- Skip to right header navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

How to Give Constructive Feedback to Creative Writing

December 14, 2020 // by Lindsay Ann // 1 Comment

Sharing is caring!

Do you wonder how to give constructive feedback on creative writing and poetry pieces created by student writers who have put their heart and soul into them?

I think all teachers struggle with this question to some extent. It is because we care.

This can lead to indecisive response to student work. We waste valuable time when we lack a plan for response and worry about the emotional reaction to our feedback.

In this post, I’m all about sharing practical strategies that will teach you how to best give constructive feedback.

I want you to feel as comfortable responding to creative writing assignments as analysis based writing or argumentative writing assignments so that you can help student writers grow without deflating their fragile egos.

Setting the Stage for Writing Feedback

I think that it’s important to remember the feeling associated with having someone else read our work.

When I was a student, it was always a mixture of anticipation and dread . Would my instructor like what I had written? Would my grade reflect the time and effort I had put into the assignment?

A couple of things before we discuss how to give constructive feedback…

👉 I think that it’s important to be clear with students upfront about the skills you’re looking for in a creative writing assignment. Frontload with exemplars and use creative writing exercises to practice skills. Then, when it comes time for students to write, they will know what they are expected to do as writers.

👉 At the same time, it’s important to focus on feedback during the writing process . This allows our response to be as readers rather than as evaluators.

👉 Finally, I think that it makes a BIG difference when you model your own creative process for students. The more I can show students that writing is messy and imperfect, that I go through the same process as them, the more my classroom dynamic shifts from teacher-centered to student-centered and collaborative. If you’re wondering how to give constructive feedback to students, ask them to give feedback to you first.

Constructive Feedback for Students

When it comes to student feedback, less is more. I’ve blogged about this before, but I’ll say it again (and again) (and…again).

Most students don’t care about our carefully-worded paragraphs. They want to be seen and heard , but they also want to be able to understand what they can do to improve.

This means that feedback should be direct, specific, and actionable . This means that we need to respond as readers , not evaluators. This means that we will leave a manageable amount of feedback to build a student’s momentum.

Strategies for How to Give Constructive Feedback

➡️ Only mark the lines you love the most. Highlight them, underline them, put a star in the margin. Choose a couple of these lines to comment on. What did you notice? What did you like/realize/want to know?

➡️ Focus on the skills taught in class. So, if you taught characterization and concrete details, give feedback specifically on those elements. Ask students to revisit resources/screencasts/examples, etc. to review these skills.

➡️ Focus on moments of clarity and confusion. Where did you, as a reader, make a connection or realize something important? Where were you confused?

➡️ Yin Yang Feedback

- Find something specific that you liked/enjoyed (and explain why/how ). Maybe it’s a bit of figurative language or a vivid image. Pair this with a suggestion for where the writer can continue to work on this same skill. Essentially, this is like saying, “See, here, you did this thing that I liked and enjoyed…can you do more of that over here?” Or, “As a reader, it seemed to me like your intent was x, y, or z when you wrote _________. I’m wondering if you can make this clearer when _________.

- What is the highest level of skill mastery you can observe? Find an example of success and talk about why/how it was successful. What is the most important skill that still needs to be developed? Find a place where the student can begin working on this skill.

- Where were you most engaged/interested in the story. Leave a quick note about what captured your attention. Where were you least engaged/interested? This type of teacher feedback encourages revision.

➡️ Be curious. Read through the draft and ask questions… only questions . This is a kind of constructive feedback students love to hate (because it makes them think ). I ask my students to respond and revise. This strategy rocks because it establishes feedback as a two-way conversation rather than a one-way lecture.

➡️ Have students direct your feedback by asking you questions about their work. Alternatively, you can ask students to reflect on how/where they have demonstrated the skills you’ve taught in class (or the goals they’ve set for themselves). Then, you simply read through and respond to their comments, sharing your thoughts and suggestions.

➡️ Use a writer’s workshop model in which you conference with students about their work. You can train students to lead in these conversations if you choose the 1:1 model. Alternatively, you can form writing circles in which you provide students examples of constructive feedback before asking students to take turns reading their work out loud and solicit feedback from group members. You can float between writing groups, joining the conversations as needed.

Final Thoughts

I hope that I’ve helped you learn more about how to give constructive feedback to creative writers.

As we become purposeful in our responses to students, the benefit is that we streamline our own systems and processes which allows us to feel better about the feedback we are giving and also the amount of time it takes to provide this feedback!

Hey, if you loved this post, I want to be sure you’ve had the chance to grab a FREE copy of my guide to streamlined grading . I know how hard it is to do all the things as an English teacher, so I’m over the moon to be able to share with you some of my best strategies for reducing the grading overwhelm. Click on the link above or the image below to get started!

About Lindsay Ann

Lindsay has been teaching high school English in the burbs of Chicago for 19 years. She is passionate about helping English teachers find balance in their lives and teaching practice through practical feedback strategies and student-led learning strategies. She also geeks out about literary analysis, inquiry-based learning, and classroom technology integration. When Lindsay is not teaching, she enjoys playing with her two kids, running, and getting lost in a good book.

Related Posts

You may be interested in these posts from the same category.

Book List: Nonfiction Texts to Engage High School Students

12 Tips for Generating Writing Prompts for Writing Using AI

31 Informational Texts for High School Students

Tardies & Chronic Absenteeism: Fighting the Good Fight

Open Ended Questions That Work

Project Based Learning: Unlocking Creativity and Collaboration

Empathy and Understanding: How the TED Talk on the Danger of a Single Story Reshapes Perspectives

Teaching Story Elements to Improve Storytelling

Effective Classroom Management Strategies: Setting the Tone for Learning

Figurative Language Examples We Can All Learn From

18 Ways to Encourage Growth Mindset Versus Fixed Mindset in High School Classrooms

10 Song Analysis Lessons for Teachers

Reader Interactions

[…] How to Give Constructive Feedback to Creative Writing […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Giving Effective Feedback to Creative Writers

Your writing partner has asked for some feedback on her novel. Now what?

The Three P’s: Purpose, Plan, and Process

The Three P's of providing feedback will help you provide feedback that your writing colleauges can actually use.

Know Your Purpose

Grounding yourself with the purpose of your feedback helps keep you productively focused. Clarity of purpose should be your starting point before you even start reading or listening to a written work. It will guide your attention and ensure you are more likely to help than harm your writing partner. In other words: Are you giving tough feedback to someone who can benefit from it or shattering a new writer’s confidence? Are you there to help a new writer feel heard, or are you working with someone half-way down the path to develop their craft? Are you looking down in the weeds or at the big picture? Asking the writer what they want from you at the beginning of the feedback process is the best way to guide your efforts.

