Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 15 September 2022

Interviews in the social sciences

- Eleanor Knott ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9131-3939 1 ,

- Aliya Hamid Rao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0674-4206 1 ,

- Kate Summers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9964-0259 1 &

- Chana Teeger ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5046-8280 1

Nature Reviews Methods Primers volume 2 , Article number: 73 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

714k Accesses

54 Citations

42 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Interdisciplinary studies

In-depth interviews are a versatile form of qualitative data collection used by researchers across the social sciences. They allow individuals to explain, in their own words, how they understand and interpret the world around them. Interviews represent a deceptively familiar social encounter in which people interact by asking and answering questions. They are, however, a very particular type of conversation, guided by the researcher and used for specific ends. This dynamic introduces a range of methodological, analytical and ethical challenges, for novice researchers in particular. In this Primer, we focus on the stages and challenges of designing and conducting an interview project and analysing data from it, as well as strategies to overcome such challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

The fundamental importance of method to theory

How ‘going online’ mediates the challenges of policy elite interviews

Participatory action research

Introduction.

In-depth interviews are a qualitative research method that follow a deceptively familiar logic of human interaction: they are conversations where people talk with each other, interact and pose and answer questions 1 . An interview is a specific type of interaction in which — usually and predominantly — a researcher asks questions about someone’s life experience, opinions, dreams, fears and hopes and the interview participant answers the questions 1 .

Interviews will often be used as a standalone method or combined with other qualitative methods, such as focus groups or ethnography, or quantitative methods, such as surveys or experiments. Although interviewing is a frequently used method, it should not be viewed as an easy default for qualitative researchers 2 . Interviews are also not suited to answering all qualitative research questions, but instead have specific strengths that should guide whether or not they are deployed in a research project. Whereas ethnography might be better suited to trying to observe what people do, interviews provide a space for extended conversations that allow the researcher insights into how people think and what they believe. Quantitative surveys also give these kinds of insights, but they use pre-determined questions and scales, privileging breadth over depth and often overlooking harder-to-reach participants.

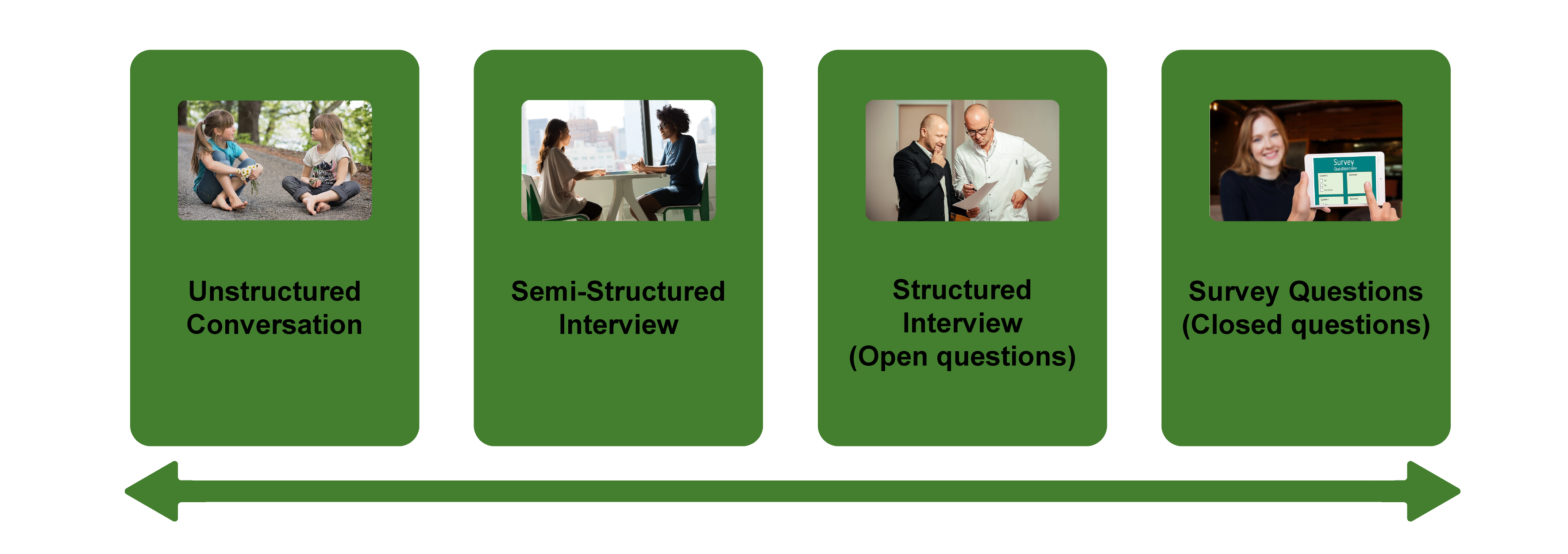

In-depth interviews can take many different shapes and forms, often with more than one participant or researcher. For example, interviews might be highly structured (using an almost survey-like interview guide), entirely unstructured (taking a narrative and free-flowing approach) or semi-structured (using a topic guide ). Researchers might combine these approaches within a single project depending on the purpose of the interview and the characteristics of the participant. Whatever form the interview takes, researchers should be mindful of the dynamics between interviewer and participant and factor these in at all stages of the project.

In this Primer, we focus on the most common type of interview: one researcher taking a semi-structured approach to interviewing one participant using a topic guide. Focusing on how to plan research using interviews, we discuss the necessary stages of data collection. We also discuss the stages and thought-process behind analysing interview material to ensure that the richness and interpretability of interview material is maintained and communicated to readers. The Primer also tracks innovations in interview methods and discusses the developments we expect over the next 5–10 years.

We wrote this Primer as researchers from sociology, social policy and political science. We note our disciplinary background because we acknowledge that there are disciplinary differences in how interviews are approached and understood as a method.

Experimentation

Here we address research design considerations and data collection issues focusing on topic guide construction and other pragmatics of the interview. We also explore issues of ethics and reflexivity that are crucial throughout the research project.

Research design

Participant selection.

Participants can be selected and recruited in various ways for in-depth interview studies. The researcher must first decide what defines the people or social groups being studied. Often, this means moving from an abstract theoretical research question to a more precise empirical one. For example, the researcher might be interested in how people talk about race in contexts of diversity. Empirical settings in which this issue could be studied could include schools, workplaces or adoption agencies. The best research designs should clearly explain why the particular setting was chosen. Often there are both intrinsic and extrinsic reasons for choosing to study a particular group of people at a specific time and place 3 . Intrinsic motivations relate to the fact that the research is focused on an important specific social phenomenon that has been understudied. Extrinsic motivations speak to the broader theoretical research questions and explain why the case at hand is a good one through which to address them empirically.

Next, the researcher needs to decide which types of people they would like to interview. This decision amounts to delineating the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study. The criteria might be based on demographic variables, like race or gender, but they may also be context-specific, for example, years of experience in an organization. These should be decided based on the research goals. Researchers should be clear about what characteristics would make an individual a candidate for inclusion in the study (and what would exclude them).

The next step is to identify and recruit the study’s sample . Usually, many more people fit the inclusion criteria than can be interviewed. In cases where lists of potential participants are available, the researcher might want to employ stratified sampling , dividing the list by characteristics of interest before sampling.

