Why Do We Have Prisons in the United States?

The Enlightenment brought the idea that punishments should be certain and mild, rather than harsh with lots of pardons and exceptions.

What is prison for? That’s a question a growing movement is asking as it looks beyond reforming prisons and sentencing laws, and imagines abolishing incarceration altogether. To think about what that might look like, it’s worth considering how the U.S. prison system began , as historian Jim Rice did in his analysis of an early Maryland penitentiary.

Maryland based its criminal law on English precedent, which meant terrifying punishments like hanging for minor theft, but also selective enforcement of the penalties with frequent pardons that demonstrated the mercy of officials. But where English lawmakers feared poor migrants wandering the country, Maryland’s upper classes needed more laborers than they could find. So, in place of the death penalty, thieves in the state were typically lashed and fined, keeping them alive while plunging them into debt. Those who couldn’t pay might be sold into servitude.

Then, in 1789, as Baltimore grew from a village to a city desperately in need of public works crews, the state passed the “Wheelbarrow Act.” This made most serious offenses punishable with hard labor on roads and the Baltimore harbor—up to seven years for free men or 14 for enslaved men.

But the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century was an era of criminal justice reform on both sides of the Atlantic. The Enlightenment brought the idea that punishments should be certain and mild, rather than harsh with lots of pardons and exceptions, and that they should relate only to the crime, not the status of the person being punished. This also offered a more formal way to address crime in growing urban areas where officials could no longer respond to lawbreaking based on personal familiarity with the participants in a dispute.

In 1809, Maryland joined the growing ranks of U.S. states and European countries punishing crimes at penitentiaries. As the word suggested, the theory behind the institutions was that inmates could be induced to repent and reform. Not surprisingly, Maryland determined that a key tool in this project was “labour of the hardest and most servile kind,” including textile work, nail-making, and housekeeping. And while reformers expected penitentiaries to provide religious education and tailor work assignments to the goal of character improvement, in practice they were geared toward the fiscal needs of the institution, which the state expected to be self-supporting.

Another key divergence between theory and practice involved black convicts. Lawmakers assumed that African-Americans—free or enslaved—were inherently unreformable and that “prison life too closely resembled everyday black life to hold any real terror,” Rice writes. Nonetheless, black people flooded into the penitentiary.

Weekly Digest

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

From the start, the penitentiary system didn’t fulfill reformers’ dreams. But the system made sense to officials who needed to keep order in bustling cities and supply labor to growing industries. The question today is what role prisons fill for the people who support them, and what alternatives might work better for the communities that bear the brunt of punishment.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Beryl Markham, Warrior of the Skies

- The Legal Struggles of the LGBTQIA+ Community in India

The Border Presidents and Civil Rights

Eurasianism: A Primer

Recent posts.

- Confucius in the European Enlightenment

- Fencer, Violinist, Composer: The Life of Joseph Bologne

- Watching an Eclipse from Prison

Support JSTOR Daily

A better path forward for criminal justice: Changing prisons to help people change

- Download a PDF of this chapter.

Subscribe to Governance Weekly

Christy visher and christy visher professor - university of delaware john eason john eason associate professor - university of wisconsin.

- 17 min read

Below is the third chapter from “A Better Path Forward for Criminal Justice,” a report by the Brookings-AEI Working Group on Criminal Justice Reform. You can access other chapters from the report here .

Prison culture and environment are essential to public health and safety. While much of the policy debate and public attention of prisons focuses on private facilities, roughly 83 percent of the more than 1,600 U.S. facilities are owned and operated by states. 1 This suggest that states are an essential unit of analysis in understanding the far-reaching effects of imprisonment and the site of potential solutions. Policy change within institutions has to begin at the state level through the departments of corrections. For example, California has rebranded their state corrections division and renamed it the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. For many, these are not only name changes but shifts in policy and practice. In this chapter, we rethink the treatment environment of the prison by highlighting strategies for developing cognitive behavioral communities in prison—immersive cognitive communities. This new approach promotes new ways of thinking and behaving for both incarcerated persons and correctional staff. Behavior change requires changing thinking patterns and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based strategy that can be utilized in the prison setting. We focus on short-, medium-, and long-term recommendations to begin implementing this model and initiate reforms for the organizational structure of prisons.

Level Setting

The U.S. has seen a steady decline in the federal and state prison population over the last eleven years, with a 2019 population of about 1.4 million men and women incarcerated at year-end, hitting its lowest level since 1995. 2 With the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, criminal justice reformers have urged a continued focus on reducing prison populations and many states are permitting early releases of nonviolent offenders and even closing prisons. Thus, we are likely to see a dramatic reduction in the prison population when the data are tabulated for 2020.

However, it is undeniable that the U.S. will continue to use incarceration as a sanction for criminal behavior at a much higher rate than in other Western countries, in part because of our higher rate of violent offenses. Consequently, a majority of people incarcerated in the U.S. are serving a prison sentence for a violent offense (58 percent). The most serious offense for the remainder is property offenses (16 percent), drug offenses (13 percent), or other offenses (13 percent; generally, weapons, driving offenses, and supervision violations). 3 Moreover, the majority of people in U.S. prisons have been previously incarcerated. The prison population is largely drawn from the most disadvantaged part of the nation’s population: mostly men under age 40, disproportionately minority, with inadequate education. Prisoners often carry additional deficits of drug and alcohol addictions, mental and physical illnesses, and lack of work experience. 4

According to data compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, the average sentence length in state courts for those sentenced to confinement in a state prison is about 4 years and the average time served is about 2.5 years. Those sentenced for a violent offense typically serve about 4.7 years with persons sentenced for murder or manslaughter serving an average of 15 years before their release. 5 Thus, it is important to consider the conditions of prison life in understanding how individuals rejoin society at the conclusion of their sentence. Are they prepared to be valuable community members? What lessons have they learned during their confinement that may help them turn their life around? Will they be successful in avoiding a return to prison? What is the most successful path for helping returning citizens reintegrate into their communities?

Regrettably, prison life is often fraught with difficulty. Being sentenced to incarceration can be traumatic, leading to mental health disorders and difficulty rejoining society. Incarcerated individuals must adjust to the deprivation of liberty, separation from family and social supports, and a loss of personal control over all aspects of one’s life. In prison, individuals face a loss of self-worth, loneliness, high levels of uncertainty and fear, and idleness for long periods of time. Imprisonment disrupts the routines of daily life and has been described as “disorienting” and a “shock to the system”. 6 Further, some researchers have described the existence of a “convict code” in prison that governs behavior and interactions with norms of prison life including mind your own business, no snitching, be tough, and don’t get too close with correctional staff. While these strategies can assist incarcerated persons in surviving prison, these tools are less helpful in ensuring successful reintegration.

Thus, the entire prison experience can jeopardize the personal characteristics required to be effective partners, parents, and employees once they are released. Coupled with the lack of vocational training, education, and reentry programs, individuals face a variety of challenges to reintegrating into their communities. Successful reintegration will not only improve public safety but forces us to reconsider public safety as essential to public health.

