Psychological Theories of Depression

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

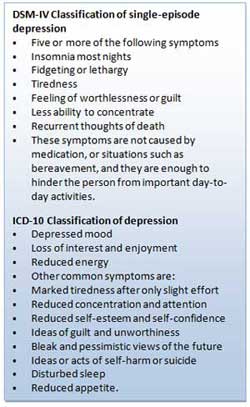

Depression is a mood disorder that prevents individuals from leading a normal life at work, socially, or within their family. Seligman (1973) referred to depression as the ‘common cold’ of psychiatry because of its frequency of diagnosis.

Depending on how data are gathered and how diagnoses are made, as many as 27% of some population groups may be suffering from depression at any one time (NIMH, 2001; data for older adults).

Behaviorist Theory

Behaviorism emphasizes the importance of the environment in shaping behavior. The focus is on observable behavior and the conditions through which individuals” learn behavior, namely classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and social learning theory.

Therefore, depression is the result of a person’s interaction with their environment.

For example, classical conditioning proposes depression is learned through associating certain stimuli with negative emotional states. Social learning theory states behavior is learned through observation, imitation, and reinforcement.

Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning states that depression is caused by the removal of positive reinforcement from the environment (Lewinsohn, 1974). Certain events, such as losing your job, induce depression because they reduce positive reinforcement from others (e.g., being around people who like you).

Depressed people usually become much less socially active. In addition, depression can also be caused by inadvertent reinforcement of depressed behavior by others.

For example, when a loved one is lost, an important source of positive reinforcement has lost as well. This leads to inactivity. The main source of reinforcement is now the sympathy and attention of friends and relatives.

However, this tends to reinforce maladaptive behavior, i.e., weeping, complaining, and talking of suicide. This eventually alienates even close friends leading to even less reinforcement and increasing social isolation and unhappiness. In other words, depression is a vicious cycle in which the person is driven further and further down.

Also, if the person lacks social skills or has a very rigid personality structure, they may find it difficult to make the adjustments needed to look for new and alternative sources of reinforcement (Lewinsohn, 1974). So they get locked into a negative downward spiral.

Critical Evaluation

Behavioral/learning theories make sense in terms of reactive depression, where there is a clearly identifiable cause of depression. However, one of the biggest problems for the theory is that of endogenous depression. This is depression that has no apparent cause (i.e., nothing bad has happened to the person).

An additional problem of the behaviorist approach is that it fails to consider cognitions (thoughts) influence on mood.

Psychodynamic Theory

During the 1960s, psychodynamic theories dominated psychology and psychiatry. Depression was understood in terms of the following:

- inwardly directed anger (Freud, 1917),

- introjection of love object loss,

- severe super-ego demands (Freud, 1917),

- excessive narcissistic , oral, and/or anal personality needs (Chodoff, 1972),

- loss of self-esteem (Bibring, 1953; Fenichel, 1968), and

- deprivation in the mother-child relationship during the first year (Kleine, 1934).

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory is an example of the psychodynamic approach . Freud (1917) proposed that many cases of depression were due to biological factors.

However, Freud also argued that some cases of depression could be linked to loss or rejection by a parent. Depression is like grief in that it often occurs as a reaction to the loss of an important relationship.

However, there is an important difference because depressed people regard themselves as worthless. What happens is that the individual identifies with the lost person so that repressed anger towards the lost person is directed inwards towards the self. The inner-directed anger reduces the individual’s self-esteem and makes him/her vulnerable to experiencing depression in the future.

Freud distinguished between actual losses (e.g., the death of a loved one) and symbolic losses (e.g., the loss of a job). Both kinds of losses can produce depression by causing the individual to re-experience childhood episodes when they experience loss of affection from some significant person (e.g., a parent).

Later, Freud modified his theory stating that the tendency to internalize lost objects is normal and that depression is simply due to an excessively severe super-ego. Thus, the depressive phase occurs when the individual’s super-ego or conscience is dominant. In contrast, the manic phase occurs when the individual’s ego or rational mind asserts itself, and s/he feels control.

In order to avoid loss turning into depression, the individual needs to engage in a period of mourning work, during which s/he recalls memories of the lost one.

This allows the individual to separate himself/herself from the lost person and reduce inner-directed anger. However, individuals very dependent on others for their sense of self-esteem may be unable to do this and so remain extremely depressed.

Psychoanalytic theories of depression have had a profound impact on contemporary theories of depression.

For example, Beck’s (1983) model of depression was influenced by psychoanalytic ideas such as the loss of self-esteem (re: Beck’s negative view of self), object loss (re: the importance of loss events), external narcissistic deprivation (re: hypersensitivity to loss of social resources) and oral personality (re: sociotropic personality).

However, although highly influential, psychoanalytic theories are difficult to test scientifically. For example, its central features cannot be operationally defined with sufficient precision to allow empirical investigation. Mendelson (1990) concluded his review of psychoanalytic theories of depression by stating:

“A striking feature of the impressionistic pictures of depression painted by many writers is that they have the flavor of art rather than of science and may well represent profound personal intuitions as much as they depict they raw clinical data” (p. 31).

Another criticism concerns the psychanalytic emphasis on the unconscious, intrapsychic processes, and early childhood experience as being limiting in that they cause clinicians to overlook additional aspects of depression. For example, conscious negative self-verbalization (Beck, 1967) or ongoing distressing life events (Brown & Harris, 1978).

Cognitive Explanation of Depression

This approach focuses on people’s beliefs rather than their behavior. Depression results from systematic negative bias in thinking processes.

Emotional, behavioral (and possibly physical) symptoms result from cognitive abnormality. This means that depressed patients think differently from clinically normal people. The cognitive approach also assumes changes in thinking precede (i.e., come before) the onset of a depressed mood.

Beck’s (1967) Theory

One major cognitive theorist is Aaron Beck. He studied people suffering from depression and found that they appraised events in a negative way.

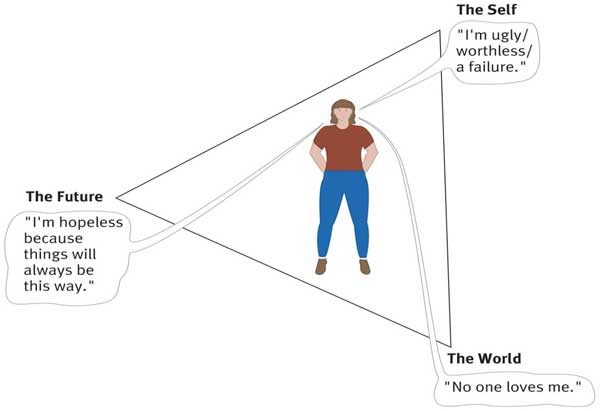

Beck (1967) identified three mechanisms that he thought were responsible for depression:

The cognitive triad (of negative automatic thinking) Negative self schemas Errors in Logic (i.e. faulty information processing)

The cognitive triad is three forms of negative (i.e., helpless and critical) thinking that are typical of individuals with depression: namely, negative thoughts about the self, the world, and the future. These thoughts tended to be automatic in depressed people as they occurred spontaneously.

For example, depressed individuals tend to view themselves as helpless, worthless, and inadequate. They interpret events in the world in an unrealistically negative and defeatist way, and they see the world as posing obstacles that can’t be handled.

Finally, they see the future as totally hopeless because their worthlessness will prevent their situation from improving.