When there are no lists, researchers will often employ purposive sampling . Many researchers consider purposive sampling the most useful mode for interview-based research since the number of interviews to be conducted is too small to aim to be statistically representative 4 . Instead, the aim is not breadth, via representativeness, but depth via rich insights about a set of participants. In addition to purposive sampling, researchers often use snowball sampling . Both purposive and snowball sampling can be combined with quota sampling . All three types of sampling aim to ensure a variety of perspectives within the confines of a research project. A goal for in-depth interview studies can be to sample for range, being mindful of recruiting a diversity of participants fitting the inclusion criteria.

Study design

The total number of interviews depends on many factors, including the population studied, whether comparisons are to be made and the duration of interviews. Studies that rely on quota sampling where explicit comparisons are made between groups will require a larger number of interviews than studies focused on one group only. Studies where participants are interviewed over several hours, days or even repeatedly across years will tend to have fewer participants than those that entail a one-off engagement.

Researchers often stop interviewing when new interviews confirm findings from earlier interviews with no new or surprising insights (saturation) 4 , 5 , 6 . As a criterion for research design, saturation assumes that data collection and analysis are happening in tandem and that researchers will stop collecting new data once there is no new information emerging from the interviews. This is not always possible. Researchers rarely have time for systematic data analysis during data collection and they often need to specify their sample in funding proposals prior to data collection. As a result, researchers often draw on existing reports of saturation to estimate a sample size prior to data collection. These suggest between 12 and 20 interviews per category of participant (although researchers have reported saturation with samples that are both smaller and larger than this) 7 , 8 , 9 . The idea of saturation has been critiqued by many qualitative researchers because it assumes that meaning inheres in the data, waiting to be discovered — and confirmed — once saturation has been reached 7 . In-depth interview data are often multivalent and can give rise to different interpretations. The important consideration is, therefore, not merely how many participants are interviewed, but whether one’s research design allows for collecting rich and textured data that provide insight into participants’ understandings, accounts, perceptions and interpretations.

Sometimes, researchers will conduct interviews with more than one participant at a time. Researchers should consider the benefits and shortcomings of such an approach. Joint interviews may, for example, give researchers insight into how caregivers agree or debate childrearing decisions. At the same time, they may be less adaptive to exploring aspects of caregiving that participants may not wish to disclose to each other. In other cases, there may be more than one person interviewing each participant, such as when an interpreter is used, and so it is important to consider during the research design phase how this might shape the dynamics of the interview.

Data collection

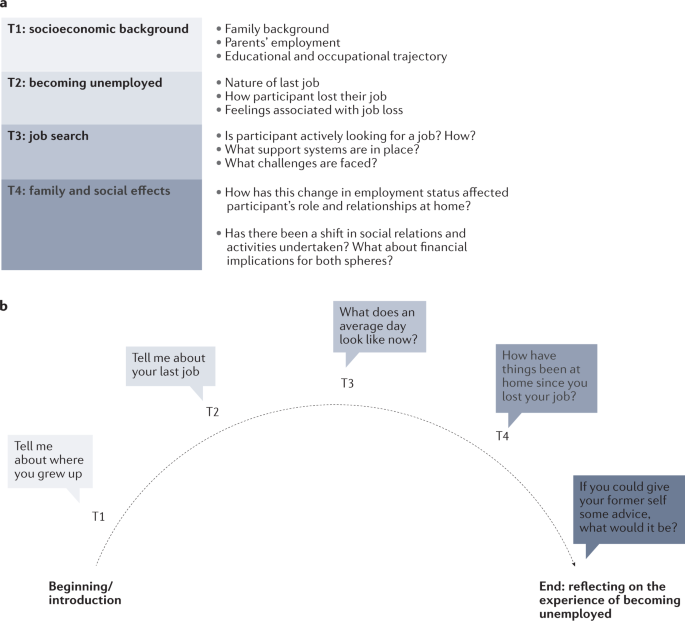

Semi-structured interviews are typically organized around a topic guide comprised of an ordered set of broad topics (usually 3–5). Each topic includes a set of questions that form the basis of the discussion between the researcher and participant (Fig. 1 ). These topics are organized around key concepts that the researcher has identified (for example, through a close study of prior research, or perhaps through piloting a small, exploratory study) 5 .

a | Elaborated topics the researcher wants to cover in the interview and example questions. b | An example topic arc. Using such an arc, one can think flexibly about the order of topics. Considering the main question for each topic will help to determine the best order for the topics. After conducting some interviews, the researcher can move topics around if a different order seems to make sense.

Topic guide

One common way to structure a topic guide is to start with relatively easy, open-ended questions (Table 1 ). Opening questions should be related to the research topic but broad and easy to answer, so that they help to ease the participant into conversation.

After these broad, opening questions, the topic guide may move into topics that speak more directly to the overarching research question. The interview questions will be accompanied by probes designed to elicit concrete details and examples from the participant (see Table 1 ).

Abstract questions are often easier for participants to answer once they have been asked more concrete questions. In our experience, for example, questions about feelings can be difficult for some participants to answer, but when following probes concerning factual experiences these questions can become less challenging. After the main themes of the topic guide have been covered, the topic guide can move onto closing questions. At this stage, participants often repeat something they have said before, although they may sometimes introduce a new topic.

Interviews are especially well suited to gaining a deeper insight into people’s experiences. Getting these insights largely depends on the participants’ willingness to talk to the researcher. We recommend designing open-ended questions that are more likely to elicit an elaborated response and extended reflection from participants rather than questions that can be answered with yes or no.

Questions should avoid foreclosing the possibility that the participant might disagree with the premise of the question. Take for example the question: “Do you support the new family-friendly policies?” This question minimizes the possibility of the participant disagreeing with the premise of this question, which assumes that the policies are ‘family-friendly’ and asks for a yes or no answer. Instead, asking more broadly how a participant feels about the specific policy being described as ‘family-friendly’ (for example, a work-from-home policy) allows them to express agreement, disagreement or impartiality and, crucially, to explain their reasoning 10 .

For an uninterrupted interview that will last between 90 and 120 minutes, the topic guide should be one to two single-spaced pages with questions and probes. Ideally, the researcher will memorize the topic guide before embarking on the first interview. It is fine to carry a printed-out copy of the topic guide but memorizing the topic guide ahead of the interviews can often make the interviewer feel well prepared in guiding the participant through the interview process.

Although the topic guide helps the researcher stay on track with the broad areas they want to cover, there is no need for the researcher to feel tied down by the topic guide. For instance, if a participant brings up a theme that the researcher intended to discuss later or a point the researcher had not anticipated, the researcher may well decide to follow the lead of the participant. The researcher’s role extends beyond simply stating the questions; it entails listening and responding, making split-second decisions about what line of inquiry to pursue and allowing the interview to proceed in unexpected directions.

Optimizing the interview

The ideal place for an interview will depend on the study and what is feasible for participants. Generally, a place where the participant and researcher can both feel relaxed, where the interview can be uninterrupted and where noise or other distractions are limited is ideal. But this may not always be possible and so the researcher needs to be prepared to adapt their plans within what is feasible (and desirable for participants).

Another key tool for the interview is a recording device (assuming that permission for recording has been given). Recording can be important to capture what the participant says verbatim. Additionally, it can allow the researcher to focus on determining what probes and follow-up questions they want to pursue rather than focusing on taking notes. Sometimes, however, a participant may not allow the researcher to record, or the recording may fail. If the interview is not recorded we suggest that the researcher takes brief notes during the interview, if feasible, and then thoroughly make notes immediately after the interview and try to remember the participant’s facial expressions, gestures and tone of voice. Not having a recording of an interview need not limit the researcher from getting analytical value from it.