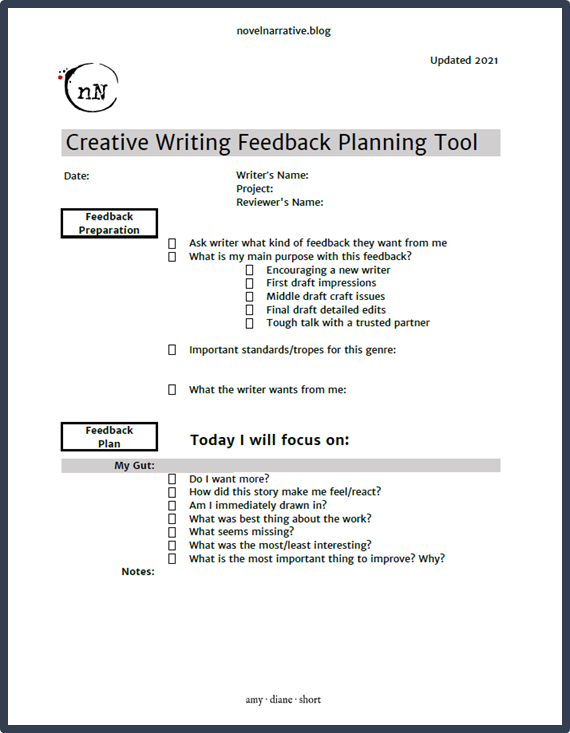

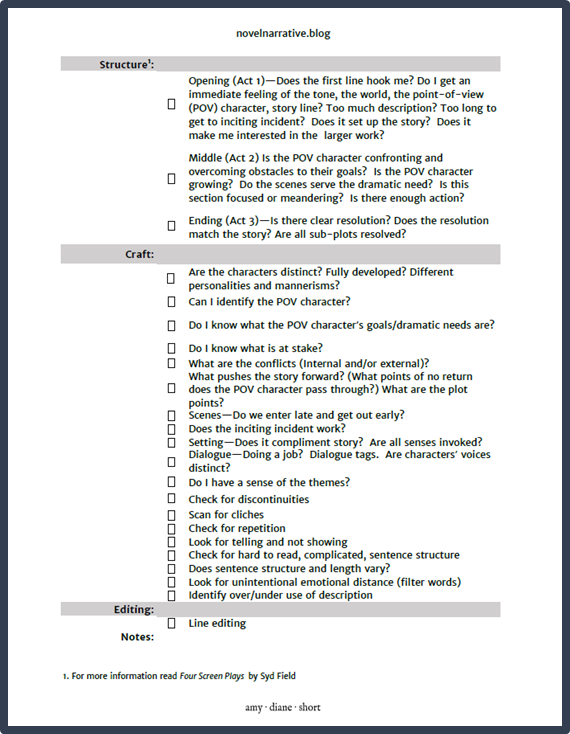

Make a Plan

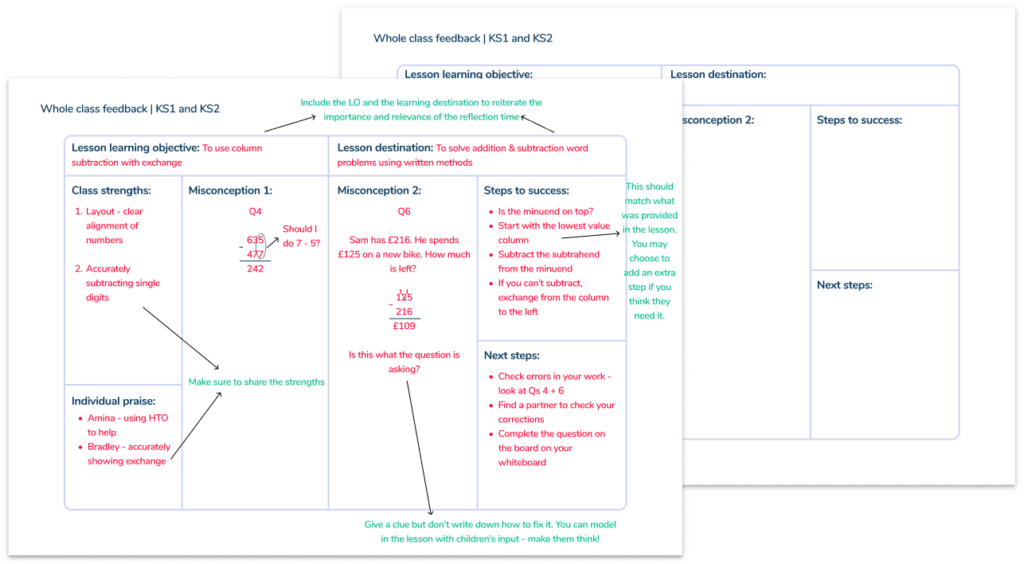

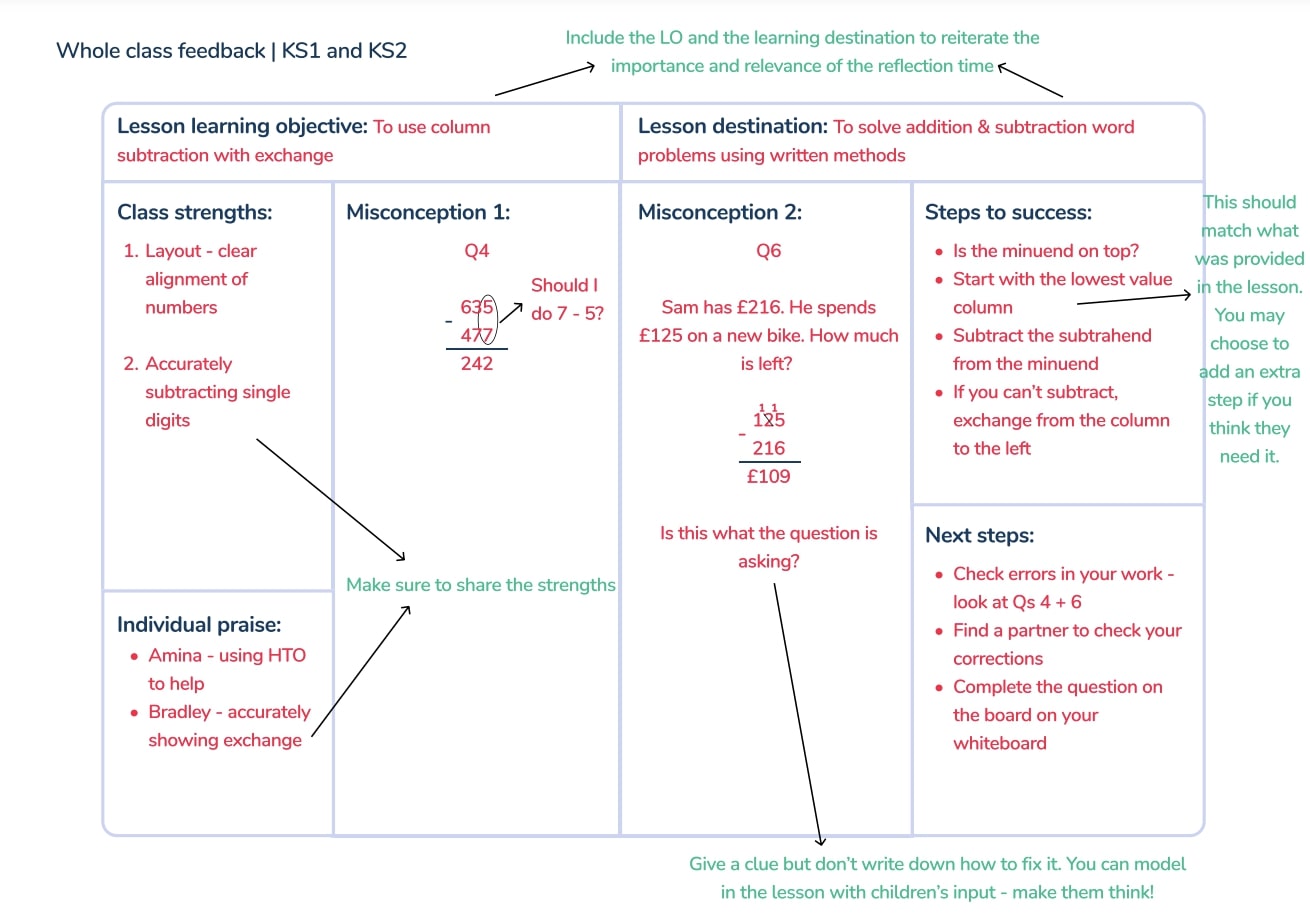

Sitting down to provide feedback can mean different things to different people on different days. We are all busy and distracted, and having a targeted agenda can make sure we stick to our goals. Once you have your purpose in mind, it can help to have a written plan of attack that will allow you to focus your efforts and make sure you don’t forget to cover all the ground you intended. This plan can take the form of a simple to-do list or a more formal planning tool like the one shown above and below.

You can get it here: Creative Writing Feedback Planning Tool

Your plan should include the purpose of the feedback you are giving and critical areas you will be addressing, such as emotional reactions, story structure, craft, or editing. For long-term projects, keep each feedback sitting’s planning tool. Collectively, they can provide a historical record of the feedback supplied over time, which can help identify areas of feedback yet to be covered, or recurring problem spots.

Have a Process

Building a standard process can help you do your best work. Sample from these steps to make your own workflow.

1. Centered around the purpose of the feedback at hand, create your plan.

2. Set aside an appropriately sized amount of time. If your plan will require multiple sittings, go ahead and schedule these out on your calendar, so time doesn’t get away from you. I find it very inefficient to let too much time pass between sittings because I lose a sense of what I have already done and must start over to orient myself. Who has time for that?

3. Find a place where you can focus, be that hiding from your family in the bathroom, in a coffee shop soothed by the white noise of steaming espresso, or, if you are lucky enough to have one, locked in your home office.

4. For your first pass at written notes, make a version of the document, be it printed or an electronic file, that no one besides you will ever see. Here you won’t have to hold back or filter your thoughts. Having an eyes-only version of your first feedback pass ensures more helpful feedback later and allows you to move more quickly.

5. Read the document or portion you are working on more than once. It is hard to give good feedback if you have only skimmed.

6. Follow your feedback plan and take written notes about both what works very well and what needs improvement on your private version of the document.

7. You can wordsmith the final feedback on the version of the document you will provide the author at the end of the process. Don't overwhelm new writers with too much feedback - prioritize. Remember that writers at all levels appreciate kindness.

8. If possible, share your feedback with the author in person while physically present or using conferencing technology. A conversation allows the author to ask the reviewer for clarification and squeezes the most value out of the feedback. This connection is even more important when you are working with newer writers. One-on-one feedback allows you to nurture a trusted relationship with inexperienced writers that will help build their confidence.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the following blogs for the fantastic information about giving feedback to creative writers.

