- Open access

- Published: 14 October 2022

The effectiveness of case management for cancer patients: an umbrella review

- Nina Wang 1 , 2 ,

- Jia Chen 3 ,

- Wenjun Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5398-8508 4 , 5 ,

- Zhengkun Shi 1 ,

- Huaping Yang 1 ,

- Peng Liu 6 ,

- Xiao Wei 7 ,

- Xiangling Dong 6 ,

- Chen Wang 3 ,

- Ling Mao 8 &

- Xianhong Li 3

BMC Health Services Research volume 22 , Article number: 1247 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2473 Accesses

24 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Case management (CM) is widely utilized to improve health outcomes of cancer patients, enhance their experience of health care, and reduce the cost of care. While numbers of systematic reviews are available on the effectiveness of CM for cancer patients, they often arrive at discordant conclusions that may confuse or mislead the future case management development for cancer patients and relevant policy making. We aimed to summarize the existing systematic reviews on the effectiveness of CM in health-related outcomes and health care utilization outcomes for cancer patient care, and highlight the consistent and contradictory findings.

An umbrella review was conducted followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Umbrella Review methodology. We searched MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Scopus for reviews published up to July 8th, 2022. Quality of each review was appraised with the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses. A narrative synthesis was performed, the corrected covered area was calculated as a measure of overlap for the primary studies in each review. The results were reported followed the Preferred reporting items for overviews of systematic reviews checklist.

Eight systematic reviews were included. Average quality of the reviews was high. Overall, primary studies had a slight overlap across the eight reviews (corrected covered area = 4.5%). No universal tools were used to measure the effect of CM on each outcome. Summarized results revealed that CM were more likely to improve symptom management, cognitive function, hospital (re)admission, treatment received compliance, and provision of timely treatment for cancer patients. Overall equivocal effect was reported on cancer patients’ quality of life, self-efficacy, survivor status, and satisfaction. Rare significant effect was reported on cost and length of stay.

Conclusions

CM showed mixed effects in cancer patient care. Future research should use standard guidelines to clearly describe details of CM intervention and its implementation. More primary studies are needed using high-quality well-powered designs to provide solid evidence on the effectiveness of CM. Case managers should consider applying validated and reliable tools to evaluate effect of CM in multifaced outcomes of cancer patient care.

Peer Review reports

Cancer ranks as one of the leading causes of premature death among population around 30–69 years old across 134 countries [ 1 ], and the global incidence of cancer is about to reach 30.2 million new cases and 25.7 million deaths by 2040 [ 2 ]. Earlier detection and diagnosis, and development of diverse cancer treatments have increased the survival rate of cancer patients. According to Quaresma et al. [ 3 ], the cancer survival in the UK has doubled over the last 40 years alongside the advancement in cancer diagnosis and treatment. However, number of challenges exist in the current cancer care all over the world. Many cancer patients oftentimes receive a series of long-running and exhausting multi-modal treatments and experience descent in psychological, physical and social functioning, which have a significant negative impact on their quality of life (QoL) [ 4 , 5 ]. In addition, the significant healthcare spending and productivity losses of cancer patients lead to a heavy patient economic burden, which is another substantial issue with cancer care [ 6 ]. A systematic approach is needed to mobilize and deliver appropriate resources, provide accessible, safe, and well-coordinated care for cancer patients received stressful treatments and shouldered heavy economic burden [ 7 ].

Case management (CM) is defined by the Case Management Society of America (CMSA) as “a collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation, and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s and family’s comprehensive health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality, cost-effective outcomes” (P. 11) [ 8 ]. According to the definition, CM is designed to use resources effectively to improve the quality of treatments, patient care services, and QoL of patients while reducing the relevant healthcare costs.

With the worldwide utilization of CM in cancer patient care, studies examining the effect of CM in improving patient-related outcomes or healthcare service use outcomes have been skyrocketing. Numbers of systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published to synthesis the effectiveness of CM in recent years and often arrive at discordant conclusions. For example, Joo et al. [ 9 ] retrieved and synthesised results from nine experimental studies and found that CM effectively improved patients’ QoL and symptom management. While Aubin et al. [ 10 ] reported equivocal effect on both QoL and symptom management. Chan et al. [ 11 ] reported that four of the five randomized controlled trials showed insignificant impact of CM on patients’ QoL. The inconsistent evidence on the impact of CM may confuse or mislead the future case management development and relevant policy making. Considering the exist of several systematic reviews and research synthesis available to inform the application of case management for cancer patient care improvement, umbrella review could now be undertaken to compare and contrast published reviews and to highlight the consistent or contradictory findings around the effect of CM on manifold aspects of cancer patient care [ 12 ]. Thus, the current review was conducted to 1) synthesis systematic reviews that assess the effects of CM on cancer patient outcomes (e.g., QoL, functioning status, symptom management, satisfaction, etc.) and health care utilization outcomes (e.g., cost, hospital admissions, length of stay, treatment received compliance, etc.), 2) summarize measurement used in evaluating patient outcomes and health care utilization outcomes.

This umbrella review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Umbrella Review (UR) methodology [ 12 ] and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of systematic reviews (PRIO) checklist (see Additional file 1 ) [ 13 ]. This review has been registered with the Open Science Framework ( https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/7YQAP ).

Study searching methods

We performed literature search in five databases including MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Scopus from inception to July 2022. Ethical approval and patient consent were not necessary since all analyses were based on previously published articles. The searching strategies in all five databases were developed with the help of a health science librarian. See Additional file 2 for the searching strategy and results in MEDLINE (Ovid). The studies were selected using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Individuals diagnosed with any type of cancer at any cancer stages (early to advanced). Reviews targeted on people with no specified cancer diagnose were excluded.

Intervention

Case management interventions targeted on cancer patients. Case management is defined as a “collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation, and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s and family’s comprehensive health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality, cost-effective outcomes” [ 8 ]. Only reviews in which the effectiveness of CM as defined above was analyzed separately from other interventions were considered.

Individuals in comparison groups received “treatment as usual” (TAU). TAU may include various interventions called “standard of care,” “usual care,” or “standard treatment,” but generally refers to treatment as it is commonly provided. Only studies that compared case management with “TAU” were selected.

Patient outcomes (e.g., quality of life, symptom management, functioning status), health care utilization outcomes (e.g., cost, hospital admissions, length of stay), etc.

Acute care hospitals and primary care settings (e.g., long-term care, nursing homes, community care services). Hospital was defined as any department of internal medicine or surgery as well as unspecified hospital settings.

Study design

Systematic review/meta-analysis that only included quantitative studies. We excluded studies full-texts unavailable online.

Study selection

All retrieved studies were imported into Covidence systematic review software [ 14 ] and the duplicates were removed. Then, titles and abstracts were independently assessed by two researchers (XW and XD) according to the inclusion criteria. After that, the full texts of the selected abstracts were obtained and reviewed by the same two researchers (XW and XD) independently. The reference list of included studies was reviewed and searched for additional studies. Any disagreement between the two researchers were resolved through consultation with a senior researcher (PL).

Quality appraisal for included reviews

Two reviewers (NW and LM) independently assessed the methodological quality of the individual studies using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses [ 15 ]. The tool aims to determine the extent to which the review has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis [ 15 ]. It consists of 11 criteria scored as yes, no, unclear, or not applicable. We adopted a scoring system used in previously published systematic reviews [ 16 , 17 ]. For each article, a rating score was derived by taking the number obtained in the quality rating and dividing it by the total number of possible points allowed, giving each manuscript a total quality rating between 0 and 1. Studies were then classified as low (0–0.25), low-moderate (0.26–0.50), moderate (0.51–0.75), or high (0.76–1.0).

Data extraction

We developed the data extraction form based on the research questions, and extracted following information: characteristics of included reviews such as publication year range, whether conducted meta-analysis or not, type of cancer patients, age of population, type and number of primary studies included; intervention names, components, and duration; outcomes and evaluation tools used; author’s conclusions and interpretations. Two researchers (NW and LM) extracted data independently from all included articles into an Excel spreadsheet and another researcher (XL) verified it for accuracy.

Data synthesis

We were unable to statistically pool outcomes due to the heterogeneity of outcomes of the included reviews. Therefore, we conducted a narrative synthesis [ 18 ] of the numerical data of individual studies outcomes. The studies were summarized and synthesised by two reviewers (NW and ZS) independently and double checked by a third author (HY). Following the JBI UR methodology [ 12 ], we used a summary table to present clear, specific, and structured results from the selected reviews, and then synthesised these results to identify broad conclusions. To summarized information about the interventions we coded data into features, components and delivery strategies, and inductively developed themes within each domain as they emerged from the studies. As suggested by Li and colleagues [ 19 ], we grouped outcomes into: global QoL of patients, functional status (i.e. physical, cognitive, emotional, role, social), symptom management, cost, hospital (re)admission, length of stay, treatment received compliance, provision of timely treatment.

For clarity the term ‘primary studies’ refers to the articles found within the included reviews. As several primary studies are included in more than one review, the overall results and conclusions of an overview can be biased. To assess this bias, the degree of overlap between reviews was calculated with the Corrected Covered Area (CCA) method. The details of the CCA calculation have been described by Pieper and colleagues [ 20 ] elsewhere. A CCA score of less than 5% is regarded as a slight overlap, 5–9.9% as moderate overlap, 10–14.9% as high overlap and over 15% as a very high level of overlap. This measure has been validated in which the number of overlapped primary publications has a strong correlation with the CCA [ 21 ].

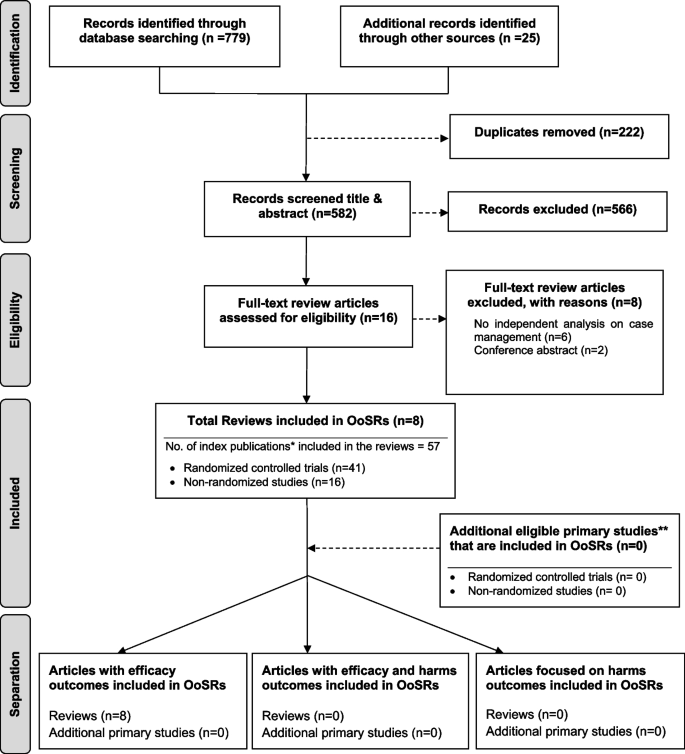

Search outcome

As shown in Fig. 1 , our search strategy generated 804 potentially relevant records. Upon removing the duplicates, 582 studies screened by title and abstract, 16 were identified for full text screening. We excluded eight of the 16 studies for the following reasons: no independent analysis on the effect of case management ( n = 6), or conference abstract ( n = 2). The eight remaining systematic reviews were selected and assessed for methodological quality. In total, all the eight reviews included 57 primary studies, among which 12 were duplicated included in two or three reviews. Forty-one of the 57 primary studies were randomized controlled trials (see Additional file 3 for included primary studies).

Flow chart for umbrella review. *Index publication is the first occurrence of a primary publication in the included reviews. **Additional eligible primary studies that had not been initially indentified by the search of the relevant reviews or obtained by updating the search of the included reviews

Methodological quality assessment

The quality assessment scores are presented in Table 1 . Only one review was rated as moderate because not clarify whether two or more reviewers independently assessed the quality of included primary studies, and did not report the methods to minimize errors in data extraction or publication bias. The other seven reviews were rated as high quality. Despite rated as strong, the seven reviews still companied with one or two issues on the assessment of heterogeneity, search strategy, and recommendations for policy and/or practice.

Characteristics of included studies

Table 2 presents a descriptive summary of characteristics of the eight systematic reviews [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 19 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The eight reviews aimed to identify evidence of the effectiveness of CM on cancer patients. Three of the studies were a systematic review with meta-analysis [ 10 , 25 , 26 ]. Five of the eight reviews adhered to the PRISMA statement [ 11 , 19 , 24 , 25 , 26 ], two adopted Cochrane systematic review methodology [ 9 , 10 ].

The eight reviews were published between 2008 and 2021, the primary studies in the reviews were published between 1983 and 2018. The number of primary studies regarding to CM included in each review ranged from three to 20. Five of the eight reviews included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the remaining reviews included a combination of study designs that involved RCTs, quasi-experimental and non-experimental studies (e.g., cohort study). The age of review participants ranged from 7 to 97 years and mean ages range from 48.63 to 66.31 years, which covers populations from children to elders. The total number of participants in each review ranged from 327 to 9601. Seven of the eight reviews included primary studies targeted on multiple types of cancer including breast, lung, colorectal, cervical, ovarian, prostate, gastric, hepatocellular, etc. Most of the primary studies included in the eight reviews were conducted in the United States, and there were also studies conducted in Canada, Australia, Europe (i.e., Germany, UK, Turkey, Switzerland, Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, Netherlands) and East Asia (i.e., Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, and Malaysia).

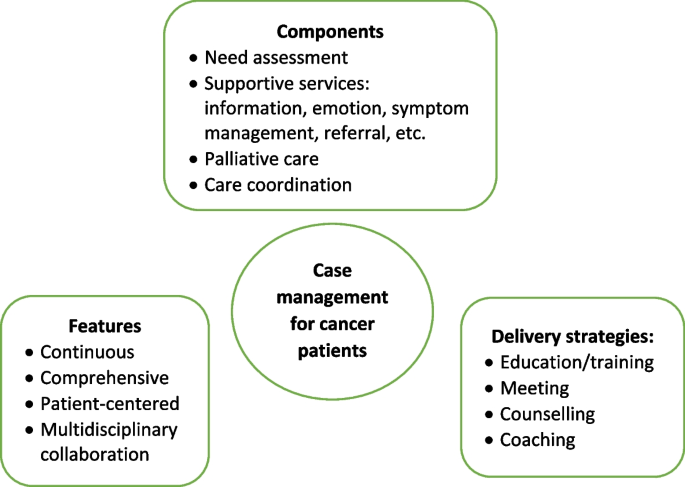

CM interventions

As shown in Table 2 , three studies reviewed trials of nurse-led CM interventions [ 9 , 25 , 26 ], two reviewed CM-like interventions that not termed as ‘CM’ while meet the CM definition by the CMSA [ 8 , 23 , 24 ]. Only one study reviewed CM focus solely on skill-training or symptom management [ 19 ]. All studies reviewed trials that facilitated the CM in a multidisciplinary collaboration approach. The duration of CM ranged from 4 days to 5 years. We presented the feature, components and delivery strategies of CM interventions for cancer patients in Fig. 2 by summarizing descriptions in each review. Congruent with the components defined by CMSA [ 8 ], all CM interventions included patient assessment, supportive services such as information and emotion support, care coordination by conducting education, consultation, and in-person, telephone or online coaching for regular follow-up. One critical component of CM interventions for cancer patients is the provision of palliative care. Control groups (CGs) of all studies reviewed in the reviews received usual treatment of care.

Features, components, and delivery strategies of case management for cancer patient care

Corrected Covered Area (CCA)

Table 3 presents the CCA for each outcome and as a whole. Overall, primary studies had a slight overlap across the eight reviews (CCA = 4.5%). In addition, no overlapping of primary studies was found for six of the 16 outcomes, including self-efficacy, psychological function, hospital (re)admissions, length of stay, and provision of timely treatment. Only one outcome (i.e., symptom management) showed slight overlap (0.7%). The CCA for other five outcomes (i.e., global QoL, physical function, role function, patient satisfaction, cost) evaluated by more than 2 reviews were between 5 to 9.9%, indicated a moderate overlap. The CCA for survivor status, cognitive function, emotional function, and treatment received compliance were over 10%.

Measurement used

Table 4 presents the quantitative measurement used in primary studies. As shown in Table 4 , studies investigated global QoL using different QoL-related scales, among which Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) (used in 15 primary studies) were most frequently applied, followed by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) (used in 11 primary studies), and short form health survey (i.e., SF-8, SF-12, SF-36) (used in 10 primary studies). Different types of FACT tool were used according to the cancer types. For example, FACT-G was used for general cancer patients assessment, and FACT-B was used to evaluate breast cancer-related QoL. For the assessment of overall symptom management, SF-36 and Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) were used most frequently (used in four primary studies each). Different dimensions of SF-36 were also applied to evaluate other outcomes such as physical, emotional, and social function. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was the top employed tool in measuring the psychological function of patients. Patients’ sick leave days and the number of patients return to work were top employed metrics to evaluate the role function of patients. No unified tools were utilized to assess patient satisfaction towards the CM and majority of the primary studies used self-developed questionnaires.

Effect of CM on patient and health care utilization outcomes

The main outcomes from the seven systematic reviews are presented and summarized in Table 5 . Seven of the eight reviews reported the effects of case management on patients’ global QoL and showed mixed findings. Around half (49%, 19/39) of the primary studies included in the seven reviews reported significant positive impact of CM on global QoL. As for the functional status, there was a strong concordance among primary studies regarding the effectiveness of CM in improving cognitive function (e.g., uncertainty, health perceptions) (89%, 8/9); Equivocal effects were reported on psychological (e.g., patient anxiety, depression), physical (e.g., arm function), role function (e.g., sick leave days, patients returning to work), emotional (e.g., mood) and social function (e.g., social support) [ 9 , 11 , 26 ]. The findings regard to symptom management were more positive, with 75% (18/24) primary studies included in seven reviews revealed significant positive impact of CM on symptom severity and symptom distress decrease of pain, nausea, fatigue, discomfort, etc. Three of the four primary studies in two reviews [ 9 , 11 ] showed no significant influence of CM on patients’ self-efficacy. Wulff et al. [ 23 ] and Aubin et al. [ 10 ] reported mixed findings on the impact of CM on survivor status, with four of the six primary studies reported significant positive impact. The effect of CM on patient satisfaction was reported in five reviews and showed mixed results.

Of the eleven primary studies reported cost, only one controlled before-and-after study in Joo et al.’s [ 9 ] review reported significant impact on monthly cancer-related medical costs. The evidence concerning patients’ length of stay yielded no significant findings. Overall significant positive effect was reported on hospital (re)admission (e.g., inpatient and ICU admission rate), treatment received compliance (e.g., therapy acceptance or completion rate), and provision of timely treatment.

This umbrella review is the first to summarize the results of systematic reviews that synthesised the evidence on the effectiveness of CM on cancer patient outcomes and relevant health care utilization. Most reviews (7/8) showed a high methodological quality. Different tools were used to measure the effect of CM on the same outcome. The evidence regards to the effectiveness of CM is mixed. The summarized results revealed that CM was more likely to improve symptom management, cognitive function, hospital (re)admission, treatment received compliance, and provision of timely treatment for cancer patients. Overall equivocal effect was reported on cancer patients’ global QoL, psychological, physical, role, emotional and social function, self-efficacy, survivor status, and patient satisfaction.

No universal tools were used to measure improvement of each outcome in the CM group compared with the control group, making it challenging to conduct a meta-analysis of studies results [ 22 , 27 ]. This is a common issue faced the included reviews. Five of the eight reviews failed to conduct meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity [ 9 , 11 , 19 , 23 , 24 ]. Joo and Huber [ 22 ] conducted a review of reviews on the effect of CM on health care utilization outcome of chronic illness patients, they recognized the same problem and suggested using valid and standardized tools to minimize the differences in measurements. Despite various tools used, our review showed that FACT, EORTC QLQ-C30, and short form health survey (i.e., SF 36, SF 12, and SF 8) were most frequently applied to measure the effect of CM on the global QoL of cancer patients. These tools were also used in evaluating specific dimensions of QoL such as psychological, physical, emotional, and social function. This aligned with previous reviews [ 28 , 29 ] that found FACT and EORTC QLQ-C30 were the most common and well developed QoL instruments in cancer patients. FACT-G is considered appropriate for use with any types of cancer patients [ 30 ]. It is a 27-item tool that includes four primary QoL domains: physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, and functional well-being [ 31 ]. Other versions of FACT (FACT-B [ 32 ], FACT-L [ 33 ] and FACT-E [ 34 ]) for specific type of cancer patients were developed by incorporating the four dimensions of FACT-G with additional cancer type-specific questions. EORTC QLQ-C30 was another type of QoL assessment tools for cancer patients specifically. It was developed by Aaronson et al. [ 35 ] and contains four domains: physical, emotional, cognitive and social functions, and a higher score indicates better QoL. The Short Form Health Survey is the most commonly used measure in evaluating QoL domains of patients suffering from a wide range of medical conditions [ 36 ]. Research found it provides reliable and valid indication of general health among cancer patients [ 37 , 38 ].

QoL is the most frequently evaluated outcome in our review with 39 primary studies in seven reviews reported the global QoL of cancer patients. Joo et al. [ 9 ] found that CM interventions improved QoL of cancer patients. Yin and colleagues [ 24 ] revealed that cancer patients achieved better physical and psychological condition through symptom management, needs assessment, direct referrals, and other services in CM. However, summarized results in our review show that the CM had equivocal effect on cancer patients’ global QoL and dimensions including psychological, physical, role, emotional and social function. Cognitive function is the only dimension showed positive change. Despite CM interventions share similar definitions and principles [ 8 ]. It is hard to foresee which aspect(s) of CM interventions contribute to certain effects due to their comprehensiveness [ 24 ]. Yin et al. [ 24 ] argued that the control group may receive a higher quality treatment than planned usual care since all the participants were not blinded and they have been informed about the aim of the study. Indicating a more rigorous design and evaluation is needed to avoid this information bias.

In the meantime, included reviews claimed that few primary studies reported enough details about CM interventions, including model used [ 10 , 11 ], dose and intensity [ 9 , 19 , 24 ], interventionist qualifications [ 11 ], protocol or manual used [ 9 , 23 ], and fidelity [ 23 ]. Particularly, the COVID-19 pandemic has considerable influence on the care delivery for cancer patients. For example, the more frequently utilization of remote patient monitoring technologies that incorporate community resources, primary care and allied health disciplines, as well as clinics to keep cancer patients away from acute care hospitals as much as possible [ 39 ]. Many of these changes have been integrated within routine case management for cancer care during the pandemic [ 39 ]. It is well-needed to report how those CM intervention were conducted follow standard reporting guidelines, in order to provide recommendation for future research.

Our review showed that CM is likely to improve the symptom management. Eighteen of the 24 included primary studies reported positive effect of CM on symptom management, including decrease symptom distress or severity of fatigue, pain, nausea, and vomiting. The same positive effect on symptom management was also revealed in other types of patients. Joo and colleagues [ 40 ] found that CM reduced substance use and significantly influenced abstinence rates among populations experienced substance disorders. Reviews by Stokes et al. [ 27 ] and Welch et al. [ 41 ] revealed positive effect on symptom release among people with long-term conditions and diabetes patients, respectively. The multidisciplinary collaboration approach adopted [ 10 ], and availability of professional support post-hospitalization [ 9 , 41 ] in CM might contribute to the improvement of symptom management. Specifically, multidisciplinary team involves physicians, nurses, and aligned healthcare professionals provides throughout and multifaced symptom assessment and management [ 10 ]. In addition, CM programs continuously follow up and advocate for patients’ concerns [ 8 ]. Specifically, case managers are available to patients 24 hours a day by phone call even after discharged, providing opportunity for immediate professional guidance on symptom management [ 9 ].

As for other patient outcomes, there is insufficient evidence of effect on self-efficacy and survivor status of cancer patients. Only three and four primary studies in total reported these two outcomes, respectively. Eleven primary studies in five reviews reported patient satisfaction and showed mixed results. Inconsistent results were found in a review of reviews by Buja et al. [ 7 ] which concluded strong evidence of CM improving satisfaction of patients with long term condition. In agreement with Joo and Huber’s [ 25 ] review, we found that CM favorably affect healthcare utilization outcomes such as treatment received compliance, hospital (re)admission, and provision of timely treatment. While the strength of the evidence was limited either by the high level of primary studies overlapping (CCA) (i.e., treatment received compliance, CCA = 13.3%) or the small number of studies reported certain outcomes (i.e., hospital admission, provision of timely treatment). Notably, the summarized results from included reviews conclude that despite theoretical benefits [ 8 ], in practice there is only slight evidence of benefits on reduction in the cost of care for cancer patients participated in CM interventions.

We provide some recommendations for future research based on the summarized results: 1) Future research should clearly describe details of CM intervention and its implementation, including theoretical underpinnings, dose and intensity, interventionist qualifications, protocol or manual used, fidelity, etc. In that way these details can be included in future systematic reviews, and effectiveness of individual elements of the intervention can be examined [ 27 ]. We recommend use standard guidelines to help organize the CM intervention reporting. For example, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDeiR) is one of the most popular guidelines that could be used to report the full breadth of CM interventions: from intervention rationale to assessments of treatment adherence and fidelity [ 42 ]. 2) More rigorous trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of CM. 3) Studies should also explore the barriers to and facilitators of CM implementation across various types of cancer patients at different stages, providing evidence for conducting successful CM implementation in the future.

Strengths and limitations

We conducted an umbrella review instead of a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of review outcomes. Although an umbrella review can only show the tendency or direction of the effect of CM rather than providing the magnitude or significance level of influence [ 12 ], the current evidence on the effect of CM in cancer patients was comprehensively summarized. There were some challenges when conducting the review. First, the quality of the umbrella reviews was greatly affected by the quality of the original reviews [ 12 ]. In this study, we confirmed that the quality of the original reviews were mostly high as assessed by the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist [ 15 ]. Second, if the primary studies were included in several reviews, they may produce bias related to overlapping effects [ 20 ]. By calculating the CCA, we showed that 75% (12/16) of the individual outcomes had no to moderate overlapping of primary studies between included reviews, revealing that these results from each review were relatively independent. Cautious are needed on the summarized evidence regards to the effect of CM on survivor status, cognitive function, emotional function, and treatment received compliance because of the high overlapping (CCA > 10) between the reviews reported those outcomes.

There are limitations in our review. The first limitation concerns that the searching was limited to English-language articles and did not access unpublished papers. Second, as suggested by the JBI UR methodology [ 12 ], we did not assess the quality of evidence from included reviews, it increased the uncertainty of the review findings.

Effective CM aims to influence the health care delivery system in improving the health outcomes of cancer patients, enhancing their experience of health care, and reducing the cost of care. Our review found mixed effects of CM reported in cancer patient care. The summarized results revealed that CM was likely to improve symptom management for cancer patients. We also found CM has the tendency to enhance cancer patients’ experience of health care such as reducing hospital (re)admission rates, improving treatment received compliance and provision of timely treatment. Only slight evidence of benefits was reported on reducing the cost of care for cancer patients. Overall, more rigorous designed primary studies are needed to demonstrate the effects of CM on cancer patients and explore the elements of effective CM interventions.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

Corrected Covered Area

Control groups

- Case management

Case Management Society of America

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire 30

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Breast Cancer

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- Esophagus

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy- General

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale-Lung

- Quality of life

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

Joanna Briggs Institute

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Randomized controlled trials

Symptom Distress Scale

Medical Outcomes Study 8-item short form health survey

Medical Outcomes Study 12-item short form health survey

Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey

Treatment as usual

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, et al. Global cancer observatory: Cancer today: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today .

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, et al. Global Cancer observatory: Cancer tomorrow: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow .

Quaresma M, Coleman MP, Rachet B. 40-year trends in an index of survival for all cancers combined and survival adjusted for age and sex for each cancer in England and Wales, 1971-2011: a population-based study. Lancet. 2015;385:1206–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61396-9 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Banegas MP, Davidoff A, Han X, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:259–67. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468 .

Yan AF, Stevens P, Holt C, Walker A, Ng A, McManus P, et al. Culture, identity, strength and spirituality: a qualitative study to understand experiences of African American women breast cancer survivors and recommendations for intervention development. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28:e13013. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13013 .

Article Google Scholar

Yabroff K, Mariotto A, Tangka F. Annual report to the nation on the status of Cancer, part II: patient economic burden associated with Cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:1670–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djab192 .

Buja A, Francesconi P, Bellini I, Barletta V, Girardi G, Braga M, et al. Health and health service usage outcomes of case management for patients with long-term conditions: a review of reviews. Prim Heal Care Res Dev. 2020;21:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423620000080 .

Case Management Society of America. CMSA’s standards of practice for case management, Revised 2016. 2016. http://www.naylornetwork.com/cmsatoday/articles/index-v3.asp?aid=400028&issueID=53653 .

Google Scholar

Joo JY, Liu MF. Effectiveness of nurse-led case Management in Cancer Care: systematic review. Clin Nurs Res. 2019;28:968–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773818773285 .

Aubin M, Giguère A, Martin M, Verreault R, Fitch MI, Kazanjian A, et al. Interventions to improve continuity of care in the follow-up of patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:1–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007672.pub2 .

Chan RJ, Teleni L, McDonald S, Kelly J, Mahony J, Ernst K, et al. Breast cancer nursing interventions and clinical effectiveness: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10:276–86. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002120 .

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-11 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Bougioukas KI, Liakos A, Tsapas A, Ntzani E, Haidich AB. Preferred reporting items for overviews of systematic reviews including harms checklist: a pilot tool to be used for balanced reporting of benefits and harms. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;93:9–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.002 .

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review sofware. Covidence. 2016. https://get.covidence.org/systematic-review-software?campaignid=15030045989&adgroupid=130408703002&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIvc7KuJDO-QIVh97ICh1BeQKnEAAYASAAEgI4APD_BwE .

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Kahlil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Heal. 2015;13:132–40 http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html .

Gifford W, Rowan M, Dick P, Modanloo S, Benoit M, Al AZ, et al. Interventions to improve cancer survivorship among indigenous peoples and communities : a systematic review with a narrative synthesis. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:7029–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06216-7 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gifford W, Squires J, Angus D, Ashley L, Brosseau L, Craik J, et al. Managerial leadership for research use in nursing and allied health care professions : a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0817-7 .

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods Programme. Lancaster: Lancaster University; 2006. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf .

Li Q, Lin Y, Liu X, Xu Y. A systematic review on patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivors of randomised clinical trials: direction for future research. Psychooncology. 2014;23:721–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3504 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pieper D, Antoine SL, Mathes T, Neugebauer EAM, Eikermann M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:368–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.007 .

Choi J, Lee M, Lee JK, Kang D, Choi JY. Correlates associated with participation in physical activity among adults: a systematic review of reviews and update. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4255-2 .

Joo JY, Huber DL. Case management effectiveness on health care utilization outcomes: a systematic review of reviews. West J Nurs Res. 2019;41:111–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945918762135 .

Wulff CN, Thygesen M, Søndergaard J, Vedsted P. Case management used to optimize cancer care pathways: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:1–7 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/8/227 .

Yin YN, Wang Y, Jiang NJ, Long DR. Can case management improve cancer patients quality of life?: a systematic review following PRISMA. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000022448 .

Wu YL, Padmalatha KMS, Yu T, Lin YH, Ku HC, Tsai YT, et al. Is nurse-led case management effective in improving treatment outcomes for cancer patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2021;00:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14874 .

McQueen J, McFeely G. Case management for return to work for individuals living with cancer: a systematic review. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2017;24:203–10. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2017.24.5.203 .

Stokes J, Panagioti M, Alam R, Checkland K, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Bower P. Effectiveness of case management for “at risk” patients in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132340. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132340 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lemieux J, Goodwin PJ, Bordeleau LJ, Lauzier S, Théberge V. Quality-of-life measurement in randomized clinical trials in breast cancer: an updated systematic review (2001-2009). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:178–231. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq508 .

Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:1–31 https://jeccr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1756-9966-27-32 .

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 .

Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The F unctional a ssessment of C hronic I llness T herapy (FACIT) measurement system: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-79 .

Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR, et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy- breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:974–86. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1997.15.3.974 .

Cella DF, Bonomi AE, Lloyd SR, Tulsky DS, Kaplan E, Bonomi P. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-lung (FACT-L) quality of life instrument. Lung Cancer. 1995;12:199–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5002(95)00450-F .

Darling G, Eton DT, Sulman J, Casson AG, Cella D. Validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy esophageal cancer subscale. Cancer. 2006;107:854–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22055 .

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 .

Ware J, Kosinski M, Dewey J. How to score version two of the SF-36® health survey. Lincoln: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2000.

Treanor C, Donnelly M. A methodological review of the short form health survey 36 (SF-36) and its derivatives among breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:339–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0785-6 .

Lins L, Carvalho FM. SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: scoping review. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312116671725 .

Chan RJ, Crawford-Williams F, Crichton M, Joseph R, Hart NH, Milley K, et al. Effectiveness and implementation of models of cancer survivorship care: an overview of systematic reviews. J Cancer Surviv. 2021:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01128-1 .

Joo J, Huber D. Community-based case management effectiveness in populations that abuse substances. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:536–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12201 .

Welch G, Garb J, Zagarins S, Lendel I, Gabbay RA. Nurse diabetes case management interventions and blood glucose control: results of a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2009.12.026 .

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Dual (co-)authorship

We declared that no author has authored one or more of the included systematic reviews.

This study was supported by 1) Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Nursing (2017TP1004, PI: Jia Chen), Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Department, 2) Changsha Natural Science Foundation (kq2202365, PI: Nina Wang) Changsha Science and Technology Department, and 3) Management research foundation of Xiangya Hospital (2021GL12, PI: Nina Wang).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Respiratory Medicine, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China

Nina Wang, Zhengkun Shi & Huaping Yang

National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders, Xiangya Hospital, Changsha, China

Xiangya School of Nursing, Central South University, Changsha, China

Jia Chen, Chen Wang & Xianhong Li

School of Nursing, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Wenjun Chen

Center for Research on Health and Nursing, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Intensive Care Unit of Cardiovascular Surgery Department, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China

Peng Liu & Xiangling Dong

The 956th Army Hospital, Linzhi, China

School of Nursing, Changsha Medical University, Changsha, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors have contributed to the production of this review. NW and WC conceptualized and designed the study and are the guarantor of the paper. JC and ZS conducted the literature search. PL, XW and XD were involved in the study screening. NW, LM and XL participated in the quality appraisal and data extraction. NW, ZS and HY conducted the data analysis. NW drafted the manuscript. WC and XL revised the manuscript. All authors participated in the review of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wenjun Chen .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., additional file 2..

Searching strategies.

Additional file 3.

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wang, N., Chen, J., Chen, W. et al. The effectiveness of case management for cancer patients: an umbrella review. BMC Health Serv Res 22 , 1247 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08610-1

Download citation

Received : 04 April 2022

Accepted : 21 September 2022

Published : 14 October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08610-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cancer patients

- Umbrella review

- Health care

- Outcome assessment

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Patient Case Presentation

Patient Mrs. B.C. is a 56 year old female who is presenting to her WHNP for her annual exam. She had to cancel her appointment two months ago and didn’t reschedule until now. Her last pap smear and mammogram were normal. Today, while performing her breast exam, her nurse practitioner notices dimpling in the left breast as the patient raises her arms over her head. When the NP mentions it to Mrs. B.C. she is surprised and denies noticing it before today. A firm, non-tender, immobile nodule is palpated in the upper quadrant of her breast . The NP then asks Mrs. B.C. how frequently she is performing breast self-exams, she admits to only doing them randomly when she remembers, which is about every few months. She reports no recent or abnormal drainage from her breast. Further examination reveals palpable axillary lymph nodes.

Mrs. B.C. is about 30 pounds overweight and walks her dog around her neighborhood every morning before work and every evening when she gets home. She reports drinking a glass of white wine before bed each night. She denies any history of tobacco use. She reports use of a combination birth control pill on and off for 25 years until she reached menopause. She is not currently taking any prescription medications.

Past Medical History

- Menarche (Age 10)

- Post-menopausal (Age 53)

- No other pertinent medical history

Family History:

- Father George- deceased from stroke (75 years old), history of hypertension, CAD, HLD

- Mother Maryanne alive- 76 years old, history of dementia, osteoporosis

- Brother Michael- alive, 57 years old, history of hypertension, CAD and cardiac stent placement (54 years old)

- Sister, Michelle- alive 53 years old, history of GERD, Asthma

- Brother- Jimmy- alive 50 years old, no past medical history

Social History:

Mrs. B.C. works Monday-Friday 8am-5pm at the local dentist’s office at the front desk as a schedule coordinator. She is planning to retire in a few years. In her spare time, she is involved in various community efforts to feed the homeless and helps to prepare dinners at her local church one night a week. She also enjoys cooking and baking at home, gardening, and nature photography.

Mrs. B.C. has two children. Her oldest son, Patrick, is 21 years old and is in his final year of pre-med. He is attending a public university about 2 hours away from home where he lives year-round. As an infant, Patrick was breastfed until 18 months when he self-weaned. Her daughter, Veronica, is 19 years old and lives at home while attending the local branch campus of a state university. She is in her second year of a business degree and then plans to transfer to the main campus next year. When Veronica was an infant she had difficulty latching onto the breast due to an undiagnosed tongue and lip ties resulting in Mrs. BC exclusively pumping and bottle feeding for six months. After six months, Mrs. B.C. was having a hard time keeping up while working and her found her supply diminished. Veronica had begun eating solid foods so Mrs. B.C. switched to supplemental formula, which was a big relief.

Mrs. B.C. was married to her now ex-husband Kent for 26 years. They divorced two years ago when Veronica was a senior in high school. They have remained friends and Kent lives 25 minutes away in a condo with his girlfriend. She also has two brothers who live nearby and a sister who lives out of state. Her 7 nieces and nephews range in age from 9 years old to 26 years old. Her father, George, passed away from a sudden stroke 4 years ago. Her mother, Maryanne, has dementia and is living in a nearby memory care facility. She also has many close friends.

Together we are beating cancer

About cancer

Cancer types

- Breast cancer

- Bowel cancer

- Lung cancer

- Prostate cancer

Cancers in general

- Clinical trials

Causes of cancer

Coping with cancer

- Managing symptoms and side effects

- Mental health and cancer

- Money and travel

- Death and dying

- Cancer Chat forum

Health Professionals

- Cancer Statistics

- Cancer Screening

- Learning and Support

- NICE suspected cancer referral guidelines

Get involved

- Make a donation

By cancer type

- Leave a legacy gift

- Donate in Memory

Find an event

- Race for Life

- Charity runs

- Charity walks

- Search events

- Relay For Life

- Volunteer in our shops

- Help at an event

- Help us raise money

- Campaign for us

Do your own fundraising

- Fundraising ideas

- Get a fundraising pack

- Return fundraising money

- Fundraise by cancer type

- Set up a Cancer Research UK Giving Page

- Find a shop or superstore

- Become a partner

- Cancer Research UK for Children & Young People

- Our We Are campaign

Our research

- Brain tumours

- Skin cancer

- All cancer types

By cancer topic

- New treatments

- Cancer biology

- Cancer drugs

- All cancer subjects

- All locations

By Researcher

- Professor Duncan Baird

- Professor Fran Balkwill

- Professor Andrew Biankin

- See all researchers

- Our achievements timeline

- Our research strategy

- Involving animals in research

Funding for researchers

Research opportunities

- For discovery researchers

- For clinical researchers

- For population researchers

- In drug discovery & development

- In early detection & diagnosis

- For students & postdocs

Our funding schemes

- Career Development Fellowship

- Discovery Programme Awards

- Clinical Trial Award

- Biology to Prevention Award

- View all schemes and deadlines

Applying for funding

- Start your application online

- How to make a successful application

- Funding committees

- Successful applicant case studies

How we deliver research

- Our research infrastructure

- Events and conferences

- Our research partnerships

- Facts & figures about our funding

- Develop your research career

- Recently funded awards

- Manage your research grant

- Notify us of new publications

Find a shop

- Volunteer in a shop

- Donate goods to a shop

- Our superstores

Shop online

- Wedding favours

- Cancer Care

- Flower Shop

Our eBay store

- Shoes and boots

- Bags and purses

- We beat cancer

- We fundraise

- We develop policy

- Our global role

Our organisation

- Our strategy

- Our Trustees

- CEO and Executive Board

- How we spend your money

- Early careers

Cancer news

- Cancer News

- For Researchers

- For Supporters

- Press office

- Publications

- Update your contact preferences

ABOUT CANCER

GET INVOLVED

NEWS & RESOURCES

FUNDING & RESEARCH

You are here

Patient data use case studies

Questions about these case studies or how patient data is handled?

Contact the team

During our Review of Informed Choice for Cancer Registration, patients clearly told us they would like to know what their data are being used for. We agreed that as a charity, we would highlight where we are using patient-data for research and analysis. Relevant examples of work by the Cancer Intelligence team at Cancer Research UK will be available here, and we will add to this as we embark on new projects.

Lung cancer diagnostic pathways

Identifying common lung cancer diagnostic pathways using linked datasets.

Small proportions of patients in 2013-2015 meet the timings of the optimal pathway. Diagnostic pathway length varies by source of imaging request.

Variation in ovarian cancer treatment rates

Investigating variation in treatment for ovarian cancer patients.

We expect to establish if there is variation between Cancer Alliances/Trusts, identify the odds ratios/ regression co-efficients for predictor variables, and if it's the affect of healthcare system level factors.

Variation in lung cancer treatment rates

Investigating variation in treatment for non-small cell lung cancer patients.

We expect to establish if there is significant variation between Cancer Alliances/Trusts (geography still to TBC) and identify the odds ratios/regression co-effecients associated with each predictor variable.

Bowel cancer screening campaign evaluation

Evaluating the bowel cancer screening regional pilot campaign in the North West of England.

Analysis of interim results following the campaign are promising. We are currently working to finalise the analysis and results will follow in due course.

Colorectal cancer diagnostic pathways

Coming soon.

The impact of COVID-19 on radiotherapy in the UK

The aims of COVID RT are to understand why changes in radiotherapy treatment schedules were implemented during the pandemic and to then explore the impact of these changes on patient outcomes and the UK radiotherapy services. This project aims purely to understand the changes in patient's radiotherapy treatment from COVID-19.

Patient data – a vital tool that will help beat cancer

Cancer is the most complex health challenge that we face. There are 200 different types of cancer but even that is an oversimplification.

At a genetic level each individual cancer is as unique as the person with the disease. Despite this complexity our research has helped double cancer survival over the last 40 years. This extraordinary progress has been powered by relentlessly increasing our understanding of cancer’s intricacies.

But big questions about cancer remain, and our scientists are seeking the answers. Patient data has the potential to reveal some of these. Here we meet some outstanding scientists who are using patient data to grow our understanding even further, work that could underpin tomorrow’s cures.

Case study 1 – Prof. Crispin Miller

Professor_crispin_miller.jpg.

At the heart of the CRUK Scotland Institute is a team of brilliant scientists, led by Professor Crispin Miller, who specialise in using super computers to understand how cancer behaves.

This diverse and talented team - which includes mathematicians, physicists, biologists and software engineers - are using a range of techniques to dig deep into the huge amounts of data we have on the genetics and anatomy of tumours.

“Biology is exciting” says Crispin. “The questions of modern cancer research, like how the DNA in one cell can define an entire living person – to me that’s as exciting as understanding the first few microseconds of the Big Bang.”

Crispin’s goal is to identify patterns in a tumour’s DNA or its structure that might help us better understand why and how cancers develop. And ultimately this could inform how best to treat them.

But spotting those crucial patterns is difficult because tumours are so diverse. And so Crispin’s team turn to supercomputers. These powerful tools can sift through vast amounts of information to find patterns that would be impossible for a human to spot. Then the scientists can do what they do best – work out how the patterns are driving cancer progression or making a tumour more or less sensitive to an anticancer drug.

Professor Miller explains: “Data gives us insight into things you can’t see down a microscope. It has the potential to start developing truly targeted therapies. To find the right therapy for the right person at the right time that is the goal.”

His team are using a data approach on many different cancer-related questions. In one project, patients have kindly allowed their doctors to share anonymised scan images of tumours and the tumour genetic data. Crispin’s team are seeing whether they can build a sophisticated AI approach that has the power to use this data to predict how tumours are going to respond to treatment. This could help doctors pick the best treatment for each person.

What nearly all Professor Miller’s work has in common is that it is only possible due to the data that people with cancer have shared.

“Data is central to the research we are doing. The more tumours we study, the more we understand how they differ from each other and how we can use this information to improve outcomes for people with cancer. I am incredibly grateful to the patients who donate their data and tissue, I couldn’t do my work without it.”

Case study 2 – Dr Irene Lobon

“Data is everything” – how patient data is helping us understand how cancer spreads and resists treatment

For Dr Irene Lobon, everything is data and data is everything. From calculating nutrients in new recipes to studying tumour samples, analysing data is central to her life and work. While in her spare time Dr Lobon’s analytical skills help her to optimise her favourite recipes, in the laboratory, these skills could lead to lifesaving discoveries.

Dr Lobon is a biomedical researcher in the Cancer Dynamics Laboratory, led by Professor Samra Turajlic at The Francis Crick Institute. She works on a multidisciplinary team featuring scientists and clinicians, all working together to better understand cancer.

The team are studying advanced, spreading melanoma, called metastatic melanoma. This is a type of skin cancer that is particularly hard to treat and often becomes resistant to drugs. Professor Samra’s group want to know how melanoma changes over time, what happens inside the tumour as it spreads and what features lead to drug resistance. To answer these questions, the team relies on patient data. Specifically, samples from patients who have passed away from cancer.

To access these samples, the team makes use of the PEACE (Posthumous Evaluation of Advanced Cancer Environment) study, a huge collaborative project, set up to help researchers collect samples from patients who have died from cancer. In this study, researchers take samples from participants during their treatment journey and after they have died. This huge assembly of data has allowed clinicians and scientists to study cancer in a way that was not possible before.

Professor Turajlic’s team employed sophisticated genetic sequencing techniques to study nearly 600 separate samples from 14 different patients with metastatic melanoma from the PEACE study. “What we’ve observed is that there are many variables that contribute tiny bits to the cancer progression” said Dr Lobon.

Uncovering these small contributions allowed the team to piece together a complex timeline of how the cancer develops. “It’s like having a fossil. We can study cancers at different points in time.”

The team shared the results of this extensive study with the scientific community earlier this year. The incredible information uncovered has helped scientists to understand the complex ways that melanomas use to evade drugs. The researchers hope that it could also lead to the development of completely new drugs that could provide hope for those diagnosed with metastatic melanoma.

While Professor Samra’s team are using the PEACE study to study metastatic melanoma, there are many other scientists using the valuable data collected to investigate other cancer types. There are researchers investigating lung cancer, renal cancer and many more. What they have in common, is their reliance on patient data.

Dr Lobon emphasised that her work would be impossible without the generous people who agree to donate their samples after they pass. “It’s extremely important. There is no other way we could get such specific information without these samples.”

“Data is everything.”

Case study 3 – Prof Rebecca Fitzgerald

Professor_rebecca_fitzgerald.jpg.

Oesophageal cancer is one of the biggest challenges in cancer research today. The underlying biology of the disease is poorly understood and survival remains very low, with only 1 in 10 people surviving their disease for 10 years or more. It’s a big challenge – and one that researchers and clinicians can’t tackle alone.

For over 10 years, Professor Rebecca Fitzgerald at the University of Cambridge has been spearheading a huge project that brings together scientists, doctors and nurses from across the UK with the goal of better understanding oesophageal cancer.

Known in the research community as OCCAMS (Oesophageal Cancer Clinical and Molecular Stratification), this impressive programme of work has seen researchers collecting tumour and blood samples from people with oesophageal cancer and decoding the cancer’s genetic sequence so that they have a complete map of the cancer’s DNA.

These samples provide a treasure trove of information, allowing scientists to see how changes in DNA sequence affects progression of oesophageal cancer. And every person’s data provides a new piece of the puzzle.

“This really is a team effort,” says Rebecca. “By sharing information, we can see the patterns and the trends and that’s what allows the breakthroughs to happen. Right now we can’t predict how well someone will do just by how they look when we first see them in the clinic. Some people do well, and sadly some people do badly, and we need to know why.”

And there are a lot of questions that need answering. How do genetic changes in the cancer change the way it develops over time? Are there specific risk factors that could predict if oesophageal cancer is going to recur? Why do some people respond well to treatment and some people don’t? All these questions rely on matching up clinical data (data collected by doctors about how each person’s cancer progresses) with laboratory data (data that comes from samples that scientists take away to analyse in the lab).

“And we need a lot of data,” explains Rebecca. “Oesophageal cancer is really complicated. We can’t find the needle in the haystack by just using data from a few people. The current problem my team is working on – working out whether all oesophageal cancers start from the precursor condition Barrett’s oesophagus – is using data from 4,000 patients. And that is why we are so grateful to all the patients who allow us to do this work.”

In the end, this work is all driven by the desire to make the situation better for people with oesophageal cancer. Already the team have been able to describe for the first time some of the DNA mutations that they think cause cancer, and there are likely to be many more findings to come.

“We have seen some improvements over the 20 years I have been working on this,” reflects Rebecca, “but we’ve got a long way to go. Solving this problem is what gets me out of bed in the morning. And I want to get to the end of my career and see that it is really different. I can’t do what I do without patient data – and I am not done yet.”

Case study 4 – Dr Rajesh Jena

Personalising radiotherapy – how patient data is helping reduce the side effects of treatment

Radiotherapy is the gold standard of treatment for many types of cancers. In fact, more than 130,000 patients benefit from radiotherapy every year in the UK. Today, most people receive image-guided radiotherapy – that is, using imaging such as x-rays and MRIs to target the beam of radiation to the tumour site, to make it as accurate as possible.

“Many people think about imaging at the point of diagnosis to find a tumour, or to follow up on treatment to see if its working,” says Dr Rajesh Jena, a clinician scientist based in Cambridge who is finding ways to improve radiotherapy for people with tumours of the brain and spine. “But imaging can be so much more: it can be used to personalise and even predict response to treatment.”

With radiotherapy there can be side effects because the beam of radiation can also affect healthy tissue surrounding the tumour. Combining imaging while delivering radiotherapy can help minimise these side effects, and getting better at combining these approaches is where patient data can be so important.

By studying images taken during radiotherapy, researchers can determine which healthy tissues were affected by the radiation, and then use that information to help predict how a new patient might respond to treatment, potentially altering the treatment plan to make it as side-effect free as possible.

“The wealth of information an image holds comes with an incredible potential,” says Dr Jena. Such potential to inform patient care led Dr Jena and his team to develop the first continuously learning artificial intelligence (AI) medical device in his hospital. Using patient data to train the AI, they were able to develop a tool that speeds up analysis of images. The technology helps doctors by cutting the amount of time spent ‘sketching’ around healthy organs, as they create radiotherapy plans, a painstaking yet vital step in radiotherapy treatment to ensure healthy tissue is protected.

And this data offers value far beyond direct medical treatment. “It’s not only doctors that need access to imaging data like this,” Dr Jena adds. “Patients are so generous allowing us to use this data, so we try to maximise its value by working with mathematicians, physicists, biologists and many other experts.” Bringing together different specialisms like this gives the scientists the best chance of understanding a disease as complex as cancer.

“And we also look back at historical patient images – this is important to provide context, improve our understanding and build up a valuable database of information.”

Thanks to patient data, Dr Jena and his team have already been able to create a technology that frees up valuable time and ultimately enable patients to receive treatment sooner. Over the next year, Dr Jena and his team are working on improving this technology by providing the AI with even more examples of patient images to learn from, allowing it to become better than ever at identifying healthy tissue.

“We’re so grateful to have access to patient imaging data because without it we wouldn’t be able to develop technologies like this, which can make a real difference to people with cancer. We’re very careful with how we use patient data, we take care to ensure that all data is anonymised and is treated with respect.”

Case studies in detail

The earlier diagnosis of lung cancer will save lives but also puts additional pressure on diagnostic services. It is therefore important that lung cancer pathways are organised to be as effective and efficient as possible and to ensure patients are given their diagnosis as soon as possible.

We hoped to improve understanding of pre-diagnostic events, intervals and patterns for lung cancer patients on a national scale, and to benchmark to the timings in the newly adopted National Optimal Lung Cancer Pathway (NOLCP).

The data used included: lung cancer registrations (2013-2015) from National Cancer Registration Analysis Service (NCRAS), diagnostic imaging data (DID) and cancer waiting times (CWT) data from NHS England; and involved data from over 100,000 patients.

Following data linkage, time intervals between events were calculated, different scenarios of events were investigated and timings of events were compared with those from the NOLCP.

Many different diagnostic scenarios exist, from simple to complex, which varies by CCG. Time intervals from imaging to diagnosis differed by source of image referral, with those ordered by GP direct access imaging having longer pathways. Benchmarking to the NOLCP timings showed small proportions (less than 6%) of patients meeting timings, this also varied widely by CCG.

Partners: ACE Programme (funded by CRUK, Macmillan, NHS England), CRUK-NHS England Partnership, NCRAS

See also: ACE Programme website , More in-depth findings

Survival for ovarian cancer in the UK is lower than other comparable high-income countries and there is substantial regional variation within the UK. Access to and/or quality of treatment may be contributing factors.

This analysis will establish a detailed picture of ovarian cancer treatments and outcomes and is intended to provide initial insights into a planned national ovarian cancer audit benchmarking pilot, with the ultimate aim to act as a catalyst to reduce variation and drive improvements to clinical practice.

Data used will be: patients diagnosed with ovarian cancer (1st July 2014 to 31st March 2015) who were eligible for chemotherapy; information about their tumour, chemotherapy treatment received, and demographic information.

The linked data will be used to compare treatment access rates between Cancer Alliances and/ or Trust of Multi-Disciplinary Team/diagnosis, to determine the extent to which this can be explained by regional differences in patient demographics, such as age and socioeconomic status, and we will investigate the influence of healthcare system levels factors on access to treatment, such as provider and type, and consultant volume and specialisation.

Findings are due Winter 2018, but we expect to find how much geographical variation in access to treatment for ovarian cancer there is in England, and to what extent is this affected by patient demographics and healthcare system level factors.

Partners: NHS England

The purpose of this service evaluation is to establish; factors that affect access to lung cancer treatments for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, whether there is variation between Cancer Alliances/ hospital trusts in access to a range of treatment pathways, and the impact of patient, tumour and provider characteristics on access to treatments.

Data used will be: patients diagnosed with lung cancer (1st April 2014 to 31st March 2015) who were eligible for chemotherapy; information about their tumour, chemotherapy treatment received, and demographic information.

Understanding variation in accessing treatments will inform policy makers and commissioners regarding where efforts should be focused, to ensure equitable access to effective treatments for NSCLC, and improve patient outcomes.

The linked data will be used to calculate access rates for different treatments, and then statistical tests will measure the overall geographic variation and significance. Finally, logistic regression will identify which factors are predictive of whether people receive various treatments (e.g. age, deprivation, ethnicity).

Findings are due early 2019: we expect to establish the presence of variation at a geographic level, and the reaso

In England, less than 60% of eligible bowel cancer screening participants take part in the programme. Cancer Research UK, in partnership with Public Health England, carried out a regional Be Clear on Cancer pilot campaign in the North West of England to encourage participation.

The campaign ran in 33 CCGs and consisted of advertising (including TV) and direct mail. Advertising ran alone for 6 weeks and was later combined for 6 weeks with direct mail in 22 CCGs to first-timers and previous non-responders. The remaining 11 CCGs continued to receive advertising only. The campaign was aimed at people aged 55-74 in the lower socioeconomic groups (C2DE) and skewed towards men; this was based on pilots previously run by Cancer Research UK.

We evaluated whether the campaign advertising, or advertising paired with sending a CRUK-endorsement letter with the kit increased uptake. Differences have also been compared across different socioeconomic groups.

The data we used to do this were extracted from the national bowel cancer screening database. We used age, location, date of test kit received, and date kit sent back. For the direct mail element of the campaign, we obtained a set of data for bowel screening test kit recipients who received a CRUK-endorsement letter, and a separate set of data for bowel screening test kit recipients who did not. We did not receive any names, addresses, or NHS numbers, so no individuals could be identified.

We split participants into 3 groups for the evaluation:

- First timers – people who are invited for bowel screening for the first time

- Previously screened – those who were invited for screening previously and returned completed kits

- Previous non-responders – those who were invited previously but didn’t return completed kits

Results are promising. They showed an increase in uptake of the screening test kit during the live campaign for all groups, as well as a smaller sustained increase in the 3 months following the campaign.

There are upcoming changes to the bowel cancer screening programme which may impact on screening uptake. We recommend waiting for an appropriate time, once changes have been implemented, to consider another campaign.

See also: Definitions of socioeconomic groups , Previous pilots .

COVID RT – assessing the impact of COVID-19 on radiotherapy in the UK

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on cancer patients and cancer services across the UK. During the peak of the pandemic, radiotherapy services across the UK continued to treat cancer patients in often challenging circumstances and implemented significant changes to standard practice to minimise the risks to patients of contracting COVID-19 and focus radiotherapy resources where they were most needed. The scale of these changes in radiotherapy practice, the clinical decision-making underpinning them and their impact on cancer patient outcomes is unknown. This study will give a national picture of the decision making by patients and clinical staff and the impact on patient's treatment. It also provides knowledge of how RT was used as a bridge to surgery when surgical services weren't viable due to the pandemic and therefore what are the further requirements for cohorts of patients.