single study? These issues are much debated and there is no definitive answer. However, the number of focus groups required will largely depend on the topic area, the depth and breadth of data needed, the desired level of participation required 29 and the necessity (or not) for data saturation.

The optimum group size is around six to eight participants (excluding researchers) but can work effectively with between three and 14 participants. 3 If the group is too small, it may limit discussion, but if it is too large, it may become disorganised and difficult to manage. It is, however, prudent to over-recruit for a focus group by approximately two to three participants, to allow for potential non-attenders. For many researchers, particularly novice researchers, group size may also be informed by pragmatic considerations, such as the type of study, resources available and moderator experience. 28 Similar size and mix considerations exist for online focus groups. Typically, synchronous online focus groups will have around three to eight participants but, as the discussion does not happen simultaneously, asynchronous groups may have as many as 10–30 participants. 33

The topic area and potential group interaction should guide group composition considerations. Pre-existing groups, where participants know each other (for example, work colleagues) may be easier to recruit, have shared experiences and may enjoy a familiarity, which facilitates discussion and/or the ability to challenge each other courteously. 3 However, if there is a potential power imbalance within the group or if existing group norms and hierarchies may adversely affect the ability of participants to speak freely, then 'stranger groups' (that is, where participants do not already know each other) may be more appropriate. 34 , 35

Focus group management

Face-to-face focus groups should normally be conducted by two researchers; a moderator and an observer. 28 The moderator facilitates group discussion, while the observer typically monitors group dynamics, behaviours, non-verbal cues, seating arrangements and speaking order, which is essential for transcription and analysis. The same principles of informed consent, as discussed in the interview section, also apply to focus groups, regardless of medium. However, the consent process for online discussions will probably be managed somewhat differently. For example, while an appropriate participant information leaflet (and consent form) would still be required, the process is likely to be managed electronically (for example, via email) and would need to specifically address issues relating to technology (for example, anonymity and use, storage and access to online data). 32

The venue in which a face to face focus group is conducted should be of a suitable size, private, quiet, free from distractions and in a collectively convenient location. It should also be conducted at a time appropriate for participants, 28 as this is likely to promote attendance. As with interviews, the same ethical considerations apply (as discussed earlier). However, online focus groups may present additional ethical challenges associated with issues such as informed consent, appropriate access and secure data storage. Further guidance can be found elsewhere. 8 , 32

Before the focus group commences, the researchers should establish rapport with participants, as this will help to put them at ease and result in a more meaningful discussion. Consequently, researchers should introduce themselves, provide further clarity about the study and how the process will work in practice and outline the 'ground rules'. Ground rules are designed to assist, not hinder, group discussion and typically include: 3 , 28 , 29

Discussions within the group are confidential to the group

Only one person can speak at a time

All participants should have sufficient opportunity to contribute

There should be no unnecessary interruptions while someone is speaking

Everyone can be expected to be listened to and their views respected

Challenging contrary opinions is appropriate, but ridiculing is not.

Moderating a focus group requires considered management and good interpersonal skills to help guide the discussion and, where appropriate, keep it sufficiently focused. Avoid, therefore, participating, leading, expressing personal opinions or correcting participants' knowledge 3 , 28 as this may bias the process. A relaxed, interested demeanour will also help participants to feel comfortable and promote candid discourse. Moderators should also prevent the discussion being dominated by any one person, ensure differences of opinions are discussed fairly and, if required, encourage reticent participants to contribute. 3 Asking open questions, reflecting on significant issues, inviting further debate, probing responses accordingly, and seeking further clarification, as and where appropriate, will help to obtain sufficient depth and insight into the topic area.

Moderating online focus groups requires comparable skills, particularly if the discussion is synchronous, as the discussion may be dominated by those who can type proficiently. 36 It is therefore important that sufficient time and respect is accorded to those who may not be able to type as quickly. Asynchronous discussions are usually less problematic in this respect, as interactions are less instant. However, moderating an asynchronous discussion presents additional challenges, particularly if participants are geographically dispersed, as they may be online at different times. Consequently, the moderator will not always be present and the discussion may therefore need to occur over several days, which can be difficult to manage and facilitate and invariably requires considerable flexibility. 32 It is also worth recognising that establishing rapport with participants via online medium is often more challenging than via face-to-face and may therefore require additional time, skills, effort and consideration.

As with research interviews, focus groups should be guided by an appropriate interview schedule, as discussed earlier in the paper. For example, the schedule will usually be informed by the review of the literature and study aims, and will merely provide a topic guide to help inform subsequent discussions. To provide a verbatim account of the discussion, focus groups must be recorded, using an audio-recorder with a good quality multi-directional microphone. While videotaping is possible, some participants may find it obtrusive, 3 which may adversely affect group dynamics. The use (or not) of a video recorder, should therefore be carefully considered.

At the end of the focus group, a few minutes should be spent rounding up and reflecting on the discussion. 28 Depending on the topic area, it is possible that some participants may have revealed deeply personal issues and may therefore require further help and support, such as a constructive debrief or possibly even referral on to a relevant third party. It is also possible that some participants may feel that the discussion did not adequately reflect their views and, consequently, may no longer wish to be associated with the study. 28 Such occurrences are likely to be uncommon, but should they arise, it is important to further discuss any concerns and, if appropriate, offer them the opportunity to withdraw (including any data relating to them) from the study. Immediately after the discussion, researchers should compile notes regarding thoughts and ideas about the focus group, which can assist with data analysis and, if appropriate, any further data collection.

