- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Climate Change

- Policy & Economics

- Biodiversity

- Conservation

Get focused newsletters especially designed to be concise and easy to digest

- ESSENTIAL BRIEFING 3 times weekly

- TOP STORY ROUNDUP Once a week

- MONTHLY OVERVIEW Once a month

- Enter your email *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

How Does Food Waste Affect the Environment?

In a world where people are dying from hunger, one-third of all food produced is thrown away every year. Not only does food waste exacerbate food insecurity, but it also causes severe damage to our environment. When we factor in all the different variables that go into producing the food we eat, the hidden impact it has on the environment is revealed. How does food waste affect the environment? Read on to find out.

Tossing away uneaten food may appear like meagre damage to the planet when compared to other issues, but the haunting reality is that it is just as harmful.

When we throw away food, we also throw away the precious resources that went into producing this food. This includes the use of land and natural resources, the social cost to the environment, and our biodiversity. Food waste accounts for one-third of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions and generates 8% of greenhouse gases annually . With these statistics in place, there is a huge need to reduce this environmental footprint.

Preventing food waste has been highlighted in the UN Environment Programme GEO-6 report as one of three important actions that need to be taken in transforming our food system .

What Is Food Waste?

Food waste is food that is intended for human consumption that is wasted and lost, and can occur anywhere throughout the entire supply chain from farm stage to harvest to households. Although the term may be self-explanatory, two types of food waste are apparent . The first being “food loss”, which refers to the food that we lose at the early stages of its production process. The second being “food wastage”, which refers to food that is perfectly fit for human consumption, but it gets discarded for a different reason.

How Is Food Waste Produced?

The typical stages of the food production process consists of the food being grown, processed, sorted, packaged, transported, marketed, and then eventually sold. When we look at the statistics, food waste can be identified as occurring at all stages throughout its production. Therefore, every time food is wasted, all the resources used in each step of the production is also wasted, bringing the social cost up even higher.

Looking at the production process as a chain framework can help identify where the issues are. At the beginning of this chain, also known as the “upstream” stage, the food is grown, harvested, processed and sent to be sold. At later stages of the chain, also known as the “downstream” stage, food is successfully processed and sent to consumers and commerce markets but it is wasted for other reasons unrelated to whether it is fit for human consumption or not.

The later the food is wasted along the chain, the greater its environmental impact is as the further down the chain we go, the more energy and natural resources are needed in the complete production process of the food.

In 2013, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) released a report that analysed the impacts of global food wastage on the environment . They identified patterns in food waste on a global level.

They found that middle to higher income countries’ food waste occurs in the “downstream” phase of the production process, as they found that their food was wasted by consumers and commerce businesses. They also established that developing countries were more likely to contribute to food waste in the “upstream” phase of the production process, usually due to infrastructural challenges such as lack of refrigeration, improper storage facilities, technical constraints in harvesting techniques etc.

1. Waste of Natural Resources

There are a number of ways in which food waste can affect the environment. When we waste food, we waste the natural resources used for producing that food, the three main ones being energy, fuel and water.

Water is needed for all stages of the food production process, as well as in all types of food produced. Agriculture accounts for 70% of the water used throughout the world. This includes the irrigation and spraying required for crops, and the water needed for rearing cattle, poultry and fish. By wasting food, we are wasting fresh water. Given that countries have a severe water shortage , with countries being predicted to be uninhabitable in a few decades , conserving freshwater should be a global mission.

Growing plants and rearing animals drains a huge volume of fresh water . Food such as fruit and vegetables are water-laden, and require a huge amount of water to grow. Additionally, different types of plants need different amounts of water to grow. Animals also require a large amount of water for both their growth and their feed. Producing meat requires more water supply, yet meat is the food that is thrown out the most.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) established that food waste ends up wasting a quarter of our water supply in the form of uneaten food. That’s equated to USD$172billion in wasted water. They also determined that we spend over $220billion in growing, transporting and processing almost 70million tons of food that eventually ends up in landfills.

Therefore, growing food that goes to waste ends up using up to 21% of freshwater, 19% of our fertilisers, 18% of our cropland, and 21% of our landfill volume . Throwing away a kilogram of beef is equivalent to throwing away 50,000 litres of water. Pouring a glass of milk down the sink is nearly 1,000 litres of water wasted. Additionally, taking into account global food transportation, large amounts of oil, diesel and other fossil fuels are consumed as well.

You might also like: 20 Shocking Facts About Food Waste

2. Contribution to Climate Change

When food is left to rot in our landfills, it subsequently releases methane, a powerful greenhouse gas twenty-five times stronger than carbon dioxide . When methane is released, it lingers for 12 years and traps heat from the sun.

It contributes towards 20% of the global greenhouse gas emissions released. When we factor in the greenhouse gas emissions released from the use of natural resources, the contribution to climate change is astonishing. If a decent food waste treatment system were implemented, it would stop 11% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research found that a third of all human-contributed greenhouse gas emissions are from food waste . If food waste were a country, its greenhouse gas emissions would be the third largest in the world, following the US and China.

If we stopped throwing food away, we can save the equivalent of 17 metric tonnes of CO2, which can be the environmental equivalent of five cars off the roads in the UK.

3. Degradation of Land

Our irresponsible use of food products has an adverse impact on the physical land itself. There are two ways in which we waste land. The land we use for producing the food, and the land we used for dumping the food.

Agriculture uses 11.5million hectares of the global land surface . There are two types of land; “arable” land (that can grow crops), and “non-arable” land (that cannot grow crops). 900 million hectares of non-arable land is used for livestock to produce meat and dairy products. As meat is in higher demand, more arable landscapes are being converted into pastures for animals to graze. By doing so, we are gradually degrading our natural land in a way that prohibits anything natural from growing on it.

These statistics show that we are over-stressing land for food production and if we are not mindful in the future, the ability to yield will diminish overtime as we gradually degrade the land. Not only are we disrupting our beautiful, natural landscapes, but we are also harming the biodiversity present in nature, as converting arable land into pastures will cause a loss of habitat for animals and could also severely disrupt food chains in the ecosystem.

4. Harm to Biodiversity

Biodiversity simply refers to the different species and organisms that make up an environment’s ecosystem.

Agriculture in general causes harm to our biodiversity. Mono-cropping and converting our wild lands into pastures and suitable agricultural terrains is a common practice where there is an increase in demand for the production of livestock.

Deforestation and conversion of our natural lands into non-arable land destroys the natural flora and fauna present, and in some cases, to the point of their extinction.

Marine life has also been recorded decreasing in population, with the large quantities of fish being caught causing the decimation of our marine ecosystems . The average annual increase in global fish consumption is reportedly outpacing population growth, yet at the same time, places like Europe are discarding 40-60% of fish because they do not meet supermarket quality standards. As the world continues to overexploit and depleting fish stocks, we are creating a severe disruption to the marine ecosystems and food chains, as well as threatening aquatic food security.

You might also like: The Remarkable Benefits of Biodiversity

What’s Next?

As with every other current issue posed against the environment, a global effort needs to be achieved in order to tackle the problem of food waste. Farmers, individual consumers, commercial businesses, governments, NGOs and the private sector all need to play their part and work together to fight this issue.

Consumer re-education has to be broadened, investment into waste treatment infrastructure needs to be made, food collection methods in line with redistribution have to be discussed, waste diversion systems need to be created for the commercial and retail sector, and further research as to the best ways to recycle and reuse the food waste that cannot be consumed have to be carried out.

Jose Graziano da Silva, director-general of the FAO gave suggestions on ways in which we could tackle this global problem . Changes need to be brought to every stage of the food production process.

More research and effort into developing food harvesting techniques, storing processes and redistribution processes are needed to be invested in. Steps need to be taken to ensure that food waste from oversupplying should be redistributed and diverted to people who need it the most.

