- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.1: The Working Hypothesis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 33319

- Penn State's Department of Statistics

- The Pennsylvania State University

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

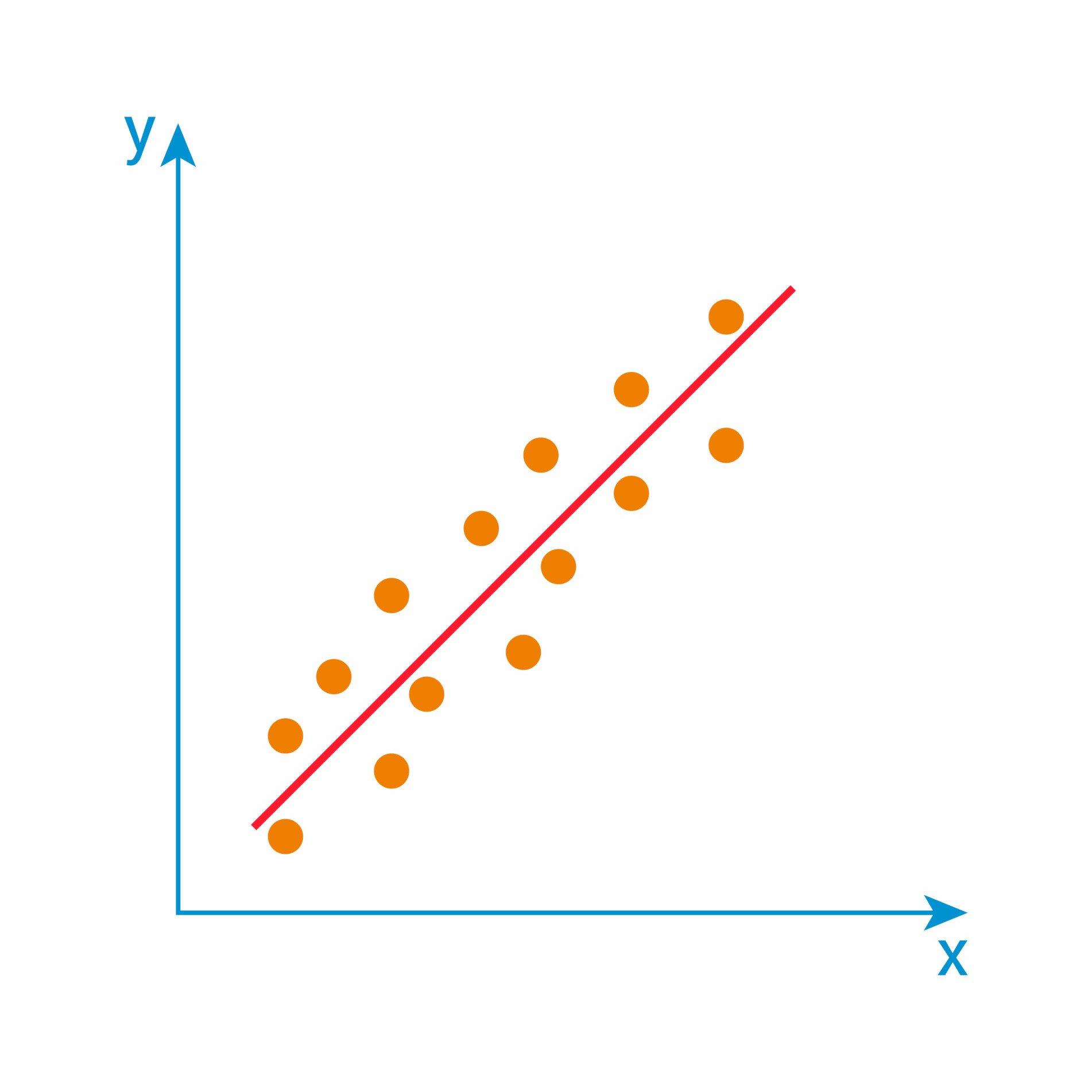

Using the scientific method, before any statistical analysis can be conducted, a researcher must generate a guess, or hypothesis about what is going on. The process begins with a Working Hypothesis . This is a direct statement of the research idea. For example, a plant biologist may think that plant height may be affected by applying different fertilizers. So they might say: " Plants with different fertilizers will grow to different heights ".

But according to the Popperian Principle of Falsification, we can't conclusively affirm a hypothesis, but we can conclusively negate a hypothesis. So we need to translate the working hypothesis into a framework wherein we state a null hypothesis that the average height (or mean height) for plants with the different fertilizers will all be the same. The alternative hypothesis (which the biologist hopes to show) is that they are not all equal, but rather some of the fertilizer treatments have produced plants with different mean heights. The strength of the data will determine whether the null hypothesis can be rejected with a specified level of confidence.