As these three components interact, they interfere with normal cognitive processing, leading to impairments in perception, memory, and problem-solving, with the person becoming obsessed with negative thoughts.

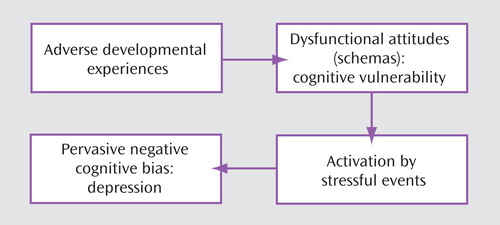

Beck believed that depression-prone individuals develop a negative self-schema . They possess a set of beliefs and expectations about themselves that are essentially negative and pessimistic. Beck claimed that negative schemas might be acquired in childhood as a result of a traumatic event. Experiences that might contribute to negative schemas include:

- Death of a parent or sibling.

- Parental rejection, criticism, overprotection, neglect, or abuse.

- Bullying at school or exclusion from a peer group.

However, a negative self-schema predisposes the individual to depression, and therefore someone who has acquired a cognitive triad will not necessarily develop depression.

Some kind of stressful life event is required to activate this negative schema later in life. Once the negative schema is activated, a number of illogical thoughts or cognitive biases seem to dominate thinking .

People with negative self-schemas become prone to making logical errors in their thinking, and they tend to focus selectively on certain aspects of a situation while ignoring equally relevant information.

Beck (1967) identified a number of systematic negative biases in information processing known as logical errors or faulty thinking. These illogical thought patterns are self-defeating and can cause great anxiety or depression for the individual. For example:

- Arbitrary Inference: Drawing a negative conclusion in the absence of supporting data.

- Selective Abstraction: Focusing on the worst aspects of any situation.

- Magnification and Minimisation: If they have a problem, they make it appear bigger than it is. If they have a solution they make it smaller.

- Personalization: Negative events are interpreted as their fault.

- Dichotomous Thinking: Everything is seen as black and white. There is no in between.

Such thoughts exacerbate and are exacerbated by the cognitive triad. Beck believed these thoughts or this way of thinking become automatic.

When a person’s stream of automatic thoughts is very negative, you would expect a person to become depressed. Quite often these negative thoughts will persist even in the face of contrary evidence.

Alloy et al. (1999) followed the thinking styles of young Americans in their early 20s for six years. Their thinking style was tested, and they were placed in either the ‘positive thinking group’ or ‘negative thinking group’.

After six years, the researchers found that only 1% of the positive group developed depression compared to 17% of the ‘negative’ group. These results indicate there may be a link between cognitive style and the development of depression.

However, such a study may suffer from demand characteristics. The results are also correlational. It is important to remember that the precise role of cognitive processes is yet to be determined. The maladaptive cognitions seen in depressed people may be a consequence rather than a cause of depression.

Learned Helplessness

Martin Seligman (1974) proposed a cognitive explanation of depression called learned helplessness .

According to Seligman’s learned helplessness theory, depression occurs when a person learns that their attempts to escape negative situations make no difference.

Consequently, they become passive and will endure aversive stimuli or environments even when escape is possible.

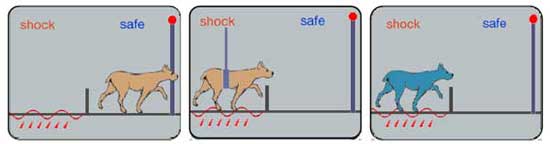

Seligman based his theory on research using dogs.

A dog put into a partitioned cage learns to escape when the floor is electrified. If the dog is restrained whilst being shocked, it eventually stops trying to escape.

Dogs subjected to inescapable electric shocks later failed to escape from shocks even when it was possible to do so. Moreover, they exhibited some of the symptoms of depression found in humans (lethargy, sluggishness, passive in the face of stress, and appetite loss).

This led Seligman (1974) to explain depression in humans in terms of learned helplessness , whereby the individual gives up trying to influence their environment because they have learned that they are helpless as a consequence of having no control over what happens to them.

Although Seligman’s account may explain depression to a certain extent, it fails to take into account cognitions (thoughts). Abramson, Seligman, and Teasdale (1978) consequently introduced a cognitive version of the theory by reformulating learned helplessness in terms of attributional processes (i.e., how people explain the cause of an event).

The depression attributional style is based on three dimensions, namely locus (whether the cause is internal – to do with a person themselves, or external – to do with some aspect of the situation), stability (whether the cause is stable and permanent or unstable and transient) and global or specific (whether the cause relates to the “whole” person or just some particular feature characteristic).

In this new version of the theory, the mere presence of a negative event was not considered sufficient to produce a helpless or depressive state. Instead, Abramson et al. argued that people who attribute failure to internal, stable, and global causes are more likely to become depressed than those who attribute failure to external, unstable, and specific causes.

This is because the former attributional style leads people to the conclusion that they are unable to change things for the better.

Gotlib and Colby (1987) found that people who were formerly depressed are actually no different from people who have never been depressed in terms of their tendencies to view negative events with an attitude of helpless resignation.

This suggests that helplessness could be a symptom rather than a cause of depression. Moreover, it may be that negative thinking generally is also an effect rather than a cause of depression.

Humanist Approach

Humanists believe that there are needs that are unique to the human species. According to Maslow (1962), the most important of these is the need for self-actualization (achieving our potential). The self-actualizing human being has a meaningful life. Anything that blocks our striving to fulfill this need can be a cause of depression. What could cause this?

- Parents impose conditions of worth on their children. I.e., rather than accepting the child for who s/he is and giving unconditional love , parents make love conditional on good behavior. E.g., a child may be blamed for not doing well at school, develop a negative self-image and feel depressed because of a failure to live up to parentally imposed standards.

- Some children may seek to avoid this by denying their true selves and projecting an image of the kind of person they want to be. This façade or false self is an effort to please others. However, the splitting off of the real self from the person you are pretending to cause hatred of the self. The person then comes to despise themselves for living a lie.

- As adults, self-actualization can be undermined by unhappy relationships and unfulfilling jobs. An empty shell marriage means the person is unable to give and receive love from their partner. An alienating job means the person is denied the opportunity to be creative at work.

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E., & Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: critique and reformulation . Journal of abnormal psychology, 87(1) , 49.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Whitehouse, W. G., Hogan, M. E., Tashman, N. A., Steinberg, D. L., … & Donovan, P. (1999). Depressogenic cognitive styles : Predictive validity, information processing and personality characteristics, and developmental origins. behavior research and therapy, 37(6) , 503-531.

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Causes and treatment . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., & Harrison, R. (1983). Cognitions, attitudes and personality dimensions in depression. British Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy .

Bibring, E. (1953). The mechanism of depression .

Brown, G. W., & Harris, T. (1978). Social origins of depression: a reply. Psychological Medicine, 8(04) , 577-588.

Chodoff, P. (1972). The depressive personality: A critical review. Archives of General Psychiatry, 27(5) , 666-673.

Fenichel, O. (1968). Depression and mania. The Meaning of Despair . New York: Science House.

Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and melancholia. Standard edition, 14(19) , 17.

Gotlib, I. H., & Colby, C. A. (1987). Treatment of depression: An interpersonal systems approach. Pergamon Press.

