Research Methods In Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Research methods in psychology are systematic procedures used to observe, describe, predict, and explain behavior and mental processes. They include experiments, surveys, case studies, and naturalistic observations, ensuring data collection is objective and reliable to understand and explain psychological phenomena.

Hypotheses are statements about the prediction of the results, that can be verified or disproved by some investigation.

There are four types of hypotheses :

- Null Hypotheses (H0 ) – these predict that no difference will be found in the results between the conditions. Typically these are written ‘There will be no difference…’

- Alternative Hypotheses (Ha or H1) – these predict that there will be a significant difference in the results between the two conditions. This is also known as the experimental hypothesis.

- One-tailed (directional) hypotheses – these state the specific direction the researcher expects the results to move in, e.g. higher, lower, more, less. In a correlation study, the predicted direction of the correlation can be either positive or negative.

- Two-tailed (non-directional) hypotheses – these state that a difference will be found between the conditions of the independent variable but does not state the direction of a difference or relationship. Typically these are always written ‘There will be a difference ….’

All research has an alternative hypothesis (either a one-tailed or two-tailed) and a corresponding null hypothesis.

Once the research is conducted and results are found, psychologists must accept one hypothesis and reject the other.

So, if a difference is found, the Psychologist would accept the alternative hypothesis and reject the null. The opposite applies if no difference is found.

Sampling techniques

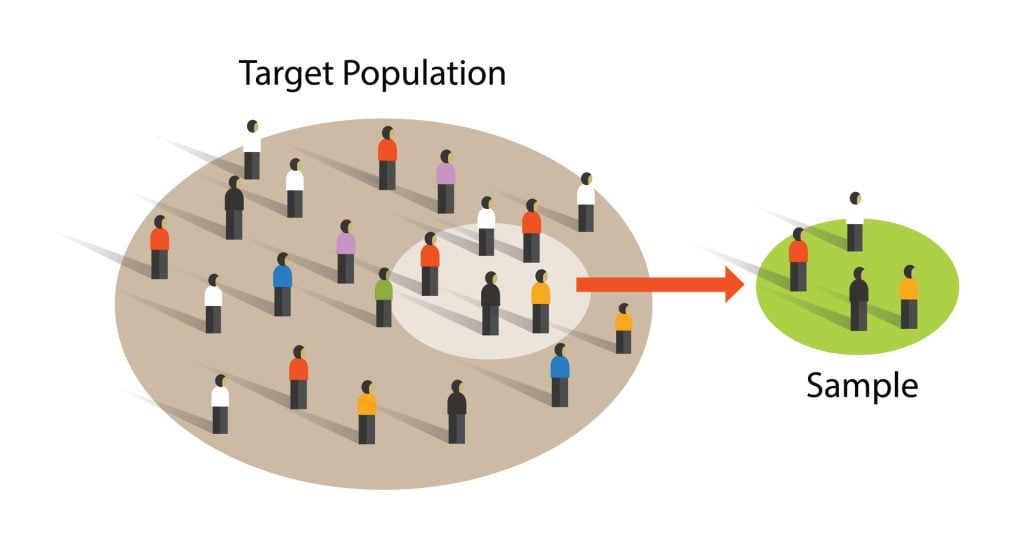

Sampling is the process of selecting a representative group from the population under study.

A sample is the participants you select from a target population (the group you are interested in) to make generalizations about.

Representative means the extent to which a sample mirrors a researcher’s target population and reflects its characteristics.

Generalisability means the extent to which their findings can be applied to the larger population of which their sample was a part.

- Volunteer sample : where participants pick themselves through newspaper adverts, noticeboards or online.

- Opportunity sampling : also known as convenience sampling , uses people who are available at the time the study is carried out and willing to take part. It is based on convenience.

- Random sampling : when every person in the target population has an equal chance of being selected. An example of random sampling would be picking names out of a hat.

- Systematic sampling : when a system is used to select participants. Picking every Nth person from all possible participants. N = the number of people in the research population / the number of people needed for the sample.

- Stratified sampling : when you identify the subgroups and select participants in proportion to their occurrences.

- Snowball sampling : when researchers find a few participants, and then ask them to find participants themselves and so on.

- Quota sampling : when researchers will be told to ensure the sample fits certain quotas, for example they might be told to find 90 participants, with 30 of them being unemployed.

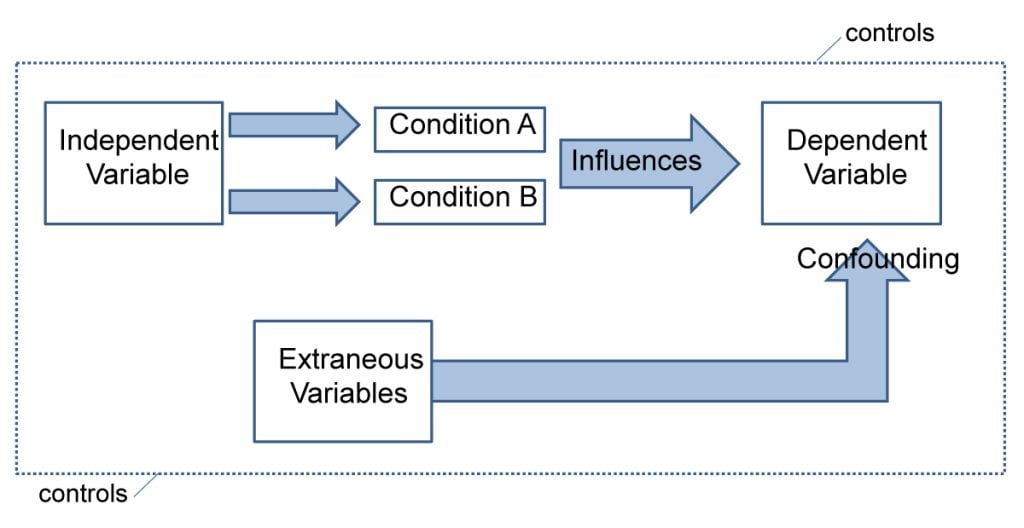

Experiments always have an independent and dependent variable .

- The independent variable is the one the experimenter manipulates (the thing that changes between the conditions the participants are placed into). It is assumed to have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

- The dependent variable is the thing being measured, or the results of the experiment.

Operationalization of variables means making them measurable/quantifiable. We must use operationalization to ensure that variables are in a form that can be easily tested.

For instance, we can’t really measure ‘happiness’, but we can measure how many times a person smiles within a two-hour period.

By operationalizing variables, we make it easy for someone else to replicate our research. Remember, this is important because we can check if our findings are reliable.

Extraneous variables are all variables which are not independent variable but could affect the results of the experiment.

It can be a natural characteristic of the participant, such as intelligence levels, gender, or age for example, or it could be a situational feature of the environment such as lighting or noise.

Demand characteristics are a type of extraneous variable that occurs if the participants work out the aims of the research study, they may begin to behave in a certain way.

For example, in Milgram’s research , critics argued that participants worked out that the shocks were not real and they administered them as they thought this was what was required of them.

Extraneous variables must be controlled so that they do not affect (confound) the results.

Randomly allocating participants to their conditions or using a matched pairs experimental design can help to reduce participant variables.

Situational variables are controlled by using standardized procedures, ensuring every participant in a given condition is treated in the same way

Experimental Design

Experimental design refers to how participants are allocated to each condition of the independent variable, such as a control or experimental group.

- Independent design ( between-groups design ): each participant is selected for only one group. With the independent design, the most common way of deciding which participants go into which group is by means of randomization.

- Matched participants design : each participant is selected for only one group, but the participants in the two groups are matched for some relevant factor or factors (e.g. ability; sex; age).

- Repeated measures design ( within groups) : each participant appears in both groups, so that there are exactly the same participants in each group.

- The main problem with the repeated measures design is that there may well be order effects. Their experiences during the experiment may change the participants in various ways.

- They may perform better when they appear in the second group because they have gained useful information about the experiment or about the task. On the other hand, they may perform less well on the second occasion because of tiredness or boredom.

- Counterbalancing is the best way of preventing order effects from disrupting the findings of an experiment, and involves ensuring that each condition is equally likely to be used first and second by the participants.