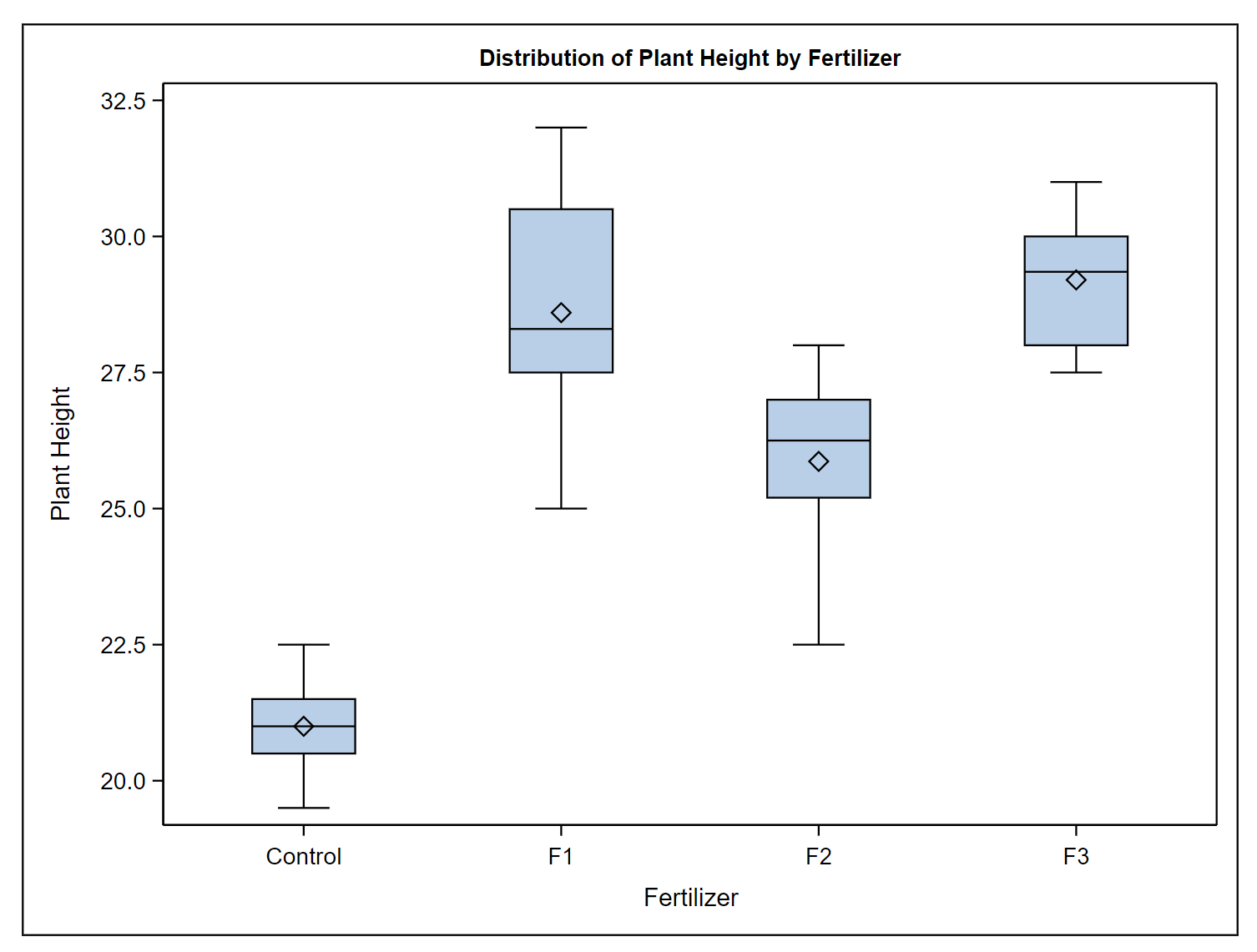

Pictured in the graph below, we can imagine testing three kinds of fertilizer and also one group of plants that are untreated (the control). The plant biologist kept all the plants under controlled conditions in the greenhouse, to focus on the effect of the fertilizer, the only thing we know to differ among the plants. At the end of the experiment, the biologist measured the height of each plant. Plant height is the dependent or response variable and is plotted on the vertical (\(y\)) axis. The biologist used a simple boxplot to plot the difference in the heights.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=554&height=419)

This boxplot is a customary way to show treatment (or factor) level differences. In this case, there was only one treatment: fertilizer. The fertilizer treatment had four levels that included the control, which received no fertilizer. Using this language convention is important because later on we will be using ANOVA to handle multi-factor studies (for example if the biologist manipulated the amount of water AND the type of fertilizer) and we will need to be able to refer to different treatments, each with their own set of levels.