Klein, M. (1934). Psychogenesis of manic-depressive states: contributions to psychoanalysis . London: Hogarth.

Lewinsohn, P. M. (1974). A behavioral approach to depression .

Maslow, A. H. (1962). Towards a psychology of being . Princeton: D. Van Nostrand Company.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2001). Depression research at the National Institute of Mental Health http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression/complete-index.shtml.

Seligman, M. E. (1973). Fall into helplessness. Psychology today, 7(1) , 43-48.

Seligman, M. E. (1974). Depression and learned helplessness . John Wiley & Sons.

Further Information

- List of Support Groups

- Campaign against Living Miserably

- Men do cry: one man’s experience of depression

- NHS Self Help Guides

Depression: A cognitive perspective

Affiliations.

- 1 University of British Columbia, Canada. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Stanford University, United States.

- PMID: 29961601

- DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.008

Cognitive science has been instrumental in advancing our understanding of the onset, maintenance, and treatment of depression. Research conducted over the last 50 years supports the proposition that depression and risk for depression are characterized by the operation of negative biases, and often by a lack of positive biases, in self-referential processing, interpretation, attention, and memory, as well as the use of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies. There is also evidence to suggest that deficits in cognitive control over mood-congruent material underlie these cognitive processes. Specifically, research indicates that difficulty inhibiting and disengaging from negative material in working memory: (1) increases the use of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (e.g., rumination), decreases the use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies (e.g., reappraisal), and potentially impedes flexible selection and implementation of emotion regulation strategies; (2) is associated with negative biases in attention; and (3) contributes to negative biases in long-term memory. Moreover, studies suggest that these cognitive processes exacerbate and sustain the negative mood that typifies depressive episodes. In this review, we present evidence in support of this conceptualization of depression and discuss implications of research findings for theory and practice. Finally, we advance directions for future research.

Keywords: Cognition; Cognitive control; Depression; Emotion regulation strategies; Information-processing biases.

Copyright © 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Adaptation, Psychological / physiology*

- Cognitive Dysfunction / physiopathology*

- Depressive Disorder / physiopathology*

- Emotional Regulation / physiology*

- Executive Function / physiology*

Grants and funding

- R37 MH101495/MH/NIMH NIH HHS/United States

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

The Evolution of the Cognitive Model of Depression and Its Neurobiological Correlates

- Aaron T. Beck M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

Although the cognitive model of depression has evolved appreciably since its first formulation over 40 years ago, the potential interaction of genetic, neurochemical, and cognitive factors has only recently been demonstrated. Combining findings from behavioral genetics and cognitive neuroscience with the accumulated research on the cognitive model opens new opportunities for integrated research. Drawing on advances in cognitive, personality, and social psychology as well as clinical observations, expansions of the original cognitive model have incorporated in successive stages automatic thoughts, cognitive distortions, dysfunctional beliefs, and information-processing biases. The developmental model identified early traumatic experiences and the formation of dysfunctional beliefs as predisposing events and congruent stressors in later life as precipitating factors. It is now possible to sketch out possible genetic and neurochemical pathways that interact with or are parallel to cognitive variables. A hypersensitive amygdala is associated with both a genetic polymorphism and a pattern of negative cognitive biases and dysfunctional beliefs, all of which constitute risk factors for depression. Further, the combination of a hyperactive amygdala and hypoactive prefrontal regions is associated with diminished cognitive appraisal and the occurrence of depression. Genetic polymorphisms also are involved in the overreaction to the stress and the hypercortisolemia in the development of depression—probably mediated by cognitive distortions. I suggest that comprehensive study of the psychological as well as biological correlates of depression can provide a new understanding of this debilitating disorder.

I was privileged to start my research on depression at a time when the modern era of systematic clinical and biological research was just getting underway. Consequently, the field for new investigations was wide open. The climate at the time was friendly for such research. The National Institute of Mental Health had only recently been funding research and providing salary support for full-time clinical investigators. The Group for Advancement of Psychiatry, under the leadership of pioneers like David Hamburg, was providing guidelines as well as the impetus for clinical research.

Caught up with the contagion of the times, I was prompted to start something on my own. I was particularly intrigued by the paradox of depression. This disorder appeared to violate the time-honored canons of human nature: the self-preservation instinct, the maternal instinct, the sexual instinct, and the pleasure principle. All of these normal human yearnings were dulled or reversed. Even vital biological functions like eating or sleeping were attenuated. The leading causal theory of depression at the time was the notion of inverted hostility. This seemed a reasonable, logical explanation if translated into a need to suffer. The need to punish one’s self could account for the loss of pleasure, loss of libido, self-criticism, and suicidal wishes and would be triggered by guilt. I was drawn to conducting clinical research in depression because the field was wide open—and besides, I had a testable hypothesis.

Cross-Sectional Model of Depression

I decided at first to make a foray into the “deepest” level: the dreams of depressed patients. I expected to find signs of more hostility in the dream content of depressed patients than nondepressed patients, but they actually showed less hostility. I did observe, however, that the dreams of depressed patients contained the themes of loss, defeat, rejection, and abandonment, and the dreamer was represented as defective or diseased. At first I assumed the idea that the negative themes in the dream content expressed the need to punish one’s self (or “masochism”), but I was soon disabused of this notion. When encouraged to express hostility, my patients became more, not less, depressed. Further, in experiments, they reacted positively to success experiences and positive reinforcement when the “masochism” hypothesis predicted the opposite (summarized in Beck [1] ).

Some revealing observations helped to provide the basis for the subsequent cognitive model of depression. I noted that the dream content contained the same themes as the patients’ conscious cognitions—their negative self-evaluations, expectancies, and memories—but in an exaggerated, more dramatic form. The depressive cognitions contained errors or distortions in the interpretations (or misinterpretations) of experience. What finally clinched the new model (for me) was our research finding that when the patients reappraised and corrected their misinterpretations, their depression started to lift and—in 10 or 12 sessions—would remit (2) .

Thus, I undertook the challenge of attempting to integrate the different psychological pieces of the puzzle of depression. The end product was a comprehensive cognitive model of depression. At the surface, readily accessible level was the negativity in the patients’ self-reports, including their dreams and their negative interpretations of their experiences. These variables seemed to account for the manifestations of depression, such as hopelessness, loss of motivation, self-criticism, and suicidal wishes. The next level appeared to be a systematic cognitive bias in information processing leading to selective attention to negative aspects of experiences, negative interpretations, and blocking of positive events and memories. These findings raised the question: “What is producing the negative bias?” On the basis of clinical observations supported by research, I concluded that when depressed, patients had highly charged dysfunctional attitudes or beliefs about themselves that hijacked the information processing and produced the negative cognitive bias, which led to the symptoms of depression (1 , 3 , 4) .

A large number of studies have demonstrated that depressed patients have dysfunctional attitudes, show a systematic negative attentional and recall bias in laboratory experiments, and report cognitive distortions (selective abstraction, overgeneralizing, personalization, and interpretational biases [4] ). Dysfunctional attitudes, measured by the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (5) , are represented by beliefs such as “If I fail at something, it means I’m a total failure.” During a full-blown episode of depression, the hypersalient dysfunctional attitudes lead into absolute negative beliefs about the self, their personal world, and the future (“I am a failure”). I suggested that these dysfunctional attitudes are embedded within cognitive structures, or schemas, in the meaning assignment system and thus have structural qualities, such as stability and density as well as thresholds and levels of activation. The degree of salience (or “energy”) of the schemas depends on the intensity of a negative experience and the threshold for activation at a given time (successive stressful experiences, for example, can lower the threshold [1] ).

