Become an Insider

Sign up today to receive premium content.

Digital Art Education Tools Encourage Students' Creativity and Curiosity

Julie Boyland is a freelance associate editor for EdTech: Focus on K-12 . She has a bachelor’s degree in Consumer Journalism and a certification in New Media Studies from the University of Georgia, and a certification in Social Media Management from Georgetown University.

The classroom setting wasn’t the only thing upended during the shift to remote learning. Humanities courses that had traditionally relied on hands-on instruction, such as art education, also faced myriad challenges during the transition.

“Even amid difficult budget decisions, a continued commitment to certified visual arts educators and sequential visual arts and design instruction remains a priority,” said National Art Education Association President Thom Knab in an open letter to K–12 superintendents, principals and school board members in May.

Teachers have had to reinvent their approach to art education, and technology has played a pivotal role. A national study by Adobe Education found that teachers and students alike value creativity in the modern classroom and hope to see an increased use of technology in their courses. New tech tools and collaborative resources offer an opportunity to build on this trend. Art educators can create fun and engaging lesson plans that foster an appreciation for the humanities from an early age.

Data Shows a Growing Focus on Creativity in K–12 Education

According to a study by Adobe Education , 76 percent of Generation Z students and 75 percent of teachers wish there was a greater focus on creativity in their classes. Educational priorities have evolved, and today’s lesson plans focus more on interactive tools and less on memorization.

When comparing the perceptions of Gen Z students and Gen Z educators, the Adobe study found that both groups consider technology a defining characteristic of their generation and that both believe creativity will play a defining role in their future success. The study also indicates a demand and a need for courses that focus on digital art and creativity in the classroom — and that technology is the most fitting instrument for change.

DISCOVER: Learn how the remote learning pivot sparked innovation in education.

Tech Tools Boost Creativity in the Classroom

With the right approach, technology can not only prove compatible with art education, it can enhance it. Teachers can re-create in-person field trip experiences with the virtual resources from Penn State University’s Palmer Museum of Art or travel through notable moments in art history with the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s interactive “time machine .” Still, one of the most important elements of art education is the focus on creativity. It is crucial, experts say, to empower students to express themselves and create their own works of art, whether through digital tools or traditional mediums like paint or charcoal.

“Creativity is really important for students because it gives them an outlet for expressing their ideas and putting a personal touch on their understanding of concepts,” says educator Jeff Larson in an Adobe video case study . Larson is a former animation instructor at Balboa High School in San Francisco.

Like other schools around the nation, Balboa High School has used digital tools and online resources to optimize student creativity in the classroom. Students there use Adobe Creative Cloud to create multimedia content and explore their imaginations. Roanoke, Va.’s Cave Spring Middle School is another example of successful implementation of digital art resources. In 2018, students there began using Adobe Spark to strengthen critical thinking skills and stimulate creativity in the classroom.

With the shift to hybrid and distance learning models, these digital tools have become increasingly prevalent throughout art education. Most notably, teachers have used videoconferencing software, like Zoom and Google Classroom, to supplement in-person art instruction.

To make of the most of your virtual classroom, it’s critical to make sure you have the right equipment and setup . Many smartphones and tablets offer HD cameras that are suitable in quality for art classrooms. Incorporating tripods can also help ensure better visual quality for instruction.

- Digital Content

- Online Learning

Related Articles

Unlock white papers, personalized recommendations and other premium content for an in-depth look at evolving IT

Copyright © 2024 CDW LLC 200 N. Milwaukee Avenue , Vernon Hills, IL 60061 Do Not Sell My Personal Information

How to Maximize Creativity When Teaching Online

Art Education and the Coronavirus (COVID-19)

When setting up your classroom for online learning, it’s important to rethink the “how” and the “what” of your curriculum. While some might be teaching an art survey type of course, which lends itself to a variety of options, others are left wondering, what now? Teaching ceramics or metalsmithing is just not going to happen as it would in the classroom. Finding a balance in preparing our students for next year and beyond with skills that can carry throughout their life and keep them creating is a challenge. Teaching a traditional drawing course might allow you to continue to build skills, but when soldering at home isn’t an option, it’s time to rethink the purpose of your art curriculum and teaching online.

When changing your teaching location or moving to online learning, it is essential to be grounded in your foundational teaching philosophy. Personally, teaching for creativity is always at the root of what I teach. Regardless of what my students will become or where they will go in their careers, creative thinking will help them approach life with curiosity and engage with the world in deep and meaningful ways.

Teaching for creativity means I want students to:

- Be creative thinkers.

- Learn creative thinking skills that apply outside of the art room.

- Use their heads and their hands to solve a problem.

- Consider and identify problems that need solving.

- Practice thinking outside-the-box when given constraints.

- Generate ideas, consider many options, and collaborate for feedback.

So, how do you ensure you are engaging your students with creativity while away from the classroom?

Take a look at these three categories of creative thinking that can help set you and your students up for success:

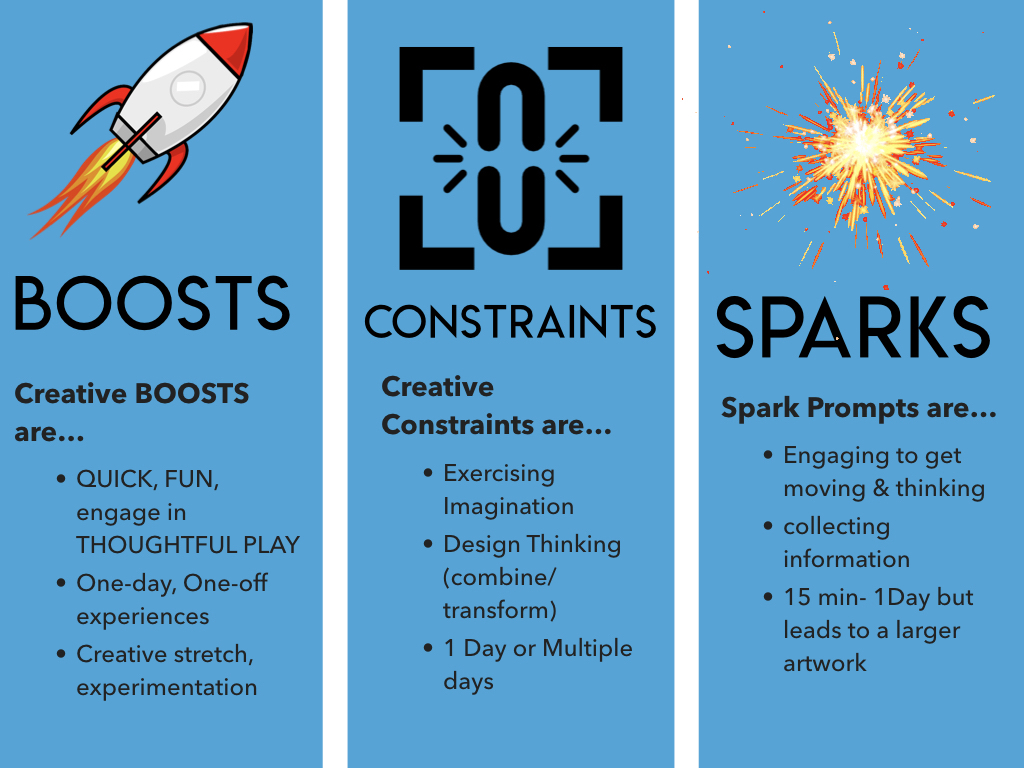

Creative Boosts

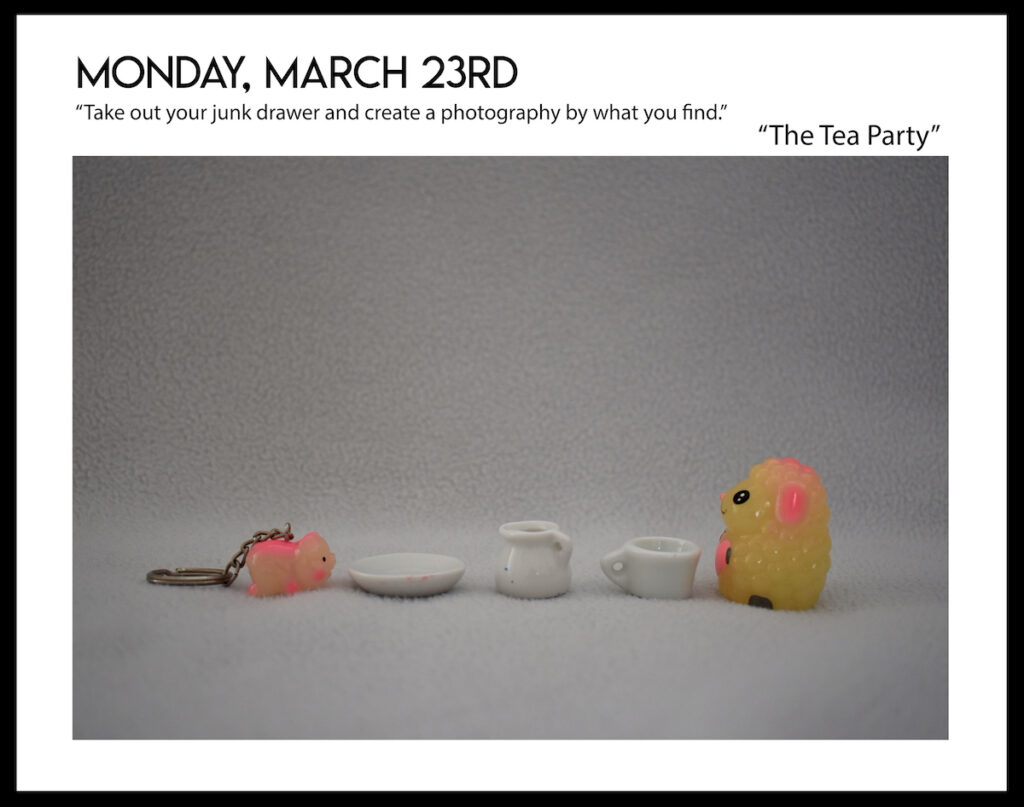

Creative Boosts are quick and fun exercises that engage in thoughtful play. These are usually one-day, one-off experiences to incorporate in the classroom or out. Boosts provide a creative stretch when working through a longer artwork. They are also rooted in exploration and experimentation, such as creative uses for unconventional art media.

