- Student Services

- Faculty Services

Peer Review and Primary Literature: An Introduction: Is it Primary Research? How Do I Know?

- Scholarly Journal vs. Magazine

- Peer Review: What is it?

- Finding Peer-Reviewed Articles

- Primary Journal Literature

- Is it Primary Research? How Do I Know?

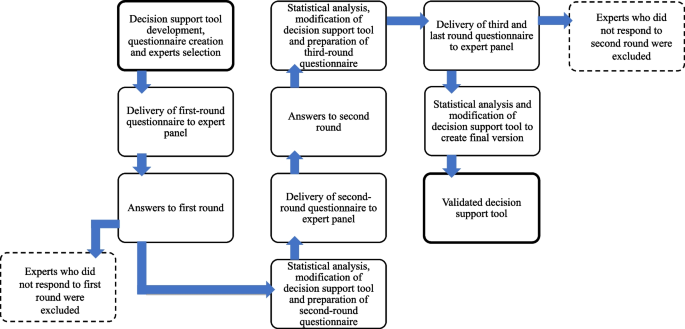

Components of a Primary Research Study

As indicated on a previous page, Peer-Reviewed Journals also include non -primary content. Simply limiting your search results in a database to "peer-reviewed" will not retrieve a list of only primary research studies.

Learn to recognize the parts of a primary research study. Terminology will vary slightly from discipline to discipline and from journal to journal. However, there are common components to most research studies.

When you run a search, find a promising article in your results list and then look at the record for that item (usually by clicking on the title). The full database record for an item usually includes an abstract or summary--sometimes prepared by the journal or database, but often written by the author(s) themselves. This will usually give a clear indication of whether the article is a primary study. For example, here is a full database record from a search for family violence and support in SocINDEX with Full Text :

Although the abstract often tells the story, you will need to read the article to know for sure. Besides scanning the Abstract or Summary, look for the following components: (I am only capturing small article segments for illustration.)

Look for the words METHOD or METHODOLOGY . The authors should explain how they conducted their research.

NOTE: Different Journals and Disciplines will use different terms to mean similar things. If instead of " Method " or " Methodology " you see a heading that says " Research Design " or " Data Collection ," you have a similar indicator that the scholar-authors have done original research.

Look for the section called RESULTS . This details what the author(s) found out after conducting their research.

Charts , Tables , Graphs , Maps and other displays help to summarize and present the findings of the research.

A Discussion indicates the significance of findings, acknowledges limitations of the research study, and suggests further research.

References , a Bibliography or List of Works Cited indicates a literature review and shows other studies and works that were consulted. USE THIS PART OF THE STUDY! If you find one or two good recent studies, you can identify some important earlier studies simply by going through the bibliographies of those articles.

A FINAL NOTE: If you are ever unclear about whether a particular article is appropriate to use in your paper, it is best to show that article to your professor and discuss it with them. The professor is the final judge since they will be assigning your grade.

Subject Guide

- << Previous: Primary Journal Literature

- Last Updated: Nov 16, 2022 12:46 PM

- URL: https://suffolk.libguides.com/PeerandPrimary

Main Navigation Menu

Peer-review and primary research.

- Getting Started With Peer-Reviewed Literature

Primary Research

Identifying a primary research article.

- Finding Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles

- Finding Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

- Evaluating Scholarly Articles

- Google Scholar

- Tips for Reading Journal Articles

STEM Librarian

Primary research or a primary study refers to a research article that is an author’s original research that is almost always published in a peer-reviewed journal. A primary study reports on the details, methods and results of a research study. These articles often have a standard structure of a format called IMRAD, referring to sections of an article: Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion. Primary research studies will start with a review of the previous literature, however, the rest of the article will focus on the authors’ original research. Literature reviews can be published in peer-reviewed journals, however, they are not primary research.

Primary studies are part of primary sources but should not be mistaken for primary documents. Primary documents are usually original sources such as a letter, a diary, a speech or an autobiography. They are a first person view of an event or a period. Typically, if you are a Humanities major, you will be asked to find primary documents for your paper however, if you are in Social Sciences or the Sciences you are most likely going to be asked to find primary research studies. If you are unsure, ask your professor or a librarian for help.

A primary research or study is an empirical research that is published in peer-reviewed journals. Some ways of recognizing whether an article is a primary research article when searching a database:

1. The abstract includes a research question or a hypothesis, methods and results.

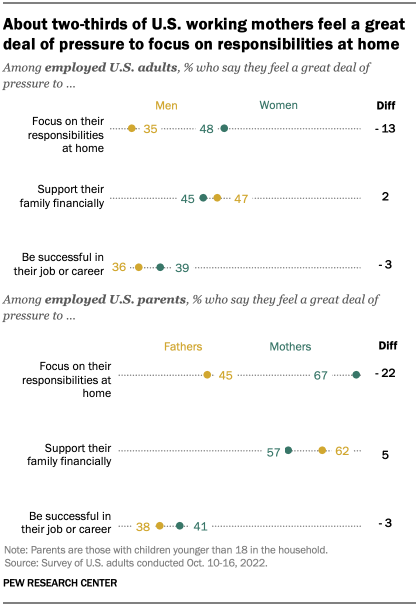

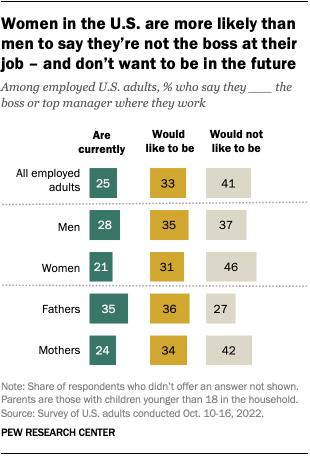

2. Studies can have tables and charts representing data findings.

3. The article includes a section for "methods” or “methodology” and "results".

4. Discussion section indicates findings and discusses limitations of the research study, and suggests further research.

5. Check the reference section because it will refer you to the studies and works that were consulted. You can use this section to find other studies on that particular topic.

The following are not to be confused with primary research articles:

- Literature reviews

- Meta-analyses or systematic reviews (these studies make conclusions based on research on many other studies)

- << Previous: Getting Started With Peer-Reviewed Literature

- Next: Finding Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles >>

- Last Updated: Feb 15, 2024 2:45 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucmo.edu/peerreview

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Primary Research

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Note: This page offers a brief primer on primary research. For more information, see our dedicated set of pages on this topic .