When the schemas are activated by an event or series of events, they skew the information processing system, which then directs attentional resources to negative stimuli and translates a specific experience into a distorted negative interpretation. The hypersalience of these negative schemas leads not only to a global negative perception of reality but also to the other symptoms of depression, such as sadness, hopelessness, loss of motivation, and regressive behaviors such as social withdrawal and inactivity. These symptoms are also subjected to negative evaluation (“My poor functioning is a burden on my family” and “My loss of motivation shows how lazy I am”). Thus, the depressive constellation consists of a continuous feedback loop with negative interpretations and attentional biases with the subjective and behavioral symptoms reinforcing each other.

Developmental Model of Depression

Cognitive vulnerability.

What developmental event or events might lead to the formation of dysfunctional attitudes and how these events might relate to later stressful events leading to the precipitation of depression was another piece of the puzzle. In our earlier studies, we found that severely depressed patients were more likely than moderately or mildly depressed patients to have experienced parental loss in childhood (6) . We speculated that such a loss would sensitize an individual to a significant loss at a later time in adolescence or adulthood, thus precipitating depression. Brij Sethi, a member of our group, showed that the combination of a loss in childhood with an analogous loss in adulthood led to depression in a significant number of depressed patients (7) . The meaning of the early events (such as “If I lose an important person, I am helpless”) is transformed into a durable attitude, which may be activated by a similar experience at a later time. A recent prospective study observed that early life stress sensitizes individuals to later negative events through impact on cognitive vulnerability leading to depression (8) .

Is the Serotonin Theory of Depression Dead?

The complicated history of the serotonin hypothesis.

Posted August 11, 2022 | Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

- What Is Depression?

- Find a therapist to overcome depression

- Research has shown that depression is not simply caused by low monoamines such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in the brain.

- Scientific understanding of depression has grown to include genetic factors, stress responses, and other brain changes.

- While depression treatment should include psychotherapy and lifestyle changes, antidepressants may still have an important role in recovery.

Recently, Moncrieff and colleagues published a review of the evidence for the serotonin theory of depression , concluding that there was “no consistent evidence of there being an association between serotonin and depression,” which was shocking news to the general public .

Many news organizations commented on this “long-held theory” being debunked. Some critics touted the paper as evidence that psychiatric treatments are a sham . One politician even cited the paper to suggest, in a baseless and confusing argument, that somehow antidepressants were responsible for mass shootings . Here, we hope to clarify what we know about serotonin and depression.

The serotonin hypothesis is a version of the “monoamine hypothesis of depression.” Monoamines are a group of chemicals that act as neurotransmitters in the brain and include serotonin, dopamine , and norepinephrine. As early as the 1950s, psychiatrists thought these chemicals might be important for mood regulation based on the serendipitous discovery that some drugs were effective for treating depression and all of them seemed to work by increasing the levels of monoamines in the brain. There were other clues, such as certain drugs that lowered monoamine levels seemed to make some people depressed.

For a time, it seemed there was a biological explanation for depression. However, it did not take long for people to see cracks in this theory. Most antidepressants take weeks to work even though they increase brain monoamine levels only a few hours after ingestion. Furthermore, even though there was an occasional positive finding, studies looking at how levels of monoamines in the brain correlate with symptoms of depression were inconclusive (before modern neuroimaging, these studies were notoriously difficult to do).

The results suggested a much more complex process . As early as 1965, Harvard psychiatrist Joseph Schildkraut summarized the theory and supporting data. He concluded, much like Professor Moncrieff half a century later, that “it is not possible…to confirm…or to reject” the hypothesis .

So why did it persist, even if experts knew it was, if not wholly wrong, at least inadequate? Like many imperfect explanations, it survived because it had utility for modeling the role of monoamine chemicals in the brain, especially for drug development. After all, the first antidepressants all worked by increasing the level of monoamines in the brain. Although effective, they were not targeted and had many side effects.

Researchers then began concentrating on a specific monoamine, serotonin, as a target for drugs. What followed was a revolution in antidepressant treatment. Fluoxetine (Prozac) was the first SSRI, or serotonin reuptake inhibitor introduced in the US. Approved in 1987, it was an almost immediate success, and a flurry of other serotonergic drugs followed. Even today, nearly all drug treatments for depression target one or more monoamines, and serotonin is usually one of those.

Even if most mental health experts understood that the monoamine hypothesis was inadequate, it became one way to explain to patients what might be causing depression. It was not uncommon for doctors to tell patients that they had a “chemical imbalance.” This biological explanation was perceived less stigmatizing for most patients, who tended to blame themselves for something outside their control.

As Dr. Montcrieff fairly points out in a blog discussing her study, “even if leading psychiatrists were beginning to doubt the [serotonin hypothesis]…no one told the public.” Many of us thought, “what is the harm.” Even if not exactly true, the point of the explanation is well intended: that depression is a biological disease, not a moral failing or, in some other way, the patient’s fault .

Although the monoamine theory spurred drug discovery and integrated a biological element into our understanding of mood disorders, it may have also limited it. Most antidepressants for the last several decades were “me too” drugs that differed little from their predecessors. The success of the monoamine approach, along with the expense of drug development, may have made pharmaceutical companies reluctant to explore new approaches to depression. It may also have dissuaded patients and their doctors from pursuing other proven approaches to depression, such as psychotherapy , exercise, and a healthy diet .

Professor Moncrieff and her coauthors are doing a service in getting the news out. However, we caution against misrepresentations of the report as a way to conclude that medications have no role in mental health treatment.

Since the monoamine theory emerged in the 1950s, thousands of scientists have added to knowledge about depression and its treatment. The whole puzzle isn't solved yet, but we know a lot. Most modern theories take an integrative approach, meaning that many things cause depression, all working (or not working) together. The “perfect storm” of depression includes genetic vulnerabilities that put people at risk, epigenetic responses to stress , and changes in certain vulnerable parts of the brain that, yes, include the serotonin system.

Is there still a role for antidepressants? Depending on the person, antidepressants are not always needed. However, for many patients, they can be lifesaving, especially those with severe depression. Our understanding of how they work continues to evolve. For example, one mechanism thought to underly the efficacy of antidepressants is their ability to either directly or indirectly lead to an increase in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is involved in the growth, maturation, and survival of neurons . New research also suggests that some antidepressants may work better for individuals of specific age, sex , medical history, and symptoms .

As our scientific knowledge grows, so should our communication to those directly affected. We believe that the serotonin theory isn’t dead; it just has grown up a lot.

About the Authors

Robert J Boland, MD is the Chief of Staff and a Senior Vice President at The Menninger Clinic. He is also vice chair of the Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science at Baylor College of Medicine and the Brown Foundation Endowed Chair in Psychiatry at Baylor. He is also the co-host of the Menninger Clinic’s Mind Dive Podcast , which examines dilemmas faced by mental health professionals.

Kelly Truong MD is a staff psychiatrist at The Menninger Clinic and an assistant professor at Baylor College of Medicine. She specializes in addiction psychiatry, psychodynamic psychotherapy, and addiction psychopharmacology . She is a member of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry, American Psychoanalytic Association and the Houston Psychoanalytic Society.