Despite the toll of difficult conditions of prison, people who are incarcerated believe that they can be successful citizens. In surveys and interviews with men and women in prison, the majority express hope for their future. Most were employed before their incarceration and have family that will help them get back on their feet. Many have children that they were supporting and want to reconnect with. They realize that finding a job may be hard, but they believe they will be able to avoid the actions that got them into trouble, principally committing crimes and using illegal substances. 7 Research also shows that most individuals with criminal records, especially those convicted of violent crimes, were often victims themselves. This complicates the “victim”-“offender” binary that dominates the popular discourse about crime. By moving beyond this binary, we propose cognitive behavioral therapy, among a host of therapeutic approaches, as part of a broader restorative approach.

Despite having histories of associating with other people who commit crimes and use illegal drugs, incarcerated individuals have pro-social family and friends in their lives. They also may have some personality characteristics that make it difficult to resist involvement in criminal behavior, including impulsivity, lack of self-control, anger/defiance, and weak problem-solving and coping skills. Psychologists have concluded that the primary individual characteristics influencing criminal behavior are thinking patterns that foster criminal activity, associating with other people who engage in criminal activity, personality patterns that support criminal activity, and a history of engaging in criminal activity. 8 While the context constrains individual behavior and choices, the motivation for incarcerated individuals to change their behavior is rooted in their value of family and other positive relationships. However, most prison environments pose significant challenges for incarcerated individuals to develop motivation to make positive changes. Interpersonal relationships in prison are difficult as there is often a culture of mistrust and suspicion coupled with a profound absence of empathy. Despite these challenges, cognitive behavioral interventions can provide a successful path for reintegration.

Many psychologists believe that changing unwanted or negative behaviors requires changing thinking patterns since thoughts and feelings affect behaviors. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) emerged as a psycho-social intervention that helps people learn how to identify and change destructive or disturbing thought patterns that have a negative influence on behavior and emotions. It focuses on challenging and changing unhelpful cognitive distortions and behaviors, improving emotional regulation, and developing personal coping strategies that target solving current problems. 9 In most cases, CBT is a gradual process that helps a person take incremental steps towards a behavior change. CBT has been directed at a wide range of conditions including various addictions (smoking, alcohol, and drug use), eating disorders, phobias, and problems dealing with stress or anxiety. CBT programs help people identify negative thoughts, practice skills for use in real-world situations, and learn problem-solving skills. For example, a person with a substance use disorder might start practicing new coping skills and rehearsing ways to avoid or deal with a high-risk situation that could trigger a relapse.

Since criminal behavior is driven partly by certain thinking patterns that predispose individuals to commit crimes or engage in illegal activities, CBT helps people with criminal records change their attitudes and gives them tools to avoid risky situations. Cognitive behavioral therapy is a comprehensive and time-consuming treatment, typically, requiring intensive group sessions over many months with individualized homework assignments. Evaluations of CBT programs for justice-involved people found that cognitive restructuring treatment was significantly effective in reducing criminal behavior, with those receiving CBT showing recidivism reductions of 20 to 30 percent compared to control groups. 10 Thus, the widespread implementation of cognitive behavioral therapy as part of correctional programming could lead to fewer rearrests and lower likelihood of reincarceration after release. CBT can also be used to mitigate prison culture and thus help reintegrate returning citizens back into their communities.

Thus, the widespread implementation of cognitive behavioral therapy as part of correctional programming could lead to fewer rearrests and lower likelihood of reincarceration after release.

Even the most robust CBT program that meets three hours per week leaves 165 hours a week in which the participant is enmeshed in the typical prison environment. Such an arrangement is bound to dilute the therapy’s impact. To counter these negative influences, the new idea is to connect CBT programming in prison with the old idea of therapeutic communities. Therapeutic communities—either in prison or the community—were established as a self-help substance use rehabilitation approach and instituted the idea that separating the target population from the general population would allow a pro-social community to develop and thereby discourage antisocial cognitions and behaviors. The therapeutic community model relies heavily on participant leadership and requires participants to intervene in arguments and guide treatment groups. Inside prisons, therapeutic communities are a separate housing unit that fosters a rehabilitative environment.

Cognitive Communities in prison would be an immersive experience in cognitive behavioral therapy involving cognitive restructuring, anti-criminal modeling, skill building, problem-solving, and emotion management. These communities would promote new ways of thinking and behaving among its participants around the clock, from breakfast in the morning through residents’ daily routines, including formal CBT sessions, to the evening meal and post-dinner activities. Blending the best aspects of therapeutic communities with CBT principles would lead to Cognitive Communities with several key elements: a separate physical space, community participation in daily activities, reinforcement of pro-social behavior, use of teachable moments, and structured programs. This cultural shift in prison organization provides a foundation for restorative justice practices in prisons.

Accordingly, our recommendations include:

Short-Term Reforms

Create Transforming Prisons Act

Accelerate decarceration begun during pandemic.

Medium-Term Reforms

Encourage Rehabilitative Focus in State Prisons

Foster greater use of community sanctions.

Long-Term Reforms

Embrace Rehabilitative/Restorative Community Justice Models

Encourage collaborations between corrections agencies and researchers, short-term reforms.

To begin transforming prisons to help prisons and people change, a new funding opportunity for state departments of correction is needed. We propose the Transforming Prisons Act (funded through the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance) which would permit states to apply for funds to support innovative programs and practices that would improve prison conditions both for the people who live in prisons and work in prisons. This dual approach would begin to transform prisons into a more just and humane experience for both groups. These new funds could support broad implementation of Cognitive Communities by training the group facilitators and the correctional staff assigned to the specialized prison units. Funds could also be used to broaden other therapeutic programming to support individuals in improving pro-social behaviors through parenting classes, family engagement workshops, anger management, and artistic programming. One example is the California Transformative Arts which promotes self-awareness and improves mental health through artistic expression. Together, these programs could mark a rehabilitative turn in corrections.

While we work to change policies and practices to make prisons more humane, we also need to work towards decarceration. The COVID-19 crisis has enabled innovations in diverting and improving efforts to reintegrate returning citizens in the U.S. During the pandemic, many states took bold steps in implementing early release for older incarcerated persons especially those with health disorders. Research shows that returning citizens of advanced age and with poor health conditions are far less likely to commit crime after release. This set of circumstances makes continued diversion and reintegration of this population a much wiser investment than incarceration.

MEDIUM-TERM REFORMS

In direct response to calls to abolish prisons and defund the police, state prisons should move away from focusing on incapacitation to rehabilitation. To assist in this change, federal funds should be tied to embracing a rehabilitative mission to transform prisons. This transformation should be rooted in evidence-based therapeutic programming, documenting impacts on both incarcerated individuals and corrections staff. Prison good-time policies should be revisited so that incarcerated individuals receive substantial credit for participating in intensive programming such as Cognitive Communities. With a backdrop of an energized rehabilitative philosophy, states should be supported in their efforts to implement innovative models and programming to improve the reintegration of returning citizens and change the organizational structure of their prisons.

In direct response to calls to abolish prisons and defund the police, state prisons should move away from focusing on incapacitation to rehabilitation.

As the country with the highest incarceration rate in the world, current U.S. incarceration policies and practices are costly for families, communities, and state budgets. Openly punitive incarceration policies make it exceedingly difficult for incarcerated individuals to successfully reintegrate into communities as residents, family members, and employees. A long-term policy goal in the U.S. must be to reduce our over-reliance on incarceration through shorter prison terms, increased reliance on community sanctions, and closing prisons. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed that decarceration poses minimal risk to community safety. Given this steady decline in the prison population and decline in prison building in the U.S. since 2000, we encourage other types of development in rural communities to loosen the grip of prisons in these areas. Alternative development for rural communities is important because the most disadvantaged rural communities are both senders of prisoners and receivers of prisons with roughly 70 percent of prison facilities located in rural communities.