Research isn't limited to finding published material on the Internet or at the library. Many topics you choose to write on may not already have been covered by an abundance of sources and hence may require a different kind of approach to conducting research. This approach involves collecting information directly from the world around you and can include interviews, observations, surveys, and experiments. These strategies are collectively called primary research.

For example, if you are writing about a problem specific to your school or local community, you may need to conduct primary research. You may be able to find secondary sources (such as those found at the library or online) on the more general topic you are pursuing, but may not find specifics on your school or town. To supplement this lack of sources, you can collect data on your own.

For example, Briel wants to research a proposed smoking ban in public establishments in Lafayette, Indiana. Briel begins by going to the library and then searching online. She finds information related to smoking bans in other cities around the United States, but only a few limited articles from the local newspaper on the ban proposed in Lafayette. To supplement this information, she decides to survey twenty local residents to learn what they think of the proposed smoking ban. She also decides to interview two local business owners to learn how they think the ban may affect their businesses. Finally, Briel attends and observes a town hall meeting where the potential ban is discussed.

Many different types of primary research exist. Some common types used in writing classes and beyond include:

- Interviews: A conversation between two or more people in which one person (the interviewer) asks a series of questions to another person or persons (the interviewee). See also our page on interviewing .

- Surveys and questionnaires: A process of gathering specific information from people in a systematic way with a set series of questions. Survey questions usually have pre-specified or short responses. See also our introduction to writing surveys .

- Observations: Careful viewing and documenting of the world around you. See also our page on performing observations .

Primary Research Articles

- Library vs. Google

- Background Reading

- Keyword Searching

- Evaluating Sources

- Citing Sources

- Need more help?

How Can I Find Primary Research Articles?

Many of the recommended databases in this subject guide contain primary research articles (also known as empirical articles or research studies). Search in databases like ScienceDirect and MEDLINE .

Primary Research Articles: How Will I Know One When I See One?

Primary research articles to conduct and publish an experiment or research study, an author or team of authors designs an experiment, gathers data, then analyzes the data and discusses the results of the experiment. a published experiment or research study will therefore look very different from other types of articles (newspaper stories, magazine articles, essays, etc.) found in our library databases. the following guidelines will help you recognize a primary research article, written by the researchers themselves and published in a scholarly journal., structure of a primary research article typically, a primary research article has the following sections:.

- The author summarizes her article

- The author discusses the general background of her research topic; often, she will present a literature review, that is, summarize what other experts have written on this particular research topic

- The author describes the study she designed and conducted

- The author presents the data she gathered during her experiment

- The author offers ideas about the importance and implications of her research findings, and speculates on future directions that similar research might take

- The author gives a References list of sources she used in her paper

The structure of the article will often be clearly shown with headings: Introduction, Method, Results, Discussion.

A primary research article will almost always contains statistics, numerical data presented in tables. Also, primary research articles are written in very formal, very technical language.

- << Previous: Resources

- Next: Research Tips >>

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 4:22 PM

- URL: https://libguides.umgc.edu/science

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.1 Formatting a Research Paper

Learning objectives.

- Identify the major components of a research paper written using American Psychological Association (APA) style.

- Apply general APA style and formatting conventions in a research paper.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use APA style , the documentation and formatting style followed by the American Psychological Association, as well as MLA style , from the Modern Language Association. There are a few major formatting styles used in academic texts, including AMA, Chicago, and Turabian:

- AMA (American Medical Association) for medicine, health, and biological sciences

- APA (American Psychological Association) for education, psychology, and the social sciences

- Chicago—a common style used in everyday publications like magazines, newspapers, and books

- MLA (Modern Language Association) for English, literature, arts, and humanities

- Turabian—another common style designed for its universal application across all subjects and disciplines

While all the formatting and citation styles have their own use and applications, in this chapter we focus our attention on the two styles you are most likely to use in your academic studies: APA and MLA.

If you find that the rules of proper source documentation are difficult to keep straight, you are not alone. Writing a good research paper is, in and of itself, a major intellectual challenge. Having to follow detailed citation and formatting guidelines as well may seem like just one more task to add to an already-too-long list of requirements.

Following these guidelines, however, serves several important purposes. First, it signals to your readers that your paper should be taken seriously as a student’s contribution to a given academic or professional field; it is the literary equivalent of wearing a tailored suit to a job interview. Second, it shows that you respect other people’s work enough to give them proper credit for it. Finally, it helps your reader find additional materials if he or she wishes to learn more about your topic.

Furthermore, producing a letter-perfect APA-style paper need not be burdensome. Yes, it requires careful attention to detail. However, you can simplify the process if you keep these broad guidelines in mind:

- Work ahead whenever you can. Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” includes tips for keeping track of your sources early in the research process, which will save time later on.

- Get it right the first time. Apply APA guidelines as you write, so you will not have much to correct during the editing stage. Again, putting in a little extra time early on can save time later.

- Use the resources available to you. In addition to the guidelines provided in this chapter, you may wish to consult the APA website at http://www.apa.org or the Purdue University Online Writing lab at http://owl.english.purdue.edu , which regularly updates its online style guidelines.

General Formatting Guidelines

This chapter provides detailed guidelines for using the citation and formatting conventions developed by the American Psychological Association, or APA. Writers in disciplines as diverse as astrophysics, biology, psychology, and education follow APA style. The major components of a paper written in APA style are listed in the following box.

These are the major components of an APA-style paper:

Body, which includes the following:

- Headings and, if necessary, subheadings to organize the content

- In-text citations of research sources

- References page

All these components must be saved in one document, not as separate documents.

The title page of your paper includes the following information:

- Title of the paper

- Author’s name

- Name of the institution with which the author is affiliated

- Header at the top of the page with the paper title (in capital letters) and the page number (If the title is lengthy, you may use a shortened form of it in the header.)

List the first three elements in the order given in the previous list, centered about one third of the way down from the top of the page. Use the headers and footers tool of your word-processing program to add the header, with the title text at the left and the page number in the upper-right corner. Your title page should look like the following example.

The next page of your paper provides an abstract , or brief summary of your findings. An abstract does not need to be provided in every paper, but an abstract should be used in papers that include a hypothesis. A good abstract is concise—about one hundred fifty to two hundred fifty words—and is written in an objective, impersonal style. Your writing voice will not be as apparent here as in the body of your paper. When writing the abstract, take a just-the-facts approach, and summarize your research question and your findings in a few sentences.

In Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” , you read a paper written by a student named Jorge, who researched the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets. Read Jorge’s abstract. Note how it sums up the major ideas in his paper without going into excessive detail.

