- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

15.3: Action research

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 25685

- Matthew DeCarlo

- Radford University via Open Social Work Education

Learning Objectives

- Define and provide at least one example of action research

- Describe the role of stakeholders in action research

Action research is defined as research that is conducted for the purpose of creating social change. When conducting action research, scholars collaborate with community stakeholders at all stages of the research process with the aim of producing results that will be usable in the community and by scientists. We defined stakeholders in Chapter 8, as individuals or groups who have an interest in the outcome of your study. Social workers who engage in action research never just go it alone; instead, they collaborate with the people who are affected by the research at each stage in the process. Stakeholders, particularly those with the least power, should be consulted on the purpose of the research project, research questions, design, and reporting of results.

Action research also distinguishes itself from other research in that its purpose is to create change on an individual and community level. Kristin Esterberg puts it quite eloquently when she says, “At heart, all action researchers are concerned that research not simply contribute to knowledge but also lead to positive changes in people’s lives” (2002, p. 137). [1] As you might imagine, action research is consistent with the assumptions of the critical paradigm, which focuses on liberating people from oppressive structures. Action research has multiple origins across the globe, including Kurt Lewin’s psychological experiments in the US and Paulo Friere’s literacy and education programs (Adelman, 1993; Reason, 1994). [2] Over the years, action research has become increasingly popular among scholars who wish for their work to have tangible outcomes that benefit the groups they study.

Action research does not bring any new methodological tricks or terms, but it uses the processes of science in a different way than traditional research. What topics are important to study in a neighborhood or with a target population? A traditional scientist might look at the literature or use their practice wisdom to formulate a question for quantitative or qualitative research. An action researcher, on the other hand, would consult with the target population itself to see what they thought the most pressing issues are and their proposed solutions. In this way, action research flips traditional research on its head. Scientists are more like consultants who provide the tools and resources necessary for a target population to achieve their goals and address social problems.

According to Healy (2001), [3] the assumptions of participatory-action research are that (a) oppression is caused by macro-level structures such as patriarchy and capitalism; (b) research should expose and confront the powerful; (c) researcher and participant relationships should be equal, with equitable distribution of research tasks and roles; and (d) research should result in consciousness-raising and collective action. Coherent with social work values, action research supports the self-determination of oppressed groups and privileges their voice and understanding through the conceptualization, design, data collection, data analysis, and dissemination processes of research.

There are many excellent examples of action research. Some of them focus solely on arriving at useful outcomes for the communities upon which and with whom research is conducted. Other action research projects result in some new knowledge that has a practical application and purpose in addition to the creation of knowledge for basic scientific purposes.

One example of action research can be seen in Fred Piercy and colleagues’ (Piercy, Franz, Donaldson, & Richard, 2011) [4] work with farmers in Virginia, Tennessee, and Louisiana. Together with farmers in these states, the researchers conducted focus groups to understand how farmers learn new information about farming. Ultimately, the aim of this study was to “develop more meaningful ways to communicate information to farmers about sustainable agriculture” (p. 820). This improved communication, the researchers and farmers believed, would benefit not just researchers interested in the topic but also farmers and their communities. Farmers and researchers were both involved in all aspects of the research, from designing the project and determining focus group questions to conducting the focus groups and finally to analyzing data and disseminating findings.

Many additional examples of action research can be found at Loyola University Chicago’s Center for Urban Research and Learning (CURL; http://www.luc.edu/curl/index.shtml ). The mission of the center is to create “innovative solutions that promote equity and opportunity in communities throughout the Chicago metropolitan region” (CURL, n.d., para. 1). [5] For example, in 2006 researchers at CURL embarked on a project to assess the impact on small, local retailers of new Walmart stores entering urban areas (Jones, 2008). [6] The study found that while the effect of Walmart on local retailers seems to have a larger impact in rural areas, Chicago-area local retailers did not experience as dramatic an impact. Nevertheless a “small but statistically significant relationship” was found between Walmart’s arrival in the city and local retailers’ closing their doors (Jones, 2008, para. 3). This and other research conducted by CURL aims to raise awareness about and promote positive social change around issues affecting the lives of people in the Chicago area. CURL meets this aim by collaborating with members of the community to shape a research agenda, collect and analyze data, and disseminate results.

Perhaps one of the most unique and rewarding aspects of engaging in action research is that it is often interdisciplinary. Action research projects might bring together researchers from any number of disciplines, from the social sciences, such as sociology, political science, and psychology; to an assortment of physical and natural sciences, such as biology and chemistry; to engineering, philosophy, and history (to name just a few). One recent example of this kind of interdisciplinary action research can be seen in the University of Maine’s Sustainability Solutions Initiative (SSI) ( https://umaine.edu/mitchellcenter/sustainability-solutions-initiative/ ). This initiative unites researchers from across campus together with local community members to “connect knowledge with action in ways that promote strong economies, vibrant communities, and healthy ecosystems in and beyond Maine” (Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions, para. 1). [7] The knowledge-action connection is essential to SSI’s mission, and the collaboration between community stakeholders and researchers is crucial to maintaining that connection. SSI is a relatively new effort; stay tuned to the SSI website to follow how this collaborative action research initiative develops.