You might also like: Solutions for Food Waste

Consumers and suppliers lower down the production chain need to take action and education. Consumers need to be encouraged to budget their meals as well as to ensure their meal plans are suitable to their eating habits. Suppliers need to loosen their restrictions on food aesthetics and think up ways in which they can sell the products that can be consumed yet would have been rejected simply due to aesthetic appeal. In 2016, France passed a law that now ensures that supermarkets can no longer throw away their unsold food. They are required to donate it to food banks instead.

Food that is unfit for human consumption needs to be recycled. It can be used for feeding livestock in the food production process, or even used as home compost in the home of consumers.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us

About the Author

Jangira Lewis

15 Biggest Environmental Problems of 2024

International Day of Forests: 10 Deforestation Facts You Should Know About

13 Major Companies Responsible for Deforestation

Hand-picked stories weekly or monthly. We promise, no spam!

Boost this article By donating us $100, $50 or subscribe to Boosting $10/month – we can get this article and others in front of tens of thousands of specially targeted readers. This targeted Boosting – helps us to reach wider audiences – aiming to convince the unconvinced, to inform the uninformed, to enlighten the dogmatic.

The Big Picture

Food waste occurs along the entire spectrum of production, from the farm to distribution to retailers to the consumer . Reasons include losses from mold, pests, or inadequate climate control; losses from cooking; and intentional food waste. [1]

This waste is categorized differently based on where it occurs:

- Food “loss” occurs before the food reaches the consumer as a result of issues in the production, storage, processing, and distribution phases.

- Food “waste” refers to food that is fit for consumption but consciously discarded at the retail or consumption phases.

Wasted food has far-reaching effects, both nationally and globally. In the U.S., up to 40% of all food produced goes uneaten [2], and about 95% of discarded food ends up in landfills [3]. It is the largest component of municipal solid waste at 21%. [1] In 2014, more than 38 million tons of food waste was generated, with only 5% diverted from landfills and incinerators for composting. [3] Decomposing food waste produces methane, a strong greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming. Worldwide, one-third of food produced is thrown away uneaten, causing an increased burden on the environment. [4] It is estimated that reducing food waste by 15% could feed more than 25 million Americans every year. [5]

Benefits of Less Food Waste

- Cost savings on labor through more efficient handling, preparation, and storage of food that will be used.

- Cost savings when purchasing only as much food as needed, and avoiding additional costs of disposal.

- Reduced methane emissions from landfills and a lower carbon footprint.

- Better management of energy and resources, preventing pollution involved in the growing, manufacturing, transporting, and selling of food.

- Community benefits by providing donated, untouched, and safe food that would otherwise be thrown out. [6]

Proposed Solutions to Food Waste

Globally, reducing wasted food has been cited as a key initiative in achieving a sustainable food future . Sustainable Development Goal 12 addresses responsible consumption and production, which includes two indicators to measure (in order to ultimately reduce) global food loss and food waste. [7]

In the U.S, on June 4, 2013, the Department of Agriculture and Environmental Protection Agency launched the U.S. Food Waste Challenge, calling on entities across the food chain, including farms, agricultural processors, food manufacturers, grocery stores, restaurants, universities, schools, and local governments. [1] The goals are to:

- Reduce food waste by improving product development, storage, shopping/ordering, marketing, labeling, and cooking methods.

- Recover food waste by connecting potential food donors to hunger relief organizations like food banks and pantries.

- Recycle food waste to feed animals or to create compost, bioenergy, and natural fertilizers.

On September 16, 2015, both agencies also announced for the first time a national food loss and waste goal, calling for a 50% reduction by 2030 to improve overall food security and conserve natural resources.

The National Resources Defense Council issued a summary paper providing guidelines on how to reduce waste throughout the food production chain. [2] The following are some focal points:

- State and local governments can incorporate food waste prevention and education campaigns, and implement municipal composting programs. Governments can provide tax credits to farmers who donate excess produce to local food banks. Proposed bills are currently in place in California, Arizona, Oregon, and Colorado.

- Businesses such as restaurants, grocery stores, and institutional food services can evaluate the extent of their food waste and adopt best practices. Examples include supermarkets selling damaged or nearly expired produce at discounted prices, or offering “half-off” promotions instead of “buy-one-get-one-free” promotions. Restaurants can offer smaller portions and donate excess ingredients and prepared uneaten food to charities. Schools may experiment with concepts that allow children to create their own meals to prevent less discarded food, such as with salad bars or build-your-own burritos.

- Farms can evaluate food losses during processing, distribution, and storage and adopt best practices. Farmers markets can sell “ugly” produce, which are discarded, misshapen fruits and vegetables that do not meet the usual standards for appearance. Farms can sell fresh but unmarketable produce (due to appearance) to food banks at a reduced rate.

- Consumers can learn when food is no longer safe and edible, how to cook and store food properly, and how to compost. See Tackling Food Waste at Home .

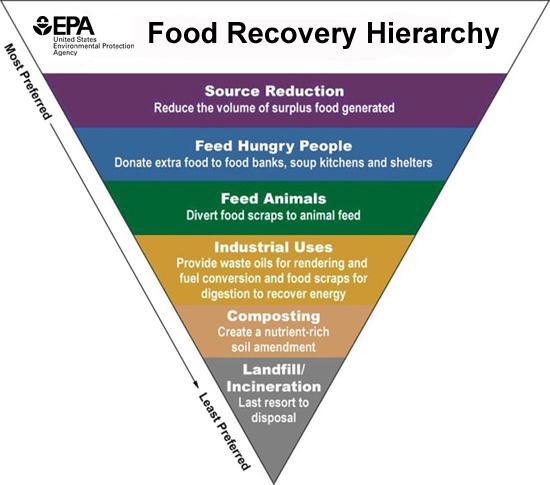

- Source reduction : Earliest prevention by reducing the overall volume of food produced

- Feed hungry people : Donating excess food to community sites

- Feed animals : Donating food scraps and waste to local farmers who can use them for animal feed

- Industrial uses : Donating used fats, oils, and grease to make biodiesel fuel

- Composting : Food waste that is composted to produce organic matter that is used to fertilize soil

- Landfill/Incineration : A last resort for unused food

Read Next: Tackling Food Waste at Home »

- Reducing meal waste in schools: A healthy solution

- Sustainability

- The Food Law and Policy Clinic of Harvard Law School

- United States Department of Agriculture. U.S Food Waste Challenge. https://www.usda.gov/oce/foodwaste/faqs.htm Accessed 3/20/2017.

- Gunders, D., Natural Resources Defense Council. Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill. Issue Paper, August 2012. IP: 12-06-B. https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/wasted-food-IP.pdf Accessed 3/20/2017.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Sustainable Management of Food. https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food Accessed 3/20/2017.

- Salemdeeb Ramy, Font Vivanco D, Al-Tabbaa A, Zu Ermgassen EK. A holistic approach to the environmental evaluation of food waste prevention. Waste Manag . 2017 Jan;59:442-450.

- D. Hall, J. Guo, M. Dore, C.C. Chow, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, “The Progressive Increase of Food Waste in America and Its environmental Impact,” PLoS ONE 4(11):e7940, 2009.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. How to Prevent Wasted Food Through Source Reduction https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/how-prevent-wasted-food-through-source-reduction Accessed 3/20/2017.

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 12.3. http://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/indicators/1231/en/ . Accessed 1/16/2018.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Food Recovery Hierarchy. https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/food-recovery-hierarchy Accessed 3/20/2017.

Terms of Use

The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice. You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products.

How Food Waste Affects World Hunger

Curdled milk, rotting apples and expired meat. We’re taking a closer look at the staggering amount of food humans waste every year and how your fridge can be part of the solution.