Alemi, F., Min, H., Yousefi, M., Becker, L. K., Hane, C. A., Nori, V. S., & Wojtusiak, J. (2021). Effectiveness of common antidepressants: A post market release study. EClinicalMedicine, 41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101171

Boku, S., Nakagawa, S., Toda, H., & Hishimoto, A. (2018). Neural basis of major depressive disorder: Beyond monoamine hypothesis. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 72(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12604

Casarotto, P. C., Girych, M., Fred, S. M., Kovaleva, V., Moliner, R., Enkavi, G., Biojone, C., Cannarozzo, C., Sahu, M. P., Kaurinkoski, K., Brunello, C. A., Steinzeig, A., Winkel, F., Patil, S., Vestring, S., Serchov, T., Diniz, C. R. A. F., Laukkanen, L., Cardon, I., … Castrén, E. (2021). Antidepressant drugs act by directly binding to TRKB neurotrophin receptors. Cell, 184(5), 1299-1313.e19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.034

How to take the news that depression has not been shown to be caused by a chemical imbalance. (2022, July 24). Joanna Moncrieff. https://joannamoncrieff.com/2022/07/24/how-to-take-the-news-that-depres…

Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R. E., Stockmann, T., Amendola, S., Hengartner, M. P., & Horowitz, M. A. (2022). The serotonin theory of depression: A systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Molecular Psychiatry, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

Schildkraut, J. J. (1965). The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: a review of supporting evidence. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 122(5), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.122.5.509

Mind Matters is a collaborative blog written by Menninger staff and an occasional invited guest to increase awareness about mental health. Launched in 2019, Mind Matters is curated and edited by an expert clinical team, which is led by Robyn Dotson Martin, LPC-S. Martin serves as an Outpatient Assessment team leader and staff therapist.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih research matters.

April 23, 2024

Research in Context: Treating depression

Finding better approaches.

While effective treatments for major depression are available, there is still room for improvement. This special Research in Context feature explores the development of more effective ways to treat depression, including personalized treatment approaches and both old and new drugs.

Everyone has a bad day sometimes. People experience various types of stress in the course of everyday life. These stressors can cause sadness, anxiety, hopelessness, frustration, or guilt. You may not enjoy the activities you usually do. These feelings tend to be only temporary. Once circumstances change, and the source of stress goes away, your mood usually improves. But sometimes, these feelings don’t go away. When these feelings stick around for at least two weeks and interfere with your daily activities, it’s called major depression, or clinical depression.

In 2021, 8.3% of U.S. adults experienced major depression. That’s about 21 million people. Among adolescents, the prevalence was much greater—more than 20%. Major depression can bring decreased energy, difficulty thinking straight, sleep problems, loss of appetite, and even physical pain. People with major depression may become unable to meet their responsibilities at work or home. Depression can also lead people to use alcohol or drugs or engage in high-risk activities. In the most extreme cases, depression can drive people to self-harm or even suicide.

The good news is that effective treatments are available. But current treatments have limitations. That’s why NIH-funded researchers have been working to develop more effective ways to treat depression. These include finding ways to predict whether certain treatments will help a given patient. They're also trying to develop more effective drugs or, in some cases, find new uses for existing drugs.

Finding the right treatments

The most common treatments for depression include psychotherapy, medications, or a combination. Mild depression may be treated with psychotherapy. Moderate to severe depression often requires the addition of medication.

Several types of psychotherapy have been shown to help relieve depression symptoms. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy helps people to recognize harmful ways of thinking and teaches them how to change these. Some researchers are working to develop new therapies to enhance people’s positive emotions. But good psychotherapy can be hard to access due to the cost, scheduling difficulties, or lack of available providers. The recent growth of telehealth services for mental health has improved access in some cases.

There are many antidepressant drugs on the market. Different drugs will work best on different patients. But it can be challenging to predict which drugs will work for a given patient. And it can take anywhere from 6 to 12 weeks to know whether a drug is working. Finding an effective drug can involve a long period of trial and error, with no guarantee of results.

If depression doesn’t improve with psychotherapy or medications, brain stimulation therapies could be used. Electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT, uses electrodes to send electric current into the brain. A newer technique, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), stimulates the brain using magnetic fields. These treatments must be administered by specially trained health professionals.

“A lot of patients, they kind of muddle along, treatment after treatment, with little idea whether something’s going to work,” says psychiatric researcher Dr. Amit Etkin.

One reason it’s difficult to know which antidepressant medications will work is that there are likely different biological mechanisms that can cause depression. Two people with similar symptoms may both be diagnosed with depression, but the causes of their symptoms could be different. As NIH depression researcher Dr. Carlos Zarate explains, “we believe that there’s not one depression, but hundreds of depressions.”

Depression may be due to many factors. Genetics can put certain people at risk for depression. Stressful situations, physical health conditions, and medications may contribute. And depression can also be part of a more complicated mental disorder, such as bipolar disorder. All of these can affect which treatment would be best to use.

Etkin has been developing methods to distinguish patients with different types of depression based on measurable biological features, or biomarkers. The idea is that different types of patients would respond differently to various treatments. Etkin calls this approach “precision psychiatry.”

One such type of biomarker is electrical activity in the brain. A technique called electroencephalography, or EEG, measures electrical activity using electrodes placed on the scalp. When Etkin was at Stanford University, he led a research team that developed a machine-learning algorithm to predict treatment response based on EEG signals. The team applied the algorithm to data from a clinical trial of the antidepressant sertraline (Zoloft) involving more than 300 people.

EEG data for the participants were collected at the outset. Participants were then randomly assigned to take either sertraline or an inactive placebo for eight weeks. The team found a specific set of signals that predicted the participants’ responses to sertraline. The same neural “signature” also predicted which patients with depression responded to medication in a separate group.

Etkin’s team also examined this neural signature in a set of patients who were treated with TMS and psychotherapy. People who were predicted to respond less to sertraline had a greater response to the TMS/psychotherapy combination.

Etkin continues to develop methods for personalized depression treatment through his company, Alto Neuroscience. He notes that EEG has the advantage of being low-cost and accessible; data can even be collected in a patient’s home. That’s important for being able to get personalized treatments to the large number of people they could help. He’s also working on developing antidepressant drugs targeted to specific EEG profiles. Candidate drugs are in clinical trials now.

“It’s not like a pie-in-the-sky future thing, 20-30 years from now,” Etkin explains. “This is something that could be in people's hands within the next five years.”

New tricks for old drugs

While some researchers focus on matching patients with their optimal treatments, others aim to find treatments that can work for many different patients. It turns out that some drugs we’ve known about for decades might be very effective antidepressants, but we didn’t recognize their antidepressant properties until recently.

One such drug is ketamine. Ketamine has been used as an anesthetic for more than 50 years. Around the turn of this century, researchers started to discover its potential as an antidepressant. Zarate and others have found that, unlike traditional antidepressants that can take weeks to take effect, ketamine can improve depression in as little as one day. And a single dose can have an effect for a week or more. In 2019, the FDA approved a form of ketamine for treating depression that is resistant to other treatments.

But ketamine has drawbacks of its own. It’s a dissociative drug, meaning that it can make people feel disconnected from their body and environment. It also has the potential for addiction and misuse. For these reasons, it’s a controlled substance and can only be administered in a doctor’s office or clinic.