As soon as possible after each interview, we recommend that the researcher write a one-page interview memo comprising three key sections. The first section should identify two to three important moments from the interview. What constitutes important is up to the researcher’s discretion 9 . The researcher should note down what happened in these moments, including the participant’s facial expressions, gestures, tone of voice and maybe even the sensory details of their surroundings. This exercise is about capturing ethnographic detail from the interview. The second part of the interview memo is the analytical section with notes on how the interview fits in with previous interviews, for example, where the participant’s responses concur or diverge from other responses. The third part consists of a methodological section where the researcher notes their perception of their relationship with the participant. The interview memo allows the researcher to think critically about their positionality and practice reflexivity — key concepts for an ethical and transparent research practice in qualitative methodology 11 , 12 .

Ethics and reflexivity

All elements of an in-depth interview can raise ethical challenges and concerns. Good ethical practice in interview studies often means going beyond the ethical procedures mandated by institutions 13 . While discussions and requirements of ethics can differ across disciplines, here we focus on the most pertinent considerations for interviews across the research process for an interdisciplinary audience.

Ethical considerations prior to interview

Before conducting interviews, researchers should consider harm minimization, informed consent, anonymity and confidentiality, and reflexivity and positionality. It is important for the researcher to develop their own ethical sensitivities and sensibilities by gaining training in interview and qualitative methods, reading methodological and field-specific texts on interviews and ethics and discussing their research plans with colleagues.

Researchers should map the potential harm to consider how this can be minimized. Primarily, researchers should consider harm from the participants’ perspective (Box 1 ). But, it is also important to consider and plan for potential harm to the researcher, research assistants, gatekeepers, future researchers and members of the wider community 14 . Even the most banal of research topics can potentially pose some form of harm to the participant, researcher and others — and the level of harm is often highly context-dependent. For example, a research project on religion in society might have very different ethical considerations in a democratic versus authoritarian research context because of how openly or not such topics can be discussed and debated 15 .

The researcher should consider how they will obtain and record informed consent (for example, written or oral), based on what makes the most sense for their research project and context 16 . Some institutions might specify how informed consent should be gained. Regardless of how consent is obtained, the participant must be made aware of the form of consent, the intentions and procedures of the interview and potential forms of harm and benefit to the participant or community before the interview commences. Moreover, the participant must agree to be interviewed before the interview commences. If, in addition to interviews, the study contains an ethnographic component, it is worth reading around this topic (see, for example, Murphy and Dingwall 17 ). Informed consent must also be gained for how the interview will be recorded before the interview commences. These practices are important to ensure the participant is contributing on a voluntary basis. It is also important to remind participants that they can withdraw their consent at any time during the interview and for a specified period after the interview (to be decided with the participant). The researcher should indicate that participants can ask for anything shared to be off the record and/or not disseminated.

In terms of anonymity and confidentiality, it is standard practice when conducting interviews to agree not to use (or even collect) participants’ names and personal details that are not pertinent to the study. Anonymizing can often be the safer option for minimizing harm to participants as it is hard to foresee all the consequences of de-anonymizing, even if participants agree. Regardless of what a researcher decides, decisions around anonymity must be agreed with participants during the process of gaining informed consent and respected following the interview.

Although not all ethical challenges can be foreseen or planned for 18 , researchers should think carefully — before the interview — about power dynamics, participant vulnerability, emotional state and interactional dynamics between interviewer and participant, even when discussing low-risk topics. Researchers may then wish to plan for potential ethical issues, for example by preparing a list of relevant organizations to which participants can be signposted. A researcher interviewing a participant about debt, for instance, might prepare in advance a list of debt advice charities, organizations and helplines that could provide further support and advice. It is important to remember that the role of an interviewer is as a researcher rather than as a social worker or counsellor because researchers may not have relevant and requisite training in these other domains.

Box 1 Mapping potential forms of harm

Social: researchers should avoid causing any relational detriment to anyone in the course of interviews, for example, by sharing information with other participants or causing interview participants to be shunned or mistreated by their community as a result of participating.

Economic: researchers should avoid causing financial detriment to anyone, for example, by expecting them to pay for transport to be interviewed or to potentially lose their job as a result of participating.

Physical: researchers should minimize the risk of anyone being exposed to violence as a result of the research both from other individuals or from authorities, including police.

Psychological: researchers should minimize the risk of causing anyone trauma (or re-traumatization) or psychological anguish as a result of the research; this includes not only the participant but importantly the researcher themselves and anyone that might read or analyse the transcripts, should they contain triggering information.

Political: researchers should minimize the risk of anyone being exposed to political detriment as a result of the research, such as retribution.

Professional/reputational: researchers should minimize the potential for reputational damage to anyone connected to the research (this includes ensuring good research practices so that any researchers involved are not harmed reputationally by being involved with the research project).

The task here is not to map exhaustively the potential forms of harm that might pertain to a particular research project (that is the researcher’s job and they should have the expertise most suited to mapping such potential harms relative to the specific project) but to demonstrate the breadth of potential forms of harm.

Ethical considerations post-interview

Researchers should consider how interview data are stored, analysed and disseminated. If participants have been offered anonymity and confidentiality, data should be stored in a way that does not compromise this. For example, researchers should consider removing names and any other unnecessary personal details from interview transcripts, password-protecting and encrypting files and using pseudonyms to label and store all interview data. It is also important to address where interview data are taken (for example, across borders in particular where interview data might be of interest to local authorities) and how this might affect the storage of interview data.

Examining how the researcher will represent participants is a paramount ethical consideration both in the planning stages of the interview study and after it has been conducted. Dissemination strategies also need to consider questions of anonymity and representation. In small communities, even if participants are given pseudonyms, it might be obvious who is being described. Anonymizing not only the names of those participating but also the research context is therefore a standard practice 19 . With particularly sensitive data or insights about the participant, it is worth considering describing participants in a more abstract way rather than as specific individuals. These practices are important both for protecting participants’ anonymity but can also affect the ability of the researcher and others to return ethically to the research context and similar contexts 20 .

Reflexivity and positionality

Reflexivity and positionality mean considering the researcher’s role and assumptions in knowledge production 13 . A key part of reflexivity is considering the power relations between the researcher and participant within the interview setting, as well as how researchers might be perceived by participants. Further, researchers need to consider how their own identities shape the kind of knowledge and assumptions they bring to the interview, including how they approach and ask questions and their analysis of interviews (Box 2 ). Reflexivity is a necessary part of developing ethical sensibility as a researcher by adapting and reflecting on how one engages with participants. Participants should not feel judged, for example, when they share information that researchers might disagree with or find objectionable. How researchers deal with uncomfortable moments or information shared by participants is at their discretion, but they should consider how they will react both ahead of time and in the moment.

Researchers can develop their reflexivity by considering how they themselves would feel being asked these interview questions or represented in this way, and then adapting their practice accordingly. There might be situations where these questions are not appropriate in that they unduly centre the researchers’ experiences and worldview. Nevertheless, these prompts can provide a useful starting point for those beginning their reflexive journey and developing an ethical sensibility.

Reflexivity and ethical sensitivities require active reflection throughout the research process. For example, researchers should take care in interview memos and their notes to consider their assumptions, potential preconceptions, worldviews and own identities prior to and after interviews (Box 2 ). Checking in with assumptions can be a way of making sure that researchers are paying close attention to their own theoretical and analytical biases and revising them in accordance with what they learn through the interviews. Researchers should return to these notes (especially when analysing interview material), to try to unpack their own effects on the research process as well as how participants positioned and engaged with them.