Read on to learn how and why we waste food, how losing all that precious food makes vulnerable people hungrier and what you – yes, you! – can do about it.

The amount of water used to produce food that ends up wasted could fill Lake Geneva three times. And of the world’s arable land, 28 percent produces food that ends up in a bin rather than in a hungry stomach.

How Much Food Do We Waste Every Year?

Globally, one trillion dollars’ worth of food goes to waste every year . That’s one-third of all food produced for human consumption ( 1.3 billion tons of it ). Before we get into how all that food waste affects hunger, here are a few key facts to keep in mind:

- Food loss is when food gets damaged as it moves through the supply chain (think rotting bananas and spilled milk). Food waste is when edible or surplus food is thrown away by retailers or consumers (like when restaurants order too much food and throw out the extras).

- If wasted food were a country, it would be the third-largest producer of carbon dioxide in the world after the United States and China.

- Rich countries waste as much food as sub-Saharan Africa produces . According to the U.N. Environment Programme, industrialized countries in North America, Europe and Asia collectively waste 222 million tons of food each year. Meanwhile, countries in sub-Saharan Africa produce 230 million tons of food each year.

- Finally, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) says that if we stopped wasting all that food, we’d save enough to feed 2 billion people . That’s more than twice the number of undernourished people across the globe.

Check out more facts about food waste.

For many Americans, food waste happens in the kitchen. For millions of people in low-income countries, food waste happens at harvest time. Poor storage leads to pest infestations or mold that ruin crops before they can be eaten.

Related articles you might be interested in:

- Food Waste, Climate Change and Hunger: A Vicious Cycle

- How to Take Action to Prevent Food Waste

- 3 Myths About Food Waste

How and Why Does Food Get Wasted?

In industrialized countries like the United States, 31 percent of food waste happens at retail and consumer levels . Think about all the food we toss out at home, what we leave on our plates at restaurants, and what ends up in grocery store trash bins. At an agricultural level, our food system produces imperfect or “ugly” foods that get trashed for no good reason.

There’s also a big difference between how food is wasted or lost in countries around the world. In developing countries, most food loss happens during or after harvest time. Farmers face problems like

- poor storage

- outdated technology

- not enough manpower

- transportation challenges getting crops to markets

Together, these problems mean that too many small-scale farmers are forced to watch their crops – and livelihoods – rot.

Learn the difference between food loss and food waste .

Why Is Food Waste Such a Big Problem?

We’re locked in a terrible cycle when it comes to food waste, climate change and hunger.

Wasted food requires energy, land, water and labor to produce, store, harvest, transport, package and sell. When we toss out food, we’re throwing away precious resources that could have been used to feed hungry people. And all that rotting food produces three billion tons of greenhouse gases like methane, directly contributing to climate change.

Read more about food waste, climate change and hunger .

More than 80% of the world’s hungry people live in places that are highly prone to extreme weather, where a changing climate is only making things worse.

People are suffering from hunger due to food loss and extreme climate. WFP is helping prevent this by providing training and tools to farmers to prevent food loss and become more resilient against climate disasters. You can help save lives from hunger by supporting the projects.

How Reducing Food Waste Can Help End World Hunger

If we stopped wasting food, we could cut global emissions by 8 percent , free up valuable land and resources, and save enough food to feed 2 billion hungry people .

The U.N. World Food Programme is training small-scale farmers on how to use improved post-harvest storage methods, combined with simple but effective air-tight storage equipment. The equipment helps to guard against insects, rodents, mold and moisture.

Here are a few ways the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) is fighting food waste and loss:

- Food Storage : Small-scale farmers can lose up to half of their harvest because they don’t have access to modern storage equipment. We provide them with silos and air-tight bags to cut their post-harvest losses from 40 to 2 percent.

- Nonperishables : Our typical food ration includes long-lasting staples like flour, dried beans, salt and cooking oil – all packaged in sturdy containers. These are all long-lasting foods so nothing spoils or gets thrown away.

- Innovation : From hydroponics to virtual farmers markets, we’re helping communities find new ways to grow, sell and store food despite challenging environments.

- Policy : The U.S. Farm Bill authorizes distributing excess American-grown crops like rice, corn, wheat and soybeans to hungry people. It’s just one of the many policies we work on to end hunger.

The U.N. World Food Programme knows the value of food and is working in Peru to transform fruits and veggies destined for the dump into nutritious meals to feed families need.

Ways to Reduce Food Waste at Home

Food waste in the United States and other high-income countries is one of the easiest problems to solve. Here are few simple ways you can help:

- Plan your meals and write a shopping list. And check your fridge to see what you’ve already got. This will help you avoid buying unnecessary food.

- Careful buying in bulk – especially foods with a limited shelf life.

- Ask if you can buy the “ugly” fruits or veggies that get left behind at grocery stores. There are even companies that will help you get direct access to this kind of produce, and it’s often cheaper.

- Check the temperature setting of your fridge. Keep the temperature at 40 degrees Fahrenheit or below to keep foods safe. The temperature of your freezer should be zero degrees Fahrenheit.

- And use your freezer! Freezing is a great way to keep food longer.

- Make a spot in your fridge for food on its last legs – and have a plan to eat it.

- If you have more food than you can eat, donate it or hand it off to a neighbor or friend.

- Remember the food you took to-go and bask in the joy of restaurant leftovers!

Cutting global food waste in half by 2030 is one of the U.N.’s top priorities. In fact, it’s one of the organization’s 17 sustainable development goals.

As the FAO says, our food systems can’t be resilient if they aren’t sustainable . As we fight food waste at home and around the world, and make our food production systems more efficient, we can free up those resources for the hungry.

Learn more about food waste and global hunger .

Help Prevent Food Loss & Hunger

Related stories.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Understanding Food Loss and Waste—Why Are We Losing and Wasting Food?

Rovshen ishangulyyev.

1 Department of Information, Turkmen Agricultural Institute, Dashoguz 746300, Turkmenistan

Sanghyo Kim

2 Division of Food and Marketing Research, Korea Rural Economic Institute, Naju 58217, Korea

Sang Hyeon Lee

3 Department of Agricultural & Resource Economics, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 24341, Korea

The Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) reported that approximately one-third of all produced foods (1.3 billion tons of edible food) for human consumption is lost and wasted every year across the entire supply chain. Significant impacts of food loss and waste (FLW) have increased interest in establishing prevention programs around the world. This paper aims to provide an overview of FLW occurrence and prevention. Economic, political, cultural, and socio-demographic drivers of FLW are described, highlighting the global variation. This approach might be particularly helpful for scientists, governors, and policy makers to identify the global variation and to focus on future implications. The main focus here was to identify the cause of the FLW occurrence throughout the food supply chain. We have created a framework for FLW occurrence at each stage of the food supply chain. Several feasible solutions are provided based on the framework.

1. Introduction

Food loss and waste (FLW) is recognized as a serious threat to food security, the economy, and the environment [ 1 ]. Approximately one-third of all food produced for human consumption (1.3 billion tons of edible food) is lost and wasted across the entire supply chain every year [ 2 ]. The monetary value of this amount of FLW is estimated at about USD $936 billion, regardless of the social and environmental costs of the wastage that are paid by society as a whole [ 3 ]. The amount of FLW is sufficient to alleviate one-eighth of the world’s population from undernourishment [ 2 ] and address the global challenge to satisfy the increased food demand, which could reach about 150–170% of current demand by 2050 [ 4 ].