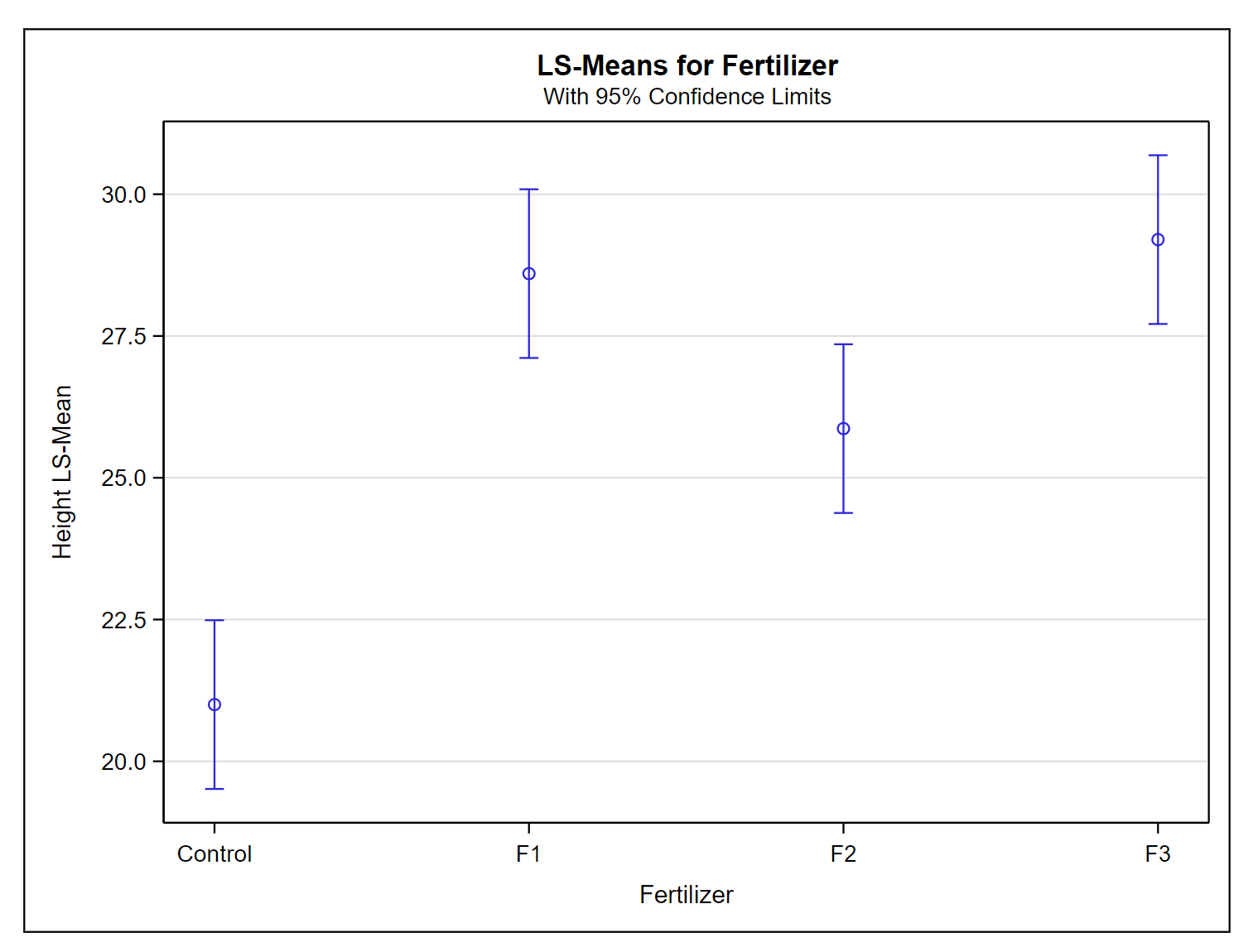

Another alternative for viewing the differences in the heights is with a means plot (a scatter or interval plot):

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=553&height=420)

This second method to plot the difference in the means of the treatments provides essentially the same information. However, this plot illustrates the variability in the data with 'error bars' that are the 95% confidence interval limits around the means.

In between the statement of a Working Hypothesis and the creation of the 95% confidence intervals used to create this means plot is a 7-step process of statistical hypothesis testing, presented in the following section.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

- Manuscript Preparation

What is and How to Write a Good Hypothesis in Research?

- 4 minute read

Table of Contents

One of the most important aspects of conducting research is constructing a strong hypothesis. But what makes a hypothesis in research effective? In this article, we’ll look at the difference between a hypothesis and a research question, as well as the elements of a good hypothesis in research. We’ll also include some examples of effective hypotheses, and what pitfalls to avoid.

What is a Hypothesis in Research?

Simply put, a hypothesis is a research question that also includes the predicted or expected result of the research. Without a hypothesis, there can be no basis for a scientific or research experiment. As such, it is critical that you carefully construct your hypothesis by being deliberate and thorough, even before you set pen to paper. Unless your hypothesis is clearly and carefully constructed, any flaw can have an adverse, and even grave, effect on the quality of your experiment and its subsequent results.

Research Question vs Hypothesis

It’s easy to confuse research questions with hypotheses, and vice versa. While they’re both critical to the Scientific Method, they have very specific differences. Primarily, a research question, just like a hypothesis, is focused and concise. But a hypothesis includes a prediction based on the proposed research, and is designed to forecast the relationship of and between two (or more) variables. Research questions are open-ended, and invite debate and discussion, while hypotheses are closed, e.g. “The relationship between A and B will be C.”

A hypothesis is generally used if your research topic is fairly well established, and you are relatively certain about the relationship between the variables that will be presented in your research. Since a hypothesis is ideally suited for experimental studies, it will, by its very existence, affect the design of your experiment. The research question is typically used for new topics that have not yet been researched extensively. Here, the relationship between different variables is less known. There is no prediction made, but there may be variables explored. The research question can be casual in nature, simply trying to understand if a relationship even exists, descriptive or comparative.

How to Write Hypothesis in Research

Writing an effective hypothesis starts before you even begin to type. Like any task, preparation is key, so you start first by conducting research yourself, and reading all you can about the topic that you plan to research. From there, you’ll gain the knowledge you need to understand where your focus within the topic will lie.

Remember that a hypothesis is a prediction of the relationship that exists between two or more variables. Your job is to write a hypothesis, and design the research, to “prove” whether or not your prediction is correct. A common pitfall is to use judgments that are subjective and inappropriate for the construction of a hypothesis. It’s important to keep the focus and language of your hypothesis objective.

An effective hypothesis in research is clearly and concisely written, and any terms or definitions clarified and defined. Specific language must also be used to avoid any generalities or assumptions.