Write an abstract summarizing your paper. Briefly introduce the topic, state your findings, and sum up what conclusions you can draw from your research. Use the word count feature of your word-processing program to make sure your abstract does not exceed one hundred fifty words.

Depending on your field of study, you may sometimes write research papers that present extensive primary research, such as your own experiment or survey. In your abstract, summarize your research question and your findings, and briefly indicate how your study relates to prior research in the field.

Margins, Pagination, and Headings

APA style requirements also address specific formatting concerns, such as margins, pagination, and heading styles, within the body of the paper. Review the following APA guidelines.

Use these general guidelines to format the paper:

- Set the top, bottom, and side margins of your paper at 1 inch.

- Use double-spaced text throughout your paper.

- Use a standard font, such as Times New Roman or Arial, in a legible size (10- to 12-point).

- Use continuous pagination throughout the paper, including the title page and the references section. Page numbers appear flush right within your header.

- Section headings and subsection headings within the body of your paper use different types of formatting depending on the level of information you are presenting. Additional details from Jorge’s paper are provided.

Begin formatting the final draft of your paper according to APA guidelines. You may work with an existing document or set up a new document if you choose. Include the following:

- Your title page

- The abstract you created in Note 13.8 “Exercise 1”

- Correct headers and page numbers for your title page and abstract

APA style uses section headings to organize information, making it easy for the reader to follow the writer’s train of thought and to know immediately what major topics are covered. Depending on the length and complexity of the paper, its major sections may also be divided into subsections, sub-subsections, and so on. These smaller sections, in turn, use different heading styles to indicate different levels of information. In essence, you are using headings to create a hierarchy of information.

The following heading styles used in APA formatting are listed in order of greatest to least importance:

- Section headings use centered, boldface type. Headings use title case, with important words in the heading capitalized.

- Subsection headings use left-aligned, boldface type. Headings use title case.

- The third level uses left-aligned, indented, boldface type. Headings use a capital letter only for the first word, and they end in a period.

- The fourth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are boldfaced and italicized.

- The fifth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are italicized and not boldfaced.

Visually, the hierarchy of information is organized as indicated in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” .

Table 13.1 Section Headings

A college research paper may not use all the heading levels shown in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” , but you are likely to encounter them in academic journal articles that use APA style. For a brief paper, you may find that level 1 headings suffice. Longer or more complex papers may need level 2 headings or other lower-level headings to organize information clearly. Use your outline to craft your major section headings and determine whether any subtopics are substantial enough to require additional levels of headings.

Working with the document you developed in Note 13.11 “Exercise 2” , begin setting up the heading structure of the final draft of your research paper according to APA guidelines. Include your title and at least two to three major section headings, and follow the formatting guidelines provided above. If your major sections should be broken into subsections, add those headings as well. Use your outline to help you.

Because Jorge used only level 1 headings, his Exercise 3 would look like the following:

Citation Guidelines

In-text citations.

Throughout the body of your paper, include a citation whenever you quote or paraphrase material from your research sources. As you learned in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , the purpose of citations is twofold: to give credit to others for their ideas and to allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired. Your in-text citations provide basic information about your source; each source you cite will have a longer entry in the references section that provides more detailed information.

In-text citations must provide the name of the author or authors and the year the source was published. (When a given source does not list an individual author, you may provide the source title or the name of the organization that published the material instead.) When directly quoting a source, it is also required that you include the page number where the quote appears in your citation.

This information may be included within the sentence or in a parenthetical reference at the end of the sentence, as in these examples.

Epstein (2010) points out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Here, the writer names the source author when introducing the quote and provides the publication date in parentheses after the author’s name. The page number appears in parentheses after the closing quotation marks and before the period that ends the sentence.

Addiction researchers caution that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (Epstein, 2010, p. 137).

Here, the writer provides a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence that includes the author’s name, the year of publication, and the page number separated by commas. Again, the parenthetical citation is placed after the closing quotation marks and before the period at the end of the sentence.

As noted in the book Junk Food, Junk Science (Epstein, 2010, p. 137), “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive.”

Here, the writer chose to mention the source title in the sentence (an optional piece of information to include) and followed the title with a parenthetical citation. Note that the parenthetical citation is placed before the comma that signals the end of the introductory phrase.

David Epstein’s book Junk Food, Junk Science (2010) pointed out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Another variation is to introduce the author and the source title in your sentence and include the publication date and page number in parentheses within the sentence or at the end of the sentence. As long as you have included the essential information, you can choose the option that works best for that particular sentence and source.

Citing a book with a single author is usually a straightforward task. Of course, your research may require that you cite many other types of sources, such as books or articles with more than one author or sources with no individual author listed. You may also need to cite sources available in both print and online and nonprint sources, such as websites and personal interviews. Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.2 “Citing and Referencing Techniques” and Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provide extensive guidelines for citing a variety of source types.

Writing at Work

APA is just one of several different styles with its own guidelines for documentation, formatting, and language usage. Depending on your field of interest, you may be exposed to additional styles, such as the following:

- MLA style. Determined by the Modern Languages Association and used for papers in literature, languages, and other disciplines in the humanities.

- Chicago style. Outlined in the Chicago Manual of Style and sometimes used for papers in the humanities and the sciences; many professional organizations use this style for publications as well.

- Associated Press (AP) style. Used by professional journalists.

References List

The brief citations included in the body of your paper correspond to the more detailed citations provided at the end of the paper in the references section. In-text citations provide basic information—the author’s name, the publication date, and the page number if necessary—while the references section provides more extensive bibliographical information. Again, this information allows your reader to follow up on the sources you cited and do additional reading about the topic if desired.

The specific format of entries in the list of references varies slightly for different source types, but the entries generally include the following information:

- The name(s) of the author(s) or institution that wrote the source

- The year of publication and, where applicable, the exact date of publication

- The full title of the source

- For books, the city of publication

- For articles or essays, the name of the periodical or book in which the article or essay appears

- For magazine and journal articles, the volume number, issue number, and pages where the article appears

- For sources on the web, the URL where the source is located

The references page is double spaced and lists entries in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. If an entry continues for more than one line, the second line and each subsequent line are indented five spaces. Review the following example. ( Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provides extensive guidelines for formatting reference entries for different types of sources.)

In APA style, book and article titles are formatted in sentence case, not title case. Sentence case means that only the first word is capitalized, along with any proper nouns.

Key Takeaways

- Following proper citation and formatting guidelines helps writers ensure that their work will be taken seriously, give proper credit to other authors for their work, and provide valuable information to readers.