Another class of drugs being studied as possible antidepressants are psychedelics. These include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms. These drugs can temporarily alter a person’s mood, thoughts, and perceptions of reality. Some have historically been used for religious rituals, but they are also used recreationally.

In clinical studies, psychedelics are typically administered in combination with psychotherapy. This includes several preparatory sessions with a therapist in the weeks before getting the drug, and several sessions in the weeks following to help people process their experiences. The drugs are administered in a controlled setting.

Dr. Stephen Ross, co-director of the New York University Langone Health Center for Psychedelic Medicine, describes a typical session: “It takes place in a living room-like setting. The person is prepared, and they state their intention. They take the drug, they lie supine, they put on eye shades and preselected music, and two therapists monitor them.” Sessions last for as long as the acute effects of the drug last, which is typically several hours. This is a healthcare-intensive intervention given the time and personnel needed.

In 2016, Ross led a clinical trial examining whether psilocybin-assisted therapy could reduce depression and anxiety in people with cancer. According to Ross, as many as 40% of people with cancer have clinically significant anxiety and depression. The study showed that a single psilocybin session led to substantial reductions in anxiety and depression compared with a placebo. These reductions were evident as soon as one day after psilocybin administration. Six months later, 60-80% of participants still had reduced depression and anxiety.

Psychedelic drugs frequently trigger mystical experiences in the people who take them. “People can feel a sense…that their consciousness is part of a greater consciousness or that all energy is one,” Ross explains. “People can have an experience that for them feels more ‘real’ than regular reality. They can feel transported to a different dimension of reality.”

About three out of four participants in Ross’s study said it was among the most meaningful experiences of their lives. And the degree of mystical experience correlated with the drug’s therapeutic effect. A long-term follow-up study found that the effects of the treatment continued more than four years later.

If these results seem too good to be true, Ross is quick to point out that it was a small study, with only 29 participants, although similar studies from other groups have yielded similar results. Psychedelics haven’t yet been shown to be effective in a large, controlled clinical trial. Ross is now conducting a trial with 200 people to see if the results of his earlier study pan out in this larger group. For now, though, psychedelics remain experimental drugs—approved for testing, but not for routine medical use.

Unlike ketamine, psychedelics aren’t considered addictive. But they, too, carry risks, which certain conditions may increase. Psychedelics can cause cardiovascular complications. They can cause psychosis in people who are predisposed to it. In uncontrolled settings, they have the risk of causing anxiety, confusion, and paranoia—a so-called “bad trip”—that can lead the person taking the drug to harm themself or others. This is why psychedelic-assisted therapy takes place in such tightly controlled settings. That increases the cost and complexity of the therapy, which may prevent many people from having access to it.

Better, safer drugs

Despite the promise of ketamine or psychedelics, their drawbacks have led some researchers to look for drugs that work like them but with fewer side effects.

Depression is thought to be caused by the loss of connections between nerve cells, or neurons, in certain regions of the brain. Ketamine and psychedelics both promote the brain’s ability to repair these connections, a quality called plasticity. If we could understand how these drugs encourage plasticity, we might be able to design drugs that can do so without the side effects.

Dr. David Olson at the University of California, Davis studies how psychedelics work at the cellular and molecular levels. The drugs appear to promote plasticity by binding to a receptor in cells called the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor (5-HT2AR). But many other compounds also bind 5-HT2AR without promoting plasticity. In a recent NIH-funded study, Olson showed that 5-HT2AR can be found both inside and on the surface of the cell. Only compounds that bound to the receptor inside the cells promoted plasticity. This suggests that a drug has to be able to get into the cell to promote plasticity.

Moreover, not all drugs that bind 5-HT2AR have psychedelic effects. Olson’s team has developed a molecular sensor, called psychLight, that can identify which compounds that bind 5-HT2AR have psychedelic effects. Using psychLight, they identified compounds that are not psychedelic but still have rapid and long-lasting antidepressant effects in animal models. He’s founded a company, Delix Therapeutics, to further develop drugs that promote plasticity.

Meanwhile, Zarate and his colleagues have been investigating a compound related to ketamine called hydroxynorketamine (HNK). Ketamine is converted to HNK in the body, and this process appears to be required for ketamine’s antidepressant effects. Administering HNK directly produced antidepressant-like effects in mice. At the same time, it did not cause the dissociative side effects and addiction caused by ketamine. Zarate’s team has already completed phase I trials of HNK in people showing that it’s safe. Phase II trials to find out whether it’s effective are scheduled to begin soon.

“What [ketamine and psychedelics] are doing for the field is they’re helping us realize that it is possible to move toward a repair model versus a symptom mitigation model,” Olson says. Unlike existing antidepressants, which just relieve the symptoms of depression, these drugs appear to fix the underlying causes. That’s likely why they work faster and produce longer-lasting effects. This research is bringing us closer to having safer antidepressants that only need to be taken once in a while, instead of every day.

—by Brian Doctrow, Ph.D.

Related Links

- How Psychedelic Drugs May Help with Depression

- Biosensor Advances Drug Discovery

- Neural Signature Predicts Antidepressant Response

- How Ketamine Relieves Symptoms of Depression

- Protein Structure Reveals How LSD Affects the Brain

- Predicting The Usefulness of Antidepressants

- Depression Screening and Treatment in Adults

- Serotonin Transporter Structure Revealed

- Placebo Effect in Depression Treatment

- When Sadness Lingers: Understanding and Treating Depression

- Psychedelic and Dissociative Drugs

References: An electroencephalographic signature predicts antidepressant response in major depression. Wu W, Zhang Y, Jiang J, Lucas MV, Fonzo GA, Rolle CE, Cooper C, Chin-Fatt C, Krepel N, Cornelssen CA, Wright R, Toll RT, Trivedi HM, Monuszko K, Caudle TL, Sarhadi K, Jha MK, Trombello JM, Deckersbach T, Adams P, McGrath PJ, Weissman MM, Fava M, Pizzagalli DA, Arns M, Trivedi MH, Etkin A. Nat Biotechnol. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0397-3. Epub 2020 Feb 10. PMID: 32042166. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, Mennenga SE, Belser A, Kalliontzi K, Babb J, Su Z, Corby P, Schmidt BL. J Psychopharmacol . 2016 Dec;30(12):1165-1180. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675512. PMID: 27909164. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer. Agin-Liebes GI, Malone T, Yalch MM, Mennenga SE, Ponté KL, Guss J, Bossis AP, Grigsby J, Fischer S, Ross S. J Psychopharmacol . 2020 Feb;34(2):155-166. doi: 10.1177/0269881119897615. Epub 2020 Jan 9. PMID: 31916890. Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Vargas MV, Dunlap LE, Dong C, Carter SJ, Tombari RJ, Jami SA, Cameron LP, Patel SD, Hennessey JJ, Saeger HN, McCorvy JD, Gray JA, Tian L, Olson DE. Science . 2023 Feb 17;379(6633):700-706. doi: 10.1126/science.adf0435. Epub 2023 Feb 16. PMID: 36795823. Psychedelic-inspired drug discovery using an engineered biosensor. Dong C, Ly C, Dunlap LE, Vargas MV, Sun J, Hwang IW, Azinfar A, Oh WC, Wetsel WC, Olson DE, Tian L. Cell . 2021 Apr 8: S0092-8674(21)00374-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.043. Epub 2021 Apr 28. PMID: 33915107. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, Georgiou P, Fischell J, Elmer GI, Alkondon M, Yuan P, Pribut HJ, Singh NS, Dossou KS, Fang Y, Huang XP, Mayo CL, Wainer IW, Albuquerque EX, Thompson SM, Thomas CJ, Zarate CA Jr, Gould TD. Nature . 2016 May 26;533(7604):481-6. doi: 10.1038/nature17998. Epub 2016 May 4. PMID: 27144355.