Qualitative research is increasingly being utilised within dental research to explore the experiences, perspectives, motivations and beliefs of participants. The contributions of qualitative research to evidence-based practice are increasingly being recognised, both as standalone research and as part of larger mixed-method studies, including clinical trials. Interviews and focus groups remain commonly used data collection methods in qualitative research, and with the advent of digital technologies, their utilisation continues to evolve. However, digital methods of qualitative data collection present additional methodological, ethical and practical considerations, but also potentially offer considerable flexibility to participants and researchers. Consequently, regardless of format, qualitative methods have significant potential to inform important areas of dental practice, policy and further related research.

Gussy M, Dickson-Swift V, Adams J . A scoping review of qualitative research in peer-reviewed dental publications. Int J Dent Hygiene 2013; 11 : 174–179.

Article Google Scholar

Burnard P, Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B . Analysing and presenting qualitative data. Br Dent J 2008; 204 : 429–432.

Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B . Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J 2008; 204 : 291–295.

Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B . Conducting qualitative interviews with school children in dental research. Br Dent J 2008; 204 : 371–374.

Stewart K, Gill P, Chadwick B, Treasure E . Qualitative research in dentistry. Br Dent J 2008; 204 : 235–239.

Masood M, Thaliath E, Bower E, Newton J . An appraisal of the quality of published qualitative dental research. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2011; 39 : 193–203.

Ellis J, Levine A, Bedos C et al. Refusal of implant supported mandibular overdentures by elderly patients. Gerodontology 2011; 28 : 62–68.

Macfarlane S, Bucknall T . Digital Technologies in Research. In Gerrish K, Lathlean J (editors) The Research Process in Nursing . 7th edition. pp. 71–86. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2015.

Google Scholar

Lee R, Fielding N, Blank G . Online Research Methods in the Social Sciences: An Editorial Introduction. In Fielding N, Lee R, Blank G (editors) The Sage Handbook of Online Research Methods . pp. 3–16. London: Sage Publications; 2016.

Creswell J . Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five designs . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998.

Guest G, Namey E, Mitchell M . Qualitative research: Defining and designing In Guest G, Namey E, Mitchell M (editors) Collecting Qualitative Data: A Field Manual For Applied Research . pp. 1–40. London: Sage Publications, 2013.

Chapter Google Scholar

Pope C, Mays N . Qualitative research: Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ 1995; 311 : 42–45.

Giddings L, Grant B . A Trojan Horse for positivism? A critique of mixed methods research. Adv Nurs Sci 2007; 30 : 52–60.

Hammersley M, Atkinson P . Ethnography: Principles in Practice . London: Routledge, 1995.

Oltmann S . Qualitative interviews: A methodological discussion of the interviewer and respondent contexts Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2016; 17 : Art. 15.

Patton M . Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002.

Wang M, Vinall-Collier K, Csikar J, Douglas G . A qualitative study of patients' views of techniques to reduce dental anxiety. J Dent 2017; 66 : 45–51.

Lindenmeyer A, Bowyer V, Roscoe J, Dale J, Sutcliffe P . Oral health awareness and care preferences in patients with diabetes: a qualitative study. Fam Pract 2013; 30 : 113–118.

Gallagher J, Clarke W, Wilson N . Understanding the motivation: a qualitative study of dental students' choice of professional career. Eur J Dent Educ 2008; 12 : 89–98.

Tod A . Interviewing. In Gerrish K, Lacey A (editors) The Research Process in Nursing . Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

Grey E, Harcourt D, O'Sullivan D, Buchanan H, Kipatrick N . A qualitative study of patients' motivations and expectations for dental implants. Br Dent J 2013; 214 : 10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.1178.

Farmer J, Peressini S, Lawrence H . Exploring the role of the dental hygienist in reducing oral health disparities in Canada: A qualitative study. Int J Dent Hygiene 2017; 10.1111/idh.12276.

McElhinney E, Cheater F, Kidd L . Undertaking qualitative health research in social virtual worlds. J Adv Nurs 2013; 70 : 1267–1275.

Health Research Authority. UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research. Available at https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/policies-standards-legislation/uk-policy-framework-health-social-care-research/ (accessed September 2017).

Baillie J, Gill P, Courtenay P . Knowledge, understanding and experiences of peritonitis among patients, and their families, undertaking peritoneal dialysis: A mixed methods study protocol. J Adv Nurs 2017; 10.1111/jan.13400.

Kvale S . Interviews . Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage, 1996.

Spradley J . The Ethnographic Interview . New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979.

Goodman C, Evans C . Focus Groups. In Gerrish K, Lathlean J (editors) The Research Process in Nursing . pp. 401–412. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2015.

Shaha M, Wenzell J, Hill E . Planning and conducting focus group research with nurses. Nurse Res 2011; 18 : 77–87.

Wang G, Gao X, Edward C . Public perception of dental implants: a qualitative study. J Dent 2015; 43 : 798–805.

Bailey E . Contemporary views of dental practitioners' on patient safety. Br Dent J 2015; 219 : 535–540.

Abrams K, Gaiser T . Online Focus Groups. In Field N, Lee R, Blank G (editors) The Sage Handbook of Online Research Methods . pp. 435–450. London: Sage Publications, 2016.