Box 2 Aspects to reflect on reflexively

For reflexive engagement, and understanding the power relations being co-constructed and (re)produced in interviews, it is necessary to reflect, at a minimum, on the following.

Ethnicity, race and nationality, such as how does privilege stemming from race or nationality operate between the researcher, the participant and research context (for example, a researcher from a majority community may be interviewing a member of a minority community)

Gender and sexuality, see above on ethnicity, race and nationality

Social class, and in particular the issue of middle-class bias among researchers when formulating research and interview questions

Economic security/precarity, see above on social class and thinking about the researcher’s relative privilege and the source of biases that stem from this

Educational experiences and privileges, see above

Disciplinary biases, such as how the researcher’s discipline/subfield usually approaches these questions, possibly normalizing certain assumptions that might be contested by participants and in the research context

Political and social values

Lived experiences and other dimensions of ourselves that affect and construct our identity as researchers

In this section, we discuss the next stage of an interview study, namely, analysing the interview data. Data analysis may begin while more data are being collected. Doing so allows early findings to inform the focus of further data collection, as part of an iterative process across the research project. Here, the researcher is ultimately working towards achieving coherence between the data collected and the findings produced to answer successfully the research question(s) they have set.

The two most common methods used to analyse interview material across the social sciences are thematic analysis 21 and discourse analysis 22 . Thematic analysis is a particularly useful and accessible method for those starting out in analysis of qualitative data and interview material as a method of coding data to develop and interpret themes in the data 21 . Discourse analysis is more specialized and focuses on the role of discourse in society by paying close attention to the explicit, implicit and taken-for-granted dimensions of language and power 22 , 23 . Although thematic and discourse analysis are often discussed as separate techniques, in practice researchers might flexibly combine these approaches depending on the object of analysis. For example, those intending to use discourse analysis might first conduct thematic analysis as a way to organize and systematize the data. The object and intention of analysis might differ (for example, developing themes or interrogating language), but the questions facing the researcher (such as whether to take an inductive or deductive approach to analysis) are similar.

Preparing data

Data preparation is an important step in the data analysis process. The researcher should first determine what comprises the corpus of material and in what form it will it be analysed. The former refers to whether, for example, alongside the interviews themselves, analytic memos or observational notes that may have been taken during data collection will also be directly analysed. The latter refers to decisions about how the verbal/audio interview data will be transformed into a written form, making it suitable for processes of data analysis. Typically, interview audio recordings are transcribed to produce a written transcript. It is important to note that the process of transcription is one of transformation. The verbal interview data are transformed into a written transcript through a series of decisions that the researcher must make. The researcher should consider the effect of mishearing what has been said or how choosing to punctuate a sentence in a particular way will affect the final analysis.

Box 3 shows an example transcript excerpt from an interview with a teacher conducted by Teeger as part of her study of history education in post-apartheid South Africa 24 (Box 3 ). Seeing both the questions and the responses means that the reader can contextualize what the participant (Ms Mokoena) has said. Throughout the transcript the researcher has used square brackets, for example to indicate a pause in speech, when Ms Mokoena says “it’s [pause] it’s a difficult topic”. The transcription choice made here means that we see that Ms Mokoena has taken time to pause, perhaps to search for the right words, or perhaps because she has a slight apprehension. Square brackets are also included as an overt act of communication to the reader. When Ms Mokoena says “ja”, the English translation (“yes”) of the word in Afrikaans is placed in square brackets to ensure that the reader can follow the meaning of the speech.

Decisions about what to include when transcribing will be hugely important for the direction and possibilities of analysis. Researchers should decide what they want to capture in the transcript, based on their analytic focus. From a (post)positivist perspective 25 , the researcher may be interested in the manifest content of the interview (such as what is said, not how it is said). In that case, they may choose to transcribe intelligent verbatim . From a constructivist perspective 25 , researchers may choose to record more aspects of speech (including, for example, pauses, repetitions, false starts, talking over one another) so that these features can be analysed. Those working from this perspective argue that to recognize the interactional nature of the interview setting adequately and to avoid misinterpretations, features of interaction (pauses, overlaps between speakers and so on) should be preserved in transcription and therefore in the analysis 10 . Readers interested in learning more should consult Potter and Hepburn’s summary of how to present interaction through transcription of interview data 26 .

The process of analysing semi-structured interviews might be thought of as a generative rather than an extractive enterprise. Findings do not already exist within the interview data to be discovered. Rather, researchers create something new when analysing the data by applying their analytic lens or approach to the transcripts. At a high level, there are options as to what researchers might want to glean from their interview data. They might be interested in themes, whereby they identify patterns of meaning across the dataset 21 . Alternatively, they may focus on discourse(s), looking to identify how language is used to construct meanings and therefore how language reinforces or produces aspects of the social world 27 . Alternatively, they might look at the data to understand narrative or biographical elements 28 .

A further overarching decision to make is the extent to which researchers bring predetermined framings or understandings to bear on their data, or instead begin from the data themselves to generate an analysis. One way of articulating this is the extent to which researchers take a deductive approach or an inductive approach to analysis. One example of a truly inductive approach is grounded theory, whereby the aim of the analysis is to build new theory, beginning with one’s data 6 , 29 . In practice, researchers using thematic and discourse analysis often combine deductive and inductive logics and describe their process instead as iterative (referred to also as an abductive approach ) 30 , 31 . For example, researchers may decide that they will apply a given theoretical framing, or begin with an initial analytic framework, but then refine or develop these once they begin the process of analysis.

Box 3 Excerpt of interview transcript (from Teeger 24 )

Interviewer : Maybe you could just start by talking about what it’s like to teach apartheid history.

Ms Mokoena : It’s a bit challenging. You’ve got to accommodate all the kids in the class. You’ve got to be sensitive to all the racial differences. You want to emphasize the wrongs that were done in the past but you also want to, you know, not to make kids feel like it’s their fault. So you want to use the wrongs of the past to try and unite the kids …

Interviewer : So what kind of things do you do?

Ms Mokoena : Well I normally highlight the fact that people that were struggling were not just the blacks, it was all the races. And I give examples of the people … from all walks of life, all races, and highlight how they suffered as well as a result of apartheid, particularly the whites… . What I noticed, particularly my first year of teaching apartheid, I noticed that the black kids made the others feel responsible for what happened… . I had a lot of fights…. A lot of kids started hating each other because, you know, the others are white and the others were black. And they started saying, “My mother is a domestic worker because she was never allowed an opportunity to get good education.” …

Interviewer : I didn’t see any of that now when I was observing.

Ms Mokoena : … Like I was saying I think that because of the re-emphasis of the fact that, look, everybody did suffer one way or the other, they sort of got to see that it was everybody’s struggle … . They should now get to understand that that’s why we’re called a Rainbow Nation. Not everybody agreed with apartheid and not everybody suffered. Even all the blacks, not all blacks got to feel what the others felt . So ja [yes], it’s [pause] it’s a difficult topic, ja . But I think if you get the kids to understand why we’re teaching apartheid in the first place and you show the involvement of all races in all the different sides , then I think you have managed to teach it properly. So I think because of my inexperience then — that was my first year of teaching history — so I think I — maybe I over-emphasized the suffering of the blacks versus the whites [emphasis added].

Reprinted with permission from ref. 24 , Sage Publications.