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

- Warning Signs and Symptoms

- Mental Health Conditions

- Common with Mental Illness

- Mental Health By the Numbers

- Individuals with Mental Illness

- Family Members and Caregivers

- Kids, Teens and Young Adults

- Veterans & Active Duty

- Identity and Cultural Dimensions

- Frontline Professionals

- Mental Health Education

- Support Groups

- NAMI HelpLine

- Publications & Reports

- Podcasts and Webinars

- Video Resource Library

- Justice Library

- Find Your Local NAMI

- Find a NAMIWalks

- Attend the NAMI National Convention

- Fundraise Your Way

- Create a Memorial Fundraiser

- Pledge to Be StigmaFree

- Awareness Events

- Share Your Story

- Partner with Us

- Advocate for Change

- Policy Priorities

- NAMI Advocacy Actions

- Policy Platform

- Crisis Intervention

- State Fact Sheets

- Public Policy Reports

Recognizing the Lesser-Known Symptoms of Depression

February 09, 2022

By Ginger Robertson

Thanks to sensationalized media depictions of mental illness and stigma surrounding mental health conditions, people tend to have a limited view of what depression actually looks like. When you think of a “depressed person,” perhaps you envision an image from a movie or medication commercial: Someone lying alone in a dark room, crying into a box of tissues, overcome with feelings of hopelessness.

This picture is not necessarily inaccurate; it is simply incomplete. There are many more manifestations of depression — symptoms that aren’t necessarily visible or immediately obvious.

Knowing the seldom discussed symptoms of depression is a valuable skill; being able to recognize the less obvious signs may help you or a loved one identify and seek treatment for depression, if needed. Additionally, knowing and fully understanding these symptoms allows us to be more compassionate and helpful to those who are living with mental health conditions.

Here are a few lesser-known symptoms to look out for:

Studies have shown that depression can reduce cognitive functions , including working memory, long-term memory, decision making and ability to focus. Research also suggests that people with depression often have “widespread grey matter structural abnormalities” in the brain — observable structural differences that contribute to such cognitive deficits.

This often presents in what we refer to as a “brain fog,” in which people may experience an inability to focus on tasks, slower reaction times, forgetfulness and feelings of being mentally “blocked.” Naturally, this can lead to a number of professional, personal and emotional challenges; combating cognitive symptoms can be a frustrating and demoralizing experience.

If this is a symptom you have observed in yourself or someone else, remember to have patience; you and those around you are deserving of grace while navigating a health issue.

Substance Use

While substance use disorders are complex conditions, they are often linked to depression . People experiencing substance use challenges often face the consequences of misinformation and stigma; many are blamed for “poor choices” and irresponsibility.

However, this misguided discourse fails to recognize many of the facets of addiction, including the fact that many people misuse drugs and alcohol to self-medicate their depression. They may not be aware that they are depressed, may not have the resources to treat their depression or may grapple with the stigma surrounding seeking help.

We all have a role to play in dismantling stigma surrounding treatment for mental health conditions; if we can acknowledge that mental health is health, seek help ourselves and encourage others to follow suit, we may, in result, see a decline in substance use.

Weight Changes

While weight changes can be indicative of a shift in physical health, they can also be connected to mental health. Depression is known to affect appetite; some people with depression experience increased appetite and report eating more, while others experience a decrease in appetite and undereat. Accordingly, large weight fluctuations may be a symptom of unmanaged depression.

The challenge of coping with depression is often compounded by stigma surrounding weight and body size; one person may be “fat shamed” for their weight gain while another is praised for their weight loss, despite both weight changes being a result of mental illness. Overeating and undereating — and grappling with public opinion about bodies — only adds to the physical and emotional challenges of depression. A holistic approach to treating depression requires a degree of body positivity: An acceptance of all sizes with the goal of mind and body health.

Irritability

Irritability , anger and impatience often accompany depression. Perhaps you have experienced the surprise of these negative emotions that seemingly “come out of nowhere” — either when you experience them or are on the receiving end of an outburst from someone else.

Often, these outbursts are referred to as anger attacks , sudden intense spells of anger could be considered uncharacteristic and inappropriate in the moment. In turn, this can lead to feelings of shame and confusion surrounding an inability to control these intense emotions. A 2009 study found that angry reactions in depressed individuals may stem from rejection, guilt, fear and “ineffective management of the experience and expression of anger.”

While this experience can be distressing, sharing your concerns with a trusted health care professional could prevent further attacks.

Extreme Fatigue

Often, the chemical imbalances that accompany depression can strip people of their energy. Individuals with depression often have low levels of norepinephrine, serotonin and dopamine. Without appropriate levels of these chemicals, we can experience fatigue, sleep issues, low motivation, decreased interest in once-enjoyed activities and a general lack of joy.

For these reasons, many antidepressants work to increase these chemicals in the body.

From the outside, these symptoms may be judged as a personal failing. Perhaps someone appears lazy, disorganized or unclean — but in reality, they are doing their very best to cope when they are struggling to simply get out of bed. In these moments, chores may go undone, hygiene may falter and basic tasks may get overlooked.

Rather than passing judgment or demanding change, we need to remember that, often, compassion and medical intervention are the appropriate response.

Physical Pain

Other possible physical manifestations of depression are vague aches and pains. The chemicals serotonin and norepinephrine don’t simply affect mood — they also influence how we feel pain. Accordingly, the chemical imbalance linked to depression is also linked to many types of physical pain.

Additionally, research shows that there are biological factors that increase inflammation and decrease immunity during depressive episodes. Those with depression may experience headaches, body aches and stomach aches, among other ailments.

Ultimately, it’s important to remember that depression is complex. It is a mental health condition that doesn’t always look like the tired trope we see played out in the media and stigma-laden conversations.

Depression manifests in a wide variety of symptoms — both mental and physical — that most people may not be aware of. Of course, it is certainly possible to experience brain fog, misuse substances, battle fatigue and feel pain without having depression. But if you are noticing these behaviors and feelings in yourself or someone else, remain vigilant and consider seeking help. Prioritizing your health is not only wise; it is brave.

Ginger Robertson is a registered nurse and mental health blogger. She hopes her work can end the stigma surrounding mental illness and seeking mental health care.

Submit To The NAMI Blog

We’re always accepting submissions to the NAMI Blog! We feature the latest research, stories of recovery, ways to end stigma and strategies for living well with mental illness. Most importantly: We feature your voices. Check out our Submission Guidelines for more information.

Recent Posts

NAMI HelpLine is available M-F, 10 a.m. – 10 p.m. ET. Call 800-950-6264 , text “helpline” to 62640 , or chat online. In a crisis, call or text 988 (24/7).

- What is a recession?

Recessions and the business cycle

- What is a depression?

Recession vs. depression

- How recessions affect you

- Recession FAQs

What is a recession?