If we wish to compare two groups with respect to a given independent variable, it is essential to make sure that the two groups do not differ in any other important way.

Experimental Methods

All experimental methods involve an iv (independent variable) and dv (dependent variable)..

- Field experiments are conducted in the everyday (natural) environment of the participants. The experimenter still manipulates the IV, but in a real-life setting. It may be possible to control extraneous variables, though such control is more difficult than in a lab experiment.

- Natural experiments are when a naturally occurring IV is investigated that isn’t deliberately manipulated, it exists anyway. Participants are not randomly allocated, and the natural event may only occur rarely.

Case studies are in-depth investigations of a person, group, event, or community. It uses information from a range of sources, such as from the person concerned and also from their family and friends.

Many techniques may be used such as interviews, psychological tests, observations and experiments. Case studies are generally longitudinal: in other words, they follow the individual or group over an extended period of time.

Case studies are widely used in psychology and among the best-known ones carried out were by Sigmund Freud . He conducted very detailed investigations into the private lives of his patients in an attempt to both understand and help them overcome their illnesses.

Case studies provide rich qualitative data and have high levels of ecological validity. However, it is difficult to generalize from individual cases as each one has unique characteristics.

Correlational Studies

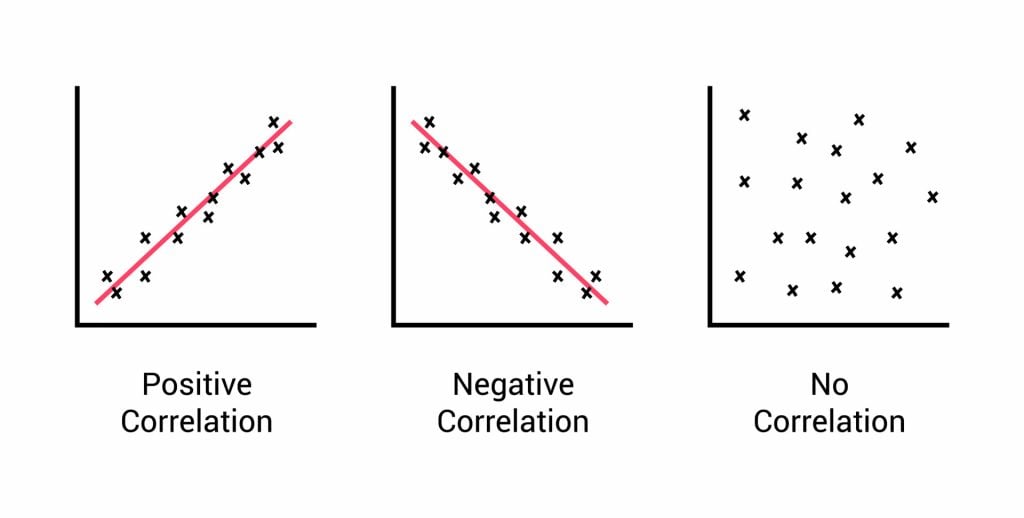

Correlation means association; it is a measure of the extent to which two variables are related. One of the variables can be regarded as the predictor variable with the other one as the outcome variable.

Correlational studies typically involve obtaining two different measures from a group of participants, and then assessing the degree of association between the measures.

The predictor variable can be seen as occurring before the outcome variable in some sense. It is called the predictor variable, because it forms the basis for predicting the value of the outcome variable.

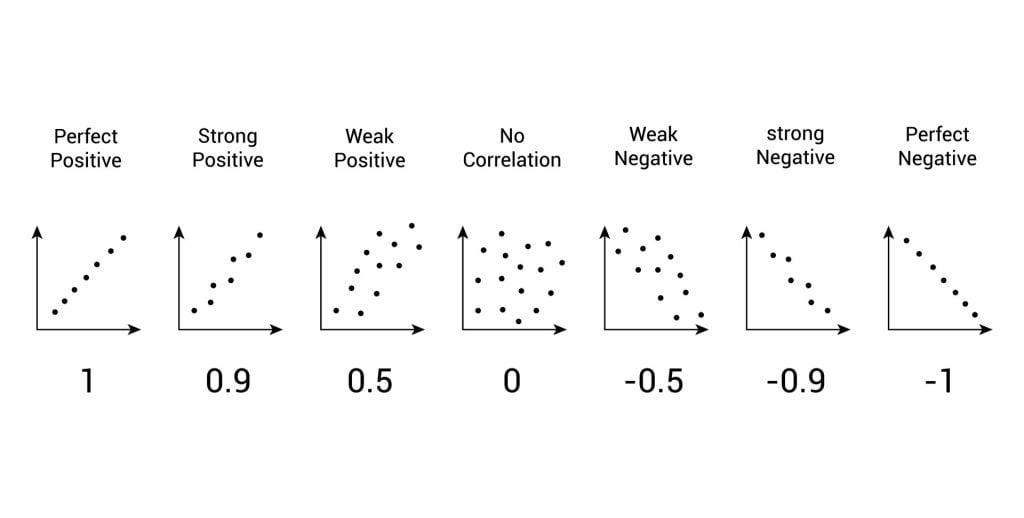

Relationships between variables can be displayed on a graph or as a numerical score called a correlation coefficient.

- If an increase in one variable tends to be associated with an increase in the other, then this is known as a positive correlation .

- If an increase in one variable tends to be associated with a decrease in the other, then this is known as a negative correlation .

- A zero correlation occurs when there is no relationship between variables.

After looking at the scattergraph, if we want to be sure that a significant relationship does exist between the two variables, a statistical test of correlation can be conducted, such as Spearman’s rho.

The test will give us a score, called a correlation coefficient . This is a value between 0 and 1, and the closer to 1 the score is, the stronger the relationship between the variables. This value can be both positive e.g. 0.63, or negative -0.63.

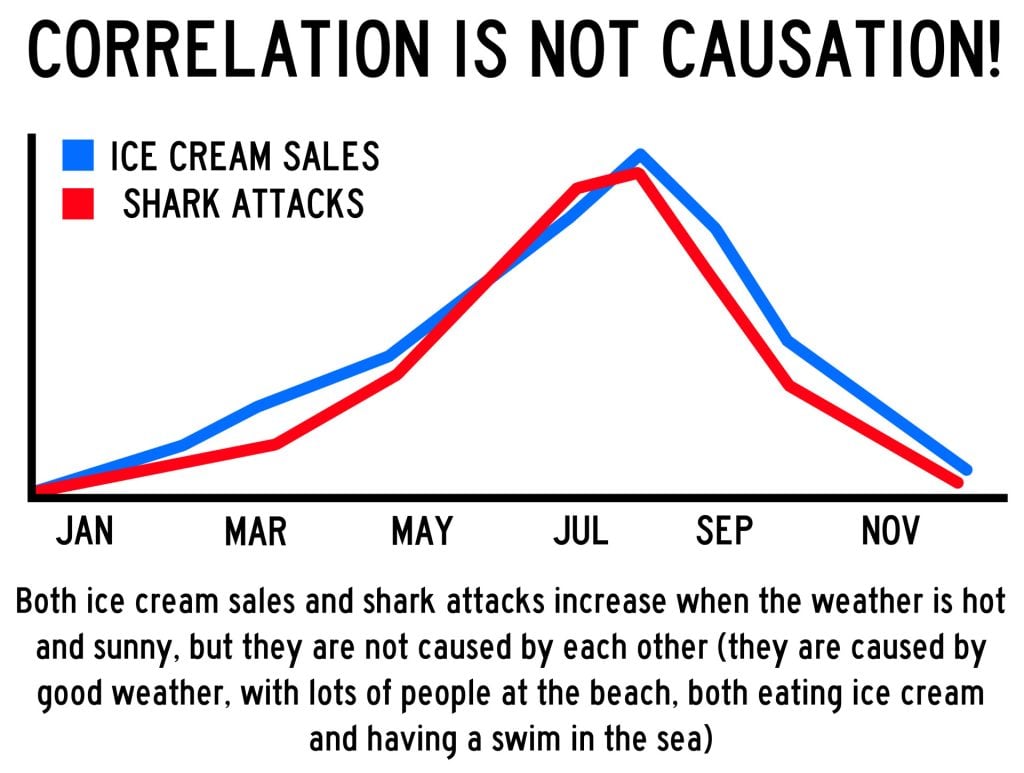

A correlation between variables, however, does not automatically mean that the change in one variable is the cause of the change in the values of the other variable. A correlation only shows if there is a relationship between variables.