The amount of FLW varies between countries, being influenced by level of income, urbanization, and economic growth [ 5 ]. In less-developed countries, FLW occurs mainly in the post-harvest and processing stage [ 2 ], which accounts for approximately 44% of global FLW [ 6 ]. This is caused by poor practices, technical and technological limitations, labor and financial restrictions, and lack of proper infrastructure for transportation and storage [ 2 ]. The developed countries, including European, North American, and Oceanian countries, and the industrialized nations of Japan, South Korea, and China produce 56% of the world FLW [ 6 ]. Of this, 40% of FLW in developed countries occurs in the consumption stage [ 2 ], which is driven mostly by consumer behavior, values, and attitudes [ 7 ]. A large portion of the food waste occurs after preparation, cooking, or serving, as well as from not consuming before the expiration date as a result of over-shopping, which might be associated with poor planning and bulk purchasing [ 7 , 8 ]. The amount of Food Waste (FW) in industrialized countries, at approximately 222 million tons, is almost equal to the total net production in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) counties (230 million tons) [ 2 ].

FLW is a critical concern in terms of nutritional insecurity, as it decreases the availability of food for human consumption. FLW also has serious environmental, economic, poverty, and natural resource impacts [ 6 ]. When FW is thrown into landfills, a substantial portion of FW is converted into greenhouse gas (GHG) and methane, which has a global warming potential 25 times higher than carbon dioxide [ 9 ]. FW decomposes faster than other landfilled materials, with a higher methane yield and without any contribution to biogenic sequestration in that area [ 10 ]. According to Rutten [ 11 ], FLW represents dissipated investment in the agricultural sector and generates significant inefficiencies in the input aspects, such as land, labor, water, fertilizers, and energy. Several studies also showed that FLW reduction initiatives in developed countries could decrease food prices in developing countries [ 11 ], boost efficiency in their supply chain, and conserve resources that might be used to feed the hungry [ 12 ]. Such changes could lead to improved access to nutritious foods for vulnerable households [ 2 ].

FLW has more recently become a substantial issue, as confirmed by the fact that the number of research publications has dramatically increased since the late 2000s [ 1 ]. FLW is an interdisciplinary subject that integrates studies from diverse fields ranging from agricultural and environmental studies to logistics and business [ 13 ]. Many studies have examined the main drivers of FLW at stages of the food supply chain (FSC) or as a whole, and systematic reviews of these studies have also been conducted. For example, Lipinski et al. [ 6 ] examined the global efforts and policy implications of reducing FLW. Abiad and Meho [ 1 ] conducted a systematic review of FLW research in the Arab world. They found that, in the Arab world, there is insufficient concern, initiatives, and research related with FLW or its reduction. Schneider [ 14 ] reviewed literature on FLW prevention at the global level. Their main finding was the limitations of research, such as lack of a consistent definition for FLW, absence of information for food loss (FL) in the transportation stage, and undeveloped methodologies of studies of FLW prevention. Another review was conducted by Thyberg and Tonjes [ 15 ] about the drivers of FLW and their implications for sustainable policy development.

The purpose of this paper was to provide a broad picture of FLW generation and prevention. Our goals are: (1) to investigate the importance and status of FLW by reviewing previous studies, which will help in understanding the negative effects of FLW and why prevention activities are necessary; (2) to investigate FLW reduction policy trends, which will answer questions such as “What kinds of programs have been implemented for the reduction and prevention of FLW?”; and (3) to investigate reasons for the occurrence of FLW along the FSC.

We searched for previous studies that addressed the FLW issue. The structure of the systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) which are suggested by Moher et al. [ 16 ]. To understand the policy trends, government and international organization websites (United Nations (UN), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), European Union (EU), etc.) were reviewed. For the investigation of the FLW studies along the FSC, the databases that were used during the search process were Scopus, Science Direct, Jstor, and Google Scholar. Keyword searches included “food loss and waste”, “food loss”, “food waste”, and “food supply chain”. The Google search engine was used to find relevant documents from institutions. Some other documents were obtained by examining reference lists and citations of key articles. Articles covering the period 2001–2018 were reviewed. The number of articles initially obtained through the database search was 82,730. Based on title and abstract screening, we excluded articles that were not relevant to FLW generation and prevention. Among 264 articles left after title and abstract screening, we excluded an additional 145 articles that only covered the technical aspect of FLW generation. Therefore, 119 articles were included in this systematic review.

2. Definitions and Situations of FLW

To date, no commonly agreed-upon definition of FLW exists [ 17 ], thus it has been difficult to measure FLW, to conduct associated research, and to determine the exact policy objectives. Various terms, such as food waste, food loss, post-harvest loss, spoilage, food and drink waste, bio-waste, and kitchen waste, are used interchangeably (see Table 1 ) [ 14 ]. These terms can be used to express totally different concepts [ 18 ]. One of the main problems occurs when such terms are translated into another language, especially from the author’s native language to English for international publication [ 14 ]. However, several institutions have announced and used their own definitions in their studies as follows.

Definitions of Food Loss and Waste.

FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization; FUSIONS EU: Food Use for Social Innovation by Optimising Waste Prevention Strategies EU; EU: European Union; FSC: food supply chain; FW: Food Waste; FL: food loss.

The FAO defined FL as decrease in weight (dry matter) or quality (nutritional value) of food that was originally produced for human consumption. Most of those losses are resulted from inefficiencies created along the FSC, such as poor logistics and infrastructure, scarcity of technology, knowledge, skills, and management capacity of supply chain participants, and lack of market access.

FW was defined by the FAO as food appropriate for human consumption being discarded, whether after it is left to spoil or kept beyond its expiry date. This is often due to the foods that have been spoiled, but there can be some other reasons, such as oversupply, depending on the market conditions, or individual consumer eating and shopping habits [ 19 ].

The Food Use for Social Innovation by Optimising Waste Prevention Strategies EU (FUSIONS EU) project has defined FW as “Any food and its inedible parts, removed from the FSC to be disposed (including composted, crops ploughed in or not harvested, anaerobic digestion, bio-energy production, co-generation, incineration, disposal to sewer, landfill, or discarded to sea) or recovered” [ 20 ].

High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) defined FL as, “A decrease, at all stages of the FSC prior to the consumer level, in mass of food that was originally intended for human consumption, regardless of the cause”, and they defined FW as “food appropriate for human consumption being discarded or left to spoil at consumer level—regardless of the cause” [ 21 ].

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) defined FLW as, “FW is a subcomponent of FL and occurs when an edible food goes unconsumed. The food which is still edible at the time of discard is considered as food waste” [ 22 ].

The above listed definitions are all similar in expressing the decrease in the quantity or quality of food aimed for human consumption. However, they have differences in considering the external causes and defining the relationship between FW and FL ( Table 1 ). According to the FAO, FL occurs during the first three stages of the FSC, and FW means the wastage that occurs at the final stage of the FSC. According to this definition, FW is related to retailer and consumer behavior. For FUSIONS EU, all losses and waste refer to FW; there is no FL terminology. HLPE determines FL as a decrease during the first four stages of the FSC and FW refers to a decrease only in the final stage of the FSC. This definition, FW, is related only to consumer behavior. USDA interprets FW as a subset of FL, and FL is a decrease in food throughout the FSC.

The definitions used in this study ( Figure 1 ) are similar to those of the FAO as follows. FL is reduction in edible food weight throughout the first three stages of the FSC. The drivers for loss considered in this study include infrastructure limitations, environmental factors, and quality or safety standards. FW is food that is produced or processed originally for human consumption but is not consumed by a person. FW includes foods that were edible when thrown and spoiled before disposal. Basically, FW represents discard that occurs in distribution, marketing, and consumption stages. However, in this study, external causes were not considered so that we could focus on FW or FL generation in the FSC.

Framework of Food Loss and Waste (FLW) definitions.