From data to codes

Coding data is a key building block shared across many approaches to data analysis. Coding is a way of organizing and describing data, but is also ultimately a way of transforming data to produce analytic insights. The basic practice of coding involves highlighting a segment of text (this may be a sentence, a clause or a longer excerpt) and assigning a label to it. The aim of the label is to communicate some sort of summary of what is in the highlighted piece of text. Coding is an iterative process, whereby researchers read and reread their transcripts, applying and refining their codes, until they have a coding frame (a set of codes) that is applied coherently across the dataset and that captures and communicates the key features of what is contained in the data as it relates to the researchers’ analytic focus.

What one codes for is entirely contingent on the focus of the research project and the choices the researcher makes about the approach to analysis. At first, one might apply descriptive codes, summarizing what is contained in the interviews. It is rarely desirable to stop at this point, however, because coding is a tool to move from describing the data to interpreting the data. Suppose the researcher is pursuing some version of thematic analysis. In that case, it might be that the objects of coding are aspects of reported action, emotions, opinions, norms, relationships, routines, agreement/disagreement and change over time. A discourse analysis might instead code for different types of speech acts, tropes, linguistic or rhetorical devices. Multiple types of code might be generated within the same research project. What is important is that researchers are aware of the choices they are making in terms of what they are coding for. Moreover, through the process of refinement, the aim is to produce a set of discrete codes — in which codes are conceptually distinct, as opposed to overlapping. By using the same codes across the dataset, the researcher can capture commonalities across the interviews. This process of refinement involves relabelling codes and reorganizing how and where they are applied in the dataset.

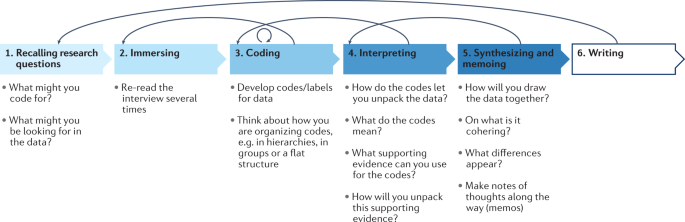

From coding to analysis and writing

Data analysis is also an iterative process in which researchers move closer to and further away from the data. As they move away from the data, they synthesize their findings, thus honing and articulating their analytic insights. As they move closer to the data, they ground these insights in what is contained in the interviews. The link should not be broken between the data themselves and higher-order conceptual insights or claims being made. Researchers must be able to show evidence for their claims in the data. Figure 2 summarizes this iterative process and suggests the sorts of activities involved at each stage more concretely.

As well as going through steps 1 to 6 in order, the researcher will also go backwards and forwards between stages. Some stages will themselves be a forwards and backwards processing of coding and refining when working across different interview transcripts.

At the stage of synthesizing, there are some common quandaries. When dealing with a dataset consisting of multiple interviews, there will be salient and minority statements across different participants, or consensus or dissent on topics of interest to the researcher. A strength of qualitative interviews is that we can build in these nuances and variations across our data as opposed to aggregating them away. When exploring and reporting data, researchers should be asking how different findings are patterned and which interviews contain which codes, themes or tropes. Researchers should think about how these variations fit within the longer flow of individual interviews and what these variations tell them about the nature of their substantive research interests.

A further consideration is how to approach analysis within and across interview data. Researchers may look at one individual code, to examine the forms it takes across different participants and what they might be able to summarize about this code in the round. Alternatively, they might look at how a code or set of codes pattern across the account of one participant, to understand the code(s) in a more contextualized way. Further analysis might be done according to different sampling characteristics, where researchers group together interviews based on certain demographic characteristics and explore these together.

When it comes to writing up and presenting interview data, key considerations tend to rest on what is often termed transparency. When presenting the findings of an interview-based study, the reader should be able to understand and trace what the stated findings are based upon. This process typically involves describing the analytic process, how key decisions were made and presenting direct excerpts from the data. It is important to account for how the interview was set up and to consider the active part that the researcher has played in generating the data 32 . Quotes from interviews should not be thought of as merely embellishing or adding interest to a final research output. Rather, quotes serve the important function of connecting the reader directly to the underlying data. Quotes, therefore, should be chosen because they provide the reader with the most apt insight into what is being discussed. It is good practice to report not just on what participants said, but also on the questions that were asked to elicit the responses.

Researchers have increasingly used specialist qualitative data analysis software to organize and analyse their interview data, such as NVivo or ATLAS.ti. It is important to remember that such software is a tool for, rather than an approach or technique of, analysis. That said, software also creates a wide range of possibilities in terms of what can be done with the data. As researchers, we should reflect on how the range of possibilities of a given software package might be shaping our analytical choices and whether these are choices that we do indeed want to make.

Applications

This section reviews how and why in-depth interviews have been used by researchers studying gender, education and inequality, nationalism and ethnicity and the welfare state. Although interviews can be employed as a method of data collection in just about any social science topic, the applications below speak directly to the authors’ expertise and cutting-edge areas of research.

When it comes to the broad study of gender, in-depth interviews have been invaluable in shaping our understanding of how gender functions in everyday life. In a study of the US hedge fund industry (an industry dominated by white men), Tobias Neely was interested in understanding the factors that enable white men to prosper in the industry 33 . The study comprised interviews with 45 hedge fund workers and oversampled women of all races and men of colour to capture a range of experiences and beliefs. Tobias Neely found that practices of hiring, grooming and seeding are key to maintaining white men’s dominance in the industry. In terms of hiring, the interviews clarified that white men in charge typically preferred to hire people like themselves, usually from their extended networks. When women were hired, they were usually hired to less lucrative positions. In terms of grooming, Tobias Neely identifies how older and more senior men in the industry who have power and status will select one or several younger men as their protégés, to include in their own elite networks. Finally, in terms of her concept of seeding, Tobias Neely describes how older men who are hedge fund managers provide the seed money (often in the hundreds of millions of dollars) for a hedge fund to men, often their own sons (but not their daughters). These interviews provided an in-depth look into gendered and racialized mechanisms that allow white men to flourish in this industry.

Research by Rao draws on dozens of interviews with men and women who had lost their jobs, some of the participants’ spouses and follow-up interviews with about half the sample approximately 6 months after the initial interview 34 . Rao used interviews to understand the gendered experience and understanding of unemployment. Through these interviews, she found that the very process of losing their jobs meant different things for men and women. Women often saw job loss as being a personal indictment of their professional capabilities. The women interviewed often referenced how years of devaluation in the workplace coloured their interpretation of their job loss. Men, by contrast, were also saddened by their job loss, but they saw it as part and parcel of a weak economy rather than a personal failing. How these varied interpretations occurred was tied to men’s and women’s very different experiences in the workplace. Further, through her analysis of these interviews, Rao also showed how these gendered interpretations had implications for the kinds of jobs men and women sought to pursue after job loss. Whereas men remained tied to participating in full-time paid work, job loss appeared to be a catalyst pushing some of the women to re-evaluate their ties to the labour force.

In a study of workers in the tech industry, Hart used interviews to explain how individuals respond to unwanted and ambiguously sexual interactions 35 . Here, the researcher used interviews to allow participants to describe how these interactions made them feel and act and the logics of how they interpreted, classified and made sense of them 35 . Through her analysis of these interviews, Hart showed that participants engaged in a process she termed “trajectory guarding”, whereby they sought to monitor unwanted and ambiguously sexual interactions to avoid them from escalating. Yet, as Hart’s analysis proficiently demonstrates, these very strategies — which protect these workers sexually — also undermined their workplace advancement.

Drawing on interviews, these studies have helped us to understand better how gendered mechanisms, gendered interpretations and gendered interactions foster gender inequality when it comes to paid work. Methodologically, these studies illuminate the power of interviews to reveal important aspects of social life.