Correlation does not always prove causation, as a third variable may be involved.

Interview Methods

Interviews are commonly divided into two types: structured and unstructured.

A fixed, predetermined set of questions is put to every participant in the same order and in the same way.

Responses are recorded on a questionnaire, and the researcher presets the order and wording of questions, and sometimes the range of alternative answers.

The interviewer stays within their role and maintains social distance from the interviewee.

There are no set questions, and the participant can raise whatever topics he/she feels are relevant and ask them in their own way. Questions are posed about participants’ answers to the subject

Unstructured interviews are most useful in qualitative research to analyze attitudes and values.

Though they rarely provide a valid basis for generalization, their main advantage is that they enable the researcher to probe social actors’ subjective point of view.

Questionnaire Method

Questionnaires can be thought of as a kind of written interview. They can be carried out face to face, by telephone, or post.

The choice of questions is important because of the need to avoid bias or ambiguity in the questions, ‘leading’ the respondent or causing offense.

- Open questions are designed to encourage a full, meaningful answer using the subject’s own knowledge and feelings. They provide insights into feelings, opinions, and understanding. Example: “How do you feel about that situation?”

- Closed questions can be answered with a simple “yes” or “no” or specific information, limiting the depth of response. They are useful for gathering specific facts or confirming details. Example: “Do you feel anxious in crowds?”

Its other practical advantages are that it is cheaper than face-to-face interviews and can be used to contact many respondents scattered over a wide area relatively quickly.

Observations

There are different types of observation methods :

- Covert observation is where the researcher doesn’t tell the participants they are being observed until after the study is complete. There could be ethical problems or deception and consent with this particular observation method.

- Overt observation is where a researcher tells the participants they are being observed and what they are being observed for.

- Controlled : behavior is observed under controlled laboratory conditions (e.g., Bandura’s Bobo doll study).

- Natural : Here, spontaneous behavior is recorded in a natural setting.

- Participant : Here, the observer has direct contact with the group of people they are observing. The researcher becomes a member of the group they are researching.

- Non-participant (aka “fly on the wall): The researcher does not have direct contact with the people being observed. The observation of participants’ behavior is from a distance

Pilot Study

A pilot study is a small scale preliminary study conducted in order to evaluate the feasibility of the key s teps in a future, full-scale project.

A pilot study is an initial run-through of the procedures to be used in an investigation; it involves selecting a few people and trying out the study on them. It is possible to save time, and in some cases, money, by identifying any flaws in the procedures designed by the researcher.

A pilot study can help the researcher spot any ambiguities (i.e. unusual things) or confusion in the information given to participants or problems with the task devised.

Sometimes the task is too hard, and the researcher may get a floor effect, because none of the participants can score at all or can complete the task – all performances are low.

The opposite effect is a ceiling effect, when the task is so easy that all achieve virtually full marks or top performances and are “hitting the ceiling”.

Research Design

In cross-sectional research , a researcher compares multiple segments of the population at the same time

Sometimes, we want to see how people change over time, as in studies of human development and lifespan. Longitudinal research is a research design in which data-gathering is administered repeatedly over an extended period of time.

In cohort studies , the participants must share a common factor or characteristic such as age, demographic, or occupation. A cohort study is a type of longitudinal study in which researchers monitor and observe a chosen population over an extended period.

Triangulation means using more than one research method to improve the study’s validity.

Reliability

Reliability is a measure of consistency, if a particular measurement is repeated and the same result is obtained then it is described as being reliable.

- Test-retest reliability : assessing the same person on two different occasions which shows the extent to which the test produces the same answers.

- Inter-observer reliability : the extent to which there is an agreement between two or more observers.

Meta-Analysis

A meta-analysis is a systematic review that involves identifying an aim and then searching for research studies that have addressed similar aims/hypotheses.

This is done by looking through various databases, and then decisions are made about what studies are to be included/excluded.

Strengths: Increases the conclusions’ validity as they’re based on a wider range.

Weaknesses: Research designs in studies can vary, so they are not truly comparable.

Peer Review

A researcher submits an article to a journal. The choice of the journal may be determined by the journal’s audience or prestige.

The journal selects two or more appropriate experts (psychologists working in a similar field) to peer review the article without payment. The peer reviewers assess: the methods and designs used, originality of the findings, the validity of the original research findings and its content, structure and language.

Feedback from the reviewer determines whether the article is accepted. The article may be: Accepted as it is, accepted with revisions, sent back to the author to revise and re-submit or rejected without the possibility of submission.

The editor makes the final decision whether to accept or reject the research report based on the reviewers comments/ recommendations.

Peer review is important because it prevent faulty data from entering the public domain, it provides a way of checking the validity of findings and the quality of the methodology and is used to assess the research rating of university departments.

Peer reviews may be an ideal, whereas in practice there are lots of problems. For example, it slows publication down and may prevent unusual, new work being published. Some reviewers might use it as an opportunity to prevent competing researchers from publishing work.

Some people doubt whether peer review can really prevent the publication of fraudulent research.

The advent of the internet means that a lot of research and academic comment is being published without official peer reviews than before, though systems are evolving on the internet where everyone really has a chance to offer their opinions and police the quality of research.

Types of Data

- Quantitative data is numerical data e.g. reaction time or number of mistakes. It represents how much or how long, how many there are of something. A tally of behavioral categories and closed questions in a questionnaire collect quantitative data.

- Qualitative data is virtually any type of information that can be observed and recorded that is not numerical in nature and can be in the form of written or verbal communication. Open questions in questionnaires and accounts from observational studies collect qualitative data.

- Primary data is first-hand data collected for the purpose of the investigation.

- Secondary data is information that has been collected by someone other than the person who is conducting the research e.g. taken from journals, books or articles.

Validity means how well a piece of research actually measures what it sets out to, or how well it reflects the reality it claims to represent.

Validity is whether the observed effect is genuine and represents what is actually out there in the world.

- Concurrent validity is the extent to which a psychological measure relates to an existing similar measure and obtains close results. For example, a new intelligence test compared to an established test.

- Face validity : does the test measure what it’s supposed to measure ‘on the face of it’. This is done by ‘eyeballing’ the measuring or by passing it to an expert to check.

- Ecological validit y is the extent to which findings from a research study can be generalized to other settings / real life.

- Temporal validity is the extent to which findings from a research study can be generalized to other historical times.

Features of Science

- Paradigm – A set of shared assumptions and agreed methods within a scientific discipline.

- Paradigm shift – The result of the scientific revolution: a significant change in the dominant unifying theory within a scientific discipline.

- Objectivity – When all sources of personal bias are minimised so not to distort or influence the research process.

- Empirical method – Scientific approaches that are based on the gathering of evidence through direct observation and experience.

- Replicability – The extent to which scientific procedures and findings can be repeated by other researchers.

- Falsifiability – The principle that a theory cannot be considered scientific unless it admits the possibility of being proved untrue.

Statistical Testing

A significant result is one where there is a low probability that chance factors were responsible for any observed difference, correlation, or association in the variables tested.

If our test is significant, we can reject our null hypothesis and accept our alternative hypothesis.

If our test is not significant, we can accept our null hypothesis and reject our alternative hypothesis. A null hypothesis is a statement of no effect.

In Psychology, we use p < 0.05 (as it strikes a balance between making a type I and II error) but p < 0.01 is used in tests that could cause harm like introducing a new drug.

A type I error is when the null hypothesis is rejected when it should have been accepted (happens when a lenient significance level is used, an error of optimism).

A type II error is when the null hypothesis is accepted when it should have been rejected (happens when a stringent significance level is used, an error of pessimism).

Ethical Issues

- Informed consent is when participants are able to make an informed judgment about whether to take part. It causes them to guess the aims of the study and change their behavior.