In defining FLW, as well as suggesting ways to reduce FLW, avoidable FLW should be distinguished from unavoidable FLW. Unavoidable FLW is reprensented by the types of foods that cannot be in general eaten by human beings, including meat bones and the skin of watermelons. On the other hand, avoidable FLW occurs for the types of foods that could have been used or eaten at some point of the FSC but neither used nor eaten. It is clear that the policy efforts to prevent and reduce FLW, as well as future studies, should focus on avoidable FLW. For example, food policies that prevent foods that can be eaten today but can not be eaten tomorrow being lost and wasted through ways such as temporal or spatial movement of the foods or dietary education could be more effective in reducing FLW. Even though it is not impossible to research and develop a technology or machine transforming the skins of watermelon, which has been known to be generally inedible, into a food that is edible, focusing on relatively unavoidable FLW could be a more ineffective way to reduce FLW.

2.1. FLW Quantifications

Quantifying the level of FLW is important for the development of well-planned and effective policies and programs, which can be used to distinguish the changes in residual flows after FLW prevention and recovery policies are implemented [ 23 ]. Understanding the impact of FLW can provide people with motivation to change their attitudes and behaviors. However, the absence of an exact quantification method leads to a data problem [ 24 ]. Various methods have been used for quantifying FLW ( Table 2 ), all of which have their own weaknesses. For example, some approaches only count the amount of food that is wasted in the municipal solid waste (MSW), such as waste from irrelevant sectors [ 15 ] ( Table 2 ). Other methods focus on the overall amount of FLW generated from particular sectors, such as households and restaurants, or aim to link wasted quantity with behavioral action. However, measuring the FLW based on this method is challenging—consumers mostly underestimate their waste when they are surveyed. For example, in Spain, according to a survey, FW was estimated at 4% of food, while the actual amount was 18% [ 13 ]. Some FW studies focused on excluded wastes, which disappear through the system of waste management, such as food-fed animals, compost in home, and waste placed down the drain [ 15 ]. A study that examined an Australian case estimated that 20% of Australian FLW flow is due to informal food disposal [ 25 ].

Summary of similarities and differences of definitions.

HLPE: High Level Panel of Experts; USDA: United States Department of Agriculture.

Table 3 expresses the global and country-specific estimated FLW quantities and shows the diversity in the scale, scope, and quantification of these methods. Table 2 shows the differences in estimated FLW quantities by area. For instance, estimated annual FLW quantity per capita is 637 kg in Australia and 177 kg in South Africa. It is difficult to compare FLW quantities between studies or between countries because studies have applied different criteria for FLW quantification. Therefore, a consistent quantification method is required. Recent studies, such as those by Hanson et al. [ 26 ], Östergren et al. [ 20 ], and Thyberg et al. [ 23 ] were conducted to standardize and improve quantification methods; however, estimates are heterogeneous by methodology and definition.

Estimated quantities of FLW by area.

2.2. Costs and Effects of FLW

All the actors in the FSC are economically affected by FLW. Since economic factors have been reported as the most effective motivation for FLW, the behavior of the actors can be changed if they realize the effect of FLW prevention [ 38 ]. Table 4 summarizes the economic costs of FLW. In Germany, the economic loss was calculated to be about USD $331 per capita, accounting for about 12% of expenditure on non-alcoholic beverages and food per consumer [ 46 ]. Buzby and Hyman [ 12 ] found that in 2008, the per capita amount of FW was 124 kg, which is monetarized to USD $390 at the retail and consumption stages in US. Average U.S. families spend USD $1410 each year for foods that are never consumed [ 47 ]. These estimations and figures show that reduction of FLW is important because FLW is associated with the possibility of inefficiently using scarce resources and preventing financial losses.

Summary the economic cost of FLW.

Notes: All values converted to USD.

There is increasing awareness that important environmental burdens are related to FSC. Food production affects the environment by harming plants, animals, and ecosystems as a whole [ 18 ]. Imported and non-seasonal foods increase transportation and energy use. Processing of food requires more material input and energy. Additionally, the environment is more affected when demand increases for resource intensive foods (e.g., meat). FLW puts water, soil, and air at risk because food production and distribution requires large amounts of water, land, and energy [ 48 ]. The largest usage of water and input resources is food production [ 49 ]. The food production and supply system directly influences land quality, including soil erosion, desertification, deforestation, and nutrient depletion [ 50 ]. The waste of resources caused by global FLW has been estimated to account for 24% of the total usage of freshwater resources and 23% of the global fertilizer use [ 27 ]. The reduction in FLW means that it can save resources used for production, processing and transportation, which provides benefits to the environment.

3. FLW in the Supply Chain

FLW occurs as a natural result of various faults throughout the FSC [ 54 ]. Throughout the FSC, millions of tons of foods are produced, processed, and transported to feed the world’s population. However, 815 million people, mostly living in developing countries, are undernourished and hungry (12.9% of total population) [ 55 ]. In the United States alone, 15.8 million households were considered as food insecure [ 56 ]. Reducing FLW by only 15% would feed all insecure U.S. households. If FLW is reduced by 50% of FLW, an additional one billion people could be fed [ 57 ]. Given the increasing demand for food, there is a serious concern related to adequate and sustainable global food supply. If the same level of FLW continues, then the soil, oceans, forests, bio-diversity, and fresh water might be in serious danger [ 55 ].

Efforts to reduce FLW have to start by first distinguishing where it occurs. The FAO [ 19 ] provides information about the moments when food products in the supply chain are converted to FLW: (1) crops are ripe in the plantation, field, or orchard; (2) animals are on the farm (field, pen, sty, shed, and coop) ready for slaughter; (3) milk that is drawn from the udder; (4) aquaculture fish are growing in the pond; and (5) when wild fish are caught. The supply chain ends at the point when food products are consumed, discarded, or removed for human consumption from the chain. Consequently, food that was initially produced for human consumption but removed from the chain is considered FLW, even though it could be later used as bioenergy or animal feed [ 19 ].

The UN FAO and World Resources Institute (WRI) on global FLW highlight the significant differences in per capita FLW between economies [ 2 ]. About 56% of the total FLW occurs in developed countries, while the other 44% occurs in developing countries ( Table 5 ). However, the generated FLW varies in each stage ( Figure 2 ). These differences are observable between developed and developing countries. Developing countries have relatively high FL, while developed countries have a higher portion of FW.

Portion of FLW in the stages of the food supply chain (FSC). Source: Lipinski et al. [ 6 ].

Food Loss and Waste according to economy. Source: Lipinski et al. [ 6 ].

In developing regions, 29% of FLW occurs during the first two stages (production, and handling and storage) [ 2 ]. However, in developed countries, FL occurs less in the production stage compared to developing regions, but FL in developed countries occurs due to the excessive loss of the embedded resources [ 58 ]. In both regions, the most resource-intensive stage is the production stage. That is why food sustainability models (Environmental Protection Agency’s Food Recovery Hierarchy) emphasize the reduction of food surplus generated during the production stage. FW at the consumption stage in developing regions is significantly lower due to limited household income and poverty. Households in developing countries purchase less and smaller amount of food, and they have a tendency to buy food on a daily basis [ 2 ]. For example, in the EU and North America (NA), consumer FLW per capita ranges between 95 and 115 kg, while total FLW per capita in developing regions (Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and South East Asia (SEA)) is between 6 and 11 kg [ 55 ].

Occurrence of FW during the last stage of FSC is generally considered more harmful. As food travels along the FSC, resources are required to move the food from stage to stage. Thus, FLW that occurs at the last stage has required more resources. In developed countries, a large portion of FLW occurs at the last stage of the FSC. Targeting FW interventions at the consumption stage may result in a significant reduction in wastage and decrease the environmental impacts of FW [ 2 ].