- Working ahead and taking care to cite sources correctly the first time are ways writers can save time during the editing stage of writing a research paper.

- APA papers usually include an abstract that concisely summarizes the paper.

- APA papers use a specific headings structure to provide a clear hierarchy of information.

- In APA papers, in-text citations usually include the name(s) of the author(s) and the year of publication.

- In-text citations correspond to entries in the references section, which provide detailed bibliographical information about a source.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Understanding research and critical appraisal

- Introduction

- Secondary research

What is primary research?

Quantitative research study designs, qualitative research study designs, mixed methods research study designs.

- Critical appraisal of research papers

- Useful terminology

- Further reading and helpful resources

Primary research articles provide a report of individual, original research studies, which constitute the majority of articles published in peer-reviewed journals. All primary research studies are conducted according to a specified methodology, which will be partly determined by the aims and objectives of the research.

The following sections offer brief summaries of some of the common quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods study designs you may encounter.

Randomised Controlled Trial

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) is a study where participants are randomly allocated to two or more groups. One group receives the treatment that is being tested by the study (treatment or experimental group), and the other group(s) receive an alternative, which is often the current standard treatment or a placebo (control or comparison group). The nature of the control used should always be specified.

An RCT is a good study choice for determining the effectiveness of an intervention or treatment, or for comparing the relative effectiveness of different interventions or treatments. If well implemented, the randomisation of participants in RCTs should ensure that the groups differ only in their exposure to treatment, and that differences in outcomes between the groups are probably attributable to the treatment being studied.

In crossover randomised controlled trials, participants receive all of the treatments and controls being tested in a random order. This means that participants receive one treatment, the effect of which is measured, and then "cross over" into the other treatment group, where the effect of the second treatment (or control) is measured.

RCTs are generally considered to be the most rigorous experimental study design, as the randomisation of participants helps to minimise confounding and other sources of bias.

Cohort study

A cohort study identifies a group of people and follows them over a period of time to see who develops the outcome of interest to the study. This type of study is normally used to look at the effect of suspected risk factors that cannot be controlled experimentally – for example, the effect of smoking on lung cancer.

Also sometimes called longitudinal studies, cohort studies can be either prospective, that is, exposure factors are identified at the beginning of a study and the study population is followed into the future, or retrospective, that is, medical records for the study population are used to identify past exposure factors.

Cohort studies are useful in answering questions about disease causation or progression, or studying the effects of harmful exposures.

Cohort studies are generally considered to be the most reliable observational study design. They are not as reliable as RCTs, as the study groups may differ in ways other than the variable being studied.

Other problems with cohort studies are that they require a large sample size, are inefficient for rare outcomes, and can take long periods of time.

Case-Control Study

A case-control study compares a group of people with a disease or condition, against a control population without the disease or condition, in order to investigate the causes of particular outcomes. The study looks back at the two groups over time to see which risk factors for the disease or condition they have been exposed to.

Case-control studies can be useful in identifying which risk factors may predict a disease, or how a disease progresses over time. They can be especially useful for investigating the causes of rare outcomes.

Case-control studies can be done quickly, and do not require large groups of subjects. However, their reliance on retrospective data which may be incomplete or unreliable (owing to subject ability to accurately recall information such as the appearance of a symptom) can be a difficulty.

Cross-Sectional Study

A cross-sectional study collects data from the study population at one point in time, and considers the relationships between characteristics. Also sometimes called surveys or prevalence studies.

Cross-sectional studies are generally used to study the prevalence of a risk factor, disease or outcome in a chosen population.

Because cross-sectional studies do not look at trends or changes over time, they cannot establish cause and effect between exposures and outcomes.

Case Series / Case Reports

A case series is a descriptive study of a group of people, who have either received the same treatment or have the same disease, in order to identify characteristics or outcomes in a particular group of people.

Case series are useful for studying rare diseases or adverse outcomes, for illustrating particular aspects of a condition, identifying treatment approaches, and for generating hypotheses for further study.

A case report provides a study of an individual, rather than a group.

Case series and case reports have no comparative control groups, and are prone to bias and chance association.

Expert opinion

Expert opinion draws upon the clinical experience and recommendations of those with established expertise on a topic.

Grounded theory

Grounded theory studies aim to generate theory in order to explain social processes, interactions or issues. This explanatory theory is grounded in, and generated from, the research participant data collected.

Research data typically takes the form of interviews, observations or documents. Data is analysed as it is collected, and is coded and organised into categories which inform the further collection of data, and the construction of theory. This cycle helps to refine the theory, which evolves as more data is gathered.

Phenomenology

A phenomenological study aims to describe the meaning(s) of the lived experience of a phenomenon. Research participants will have some common experience of the phenomenon under examination, but will differ in their precise individual experience, and in other personal or social characteristics.

Research data is typically in the form of observations, interviews or written records, and its analysis sets out to identify common themes in the participants' experience, while also highlighting variations and unique themes.

Ethnography

Ethnography is the study of a specific culture or cultural group, where the researcher seeks an insider perspective by placing themselves as a participant observer within the group under study.

Data is typically formed of observations, interviews and conversation. Ethnography aims to offer direct insight into the lives and the experiences of the group or the culture under study, examining its beliefs, values, practices and behaviours.

A case study offers a detailed description of the experience of an individual, a family, a community or an organisation, often with the aim of highlighting a particular issue. Research data may include documents, interviews and observations.

Content analysis

Content analysis is used to explore the occurrence, meanings and relationships of words, themes or concepts within a set of textual data. Research data might be drawn from any type of written document(s). Data is coded and categorised, with the aim of revealing and examining the patterns and the intentions of language use within the data set.

Narrative inquiry

A narrative inquiry offers in depth detail of a situation or experience from the perspective of an individual or small groups. Research data usually consists of interviews or recordings, which is presented as a structured, chronological narrative. Narrative inquiry studies often seek to give voice to individuals or populations whose perspective is less well established, or not commonly sought.

Action research

Action research is a form of research, commonly used with groups, where the participants take a more active, collaborative role in producing the research. Studies incorporate the lived experiences of the individuals, groups or communities under study, drawing on data which might include observation, interviews, questionnaires or workshops.

Action research is generally aimed at changing or improving a particular context, or a specific practice, alongside the generation of theory.

Explanatory sequential design

In an explanatory sequential study, emphasis is given to the collection and analysis of quantitative data, which occurs during the first phase of the study. The results of this quantitative phase inform the subsequent collection of qualitative data in the next phase.