Nationalism and ethnicity

Traditionally, nationalism has been studied from a top-down perspective, through the lens of the state or using historical methods; in other words, in-depth interviews have not been a common way of collecting data to study nationalism. The methodological turn towards everyday nationalism has encouraged more scholars to go to the field and use interviews (and ethnography) to understand nationalism from the bottom up: how people talk about, give meaning, understand, navigate and contest their relation to nation, national identification and nationalism 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 . This turn has also addressed the gap left by those studying national and ethnic identification via quantitative methods, such as surveys.

Surveys can enumerate how individuals ascribe to categorical forms of identification 40 . However, interviews can question the usefulness of such categories and ask whether these categories are reflected, or resisted, by participants in terms of the meanings they give to identification 41 , 42 . Categories often pitch identification as a mutually exclusive choice; but identification might be more complex than such categories allow. For example, some might hybridize these categories or see themselves as moving between and across categories 43 . Hearing how people talk about themselves and their relation to nations, states and ethnicities, therefore, contributes substantially to the study of nationalism and national and ethnic forms of identification.

One particular approach to studying these topics, whether via everyday nationalism or alternatives, is that of using interviews to capture both articulations and narratives of identification, relations to nationalism and the boundaries people construct. For example, interviews can be used to gather self–other narratives by studying how individuals construct I–we–them boundaries 44 , including how participants talk about themselves, who participants include in their various ‘we’ groupings and which and how participants create ‘them’ groupings of others, inserting boundaries between ‘I/we’ and ‘them’. Overall, interviews hold great potential for listening to participants and understanding the nuances of identification and the construction of boundaries from their point of view.

Education and inequality

Scholars of social stratification have long noted that the school system often reproduces existing social inequalities. Carter explains that all schools have both material and sociocultural resources 45 . When children from different backgrounds attend schools with different material resources, their educational and occupational outcomes are likely to vary. Such material resources are relatively easy to measure. They are operationalized as teacher-to-student ratios, access to computers and textbooks and the physical infrastructure of classrooms and playgrounds.

Drawing on Bourdieusian theory 46 , Carter conceptualizes the sociocultural context as the norms, values and dispositions privileged within a social space 45 . Scholars have drawn on interviews with students and teachers (as well as ethnographic observations) to show how schools confer advantages on students from middle-class families, for example, by rewarding their help-seeking behaviours 47 . Focusing on race, researchers have revealed how schools can remain socioculturally white even as they enrol a racially diverse student population. In such contexts, for example, teachers often misrecognize the aesthetic choices made by students of colour, wrongly inferring that these students’ tastes in clothing and music reflect negative orientations to schooling 48 , 49 , 50 . These assessments can result in disparate forms of discipline and may ultimately shape educators’ assessments of students’ academic potential 51 .

Further, teachers and administrators tend to view the appropriate relationship between home and school in ways that resonate with white middle-class parents 52 . These parents are then able to advocate effectively for their children in ways that non-white parents are not 53 . In-depth interviews are particularly good at tapping into these understandings, revealing the mechanisms that confer privilege on certain groups of students and thereby reproduce inequality.

In addition, interviews can shed light on the unequal experiences that young people have within educational institutions, as the views of dominant groups are affirmed while those from disadvantaged backgrounds are delegitimized. For example, Teeger’s interviews with South African high schoolers showed how — because racially charged incidents are often framed as jokes in the broader school culture — Black students often feel compelled to ignore and keep silent about the racism they experience 54 . Interviews revealed that Black students who objected to these supposed jokes were coded by other students as serious or angry. In trying to avoid such labels, these students found themselves unable to challenge the racism they experienced. Interviews give us insight into these dynamics and help us see how young people understand and interpret the messages transmitted in schools — including those that speak to issues of inequality in their local school contexts as well as in society more broadly 24 , 55 .

The welfare state

In-depth interviews have also proved to be an important method for studying various aspects of the welfare state. By welfare state, we mean the social institutions relating to the economic and social wellbeing of a state’s citizens. Notably, using interviews has been useful to look at how policy design features are experienced and play out on the ground. Interviews have often been paired with large-scale surveys to produce mixed-methods study designs, therefore achieving both breadth and depth of insights.

In-depth interviews provide the opportunity to look behind policy assumptions or how policies are designed from the top down, to examine how these play out in the lives of those affected by the policies and whose experiences might otherwise be obscured or ignored. For example, the Welfare Conditionality project used interviews to critique the assumptions that conditionality (such as, the withdrawal of social security benefits if recipients did not perform or meet certain criteria) improved employment outcomes and instead showed that conditionality was harmful to mental health, living standards and had many other negative consequences 56 . Meanwhile, combining datasets from two small-scale interview studies with recipients allowed Summers and Young to critique assumptions around the simplicity that underpinned the design of Universal Credit in 2020, for example, showing that the apparently simple monthly payment design instead burdened recipients with additional money management decisions and responsibilities 57 .

Similarly, the Welfare at a (Social) Distance project used a mixed-methods approach in a large-scale study that combined national surveys with case studies and in-depth interviews to investigate the experience of claiming social security benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic. The interviews allowed researchers to understand in detail any issues experienced by recipients of benefits, such as delays in the process of claiming, managing on a very tight budget and navigating stigma and claiming 58 .

These applications demonstrate the multi-faceted topics and questions for which interviews can be a relevant method for data collection. These applications highlight not only the relevance of interviews, but also emphasize the key added value of interviews, which might be missed by other methods (surveys, in particular). Interviews can expose and question what is taken for granted and directly engage with communities and participants that might otherwise be ignored, obscured or marginalized.

Reproducibility and data deposition

There is a robust, ongoing debate about reproducibility in qualitative research, including interview studies. In some research paradigms, reproducibility can be a way of interrogating the rigour and robustness of research claims, by seeing whether these hold up when the research process is repeated. Some scholars have suggested that although reproducibility may be challenging, researchers can facilitate it by naming the place where the research was conducted, naming participants, sharing interview and fieldwork transcripts (anonymized and de-identified in cases where researchers are not naming people or places) and employing fact-checkers for accuracy 11 , 59 , 60 .

In addition to the ethical concerns of whether de-anonymization is ever feasible or desirable, it is also important to address whether the replicability of interview studies is meaningful. For example, the flexibility of interviews allows for the unexpected and the unforeseen to be incorporated into the scope of the research 61 . However, this flexibility means that we cannot expect reproducibility in the conventional sense, given that different researchers will elicit different types of data from participants. Sharing interview transcripts with other researchers, for instance, downplays the contextual nature of an interview.

Drawing on Bauer and Gaskell, we propose several measures to enhance rigour in qualitative research: transparency, grounding interpretations and aiming for theoretical transferability and significance 62 .

Researchers should be transparent when describing their methodological choices. Transparency means documenting who was interviewed, where and when (without requiring de-anonymization, for example, by documenting their characteristics), as well as the questions they were asked. It means carefully considering who was left out of the interviews and what that could mean for the researcher’s findings. It also means carefully considering who the researcher is and how their identity shaped the research process (integrating and articulating reflexivity into whatever is written up).

Second, researchers should ground their interpretations in the data. Grounding means presenting the evidence upon which the interpretation relies. Quotes and extracts should be extensive enough to allow the reader to evaluate whether the researcher’s interpretations are grounded in the data. At each step, researchers should carefully compare their own explanations and interpretations with alternative explanations. Doing so systematically and frequently allows researchers to become more confident in their claims. Here, researchers should justify the link between data and analysis by using quotes to justify and demonstrate the analytical point, while making sure the analytical point offers an interpretation of quotes (Box 4 ).