- To deal with it, we can gain presumptive consent or ask them to formally indicate their agreement to participate but it may invalidate the purpose of the study and it is not guaranteed that the participants would understand.

- Deception should only be used when it is approved by an ethics committee, as it involves deliberately misleading or withholding information. Participants should be fully debriefed after the study but debriefing can’t turn the clock back.

- All participants should be informed at the beginning that they have the right to withdraw if they ever feel distressed or uncomfortable.

- It causes bias as the ones that stayed are obedient and some may not withdraw as they may have been given incentives or feel like they’re spoiling the study. Researchers can offer the right to withdraw data after participation.

- Participants should all have protection from harm . The researcher should avoid risks greater than those experienced in everyday life and they should stop the study if any harm is suspected. However, the harm may not be apparent at the time of the study.

- Confidentiality concerns the communication of personal information. The researchers should not record any names but use numbers or false names though it may not be possible as it is sometimes possible to work out who the researchers were.

- Find Books with Library SmartSearch

- Find Articles and eBooks with EBSCOhost

- All Library Resources

- Left Your Textbook At Home?

- APA Citations

- MLA Citations

- Get Research Help

- How-To Videos

- Research Guides

- Connect With A Librarian

- How do I get an ID?

- How do I get materials for classes?

- How do I borrow library items?

- How do I return library items?

- Where is my library account?

- Does the library have my textbooks?

- How do I visit the library space?

- How do I find a quiet place to study?

- Can I reserve a study room?

- Where can I use a desktop computer on campus?

- Where can I print on campus?

Service Alert

Library Services

Psychology Research Guide

- Library Information

- Start your project!

- Narrow your topic

- Explore Concepts and Issues

- C.R.A.A.P. Test

What is a peer-reviewed article?

- Find peer-reviewed articles

- Find good websites

- Explore controversial topics

- Cite your sources

What is peer review? (all 3 videos)

- peer-reviewed articles are written by subject experts

- these experts have advanced degrees , like PhD, MD, or EdD

- they write within specific academic disciplines , like organic chemistry or adolescent psychology

- they publish their research articles in peer-reviewed journals , also known as scholarly, academic, or "refereed" journals

What is peer review?

What does a peer-reviewed article look like?

Eli Moody, Vanderbilt University, 2007 . Used by permission.

How do I read a peer-reviewed article?

- << Previous: Find articles

- Next: Find peer-reviewed articles >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 9:29 AM

- URL: https://guides.kish.edu/psychology

The Role Of Peer Review In The Scientific Process

March 7, 2021 - paper 2 psychology in context | research methods.

- Back to Paper 2 - Research Methods

The Role of Peer Review in the Scientific Process

Psychology, in common with all scientific subjects, develops its knowledge base through conducting research and sharing the findings of such research with other scientists. Peer review is an essential part of this process and scientific quality is judged by it. It is in the interest of all scientists that their work is held up for scrutiny and that any work that is flawed or downright fraudulent is detected and its results ignored.

Why is Peer Review so Important?

In order to remember the answer to this question, it is good to use the mnemonic ‘People Make Very Interesting Statements!’

(1) P eople Prevent Plagiarism: Psychologists/Scientists carrying out a peer review can make sure that the work due to be published isn’t simply a regurgitation of work that has been published previously by other Psychologists or Scientists.

(2) M ake Methodology: Other researchers can check the report/study in terms of how appropriate the methodological choices were (e.g. sample of participants, (are they truly reflective of the target population?) research method (does the method used hinder reliability of ecological validity), design etc

(3) V ery- Validity: Other researchers can check the report/study for accuracy in terms of testing, measuring and results analysis. Researchers can make comments in terms of whether they feel the study is ecologically valid or holds high population validity.

(4) I nteresting Integrity: ( Integrity definition the quality of being honest and sound in construction). This helps to ensure that any research paper published in a well-respected journal has integrity and can, therefore, be taken seriously by fellow researchers and by lay people.

(5) S tatements Significant Peers are also in a position to judge the importance or significance of the research in a wider context, i.e. whether it’s relevant and worth doing, the implications of the research findings on world wide practices (e.g. looking at how research into attachment can inform practices in nurseries and schools etc )

Peer Reviews can also be used to:

(1) Allocate funding to Universities/decide on a rating for University departments based in the quality and impact of their research studies. For example, if a University is consistently producing high quality research that is having a massive/positive impact on the treatment of mental illnesses, it is likely that this University department will be awarded funding in order to continue with the production of this research.

(2) Suggest amendments and improvements reviewers may recommend that the procedure of the experiment is modified to make it more valid/accurate, they may suggest that the sample of participants used is expanded/increased to make the research hold higher population validity etc

- Psychopathology

- Social Psychology

- Approaches To Human Behaviour

- Biopsychology

- Research Methods

- Issues & Debates

- Teacher Hub

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- [email protected]

- www.psychologyhub.co.uk

We're not around right now. But you can send us an email and we'll get back to you, asap.

Start typing and press Enter to search

Cookie Policy - Terms and Conditions - Privacy Policy

Research in Psychology: Peer Review

- Topics & Keywords

- Peer Review

- Evaluating Articles

- Citation Resources This link opens in a new window

About Peer Review

What is Peer Review?

Peer review is the evaluation of scientific, academic, or professional work by others working in the same field.

Peer-reviewed articles are articles that have undergone a rigorous review process, by peers in their discipline, before publication in a scholarly journal

Why do we use peer reviewed articles?

Using a peer-reviewed article gives your argument more weight, since these articles have been vetted by experts.

How do I find peer reviewed articles?

The easiest way to find peer reviewed articles is to use a library database and use the "Limit to Peer Reviewed" check box. To learn more about how to use a library database go to the PsycINFO tab .

Peer Review in 3 Minutes

Video from North Carolina State University

- << Previous: Scholarly Articles

- Next: Evaluating Articles >>

- Last Updated: Dec 13, 2023 12:38 PM

- URL: https://libguides.hartford.edu/researchinpsychology

A-Z Site Index | Contact Us | Directions | Hours | Get Help

University of Hartford | 200 Bloomfield Avenue, West Hartford, CT 06117 Harrison Libraries © 2020 | 860.768.4264

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 05 December 2023

Reviewing a review

Nature Reviews Psychology volume 2 , page 715 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1287 Accesses

1 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Peer review

Peer review for a narrative review article can be quite different from the process for an empirical manuscript. We demystify the aims of and procedures for peer review at Nature Reviews Psychology .

All of our Review and Perspective articles are peer reviewed by experts in the field. Our peer review process for these papers has many broad similarities to peer review of empirical research papers. However, it also has a few unique aspects. For one thing, review-type articles do not report any original analyses, so there are no methodological details or statistical analyses to evaluate. Instead, papers in our journal should organize, synthesize and critically discuss the literature, as well as conveying recommendations for future research in the field.

Our instructions to reviewers echo these broad aims, as well as the specific aims of each article type. We ask reviewers whether the scope of the article is clear and whether the coverage of material is appropriate, both within the specific topic area and across the broader context of the field. For a Review, discussion of major theories or findings should be balanced, and any intentional omissions should be explained to the reader. For a Perspective, the authors should not ignore alternative points of view even as they centre their own account.

Another major aspect of the manuscript that we ask peer reviewers to consider is its timeliness: does the article provide a needed update, an authoritative synthesis, a unique angle or a useful framework? Importantly, we do not ask reviewers to evaluate the ‘novelty’ of a manuscript. Because reviews must be based in existing literature, a truly novel manuscript with only original ideas wouldn’t be a review at all!

Finally, we ask reviewers to evaluate how the paper might be received by our broad audience of researchers, academics and clinicians across psychology. We want our articles to strike a balance between authoritative and accessible so that a broad audience of topic experts and non-experts alike can benefit from their insights. That said, we want reviewers to focus on the article content. Writing issues such as typos, run-on sentences or grammatical mistakes will be addressed when the paper undergoes a detailed edit before publication.

