Chapter 2 Introductory Essay: 1607-1763

Written by: W.E. White, Christopher Newport University

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the context for the colonization of North America from 1607 to 1754

Introduction

The sixteenth-century brought changes in Europe that helped reshape the whole Atlantic world of Europe, Africa, and the Americas. These events were the rise of nation states, the splintering of the Christian church into Catholic and Protestant sects, and a fierce competition for global commerce. Spain aggressively protected its North American territorial claims against imperial rivals, for example. When French Protestant Huguenots established Fort Caroline (Jacksonville, Florida, today) in 1564, Spain attacked and killed the settlers the following year. France, Britain, and Holland wanted their own American colonies, and privateers from these countries used safe havens along the coast of North America to raid Spanish treasure ships. But North America did not hold the gold and silver found in Spanish possessions in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Peru. In the end, Spain concentrated on these more profitable portions of its empire, and other European nation states began to establish their own claims in North America.

Europe’s political, religious, and economic rivalries were fought in both European wars and in a struggle for colonies throughout the Atlantic. England’s Queen Elizabeth I supported Protestant revolts in Catholic France and the Spanish Netherlands, which put her at odds with Spain’s Catholic monarch, Philip II. So did her support for English privateers such as Sir Frances Drake, Sir George Summers, and Captain Christopher Newport, who preyed on Spanish treasure ships and commerce. In 1584, Elizabeth ignored the Spanish claim to all of North America and issued a royal charter to Sir Walter Raleigh, encouraging him and a group of investors to explore, colonize, and rule the continent.

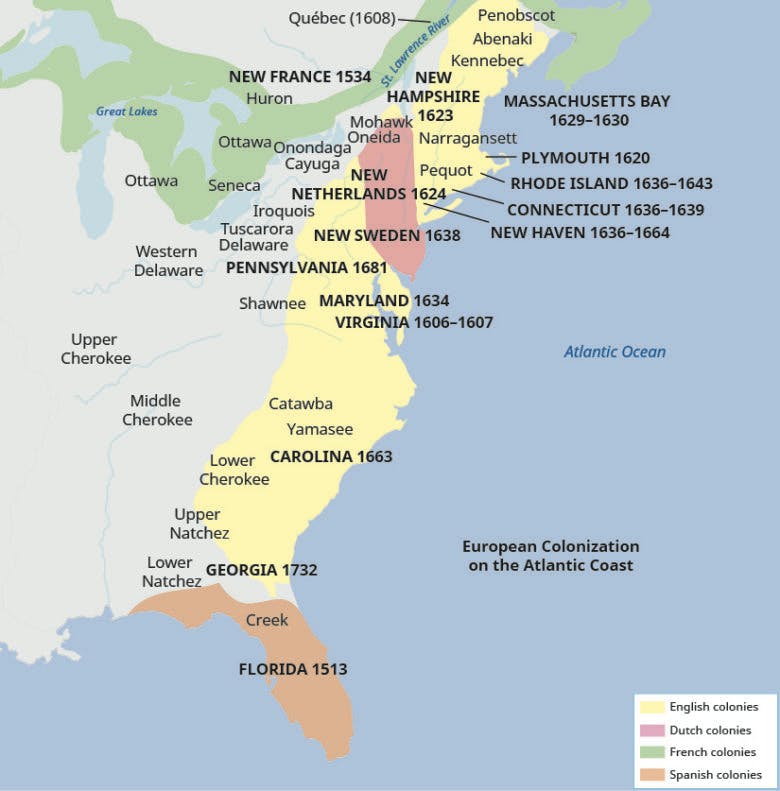

Sixteenth-century Europe was defined by the rise of nation-states and the division of Christianity due to the Protestant Reformation. Increased competition for wealth fueled by both developments spilled over into the New World, and by the early seventeenth century, Spain, Portugal, England, France, and the Netherlands all had a presence in North America.

England, France, and the Netherlands

By 1600, the stage had been set for competition between the European nations colonizing the Americas, and several quickly established footholds. The Spanish founded St. Augustine (in what is now Florida) in 1565. In 1607, English adventurers arrived at Jamestown in the Virginia colony (see The English Come to America Narrative).

The French established Quebec in what today is Canada, in 1608. Spanish Santa Fe (in what is now New Mexico) was founded in 1610. The Dutch established Albany (now the capital of New York) as a trading center on the Hudson River in 1614, and New Amsterdam (called New York City today) in 1624. English Separatists, now known as Pilgrims, established Plymouth Colony in 1620. Ten years later, in 1630, Puritans established the Massachusetts Bay Colony. European settlement grew exponentially. Seventeenth-century North America became a place where diverse nations—European and Native American—came into close contact.

By the 1650s, the English, French, and Dutch were well established in North America. French traders used the waterways to move ever deeper into the interior of the continent from their toehold in Quebec, trading with American Indians. French Jesuit priests lived peacefully with American Indians, learned their languages, recorded their society norms and customs, and worked to convert them to Christianity. Europeans traded imported goods to American Indians for beaver and other furs that brought high profits in Europe (see The Fur Trade Narrative). The American Indians’ economy and culture, and relationships with other native tribes, were changed by their new focus on the fur trade and by the metal tools and firearms the Europeans offered. By the mid-1700s, the French had claimed the St. Lawrence River Valley, the Great Lakes region, and the whole of the Mississippi River Valley.

By about 1650, the Atlantic coast had all been claimed by rival European powers. American Indians resisted European encroachment in various ways and with varying degrees of success. Struggles between American Indians and European settlers continued throughout the colonial period and beyond. (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

The Dutch settled the Hudson River Valley and established New Amsterdam. They began with a fur-trading site established in 1614 near what is today Albany, New York. It grew steadily during the next several decades, and historians estimate that by the 1660s, about nine thousand people inhabited the Dutch colony.

Britain’s settlement at Jamestown, Virginia, which started as an entrepreneurial joint-stock company, struggled initially. Investors in the Virginia Company of London sent settlers with supplies and instructions to discover profitable commodities for trade. They were also to search for the legendary Northwest Passage to Asia and its lucrative trade. Gold, of course, was at the top of the Virginia Company’s list, but precious metals and jewels eluded the settlers. There were a number of schemes for making money, but it was not until 1617, when John Rolfe exported his first four barrels of Orinoco tobacco—a sweet-scented variety he obtained from the Caribbean and planted in Virginia—that the Virginia economy took off. By 1619, settlers were enjoying private property rights and had elected the House of Burgesses, the first representative assembly in the New World. Tobacco drove the Virginia economy until the twentieth century. A land- and labor-intensive crop, tobacco led the settlers to spread out and establish isolated plantations where indentured servants and later slaves toiled.

Watch this BRI Homework Help Video on The Colonization of America for a review of the differences among the European colonies in the New World.

Native nations in North America sought the advantages of trade and the help of European allies to counter their enemies. But they also strove to control and resist the growing European presence on their land, using both diplomacy and military strikes. During the winter of 1609–1610, for example, Powhatan, an Algonquin chief and the father of Pocahontas, stopped trading with and providing food to the Jamestown settlers. His warriors laid siege to Jamestown and killed all who left the fort. During that winter, described by Englishmen as the “starving time,” Powhatan came close to ending the colony’s existence. Indians again waged war in the Second Anglo-Powhatan War of 1622 and the Third Anglo-Powhatan War of 1644, but by that time, the English presence in Virginia was too strong to resist (see The Anglo-Powhatan War of 1622 Narrative).