Poynter R . The Handbook of Online and Social Media Research . West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

Kevern J, Webb C . Focus groups as a tool for critical social research in nurse education. Nurse Educ Today 2001; 21 : 323–333.

Kitzinger J, Barbour R . Introduction: The Challenge and Promise of Focus Groups. In Barbour R S K J (editor) Developing Focus Group Research . pp. 1–20. London: Sage Publications, 1999.

Krueger R, Casey M . Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE; 2009.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Senior Lecturer (Adult Nursing), School of Healthcare Sciences, Cardiff University,

Lecturer (Adult Nursing) and RCBC Wales Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Healthcare Sciences, Cardiff University,

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to P. Gill .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gill, P., Baillie, J. Interviews and focus groups in qualitative research: an update for the digital age. Br Dent J 225 , 668–672 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.815

Download citation

Accepted : 02 July 2018

Published : 05 October 2018

Issue Date : 12 October 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.815

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Translating brand reputation into equity from the stakeholder’s theory: an approach to value creation based on consumer’s perception & interactions.

- Olukorede Adewole

International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility (2024)

Perceptions and beliefs of community gatekeepers about genomic risk information in African cleft research

- Abimbola M. Oladayo

- Oluwakemi Odukoya

- Azeez Butali

BMC Public Health (2024)

Assessment of women’s needs, wishes and preferences regarding interprofessional guidance on nutrition in pregnancy – a qualitative study

- Merle Ebinghaus

- Caroline Johanna Agricola

- Birgit-Christiane Zyriax

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2024)

‘Baby mamas’ in Urban Ghana: an exploratory qualitative study on the factors influencing serial fathering among men in Accra, Ghana

- Rosemond Akpene Hiadzi

- Jemima Akweley Agyeman

- Godwin Banafo Akrong

Reproductive Health (2023)

Revolutionising dental technologies: a qualitative study on dental technicians’ perceptions of Artificial intelligence integration

- Galvin Sim Siang Lin

- Yook Shiang Ng

- Kah Hoay Chua

BMC Oral Health (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- July 10, 2023

Conducting In-Depth Interviews in Qualitative Research

In-depth interviews are a cornerstone of qualitative research, providing researchers with the opportunity to explore participants' experiences, perspectives, and emotions in detail. This installment delves into the art of conducting in-depth interviews, offering insights into building rapport, creating a comfortable environment, and eliciting detailed responses.

Building Rapport and Creating Comfort

1. introduction and ice breakers:.

- Start the interview with a friendly introduction and ice breakers to put participants at ease.

- Establish a casual and conversational tone to encourage openness.

2. Active Listening:

- Demonstrate active listening by nodding, making eye contact, and providing verbal affirmations.

- Show genuine interest in participants' responses to foster a sense of trust.

Eliciting Detailed Responses

1. use of probing questions:.

- Incorporate probing questions to delve deeper into participants' responses.

- Ask follow-up questions that encourage reflection and the sharing of specific details.

2. Allowing Silence:

- Embrace moments of silence to give participants the opportunity to collect their thoughts.

- Avoid rushing to fill pauses, as participants may use this time to share more profound insights.

Handling Sensitive Topics

1. establishing ground rules:.

- Set clear ground rules for discussing sensitive topics, ensuring participants feel safe.

- Provide information on confidentiality measures to build trust.

2. Empathetic Responses:

- Respond empathetically to participants' emotions, acknowledging their feelings without judgment.

- Create a supportive environment for participants to share without fear of criticism.

Adapting to Participant Dynamics

1. cultural sensitivity:.

- Be culturally sensitive and aware of potential cultural nuances during the interview.

- Adapt communication styles to align with participants' cultural backgrounds.

2. Flexibility in Approach:

- Remain flexible in your approach, adjusting based on the participant's communication style and preferences.

- Allow participants to guide the conversation to areas they find most meaningful.

Practical Tips for Success

1. pilot interviews:.

- Conduct pilot interviews with a small sample to refine your interview approach.

- Gather feedback from pilot participants to make adjustments before the full study.

2. Transparency about Recording:

- Clearly communicate the recording process to participants and obtain consent.

- Ensure that participants feel comfortable with the recording method used.

Conducting in-depth interviews requires a combination of interpersonal skills, empathy, and methodological rigor. By building rapport, eliciting detailed responses, and adapting to participant dynamics, researchers can unlock valuable insights. In the next part of this series, we'll explore the unique dynamics of phone and video interviews, providing tips for overcoming challenges in virtual interview settings. Stay tuned for more insights into the world of qualitative research interviews!

Get the most out of your research

Create an account and start using Qanda for free

Feature request

Stay up to date

Receive updates on new product features.

© 2024 Qanda. All rights reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Basic Clin Pharm

- v.5(4); September 2014-November 2014

Qualitative research method-interviewing and observation

Shazia jamshed.