Like editors at any journal, we aim to secure expert reviewers in each major topic covered by the manuscript. For some topics, we might invite researchers who don’t primarily consider themselves academics, such as clinicians or industry researchers. We aim for a diverse reviewer panel with respect to geographical location, racial and ethnic background, gender and career stage. All of these aspects can influence a reviewer’s evaluation of a manuscript, and a range of perspectives helps contribute to an overall evaluation that is fair and unbiased. Of course, we avoid reviewers with conflicts of interest, such as past or current collaborators.

The majority of our papers will go back to authors for a revision, and we want that revision to be as productive as possible. To that end, we annotate individual points of feedback in the peer review reports to help authors focus their revision efforts. We highlight comments that are particularly valuable or that we see having a substantial impact on the final article. For instance, some reviewers ask authors to motivate or reconsider a particular decision they made, such as to focus on a particular phenomenon, omit a specific outdated theory, or discuss topic A before topic B. Revisions in response to these types of request are often straightforward to implement but have a big impact on the eventual reader. We also adjudicate when two reviewers ask for opposing changes or make contradictory remarks, adding editorial guidance to help authors break the stalemate. Finally, we keep the scope and narrative cohesiveness of the article in mind. If a reviewer seems to be asking for the paper to be refocused around a different topic or wants extensive discussion of a tangential issue, we might tell authors that they can politely decline that particular piece of feedback. Ultimately, our aim is to provide authors with a clear path to a successful revision.

When we receive the revised version of a manuscript, we do a thorough read of the point-by-point rebuttal letter and the revised manuscript to determine whether the reviewers’ requests have been conscientiously addressed. Typical reviewer comments are about how concepts are explained, the space authors dedicate to discussing particular aspects of the literature, or alignment between the manuscript’s stated aims and its content. As professional editors with doctoral degrees in psychology, we are trained to evaluate the extent to which revisions to the text satisfy these types of reviewer concern; many manuscripts are not returned to peer reviewers for a second round after our evaluation. However, if substantial scientific information has been added or if we’re uncertain whether a reviewer’s concerns have been addressed, we will enlist all or a subset of the original peer reviewers to re-evaluate the manuscript.

“The peer review process…is a collaborative effort by the authors, the peer reviewers and the editor to bring out the best version of each article.”

The peer review process at Nature Reviews Psychology is designed to facilitate the transfer of critical yet constructive feedback between experts. It is a collaborative effort by the authors, the peer reviewers and the editor to bring out the best version of each article.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Reviewing a review. Nat Rev Psychol 2 , 715 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-023-00263-z

Download citation

Published : 05 December 2023

Issue Date : December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-023-00263-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Supporting the next generation of psychologists.

Nature Reviews Psychology (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Library Home

- Research Guides

Psychology - MIOP orientation

- What is Peer Review?

Library Research Guide

- Citing and Citation Managers

- Articles & Books

Peer Review Defined

What are peer-reviewed journals, characteristics of scholarly articles, using ulrich's.

- Other Questions?

Peer review is a quality control process used by publications to help ensure that only high quality, methodologically sound information is presented in the publication. In the peer review process, material submitted for publication is sent to individuals who are experts on the topic. Those experts read the material and suggest to the editor whether the material should be rejected, should be accepted, or should be sent back to the authors with a request for revisions.

Peer-reviewed journals are journals that use the peer review process (defined in the box above). Almost all peer-reviewed journals are scholarly journals.

According to Cornell University Libraries, there are several characteristics that define a scholarly journal:

- They generally have a more “serious” look meaning there’s less emphasis on glossy pages and fancy photographs and more put on text, graphs, and charts.

- Scholarly journals always cite their sources. This is usually in the form of footnotes or bibliographies.

- Articles are written by scholars in that particular field or who have done research in that field.

- The language of the article contains language used in that discipline.

- The author assumes the audience has some prior knowledge of the research or background in that field.

- Lastly, the purpose of a scholarly journal is to report on original research and make that information available to other people.

In your research, you will find articles from many different sources. The sources might be scholarly (intended to be used by scholars in the field), or they might be popular (intended to be used by the general public). Here are some things you can look for to determine if your article is scholarly:

- Look at the title. The title is usually a brief summary of the article often with specific terminology related to that field.

- Look at the authors. Are the author’s credentials at the beginning of the article or somewhere easily found? This helps establish the author’s authority as an expert in that field.

- Look for an abstract. This is the summary of the article. It helps readers determine whether the article suits their research needs. Sometimes it will even be labeled “Abstract.”

- Look for charts, graphs, tables, or equations. These are often found in scholarly research. Pictures are rare.

- Look for references. You will find these scattered throughout the article as footnotes or endnotes at the end of an article. Authors will usually also include a full reference list at the end of the article. This is a good way to find additional articles on your topic.

If you want to be absolutely sure a journal is peer reviewed, use the database Ulrich's International Periodicals Directory . Look up the journal by title. Titles that are peer reviewed are indicated by the black and white referee's jersey ("refereed" is another term for peer-reviewed.) Note that there may be some parts of the journal (e.g. letters to the editor, book reviews, etc.) that are not peer reviewed.

- << Previous: Articles & Books

- Next: Other Questions? >>

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 3:53 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.k-state.edu/miop

K-State Libraries

1117 Mid-Campus Drive North, Manhattan, KS 66506

785-532-3014 | [email protected]

- Statements and Disclosures

- Accessibility

- © Kansas State University

PsycInfo database: What is Peer Review?

- PsycInfo database

- What is Peer Review?

- Finding CITED REFERENCES in PsycInfo

- APA Style Guide

- Google Scholar This link opens in a new window

- Interlibrary Loan This link opens in a new window

- Librarian for Psychology

Peer-Review Video

Peer-Review in Three Minutes This three minute video describes and discusses the importance of peer-review and its process.

( NCSU video, 3:15 minutes)

What Does "Peer-Reviewed" or "Refereed" Mean?

Publications that do not use peer-review, such as Time, Discover, Newsweek, and U.S. News, rely on the judgment of the editors as to whether an article is quality material or not. Articles are not as rigorously reviewed because these publications do not rely on solid, scientific scholarship.

Finding Peer-Reviewed Articles

How do I know if a journal is peer-reviewed?

- Limit your results to peer-review. Most databases, including the library catalog, have an option to limit results to peer-review. If they don't, try adding "peer-review" as a search term.

- ALSO, just because a journal is deemed peer-reviewed does not mean every article in the journal is peer-reviewed. Book reviews, editorials, and other sections of a journal do not qualify as peer-reviewed.

Characteristics of Peer-Review

Gary Klein (librarian for Psychology)

- << Previous: PsycInfo database

- Next: Finding CITED REFERENCES in PsycInfo >>

- Last Updated: Nov 14, 2023 3:57 PM

- URL: https://libguides.willamette.edu/PsycInfo

Willamette University Libraries

Final dates! Join the tutor2u subject teams in London for a day of exam technique and revision at the cinema. Learn more →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Psychology news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Psychology Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Peer Review

Peer review is a process that takes place before a study is published to check the quality and validity of the research, and to ensure that the research contributes to its field. The process is carried out by experts in that particular field of psychology.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

Role of Peer Review in the Scientific Process

Study Notes

Research Methods: MCQ Revision Test 1 for AQA A Level Psychology

Topic Videos

Example Answers for Research Methods: A Level Psychology, Paper 2, June 2018 (AQA)

Exam Support

Example Answer for Question 19 Paper 2: A Level Psychology, June 2017 (AQA)

A level psychology topic quiz - research methods.

Quizzes & Activities

Our subjects

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

PEER REVIEW

the assessment of scientific or academic piece, like research or written pieces turned into journals for publishing, by other skilled professionals practicing in the same field.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Latest Posts

Stop Guessing: Here Are 3 Steps to Data-Driven Psychological Decisions

Getting Help with Grief: Understanding Therapy & How It Can Help

Exploring the Psychology of Risk and Reward

Understanding ADHD in Women: Symptoms, Treatment & Support

Meeting the Milestones: A Guide to Piaget's Child Developmental Stages

Counseling, Therapy, and Psychology: What Is The Difference?