3.1. FL During Production Stage

FL occurs when appropriate access to harvesting equipment, pesticides and fertilizers, farmer training courses, extended service, and research, financial, and meteorological institutions is difficult. Harvesting method (mechanical or manual) and timing are two important factors causing the FL in this stage. Because of low mechanization rate and insufficient labor force, food loss occurs due to delayed harvesting in the harvest season [ 59 , 60 ]. Sometimes harvesting time is delayed due to economic reasons. Producers prefer to leave the crop without harvesting if, at that moment, demand is low and returns to harvest cannot cover the cost of harvest and transportation [ 3 ]. In addition, poor harvesting methods and equipment with poor performance can lead to food loss [ 61 , 62 ]. Farmers often overproduce in order to protect against pest attacks, weather, and market uncertainties, and to guarantee the contractual obligation with the buyers. Oversupply decreases the market price and leads to more crops left unharvested [ 2 , 43 , 63 , 64 ]. Some products are not harvested or thrown out directly after harvest because they failed to meet quality standards, such as shape, size, color, and weight, required by processors or target markets [ 34 , 64 , 65 , 66 ]. Poor nutrient and water management contributes to lower quality of production, resulting in high FL during the grading process.

In the case of vegetables, fruits, and meats, product quality at the production stage heavily depends on agronomic practices, diseases, and education [ 20 ]. Poor practices can result in high FL. Pre-harvest pest infestation is one of the major factors causing post-harvest FL for fruits and vegetables, as some of the infestations begin to appear after harvesting [ 67 ]. In meat production, FL occurs due to death during breeding, which can be due to poor practice and lack of knowledge [ 2 ]. One of the main causes of FL during the production stage is choosing the right variety that is adapted to a given location and meeting market requirements [ 68 ]. Choosing the wrong variety leads to the production of inferior quality food, which results in larger losses in farmer income. For cereals, such as wheat, maize, sorghum, and rice, selecting the wrong varieties that are prone to logging in locations where wind is prevalent leads to high losses.

Consequently, the main drivers of FL in this stage are listed in Table 6 .

Possible causes of FLW at the production stage of FSC.

3.2. FL during Handling and Storage Stage

In this stage, occurrence of FL varies depending on the type of food product [ 2 , 69 , 70 ]. Products such as vegetables experience losses due to degradation and spillage in loading and unloading, transportation (from farm to distribution), and storage. For meat products, losses include death during handling to slaughter and condemnation in the slaughterhouse. For fish products, losses refer to degradation and spillage during icing, storage, package, and transportation after landing. Milk is also similar to fish, as losses for milk include degradation and spillage during transportation from farm to distribution. FL during handling and storage stages accounts for the largest portion of the total FLW. Due to the poor transportation infrastructure and improper transportation vehicles, fresh products such as fish, meat, vegetables, and fruits can easily perish in hot weather due to absence of infrastructure for transportation and improper vehicles [ 65 ]. The FL level in transportation can be relatively low with good road infrastructure, facilities in the fields, and proper loading and unloading facilities [ 59 ]. Therefore, better transportation infrastructure and loading facilities could potentially reduce FL. Timely transportation from warehouse to retail through accurate forecasting of demand is also important for reducing food loss [ 71 , 72 ]. If accurate timing is not achieved, the food must be stored on the retail shelf for too long, which leads to food waste by reducing the quality of the food or expiration of the consumption period.

Proper warehouses (storage facilities) help manage the time constraint, extending marketing and consumption time so that FL can be reduced [ 65 , 73 ]. With the absence of storage infrastructure and inaccessibility to or non-existence of cold storage facilities, highly perishable products are often discarded generating FL. Good storage conditions, which can properly control light, moisture, oxygen level, sanitation, and temperature, help reduce FL of perishable products [ 74 ]. Foods such as grain can be better stored if drying facilities are optimized [ 75 , 76 ]. If the storage facility is not suitable, food loss due to pests, disease, and spillage also occurs [ 66 , 77 ].

The main drivers of FL in the handling and storage stage are listed in Table 7 .

Possible causes of FLW at the Handling and Storage stage of the FSC.

3.3. Processing and Packaging Stage FL

There are some unavoidable losses that occur in the processing stage for some products, such as meat, milk, and fish [ 2 , 43 , 66 ]. For example, losses of meat occur during additional industrial processing (e.g., sausage production) and trimming spillage during slaughtering. For milk, spillage occurs during pasteurization (industrial milk treatment) and losses occur during milk processing for yogurt and cheese. For fish, losses during industrial processing and packaging (canning and smoking) can occur. However, occurrence of FL at the processing and packaging stages is mostly due to technical inefficiencies and malfunctions [ 21 , 43 ]. Errors in processing lead to defects in the final product, such as incorrect shape, size, weight, or packaging damage. Sometimes these kinds of defects do not seriously affect the safety and quality of the final product, although they will be discarded in accordance with established safety and quality standards [ 21 , 66 ].

Insufficient processing line capacity and inefficient processing methods can also lead to FL [ 21 , 43 , 78 ]. Failure to accurately predict demand can result in food loss if too much raw material is purchased and stored for food processing [ 79 ]. Frequent changes in the food produced in processing facilities are also the cause of food loss [ 43 ]. The contamination in a processing line that occurs due to improperly cleaned processing units not sanitized from previous processes is also one of main causes of FL occurrence, especially for animal products [ 43 , 66 ]. Proper process management to guarantee food quality and safety based on published standards can be a key factor in reducing FL [ 77 ]. Proper packaging also can play a significant role in extending the shelf life of food products and reducing FL [ 2 , 78 ]. At this stage, considerable FL is produced due to legislation restrictions on the appearance of fruits and vegetables [ 80 ]. FL also occurs during cleaning, inspection, processing, and packaging processes, and in conforming to food safety standards [ 74 , 81 ]. Overproduction of processed food, especially refrigerated foods with short shelf life, is one of the major causes of food waste [ 63 , 82 ].

The main drivers of FL in the processing and packaging stage are listed below in Table 8 .

Possible causes of FLW at the processing and packaging stage of FSC.

3.4. FW on Distribution and Marketing Stage

This stage includes the activity of transporting food from one place (farm, factory, storage, etc.) to another. Additionally, this stage includes the set of market activities (retail or wholesale) that allow consumers access to food.

To avoid FW in distribution activities, it is important to use appropriate conveyance conditions, e.g., temperature-controlled aircrafts and ships, which move vegetables and fruits between continents. For products such as milk, trucks collect the milk, connecting farms with pasteurization plants. To avoid contamination, the truck’s carriage must be kept clean and hygienic [ 74 ].

In most developing countries, food loss is caused by transport through poorly maintained roads. For example, fruit is often wasted because of bruises and bumps due to road conditions. In rainy seasons, transportation of food using rural roads becomes demanding due to road blockages or landslides. However, during dry seasons, the likelihood of contamination increases due to dust [ 83 ]. When moving duration and distance are longer than the ripening process, expiry dates are shortened. Therefore, the likelihood of commercialization declines and buyers refuse some part of the delivered food. Also, in traditional markets, sellers sprinkle unclean water on vegetables and fruits to decrease the shriveling and wilting in hot weather under sunlight. This kind of technique, which aims to slow deterioration, could produce unsafe foods that are avoided by buyers and end up as landfill [ 65 ]. These phenomena happen in developing countries due to transport congestion, vehicle failures, bad weather, and lack of capital and facilities [ 74 ].