Department of Pharmacy Practice, Kulliyyah of Pharmacy, International Islamic University Malaysia, Kuantan Campus, Pahang, Malaysia

Buckley and Chiang define research methodology as “a strategy or architectural design by which the researcher maps out an approach to problem-finding or problem-solving.”[ 1 ] According to Crotty, research methodology is a comprehensive strategy ‘that silhouettes our choice and use of specific methods relating them to the anticipated outcomes,[ 2 ] but the choice of research methodology is based upon the type and features of the research problem.[ 3 ] According to Johnson et al . mixed method research is “a class of research where the researcher mixes or combines quantitative and qualitative research techniques, methods, approaches, theories and or language into a single study.[ 4 ] In order to have diverse opinions and views, qualitative findings need to be supplemented with quantitative results.[ 5 ] Therefore, these research methodologies are considered to be complementary to each other rather than incompatible to each other.[ 6 ]

Qualitative research methodology is considered to be suitable when the researcher or the investigator either investigates new field of study or intends to ascertain and theorize prominent issues.[ 6 , 7 ] There are many qualitative methods which are developed to have an in depth and extensive understanding of the issues by means of their textual interpretation and the most common types are interviewing and observation.[ 7 ]

Interviewing

This is the most common format of data collection in qualitative research. According to Oakley, qualitative interview is a type of framework in which the practices and standards be not only recorded, but also achieved, challenged and as well as reinforced.[ 8 ] As no research interview lacks structure[ 9 ] most of the qualitative research interviews are either semi-structured, lightly structured or in-depth.[ 9 ] Unstructured interviews are generally suggested in conducting long-term field work and allow respondents to let them express in their own ways and pace, with minimal hold on respondents’ responses.[ 10 ]

Pioneers of ethnography developed the use of unstructured interviews with local key informants that is., by collecting the data through observation and record field notes as well as to involve themselves with study participants. To be precise, unstructured interview resembles a conversation more than an interview and is always thought to be a “controlled conversation,” which is skewed towards the interests of the interviewer.[ 11 ] Non-directive interviews, form of unstructured interviews are aimed to gather in-depth information and usually do not have pre-planned set of questions.[ 11 ] Another type of the unstructured interview is the focused interview in which the interviewer is well aware of the respondent and in times of deviating away from the main issue the interviewer generally refocuses the respondent towards key subject.[ 11 ] Another type of the unstructured interview is an informal, conversational interview, based on unplanned set of questions that are generated instantaneously during the interview.[ 11 ]

In contrast, semi-structured interviews are those in-depth interviews where the respondents have to answer preset open-ended questions and thus are widely employed by different healthcare professionals in their research. Semi-structured, in-depth interviews are utilized extensively as interviewing format possibly with an individual or sometimes even with a group.[ 6 ] These types of interviews are conducted once only, with an individual or with a group and generally cover the duration of 30 min to more than an hour.[ 12 ] Semi-structured interviews are based on semi-structured interview guide, which is a schematic presentation of questions or topics and need to be explored by the interviewer.[ 12 ] To achieve optimum use of interview time, interview guides serve the useful purpose of exploring many respondents more systematically and comprehensively as well as to keep the interview focused on the desired line of action.[ 12 ] The questions in the interview guide comprise of the core question and many associated questions related to the central question, which in turn, improve further through pilot testing of the interview guide.[ 7 ] In order to have the interview data captured more effectively, recording of the interviews is considered an appropriate choice but sometimes a matter of controversy among the researcher and the respondent. Hand written notes during the interview are relatively unreliable, and the researcher might miss some key points. The recording of the interview makes it easier for the researcher to focus on the interview content and the verbal prompts and thus enables the transcriptionist to generate “verbatim transcript” of the interview.

Similarly, in focus groups, invited groups of people are interviewed in a discussion setting in the presence of the session moderator and generally these discussions last for 90 min.[ 7 ] Like every research technique having its own merits and demerits, group discussions have some intrinsic worth of expressing the opinions openly by the participants. On the contrary in these types of discussion settings, limited issues can be focused, and this may lead to the generation of fewer initiatives and suggestions about research topic.

Observation

Observation is a type of qualitative research method which not only included participant's observation, but also covered ethnography and research work in the field. In the observational research design, multiple study sites are involved. Observational data can be integrated as auxiliary or confirmatory research.[ 11 ]

Research can be visualized and perceived as painstaking methodical efforts to examine, investigate as well as restructure the realities, theories and applications. Research methods reflect the approach to tackling the research problem. Depending upon the need, research method could be either an amalgam of both qualitative and quantitative or qualitative or quantitative independently. By adopting qualitative methodology, a prospective researcher is going to fine-tune the pre-conceived notions as well as extrapolate the thought process, analyzing and estimating the issues from an in-depth perspective. This could be carried out by one-to-one interviews or as issue-directed discussions. Observational methods are, sometimes, supplemental means for corroborating research findings.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

In-depth Interviews: Definition and how to conduct them

Online surveys, user review sites and focus groups can be great methods for collecting data. However, another method of gathering data that is sometimes overlooked are the in-depth interviews.

All of these methods can be used in your comprehensive customer experience management strategy, but in-depth interviews can help you collect data that can offer rich insights into your target audience’s experience and preferences from a broad sample.

In this article you will discover the main characteristics of in-depth interviews as a great tool for your qualitative research and gather better insights from your objects of study.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

What are in-depth interviews?

In-depth interviews are a qualitative data collection method that allows for the collection of a large amount of information about the behavior, attitude and perception of the interviewees.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

During in-depth interviews, researchers and participants have the freedom to explore additional points and change the direction of the process when necessary. It is an independent research method that can adopt multiple strategies according to the needs of the research.

Characteristics of in-depth interviews

There are many types of interviews , each with its particularities, in this case the most important characteristics of in-depth interviews are:

- Flexible structure: Although it is not very structured, it covers a few topics based on a guide, which allows the interviewer to cover areas appropriate for the interviewee.