In the New Amsterdam and New England regions, Dutch and English traders wanted to control the lucrative fur trade. So did American Indian groups. The Pequot began expanding their influence in the 1630s, pushing out the Wampanoag to their north, the Narragansett to the east, and the Algonquians and Mohegan to the west. But they also came into conflict with the English of the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Connecticut colonies. Tensions came to a head in the Pequot War of 1637, when the Pequots faced an alliance of European colonists and the Narragansett and Mohegan Indians. The conflict ended in disaster for the Pequot: The survivors of the defeated tribe were given to their Narragansett and Mohegan enemies or shipped to the Bahamas and West Indies as slaves.

In these and other conflicts, American Indian nations and European nations competed among themselves and with each other for land, trade, and dominance. In the end, however, Europeans kept arriving and growing in numbers. Even more devastating was that American Indians had no immunity to European diseases like measles and smallpox, which caused 90 percent mortality rates in some areas. Epidemics spread across North America while Europeans steadily pushed American Indians farther west.

This sixteenth-century Aztec drawing shows the suffering of a typical victim of smallpox. Smallpox and other contagious diseases brought by European explorers decimated native populations in the Americas.

Enslavement of Africans was introduced early in the settlement of the Americas. In the early 1500s, Spain imported enslaved Africans to the Caribbean to meet the high demand for labor. The Dutch played a key role in the Atlantic slave trade until the 1680s, when the English gained control and allowed colonial shippers to participate. The Atlantic slave trade consisted of transporting captives from the west coast of Africa to the Americas in what became known as the “Middle Passage.” The Middle Passage was one leg of a profitable triangular trade in the Atlantic. Ships transported raw materials from the Americas to Europe and then shipped manufactured goods and alcohol to Africa, where they were used to purchase human beings from the West Africans. Ships’ captains packed their human cargo of chained African men, women, and children into the holds of the ships, where roughly 10 to 15 percent died.

Slaves were literal cargo on board ships in the Middle Passage, as this cross-section of the British slave ship Brookes shows. Ships’ decks were designed to transport commodities, but during the Atlantic slave trade, human beings became the cargo. This illustration of a slave ship was made in the late eighteenth century, after the American Revolution.

Despite high mortality rates, merchant financiers and slave-ship captains made significant profits. More than ten million Africans were forcibly brought to the Americas during the three-century–long period of the slave trade. Most were destined for Brazil or the West Indies. About 5 percent of the African slave trade went to British North America.

The first Africans in British North America arrived at Jamestown aboard a Dutch ship in 1619. Historians are not certain about their initial status—whether they were indentured servants or slaves. What is clear, however, is that over time, a few gained freedom and owned property, including slaves. During the next several decades, laws governing and formalizing the racial and hereditary slave system gradually developed. By the end of the seventeenth century, every colony in North America had a slave code—a set of laws defining the status of enslaved persons.

In Maryland and Virginia, enslaved persons provided labor for the tobacco fields. Farther south, in the Carolinas, indigo and rice were the cash crops. A southern plantation system developed that allowed wealthy landowners to manage many slaves who cultivated vast land holdings. Most whites were not large landowners, however. Many small farmers, businessmen, and tradesmen held one or two slaves, while others had none. Some paid a master for a slave’s labor in a system known as hiring out. By 1750, almost 25% of the population in the British colonies was enslaved. In Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina, the percentages were higher than in the North. In those southern colonies, slaves accounted for almost half the population. In South Carolina, almost two-thirds of the population were slaves.

In this 1670 painting by an unknown artist, slaves work in tobacco-drying sheds.

No one escaped the brutality of the slave system. Ownership of another human being as chattel property—like a horse or a cow—was often enforced by violence, and violence was always at hand, though masters also provided a variety of incentives such as time off or small gifts at Christmas. Masters and overseers used physical and mental coercion to maintain control. The whip was an ever-present threat and used with horrific results. A master was not faulted or legally punished for killing a rebellious slave. But perhaps one of the most powerful threats was the auction block, where fathers, sons, daughters, and mothers could be sold away from family. The children of enslaved mothers inherited the condition and were born into a life of servitude. Under the law, they were property a master could dispose of as he saw fit.

Enslaved people were treated like property and bought and sold on auction blocks. This ledger was used to track the sale of slaves sold in Charleston, South Carolina.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, most runaway slaves had no place to go. Before the American Revolution, some southern slaves ran away to Spanish Florida, but every British colony enforced slavery and slave laws, even as a few individuals and groups denounced the brutality of slavery and the slave trade (see the Germantown Friends’ Antislavery Petition, 1688 Primary Source). People of African descent could be arrested without cause anywhere they were strangers or unknown by the community. Even the few free blacks (probably no more than 0.5 percent of the African American population in 1750) stayed close to communities where they were known, where influential whites vouched for their free status. Law, society, and custom all suppressed the fundamental rights of blacks. This system, enforced by fear and violence, spawned revolts. Some were small; individuals ran away, broke tools, or damaged crops. Other revolts were larger and more violent, like the1739 Stono Rebellion in South Carolina (see The Stono Rebellion Narrative).

Watch this BRI Homework Help Video on the Development of Slavery in North America for a review of the main ideas covered in this section.

In 1620, a group of English separatists known as the Pilgrims settled at what today is known as Cape Cod Bay. The Pilgrims were “separatists” because they believed the protestant Church of England remained too close to Catholic doctrine, and they saw no other solution but to leave or separate from the church. Because they dissented from the established state church, they were persecuted, and they decided to leave England (see the Pilgrims to the New World Decision Point). The Pilgrims applied to the Virginia Company of London in 1619 and received a patent to settle at the mouth of the Hudson River. When they reached North America, poor sailing conditions and treacherous waters forced them to settle at Cape Cod Bay instead, where they established the colony they called Plymouth.

This 1805 painting by Michele Felice Corne depicts the landing of the Pilgrims in the winter of 1620. Note how the painter assumes that American Indians were watching the landing party.

In 1628, another group of English religious dissenters arrived in nearby Massachusetts Bay and settled there on behalf of the Massachusetts Bay Company. Like the Pilgrims who settled in Plymouth, these new emigrants believed the Church of England was too Catholic in its practices, but instead of separating, these migrants, known as Puritans , sought to purify or reform the Church from within. They hoped to establish a “city upon a hill,” as one of their leaders, John Winthrop, described it—a shining example to their brethren in England of a good and Godly community (see the A City Upon a Hill: Winthrop’s “Modell of Christian Charity,” 1630 Primary Source).

Puritans came to America in part for the freedom to practice their religion as they saw fit. Therefore, they enforced a strict religious orthodoxy in Massachusetts and Connecticut. When Roger Williams advocated a separation between church and government and preached freedom of conscience, he was forced to flee Massachusetts. In 1636, he founded Providence, Rhode Island, which became a haven for Protestant religious dissenters. Anne Hutchinson challenged the established Massachusetts Bay clergy on doctrine, an act all the more presumptuous coming from a woman. Banished from the colony, she sought refuge in Rhode Island (see the Anne Hutchinson and Religious Dissent Narrative).

Puritan society was torn in other ways as well. In the 1690s, a group of teenage girls accused members of the community of Salem (today Danvers, Massachusetts) of consorting with the Devil, beginning a period of mass hysteria known as the Salem witch trials, during which several residents were executed. The factors that led to the flurry of accusations were complex and may have included a belief in supernatural forces, England’s control over New England, and economic tensions that made the accusations believable. The hysteria ended only when town leaders themselves were charged with witchcraft and turned against the accusers, leading the newly appointed royal governor to declare the trials over (see The Salem Witch Trials Narrative).

Guidebooks for identifying witches were common in Europe and the colonies during the 1600s. This book, entitled Cases of Conscience concerning evil SPIRITS Personating Men, Witchcrafts, infallible Proofs of Guilt in such as are accused with that Crime. All Considered according to the Scriptures, History, Experience, and the Judgment of many Learned men, was written by Increase Mather, president of Harvard College and Puritan minister, in 1693.

Religion was a defining feature of other North American settlements as well. Cecil Calvert, Lord Baltimore, was an English noble and a Roman Catholic. He received a charter from King Charles I of England allowing him to establish the Maryland proprietary colony and giving him and his family full control of it. Lord Baltimore founded Maryland on religious toleration and provided a safe haven for English Catholics. The first colonists arrived in 1634 and settled at St. Mary’s City. Despite the colony’s 1649 Toleration Act, however, religious tolerance was short-lived. In the 1650s, in the wake of the English Civil Wars, a Protestant council ruled the colony and persecuted Roman Catholics (see The Founding of Maryland Narrative).

The American colonies offered a variety of religious experiences, including religious freedom, religious toleration, and established churches.

William Penn received a grant of North American land from King Charles II and founded the colony of Pennsylvania in 1681 as a haven for Quakers like himself (see the William Penn and the Founding of Pennsylvania Narrative). Quakers were another Protestant group that frequently clashed with the Church of England; Penn had been imprisoned for a time in the Tower of London for his religious views. He saw his proprietorship of Pennsylvania as an opportunity to provide a refuge for Quakers and others persecuted for their beliefs: a “holy experiment” (see the Penn’s Letter Recruiting Colonists 1683 Primary Source). The colony practiced religious toleration welcoming those of other faiths. Penn pledged to maintain just relations with American Indians and purchased land from the Lenape nation.

Penn also intended for the colony to be prosperous, with a diverse population specializing in a wide array of occupations. By the mid-1700s, Philadelphia was one of North America’s most prosperous and rapidly growing trading ports.

As colonies prospered and their populations grew, younger generations became increasingly secular, leading to tensions with traditional established churches. Between the 1730s and 1740s, a wave of religious revivalism known as the Great Awakening swept over the colonies and Europe (see The Great Awakening Narrative). Church services during this revival were characterized by passionate evangelicalism meant to evoke an emotional religious conversion. The Great Awakening was opposed to the rationalism of the Enlightenment and questioned traditional religious authority. Historians continue to debate the legacy of this period of religious and cultural upheaval (see the What Was the Great Awakening? Point-Counterpoint).

The British Take Control

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, the British consolidated their control over the eastern seaboard of North America. During the period 1675 to 1676 New England fought against the Wampanoag and their allies in what was called King Philip’s War. The conflict resulted in staggeringly high casualties on both sides and the physical expansion of colonies in New England. It helped convince the English government to revoke the Massachusetts charter and establish greater control over the colony (see the King Philip’s War Decision Point and the Maps Showing the Evolution of Settlement 1624–1755 Primary Source).

Some conflicts arose between the colonists and royal colonial administrations when officials prevented settlers from expanding into American Indians’ lands or failed to protect the settlers when they did. In 1676, western colonists were alarmed by a series of attacks by American Indians, and even more by the perception that Governor William Berkeley’s government in Jamestown was doing little to protect them. Nathaniel Bacon demanded a military commission to campaign against the Indians, but Berkeley refused. The refusal prompted Bacon and his followers—including small planters indentured servants and even slaves—to take up arms in defiance of the governor. Ultimately, the rebellion collapsed, and the English crown sent troops to Virginia to reestablish order. White farmers on smaller farms won tax relief and an expanded suffrage. With better economic conditions in England, fewer people migrated as indentured servants increasing the demand for enslaved people (see the Bacon’s Rebellion Narrative and the Bacon vs. Berkeley on Bacon’s Rebellion 1676 Primary Source).

European nations sought to control the flow of goods and materials between them and their colonies in a system called mercantilism. Mercantilism held that the amount of wealth in the world was fixed and best measured in gold and silver bullion. To gain power, nations had to amass wealth by mining these precious raw materials or maintaining a “favorable” balance of trade. Mercantilist countries established colonies as a source of raw materials and trade to enrich the mother country and as a consumer of manufactures from the mother country. The mercantilist countries established monopolies over that trade and regulated their colonies. For example, the British and colonial trade in raw materials and manufactured goods was expected to travel through British ports on British ships. The result was a closely held and extremely profitable trading network that fueled the British Empire. Parliament passed a series of laws called the Navigation Acts in the middle of the seventeenth century to prevent other nations from benefiting from English imperial trade with its North American colonies.

In the mid-1600s, the English went to war with the competing Dutch Empire for control in North America. The English seized New Amsterdam in 1664 during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. King Charles II gave it to his brother, the Duke of York, as a proprietorship, and the colony was renamed New York in the Duke’s honor, thus eliminating the Dutch toehold in North America. By the 1700s, therefore, there were only two major European powers in North America: Britain and France.

During the early eighteenth century, the French extended their influence from modern-day Canada down the St. Lawrence River Valley through the Great Lakes and into the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys. By 1750, French influence extended all the way down the Mississippi to Louisiana. Tensions were high as rivalry between France and Great Britain played out against the backdrop of the North American frontier (see the Albany Plan of Union Narrative).

European settlements in 1750 before the French and Indian War. (credit: “Map of North America in 1750” by Bill of Rights Institute/Flickr CC BY 4.0)

War with France

By 1750, both Britain and France claimed the Ohio River Valley. In 1753, the French began building a series of forts there on land claimed by British land companies such as the Ohio Company and the Loyal Company. Virginia’s lieutenant governor, Robert Dinwiddie, an investor in the Ohio Company sent a young Virginia militia major named George Washington to the Ohio country to warn the French to leave. They refused.

By the spring of 1754, the French were building another fort at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers (the site of modern-day Pittsburgh). Governor Dinwiddie sent Major Washington back with a contingent of troops. This time, Washington attacked the French and their Indian allies, then moved his force to Fort Necessity. Surrounded there by French, Shawnee, and Delaware fighters, he surrendered after a brief battle on July 4, 1754. This incident sparked the Seven Years’ War—or the “French and Indian War,” as it was known in America (see the Washington’s Journal: Expeditions to Disputed Ohio Territory 1753–1754 Primary Source).

The Seven Years’ War was mainly fought in Europe and North America, but engagements also occurred around the world (see the A Clash of Empires: The French and Indian War Narrative). In North America, American Indians continued their complex foreign policy, allying themselves in ways they hoped would allow them to dominate trade in their region. Many tribes sided with the French, but the Iroquois Confederacy and Catawba fought with the British. While British and colonial troops under the command of General Edward Braddock failed to capture Fort Duquesne, other forces moved northward and westward from New York to try to capture key French fortifications.

The campaign was a disaster for Britain. But in 1759, the British captured Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain and then defeated the French at Quebec and Fort Niagara. The following year, in Montreal, Governor Vaudreuil negotiated terms with British General Jeffery Amherst and surrendered. In 1763, France and Britain signed the Treaty of Paris, ending the French and Indian War and giving Britain control of all of North America east of the Mississippi River and of Canada. France was expelled from North America, and British colonists celebrated their victory. Never did these colonists feel more patriotic toward king and country. One reason was that they expected an opportunity to push farther westward as a result of their success in battle (see the Wolfe at Quebec and the Peace of 1763 Narrative).

These two maps show land holdings before (left) and after (right) the Seven Years’ War. What changes and continuities do you see in the balance of power on the North American continent?

The Path to Revolution

That same year, 1763, a coalition of Great Lakes, Illinois region, and Ohio region American Indians went to war against the British. The British emerged victorious, but the Indian nations demonstrated they would not easily submit. Led by an Ottawa man named Pontiac, American Indians warred with British soldiers and colonists across the frontier from Detroit to the Ohio River Valley.

The British believed they no longer had to court and negotiate with the American Indians. However, they wanted to end the costly conflicts between the colonists and American Indians. Thus, King George III issued the Proclamation of 1763 and temporarily prohibited settlements west of the Appalachian Mountains. Colonists protested. They believed they had the right to settle those lands. In the meantime, the British had incurred massive debts during the Seven Years’ War and wanted American colonists to pay a share in their protection. Parliament soon passed a series of restrictions and taxes on the colonies without their consent that eventually drove a wedge between them and the mother country.

By the mid-eighteenth century, Great Britain had defeated its rivals and emerged as the dominant force in North America. The cost of this dominance however would prove precarious for the relationship between Great Britain and its thirteen mainland colonies.

Additional Chapter Resources

- Mercantilism Lesson

- Colonial Comparison: The Rights of Englishmen Lesson

- Benjamin Franklin Mini DBQ Lesson

- Civics Connection: The Colonial Origins of American Republicanism Lesson

- Benjamin Franklin and the American Enlightenment Narrative

- Colonial Identity: English or American? Point-Counterpoint

Review Questions

1. Which of the following was not a reason that colonization became a major focus of European exploration in the Americas during the period from 1607 to 1763?

- Wars of religion in Europe caused many to look for an escape from religious persecution.

- Profits from cash crops such as tobacco provided economic incentives to establish colonies in the New World.

- Colonial possessions strengthened the prestige of European nations at home.

- Cooperative native populations invited colonization to increase trade.

2. Why did Spain value its interests in the Caribbean Mexico and Peru more than it valued colonies along the Atlantic seaboard in North America during the period from 1607 to 1763?

- The English had established colonies in North America long before the Spanish made any serious attempts to explore the northern continent.

- French settlers successfully fended off Spanish attacks on Fort Caroline in Florida.

- Resistance by native populations in North America tended to be more organized and successful than in South America.

- Spain focused its efforts on the possessions that were most likely to directly enrich the empire with gold and silver.

3. During the sixteenth century all the following provided an incentive for continued European exploration and colonization of the New World except

- the Protestant Reformation

- the rise of centralized governments in nation-states

- an appreciation of the cultural accomplishments of American and African societies

- competition for global commerce and trade

4. England’s Queen Elizabeth I created military and political tension with Spain when she

- refused to recognize Spanish claims to all North American territory

- established English colonies in Mexico and South America

- supported the Catholic Church over the oppositions of the Protestant reformers

- sanctioned privateers such as Walter Raleigh to attack English ships on behalf of Spain

5. The establishment of colonies in Jamestown by the English in Quebec by the French and in Albany by the Dutch is best explained by which of the following statements?

- Many European nations acquiesced to Spanish dominance in North America.

- American Indian populations in North America were successful in driving off Spanish conquistadors.

- Spain’s focus on the Caribbean Mexico and South America opened the door for other nations to establish footholds in North America.

- Cooperative efforts by European monarchs led to the successful colonization of North America.

6. The French successfully established territorial claims in

- present-day Florida

- the St. Lawrence River Valley

- the Hudson River Valley

- the Chesapeake Bay area

7. The formation of the House of Burgesses in Virginia indicates the English

- were focused on Christian missionary work sponsored by the crown

- wanted cooperation between their settlers and American Indians on a diplomatic level

- established a representative government in their North American colonies

- followed an economic policy focused on agriculture especially cotton

8. All the following were accomplishments of English settlements in Virginia by the early 1600s except

- the discovery of gold and other precious metals in North America

- election of the first representative government in the Americas

- existence of private property rights

- development and growth of a tobacco industry

9. The most significant American Indian group in New England that came into conflict with English settlers in Massachusetts in the 1630s was

- the Narragansett

- the Powhatan

- the Mohegan

10. Which of the following best describes the outcome and consequence of the Pequot War of 1636-1639?

- The Pequot successfully rallied neighboring American Indian peoples to join their resistance to English settlers.

- After a long struggle, the Spanish defeated the Pequot and solidified their claims to territory in present-day Mexico.

- The Pequot were defeated by the combined forces of the English the Narragansett and the Mohegan.

- The Pequot were successful in gaining concessions from the English settlers in return for support against the Narragansett people.

11. All the following were factors that led to the eventual end of American Indian resistance to European explorers and colonists in North America except

- the relatively few Europeans who came to the Americas

- divisions and competition among different groups of Native Americans

- the technological superiority of European weapons

- the American Indians’ lack of immunity to European diseases such as smallpox

12. Which best describes the impact European diseases had on Native American populations?

- Native American people were able to develop immunities to these diseases after exposure.

- Native Americans and Europeans suffered from an exchange of diseases they were not used to.

- Native populations were decimated throughout the Americas.

- Europeans were able to develop treatment for these diseases thanks to assistance from Native American populations.

13. What was the Middle Passage?

- The long-sought waterway through North America that would provide access to Asia

- The second leg of the profitable triangular trade route that transported humans from West Africa to the Americas to be sold as slaves

- The exchange of goods and services between the Americas and Europe

- The trade routes established by the French that connected Quebec to the Mississippi River

14. Which of the following statements regarding the African slave trade is most accurate?

- Most African slaves were sold to plantation owners in British North America.

- Brazil and the West Indies were the most common destinations for African slaves.

- Because of high mortality rates, the profits to merchants and ship owners from the slave trade were relatively low.

- The French imported slaves into their territories via the Mississippi River Valley.

15. What was the purpose of slave codes in the North American colonies?

- To provide a list of rights and protections for slaves

- To set laws defining the legal status of enslaved individuals

- To establish agreement between European powers on the logistics of the slave trade

- To develop better living conditions during the Middle Passage

16. Which of the following statements best reflects the reasons for slavery in North America?

- Labor-intensive crop production required cheap labor.

- A surplus of European laborers depressed salaries.

- The absence of economic opportunities limited Europeans’ motivation to settle in North America.

- Warfare between colonial rivals meant most colonists served as soldiers rather than as laborers.

17. Pilgrims were referred to as “separatists” because

- they had been forcibly removed to North America in retaliation for their political beliefs

- they sought to establish an independent nation separate from England

- they thought the Church of England could not be reformed and they needed to separate themselves from it

- they successfully petitioned for the creation of Rhode Island as a separate colony

18. Roger Williams founded the colony of Rhode Island after he was forced to flee Massachusetts because of his

- support of the Church of England

- status as a royally appointed governor of the colony

- treatment of neighboring American Indians

- disagreement with the established religious authorities

19. How did the establishment of Maryland contrast with that of the New England colonies?

- Maryland was initially founded by Dutch settlers.

- Maryland was less tolerant of religious differences than the New England colonies.

- Maryland was founded as a safe haven for persecuted Catholics.

- Maryland prohibited slavery.

Free Response Questions

- Explain the different types of labor systems that emerged in the settlement of New England and Virginia.

- Explain the motivations for English immigration to New England and to the Chesapeake regions in North America.

- Compare the motivations of England and France in their settlement in North America.

AP Practice Questions

“There goes many a ship to sea with many hundred souls in one ship whose weal and woe is common and is a true picture of a commonwealth or a human combination or society. It hath fallen out sometimes that both papists [Catholics] and protestants Jews and Turks [Muslims] may be embarked in one ship; upon which supposal I affirm . . . these two hinges that none of the papists, protestants, Jews, or Turks be forced to come to the ship’s prayers of worship nor compelled from their own particular prayers or worship if they practice any. I further add that I never denied that notwithstanding this liberty the commander of this ship ought to command the ship’s course yea and also command that justice peace and sobriety be kept and practiced both among the seamen and all the passengers . . . if any refuse to obey the common laws and orders of the ship . . . the commander or commanders may judge resist compel and punish such transgressors according to their deserts and merits.” Roger Williams Letter to the Town of Providence 1655

1. According to the excerpt from Roger Williams his Letter to Providence challenges what prevailing norm?

- Religious freedom

- Separation of church and state

- Religious orthodoxy

- Slave labor

2. Which of the following statements would a historian use to support the argument presented by Roger Williams in the excerpt provided?

- People have no obligation to follow law.

- Religious diversity is dangerous to a stable society.

- All government actions enforcing laws are illegitimate.

- People should be able to practice the religion of their choice.

“Wee must uphold a familiar commerce together in all meekeness gentlenes patience and liberality. Wee must delight in eache other; make other’s conditions our oune; rejoice together mourne together labour and suffer together allwayes haueving before our eyes our commission and community in the worke as members of the same body. Soe shall wee keepe the unitie of the spirit in the bond of peace . The Lord will be our God and delight to dwell among us as his oune people and will command a blessing upon us in all our wayes. Soe that wee shall see much more of his wisdome power goodness and truthe than formerly wee haue been acquainted with. Wee shall finde that the God of Israell is among us when ten of us shall be able to resist a thousand of our enemies; when hee shall make us a prayse and glory that men shall say of succeeding plantations the Lord make it likely that of New England . For wee must consider that wee shall be as a citty upon a hill. The eies of all people are uppon us.”

John Winthrop A Modell of Christian Charity 1630

3. This excerpt from John Winthrop’s sermon given while en route to the Massachusetts Bay Colony might be used by a historian to support the development of which of the following ideas in U.S. history?

- Limited government

- American exceptionalism

4. Which of the following best expresses the main idea of the excerpt provided?

- We must serve as an example to others.

- We will triumph over our enemies

- Others will praise us for our piety.

- We must endure persecution for our beliefs.

Primary Sources

The First Charter of Virginia: https://lonang.com/library/organic/1606-fcv/

Suggested Resources

Anderson Fred. The War That Made America: A Short History of the French and Indian War . New York: Penguin 2006.

Baker Emerson W. A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience . Oxford: Oxford University Press 2016.

Berkin Carol. First Generations: Women in Colonial America . New York: Hill and Wang 1997.

Berlin Ira. Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 2000.

Calloway Colin. New Worlds for All: Indians Europeans and the Remaking of Early America . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 2013.

Calloway Colin. The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2007.

Horn James. 1619: Jamestown and the Forging of American Democracy . New York: Basic Books 2018.

Kidd Thomas S. American Colonial History: Clashing Cultures and Faiths . New Haven: Yale University Press 2016.

Morgan Edmund S. American Slavery American Freedom . New York: W.W. Norton 2003.

Philbrick Nathaniel. Mayflower: A Story of Courage Community and War . New York: Penguin 2007.

Taylor Alan. American Colonies: The Settling of North America . New York: Penguin 2001.

Taylor Alan. Colonial America: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2012.

Williams Tony. The Pox and the Covenant: Mather Franklin and the Epidemic That Changed America’s Destiny. Naperville IL: Sourcebooks 2010.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

July 3, 2018

"The pursuit of happiness" means more in the Declaration of Independence than simply chasing a fleeting feeling.

3 ways to pursue 'thick' happiness

First, the most important thing is to realize that the happy life is about more than just me: my health, my wealth, my safety and security.

A robust understanding of human flourishing means it is for all and that means that our “pursuit” of happiness must transcend narrow nationalisms and thin tribalisms.

We would not permit, say, one political party to flourish and deny the chance for another to do the same. Or, to shift the imagery, we would not want our daughters to flourish but not our sons. Why, then, are we satisfied to let some neighborhoods in a city languish, or some schools in a district fail? Why are we willing to let some countries deteriorate?

Not because we are committed to the “unalienable right” of happiness, but only because we are selfishly committed to a narrow, individualized understanding of localized hedonism. But, as the positive psychology literature shows (and the biblical book of Ecclesiastes knows this too), more pleasure or more “stuff” will never bring true happiness and flourishing.

So, first and foremost, we have to think more globally, more organically. In the republic, all citizens should flourish, and in the global village, all persons should flourish — including those that aren’t (yet) citizens!

Second, thinking about happiness as a “global village” issue shows that human flourishing will only be achieved if we take better care of our world.

This is a truly transnational issue. All humans share this planet and therefore all humans — and all governments — must take responsibility for its care, particularly in redressing the lack of care that we have exercised for far too long. Without doing so, there will simply be no place for humans to flourish. Could it be any more simple?

Third, despite the important role played by governments and law, it is increasingly clear that important things like food, medicine and safe living conditions cannot always wait for the slow movements of governments.

Positive psychology has highlighted the crucial role of positive institutions , including — when they function at their best — families, workplaces and communities of faith. These must be ready to do the hard work of helping others flourish when the government proves ineffectual (as it often does).

When the government is effective and rightly functioning as one such positive institution, I firmly believe we will see far less “enforcement,” whether via the police or military, and far more “empowerment.” I myself believe these are related: more empowerment of people — facilitating their flourishing — will mean enforcement just won’t be needed anymore. It will become passé !

In the Bible, the prophet Isaiah has a vision along these very lines: a time where everyone will turn in their weapon and melt them all down to make more farm equipment (Isa 2:4). That is not a bad vision of thick happiness: for both humanity and the world!

Editor's note: Since this interview was originally published on June 30, 2014, it has consistently ranked among the most-read articles in the Emory News Center. As the Fourth of July holiday again approaches, we spoke with Professor Brent Strawn about why a "thick" understanding of "the pursuit of happiness" may be even more important in our current political climate. His additional answers appear at the end of the interview.

More than just fireworks and cookouts, the Fourth of July offers an opportunity to reflect on how our founders envisioned our new nation — including the Declaration of Independence's oft-quoted "unalienable right" to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."

But our contemporary understanding of "pursuit of happiness" is a thinner, less meaningful shadow of what the Declaration's authors intended, according to Brent Strawn, who teaches religion and theology in Emory's Candler School of Theology and Graduate Division of Religion.

"It may be that the American Dream, if that is parsed as lots of money and the like, isn't a sufficient definition of the good life or true happiness. It may, in fact, be detrimental," notes Strawn, editor of "The Bible and the Pursuit of Happiness: What the Old and New Testaments Teach Us About the Good Life." (Oxford University Press, 2012)

As we celebrate Independence Day, Strawn discusses what "pursuit of happiness" is commonly thought to mean today, what our founders meant, and how a "thick" understanding of happiness can be a better guide for both individuals and nations.

What 'happiness' means

The Declaration of Independence guarantees the right to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." What do you think the phrase "pursuit of happiness" means to most people who hear it today?

I think most people think "pursuit" in that phrase means "chasing happiness" — as in the phrase "in hot pursuit." This would mean that "the pursuit of happiness" has to do with "seeking it" or "going after it" somehow.

How does this differ from what our nation's founders meant when the Declaration of Independence was written?

It differs a lot! Arthur Schlesinger should be credited with pointing out in a nice little essay in 1964 that at the time of the Declaration's composition, "the pursuit of happiness" did not mean chasing or seeking it, but actually practicing happiness, the experience of happiness — not just chasing it but actually catching it, you might say.

This is demonstrated by documents that are contemporary with the Declaration, but also by the Declaration itself, in the continuation of the same sentence that contains "the pursuit of happiness" phrase. The continuation speaks of effecting people's safety and happiness. But the clearest explanation might be the Virginia Convention's Declaration of Rights, which dates to June 12, 1776, just a few weeks before July 4. The Virginia Declaration actually speaks of the "pursuing and obtaining" of happiness.

Why does this difference matter?

Seeking happiness is one thing but actually obtaining it and experiencing it — practicing happiness! — is an entirely different matter. It's the difference between dreaming and reality. Remember that the pursuit of happiness, in the Declaration, is not a quest or a pastime , but "an unalienable right." Everyone has the right to actually be happy, not just try to be happy. To use a metaphor: You don't just get the chance to make the baseball team, you are guaranteed a spot. That's a very different understanding.

Unalienable rights and the role of government

The next part of the sentence in the Declaration of Independence states "to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men." What does it mean to say, as you have written, that "the Declaration makes that obtaining and practicing of happiness a matter of government and public policy, not one of individual leisure or pleasure"?

I think it means, at least in part, that the happiness of which the Declaration speaks is not simple, light and momentary pleasure à la some hedonic understandings of happiness ("do what feels right"; "if it makes you happy…"). In the Declaration, "the pursuit of happiness" is listed with the other "unalienable rights" of "life" and "liberty." Those are qualities of existence, states of being. You are either alive or dead, free or enslaved.

Governments have something to say about those states by how they govern their citizens. If happiness is akin to life and liberty —as the Declaration and the original meaning of "the pursuit of happiness" say — then we are not dealing with momentary pleasurable sensations ("I'm happy the sun came out this afternoon") but with deep and extended qualities of life (the happiness one feels to be cancer-free, for instance).

According to the Declaration, the extended quality of happiness — what we might call the good or flourishing life — is or should be a primary concern of government. That means it isn't just about my happiness, especially idiosyncratically defined, but about all citizens' happiness.

If the founders' understanding of the "pursuit of happiness" does, indeed, have "profound public policy ramifications, and thus real connections to social justice," what are some specific examples of actions the government does or should take to secure that right today?

If we operate with a thick definition of happiness, then we have to think beyond simplistic understandings of happiness — as important as those are — and think about the good life more broadly. It may be that the American Dream, if that is parsed as lots of money and the like, isn't a sufficient definition of the good life or true happiness. It may, in fact, be detrimental.

Empirical research in happiness has shown that more money does not, in fact, make a significant difference in someone's happiness. The ultra-rich are not any happier than the average middle-class person (and sometimes to the contrary). So, moving beyond just the hedonic aspects of happiness, researchers have demonstrated the importance of positive emotions, positive individual traits (e.g., virtues), and positive institutions.

Governments could (and should, according to the Declaration) enable such things. To lift up just two examples that I think a lot about myself, the government needs to take action to guarantee all citizens' health and safety. A thick definition of happiness certainly includes many things — and sick people can in fact be very happy, can live flourishing lives — but positive institutions that keep us healthy and safe are, to my mind, specific and concrete ways the government can help a country's "gross national happiness" index (the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan actually measures its country's GNH!).

Food, medicine, safe living conditions — those are a few important building blocks of a happy life that governments can address.

Your book focuses on what the Bible teaches us about the pursuit of happiness, and you also note the current role of positive psychology as our society's primary arena for asking what "happiness" means. What is the most important lesson we can learn from both of those sources to help us understand and pursue happiness now?

Just this — that both the Bible and positive psychology give us a very thick understanding of the word "happiness." It is not about breakfast being yummy. It is about human flourishing, the good life, the obtaining and experiencing of all that can be glossed with the word "happiness," but only carefully and usually with a few sentences of explanation required to flesh it all out.

A thick understanding of "happiness" means that we have to think beyond only pleasurable sensations or think about redefining "happiness" altogether if "pleasure" is the only thing it means. If that's the only thing "happiness" means anymore, then we have a case of "word pollution" and we need to reclaim or redefine the word or perhaps use a different one altogether, at least for a while.

Redefining simplistic, thin definitions of "happiness" means that we come to terms that the happy life does not mean a life devoid of real problems and real pain. Those, too, are part of life and can even contribute to human growth and flourishing, which means they can and must be incorporated into a thick notion of happiness. As one positive psychologist has said: The only people who don't feel normal negative feelings are the pathologically psychotic, and the dead. Or, according to the biblical book of Psalms, the only people who live lives of constant comfort and pleasure are the wicked!

So, positive psychology speaks of post-traumatic growth — a kind of growth only experienced (and only able to be experienced) after grief. Or, to think about the New Testament, when Christians call the day Jesus was crucified "Good Friday," they certainly do not mean by that that it was a fun-filled day.

Instead, that is a very thick use of the word "good" and that is the kind of thick use that we must have when we speak of "happiness" — one that can encompass sorrow; that includes social concerns like food, health, and safety; and that is about experiencing the good, flourishing life, not just hoping for it.

Pursuing happiness in today's world

(Update) Does the current political climate in the United States impact the need for a “thick” understanding of the pursuit of happiness?

Since this article first appeared, I admit that I am even more struck now, in 2018, by the need for the government to help people attain — pursue and actually reach — key elements of human flourishing: food, safety, medicine and the like.

Politically, of course, people will differ on these issues and how they are best achieved, but it is clear that in recent years in this country we have had vicious political debates over things that are, at root, profoundly connected to these elements of happiness and who will gain access to them. Take, for example, the debate over universal health care. Or debates over gun violence and gun control. Or immigration. Each is complicated and multifaceted.

People who are for stricter immigration laws are likely concerned about their own safety and well-being. This is fully understandable. And yet, if happiness is a universal right, which is what the Declaration of Independence states, then that means we must consider the safety and well-being of others, too — including the safety and well-being of immigrants and refugees who would otherwise be turned away at our borders.

In this regard, the biblical story of Ruth the Moabitess is rather remarkable. Had she been turned away at the border, then Israel would have never had its greatest king, David, since he was her great-grandson. Or, to continue the lineage a bit further, without Ruth there is not only no David, there is also no Jesus, since, according to the New Testament, he is a direct descendant from Ruth, the Moabite refugee.

Or, to switch topics, one might like to stockpile weapons in order to feel safe, but one must ask about the effects of gun culture, the proliferation of guns, and if all that is, in fact, a truly safer way of life for the flourishing of all people. Statistics from other modern industrialized countries in the world that do not have the same gun obsession as America suggest, in fact, that it is not necessarily a safer way — or at least, such data indicate that the proliferation of weaponry is certainly not the only way to think about safety and well-being.

So, now, in 2018, I continue to think that the thickest and best definition of “the pursuit of happiness” means we must think about facilitating the achievement of others’ happiness, and not be inordinately or exclusively self-obsessed with our own.

Such a regard for others and their happiness would have certainly resonated with the early founders of our country, many of whom were themselves immigrants, and who were concerned not simply with their own well-being but with all those who would come after them in the United States.

The happiness of other, future generations was insured, as it were, in the Declaration and its claim regarding this “unalienable right.” Concern for other people’s happiness is also unquestionably true for the Bible where, among many examples, one might cite Jesus' instruction to his disciples: "No one has greater love than to give up one's life for one's friends" (John 15:13, Common English Bible).

I have to admit, however, that I am less sanguine now, in 2018, about the government’s interest in and ability to produce widespread happiness of the thickest variety for all people. The vast majority of what comes across the news scrawl these days seems remarkably parochial if not downright tribalistic. The “happiness” that is being sought is typically up for sale to the highest bidder with the most power (including firepower).

Such a vision of “happiness” is truly thin and can never lay appropriate claim to the Declaration’s grand vision of flourishing. But the Declaration’s grand vision is still there! And that gives me hope that good peoples throughout the world and throughout society and government may yet seek the greatest good for all humanity. May it be so!

- Graduate School

- School of Theology

- Religion and Ethics

Recent News

- Utility Menu

Text of the Declaration of Independence

Note: The source for this transcription is the first printing of the Declaration of Independence, the broadside produced by John Dunlap on the night of July 4, 1776. Nearly every printed or manuscript edition of the Declaration of Independence has slight differences in punctuation, capitalization, and even wording. To find out more about the diverse textual tradition of the Declaration, check out our Which Version is This, and Why Does it Matter? resource.

WHEN in the Course of human Events, it becomes necessary for one People to dissolve the Political Bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the Separation. We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness—-That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient Causes; and accordingly all Experience hath shewn, that Mankind are more disposed to suffer, while Evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the Forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future Security. Such has been the patient Sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the Necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The History of the present King of Great-Britain is a History of repeated Injuries and Usurpations, all having in direct Object the Establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid World. He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public Good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing Importance, unless suspended in their Operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other Laws for the Accommodation of large Districts of People, unless those People would relinquish the Right of Representation in the Legislature, a Right inestimable to them, and formidable to Tyrants only. He has called together Legislative Bodies at Places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the Depository of their public Records, for the sole Purpose of fatiguing them into Compliance with his Measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly Firmness his Invasions on the Rights of the People. He has refused for a long Time, after such Dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the Dangers of Invasion from without, and Convulsions within. He has endeavoured to prevent the Population of these States; for that Purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their Migrations hither, and raising the Conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the Tenure of their Offices, and the Amount and Payment of their Salaries. He has erected a Multitude of new Offices, and sent hither Swarms of Officers to harrass our People, and eat out their Substance. He has kept among us, in Times of Peace, Standing Armies, without the consent of our Legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a Jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution, and unacknowledged by our Laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large Bodies of Armed Troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from Punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all Parts of the World: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us, in many Cases, of the Benefits of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended Offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an arbitrary Government, and enlarging its Boundaries, so as to render it at once an Example and fit Instrument for introducing the same absolute Rule into these Colonies: For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with Power to legislate for us in all Cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People. He is, at this Time, transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the Works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy, scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous Ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized Nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the Executioners of their Friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic Insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction, of all Ages, Sexes and Conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions we have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble Terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated Injury. A Prince, whose Character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the Ruler of a free People. Nor have we been wanting in Attentions to our British Brethren. We have warned them from Time to Time of Attempts by their Legislature to extend an unwarrantable Jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the Circumstances of our Emigration and Settlement here. We have appealed to their native Justice and Magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the Ties of our common Kindred to disavow these Usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our Connections and Correspondence. They too have been deaf to the Voice of Justice and of Consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the Necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of Mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace, Friends. We, therefore, the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the World for the Rectitude of our Intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly Publish and Declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States; that they are absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political Connection between them and the State of Great-Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Signed by Order and in Behalf of the Congress, JOHN HANCOCK, President.

Attest. CHARLES THOMSON, Secretary.

The Pursuit of Happiness

What most people don’t know, however, is that Locke’s concept of happiness was majorly influenced by the Greek philosophers, Aristotle and Epicurus in particular. Far from simply equating “happiness” with “pleasure,” “property,” or the satisfaction of desire, Locke distinguishes between “imaginary” happiness and “true happiness.” Thus, in the passage where he coins the phrase “pursuit of happiness,” Locke writes:

“ The necessity of pursuing happiness [is] the foundation of liberty . As therefore the highest perfection of intellectual nature lies in a careful and constant pursuit of true and solid happiness ; so the care of ourselves, that we mistake not imaginary for real happiness, is the necessary foundation of our liberty. The stronger ties we have to an unalterable pursuit of happiness in general, which is our greatest good, and which, as such, our desires always follow, the more are we free from any necessary determination of our will to any particular action…” (1894, p. 348)

In this passage, Locke indicates that the pursuit of happiness is the foundation of liberty since it frees us from attachment to any particular desire we might have at a given moment. So, for example, although my body might present me with a strong urge to indulge in that chocolate brownie, my reason knows that ultimately the brownie is not in my best interest. Why not? Because it will not lead to my “true and solid” happiness which indicates the overall quality or satisfaction with life. If we go back to Locke, then, we see that the “pursuit of happiness” as envisaged by him and by Jefferson was not merely the pursuit of pleasure, property, or self-interest (although it does include all of these). It is also the freedom to be able to make decisions that results in the best life possible for a human being, which includes intellectual and moral effort. We would all do well to keep this in mind when we begin to discuss the “American” concept of happiness.

Read full passage from An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

A little Background

John Locke (1632-1704) was one of the great English philosophers, making important contributions in both epistemology and political philosophy. His An Essay Concerning Human Understanding , published in 1681, laid the foundation for modern empiricism, which holds that all knowledge derives from sensory experience and that man is born a “blank slate” or tabula rasa . His two Treatises of Government helped to pave the way for the French and American revolutions. Indeed, Voltaire simply called him “le sage Locke” and key parts of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America are lifted from his political writings. Thomas Jefferson once said that “Bacon, Locke and Newton are the greatest three people who ever lived, without exception.” Perhaps his greatest contribution consists in his argument for natural rights to life, liberty, and property which precede the existence of the state. Modern-day libertarians hail Locke as their intellectual hero.

Happiness as “True Pleasure”

In his An Essay Concerning Human Understanding , Locke attempted to do for the mind what Newton had done for the physical world: give a completely mechanical explanation for its operations by discovering the laws that govern its behavior. Thus he explains the processes by which ideas are abstracted from the impressions received by the mind through sense-perception. As an empiricist, Locke claims that the mind begins with a completely blank slate, and is formed solely through experience and education. The doctrines of innate ideas and original sin are brushed aside as relics of a pre-Newtonian mythological worldview. There is no such thing as human nature being originally good or evil: these are concepts that get developed only on the basis of experiencing pain and pleasure.

When it comes to Locke’s concept of happiness, he is mainly influenced by the Greek philosopher Epicurus , as interpreted by the 17th Century mathematician Pierre Gassendi. As he writes:

If it be farther asked, what moves desire? I answer happiness and that alone. Happiness and Misery are the names of two extremes, the utmost bound where we know not…But of some degrees of both, we have very lively impressions, made by several instances of Delight and Joy on the one side and Torment and Sorrow on the other; which, for shortness sake, I shall comprehend under the names of Pleasure and Pain, there being pleasure and pain of the Mind as well as the Body…Happiness then in its full extent is the utmost Pleasure we are capable of, and Misery the utmost pain. (1894, p.258)

Like Epicurus, however, Locke goes on to qualify this assertion, since there is an important distinction between “true pleasures and “false pleasures.” False pleasures are those that promise immediate gratification but are typically followed by more pain. Locke gives the example of alcohol, which promises short term euphoria but is accompanied by unhealthy affects on the mind and body. Most people are simply irrational in their pursuit of short-term pleasures, and do not choose those activities which would really give them a more lasting satisfaction. Thus Locke is led to make a distinction between “imaginary” and “real” happiness:

“ The necessity of pursuing happiness [is] the foundation of liberty . As therefore the highest perfection of intellectual nature lies in a careful and constant pursuit of true and solid happiness ; so the care of ourselves, that we mistake not imaginary for real happiness, is the necessary foundation of our liberty. The stronger ties we have to an unalterable pursuit of happiness in general, which is our greatest good, and which, as such, our desires always follow, the more are we free from any necessary determination of our will to any particular action…” (1894, p. 348)

In this passage Locke makes a very interesting observation regarding the “pursuit of happiness” and human liberty. He points out that happiness is the foundation of liberty, insofar as it enables us to use our reason to make decisions that are in our long-term best-interest, as opposed to those that simply afford us immediate gratification. Thus we are able to abstain from that glass of wine, or decide to help a friend even when we would rather stay at home and watch television. Unlike the animals which are completely enslaved to their passions , our pursuit of happiness enables us to rise above the dictates of nature. As such, the pursuit of happiness is the foundation of morality and civilization. If we had no desire for happiness, Locke suggests, we would have remained in the state of nature just content with simple pleasures like eating and sleeping. But the desire for happiness pushes us onward, to greater and higher pleasures. All of this is driven by a fundamental sense of the “uneasiness of desire” which compels us to fulfill ourselves in ever new and more expansive ways.

Everlasting Happiness

If Locke had stopped here, he would be unique among the philosophers in claiming that there is no prescription for achieving happiness, given the diversity of views about what causes happiness. For some people, reading philosophy is pleasurable whereas for others, playing football or having sex is the most pleasurable activity. Since the only standard is pleasure, there would be no way to judge that one pleasure is better than another. The only judge of what happiness is would be oneself.

But Locke does not stop there. Indeed, he notes that there is one fear that we all have deep within, the fear of death. We have a sense that if death is the end, then everything that we do will have been in vain. But if death is not the end, if there is hope for an afterlife, then that changes everything. If we continue to exist after we die, then we should act in such ways so as to produce a continuing happiness for us in the afterlife. Just as we abstain from eating the chocolate brownie because we know its not ultimately in our self-interest, we should abstain from all acts of immorality, knowing that there will be a “payback” in the next life. Thus we should act virtuously in order to ensure everlasting happiness:

“When infinite Happiness is put in one scale, against infinite Misery in the other; if the worst that comes to a Pious Man if he mistakes, be the best that the wicked can attain to, if he be in the right, Who can without madness run the venture?”

Basically, then, Locke treats the question of human happiness as a kind of gambling proposition. We want to bet on the horse that has the best chance of creating happiness for us. But if we bet on hedonism, we run the risk of suffering everlasting misery . No rational person would wish that state for oneself. Thus, it is rational to bet on the Christian horse and live the life of virtue , clearly, outlining a connection between spirituality, or religion, and happiness, with the perspective conditional on Christianity instead of religion or any other specific religion. At worst, we will sacrifice some pleasures in this life. But at best, we will win that everlasting prize at happiness which the Bible assures us. “Happy are those who are righteous, for they shall see God,” as Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount tells us.

In contrast to Thomas Aquinas , who made a pretty firm distinction between the “imperfect happiness” of life on earth and the “perfect happiness” of life in heaven, Locke maintains that there is continuity. The pleasures we experience now are “very lively impressions” and give us a sweet foretaste of the pleasures we will experience in heaven. Happiness, then, is not some vague chimera that we chasing after, nor can we really be deluded about whether we are happy or not. We know what it is to experience pleasure and pain, and thus we know what we will experience in the afterlife.

Happiness and Political Liberty

The relation between Locke’s political views and his view of happiness should be pretty clear from what has been said. Since God has given each person the desire to pursue happiness as a law of nature, the government should not try to interfere with an individual’s pursuit of happiness. Thus we have to give each person liberty: the freedom to live as he pleases, the freedom to experience his or her own kind of happiness so long as that freedom is compatible with the freedom of others to do likewise. Thus we derive the basic right of liberty from the right to pursue happiness. Even though Locke believed the path of virtue to be the “best bet” towards everlasting happiness, the government should not prescribe any particular path to happiness. First of all, it is impossible to compel virtue since it must be freely chosen by the individual. Furthermore, history has shown that attempts to impose happiness upon the people invariably result in profound unhappiness. Locke’s viewpoint here is prophetic when we look at the failure of 20 th Century attempts to achieve utopia, whether through Fascism, Communism, or Nationalism.

Locke’s view of happiness includes the following elements:

- The desire for happiness is a natural law that is implanted into us by God and motivates everything we do.

- Happiness is synonymous with pleasure, Unhappiness with pain

- We must distinguish “false pleasures” which promise immediate gratification but produce long-term pain from “true pleasures” which are intense and long lasting

- The pursuit of happiness is the foundation of individual liberty, since it gives us the ability to make decisions that are in our long-term best interest

- Since there is a diversity of natures, what causes happiness completely depends on the individual and his or her own experience of pleasure and pain

- The best bet would be to live a life of virtue so one can win everlasting happiness. Betting on a life of hedonistic pleasure is “irrational” given the prospect of infinite misery

- The pursuit of happiness is also the foundation of political liberty. Since God has given everyone the desire to pursue happiness as a natural right, the government should not interfere with anyone’s pursuit of happiness so long as it doesn’t interfere with other’s right to pursue happiness.

Further Readings