Analysis of the resultant qualitative data is then used to 'explain' the quantitative results, usually serving to contextualise these, or to otherwise enhance or enrich the initial findings.

Exploratory sequential design

In an exploratory sequential study, the opposite sequence to that outlined above is used. In this case, qualitative data is emphasised, with this being collected and analysed during the first phase of the study. The results of this qualitative phase inform the subsequent collection of quantitative data in the next phase.

The quantitative data can then be used to define or to generalise the qualitative results, or to test these results on the basis of theory emerging from the initial findings.

Convergent design

In a convergent study, qualitative and quantitative data sets are collected and analysed simultaneously and independently of one another.

Results from analysis of both sets of data are brought together to provide one overall interpretation; this combination of data types can be handled in various ways, but the objective is always to provide a fuller understanding of the phenomena under study. Equal emphasis is given to both qualitative and quantitative data in a convergent study.

- << Previous: Secondary research

- Next: Critical appraisal of research papers >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 4:38 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sgul.ac.uk/researchdesign

What Is a Primary Source?

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms - Definition and Examples

Diane Diederich / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In research and academics, a primary source refers to information collected from sources that witnessed or experienced an event firsthand. These can be historical documents , literary texts, artistic works, experiments, journal entries, surveys, and interviews. A primary source, which is very different from a secondary source , is also called primary data.

The Library of Congress defines primary sources as "the raw materials of history—original documents and objects which were created at the time under study," in contrast to secondary sources , which are "accounts or interpretations of events created by someone without firsthand experience," ("Using Primary Sources").

Secondary sources are often meant to describe or analyze a primary source and do not give firsthand accounts; primary sources tend to provide more accurate depictions of history but are much harder to come by.

Characteristics of Primary Sources

There are a couple of factors that can qualify an artifact as a primary source. The chief characteristics of a primary source, according to Natalie Sproull, are: "(1) [B]eing present during the experience, event or time and (2) consequently being close in time with the data. This does not mean that data from primary sources are always the best data."

Sproull then goes on to remind readers that primary sources are not always more reliable than secondary sources. "Data from human sources are subject to many types of distortion because of such factors as selective recall, selective perceptions, and purposeful or nonpurposeful omission or addition of information. Thus data from primary sources are not necessarily accurate data even though they come from firsthand sources," (Sproull 1988).

Original Sources

Primary sources are often called original sources, but this is not the most accurate description because you're not always going to be dealing with original copies of primary artifacts. For this reason, "primary sources" and "original sources" should be considered separate. Here's what the authors of "Undertaking Historical Research in Literacy," from Handbook of Reading Research , have to say about this:

"The distinction also needs to be made between primary and original sources . It is by no means always necessary, and all too often it is not possible, to deal only with original sources. Printed copies of original sources, provided they have been undertaken with scrupulous care (such as the published letters of the Founding Fathers), are usually an acceptable substitute for their handwritten originals." (E. J. Monaghan and D. K. Hartman, "Undertaking Historical Research in Literacy," in Handbook of Reading Research , ed. by P. D. Pearson et al. Erlbaum, 2000)

When to Use Primary Sources

Primary sources tend to be most useful toward the beginning of your research into a topic and at the end of a claim as evidence, as Wayne Booth et al. explain in the following passage. "[Primary sources] provide the 'raw data' that you use first to test the working hypothesis and then as evidence to support your claim . In history, for example, primary sources include documents from the period or person you are studying, objects, maps, even clothing; in literature or philosophy, your main primary source is usually the text you are studying, and your data are the words on the page. In such fields, you can rarely write a research paper without using primary sources," (Booth et al. 2008).

When to Use Secondary Sources

There is certainly a time and place for secondary sources and many situations in which these point to relevant primary sources. Secondary sources are an excellent place to start. Alison Hoagland and Gray Fitzsimmons write: "By identifying basic facts, such as year of construction, secondary sources can point the researcher to the best primary sources , such as the right tax books. In addition, a careful reading of the bibliography in a secondary source can reveal important sources the researcher might otherwise have missed," (Hoagland and Fitzsimmons 2004).

Finding and Accessing Primary Sources

As you might expect, primary sources can prove difficult to find. To find the best ones, take advantage of resources such as libraries and historical societies. "This one is entirely dependent on the assignment given and your local resources; but when included, always emphasize quality. ... Keep in mind that there are many institutions such as the Library of Congress that make primary source material freely available on the Web," (Kitchens 2012).

Methods of Collecting Primary Data

Sometimes in your research, you'll run into the problem of not being able to track down primary sources at all. When this happens, you'll want to know how to collect your own primary data; Dan O'Hair et all tell you how: "If the information you need is unavailable or hasn't yet been gathered, you'll have to gather it yourself. Four basic methods of collecting primary data are field research, content analysis, survey research, and experiments. Other methods of gathering primary data include historical research, analysis of existing statistics, ... and various forms of direct observation," (O'Hair et al. 2001).

- Booth, Wayne C., et al. The Craft of Research . 3rd ed., University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- Hoagland, Alison, and Gray Fitzsimmons. "History." Recording Historic Structures. 2nd. ed., John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

- Kitchens, Joel D. Librarians, Historians, and New Opportunities for Discourse: A Guide for Clio's Helpers . ABC-CLIO, 2012.

- Monaghan, E. Jennifer, and Douglas K. Hartman. "Undertaking Historical Research in Literacy." Handbook of Reading Research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002.

- O'Hair, Dan, et al. Business Communication: A Framework for Success . South-Western College Pub., 2001.

- Sproull, Natalie L. Handbook of Research Methods: A Guide for Practitioners and Students in the Social Sciences. 2nd ed. Scarecrow Press, 1988.

- "Using Primary Sources." Library of Congress .

- Secondary Sources in Research

- Primary and Secondary Sources in History

- How to Prove Your Family Tree Connections

- Research in Essays and Reports

- Five Steps to Verifying Online Genealogy Sources

- Pros and Cons of Secondary Data Analysis

- Understanding Secondary Data and How to Use It in Research

- Documentation in Reports and Research Papers

- What Is a Research Paper?

- 6 Skills Students Need to Succeed in Social Studies Classes

- How to Use Libraries and Archives for Research

- How to Cite Genealogy Sources

- Definition and Examples of Quotation in English Grammar

- Glossary of Historical Terms

- How to Determine a Reliable Source on the Internet

- Fashion Throughout History

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Primary Research: What It Is, Purpose & Methods + Examples

As we continue exploring the exciting research world, we’ll come across two primary and secondary data approaches. This article will focus on primary research – what it is, how it’s done, and why it’s essential.