Anyone interested in social change can benefit from having some understanding of social scientific research methods. The knowledge you’ve gained from your methods course can be put to good use even if you don’t have an interest in pursuing a career in research. As a member of a community, perhaps you will find that the opportunity to engage in action research presents itself to you one day. Your background in research methodology will no doubt assist you in making life better for yourself and those who share your interests, circumstances, or geographic region.

Key Takeaways

- Action research is conducted by researchers who wish to create some form of social change.

- Stakeholders are true collaborators in action research.

- Action research is often conducted by teams of interdisciplinary researchers.

- Action research- research that is conducted for the purpose of creating some form of social change in collaboration with stakeholders

Image attributions

protest by BruceEmmerling CC-0

- Esterberg, K. G. (2002). Qualitative methods in social research . Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. ↵

- Adelman, C. (1993). Kurt Lewin and the origins of action research. Educational Action Research, 1, 7-24.; Reason, P. (1994). Participation in human inquiry . London, UK: Sage. ↵

- Healy, K. (2001). Participatory action research and social work: A critical appraisal. International Social Work, 44 , 93-105. ↵

- Piercy, F. P., Franz, N., Donaldson, J. L., & Richard, R. F. (2011). Consistency and change in participatory action research: Reflections on a focus group study about how farmers learn. The Qualitative Report, 16, 820–829. ↵

- CURL. (n.d.) Mission . Retrieved from: https://www.luc.edu/curl/Mission.shtml ↵

- Jones, S. M. (2008, May 13). Cities may mute effect of Wal-Mart. Chicago Tribune . ↵

- Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions. (n.d.) Sustainability solutions initiative . Retrieved from: https://umaine.edu/mitchellcenter/sustainability-solutions-initiative/ ↵

Methodological Choice and Design pp 57–69 Cite as

Action Research in Education and Social Work

- Susan Groundwater-Smith 4 &

- Jude Irwin 4

- First Online: 24 October 2010

3590 Accesses

4 Citations

Part of the book series: Methodos Series ((METH,volume 9))

This chapter discusses action research as it is practised and understood in education and social work. It argues that the major purpose of action research is practical, leading to the development and improvement of practice. It is participative and inclusive of practitioners and consequential stakeholders. The authors address the use of evidence forensically, that is that it informs the understanding of particular phenomena, rather than adversarially, where the pressure is to prove one treatment may be better than another. The authors argue that action research can make a powerful contribution to professional knowledge building. They claim that, while formal knowledge may be seen at one end of the continuum, action research is concerned with practical knowledge underwriting the moral disposition to act wisely, truly and justly at the other. A task for the academy is to assist in the building and understanding of that continuum.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Carlson, B. E., McNutt, L. A., Choi, D. Y., & Rose, I. M. (2002). Intimate partner abuse and mental health. Violence Against Women, 8 (6), 720–745.

Article Google Scholar

Carr, W. (2006). Philosophy, methodology and action research. Journal of Philosophy of Education , 40 (4), 421–435.

Carr, W. (2007). Educational research as a practical science. International Journal of Research and Method in Education , 30 (3), 271–286.

Carr, W. (2009). Practice without theory. In B. Green (Ed.), Understanding and researching professional practice (pp. 55–64). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Google Scholar

Cartwright, N. (1999). The dappled world: A study of the boundaries of science . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Castells, M. (2001). Local and global: Cities in the network society. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie , 93 (5), 548–558.

Elliott, J. (1991). Action research for educational change . Buckingham: Open University Press.

Eraut, M. (1994). Developing professional knowledge and competence . London: Falmer Press.

Eraut, M., & Hirsh, W. (2007). The significance of workplace learning for individuals, groups and organisations . Oxford: Cardiff Universities, ESRC Centre on Skills, Knowledge and Organisational Performance.

Fook, J. (2002). Social work: Critical theory and practice . London: Sage.

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science in research in contemporary societies . London: Sage.

Green, H., & Hannon, C. (2006). Their space. Education for a digital foundation . London: DEMOS Foundation.

Griffiths, M. (2009). Action research for/as/mindful of social justice. In S. Noffke & B. Somekh (Eds.), The Sage handbook of educational action research (pp. 85–98). London: Sage.

Groundwater-Smith, S. (1998). Putting teacher professional judgement to work. Educational Action Research , 6 (1), 21–37.