LONG-TERM REFORMS

Public safety and public health goals can be achieved through Community Justice Centers—these are sites that act as a diversion preference for individuals who may be in a personal crisis due to mental health conditions, substance use, or family trauma. Recent research demonstrates that using social or public health services to intervene in such situations can lead to better outcomes for communities than involving the criminal justice system. To be clear, many situations can be improved by crisis intervention expertise specializing in de-escalation rather than involving the justice system which may have competing objectives. Community Justice Centers are nongovernmental organizations that divert individuals in crisis away from law enforcement and the justice system. Such diversion also helps ease the social work burden on the justice system that it is often ill-equipped to handle.

Researchers and corrections agencies need to develop working relationships to permit the study of innovative organizational approaches. In the past, the National Institute of Justice created a researcher-practitioner partnership program , whereby local researchers worked with criminal justice practitioners (generally, law enforcement) to develop research projects that would benefit local criminal justice agencies and test innovative solutions to local problems. A similar program could be announced to help researchers assist corrections agencies and officials in identifying research projects that could address problems facing prisons and prison officials (e.g., safety, staff burnout, and prisoner grievance procedures).

Recommendations for Future Research

Some existing jail and prison correctional systems are implementing broad organization changes, including immersive faith-based correctional programs, jail-based 60- to 90-day reentry programs to prepare individuals for their transition to the community, Scandinavian and other European models to change prison culture, and an innovative Cognitive Community approach operating in several correctional facilities in Virginia. However, these efforts have not been rigorously evaluated. New models could be developed and tested widely, preferably through randomized controlled trials, and funded by the research arm of the Department of Justice, the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), or various private funders, including Arnold Ventures.

Correctional agencies in some states may be ready to implement the Cognitive Community model using a separate section of a prison or smaller facility not in use. Funding is needed to evaluate these pilot efforts, assess fidelity to the model standards, identify challenges faced in implementing the model, and propose any modifications to improve the proposed Cognitive Community model. Full-scale rigorous tests of the Cognitive Community model are needed which would randomly assign eligible inmates to the Cognitive Community environment or to continue to carry out their sentence in a regular prison setting. Ideally, these studies would observe the implementation of the program, assess intermediate outcomes while participants are enrolled in the program, follow participants upon release and examine post-release experiences in the post-release CBT program, and then assess a set of reentry outcomes at several intervals for at least one year after release.

Prison culture and environment are essential to community public health and safety. Incarcerated individuals have difficulty successfully reintegrating into their communities after release because the environment in most U.S. prisons is not conducive to positive change. Normalizing prison environments with evidence-based programming, including cognitive behavioral therapy, education, and personal development, will help incarcerated individuals lead successful lives in the community as family members, employees, and community residents. States need to move towards less reliance on incarceration and more attention to community justice models.

Recommended Readings

- Eason, John M. 2017. Big House on the Prairie: Rise of the Rural Ghetto and Prison Proliferation . Chicago, IL: Univ of Chicago Press.

Travis, J., Western, B., and Redburn, S. (Eds.). 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. National Research Council; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Committee on Law and Justice; Committee on Causes and Consequences of High Rates of Incarceration. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Orrell, B. (Ed). 2020. Rethinking Reentry . Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.

Mitchell, Meghan M., Pyrooz, David C., & Decker, Scott. H. 2020. “Culture in prison, culture on the street: the convergence between the convict code and code of the street.” Journal of Crime and Justice . DOI: 10.1080/0735648X.2020.1772851 .

Haney, C. 2002. “The Psychological Impact of Incarceration: Implications for Post-Prison Adjustment.” https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/psychological-impact-incarceration-implications-post-prison-adjustment .

- Carson, E. Ann. 2020. Prisoners in 2019. NCJ 255115. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Travis, Jeremy, Bruce Western, and Steven Redburn, (Eds.). 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. National Research Council; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Committee on Law and Justice; Committee on Causes and Consequences of High Rates of Incarceration . Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Kaeble, Danielle. 2018. Time Served in State Prison, 2016. NCJ 252205. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Haney, Craig. 2002. “The Psychological Impact of Incarceration: Implications for Post-Prison Adjustment.” Prepared for the Prison to Home Conference, January 30–31, 2002. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/psychological-impact-incarceration-implications-post-prison-adjustment .

- Visher, Christy and Nancy LaVigne. 2021. “Returning home: A pathbreaking study of prisoner reentry and its challenges.” In P.K. Lattimore, B.M. Huebner, & F.S. Taxman (eds.), Handbook on moving corrections and sentencing forward: Building on the record (pp. 278–311). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Latessa, Edward. 2020. “Triaging services for individuals returning from prison.” In B. Orrell (Ed.), Rethinking Reentry . Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.

- Nana Landenberger and Mark Lipsey. 2005. “The positive effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for offenders: A meta-analysis of factors associated with effective treatment.” Journal of Experimental Criminology , 1, 451–476.

Governance Studies

Vanda Felbab-Brown

March 21, 2024

William A. Galston

March 8, 2024

Thea Sebastian, Hanna Love

March 6, 2024

Life Behind the Wall

Jails, Prisons and the US Correctional System Essay

Introduction, the disturbing fact in the united states is that today, the american, works cited.

A correctional system is meant to be a holding place for antisocial elements so that law and order is maintained in a society. The term ‘jail’ and ‘prison’ are interchangeably used however; there are significant differences in its usage and operative principles. This essay outlines the main differences between jails and prisons and the connected related components of the correctional system in the United States.

Hall states that a “Jail is a place for the confinement of persons in lawful detention; Prison is a place where persons convicted are confined” (2009). In the United States, Jails are short term holding facilities where first time offenders and those committing minor offenses are held. They are also used as temporary facilities for transferring those convicted of more serious offences on their way to the prison. Jails are facilities created and used by cities or counties while prisons are facilities created and used by state or federal authorities. There is a time restriction on jail time which extends from a few hours to a maximum of about one and a half years. Prison time however can extend up to life imprisonment and even the death row. Consequently, Jail inmates have a higher turnover while those in prisons are usually long term offenders. The environment inside a jail and a prison are markedly different. Since jails have small time offenders and the ‘rookies’ they are less organized and less violent than prisons. Prisons usually hold the ‘hard core’ or the serious crime offenders, are prone to violence and have organized prison gangs operating from within the walls of the prison. Because of the nature of the crimes, Jails have large transient populations while prisons have a smaller clientele.

‘Correctional’ system has the largest population of prisoners in the world. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice statistics, “2,299,116 prisoners were held in federal or state prisons or in local jails” (2008, para 1) as on 30 June 2007. Such a large population has led to overcrowding of jails and prisons with its deleterious effects on the society as a whole. According to (Cilluffo ), the U.S. prison ”facilities (are) hugely overcrowded – operating at 200% capacity”(2006, 4) leading to tremendous administrative and logistical problems for the prison officials. Since jail populations are larger than prison populations, “most prisoners consider city and county jails to be worse than prison, especially facilities in the Deep South” (May, Ruddell, & Wood, 2008, p. 10).