We’ll discuss the methods used to gather first-hand data and examples of how it’s applied in various fields. Get ready to discover how this research can be used to solve research problems , answer questions, and drive innovation.

What is Primary Research: Definition

Primary research is a methodology researchers use to collect data directly rather than depending on data collected from previously done research. Technically, they “own” the data. Primary research is solely carried out to address a certain problem, which requires in-depth analysis .

There are two forms of research:

- Primary Research

- Secondary Research

Businesses or organizations can conduct primary research or employ a third party to conduct research. One major advantage of primary research is this type of research is “pinpointed.” Research only focuses on a specific issue or problem and on obtaining related solutions.

For example, a brand is about to launch a new mobile phone model and wants to research the looks and features they will soon introduce.

Organizations can select a qualified sample of respondents closely resembling the population and conduct primary research with them to know their opinions. Based on this research, the brand can now think of probable solutions to make necessary changes in the looks and features of the mobile phone.

Primary Research Methods with Examples

In this technology-driven world, meaningful data is more valuable than gold. Organizations or businesses need highly validated data to make informed decisions. This is the very reason why many companies are proactive in gathering their own data so that the authenticity of data is maintained and they get first-hand data without any alterations.

Here are some of the primary research methods organizations or businesses use to collect data:

1. Interviews (telephonic or face-to-face)

Conducting interviews is a qualitative research method to collect data and has been a popular method for ages. These interviews can be conducted in person (face-to-face) or over the telephone. Interviews are an open-ended method that involves dialogues or interaction between the interviewer (researcher) and the interviewee (respondent).

Conducting a face-to-face interview method is said to generate a better response from respondents as it is a more personal approach. However, the success of face-to-face interviews depends heavily on the researcher’s ability to ask questions and his/her experience related to conducting such interviews in the past. The types of questions that are used in this type of research are mostly open-ended questions . These questions help to gain in-depth insights into the opinions and perceptions of respondents.

Personal interviews usually last up to 30 minutes or even longer, depending on the subject of research. If a researcher is running short of time conducting telephonic interviews can also be helpful to collect data.

2. Online surveys

Once conducted with pen and paper, surveys have come a long way since then. Today, most researchers use online surveys to send to respondents to gather information from them. Online surveys are convenient and can be sent by email or can be filled out online. These can be accessed on handheld devices like smartphones, tablets, iPads, and similar devices.

Once a survey is deployed, a certain amount of stipulated time is given to respondents to answer survey questions and send them back to the researcher. In order to get maximum information from respondents, surveys should have a good mix of open-ended questions and close-ended questions . The survey should not be lengthy. Respondents lose interest and tend to leave it half-done.

It is a good practice to reward respondents for successfully filling out surveys for their time and efforts and valuable information. Most organizations or businesses usually give away gift cards from reputed brands that respondents can redeem later.

3. Focus groups

This popular research technique is used to collect data from a small group of people, usually restricted to 6-10. Focus group brings together people who are experts in the subject matter for which research is being conducted.

Focus group has a moderator who stimulates discussions among the members to get greater insights. Organizations and businesses can make use of this method, especially to identify niche markets to learn about a specific group of consumers.

4. Observations

In this primary research method, there is no direct interaction between the researcher and the person/consumer being observed. The researcher observes the reactions of a subject and makes notes.

Trained observers or cameras are used to record reactions. Observations are noted in a predetermined situation. For example, a bakery brand wants to know how people react to its new biscuits, observes notes on consumers’ first reactions, and evaluates collective data to draw inferences .

Primary Research vs Secondary Research – The Differences

Primary and secondary research are two distinct approaches to gathering information, each with its own characteristics and advantages.

While primary research involves conducting surveys to gather firsthand data from potential customers, secondary market research is utilized to analyze existing industry reports and competitor data, providing valuable context and benchmarks for the survey findings.

Find out more details about the differences:

1. Definition

- Primary Research: Involves the direct collection of original data specifically for the research project at hand. Examples include surveys, interviews, observations, and experiments.

- Secondary Research: Involves analyzing and interpreting existing data, literature, or information. This can include sources like books, articles, databases, and reports.

2. Data Source

- Primary Research: Data is collected directly from individuals, experiments, or observations.

- Secondary Research: Data is gathered from already existing sources.

3. Time and Cost

- Primary Research: Often time-consuming and can be costly due to the need for designing and implementing research instruments and collecting new data.

- Secondary Research: Generally more time and cost-effective, as it relies on readily available data.

4. Customization

- Primary Research: Provides tailored and specific information, allowing researchers to address unique research questions.

- Secondary Research: Offers information that is pre-existing and may not be as customized to the specific needs of the researcher.

- Primary Research: Researchers have control over the research process, including study design, data collection methods , and participant selection.

- Secondary Research: Limited control, as researchers rely on data collected by others.

6. Originality

- Primary Research: Generates original data that hasn’t been analyzed before.

- Secondary Research: Involves the analysis of data that has been previously collected and analyzed.

7. Relevance and Timeliness

- Primary Research: Often provides more up-to-date and relevant data or information.

- Secondary Research: This may involve data that is outdated, but it can still be valuable for historical context or broad trends.

Advantages of Primary Research

Primary research has several advantages over other research methods, making it an indispensable tool for anyone seeking to understand their target market, improve their products or services, and stay ahead of the competition. So let’s dive in and explore the many benefits of primary research.

- One of the most important advantages is data collected is first-hand and accurate. In other words, there is no dilution of data. Also, this research method can be customized to suit organizations’ or businesses’ personal requirements and needs .

- I t focuses mainly on the problem at hand, which means entire attention is directed to finding probable solutions to a pinpointed subject matter. Primary research allows researchers to go in-depth about a matter and study all foreseeable options.

- Data collected can be controlled. I T gives a means to control how data is collected and used. It’s up to the discretion of businesses or organizations who are collecting data how to best make use of data to get meaningful research insights.

- I t is a time-tested method, therefore, one can rely on the results that are obtained from conducting this type of research.

Disadvantages of Primary Research

While primary research is a powerful tool for gathering unique and firsthand data, it also has its limitations. As we explore the drawbacks, we’ll gain a deeper understanding of when primary research may not be the best option and how to work around its challenges.

- One of the major disadvantages of primary research is it can be quite expensive to conduct. One may be required to spend a huge sum of money depending on the setup or primary research method used. Not all businesses or organizations may be able to spend a considerable amount of money.