How to Give Constructive Feedback to Creative Writing

How to Give Feedback on Fiction: A Guide for Readers

#5onFri: Five Tips For Writing A Helpful Critique

How to give constructive criticism to other writers

- Center for Teaching Excellence

- Learning Tech

- Teaching Hub

A Guide to Giving Writing Feedback that Sticks

- Joe Fore , Professor

We turn our attention to a more substantive aspect of writing feedback: what and how much to comment on.

The blog posts in this series on feedback have focused mostly on the stylistic and procedural aspects of feedback: how to prime students to receive constructive feedback , how to phrase feedback so it’s received well , and how to provide feedback in different formats for greater efficiency . Now we turn our attention to a more substantive aspect of writing feedback: what and how much to comment on.

Too often, writing instructors feel compelled to point out every issue—however large or small—that we see in a piece of student writing: a weak topic sentence at the start of the paragraph, a flawed use of evidence a few sentences later, a typo in that same sentence, and a citation error at the paragraph’s end. We sometimes measure our feedback’s value by the pound; each mark we make on the page is valuable, and more is better. But, much of the time, feedback fails not because students are getting too little feedback—but, rather, too much (Grearson, 2002).

The reality is that students can only learn so much on one assignment (Enns & Smith, 2015). By trying to force 25 different lessons on students in a single set of comments, there’s a real risk that they’ll actually take away none. Writing too many comments on an assignment also leaves students with no sense of learning priorities; they may not know which issues are most important to focus on (Enquist, 1996; Grearson, 2002). Moreover, inundating students with comments can demoralize them; they may interpret the sea of handwriting or typed comments as a sign that they’re just not cut out to be a writer.

What’s the solution? We, as writing instructors, need to be more realistic about how much feedback our students can absorb. We need to be more intentional and targeted in what we’re commenting on. We must prioritize our feedback to hit the essentials, the key things we want students to take for next time (Grearson, 2002). And we need to focus on quality over quantity in our comments—explaining those few key concepts in thoughtful ways that allow students to take those lessons to heart (Enquist, 1999).

Using these ideas, we can break the process of providing effective writing feedback into three steps:

Before commenting, establish clear feedback priorities.

While commenting, give fewer, more detailed comments that reflect those priorities.

After commenting, provide global comments that summarize how your feedback connects to those priorities.

Let’s discuss each idea, in turn.

BEFORE YOUR REVIEW

1. establish clear feedback goals and priorities..

Before you sit down to review papers, reflect on what you want students to take away from your feedback. What do you want them to think , feel , or do when they review this feedback (Frost, 2016)? This could vary depending on the timing during the semester, level of student, and nature of the assignment.

At the beginning of the semester, it might make more sense to focus on bigger-picture issues like thesis development or large-scale organization. Again, though, that’s not a hard-and-fast rule. For example, if you’re working with first-year college students or students with less writing experience, you might need some focus on writing mechanics or grammatical issues—even at the early stages.

From those goals, it’s also crucial to establish commenting priorities—a checklist of discrete issues that you’re looking for (Enquist, 1999; Grearson, 2002). Importantly, these need to be written down and put in a place where you can refer to them periodically while reviewing papers . By doing so, you’re more likely to stay on track and provide targeted feedback, rather than getting sidetracked or bogged down with numerous, less-important comments.

DURING YOUR REVIEW

2. skim the assignment first..

Review the piece of writing—without any expectation of giving feedback (Enquist, 1999; Gottschalk & Hjortshoj, 2004). The purpose of this first pass is simply to get an overview of the assignment (its length, topic, thesis, etc.) and begin to identify the likely areas that you’ll be commenting on. This will help you prioritize your priorities. For example, let’s say that your priorities are: (1) large-scale organization (introductions, conclusions, roadmaps) and (2) paragraph-level organization (topic sentences, transitions, etc.). If a quick skim of the paper reveals major, large-scale structural issues, then you’re probably going to devote your energy there, while spending little (if any) time on the secondary, paragraph-level issues.

3. Teach—don’t edit.

I know this is a familiar refrain for writing instructors, but we all need reminding from time to time: You are a teacher—not a copy editor . Your job is not to correct all your students’ “mistakes,” logical gaps, long-winded sentences, typos, or grammatical errors (Grearson, 2002). Rather, your job is to help them learn and improve in a way that allows them to apply those lessons in the future (Gottschalk & Hjortshoj, 2004). And, ultimately, that requires putting quality over quantity, reducing the amount of time you’re spending on small, repetitive comments and corrections, and ensuring that your comments prompt genuine learning from students (Grearson, 2002). Here are a few concepts to keep in mind that can help make that happen.

Explain your corrections, edits, or comments. To truly learn and improve for next time, students need to understand (a) why you flagged a particular word, made a correction, or made a particular comment, (b) what is problematic about it, and (c) how to correct the issue. Particularly unhelpful commenting techniques include:

Short, cryptic questions (“ Are you sure? ”; “ Needed?” ; “Best evidence?” )—or even worse, a lone question mark, without elaboration to indicate a lack of clarity (Davis, 2006; Enquist, 1996)

Merely circling, highlighting, or underlining problematic passages (Enquist, 1996)

Sentences that are crossed out or rewritten, without explanation (Grearson, 2002)

These types of comments leave students confused, frustrated, and—most importantly—unable to meaningfully improve for next time. Also, students will be tempted to just mechanically accept unexplained edits without engaging in reflection to understand how your edits improved the writing (Grearson, 2002). Instead of editing or “correcting” innumerable sentences, we need to focus on having fewer, higher-quality comments that explain the rationale behind our comments and corrections (Enquist, 1996; Enquist, 1999; Grearson, 2002).

Give examples. One helpful alternative to correcting or editing is to suggest a possible way to improve the writing (Enquist, 1999). This is different from simply crossing out the sentence and rewriting it, which gives the (usually false) impression that the current sentence was objectively “wrong” and that your fix was the single, authoritative, “right” way to do it (Davis, 2006). Instead, an effective example needs to have two parts: (1) a brief explanation of the problem, and (2) a suggested solution, framed as just one of various possible ways of ameliorating the issue For example, if you encounter a long, run-on sentence, you could write something like, “ This sentence is rather long and combines several different ideas—which might confuse the reader. One way to improve things might be to put a period at the end of the first clause and then starting the next sentence with ‘But…’ to show the contrasting idea .”

Flag common issues once. Writing the same comment over and over—“ Another run-on sentence here ”—wastes your time and merely clutters the page by repeating something the student already knows they have an issue with. Moreover, if the repeat issue reflects something the student doesn’t know—for example, a grammatical quirk or a formatting rule about citations—what good does pointing it out multiple times do? You’ve pointed it out; now they know. Move on. These repeated issues—especially more important mistakes—can be useful to mention in an end note or cover page ( more on this later ) (Enquist, 1999).

Connect comments to class content. This will help students make explicit connections between course readings, lecture (Enquist, 1999). It also puts the onus on them to do a bit of digging and self-reflection—rather than passively receiving your feedback. Say something like this: “ Recall that we discussed headings in Week 7. It may be helpful to revisit those slides for some additional examples. ” It also reminds students that your feedback isn’t arbitrary—that it’s tied directly to things they’ve learned (or should have learned) in class (Davis, 2006).

Show students where they did it right. Another way to help students cement writing lessons is to show them where they did it right. In the learning stage, students might experiment with different writing techniques, hoping that one of them will land. So point out places where they got it right. This will reinforce the lessons that they’ve already learned and are capable of replicating (Enquist, 1999; Gottschalk & Hjortshoj, 2004). There is, perhaps, no more effective and genuinely encouraging comment you can give a student than to show the need for improvement— by referencing a place where they did it better: “ This paragraph needs a clearer, stronger topic sentence to show the reader where it's going—just like you had two paragraphs above! You nailed it there; we just need to add a similar thing here ” (Frost, 2016).

Refer students to external resources. The burden is not all on us to actively teach every single lesson; we also have to empower and trust our students to take responsibility for their own learning. Particularly with ancillary issues like grammar and citations, refer students to outside resources, rather than explaining these concepts through in-depth comments. Will every student avail themselves of the extra resources you provide? Of course not. But some will. (You can improve the chances of students doing this by making these resources easy to find, for example by linking to online resources in your comments or by posting PDFs of relevant sources on the course homepage.)

In addition to helping students directly, sharing such resources can improve students’ perception of your teaching. Even those students who don’t use the resources in detailed ways may appreciate your going the extra mile to provide the extra help. And sharing your knowledge of these outside resources bolsters your credibility by showing that you have expertise and your feedback is rooted in deep knowledge in your field, which can help increase student receptivity to feedback (Davis, 2006).