The Psychology of Metaphysical Belief Systems

4 Key Considerations When Supporting a Loved One Through a Legal Battle for Justice

Finding Balance: The Psychological Benefits of Staying Active

The Psychology of Winning: Case Studies and Analysis from the World of Sports

Transitioning to Digital Therapy: Navigating the Pros and Cons

From Loss to Liberation: The Psychological Journey Of Seniors Receiving All-On-4 Dental Implants

Popular psychology terms, medical model, hypermnesia, affirmation, brainwashing, backup reinforcer, affiliative behavior, message-learning approach, gross motor.

Psychological Research

The Reliability and Validity of Research

Learning objectives.

- Define reliability and validity

Interpreting Experimental Findings

Once data is collected from both the experimental and the control groups, a statistical analysis is conducted to find out if there are meaningful differences between the two groups. A statistical analysis determines how likely any difference found is due to chance (and thus not meaningful). In psychology, group differences are considered meaningful, or significant, if the odds that these differences occurred by chance alone are 5 percent or less. Stated another way, if we repeated this experiment 100 times, we would expect to find the same results at least 95 times out of 100.

The greatest strength of experiments is the ability to assert that any significant differences in the findings are caused by the independent variable. This occurs because random selection, random assignment, and a design that limits the effects of both experimenter bias and participant expectancy should create groups that are similar in composition and treatment. Therefore, any difference between the groups is attributable to the independent variable, and now we can finally make a causal statement. If we find that watching a violent television program results in more violent behavior than watching a nonviolent program, we can safely say that watching violent television programs causes an increase in the display of violent behavior.

Reporting Research

When psychologists complete a research project, they generally want to share their findings with other scientists. The American Psychological Association (APA) publishes a manual detailing how to write a paper for submission to scientific journals. Unlike an article that might be published in a magazine like Psychology Today, which targets a general audience with an interest in psychology, scientific journals generally publish peer-reviewed journal articles aimed at an audience of professionals and scholars who are actively involved in research themselves.

Link to Learning

The Online Writing Lab (OWL) at Purdue University can walk you through the APA writing guidelines.

A peer-reviewed journal article is read by several other scientists (generally anonymously) with expertise in the subject matter. These peer reviewers provide feedback—to both the author and the journal editor—regarding the quality of the draft. Peer reviewers look for a strong rationale for the research being described, a clear description of how the research was conducted, and evidence that the research was conducted in an ethical manner. They also look for flaws in the study’s design, methods, and statistical analyses. They check that the conclusions drawn by the authors seem reasonable given the observations made during the research. Peer reviewers also comment on how valuable the research is in advancing the discipline’s knowledge. This helps prevent unnecessary duplication of research findings in the scientific literature and, to some extent, ensures that each research article provides new information. Ultimately, the journal editor will compile all of the peer reviewer feedback and determine whether the article will be published in its current state (a rare occurrence), published with revisions, or not accepted for publication.

Peer review provides some degree of quality control for psychological research. Poorly conceived or executed studies can be weeded out, and even well-designed research can be improved by the revisions suggested. Peer review also ensures that the research is described clearly enough to allow other scientists to replicate it, meaning they can repeat the experiment using different samples to determine reliability. Sometimes replications involve additional measures that expand on the original finding. In any case, each replication serves to provide more evidence to support the original research findings. Successful replications of published research make scientists more apt to adopt those findings, while repeated failures tend to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the original article and lead scientists to look elsewhere. For example, it would be a major advancement in the medical field if a published study indicated that taking a new drug helped individuals achieve a healthy weight without changing their diet. But if other scientists could not replicate the results, the original study’s claims would be questioned.

Dig Deeper: The Vaccine-Autism Myth and the Retraction of Published Studies

Some scientists have claimed that routine childhood vaccines cause some children to develop autism, and, in fact, several peer-reviewed publications published research making these claims. Since the initial reports, large-scale epidemiological research has suggested that vaccinations are not responsible for causing autism and that it is much safer to have your child vaccinated than not. Furthermore, several of the original studies making this claim have since been retracted.

A published piece of work can be rescinded when data is called into question because of falsification, fabrication, or serious research design problems. Once rescinded, the scientific community is informed that there are serious problems with the original publication. Retractions can be initiated by the researcher who led the study, by research collaborators, by the institution that employed the researcher, or by the editorial board of the journal in which the article was originally published. In the vaccine-autism case, the retraction was made because of a significant conflict of interest in which the leading researcher had a financial interest in establishing a link between childhood vaccines and autism (Offit, 2008). Unfortunately, the initial studies received so much media attention that many parents around the world became hesitant to have their children vaccinated (Figure 1). For more information about how the vaccine/autism story unfolded, as well as the repercussions of this story, take a look at Paul Offit’s book, Autism’s False Prophets: Bad Science, Risky Medicine, and the Search for a Cure.

Reliability and Validity

Everyday connection: how valid is the sat.

Standardized tests like the SAT are supposed to measure an individual’s aptitude for a college education, but how reliable and valid are such tests? Research conducted by the College Board suggests that scores on the SAT have high predictive validity for first-year college students’ GPA (Kobrin, Patterson, Shaw, Mattern, & Barbuti, 2008). In this context, predictive validity refers to the test’s ability to effectively predict the GPA of college freshmen. Given that many institutions of higher education require the SAT for admission, this high degree of predictive validity might be comforting.

However, the emphasis placed on SAT scores in college admissions has generated some controversy on a number of fronts. For one, some researchers assert that the SAT is a biased test that places minority students at a disadvantage and unfairly reduces the likelihood of being admitted into a college (Santelices & Wilson, 2010). Additionally, some research has suggested that the predictive validity of the SAT is grossly exaggerated in how well it is able to predict the GPA of first-year college students. In fact, it has been suggested that the SAT’s predictive validity may be overestimated by as much as 150% (Rothstein, 2004). Many institutions of higher education are beginning to consider de-emphasizing the significance of SAT scores in making admission decisions (Rimer, 2008).

In 2014, College Board president David Coleman expressed his awareness of these problems, recognizing that college success is more accurately predicted by high school grades than by SAT scores. To address these concerns, he has called for significant changes to the SAT exam (Lewin, 2014).

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Analyzing Findings. Authored by : OpenStax College. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/2-3-analyzing-findings . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

consistency and reproducibility of a given result

accuracy of a given result in measuring what it is designed to measure

General Psychology Copyright © by OpenStax and Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Memory: An Extended Definition

Gregorio zlotnik.

1 Clinique de la Migraine de Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada

Aaron Vansintjan

2 Department of Film, Media and Cultural Studies, Birkbeck, University of London, London, United Kingdom

Recent developments in science and technology point to the need to unify, and extend, the definition of memory. On the one hand, molecular neurobiology has shown that memory is largely a neuro-chemical process, which includes conditioning and any form of stored experience. On the other hand, information technology has led many to claim that cognition is also extended, that is, memory may be stored outside of the brain. In this paper, we review these advances and describe an extended definition of memory. This definition is largely accepted in neuroscience but not explicitly stated. In the extended definition, memory is the capacity to store and retrieve information. Does this new definition of memory mean that everything is now a form of memory? We stress that memory still requires incorporation, that is, in corpore . It is a relationship – where one biological or chemical process is incorporated into another, and changes both in a permanent way. Looking at natural and biological processes of incorporation can help us think of how incorporation of internal and external memory occurs in cognition. We further argue that, if we accept that there is such a thing as the storage of information outside the brain – and that this organic, dynamic process can also be called “memory” – then we open the door to a very different world. The mind is not static. The brain, and the memory it uses, is a work in progress; we are not now who we were then.

Introduction

In the short story “Funes, the memorious,” Jorge Luis Borges invites us to imagine a man, Funes, who cannot forget anything. The narrator is ashamed in the inexactness of his retelling: his own memory is “remote and weak,” in comparison to that of his subject, which resembles “a stammering greatness.” Unlike Funes, he says, “we all live by leaving behind” – life is impossible without forgetting. He goes on to note that, even though Funes could remember every split second, he couldn’t classify or abstract from his memories. “To think is to forget a difference, to generalize, to abstract.” The reader may be led to wonder how Funes’ brain has the capacity to store all of that memory. doesn’t it reach its limits at some point? Borges leaves that question to our imagination.