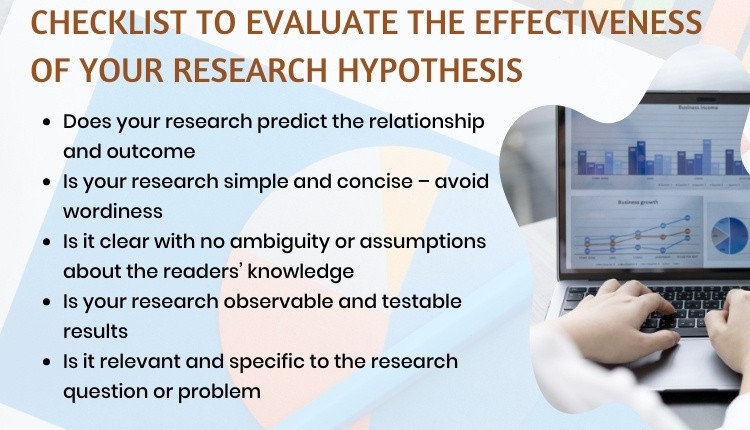

Use the following points as a checklist to evaluate the effectiveness of your research hypothesis:

- Predicts the relationship and outcome

- Simple and concise – avoid wordiness

- Clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Observable and testable results

- Relevant and specific to the research question or problem

Research Hypothesis Example

Perhaps the best way to evaluate whether or not your hypothesis is effective is to compare it to those of your colleagues in the field. There is no need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to writing a powerful research hypothesis. As you’re reading and preparing your hypothesis, you’ll also read other hypotheses. These can help guide you on what works, and what doesn’t, when it comes to writing a strong research hypothesis.

Here are a few generic examples to get you started.

Eating an apple each day, after the age of 60, will result in a reduction of frequency of physician visits.

Budget airlines are more likely to receive more customer complaints. A budget airline is defined as an airline that offers lower fares and fewer amenities than a traditional full-service airline. (Note that the term “budget airline” is included in the hypothesis.

Workplaces that offer flexible working hours report higher levels of employee job satisfaction than workplaces with fixed hours.

Each of the above examples are specific, observable and measurable, and the statement of prediction can be verified or shown to be false by utilizing standard experimental practices. It should be noted, however, that often your hypothesis will change as your research progresses.

Language Editing Plus

Elsevier’s Language Editing Plus service can help ensure that your research hypothesis is well-designed, and articulates your research and conclusions. Our most comprehensive editing package, you can count on a thorough language review by native-English speakers who are PhDs or PhD candidates. We’ll check for effective logic and flow of your manuscript, as well as document formatting for your chosen journal, reference checks, and much more.

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

What is a Problem Statement? [with examples]

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Research Hypothesis In Psychology: Types, & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A research hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its outset. It is a key component of the scientific method .

Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding

Some key points about hypotheses:

- A hypothesis expresses an expected pattern or relationship. It connects the variables under investigation.

- It is stated in clear, precise terms before any data collection or analysis occurs. This makes the hypothesis testable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. It should be possible, even if unlikely in practice, to collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis.

- Hypotheses guide research. Scientists design studies to explicitly evaluate hypotheses about how nature works.

- For a hypothesis to be valid, it must be testable against empirical evidence. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

- Hypotheses are informed by background knowledge and observation, but go beyond what is already known to propose an explanation of how or why something occurs.

Predictions typically arise from a thorough knowledge of the research literature, curiosity about real-world problems or implications, and integrating this to advance theory. They build on existing literature while providing new insight.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Alternative hypothesis.

The research hypothesis is often called the alternative or experimental hypothesis in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the dependent variable, which is measured based on those changes.

The alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable affects the other).

A hypothesis is a testable statement or prediction about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a key component of the scientific method. Some key points about hypotheses:

- Important hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested empirically. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

In summary, a hypothesis is a precise, testable statement of what researchers expect to happen in a study and why. Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding.

An experimental hypothesis predicts what change(s) will occur in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated.

It states that the results are not due to chance and are significant in supporting the theory being investigated.

The alternative hypothesis can be directional, indicating a specific direction of the effect, or non-directional, suggesting a difference without specifying its nature. It’s what researchers aim to support or demonstrate through their study.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states no relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable does not affect the other). There will be no changes in the dependent variable due to manipulating the independent variable.

It states results are due to chance and are not significant in supporting the idea being investigated.

The null hypothesis, positing no effect or relationship, is a foundational contrast to the research hypothesis in scientific inquiry. It establishes a baseline for statistical testing, promoting objectivity by initiating research from a neutral stance.

Many statistical methods are tailored to test the null hypothesis, determining the likelihood of observed results if no true effect exists.

This dual-hypothesis approach provides clarity, ensuring that research intentions are explicit, and fosters consistency across scientific studies, enhancing the standardization and interpretability of research outcomes.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

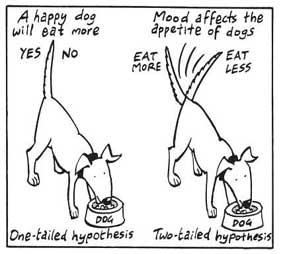

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, predicts that there is a difference or relationship between two variables but does not specify the direction of this relationship.

It merely indicates that a change or effect will occur without predicting which group will have higher or lower values.

For example, “There is a difference in performance between Group A and Group B” is a non-directional hypothesis.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. It predicts in which direction the change will take place. (i.e., greater, smaller, less, more)

It specifies whether one variable is greater, lesser, or different from another, rather than just indicating that there’s a difference without specifying its nature.

For example, “Exercise increases weight loss” is a directional hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The Falsification Principle, proposed by Karl Popper , is a way of demarcating science from non-science. It suggests that for a theory or hypothesis to be considered scientific, it must be testable and irrefutable.

Falsifiability emphasizes that scientific claims shouldn’t just be confirmable but should also have the potential to be proven wrong.

It means that there should exist some potential evidence or experiment that could prove the proposition false.

However many confirming instances exist for a theory, it only takes one counter observation to falsify it. For example, the hypothesis that “all swans are white,” can be falsified by observing a black swan.

For Popper, science should attempt to disprove a theory rather than attempt to continually provide evidence to support a research hypothesis.

Can a Hypothesis be Proven?

Hypotheses make probabilistic predictions. They state the expected outcome if a particular relationship exists. However, a study result supporting a hypothesis does not definitively prove it is true.

All studies have limitations. There may be unknown confounding factors or issues that limit the certainty of conclusions. Additional studies may yield different results.

In science, hypotheses can realistically only be supported with some degree of confidence, not proven. The process of science is to incrementally accumulate evidence for and against hypothesized relationships in an ongoing pursuit of better models and explanations that best fit the empirical data. But hypotheses remain open to revision and rejection if that is where the evidence leads.

- Disproving a hypothesis is definitive. Solid disconfirmatory evidence will falsify a hypothesis and require altering or discarding it based on the evidence.

- However, confirming evidence is always open to revision. Other explanations may account for the same results, and additional or contradictory evidence may emerge over time.

We can never 100% prove the alternative hypothesis. Instead, we see if we can disprove, or reject the null hypothesis.

If we reject the null hypothesis, this doesn’t mean that our alternative hypothesis is correct but does support the alternative/experimental hypothesis.

Upon analysis of the results, an alternative hypothesis can be rejected or supported, but it can never be proven to be correct. We must avoid any reference to results proving a theory as this implies 100% certainty, and there is always a chance that evidence may exist which could refute a theory.

How to Write a Hypothesis

- Identify variables . The researcher manipulates the independent variable and the dependent variable is the measured outcome.

- Operationalized the variables being investigated . Operationalization of a hypothesis refers to the process of making the variables physically measurable or testable, e.g. if you are about to study aggression, you might count the number of punches given by participants.

- Decide on a direction for your prediction . If there is evidence in the literature to support a specific effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis. If there are limited or ambiguous findings in the literature regarding the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

- Make it Testable : Ensure your hypothesis can be tested through experimentation or observation. It should be possible to prove it false (principle of falsifiability).

- Clear & concise language . A strong hypothesis is concise (typically one to two sentences long), and formulated using clear and straightforward language, ensuring it’s easily understood and testable.

Consider a hypothesis many teachers might subscribe to: students work better on Monday morning than on Friday afternoon (IV=Day, DV= Standard of work).

Now, if we decide to study this by giving the same group of students a lesson on a Monday morning and a Friday afternoon and then measuring their immediate recall of the material covered in each session, we would end up with the following:

- The alternative hypothesis states that students will recall significantly more information on a Monday morning than on a Friday afternoon.

- The null hypothesis states that there will be no significant difference in the amount recalled on a Monday morning compared to a Friday afternoon. Any difference will be due to chance or confounding factors.

More Examples

- Memory : Participants exposed to classical music during study sessions will recall more items from a list than those who studied in silence.

- Social Psychology : Individuals who frequently engage in social media use will report higher levels of perceived social isolation compared to those who use it infrequently.

- Developmental Psychology : Children who engage in regular imaginative play have better problem-solving skills than those who don’t.

- Clinical Psychology : Cognitive-behavioral therapy will be more effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety over a 6-month period compared to traditional talk therapy.

- Cognitive Psychology : Individuals who multitask between various electronic devices will have shorter attention spans on focused tasks than those who single-task.

- Health Psychology : Patients who practice mindfulness meditation will experience lower levels of chronic pain compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Organizational Psychology : Employees in open-plan offices will report higher levels of stress than those in private offices.

- Behavioral Psychology : Rats rewarded with food after pressing a lever will press it more frequently than rats who receive no reward.

Related Articles

Research Methodology

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

Convergent Validity: Definition and Examples

What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

16 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Research Hypothesis: Good & Bad Examples

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis is an attempt at explaining a phenomenon or the relationships between phenomena/variables in the real world. Hypotheses are sometimes called “educated guesses”, but they are in fact (or let’s say they should be) based on previous observations, existing theories, scientific evidence, and logic. A research hypothesis is also not a prediction—rather, predictions are ( should be) based on clearly formulated hypotheses. For example, “We tested the hypothesis that KLF2 knockout mice would show deficiencies in heart development” is an assumption or prediction, not a hypothesis.

The research hypothesis at the basis of this prediction is “the product of the KLF2 gene is involved in the development of the cardiovascular system in mice”—and this hypothesis is probably (hopefully) based on a clear observation, such as that mice with low levels of Kruppel-like factor 2 (which KLF2 codes for) seem to have heart problems. From this hypothesis, you can derive the idea that a mouse in which this particular gene does not function cannot develop a normal cardiovascular system, and then make the prediction that we started with.

What is the difference between a hypothesis and a prediction?

You might think that these are very subtle differences, and you will certainly come across many publications that do not contain an actual hypothesis or do not make these distinctions correctly. But considering that the formulation and testing of hypotheses is an integral part of the scientific method, it is good to be aware of the concepts underlying this approach. The two hallmarks of a scientific hypothesis are falsifiability (an evaluation standard that was introduced by the philosopher of science Karl Popper in 1934) and testability —if you cannot use experiments or data to decide whether an idea is true or false, then it is not a hypothesis (or at least a very bad one).

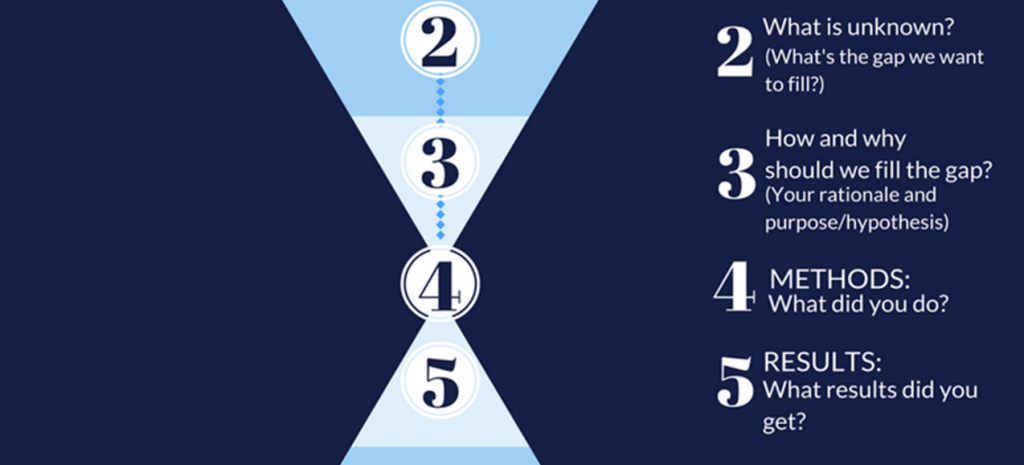

So, in a nutshell, you (1) look at existing evidence/theories, (2) come up with a hypothesis, (3) make a prediction that allows you to (4) design an experiment or data analysis to test it, and (5) come to a conclusion. Of course, not all studies have hypotheses (there is also exploratory or hypothesis-generating research), and you do not necessarily have to state your hypothesis as such in your paper.

But for the sake of understanding the principles of the scientific method, let’s first take a closer look at the different types of hypotheses that research articles refer to and then give you a step-by-step guide for how to formulate a strong hypothesis for your own paper.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Hypotheses can be simple , which means they describe the relationship between one single independent variable (the one you observe variations in or plan to manipulate) and one single dependent variable (the one you expect to be affected by the variations/manipulation). If there are more variables on either side, you are dealing with a complex hypothesis. You can also distinguish hypotheses according to the kind of relationship between the variables you are interested in (e.g., causal or associative ). But apart from these variations, we are usually interested in what is called the “alternative hypothesis” and, in contrast to that, the “null hypothesis”. If you think these two should be listed the other way round, then you are right, logically speaking—the alternative should surely come second. However, since this is the hypothesis we (as researchers) are usually interested in, let’s start from there.

Alternative Hypothesis

If you predict a relationship between two variables in your study, then the research hypothesis that you formulate to describe that relationship is your alternative hypothesis (usually H1 in statistical terms). The goal of your hypothesis testing is thus to demonstrate that there is sufficient evidence that supports the alternative hypothesis, rather than evidence for the possibility that there is no such relationship. The alternative hypothesis is usually the research hypothesis of a study and is based on the literature, previous observations, and widely known theories.

Null Hypothesis

The hypothesis that describes the other possible outcome, that is, that your variables are not related, is the null hypothesis ( H0 ). Based on your findings, you choose between the two hypotheses—usually that means that if your prediction was correct, you reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative. Make sure, however, that you are not getting lost at this step of the thinking process: If your prediction is that there will be no difference or change, then you are trying to find support for the null hypothesis and reject H1.

Directional Hypothesis

While the null hypothesis is obviously “static”, the alternative hypothesis can specify a direction for the observed relationship between variables—for example, that mice with higher expression levels of a certain protein are more active than those with lower levels. This is then called a one-tailed hypothesis.

Another example for a directional one-tailed alternative hypothesis would be that

H1: Attending private classes before important exams has a positive effect on performance.

Your null hypothesis would then be that

H0: Attending private classes before important exams has no/a negative effect on performance.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A nondirectional hypothesis does not specify the direction of the potentially observed effect, only that there is a relationship between the studied variables—this is called a two-tailed hypothesis. For instance, if you are studying a new drug that has shown some effects on pathways involved in a certain condition (e.g., anxiety) in vitro in the lab, but you can’t say for sure whether it will have the same effects in an animal model or maybe induce other/side effects that you can’t predict and potentially increase anxiety levels instead, you could state the two hypotheses like this:

H1: The only lab-tested drug (somehow) affects anxiety levels in an anxiety mouse model.

You then test this nondirectional alternative hypothesis against the null hypothesis:

H0: The only lab-tested drug has no effect on anxiety levels in an anxiety mouse model.

How to Write a Hypothesis for a Research Paper

Now that we understand the important distinctions between different kinds of research hypotheses, let’s look at a simple process of how to write a hypothesis.

Writing a Hypothesis Step:1

Ask a question, based on earlier research. Research always starts with a question, but one that takes into account what is already known about a topic or phenomenon. For example, if you are interested in whether people who have pets are happier than those who don’t, do a literature search and find out what has already been demonstrated. You will probably realize that yes, there is quite a bit of research that shows a relationship between happiness and owning a pet—and even studies that show that owning a dog is more beneficial than owning a cat ! Let’s say you are so intrigued by this finding that you wonder:

What is it that makes dog owners even happier than cat owners?

Let’s move on to Step 2 and find an answer to that question.

Writing a Hypothesis Step 2:

Formulate a strong hypothesis by answering your own question. Again, you don’t want to make things up, take unicorns into account, or repeat/ignore what has already been done. Looking at the dog-vs-cat papers your literature search returned, you see that most studies are based on self-report questionnaires on personality traits, mental health, and life satisfaction. What you don’t find is any data on actual (mental or physical) health measures, and no experiments. You therefore decide to make a bold claim come up with the carefully thought-through hypothesis that it’s maybe the lifestyle of the dog owners, which includes walking their dog several times per day, engaging in fun and healthy activities such as agility competitions, and taking them on trips, that gives them that extra boost in happiness. You could therefore answer your question in the following way:

Dog owners are happier than cat owners because of the dog-related activities they engage in.

Now you have to verify that your hypothesis fulfills the two requirements we introduced at the beginning of this resource article: falsifiability and testability . If it can’t be wrong and can’t be tested, it’s not a hypothesis. We are lucky, however, because yes, we can test whether owning a dog but not engaging in any of those activities leads to lower levels of happiness or well-being than owning a dog and playing and running around with them or taking them on trips.

Writing a Hypothesis Step 3:

Make your predictions and define your variables. We have verified that we can test our hypothesis, but now we have to define all the relevant variables, design our experiment or data analysis, and make precise predictions. You could, for example, decide to study dog owners (not surprising at this point), let them fill in questionnaires about their lifestyle as well as their life satisfaction (as other studies did), and then compare two groups of active and inactive dog owners. Alternatively, if you want to go beyond the data that earlier studies produced and analyzed and directly manipulate the activity level of your dog owners to study the effect of that manipulation, you could invite them to your lab, select groups of participants with similar lifestyles, make them change their lifestyle (e.g., couch potato dog owners start agility classes, very active ones have to refrain from any fun activities for a certain period of time) and assess their happiness levels before and after the intervention. In both cases, your independent variable would be “ level of engagement in fun activities with dog” and your dependent variable would be happiness or well-being .

Examples of a Good and Bad Hypothesis

Let’s look at a few examples of good and bad hypotheses to get you started.

Good Hypothesis Examples

Bad hypothesis examples, tips for writing a research hypothesis.

If you understood the distinction between a hypothesis and a prediction we made at the beginning of this article, then you will have no problem formulating your hypotheses and predictions correctly. To refresh your memory: We have to (1) look at existing evidence, (2) come up with a hypothesis, (3) make a prediction, and (4) design an experiment. For example, you could summarize your dog/happiness study like this:

(1) While research suggests that dog owners are happier than cat owners, there are no reports on what factors drive this difference. (2) We hypothesized that it is the fun activities that many dog owners (but very few cat owners) engage in with their pets that increases their happiness levels. (3) We thus predicted that preventing very active dog owners from engaging in such activities for some time and making very inactive dog owners take up such activities would lead to an increase and decrease in their overall self-ratings of happiness, respectively. (4) To test this, we invited dog owners into our lab, assessed their mental and emotional well-being through questionnaires, and then assigned them to an “active” and an “inactive” group, depending on…

Note that you use “we hypothesize” only for your hypothesis, not for your experimental prediction, and “would” or “if – then” only for your prediction, not your hypothesis. A hypothesis that states that something “would” affect something else sounds as if you don’t have enough confidence to make a clear statement—in which case you can’t expect your readers to believe in your research either. Write in the present tense, don’t use modal verbs that express varying degrees of certainty (such as may, might, or could ), and remember that you are not drawing a conclusion while trying not to exaggerate but making a clear statement that you then, in a way, try to disprove . And if that happens, that is not something to fear but an important part of the scientific process.

Similarly, don’t use “we hypothesize” when you explain the implications of your research or make predictions in the conclusion section of your manuscript, since these are clearly not hypotheses in the true sense of the word. As we said earlier, you will find that many authors of academic articles do not seem to care too much about these rather subtle distinctions, but thinking very clearly about your own research will not only help you write better but also ensure that even that infamous Reviewer 2 will find fewer reasons to nitpick about your manuscript.

Perfect Your Manuscript With Professional Editing

Now that you know how to write a strong research hypothesis for your research paper, you might be interested in our free AI proofreader , Wordvice AI, which finds and fixes errors in grammar, punctuation, and word choice in academic texts. Or if you are interested in human proofreading , check out our English editing services , including research paper editing and manuscript editing .

On the Wordvice academic resources website , you can also find many more articles and other resources that can help you with writing the other parts of your research paper , with making a research paper outline before you put everything together, or with writing an effective cover letter once you are ready to submit.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Hypothesis is an educated guess or proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on some initial observations or data. It is a tentative statement that can be tested and potentially proven or disproven through further investigation and experimentation.

Hypothesis is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments and the collection and analysis of data. It is an essential element of the scientific method, as it allows researchers to make predictions about the outcome of their experiments and to test those predictions to determine their accuracy.

Types of Hypothesis

Types of Hypothesis are as follows:

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a statement that predicts a relationship between variables. It is usually formulated as a specific statement that can be tested through research, and it is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is no significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as a starting point for testing the research hypothesis, and if the results of the study reject the null hypothesis, it suggests that there is a significant difference or relationship between variables.

Alternative Hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is a significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as an alternative to the null hypothesis and is tested against the null hypothesis to determine which statement is more accurate.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction of the relationship between variables. For example, a researcher might predict that increasing the amount of exercise will result in a decrease in body weight.

Non-directional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the relationship between variables but does not specify the direction. For example, a researcher might predict that there is a relationship between the amount of exercise and body weight, but they do not specify whether increasing or decreasing exercise will affect body weight.

Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement that assumes a particular statistical model or distribution for the data. It is often used in statistical analysis to test the significance of a particular result.

Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a statement that assumes more than one condition or outcome. It can be divided into several sub-hypotheses, each of which represents a different possible outcome.

Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement that is based on observed phenomena or data. It is often used in scientific research to develop theories or models that explain the observed phenomena.

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement that assumes only one outcome or condition. It is often used in scientific research to test a single variable or factor.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is a statement that assumes multiple outcomes or conditions. It is often used in scientific research to test the effects of multiple variables or factors on a particular outcome.