For incarceration of juveniles, separate juvenile detention centers are set up. These juvenile detention centers are run much like a jail or a prison with strict rules, routine and punishment codes. The system however has not delivered any lessening of crime rates as Worall observes that, “The verdict for juvenile crime control, as opposed to prevention, is not a favorable one (2006, p. 325)”. In case of juvenile detention centers, the marked differences that characterize the adult holding facilities such as jails and prisons are blurred. There also exist privately funded prisons which hold prisoners on behalf of the states. “The first private prison opened 1984, and today, there are an estimated 165,000 secure beds in the U.S. being managed by the eight largest private corrections providers” (Seiter, 2008, p. 3).

In conclusion it can be reiterated that jails and prisons have many differences chiefly in the type of offenders they hold and the institutions that support them. Connected to the jails and prisons are also private prisons and juvenile detention centers which together make up the American Correctional System.

Bureau of Justice. ( 2008). Prison Statistics . Web.

Cilluffo, Frank J. (2006). Prison Radicalization: Are Terrorist Cells Forming in U.S. Cell Blocks? . Web.

Hall, D. (2009). Jails vs Prisons. Web.

May, D. C., Ruddell, R., & Wood, P. B. (2008). How Do Inmates Perceive Jail Conditions? A View From Jail Administrators. Web.

Seiter, R. P. (2008). Private Corrections: A Review of the Issues. Web.

Worall, J. (2006). Crime Control in America, An Assessment of the Evidence. Boston: Pearsons Education.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 16). Jails, Prisons and the US Correctional System. https://ivypanda.com/essays/jails-prisons-and-the-us-correctional-system/

"Jails, Prisons and the US Correctional System." IvyPanda , 16 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/jails-prisons-and-the-us-correctional-system/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Jails, Prisons and the US Correctional System'. 16 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Jails, Prisons and the US Correctional System." March 16, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/jails-prisons-and-the-us-correctional-system/.

1. IvyPanda . "Jails, Prisons and the US Correctional System." March 16, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/jails-prisons-and-the-us-correctional-system/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Jails, Prisons and the US Correctional System." March 16, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/jails-prisons-and-the-us-correctional-system/.

- Correctional Facilities: Baltimore City Jail' Case

- An Introduction to Correctional Facilities

- Alternatives to Juvenile Detention Centers

- Shawangunk Correctional Facility

- Differences Between Jails and Prisons

- Discussion of Correctional System

- Modern Prison: Correctional Task Force Project

- Exploring Jail Operations

- Aspects of the Juvenile Sentencing Efficiency

- Inmate Custody & Control in Correctional Facility

- Do Drug Enforcement Laws Help to Reduce Other Crimes?

- Providing Justice for Victims, Offenders and Community

- Expanding Theories: Criminology Revisited

- Cutting-Off Hand Keeps Off Crimes in the Country

- Organized Crime in the United States

Prisons are failing. It’s time to find an alternative

68% of people released from prison in the US are rearrested within three years. Image: REUTERS/Shannon Stapleton

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Baillie Aaron

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Social Innovation is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, social innovation.

In recent years, the use of imprisonment as a response to crime and violence has risen steadily across the globe.

More than 10 million people around the world are currently behind bars . As our social systems are being reshaped by Globalization 4.0, it is time to consider whether our current approach to prison and punishment is keeping us safe.

Most criminal justice systems around the world are increasingly reliant on prisons. Globally, the number of prisoners has grown by almost 20% since the turn of the millennium and continues to rise.

The players involved in the prison industry include hedge funds, architects, utilities and construction companies, and a number of multinationals employing free or reduced-cost prison labour.

Overall, prison expenses make up a significant portion of government budgets: in the US, $81 billion is spent annually on public correctional agencies alone (not including private prisons).

Is the investment in prisons justified?

One major consideration is whether prisons are effective or not in achieving their stated objective of keeping society safe.

In most countries, the evidence is clear that they are not. In the US, two in three (68%) of people released from prison are rearrested within three years of release. In England and Wales, two in three (66%) of young people and nearly half of adults leaving prison will commit another crime within a year .

However, a handful of countries are bucking this trend. In Norway, only one in five (20%) of adults leaving prison are reconvicted within two years of release. Similar reoffending rates are seen across the Scandinavian nations. In Uruguay’s National Rehabilitation Centre, the recidivism rate is just 12%; in Germany, it’s 33% within three years.

What’s causing the difference in reoffending?

The common thread is that the most effective prisons are the ones that look least like prisons.

In most countries, including the US and UK, prisons prioritise punishment: they limit access to families, education and employment. Prisoners can be locked in their cells for 23 hours a day. Overcrowding, drugs, gangs and riots are common, and amenities like food and access to healthcare are basic.

But reoffending rates are lowest in prison facilities that minimise the focus on punishment: those that try to mirror life in the outside world.

In these facilities, prisoners can wear their own clothes, live in their own rooms with private showers, cook their own meals, access paid work and receive conjugal visits. Some have internet access throughout.

These prisons prioritise relationships and decency: they focus on rehabilitating prisoners through therapeutic interventions, employment and education. They are a far cry from being centres of punishment.

Some cities have already started applying this logic to other public institutions designed to tackle crime, veering away from a punishment and prison-based approach.

Glasgow, for example, was branded the European murder capital by the World Health Organisation in 2005. Over the past decade, knife crime has plummeted.

The shift is not due to an increase in punishment but rather, a major change in the role of the Scottish police force. Over the past decade, they have introduced a public health approach , working collaboratively with health, education and social services.

Before arresting and prosecuting violent perpetrators, they ask what caused the act of violence, how they can reduce the associated risks, and what best practice approaches would prevent future offences.

In Eugene, Oregon’s third-largest city, medics and crisis workers are the typical first responders to emergency calls – not the police. This approach is tailored, more effective and cheaper, providing city residents with both financial and social benefits.

An extension of this approach could see a gradual replacement of the entire traditional police service with an emergency response team, with specialised response units for mental health, neighbourhood disputes, domestic violence, drug crime, and serious violence.

Localised, person-centred services would tackle the root causes of offending with the real solutions, sustainably reducing crime and improving safety for everyone.

Another popular approach for delivering accountability outside the traditional criminal justice system is restorative justice. In this process, which originated in indigenous communities, the victim chooses to meet with the individuals or representatives who caused them harm.

In a facilitated face-to-face conference, they agree a resolution, repair the harm caused and find a way forwards – for example, a heartfelt apology, commitment to receive professional treatment, community service or a donation. Restorative justice ensures perpetrators of crimes take responsibility for the harm that they have caused and that victims of crimes are empowered to be a part of the process.

A 2001 UK government-funded study found that in a randomised control trial, restorative justice reduced the frequency of reoffending by 14% and the majority of victims were satisfied with the process.

A separate study showed that diverting young people who committed crimes from community orders to a pre-court restorative justice process would produce lifetime cost savings of £7,000 per person, and save society £1 billion over a decade.

Have you read?

We have solutions to crime. we just need to scale them, what’s behind south korea’s elderly crime wave, from prisoner to professor: why criminal records shouldn't keep people out of college.

How do we move to a new paradigm for delivering punishment?

Rethinking our traditional punitive approaches to reducing crime through public health diversions, restorative justice or other means could provide us with major wins in increasing public safety, reducing crime and cutting costs.