In popular culture, memory is often thought of as some kind of physical thing that is stored in the brain; a subjective, personal experience that we can recall at will. This way of thinking about memory has led many to wonder if there is a maximum amount of memories we can have. But, this idea of memory is at odds with advances in the science of memory over the last century: memory isn’t really a fixed thing stored in the brain, but is more of a chemical process between neurons, which is not static. What’s more, advances in information technology are pushing our understanding of memory into new directions. We now talk about memory on a hard drive, or as a chemical change between neurons. Yet, these different definitions of memory continue to co-exist. A more narrow definition of memory, as the storage of experiences in the brain, is increasingly at odds with an extended definition, which acknowledges these advances. However, while this expanded definition is often implicitly used, it is rarely explicitly acknowledged or stated. Today, the question is no longer, how many memories can we possibly have, but, how is the vast amount of memory we process on a daily basis integrated into cognition?

In this paper, we outline these advances and the currently accepted definitions of memory, arguing that these necessarily imply that we should today adopt an extended definition. In the following, we first describe some key advances in the science of memory, cognitive theory, and information technology. These suggest to us that we are already using a unified, and extended, definition of memory, but rarely made explicit. Does this new definition of memory mean that everything is now a form of memory? We argue that looking at natural and biological processes of incorporation can help us think of how incorporation of internal and external memory occurs in cognition. Finally, we note some of the implications of this extended definition of memory.

Background: Advances in the Science of Memory

Already in the 19th century, the recognition that the number of neurons in the brain doesn’t increase significantly after reaching adulthood suggested to early neuroanatomists that memories aren’t primarily stored through the creation of neurons, but rather through the strengthening of connections between neurons ( Ramón y Cajal, 1894 ). In 1966, the breakthrough discovery of long-term potentiation (LTP) suggested that memories may be encoded in the strength of synaptic signals between neurons ( Bliss and Lømo, 1973 ). And so we started understanding memory as a neuro-chemical process. The studies by Eric Kandel of the Aplysia californica , for which he won the Nobel prize, for example, show that classical conditioning is a basic form of memory storage and is observable on a molecular level within simple organisms ( Kandel et al., 2012 ). This in effect expanded the definition of memory to include storage of information in the neural networks of simple lifeforms. Increasingly, researchers are exploring the chemistry behind memory development and recall, suggesting these molecular processes can lead to psychological adaptations (e.g., Coderre et al., 2003 ; Laferrière et al., 2011 ).

Memory is today defined in psychology as the faculty of encoding, storing, and retrieving information ( Squire, 2009 ). Psychologists have found that memory includes three important categories: sensory, short-term, and long-term. Each of these kinds of memory have different attributes, for example, sensory memory is not consciously controlled, short-term memory can only hold limited information, and long-term memory can store an indefinite amount of information.

Key to the emerging science of memory is the question of how memory is consolidated and processed. Long-term storage of memories happens on a synaptic level in most organisms ( Bramham and Messaoudi, 2005 ), but, in complex organisms like ourselves, there is also a second form of memory consolidation: systems consolidation moves, processes, and more permanently stores memories ( Frankland and Bontempi, 2005 ). Today, there are many models of how memory is consolidated in cognition. Single-system models posit that the hippocampus supports the neocortex in encoding and storing long-term memories through strengthening connections, finally leading the memory to become independent from the hippocampus (Ibid.). Multiple-trace theory instead proposes that each memory has a unique code or memory trace, which continues to involve the hippocampus to an extent ( Hintzman and Block, 1971 ; Hintzman, 1986 , 1990 ; Whittlesea, 1987 ; Versace et al., 2014 ; Briglia et al., 2018 ). In another theory, memory is understood as a form of negative entropy or rich energy ( Wiener, 1961 , 1988 ), which is then processed in a way that minimizes the expenditure of energy by the brain ( Friston, 2010 ; Van der Helm, 2016 ). Our heightened capacity to store information may be due to our ability to reduce disorder and process large amounts of information rapidly, a necessarily non-linear process ( Wiener, 1961 , 1988 ). The forgetting and fading of memories is also understood as being an important aspect of the functioning and utility of these memories ( Staniloiu and Markowitsch, 2012 ). As with a computer hard drive, memories can also be “corrupted” – false memories are commonly studied within forensic psychology ( Loftus, 2005 ). Together, these advances highlight how different kinds of memory storage are non-linear – that is, subject to complex systems interactions – contextual, and plastic. They also shed light on why, and how, we are able to live with such large quantities of information. It may not be that Funes has the special ability to remember everything, but that he lacks our ability to incorporate, and sort through, a potentially infinite amount of information.

The advance of the fields of genetics and epigenetics has also given us new metaphors to describe memory. We understand DNA as a structure that carries information that we call “genetic code” – kind of like a computer chip for biological processes. Today, the metaphor has come full circle and we can now use DNA to store and extract digital data ( Church et al., 2012 ). The study of epigenetics suggests that simple lifeforms pass on memories across generations through genetic code ( Klosin et al., 2017 ; Posner et al., 2019 ), suggesting a need to study whether humans and other complex life forms may do so as well. With these advances, our understanding of how memory is stored has expanded once again.

Further, we can now store memory in places that we haven’t been able to before. Smartphones, mind-controlled prosthetic limbs, and Google Glasses all offer new ways to store information and thereby interact with our surroundings. Our ability to produce information alters how we perceive the world, with far-reaching implications. As Stephen Hawking, the Nobel prize-winning physicist explained in his 1996 lecture, “Life in the universe,”

What distinguishes us from [our ancestors], is the knowledge that we have accumulated over the last 10000 years, and particularly, over the last three hundred. I think it is legitimate to take a broader view, and include externally transmitted information, as well as DNA, in the evolution of the human race ( Hawking, 1996 ).

The sheer quantity of available information today, as well as developments in an understanding of memory – from fixed and physical to dynamic, chemical, and a process of rich energy transfer – lead to a very different picture of memory than the one we had 100 years ago. Memory seems to exist everywhere, from an Aplysia ’s ganglion to DNA to a hard drive.

To account for these developments, cognitive scientists now propose that human cognition is actually extended beyond the brain in ways that theories of the mind did not previously recognize ( Clark and Chalmers, 1998 ; Clark, 2008 ). This approach is being called 4E cognition (Embodied, Embedded, Extended, and Enactive). For example, enactivism posits that cognition is a dynamic interaction between an organism and its environment ( Varela et al., 1991 ; Chemero, 2009 ; Menary, 2010 ; Rowlands, 2010 ; Favela and Chemero, 2016 ; Briglia et al., 2018 ). According to this framework, cognition is a process of incorporation between the environment and the body/brain/mind. To be clear, cognition is not incorporated in the surroundings, only the corpus can incorporate, and thus cognition (or what we call “mind”) is a product of the interaction between the brain, the body, and the environment.

Extending Memory

These developments indicate that we need to reconceptualize our definition of memory. What is the difference between trying to recall a childhood experience, and searching for an important email archived years ago? This distinction is best represented through the difference in how we use the words “memory” and “memories.” Usually, “memories” tends to refer to events recalled from the past, which are seen as more representational and subjective. In contrast, “memory” now is used to refer to storage of information in general , including in DNA, digital information storage, and neuro-chemical processes. Today, science has moved far beyond a popular understanding of memory as fixed, subjective, and personal. In the extended definition, it is simply the capacity to store and retrieve information . To illustrate why memory has extended beyond this original use, we want to ask the reader: what do a stressed-out driver and a snail have in common?

(1). A homeowner has been trying to sell her house for a year, and worrying about it. One day, she’s driving to work and becomes extremely anxious, for no apparent reason. She wasn’t thinking of anything in particular at the time. Confused, she looks around, and notices a billboard advertising a real estate agency. She realizes that she had seen it out of the corner of her eye, and her brain had then processed the information while she was thinking of something else, which then triggered the anxiety attack.