Paid non-client promotion: Affiliate links for the products on this page are from partners that compensate us (see our advertiser disclosure with our list of partners for more details). However, our opinions are our own. See how we rate investing products to write unbiased product reviews.

- A recession and a depression describe periods during which the economy shrinks, but they differ in severity, duration, and scale.

- A recession is a decline in economic activity spread across the economy that lasts more than a few months.

- A depression is a more extreme economic downturn, and there has only been one in US history: The Great Depression, which lasted from 1929 to 1939.

Economic downturns are a lousy time for everyone. You may be worried about losing your job and being able to pay your bills — or you may be alarmed at just how abruptly that little red line that represents your investment portfolio has dropped. It's even worse if that red line represents your 401(k) savings. As a result, it can be helpful to know the signs of a recession, as well as the different ways this term is defined.

While you've probably heard the terms "recession" and "depression" before, you may not know what they actually mean and what the difference is between the two. Chiefly, a depression is a more severe, long-lasting recession that extends beyond the confines of a single country's border and into the economies of other nations.

To help you better understand the business cycle and prepare for the twists and turns of an economic crisis, here's what you need to know about recessions, depressions, and how they're different.

What is a recession?

Defining a recession , technical definition .

The technical definition of a recession is "a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months," according to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), a nonprofit organization that officially declares U.S. recessions and expansions.

An economic recession is often defined as a decline of real (meaning inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) for two consecutive quarters — but it's not that simple. Over the course of a business cycle, you might see GDP contract for a period of time, but that doesn't necessarily mean that there's a recession.

The NBER takes a broader view. The group defines recessions as "a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months," with indicators including:

- Decline in real GDP

- Decline in real income

- Rise in unemployment

- Slowed industrial production and retail sales

- Lack of consumer spending

The NBER's view of recessions takes a more holistic outlook of the economy, meaning recessions are not necessarily defined by one single factor. But many of these factors are intertwined, meaning a significant drop in something like GDP could rattle consumer spending or unemployment.

In simpler terms

A recession can be defined as a time during which the economy shrinks, businesses make less money and the unemployment rate goes up. The business cycle is not characterized by neverending increases in GDP. As a result, there are times when this economic yardstick is decreasing, and if it declines for a long enough time, the economy has entered recession.

These periods of economic decline frequently last about a year, according to figures provided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

During these times, many economic indicators experience notable declines. Investment and production both decline, according to an IMF paper. Consumption also declines, which reduces the overall demand for goods and services created by corporations.

This, in turn, can reduce profitability and motivate companies to lay off employees in an effort to ensure their bottom line remains healthy.

It is worth noting that while recessions frequently last about a year, expansions generally last longer , as the economy is usually growing in size, according to the IMF.

More specifically, the global organization examined 21 advanced economies between 1960 and 2007, revealing that they were in recession roughly 10% of the time, at least according to this sample.

Causes of recession

Generally speaking, expansion and growth in an economy cannot last forever. A significant decline in economic activity is usually triggered by a complex, interconnected combination of factors, including:

Economic shocks

An economic shock is an unpredictable event that causes widespread economic disruption, such as a natural disaster or a terrorist attack. The most recent example of such a shock was the COVID-19 outbreak, which triggered a brief recession.

Another example of an event that served as a shock to the economy was Hurricane Katrina. One estimate was that this natural disaster caused $200 billion worth of damage, according to figures from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

High interest rates

High interest rates make it more expensive for consumers to borrow money. This means that they are less likely to spend, especially on major purchases like houses or cars. Companies will probably reduce their spending and growth plans as well because the cost of financing is too high.

Asset bubbles

During an asset bubble, for example a housing bubble , the prices of investments like tech stocks in the dot-com era or real estate before the Great Recession rise rapidly, far beyond their fundamentals. These high prices are supported only by artificially inflated demand, which is caused by overly optimistic expectations of future asset values. This artificially inflated demand eventually dissipates, and the bubble bursts. At this point, people lose money and confidence collapses. Both consumers and businesses cut down on spending and the economy goes into recession.

Loss of confidence

The sentiment of consumers has a substantial impact on the economy. Consumer spending accounts for close to 70% of U.S. GDP, so when these individuals tighten up their purse strings, it can tip the economy into recession. Even if this change in mindset is not enough to trigger a recession, a drop in consumer demand gives companies less incentive to produce goods and services, which can in turn motivate them to lay off employees in order to maintain profitability.

It is worth noting that the confidence of business executives, as well as other key decision makers in corporations, has a substantial impact on the health of the economy. If these decision makers become less confident, then they could cut budgets, laying off workers and potentially reducing expenditure on capital equipment in an effort to bolster profitability.

To understand the macroeconomic variables that constitute recessions, Giacomo Santalego , PhD, a senior lecturer of economics at Fordham University, says it's important to acknowledge the relationship between recessions and the business cycle.

A business cycle tracks the up-and-down fluctuations natural to any capitalistic economies. Because the cycle traces the wide-ranging upward and downward comovements of economic indicators, it is often a focal point for monetary and fiscal policy as governments attempt to curtail the effects of these peaks and valleys.

Business cycles are understood as having four distinct phases:

- Expansion: This phase represents a period of economic growth, also considered the "normal" phase of the business cycle. It is often characterized by an increase in employment and a swelling of consumer spending and demand, which leads to an increase in the production and cost of goods and services.

- Peak: The highest point of a business cycle that signifies when an economy has reached its crest of output. Here, there's nowhere to go but down, sending the economy into a contraction phase. This can happen for any number of reasons, either investors get too speculative and create an asset bubble or industrial production starts outpacing demand. This is commonly seen as the turning point into the contraction phase.

- Contraction: A period that is marked by a decline in economic activity often identified by a rise in unemployment as well as a bear market . Additionally, GDP growth falls under 2%. As growth contracts, the economy enters a recession.

- Trough: A peak is to an expansion what a trough is to a contraction. A trough marks the bottom of a business cycle's economic activity and marks the start of a new wave of expansion and a new business cycle. This is a turning point that's followed by a new wave of expansion.

It's important to note that business cycles do not occur at predictable intervals. Instead, they are irregular in length, and their severity is reflected by the economic variables of the time. That said, the average post-World War II business cycle lasted 65 months, according to the Congressional Research Service .

What is a depression?

An economic depression is typically understood as an extreme downturn in economic activity lasting several years, but the exact definition and specifications of a depression are less clear.

"The way people think about it is a depression is a more widespread and severe recession," says Laura Ullrich, senior regional economist with the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, says, "but there is no clear-cut moment where we can say 'we hit X unemployment rate or Y GDP growth — we're now officially in a depression.'"

The NBER notes that economists differ on the period of time that designates a depression. Some experts believe a depression lasts only when economic activity is declining, while the more common understanding is that a depression extends until economic activity has returned to close to normal levels.

A depression is a more severe recession. However, it's a little tricky to concretely, quantifiably describe the difference between a recession and a depression, mainly because there's only been one.

Because economists do not have a set definition for what constitutes a depression, the general public sometimes uses it interchangeably with the term recession. However, the difference makes itself evident when you compare the Great Recession to the Great Depression.

Generally speaking, a depression spans years, rather than months, and typically sees higher rates of unemployment and a sharper decline in GDP. And while a recession is often limited to a single country, a depression is usually severe enough to have global impacts.

How recessions affect you

Job losses .