An important step in considering alternative explanations is to seek out disconfirming evidence 4 , 63 . This involves looking for instances where participants deviate from what the majority are saying and thus bring into question the theory (or explanation) that the researcher is developing. Careful analysis of such examples can often demonstrate the salience and meaning of what appears to be the norm (see Table 2 for examples) 54 . Considering alternative explanations and paying attention to disconfirming evidence allows the researcher to refine their own theories in respect of the data.

Finally, researchers should aim for theoretical transferability and significance in their discussions of findings. One way to think about this is to imagine someone who is not interested in the empirical study. Articulating theoretical transferability and significance usually takes the form of broadening out from the specific findings to consider explicitly how the research has refined or altered prior theoretical approaches. This process also means considering under what other conditions, aside from those of the study, the researcher thinks their theoretical revision would be supported by and why. Importantly, it also includes thinking about the limitations of one’s own approach and where the theoretical implications of the study might not hold.

Box 4 An example of grounding interpretations in data (from Rao 34 )

In an article explaining how unemployed men frame their job loss as a pervasive experience, Rao writes the following: “Unemployed men in this study understood unemployment to be an expected aspect of paid work in the contemporary United States. Robert, a white unemployed communications professional, compared the economic landscape after the Great Recession with the tragic events of September 11, 2001:

Part of your post-9/11 world was knowing people that died as a result of terrorism. The same thing is true with the [Great] Recession, right? … After the Recession you know somebody who was unemployed … People that really should be working.

The pervasiveness of unemployment rendered it normal, as Robert indicates.”

Here, the link between the quote presented and the analytical point Rao is making is clear: the analytical point is grounded in a quote and an interpretation of the quote is offered 34 .

Limitations and optimizations

When deciding which research method to use, the key question is whether the method provides a good fit for the research questions posed. In other words, researchers should consider whether interviews will allow them to successfully access the social phenomena necessary to answer their question(s) and whether the interviews will do so more effectively than other methods. Table 3 summarizes the major strengths and limitations of interviews. However, the accompanying text below is organized around some key issues, where relative strengths and weaknesses are presented alongside each other, the aim being that readers should think about how these can be balanced and optimized in relation to their own research.

Breadth versus depth of insight

Achieving an overall breadth of insight, in a statistically representative sense, is not something that is possible or indeed desirable when conducting in-depth interviews. Instead, the strength of conducting interviews lies in their ability to generate various sorts of depth of insight. The experiences or views of participants that can be accessed by conducting interviews help us to understand participants’ subjective realities. The challenge, therefore, is for researchers to be clear about why depth of insight is the focus and what we should aim to glean from these types of insight.

Naturalistic or artificial interviews

Interviews make use of a form of interaction with which people are familiar 64 . By replicating a naturalistic form of interaction as a tool to gather social science data, researchers can capitalize on people’s familiarity and expectations of what happens in a conversation. This familiarity can also be a challenge, as people come to the interview with preconceived ideas about what this conversation might be for or about. People may draw on experiences of other similar conversations when taking part in a research interview (for example, job interviews, therapy sessions, confessional conversations, chats with friends). Researchers should be aware of such potential overlaps and think through their implications both in how the aims and purposes of the research interview are communicated to participants and in how interview data are interpreted.

Further, some argue that a limitation of interviews is that they are an artificial form of data collection. By taking people out of their daily lives and asking them to stand back and pass comment, we are creating a distance that makes it difficult to use such data to say something meaningful about people’s actions, experiences and views. Other approaches, such as ethnography, might be more suitable for tapping into what people actually do, as opposed to what they say they do 65 .

Dynamism and replicability

Interviews following a semi-structured format offer flexibility both to the researcher and the participant. As the conversation develops, the interlocutors can explore the topics raised in much more detail, if desired, or pass over ones that are not relevant. This flexibility allows for the unexpected and the unforeseen to be incorporated into the scope of the research.

However, this flexibility has a related challenge of replicability. Interviews cannot be reproduced because they are contingent upon the interaction between the researcher and the participant in that given moment of interaction. In some research paradigms, replicability can be a way of interrogating the robustness of research claims, by seeing whether they hold when they are repeated. This is not a useful framework to bring to in-depth interviews and instead quality criteria (such as transparency) tend to be employed as criteria of rigour.

Accessing the private and personal

Interviews have been recognized for their strength in accessing private, personal issues, which participants may feel more comfortable talking about in a one-to-one conversation. Furthermore, interviews are likely to take a more personable form with their extended questions and answers, perhaps making a participant feel more at ease when discussing sensitive topics in such a context. There is a similar, but separate, argument made about accessing what are sometimes referred to as vulnerable groups, who may be difficult to make contact with using other research methods.

There is an associated challenge of anonymity. There can be types of in-depth interview that make it particularly challenging to protect the identities of participants, such as interviewing within a small community, or multiple members of the same household. The challenge to ensure anonymity in such contexts is even more important and difficult when the topic of research is of a sensitive nature or participants are vulnerable.

Increasingly, researchers are collaborating in large-scale interview-based studies and integrating interviews into broader mixed-methods designs. At the same time, interviews can be seen as an old-fashioned (and perhaps outdated) mode of data collection. We review these debates and discussions and point to innovations in interview-based studies. These include the shift from face-to-face interviews to the use of online platforms, as well as integrating and adapting interviews towards more inclusive methodologies.

Collaborating and mixing

Qualitative researchers have long worked alone 66 . Increasingly, however, researchers are collaborating with others for reasons such as efficiency, institutional incentives (for example, funding for collaborative research) and a desire to pool expertise (for example, studying similar phenomena in different contexts 67 or via different methods). Collaboration can occur across disciplines and methods, cases and contexts and between industry/business, practitioners and researchers. In many settings and contexts, collaboration has become an imperative 68 .

Cheek notes how collaboration provides both advantages and disadvantages 68 . For example, collaboration can be advantageous, saving time and building on the divergent knowledge, skills and resources of different researchers. Scholars with different theoretical or case-based knowledge (or contacts) can work together to build research that is comparative and/or more than the sum of its parts. But such endeavours also carry with them practical and political challenges in terms of how resources might actually be pooled, shared or accounted for. When undertaking such projects, as Morse notes, it is worth thinking about the nature of the collaboration and being explicit about such a choice, its advantages and its disadvantages 66 .

A further tension, but also a motivation for collaboration, stems from integrating interviews as a method in a mixed-methods project, whether with other qualitative researchers (to combine with, for example, focus groups, document analysis or ethnography) or with quantitative researchers (to combine with, for example, surveys, social media analysis or big data analysis). Cheek and Morse both note the pitfalls of collaboration with quantitative researchers: that quality of research may be sacrificed, qualitative interpretations watered down or not taken seriously, or tensions experienced over the pace and different assumptions that come with different methods and approaches of research 66 , 68 .

At the same time, there can be real benefits of such mixed-methods collaboration, such as reaching different and more diverse audiences or testing assumptions and theories between research components in the same project (for example, testing insights from prior quantitative research via interviews, or vice versa), as long as the skillsets of collaborators are seen as equally beneficial to the project. Cheek provides a set of questions that, as a starting point, can be useful for guiding collaboration, whether mixed methods or otherwise. First, Cheek advises asking all collaborators about their assumptions and understandings concerning collaboration. Second, Cheek recommends discussing what each perspective highlights and focuses on (and conversely ignores or sidelines) 68 .