AFTER YOUR REVIEW

4. write a “cover page” with 2-4 points, lessons, or themes..

In addition to commenting throughout the piece of writing, it’s critical to also provide “global comments” that distill your feedback into a few key points and identify broader themes that your comments reflect (Enquist, 1996; Enquist, 1999; Gionfriddo, et al., 2009; Gottschalk & Hjortshoj, 2004; Grearson, 2002). These global comments can take various forms. For example, if you’re providing handwritten feedback on physical papers, this could be a separate typed “end note” or “cover page.” Or it could be in the body of an email that accompanies comments on an electronic document. Or it could be a short video or audio recording that summarizes some of your feedback’s themes (Bahula & Kay, 2020).

While many writing instructors call these global comments an end note, I prefer the notion of a cover page (Enquist, 1999). That way, students see your holistic feedback before diving into your specific comments and suggestions on individual sentences. Putting your global comments first has two advantages. From an emotional standpoint, it offers you the chance to prepare the student for feedback they’re about to get. (This can be especially important for students earlier in their college careers and earlier in your courses, when they might be feeling particularly anxious or vulnerable.) Second, it gives students context for the feedback, making it more likely that they’ll see your individual comments and points not as scattershot suggestions, but as specific examples of a few larger lessons.

By summarizing your feedback into a few key points, students are more likely to take away those few, truly important lessons and less likely to view your feedback as just a smattering of unconnected ideas. And that’s the kind of feedback that’s most likely to stick with them for the rest of your course—and beyond.

Bahula, T., & Kay, R. (2020). Exploring student perceptions of video feedback: A review of the literature. ICERI2020 Proceedings , 6535-6544. https://library.iated.org/view/BAHULA2020EXP

Davis, K. (2006). Building credibility in the margins: An ethos-based perspective for commenting on student papers. Journal of the Legal Writing Institute . 2, 74-104. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1116619

Enns, T., & Smith, M. (2015). Take a (cognitive) load off: Creating space to allow first-year legal writing students to focus on analytical and writing processes. Journal of the Legal Writing Institute , 20, 109-40. https://www.legalwritingjournal.org/article/27432-take-a-cognitive-load-off-creating-space-to-allow-first-year-legal-writing-students-to-focus-on-analytical-and-writing-processes

Enquist, A. (1999). Critiquing and evaluating law students’ writing: Advice from thirty-five experts. Seattle University Law Review , 22(4), 1119-1163. https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sulr/vol22/iss4/13/

Frost, E.R. (2016). Feedback distortion: The shortcomings of model answers as formative feedback. Journal of Legal Education , 65(4), 938-965. https://jle.aals.org/home/vol65/iss4/10/

Gionfriddo, J. K., Barnett, D. L., & Blum, E. J. (2009). A methodology for mentoring writing in law practice: Using textual clues to provide effective and efficient feedback. Quinnipiac Law Review , 27, 171-226. https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp/229/

Gottschalk, K. & Hjortshoj, K. (2004). The Elements of Teaching Writing: A Resource for Instructors in All Disciplines. Bedford.

Grearson, J. C. (2002). From editor to mentor: Considering the effect of your commenting style. Journal of the Legal Writing Institute , 8, 147-174. https://www.lwionline.org/article/editor-mentor-considering-effect-your-commenting-style

Related results will be displayed below.

- Collections

- Our Mission

6 Steps to Effective Whole-Class Feedback

Ensuring that students know what they did well and where they need to improve doesn’t have to be an interminable task.

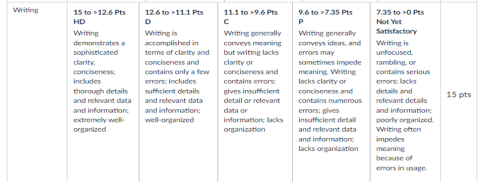

Consider this. It’s Sunday evening and you’re once again sitting at your desk. Back stiff and fingers sore. You’ve been here for the past three hours, taking an exercise book from an ever-so-slowly dwindling pile and then grading it. One after the other. For hours. And there are still seven left.

For many teachers, this is a familiar scenario, even a rite of passage. Staying up late on the weekend, desperately trying to fight your way through a stack of work before Monday morning.

But it doesn’t need to be like this. As an approach to grading student work, the promise of whole-class feedback is potentially transformative. Instead of giving each student a personalized written comment, focus on identifying and addressing common patterns across the whole class. Grade better by grading quicker. Since first reading about it in a 2015 blog post by Joe Kirby , I’ve experimented with various whole-class feedback routines, refining and improving my own approach.

I’ll share my latest version with you—outlining a step-by-step guide that can be implemented immediately. In my experience, it works best when grading and providing feedback for already completed work, but it could easily be adapted to guide students at a draft phase.

Step 1: Read and Highlight Student Work

As with all grading, whole-class feedback begins by collecting student work and reading it. Yet, this is also where the differences start.

Rather than scribbling detailed individual comments in the margins, read with a highlighter in your hand. If you read something you like, highlight it. It could be an idea, the way a student has phrased something, or where they’ve met an agreed success criterion.

We do this for two reasons. First, it’s a far quicker way of showing students that we have read and paid attention to their work. Second, it provides an opportunity for metacognitive reflection, as students reflect on exactly why something may have been highlighted.

Step 2: Identify Individual Next Steps

Once you’ve read a piece of work, provide the student with a targeted next step, ideally drawn from a premade template. This is a specific goal that they need to work on for their next piece of similar work. Like highlighting, this serves a motivational function. It shows students that you’ve attended to their work and are offering them something specific and personal to act on.

Step 3: Identify Examples of Excellence

While reading student work, seek out examples of excellence. This is going to form a core part of the feedback lesson.

Aim for at least two examples of excellence drawn from student work. As you read, make a note of any such examples on a piece of paper. During the feedback lesson, share these with the whole class, live-modeling them and explaining why they’re excellent. Students see what excellence looks like, and this step discloses the nature of success in a concrete and actionable manner.

It’s crucial that these examples come from student work. In my experience, this provides a significant boost to student motivation. To those students whose examples you use, there is public recognition for their work, although you may wish not to disclose names (I keep the examples anonymous). To everyone else, there is a specific model that they can adopt and adapt, as well as accruing all the benefits that come with any live modeling. By using student work, we communicate a clear message: If one person can do it, then so can everyone.

Step 4: Create the Template

By the time you reach the final piece of student work, you should have completed the following:

1. Highlighted student work, focusing on what you like.

2. Given each student an individual target, ideally drawn from a prewritten template.

3. A couple of examples of excellence, jotted down on paper and drawn from student work.

For a full set of class grading, getting to this point usually takes me just under an hour.

With the student work in hand, now it’s time to give it back. This is the premade template I use , printed out beforehand and attached to each assignment with a target highlighted.

Step 5: The Feedback Lesson

Hand assignments back, asking students to reread their work and to pay particular attention to what has been highlighted. Encourage students to pause over these highlights, considering why they might be highlighted.

Next, share the chosen examples of excellence. I do this by placing a blank template under a visualizer, live-modeling the example and verbalizing what precisely makes it excellent. If you don’t have a visualizer, you could just as easily type your comments onto a screen or write on the board. Use the notes you jotted down while reading student work as a point of reference. Here’s an example of live-modeled feedback .

As you live-model, students should follow along with you so that they have their own version. In many ways, this is the most important part of the entire process, so move slowly and carefully. Pause to ask questions, invite comments from students, and discuss together what makes “excellence” excellent.

Now, move on to next steps. Ask students to look at their individual targets, perhaps returning to their work to try to identify specific moments where they could change something to make it better. It’s likely that you would have used the same target for multiple students or maybe even just a handful across the class. Take a few moments to address these high-leverage areas for development, explaining what might’ve been done differently. It’s even better if you can link certain targets back to the examples of excellence already modeled.

Step 6: Complete a Task Together

As the lesson comes to a close, I like to finish with a final task that everyone completes. This “together task” might take many forms, but try to link it to the examples of excellence or an especially frequent next step. The goal is for students to practice deploying the skills you’ve addressed during the feedback lesson in a different but similar context to the original task.

And with this, the lesson ends. Consider how far we’ve come. We read and marked the work of an entire class in an hour. In the lesson itself, students engaged more fully with the feedback, reflecting on their work and coming to understand what defines excellence. No more scattered glances before pushing their graded work to one side, unread. And the teacher got their time back.

Skip to content

Effective feedback: Whole-class marking

- Research Summary

- Assessment |

- Effective instruction |

- Promoting good progress |

- Teacher Wellbeing

Teachers read a whole set of books – without marking each individual student’s work – and then share feedback as a whole-class activity in the following lesson.

What does it mean?

Originally inspired by the Michaela Community School (where the belief is that marking forces an over-reliance on teachers and wastes valuable teacher time), whole-class marking is now widely accepted as an efficient method of feedback.