- Interactive: The interviewer processes the material that is produced during the interview. During the interaction the interviewer poses initial questions in a positive manner, so that the respondent is encouraged to answer. The complete process is very human, and so less mundane and dull.

- Deep: Many probing techniques are used in in-depth interviews, so that results are understood through exploration and explanation. The interviewer asks follow-up questions to gain a deeper perspective and understand the participant’s viewpoint.

- Generative: Often interacting with your target audience creates new knowledge. For instance, if you are talking to your customers, you learn more about the purchase behavior. Researchers and participants present ideas for a specific topic and solutions to the problems posed.

To learn more about the characteristics of in-depth interviews, check out our blog on interview questions .

Importance of conducting in-depth interviews

As an in-depth interview is a one-on-one conversation, you get enough opportunities to get to the root causes of likes/dislikes, perceptions, or beliefs.

Generally, questions are open-ended questions and can be customized as per the particular situation. You can use single ease questions . A single-ease question is a straightforward query that elicits a concise and uncomplicated response. The interviewer gets an opportunity to develop a rapport with the participant, thereby making them feel comfortable. Thus, they can bring out honest feedback and also note their expressions and body language. Such cues can amount to rich qualitative data.

LEARN ABOUT: Selection Bias

With surveys, there are chances that the respondents may select answers in a rush, but in case of in-depth interviews it’s hardly the worry of researchers.

Conversations can prove to be an excellent method to collect data. In fact, people might be reluctant to answer questions in written format, but given the nature of an interview, participants might agree giving information verbally. You can also discuss with the interviewees if they want to keep their identity confidential.

In-depth interviews are aimed at uncovering the issues in order to obtain detailed results. This method allows you to gain insight into the experiences, feelings and perspectives of the interviewees.

When conducting the initial stage of a large research project, in-depth interviews prove to be useful to narrow down and focus on important research details.

When you want to have the context of a problem, in-depth interviews allow you to evaluate different solutions to manage the research process while assisting in in-depth data analysis .

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

Steps to conduct in-depth interviews

- Obtain the necessary information about the respondents and the context in which they operate.

- Make a script or a list of topics you want to cover. This will make it easy to add secondary questions.

- Schedule an interview at a time and date of the respondent’s choice.

- Ask questions confidently and let the interviewees feel comfortable, so that they too are confident and can answer difficult questions with ease.

- Set a maximum duration such that it doesn’t feel exhaustive.

- Observe and make notes on the interviewee’s body expressions and gestures.

- It is important to maintain ethics throughout the process.

- Transcribe the recordings and verify them with the interviewee.

Advantages of in-depth interviews

The benefits of conducting an in-depth interview include the following:

- They allow the researcher and participants to have a comfortable relationship to generate more in-depth responses regarding sensitive topics.

- Researchers can ask follow-up questions , obtain additional information, and return to key questions to gain a better understanding of the participants’ attitudes.

- The sampling is more accurate than other data collection methods .

- Researchers can monitor changes in tone and word choice of participants to gain a better understanding of opinions.

- Fewer participants are needed to obtain useful information.

- In-depth interviews can be very beneficial when a detailed report on a person’s opinion and behavior is needed. In addition, it explores new ideas and contexts that give the researcher a complete picture of the phenomena that occurred.

Disadvantages

The disadvantages of in-depth interviews are:

- They are time-consuming, as they must be transcribed, organized, analyzed in detail.

- If the interviewer is inexperienced, it affects the complete process.

- It is a costly research method compared to other methods.

- Participants must be chosen carefully to avoid bias, otherwise it can lengthen the process.

- Generally, participants decide to collaborate only when they receive an incentive in return.

LEARN ABOUT: Self-Selection Bias

What is the purpose of in-depth interviews?

The main purpose of in-depth interviews is to understand the consumer behavior and make well-informed decisions. Organizations can formulate their marketing strategies based on the information received from the respondents. They can also gain insights into the probable demand and know consumer pulse.

In the case of B2B businesses, researchers can understand the demand in more detail and can ask questions targeted for the experts. Interviews offer a chance to understand the customer’s thought process and design products that have higher chances of being accepted in the market.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

Final words

An in-depth interview should follow all the steps of the process to collect meaningful data. Hope this blog helps you decide whether you should conduct a detailed interview with your target audience, keeping in mind the pros and cons of it.

If you want to get started with conducting research online, we suggest using an online survey software that offers features like designing a questionnaire , customized look and feel, distributing to your contacts and data analytics. Create an account with QuestionPro Surveys and explore the tool. If you need any help with research or data collection, feel free to connect with us.

Create a free account

MORE LIKE THIS

10 Quantitative Data Analysis Software for Every Data Scientist

Apr 18, 2024

11 Best Enterprise Feedback Management Software in 2024

17 Best Online Reputation Management Software in 2024

Apr 17, 2024

Top 11 Customer Satisfaction Survey Software in 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Sign up today for O*Academy’s Design Research Mastery Course

- UX Research & UX Design

- UX Staff Augmentation

- Service Design

- Design Workshops

- Case Studies

- Why Outwitly?

- Outwitly Team

- Diversity, Equality and Inclusion

Design Research Methods: In-Depth Interviews

In our new three-part blog series, we introduce our favourite qualitative research methods and strategies that you can immediately start applying to your human-centered design projects.

We cover the following design research methods:

In-Depth Interviews (in this post)

Contextual Observations , and

Diary Studies

Do you want to conduct better interviews?