While it will require comprehensive cross-departmental engagement to achieve systems change, much of the work has already been done. Academic research, non-profit evaluations and city trials reveal clear best practice that can be implemented and scaled globally.

Technological advances could help us make some of these changes more efficiently. Bringing 21st Century digital tools into the public sector would enable often siloed government departments to communicate, share data and recognise patterns through artificial intelligence.

Database integration would enable a joined-up social services system, and a coordinated emergency response team. Developments in public health technology can enable individuals to better manage their physical, mental health and social care needs.

Technology is not, however, a panacea and these innovations could have unintended consequences.

There have been attempts to replace human criminal justice decision-making with algorithms, for example with judicial sentencing or police dispatching. While this has clear efficiency and cost benefits, trials have seen the algorithms incorporating and exacerbating pre-existing racial biases and prejudice .

Some countries have tried to reduce prisoner numbers by using electronic tagging, monitoring and restricting offenders’ geographic and temporal movements. Critics have called it a false structural change: rather than tackle the root causes of offending to sustainably reduce reoffending, tagging just replaces one prison with another, keeping people locked in their homes and local communities.

As to tech solutions within prisons, they miss the point. Improving a failing system is not the answer, when the institution itself is fundamentally flawed. There’s only so much we can do to reform prison, when the evidence points to the best solution being an entirely different system.

Globalization 4.0 is a call for us to reimagine what our public institutions should look like. With surges in violence and new threats like cybersecurity and terrorism, alongside pressing needs to cut government expenditure, we have a lot more to lose if we don’t act soon.

As a society that created the internet and has sent a spacecraft to Mars, we are more than capable of implementing a better solution to reduce crime than a failing 200-year-old Victorian prison model.

Our prisons and the way we approach punishment should be at the top of the list for an overhaul. By updating our global approach to tackling crime, we have a unique opportunity to make our world a safer and a better place for all of us.

Author: Baillie Aaron is the founder and CEO of Spark Inside .

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Social Innovation .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

3 social economy innovators that are driving change in Brazil

Eliane Trindade

April 4, 2024

Switzerland is the world’s top talent hub. Here's why

Building trust amid uncertainty – 3 risk experts on the state of the world in 2024

Andrea Willige

March 27, 2024

The social innovators empowering women worldwide

March 8, 2024

Digital public infrastructure – blessing or curse for women and girls?

Gerda Binder and Carolin Frankenhauser

March 5, 2024

How social innovation education can help solve the world's most pressing problems

Rahmin Bender-Salazar and Roisin Lyons

January 19, 2024

Prison System In America Essay Example

Imagine you are a prisoner in America, in for a crime you did not commit. You have been charged with the minimum sentence for murder (25 years) knowing you are not guilty. America’s prison system is flawed to say the least, with its long days, grueling work, and its negative ability to rehabilitate its members back to society. America has maintained its prison systems since 1891, under Charles Foster, with little to no change to the way they go about taking care of their occupants. Many changes should be made to America’s prison system to alleviate is flaws in everyday life.

To determine how “effective” a prison system is, we must determine what is the ratio per 100,000 people arrested is. Additionally, testing its ability to rehabilitate and keep people out of prison establishes how worthwhile the prison system may be. Due to changing times and growing economies prison systems must adapt to styles that seem fit to their respective countries.

Personally, I believe we should look to Norway as a beacon to update and evaluate Americas Prison System. Norway's incarceration and rehabilitation rates beats most other competing prison systems globally. These components assemble a prison system that may prove more productive in a modernized society with more civilians. In this paper I argue that America can develop and adapt its prison systems to equate closer to Norway's, regarding mental/physical health, money spent per prisoner, and overall reduction in incarceration and an increase in rehabilitation.

Norway vs America’s prison systems

Norway's Prisons Systems are arguably the best prison system internationally. Norway's incarceration rate in 2014 was a ratio of 75 per 100,000 people arrested under law. Additionally, Norway has an annually increasing rehabilitation rate. From this past decade Norway has decreased its recidivism rate down to 20% of all prisoners reinterred into prisons after rehabilitation. Norway, as a growing country, avoids lots of obstacles regarding its inmates by what Bolorzul Dorjsuren from the Borgen project states as “taking a new approach” stating, “(Norway's) prisons’ accepting, caring and empathetic approach has paved the way for many prisoners into becoming fine citizens supporting their country’s economy” (Dorjuren). This demonstrates the effectiveness of Norway's Prisons as opposed to many other global ones.

America and its growing prison system have begun to backtrack on what its goals. It is unsafe and difficult to live in Americas prisons. The type of treatment you may receive may be determined by the crime for what you were sentenced with. America functions differently than many other countries. The American Prison System intends to steal your rights away and punish the criminal for years on end. America's prisons occupants are bound to its prisons. In America after serving a sentence, many prisoners have roughly a 66% chance of reinterring prisons after rehabilitation. The overwhelming majority of these people will spend most of their time in jail because it is normal for them. More than half of the recidivists have nothing when returning to society and thus, must steal to provide for themselves.

ADX VS Halden

Currently, in America there has been a heavy increase in the use of spending annually per prisoner. As populations grow, so will prisons. Rudy Gerhold from Kent Partnership states as “a growth of 300% more prisoners in America, spending per annuity will rise” (Gerhold). As expected, a prisoner for 20 years will cost less than a prisoner for life. This has become one of Americas biggest setbacks compared to Norway. Norway spends roughly 93,000 an inmate for each annual year, compared to America’s 23,000 spending budget per prisoner. Spending typically goes towards many things such as mental health and drug abuse counseling, anger management, necessities as well as food. Having more of this allows for more additional activities such as Norway's famous prison, Halden, wood working, mechanics, and music production. Additional growth and production allow for an increase in rehabilitation rates.

Contrary to Norway, as an American citizen, you can have up to life in jail for a crime you committed. In your respective prisons, you may be subject to violence for little to no reason at all. Some examples of this violence is seen and explained in a THE NEW REPUBLIC article by Matt Ford. He speaks about Prison Guards traumatizing sights in Prison. These stories go as far as, prisoners lying dead on the floor so long that “their face was flattened,” to other forms of torture such as inmates beat others with broken mop handles and giving chemical burns to other inmates with heated up shaving cream. Many of these victims needed outside help because they were harmed so badly. These atrocities happen in almost every prison. Americas most “secure” prison is known as Penitentiary, Administrative Maximum Prison, (ADX) known for being the most isolated prisons in America holding prisoners with violent pasts with other prisoners, foreign and domestic terrorists, and those who head drug and gang cartels.

Norway is a country which approaches a problem as a puzzle. Attempting to solve it regarding everyone. In 2009 Norway decided to change its maximum sentencing up to 21 years, with exceptions to severe cases such as war crimes and genocide which is punishable by 30 years and additional years if needed. However, despite this, Norway, and Bob Cameron from Slate, believes that keeping a progressive approach to occupants sentencing prioritizes rehabilitation as a primary strategy for reducing future criminal behavior. As a result of the citizens and occupants of Norway are safer and feel sheltered from any crime related threats.

Conclusion:

The adjustments needed for America must start now so change can begin soon to promote a beneficial economy.