Instead of writing individual comments in every student’s book (which is time-consuming and often ineffective), teachers read a set of books, make strategic notes and then give feedback to the whole class at once. This strategy is all about making students responsible for their own learning.

What are the implications for teachers?

This can save you a lot of marking time. Plan to read around 30 books in 15 minutes (meaning you should be able to read the writing of every child you teach once or twice a week).

Make strategic notes as you read. Things to note down include recurring spelling and grammar mistakes, names of students who need something following up individually, shared successes and individual triumphs (you can put a tick in the margin next to work you’d like students to read out) and common areas of weakness or misunderstanding. Try to give feedback as close to the time of writing as you can, ideally the following lesson, so that students can remember the original task. If you see lots of common spelling and grammar mistakes, teach the corrections – you could then test and encourage students to self-correct in their own work.

Share the positives and celebrate the most successful examples. If you have a visualiser available, use it to talk-through exactly what makes each piece so good. Model the most common weaknesses too. Discuss together how they can be improved and then ask the class to improve their own work in a different colour pen.

This method also works for in-class instant intervention. Circulate with your notepad during silent writing time and then use a mini-plenary to feedback halfway through the task.

Want to know more?

- Facer J (2016) Giving feedback the ‘Michaela’ way. Available at: https://readingallthebooks.com/2016/03/19/giving-feedback-the-michaela-way/ (accessed 26 October 2018).

- Kirby J (2015) Marking is a hornet. Available at: https://pragmaticreform.wordpress.com/2015/10/31/marking-is-a-hornet/ (accessed 26 October 2018).

- Strachan S (2017) Why I love whole-class feedback. Available at: https://susansenglish.wordpress.com/2017/10/23/why-i-lovewhole-class-feedback-other-time-saving-feedback-strategies/ (accessed 26 October 2018).

- Fletcher-Wood H (2017) Guiding student improvement without individual feedback. Impact 1 : 36–37.

Other content you may be interested in

Teachers’ engagement with research

We know thinking strategies improve learning, but how long should we spend teaching them?

Reading: Developing comprehension and inference

Teaching philanthropic citizenship

Could picture books improve your students’ language and literacy skills?

Journal clubs as an approach to teacher CPD

Curriculum design: Problem-centred curriculum

Research-informed practice: How to read an academic paper

Multilingual Thinking in Multicultural Classrooms

Assessment and feedback in an online context: Checking understanding

Pears Pavillion Corum Campus 41 Brunswick Square London WC1N 1AZ

[email protected] 020 3433 7624

Maths Tutoring Built for Schools

"This is one of the most effective interventions I have come across in my 27 years of teaching."

Hundreds of FREE online maths resources

Daily activities, ready-to-go lesson slides, SATs revision packs, video CPD and more!

Whole Class Feedback: How To Boost Learning In The Classroom [Includes FREE Template]

Rosie Hasyn

Whole class feedback (WCF) is one way in which you can improve the feedback process whilst reducing teacher workload .

In this blog we will explain how it can be an effective feedback tool and provide an example of how it can be used in maths. We have even included a downloadable feedback sheet for you to use in your classroom and an example of how to use it best.

What is whole class feedback?

What are the benefits of whole class feedback, 5 common misconceptions about whole class feedback, how to implement whole class feedback, tips for teachers to implement whole class feedback successfully.

Whole class feedback is a way for teachers to give feedback on student work without having to write individual comments in each student’s book. With WCF, the teacher reads through all the students’ work, makes a note of the things they did brilliantly and the areas where they could do with a bit of improvement and then shares this feedback with the entire class. The students then get the opportunity to respond to this feedback in their books, usually in the next lesson.

Whole Class Feedback Sheet Template & Example

Download this FREE whole class feedback template to improve your feedback process without adding to your workload

Whole class feedback example

Let’s say the teacher’s objective in a lesson was to instruct the pupils on how to determine non-unit fractions of amounts. While conducting the lesson, the teacher might observe that a considerable number of students are struggling with dividing by the denominator and multiplying by the numerator.

Using WCF as a guide, the teacher will help the students by discussing the issue at the beginning of the next lesson. They will remind the students of the success criteria and provide them with an opportunity to correct their mistakes and answer a similar question again.

There are several benefits to using WCF in class, including:

Reduces teacher workload

Rather than annotating each student’s book and writing time-consuming written comments, the teacher is able to reflect on common misconceptions and take notes on a single class feedback template.

Moves learning forwards

WCF encourages the teacher to assess learning in line with the destination. Rather than picking up on all small errors and writing wishy-washy comments, the teacher uses formative assessment to identify what needs to be addressed for learners to make progress in each unit of work.

Encourages children to reflect on their own work

By showing children what the common errors were at a whole class level, the onus is on them to identify where they may have gone wrong in their own piece of work. This encourages them to use the tools provided to fix it and helps embed children’s learning into their long-term memory.

Offers the opportunity to deepen learning

High quality WCF enables children to internalise the success criteria. Through identifying their own mistakes and applying the success criteria to different problems, children become more fluent in the steps to success. You can find out more about how this works in our blog on having a no marking policy .

Although WCF is a widely accepted feedback approach, there are still various misconceptions surrounding it.

1. Whole class feedback ignores some errors and misconceptions

There is concern that condensing up to 32 children’s work into one or two feedback points will overlook other errors and misconceptions. However, more marking does not equate to high quality, as children may not know what corrections to focus on, or may not bother reflecting on their work at all.

In an already tight teaching schedule, highlighting the most important misconceptions and giving children an opportunity to address these knowing it will help them move forwards will ensure time is used effectively. Other misconceptions can be addressed separately through individual/ small group interventions.

2. Whole class feedback is vague

As highlighted by Christodoulou , WCF runs the risk of providing the whole class time to reflect on vague comments that mean little to them e.g. ‘be more systematic’. Hence, it is paramount that effective feedback is accessible to children and makes them think.

Primary school pupils need effective modelling of how to tackle a problem, followed by time to fix errors in their previous work and deepen their understanding through further examples.

3. Whole class feedback replaces other types of feedback

Though it can be a useful tool that seriously reduces teacher workload , WCF should not be used in isolation.

In order to pick up small errors and provide tailored support, live marking should be used throughout lesson time to ensure learning is moving in the right direction. In doing so, teachers may find opportunities for on the spot whole class feedback (or mini-plenaries) where common issues keep arising.

4. Whole class feedback lowers ability children and children with SEND are disadvantaged

Of course, in any classroom there will be some children who need additional support to access their learning and may struggle to think critically. Therefore, as per the previous point, WCF is not an approach that can be used in isolation. Some children will need individual feedback if they are working at a significantly different level.

This is where adaptive teaching comes in; don’t be afraid to have a temporary reshuffle of groups during feedback sessions to ensure certain children have access to adult support. Effective deployment of teaching assistants in class can also have a very positive impact for these children.

5. Whole class feedback is just another fad

We have all sat in CPD sessions during our teaching careers and have wondered if a new approach you are being encouraged to use is really going to stick or if it will fizzle out by the end of the school year. Implemented properly, without too much rigidity, WCF can create lasting change.

You may need a different feedback template for different subjects. You may need to adapt how you share the feedback depending on the misconception. You may find that what works for one class, doesn’t for another.

Whole class feedback should not be a process of sticking a one-size fits all comment sheet into everyone’s books – instead, it is essential to focus on how pupils can progress with their learning by reflecting on misconceptions.

Whole class feedback has been packaged differently depending on who is writing, but ultimately it requires the following 3 steps:

Step 1: Identify misconceptions and praise

Following a lesson, you should read through all the children’s books, identify any recurring misconceptions and note them down on a whole class feedback template – you can download our whole class feedback template for free here!

This template should include your lesson’s learning objective to ensure that the feedback is related to it. It should also include your ultimate learning destination to show children where they are heading towards by responding to your feedback.

In the main body of the template, you should include space for praise. You might just jot down a name and a quick note of what they did as a reminder to share with the class in the following lesson.

For example, you may praise a child for writing place value headings above their column subtraction problem, keeping the calculation organised and accurate. Other areas for praise may be in some of their mathematical explanations or, if in KS1, aspects such as writing numbers round the right way or presenting work as instructed.

Most importantly, you should also include one or two of the most critical misconceptions noticed across the class. On the same feedback sheet, you can write down the steps to success (which should align with what was taught in the lesson) so that the students can use this to make their corrections.

Step 2: Plan how you will share feedback

After reflecting on the misconceptions the children made, you need to plan how you are going to share your feedback and direct children during their reflection time. You may include this information on a slide at the start of the lesson or prepare a separate sheet of questions for the pupils.