Examples of Creative Boosts:

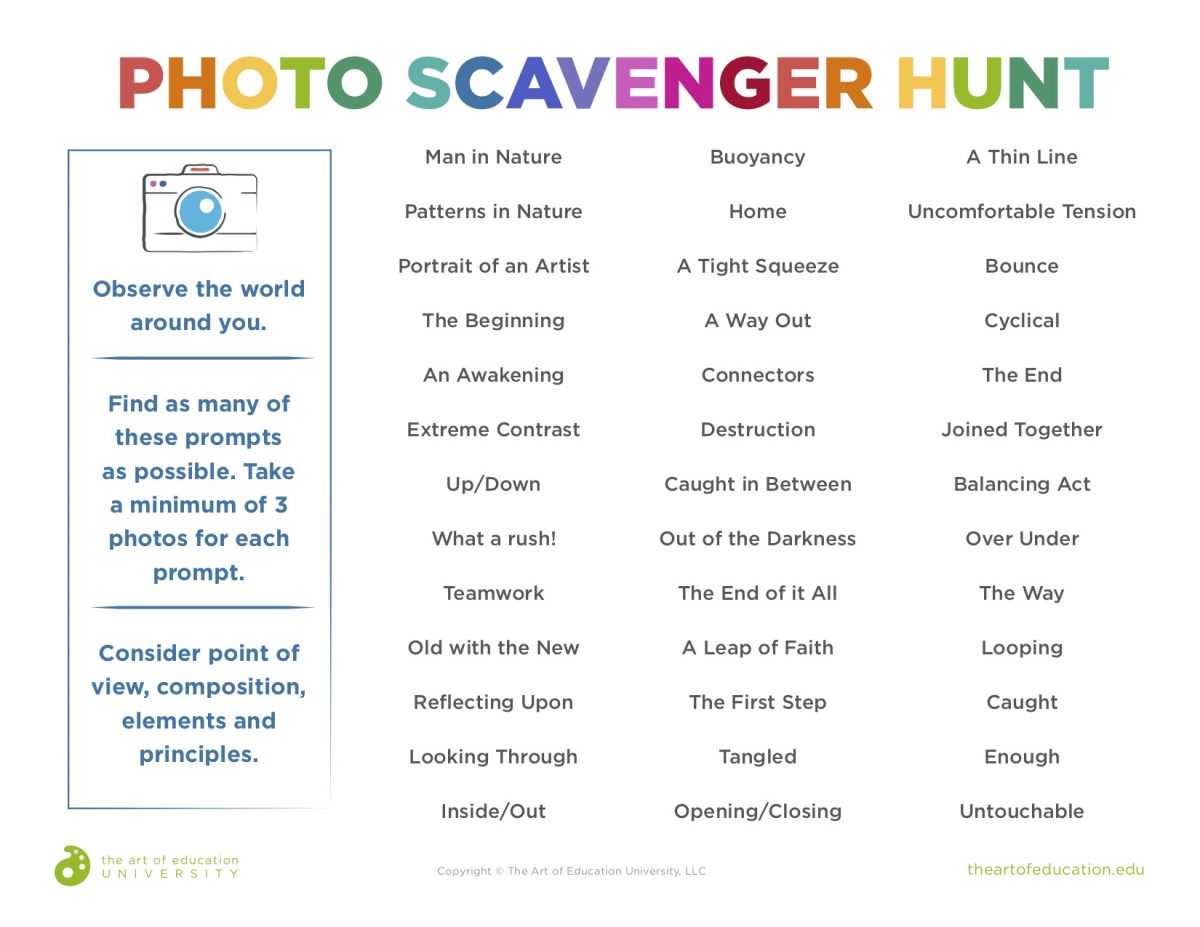

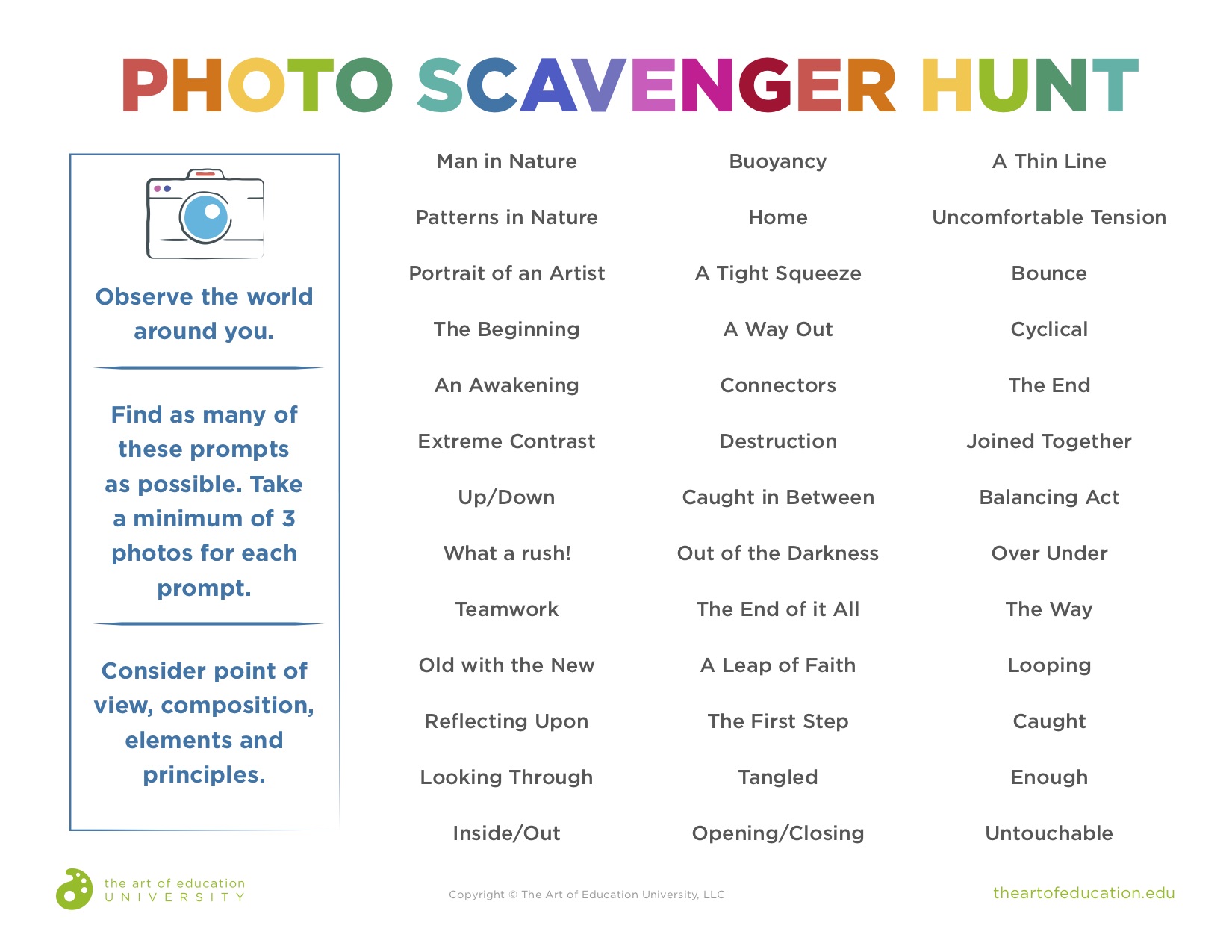

Scavenger Hunts 100 Sketchbook Prompts 50 Visual Journal Prompts Silly Drawing Prompts

Download a great scavenger photo hunt here.

Download Now!

A few tips to remember when transferring Creative Boosts into your online teaching practices:

- Ground yourself in your big-picture outcomes. For example, if you didn’t teach them how to “technically” draw, then don’t expect more than some sketches on a looseleaf piece of paper. The point of these exercises is more about play than technical skills.