In developed countries, there is a commonly self-imposed rule between food businesses—called the “rule of one-third”. According to this rule, food must be delivered to suppliers at one-third of their shelf time with the main intention of providing consumers a broad choice of fresh products that are relatively far from their expiration date. However, if products are not delivered according to this rule, then many retailers refuse to buy them and return the orders, which results in the FW of safe foods [ 58 ]. Consequently, edible products are sorted out due to quality, expired before being purchased, or being damaged or spilled in the market [ 6 , 43 , 64 , 66 ]. In addition to the distribution stage, a similar situation occurs in the marketing stage. The owners of stores seek to manage various products displayed in large quantities and are regularly refilled to supply the shelves for consumer satisfaction. When retailers mix the same product with different expiry dates, sooner expiry dates are refused by the consumers because everyone prefers fresher products [ 65 ]. Retailers sell fresh-cut vegetables and fruits and ready-made convenience foods to meet consumer demand. However, these kinds of foods mostly have a one-day shelf life. So, if all the displayed foods cannot be sold, then these foods must be discarded. Increases in fresh-cut products have been motivated by the consumer demand for fresh, convenient, and healthy foods that are nutritious and safe. However, perishing of the fresh-cut products is accelerated by poor temperature and packaging management [ 66 , 84 ]. Even in developed countries with good packaging and temperature management conditions, the amount of fresh cut products that are landfilled remains high [ 21 ].

Commercial pressure in the marketing stage is also a major cause of food waste [ 66 , 85 ]. Promotional activities, such as “buy one and get one free”, which are conditional on increasing the purchase quantity, lead consumers to waste food by inducing them to purchase more food than necessary.

Given these research conclusions, the main drivers of FL in the distribution and marketing stage are listed in Table 9 .

Possible causes of FLW at the distribution and marketing stage of FSC.

3.5. Consumption Stage FW

FW during this stage means the leftovers in a house, business place, or restaurant (cafeteria). Foods that are purchased and cooked but not consumed contribute to FW during this stage. Food waste in the consumption stage can be effectively reduced by future efforts [ 24 ]. According to Parfitt et al. [ 24 ], four main criteria affect FW during this stage: household size and composition, income, culture, and demographic factors. In addition to these four main factors, it has been widely confirmed in the literature that the individual attitudinal factor could also influence the FLW reduction.

3.5.1. Household Size and Composition

Household (family) size and composition play a significant role in FW generation. Households with fewer residents may discard more because the foods prepared or purchased are commonly larger than the requirements of a smaller-sized household [ 21 ]. Families with children are more likely to waste food than those without [ 39 , 86 ]. For instance, larger families generate less FW per capita than smaller families, particularly single-person households [ 86 ]. Koivupuro et al. [ 34 ] found people that live alone generates more FW per capita than other households. Jörissen et al. [ 87 ] also reported that single-person households generate the most FW per capita.

In the house, FW can be generated more when enough or inadequate food is prepared [ 34 ]. In some cases, people lack food preparation skills or the ability to reuse leftovers. Approximately 40% of household FW in the United Kingdom is due to the preparation of too much food [ 51 ]. Over-provisioning could be both unintentional and intentional, as it is hard to decide how much to cook [ 88 ].

3.5.2. Household Income

As household income increases, diets transition toward the consumption of more fruit and vegetables, diary, fish, meat, and poultry [ 24 ]. Worldwide, consumption of convenience, energy, and protein-rich foods increases along with the westernization of the Asian diet [ 89 ]. Food diversification can lead to more FW, and a more repetitive diet can lead to less FW because it is possible to reuse ingredients from one meal for another meal, using staple ingredients that are included in almost every meal [ 15 , 90 ].

Households with higher incomes tend to waste more, as food is relatively cheaper than other goods. Especially in developed countries, the proportion of expenditure on food consumption is low in the total expenditure of households, and is less sensitive to food waste during food consumption [ 88 ]. As evidence, in 2012, U.S. citizens spent 6.1% of their income on food; however, in Pakistan and Cameroon, this ratio was 47.7% and 45.9%, respectively [ 15 ].

3.5.3. Household Demographics

Behaviors and attitudes examined in a study showed some correlation between FW and socio-demographic characteristics [ 88 ]. Examining the demographic aspects (e.g., aging population) may lead to better understanding of its relationship with FW. Although there is no clear conclusion about which socio-demographic aspects affect FW more, previous studies that examined the relationship between age and FW have shown that younger people waste more food than older people [ 39 , 51 ].

Hamilton et al. [ 91 ] reported that, in Australia, as age increases, FW falls sharply; young people (18–24 years old) wasted more than $30 of fresh fruit within two weeks compared with older people (70 years old and older). In the United Kingdom, people aged 65 years and over produce considerably less FW than rest of the population [ 51 ].

In addition, there are studies that the degree of awareness of FW is related to the actual reduction of wastage [ 86 , 88 , 92 ].

3.5.4. Household Culture

Culture has a crucial role in dietary habits, as well as in generating FW [ 93 ]. Each culture has its own habits as to which parts of food are considered edible and which parts are thrown away, therefore, FW depends on cultural attitudes and habits [ 94 ]. For example, the United States and Australia have weak food traditions, which imply that there are fewer fundamental rituals and rules about what, when, and how to eat, and there are weak links between production, preparation, and consumption of foods [ 95 ]. Therefore, Bloom [ 96 ] argued that the United States has an unhealthy diet, and the U.S. food culture places little value on food, leading to FW. However, French food culture is different. In France, food attitudes emphasize quality rather than quantity [ 93 ], so FW is relatively lower compared to the United States. Countries that have a deep food culture tend to be more resistant to diversity, due to the strong connection between production, preparation, and consumption. Cultures that have strong connections and place higher value on food produce less FW.

Events, such as wedding, parties, and religious ceremonies, also produce FW. For instance, during Ramadan (fasting ritual) in some Arabic countries, a significant portion of prepared meals is wasted. In Saudi Arabia, 30–50% of prepared foods are wasted. Similarly, 50% in United Arab Emirates and 25% in Qatar are wasted during this time [ 1 ]. The increase in FW during Ramadan is attributed to the arrangement of extravagant meals for which the food prepared exceeds the needs of the guests and families, with leftovers becoming FW [ 1 ].

3.5.5. Individual Attitude

The individual or household variation in the FLW can be determined by the individual’s knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes about FLW. Even if FLW is a major environmental issue that has attracted worldwide attention, it may not be a critical issue for a particular country or for a particular individual in a particular country. That is, an individual’s knowledge or attitude about the severity of the FLW problem can have a significant impact on the actual reduction, as well as the reduction intent of the FLW. The impact of attitudes and behaviors of individuals on FLW prevention could be limited, as attitudes are not entirely consistent with the actual behaviors (i.e., the attitude–behavior gap, [ 97 ]). However, there are many studies that have found evidence on the positive relationship between attitude and actual behavior on FLW reduction.

The intent to reduce or actual reduction of FLW is influenced by individual concerns about FLW. In other words, consumers who understand and concern about the severity of the FLW problem have lower FLW and the FLW reduction intention is also known to be larger [ 98 , 99 , 100 ].

Stefan et al. [ 101 ] argues that FW is influenced by consumer planning and shopping routines, and that such consumer planning and shopping routines are determined by consumer moral attitudes and perceptions. Abeliotis et al. [ 102 ] also showed that Greek consumers are very careful in the fresh food shopping stage because they show a positive attitude toward the FW prevention. This can also be explained by Marangon et al. [ 103 ]. Marangon et al. [ 103 ] confirmed that whether consumers think FW is an important issue or not has a statistically significant effect on the actual FW amount.

In light of these findings, national campaigns and education that help appropriately shape the individual’s attitude toward reducing FLW are of great importance. In addition to global campaigns, such as UN and FAO’s “Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction”, more country-level campaigns need to be pursued.

3.5.6. Cooking Process and Method, Storage in Household, Over-Cooking

If households do not properly determine the point of purchase and purchase amount of raw materials depending on when and how much cooking is done in the household, food waste may occur [ 66 ]. In addition, the amount of food waste generated varies depending on which cooking method is selected [ 104 ]. If households do not store raw materials properly before cooking, this also causes food waste [ 66 ]. Excessive cooking in the household causes food waste, but the type of service provided in the food service industry, which provides an excessive amount of food such as a buffet, also causes food waste [ 43 , 64 , 105 ].