A different way to engage with the idea of collaboration and mixed methods research is by fostering greater collaboration between researchers in the Global South and Global North, thus reversing trends of researchers from the Global North extracting knowledge from the Global South 69 . Such forms of collaboration also align with interview innovations, discussed below, that seek to transform traditional interview approaches into more participatory and inclusive (as part of participatory methodologies).

Digital innovations and challenges

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has centred the question of technology within interview-based fieldwork. Although conducting synchronous oral interviews online — for example, via Zoom, Skype or other such platforms — has been a method used by a small constituency of researchers for many years, it became (and remains) a necessity for many researchers wanting to continue or start interview-based projects while COVID-19 prevents face-to-face data collection.

In the past, online interviews were often framed as an inferior form of data collection for not providing the kinds of (often necessary) insights and forms of immersion face-to-face interviews allow 70 , 71 . Online interviews do tend to be more decontextualized than interviews conducted face-to-face 72 . For example, it is harder to recognize, engage with and respond to non-verbal cues 71 . At the same time, they broaden participation to those who might not have been able to access or travel to sites where interviews would have been conducted otherwise, for example people with disabilities. Online interviews also offer more flexibility in terms of scheduling and time requirements. For example, they provide more flexibility around precarious employment or caring responsibilities without having to travel and be away from home. In addition, online interviews might also reduce discomfort between researchers and participants, compared with face-to-face interviews, enabling more discussion of sensitive material 71 . They can also provide participants with more control, enabling them to turn on and off the microphone and video as they choose, for example, to provide more time to reflect and disconnect if they so wish 72 .

That said, online interviews can also introduce new biases based on access to technology 72 . For example, in the Global South, there are often urban/rural and gender gaps between who has access to mobile phones and who does not, meaning that some population groups might be overlooked unless researchers sample mindfully 71 . There are also important ethical considerations when deciding between online and face-to-face interviews. Online interviews might seem to imply lower ethical risks than face-to-face interviews (for example, they lower the chances of identification of participants or researchers), but they also offer more barriers to building trust between researchers and participants 72 . Interacting only online with participants might not provide the information needed to assess risk, for example, participants’ access to a private space to speak 71 . Just because online interviews might be more likely to be conducted in private spaces does not mean that private spaces are safe, for example, for victims of domestic violence. Finally, online interviews prompt further questions about decolonizing research and engaging with participants if research is conducted from afar 72 , such as how to include participants meaningfully and challenge dominant assumptions while doing so remotely.

A further digital innovation, modulating how researchers conduct interviews and the kinds of data collected and analysed, stems from the use and integration of (new) technology, such as WhatsApp text or voice notes to conduct synchronous or asynchronous oral or written interviews 73 . Such methods can provide more privacy, comfort and control to participants and make recruitment easier, allowing participants to share what they want when they want to, using technology that already forms a part of their daily lives, especially for young people 74 , 75 . Such technology is also emerging in other qualitative methods, such as focus groups, with similar arguments around greater inclusivity versus traditional offline modes. Here, the digital challenge might be higher for researchers than for participants if they are less used to such technology 75 . And while there might be concerns about the richness, depth and quality of written messages as a form of interview data, Gibson reports that the reams of transcripts that resulted from a study using written messaging were dense with meaning to be analysed 75 .

Like with online and face-to-face interviews, it is important also to consider the ethical questions and challenges of using such technology, from gaining consent to ensuring participant safety and attending to their distress, without cues, like crying, that might be more obvious in a face-to-face setting 75 , 76 . Attention to the platform used for such interviews is also important and researchers should be attuned to the local and national context. For example, in China, many platforms are neither legal nor available 76 . There, more popular platforms — like WeChat — can be highly monitored by the government, posing potential risks to participants depending on the topic of the interview. Ultimately, researchers should consider trade-offs between online and offline interview modalities, being attentive to the social context and power dynamics involved.

The next 5–10 years

Continuing to integrate (ethically) this technology will be among the major persisting developments in interview-based research, whether to offer more flexibility to researchers or participants, or to diversify who can participate and on what terms.

Pushing the idea of inclusion even further is the potential for integrating interview-based studies within participatory methods, which are also innovating via integrating technology. There is no hard and fast line between researchers using in-depth interviews and participatory methods; many who employ participatory methods will use interviews at the beginning, middle or end phases of a research project to capture insights, perspectives and reflections from participants 77 , 78 . Participatory methods emphasize the need to resist existing power and knowledge structures. They broaden who has the right and ability to contribute to academic knowledge by including and incorporating participants not only as subjects of data collection, but as crucial voices in research design and data analysis 77 . Participatory methods also seek to facilitate local change and to produce research materials, whether for academic or non-academic audiences, including films and documentaries, in collaboration with participants.

In responding to the challenges of COVID-19, capturing the fraught situation wrought by the pandemic and the momentum to integrate technology, participatory researchers have sought to continue data collection from afar. For example, Marzi has adapted an existing project to co-produce participatory videos, via participants’ smartphones in Medellin, Colombia, alongside regular check-in conversations/meetings/interviews with participants 79 . Integrating participatory methods into interview studies offers a route by which researchers can respond to the challenge of diversifying knowledge, challenging assumptions and power hierarchies and creating more inclusive and collaborative partnerships between participants and researchers in the Global North and South.

Brinkmann, S. & Kvale, S. Doing Interviews Vol. 2 (Sage, 2018). This book offers a good general introduction to the practice and design of interview-based studies.

Silverman, D. A Very Short, Fairly Interesting And Reasonably Cheap Book About Qualitative Research (Sage, 2017).

Yin, R. K. Case Study Research And Applications: Design And Methods (Sage, 2018).

Small, M. L. How many cases do I need?’ On science and the logic of case selection in field-based research. Ethnography 10 , 5–38 (2009). This article convincingly demonstrates how the logic of qualitative research differs from quantitative research and its goal of representativeness.

Google Scholar

Gerson, K. & Damaske, S. The Science and Art of Interviewing (Oxford Univ. Press, 2020).

Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. L. The Discovery Of Grounded Theory: Strategies For Qualitative Research (Aldine, 1967).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 13 , 201–216 (2021).

Guest, G., Bunce, A. & Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18 , 59–82 (2006).

Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S. & Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18 , 148 (2018).

Silverman, D. How was it for you? The Interview Society and the irresistible rise of the (poorly analyzed) interview. Qual. Res. 17 , 144–158 (2017).

Jerolmack, C. & Murphy, A. The ethical dilemmas and social scientific tradeoffs of masking in ethnography. Sociol. Methods Res. 48 , 801–827 (2019).

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Reyes, V. Ethnographic toolkit: strategic positionality and researchers’ visible and invisible tools in field research. Ethnography 21 , 220–240 (2020).

Guillemin, M. & Gillam, L. Ethics, reflexivity and “ethically important moments” in research. Qual. Inq. 10 , 261–280 (2004).

Summers, K. For the greater good? Ethical reflections on interviewing the ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ in qualitative research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 23 , 593–602 (2020). This article argues that, in qualitative interview research, a clearer distinction needs to be drawn between ethical commitments to individual research participants and the group(s) to which they belong, a distinction that is often elided in existing ethics guidelines.

Yusupova, G. Exploring sensitive topics in an authoritarian context: an insider perspective. Soc. Sci. Q. 100 , 1459–1478 (2019).

Hemming, J. in Surviving Field Research: Working In Violent And Difficult Situations 21–37 (Routledge, 2009).

Murphy, E. & Dingwall, R. Informed consent, anticipatory regulation and ethnographic practice. Soc. Sci. Med. 65 , 2223–2234 (2007).