We help you navigate in-depth interviews for your users and customers. We’ll explore how to plan and execute a stellar interview, and we’ll outline our Top 7 Tips for In-Depth Interviewers.

What are in-depth interviews?

In-depth interviews are one of the most common qualitative research methods used in design thinking and human-centered design processes. They allow you to gather a lot of information at once, with relative logistical ease. In-depth interviews are a form of ethnographic research, where researchers observe participants in their real-life environment. They are most effective when conducted in a one-on-one setting.

How and when can you use interviews?

In-depth interviews are best deployed during the Discovery phase of the Human-Centered Design (HCD) process . They are an opportunity to explore and a chance to uncover your user’s needs and challenges. Do you want to find out where they are struggling the most with your service? Now is the time to ask.

Logistics for In-Depth Interviews

Here are our top tips for planning out the logistics for your interviews:

Recruiting: Properly recruiting for interviews is a crucial step, and it can sometimes be the most challenging part of the process. Recruitment can either be handled by the client or in-house, and sometimes by an external recruiting firm. You’ll identify the demographics and characteristics of your different user groups as a first step (e.g. by gender, age, occupation, etc.), and then you’ll ideally find 4-6 interview participants that match your recruiting criteria.

Scheduling: Outwitly uses a scheduling tool called Calendly to schedule all of our interviews. This handy platform syncs directly with our internal calendars, and it will even hook-up to our web-conferencing tool to send call information directly to the participant.

Format: Interviews can be conducted in-person or remotely over the phone, or a combination of the two. An advantage to conducting in-person interviews is that they allow for easier rapport-building, and you’re able to more fully understand the context of how your participant may interact with the product, service, or organization, as well as a holistic picture of their lives. The advantage to remote interviews is that they are easier to schedule and recruit for, and they can really be conducted from anywhere with a cell signal or a WiFi connection. Ideally, you are able to do a mix of both interview types, or you’re able to use remote interviewing in conjunction with another research method, like observations.

Duration: The sweet spot for in-depth interview length is between 45–90 minutes. This depends on how many research themes and questions you have, and of course, your participant’s schedule. Anything over 90 minutes can be very draining for both you and the participant.

Note-Taking: When possible (and with the participant’s consent), it’s best to audio record interviews. This way you are not scrambling to keep up with your hand-written notes, and you are able to fully engage with the participant and listen closely. At Outwitly, we use manual audio recorders, but the iPhone Voice Record Pro app is also an option for in-person interviews. For remote interviewing, you might opt to use call recording software; we like to use the built-in recording feature of GoToMeeting , which is our preferred web-conference platform. Once audio recordings have been collected, we typically get the recordings transcribed using services like Rev.com . This saves a lot of time during the data analysis phase.

Interview Protocol: Before running a set of interviews, it’s important to prepare an ‘interview protocol.’ A protocol is the combination of two things:

1) An introductory script about the research and what the participant can expect from the interview. This is also the time to ask consent for recording and to assure participants that their names and everything they say will be kept confidential.

7 Tips for In-Depth Interviewers

Interviewing is an art form, and it requires a high level of emotional intelligence. You need to be in tune with how comfortable your interviewee/research participant feels, and enable them to open up to you–a complete stranger–about their challenges. Research can sometimes involve particularly sensitive subjects like weight management, divorce, personal finances, and more, so rapport-building (Tip #4) is especially crucial for successful interviewing. Here are our Top 7 best practices for interviewers.

Active Listening: The best skill an interviewer can foster is their listening ability. In a strong interview, the interviewer is not interrupting, bringing up their own anecdotes, or asking too many questions. While some of these “what-not-to-do’s” can actually be helpful to make the participant feel comfortable, too many can derail the interview and also lead the participant to certain answers (as discussed in Tip #3). The interview should flow naturally, and you should mostly allow for the participant to lead the conversation. You’ll want to be listening to them, and when appropriate, repeating key points back to them to reiterate that you are actively listening. Asking a question like “I heard you say your biggest challenges are XYZ. Is there anything else?” shows the participants that you are interested in what they are saying, and it encourages them to keep sharing.

Probing: ‘Probing’ in the context of in-depth interviews refers to diving deeper on a particular response or topic. Typically, you will have prepared your interview protocol with a list of questions and sub-questions–the latter are your probing questions. For example, you might begin with an open-ended, general question, and as your participant replies, you might ask subsequent questions that encourage them to keep digging into the subject. A good interviewer also knows when to continue probing on a subject–and when to move on.

Non-Leading: Learn not to ask leading questions. A leading question is one in which you are making an assumption in the way your question is phrased. This can influence how your participant answers the question. For example, if you ask a participant “What challenges do you have with XYZ?”, you are assuming there are challenges, which may skew the participants response. They may not have any challenges to begin with, but they might reply that there were challenges anyway to fit the question. A better way to ask that question would be: “What challenges, if any, have you had with XYZ?” When prepping the interview protocol, be careful not to draft leading questions. And in the heat of the moment if you go off-script, you’ll need to think about how you’re phrasing your questions.