- Set up new expectations of what this all looks like. If you want your students to produce more than one sketch, make sure to tell them how many you expect, as well as how to annotate their work.

- When it comes to discovering materials at home, it will take students longer than you expect. When we are in the classroom, we often provide a range of materials to experiment with. At home, you are not only asking students to create but also to identify materials they could explore with.

Constraint Challenges

Constraint Challenges exercise the imagination through unrealistic prompts and design thinking challenges. Consider how your students could combine and transform to push limits and boundaries. Especially in a time when materials may not be available, the imagination is boundless. Constraint Challenges usually take one day to a week. Students could spend thirty minutes brainstorming ideas, or five days folding paper and assembling cardboard.

Examples of Constraint Challenges:

- Unimaginable Item : Create a prototype (sketch or create) for an unimaginable need such as “Design a treadmill for a worm.” List the choices and constraints. Pitch your product with a short video.

- Paper RePurpose: Create a “new and improved” functional item out of paper. Document your item being used for its new purpose.

- Build a Fort: Create a fort optimal for hours of video-gaming. Consider what materials are most conducive for longevity as well as maximum laziness. Use only materials that are readily available in your home.

Here are a few tips for Constraint Challenges:

- Push students to think about real situations without constraints. For example, get them to think about available materials or gravitational pull.

- Try giving them a fantastical problem. Ask them to identify both choices and existing constraints.

- Give students a choice of materials to create maquettes or develop prototypes. Especially while at home, you never know what students might have at their disposal. If you give a constraint such as material, allow for options. Instead of “create using cardboard,” ask students to identify their material choice and limit them to how much of one material they can use.

Creative Sparks

Creative Sparks are the little push of creativity students can use to inspire a more developed artwork. These are short exercises from fifteen minutes to one day. Students use these to get moving and thinking, to collect information, and to engage their next creation.

Examples of Creative Sparks:

- Color Palette Binge: Watch your favorite movie or T.V. series. Make a color swatch book of the main colors you find in a particular scene or throughout the movie. Create an artwork that responds to your new color palette.

- Sound Off: Go outside and document all the sounds you hear. Or make a sensory journal to describe all of your senses in a new experience. Make sketches, jot down notes, record sounds, take photos. Using this new collection, create a poem or short story. Then, make an artwork.

- Mundane How-Tos: Make a PBJ sandwich, tie your shoes, teach someone how to whistle. Document the steps it takes to teach this ordinary task. Then, make an instructional document to teach someone how to do a mundane task. Create a zine, a comic page, an illustrated artwork, or a video.

Some tips for your Creative Sparks:

- Give your students a series of sparks for all to complete. Then, they can choose which spark interested them the most to pursue a developed artwork. Or, ask your students to review all the Spark options and choose what interests them the most to try out before creating an artwork.

- Sparks are a great way to demonstrate the Creative Process. Through the planning phase, students explore and use these as planning for ideas and documenting as they develop further into their work.

- Give students a choice of documentation. Students may be able to not only sketch out ideas, but also make short videos, record audio, make a timelapse, and more.

With so many changes happening at once, continue to stay grounded in your teaching philosophy. Continue to find ways to engage with your students, help take their minds off of the more serious news, and help them create away from the computer screen. Remember to always consider your teaching options through the lens of equity and access for your students. Now is a perfect time to demonstrate the importance of creative thinking when changing to online learning. Just think, you are not only supporting your students in creating artwork but also providing them essential skills to think outside-the-box as they solve our world’s next big problems.

Can you identify your philosophical foundation for teaching in your art room? How does that help you remain grounded when your world turns upside down?

In what ways are you teaching creativity through remote learning?

How can you schedule Creativity Boosts, Constraint Challenges, and Creative Sparks in your curriculum?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.

Janet Taylor

Janet Taylor, a high school art educator, is also AOEU’s K–12 Content Specialist and a former AOEU Writer. She geeks out about choice-based curriculum, assessment strategies, and equipping new teachers.

No Wheel? No Problem! 5 Functional Handbuilding Clay Project Ideas Students Love

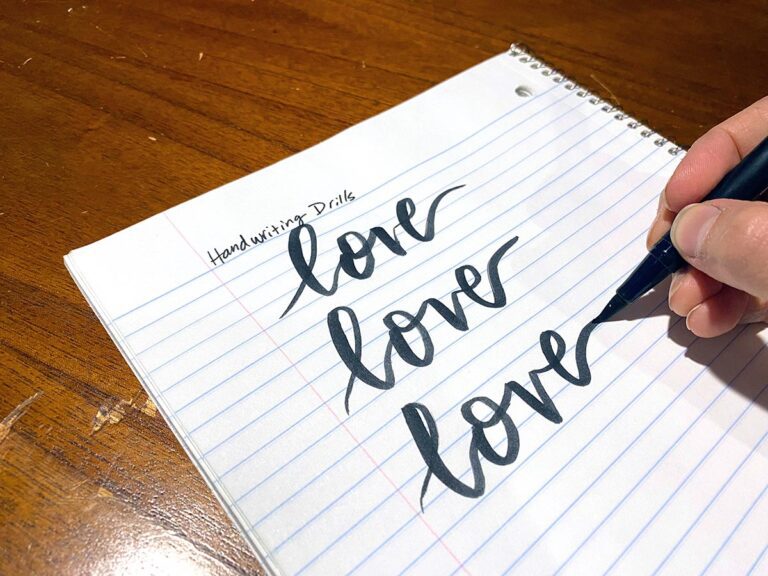

Love Letters: 3 Amazing Ways to Integrate Calligraphy, Cursive, and Typography

Embracing the Magic: A Love Letter to Pinhole Photography in the Art Room

A Love Letter to Yarn: 5 Reasons Why Art Teachers Are Obsessed

STACIE LEE BENNETT-WORTH

ARTIST-RESEARCHER

The role of Digital Creativity in Creative Arts Education: Pedagogy and digital tools for ‘making.’

Being an artist in current times, often requires a myriad of skills, far reaching those required of the practice itself. Our lives are increasingly interwoven with the digital landscape and although art can be devoid of digital in its form, it is likely to be somehow intrinsically linked, as our means of communication and self-expression are so often mediated by screens, applications, and online spaces.

Whether you are a performance artist, visual artist, designer, illustrator or any other type of artist, engagement with the digital is something that has become somewhat of a necessity, not only for the sharing and promotion of work, but also a tool to challenge, interrogate and expand the form further.

The pandemic and the digital learning shift

The pandemic has accelerated many artists’ forays into the digital, as it has provided a way to communicate their work to audiences while theatres, galleries and other public spaces were closed. While the ubiquity of technology has bolstered this shift, it has also revealed huge gaps in the infrastructure needed to support digital creativity in the arts – especially in education.

Not only do many institutions lack access to digital tools themselves, but there is also a lack of training and support in this area that encourages and empowers teachers to explore digital technologies within their pedagogy and practice.

Terms such as ‘disaster digital learning’ (Vilson,2020) and ‘emergency remote teaching’ (Hodges et al, 2020) are phrases that have come into being recently and reference the difference between a pedagogy that is adopted as a reaction to a set of circumstances at play (i.e., a global pandemic) and a pedagogy that is specifically designed for the current times. It is important to note the subtle difference between the two; ‘disaster digital learning’ suggests that you may be dealing with an unprecedented situation meaning the fundamental values and objectives for teaching and learning are reactive and therefore not representative of the usual standards of working. Yet while all pedagogical approaches need to adopt a level of flexibility, what is most notable now, is the pandemic’s impact on the arts and how the industry has altered indefinitely. Creative arts curricula need to reflect this shift.

Of course, necessity is the mother of invention and although digital approaches in arts education were already well underway pre-COVID particularly at HE level, it is important that the new tools and strategies adopted throughout this time do not simply set the precedent for creative teaching and learning of the future. Rather this should be a peek into the window of possibility, providing a proof of concept for a critical digital pedagogy for the arts, showing what could be achieved with good support and infrastructure. With pre-HE taking priority after already being behind the curve pre-pandemic.

Understanding your field in the context of the digital

The last few years have been particularly challenging for the arts. Funding and subject intake in arts education was dwindling pre-pandemic and although the imposed lockdowns saw an increased engagement in digital performance, online creative classes and the use of creative apps also piqued(Lighttricks.com), the creative arts are still facing huge governmental cuts despite their proven benefits to society.

Understanding how digital tools are and can be used within your field – and the arts more broadly – is important for both situating your subject within the current climate and working towards future-proofing your curriculum to be relevant in coming years.

This way of thinking is important not only for ensuring those embarking on a creative education are equipped for the current challenges of the industry but it also, rather sadly, seems an important step in boosting the perceived validity of creative arts education.

Exposing new avenues into creative careers

A “digital skillset” is one of the most requested candidate specifications across recruitment now (World Skills UK, 2020), and while it may be a vague term within your field, exploring digital tools as one of the strategies for ‘making’ – whatever that means to you – can be both exciting and certainly beneficial for future cross-disciplinary collaboration.