- This type of research can be time-consuming. Conducting interviews and sending and receiving online surveys can be quite an exhaustive process and require investing time and patience for the process to work. Moreover, evaluating results and applying the findings to improve a product or service will need additional time.

- Sometimes, just using one primary research method may not be enough. In such cases, the use of more than one method is required, and this might increase both the time required to conduct research and the cost associated with it.

Every research is conducted with a purpose. Primary research is conducted by organizations or businesses to stay informed of the ever-changing market conditions and consumer perception. Excellent customer satisfaction (CSAT) has become a key goal and objective of many organizations.

A customer-centric organization knows the importance of providing exceptional products and services to its customers to increase customer loyalty and decrease customer churn. Organizations collect data and analyze it by conducting primary research to draw highly evaluated results and conclusions. Using this information, organizations are able to make informed decisions based on real data-oriented insights.

QuestionPro is a comprehensive survey platform that can be used to conduct primary research. Users can create custom surveys and distribute them to their target audience , whether it be through email, social media, or a website.

QuestionPro also offers advanced features such as skip logic, branching, and data analysis tools, making collecting and analyzing data easier. With QuestionPro, you can gather valuable insights and make informed decisions based on the results of your primary research. Start today for free!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

NPS Survey Platform: Types, Tips, 11 Best Platforms & Tools

Apr 26, 2024

User Journey vs User Flow: Differences and Similarities

Best 7 Gap Analysis Tools to Empower Your Business

Apr 25, 2024

12 Best Employee Survey Tools for Organizational Excellence

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Research Paper Structure

Whether you are writing a B.S. Degree Research Paper or completing a research report for a Psychology course, it is highly likely that you will need to organize your research paper in accordance with American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines. Here we discuss the structure of research papers according to APA style.

Major Sections of a Research Paper in APA Style

A complete research paper in APA style that is reporting on experimental research will typically contain a Title page, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and References sections. 1 Many will also contain Figures and Tables and some will have an Appendix or Appendices. These sections are detailed as follows (for a more in-depth guide, please refer to " How to Write a Research Paper in APA Style ”, a comprehensive guide developed by Prof. Emma Geller). 2

What is this paper called and who wrote it? – the first page of the paper; this includes the name of the paper, a “running head”, authors, and institutional affiliation of the authors. The institutional affiliation is usually listed in an Author Note that is placed towards the bottom of the title page. In some cases, the Author Note also contains an acknowledgment of any funding support and of any individuals that assisted with the research project.

One-paragraph summary of the entire study – typically no more than 250 words in length (and in many cases it is well shorter than that), the Abstract provides an overview of the study.

Introduction

What is the topic and why is it worth studying? – the first major section of text in the paper, the Introduction commonly describes the topic under investigation, summarizes or discusses relevant prior research (for related details, please see the Writing Literature Reviews section of this website), identifies unresolved issues that the current research will address, and provides an overview of the research that is to be described in greater detail in the sections to follow.

What did you do? – a section which details how the research was performed. It typically features a description of the participants/subjects that were involved, the study design, the materials that were used, and the study procedure. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Methods section. A rule of thumb is that the Methods section should be sufficiently detailed for another researcher to duplicate your research.

What did you find? – a section which describes the data that was collected and the results of any statistical tests that were performed. It may also be prefaced by a description of the analysis procedure that was used. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Results section.

What is the significance of your results? – the final major section of text in the paper. The Discussion commonly features a summary of the results that were obtained in the study, describes how those results address the topic under investigation and/or the issues that the research was designed to address, and may expand upon the implications of those findings. Limitations and directions for future research are also commonly addressed.

List of articles and any books cited – an alphabetized list of the sources that are cited in the paper (by last name of the first author of each source). Each reference should follow specific APA guidelines regarding author names, dates, article titles, journal titles, journal volume numbers, page numbers, book publishers, publisher locations, websites, and so on (for more information, please see the Citing References in APA Style page of this website).

Tables and Figures

Graphs and data (optional in some cases) – depending on the type of research being performed, there may be Tables and/or Figures (however, in some cases, there may be neither). In APA style, each Table and each Figure is placed on a separate page and all Tables and Figures are included after the References. Tables are included first, followed by Figures. However, for some journals and undergraduate research papers (such as the B.S. Research Paper or Honors Thesis), Tables and Figures may be embedded in the text (depending on the instructor’s or editor’s policies; for more details, see "Deviations from APA Style" below).

Supplementary information (optional) – in some cases, additional information that is not critical to understanding the research paper, such as a list of experiment stimuli, details of a secondary analysis, or programming code, is provided. This is often placed in an Appendix.

Variations of Research Papers in APA Style

Although the major sections described above are common to most research papers written in APA style, there are variations on that pattern. These variations include:

- Literature reviews – when a paper is reviewing prior published research and not presenting new empirical research itself (such as in a review article, and particularly a qualitative review), then the authors may forgo any Methods and Results sections. Instead, there is a different structure such as an Introduction section followed by sections for each of the different aspects of the body of research being reviewed, and then perhaps a Discussion section.

- Multi-experiment papers – when there are multiple experiments, it is common to follow the Introduction with an Experiment 1 section, itself containing Methods, Results, and Discussion subsections. Then there is an Experiment 2 section with a similar structure, an Experiment 3 section with a similar structure, and so on until all experiments are covered. Towards the end of the paper there is a General Discussion section followed by References. Additionally, in multi-experiment papers, it is common for the Results and Discussion subsections for individual experiments to be combined into single “Results and Discussion” sections.

Departures from APA Style

In some cases, official APA style might not be followed (however, be sure to check with your editor, instructor, or other sources before deviating from standards of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association). Such deviations may include:

- Placement of Tables and Figures – in some cases, to make reading through the paper easier, Tables and/or Figures are embedded in the text (for example, having a bar graph placed in the relevant Results section). The embedding of Tables and/or Figures in the text is one of the most common deviations from APA style (and is commonly allowed in B.S. Degree Research Papers and Honors Theses; however you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first).

- Incomplete research – sometimes a B.S. Degree Research Paper in this department is written about research that is currently being planned or is in progress. In those circumstances, sometimes only an Introduction and Methods section, followed by References, is included (that is, in cases where the research itself has not formally begun). In other cases, preliminary results are presented and noted as such in the Results section (such as in cases where the study is underway but not complete), and the Discussion section includes caveats about the in-progress nature of the research. Again, you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first.