(2). Consider a nerve cell of an A. californica , a kind of sea snail, which is prodded vigorously for a short time period, provoking an immediate withdrawal response. Shortly afterward, it is prodded less intensely, but, it elicits the same withdrawal response. It is found that the slugs’ nerve cell is sensitive for up to 24 h – the nerve cells “remember” past pain.

Each example illustrates a different kind of chemical, biological process. In the first example, an outside stimulus triggers a stress response for the homeowner. We can surmise that though she didn’t “remember” anything, non-consciously, she did. In the second example, the snail certainly “remembers” the provocation, even though this memory is only stored in a few cells. But can we really call this memory?

However, on closer examination, we are forced to concede that each of them should be called a form of memory. First, consider the homeowner: her brain “remembers” something that does not occur to her as a conscious thought. It is clearly a chemical process occurring in the background. Most would grant that this would nevertheless be a form of memory, as it involves recalling information stored in her brain. Already, a broader definition of memory is used that does not imply conscious attention. Now, consider the snail: it is also storing information chemically. Once again, this does not involve a conscious, subjective process of storing and remembering – it is purely reactive, but information is being stored and recalled nonetheless. We would need to concede that if the homeowner’s experience counts as memory, then the slug’s automatic response does as well. There is in fact little difference between the first two examples: there is a transfer of information that causes a reaction. Both should be considered forms of memory.

A Slippery Slope?

If we agree with this expanded definition of memory, then it follows that experience is also a form of stored information, kinds of memory . We are not saying that a particular experience, as an event , is a memory. Rather, we here use the word “experience” as connoted by the phrase “an experienced driver,” an “experienced writer.” They have a set of experiences, remembered through practice, and retrieved when they drive, or write. When we accumulate knowledge, information, and techniques, then the accumulation of those separate processes constitute experience . This experience involves retrieval of information, conversely, being experienced is the process of retrieving memory.

Under this definition, even immunological and allergy processes may be considered memory. There is a storage of information of the allergen or the viral/bacterial aggressor and when the aggressor or allergen re-appears there is a cascade of inflammatory processes. This can be considered the storage and retrieval of information, and thus a form of memory. This does not contradict the accepted definition of memory within psychology, as it is still seen as the ability to encode, store, and recall information. Rather, it extends it to processes not just bound by the brain.

If memory is indeed defined as “the capacity to store and/or retrieve information,” then this may lead anyone to ask – what isn’t memory? Wouldn’t this definition of memory be far too broad, and include a vast range of phenomena? Is the extended definition of memory, as is being proposed by neurobiologists and cognitive theorists, a slippery slope?

As we suggested above, however, memory still involves a process of incorporation, that is, requiring a corpus . While memory may be stored on the cloud, it requires a system of incorporation with the body and therefore the mind. In other words, the “cloud” by itself is not memory, but operates through an infrastructure (laptops, smart phones, Google Glasses) that are integrated with the brain-mind through learned processes of storage and recall. The conditioning of an Aplysia ’s ganglion is incorporated into an organism. Memory, it seems, is not just mechanistic, but a dynamic process. It is a relationship – where one biological or chemical process is incorporated into another, and changes both in a permanent way. A broadened definition must account for this dynamic relationship between organisms and their environment.

How can we understand this process of incorporation? It appears that symbiotic incorporation of biological processes is quite common in nature. Recent studies offer more evidence that early cells acquired mitochondria by, at some point, incorporating external organisms into their own cell structure ( Thrash et al., 2011 ; Ferla et al., 2013 ). Mitochondria have their own genome, which is similar to that of bacteria. What was once a competitor and possibly a parasite became absorbed into the organism – and yet, the mitochondrion was not fully incorporated and retains many of its own processes of self-organization and memory storage, separate from the cell it resides in. This evolutionary process highlights the way by which external properties may become incorporated into the internal, changing both. Looking at natural and biological processes of incorporation can help us think of how incorporation of internal and external memory occurs in cognition.

Implications

This extended definition of memory may seem ludicrous and hard to accept. You may be tempted to throw up your hands and go back to the old, restricted, definition of memory – one that requires the transmission of subjective memories.

We beg you not to. There are several benefits of this approach to memory. First, in biology, expanding the definition of memory helps us shift from a focus on “experience” (which suggests an immaterial event) to a more material phenomenon: a deposit of events that may be stored and used afterward. By expanding the concept of memory, the study of memory within molecular neurobiology becomes more relevant and important. This expanded definition is in large part already widely accepted, for example, in Kandel’s Aplysia , conditioning is acknowledged to be a part of memory, and memory is not a part of conditioning. Memory would become the umbrella for learning, conditioning, and other processes of the mind/brain. Doing so changes the frame of observation from one which understands memory as a narrow, particular process, to one which understands it as a dynamic, fluid, and interactive phenomenon, neither just chemical or digital but integrated into our experience through multiple media. Second, it helps to conceptualize the relationship between biology, psychology, cognitive science, and computer science – as all three involve studying the transfer of information.

Third, it opens up an interesting way to imagine our own future. If we accept that there is such a thing as the storage of information outside the brain – and that this organic, dynamic process can also be called “memory” – then we open the door to a very different world. The mind is not static. Rather, like early cells acquiring mitochondria, it incorporates information from its surroundings, which in turn changes it. The brain, and the memory it uses, is a work in progress; we are not now who we were then. Many have already noted the extent to which we are cyborgs ( Harraway, 1991 ; Clark, 2003 , 2005 ); this neat line between human and technology may become more and more blurred as we develop specialized tools to store all kinds of information in our built environment. In what ways will the mind-brain function differently as it becomes increasingly more incorporated in its milieu, relying on it for information storage and processing?

Now let’s talk about Funes. His inability to forget his memories may seem familiar to some, a metaphor for our current condition. We may now recognize a bit of ourselves in him: we don’t see limits in our capacity to store new information, and the sheer availability of it is sometimes overwhelming. Even without the arrival of the Information Age, we carry with us through life a heavy load of disappointments, broken dreams, little tragedies and many memories. We know that forgetting is a must and a challenge. Yet, we are learning rapidly how to incorporate and use the massive amounts of data now available to us. The main challenge for each of us is to harness and control the unleashed powers given to us by technology. The future is uncertain, but some things remain the same. As Kandel (2007 , p. 10) wrote, “We are who we are in great measure because of what we learn, and what we remember.”

Author Contributions

GZ and AV drafted and edited the manuscript. Both authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Michael Lifshitz, Ph.D. for reading an early copy of this article and providing feedback. The authors also wish to thank Steven J. Lynn, Alan M. Rapoport, and Morgan Craig for the feedback and encouragement.

- Bliss T., Lømo T. (1973). Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J. Physiol. 232 331–356. 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bramham C. R., Messaoudi E. (2005). BDNF function in adult synaptic plasticity: the synaptic consolidation hypothesis. Prog. Neurobiol. 76 99–125. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.06.003 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Briglia J., Servajean P., Michalland A. H., Brunel L., Brouillet D. (2018). Modeling an enactivist multiple-trace memory. ATHENA: a fractal model of human memory. J. Math. Psychol. 82 97–110. 10.1016/j.jmp.2017.12.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chemero A. (2009). Radical Embodied Cognitive Science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Church G. M., Gao Y., Kosuri S. (2012). Next-generation digital information storage in DNA. Science 337 : 1628 . 10.1126/science.1226355 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clark A. (2003). Natural-Born Cyborgs: Minds, Technologies, and the Future of Human Intelligence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clark A. (2005). “Intrinsic content, active memory and the extended mind”. Analysis 65 1–11. 10.1111/j.1467-8284.2005.00514.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clark A. (2008). Supersizing the Mind: Embodiment, Action, and Cognitive Extension OUP. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clark A., Chalmers D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis 58 7–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coderre T. J., Mogil J. S., Bushnell M. C. (2003). “ The biological psychology of pain ,” in Handbook of Psychology , eds Gallagher M., Nelson R. J. (New York, NY: Wiley; ), 237–268. [ Google Scholar ]

- Favela L. H., Chemero A. (2016). “ The animal-environment system ,” in Foundations of Embodied Cognition: Perceptual and Emotional Embodiment , eds Coello Y., Fischer M. H. (New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; ), 59–74. [ Google Scholar ]