Given these research conclusions, the main drivers of FL in the Consumption stage are listed in Table 10 .

Possible causes of FLW at the consumption stage of FSC.

4. Solutions and Conclusions

Creating effective solutions to reduce FLW lies in the recognition of linkages among the stages of the FSC. For instance, the performance of actors and costs of activities in upstream sections of the chain can determine the quality of the product further down the FSC [ 106 ]. In this integrated FSC approach, special attention needs to be directed to the effect of the technical interventions on the environment and the social context. However, the cost of the proposed solutions should be less than the cost of the foods that are lost or wasted [ 107 ]. Improving storage facilities on farms to reduce FLW should be integrated with a proper strategy to enhance market access. Mostly for developing countries, solutions should first consider the farmer perspective (i.e., farmer education, harvest techniques, and storage and cooling facilities) and then need to improve social infrastructures [ 108 ]. In developed (industrialized) countries, solutions in the production and processing stages can only create marginal improvements when stock management at the marketing stage and consumer awareness are absent [ 109 ]. It is important to improve communication among all stakeholders in the food supply chain, including public and private stakeholders, and to raise new awareness of food [ 110 , 111 ]. Information on food waste should be shared among all actors in the supply chain [ 110 , 111 ].

Based on our investigation, we conclude that the most important factors to reduce FLW are:

- (1) Government investment in infrastructure and capacity building for agriculture;

- (2) Appropriate policy implications to facilitate market access and efficient distribution methods; and

- (3) Increasing awareness of FLW and establishing the right dietary habits and culture.

4.1. Institutional Efforts to Reduce FLW

Reducing FLW would contribute to addressing interconnected sustainability challenges, such as climate change, food security, and natural resource shortages [ 19 ]. Therefore, developing an appropriate strategy for reducing FLW is one of the important issues related to sustainable development [ 112 ]. International organizations, governments, and scholars have begun to pay more attention to FLW and its reduction. Table 11 summarizes the representative efforts.

Summarize of leading efforts.

FRC: Food Recovery Challenge; SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals; OECD: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; FCAN: Food Chain Analysis Network; APHLIS+: African Postharvest Losses Information System; APEC: Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation; PPP: public-private partnerships; WRAP: Waste and Resources Action Program; USFWC: U.S. Food Waste Challenge; USFLW: U.S. Food Loss and Waste 2030 Champions.

The UN announced the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agreed upon in September 2015, which identified FLW as a key challenge for achieving sustainable consumption. Goal 12.3 aims to “Halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses, by 2030”, and Goal 12.5 aims to “Substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse by 2030” [ 55 ].

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) created The Food Chain Analysis Network (FCAN) to focus on important issues related to the food chain and hold annual meetings, with titles such as Building a Sustainable Food Chain, Mobilizing the Food Chain for Heath, Food Waste along the Supply Chain, etc. Annual meetings began December 2010 and two meetings were devoted to the FLW issue: “Food waste along the supply chain” (June 2013) and “Reducing food loss and waste in the retail and processing sectors” (June 2016). In 2011, the FAO and Messe Dusseldorf started the “SAVE FOOD: Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction” program. They collaborate with donors, several level agencies, financial institutions, and private sector partners to enhance and implement the FLW reduction program.

The Meeting of G20 Agricultural Chief Scientists (MACS) decided to place emphasis on FLW since 2015, and created an appropriate FLW web portal to provide information about research results regarding FLW, as well as the recent FLW innovations. Furthermore, the next MACS plan is to integrate the promising set of research findings, innovative technological solutions, and representative campaigns.

The African Postharvest Losses Information System (APHIS+) is a regional program particularly focusing on SSA countries. APHLIS+ integrates a network of local experts who supply data, a shared database, and a losses calculator. Working together, these generate estimates of the weight losses of cereal grains in SSA by country and by province [ 113 ].

Food Use for Social Innovation by Optimizing Waste Prevention Strategies (FUSIONS) is a four-year program that aims to support the 50% EU reduction target in food waste and 20% in the food chain resource inputs by 2020 through delivery of its key objectives [ 114 ]. FUSIONS deliverables are divided into five work packages split between project teams [ 20 ]. The main objectives of FUSIONS are: (1) to harmonize FW monitoring, (2) to examine the feasibility of social innovative measurements for optimized food use in the FSC, and (3) to create a Common FW Policy for EU.

In 2013, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) introduced the project called “Strengthening Public-Private Partnerships to Reduce Food Losses in the Supply Chain”. Over a five-year period, this project aims to address post-harvest losses at all stages of the food supply chain in the APEC region by strengthening public-private partnerships. As part of the first step of the project, a workshop was held in 2013 in Chinese Taipei that identified key issues and challenges in post-harvest food losses, formulated a preliminary methodology on food crops, and deliberated upon strategies and action plans for APEC economies. Building upon these outcomes, expert consultations and seminars were held to strengthen public-private partnerships (PPP), to reduce food losses in the supply chain, and to tackle various topics. Examples of these seminars include Fruit and Vegetable in 2014, Fishery and Livestock in 2015, and Food Loss and Waste at the consumer level in 2016 [ 115 ].

Waste and Resources Action Program (WRAP) UK is a not-for-profit company that was established in 2000. WRAP is backed by U.K. government funding from the Department for the Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs, the Scottish Government, the Welsh Government, and the Northern Ireland Executive [ 6 ]. WRAP helps people recycle more and waste less, both at work and at home, which are practices that have economic and environmental benefits as well. In 2007, WRAP started the nationwide campaign “Love Food, Hate Waste”. Due to this campaign, the United Kingdom became fifth leading country in global FLW reduction. The campaign follows the 4E (Enable, Encourage, Engage, Exemplify) behavioral change model approach, which includes enabling people to change, engaging in the community, encouraging action, and exemplifying others’ success [ 116 ]. The model was successful, promoting a 15% reduction in household food waste and a 21% reduction in avoidable waste, which was observed from 2007 to 2012 [ 117 ]. The campaign was organized to produce this achievement by targeting consumer education and awareness using basic methods to reduce FLW [ 54 ].

There are three FLW recognition programs in the United States. These programs are operated by USDA and United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). The programs are as follows: (1) The Food Recovery Challenge (FRC) was launched in 2011. The FRC was designed for organizations searching to track their FW reduction activities. Members can join as participants if they are producing FW, or as endorsers if they are not producing their own FW but can help others reduce their FLW (i.e., organizations looking to help educate or recruit for the FRC) with requirements to provide data or report activities to the challenge [ 118 ]. EPA provides a free climate report and technical assistance to participants. More than 800 participants joined this program and they have diverted food and prevented millions of tons of food from waste since it started [ 118 ]. (2) The U.S. Food Waste Challenge (USFWC) was created in 2013. The USFWC was designed for organizations seeking to make a public pledge or disclosure of their activities to reduce FW. Participants make a one-time pledge with their name and activities listed on the USDA website. The goals of the USFWC are: (a) to disseminate information about best practices to reduce, recover, and recycle FW; (b) stimulate the development of these practices across the entire U.S. FSC; and (c) provide a snapshot of the country’s commitment to and successes in reducing, recovering, and recycling FW. More than 1000 participants have joined this program as of October 2014 [ 118 ]. (3) The U.S. Food Loss and Waste 2030 Champions (USFLW) was launched in 2016. USFLW involves businesses and organizations that have made a public commitment to reduce FLW in their own operations in the United States by 50% by the year 2030. Businesses that are not ready to make the 50% reduction commitment but are engaged in efforts to reduce FLW in their operations can be recognized for their efforts by either joining FRC or the USFWC [ 118 ].