Related Samples

- Sweden and Thailand's Relationship Essay Example

- Africa's Impact on The World of Today Essay Example

- Freedom In Modern Society Essay Example

- Frederick Douglass Speech Analysis

- Declining of United States Essay Sample

- Chernobyl Essay Sample

- Opinion Essay Sample about The First Amendment

- Robert Smalls: Unsung Heroes of the Civil War Essay Example

- Essay About Slavery in Canada

- Lee Boyd Malvo Case Study

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Suggested Results

Antes de cambiar....

Esta página no está disponible en español

¿Le gustaría continuar en la página de inicio de Brennan Center en español?

al Brennan Center en inglés

al Brennan Center en español

Informed citizens are our democracy’s best defense.

We respect your privacy .

- Analysis & Opinion

A Fundamental Failure of American Prisons

A new study finds that more than one in five state inmates “maxes out” of their prison term and is released back into society without any supervision or support.

- Cutting Jail & Prison Populations

- Social & Economic Harm

The most significant news of the week in criminal justice comes to use from the Pew Center, from its Public Safety Performance Project, which revealed Wednesday in a 22-page report a series of statistics that highlight one of the biggest failures of modern American incarceration: more than one in five state inmates “maxes out” of their prison term and is released back into society without any supervision or support.

The trend is getting worse, the folks at Pew tell us, and that means our prisons are churning out inmates who are more likely to become recidivists, which means that too many of these men and women will be back behind bars at a time when both state and federal authorities are trying to ease the scourge of mass incarceration (and prevent crime that it, eminently, preventable). Here’s the link to the full report and here is a summary that helps frame the issue:

Despite growing evidence and a broad consensus that the period immediately following release from prison is critical for preventing recidivism, a large and increasing number of offenders are maxing out—serving their entire sentences behind bars—and returning to their communities without supervision or support.

Between 1990 and 2012, the number of inmates who maxed out their sentences in prison grew 119 percent, from fewer than 50,000 to more than 100,000. These inmates do not have any legal conditions imposed on them, are not monitored by parole officers, and do not receive the assistance that can help them lead crime-free lives.

The increase in max-outs is largely the outcome of state policy choices over the past three decades that resulted in offenders serving higher proportions of their sentences behind bars. Yet new research suggests that for many offenders, shorter prison terms followed by supervision have the potential to reduce both recidivism and overall corrections costs.

What this means is that our prisons are heaping failure upon failure — and in so doing naturally making a dangerous situation worse. Not only are we incarcerating people for too long we also then are failing to prepare these inmates for a safe and productive reentry into society when we do finally consent to release them. It’s a waste of time, literally, to shun rehabilitative programs and policies that might aid these inmates upon reentry in favor of the harsh retributive policies that have swallowed up prison budgets in one jurisdiction after another.

"It is a harsh reality in many states that individuals are still released from prison with nothing more than $40 and a bus ticket,” the Brennan Center’s Lauren-Brooke Eisen told me Wednesday. Forty dollars actually is high . In Louisiana, for example , prison officials give exonerated prisoners a $20 debit card (it was $10 as recently as 2011) and no bus ticket upon their release from prison. In these circumstances what chance does a newly-released inmate have of getting a job, establishing healthy relationships, or simply functioning normally after decades of incarceration? The system, in other words, is set up to fail.

And these are only state figures. The federal Bureau of Prisons, with jurisdiction over 215,000 inmates, also does a terrible job of preparing inmates for their release. I’ve covered in just the past few years alone stories of mentally ill federal prisoners at the ADX-Florence “Supermax” facility in Colorado who are not getting proper care and treatment even as their release dates grow near. Each of these men represents a potential tragedy waiting to happen on the outside.

But the Pew Report also gives hope. In the past few years, lawmakers in Kansas, Kentucky, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina and West Virginia (note more Red States than Blue ones on that list) have enacted reforms that ensure the newly-released inmates are supervised in a way that may aid their transition from prison to the world beyond. Some states get it, in other words, and realize how self-defeating it is to send prisoners out in the world knowing that they will fail upon their release. And then there is this reasoned passage in the conclusion of the Report:

Policymakers are increasingly recognizing the fragility of the successful resumption of community life after incarceration. States and the federal government are committing significant resources to improve reentry planning and strengthen community supervision in response to evidence of their effectiveness in protecting public safety by preventing recidivism.

Research shows that during the months immediately after their release from prison—a period consumed by finding employment and housing and reconnecting with family—offenders are at the greatest risk of committing new crimes. Recent evidence also shows that supervised parolees are less likely to engage in new criminal behavior than max-outs. By employing evidence-based supervision practices, including using graduated sanctions rather than revocations for technical violations, states can reduce costs and recidivism.

This sensible policy is not so complicated, not so partisan, not so “soft on crime” that it cannot be achieved. The roadmap, the path, already exists. All that is needed is for more public officials to follow it.

The views expressed are the author’s own and not necessarily those of the Brennan Center for Justice.

(Photo: Fotolia)

Related Issues:

- Cutting Jail & Prison Populations

- Social & Economic Harm

Informed citizens are democracy’s best defense

Home — Essay Samples — Law, Crime & Punishment — Prison — Problems In The Prison System Of The United States

Problems in The Prison System of The United States

- Categories: Challenges Prison

About this sample

Words: 592 |

Published: Apr 2, 2020

Words: 592 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Law, Crime & Punishment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

6 pages / 2755 words

1 pages / 499 words

4 pages / 1877 words

3 pages / 1725 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Prison

Imagine being confined to a small, isolated cell, surrounded by the most dangerous criminals in the country, with no hope of escape. This is the reality for inmates at the Alcatraz Super Max Prison, one of the most secure and [...]

Prison life is a topic that has long fascinated and horrified the general public. It is a world that is hidden from view, yet it has a profound impact on the individuals who are incarcerated within its walls. In this essay, we [...]

Imagine being sentenced to a life behind bars, not just for a crime you committed, but for a crime committed against you. This is the harsh reality facing many inmates who have been convicted of rape and are now serving life [...]

The Wasco State Prison, located in Kern County, California, has been the subject of much scrutiny and controversy in recent years. This case study aims to examine the various issues that have arisen at the prison, including [...]

Burkhardt, B., 2014. Private Prisons in Public Discourse: Measuring Moral Legitimacy. Sociological Focus, 47(4), pp.279-298.Garland, D. (2001) The culture of control: Crime and social order in contemporary society. Oxford: [...]

The first juvenile court in the United States did not open until 1899. Prior to then, children over seven years old that broke the law were sent to adult prisons. There is a juvenile justice system now but there are still a lot [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

