You are using an outdated browser no longer supported by Oyez. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits states from segregating public school students on the basis of race. This marked a reversal of the "separate but equal" doctrine from Plessy v. Ferguson that had permitted separate schools for white and colored children provided that the facilities were equal.

Based on an 1879 law, the Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas operated separate elementary schools for white and African-American students in communities with more than 15,000 residents. The NAACP in Topeka sought to challenge this policy of segregation and recruited 13 Topeka parents to challenge the law on behalf of 20 children. In 1951, each of the families attempted to enroll the children in the school closest to them, which were schools designated for whites. Each child was refused admission and directed to the African-American schools, which were much further from where they lived. For example, Linda Brown, the daughter of the named plaintiff, could have attended a white school several blocks from her house but instead was required to walk some distance to a bus stop and then take the bus for a mile to an African-American school. Once the children had been refused admission to the schools designated for whites, the NAACP brought the lawsuit. They were unsuccessful at the trial court level, where the 1896 Supreme Court precedent in Plessy v. Ferguson was found to be decisive. Even though the trial court agreed that educational segregation had a negative effect on African-American children, it applied the standard of Plessy in finding that the white and African-American schools offered sufficiently equal quality of teachers, curricula, facilities, and transportation. Since the NAACP did not challenge the details of those findings, it essentially cast the appeal as a direct challenge to the system imposed by Plessy. When the Supreme Court heard the appeal, it combined Brown with four other cases addressing parallel issues in South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and Washington, D.C. The NAACP was responsible for bringing each of these lawsuits, and it had lost on each of them at the trial court level except the Delaware case of Gebhart v. Belton. Brown stood apart from the others in the group as the only case that challenged the separate but equal doctrine on its face. The others were based on assertions of gross inequality, which would have violated the standard in Plessy as well.

- Earl Warren (Author)

- Hugo Lafayette Black

- Stanley Forman Reed

- Felix Frankfurter

- William Orville Douglas

- Robert Houghwout Jackson

- Harold Hitz Burton

- Tom C. Clark

- Sherman Minton

Supreme Court opinions are rarely unanimous, and it appears that Justice Frankfurter deliberately argued for a re-hearing to stall the case while the Court built a consensus behind its decision. This was designed to prevent proponents of segregation from using dissents to build future challenges to Brown. Despite the eventual unanimity, the judges had a wide range of views. Reed and Clark were not opposed to segregation per se, while Frankfurter and Jackson were hesitant to issue a bold decision that might be difficult to enforce. (Jackson and Reed initially planned to write a dissent together.) Douglas, Black, Burton, and Minton were relatively ready to overturn Plessy from the outset, however, as was Chief Justice Warren. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's appointment of Warren to replace former Chief Justice Frederick Moore Vinson, who died in September 1953, thus may have played a crucial role in how events unfolded. Warren had supported the integration of Mexican-American children into California schools. Warren based much of his opinion on information from social science studies rather than court precedent. This was understandable because few decisions existed on which the Court could rely, yet it would draw criticism for its non-traditional approach. The decision also used language that was relatively accessible to non-lawyers because Warren felt that it was necessary for all Americans to understand its logic.

This decision ranks among the most dramatic issued by the Supreme Court, in part due to Warren's insistence that the Fourteenth Amendment gave the Court the power to end segregation even without Congressional authority. Like the use of non-legal sources to justify his reasoning, Warren's "activist" view of the Court's role remains controversial to the current day. The illegality of segregation does not, however, and a series of later decisions were implemented to try to force states to comply with Brown. Unfortunately, the reality is that this decision's vision of complete desegregation has not been achieved in many areas of the U.S., and the problems of enforcement that Jackson identified have proven difficult to solve.

U.S. Supreme Court

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Argued December 9, 1952

Reargued December 8, 1953

Decided May 17, 1954*

Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment -- even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors of white and Negro schools may be equal. Pp. 486-496.

(a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education. Pp. 489-490.

(b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Pp. 492-493.

(c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms. P. 493.

(d) Segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal. Pp. 493-494.

(e) The "separate but equal" doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , has no place in the field of public education. P. 495.

(f) The cases are restored to the docket for further argument on specified questions relating to the forms of the decrees. Pp. 495-496.

- Opinions & Dissents

- Copy Citation

Get free summaries of new US Supreme Court opinions delivered to your inbox!

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

Some case metadata and case summaries were written with the help of AI, which can produce inaccuracies. You should read the full case before relying on it for legal research purposes.

Help inform the discussion

Brown v. Board of Education

May 17, 1954: The 'separate is inherently unequal' ruling forces Eisenhower to address civil rights

Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. . . . We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.

In 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote this opinion in the unanimous Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. Citing a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, the groundbreaking decision was widely regarded as one of America's most consequential legal judgments of the 20th century, setting the stage for a strong and lasting US Civil Rights Movement. Thurgood Marshall, lead counsel on the case, would go on to become a Supreme Court Justice himself.

The Brown decision reverberated for decades. Determined resistance by whites in the South thwarted the goal of school integration for years. Even though the court ruled that states should move with “all deliberate speed,” that standard was simply too vague for real action. Neither segregationists, who opposed to integration on racist grounds, nor the constitutional scholars who believed the court had overreached were going away without a fight.

President Eisenhower didn't fully support of the Brown decision. The president didn't like dealing with racial issues and failed to speak out in favor of the court's ruling. Although the president usually avoided comment on court decisions, his silence in this case may have encouraged resistance. In many parts of the South, white citizens' councils organized to prevent compliance. Some of these groups relied on political action; others used intimidation and violence.

Despite his reticence, Eisenhower did acknowledge his constitutional responsibility to uphold the Supreme Court’s rulings. In 1957, when mobs prevented the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, Governor Orval Faubus saw political advantages in using the National Guard to block the entry of African American students to Central High. After meeting with Eisenhower, Faubus promised to allow the students to enroll—but then withdrew the National Guard, allowing a violent mob to surround the school. In response, Eisenhower dispatched federal troops, the first time since Reconstruction that a president had sent military forces into the South to enforce federal law.

In explaining his action, however, Eisenhower did not declare that desegregating public schools was the right thing to do. Instead, in a nationally televised address , he asserted that the violence in Little Rock was harming US prestige and influence around the world and giving Communist propagandists an opportunity “to misrepresent our whole nation.” Troops stayed in Little Rock for the entire school year, and in the spring of 1958, Central High had its first African American graduate.