As with any new skills development, exposing your craft to new ways of working can often unlock avenues you never knew existed, providing new creative opportunities and challenging your practice. Having knowledge of digital processes within the arts – even if you are not interested in pursuing them yourself – can lead to interesting and meaningful collaborations. Just understanding the language of digital technologies can be enough to enable you to foresee new possibilities and relationships across disciplines.

Repurposing existing skill sets and encouraging play

The ubiquity of everyday technologies such as mobile phones has led to a generational shift in the way we communicate, the way we work and fundamentally, the way we live. Approximately 98% of UK households have a mobile phone (Statista.com) and although the way they are used varies significantly, there is still a presumed base knowledge and understanding of how the basic technology works. Beyond making calls and sending text messages, most mobile devices now also provide the user with a myriad of creative tools to explore in their everyday lives. For many art forms there are endless exciting possibilities to be explored, even within a single mobile device, that can not only challenge some of the traditions of our practices but can also help ideas expand above and beyond the realms of possibility. This idea suggests that even everyday technologies like mobile phones can provide a wealth of opportunity for a user to begin to explore the creative possibilities of digital technologies.

Social media applications for example, now have sophisticated built-in image manipulation tools, something that could be utilised and explored for creative output by students. Other options such as video editing, text and image composition and live streaming are also features that are supported across these networks and can be utilised alongside a creative arts curriculum. Young people are often already utilising and importantly playing with these tools in their everyday lives and therefore reframing these skills in the context of teaching and learning can be very beneficial for developing critical digital creativity and encouraging creative learning.

Encouraging play, as a critical form of experimentation is a very common principle in the creative arts and this should extend to any experimentation within digital tools within the form. “When you play, you are constantly experimenting, taking risks, trying new things, and testing boundaries. Having a playful attitude means that you’re willing to try new things and experiment and the most creative things happen when you have that type of playful attitude.” (Resnick, 2019) Digital tools often offer a very clear possibility of iteration with little consequence, this means that often digital spaces are a fertile ground for rapid prototyping i.e., testing ideas quickly and not getting bogged down with the pressure of having to ‘make’ something!

Overall, exposing your creative practice and pedagogy to digital technologies, is beneficial in many ways and it doesn’t need to be overwhelming.. Even everyday, lo-fi and free technologies/tools can provide a fertile ground for experimentation and offer foundational understanding of new techniques and practices that can help to unlock new and relevant ways of working.

On Disaster Distance Learning in New York City

https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/104648

https://www.statista.com/statistics/387184/number-of-mobile-phones-per-household-in-the-uk/

Click to access Disconnected-Report-final.pdf

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Active Learning - Beyond the Future

Strategies for Digital Creative Pedagogies in Today’s Education

Submitted: 07 May 2018 Reviewed: 03 August 2018 Published: 05 November 2018

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.80695

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Active Learning - Beyond the Future

Edited by Sílvio Manuel Brito

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

2,145 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

Overall attention for this chapters

Creativity and digital technologies are considered to be central for success and development in the current society, becoming crucial educational objectives worldwide. Nevertheless, education often fails to keep pace with creative and digital economies; this is mainly because teachers are not prepared for adopting pedagogical strategies that foster creativity or for fully exploiting the educational potential of digital technologies. Based on the seminal theories of creativity, we propose an innovative framework for applying creative teaching practices mediated by digital technologies: in the light of constructivist and constructionist approaches, we suggest a series of digital tools which are particularly suitable to the emergence of creativity, i.e. manipulative technologies, educational robotics and game design and coding. Furthermore, we shape the concept of digital creative pedagogies (DCP) and establish a set of characteristic components of teaching practices which contribute to the development of students’ creativity. Drawing on a substantial body of research, the chapter intends to embed educational creativity in the digital culture.

- digital creativityd

- digital creative pedagogies

- manipulative technologies

- educational robotics

- game design and coding

Author Information

Mario barajas *.

- University of Barcelona, Spain

Frédérique Frossard

Anna trifonova.

- CreaTIC Nens Ltd., Spain

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

Creativity is considered to be critical for facing the social and economic changes of today’s society [ 1 , 2 ], as well as for attaining personal development, social inclusion, active citizenship and employment [ 3 ]. In addition, the labour market depends more and more on employees’ abilities to work with technologies, as well as to generate new ideas, products and practices [ 4 ]. In this context, digital and creative skills have gained the attention of worldwide policies and have become important educational objectives [ 5 ].

Nevertheless, a gap remains between policies and practices, as education often fails to keep pace with creative and digital economies [ 4 , 6 ]. This is mainly because teachers are not prepared for adopting pedagogical strategies that foster creativity or for fully exploiting the educational potential of digital technologies.

Beghetto [ 2 ] identified a series of obstacles to the integration of creativity in the classroom, including convergent teaching practices and teachers’ negative beliefs towards creativity. Furthermore, educators are not prepared to apply creative teaching strategies which match their institutional and curricular requirements [ 7 ].

Regarding digital technologies, the ‘EC report on initial teacher education in Europe’ [ 8 ] states that only half of European countries integrate digital education in teacher education. Furthermore, most teachers use digital technologies mainly to prepare their teaching, rather than to work with students during lessons. As a result, between 50 and 80% of students in Europe never use digital textbooks, exercise software, simulations or learning games.

This chapter proposes an innovative framework aiming to prepare educators for applying creative teaching practices mediated by digital technologies. We first attempt to conceptualise educational creativity, i.e. we present the seminal theories and definitions of creativity and the main characteristics of creative education, as well as a series of creative pedagogies. Afterwards, we propose a framework for digital creativity in education, including a definition, a series of pedagogical theories and digital tools which are particularly suitable to the emergence of creativity. We finally establish a set of characteristic components of digital creative pedagogies (DCP), that is, teaching practices which contribute to the development of students’ creativity.

2. Creativity in education

2.1 different approaches to the study of creativity.

Creativity constitutes a complex and elusive concept which remains difficult to explore. It has been studied through the lens of different paradigms, for example, pragmatic, psychodynamic, psychometric, cognitive and evolutionary approaches [ 9 ]. Some of those have brought valuable contributions to the understanding of creativity; nevertheless they do not allow for a holistic approach of the phenomenon. Hence, several theories attempted to explore its different dimensions in a comprehensive manner.

For instance, Csikszentmihalyi [ 10 ] described creativity as the result of a system composed of three distinct elements: (a) the domain , which contains a specific set of rules and practices; (b) the individual, who produces a novel variation in the content of the domain through cognitive processes, personality traits and motivation; this variation is evaluated by (c) the field for its inclusion in the domain.

Furthermore, Rhodes [ 11 ] developed the four P’s model, which places creativity at the interplay of four distinct strands, i.e. process (the different stages of a creative activity), person (the characteristics of individuals), press (the qualities of the environment where creativity happens) and product (the tangible or intangible outcomes of the creative process). Rhodes’ classification has become a major framework for the holistic exploration of creativity. The next subsections examine the four components in the light of influential theories of creativity.

2.1.1 Process-oriented approaches

Those theories mostly explore and describe the creative process through an iterative sequence of stages [ 12 ], which commonly consist of the identification of the task, a phase of preparation and an evaluation of the obtained outcome. Nevertheless, process models present some discrepancies: some researchers view the emergence of ideas as a sudden and intuitive process characterised by an illumination or insight (e.g. [ 10 ]); on the contrary, other theories describe a mindful process of idea generation [ 12 ]. For instance, the well-known componential model of Amabile [ 13 ] proposes a system of five phases: (a) problem or task identification (conscious recognition of the task or problem), (b) preparation (building or reactivation of the information which is useful to the completion of the task), (c) response generation (creation of possible solutions or responses), (d) response validation (evaluation of the possible responses or solutions) and (e) outcome (evaluation and diffusion of the outcome).

2.1.2 Person-oriented approaches

Here researchers use biographical and historiometric methodologies to explore the individual characteristics and personality traits of creative persons. Such theories result in a series of creative individual components which include thinking styles, personality attributes (e.g. a positive disposition towards overcoming obstacles, taking risks and tolerating ambiguity) and intellectual abilities [ 14 ], as well as concentration, playfulness, discipline, passion and objectivity [ 10 ]. Amabile [ 13 ] brings a classification which differentiates domain-relevant skills (knowledge and skills in the domain), task motivation (extrinsic and/or intrinsic) and creativity-relevant skills (personality characteristics, like flexibility and a persistent work style).

2.1.3 Press-oriented approaches

This strand concentrates on the characteristics of the environment which may nurture or hinder creativity. First, social, cultural and political factors may influence creativity [ 15 ], like family upbringing, cultural traditions and the historical milieu [ 16 ]. In addition, Csikszentmihalyi [ 10 ] highlighted some environmental features which may foster creativity, including training, expectations, resources, recognition and reward. Similarly, Amabile and Gryskiewicz [ 17 ] identified a series of elements of the workplace environment which may foster creativity, such as freedom, challenge and leaders’ recognition. At the contrary, some factors proved to hinder creativity, like time pressure, evaluation [ 17 ], lack of respect and competition [ 18 ].

2.1.4 Product-oriented approaches

The last dimension focuses on the tangible or intangible outcomes of the creative process. Researchers commonly define two characteristics of creative products, namely, usefulness and novelty [ 12 , 13 ]. Usefulness refers to the adequacy of the outcome to its context of use. As for novelty, literature distinguishes between Big-C (consensual) and little-c (personal) creativity [ 19 ]. Kaufman and Beghetto [ 20 ] proposed a Four-C Model which differentiates mini-c (interpretive creativity), little-c (everyday creativity), Pro-C (expert creativity) and Big-C (‘legendary’ creativity).

2.2 Towards a definition

Defining creativity results to be a complex task [ 21 ]. The word has been applied to a variety of fields, settings and theories [ 22 ]; hence, scientific literature lacks a sound definition. Nevertheless, there appears to be consensus on the main features of creativity [ 23 ]: it refers to the ability to create something novel and appropriate [ 24 ]. The term ‘novel’ describes an original solution, while the term ‘appropriate’ refers to the usefulness of the product as applied to a specific need [ 9 ].

As applied to the field of education, the NACCCE [ 22 ] provided a comprehensive definition, which does not limit to the product dimension, describing creativity as an ‘imaginative activity fashioned so as to produce outcomes that are both original and of value’ (p. 30). Cremin et al. [ 25 ] added some components to this definition, so that it matches a personal view of creativity (little-c): ‘purposive imaginative activity generating outcomes that are original and valuable in relation to the learner’. In this view, creativity processes involve four characteristics: (a) they consist of thinking imaginatively, (b) they are purposeful (i.e. directed towards a specific goal), (c) they result in an original and valuable outcome and (d) the learner constitutes the reference point.

2.3 Characteristics of creative education

A democratic approach : traditionally, creativity is seen as a quality reserved for exceptionally talented individuals [ 22 ]. This exclusive perspective recently changed towards an inclusive one, to which all people from all ages can be creative [ 16 , 26 ]. This new angle is widely adopted in the field of education, considering that all students have a creative potential which can be fostered or hindered depending on the teaching strategies used [ 27 ].

A focus on little-c creativity : small levels of creativity give importance to personal processes beyond outstanding accomplishments. As applied to education, this perspective encourages students to develop new and personally meaningful insights and discoveries, as well as to attain their full potential in their everyday domains [ 27 ].

A domain-wide approach : creativity is often associated to the domain of arts [ 22 ]. Recently, this scope has been widened to other areas of everyday life [ 27 ]. Hence, in the field of education, creativity can be developed in all curricular subjects, such as languages and science [ 28 ].

2.4 Creative pedagogies

Creativity and education literature highlights a series of creative pedagogies, that is, teaching practices which contribute to the development of students’ creativity. In a review of 210 pieces of educational research, Davies et al. [ 29 ] mentioned the flexible use of space and time, the study outside the classroom, collaborative and game-based learning approaches, as well as respectful relationships, non-prescriptive planning and the participation of educators as learners in the classroom activities.

Cremin and Barnes [ 30 ] outlined similar characteristics, i.e. an agency-oriented ethos, multimodal methodologies, exploration and discovery, risk-taking, tolerance of ambiguity and uncertainty and safe and non-judgemental environments. In this line, Sawyer [ 31 ] considers the possibility to try before getting it right and the use of failure as a positive learning factor. The author also considers collaborative and improvisational practices which allow students for externalising their understandings and reflecting on their learning processes.

Barajas and Frossard [ 32 ] proposed a set of four main creative pedagogies, each one characterised by different components: (a) learner-centred approaches (matching curricular objectives with students’ interests, making learning relevant and engaging, encouraging students’ ownership and problem-solving, value learning processes above outcomes so to promote students’ reflection on their learning trajectory), (b) open-ended ethos (providing space for uncertainty, exploration and spontaneity in a safe classroom environment), (c) synergistic collaboration (rich collaborative practices based on joint problem-solving and collective decision-making) and (d) knowledge connection (linking content to real-life situations, bridging different domains and disciplines and placing knowledge in a wider context).

3. Digital creativity in education: a proposal framework

Technological devices have entered all aspects of our everyday life [ 33 ]. In this digital society, the concept of creativity is being rethought. Indeed, the affordances of technologies may have a strong influence on creative processes and achievements. As mentioned by Loveless [ 34 ], ‘digital technologies can be tools which afford learners the potential to extend or enhance their abilities, allow users to create novel ways of dealing with tasks which might then change the nature of the activity itself, or provide limitations and structure which influence the nature and boundaries of the activity’ (p. 64). Nevertheless, understanding the interplay between digital and creative yet appears as a challenge, and the two are often studied as separate domains [ 4 ].

As a first step to bridge this gap, we propose the following definition of digital creativity, as applied to education (based on [ 22 , 25 ]): ‘purposive imaginative activity, mediated by digital technologies, generating outcomes that are original and valuable in relation to the learner’. As applied to education, digital creative teaching would consist of applying digital technologies with the aim to support creative pedagogies, that is, learner-centred approaches, open-ended ethos, synergistic collaboration and knowledge connection.

The following sections propose pedagogical theories and digital tools which may support the development of digital creativity in the classroom.

3.1 Pedagogical underpinnings

To our view, four pedagogical theories are particularly suitable to the application of digital creative teaching practices, namely, experiential education, critical pedagogy, constructivism and constructionism.

3.1.1 Experiential education

This movement questioned the pedagogical assumptions of its time, to which education relates to an accumulation of knowledge, in favour of active student-centred methodologies based on learning by doing and problem-based learning. To this view, learners build knowledge on the basis of the present experience and the active interaction with their environment [ 35 , 36 ].

3.1.2 Critical pedagogy

This philosophy and social movement denounces the ‘banking concept of education’ which consists of simply depositing knowledge in a decontextualised manner [ 37 ]. At the contrary, Freire promoted the importance of developing learners’ critical awareness towards the society and viewed education as a path to empowerment and emancipation. In this line, education should directly connect to meaningful problem-solving [ 38 ].

3.1.3 Constructivism

This influential paradigm considers knowledge as an experience that is developed by interacting with the world on the basis of prior knowledge. Hence, students are not passive recipients of knowledge. Rather, they make sense of the world by actively building and transforming meaning [ 39 ]; teachers become facilitators who guide students towards processing information through active exploration. From this perspective, every learning process is creative, as learners create their own meaning as they attempt to understand the world. As stated by Craft [ 40 ], ‘in a constructivist frame, learning and creativity are close, if not identical’ (p. 61).

3.1.4 Constructionism

Influenced by Freire and Piaget, Papert elaborated the theory of constructionism. He shares Freire’s endeavour to free the latent potential of students, by creating learning environments which connect to their passions [ 38 ]. Building on constructivism, constructionism argues that learning better occurs when students make and share tangible artefacts [ 41 ]. Hence, this theory is directly related to the maker and digital making movements.

Papert pioneered the educational use of digital technologies. More than information and communication devices, he considers technologies as powerful educational tools which allow students for concretising and expressing their ideas by designing, building and engineering. Constructionist learning environments are usually not based on a fixed curriculum. Rather, students use technology to build their own projects, while teachers act as facilitators of the process [ 38 ]. Hence, learners become designers. The constructionist view highlights the importance of social participation in the knowledge construction process and considers making as an inherently social activity, through which learners design artefacts that are of relevance to a larger community [ 42 ].

3.2 Digital tools for creativity

We suggest the following tools and educational strategies which may support digital creative teaching activities.

3.2.1 Manipulative technologies

Manipulatives, in the context of education, are physical tools that engage students in hands-on learning. Based on the constructivist theories, the manipulation (i.e. organisation, combination, comparison, etc.) of objects, such as blocks, figures and puzzles, is central to the learning process, as it stimulates multisensory experience. Commonly, manipulatives are used to teach STEAM to young students and to bring fun to the learning process [ 43 ]. Recent studies show a high level of acceptance of digital manipulatives by teachers and students, as well as a positive impact on learning (e.g. [ 44 ]).

For example, Magic Blocks [ 45 ] are RFID-tagged logical blocks which children can manipulate in order to perform educational tasks set by a real or a virtual teacher, to stimulate learning of mathematical and logics concepts. LittleBits 1 are small electronic objects, each one with a distinct function (motion, light, sound, sensor, etc.) that easily fits to each other through magnets, used to create electronic circuits. They stimulate the inventive nature of children to create numberless projects while they learn not only logic, maths and electronics but also product design, prototyping and entrepreneurship. Furthermore, digital manipulatives stimulate a makers attitude, turning students into active creators. Learning in a makers environment provide opportunities for disrupting students’ conventional practices of invention, exploring through play, failure, risk-taking and refiguring creation as remix and craft [ 46 ].

Virtual manipulatives, such as Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2 Shodor Interactivate Activities 3 and GeoGebra, 4 completely substitute the physical elements. Empirical studies show that virtual manipulatives encourage creativity and increase the variety of solutions that students encounter [ 46 ], which is in line with the constructivist theory.

Cubelets 5 and Robo Wunderkind 6 enable young children to design and construct robots through manipulatives—mountable blocks that contain the functions of a robot (a switch, a motor, a sensor, etc.). These tools demonstrated to positively change students’ attitude towards STEM and computer science [ 48 ], as well as to foster critical thinking skills [ 49 ].

3.2.2 Educational robotics

Educational robotics uses tangible materials to teach a variety of topics, including STEM, literacy, social studies, dance, music and art [ 50 ]. Such teaching strategy enhances students’ learning experience through hands-on/mind-on activities integrated with technology. Nowadays, a large number of educational robotics tools are available on the market, including LEGO WeDo 7 and LEGO Mindstorms, 8 mBot, 9 Bee-Bot, 10 Ozobot 11 and Dash and Dot. 12 For the younger learners (age below 6 years) educational robotics often focuses on learning the basic programming principles, simple logics and mathematics concepts. Commonly, the creation of both hardware and software parts of a robot encourages children to think imaginatively, stimulates them to analyse situations and applies critical thinking in solving real-world problems.

Ina addition, robots can be involved in teaching and learning social skills [ 51 ]. Indeed, robotics activities are usually organised in a collaborative manner, with a small number of students working together to achieve the proposed objectives [ 52 ]. Hence, teamwork and cooperation are an integral part of any robotics project: students learn to express their ideas and listen to those of their peers; all can offer arguments and reach conclusions jointly. Students focus on resolving problems for achieving the goals of their projects and learn from their errors on the way.

3.2.3 Game design and coding

Since Papert first introduced the Logo programming language and the ‘Logo turtle’, coding and developing computational thinking skills have become more and more important in today’s world and particularly in education [ 53 ]. Mass acceptance is enabled by the availability of programming tools which are appropriate for younger learners. Indeed, several visual programming languages using puzzle-like blocks appeared in recent years, such as Scratch 13 , Kodu 14 and Alice. 15 Students focus on learning programming concepts and practise a variety of skills [ 54 ], instead of solving syntax problems. Those programming environments, when appropriately integrated in teaching practices, promote exploration, risk-taking and autonomous learning, as well as increase students’ motivation [ 55 ] and spark students’ imagination [ 56 ].

3.3 Digital creative pedagogies (DCP)

Learning environments refer to both the physical and organisational aspects of creativity at stage. Among other components, creative learning environments promote exploration and discovery and present few constraints in terms of space and time, as well as provide a safe and non-judgemental climate.

Teaching strategies refer to the approaches and methodologies used by the teacher to reach specific pedagogical objectives. For example, problem-based learning, project-based learning and inquiry-based learning allow for exploring scientific phenomena by fostering students’ curiosity. Usually, inquiry processes apply a cycle of learning actions, which do not necessarily occur in a linear sequence, that is, asking questions, proposing hypotheses, investigating those hypotheses, generating new knowledge, discussing results, presenting evidences and reflecting on emerging solutions. This open-ended process engages students in creative problem-solving and evidence-based reasoning. Students learn how to formulate problems into key questions so to get the best possible answers and propose creative solutions.

Teacher-student interactions constitute an essential factor to provide rich learning processes. Indeed, learning occurs in social contexts, and creativity emerges with respectful exchanges which promote risk-taking, tolerate uncertainty, see failure as positive and promote students’ autonomy.

Digital tools are instruments which mediate the learning process; they aim to facilitate learners’ expression, as well as to extend their possibilities and abilities while carrying a task. Digital tools also enhance manipulation, experimentation or risk-taking, which are key aspects of creativity. As argued earlier, manipulative technologies, educational robotics tools and game design/coding environments are particularly suitable to support digital creative practices.

Table 1 summarises the characteristic components of DCP and their corresponding dimensions.

Table 1.

The components of digital creative pedagogies (DCP).

4. Conclusions

This chapter aimed to embed educational creativity in today’s digital society. Based on the seminal theories of creativity and creative education, we proposed an innovative framework for applying creative teaching practices mediated by digital technologies: in the light of constructivist and constructionist approaches, we suggested a series of digital tools which are particularly suitable to the emergence of creativity, i.e. manipulative technologies, educational robotics and game design and coding. Furthermore, we shaped the concept of digital creative pedagogies (DCP) and established a set of characteristic components of teaching practices which contribute to the development of students’ creativity. We make the assumption that the application of this framework allows for engaging students in new, personally meaningful processes and in the creation of original outcomes, as well as for enhancing learning in any curricular subject.

The proposed framework highlights four different dimensions of DCP, namely, learning environment, teaching strategies, teacher-student interactions and digital tools. Each of these dimensions is equally important for ensuring the emergence of creative learning processes. Indeed, the use of adequate teaching strategies would allow for fully exploiting the affordances of the selected digital tools. Furthermore, a safe and flexible learning environment, paired with supportive interactions between teachers and learners (and among learners themselves), would create the necessary conditions and balance so that the learning activity takes on its full meaning.

The chapter contributes to linking two key educational research trends: one on creativity and the other on digital technologies. It provides educational practitioners and researchers with concrete strategies and tools for shaping and applying creativity in the digital classroom.

- 1. Craft A. Childhood, possibility thinking and wise, humanising educational futures. International Journal of Educational Research. 2013; 61 :126-134. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijer.2013.02.005

- 2. Beghetto RA. Creativity in the classroom. In: Kaufman JC, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010. pp. 447-463

- 3. European Commission. Lifelong Learning for Creativity and Innovation. A Background Paper. Ljubljana: Slovenian EU Council Presidency; 2008. 19 p

- 4. Sefton-Green J, Brown L. Mapping Progression into Digital Creativity—Catalysts and Disconnects: A State of the Art Report for the Nominet Trust. Oxford: Nominet Trust; 2014. 147 p

- 5. Ferrari A, Cachia R, Punie Y. ICT as a driver for creative learning and innovative teaching. In: Villalba E, editor. Measure Creativity: Proceedings for the Conference, "Can Creativity be Measured?"; Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2009. pp. 345-368

- 6. Beghetto RA, Kaufman JC. Classroom contexts for creativity. High Ability Studies. 2014; 25 (1):53-69. DOI: 10.1080/13598139.2014.905247

- 7. Lin YS. Fostering creativity through education: Conceptual framework of creative pedagogy. Creative Education. 2011; 2 (3):149-155. DOI: 10.4236/ce.2011.23021

- 8. European Commission. Initial Teacher Education in Europe: An Overview of Policy Issues. Brussels: European Commission; 2014. 21 p

- 9. Sternberg RJ, Lubart TI. Handbook of Creativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. 493 p

- 10. Csikszentmihalyi M. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. New York: Harper Perennial; 1996. 480 p. DOI: 10.1080/10400419.1996.9651177

- 11. Rhodes M. An analysis of creativity. Phi Delta Kappan. 1961; 42 :305-310

- 12. Howard TJ, Culley SJ, Dekoninck E. Describing the creative design process by the integration of engineering design and cognitive. Design Studies. 2008; 29 (2):160-180. DOI: 10.1016/j.destud.2008.01.001

- 13. Amabile T. The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983; 45 (2):357-376. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.357

- 14. Sternberg RJ, Lubart TI. An investment theory of creativity and its development. Human Development. 1991; 34 (1):1-31. DOI: 10.1159/000277029

- 15. Simonton DK. Origins of genius: Darwinian perspectives on creativity. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. 320 p. ISBN: 978-0195128796

- 16. Runco MA, Pagnani AR. Psychological research on creativity. In: Sefton-Green J, Thomson P, Jones K, Bresler L, editors. The Routledge International Handbook of Creative Learning. London: Routledge; 2011. pp. 63-71

- 17. Amabile T, Gryskiewicz N. The creative environment scales: The work environment inventory. Creativity Research Journal. 1989; 2 (4):231-254. DOI: 10.1080/10400418909534321

- 18. Runco MA. Creativity. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004; 55 :657-687. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141502

- 19. Craft A. Little c creativity. In: Craft A, Jeffrey R, Leibling M, editors. Creativity in Education. London: Continuum; 2001. pp. 45-61

- 20. Kaufman JC, Beghetto RA. Beyond big and little: The four c model of creativity. Review of General Psychology. 2009; 13 (1):1-12. DOI: 10.1037/a0013688

- 21. Sawyer RK. Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. p. 568. ISBN: 9780199737574

- 22. NACCCE. All our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education. London: Department for Education and Employment; 1999. 242 p

- 23. Villalba E. On Creativity. Towards an Understanding of Creativity and Its Measures. JRC Scientific and Technical Reports, EUR 23561. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2008. 40 p. ISBN: 978-92-79-10647-7

- 24. Amabile T, Pillemer J. Perspectives on the social psychology of creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior. 2012; 46 (1):3-15. DOI: 10.1002/jocb.001

- 25. Cremin T, Clack J, Craft A. Creative Little Scientists: Enabling Creativity through Science and Mathematics in Preschool and First Years of Primary Education. D2.2. Conceptual Framework: Literature Review of Creativity in Education. Athens: Ellinogermaniki Agogi; 2012. 171 p

- 26. Loveless A. Literature review in creativity, new technologies and learning. Bristol: NESTA Futurelab Series; 2002. 36 p. ISBN: 0-9544695-4-2

- 27. Ferrari A, Cachia R, Punie Y. Innovation and creativity in education and training in the EU member states: Fostering creative learning and supporting innovative teaching. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. 2009. 54 p

- 28. Craft A, Cremin T, Hay P, Clack J. Creative primary schools: developing and maintaining pedagogy for creativity. Ethnography and Education. 2014; 9 (1):16-34. DOI: 10.1080/17457823.2013.828474

- 29. Davies D, Jindal-Snape D, Collier C, Digby R, Hay P, Howe A. Creative environments for learning in schools. Thinking Skills and Creativity. 2013;8:80-91. DOI: 10.1016/j.tsc.2012.07.004

- 30. Barajas M, Frossard F. Mapping creative pedagogies in open wiki learning environments. Education and Information Technologies. 2018; 23 (3):1403-1419

- 31. Cremin T, Barnes J. Creativity and creative teaching and learning. In: Cremin T, Arthur J, editors. Learning to Teach in the Primary School (3rd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. 2014. p. 467-481

- 32. Sawyer RK. A call to action: the challenges of creative teaching and learning. Teachers College Record. 2011; 117 :1-34

- 33. Lee MR, Chen TT. Digital creativity: Research themes and framework. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;42(1):12-19. DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.001

- 34. Loveless A. Creative learning and new technology? A provocation paper. In: Sefton-Green J, editor. Creative learning. London: Creative Partnerships. 2008. p. 61-72

- 35. Dewey J. Experience and Education. New York: Collier; 1938. 91 p. ISBN: 0684838281

- 36. Kolb DA. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1984. 390 p. ISBN: 9780132952613

- 37. Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Seabury Press; 1974. 186 p. ISBN: 0816491321

- 38. Blikstein P. Digital Fabrication and ’Making’ in Education: The Democratization of Invention. In: Walter-Herrmann J, Büching C, editors. FabLabs: Of Machines, Makers and Inventors. Bielefeld: Transcript Publishers. 2013. p 203-222

- 39. Jordan A., Carlile O, Stack A. Approaches to Learning: A Guide for Teachers: A Guide for Educators. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education; 2008. 296 p. ISBN: 0335226701

- 40. Craft A. Creativity in schools: tensions and dilemmas. London: Routledge; 2005. 224 p. ISBN: 0415324157

- 41. Ackermann E, Gauntlett D, Wolbers T, Weckstrom C. Defining systematic creativity in the digital realm. Billund: LEGO Learning Institute; 2009. 58 p

- 42. Kafai B, Burke Q. Connected Gaming: What Making Video Games Can Teach Us about Learning and Literacy. Cambridge: MIT press; 2016. 224 p. ISBN: 9780262035378

- 43. Moyer PS. Are we having fun yet? How teachers use manipulatives to teach mathematics. Educational Studies in mathematics. 2001;47(2):175-197. DOI: 10.1023/A:1014596316942

- 44. Miglino O, Di Fuccio R, Di Ferdinando A, Barajas M, Trifonova A, Ceccarani P, et al. BlockMagic: Enhancing traditional didactic materials with smart objects technology. In: Proceedings of the International Academic Conference on Education, Teaching and E-learning. Prague: MAC Prague consulting Ltd; 2013. ISBN: 978-80-905442-1-5

- 45. Di Ferdinando A, Di Fuccio R, Ponticorvo M, Miglino O. Block magic: a prototype bridging digital and physical educational materials to support children learning processes. In: Uskov V, Howlett R, Jain L, editors. Smart Education and Smart e-Learning. London: Springer. 2015. p. 171-180. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-56538-5

- 46. Faris, M, Blick A, Labriola J, Hankey L, May J, Mangum R. Building Rhetoric One Bit at a Time: A Case of Maker Rhetoric with littleBits. 2018. Available from: http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/22.2/praxis/faris-et-al/ [Accessed: 2018-07-19]

- 47. Moyer-Packenham, P, Westenskow A. Effects of virtual manipulatives on student achievement and mathematics learning. International Journal of Virtual and Personal Learning Environments. 2013; 4 (3):35-50. DOI: 10.4018/jvple.2013070103

- 48. Correll, N, Wailes C, Slaby S. A One-hour curriculum to engage middle school students in robotics and computer science using Cubelets. In: Ani Hsieh M, Chirikjian G, editors. Distributed Autonomous Robotic Systems. Berlin: Spinger; 2014 p. 165-176

- 49. Gross M, Veitch C. Beyond top down: Designing with cubelets. Tecnologias, Sociedade e Conhecimento. 2013; 1 (1):150-164

- 50. Eguchi, A. Robotics as a learning tool for educational transformation. In: Proceeding of 4th International Workshop Teaching Robotics, Teaching with Robotics & 5th International Conference Robotics in Education. 18 July 2014; Padova. p. 27-34

- 51. Ray B, Faure C. Mini-robots as smart gadgets: Promoting active learning of key K-12 social science skills. In: Ali Khan A, Umair S, editors. Handbook of Research on Mobile Devices and Smart Gadgets in K-12 Education. Hershey: IGI Global; 2018. pp. 16-31. DOI: 10.4018/978-1-5225-2706-0.ch002

- 52. Denis B, Hubert S. Collaborative learning in an educational robotics environment. Computers in Human Behavior. 2001; 17 (5-6): DOI: 465-480. 10.1016/S0747-5632(01)00018-8

- 53. Bers MU. Coding as a Playground: Programming and Computational Thinking in the Early Childhood Classroom. London: Routledge; 2017. 196 p. ISBN: 978-1138225626

- 54. Lye S, Koh J. Review on teaching and learning of computational thinking through programming: What is next for K-12?. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014; 41 :51-61. DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.012

- 55. Fowler A, Cusack B. Kodu game lab: improving the motivation for learning programming concepts. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Foundations of Digital Games; 28 June-01 July 01 2011; Bordeaux. p. 238-240

- 56. Tsur, M, Rusk N. Scratch Microworlds: Designing project-based introductions to coding. In: Proceedings of the 49th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education; 21-24 February 2018; Baltimore. p. 894-899

- https://www.littlebits.com/

- http://demonstrations.wolfram.com/

- http://www.shodor.org/interactivate/activities/

- https://www.geogebra.org/

- https://www.modrobotics.com/

- https://robowunderkind.com/en/

- https://education.lego.com/en-us/support/wedo

- https://education.lego.com/en-us/support/mindstorms-ev3

- http://www.makeblock.com/mbot

- https://www.bee-bot.us/bee-bot.html

- http://ozobot.com/

- https://www.makewonder.com/dash

- https://scratch.mit.edu/

- https://www.kodugamelab.com/

- https://www.alice.org/

© 2018 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Active learning.

Published: 02 October 2019

By Saied Bishara

1585 downloads

By Emete Toros and Mehmet Altinay

1042 downloads

By Sílvio Manuel da Rocha Brito

1337 downloads

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Proposing a framework for evaluating digital creativity in social media and multimedia-based art and design education

Global Journal of Arts Education

The usage of emerging social and digital applications is growing rapidly among the current generation of students and academics, and researchers started exploring their effectiveness in enhancing students’ creativity. However, examining the most effective criteria for evaluating digital-media-enhanced creativity in art and design still needs further exploration. This pilot study seeks to develop a framework to assess students’ creativity and another framework to assess the effectiveness of multimedia-based teaching approaches in art and design educational contexts. Sixteen design instructors participated in a survey, which aimed to identify their experiences with multimedia-based pedagogy as a potentially effective approach in fostering students’ creativity as well as educators’ innovation in teaching. The paper identifies and ranks the criteria, which they thought are effective in assessing digitally-stimulated creativity in each field of graphic design. The ultimate goal is to pro...

Related Papers

International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET)

Yasmina Zaki

Rapidly growing technological advances in big data, cloud computing, social media, artificial intelligence, virtual reality and digital media have led many educators to embark upon the pursuit and deployment of various digital tools in the classroom. They started implementing a technology-centered educational system in order to expand their pedagogical approaches and increase the possibilities of creatively putting ideas together and innovatively conveying their knowledge to their students. In this paper, we explore the convergence of creativity, technology, with art and design education, and we advocate the use of digital tools and repurposing of social media applications to support creative thinking. We discuss existing multimedia-based classroom practices that might encourage student creativity and suggest new forms and applications of technology aimed at providing the reflective teacher with more effective and efficient strategies to cultivate creativity while teaching art, desi...

Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education

Dr. Kuo-Kuang Fan

Pandu Dian Samaran

International Journal for Infonomics

vesna maljkovic

Active Learning [Working Title]

Anna Trifonova

Gene Lim Jing Yi

Social media is nowadays broadly used by young people. Majority of the young people are with social media sites as it enable them to stay connected with people around the globe anywhere and anytime. The features of social media sites where it allows different forms of content to be shared attract young people's attention and transform ways of communication and interaction between their users. Consequently, majority of higher learning institution are starting to use social media for teaching and learning. This paper explores how the creative arts students are engage in the social media for learning and creative artwork development. Using a mixed methodology, this study used a sample of 300 students from public and private universities and colleges through a questionnaire focusing on the use of social media for learning and creative artwork development specifically in communication and collaboration, information management, learning and problem solving as well as meaningful partic...

Dr. Salman Alhajri

Purpose: this paper identifies the meanings of creativity from socio-cultural perspectives within the specific context of the graphic design discipline. It tries to identify what is ‘creative’ as it understood, discussed, and agreed on most creative design literatures. It is argued that creativity in graphic design could be measurable and, therefore, identifying instruments of measurement will lead to the development of new methodologies and perspectives in teaching graphic design, therefore, the methodology is based on theoretical study. Findings: the paper has outlined the best approaches for studying the development of creativity in graphic design students within a specific socio-cultural context. It has also illustrated the importance of identifying the meaning of creativity as is it understood in graphic industries within a specific socio-cultural context. An example studies that discussed how creativity should be treated, studied and measured has been mentioned on this article. keywords: creative design within a specific socio-cultural context, creativity in graphic design, teaching creative design, graphic design problems Citation: Alhajri, S.A., 2010, Investigating the nature of creativity as it is understood in graphic design industries, conference proceedings of The 1st International Conference on Design Creativity, Kobe, Japan.

DEStech Transactions on Social Science, Education and Human Science

Samiati Andriana

kathryn coleman

Creativity, both as a professional capability and as a personal attribute, is acknowledged as an important dimension of education for a fast-changing world, relevant to future practice in the professions and for learners and teachers. New social media tools, which place creation, publication and critique in the hands of web users, have been recognised as having a role in democratising creativity, making the means of production and distribution accessible to most of the developed world. Using these tools to facilitate learning activities in higher education can promote creativity and many other related capabilities: digital literacy, independent learning, collaboration and communication skills, and critical thinking. It requires creativity on the part of teachers to develop and manage learning environments and tasks that are not traditional and may be quite experimental. This paper asks some university teachers who are innovating their teaching by using social media to reflect on how...

Resalat Prodhan

Creativity and Art Education Gaps Between Theories and Practices

- Jill Journeaux 4 &

- Judith Mottram 5

- First Online: 01 January 2015

2547 Accesses

1 Citations

Part of the book series: Creativity in the Twenty First Century ((CTFC))

Theories of creativity from different disciplines map onto teaching strategies within the fine art field. In particular, the outcomes of historical studies by psychologists and experimental studies within cognitive science have significant resonance with some long-standing methods of teaching artists. Through a series of interviews with experienced teachers of studio art in the UK university context, and analysis of written material to support teaching, this chapter recognizes the need for a more systematic exploration of how creative thinking may have been embedded in the teaching of artists. We identify the presence of practical strategies, field knowledge, artistic identity, and the importance of ‘space’ within the accounts of teaching and the documents considered. We note that notions of identity and space are not clearly present within existing models of creativity, but aspects of them reflect tolerance for ambiguity. We conclude by reflecting that this space within conceptions of fine art education is a gap that needs attention and that the field that generates the creative practitioners of the future should understand creativity.

- Practical Strategy

- Creative Industry

- Field Knowledge

- Quality Assurance Agency

- Creative Practice

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context . Boulder, CO: Westfield Press.

Google Scholar

Ascott, R. (1964). A groundcourse for art in education. In F. Allen (2011) (Ed.), Documents of contemporary art 18 (pp. 51–53). London: Whitechapel Gallery/MIT Press.

Austerlitz, N. (2007). Mind the gap: Expectations, ambiguity and pedagogy within art and design higher education. In L. Drew (Ed.), The student experience in art and design higher education: drivers for change (pp. 127–148). Cambridge, UK: Jill Rogers Associates.

Blair, B. (2008). Redefining the project. In L. Drew (Ed.), The student experience in art and design higher education: Drivers for change (pp. 81–83). Cambridge, UK: Jill Rogers Associates.

Boden, M. (1990). The creative mind: myths and mechanisms . London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

Cornock, S. (1984). Learning strategies in fine art. Journal of Art and Design Education , 3 (2).

Cornock, S. (1985). Forms of knowing in the study of the fine arts. In D. G. Russell, D. F. Marks, & J. T. E. Richardson (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2nd international imagery conference, Wales, 1985 . Human Performance Associates: Dunedin.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: flow and the psychology of discovery and invention . New York: HarperPerennial. (1st published by HarperCollins, 1996.).

Dickie, G. (1971). Aesthetics, an introduction . New York: Pegasus.

Elkins, J. (2001). Why art cannot be taught . Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Ericcson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Romer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review , 100 (3), 363–406.

Fortnum, R., & Pybus, C. (2014). Editorial. Journal of Art , Design and Communication in Higher Education , 13 (2).

Hetherington, P. (Ed.). (1994). Artists in the 1990s: Their education and values . London: Tate Gallery Publications.

Hiller, S. (1996). An artist on art education. In P. Hetherington (Ed.), Issues in art and education: Aspects of the fine art curriculum . London: Tate Gallery Publications.

Itten, J. (1975). Design and form: The basic course at the Bauhaus and later (revised ed.). London: Wiley/Thames & Hudson.

Joint report of the National Advisory Council on Art Education and the National Council for Diplomas in Art and Design (The Second Coldstream Report). (1970). The structure of art and design education in the further education sector . London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office.

Landry, C. (1995). The creative city: A toolkit for urban innovators . Abingdon: Routledge.

Lubart, T. I., & Sternberg, R. J. (1995). An investment approach to creativity. In S. M. Smith, T. B. Ward & R. A. Finke (Eds.), The creative cognition approach (pp. 260–302). Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Milner, M. (1950). On not being able to paint . London: Heinemann.

National Association for Fine Art Education (NAFAE). (2014). AGM and national symposium 2014: 45 years of fine art education: Drawing the line? http://www.nafae.org.uk/news-and-events/nafae-agm/agm-2014/ Accessed 25 May 2014.

Nochlin, L. (1971). Why have there been no great women artists? Art News , 69, 22–39.

Pollock, G. (1996). Feminist perspectives in fine art education. In P. Hetherington (Ed.), Issues in art and education: Aspects of the fine art curriculum . London: Tate Gallery Publications.

Quality Assurance Agency (2008). Subject benchmark statement: Art and design . http://www.qaa.ac.uk/en/Publications/Documents/Subject-benchmark-statement—Art-and-design-.pdf . Accessed 19 June 2015.

Quinn, M. (2012). Utilitarianism and the art school in nineteenth-century Britain . London: Pickering and Chatto.

Report of a Joint Committee of the National Advisory Council on Art Education (The First Coldstream Report). (1960). First report of the national advisory council on art education . London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office.

Richardson, M. (1948). Art and the child . London: University of London Press.

Robertson, C. (2008). The invention of Annibale Carracci . Milan: Silvana Editoriale Spa.

Rogers, A., & Kilgallon, S. (2009). Making space to create. In Dialogues in Art and Design: Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Group for Learning in Art and Design ( GLAD ) (pp. 182–189). Brighton, UK: ADM HEA.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action . New York: Basic Books.

Simonton, D. K. (1975). Sociocultural context of individual creativity: A transhistorical time-series analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 32 , 1119–1133.

Simonton, D. K. (1977). Creative productivity, age and stress: A biographical time-series analysis of 10 classic composers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 35 , 791–804.

Smith, S. M., Ward, T. B., & Finke, R. A. (1995). The creative cognition approach . Boston: MIT Press.

Weisberg, R. W. (1999). Creativity and knowledge: A challenge to theories. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice. Learning, meaning and identity . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Williamson, B. (2013). Recent developments in British art education: ‘Nothing changes from generation to generation except the thing seen’. Visual Culture in Britain, . doi: 10.1080/14714787.2013.817845 .

Woolley, M. (2013). Making space: The past present and future of the creative environment. In H. Briit, K. Walton, & S. Wade (Eds.), Futurescan 2: Collective voices (pp. 26–33). Sheffield: The Association of Fashion Textile Courses.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Coventry University, Coventry, UK

Jill Journeaux

Royal College of Art, London, UK

Judith Mottram

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jill Journeaux .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

DEI Department, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Giovanni Emanuele Corazza

Marconi Institute for Creativity, Bologna, Italy

Sergio Agnoli

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Journeaux, J., Mottram, J. (2016). Creativity and Art Education Gaps Between Theories and Practices. In: Corazza, G., Agnoli, S. (eds) Multidisciplinary Contributions to the Science of Creative Thinking. Creativity in the Twenty First Century. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-618-8_16

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-618-8_16

Published : 31 July 2015

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-287-617-1

Online ISBN : 978-981-287-618-8

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Since the introduction of personal computers, art educators increasingly have adopted new digital technologies into their pedagogy, yet overall that adoption has been a slow process. Many teachers remain still infrequent users of technology or avoid using new learning technologies in art classrooms. It is important for art education to embrace an understanding and use of new technologies in ...

Creativity in Digital Art Education Teaching Practices. 19 Since the introduction of personal computers, art educators increasingly have adopted new digital technologies into their pedagogy, yet overall that adoption has been a slow process (Black, 2002; Browning, 2006; Degennaro & Mak, 2002-2003; Flood & Bamford, 2007; Gude, 2007; Leonard ...

Creativity is a diverse term, and in art and digital education has been variously expressed as possibility thinking, change, development, content creation, play and cognitive endeavour to touch ...