As whole class feedback is rooted in ensuring individual students reflect on their own work, you may first direct children to check their own work for errors. For instance, you could ask all children to check their answer for the given question. If they have made the error identified by you they can try again, ideally in a different colour pen or pencil.

Following this, you may present them with similar questions to practise using the success criteria again, and you can challenge them even further with reasoning or problem solving questions. For example, you could ask them to correct a fictional child’s mistakes.

In some lessons, this may be a short starter activity. However, if the misconception needs more attention, it may be necessary to dedicate more time to it. As a result, you should consider the sequencing of future lessons in the unit.

Stuck for questions? Third Space Learning provides numerous free resources for you to use in your classroom.

Step 3: Address the classroom

The final step in WCF passes the onus from the teacher to the pupil.

First, the teacher needs to share their feedback with the class. This could be in the first lesson slide – with notes either typed up or scanned in. Alternatively, you may choose to share your notes under a visualiser. A visualiser can be an efficient way to share good examples of children’s work that you noted down on the feedback sheet.

During this teacher-led discussion, it is important to model to pupils how to use the success criteria to overcome the misconception. This then enables them to review their own answers either independently or with a partner.

By recording this in another colour, it is clear to the teacher whether the child has applied the feedback or not. Once their corrections have been addressed, the ‘next steps’ section of the feedback sheet will direct them to the aforementioned extension questions to embed their knowledge further. This may be done in their books or alternatively on a mini-whiteboard .

Here are some tips for teachers to maximise the effectiveness of whole class feedback:

1. Define your learning goal for feedback

There is no point in dedicating whole class feedback to something indirectly related to the learning objective. For example, a handful of arithmetic errors should not be the focus of column subtraction feedback if the learning objective was to use exchanging.

In contrast, if the long-term goal is for children to solve word problems but their understanding of how to extract information from these questions is not robust, this could be incorporated into your feedback sheet.

2. Consider your success criteria

To help children internalise a process, it is essential that the steps are laid out clearly and consistently. The success criteria first taught in the lesson should also double up as a way for them to diagnose their mistakes.

3. Be flexible in your approach

WCF is not one size fits all approach and no lesson will be – or should be – the same. Sometimes just a short feedback session is required, whereas other times you may want to spend more time addressing misconceptions before moving learning forward.

4. Keep it simple

If you search for whole class feedback sheets online, you will find a number of beautifully presented crib sheets. However, these can sometimes overcomplicate the process. If you can’t work out what should go in each box, you cannot expect the children in your class to know how to read it.

5. Choose a feedback method that works for you

We all have different teaching styles and what comes naturally to one teacher may feel alien to another.

Whether you prefer using a visualiser, having it scanned in on slides or keeping it more paper based, do what works for you and your class. As long as the feedback is explained to the children and they have the opportunity to respond, you are on the way to high quality WCF.

Yes – but it is essential that it is thought through and structured to support children to overcome misconceptions and move learning forwards. By following the steps of identify, plan, address, the children in your class will be able to deepen their understanding whilst significantly reducing your workload.

When used effectively, whole class feedback can significantly reduce teacher workload by stripping feedback down to the bare minimum. This simultaneously benefits the pupil as feedback is focussed on moving their learning forwards and puts the onus on them to apply what has been signposted to them.

DO YOU HAVE STUDENTS WHO NEED MORE SUPPORT IN MATHS?

Every week Third Space Learning’s maths specialist tutors support thousands of students across hundreds of schools with weekly maths tuition designed to plug gaps and boost progress.

Since 2013 these personalised one to one lessons have helped over 150,000 primary and secondary students become more confident, able mathematicians.

Learn how we can teach multiple pupils at once or request a personalised quote for your school to speak to us about your school’s needs and how we can help.

Related articles

A Teacher’s Guide To Spaced Repetition And Creating An Effective Spaced Repetition Schedule

Retrieval Practice: A Foolproof Method To Improve Student Retention and Recall

A Practical Guide To Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction: How To Apply Them to Maths Lessons

Cognitive Load Theory: A Practical Guide And Tips For Teachers

FREE Guide to Hands on Manipulatives

Download our free guide to manipulatives that you can use in the maths classroom.

Includes 15 of the best concrete resources every KS1 and KS2 classroom should have.

Privacy Overview

Cut down your marking time by using whole-class feedback

Whole-class feedback offers three advantages – it’s time saving, it encourages self-regulation and will help identify any weaknesses in the rubric. Paul Moss shows how it’s done

Created in partnership with

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} Emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn?

A diy guide to starting your own journal, universities, ai and the common good, artificial intelligence and academic integrity: striking a balance, create an onboarding programme for neurodivergent students.

Providing quality feedback is a key part of assessment. But it also takes time that many educators don’t have.

Whole class feedback is a method a marker can use to increase the efficiency of marking a large number of assessments. The marker uses a rubric as per normal to address criteria, but instead of adding detailed and often repeated comments where they see gaps or strengths in students’ work, they undertake mini qualitative data analysis and look for patterns or themes in the responses. These findings are then presented to all students as an attachment to their assessment, and students are encouraged to use both these and the rubric indications to evaluate their own performance against the assessment’s intentions.

How to do whole-class feedback

- Prime students with clear explanations and examples of how you will use whole-class feedback when marking their assignments well before marking begins.

- Model for them how they should use the whole-class feedback to self-evaluate their grades.

- If you have multiple markers who mark for their own tutor group, provide them with instructions on how they should use whole-class marking.

- During marking, write down observations of responses to criteria and categorise them so they align with the rubric criteria.

- Assign grades in the rubric as you would, but instead of commenting on each criterion or at the end, add a link to the whole-class feedback document, or as an announcement when releasing the grades.

- If you are a casual marker, provide your feedback to the course coordinator.

Saving time

Saving time in the writing of comments by using a predefined bank of comments is not a new method, but its downside is that the comments can seem disconnected from the work and not contextually relevant or useful in helping students understand how their assessment has been graded. More importantly, students are left unclear about how this feedback will help them in their next assessment.

- Four directions for assessment redesign in the age of generative AI

- Written feedback for students – keep it clear, constructive and to the point

- How consensus grading can help build a generation of critical thinkers

Whole-class feedback is more precise. The comments emerge through the marking process as the marker observes patterns of responses. If the rubric is written well enough , then at the individual level it does most of the talking through the criteria. If you have made your students aware of the whole-class feedback approach, they can use the rubric indications and cross-check them against the whole-class feedback document to evaluate their performance and understand the grade they received.

Encouraging self-regulatory learning

There will still be some occasions where an individual comment will be necessary, usually when a student has seriously misunderstood a criterion. But these occurrences will be in the minority and not cut into the overall saving in marking time. By providing the opportunity for students to be active in understanding their feedback by cross-referencing the rubric grade against the whole-class feedback, you will encourage greater self-regulatory behaviour. Instead of just seeing the grade and moving on, having to work at understanding why a grade was received places the student in a stronger position to be able to act on their findings in future assessments. Of course, some will not go to these lengths and only view their grades, but this is what such a student would do anyway, regardless of how much time and energy you spend providing written feedback.

Closing gaps

Another benefit of this approach is that it helps identify if the rubric is fit for purpose. Whole-class feedback may uncover that some or all of the criteria are not providing enough guidance for the students. Some tweaks in the writing of the descriptions or, in fact, the writing of a criterion itself may be needed, as the pattern of student responses highlights that the intention of the criterion is not coming across. If it’s not the criterion that needs to be adjusted, the learning sequence related to the criterion may need to be rethought, or further resources provided to learners.

Perhaps less frequently, it may be that the pattern of responses indicates that the entire assessment is not achieving what you had hoped it would achieve in meeting course learning outcomes. Whole-class feedback provides you with real-time contextualised action research to inform such decisions.

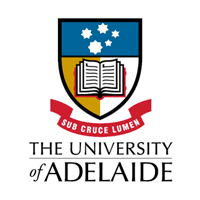

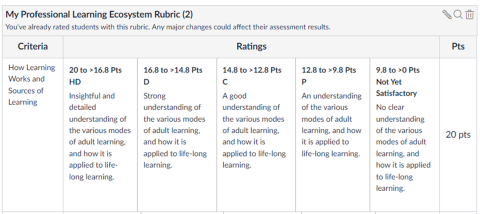

Worked example

In the example below, taken from a recent assessment, the comments you see are from my observations of how students responded to two of the rubric criteria, the first asking them to discuss and describe their understanding of “How learning works” through the use of a case study, and the second a “writing” criterion.

‘How learning works’ criterion

- Students who didn’t discuss particular aspects of the learning process that were emphasised repeatedly throughout the course did not do as well as those who did in that section.

- Students who explicitly made the connection between how learning works and its implications for future behaviours received a stronger grade. This is because the assignment is about learning, and to put plans into action they needed to consider how learning happens. For example, the learning concept of repetition (interrupting the forgetting curve) would be useful to turn an action into a habit, a necessity when changing behaviour patterns.