- Class assignments – in some classes in this department, an assignment must be written in APA style but is not exactly a traditional research paper (for instance, a student asked to write about an article that they read, and to write that report in APA style). In that case, the structure of the paper might approximate the typical sections of a research paper in APA style, but not entirely. You should check with your instructor for further guidelines.

Workshops and Downloadable Resources

- For in-person discussion of the process of writing research papers, please consider attending this department’s “Writing Research Papers” workshop (for dates and times, please check the undergraduate workshops calendar).

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – empirical research) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

APA Journal Article Reporting Guidelines

- Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., & Rao, S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 3.

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 26.

External Resources

- Formatting APA Style Papers in Microsoft Word

- How to Write an APA Style Research Paper from Hamilton University

- WikiHow Guide to Writing APA Research Papers

- Sample APA Formatted Paper with Comments

- Sample APA Formatted Paper

- Tips for Writing a Paper in APA Style

1 VandenBos, G. R. (Ed). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.) (pp. 41-60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

2 geller, e. (2018). how to write an apa-style research report . [instructional materials]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

Everything you need to know about primary research

Last updated

28 February 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

They might search existing research to find the data they need—a technique known as secondary research .

Alternatively, they might prefer to seek out the data they need independently. This is known as primary research.

Analyze your primary research

Bring your primary research together inside Dovetail and uncover actionable insights

- What is primary research?

During primary research, the researcher collects the information and data for a specific sample directly.

Types of primary research

Primary research can take several forms, depending on the type of information studied. Here are the four main types of primary research:

Observations

Focus groups

When conducting primary research, you can collect qualitative or quantitative data (or both).

Qualitative primary data collection provides a vast array of feedback or information about products and services. However, it may need to be interpreted before it is used to make important business decisions.

Quantitative primary data collection , on the other hand, involves looking at the numbers related to a specific product or service.

- What types of projects can benefit from primary research?

Data obtained from primary research may be more accurate than if it were obtained from previous data samples.

Primary research may be used for

Salary guides

Industry benchmarks

Government reports

Any information based on the current state of the target, including statistics related to current information

Scientific studies

Current market research

Crafting user-friendly products

Primary research can also be used to capture any type of sentiment that cannot be represented statistically, verbally, or through transcription. This may include tone of voice, for example. The researcher might want to find out if the subject sounds hesitant, uncertain, or unhappy.

- Methods for conducting primary research

Your methods for conducting primary research may vary based on the information you’re looking for and how you prefer to interact with your target market.

Surveys are a method to obtain direct information and feedback from the target audience. Depending on the target market’s specific needs, they can be conducted over the phone, online, or face-to-face.

Observation

In some cases, primary research will involve watching the behaviors of consumers or members of the target audience.

Communication with members of the target audience who can share direct information and feedback about products and services.

Test marketing

Explore customer response to a product or marketing campaign before a wider release.

Competitor visits

Competitor visits allow you to check out what competitors have to offer to get a better feel for how they interact with their target markets. This approach can help you better understand what the market might be looking for.

This involves bringing a group of people together to discuss a specific product or need within the industry. This approach could help provide essential insights into the needs of that market.

Usability testing

Usability testing allows you to evaluate a product’s usability when you launch a live prototype. You might recruit representative users to perform tasks while you observe, ask questions, and take notes on how they use your product.

- When to conduct primary research

Primary research is needed when you want first-hand information about your product, service, or target market. There are several circumstances where primary research may be the best strategy for getting the information you need.

You might use it to:

Understand pricing information, including what price points customers are likely to purchase at.

Get insight into your sales process. For example, you might look at screenshots of a sales demo, listen to audio recordings of the sales process, or evaluate key details and descriptions.

Learn about problems your consumers might be having and how your business can solve them.

Gauge how a company feels about its competitors. For example, you might want to ask an e-tailer if they plan to offer free shipping to compete with Amazon, Walmart, and other major retailers.

- How to get started with primary research

Step one: Define the problem you’re trying to answer. Clearly identify what you want to know and why it’s important. Does the customer want you to perform the “usual?” This is often the case if they are new, inexperienced, or simply too busy and want to have the task taken care of.

Step two: Determine the best method for getting those answers. Do you need quantitative data , which can be measured in multiple-choice surveys? Or do you need more detailed qualitative data , which may require focus groups or interviews?

Step three: Select your target. Where will you conduct your primary research? You may already have a focus group available; for example, a social media group where people already gather to discuss your brand.

Step four: Compile your questions or define your method. Clearly set out what information you need and how you plan to gather it.

Step five: Research!

- Advantages of primary research

Primary research offers a number of potential advantages. Most importantly, it offers you information that you can’t get elsewhere.

It provides you with direct information from consumers who are already members of your target market or using your products.

You are able to get feedback directly from your target audience, which can allow you to immediately improve products or services and provide better support to your target market.

Primary data is current. Secondary sources may contain outdated data.

Primary data is reliable. You will know what methods you used and how the data relates to your research because you collected it yourself.

- Disadvantages of primary research

You might decide primary research isn’t the best option for your research project when you consider the disadvantages.

Primary research can be time-consuming. You will have to put in the time to collect data yourself, meaning the research may take longer to complete.

Primary research may be more expensive to conduct if it involves face-to-face interactions with your target audience, subscriptions for insight platforms, or participant remuneration.

The people you engage with for your research may feel disrupted by information-gathering methods, so you may not be able to use the same focus group every time you conduct that research.

It can be difficult to gather accurate information from a small group of people, especially if you deliberately select a focus group made up of existing customers.

You may have a hard time accessing people who are not already members of your customer base.

Biased surveys can be a challenge. Researchers may, for example, inadvertently structure questions to encourage participants to respond in a particular way. Questions may also be too confusing or complex for participants to answer accurately.

Despite the researcher’s best efforts, participants don’t always take studies seriously. They may provide inaccurate or irrelevant answers to survey questions, significantly impacting any conclusions you reach. Therefore, researchers must take extra caution when examining results.

Conducting primary research can help you get a closer look at what is really going on with your target market and how they are using your product. That research can then inform your efforts to improve your services and products.

What is primary research, and why is it important?

Primary research is a research method that allows researchers to directly collect information for their use. It can provide more accurate insights into the target audience and market information companies really need.

What are primary research sources?

Primary research sources may include surveys, interviews, visits to competitors, or focus groups.

What is the best method of primary research?

The best method of primary research depends on the type of information you are gathering. If you need qualitative information, you may want to hold focus groups or interviews. On the other hand, if you need quantitative data, you may benefit from conducting surveys with your target audience.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications