COPD Case Study: Patient Diagnosis and Treatment (2024)

by John Landry, BS, RRT | Updated: Apr 4, 2024

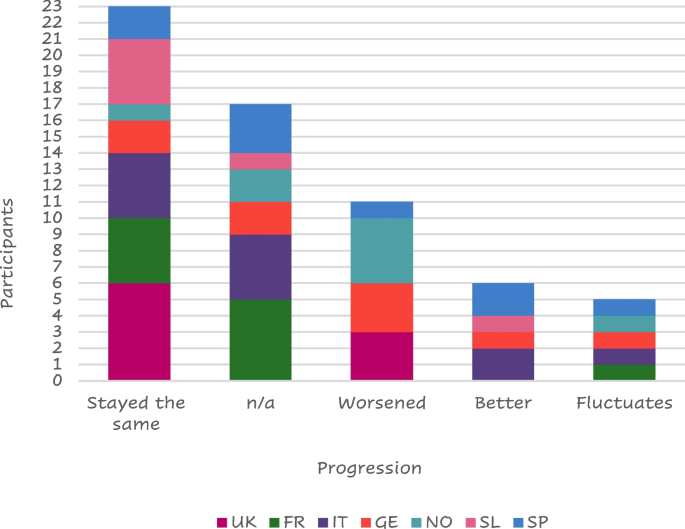

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive lung disease that affects millions of people around the world. It is primarily caused by smoking and is characterized by a persistent obstruction of airflow that worsens over time.

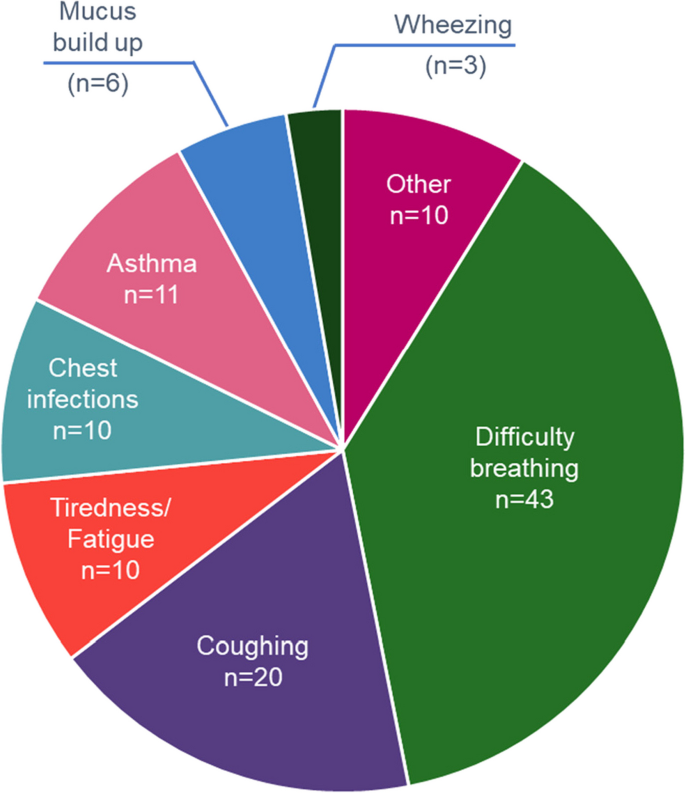

COPD can lead to a range of symptoms, including coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness, which can significantly impact a person’s quality of life.

This case study will review the diagnosis and treatment of an adult patient who presented with signs and symptoms of this condition.

25+ RRT Cheat Sheets and Quizzes

Get access to 25+ premium quizzes, mini-courses, and downloadable cheat sheets for FREE.

COPD Clinical Scenario

A 56-year-old male patient is in the ER with increased work of breathing. He felt mildly short of breath after waking this morning but became extremely dyspneic after climbing a few flights of stairs. He is even too short of breath to finish full sentences. His wife is present in the room and revealed that the patient has a history of liver failure, is allergic to penicillin, and has a 15-pack-year smoking history. She also stated that he builds cabinets for a living and is constantly required to work around a lot of fine dust and debris.

Physical Findings

On physical examination, the patient showed the following signs and symptoms:

- His pupils are equal and reactive to light.

- He is alert and oriented.

- He is breathing through pursed lips.

- His trachea is positioned in the midline, and no jugular venous distention is present.

Vital Signs

- Heart rate: 92 beats/min

- Respiratory rate: 22 breaths/min

Chest Assessment

- He has a larger-than-normal anterior-posterior chest diameter.

- He demonstrates bilateral chest expansion.

- He demonstrates a prolonged expiratory phase and diminished breath sounds during auscultation.

- He is showing signs of subcostal retractions.

- Chest palpation reveals no tactile fremitus.

- Chest percussion reveals increased resonance.

- His abdomen is soft and tender.

- No distention is present.

Extremities

- His capillary refill time is two seconds.

- Digital clubbing is present in his fingertips.

- There are no signs of pedal edema.

- His skin appears to have a yellow tint.

Lab and Radiology Results

- ABG results: pH 7.35 mmHg, PaCO2 59 mmHg, HCO3 30 mEq/L, and PaO2 64 mmHg.

- Chest x-ray: Flat diaphragm, increased retrosternal space, dark lung fields, slight hypertrophy of the right ventricle, and a narrow heart.

- Blood work: RBC 6.5 mill/m3, Hb 19 g/100 mL, and Hct 57%.

Based on the information given, the patient likely has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) .

The key findings that point to this diagnosis include:

- Barrel chest

- A long expiratory time

- Diminished breath sounds

- Use of accessory muscles while breathing

- Digital clubbing

- Pursed lip breathing

- History of smoking

- Exposure to dust from work

What Findings are Relevant to the Patient’s COPD Diagnosis?

The patient’s chest x-ray showed classic signs of chronic COPD, which include hyperexpansion, dark lung fields, and a narrow heart.

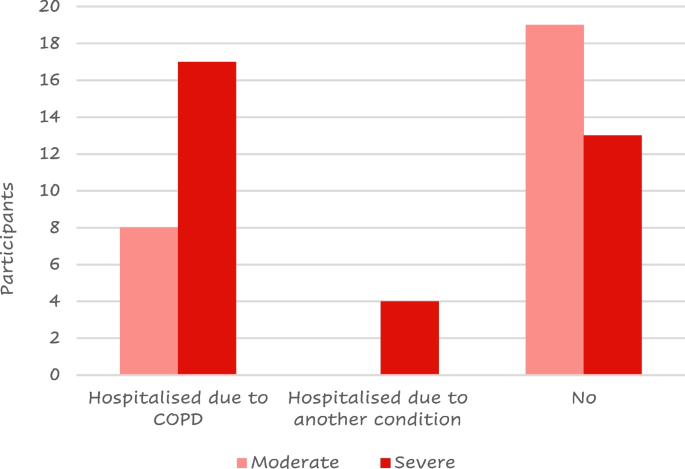

This patient does not have a history of cor pulmonale ; however, the findings revealed hypertrophy of the right ventricle. This is something that should be further investigated as right-sided heart failure is common in patients with COPD.

The lab values that suggest the patient has COPD include increased RBC, Hct, and Hb levels, which are signs of chronic hypoxemia.

Furthermore, the patient’s ABG results indicate COPD is present because the interpretation reveals compensated respiratory acidosis with mild hypoxemia. Compensated blood gases indicate an issue that has been present for an extended period of time.

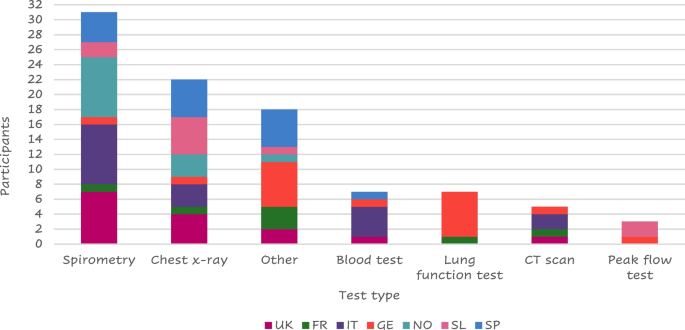

What Tests Could Further Support This Diagnosis?

A series of pulmonary function tests (PFT) would be useful for assessing the patient’s lung volumes and capacities. This would help confirm the diagnosis of COPD and inform you of the severity.

Note: COPD patients typically have an FEV1/FVC ratio of < 70%, with an FEV1 that is < 80%.

The initial treatment for this patient should involve the administration of low-flow oxygen to treat or prevent hypoxemia .

It’s acceptable to start with a nasal cannula at 1-2 L/min. However, it’s often recommended to use an air-entrainment mask on COPD patients in order to provide an exact FiO2.

Either way, you should start with the lowest possible FiO2 that can maintain adequate oxygenation and titrate based on the patient’s response.

Example: Let’s say you start the patient with an FiO2 of 28% via air-entrainment mask but increase it to 32% due to no improvement. The SpO2 originally was 84% but now has decreased to 80%, and his retractions are worsening. This patient is sitting in the tripod position and continues to demonstrate pursed-lip breathing. Another blood gas was collected, and the results show a PaCO2 of 65 mmHg and a PaO2 of 59 mmHg.

What Do You Recommend?

The patient has an increased work of breathing, and their condition is clearly getting worse. The latest ABG results confirmed this with an increased PaCO2 and a PaO2 that is decreasing.

This indicates that the patient needs further assistance with both ventilation and oxygenation .

Note: In general, mechanical ventilation should be avoided in patients with COPD (if possible) because they are often difficult to wean from the machine.

Therefore, at this time, the most appropriate treatment method is noninvasive ventilation (e.g., BiPAP).

Initial BiPAP Settings

In general, the most commonly recommended initial BiPAP settings for an adult patient include this following:

- IPAP: 8–12 cmH2O

- EPAP: 5–8 cmH2O

- Rate: 10–12 breaths/min

- FiO2: Whatever they were previously on

For example, let’s say you initiate BiPAP with an IPAP of 10 cmH20, an EPAP of 5 cmH2O, a rate of 12, and an FiO2 of 32% (since that is what he was previously getting).

After 30 minutes on the machine, the physician requested another ABG to be drawn, which revealed acute respiratory acidosis with mild hypoxemia.

What Adjustments to BiPAP Settings Would You Recommend?

The latest ABG results indicate that two parameters must be corrected:

- Increased PaCO2

- Decreased PaO2

You can address the PaO2 by increasing either the FiO2 or EPAP setting. EPAP functions as PEEP, which is effective in increasing oxygenation.

The PaCO2 can be lowered by increasing the IPAP setting. By doing so, it helps to increase the patient’s tidal volume, which increased their expired CO2.

Note: In general, when making adjustments to a patient’s BiPAP settings, it’s acceptable to increase the pressure in increments of 2 cmH2O and the FiO2 setting in 5% increments.

Oxygenation

To improve the patient’s oxygenation , you can increase the EPAP setting to 7 cmH2O. This would decrease the pressure support by 2 cmH2O because it’s essentially the difference between the IPAP and EPAP.

Therefore, if you increase the EPAP, you must also increase the IPAP by the same amount to maintain the same pressure support level.

Ventilation

However, this patient also has an increased PaCO2 , which means that you must increase the IPAP setting to blow off more CO2. Therefore, you can adjust the pressure settings on the machine as follows:

- IPAP: 14 cmH2O

- EPAP: 7 cmH2O

After making these changes and performing an assessment , you can see that the patient’s condition is improving.

Two days later, the patient has been successfully weaned off the BiPAP machine and no longer needs oxygen support. He is now ready to be discharged.

The doctor wants you to recommend home therapy and treatment modalities that could benefit this patient.

What Home Therapy Would You Recommend?

You can recommend home oxygen therapy if the patient’s PaO2 drops below 55 mmHg or their SpO2 drops below 88% more than twice in a three-week period.

Remember: You must use a conservative approach when administering oxygen to a patient with COPD.

Pharmacology

You may also consider the following pharmacological agents:

- Short-acting bronchodilators (e.g., Albuterol)

- Long-acting bronchodilators (e.g., Formoterol)

- Anticholinergic agents (e.g., Ipratropium bromide)

- Inhaled corticosteroids (e.g., Budesonide)

- Methylxanthine agents (e.g., Theophylline)

In addition, education on smoking cessation is also important for patients who smoke. Nicotine replacement therapy may also be indicated.

In some cases, bronchial hygiene therapy should be recommended to help with secretion clearance (e.g., positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy).

It’s also important to instruct the patient to stay active, maintain a healthy diet, avoid infections, and get an annual flu vaccine. Lastly, some COPD patients may benefit from cardiopulmonary rehabilitation .

By taking all of these factors into consideration, you can better manage this patient’s COPD and improve their quality of life.

Final Thoughts

There are two key points to remember when treating a patient with COPD. First, you must always be mindful of the amount of oxygen being delivered to keep the FiO2 as low as possible.

Second, you should use noninvasive ventilation, if possible, before performing intubation and conventional mechanical ventilation . Too much oxygen can knock out the patient’s drive to breathe, and once intubated, these patients can be difficult to wean from the ventilator .

Furthermore, once the patient is ready to be discharged, you must ensure that you are sending them home with the proper medications and home treatments to avoid readmission.

Written by:

John Landry is a registered respiratory therapist from Memphis, TN, and has a bachelor's degree in kinesiology. He enjoys using evidence-based research to help others breathe easier and live a healthier life.

- Faarc, Kacmarek Robert PhD Rrt, et al. Egan’s Fundamentals of Respiratory Care. 12th ed., Mosby, 2020.

- Chang, David. Clinical Application of Mechanical Ventilation . 4th ed., Cengage Learning, 2013.

- Rrt, Cairo J. PhD. Pilbeam’s Mechanical Ventilation: Physiological and Clinical Applications. 7th ed., Mosby, 2019.

- Faarc, Gardenhire Douglas EdD Rrt-Nps. Rau’s Respiratory Care Pharmacology. 10th ed., Mosby, 2019.

- Faarc, Heuer Al PhD Mba Rrt Rpft. Wilkins’ Clinical Assessment in Respiratory Care. 8th ed., Mosby, 2017.

- Rrt, Des Terry Jardins MEd, and Burton George Md Facp Fccp Faarc. Clinical Manifestations and Assessment of Respiratory Disease. 8th ed., Mosby, 2019.

Recommended Reading

How to prepare for the clinical simulations exam (cse), faqs about the clinical simulation exam (cse), 7+ mistakes to avoid on the clinical simulation exam (cse), copd exacerbation: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, epiglottitis scenario: clinical simulation exam (practice problem), guillain barré syndrome case study: clinical simulation scenario, drugs and medications to avoid if you have copd, the pros and cons of the zephyr valve procedure, the 50+ diseases to learn for the clinical sims exam (cse).

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Case Study (60 min)

Watch More! Unlock the full videos with a FREE trial

Included In This Lesson

Study tools.

Access More! View the full outline and transcript with a FREE trial

Mr. Whaley is a 65-year-old man with a history of COPD who presents to his primary care provider’s (PCP) office complaining of a productive cough off and on for 2 years and shortness of breath for the last 3 days. He reports that he has had several chest colds in the last few years, but this time it won’t go away. His wife says he has been feverish for a few days, but doesn’t have a specific temperature to report. He reports smoking a pack of cigarettes a day for 25 years plus the occasional cigar.

What nursing assessments should be performed at this time for Mr. Whaley?

- Full set of vital signs, including SpO2

- Heart and Lung sounds

- Gather any further details of illness or medical history, including allergies

Upon further assessment, Mr. Whaley has crackles throughout the lower lobes of his lungs, with occasional expiratory wheezes throughout the lung fields. His vital signs are as follows:

BP 142/86 mmHg HR 102 bpm

RR 32 bpm Temp 38.8°C

SpO 2 86% on room air

The nurse locates a portable oxygen tank and places the patient on 2 lpm oxygen via nasal cannula. Based on these findings, Mr. Whaley’s PCP decides to call an ambulance to send Mr. Whaley to the Emergency Department (ED). While waiting for the ambulance, the nurse repeats the SpO 2 and finds Mr. Whaley’s SpO 2 is only 89%. She increases his oxygen to 4 lpm, rechecks and notes an SpO 2 of 95%. The ambulance crew arrives, the nurse reports to them that the patient was short of breath and hypoxic, but sats are now 95% and he is resting. Per EMS, he is alert and oriented x 3.

What is going on with Mr. Whaley, physiologically?

- Mr. Whaley may have a lung infection, as evidenced by his fever and productive cough. This is causing a COPD exacerbation. COPD makes gas exchange difficult, which is why his SpO2 levels are low.

What would you have done differently? Why?

- Because of his COPD, Mr. Whaley should not have been placed on more than 2 lpm of supplemental O2 because it would decrease his respiratory drive and lead to CO2 toxicity.

- When Mr. Whaley’s sats didn’t improve, should have notified provider before adding more supplemental oxygen

Upon arrival to the ED, the RN finds Mr. Whaley is somnolent and difficult to arouse. He takes a set of vital signs and finds the following:

BP 138/78 mmHg HR 96 bpm

RR 16 bpm Temp 38.4°C

SpO 2 96% on 4 lpm nasal cannula

What is the possible cause of Mr. Whaley’s somnolence?

- His COPD makes gas exchange difficult, therefore he retains CO2. This means his respiratory drive to breathe is low O2 instead of high CO2. When the nurse gave too much supplemental oxygen, Mr. Whaley lost some of his respiratory drive. This is why his respiratory rate is so low.

- This can lead to CO2 toxicity, which presents as a decreased LOC and decreased respiratory rate, and can lead to the patient not protecting their airway and going into respiratory arrest

What orders do you expect from the ED provider?

- To remove the supplemental oxygen and only keep SpO2 between 88-92% to avoid over-oxygenating and CO2 toxicity

- Chest X-ray

- Blood Cultures, Sputum Cultures, CBC, BMP, ABG

- Bronchodilators, Corticosteroids, Breathing treatments from Respiratory Therapy

The provider writes the following orders:

Keep sats 88-92%

Labs: ABG, CBC, BMP

Insert peripheral IV

Albuterol nebulizer 2.5mg

Budesonide-formoterol 160/4.5 mcg

The nurse immediately removes the supplemental oxygen from Mr. Whaley and attempts to stimulate him awake. Mr. Whaley is still quite drowsy, but is able to awake long enough to state his full name. The nurse inserts a peripheral IV and draws the CBC and BMP, while the Respiratory Therapist (RT) draws an arterial blood gas (ABG). Blood gas results are as follows:

pCO 2 58 mmHg

HCO 3 – 30 mEq/L

pO 2 50 mmHg

Mr. Whaley’s chest x-ray shows consolidation in bilateral lower lobes.

Interpret the ABG. Explain.

- This is respiratory acidosis with partial compensation

- The ABG also shows hypoxemia

- Mr. Whaley retains CO2 chronically and his kidneys have tried to compensate (as evidenced by the HCO3- of 30 mEq/L). They weren’t able to fully compensate, though, so his pH is still acidic because of the high CO2

Which medication should be administered first? Why?

- Albuterol – because it is a bronchodilator and should always be administered before corticosteroids

Mr. Whaley’s condition improves after a bronchodilator and corticosteroid breathing treatment. His SpO 2 remains 90% on room air and his shortness of breath has significantly decreased. He is still running a fever of 38.3°C. The ED provider orders broad spectrum antibiotics for a likely pneumonia, which may have caused this COPD exacerbation. The provider also orders two inhalers for Mr. Whaley, one bronchodilator and one corticosteroid. Satisfied with his quick improvement, the provider decides it is safe for Mr. Whaley to recover at home with proper instructions for his medications and follow up from his PCP.

What are priority discharge teaching topics for Mr. Whaley?

- Mr. Whaley NEEDS to stop smoking!!!

- Proper use of inhalers, new medication instructions

- Reporting s/s respiratory infection to PCP sooner

- Pursed lip breathing and small, frequent meals to prevent shortness of breath

View the FULL Outline

When you start a FREE trial you gain access to the full outline as well as:

- SIMCLEX (NCLEX Simulator)

- 6,500+ Practice NCLEX Questions

- 2,000+ HD Videos

- 300+ Nursing Cheatsheets

“Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!”

Nursing Case Studies

This nursing case study course is designed to help nursing students build critical thinking. Each case study was written by experienced nurses with first hand knowledge of the “real-world” disease process. To help you increase your nursing clinical judgement (critical thinking), each unfolding nursing case study includes answers laid out by Blooms Taxonomy to help you see that you are progressing to clinical analysis.We encourage you to read the case study and really through the “critical thinking checks” as this is where the real learning occurs. If you get tripped up by a specific question, no worries, just dig into an associated lesson on the topic and reinforce your understanding. In the end, that is what nursing case studies are all about – growing in your clinical judgement.

Nursing Case Studies Introduction

Cardiac nursing case studies.

- 6 Questions

- 7 Questions

- 5 Questions

- 4 Questions

GI/GU Nursing Case Studies

- 2 Questions

- 8 Questions

Obstetrics Nursing Case Studies

Respiratory nursing case studies.

- 10 Questions

Pediatrics Nursing Case Studies

- 3 Questions

- 12 Questions

Neuro Nursing Case Studies

Mental health nursing case studies.

- 9 Questions

Metabolic/Endocrine Nursing Case Studies

Other nursing case studies.

- Login / Register

‘Let’s hear it for the midwives and everything they do’

STEVE FORD, EDITOR

- You are here: COPD

Diagnosis and management of COPD: a case study

04 May, 2020

This case study explains the symptoms, causes, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

This article uses a case study to discuss the symptoms, causes and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, describing the patient’s associated pathophysiology. Diagnosis involves spirometry testing to measure the volume of air that can be exhaled; it is often performed after administering a short-acting beta-agonist. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease involves lifestyle interventions – vaccinations, smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation – pharmacological interventions and self-management.

Citation: Price D, Williams N (2020) Diagnosis and management of COPD: a case study. Nursing Times [online]; 116: 6, 36-38.

Authors: Debbie Price is lead practice nurse, Llandrindod Wells Medical Practice; Nikki Williams is associate professor of respiratory and sleep physiology, Swansea University.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here (if the PDF fails to fully download please try again using a different browser)

Introduction

The term chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is used to describe a number of conditions, including chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Although common, preventable and treatable, COPD was projected to become the third leading cause of death globally by 2020 (Lozano et al, 2012). In the UK in 2012, approximately 30,000 people died of COPD – 5.3% of the total number of deaths. By 2016, information published by the World Health Organization indicated that Lozano et al (2012)’s projection had already come true.

People with COPD experience persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that can be due to airway or alveolar abnormalities, caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases, commonly from tobacco smoking. The projected level of disease burden poses a major public-health challenge and primary care nurses can be pivotal in the early identification, assessment and management of COPD (Hooper et al, 2012).

Grace Parker (the patient’s name has been changed) attends a nurse-led COPD clinic for routine reviews. A widowed, 60-year-old, retired post office clerk, her main complaint is breathlessness after moderate exertion. She scored 3 on the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale (Fletcher et al, 1959), indicating she is unable to walk more than 100 yards without stopping due to breathlessness. Ms Parker also has a cough that produces yellow sputum (particularly in the mornings) and an intermittent wheeze. Her symptoms have worsened over the last six months. She feels anxious leaving the house alone because of her breathlessness and reduced exercise tolerance, and scored 26 on the COPD Assessment Test (CAT, catestonline.org), indicating a high level of impact.

Ms Parker smokes 10 cigarettes a day and has a pack-year score of 29. She has not experienced any haemoptysis (coughing up blood) or chest pain, and her weight is stable; a body mass index of 40kg/m 2 means she is classified as obese. She has had three exacerbations of COPD in the previous 12 months, each managed in the community with antibiotics, steroids and salbutamol.

Ms Parker was diagnosed with COPD five years ago. Using Epstein et al’s (2008) guidelines, a nurse took a history from her, which provided 80% of the information needed for a COPD diagnosis; it was then confirmed following spirometry testing as per National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) guidance.

The nurse used the Calgary-Cambridge consultation model, as it combines the pathological description of COPD with the patient’s subjective experience of the illness (Silverman et al, 2013). Effective communication skills are essential in building a trusting therapeutic relationship, as the quality of the relationship between Ms Parker and the nurse will have a direct impact on the effectiveness of clinical outcomes (Fawcett and Rhynas, 2012).

In a national clinical audit report, Baxter et al (2016) identified inaccurate history taking and inadequately performed spirometry as important factors in the inaccurate diagnosis of COPD on general practice COPD registers; only 52.1% of patients included in the report had received quality-assured spirometry.

Pathophysiology of COPD

Knowing the pathophysiology of COPD allowed the nurse to recognise and understand the physical symptoms and provide effective care (Mitchell, 2015). Continued exposure to tobacco smoke is the likely cause of the damage to Ms Parker’s small airways, causing her cough and increased sputum production. She could also have chronic inflammation, resulting in airway smooth-muscle contraction, sluggish ciliary movement, hypertrophy and hyperplasia of mucus-secreting goblet cells, as well as release of inflammatory mediators (Mitchell, 2015).

Ms Parker may also have emphysema, which leads to damaged parenchyma (alveoli and structures involved in gas exchange) and loss of alveolar attachments (elastic connective fibres). This causes gas trapping, dynamic hyperinflation, decreased expiratory flow rates and airway collapse, particularly during expiration (Kaufman, 2013). Ms Parker also displayed pursed-lip breathing; this is a technique used to lengthen the expiratory time and improve gaseous exchange, and is a sign of dynamic hyperinflation (Douglas et al, 2013).

In a healthy lung, the destruction and repair of alveolar tissue depends on proteases and antiproteases, mainly released by neutrophils and macrophages. Inhaling cigarette smoke disrupts the usually delicately balanced activity of these enzymes, resulting in the parenchymal damage and small airways (with a lumen of <2mm in diameter) airways disease that is characteristic of emphysema. The severity of parenchymal damage or small airways disease varies, with no pattern related to disease progression (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, 2018).

Ms Parker also had a wheeze, heard through a stethoscope as a continuous whistling sound, which arises from turbulent airflow through constricted airway smooth muscle, a process noted by Mitchell (2015). The wheeze, her 29 pack-year score, exertional breathlessness, cough, sputum production and tiredness, and the findings from her physical examination, were consistent with a diagnosis of COPD (GOLD, 2018; NICE, 2018).

Spirometry is a tool used to identify airflow obstruction but does not identify the cause. Commonly measured parameters are:

- Forced expiratory volume – the volume of air that can be exhaled – in one second (FEV1), starting from a maximal inspiration (in litres);

- Forced vital capacity (FVC) – the total volume of air that can be forcibly exhaled – at timed intervals, starting from a maximal inspiration (in litres).

Calculating the FEV1 as a percentage of the FVC gives the forced expiratory ratio (FEV1/FVC). This provides an index of airflow obstruction; the lower the ratio, the greater the degree of obstruction. In the absence of respiratory disease, FEV1 should be ≥70% of FVC. An FEV1/FVC of <70% is commonly used to denote airflow obstruction (Moore, 2012).

As they are time dependent, FEV1 and FEV1/FVC are reduced in diseases that cause airways to narrow and expiration to slow. FVC, however, is not time dependent: with enough expiratory time, a person can usually exhale to their full FVC. Lung function parameters vary depending on age, height, gender and ethnicity, so the degree of FEV1 and FVC impairment is calculated by comparing a person’s recorded values with predicted values. A recorded value of >80% of the predicted value has been considered ‘normal’ for spirometry parameters but the lower limit of normal – equal to the fifth percentile of a healthy, non-smoking population – based on more robust statistical models is increasingly being used (Cooper et al, 2017).

A reversibility test involves performing spirometry before and after administering a short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) such as salbutamol; the test is used to distinguish between reversible and fixed airflow obstruction. For symptomatic asthma, airflow obstruction due to airway smooth-muscle contraction is reversible: administering a SABA results in smooth-muscle relaxation and improved airflow (Lumb, 2016). However, COPD is associated with fixed airflow obstruction, resulting from neutrophil-driven inflammatory changes, excess mucus secretion and disrupted alveolar attachments, as opposed to airway smooth-muscle contraction.

Administering a SABA for COPD does not usually produce bronchodilation to the extent seen in someone with asthma: a person with asthma may demonstrate significant improvement in FEV1 (of >400ml) after having a SABA, but this may not change in someone with COPD (NICE, 2018). However, a negative response does not rule out therapeutic benefit from long-term SABA use (Marín et al, 2014).

NICE (2018) and GOLD (2018) guidelines advocate performing spirometry after administering a bronchodilator to diagnose COPD. Both suggest a FEV1/FVC of <70% in a person with respiratory symptoms supports a diagnosis of COPD, and both grade the severity of the condition using the predicted FEV1. Ms Parker’s spirometry results showed an FEV1/FVC of 56% and a predicted FEV1 of 57%, with no significant improvement in these values with a reversibility test.

GOLD (2018) guidance is widely accepted and used internationally. However, it was developed by medical practitioners with a medicalised approach, so there is potential for a bias towards pharmacological management of COPD. NICE (2018) guidance may be more useful for practice nurses, as it was developed by a multidisciplinary team using evidence from systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials, providing a holistic approach. NICE guidance may be outdated on publication, but regular reviews are performed and published online.

NHS England (2016) holds a national register of all health professionals certified in spirometry. It was set up to raise spirometry standards across the country.

Assessment and management

The goals of assessing and managing Ms Parker’s COPD are to:

- Review and determine the level of airflow obstruction;

- Assess the disease’s impact on her life;

- Risk assess future disease progression and exacerbations;

- Recommend pharmacological and therapeutic management.

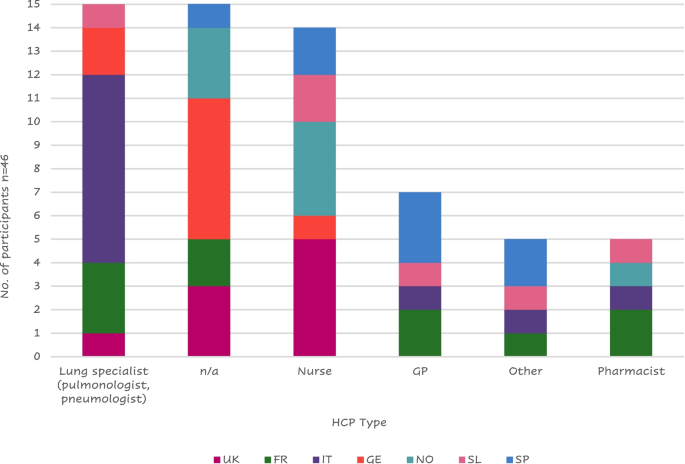

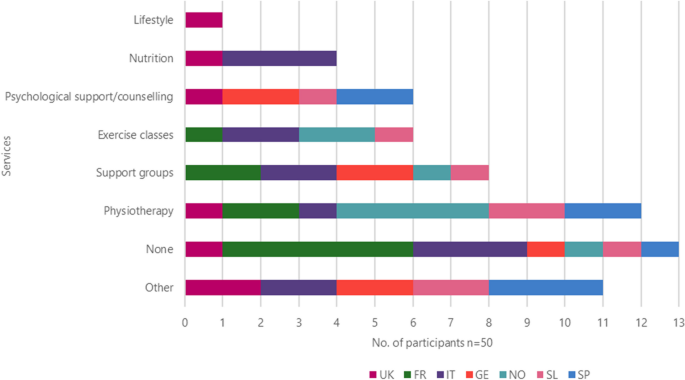

GOLD’s (2018) ABCD assessment tool (Fig 1) grades COPD severity using spirometry results, number of exacerbations, CAT score and mMRC score, and can be used to support evidence-based pharmacological management of COPD.

When Ms Parker was diagnosed, her predicted FEV1 of 57% categorised her as GOLD grade 2, and her mMRC score, CAT score and exacerbation history placed her in group D. The mMRC scale only measures breathlessness, but the CAT also assesses the impact COPD has on her life, meaning consecutive CAT scores can be compared, providing valuable information for follow-up and management (Zhao, et al, 2014).

After assessing the level of disease burden, Ms Parker was then provided with education for self-management and lifestyle interventions.

Lifestyle interventions

Smoking cessation.

Cessation of smoking alongside support and pharmacotherapy is the second-most cost-effective intervention for COPD, when compared with most other pharmacological interventions (BTS and PCRS UK, 2012). Smoking cessation:

- Slows the progression of COPD;

- Improves lung function;

- Improves survival rates;

- Reduces the risk of lung cancer;

- Reduces the risk of coronary heart disease risk (Qureshi et al, 2014).

Ms Parker accepted a referral to an All Wales Smoking Cessation Service adviser based at her GP surgery. The adviser used the internationally accepted ‘five As’ approach:

- Ask – record the number of cigarettes the individual smokes per day or week, and the year they started smoking;

- Advise – urge them to quit. Advice should be clear and personalised;

- Assess – determine their willingness and confidence to attempt to quit. Note the state of change;

- Assist – help them to quit. Provide behavioural support and recommend or prescribe pharmacological aids. If they are not ready to quit, promote motivation for a future attempt;

- Arrange – book a follow-up appointment within one week or, if appropriate, refer them to a specialist cessation service for intensive support. Document the intervention.

NICE (2013) guidance recommends that this be used at every opportunity. Stead et al (2016) suggested that a combination of counselling and pharmacotherapy have proven to be the most effective strategy.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Ms Parker’s positive response to smoking cessation provided an ideal opportunity to offer her pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) – as indicated by Johnson et al (2014), changing one behaviour significantly increases a person’s chance of changing another.

PR – a supervised programme including exercise training, health education and breathing techniques – is an evidence-based, comprehensive, multidisciplinary intervention that:

- Improves exercise tolerance;

- Reduces dyspnoea;

- Promotes weight loss (Bolton et al, 2013).

These improvements often lead to an improved quality of life (Sciriha et al, 2015).

Most relevant for Ms Parker, PR has been shown to reduce anxiety and depression, which are linked to an increased risk of exacerbations and poorer health status (Miller and Davenport, 2015). People most at risk of future exacerbations are those who already experience them (Agusti et al, 2010), as in Ms Parker’s case. Patients who have frequent exacerbations have a lower quality of life, quicker progression of disease, reduced mobility and more-rapid decline in lung function than those who do not (Donaldson et al, 2002).

“COPD is a major public-health challenge; nurses can be pivotal in early identification, assessment and management”

Pharmacological interventions

Ms Parker has been prescribed inhaled salbutamol as required; this is a SABA that mediates the increase of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in airway smooth-muscle cells, leading to muscle relaxation and bronchodilation. SABAs facilitate lung emptying by dilatating the small airways, reversing dynamic hyperinflation of the lungs (Thomas et al, 2013). Ms Parker also uses a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) inhaler, which works by blocking the bronchoconstrictor effects of acetylcholine on M3 muscarinic receptors in airway smooth muscle; release of acetylcholine by the parasympathetic nerves in the airways results in increased airway tone with reduced diameter.

At a routine review, Ms Parker admitted to only using the SABA and LAMA inhalers, despite also being prescribed a combined inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta 2 -agonist (ICS/LABA) inhaler. She was unaware that ICS/LABA inhalers are preferred over SABA inhalers, as they:

- Last for 12 hours;

- Improve the symptoms of breathlessness;

- Increase exercise tolerance;

- Can reduce the frequency of exacerbations (Agusti et al, 2010).

However, moderate-quality evidence shows that ICS/LABA combinations, particularly fluticasone, cause an increased risk of pneumonia (Suissa et al, 2013; Nannini et al, 2007). Inhaler choice should, therefore, be individualised, based on symptoms, delivery technique, patient education and compliance.

It is essential to teach and assess inhaler technique at every review (NICE, 2011). Ms Parker uses both a metered-dose inhaler and a dry-powder inhaler; an in-check device is used to assess her inspiratory effort, as different inhaler types require different inhalation speeds. Braido et al (2016) estimated that 50% of patients have poor inhaler technique, which may be due to health professionals lacking the confidence and capability to teach and assess their use.

Patients may also not have the dexterity, capacity to learn or vision required to use the inhaler. Online resources are available from, for example, RightBreathe (rightbreathe.com), British Lung Foundation (blf.org.uk). Ms Parker’s adherence could be improved through once-daily inhalers, as indicated by results from a study by Lipson et al (2017). Any change in her inhaler would be monitored as per local policy.

Vaccinations

Ms Parker keeps up to date with her seasonal influenza and pneumococcus vaccinations. This is in line with the low-cost, highest-benefit strategy identified by the British Thoracic Society and Primary Care Respiratory Society UK’s (2012) study, which was conducted to inform interventions for patients with COPD and their relative quality-adjusted life years. Influenza vaccinations have been shown to decrease the risk of lower respiratory tract infections and concurrent COPD exacerbations (Walters et al, 2017; Department of Health, 2011; Poole et al, 2006).

Self-management

Ms Parker was given a self-management plan that included:

- Information on how to monitor her symptoms;

- A rescue pack of antibiotics, steroids and salbutamol;

- A traffic-light system demonstrating when, and how, to commence treatment or seek medical help.

Self-management plans and rescue packs have been shown to reduce symptoms of an exacerbation (Baxter et al, 2016), allowing patients to be cared for in the community rather than in a hospital setting and increasing patient satisfaction (Fletcher and Dahl, 2013).

Improving Ms Parker’s adherence to once-daily inhalers and supporting her to self-manage and make the necessary lifestyle changes, should improve her symptoms and result in fewer exacerbations.

The earlier a diagnosis of COPD is made, the greater the chances of reducing lung damage through interventions such as smoking cessation, lifestyle modifications and treatment, if required (Price et al, 2011).

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a progressive respiratory condition, projected to become the third leading cause of death globally

- Diagnosis involves taking a patient history and performing spirometry testing

- Spirometry identifies airflow obstruction by measuring the volume of air that can be exhaled

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is managed with lifestyle and pharmacological interventions, as well as self-management

Related files

200506 diagnosis and management of copd – a case study.

- Add to Bookmarks

Related articles

Have your say.

Sign in or Register a new account to join the discussion.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2: Case Study #1- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 9896

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

- 2.1: Learning Objectives

- 2.2: Patient- Erin Johns

- 2.3: At Home

- 2.4: Emergency Room

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 07 May 2015

Four patients with a history of acute exacerbations of COPD: implementing the CHEST/Canadian Thoracic Society guidelines for preventing exacerbations

- Ioanna Tsiligianni 1 , 2 ,

- Donna Goodridge 3 ,

- Darcy Marciniuk 4 ,

- Sally Hull 5 &

- Jean Bourbeau 6

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine volume 25 , Article number: 15023 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

59k Accesses

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Respiratory tract diseases

The American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society have jointly produced evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This educational article gives four perspectives on how these guidelines apply to the practical management of people with COPD. A current smoker with frequent exacerbations will benefit from support to quit, and from optimisation of his inhaled treatment. For a man with very severe COPD and multiple co-morbidities living in a remote community, tele-health care may enable provision of multidisciplinary care. A woman who is admitted for the third time in a year needs a structured assessment of her care with a view to stepping up pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment as required. The overlap between asthma and COPD challenges both diagnostic and management strategies for a lady smoker with a history of asthma since childhood. Common threads in all these cases are the importance of advising on smoking cessation, offering (and encouraging people to attend) pulmonary rehabilitation, and the importance of self-management, including an action plan supported by multidisciplinary teams.

Similar content being viewed by others

Diagnostic spirometry in COPD is increasing, a comparison of two Swedish cohorts

COPD overdiagnosis in primary care: a UK observational study of consistency of airflow obstruction

Phenotype and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in general population in China: a nationally cross-sectional study

Case study 1: a 63-year-old man with moderate/severe copd and a chest infection.

A 63-year-old self-employed plumber makes a same-day appointment for another ‘chest infection’. He caught an upper respiratory tract infection from his grandchildren 10 days ago, and he now has a productive cough with green sputum, and his breathlessness and fatigue has forced him to take time off work.

He has visited his general practitioner with similar symptoms two or three times every year in the last decade. A diagnosis of COPD was confirmed 6 years ago, and he was started on a short-acting β 2 -agonist. This helped with his day-to-day symptoms, although recently the symptoms of breathlessness have been interfering with his work and he has to pace himself to get through the day. Recovering from exacerbations takes longer than it used to—it is often 2 weeks before he is able to get back to work—and he feels bad about letting down customers. He cannot afford to retire, but is thinking about reducing his workload.

He last attended a COPD review 6 months ago when his FEV 1 was 52% predicted. He was advised to stop smoking and given a prescription for varenicline, but he relapsed after a few days and did not return for the follow-up appointment. He attends each year for his ‘flu vaccination’. His only other medication is an ACE inhibitor for hypertension.

Managing the presenting problem. Is it a COPD exacerbation?

A COPD exacerbation is defined as ‘an acute event characterised by a worsening of the patient’s respiratory symptoms that is beyond normal day-to-day variation and leads to change in medications’. 1 , 2 The worsening symptoms are usually increased dyspnoea, increased sputum volume and increased sputum purulence. 1 , 2 All these symptoms are present in our patient who experiences an exacerbation triggered by a viral upper respiratory tract infection—the most common cause of COPD exacerbations. Apart from the management of the acute exacerbation that could include antibiotics, oral steroids and increased use of short-acting bronchodilators, special attention should be given to his on-going treatment to prevent future exacerbations. 2 Short-term use of systemic corticosteroids and a course of antibiotics can shorten recovery time, improve lung function (forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV 1 )) and arterial hypoxaemia and reduce the risk of early relapse, treatment failure and length of hospital stay. 1 , 2 Short-acting inhaled β 2 -agonists with or without short-acting anti-muscarinics are usually the preferred bronchodilators for the treatment of an acute exacerbation. 1

Reviewing his routine treatment

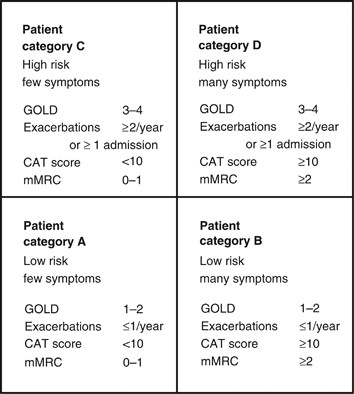

One of the concerns about this patient is that his COPD is inadequately treated. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) suggests that COPD management be based on a combined assessment of symptoms, GOLD classification of airflow limitation, and exacerbation rate. 1 The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea score 3 or the COPD Assessment Tool (CAT) 4 could be used to evaluate the symptoms/health status. History suggests that his breathlessness has begun to interfere with his lifestyle, but this has not been formally asssessed since the diagnosis 6 years ago. Therefore, one would like to be certain that these elements are taken into consideration in future management by involving other members of the health care team. The fact that he had two to three exacerbations per year puts the patient into GOLD category C–D (see Figure 1 ) despite the moderate airflow limitation. 1 , 5 Our patient is only being treated with short-acting bronchodilators; however, this is only appropriate for patients who belong to category A. Treatment options for patients in category C or D should include long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) or long-acting β 2 -agonists (LABAs), which will not only improve his symptoms but also help prevent future exacerbations. 2 Used in combination with LABA or LAMA, inhaled corticosteroids also contribute to preventing exacerbations. 2

The four categories of COPD based on assessment of symptoms and future risk of exacerbations (adapted by Gruffydd-Jones, 5 from the Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD). 1 CAT, COPD Assessment Tool; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council Dyspnoea Scale.

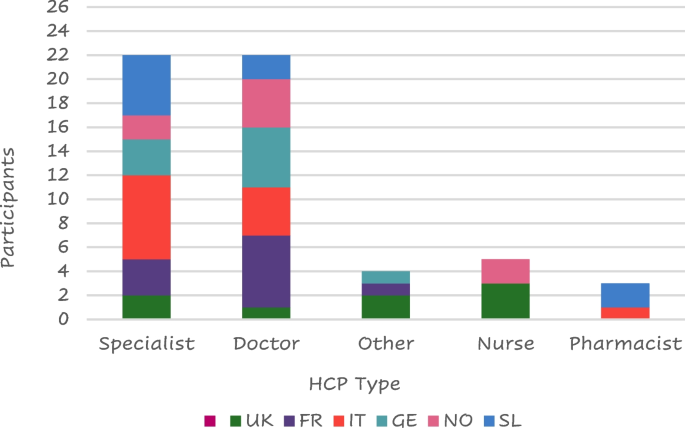

Prevention of future exacerbations

Exacerbations should be prevented as they have a negative impact on the quality of life; they adversely affect symptoms and lung function, increase economic cost, increase mortality and accelerate lung function decline. 1 , 2 Figure 2 summarises the recommendations and suggestions of the joint American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society (CHEST/CTS) Guidelines for the prevention of exacerbations in COPD. 2 The grades of recommendation from the CHEST/CTS guidelines are explained in Table 1 .

Decision tree for prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD (reproduced with permission from the CHEST/CTS Guidelines for the prevention of exacerbations in COPD). 2 This decision tree for prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD is arranged according to three key clinical questions using the PICO format: non-pharmacologic therapies, inhaled therapies and oral therapies. The wording used is ‘Recommended or Not recommended’ when the evidence was strong (Level 1) or ‘Suggested or Not suggested’ when the evidence was weak (Level 2). CHEST/CTS, American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV 1 , forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist; SABA, short-acting β-agonist; SM, self-management.

Pharmacological approach

In patients with moderate-to-severe COPD, the use of LABA or LAMA compared with placebo or short-acting bronchodilators is recommended to prevent acute exacerbations (Grades 1B and 1A, respectively). 2 , 6 , 7 LAMAs are associated with a lower rate of exacerbations compared with LABAs (Grade 1C). 2 , 6 The inhaler technique needs to be checked and a suitable device selected. If our patient does not respond to optimizing inhaled medication and continues to have two to three exacerbations per year, there are additional options that offer pulmonary rehabilitation and other forms of pharmacological therapy, such as a macrolide, theophylline, phosphodieseterase (PDE4) inhibitor or N -acetylocysteine/carbocysteine, 2 although there is no information about their relative effectiveness and the order in which they should be prescribed. The choice of prescription should be guided by the risk/benefit for a given individual, and drug availability and/or cost within the health care system.

Non-pharmacological approach

A comprehensive patient-centred approach based on the chronic care model could be of great value. 2 , 8

This should include the following elements

Vaccinations: the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine and annual influenza vaccine are suggested as part of the overall medical management in patients with COPD. 2 Although there is no clear COPD-specific evidence for the pneumococcal vaccine and the evidence is modest for influenza, the CHEST/CTS Guidelines concur with advice of the World Health Organization (WHO) 9 and national advisory bodies, 10 – 12 and supports their use in COPD patients who are at risk for serious infections. 2

Smoking cessation (including counselling and treatment) has low evidence for preventing exacerbations (Grade 2C). 2 However, the benefits from smoking cessation are outstanding as it improves COPD prognosis, slows lung function decline and improves the quality of life and symptoms. 1 , 2 , 13 , 14 Our patient has struggled to quit in the past; assessing current readiness to quit, and encouraging and supporting a future attempt is a priority in his care.

Pulmonary rehabilitation (based on exercise training, education and behaviour change) in people with moderate-to-very-severe COPD, provided within 4 weeks of an exacerbation, can prevent acute exacerbations (Grade 1C). 2 Pulmonary rehabilitation is also an effective strategy to improve symptoms, the quality of life and exercise tolerance, 15 , 16 and our patient should be encouraged to attend a course.

Self-management education with a written action plan and supported by case management providing regular direct access to a health care specialist reduces hospitalisations and prevents severe acute exacerbations (Grade 2C). 2 Some patients with good professional support can have an emergency course of steroids and antibiotics to start at the onset of an exacerbation in accordance with their plan.

Finally, close follow-up is needed for our patient as he was inadequately treated, relapsed from smoking cessation after a few days despite varenicline, and missed his follow-up appointment. A more alert health care team may have been able to identify these issues, avoid his relapse and take a timely approach to introducing additional measures to prevent his recurrent acute exacerbations.

Case study 2: A 74-year-old man with very severe COPD living alone in a remote community

A 74-year-old man has a routine telephone consultation with the respiratory team. He has very severe COPD (his FEV 1 2 years ago was 24% of predicted) and he copes with the help of his daughter who lives in the same remote community. He quit smoking the previous year after an admission to the hospital 50 miles away, which he found very stressful. He and his family managed another four exacerbations at home with courses of steroids and antibiotics, which he commenced in accordance with a self-management plan provided by the respiratory team.

His usual therapy consists of regular long-acting β 2 -agonist/inhaled steroid combination and a long-acting anti-muscarinic. He has a number of other health problems, including coronary heart disease and osteoarthritis and, in recent times, his daughter has become concerned that he is becoming forgetful. He manages at home by himself, steadfastly refusing social help and adamant that he does not want to move from the home he has lived in for 55 years.

This is a common clinical scenario, and a number of important issues require attention, with a view to optimising the management of this 74-year-old man suffering from COPD. He has very severe obstruction, is experiencing frequent acute flare-ups, is dependent and isolated and has a number of co-morbidities. To work towards preventing future exacerbations in this patient, a comprehensive plan addressing key medical and self-care issues needs to be developed that accounts for his particular context.

Optimising medical management

According to the CHEST/CTS Guidelines for prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD, 2 this patient should receive an annual influenza vaccination and may benefit from a 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine (Grades 1B and 2C, respectively). Influenza infection is associated with greater risk of mortality in COPD, as well as increased risk of hospitalisation and disease progression. 1 A diagnosis of COPD also increases the risk for pneumococcal disease and related complications, with hospitalisation rates for patients with COPD being higher than that in the general population. 10 , 17 Although existing evidence does not support the use of this vaccine specifically to prevent exacerbations of COPD, 1 administration of the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine is recommended as a component of overall medical management. 9 – 12

Long-term oxygen therapy has been demonstrated to improve survival in people with chronic hypoxaemia; 18 it would be helpful to obtain oxygen saturation levels and consider whether long-term oxygen therapy would be of benefit to this patient.

Even though this patient is on effective medications, further optimisation of pharmacologic therapy should be undertaken, including reviewing administration technique for the different inhaler devices. 19 Maintenance PDE4 inhibitors, such as roflumilast or theophyllines, long-term macrolides (i.e., azithromycin) or oral N -acetylcysteine are potential considerations. Each of these therapeutic options has demonstrated efficacy in preventing future acute exacerbations, although they should be used with caution in this frail elderly man. 2 This patient would benefit from a review of co-morbidities, including a chest X-ray, electrocardiogram, memory assessment and blood tests including haemoglobin, glucose, thyroid and renal function assessments.

Pulmonary rehabilitation, supported self-management and tele-health care

Pulmonary rehabilitation for patients who have recently experienced an exacerbation of COPD (initiated <4 weeks following the exacerbation) has been demonstrated to prevent subsequent exacerbations (Grade 1C). 2 Existing evidence suggests that pulmonary rehabilitation does not reduce future exacerbations when the index exacerbation has occurred more than 4 weeks earlier; 2 however, its usefulness is evident in other important patient-centred outcomes such as improved activity, walking distance and quality of life, as well as by reduced shortness of breath. It would be appropriate to discuss this and enable our patient to enrol in pulmonary rehabilitation.

The patient’s access to pulmonary rehabilitation in his remote location, however, is likely to be limited. Several reports have noted that only one to two percent of people with COPD are able to access pulmonary rehabilitation programmes within Canada, 20 the United States 21 and the United Kingdom. 22 Alternatives to hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation programmes, such as home-based programmes or programmes offered via tele-health, may be options for this patient. 23 Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation programmes have been found to improve exercise tolerance, symptom burden and quality of life. 24 – 27 Outcomes of a pulmonary rehabilitation programme offered via tele-health have also been found to be comparable to those of a hospital-based programme, 28 and may be worth exploring.

Written self-management (action) plans, together with education and case management, are suggested in the CHEST/CTS guidelines as a strategy to reduce hospitalisation and emergency department visits attributable to exacerbations of COPD (Grade 2B). 2 Our patient has an existing action plan, which has enabled him and his family to manage some exacerbations at home. Although the patient has likely had some education on COPD and its management in the past, on-going reinforcement of key principles may be helpful in preventing future exacerbations.

The self-management plan should be reviewed regularly to ensure the advice remains current. The patient’s ability to use the self-management plan safely also needs to be assessed, given his daughter’s recent observation of forgetfulness and his living alone. Cognitive impairment is being increasingly recognised as a significant co-morbidity of COPD. 29 , 30 Patients who were awaiting discharge from hospital following an exacerbation of COPD were found to perform significantly worse on a range of cognitive functional measures than a matched group with stable COPD, a finding that persisted 3 months later. 29 Cognitive impairment may contribute independently to the risk for future exacerbations by increasing the likelihood of incorrect inhaler device use and failure to adhere to recommended treatments. 29

Given that this patient resides in a remote location, access to case management services that assist in preventing future exacerbations may be difficult or impossible to arrange. Although there is currently insufficient evidence that in general the use of telemonitoring contributes to the prevention of exacerbations of COPD, 2 tele-health care for this remotely located patient has potential to allow for case management at a distance, with minimal risk to the patient. Further study is needed to address this potential benefit.

Assessing for and managing frailty

Recognising this patient’s co-morbid diagnoses of coronary heart disease and osteoarthritis, careful assessment of functional and self-care abilities would be appropriate. Almost 60% of older adults with COPD meet the criteria for frailty. 31 Frailty is defined as a dynamic state associated with decline of physiologic reserves in multiple systems and inability to respond to stressful insults. 32 Frailty is associated with an increased risk for institutionalisation and mortality. 33 , 34 Given the complex needs of those who are frail, screening this patient for frailty would constitute patient-centred and cost-effective care. Frailty assessment tools, such as the seven-point Clinical Frailty Index, 35 may provide structure to this assessment.

Admission to a hospital 50 miles away from our patient’s home last year for an exacerbation was stressful. Since his hospitalisation, this patient has experienced four additional exacerbations that have been managed at home in his remote community. It would be appropriate to explore the patient’s treatment wishes and determine whether the patient has chosen to refuse further hospitalisations. Our patient’s risk of dying is significant, with risk factors increasing the risk of short-term mortality following an exacerbation of COPD (GOLD Stage 4, age, male sex, confusion). 36 Mortality rates between 22 and 36% have been documented in the first and second years, respectively, following an exacerbation, 37 , 38 which also increase with the frequency and severity of hospitalisations. 39

Our patient has refused social help and does not want to be relocated from his home. Ageing in their own home is a key goal of many older adults. 40 , 41 Efforts to ensure that adequate resources to support the patient are available (and to support the daughter who is currently providing a lot of his care) will form an important part of the plan of care.

Case study 3: A 62-year-old woman with severe COPD admitted with an exacerbation

A 62-year-old lady is admitted for the third time this year with an acute exacerbation of her severe COPD. Her FEV 1 was 35% predicted at the recent outpatient visit. She retired from her job as a shop assistant 5 years ago because of her breathlessness and now devotes her time to her grandchildren who ‘exhaust her’ but give her a lot of pleasure.

She quit smoking 5 years ago. Over the years, her medication has increased, as nothing seemed to relieve her uncomfortable breathlessness, and, in addition to inhaled long-acting β 2 -agonist/ inhaled steroid combination and a long-acting anti-muscarinic, she is taking theophylline and carbocysteine, although she is not convinced of their beneficial effect. Oral steroid courses help her dyspnoea and she has taken at least six courses this year: she has an action plan and keeps an emergency supply of medication at home.

A secondary care perspective on the management strategy for this woman

Acute exacerbations of COPD have serious negative consequences for health care systems and patients. The risk of future events and complications, such as hospital admission and poor patient outcomes (disability and reduced health status), can be improved through a combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapies. 2

Evaluation of the patient, risk assessment and adherence to medication

The essential first step in the management of this lady (as for any patient) includes a detailed medical evaluation. Our patient has a well-established diagnosis of COPD with severe airflow obstruction (GOLD grade 3), significant breathlessness that resulted in her retiring from her job, and recurrent exacerbations. She does not have significant co-morbidity, although this requires to be confirmed. Further to the medical evaluation, it is important to assess her actual disease management (medication and proper use) as well as making sure she has adopted a healthy lifestyle (smoking cessation, physical activities and exercise). Does she live in a smoke-free environment? Effect of and evidence for smoking cessation in the prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD is low, but evidence exists for a reduction in cough and phlegm after smoking cessation and less lung function decline upon sustained cessation. With respect to the medication, never assume that it is taken as prescribed. When asking the patient, use open questions such as ‘I would like to hear how you take your medication on a typical day?’ instead of ‘Did you take the medication as prescribed’. Open questions tend to elicit more useful and pertinent information, and invite collaboration. Asking the patient to demonstrate her inhalation technique shows you the way she uses her different inhalation devices.

Optimising the pharmacological therapy

The second step is to assess whether the patient is on optimal treatment to prevent exacerbations. In other words, can we do better helping the patient manage her disease and improving her well-being. As in the previous cases, vaccination, in particular, annual administration of the influenza vaccine, should be prescribed for this lady. We should evaluate other alternatives of pharmacological therapy that could improve symptoms, prevent exacerbations and reduce the use of repeated systemic corticosteroids with their important adverse effects (such as osteoporosis, cataracts, diabetes). Prescribing a PDE4 inhibitor (Grade 2A) or a long-term macrolide (Grade 2A) once a day would be a consideration for this lady. 2 As there is no superiority trial comparing these two medications, our preference will be based on potential side effects, as well as cost and access to treatment. For PDE4 inhibitors, there are limited data on supplemental effectiveness in patients with COPD and chronic bronchitis concurrently using inhaled therapies, and they potentially have side effects such as diarrhoea, nausea, headache and weight loss. The side effects tend to diminish over time, but some patients may have to discontinue the therapy. Long-term macrolides have been studied in COPD patients already treated with inhaled therapies and shown to be effective, although clinicians need to consider in their individual patients the potential for harm, such as prolongation of the QT interval, hearing loss and bacterial resistance. Furthermore, the duration (beyond 1 year) and exact dosage of macrolide therapy (for example, once daily versus three times per week) are unknown.

Making non-pharmacological therapy an essential part of the management

The third step, often neglected in the management of COPD patients, is non-pharmacological therapy. For this lady, we suggest self-management education with a written action plan and case management to improve how she deals with exacerbations (Grade 2B). 2 The expectation will not be to reduce exacerbations but to prevent emergency department visits and hospital admissions. However, despite general evidence of efficacy, 42 not all self-management interventions have been shown to be effective or to benefit all COPD patients 43 , 44 (some have been shown to be potentially harmful 44 ). The effectiveness of any complex intervention such as self-management in COPD critically depends on the health care professionals who deliver the intervention, as well on the patient and the health care system. The patient may not have the motivation or desire to change or to commit to an intensive programme. The individual patient’s needs, preferences and personal goals should inform the design of any intervention with a behavioural component. For this lady, it is essential to apply integrated disease management and to refer the patient to a pulmonary rehabilitation programme. Pulmonary rehabilitation has high value, including reducing the risk for hospitalisation in COPD patients with recent exacerbations (Grade 1C). 2 The most important benefits our patient can expect from participating in structured supervised exercise within pulmonary rehabilitation are improved health status, exercise tolerance and a reduction in dyspnoea (Grade 1A). 2 , 15 Pulmonary rehabilitation programmes provide clinicians with an opportunity to deliver education and self-management skills to patients with COPD, and are well established as a means of enhancing standard therapy to control and alleviate symptoms, optimise functional capacity and improve health-related quality of life.

Case study 4: A 52-year-old lady with moderate COPD—and possibly asthma

A 52-year-old lady attends to discuss her COPD and specifically the problem she is having with exacerbations and time ‘off sick’. She is a heavy smoker, and her progressively deteriorating lung function suggests that she has moderate COPD, although she also has a history of childhood asthma, and had allergic rhinitis as a teenager. Recent spirometry showed a typical COPD flow-volume loop, although she had some reversibility (250 ml and 20%) with a post-bronchodilator FEV 1 of 60% predicted.

She has a sedentary office job and, although she is breathless on exertion, this generally does not interfere with her lifestyle. The relatively frequent exacerbations are more troublesome. They are usually triggered by an upper respiratory infection and can take a couple of weeks to recover. She has had three exacerbations this winter, and as a result her employer is not happy with her sickness absence record and has asked her to seek advice from her general practitioner.

She has a short-acting β 2 -agonist, although she rarely uses it except during exacerbations. In the past, she has used an inhaled steroid, but stopped that some time ago as she was not convinced it was helping.

It is a welcome opportunity when a patient comes to discuss her COPD with a particular issue to address. With a history of childhood asthma, and serial COPD lung function tests, she has probably been offered many components of good primary care for COPD, but has not yet fully engaged with her management. We know that ~40% of people with COPD continue to smoke, and many are intermittent users of inhaled medications. 45 It is easy to ignore breathlessness when both job and lifestyle are sedentary.

Understanding her diagnosis and setting goals

Her readiness to engage can be supported by a move to structured collaborative care, enabling the patient to have the knowledge, resources and support to make the necessary changes. Much of this can be done by the primary care COPD team, including the pharmacist. Regular recall to maintain engagement is essential.

The combination of childhood asthma, rhinitis and a long history of smoking requires diagnostic review. This might include serial peak flows over 2 weeks to look for variability, and a chest X-ray, if not done recently, to rule out lung cancer as a reason for recent exacerbations. Her spirometry suggests moderate COPD, 1 , 46 but she also has some reversibility, not enough to place her in the asthma camp but, combined with her past medical history, being enough to explore an asthma COPD overlap syndrome. This is important to consider as it may guide decisions on inhaled medication, and there is evidence that lung function deteriorates faster in this group. 47 It is estimated that up to 20% of patients have overlap diagnoses, although the exact prevalence depends on the definition. 48

Reducing the frequency of exacerbations

Exacerbations in COPD are debilitating, often trigger hospital admission and hasten a progressive decline in pulmonary function. 2 Written information on interventions that can slow down the course of COPD and reduce the frequency and impact of exacerbations will help to support progressive changes in management.

Smoking cessation

Few people are unaware that cessation of smoking is the key intervention for COPD. Reducing further decline in lung function will slow down the severity of exacerbations. Finding a smoking cessation programme that suits her working life, exploring previous attempts at cessation, offering pharmacotherapy and a non-judgemental approach to further attempts at stopping are crucial.

Immunisations

Many, but not all, exacerbations of COPD are triggered by viral upper respiratory tract infections. Annual flu immunisation is a part of regular COPD care and reduces exacerbations and hospitalisation when flu is circulating (Grade 1B). Pneumococcal immunisation should be offered, although evidence for reducing exacerbations is weak; those with COPD will be at greater risk for pneumococcal infection. 2

Pulmonary rehabilitation

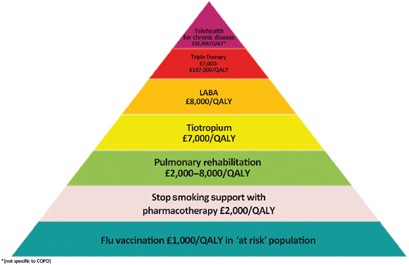

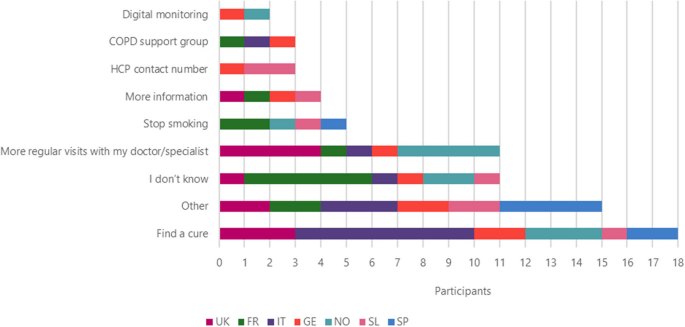

Pulmonary rehabilitation improves symptoms, quality of life and reduces hospital admission. 49 It is most efficacious in patients who are symptomatic (MRC dyspnoea scale 3 and above) and in terms of reducing exacerbations is most effective when delivered early after an exacerbation (Grade 1C). 2 The major hurdle is encouraging patients to attend, with most programmes showing an attrition rate of 30% before the first appointment, and high rates of non-completion. 45 , 50 Effective programmes that maintain the gains from aerobic exercise are more cost-effective than some of the inhaled medications in use (see Figure 3 ). 50

The COPD value pyramid (developed by the London Respiratory Network with The London School of Economics and reproduced with permission from the London Respiratory Team report 2013). 48 This 'value' pyramid reflects what we currently know about the cost per QALY of some of the commonest interventions in COPD. It was devised as a tool for health care organisations to use to promote audit and to ensure adequate commissioning of non-pharmacological interventions. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

Inhaled medication is likely to improve our patient’s breathlessness and contribute to a reduction in exacerbation frequency. Currently, she uses only a short-acting β 2 -agonist. One wonders if she has a spacer? How much of the medicine is reaching her lungs? Repeated observation and training in inhaler use is essential if patients are to benefit from expensive medications.

With her history of asthma and evidence of some reversibility, the best choice of regular medication may be a combination of inhaled corticosteroid and a LABA. Guidelines suggest the asthma component in asthma COPD overlap syndrome should be the initial treatment target, 48 and a LABA alone should be avoided. Warn about oral thrush, and the increased risk for pneumonia. 46 If she chooses not to use an inhaled steroid, then a trial of a LAMA is indicated. Both drugs reduce exacerbation rates. 2 , 51

Finally, ensuring early treatment of exacerbations speeds up recovery. 52 Prescribe rescue medication (a 5–7-day course of oral steroids and antibiotic) to be started when symptomatic, and encourage attendance at a post-exacerbation review.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Updated 2014. http://www.goldcopd.org. Accessed January 2015.

Criner GJ, Bourbeau J, Diekemper RL, Ouellette DR, Goodridge D, Hernandez P et al. Prevention of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline. Chest 2015; 147 : 894–942.

Article Google Scholar

Fletcher CM . Standardised questionnaire on respiratory symptoms: a statement prepared and approved by the MRC Committee on the Aetiology of Chronic Bronchitis (MRC breathlessness score). BMJ 1960; 2 : 1665.

Google Scholar

Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen W-H, Leidy NK . Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J 2009; 34 : 648–654.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Gruffydd-Jones K . GOLD guidelines 2011: what are the implications for primary care? Prim Care Respir J 2012; 21 : 437–441.

Chong J, Karner C, Poole P . Tiotropium versus long-acting beta-agonists for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 9 : CD009157.

Cheyne L, Irvin-Sellers MJ, White J . Tiotropium versus ipratropium bromide for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 9 : CD009552.

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K . Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 2002; 288 : 1775–1779.

World Health Organization. 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2008; 83 : 373–384.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention Pneumococcal vaccination. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/pneumo/ . Accessed January 2015.

Public Health England (2014a) Immunisation against infectious disease - "The Green Book". Chapter 19 - Influenza. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book . Accessed January 2015.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian immunization guide: Pneumococcal vaccine, 2014. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/cig-gci/p04-pneu-eng.php . Accessed January 2015.

Fletcher C, Peto R . The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. Br Med J 1977; 1 : 1645–1648.

Hersh CP, DeMeo DL, Al-Ansari E, Carey VJ, Reilly JJ, Ginns LC et al. Predictors of survival in severe, early onset COPD. Chest 2004; 126 : 1443–1451.

Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson TJ, Martin S . Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (4): CD003793.

Lacasse Y, Wong E, Guyatt GH, King D, Cook DJ, Goldstein RS . Meta-analysis of respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 1996; 348 : 1115–1119.

Lee T, Weaver F, Weiss K . Impact of pneumococcal vaccination on pneumonia rates in patients with COPD and asthma. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22 : 62–67.

Crockett AJ, Cranston JM, Moss JR, Allpers JH . A review of long-term oxygen therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2001; 95 : 437–443.

Newman SP . Inhaler treatment options in COPD. Eur Respir Rev 2005; 96 : 102–108.

Brooks D, Sottana R, Bell B, Hanna M, Laframboise L, Selvanayagarajah S et al. Characterization of pulmonary rehabilitation programs in Canada in 2005. Can Respir J 2007; 14 : 87–92.

Bickford LS, Hodgkin JE, McInturff SL . National pulmonary rehabilitation survey. Update. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 1995; 15 : 406–411.

Yohannes AM, Connolly MJ . Pulmonary rehabilitation programmes in the UK: a national representative survey. Clin Rehabil 2004; 18 : 444–449.

Marciniuk DD, Brooks D, Butcher S, Debigare R, Dechman G, Ford G et al. Optimizing pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – practical issues: a Canadian Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Can Respir J 2010; 17 : 159–168.

Guell M, De-Lucas P, Galdiz J, Montemayor T, Rodriguez Gonzalez-Moro J, Gorostiza A . Home vs hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: disease: a Spanish multicentre trial. Arch Bronconeumol 2008; 44 : 512–518.

Maltais F, Bourbeau J, Shapiro S, Lacasse Y, Perrault H, Baltzan M . Effects of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149 : 869–878.

Puente-Maestu L, Sanz M, Sanz P, Cubillo J, Mayol J, Casaburi R . Comparison of effects of supervised versus self-monitored training programmes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2000; 15 : 517–525.

Strijbos J, Postma D, Van-Altena R, Gimeno F, Koeter G . A comparison between an outpatient hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation program and a home-care pulmonary rehabilitation program in patients with COPD. A follow-up of 18 months. Chest 1996; 109 : 366–372.

Stickland M, Jourdain T, Wong EY, Rodgers WM, Jendzjowsky NG, MacDonald GF . Using Telehealth technology to deliver pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Can Respir J 2011; 18 : 216–220.

Dodd JW, Getov SV, Jones PW . Cognitive function in COPD. Eur Respir J 2010; 35 : 913–922.