Applications of Hypothesis

Hypotheses are used in various fields to guide research and make predictions about the outcomes of experiments or observations. Here are some examples of how hypotheses are applied in different fields:

- Science : In scientific research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain natural phenomena. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular variable on a natural system, such as the effects of climate change on an ecosystem.

- Medicine : In medical research, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of treatments and therapies for specific conditions. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new drug on a particular disease.

- Psychology : In psychology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of human behavior and cognition. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular stimulus on the brain or behavior.

- Sociology : In sociology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of social phenomena, such as the effects of social structures or institutions on human behavior. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of income inequality on crime rates.

- Business : In business research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain business phenomena, such as consumer behavior or market trends. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new marketing campaign on consumer buying behavior.

- Engineering : In engineering, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of new technologies or designs. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the efficiency of a new solar panel design.

How to write a Hypothesis

Here are the steps to follow when writing a hypothesis:

Identify the Research Question

The first step is to identify the research question that you want to answer through your study. This question should be clear, specific, and focused. It should be something that can be investigated empirically and that has some relevance or significance in the field.

Conduct a Literature Review

Before writing your hypothesis, it’s essential to conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known about the topic. This will help you to identify the research gap and formulate a hypothesis that builds on existing knowledge.

Determine the Variables

The next step is to identify the variables involved in the research question. A variable is any characteristic or factor that can vary or change. There are two types of variables: independent and dependent. The independent variable is the one that is manipulated or changed by the researcher, while the dependent variable is the one that is measured or observed as a result of the independent variable.

Formulate the Hypothesis

Based on the research question and the variables involved, you can now formulate your hypothesis. A hypothesis should be a clear and concise statement that predicts the relationship between the variables. It should be testable through empirical research and based on existing theory or evidence.

Write the Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is the opposite of the alternative hypothesis, which is the hypothesis that you are testing. The null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference or relationship between the variables. It is important to write the null hypothesis because it allows you to compare your results with what would be expected by chance.

Refine the Hypothesis

After formulating the hypothesis, it’s important to refine it and make it more precise. This may involve clarifying the variables, specifying the direction of the relationship, or making the hypothesis more testable.

Examples of Hypothesis

Here are a few examples of hypotheses in different fields:

- Psychology : “Increased exposure to violent video games leads to increased aggressive behavior in adolescents.”

- Biology : “Higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will lead to increased plant growth.”

- Sociology : “Individuals who grow up in households with higher socioeconomic status will have higher levels of education and income as adults.”

- Education : “Implementing a new teaching method will result in higher student achievement scores.”

- Marketing : “Customers who receive a personalized email will be more likely to make a purchase than those who receive a generic email.”

- Physics : “An increase in temperature will cause an increase in the volume of a gas, assuming all other variables remain constant.”

- Medicine : “Consuming a diet high in saturated fats will increase the risk of developing heart disease.”

Purpose of Hypothesis

The purpose of a hypothesis is to provide a testable explanation for an observed phenomenon or a prediction of a future outcome based on existing knowledge or theories. A hypothesis is an essential part of the scientific method and helps to guide the research process by providing a clear focus for investigation. It enables scientists to design experiments or studies to gather evidence and data that can support or refute the proposed explanation or prediction.

The formulation of a hypothesis is based on existing knowledge, observations, and theories, and it should be specific, testable, and falsifiable. A specific hypothesis helps to define the research question, which is important in the research process as it guides the selection of an appropriate research design and methodology. Testability of the hypothesis means that it can be proven or disproven through empirical data collection and analysis. Falsifiability means that the hypothesis should be formulated in such a way that it can be proven wrong if it is incorrect.

In addition to guiding the research process, the testing of hypotheses can lead to new discoveries and advancements in scientific knowledge. When a hypothesis is supported by the data, it can be used to develop new theories or models to explain the observed phenomenon. When a hypothesis is not supported by the data, it can help to refine existing theories or prompt the development of new hypotheses to explain the phenomenon.

When to use Hypothesis

Here are some common situations in which hypotheses are used:

- In scientific research , hypotheses are used to guide the design of experiments and to help researchers make predictions about the outcomes of those experiments.

- In social science research , hypotheses are used to test theories about human behavior, social relationships, and other phenomena.

- I n business , hypotheses can be used to guide decisions about marketing, product development, and other areas. For example, a hypothesis might be that a new product will sell well in a particular market, and this hypothesis can be tested through market research.

Characteristics of Hypothesis

Here are some common characteristics of a hypothesis:

- Testable : A hypothesis must be able to be tested through observation or experimentation. This means that it must be possible to collect data that will either support or refute the hypothesis.

- Falsifiable : A hypothesis must be able to be proven false if it is not supported by the data. If a hypothesis cannot be falsified, then it is not a scientific hypothesis.

- Clear and concise : A hypothesis should be stated in a clear and concise manner so that it can be easily understood and tested.

- Based on existing knowledge : A hypothesis should be based on existing knowledge and research in the field. It should not be based on personal beliefs or opinions.

- Specific : A hypothesis should be specific in terms of the variables being tested and the predicted outcome. This will help to ensure that the research is focused and well-designed.

- Tentative: A hypothesis is a tentative statement or assumption that requires further testing and evidence to be confirmed or refuted. It is not a final conclusion or assertion.

- Relevant : A hypothesis should be relevant to the research question or problem being studied. It should address a gap in knowledge or provide a new perspective on the issue.

Advantages of Hypothesis

Hypotheses have several advantages in scientific research and experimentation: