- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Books for Review

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Industrial Law Journal

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. a (reconstructed) legal insitutionalist view of labour markets, 3. migration and british labour markets from 1945 to the present, 4. conclusion.

- < Previous

Determining the Impact of Migration on Labour Markets: The Mediating Role of Legal Institutions

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Manoj Dias-Abey, Determining the Impact of Migration on Labour Markets: The Mediating Role of Legal Institutions, Industrial Law Journal , Volume 50, Issue 4, December 2021, Pages 532–557, https://doi.org/10.1093/indlaw/dwab030

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Critics of migration often claim that migrant workers displace local workers from jobs and apply downward pressure on wages. This article begins from the premise that it is impossible to understand the impact of migrant workers on labour markets without considering the functioning of law. Drawing on a reconstructed version of legal institutionalism, one that attends to the structuring influences of capitalist political economy and racism, this article considers the mediating role played by labour market institutions, such as collective bargaining and the contract of employment. An analysis of the historiography of migration to the UK since 1945 shows that labour market institutions have played a key role in influencing the inflow of migrant workers as well as the method of their incorporation into the labour market. In turn, migrant workers have intensified dynamics in the labour market that legal institutions have helped create, such as labour market segmentation. Migrant workers have also impacted the legal institutions themselves, either by being crucial actors in the creation of new legal institutions or by shaping the operation of existing ones.

Those who argue for reduced migration often do so on the basis of its assumed negative effects on the labour market. These minatory critics regularly claim that migration displaces local workers from jobs and drives down their wages. 1 Mainstream economists have tried to intervene in these discussions by analysing labour market data to determine the aggregate effects of migration on employment and unemployment rates and the wages of local workers. While acknowledging that the precise employment outcomes of migration will depend on factors such as domestic economic conditions and the skill level of migrants, most studies have found that migration has very little impact on employment outcomes, and a negligible impact on wages, although it is slightly more pronounced among ‘low-skilled’ workers. 2 Invariably, these studies are constructed as small case studies in which economists compare labour market data from geographical areas of high and low migration (‘spatial correlation’), or across skill groups that have experienced more or less competition from migrants (‘skill-cell correlation’), and then statistically parse out the effects of other factors. 3 Individual case studies sometimes provide mixed results since they are beset by definitional issues, limited by the availability of data and plagued by methodological disagreements. However, large-scale literature reviews can provide a fairly reliable picture because they iron out wrinkles that are inherent in small case studies. The Migration Advisory Committee (MAC), set up by the Labour government in 2007 to provide ‘transparent, independent and evidence-based advice to the government on migration issues’, has been asked to review the available economic evidence of migration on labour markets on three separate occasions. 4 MAC has concluded in 2012, 2014 and 2018 that the impact of migration on the labour market is small to non-existent. 5 What explains the findings of these surveys which confound simple economic logic about demand and supply? 6 Economists suggest that in the short term, whether migrants have a negative impact on jobs and wages depends on whether they have skills that substitute or complement those of existing workers. 7 In the longer term, economists point out that migrants add not only to labour supply, but also to labour demand. 8

While these studies provide a valuable perspective, labour lawyers should exercise some caution about simply accepting what mainstream economists tell about the relationships between migration and labour markets. For a start, these economic studies are based on assumptions about a prevailing state of equilibrium in labour markets, which is initially disturbed by migration but then eventually restored. Heterodox economists have long disputed that labour markets operate in this manner, instead emphasising their character as social institutions. Second, economists aim to predict the effects of migration by isolating the impact of migration from other factors using statistical tools such as regression analysis. However, these other factors, rather than clouding the issue, remain highly relevant—for example, how migration interacts with important components of labour markets, such as their labour laws, to produce particular effects, remains a critical question. Third, these studies treat migration as some sort of exogenous shock that needs to be analysed separately from the operation of labour markets themselves. In reality, migrants come looking for work in response to local labour market conditions. This means that migration is at the same time a factor that needs to be explained and also an explanatory factor in its own right. Fourth, economic studies provide only a snapshot on how migration has affected a specific splice of the labour market, while literature reviews provide an aggregate picture of the state of knowledge. What is urgently needed is an analysis of how specific labour markets affect migration, as well as an explanation of how migration impacts upon these labour markets.

Taking as an example the evolution of the British labour market in the period 1945 to the present, this article attempts to make visible the mechanisms by which migration and labour markets have interacted. I draw on a relatively new and inchoate theoretical framework, called legal institutionalism, to provide the theoretical scaffolding for this inquiry. 9 In the view of legal institutionalists, market dynamics are best studied by analysing the evolution of labour market institutions, such as the contract of employment and collective bargaining. Legal institutions are systems of rules inherited from the social environment and which shape the way that market actors behave. 10 In modern capitalist economies, legal institutions are made up primarily of legal norms supported by state-mandated enforcement apparatuses, but legal institutions also include cultural factors that shape the way that legal norms are given effect. If we foreground the role of legal institutions in our analysis of the historiography of migration to the UK since 1945, we can see that labour market institutions have mediated the relationship between migration and labour markets in several important ways. Since legal institutions are responsible for shaping the labour market, the need for migrant workers arises, in part, from their operation. Legal institutions also channel migrants seeking work into particular industries and jobs and determine their terms and conditions of employment. The entry of migrant workers in relatively large numbers—although never quite as high as in the frenzied imagination of migration’s critics—does impact upon labour markets despite economists’ assertations to the contrary. Migration deepens segmentation and can end up influencing the legal institutions themselves. In the following analysis, I use legal institutionalism as a methodological tool to study the relationship between migration and labour markets because it reveals the mediating function of law.

Before I proceed, the terms ‘migrant worker’ and ‘labour market’ require further explanation. Despite being in common usage, the meanings of these terms are not self-evident. Beginning with the concept of a labour market, it is clear that there are two main ways in which the labour market concept is deployed—a general labour market where employers and employees interact with each other and the price of labour is determined by competition (external labour market), and the firm-specific market where the price of labour is determined by administrative rules (internal labour market). 11 This article is mainly interested in the functioning of the external labour market, or more accurately, labour markets since markets can be simultaneously envisioned as sectoral, occupational, local, national and international depending on the actors in question. The term migrant worker —a decidedly contemporary term that I project back to study migration since the middle of the 20th century—is even slipperier. It usually refers to someone who is a national of one country but joins the labour market of another. 12 At the UK national level, a migrant worker has sometimes been defined as someone who is born overseas, while at other times, it is taken to refer to someone who is a national of another country. In either case, migrant workers comprise those who come in search of work but may also include those who enter under other streams—for example, family, study, or as asylum seekers—and eventually join the labour market. In this article, I mainly focus on labour migrants (that is, those who come in search of work), but will occasionally expand my analysis to include other categories of migrants. In some cases, I even include the progeny and descendants of migrants in my analysis because these are the terms in which the racialised debate is sometimes conducted. The inconsistency of meaning, together with the availability of data, make it difficult to accurately measure the number of migrant workers in the labour market at any point in time. While a range of statistical sources can be drawn upon—Long-Term International Migration and International Passenger Surveys, Migrant National Insurance Number Registrations, work permits issued etc.—individually, these sources only gesture at the overall picture.

This article proceeds in three main parts. In Section 2, I provide the key precepts of legal institutionalism and propose two important addendums that are necessary before it can be utilised to study the impacts of migration: situating legal institutions within broader trends in the capitalist political economy, and an account of how racism operates within institutions. Section 3 contains the substantive analysis of how legal institutions have mediated the relationship between migration and labour markets. I provide this history in two chronological periods (1945–80 and 1980–present) for reasons that will soon become clear. The focus of my discussion is how legal institutions have affected the flow and impact of migration, and how migration has in turn impacted upon the labour market and legal institutions. In the concluding section, I briefly summarise my main arguments.

There is nothing natural about describing the contracting of work for pay as a market, although it follows a general pattern in which we tend to think about the economic arena as a series of interlocking markets in which products and inputs are exchanged for money. For critical scholars, the reality of class relations is often concealed by seeing market interactions as underpinned by consensual, contractual relations. Even if we agree on the cautious adoption of the labour market as a unit of analysis, this still raises some questions about how we should conceptualise how markets arise and function. Economists from competing schools of thought hold vastly different views on these questions. According to the neoclassical school, for example, the demand for labour is determined by its marginal productivity and the supply is dependent on marginal utility. 13 Here we are introduced to the ‘methodological individualism’ that characterises the mainstream of economics today, as well as a theory of utility maximisation as the motivating force in human action. Institutional economics provide much better place and time sensitive conceptualisations of markets. One of the key themes of the institutionalists is a rejection of the idea of the utility-maximising economic agent. 14 Instead, for institutionalists, market relationships need to be understood with reference to social structures and discourses. The gravamen of the institutionalist contribution is the idea that institutions —that is, systems of rules inherited from our social environment—shape the way that market participants act. 15 In the act of doing, market participants then reproduce institutions so that they continue to endure in social life. In this view, markets vary considerably across space and time and the best way to study markets is to examine the institutions that underpin them in a society and their transformation over a particular period.

Modern institutionalism has now grown into a complex area of inquiry incorporating rational choice, historical, discursive and organisational institutionalism. 16 In this article, I draw particularly on legal institutionalism, a relatively recent branch of institutionalism. 17 Legal institutionalists emphasise the social rules that undergird markets and are chiefly interested in those rules that are supported by the power and authority of the state. Legal institutionalists do not claim that other social rules, such as those embedded in customary or cultural practices, are immaterial, but simply that they are unlikely to play a comparable role to formal law, which constitutes, shapes and reproduces markets in advanced capitalist societies. For the legal institutionalists, the centrality of law to markets mean that markets have no prior existence to the law. 18 Since markets are underpinned by a range of institutions (eg, money, contract etc.), it is not always simple to identify the relevant legal institutions to study. Following the work of Simon Deakin and Frank Wilkinson, I take the contract of employment (which includes common law principles as well as statutory regulation that prescribe minimum contracting terms) and collective bargaining as the two key labour market institutions. 19 The final legal institution that plays a major role in my analysis is an institution that helps manage the entry of workers into the labour market: migration law. While Deakin and Wilkinson included the duty to work—which in the modern era finds expression in social security law—as a major legal institution regulating entry to the labour market, given the space constraints of this article, my main focus will be migration law. There are, of course, complex relationships to disentangle between migration law and the duty to work, and their respective roles in regulating entry into labour markets, but this remains a task for another day. 20

Before legal institutionalism can be usefully utilised to study how migration impacts labour markets, two correctives are necessary. It is helpful to think of these correctives as operating on a ‘micro’ and ‘macro’ level, respectively. Turning first to the micro-level corrective, legal institutionalism often expresses a single-minded focus on legal norms as guiding human action at the expense of cultural ones which might shape the way that legal norms are given effect in particular situations. This is evident in the conceptualisation of labour markets advanced by legal institutionalists that tends to overlook how racism functions as a constitutive feature of labour markets. 21 Tracing the operation of racism is not merely an exercise driven by current political vogues, but rather critical to understanding how ‘real’ labour markets operate, especially when the issue of migration is under consideration. How then to account for racism’s role in constituting and structuring labour markets? The starting point in this analysis is to recognise that the relevant category of analysis is racism, not race, since racism produces race. 22 Racism is ideological in nature, and as Robert Miles and Malcolm Brown have outlined, it uses biological and/or somatic characteristics to socially differentiate particular populations. 23 Of course, emphasising the ideological character of racism is not to downplay the deeply material effects of racism. As theorists of race and colonialism often point out, the ideological content of racism is deeply informed by the racial ordering system that developed during the colonial period, although its modern manifestations show constant evidence of mutation. 24 If we marry legal institutionalism with an account of racism as an ideology, we can begin to uncover the causal mechanisms at play. We can think of racism as a miasma that pervades all market institutions, and therefore, influences the way that market participants give effect to legal norms in practice. In turn, by operationalising legal norms in all sorts of racially discriminatory ways, racial ideology is reinscribed in legal institutions and kept alive more broadly in society.

The macro-level corrective seeks to situate the legal institutions more squarely in the functioning of contemporary capitalism. Given their methodological commitment to understanding capitalism in a situated way, legal institutionalists have correctly tended to avoid developing universal, teleological principles to describe the progression of markets. Instead, legal institutionalists have tended to draw on various theoretical tools from the biological world to explain the evolution of legal institutions in a gradual, contingent and path-dependent way. 25 However, as a prominent institutionalist has recently argued, institutionalism needs to operate alongside theory of capitalist development. 26 I situate labour market institutions more firmly within ‘accumulation regimes’, which the French régulation school of economics traditionally describe as ‘ social and economic patterns that enable [capital] accumulation to occur in the long term between two structural crises ’. 27 According to these writers, configurations of social relations such as institutions have a direct relationship to the economy by helping to give effect and stabilise particular accumulation regimes. This does not mean that legal institutions simply reflect the needs of capital; they express their own histories, logics, technologies and techniques. However, accumulation regimes have a structuring function on legal institutions, particularly in the labour market. This article analyses migration to the UK from 1945 to 2020, a period that encompasses two different accumulation regimes—the period roughly from 1945 to 1980 is characterised by a ‘Fordist’ accumulation regime and the period from 1980 to present is characterised by a ‘post-Fordist’ accumulation regime. 28

The impacts of migration on labour markets are deep and variegated, and there are many ways to set out the narrative of British regulation from 1945. The periodisation that I adopt below is chronological, delineated by major shifts in British political economy and legal change. Roughly speaking, the first period (1945–80) was when migration to the UK was high in response to labour market gaps created by a high-growth economy, low unemployment and the needs of British industry. This period ends with growing legal restrictions on migration due to a racist backlash at home. The second period (1980–present) begins at the point when Britain started to experiment with a series of radical reforms to address major economic problems that had developed in the preceding decades. While the first two decades of this period were marked by relatively low levels of migration, the inflow of people began to climb from 2000 onwards in response to changes in the labour market precipitated by the Thatcherite reforms and continued under New Labour. This period ends with the passage of a new immigration system designed to restrict ‘unskilled’ immigration.

Writing about Britain’s post-war economic performance, one commentator observed that ‘for a quarter of a century or so after the Second World War the British people enjoyed full employment, no major recessions and the fastest rate of economic growth ever experienced on a sustained basis, as well as its most egalitarian distribution’. 29 These outcomes were the result of what is sometimes called a ‘Fordist’ regime of accumulation, characterised by combination of industrial production through vertically integrated firms, mass consumption, class compromise and the Keynesian welfare state. 30 The government recognised that the longevity of these developments required that sufficient workers could be found to fulfil the requirement for production. 31 To achieve this end, the government used a variety of methods to recruit workers from Europe, including resettling Polish soldiers who had served under British command and recruiting displaced persons through contract labour programmes such as ‘Balt Cygnet’ and ‘Westward Ho!’. By 1950, the population of ‘aliens’ (those not from the British mainland or its overseas territories) almost doubled to 430,000 from 239,000 in 1939. 32 In addition, without direct government intervention, a steady stream of migrants continued to arrive from Ireland in the period following the war—a source of reserve labour in England since the industrial revolution—and by 1970, this group formed the largest minority in Britain (approximately one million). 33

Another large pool of migrant labour arrived from the former Commonwealth countries in the Indian sub-continent and Caribbean. The change that facilitated their arrival had little to do with deliberate government action. In the post-war period, the UK was grappling with its post-imperial future. Keen to demonstrate the ongoing relevance of the British Empire, the Labour government passed the British Nationality Act 1948 , which converted the status of all those who had formerly been subjects into ‘Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies’. These citizens, whether born in the UK or overseas in a British colony, had the right to enter and reside in the UK and enjoyed all political, civil and social rights upon arrival. The 1948 Act also recognised as mostly equal the citizenship of the newly independent Commonwealth countries (eg, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) and older independent states (eg, Canada and Australia). 34 The proximate cause of the 1948 Act was that several of Britain’s former colonies—Canada, Australia and South Africa—were taking legislative steps to craft independent national identities by defining citizenship in ways that would dilute the meaning of British subjecthood. 35 Although never intended as a piece of immigration legislation, the passage of the 1948 Act had the effect of allowing a relatively large influx of immigration from the Indian sub-continent and Caribbean. 36 Between 1948 and 1962, around 500,000 racialised people (referred to as ‘coloured immigrants’ in public discussions at the time) arrived in Britain. 37 While some employers, such as London Transport, British Rail and the National Health Service, worked actively to recruit workers from these regions, some elements of the state worked behind the scenes to hinder this movement rather than promote it. 38

While the government may have created a facilitative legal framework opening the British labour market to migrants, it is important to recognise that this migration was driven primarily by domestic labour market conditions in Britain. Labour shortages were a major concern in the post-war recovery, which the government estimated to be between 600,000 and 1.3 million in 1946. 39 This situation was further exacerbated by the large numbers of Britons leaving the UK for greener pastures in other countries—between 1946 and 1965, over 1.8 million people left the UK, a great proportion financially aided by post-war migration schemes. 40 In their influential study, Stephen Castles and Godula Kosack argued that it was not only the lack of workers that was the driving cause of migration in post-war Western Europe, but also the structure of national labour markets. 41 According to these authors, in circumstances of low unemployment, indigenous workers were able to graduate to better remunerated and stable jobs, leaving gaps in unskilled manual roles that were difficult to fill. During the period from 1945 to 1970, unemployment rates generally remained between 1% and 3%, only moving beyond this range in 1972, and then, only slowly. 42 Offering higher wages for these undesirable jobs was not seen as a viable response because employers feared a decrease in export competitiveness and the government was worried about inflation. 43 Hence, migrant workers provided an ideal solution. In fact, a migrant workforce may have helped contribute to the competitiveness of British industry during this period by keeping a lid on wage inflation, eliminating production bottlenecks, and allowing the implementation of new work processes such as shift work. 44 Lending support to this thesis, it is clear that many of the racialised workers that arrived in the period following the war occupied semi-skilled and unskilled roles in industries such as the textile industry and in foundry works, or worked as cleaners, porters and kitchen hands in the expanding services sectors. 45 Notable features of this work include low pay, shift work, asocial hours, disagreeable working environments and low levels of upward mobility. 46 In the low-paid services sector, migrant workers were joined by female workers, then entering the labour market in increasing numbers. 47

The legal institutions of the labour market at the time facilitated this mode of migrant labour incorporation. Up until 1963, employers could contract with workers with little statutory constraint, and after that with only minimal regulation in the areas of notice of termination, redundancy and equal pay. 48 Since migration was left up to market forces to determine, the arrival of migrant workers closely tracked economic conditions in Britain and employer preferences. 49 The prevalent system of collective bargaining also did nothing to ameliorate this differential access to the labour market and usually exacerbated it. In the post-war period leading up to the 1970s, collective bargaining consisted of a variety of overlapping agreements at the level of industry, company, and plant. 50 Generally speaking, industry-wide agreements between employer association and unions regulated rates of pay (which acted as minima in practice), while relatively informal plant-level agreements made between local shop stewards and managers regulated a whole host of matters such as incentive pay, overtime and work processes. 51 These negotiations took place in the absence of detailed legal regulation, although not entirely without legal support. 52 Due to the fact that racist ideas had a strong hold over the white working class during this period, informal plant-level agreements often disadvantaged racialised workers—for example, it was common for shop stewards to negotiate ‘colour quotas’, rules prioritising racialised workers for redundancy or allow shift work as long as it only affected migrant workers. 53 Even when shop stewards were not directly colluding with management to implement discriminatory arrangements, there was a general lack of awareness or failure to acknowledge the particular circumstances faced by racialised workers. 54 The way in which the two central labour market institutions functioned during this period demonstrates how interaction of cultural and legal norms manifested in discriminatory outcomes. On the contract of employment, employer prejudice determined who was offered work and on what terms. With regards to collective bargaining, racism among employers and union actors had very real effects in terms of excluding migrant workers from good jobs and promotion.

From the 1960s there was a noticeable hardening of public attitudes towards unskilled immigration from the Indian sub-continent and Caribbean. We can locate some of this shift in attitude within changing material conditions. Although far less severe than the economic deterioration that Britain was to experience in the 1970s, the 1960s were characterised by various economic malaises including stagnation, balance of payment issues and a return to mass unemployment. 55 Rising racial tensions, fomented by racist groups and opportunistic politicians, also played their part. 56 The Conservative government, later supported by Labour, responded by progressively passing legislation to restrict immigration from the New Commonwealth. The first piece of legislation, which was passed in 1962, guaranteed entry to those who held a passport issued by a dependency government (which excluded India and Jamaica, which were the source of most of the immigration) or those who could obtain a work voucher from the Ministry of Labour. Work vouchers were offered for those who had pre-arranged employment or skills/occupations considered to be in short supply. The immigration control had an immediate effect, reducing the number of racialised workers from 136,400 in 1961 to 57,046 in 1963. 57 Further restrictions on vouchers were introduced in 1965, and 1968, 1969 and 1971. 58 The 1971 legislation signalled a particularly stark break with the relatively liberal immigration regime of the prior period because it ended the right of Commonwealth citizens to enter the country unless they had a parent or grandparent born in the UK. The 1968 and 1971 legislation were introduced specifically to prevent—as it turned out unsuccessfully—settlement by South Asians who had been expelled from Kenya and Uganda respectively. 59 Work permits for semi-skilled and unskilled jobs were also no longer issued. 60 This signalled a move away from a system of free mobility to a contract labour system, which tied workers’ entry directly to labour market conditions.

One further development from this period ought to be mentioned. The 1970s also saw an increase in labour organising among racialised workers, particularly among female migrant workers. 61 The most prominent example was the 1976 strike at the Grunwick photo processing plant led by a group of determined South Asian women, which galvanised national support from workers and unions. 62 However, not all of the activism by migrant workers in this period fitted the general mould of action that we would usually associate with labour politics. There was also a surge in activism in the community, including among second-generation migrants. 63 This form of activism was to have important consequences for the way in which access to the labour market was regulated. Mobilisation by community organisations was crucial in the government passing the Race Discrimination Act 1965 and subsequently strengthening the legislative framework to cover discrimination in the private sphere (employment, housing and service provision). 64 In this instance, grassroots pressure coincided with the Labour Government’s stratagem to present racial equality legislation as the quid pro quo of immigration restriction. 65 Social movement pressure was also a significant factor in extending coverage to ‘indirect discrimination’ in 1976, an innovation introduced by the Sex Discrimination Act’s passage a year earlier. While racial discrimination legislation was to have disappointing results overall, 66 these legislative measures did have some effect in improving labour market access for racialised workers by allowing the norm of racial equality to radiate throughout society. 67 Equally importantly, some of the institutional innovations pioneered by the now-defunct Commission for Racial Equality, for example its strategy of initiating proactive investigations, have continued to influence the operation of the Equality and Human Rights Commission today. 68

B. 1980–Present

Margaret Thatcher’s election as Prime Minister on 4 May 1979 marked the beginning of a new era in Britain. The main elements of the Thatcherite political economy are by now well known. Chief among them was a decisive move towards monetarism in macroeconomic policy-making, 69 massive changes to the operation of the financial sector, 70 and public-sector reform. 71 Another key aspect of the Thatcherite agenda was reforming the labour market to conform with a particular vision of free exchange between employer and worker. Paul Davies and Mark Freedland argue that the government was driven by two related goals: ensuring that the labour market could operate flexibly and reducing the power of trade unions that were seen to impose collective restrictions. 72 The powers of trade unions were attacked by imposing procedural constraints on taking strike action (eg, introducing secret balloting requirements), placing severe restrictions on various forms of activity that enhanced the countervailing power of organised labour (eg, closed shop/union membership agreements, secondary action, picketing) and a retreat from various corporatist arrangements that accorded unions an important role in the nation’s economic policy-making process. These transformations were brought about not only by changes to labour law (reducing the scope of the trade union immunities from common law liability), but also by selective amendments to social welfare and criminal law. 73 Given dispensation by the government and reassured that the large numbers of workers joining the ranks of the unemployed would strengthen their bargaining position, private sector employers were quick to take advantage of the situation. They did so by restructuring their operations and by beating back union efforts to engage in collective bargaining. 74 In 1979, over 80% of the workforce had been covered by a collective agreement, after almost two decades of Conservative rule, that number had dropped to less than half of that figure. 75 These labour law changes marked the advent of employment relations based on ‘flexibility’, work intensification and decline in the standard model of employment, which some have described as a ‘post-Fordist’ regime of accumulation. 76

The impacts of this series of changes were profound, leading to a sudden spike in unemployment, which peaked at 13% in 1982 and remained higher than 6% until 1990. 77 These labour market transformations had an enormous impact on migrant workers, including those who had been born in the UK but were nevertheless racialised as outsiders. Deindustrialisation and privatisation led to the gradual disappearances of internal labour markets where workers could join a firm and hope to advance through seniority. 78 This process was also hastened by firms increasingly outsourcing or contracting out ‘core’ functions, and those employed in these new entities were often drawn from the external labour market. 79 While migrant workers did not generally benefit from the operation of internal labour markets due to their exclusion through plant-level agreements, the erosion of internal markets meant that competition increased in external labour markets that were now separated into a ‘core’ segment characterised by job security and mobility, and a ‘secondary’ segment typified by insecure and contingent work. 80 Competition for jobs in the secondary labour market had always been fierce under conditions of high unemployment, but the addition of workers previously employed in firms that relied upon stable models of employment relations, and those who found themselves newly unemployed, intensified competition. Survey data from the period show that migrant workers were disproportionately represented among the unemployed, which means that some of the competition in secondary labour markets was between different groups of migrant workers. 81

This is the context in which additional migration during the 1980s and 1990s needs to be understood. Migration under free movement from the European Economic Community (and European Union after 1993) did not have much of an effect given the entity’s small membership at that time and the similarity of economic conditions with the UK’s. 82 Accordingly, when the government passed the Immigration Act 1988 to ensure that workers from the EEC did not need permission to enter or remain in the UK, immigration did not increase significantly. One of the early actions of the Thatcher government in the field of immigration was to introduce the British Nationality Act 1981 , which finally sundered the concept of citizenship from the Commonwealth and linked it firmly to the British nation. While the legislation retained a quota for work permits from the Commonwealth, this was restricted to 5,000 per year. 83 Over the course of the decade, the number of work permits granted gradually crept up, and by 1996 there were roughly 20,000 work permits, but a significant portion of these went to workers in professional and managerial roles (approximately 70%). 84 Many of these work permits were granted to citizens of the USA and Japan, which were Britain’s major trading partners outside the European Community at the time. 85 It should be noted that non-labour flows of migration continued to rise during this period—for example, political turmoil in countries such as Sri Lanka and Somalia in the 1990s saw a sharp increase in those seeking asylum—and many of those who were ultimately granted refugee status joined the labour market. 86

The Blair government that assumed office in 1997 was committed to continuing significant parts of the agenda that characterised British political economy under the previous Conservative government. 87 Influenced by ‘Third Way’ thinking that emphasised the competitiveness of enterprises along with the equal opportunity and social inclusion of workers, but also never entirely constrained by this philosophy, the Labour government (self-described as ‘New Labour’) retained significant aspects of labour market regulation. 88 New Labour did make some impact and the broad outlines of the employment and labour law reforms that Labour went on to enact can be found in a 1998 White Paper titled ‘Fairness at Work’. 89 The White Paper promised several new rights for individuals, including a new minimum wage, a shorter qualifying period to bring an unfair dismissal claim, working time regulation and an extension of parental leave entitlements. In the case of working time and parental leave, the government was seeking to implement EU-level obligations. In the area of collective bargaining, Labour left intact the basic architecture of the previous government’s draconian anti-union legislation (ballots before strikes, and prohibition of mass/flying pickets and secondary action) but did introduce a new statutory procedure for ascertaining whether majority employee support existed for collective bargaining within a particular workplace. 90 The intention behind New Labour’s labour market regulation was to facilitate the continuation of the post-Fordist regime of accumulation.

These arrangements deepened labour market segmentation in a number of ways and migration became a solution for many of the problems generated by these developments. Flexible production through outsourcing, for example, increased the number of workers subject to the highly competitive secondary segment of the labour market. Equally, the new employment standards stabilised a set of status-based distinctions (agency work, part-time, fixed term etc.) which operated to stratify and fix into place a variety of distinctions in the labour market. 91 Along with other dynamics such as under-investment in training, increasing use of technology by employers and the general immobility of local labour due to social ties, this generated a need for migrant workers at both the ‘high skilled’ and ‘low skilled’ end of the labour market. 92 During the period of New Labour, employers were able to satisfy this demand through a variety of paths. New Labour’s general attitude towards migration was that it could be managed to deliver positive economic outcomes, which explains its relatively relaxed and open attitude towards labour migration. 93 The main avenue was through EU free movement, which since the accession of the ‘EU-8’ countries in 2004, and Bulgaria and Romania three years later (‘EU-2’ countries), has provided a steady stream of workers into low-skilled occupations in industries such as hospitality, transport & storage, manufacturing and agriculture. 94 Some booming sectors, such as construction, looking to benefit from weaker labour rights in some of the newly acceded states, imported workers under the EU’s posted worker regime. 95 Workers from non-EEA countries could also enter the country via a range of mechanisms including by obtaining a work permit, as Working Holiday Makers, under the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme, Sector Based Schemes (2003–2008), or the Highly Skilled Migrants Programme (2002–08). 96 From 2008, a ‘Points-Based System’ (PBS) was introduced to replace a number of the routes of entry for non-EEA migrants. 97 Work permits, and the PBS that superseded it, provided workers for sectors such as IT, finance and education. 98 By the end of the decade, nationals from India, USA, China, Japan and Australia were generally the top users of this route. 99 It is important to note that unlike the migration from the former Commonwealth during the 1945–80, this second significant wave of migration—the overall migrant population nearly doubled between 2005 and 2017, rising from 5.3 million to 9.4 million— 100 occurred during a period of relatively high unemployment (between 2000 and 2016, unemployment stubbornly remained at close to five percent or above). 101 So, rather than labour shortages, the segmented labour markets produced by the Thatcherite reforms and continued by New Labour created the conditions for the entry of migrant workers during this period.

How did labour market institutions channel this new influx of workers into particular industries and jobs? The answer to this question is complicated and requires us to consider the operation of labour market institutions in which racism is an entrenched feature. Many of the highly skilled workers that entered during this period did so under EU free movement or work permits. These workers were motivated to choose particular jobs and remain in them either through high wages/good working conditions, tied visas, or a combination of the two. Time-bound, employer-tied visas mean that workers are less likely to challenge their employer because they fear they will be deported, which can produce servile employment relations in the labour market. 102 In contrast, low-skilled workers entering the UK under EU free movement (primarily from E-8 and EU-2 countries) were guided into particular jobs and kept there through labour market institutions in which racism was an embedded feature. Alana Lentin has pointed out that a new form of ‘xenoracism’, directed against Eastern Europeans, has taken root in Britain, meaning racism that is based on perceived cultural differences rather than simply being colour-coded. 103 Given the challenge of enforcing equality norms contained in anti-discrimination law at the point of recruitment, the contract of employment continued to provide employers with almost complete discretion in deciding which jobs to offer workers as well as their working conditions once employed. There is ample evidence that some employers prefer hiring migrant workers for low-wage jobs because they expect that these workers will have lower expectations around wages, temporal rhythms and the place of work; employers, of course, rarely explicitly stated this view, instead choosing to express their preferences in terms of statements about ‘superior work ethic’. 104

Once migrant workers have begun to work in the secondary segment through the sorting function of legal institutions, they can soon become entrenched within this segment. This is because of two dynamics within legal institutions concerning their operation in relation to migrants. The first dynamic relates to the way in which legal norms can interact to reinforce precarity for migrant workers. Take for example the protection against unfair dismissal, which is the primary means for workers to attain a measure of job security in the labour market. The Employment Rights Act 1996 requires that an employee has served a minimum of 2 years’ continuous service before accruing this right, which for some migrant workers presents a particular difficulty because of the operation of time-limited of visas or their employment in temporary roles with irregular hours. 105 Another example is the way in which the courts can deem contracts ‘illegal’, and therefore unenforceable when it comes to claiming employment rights, in circumstances where workers are ‘illegally’ working under s 34 of the Immigration Act 2016. 106 This population is estimated to be between 800,000 and 1.2 million in the UK; 107 a portion of these workers might have commenced work with the proper authorisation but lost it due to a variety of administrative reasons. The second dynamic relates to the way in which employment rights are enforced in Britain. A panoply of enforcement agencies (HRMC, HSE, GLAA, EAS) that are supposed to uphold employment standards have trouble fulfilling their mandates due to under resourcing, lack of coordination among agencies, and absence of specific strategies to target migrant workers. 108 This means that workers are required to enforce their own individual rights by bringing claims in the Employment Tribunal system, and individual enforcement of rights tends to be especially low among low-wage migrant workers. 109 The near absence collective bargaining in the industries in which migrant workers were employed means that unions, now predisposed to observe anti-racism norms, have not been able to ameliorate some of these effects. The segmentation of the labour market and the employment of migrants in the secondary segment has a self-reinforcing tendency. The gradual deterioration of working conditions leads local workers to eschew these jobs, and employers look to migrant workers as a substitute workforce, developing symbiotic relationships with labour contractors or migrant/ethnic networks to fill these positions. This dynamic is visible in a number of sectors, such as food processing, 110 hospitality 111 and social care. 112

Since the UK’s exit from the European Union, the government has implemented a new immigration system, which represents a radical break from free movement that characterised the previous regime. This system has been in place since 1 January 2021. At the heart of the system is an expansion of the Tier 2-visa route. Applicants must have a job offer by an approved sponsor that pays above the minimum salary level, which is the higher of £25,500 or a stipulated ‘going rate’ (or £20,480 in certain circumstances), a job at least at the intermediate skill level (RFQ3 or above), and English language skills. As Jonathan Portes has recently observed, the new immigration system represents a major liberalisation for non-EU migrants, since about half of all full-time jobs would now qualify someone for a Tier 2 visa. 113 The visa requirements in essence prevent so-called low-skilled migration, although sector-specific alternatives might be rolled out such as the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Pilot programme designed for the agricultural sector. Employers in the secondary segment employing low-wage and precarious workers are likely to be lose out by these changes, and there is already some evidence of this in sectors such as hospitality. 114

The above analysis reveals that legal institutions have played an important mediating role in the relationship between migration and labour markets since 1945, when sustained immigration to the UK began. The specific mediating role has shifted over time. During the Fordist period of accumulation, which saw an influx of migrant workers from the former Commonwealth countries, the legal institutions funnelled workers into semi and unskilled jobs in export-oriented manufacturing and the expanding services sector, ensuring that they remained there by hindering their promotion. Organising by migrants shaped the labour market by creating a legal institution that promoted equality norms. In the post-Fordist period of accumulation, major reforms to labour market institutions created a highly flexible but segmented labour market. The wave of migrants that arrived in the new millennium, particularly from E-8 and E-2 countries, was channelled into jobs at both the upper and lower ends of the labour market. The legal institutions operate to keep migrants initially placed in the secondary sector confined to it. As a corollary, given that the UK has decided to restrict the migration of ‘low-skilled’ and low-wage workers going forward, are we likely to see the predictions of anti-migrant fabulists about rising wages and plentiful jobs come true? It is unlikely. Rather, we can be fairly sure that as long as the legal institutions of the labour market remain unchanged, the dynamics described in this article will remain in place.

This article was presented at an online event organised by the ‘Work on Demand’ team in June 2021 and benefited greatly from the comments received from members of the audience. I also want to thank Bridget Anderson, Ruth Dukes, Paddy Ireland and the two anonymous reviewers who provided very helpful feedback on an earlier draft. All errors of fact and interpretation, of course, remain my own.

These arguments was often raised in the fractious debate leading up to the UK’s vote on membership of the European Union—see, eg, C. Cooper, ‘Boris Johnson Says “Uncontrolled” Immigration from EU Is Driving Down Wages and Putting Pressure on NHS’ The Independent (23 March 2016). https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/boris-johnson-says-uncontrolled-immigration-eu-driving-down-wages-and-putting-pressure-nhs-a6948346.html (accessed 15 July 2021).

See, eg, S. Nickell and J. Saleheen, ‘The Impact of Immigration on Occupational Wages: Evidence from Britain’ (London: Bank of England, 2015). Staff Working Paper No. 574. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/working-paper/2015/the-impact-of-immigration-on-occupational-wages-evidence-from-britain.pdf?la=en&hash=16F94BC8B55F06967E1F36249E90ECE9B597BA9C ; S. Lemos and J. Portes, ‘New Labour? The Impact of Migration from Central and Eastern European Countries on the UK Labour Market’ (Bonn: Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit (Institute for the Study of Labor), 2008) Discussion Paper Series IZA DP No. 3756. https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/3756/new-labour-the-impact-of-migration-from-central-and-eastern-european-countries-on-the-uk-labour-market ; C. Dustmann, F. Fabbri and I. Preston, ‘The Impact of Immigration on the British Labour Market’ (2005) 115 Economic Journal F324.

C. Devlin and others, ‘Impacts of Migration on UK Native Employment: An Analytical Review of the Evidence’ (London: Home Office and Department of Businesses Innovation & Skills, 2014) Occasional Paper 19. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287287/occ109.pdf .

M. Ruhs, ‘“Independent Experts” and Immigration Policies in the UK: Lessons from the Migration Advisory Committee and the Migration Observatory’ in M. Ruhs, K. Tamas and J. Palme (eds), Bridging the Gaps: Linking Research to Public Debates and Policy-Making on Migration and Integration (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2019), at 72.

D. Metcalf (Chair), ‘Analysis of the Impacts of Migration’ (London: Migration Advisory Committee, 2012); D. Metcalf (Chair), ‘Migrants in Low-Skilled Work: The Growth of EU and Non-EU Labour in Low-Skilled Jobs and Its Impact on the UK’ (London: Migration Advisory Committee, 2014); A. Manning (Chair), ‘EEA Migration in the UK: Final Report’ (London: Migration Advisory Committee, 2018).

On the left, a crude reading of Marxism arrives at the same position—see, eg, A. Nagle, ‘The Left Case Against Open Borders’ (2018) II American Affairs . https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2018/11/the-left-case-against-open-borders/ . However, sophisticated and contextual analyses present a more complicated picture: see, eg, C. Czabla, ‘Reading Marx on Migration’ ( Legal Form , 30 July 2018). https://legalform.blog/2018/07/30/reading-marx-on-migration-chris-szabla/ .

M. Ruhs and C. Vargas-Silva, ‘The Labour Market Effects of Immigration’ (The Migration Observatory 2020) Briefing. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/the-labour-market-effects-of-immigration/ (accessed 29 April 2021).

J. Portes, What Do We Know and What Should We Do About Immigration? (London: Sage Publications, 2019), at 29.

See, eg, S. Deakin and F. Wilkinson, The Law of the Labour Market: Industrialization, Employment, and Legal Evolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); G. M. Hodgson, Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015); S. Deakin and others, ‘Legal Institutionalism: Capitalism and the Constitutive Role of Law’ (2017) 45 Journal of Comparative Economics 188; K. Pistor, The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019). See Section 2 of this paper for further elaboration.

G. M. Hodgson, ‘What Are Institutions?’ (2006) 40 Journal of Economic Issues 1.

J. Howe, R. Johnstone and R. Mitchell, ‘Constituting and Regulating the Labour Market for Social and Economic Purposes’ in C. Arup and others (eds), Labour Law and Labour Market Regulation (Sydney: Federation Press, 2006).

See, eg, definition of ‘migrant worker’ in International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (adopted 18 December 1990, entered into force 1 July 2003) 2220 UNTS 3.

For a good discussion of the neoclassical theory on the demand for labour and supply of labour, see J. E. King, Labour Economics , 2nd edn (London: MacMillan, 1990), Chs 2 and 3.

See, eg, G. M. Hodgson, The Evolution of Institutional Economics (London: Routledge, 2004).

Hodgson, ‘What Are Institutions?’ (n.10).

J. L. Campbell and O. K. Pedersen, ‘Introduction’, The Rise of Neoliberalism and Institutional Analysis (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001).

See above n.9.

Legal norms and enforcement mechanisms clearly play an important role in the functioning of labour markets, although there are varying conceptualisations of the role that law plays in regulating the exchange of labour power for money. In the neoclassical and Hayekian traditions, which are quick to condemn the market-distorting effects of law, there is still an acknowledgement that certain laws, primarily property and contract, play an important market-facilitative role: see A. Lang, ‘Market Anti-Naturalisms’ in J. Destautels-Stein and C. Tomlins (eds), Searching for Contemporary Legal Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Deakin and Wilkinson (n.9).

While the Duty to Work and migration law will work in tandem to control supply in labour markets, they are also often pitted against each other since migration is said, erroneously, to undermine domestic welfare systems: see, eg, P. Hansen, A Modern Migration Theory: An Alternative Economic Approach to Failed EU Policy (London: Agenda Publishing, 2021).

L. Tilley and R. Shilliam, ‘Raced Markets: An Introduction’ (2018) 23 New Political Economy 534.

On the social construction of race, see, eg, M. Omi and H. Winant, Racial Formation in the United States , 3rd edn (London: Routledge, 2015).

R. Miles and M. Brown, Racism , 2nd edn (London and New York: Routledge, 2003). See also A. Sivanandan, ‘Race, Class and the State: The Black Experience in Britain’ 17 Race and Class 347.

S. Virdee, Racism, Class and the Racialized Outsider (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014); R. Shilliam, Race and the Undeserving Poor: From Abolition to Brexit (Newcastle upon Tyne: Agenda Publishing, 2018).

Hodgson sees the process of evolution through the lens of a redeemed social Darwinianism shorn of its racially legitimating applications: G. M. Hodgson, Economics and Evolution: Bringing Life Back into Economics , reprint edition (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1996). Deakin and Wilkinson, influenced by systems theory, see legal evolution as only weakly linked with economic transformations: Deakin and Wilkinson (n.9).

W. Streeck, ‘Institutions in History: Bringing Capitalism Back in’ (Cologne: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, 2009). https://www.mpifg.de/pu/mpifg_dp/dp09-8.pdf .

R. Boyer and Y. Saillard, ‘A Summary of Régulation Theory’ in Robert Boyer and Yves Saillard (eds), Régulation Theory: The State of the Art (London: Routledge, 2002). For the text that is often seen as launching this perspective, see M. Aglietta, A Theory of Capitalist Regulation—The US Experience (London: Verso, 2015).

P. Thompson, ‘Disconnected Capitalism: Or Why Employers Can’t Keep Their Side of the Bargain’ (2003) 17 Work, Employment and Society 359; M. Vidal, ‘Postfordism as a Dysfunctional Accumulation Regime: A Comparative Analysis of the USA, the UK and Germany’ (2013) 27 Work, Employment and Society 451.

R. Middleton, The British Economy Since 1945 (London: MacMillan, 2000), 25. Cf. those who thought that the period following the Second World War was marred by a series of malaises including low rates of growth relative to comparable economies, balance of payment problems, and eclipsed imperial ambitions that acted as a drain on resources, including A. Shonfield, British Economic Policy Since the War (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1958).

See Thompson (n.28); Vidal (n.28).

C. Holmes, John Bull’s Island: Immigration & British Society, 1871–1971 (London: MacMillan, 1988), at 210.

Ibid., at 214.

Ibid., at 216.

For a discussion of the various statuses under the 1948 Act and their relation, see I. S. Patel, We’re Here Because You Were There: Immigration and the End of Empire (London: Verso, 2021), 56–58.

N. El-Enany, Bordering Britain: Law, Race and Empire (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), Ch 3.

B. Anderson, Us and Them?: The Dangerous Politics of Immigration Control (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

El-Enany (n.35).

G. K. Bhambra and J. Holmwood, ‘Colonialism, Postcolonialism and the Liberal Welfare State’ (2018) 23 N ew Political Economy 574.

Patel (n.34), at 46.

Ibid., at 51.

S. Castles and G. Kosack, Immigrant Workers and Class Structure in Western Europe , 2nd edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985). While unemployment rates spiked in 1946–47, the Labour Government’s policies directed at achieving full employment succeeded, managing to reduce unemployment to under 2% of the insured labour force from 1948 onwards: K. O. Morgan, Labour in Power, 1945–1951 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), at 183.

J. Denman and P. McDonald, ‘Unemployment Statistics from 1881 to the Present Day’ (London: Labour Market Statistics Group, Central Statistical Office, 1996) Special Feature Prepared by the Government Statistical Service.

For a good contextual discussion of these concerns, see A. Gamble, Britain in Decline: Economic Policy, Political Strategy, and the British State , 4th edn (London: MacMillan, 1994).

Castles and Kosack (n.41), at Ch IX.

Sivanandan (n.23); B. Hepple, Race, Jobs and the Law in Britain (London: Allen Lane/Penguin, 1968), at Ch 4; R. Ramdin, The Making of the Black Working Class in Britain (London: Verso, 2017), at 238–40.

Ramdin (n.45).

Ibid, 234–5.

R. Lewis, ‘The Historical Development of Labour Law’ (1976) 14 British Journal of Industrial Relations 1.

Sivanandan (n.23).

Lord Wedderburn, The Worker and the Law , 3rd edn (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1986), at Ch 4.

Lord Donovan (Chairman), ‘Royal Commission on Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations, 1965–1968. Report Presented to Parliament by Command of Her Majesty’ (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1968).

O. Kahn-Freund, ‘Labour Law’, Selected Writings (London: Stevens, 1978). For an insightful discussion of how Kahn-Freund conceptualised the role of the state, see R. Dukes, ‘Otto Kahn-Freund and Collective Laissez-Faire: An Edifice Without a Keystone’ (2009) 72 Modern Law Review 220.

J. Wrench, ‘Unequal Comrades: Trade Unions, Equal Opportunity and Racism’ (Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, University of Warwick, 1986) Policy Papers in Ethnic Relations 5; E. J. B. Rose and Others, ‘Colour & Citizenship: A Report on British Race Relations’ (London: Institute of Race Relations, 1969), at Ch 19; S. Virdee, ‘Racism and Resistance in British Trade Unions, 1948–79’ in P. Alexander and R. Halpern (eds), Racializing Class, Classifying Race: Labour and Difference in Britain, the USA and Africa (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2000).

Wrench (n.53).

J. Hughes, ‘The British Economy: Crisis and Structural Change’ (1963) 21 New Left Review .

R. Trust (1982) cited in R. Miles, Racism & Migrant Labour (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982), at 163. Immigration policy was enacted through a mixture of legislative and administrative rule changes. For example, the entry of partners and dependents was often regulated through changes to administrative rules.

Patel (n.34).

J. Clarke and J. Salt, ‘Work Permits and Foreign Labour in the UK: A Statistical Review’ [2003] Labour Market Trends 563.

There were strikes by female migrant workers in 1972 (Mansfield Hosiery Mills Ltd), 1974 (Imperial Typewriters) and 1976 (Grunwick)—see S. Anitha and R. Pearson, Striking Women: Struggles & Strategies of South Asian Women Workers From Grunwick to Gate Gourmet (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2018).

On Asian youth movements—see A. Ramamurthy, Black Star: Britain’s Asian Youth Movements (London: Pluto Press, 2013). On the IWA, see J. DeWitt, Indian Workers’ Associations in Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969). On CARD, see B. W. Heineman, Politics of the Powerless: Study of the Campaign against Racial Discrimination (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972).

See Heineman (n.63).

El-Enany (n.35), at 106–7.

See, eg, J. Solomos, ‘From Equal Opportunity to Anti-Racism: Racial Inequality and the Limits of Reform’ (London: Birkbeck Public Policy Centre, Birkbeck College, 1989) Policy Papers in Ethnic Relations 17.

B. Hepple, ‘Have Twenty-Five Years of the Race Relations Acts in Britain Been a Failure?’ in B. Hepple and E. M. Szyszczak (eds), Discrimination: The Limits of Law (London: Mansell, 1992), 20.

C. O’Cinneide, ‘The Commission for Equality and Human Rights: A New Institution for New and Uncertain Times’ (2007) 36 Industrial Law Journal 141; B. Hepple, ‘The New Single Equality Act in Britain’ (2010) 5 Equal Rights Review 11.

N. Kaldor, ‘How Monetarism Failed’ (1985) May–June Challenge 4.

M. Moran, The Politics of the Financial Services Revolution: The USA, UK and Japan (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), at Ch 3.

K. Albertson and P. Stepney, ‘1979 and All That: A 40-Year Reassessment of Margaret Thatcher’s Legacy on Her Own Terms’ (2020) 44 Cambridge Journal of Economics 319.

P. Davies and M. Freedland, Labour Legislation and Public Policy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), at Chs 9 and 10.

Ibid., at Ch 9.

K. D. Ewing, J. Hendy and C. Jones (eds), A Manifesto for Labour Law: Towards a Comprehensive Revision of Workers’ Rights (London: Institute of Employment Rights, 2016), at 4.

Thompson (n.28); Vidal (n.28).

Denman and McDonald (n.42).

J. Lovering, ‘A Perfunctory Sort of Post-Fordism: Economic Restructuring and Labour Market Segmentation in Britain in the 1980s’ (1990) 4 Work, Employment and Society 9.

P. Davies and M. Freedland, Towards a Flexible Labour Market: Labour Legislation and Regulation Since the 1990s (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), at 11. See also H. Collins, ‘Independent Contractors and the Challenge of Vertical Disintegration to Employment Protection Laws’ (1990) 10 Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 353.

For a good summary of the various theories of labour market dualism/segmentation, see J. Peck, Workplace: The Social Regulation of Labour Markets (New York: The Guilford Press, 1996), at Ch. 3 and S. Deakin, ‘Addressing Labour Market Segmentation: The Role of Labour Law’ (Governance and Tripartism Department, International Labour Office 2013) Working Paper 52.

C. Brown, Black and White: The Third PSI Survey (London: Heinemann, 1984).

‘International Migration: A Recent History—Office for National Statistics’ (15 January 2015). https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/articles/internationalmigrationarecenthistory/2015-01-15 (accessed 1 May 2021).

El-Enany (n.35), at 126. For the increased numbers, see J. Salt and V. Bauer, ‘Managing Foreign Labour Immigration to the UK: Government Policy and Outcomes Since 1945’ (London: UCL Migration Research Unit, 2020).

Clarke and Salt (n.60).

J. Salt and R. T. Kitching, ‘Labour Migration and the Work Permit System in the United Kingdom’ (1990) 28 International Migration 267.

P. W. Walsh, ‘Asylum and Refugee Resettlement in the UK’ (The Migration Observatory 2021) Briefing. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migration-to-the-uk-asylum/ (accessed 1 May 2021).

See, eg, R. Heffernan, New Labour and Thatcherism: Political Change in Britain (London: Palgrave, 2001).

For a distillation of ‘Third Way’ thinking, see H. Collins, ‘Is There a Third Way in Labour Law?’ in J. Conaghan, R. M. Fischl and K. Klare (eds), Labour Law in an Era of Globalization: Transformative Practices & Possibilities (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). For a discussion of the distance between the practice of New Labour and the ideology of Third Way, see S. Fredman, ‘The Ideology of New Labour Law’ in C. Barnard, S. Deakin and G. Morris (eds), The Future of Labour Law: Liber Amicorum Sir Bob Hepple (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2004).

‘Fairness at Work. Presented to Parliament by the President of the Board of Trade by Command of Her Majesty’ (1998) Cm 3968.

For extended analyses of New Labour’s reform to the legal institutions of the labour market, see T. Novitz and P. Skidmore, Fairness at Work (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2001); A. Bogg, The Democratic Aspects of Trade Union Recognition (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2004).

Deakin (n.80).

B. Anderson and M. Ruhs, ‘Migrant Workers: Who Needs Them? A Framework for the Analysis of Staff Shortages, Immigration, and Public Policy’ in M. Ruhs and B. Anderson (eds), Who Needs Migrant Workers? (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

W. Sommerville, Immigration under New Labour (Bristol: Policy Press, 2007). For a sophisticated account of the economic, ideological and institutional factors leading to New Labour’s position on immigration, see E. Consterdine, Labour’s Immigration Policy: The Making of the Migration State (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

M. Fernández-Reino, ‘Migrants in the UK Labour Market: An Overview’ (The Migration Observatory 2021) Briefing. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migrants-in-the-uk-labour-market-an-overview/ .

N. Lillie and I. Greer, ‘Industrial Relations, Migration, and Neoliberal Politics: The Case of the European Construction Sector’ (2007) 35 Politics & Society 551; C. Woolfson, ‘Labour Migration, Neoliberalism and Ethno-Politics in the New Europe: The Latvian Case’ (2009) 41 Antipode 952.

Salt and Bauer (n.83).

M. Zou, ‘Employer Demand for “Skilled” Migrant Workers: Regulating Admission under the United Kingdom’s Tier 2 (General) Visa’ in J. Howe and R. Owens (eds), Temporary Labour Migration in the Global Era: The Regulatory Challenges (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2016).

M. Sobolewska and R. Ford, Brexitland: Identity, Diversity and the Reshaping of British Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), at 30.

Office of National Statistics, ‘Unemployment Rate (Aged 16 and Over, Seasonally Adjusted)’ ( Labour Market Statistics Time Series ). https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/timeseries/mgsx/lms (accessed 19 May 2021).

B. Anderson, ‘Migration, Immigration Controls and the Fashioning of Precarious Workers’ (2010) 24 Work, Employment and Society 300.

A. Lentin, ‘Cameron’s Immigration Hierarchy: Indians Good, Eastern Europeans Bad’ The Guardian (18 February 2013). https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/feb/18/cameron-immigration-indians-good >.

Anderson and Ruhs (n.92).

ERA 1996, s 108(1).

For an insightful discussion of how the illegality doctrine in relation to employment claims is likely to be treated under a situation of statutory illegality, see A. Bogg, ‘Irregular Migrants and Fundamental Social Rights: The Case of Back-Pay under the English Law on Illegality’ in B. Ryan (ed), Migrant Labour and the Reshaping of Employment Law (Oxford: Hart Publishing, forthcoming).

P. Connor and J. S. Passel, ‘Europe’s Unauthorized Immigrant Population Peaks in 2016, Then Levels Off’ (Washington, DC: Pew Research Centre, 2019). https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/11/13/europes-unauthorised-immigrant-population-peaks-in-2016-then-levels-off/ .

D. Metcalf, United Kingdom Labour Market Enforcement Strategy 2018/19 (London: HM Government, 2018) Presented to Parliament pursuant to s 5 (1) of the Immigration Act 2016. https://www.webarchive.org.uk/access/resolve/20180522191539 or https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/705503/labour-market-enforcement-strategy-2018-2019-full-report.pdf (accessed 1 May 2021).

C. Barnard, ‘Enforcement of Employment Rights by Migrant Workers in the UK: The Case of EU-8 Nationals’ in Cathryn Costello and Mark Freedland (eds), Migrants at Work: Immigration and Vulnerability in Labour Law (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2014).

A. Geddes and S. Scott, ‘UK Food Businesses’ Reliance on Low-Wage Migrant Labour: A Case of Choice or Constraint’ in B. Anderson and M. Ruhs (eds), Who Needs Migrant Workers? Labour Shortages, Immigration, and Public Policy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

A. Batnitzky and L. McDowell, ‘The Emergence of an “Ethnic Economy”? The Spatial Relationships of Migrant Workers in London’s Health and Hospitality Sectors’ (2013) 36 Ethnic and Racial Studies 1997.

F. van Hooren, ‘Varieties of Migrant Care Work: Comparing Patterns of Migrant Labour in Social Care’ (2012) 22 Journal of European Social Policy 133.

J. Portes, ‘Immigration and the UK Economy After Brexit’ (Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics, 2021) Discussion Paper Series.

D. Strauss, ‘Surge in Hiring as Hospitality Reopens Adds to Pressure on Labour Market’ [2021] Financial Times . https://www.ft.com/content/98c3a781-7661-41a7-b6a3-4ff9a0a10b9b .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3669

- Print ISSN 0305-9332

- Copyright © 2024 Industrial Law Society

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Bibliography

- More Referencing guides Blog Automated transliteration Relevant bibliographies by topics

- Automated transliteration

- Relevant bibliographies by topics

- Referencing guides

Dissertation Abstracts

- List of abstracts

- Abstracts of dissertation form

Impact of Migration on Social Well-Being of Women Labourers in Bhubaneswar, Odisha

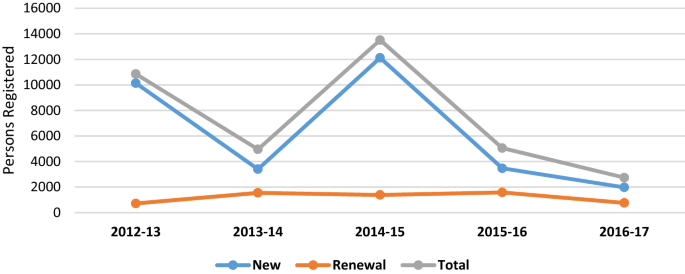

Author: Nupur UO Pattanaik, [email protected] Department: Sociology University: Ravenshaw University, India Supervisor: Prof. Anita Dash Year of completion: 2018 Language of dissertation: English

We use cookies on this website to give you a better user experience. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. Learn more

Labour and migration have always been an important topic of research and discussions. ERIA dives deep into it through a range of sub-topics surrounding labour and migration, such as labour mobility, employment, rural development, social welfare, labour adjustment management, migrant networks, and social protections. Furthermore, ERIA also works on problems related to labour and migration such as gender wage gap and inequality.

Publications

Recent Articles

Search eria.org, latest multimedia.

Latest News

20 March 2024

13 March 2024

12 March 2024

- Skip to main content

Advancing social justice, promoting decent work

Ilo is a specialized agency of the united nations, highlights from nairobi's labour migration breakfast session.

Operationalizing the National Steering Committee and the Technical Coordinating Committee on the implementation of the Global Labour Market Strategy on Labour Migration.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Migration rose by one-third last year to lift Australia’s population by a record 659,000

The net annual rise was revealed as Labor signalled moves to reduce migration arrivals

- Follow our Australia news live blog for latest updates

- Get our morning and afternoon news emails , free app or daily news podcast

Australia welcomed more than 2,000 migrants a day in the year to September, helping to swell the country’s population by a record 659,800 , reigniting political debate about measures to reduce arrivals.

Migration arrivals rose by a third compared with the previous year to hit 765,900, driven by international students and workers on temporary visas, while departures slipped to 217,100.

The record net annual increase of almost 550,000 comes despite the Albanese government’s expectation to bring migration down from 510,000 to 375,000 a year by June 2024, which was laid out in the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook. Net migration in the September 2023 quarter hit 145,200, close to government expectations.

The Coalition has taken up the politically charged issue as a talking point, with the shadow immigration minister, Dan Tehan, telling reporters in Canberra that “record numbers of people are causing a housing crisis, they’re causing a rental crisis”.

The anti-racism activist group Democracy in Colour denounced the comments, with campaigner Jarrod Tan saying it is “irresponsible” to play the “migrant blame game for a housing crisis that is decades in the making”.

Tehan denied demonising migrants for political gain, but argued that immigration levels must be “sustainable” and “in-sync” with housing supply.

The treasurer, Jim Chalmers, told parliament in question time that the data “doesn’t take into account … the quite substantial action” the government has taken to put “downward pressure” on net overseas migration.

In December the government announced it would enact reforms recommended by the migration review including raising English language requirements and implementing a “genuine student” test for international students.

Ahead of the ABS data release the home affairs minister, Clare O’Neil, announced on Wednesday the government would enact some of these migration-cutting policies starting this Saturday, including the imposition of “no further stay” conditions on visitor visas to prevent them being exploited by those who should be on student visas.

The employment minister, Tony Burke, deflected attacks by noting that opposition leader, Peter Dutton, had previously publicly advocated “for higher rates of immigration”, including after the September 2022 jobs and skills summit.

Sign up for Guardian Australia’s free morning and afternoon email newsletters for your daily news roundup

Businesses in search of skilled labour say the migration system should not get too restrictive, with KPMG’s head of migration services, Mark Wright, encouraging the government to prioritise productivity.

“An informed discussion around Australia’s migration program should centre on the skills Australia requires, rather than simply the numbers which make up our overall migration program,” he said.

High population growth risks forcing up the unemployment rate, as jobs become increasingly scarce, though Thursday’s fall in the unemployment rate indicates the jobs market is comfortably absorbing migrant workers.

after newsletter promotion

“This is adding to the supply of labour and we need to add around 35k of jobs each month to keep the unemployment rate steady,” the Commonwealth Bank senior economist Belinda Allen said.

The economy added 116,600 jobs – two-thirds of them full-time roles – in February, compared with economists’ forecast for a net gain of 40,000 positions.

High population growth is in line with the Reserve Bank’s estimation in its February statement on monetary policy that Australia’s population would grow by more than 530,000 a year by June 2024.

While net overseas migration increased more in the September 2023 quarter than the preceding June quarter, it remained lower than the current record of 157,684, from the March quarter of 2023.

“Typically the March and September quarters see a larger increase in net overseas migrants due to the start of the university semester,” Allen said.

Thursday’s data also revealed substantial interstate migration in the year to September 2023, with 33,000 people leaving New South Wales and 32,000 people moving to Queensland and a further 10,000 moving to Western Australia.

Australia’s total population hit 26.8 million in September, according to the new ABS figures, though the bureau’s population clock estimated in January that the figure has already reached 27 million.