Building Rapport: Learning to build rapport is one of the most important skills to cultivate as an interviewer. By ensuring your participants feel comfortable, they are much more likely to open up to you. Remember to always be friendly and courteous in your communication prior to conducting the interview (e.g. in emails you send regarding scheduling). In the interview, use a tone of voice that is soft and inquisitive, as well as understanding. Introduce yourself as the researcher and explain the research to the participant. Emphasize that you are there to learn about them, and to understand their needs and how the product, service, or organization they are interacting with could be improved to suit them. During the interview, if you hear in their tone of voice that something in their experience was very frustrating, use language to acknowledge that, by saying “It sounds like that was very frustrating” or “I understand” to let them know that you are on their side. Also, reassure them throughout the interview that their feedback is very useful and helpful by saying things like “Thank you – that’s very interesting,” or “I’ve heard that before from others, you are not the only one!”

Agility & Go-with-the-Flow Attitude: You can prepare, rehearse, and write your interview protocol, but in every interview you will have to be agile. For example, if you’ve separated your interview questions into sections, and the participant naturally starts talking about a topic that you have written down for a later portion of the interview, you should freely move down to those questions and jump back to where you were afterwards. This way, the interview will feel more organic and conversational, and less robotic. Flexibility is also critical because some participants just do not have a lot to say. In these cases, you’ll be required to think of more “off the cuff” questions, or you’ll need to reconsider whether the interview is still a valuable use of your time and theirs. Knowing when to cut an interview short is also an important skill. For the most part, let the participant lead the conversation, feel comfortable jumping around a little in your protocol, and listen to them to know what other questions you could ask that might not be in the protocol. Also, know when to skip a question if you’ve already gotten a response elsewhere in the interview.

Facilitate & Guide: Sometimes interviews will be easy and they’ll naturally follow the flow of your interview protocol. And sometimes they’ll be more challenging, especially if an interviewee is particularly passionate about one topic. In this case, you’ll need to guide your participants as much as possible, so that you can move through more of your questions. This is a delicate balance of listening, finding a time to cut in, and using transitional phrases like “That’s very helpful. I’m mindful of the time, and I would like to ask you some questions about XYZ.”

Comfort with Discomfort: It can sometimes be difficult for participants to answer a question quickly in an interview. They might need to think about their answer before responding. Or they may be able to answer quickly, but there might be things in the back of their mind related to the question that might take a minute for them to recall. It’s important to allow interviewees that space to think about the question. From a human perspective, leaving open silence can feel awkward, but it’s important to create space for the participant to remember anything else that might be important. So while you might be sitting there thinking “wow this is awkward,” they are actually just thinking about their answer. On the flip side, you also don’t want to leave too much space in case there is nothing else to add–this can in turn make participants feel insecure that they have not said enough. Perfecting this skill comes with a lot of experience, so for now, try counting to 10, or perhaps mention that you need a few seconds to catch-up on your note taking–this gives them the space to think longer without feeling too much time pressure. Of course, if nothing more comes up, just feel free to move on.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Outwitly | UX & Service Design (@outwitly)

Click through to download your copy now…

Next in our Research Methods blog series, we walk you through best practices for conducting observations and shadowing as part of your research and design process.

Resources we like…

Calendly for Scheduling

GotoMeeting for Remote Interviewing

iPhone Voice Record Pro app for Audio Recording

Rev for Audio Transcription

Similar blog posts you might like...

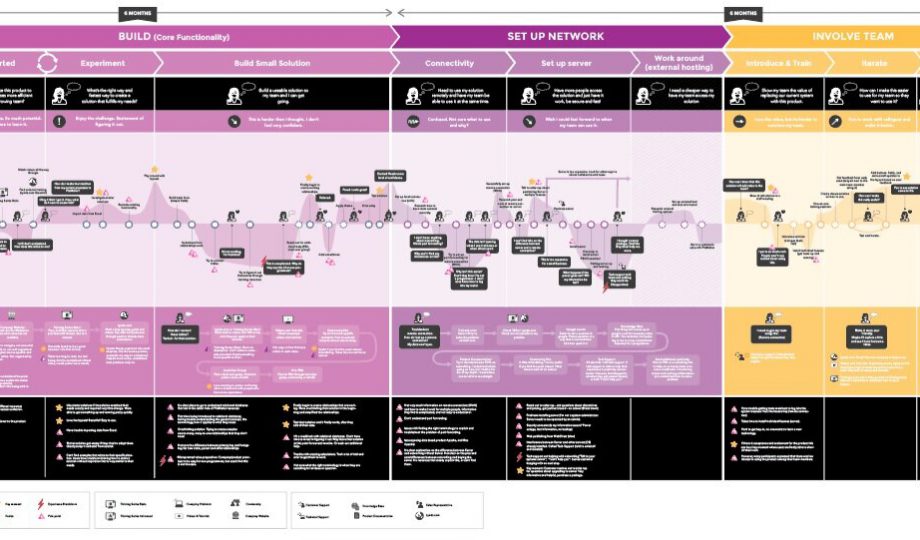

Making your Journey Map Actionable and Creating Change: 301

The New Outwitly Blog: Design, Research, and Storytelling

Design Research Methods: Diary Study

How to Plan and Conduct a Virtual Empathy Mapping Workshop

Subscribe to the weekly wit, what you’ll get.

- Hot remote industry jobs

- Blogs, podcasts, and worthwhile resources

- Free ebooks, webinars, and mini-courses

- Tips from the brightest minds in design

Ready to conduct user interviews like a pro?

Download our free user interview workbook.