But in September 1958, Faubus closed public schools to prevent their integration. Eisenhower expressed his “regret” over the challenge to the right of all Americans to a public education but took no further action, despite what he had done the year before. There was no violence this time, and Eisenhower believed that he had a constitutional obligation to preserve public order, not to speed school desegregation. When Eisenhower left the White House in January 1961, only 6 percent of African American students attended integrated schools.

Eisenhower and integration

Eisenhower urged advocates of desegregation to go slowly. believing that integration required a change in people's hearts and minds. And he was sympathetic to white southerners who complained about alterations to the social order—their “way of life.” He considered as extremists both those who tried to obstruct decisions of federal courts and those who demanded that they immediately enjoy the rights that the Constitution and the courts provided them.

On only one occasion during his presidency—in June 1958—did Eisenhower meet with African American leaders. The president became irritated when he heard appeals for more aggressive federal action to advance civil rights and failed to heed Martin Luther King Jr.’s advice that he use the bully pulpit of the presidency to build popular support for racial integration. While Eisenhower’s actions mattered, so too did his failure to use his moral authority as president to advance the cause of civil rights.

Eisenhower's record, however, included some significant achievements in civil rights. In 1957, he signed the first civil rights legislation since Reconstruction, providing new federal protections for voting rights. In most southern states, the great majority of African Americans simply could not vote because of literacy tests, poll taxes, and other obstacles. Yet the legislation Eisenhower eventually signed was weaker than the bill that he had sent to Capitol Hill. Southern Democrats secured an amendment that required a jury trial to determine whether a citizen had been denied his or her right to vote—and African Americans could not serve on juries in the south. In 1960, Eisenhower signed a second civil rights law, but it offered only small improvements. The president also used his constitutional powers, where he believed that they were clear and specific, to advance desegregation, for example, in federal facilities in the nation's capital and to complete the desegregation of the armed forces begun during Truman’s presidency. In addition, Eisenhower appointed judges to federal courts whose rulings helped to advance civil rights. This issue, which divided the country in the 1950s, became even more difficult in the 1960s.

The attorney: Thurgood Marshall

NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall argued Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court, and during a quarter-century with the organization, he won a total of 29 cases before the nation's highest court. In 1961, Marshall was appointed to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit by President Kennedy, and in 1965, he became the highest-ranking African American government official in history when President Johnson appointed him solicitor general. Now arguing on behalf of the federal government before the court—Marshall won the majority of those cases as well. In 1967, Johnson nominated Marshall to sit on the court, discussing him with Attorney General Ramsey Clark in a conversation captured on the Miller Center's collection of secret White House tapes:

Featured Video

Eisenhower on integration.

President Eisenhower addresses school integration after the Little Rock Nine.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

Primary tabs.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954) was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down the “Separate but Equal” doctrine and outlawed the ongoing segregation in schools. The court ruled that laws mandating and enforcing racial segregation in public schools were unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools were “separate but equal” in standards. The Supreme Court’s decision was unanimous and felt that " separate educational facilities are inherently unequal ," and hence a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution . Nonetheless, since the ruling did not list or specify a particular method or way of how to proceed in ending racial segregation in schools, the Court's ruling i n Brown II (1955) demanded states to desegregate “ with all deliberate speed .”

Background :

The events relevant to this specific case first occurred in 1951, when a public school district in Topeka, Kansas refused to let Oliver Brown’s daughter enroll at the nearest school to their home and instead required her to enroll at a school further away. Oliver Brown and his daughter were black. The Brown family, along with twelve other local black families in similar circumstances, filed a class action lawsuit against the Topeka Board of Education in a federal court arguing that the segregation policy of forcing black students to attend separate schools was unconstitutional. However, the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas ruled against the Browns, justifying their decision on judicial precedent of the Supreme Court's 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson , which ruled that racial segregation did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment 's Equal Protection Clause as long as the facilities and situations were equal, hence the doctrine known as " separate but equal ." After this decision from the District Court in Kansas, the Browns, who were represented by the then NAACP chief counsel Thurgood Marshall, appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's ruling in Brown overruled Plessy v. Ferguson by holding that the "separate but equal" doctrine was unconstitutional for American educational facilities and public schools. This decision led to more integration in other areas and was seen as major victory for the Civil Rights Movement. Many future litigation cases used the similar argumentation methods used by Marshall in this case. While this was seen as a landmark decision, many in the American Deep South were uncomfortable with this decision. Various Southern politicians tried to actively resist or delay attempts to desegregated their schools. These collective efforts were known as the “ Massive Resistance ,” which was started by Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd. Thus, in just four years after the Supreme Court’s ruling, the Supreme Court affirmed its ruling again in the case of Cooper v. Aaron , holding that government officials had no power to ignore the ruling or to frustrate and delay desegregation.

[Last updated in July of 2022 by the Wex Definitions Team ]

- ACADEMIC TOPICS

- legal history

- civil rights

- education law

- THE LEGAL PROCESS

- legal practice/ethics

- group rights

- legal education and practice

- wex articles

- wex definitions

National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Exhibitions

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

Brown v. Board of Education 70th Anniversary

The National Museum of African American History and Culture marks the anniversary of a landmark United States Supreme Court decision that profoundly impacted access to education, resulting in a major step toward equality and justice for African Americans.

“No More Segregated Education,” print of 1964 photograph by Frank Espada. Collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture purchased with funds provided by the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center. Copyright Estate of Frank Espada

The Road to Brown

![brown v board of education A metal double-sided black railroad sign that reads: [WAITING ROOM / FOR WHITES / ONLY / BY ORDER OF / POLICE DEPT.] in white paint. The writing is on a framed square plaque at the top of the sign. The sign post is round and has metal work at the top where the plaque meets the post and that the bottom where the post meets the base. The base is round. There is orange paint that is visible in spots where the black paint has peeled. There is also rust on the bottom of the base.](https://nmaahc.si.edu/sites/default/files/styles/max_1300x1300/public/2024-03/NMAAHC-2E1AF3B4866D2_5001.jpeg?itok=ycYqay6E)

Sign from segregated railroad station

In 1892 Homer Plessy of New Orleans, Louisiana, volunteered to test the legality of railroad car segregation in that state. He sat in a “whites only” car, refused to move to a segregated car, was arrested, and sued in court. The case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 1896 that segregation was legal as long as the accommodations were “separate but equal.”

The 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision further reinforced the rise of segregation. The Court rendered this decision despite the reality that separate areas provided for African Americans rarely were equal. John Marshall Harlan, the only dissenting justice, argued against the decision: “The arbitrary separation of citizens, on the basis of race … is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution.”

Despite the refusal of the courts or politicians to support them, African Americans continued to challenge segregation and demand their equal rights under the Constitution. They pressed forward their fight in the belief that their efforts might eventually result in change.

The arbitrary separation of citizens, on the basis of race…is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution. John Marshall Harlan U.S. Supreme Court Justice

The Struggle Against Segregated Education

In their own words.

Hear directly from those who participated in the Brown v. Board of Education case from our Oral History Initiative .

We use the video player Able Player to provide captions and audio descriptions. Able Player performs best using web browsers Google Chrome, Firefox, and Edge. If you are using Safari as your browser, use the play button to continue the video after each audio description. We apologize for the inconvenience.

Robert Carter

Matthew Perry

Mildred Bond Roxborough

The Decision

Baby dolls used by Northside Center for Child Development, 1968.

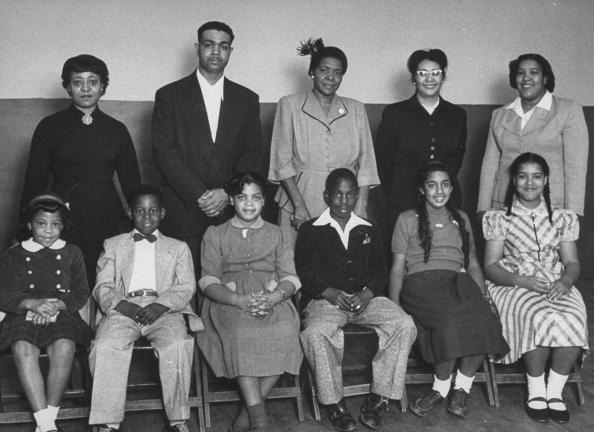

"Separate but equal" remained standard doctrine in U.S. law until the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, in which the Court ruled that segregation in public education was unconstitutional. The case began in 1951 as a class action suit filed in the United States District Court for the District of Kansas that called on the city's Board of Education to reverse its policy of racial segregation. It was initiated by the Topeka chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) , and the plaintiffs were 13 African American parents on behalf of their children. The named plaintiff was Oliver L. Brown, a welder and an assistant pastor at his local church, whose daughter had to walk six blocks to her school bus stop to ride to her segregated black school one mile away, while a white school was located just seven blocks from her house.

On May 17, 1954, the Court handed down its unanimous 9-0 decision overturning Plessy as it applied to public education, stating that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." As a result, racial segregation laws were declared in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, paving the way for integration and winning a major victory for the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement.

Two Landmark Decisions in the Fight for Equality and Justice

James Oscar Jones

Cecilia Suyat Marshall

Kathleen Cleaver

Aftermath & Legacy

Diploma for Carlotta Walls from Little Rock Central High School, 1960.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Carlotta Walls LaNier

In 1954 the United States Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were illegal. The case, Brown v. The Board of Education, has become iconic for Americans because it marked the formal beginning of the end of segregation.

But the gears of change grind slowly. It wasn't until September 1957 when nine teens would become symbols, much like the landmark decision we know as Brown v. The Board of Education, of all that was in store for our nation in the years to come.

The Little Rock Nine

Cecil Williams

Jack Greenberg

Glenda Funchess

Upcoming Event

Celebrating the past, shaping the future: 70th anniversary of brown v. board of education.

Friday, May 17, 2024 10:00am - 5:00pm Oprah Winfrey Theater

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

The Supreme Court Decision That Changed America: Brown v. Board of Education

Finally, the justices overturned jim crow, tossing out ‘separate but equal’ standard.

On December 13, 1952, the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court met to consider five cases they had heard argued earlier that week. Those cases raised the most explosive topic any of the jurists would ever have to rule on: whether the Constitution allowed American public school districts to continue to use racial criteria to segregate facilities. Opening the discussion, Chief Justice Fred Vinson admitted, “The situation is very serious and very emotional.”

This was no theoretical matter. In the South, 17 states required public schools to separate students by race, and Kansas, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Arizona permitted school segregation by law. But the country had begun to rethink segregation. In 1947, California had repealed a law mandating separate schools for Asians. The next year, President Harry Truman issued an executive order ending racial segregation in the armed forces and Arkansas desegregated its state university.

The justices had long relied on predecessors’ 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson , which said that it was not a violation of the guarantee of equal protection of the law to consign people of different races—for which read Whites and others—to separate facilities, provided those facilities were equal. But the justices had begun to take baby steps away from the court’s historic pattern of defending school segregation. In the mid-1930s civil rights activists had begun litigating the question of whether educational facilities assigned blacks were in fact equal. These efforts led initally to cases that involved graduate education—not nearly as hot-button a topic as integrating primary and secondary schools would have been.

That tactic generated the first Supreme Court ruling against racial segregation in education. The 1938 decision found that Missouri was not giving equal treatment—and therefore was violating the Constitution—when the state university law school refused to admit a qualified African American, even though the institution offered to pay his tuition at a law school in an adjacent state. In 1950 the court held unconstitutional the Texas policy of maintaining separate, racially segregated law schools, because not only did the school for Whites boast a greater variety of courses and a better library but also enjoyed a superior reputation and “standing in the community.” The same day, the justices embraced an even broader reading of “equal” by holding unconstitutional a University of Oklahoma policy forcing a Black doctoral candidate to sit at a separate table when in a classroom, library, or cafeteria.

The justices knew that any ruling on segregation in grades K-12 would detonate in ways that decisions on post-baccalaureate education did not. So incendiary was the prospect that at that December 1952 meeting the justices decided not to rule on the issue. Without a formal vote, they set the five cases for rehearing in 1953. However, discussion revealed that four justices were ready to ban racial school segregation and four others found the Constitution to permit school segregation, while one—Felix Frankfurter—would ban segregation only in Washington, DC.

Three months before the cases were to be argued again, Chief Justice Vinson died of a heart attack. President Dwight Eisenhower gave California Governor Earl Warren an interim appointment to the Court, allowing him to step immediately into the role of chief justice in time to hear the desegregation cases; Warren’s Senate confirmation, by acclamation, came five months later.

Vinson had favored segregation, infusing Warren’s appointment with huge impact. As governor Warren had spurred California’s repeal of its law dictating separate schools for Asians, and as a justice he could be counted as a fifth vote against segregation, making a majority.

But Warren wanted the Supreme Court to strike down school segregation with a unified voice. He opened the conference after the 1953 re-arguments by saying, “There is great value in unanimity and uniformity, even if we have some differences.” He painted the question of continuing segregation as a moral one, precedent be damned.

“The basis of the principle of segregation and separate but equal rests upon the basic premise that the Negro race is inferior,” Warren told colleagues. “I don’t see how we can continue in this day and age to set one group apart from the rest and say that that they are not entitled to exactly the same treatment as all others.”

Warren’s reasoning closely reflected the oral argument the lead lawyer for the students pressing for integrated schools had made to the court. The NAACP’s Thurgood Marshall, later the Supreme Court’s first African-American member, had told the justices that if they found continued school segregation allowable “the only way to arrive at this decision is to find that for some reason Negroes are inferior to all other human beings.”

Not every justice agreed. “Segregation is not done on the theory of racial inferiority, but of racial differences,” Stanley Reed, the most adamant resister, argued to his colleagues. “It protects people against the mixing of races.” But Warren was able to convince Reed and the other dissenters that, since a majority was going to hand down a contentious ruling deeming school segregation unconstitutional, it would be best for the nation if there were no public disagreement.

That call for unanimity was so compelling that when the decision came on May 17, 1954, Justice Robert H. Jackson left his hospital bed to be with his colleagues in the courtroom.

To underline the ruling’s national nature and make clear that it was not a regional jab at the South, the High Court cited as the first case one brought on behalf of Kansas schoolgirl Linda Brown. Local authorities had barred her from attending her neighborhood elementary; thus the historic title Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka .

Warren wrote the opinion, a mere 13 paragraphs long and devoid of Latinate legalisms. The issue could no longer be whether educational opportunities being offered Black and White students in segregated schools were equal—in the cases before the court, facilities and programs were in fact equal or making significant strides in that direction—but whether separation itself violated the 14th Amendment promise of equal protection under the law. Warren insisted that school segregation by its nature was unequal, inflicting particular harm on children: “To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way that is unlikely ever to be undone.” As evidence, Warren unconventionally cited not legal precedent but results of seven sociological and psychological studies showing that Negro children in segregated schools did in fact feel that blacks were inferior.

Warren’s decision acknowledged “a great variety of local conditions” and asked the litigants to recommend how to achieve integration. In May 1955 the chief justice announced the High Court’s second Brown decision, calling for school desegregation to proceed “with all deliberate speed” but telling lower courts overseeing compliance to recognize that they “may find that additional time is necessary to carry out the ruling.”

Change began. However, so many localities resisted that integration was still being fought in 1970. That year President Richard Nixon, declaring Brown “right in both constitutional and human terms,” created a Cabinet-level committee to put federal muscle behind its mandate. But Brown did generate one immediate impact. As lawyer-journalist-professor Roger Wilkins phrased it, the decision was a ringing rebuke to a cultural smear that African Americans had had to grow up with—that they were inherently inferior.

“For me, May 17, 1954 was a second Emancipation Day,” Wilkins declared.

This SCOTUS 101 column appeared in the April 2021 issue of American History

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

Western Writers of America Announces Its 2024 Wister Award Winner

Historian Quintard Taylor has devoted his career to retracing the black experience out West.

How Saladin Became A Successful War Leader

How Saladin, Egypt’s first Sultan, unified his allies and won the admiration of his foes.

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

1954: brown v. board of education.

On May 17, 1954, in a landmark decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the U.S. Supreme Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for students of different races to be unconstitutional. The decision dismantled the legal framework for racial segregation in public schools and Jim Crow laws, which limited the rights of African Americans, particularly in the South.

Segregation in Schools

Naacp challenges segregation in court, separate, but equal has 'no place', brown v board quick facts.

What is it? A landmark Supreme Court case.

Significance: Ended 'Separate, but equal,' desegregated public schools.

Date: May 17, 1954

Associated Sites: Brown v Board of Education National Historic Site; US Supreme Court Building

You Might Also Like

- brown v. board of education national historical park

- little rock central high school national historic site

- civil rights

- civil rights movement

- desegregation

- african american history

- brown v. the board of education of topeka

- public education

Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park , Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site

Last updated: July 12, 2023

- Asian Pacific American History

- Women's History

- Collections

Separate is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education Homepage

Get Resource

Separate Is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education , an online exhibition, will help students understand an historic struggle to fulfill the American dream that set in motion sweeping changes in American society, and redefined the nation's ideals. The U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education marked a turning point in the history of race relations in the United States. On May 17, 1954, the Court stripped away constitutional sanctions for segregation by race, and made equal opportunity in education the law of the land. Brown v. Board of Education reached the Supreme Court through the fearless efforts of lawyers, community activists, parents, and students.

Related Educational Resources

Preparing for the Oath: Courts

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Brown v. Board of Education: The First Step in the Desegregation of America’s Schools

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: September 7, 2023 | Original: May 16, 2018

On May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren issued the Supreme Court ’s unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education , ruling that racial segregation in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment . The upshot: Students of color in America would no longer be forced by law to attend traditionally under-resourced Black-only schools.

The decision marked a legal turning point for the American civil-rights movement . But it would take much more than a decree from the nation’s highest court to change hearts, minds and two centuries of entrenched racism. Brown was initially met with inertia and, in most southern states, active resistance. More than half a century later, progress has been made, but the vision of Warren’s court has not been fully realized.

The Supreme Court Rules 'Separate' Means Unequal

The landmark case began as five separate class-action lawsuits brought by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on behalf of Black schoolchildren and their families in Kansas , South Carolina , Delaware , Virginia and Washington, D.C . The lead plaintiff, Oliver Brown, had filed suit against the Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas in 1951, after his daughter Linda was denied admission to a white elementary school.

Her all-Black school, Monroe Elementary, was fortunate—and unique—to be endowed with well-kept facilities, well-trained teachers and adequate materials. But the other four lawsuits embedded in the Brown case pointed to more common fundamental challenges. The case in Clarendon, South Carolina described school buildings as no more than dilapidated wooden shacks. In Prince Edward County, Virginia, the high school had no cafeteria, gym, nurse’s office or teachers’ restrooms, and overcrowding led to students being housed in an old school bus and tar-paper shacks.

Brown v. Board First to Rule Against Segregation Since Reconstruction Era

The Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board marked a shining moment in the NAACP’s decades-long campaign to combat school segregation. In declaring school segregation as unconstitutional, the Court overturned the longstanding “separate but equal” doctrine established nearly 60 years earlier in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In his opinion, Chief Justice Warren asserted public education was an essential right that deserved equal protection, stating unequivocally that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Still, Thurgood Marshall , head of the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund and lead lawyer from the plaintiffs, knew the fight was far from over—and that the high court’s decision was only a first step in the long, complicated process of dismantling institutionalized racism. He warned his colleagues soon after the verdict came down: “The fight has just begun.”

In 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously strikes down segregation in public schools, sparking the Civil Rights movement.

Brown v. Board Does Not Instantly Desegregate Schools

In its landmark ruling, the Supreme Court didn’t specify exactly how to end school segregation, but rather asked to hear further arguments on the issue. The Court’s timidity, combined with steadfast local resistance, meant that the bold Brown v. Board of Education ruling did little on the community level to achieve the goal of desegregation. Black students, to a large degree, still attended schools with substandard facilities, out-of-date textbooks and often no basic school supplies.

In a 1955 case known as Brown v. Board II , the Court gave much of the responsibility for the implementation of desegregation to local school authorities and lower courts, urging that the process proceed “with all deliberate speed.” But many lower court judges in the South, who had been appointed by segregationist politicians, were emboldened to resist desegregation by the Court’s lackluster enforcement of the Brown decision.

In Prince Edward County, where one of the five class-action suits behind Brown was filed, the Board of Supervisors refused to appropriate funds for the County School Board, choosing to shut down the public schools for five years rather than integrate them.

This backlash against the Court’s verdict reached the highest levels of government: In 1956, 82 representatives and 19 senators endorsed a so-called “Southern Manifesto” in Congress, urging Southerners to use all “lawful means” at their disposal to resist the “chaos and confusion” that school desegregation would cause.

In 1964, a full decade after the decision, more than 98 percent of Black children in the South still attended segregated schools .

The Brown Ruling Becomes a Catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement

For the first time since the Reconstruction Era , the Court’s ruling focused national attention on the subjugation of Black Americans. The result? The growth of the nascent civil-rights movement, which would doggedly challenge segregation and demand legal equality for Black families through boycotts, sit-ins, freedom rides and voter-registration drives.

The Brown verdict inspired Southern Blacks to defy restrictive and punitive Jim Crow laws, however, the ruling also galvanized Southern whites in defense of segregation—including the infamous standoff at a high school in Little Rock , Arkansas in 1957. Violence against civil-rights activists escalated, outraging many in the North and abroad, helping to speed up the passage of major civil-rights and voting-rights legislation by the mid-1960s.

Finally, in 1964, two provisions within the Civil Rights Act effectively gave the federal government the power to enforce school desegregation for the first time: The Justice Department could sue schools that refused to integrate, and the government could withhold funding from segregated schools. Within five years after the act took effect, nearly a third of Black children in the South attended integrated schools, and that figure reached as high as 90 percent by 1973.

Legacy and Impact of Brown v. Board

More than 60 years after the landmark ruling, assessing its impact remains a complicated endeavor. The Court’s verdict fell short of initial hopes that it would end school segregation in America for good, and some argued that larger social and political forces within the nation played a far greater role in ending segregation.

As the Supreme Court has grown increasingly polarized along political lines, both conservative and liberal justices have claimed the legacy of Brown v. Board to argue different sides in the constitutional debate. In 2007, the Court ruled 5-4 against allowing public schools to take race into account in their admission policies in order to achieve or maintain integration.

Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, asserted: “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” And in a dissenting opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote that the ruling “rewrites the history of one of this court’s most important decisions.”

Are Schools 'Separate But Equal’ in the 21st Century?

School segregation remains in force all over America today, largely because many of the neighborhoods in which schools are still located are themselves segregated. Despite the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 and later judicial decisions making racial discrimination illegal, exclusionary economic-zoning laws still bar low-income and working-class Americans from many neighborhoods, which in many cases reduces their access to higher quality schools.

According to a 2014 report by Richard Rothstein of the Economic Policy Institute report , as of the 60th anniversary of the Brown v. Board verdict the typical Black student attended a school where only 29 percent of his or her fellow students were white, down from some 36 percent in 1980.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Brown v. Board of Education: Annotated

The 1954 Supreme Court decision, based on the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, declared that “separate but equal” has no place in education.

The US Supreme Court’s decision in the case known colloquially as Brown v. Board of Education found that the “[t]he ‘separate but equal ’ doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537, has no place in the field of public education.” The Plessy case, decided in 1896, had found that the segregation laws which created “separate but equal” accommodations for Black Americans, specific to transportation but applicable generally, were not a violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. Segregation in education had been challenged throughout the first half of the twentieth century, and rulings in a number coalesced to propel Brown to the level of the Supreme Court to address segregation in all public schools.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Below is an annotation of the opinion, with relevant scholarship covering the legal, social and education history leading up to and after the decision. As always, the supporting research is free to read and download.

The red J indicates free access to the linked research on JSTOR . ____________________________________________________________________________

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 US 483 (1954) (USSC+)

Argued December 9, 1952

Reargued December 8, 1953

Decided May 17, 1954

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS*

Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment —even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors of white and Negro schools may be equal.

(a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education.

(b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation.

(c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.

(d) Segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities , even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors may be equal.

(e) The “separate but equal” doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537, has no place in the field of public education.

(f) The cases are restored to the docket for further argument on specified questions relating to the forms of the decrees.

MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court.

These cases come to us from the States of Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. They are premised on different facts and different local conditions, but a common legal question justifies their consideration together in this consolidated opinion.

In each of the cases, minors of the Negro race, through their legal representatives, seek the aid of the courts in obtaining admission to the public schools of their community on a nonsegregated basis. In each instance, they had been denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws requiring or permitting segregation according to race. This segregation was alleged to deprive the plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. In each of the cases other than the Delaware case, a three-judge federal district court denied relief to the plaintiffs on the so-called “separate but equal” doctrine announced by this Court in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537 . Under that doctrine, equality of treatment is accorded when the races are provided substantially equal facilities, even though these facilities be separate. In the Delaware case , the Supreme Court of Delaware adhered to that doctrine, but ordered that the plaintiffs be admitted to the white schools because of their superiority to the Negro schools.

The plaintiffs contend that segregated public schools are not “equal” and cannot be made “equal,” and that hence they are deprived of the equal protection of the laws. Because of the obvious importance of the question presented, the Court took jurisdiction. Argument was heard in the 1952 Term, and reargument was heard this Term on certain questions propounded by the Court.

Reargument was largely devoted to the circumstances surrounding the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. It covered exhaustively consideration of the Amendment in Congress, ratification by the states, then-existing practices in racial segregation, and the views of proponents and opponents of the Amendment. This discussion and our own investigation convince us that, although these sources cast some light, it is not enough to resolve the problem with which we are faced. At best, they are inconclusive. The most avid proponents of the post-War Amendments undoubtedly intended them to remove all legal distinctions among “all persons born or naturalized in the United States.” Their opponents, just as certainly, were antagonistic to both the letter and the spirit of the Amendments and wished them to have the most limited effect. What others in Congress and the state legislatures had in mind cannot be determined with any degree of certainty.

An additional reason for the inconclusive nature of the Amendment’s history with respect to segregated schools is the status of public education at that time. In the South, the movement toward free common schools, supported by general taxation, had not yet taken hold . Education of white children was largely in the hands of private groups. Education of Negroes was almost nonexistent, and practically all of the race were illiterate. In fact, any education of Negroes was forbidden by law in some states. Today, in contrast, many Negroes have achieved outstanding success in the arts and sciences, as well as in the business and professional world. It is true that public school education at the time of the Amendment had advanced further in the North, but the effect of the Amendment on Northern States was generally ignored in the congressional debates. Even in the North, the conditions of public education did not approximate those existing today. The curriculum was usually rudimentary; ungraded schools were common in rural areas; the school term was but three months a year in many states, and compulsory school attendance was virtually unknown. As a consequence, it is not surprising that there should be so little in the history of the Fourteenth Amendment relating to its intended effect on public education.

In the first cases in this Court construing the Fourteenth Amendment, decided shortly after its adoption, the Court interpreted it as proscribing all state-imposed discriminations against the Negro race. The doctrine of “separate but equal” did not make its appearance in this Court until 1896 in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson , supra, involving not education but transportation. American courts have since labored with the doctrine for over half a century. In this Court, there have been six cases involving the “separate but equal” doctrine in the field of public education. In Cumming v. County Board of Education , 175 US 528 , and Gong Lum v. Rice , 275 US 78 , the validity of the doctrine itself was not challenged. In more recent cases, all on the graduate school level, inequality was found in that specific benefits enjoyed by white students were denied to Negro students of the same educational qualifications. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada , 305 US 337 ; Sipuel v. Oklahoma , 332 US 631; Sweatt v. Painter , 339 US 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents , 339 US 637 . In none of these cases was it necessary to reexamine the doctrine to grant relief to the Negro plaintiff. And in Sweatt v. Painter , supra, the Court expressly reserved decision on the question whether Plessy v. Ferguson should be held inapplicable to public education.

In the instant cases, that question is directly presented. Here, unlike Sweatt v. Painter , there are findings below that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers, and other “tangible” factors. Our decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases. We must look instead to the effect of segregation itself on public education.

In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the clock back to 1868, when the Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896, when Plessy v. Ferguson was written. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.

Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship . Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.

We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race , even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does.

In Sweatt v. Painter , supra, in finding that a segregated law school for Negroes could not provide them equal educational opportunities, this Court relied in large part on “those qualities which are incapable of objective measurement but which make for greatness in a law school.” In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents , supra, the Court, in requiring that a Negro admitted to a white graduate school be treated like all other students, again resorted to intangible considerations: “…his ability to study, to engage in discussions and exchange views with other students, and, in general, to learn his profession.” Such considerations apply with added force to children in grade and high schools. To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of this separation on their educational opportunities was well stated by a finding in the Kansas case by a court which nevertheless felt compelled to rule against the Negro plaintiffs:

Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law , for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial[ly] integrated school system .

Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson , this finding is amply supported by modern authority. Any language in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this finding is rejected.

We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal . Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. This disposition makes unnecessary any discussion whether such segregation also violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Because these are class actions, because of the wide applicability of this decision, and because of the great variety of local conditions, the formulation of decrees in these cases presents problems of considerable complexity . On reargument, the consideration of appropriate relief was necessarily subordinated to the primary question—the constitutionality of segregation in public education. We have now announced that such segregation is a denial of the equal protection of the laws. In order that we may have the full assistance of the parties in formulating decrees, the cases will be restored to the docket, and the parties are requested to present further argument on Questions 4 and 5 previously propounded by the Court for the reargument this Term The Attorney General of the United States is again invited to participate. The Attorneys General of the states requiring or permitting segregation in public education will also be permitted to appear as amici curiae upon request to do so by September 15, 1954, and submission of briefs by October 1, 1954.

It is so ordered.

* Together with No. 2, Briggs et al. v. Elliott et al. , on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, argued December 9–10, 1952, reargued December 7–8, 1953; No. 4, Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al. , on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, argued December 10, 1952, reargued December 7–8, 1953, and No. 10, Gebhart et al. v. Belton et al. , on certiorari to the Supreme Court of Delaware, argued December 11, 1952, reargued December 9, 1953.

[Transcript available from the National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/brown-v-board-of-education ]

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Before Palmer Penmanship

- Archival Adventures in the Abernethy Collection

- Elephant Executions

Time in a Box

Recent posts.

- Nightclubs, Fungus, and Curbing Gun Violence

- Scaffolding a Research Project with JSTOR

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Skip to main navigation

- Email Updates

- Federal Court Finder

History - Brown v. Board of Education Re-enactment

The plessy decision.

In 1892, an African American man named Homer Plessy refused to give up his seat to a white man on a train in New Orleans, as he was required to do by Louisiana state law. Plessy was arrested and decided to contest the arrest in court. He contended that the Louisiana law separating Black people from white people on trains violated the "equal protection clause" of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. By 1896, his case had made it all the way to the United States Supreme Court. By a vote of 8-1, the Supreme Court ruled against Plessy . In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson , Justice Henry Billings Brown, writing the majority opinion, stated that:

"The object of the [Fourteenth] amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to endorse social, as distinguished from political, equality. . . If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane."

The lone dissenter, Justice John Marshal Harlan, interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment another way, stated, "Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." Justice Harlan's dissent would become a rallying cry for those in later generations working to declare segregation unconstitutional.

The Road to Brown

(Note: Some of the case information is from Patterson, James T. Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy. Oxford University Press; New York, 2001.)

Early Cases

Despite the Supreme Court's ruling in Plessy and similar cases, people continued to press for the abolition of Jim Crow and other racially discriminatory laws. One particular organization that fought for racial equality was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) founded in 1909. From 1935 to 1938, the legal arm of the NAACP was headed by Charles Hamilton Houston. Houston, together with Thurgood Marshall, devised a strategy to attack Jim Crow laws in the field of education. Although Marshall played a crucial role in all of the cases listed below, Houston was the head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund while Murray v. Maryland and Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada were decided. After Houston returned to private practice in 1938, Marshall became head of the Fund and used it to argue the cases of Sweat v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma Board of Regents of Higher Education .

Pearson v. Murray (Md. 1936)

Unwilling to accept the fact that the University of Maryland School of Law was rejecting Black applicants solely because of their race, beginning in 1933 Thurgood Marshall, who was rejected from this law school because of its racial acceptance policies, decided to challenge this practice in the Maryland court system. Before a Baltimore City Court in 1935, Marshall argued that Donald Gaines Murray was just as qualified as white applicants to attend the University of Maryland's School of Law and that it was solely due to his race that he was rejected. He argued that since law schools for Black students were not of the same academic caliber, at the time, as the University's law school, the University was violating the principle of "separate but equal." Marshall also argued that the disparities between the law schools for white students and Black students were so great that the only remedy would be to allow students like Murray to attend the University's law school. The Baltimore City Court agreed, and the University appealed to the Maryland Court of Appeals. In 1936, the Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Murray and ordered the law school to admit him. Two years later, Murray graduated with his law degree.

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada (1938)

Beginning in 1936, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund decided to take on the case of Lloyd Gaines, a graduate student of the HCBU Lincoln University in Missouri. Gaines had applied to the University of Missouri Law School but was denied admission because of his race. The State of Missouri gave Gaines the option of either attending a Black law school that it would build (Missouri did not have any all-Black law schools at this time) or Missouri would help to pay for him to attend a law school in a neighboring state. Gaines rejected both of these options and, with the help of Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, he sued the state to attend the University of Missouri's law school. By 1938, his case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, and, in December of that year, the Court sided with him. The six-member majority stated that since law school for Black students did not exist in the State of Missouri, the "equal protection clause" required the state to provide within its boundaries a legal education for Gaines. In other words, since the state provided legal education for white students, it could not send Black students, like Gaines, to school in another state.

Sweat v. Painter (1950)

Encouraged by their victory in Gaines' case, the NAACP continued to attack legally sanctioned racial discrimination in higher education. In 1946, an African American man named Heman Sweat applied to the law school at the University of Texas whose student body was white. The University set up an underfunded law school for Black students. However, Sweat employed the services of Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and sued to be admitted to the University's law school attended by white students. When the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1950, the Court unanimously agreed with him, citing as its reason the blatant inequalities between the University's law school (the school for white students) and the hastily erected school for Black students. In other words, the two schools were "separate," but not "equal." Like the Murray case, the Court found the only appropriate remedy for this situation was to admit Sweat to the University's law school.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma Board of Regents of Higher Education (1950)

In 1949, the University of Oklahoma admitted George McLaurin, an African American male, to its doctoral program. However, it required him to sit apart and eat apart from the rest of his class. McLaurin sued to end the practices, stating that they had an adverse impact on his academic pursuits. McLaurin was represented by Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. It eventually went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In an opinion delivered on the same day as the decision in Sweat , the Court stated that the University's actions concerning McLaurin were adversely affecting his ability to learn and ordered that the practices cease immediately.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954, 1955)

The case that came to be known as Brown v. Board of Education was actually the name given to five separate cases that were heard by the U.S. Supreme Court concerning the separate but equal concept in public schools. These cases were Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka , Briggs v. Elliot, Davis v. Board of Education of Prince Edward County (VA.) , Bolling v. Sharpe , and Gebhart v. Ethel . While the facts of each case were different, the main issue was the constitutionality of state-sponsored segregation in public schools. Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund handled the cases.

The families lost in the lower courts, then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

When the cases came before the Supreme Court in 1952, the Court consolidated all five cases under the name of Brown v. The Board of Education. Marshall argued the case before the Court. Although he raised a variety of legal issues on appeal, the central argument was that separate school systems for Black students and white students were inherently unequal, and a violation of the "Equal Protection Clause" of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. He also presented the results of sociological tests, such as the one performed by social scientists Kenneth and _______ Clark, arguing that segregated school systems had a tendency to make Black children feel inferior to white children. In light of those findings, Marshall argued that such a system should not be legally permissible.

Meeting to decide the case, the Justices of the Supreme Court realized that they were deeply divided over the issues raised. Unable to come to a decision by June 1953 (the end of the Court's 1952-1953 term), the Court decided to rehear the case in December 1953. During the intervening months, Chief Justice Fred Vinson died and was replaced by Gov. Earl Warren, of California. After the case was reheard in 1953, Chief Justice Warren was able to bring all of the Justices together to support a unanimous decision declaring unconstitutional the concept of separate but equal in public schools. On May 14, 1954, he delivered the opinion of the Court, stating that "We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. . ."

DISCLAIMER: These resources are created by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts for educational purposes only. They may not reflect the current state of the law, and are not intended to provide legal advice, guidance on litigation, or commentary on any pending case or legislation.

Legal Dictionary

The Law Dictionary for Everyone

Brown v. Board of Education

Following is the case brief for Brown v. Board of Education, United States Supreme Court, (1954)

Case Summary of Brown v. Board of Education:

- Oliver Brown was denied admission into a white school

- As a representative of a class action suit, Brown filed a claim alleging that laws permitting segregation in public schools were a violation of the 14 th Amendment equal protection clause .

- After the District Court upheld segregation using Plessy v. Ferguson as authority, Brown petitioned the United States Supreme Court.

- The Supreme Court held that segregation had a profound and detrimental effect on education and segregation deprived minority children of equal protection under the law.

Brown v. Board of Education Case Brief

Statement of Facts:

Oliver Brown and other plaintiffs were denied admission into a public school attended by white children. This was permitted under laws which allowed segregation based on race. Brown claimed that the segregation deprived minority children of equal protection under the 14 th Amendment. Brown filed a class action, consolidating cases from Virginia, South Carolina, Delaware and Kansas against the Board of Education in a federal district court in Kansas.

Procedural History:

Brown filed suit against the Board of Education in District Court. After the District Court held in favor of the Board, Brown appealed to the United States Supreme Court. The Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Issues and Holding:

Does the segregation on the basis of race in public schools deprive minority children of equal educational opportunities, violating the 14 th Amendment? Yes.

The Court Reversed the District Court’s decision.

Rule of Law or Legal Principle Applied:

Separating educational facilities based on racial classifications is unequal in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14 th Amendment.

The Court held that looking to historical legislation and prior cases could not yield a true meaning of the 14 th Amendment because each is inconclusive.

At the time the 14 th Amendment was enacted, almost no African American children were receiving an education. As such, trying to determine the historical intentions surrounding the 14 th Amendment is not helpful. In addition, few public schools existed at the time the amendment was adopted.

Analyzing the text of the amendment itself is necessary to determine its true meaning. The Court held the basic language of the Amendment suggests the intent to prohibit all discriminatory legislation against minorities.

Despite the fact each facility is essentially the same, the Court held it was necessary to examine the actual effect of segregation on education. Over the past few years, public education has turned into one of the most valuable public services both state and local governments have to offer. Since education has a heavy bearing on the future success of each child, the opportunity to be educated must be equal to each student.

The Court stated that the opportunity for education available to segregated minorities has a profound and detrimental effect on both their hearts and minds. Studies showed that segregated students felt less motivated, inferior and have a lower standard of performance than non-minority students. The Court explicitly overturned Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 U.S. 537 (1896), stating that segregation deprives African-American students of equal protection under the 14 th Amendment.

Concurring/ Dissenting opinion :

Unanimous decision led by Justice Warren.

Significance:

Brown v. Board of Education was the landmark case which desegregated public schools in the United States. It abolished the idea of “ separate but equal .”

Student Resources:

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/rights/landmark_brown.html https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/347/483

Educator Resources

Biographies of Key Figures in Brown v. Board of Education

In 1952, the Supreme Court agreed to hear five cases collectively from across the country, consolidated under the name Brown v. Board of Education . This grouping of cases from Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and Delaware was significant because it represented school segregation as a national issue, not just a southern one. Each case was brought on the behalf of elementary school children, involving all-Black schools that were inferior to white schools.

In each case, the lower courts had ruled against the plaintiffs, noting the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling of the United States Supreme Court as precedent. The plaintiffs claimed that the "separate but equal" ruling violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. In 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that state-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional.

The Five Cases Consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education

Brown v. board of education of topeka, kansas.

( Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka et al. )

Linda Brown Linda Brown, who was born in 1943, became a part of civil rights history as a third grader in the public schools of Topeka, KS. When Linda was denied admission into a white elementary school, Linda's father, Oliver Brown, challenged Kansas's school segregation laws in the Supreme Court. The NAACP and Thurgood Marshall took up their case, along with similar ones in South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware, as Brown v. Board of Education. Linda Brown died in 2018.

Oliver L. Brown Oliver Brown, a minister in his local Topeka, KS, community, challenged Kansas's school segregation laws in the Supreme Court. Mr. Brown’s 8-year-old daughter, Linda, was a Black girl attending fifth grade in the public schools in Topeka when she was denied admission into a white elementary school. The NAACP and Thurgood Marshall took up Brown’s case along with similar cases in South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware as Brown v. Board of Education. Oliver Brown died in 1961.

Robert L. Carter Born in 1917, Robert Carter, who served as an attorney for the plaintiffs in Briggs v. Elliott, was of particular significance to the Brown v. Board of Education case because of his role in the Briggs case. Carter secured the pivotal involvement of social scientists, particularly Kenneth B. Clark, who provided evidence in the Briggs case on segregation's devastating effects on the psyches of Black children.

Harold R. Fatzer As Attorney General of Kansas, Harold Fatzer argued the case for the appellees (Kansas) in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. Mr. Fatzer served as Kansas Supreme Court Justice from February 1949 to March 1956.

Jack Greenberg Jack Greenberg, who was born in 1924, argued on behalf of the plaintiffs in the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case, and worked on the briefs in Belton v. Gebhart. Jack Greenberg served as director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund from 1961 to 1984.

Thurgood Marshall Born in 1908, Thurgood Marshall served as lead attorney for the plaintiffs in Briggs v. Elliott. From 1930 to 1933, Marshall attended Howard University Law School and came under the immediate influence of the school’s new dean, Charles Hamilton Houston. Marshall, who also served as lead counsel in the Brown v. Board of Education case, went on to become the first African-American Supreme Court Justice in U.S. history. Justice Marshall died in 1993.

Frank Daniel Reeves Frank D. Reeves, who was born in 1916, served as an attorney for the plaintiffs in the Brown v. Board decisions of 1954, and 1955 ( Brown II). Mr. Reeves was the first African-American person appointed to the District of Columbia Board of Commissioners, although he declined the position. Frank Reeves died in 1973.

Charles Scott Charles Scott was a Topeka, KS, based lawyer who initially began the Brown case on behalf of Oliver Brown and the other litigants.

John Scott John Scott was a Topeka, KS, based lawyer who initially began the Brown case on behalf of Oliver Brown and the other litigants.