Groundwater-Smith, S., & Mockler, N. (2006). Research that counts: practitioner research and the academy. In J. Blackmore, J. Wright, & V. Harwood (Eds.), Review of Australian Research in Education, RARE , 6 , 105–118.

Groundwater-Smith, S., & Mockler, N. (2009). Teacher professional learning in an age of compliance: Mind the gap. Rotterdam: Springer.

Gustaven, B. (2001). Theory and practice: The mediating discourse. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of Action Research: Participation, Enquiry and Practice (pp. 17–26). London: Sage Publications.

Hargreaves, D. (1999). The knowledge creating school. British Journal of Educational Studies , 47 (2), 122–144.

Higgs, J., McAllister, L., & Whiteford, G. (2009). The practice and praxis of professional decision making. In B. Green (Ed.), Understanding and researching professional practice (pp. 101–120). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Humphreys, C., & Thiara, R. (2003). Mental health and domestic violence: ‘I call it symptoms of abuse’. British Journal of Social Work , 33 , 209–226.

Kemmis, S. (2008). Practice and practice architectures in mathematics education. Keynote address to the 31st Annual Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia (MERGA) Conference . University of Queensland, Brisbane, June 28–July 1.

Lash, S. (2003). Reflexivity as non-linearity. Theory, Culture and Society , 20 (2), 49–57.

Newman, M. (2006). Teaching Defiance: Stories and Strategies for Activist Educators . San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Nowotny, H., Scott, P., & Gibbons, H. (2003). Mode 2 revisited: The new production of knowledge. Minerva , 41 , 179–194.

Ozga, J. (2007). Co-production of quality in the Applied Education Research Scheme. Research Papers in Education, Policy and Practice , 22 (2), 169–182.

Percy-Smith, B. (2007). ‘You think you know? … You have no idea’: Youth participation in health policy development. Health Education Research , 22 (6), 879–894.

Peschard, I. (2007). Participation of the public in science: Towards a new kind of scientific practice. Human Affairs , 17 , 138–153.

Polanyi, M. (1958). Personal knowledge: Towards a post-critical philosophy . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2001). Handbook of action research: Participation, enquiry and practice . London: Sage

Saltmarsh, S. (2009). Researching context as ‘practiced place’. In B. Green (Ed.), Understanding and researching professional practice (pp. 154–164). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2002). Finding the findings in qualitative studies. Journal of Nursing Scholarship , 34 (3), 213–220.

Schatzki, T. (2002). The site of the social . University Park, PA: Penn State Press.

Stake, R. (2004). Standards based and responsive evaluation . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Stenhouse, L. (1975). An introduction to curriculum research and development . London: Heineman Educational Books Ltd.

Stenhouse, L. (1979). Research as a basis for teaching. Inaugural Lecture . University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK.

Stenhouse, L. (1983). Authority, education and emancipation . London: Heinemann Educational Books.

Stringer, E. (2007). Action research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education and Social Work, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Susan Groundwater-Smith & Jude Irwin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Susan Groundwater-Smith .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Fac. Education & Social Work, University of Sydney, Sydney, 2006, New South Wales, Australia

Lina Markauskaite

Peter Freebody

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Groundwater-Smith, S., Irwin, J. (2011). Action Research in Education and Social Work . In: Markauskaite, L., Freebody, P., Irwin, J. (eds) Methodological Choice and Design. Methodos Series, vol 9. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8933-5_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8933-5_5

Published : 24 October 2010

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-90-481-8932-8

Online ISBN : 978-90-481-8933-5

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

24 Action Research

- Published: December 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter on action research describes the orchestration of cyclical processes of action and research that mutually inform each other. The conceptual foundations of action research are explained, and a case is made for action research’s utility as a framework for knowledge generation in collaboration with community organizations. Although action research is often conducted using qualitative methods, this chapter makes a case for methodological pluralism. Principles for designing and conducting mixed methods action research are provided, drawing specifically on an example of an ongoing collaboration with a community organizing network working on multiple issues, including immigration and transit.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Introduction to Action Research Social Research for Social Change

- Davydd J. Greenwood - Cornell University, USA

- Morten Levin - Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway

- Description

- Includes a vast amount of updated information: Nine chapters have been significantly updated, including two new chapters that engage readers into the current debates on action research as "tradition" or its own "methodology," and how action research takes shape in the university environment. New textboxes highlight important issues in each chapter and more detailed cases and real-world examples illustrate the practical implications of AR in a variety of settings.

- Incorporates a new structure: New information pertains specifically to issues of techniques, work forms, and research strategies based on the authors’ experiences in using the book in teaching. The book now has 4 parts instead of 3, with an entirely new section on higher education and democracy as a concluding section.

- Emphasizes the skill sets needed to do action research: This book deals with the process of educating action researchers and reviews a number of programs that do this. Specific attention is given to the challenges of writing and intellectual property in AR, and more focus is devoted to both adult and formal education, creating a comprehensive overview of the field that is not found in any other action research book.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

"[This book] is an excellent addition to the bookshelf of any social change researcher. Additionally, it is a first-rate resource for educational researchers within organizations or the community."

Useful for the case supplies offered. The contention that AR is more scientific than other social science research makes it problematic to include this volume as a key text in a course where such approaches are also taught as equally valid approaches.

This is a comprehensive and detailed introduction to Action Research as much as it is a worthy introduction for undergraduates engaging with research for the first time.

The book is a resource book, history and theoretical account all in one, and is written in a detailed yet accessible manner for all levels of undergradute study.

This is a good book on the philosophy but in terms of application, it is less useful. My course is actually organized around a team project in the community. So I went with another book. But put this on reserve for students to use as needed.

Good overview with effective and useful case studies. Perhaps too specialised and US orientated for HNC Sociology.

The examples shown represent interesting cases for use in class work. The diversity of situations depicted gives a complete idea about the heterogeneous scope of action-research concerning the different objects of research and intervention as well as the different social and cultural contexts.

A must if undertaking action research. Chapter on Epistemology is essential reading. Many text avoid or skim over this aspect.

This is an excellent introduction to action research. I use it not only to teach, but also for my own projects.

This book gives a good overview on action research, and can be used by students who choose action researc as their approach in their bachelorproject

This book makes Action Research easy to understand. It not only outlines what Action Research is but also details the history, background and epistemology of research for social change.

- New textboxes highlight important issues in each chapter and connect real practice in action research to what is discussed in the respective chapters.

- Two new chapters: Social Science Research Methodology and Action Research, dealing with the debate of AR as an integrated approach, or AR as its own methodology; and Action Research as University Reform.

- Completely updated references and suggested further readings.

- Many more detailed case studies and real-world examples to illustrate the practical implications of this approach in a variety of settings.

- Entirely new section on higher education and democracy.

Sample Materials & Chapters

Chapter 1- Introduction to Action Research, Diversity, and Democracy

Chapter 6 - Social Science Research Techniques, Work Forms, and Research Strateg

Chapter 8 - The Friendly Outsider

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

75 15.3 Action research

Learning objectives.

- Define and provide at least one example of action research

- Describe the role of stakeholders in action research

Action research is defined as research that is conducted for the purpose of creating social change. When conducting action research, scholars collaborate with community stakeholders at all stages of the research process with the aim of producing results that will be usable in the community and by scientists. We defined stakeholders in Chapter 8, as individuals or groups who have an interest in the outcome of your study. Social workers who engage in action research never just go it alone; instead, they collaborate with the people who are affected by the research at each stage in the process. Stakeholders, particularly those with the least power, should be consulted on the purpose of the research project, research questions, design, and reporting of results.

Action research also distinguishes itself from other research in that its purpose is to create change on an individual and community level. Kristin Esterberg puts it quite eloquently when she says, “At heart, all action researchers are concerned that research not simply contribute to knowledge but also lead to positive changes in people’s lives” (2002, p. 137). [1] As you might imagine, action research is consistent with the assumptions of the critical paradigm, which focuses on liberating people from oppressive structures. Action research has multiple origins across the globe, including Kurt Lewin’s psychological experiments in the US and Paulo Friere’s literacy and education programs (Adelman, 1993; Reason, 1994). [2] Over the years, action research has become increasingly popular among scholars who wish for their work to have tangible outcomes that benefit the groups they study.

Action research does not bring any new methodological tricks or terms, but it uses the processes of science in a different way than traditional research. What topics are important to study in a neighborhood or with a target population? A traditional scientist might look at the literature or use their practice wisdom to formulate a question for quantitative or qualitative research. An action researcher, on the other hand, would consult with the target population itself to see what they thought the most pressing issues are and their proposed solutions. In this way, action research flips traditional research on its head. Scientists are more like consultants who provide the tools and resources necessary for a target population to achieve their goals and address social problems.

According to Healy (2001), [3] the assumptions of participatory-action research are that (a) oppression is caused by macro-level structures such as patriarchy and capitalism; (b) research should expose and confront the powerful; (c) researcher and participant relationships should be equal, with equitable distribution of research tasks and roles; and (d) research should result in consciousness-raising and collective action. Coherent with social work values, action research supports the self-determination of oppressed groups and privileges their voice and understanding through the conceptualization, design, data collection, data analysis, and dissemination processes of research.

There are many excellent examples of action research. Some of them focus solely on arriving at useful outcomes for the communities upon which and with whom research is conducted. Other action research projects result in some new knowledge that has a practical application and purpose in addition to the creation of knowledge for basic scientific purposes.

One example of action research can be seen in Fred Piercy and colleagues’ (Piercy, Franz, Donaldson, & Richard, 2011) [4] work with farmers in Virginia, Tennessee, and Louisiana. Together with farmers in these states, the researchers conducted focus groups to understand how farmers learn new information about farming. Ultimately, the aim of this study was to “develop more meaningful ways to communicate information to farmers about sustainable agriculture” (p. 820). This improved communication, the researchers and farmers believed, would benefit not just researchers interested in the topic but also farmers and their communities. Farmers and researchers were both involved in all aspects of the research, from designing the project and determining focus group questions to conducting the focus groups and finally to analyzing data and disseminating findings.

Many additional examples of action research can be found at Loyola University Chicago’s Center for Urban Research and Learning (CURL; http://www.luc.edu/curl/index.shtml ). The mission of the center is to create “innovative solutions that promote equity and opportunity in communities throughout the Chicago metropolitan region” (CURL, n.d., para. 1). [5] For example, in 2006 researchers at CURL embarked on a project to assess the impact on small, local retailers of new Walmart stores entering urban areas (Jones, 2008). [6] The study found that while the effect of Walmart on local retailers seems to have a larger impact in rural areas, Chicago-area local retailers did not experience as dramatic an impact. Nevertheless a “small but statistically significant relationship” was found between Walmart’s arrival in the city and local retailers’ closing their doors (Jones, 2008, para. 3). This and other research conducted by CURL aims to raise awareness about and promote positive social change around issues affecting the lives of people in the Chicago area. CURL meets this aim by collaborating with members of the community to shape a research agenda, collect and analyze data, and disseminate results.

Perhaps one of the most unique and rewarding aspects of engaging in action research is that it is often interdisciplinary. Action research projects might bring together researchers from any number of disciplines, from the social sciences, such as sociology, political science, and psychology; to an assortment of physical and natural sciences, such as biology and chemistry; to engineering, philosophy, and history (to name just a few). One recent example of this kind of interdisciplinary action research can be seen in the University of Maine’s Sustainability Solutions Initiative (SSI) ( https://umaine.edu/mitchellcenter/sustainability-solutions-initiative/ ). This initiative unites researchers from across campus together with local community members to “connect knowledge with action in ways that promote strong economies, vibrant communities, and healthy ecosystems in and beyond Maine” (Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions, para. 1). [7] The knowledge-action connection is essential to SSI’s mission, and the collaboration between community stakeholders and researchers is crucial to maintaining that connection. SSI is a relatively new effort; stay tuned to the SSI website to follow how this collaborative action research initiative develops.

Anyone interested in social change can benefit from having some understanding of social scientific research methods. The knowledge you’ve gained from your methods course can be put to good use even if you don’t have an interest in pursuing a career in research. As a member of a community, perhaps you will find that the opportunity to engage in action research presents itself to you one day. Your background in research methodology will no doubt assist you in making life better for yourself and those who share your interests, circumstances, or geographic region.

Key Takeaways

- Action research is conducted by researchers who wish to create some form of social change.

- Stakeholders are true collaborators in action research.

- Action research is often conducted by teams of interdisciplinary researchers.

- Action research- research that is conducted for the purpose of creating some form of social change in collaboration with stakeholders

Image attributions

protest by BruceEmmerling CC-0

- Esterberg, K. G. (2002). Qualitative methods in social research . Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. ↵

- Adelman, C. (1993). Kurt Lewin and the origins of action research. Educational Action Research, 1, 7-24.; Reason, P. (1994). Participation in human inquiry . London, UK: Sage. ↵

- Healy, K. (2001). Participatory action research and social work: A critical appraisal. International Social Work, 44 , 93-105. ↵

- Piercy, F. P., Franz, N., Donaldson, J. L., & Richard, R. F. (2011). Consistency and change in participatory action research: Reflections on a focus group study about how farmers learn. The Qualitative Report, 16, 820–829. ↵

- CURL. (n.d.) Mission . Retrieved from: https://www.luc.edu/curl/Mission.shtml ↵

- Jones, S. M. (2008, May 13). Cities may mute effect of Wal-Mart. Chicago Tribune . ↵

- Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions. (n.d.) Sustainability solutions initiative . Retrieved from: https://umaine.edu/mitchellcenter/sustainability-solutions-initiative/ ↵

Scientific Inquiry in Social Work Copyright © 2018 by Matthew DeCarlo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Social Work Research Methods That Drive the Practice

Social workers advocate for the well-being of individuals, families and communities. But how do social workers know what interventions are needed to help an individual? How do they assess whether a treatment plan is working? What do social workers use to write evidence-based policy?