- Get in touch

- Enterprise & IT

- Banking & Financial Services

- News media & Entertainment

- Healthcare & Lifesciences

- Networks and Smart Devices

- Education & EdTech

- Service Design

- UI UX Design

- Data Visualization & Design

- User & Design Research

- In the News

- Our Network

- Voice Experiences

- Golden grid

- Critical Thinking

- Enterprise UX

- 20 Product performance metrics

- Types of Dashboards

- Interconnectivity and iOT

- Healthcare and Lifesciences

- Airtel XStream

- Case studies

Data Design

- UCD vs. Design Thinking

User & Design Research

In-depth interviews.

In-depth interviews involve direct engagement with individual participants. It is a qualitative data collection method where the interviewer can ask the participants different questions based on their responses. In-depth interviews require the interviewer to be highly skilled at such data collection methods to ensure that the participants feel comfortable in sharing information authentically, that there is no data lost in the process and the quality of information collected is in-depth and thorough.

Quick details: In-depth Interviews

Structure: Unstructured, Semi-structured

Preparation: Topics, Participant recruitment

Deliverables: Transcripts, Notes, Documentation

More about In-depth interviews

The interviewer is also required to be fairly empathetic to individual participants during the one-to-one engagement. Again, the choice of location is important in the level of comfort the participants may experience. For example, a participant may feel more at ease in their own home versus at a new unfamiliar space.

In-depth interviews prove to be highly helpful in situations where individual participants emotions, sentiments, opinions, values, etc. are an important part of the study or research being conducted. The duration of interview for individual participants may be different, the questions may vary depending on responses and therefore this method is fairly flexible in terms of its design. In-depth interviews may be conducted with a small groups as otherwise the interviews would be time-consuming.

Advantages of In-depth Interviews

1. empathy & connection.

The researcher can give his/her undivided attention to the participants as well as connect with individual participants uniquely. This can allow the participants to feel comfortable during the interview while being authentic as well as open about the situation or issues being discussed.

2. Rich Data Collection

Many researchers use pre-existing lists of participants for methods such as focus and unfocus groups. However, in the case of in-depth interviews, because the sample size of participants is small, usually individuals are picked randomly to get a better and generalized picture of responses. Also, as the interviewer can adapt based on participant responses, the quality of responses are high level.

3. No peer pressure

As in-depth interviews are one-on-one, there is no worry about individuals getting peer-pressured into a response that they don’t entirely agree with.

4. Simple Logistics

As individual interviews are scheduled either at a fixed location, both at the individual’s home or the research facility, and with fewer individuals being interviewed, the logistics planning and scheduling is pretty straightforward.

5. Comprehensive findings

As the participants are interviewed with the same objectives in mind, the interviewer can probe them to as much depth as desired. Again, all responses are recorded unlike email/online surveys where some individuals may not respond and focus groups where a few participants may not contribute to the discussion.

6. Deeper Insights

As the interviews are not strictly time bound, in-depth interviews allow participants to share their feelings, opinions, and attitude in greater depth as well as at length. An observant researcher can interpret the participant’s mood from their body language as well as tone of voice.

7. Quicker realization of goals

With the right participants and an experienced researcher, the path to the goals of the study can be reached quickly.

Disadvantages of In-depth interviews

1. time consuming.

In-depth interviews are quite time consuming, as interviews must be documented, analyzed and findings must be reported.

2. Experienced researcher

If the interviewer is not experienced then the entire research could get jeopardized. Again, this can sometimes drive the costs up by employing more number of researchers to one research.

3. Relatively Costly

The process can be relatively costly compared to other methods.

4. Participant recruitment

Participants must carefully chosen and this can lead to recruitment process which is time consuming. Sometimes, a background check of the participants is required to ensure authenticity but involves an additional time and cost factor.

Think Design's recommendation

Use In-depth interviews as a method when your research question needs deep probing and requires one-to-one interaction with participants. It is a qualitative research method and needs highly qualified researcher to ask relevant questions, moderate the interview and derive insights out of it.

Do not use in-depth interviews when you are seeking quantitative data or what you want is an evidence of responses. This method requires deep understanding of cultural and psychological context of the user and responses need interpretation.

Was this Page helpful?

Related methods.

- Card Sorting

- Concurrent Probing

- Contextual Inquiry

- Dyads & Triads

- Extreme User Interviews

- Fly On The Wall

- Focus Groups

- Personal Inventory

- Retrospective Probing

- Unfocus Group

- User Testing/ Validation

- Word Concept Association

UI UX DESIGN

Service design.

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue we'll assume that you accept this. Learn more

Recent Tweets

Sign up for our newsletter.

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated with the latest insights in UX, CX, Data and Research.

Get in Touch

Thank you for subscribing.

You will be receive all future issues of our newsletter.

Thank you for Downloading.

One moment….

While the report downloads, could you tell us…

Exploring the knowledge and skills for effective family caregiving in elderly home care: a qualitative study

- Open access

- Published: 15 April 2024

- Volume 24 , article number 342 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Gebrezabher Niguse Hailu 1 ,

- Muntaha Abdelkader 1 ,

- Feven Asfaw 1 &

- Hailemariam Atsbeha Meles 2

90 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Family caregivers play a crucial role in providing physical, emotional, and social support to the elderly, allowing them to maintain their independence and stay in their preferred living environment. However, family caregivers face numerous challenges and require specific knowledge and skills to provide effective care. Therefore, understanding the knowledge and skills required for effective family caregiving in elderly home care is vital to support both the caregivers and the elderly recipients.