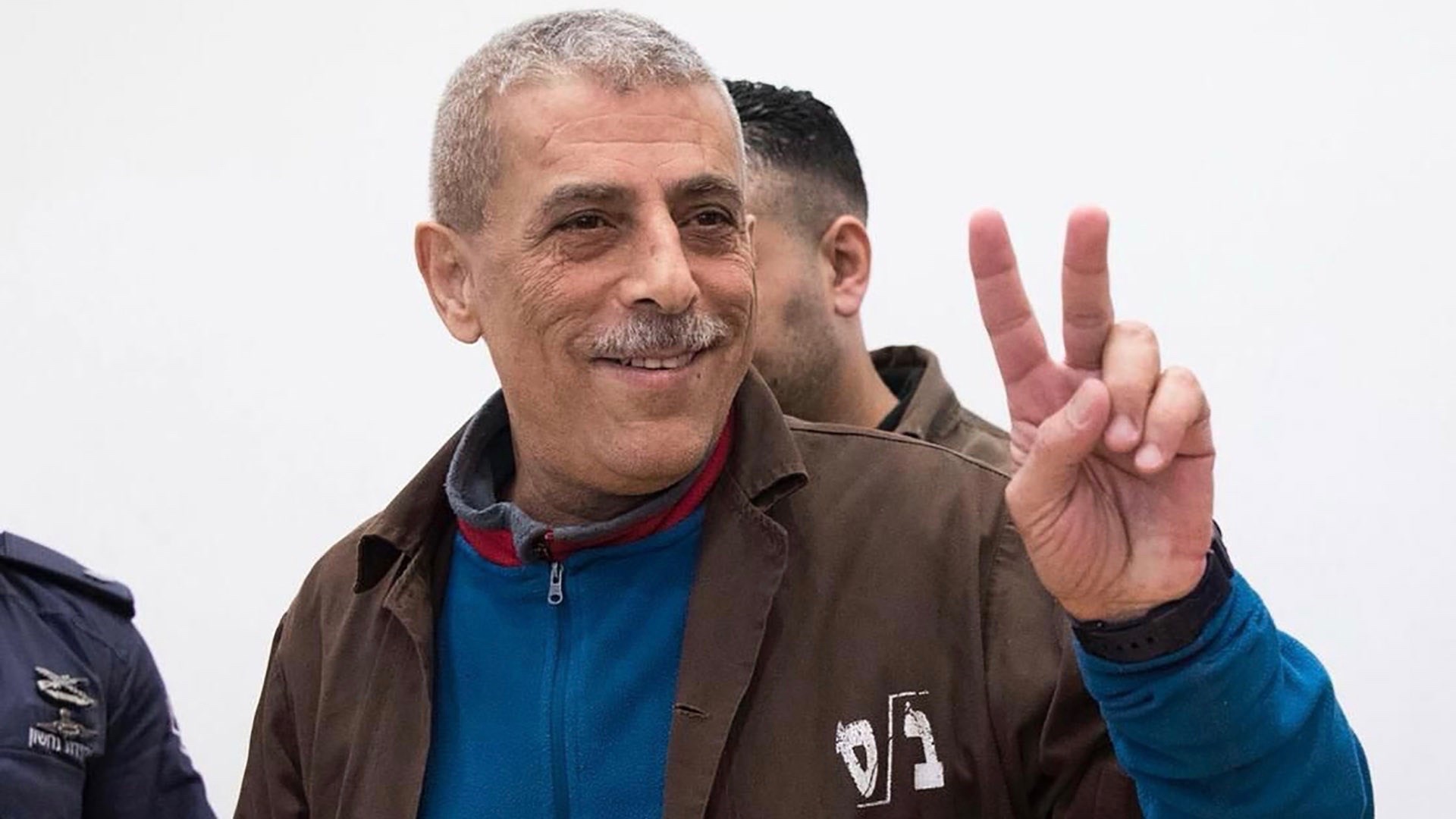

Palestinian prisoner Walid Daqqah dies in Israeli occupation prison

The Palestinian revolutionary spent 38 years in occupation prisons and was suffering from terminal bone marrow cancer and lung disease

After spending 38 years imprisoned by the Israeli occupation, the Palestinian revolutionary organizer and thinker, Walid Daqqah died at age 62. Daqqah was diagnosed with bone marrow cancer in December 2022 and also suffered from chronic lung disease. Activists and left groups maintain that Daqqah was killed by intentional medical neglect by Israeli prison authorities.

According to a statement released by Amnesty International less than a month ago calling for his release, “Since 7 October 2023, Walid Daqqah has been tortured, humiliated, denied family visits and has faced further medical neglect. During this period, he was transferred to hospital twice due to health deterioration.”

In the last year, Palestinian left groups and human rights organizations had intensified efforts to demand Daqqah’s release due to the systematic denial to adequate medical care by the Israeli occupation prison services. Additionally, Daqqah finished his original 37-year sentence in March 2023, but his release was blocked because in 2018 Israeli authorities charged him with attempting to smuggle mobile phones into prison and sentenced him for two more years in prison, knowing he was terminally ill.

On May 31, 2023, the Israeli prison service parole committee rejected the appeal for Daqqah’s early release, alleging that the matter was not within its powers, and shortly after, an Israeli court also rejected the appeal . At the time, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) said that not releasing Daqqah is “tantamount to a death sentence.” The group said that it holds “the Zionist occupation fully responsible for the repercussions of this decision, especially since the health conditions of the imprisoned leader Walid Daqqah are in a state of continuous deterioration, due to the continued policy of medical neglect, and the lack of appropriate diagnoses and treatments.”

Daqqah was first arrested by Israeli forces on March 25, 1986 and was given a 37-year prison sentence, accused of being involved in the murder of an Israeli soldier. According to a statement from the International Union of Left Publishers (IULP) calling for his release last year, Daqqah was subjected to “extra levels of the routine torture, abuse, and neglect that Palestinian prisoners face in the Occupation’s jails”. The network of left publishers called Daqaah “a voice of the people, a voice that the Occupation fears and hopes to silence.”

Daqqah became a father at age 57 after his sperm was smuggled out of prison.

In June 2023, Peoples Dispatch published an essay written by Palestinian writer Wisam Rafeedie about Daqqah’s historic resistance and struggle. Rafeedie wrote “The resisting prisoner does not need to prove their humanity. That is a moot point— they deserve to live it. It is the Zionist prison guard that lacks humanity in the face of the resisting prisoner. Walid has not only affirmed his humanity but has proven that his consciousness, like thousands of other prisoners, has not been seared. He has exposed Israel’s policy and practice of searing consciousness that targets prisoners.”

Read Wisam Rafeedie’s essay: The prisoner Walid Daqqah: a stubborn conscience that cannot be seared

Rafeedie, reflecting on his continued struggle even in the prisons of the occupation wrote, “Throughout all the stages of his life in prison, Walid has never relinquished his leading role in the prisoners’ movement…He was always committed to his role in the national struggle as an activist of high consciousness, unlike the handful of leaders that chose to play the role of the ‘Kapo’. Walid never stopped his sharp intellectual production, or literary writing for adolescents or building fraternity and camaraderie amongst his fellow prisoners who all bear witness to his character.”

After the news of Daqqah’s martyrdom was announced, a rally was called in the center of Ramallah to mobilize in anger against the medical neglect and treatment faced by Daqqah and the over 8,000 other Palestinian prisoners in occupation jails.

In a statement released on April 7, the PFLP lamented the loss of the revolutionary writer, theoretician, and organizer and wrote, “As the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine bids farewell to its comrade, the leader, thinker, writer, inspiration and great theoretician, it pledges to be loyal to his national, intellectual and front-line legacy, through which he made Palestine and the cause of its liberation his compass. Until his departure, he remained inhabited by Palestine, all of Palestine from its river to its sea. Glory to the great martyr of Palestine and humanity.”

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Don’t Overlook the Power of the Civil Cases Against Donald Trump

By David Lat and Zachary B. Shemtob

Mr. Lat writes about the legal profession. Mr. Shemtob is a lawyer.