Social work involves research-informed practice and practice-informed research. At every level, social workers need to know objective facts about the populations they serve, the efficacy of their interventions and the likelihood that their policies will improve lives. A variety of social work research methods make that possible.

Data-Driven Work

Data is a collection of facts used for reference and analysis. In a field as broad as social work, data comes in many forms.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative

As with any research, social work research involves both quantitative and qualitative studies.

Quantitative Research

Answers to questions like these can help social workers know about the populations they serve — or hope to serve in the future.

- How many students currently receive reduced-price school lunches in the local school district?

- How many hours per week does a specific individual consume digital media?

- How frequently did community members access a specific medical service last year?

Quantitative data — facts that can be measured and expressed numerically — are crucial for social work.

Quantitative research has advantages for social scientists. Such research can be more generalizable to large populations, as it uses specific sampling methods and lends itself to large datasets. It can provide important descriptive statistics about a specific population. Furthermore, by operationalizing variables, it can help social workers easily compare similar datasets with one another.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative data — facts that cannot be measured or expressed in terms of mere numbers or counts — offer rich insights into individuals, groups and societies. It can be collected via interviews and observations.

- What attitudes do students have toward the reduced-price school lunch program?

- What strategies do individuals use to moderate their weekly digital media consumption?

- What factors made community members more or less likely to access a specific medical service last year?

Qualitative research can thereby provide a textured view of social contexts and systems that may not have been possible with quantitative methods. Plus, it may even suggest new lines of inquiry for social work research.

Mixed Methods Research

Combining quantitative and qualitative methods into a single study is known as mixed methods research. This form of research has gained popularity in the study of social sciences, according to a 2019 report in the academic journal Theory and Society. Since quantitative and qualitative methods answer different questions, merging them into a single study can balance the limitations of each and potentially produce more in-depth findings.

However, mixed methods research is not without its drawbacks. Combining research methods increases the complexity of a study and generally requires a higher level of expertise to collect, analyze and interpret the data. It also requires a greater level of effort, time and often money.

The Importance of Research Design

Data-driven practice plays an essential role in social work. Unlike philanthropists and altruistic volunteers, social workers are obligated to operate from a scientific knowledge base.

To know whether their programs are effective, social workers must conduct research to determine results, aggregate those results into comprehensible data, analyze and interpret their findings, and use evidence to justify next steps.

Employing the proper design ensures that any evidence obtained during research enables social workers to reliably answer their research questions.

Research Methods in Social Work

The various social work research methods have specific benefits and limitations determined by context. Common research methods include surveys, program evaluations, needs assessments, randomized controlled trials, descriptive studies and single-system designs.

Surveys involve a hypothesis and a series of questions in order to test that hypothesis. Social work researchers will send out a survey, receive responses, aggregate the results, analyze the data, and form conclusions based on trends.

Surveys are one of the most common research methods social workers use — and for good reason. They tend to be relatively simple and are usually affordable. However, surveys generally require large participant groups, and self-reports from survey respondents are not always reliable.

Program Evaluations

Social workers ally with all sorts of programs: after-school programs, government initiatives, nonprofit projects and private programs, for example.

Crucially, social workers must evaluate a program’s effectiveness in order to determine whether the program is meeting its goals and what improvements can be made to better serve the program’s target population.

Evidence-based programming helps everyone save money and time, and comparing programs with one another can help social workers make decisions about how to structure new initiatives. Evaluating programs becomes complicated, however, when programs have multiple goal metrics, some of which may be vague or difficult to assess (e.g., “we aim to promote the well-being of our community”).

Needs Assessments

Social workers use needs assessments to identify services and necessities that a population lacks access to.

Common social work populations that researchers may perform needs assessments on include:

- People in a specific income group

- Everyone in a specific geographic region

- A specific ethnic group

- People in a specific age group

In the field, a social worker may use a combination of methods (e.g., surveys and descriptive studies) to learn more about a specific population or program. Social workers look for gaps between the actual context and a population’s or individual’s “wants” or desires.

For example, a social worker could conduct a needs assessment with an individual with cancer trying to navigate the complex medical-industrial system. The social worker may ask the client questions about the number of hours they spend scheduling doctor’s appointments, commuting and managing their many medications. After learning more about the specific client needs, the social worker can identify opportunities for improvements in an updated care plan.

In policy and program development, social workers conduct needs assessments to determine where and how to effect change on a much larger scale. Integral to social work at all levels, needs assessments reveal crucial information about a population’s needs to researchers, policymakers and other stakeholders. Needs assessments may fall short, however, in revealing the root causes of those needs (e.g., structural racism).