- Students who only discussed when learning occurs rather than how it occurs did not receive the strongest grades in that section

- Those who didn’t discuss the case study character in the learning section were not able to receive an high distinction grade in that section.

Writing criterion

- Those who constructed a strong opening and introduction and followed through on what they said they would discuss in the report succeeded more than those who didn’t.

- If a section was too short it didn’t get a strong grade.

When referencing, they didn’t get full marks if:

- References weren’t in alphabetical order

- There were five references (or fewer) – not enough evidence to suggest a pattern

- They didn’t follow the Harvard model

- Dates did not follow the model

- In-text citation was incorrect

- Some referencing was correct but not all

- Italics were used inconsistently.

Paul Moss is learning design and capability manager at the University of Adelaide.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter .

Emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn?

Global perspectives: navigating challenges in higher education across borders, how to help young women see themselves as coders, contextual learning: linking learning to the real world, authentic assessment in higher education and the role of digital creative technologies, how hard can it be testing ai detection tools.

Register for free

and unlock a host of features on the THE site

Search menu

Whole-class feedback: practical tips and ideas.

Whole-class feedback is a highly effective and efficient way to ensure that your classes overcome misconceptions. Those who have adopted the approach have seen, first-hand, the impact it can have on students’ progress and, just as importantly, on teacher workload.

Whole-class feedback is something that requires a shift in mindset away from the shackles of the traditional approach to marking. Once freed, you quickly see the merits in addressing misconceptions as a collective.

However, for all its merits, whole-class feedback cannot be seen as a silver bullet. If we are not careful with our application, this approach could (and I use the modal verb tentatively here) take a turn down the dark path that we see so many educational fads go down.

Gradual watering down and too much emphasis on an approach can mean that it becomes detached and isolated from its roots. So remember that whole-class feedback is a tool which should be used in conjunction with other feedback methods – on its own, it is not enough.

So what does good whole-class feedback look like and how do we avoid it becoming a tokenistic exercise?

Identifying misconceptions

The terminal point in the whole-class feedback process is, more often than not, the sheet or resource that the class is given to help them overcome the misconception that you have identified.

How you fill in this sheet is of paramount importance. The content that is being covered needs to be accurate, tailored and relevant to the learners in that classroom.

Too many times I have seen teachers using general or common misconceptions in whole-class feedback and, in turn, the learning has not been anywhere as impactful as it might have been if the teacher had identified the specific misconceptions for that group of pupils.

To effectively identify the misconceptions, whole-class feedback must be informed by tracking, not watching. This can be supported by a simple tracking sheet to prompt you about what the misconceptions are as they arise in the lesson. This means that you can make more informed decisions about what you address there and then in class and what you leave to your whole-class feedback sheet.

It may be that you decide upon verbal whole-class feedback, especially if there is a common misconception across the whole class. The more informed you are, the more responsive you can be with the learners in front of you.

Live marking

One of the drawbacks of whole-class feedback is that individuals do not get the specific feedback they may need on their own work to progress. Although misconceptions are addressed generally, it is that close-level feedback that can be lacking.

This is why whole-class feedback should be blended with approaches such as live marking.

Live marking has (thankfully) become commonplace in many schools – by which I mean quite simply giving feedback and marking in-class while students are working.

The approach is something that I have been vehemently banging the drum about for years now. Once embedded, it strips workload right back and increases efficiency. I have written specifically about this approach in SecEd, Headteacher Update's sister magazine (see Riches, 2017) .

When live marking, you are able to assess misconceptions and identify the trends across the class, meaning that you can be gathering data for your whole-class feedback sheet during the lesson.

Thanks to this dual approach, I have not had to look at books outside lessons for years: whole-class feedback helps cover the common misconceptions on an overall level and then other feedback methods help you to drill-down with individual students.

Live marking is just one example that has always worked well for me, but there are many other things you can do to get the detailed individual feedback in.

Responsive questioning

But there is a warning: having a uniform way of identifying and overcoming misconceptions can create complacency when it comes to other methods of tackling misconceptions.

What is important is that whole-class feedback approaches do not replace the high-quality, rich discussions that should happen around misconceptions as and when they arise during lessons.

An effective whole-class feedback approach relies heavily on consistency and conformity. Having well-embedded habits for learning is important, but we must not detach misconceptions from other phases of learning, especially questioning.

We must ensure that we continue to address misconceptions using our normal teaching pedagogies, including questioning; we don’t want students to get into the habit of assuming they can only reflect on what they don’t understand during certain exercises or times of the lesson.

By questioning responsively and adapting to the needs of the students in front of us, we are able to help them overcome misconceptions before the formal whole-class feedback phase. In some ways, responsive questioning could be seen as interim whole-class feedback.

Bigger picture planning

The big, big thing with whole-class feedback is that it needs to be carried out correctly. The teacher needs to teach the students to overcome the misconception and they need to track the misconceptions over time.

Tracking the misconceptions means that teachers can effectively interleave and interweave tasks to ensure that knowledge and understanding are supported and sustained to avoid the same misconceptions arising again.

The way you record this need not add to your workload – you can simply keep the sheets that you gave the class, or keep the notes you take when you are tracking during the lesson.

Avoid looking at whole-class feedback as something that is a classroom exercise done at a singular point in time. Whole-class feedback informs your future planning, it informs you about how you need to adapt your teaching, and it shows you exactly what you need to check up on in the coming lessons, weeks and months.

Yes, the primary function of whole-class feedback is to help learners overcome the misconception, but it also has a powerful secondary purpose – when coupled with effective recall planning, the likeliness of repeated misconceptions is significantly reduced.

Final words

Whole-class feedback is an exceptionally helpful approach but is one piece of the puzzle. Used in conjunction with individual level marking and embedded in the wider planning of learning, its power is amplified significantly.

- Adam Riches is a senior leader for teaching and learning, a Specialist Leader in Education and author of Teach Smarter (Routledge, 2020). Follow him on Twitter @TeachMrRiches .

Further information & resources

- Riches: In-class marking and feedback, SecEd, November 2017: www.sec-ed.co.uk/best-practice/in-class-marking-and-feedback/

- SecEd: Adam Riches features in a recent episode of the SecEd Podcast dedicated to Quality First Teaching, April 2021: https://bit.ly/2R5PIT8

Related articles

Whole class feedback: strategies and experiences, best practice focus: effective feedback: a whole-school approach, effective roles for teaching assistants in whole-class work.

- Primary Hub

- Art & Design

- Design & Technology

- Health & Wellbeing

- Secondary Hub

- Citizenship

- Primary CPD

- Secondary CPD

- Book Awards

- All Products

- Primary Products

- Secondary Products

- School Trips

- Trip Directory

- Trips by Subject

- Trips by Type

- Trips by Region

- Submit a Trip Venue

Trending stories

Top results

- Whole Class Feedback A Short Guide To Making It Work For You

Whole class feedback – A short guide to making it work for you

It’s a teaching approach that can save you lots of time, says Adam Riches – so long you don’t over-complicate things…

Master whole class feedback and you’ll reduce your marking load significantly – it’s as simple as that.

Implementing a well-devised whole class feedback system is one of the most effective ways to move learning forwards sustainably, through addressing misconceptions and giving learners the opportunity to reflect on the topics they have been taught. Don’t be drawn in by gimmicks, though – be sure to keep things simple.

Consider the format

The format really does matter. A complicated sheet will only add to students’ extrinsic load, while a sheet that changes each week can create ambiguity for learners.

Make your whole class feedback method visible and consistent. A simple sheet with pre-assigned boxes – such as praise, literacy and most importantly, the misconception – is all that’s needed. You might wish to later embellish this with sections that further stretch and challenge your classes, but start with the basics.

Overcome the misconception

Whole class feedback is effective when learning time is dedicated to overcoming the misconception. Not all students need to have the misconception for this to add value to their learning; a good way of reinforcing what not to do is to reflect on common mistakes others make.

Whole class feedback allows you to help learners move on, as well as supporting others to consolidate. Explicitly teaching it is of paramount importance – merely identifying it isn’t enough!

Embed the routine

Making your whole class feedback visible is all about getting learners into routines. Keep your language consistent and dedicated, so that the feedback you give is acted upon. Do you expect learners to respond in a different colour? How often do you give feedback?

You also need to consider how you’ll gather the data required for your whole class feedback. Will you look through the books? Monitor progress in class? Make this a part of your teaching routine.

Adam Riches is a senior leader for teaching and learning; follow him at @teachmrriches

This piece originally appeared in ‘Learning Lab’ section of Teach Secondary magazine

Sign up to our newsletter

You'll also receive regular updates from Teachwire with free lesson plans, great new teaching ideas, offers and more. (You can unsubscribe at any time.)