For months now, the country has been riveted by the four criminal cases against Donald Trump: the New York state case involving hush-money payments to an adult film star, the federal case involving classified documents, the Georgia election-interference case and the federal election-interference case. But some have been postponed or had important deadlines delayed. The only case with a realistic shot of producing a verdict before the election, the New York case, involves relatively minor charges of falsifying business records that are unlikely to result in any significant prison time . None of the other three are likely to be resolved before November.

It’s only the civil courts that have rendered judgments on Mr. Trump. In the first two months of 2024, Mr. Trump was hit with more than half a billion dollars in judgments in civil cases — around $450 million in the civil fraud case brought by the New York attorney general, Letitia James, and $83.3 million in the defamation case brought by the writer E. Jean Carroll.

For Trump opponents who want to see him behind bars, even a half-billion-dollar hit to his wallet might not carry the same satisfaction. But if, as Jonathan Mahler suggested in 2020, “visions of Donald Trump in an orange jumpsuit” turn out to be “more fantasy than reality,” civil justice has already shown itself to be a valuable tool for keeping him in check — and it may ultimately prove more successful in the long run at reining him in.

The legal system is not a monolith but a collection of different, interrelated systems. Although not as heralded as the criminal cases against Mr. Trump, civil suits have proved effective in imposing some measure of accountability on him, in situations where criminal prosecution might be too delayed, divisive or damaging to the law.

To understand why the civil system has been so successful against Mr. Trump, it’s important to understand some differences between civil and criminal justice. Civil actions have a lower standard of proof than criminal ones. In the civil fraud case, Justice Arthur Engoron applied a “ preponderance of the evidence ” standard, which required the attorney general to prove that it was more likely than not that Mr. Trump committed fraud. (Criminal cases require a jury or judge to decide beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant committed a crime, a far higher standard.) As a result, it is much easier for those suing Mr. Trump in civil court to obtain favorable judgments.

These judgments can help — and already are helping — curb Mr. Trump’s behavior. Since Justice Engoron’s judgment in the civil fraud case, the monitor assigned to watch over the Trump Organization, the former federal judge Barbara Jones, has already identified deficiencies in the company’s financial reporting. After the second jury verdict in Ms. Carroll’s favor, Mr. Trump did not immediately return to attacking her, as he did in the past. (He remained relatively silent about her for several weeks before lashing out again in March.)

Returning to the White House will not insulate Mr. Trump from the consequences of civil litigation. As president, he could direct his attorney general to dismiss federal criminal charges against him or even attempt to pardon himself if convicted. He cannot do either with civil cases, which can proceed even against presidents. (In Clinton v. Jones , the Supreme Court held that a sitting president has no immunity from civil litigation for acts done before taking office and unrelated to the office. And as recently as December, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit made clear that even if the challenged acts took place during his presidency, when the president “acts in an unofficial, private capacity, he is subject to civil suits like any private citizen.”)

It may also be difficult for Mr. Trump to avoid the most serious penalties in a civil case. To appeal both recent civil judgments, Mr. Trump must come up with hundreds of millions of dollars in cash or secure a bond from an outside company. Although he managed to post a $91.6 million bond in the Carroll case, he initially encountered what his lawyers described as “ insurmountable difficulties ” in securing the half-billion-dollar bond he was originally ordered to post in the civil fraud case. An appeals court order last week cut that bond to $175 million — but if Mr. Trump cannot post this bond, Ms. James can start enforcing her judgment by seizing his beloved real estate or freezing his bank accounts. And even though it appears that he will be able to post the reduced bond, the damage done to his cash position and liquidity poses a significant threat to and limitation on his business operations.

Furthermore, through civil litigation, we could one day learn more about the inner workings of the Trump empire. Civil cases allow for broader discovery than criminal cases do. Ms. James, for instance, was able to investigate Mr. Trump’s businesses for almost three years before filing suit. And in the Carroll cases, Mr. Trump had to sit for depositions — an experience he seemed not to enjoy, according to Ms. Carroll’s attorney. There is no equivalent pretrial process in the criminal context, where defendants enjoy greater protections — most notably, the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination.

Finally, civil cases generally have fewer externalities or unintended consequences. There are typically not as many constitutional issues to navigate and less risk of the prosecution appearing political. As a result, civil cases may be less divisive for the nation. Considering the extreme political polarization in the United States right now, which the presidential election will probably only exacerbate, this advantage should not be underestimated.

David Lat ( @DavidLat ), a former federal law clerk and prosecutor, writes Original Jurisdiction , a newsletter about law and the legal profession. Zachary B. Shemtob is a former federal law clerk and practicing lawyer.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

An earlier version of this article misstated Arthur Engoron’s title. He is a justice on the New York State Supreme Court, not a judge.

How we handle corrections

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Credit card rates

- Balance transfer credit cards

- Business credit cards

- Cash back credit cards

- Rewards credit cards

- Travel credit cards

- Checking accounts

- Online checking accounts

- High-yield savings accounts

- Money market accounts

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Car insurance

- Home buying

- Options pit

- Investment ideas

- Research reports

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

One man’s gruelling trip through Putin’s prison system

- Oops! Something went wrong. Please try again later. More content below

For centuries, the West has been captivated by the brutality of Russia’s frozen detention centres, and prison literature from Dostoyevsky to Solzhenitsyn has nursed the fascination. The system’s global significance, whether in the mass release of dangerous prisoners to serve on Ukraine’s battlefields , the increased imprisonment of dissenters and journalists, or the death of opposition leader Alexey Navalny in a remote Arctic prison colony last month, has only spurred interest further.

The publication in English of The Prisoner, a 2013 memoir by former inmate Vladimir Pereverzin, is thus well-timed. Prior to his 2004 arrest, Pereverzin was no radical or dissenter; he had little in common with Navalny, Vladimir Kara-Murza, or other opposition figures jailed or even killed under Vladimir Putin ’s rule. He was a middle-level manager at Yukos, an oil and gas company owned by Mikhail Khodorkovsky , the oligarch who was once the richest man in Russia.

Khodorkovsky, however, fell afoul of Putin’s regime after campaigning for a freer society, and in 2003 he and his business partner Panton Lebedev were arrested. Pereverzin’s own arrest, the following year, seems to have been an attempt by Russian security services to persuade him to testify against his two former bosses. Having refused to do so, he was convicted of fraud, and sentenced to 12 years behind bars. (He ended up only serving seven of these before being released due to a change in the Criminal Code. He now lives in Germany.)

Much of The Prisoner, skilfully translated by Anna Gunin, focuses on the daily grind of Russian prison life. It’s repetitive, dull and for the most part undramatic – bar the occasional court appearance, cell search or talent contest – but Pereverzin adds colour through his depictions of the other prisoners.

These include Alexander Umantsev, an ethnic Russian from Chechnya, who “after witnessing first-hand how the Russian army had killed civilians and ripped open the bellies of pregnant woman, [had] embraced Islam and left to fight on the side of the Chechens”; and Yura, an HIV-positive drug addict and gangster convicted of attempted robbery and killing a policeman, whose brother and father were also imprisoned in different camps. This tapestry of characters come together to form a community in prison, sharing their food parcels and hosting birthday parties in cells.

Pereverzin assesses his cohabitors with a generally non-judgemental gaze, perhaps on account of the fact that Russia’s prosecution system has an acquittal rate of under 1 per cent, meaning that determining whether someone is innocent or guilty can be a difficult task. Pereverzin muses: “I’d hazard a guess that 30 per cent of all the prisoners are not guilty.”