Randomized Controlled Trials

Randomized controlled trials are studies in which a randomly selected group is subjected to a variable (e.g., a specific stimulus or treatment) and a control group is not. Social workers then measure and compare the results of the randomized group with the control group in order to glean insights about the effectiveness of a particular intervention or treatment.

Randomized controlled trials are easily reproducible and highly measurable. They’re useful when results are easily quantifiable. However, this method is less helpful when results are not easily quantifiable (i.e., when rich data such as narratives and on-the-ground observations are needed).

Descriptive Studies

Descriptive studies immerse the researcher in another context or culture to study specific participant practices or ways of living. Descriptive studies, including descriptive ethnographic studies, may overlap with and include other research methods:

- Informant interviews

- Census data

- Observation

By using descriptive studies, researchers may glean a richer, deeper understanding of a nuanced culture or group on-site. The main limitations of this research method are that it tends to be time-consuming and expensive.

Single-System Designs

Unlike most medical studies, which involve testing a drug or treatment on two groups — an experimental group that receives the drug/treatment and a control group that does not — single-system designs allow researchers to study just one group (e.g., an individual or family).

Single-system designs typically entail studying a single group over a long period of time and may involve assessing the group’s response to multiple variables.

For example, consider a study on how media consumption affects a person’s mood. One way to test a hypothesis that consuming media correlates with low mood would be to observe two groups: a control group (no media) and an experimental group (two hours of media per day). When employing a single-system design, however, researchers would observe a single participant as they watch two hours of media per day for one week and then four hours per day of media the next week.

These designs allow researchers to test multiple variables over a longer period of time. However, similar to descriptive studies, single-system designs can be fairly time-consuming and costly.

Learn More About Social Work Research Methods

Social workers have the opportunity to improve the social environment by advocating for the vulnerable — including children, older adults and people with disabilities — and facilitating and developing resources and programs.

Learn more about how you can earn your Master of Social Work online at Virginia Commonwealth University . The highest-ranking school of social work in Virginia, VCU has a wide range of courses online. That means students can earn their degrees with the flexibility of learning at home. Learn more about how you can take your career in social work further with VCU.

From M.S.W. to LCSW: Understanding Your Career Path as a Social Worker

How Palliative Care Social Workers Support Patients With Terminal Illnesses

How to Become a Social Worker in Health Care

Gov.uk, Mixed Methods Study

MVS Open Press, Foundations of Social Work Research

Open Social Work Education, Scientific Inquiry in Social Work

Open Social Work, Graduate Research Methods in Social Work: A Project-Based Approach

Routledge, Research for Social Workers: An Introduction to Methods

SAGE Publications, Research Methods for Social Work: A Problem-Based Approach

Theory and Society, Mixed Methods Research: What It Is and What It Could Be

READY TO GET STARTED WITH OUR ONLINE M.S.W. PROGRAM FORMAT?

Bachelor’s degree is required.

21 Action Research Examples (In Education)

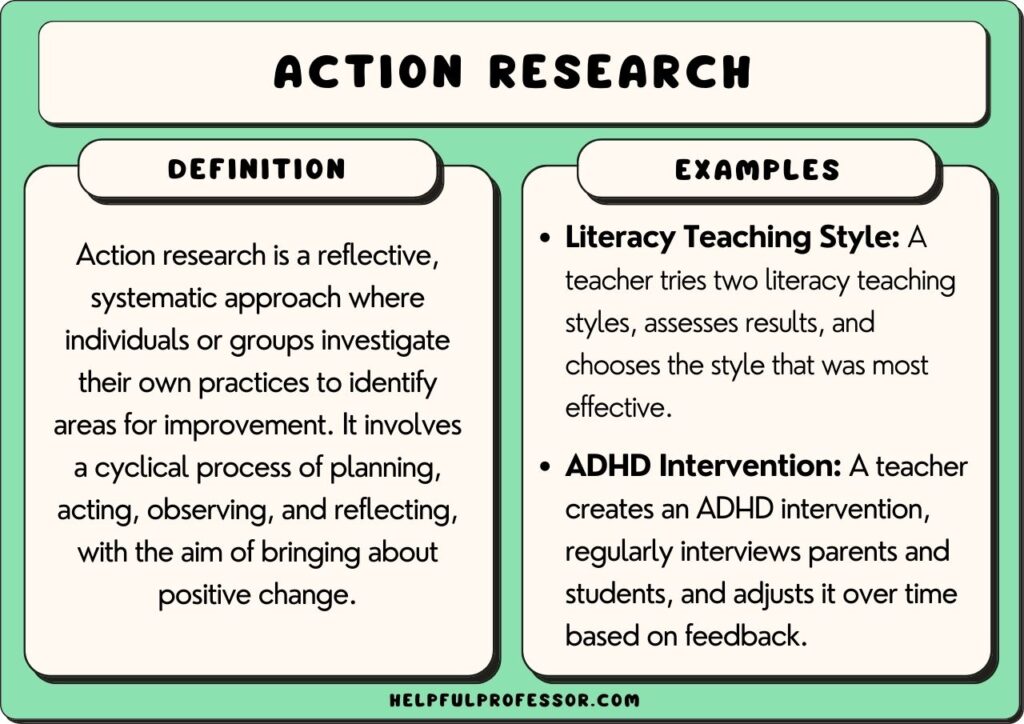

Action research is an example of qualitative research . It refers to a wide range of evaluative or investigative methods designed to analyze professional practices and take action for improvement.

Commonly used in education, those practices could be related to instructional methods, classroom practices, or school organizational matters.

The creation of action research is attributed to Kurt Lewin , a German-American psychologist also considered to be the father of social psychology.

Gillis and Jackson (2002) offer a very concise definition of action research: “systematic collection and analysis of data for the purpose of taking action and making change” (p.264).

The methods of action research in education include:

- conducting in-class observations

- taking field notes

- surveying or interviewing teachers, administrators, or parents

- using audio and video recordings.

The goal is to identify problematic issues, test possible solutions, or simply carry-out continuous improvement.

There are several steps in action research : identify a problem, design a plan to resolve, implement the plan, evaluate effectiveness, reflect on results, make necessary adjustment and repeat the process.

Action Research Examples

- Digital literacy assessment and training: The school’s IT department conducts a survey on students’ digital literacy skills. Based on the results, a tailored training program is designed for different age groups.

- Library resources utilization study: The school librarian tracks the frequency and type of books checked out by students. The data is then used to curate a more relevant collection and organize reading programs.

- Extracurricular activities and student well-being: A team of teachers and counselors assess the impact of extracurricular activities on student mental health through surveys and interviews. Adjustments are made based on findings.

- Parent-teacher communication channels: The school evaluates the effectiveness of current communication tools (e.g., newsletters, apps) between teachers and parents. Feedback is used to implement a more streamlined system.

- Homework load evaluation: Teachers across grade levels assess the amount and effectiveness of homework given. Adjustments are made to ensure a balance between academic rigor and student well-being.

- Classroom environment and learning: A group of teachers collaborates to study the impact of classroom layouts and decorations on student engagement and comprehension. Changes are made based on the findings.

- Student feedback on curriculum content: High school students are surveyed about the relevance and applicability of their current curriculum. The feedback is then used to make necessary curriculum adjustments.

- Teacher mentoring and support: New teachers are paired with experienced mentors. Both parties provide feedback on the effectiveness of the mentoring program, leading to continuous improvements.

- Assessment of school transportation: The school board evaluates the efficiency and safety of school buses through surveys with students and parents. Necessary changes are implemented based on the results.

- Cultural sensitivity training: After conducting a survey on students’ cultural backgrounds and experiences, the school organizes workshops for teachers to promote a more inclusive classroom environment.

- Environmental initiatives and student involvement: The school’s eco-club assesses the school’s carbon footprint and waste management. They then collaborate with the administration to implement greener practices and raise environmental awareness.

- Working with parents through research: A school’s admin staff conduct focus group sessions with parents to identify top concerns.Those concerns will then be addressed and another session conducted at the end of the school year.

- Peer teaching observations and improvements: Kindergarten teachers observe other teachers handling class transition techniques to share best practices.

- PTA surveys and resultant action: The PTA of a district conducts a survey of members regarding their satisfaction with remote learning classes.The results will be presented to the school board for further action.

- Recording and reflecting: A school administrator takes video recordings of playground behavior and then plays them for the teachers. The teachers work together to formulate a list of 10 playground safety guidelines.

- Pre/post testing of interventions: A school board conducts a district wide evaluation of a STEM program by conducting a pre/post-test of students’ skills in computer programming.

- Focus groups of practitioners : The professional development needs of teachers are determined from structured focus group sessions with teachers and admin.

- School lunch research and intervention: A nutrition expert is hired to evaluate and improve the quality of school lunches.

- School nurse systematic checklist and improvements: The school nurse implements a bathroom cleaning checklist to monitor cleanliness after the results of a recent teacher survey revealed several issues.

- Wearable technologies for pedagogical improvements; Students wear accelerometers attached to their hips to gain a baseline measure of physical activity.The results will identify if any issues exist.

- School counselor reflective practice : The school counselor conducts a student survey on antisocial behavior and then plans a series of workshops for both teachers and parents.

Detailed Examples

1. cooperation and leadership.

A science teacher has noticed that her 9 th grade students do not cooperate with each other when doing group projects. There is a lot of arguing and battles over whose ideas will be followed.