Which sectors are you interested in?

Early Years

Thank you for signing up to our emails!

You might also be interested in...

Why join Teachwire?

Get what you need to become a better teacher with unlimited access to exclusive free classroom resources and expert CPD downloads.

Exclusive classroom resource downloads

Free worksheets and lesson plans

CPD downloads, written by experts

Resource packs to supercharge your planning

Special web-only magazine editions

Educational podcasts & resources

Access to free literacy webinars

Newsletters and offers

Create free account

By signing up you agree to our terms and conditions and privacy policy .

Already have an account? Log in here

Thanks, you're almost there

To help us show you teaching resources, downloads and more you’ll love, complete your profile below.

Welcome to Teachwire!

Set up your account.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Commodi nulla quos inventore beatae tenetur.

I would like to receive regular updates from Teachwire with free lesson plans, great new teaching ideas, offers and more. (You can unsubscribe at any time.)

Log in to Teachwire

Not registered with Teachwire? Sign up for free

Reset Password

Remembered your password? Login here

Establishing A Whole Class Feedback Model

According to Hattie, feedback provided via marking has an effect size of 0.791, with eight additional months’ progress potential for students 2. The albatross like burden of marking 3 means that good feedback is often difficult, with poor quality, generic, comments frequently seen 4 & 5.

Students often do not act upon feedback and fail to make progress 6 & 7 , as they may not understand actions to improve based on vague comments like ‘explain this’; guidance steps on how to ‘explain’ have not been given4, 6 & 8 . Marking individual student work therefore has limited effectiveness 9 and is a high teacher effort, low student impact method that Kirby 11 and Facer 12 liken to a hornet.

Additionally, the DfE13 marking review noted how it has ‘become common practice for teachers to provide extensive written comments on every piece of work when there is very little evidence that this improves student outcomes in the long term , especially when ‘driving pupil progress… can often be achieved without extensive written dialogue or comments’.

The authors also reported that the ‘obsessive nature, depth, and frequency of marking was having a negative effect on teachers’ ability to prepare and deliver outstanding lessons’ 6 . Therefore, it is important to find a low effort, high impact method of feedback that meets DfE guidelines that are not detrimental for teachers’ workload.

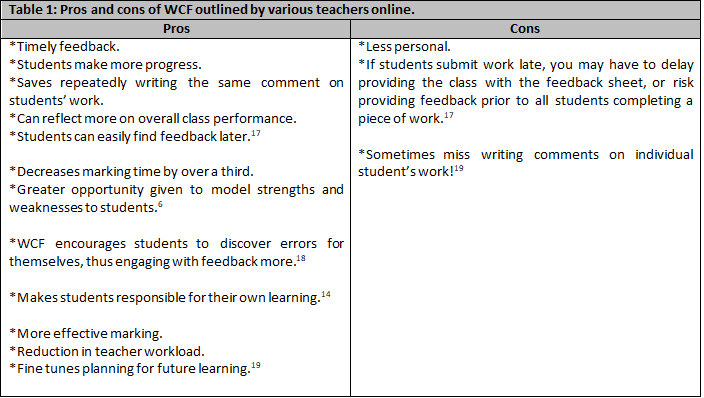

Low effort high impact

Whole class feedback (WCF) – a low effort, high impact, ‘butterfly’ method 11 – is a solution. Most work that exists on whole class feedback (WCF) is published on teachers’ blogs where they reflect on the effectiveness of this strategy, both for students and teacher workload – the pros and cons are outlined in Table 1.

The premise of WCF is outlined in Jones & Essery 6 , Sherrington & Stafford 14 , and Perciva l7 , amongst others: work is read through whilst making notes on a feedback sheet, with common errors, things done well etc. recorded. Nothing is written on work itself, though good work can be rewarded with a star in the margin so that a student can read out to the class as an example.

The time saved on marking is used to create feedback tasks, which are added to the sheet. Christodoulou 15 recommends that the feedback tasks should involve ‘a recipe, not a statement’ that is ‘specific and actionable’ 16 i.e. students know how to progress with more specific comments than ‘explain this’. The sheet is photocopied for students’ books and feedback should be provided as close to when the students completed the original task as possible, so they can remember the task and the maximum benefit is felt.

For the initial trial a commercial Doodle ‘Class Mark’ template 20 was used with two year 8 classes during Michaelmas term 2019. Overall, WCF was a much quicker method to mark a whole class set of assessments. However, the template is too informal and requires adjusting for Sevenoaks School. Some ‘boxes’ could be omitted, whilst others could be expanded to provide space for better quality feedback tasks for students to complete.

To develop a template, a focus group was held with year 8 to gather their views. Overall this was positive as students do not mind receiving feedback using WCF; occasionally students were unaware of what specific feedback applied to them; and students would prefer a space for the class average mark, and space to write their mark so they know how they compare and ‘how much they need to do to improve’ .

An audit of current use of WCF at Sevenoaks was subsequently conducted. Various types of feedback that could be classified as WCF are used by a variety of teachers across a range of departments. None use a template and it is usually written out on an ad-hoc basis. All teachers still write individual comments on students’ work and use WCF in addition, thus believing WCF hinders workload.

This reflects how reluctant teachers are to stop writing comments on student work – as they perceive this to be more accountable to observers 21 & 12. Encouraging a switch to WCF is a huge cultural shift for teacher and student alike. The audit was interesting to see what others do, though has not informed the creation of the template much as no other teacher uses one. It has, however, reinforced that WCF at Sevenoaks School will be a big change .

A Sevenoaks class feedback template was subsequently created drawing on experience of using the Doodle template, alongside exemplar templates from other teachers published online. The template was used with two year 9 and two year 8 Geography classes during Lent term 2020 – use in Summer term was curtailed by COVID-19.

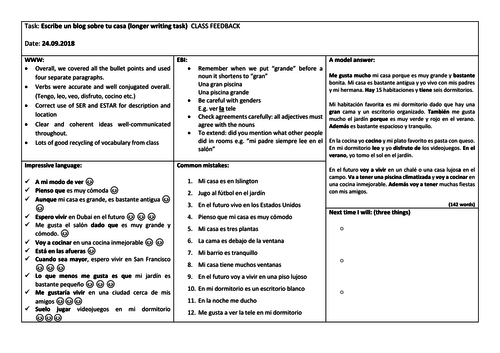

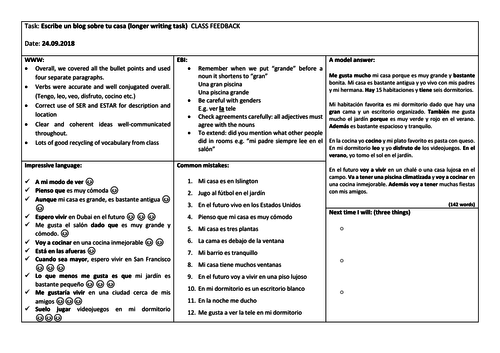

Initially the template contained space for what went well (WWW) and even better if (EBI) comments, feedforward tasks, and space for duplication of an excellent example of the piece of work which students could analyse to assist their understanding of the feedback and develop their metacognition. The template was revised with usage (figure 1), combining the WWW and EBI boxes into a ‘feedback’ box with statements that could be interpreted either positively or negatively dependant on whether they have a tick (WWW) or hashtag (EBI) next to them on student work.

This is as the WWW and EBI boxes were essentially duplicates of each other, thus still adding to workload. Initially WWW and EBI points were just bullet pointed, and students had to work out what feedback applied to them. Based on the focus group feedback, this evolved to have numbered points, with the corresponding number being annotated on the student’s work.

This was because some, especially lower ability, students found it difficult to engage with the feedback and work out what applied to them. The template does not have space for the average class mark as evidence suggests students will fixate on marks, rather than feedback, if given grades.

Whilst this is purely empirical evidence, after using the template for several months, students appear to be better at interrogating their own practise, self-assess more, and perform better in assessments than if they had not used WCF. Year 9 student feedback was that the Sevenoaks template was clear, well formatted, and stood out in their folders, which they liked.

Most students did not mind WCF. From a teacher’s perspective, WCF cuts down workload considerably enabling saved time to be spent on producing a higher quality feedback lesson, thus aiding student progress . After initial ‘set up’ and familiarisation with WCF students are quite self-sufficient with knowing what to do when they get an A5 light blue WCF sheet in class. Due to printing on coloured paper, teachers no longer worry about accountability in the eyes of observers as marking and feedback is easily recognised in folders.

The findings of this research project were published in the school’s Innovate journal for teaching and learning in October 2020. Whilst this is a small-scale research project that was curtailed by COVID-19, it was recommended that more teaching staff start using this template, or their own version of WCF, and work on developing meaningful feedforward tasks.