The Ongoing Challenges, and Possible Solutions, to Improving Educational Equity

- Share article

Schools across the country were already facing major equity challenges before the pandemic, but the disruptions it caused exacerbated them.

After students came back to school buildings after more than a year of hybrid schooling, districts were dealing with discipline challenges and re-segregating schools. In a national EdWeek Research Center survey from October, 65 percent of the 824 teachers, and school and district leaders surveyed said they were more concerned now than before the pandemic about closing academic opportunity gaps that impact learning for students of different races, socioeconomic levels, disability categories, and English-learner statuses.

But educators trying to prioritize equity have an uphill battle to overcome these challenges, especially in the face of legislation and school policies attempting to fight equity initiatives across the country.

The pandemic and the 2020 murder of George Floyd drove many districts to recognize longstanding racial disparities in academics, discipline, and access to resources and commit to addressing them. But in 2021, a backlash to such equity initiatives accelerated, and has now resulted in 18 states passing laws restricting lessons on race and racism, and many also passing laws restricting the rights and well-being of LGBTQ students.

This slew of Republican-driven legislation presents a new hurdle for districts looking to address racial and other inequities in public schools.

During an Education Week K-12 Essentials forum last week, journalists, educators, and researchers talked about these challenges, and possible solutions to improving equity in education.

Takeru Nagayoshi, who was the Massachusetts teacher of the year in 2020, and one of the speakers at the forum, said he never felt represented as a gay, Asian kid in public school until he read about the Stonewall Riots, the Civil Rights Movement, and the full history of marginalized groups working together to change systems of oppression.

“Those are the learning experiences that inspired me to be a teacher and to commit to a life of making our country better for everyone,” he said.

“Our students really benefit the most when they learn about themselves and the world that they’re in. They’re in a safe space with teachers who provide them with an honest education and accurate history.”

Here are some takeaways from the discussion:

Schools are still heavily segregated

Almost 70 years after the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, most students attend schools where they see a majority of other students of their racial demographics .

Black students, who accounted for 15 percent of public school enrollment in 2019, attended schools where Black students made up an average of 47 percent of enrollment, according to a UCLA report.

They attended schools with a combined Black and Latinx enrollment averaging 67 percent, while Latinx students attended schools with a combined Black and Latinx enrollment averaging 66 percent.

Overall, the proportion of schools where the majority of students are not white increased from 14.8 percent of schools in 2003 to 18.2 percent in 2016.

“Predominantly minority schools [get] fewer resources, and that’s one problem, but there’s another problem too, and it’s a sort of a problem for democracy,” said John Borkowski, education lawyer at Husch Blackwell.

“I think it’s much better for a multi-racial, multi-ethnic democracy, when people have opportunities to interact with one another, to learn together, you know, and you see all of the problems we’ve had in recent years with the rising of white supremacy, and white supremacist groups.”

School discipline issues were exacerbated because of student trauma

In the absence of national data on school discipline, anecdotal evidence and expert interviews suggest that suspensions—both in and out of school—and expulsions, declined when students went remote.

In 2021, the number of incidents increased again when most students were back in school buildings, but were still lower than pre-pandemic levels , according to research by Richard Welsh, an associate professor of education and public policy at Vanderbilt’s Peabody College of Education.

But forum attendees, who were mostly district and school leaders as well as teachers, disagreed, with 66 percent saying that the pandemic made school incidents warranting discipline worse. That’s likely because of heightened student trauma from the pandemic. Eighty-three percent of forum attendees who responded to a spot survey said they had noticed an increase in behavioral issues since resuming in-person school.

Restorative justice in education is gaining popularity

One reason Welsh thought discipline incidents did not yet surpass pre-pandemic levels despite heightened student trauma is the adoption of restorative justice practices, which focus on conflict resolution, understanding the causes of students’ disruptive behavior, and addressing the reason behind it instead of handing out punishments.

Kansas City Public Schools is one example of a district that has had improvement with restorative justice, with about two thirds of the district’s 35 schools seeing a decrease in suspensions and expulsions in 2021 compared with 2019.

Forum attendees echoed the need for or success of restorative justice, with 36 percent of those who answered a poll within the forum saying restorative justice works in their district or school, and 27 percent saying they wished their district would implement some of its tenets.

However, 12 percent of poll respondents also said that restorative justice had not worked for them. Racial disparities in school discipline also still persist, despite restorative justice being implemented, which indicates that those practices might not be ideal for addressing the over-disciplining of Black, Latinx, and other historically marginalized students.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

How far has COVID set back students?

What do anti-Jewish hate, anti-Muslim hate have in common?

How covid taught america about inequity in education.

Harvard Correspondent

Remote learning turned spotlight on gaps in resources, funding, and tech — but also offered hints on reform

“Unequal” is a multipart series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the U.S. This part looks at how the pandemic called attention to issues surrounding the racial achievement gap in America.

The pandemic has disrupted education nationwide, turning a spotlight on existing racial and economic disparities, and creating the potential for a lost generation. Even before the outbreak, students in vulnerable communities — particularly predominately Black, Indigenous, and other majority-minority areas — were already facing inequality in everything from resources (ranging from books to counselors) to student-teacher ratios and extracurriculars.

The additional stressors of systemic racism and the trauma induced by poverty and violence, both cited as aggravating health and wellness as at a Weatherhead Institute panel , pose serious obstacles to learning as well. “Before the pandemic, children and families who are marginalized were living under such challenging conditions that it made it difficult for them to get a high-quality education,” said Paul Reville, founder and director of the Education Redesign Lab at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (GSE).

Educators hope that the may triggers a broader conversation about reform and renewed efforts to narrow the longstanding racial achievement gap. They say that research shows virtually all of the nation’s schoolchildren have fallen behind, with students of color having lost the most ground, particularly in math. They also note that the full-time reopening of schools presents opportunities to introduce changes and that some of the lessons from remote learning, particularly in the area of technology, can be put to use to help students catch up from the pandemic as well as to begin to level the playing field.

The disparities laid bare by the COVID-19 outbreak became apparent from the first shutdowns. “The good news, of course, is that many schools were very fast in finding all kinds of ways to try to reach kids,” said Fernando M. Reimers , Ford Foundation Professor of the Practice in International Education and director of GSE’s Global Education Innovation Initiative and International Education Policy Program. He cautioned, however, that “those arrangements don’t begin to compare with what we’re able to do when kids could come to school, and they are particularly deficient at reaching the most vulnerable kids.” In addition, it turned out that many students simply lacked access.

“We’re beginning to understand that technology is a basic right. You cannot participate in society in the 21st century without access to it,” says Fernando Reimers of the Graduate School of Education.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

The rate of limited digital access for households was at 42 percent during last spring’s shutdowns, before drifting down to about 31 percent this fall, suggesting that school districts improved their adaptation to remote learning, according to an analysis by the UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge of U.S. Census data. (Indeed, Education Week and other sources reported that school districts around the nation rushed to hand out millions of laptops, tablets, and Chromebooks in the months after going remote.)

The report also makes clear the degree of racial and economic digital inequality. Black and Hispanic households with school-aged children were 1.3 to 1.4 times as likely as white ones to face limited access to computers and the internet, and more than two in five low-income households had only limited access. It’s a problem that could have far-reaching consequences given that young students of color are much more likely to live in remote-only districts.

“We’re beginning to understand that technology is a basic right,” said Reimers. “You cannot participate in society in the 21st century without access to it.” Too many students, he said, “have no connectivity. They have no devices, or they have no home circumstances that provide them support.”

The issues extend beyond the technology. “There is something wonderful in being in contact with other humans, having a human who tells you, ‘It’s great to see you. How are things going at home?’” Reimers said. “I’ve done 35 case studies of innovative practices around the world. They all prioritize social, emotional well-being. Checking in with the kids. Making sure there is a touchpoint every day between a teacher and a student.”

The difference, said Reville, is apparent when comparing students from different economic circumstances. Students whose parents “could afford to hire a tutor … can compensate,” he said. “Those kids are going to do pretty well at keeping up. Whereas, if you’re in a single-parent family and mom is working two or three jobs to put food on the table, she can’t be home. It’s impossible for her to keep up and keep her kids connected.

“If you lose the connection, you lose the kid.”

“COVID just revealed how serious those inequities are,” said GSE Dean Bridget Long , the Saris Professor of Education and Economics. “It has disproportionately hurt low-income students, students with special needs, and school systems that are under-resourced.”

This disruption carries throughout the education process, from elementary school students (some of whom have simply stopped logging on to their online classes) through declining participation in higher education. Community colleges, for example, have “traditionally been a gateway for low-income students” into the professional classes, said Long, whose research focuses on issues of affordability and access. “COVID has just made all of those issues 10 times worse,” she said. “That’s where enrollment has fallen the most.”

In addition to highlighting such disparities, these losses underline a structural issue in public education. Many schools are under-resourced, and the major reason involves sources of school funding. A 2019 study found that predominantly white districts got $23 billion more than their non-white counterparts serving about the same number of students. The discrepancy is because property taxes are the primary source of funding for schools, and white districts tend to be wealthier than those of color.

The problem of resources extends beyond teachers, aides, equipment, and supplies, as schools have been tasked with an increasing number of responsibilities, from the basics of education to feeding and caring for the mental health of both students and their families.

“You think about schools and academics, but what COVID really made clear was that schools do so much more than that,” said Long. A child’s school, she stressed “is social, emotional support. It’s safety. It’s the food system. It is health care.”

“You think about schools and academics” … but a child’s school “is social, emotional support. It’s safety. It’s the food system. It is health care,” stressed GSE Dean Bridget Long.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

This safety net has been shredded just as more students need it. “We have 400,000 deaths and those are disproportionately affecting communities of color,” said Long. “So you can imagine the kids that are in those households. Are they able to come to school and learn when they’re dealing with this trauma?”

The damage is felt by the whole families. In an upcoming paper, focusing on parents of children ages 5 to 7, Cindy H. Liu, director of Harvard Medical School’s Developmental Risk and Cultural Disparities Laboratory , looks at the effects of COVID-related stress on parent’ mental health. This stress — from both health risks and grief — “likely has ramifications for those groups who are disadvantaged, particularly in getting support, as it exacerbates existing disparities in obtaining resources,” she said via email. “The unfortunate reality is that the pandemic is limiting the tangible supports [like childcare] that parents might actually need.”

Educators are overwhelmed as well. “Teachers are doing a phenomenal job connecting with students,” Long said about their performance online. “But they’ve lost the whole system — access to counselors, access to additional staff members and support. They’ve lost access to information. One clue is that the reporting of child abuse going down. It’s not that we think that child abuse is actually going down, but because you don’t have a set of adults watching and being with kids, it’s not being reported.”

The repercussions are chilling. “As we resume in-person education on a normal basis, we’re dealing with enormous gaps,” said Reville. “Some kids will come back with such educational deficits that unless their schools have a very well thought-out and effective program to help them catch up, they will never catch up. They may actually drop out of school. The immediate consequences of learning loss and disengagement are going to be a generation of people who will be less educated.”

There is hope, however. Just as the lockdown forced teachers to improvise, accelerating forms of online learning, so too may the recovery offer options for educational reform.

The solutions, say Reville, “are going to come from our community. This is a civic problem.” He applauded one example, the Somerville, Mass., public library program of outdoor Wi-Fi “pop ups,” which allow 24/7 access either through their own or library Chromebooks. “That’s the kind of imagination we need,” he said.

On a national level, he points to the creation of so-called “Children’s Cabinets.” Already in place in 30 states, these nonpartisan groups bring together leaders at the city, town, and state levels to address children’s needs through schools, libraries, and health centers. A July 2019 “ Children’s Cabinet Toolkit ” on the Education Redesign Lab site offers guidance for communities looking to form their own, with sample mission statements from Denver, Minneapolis, and Fairfax, Va.

Already the Education Redesign Lab is working on even more wide-reaching approaches. In Tennessee, for example, the Metro Nashville Public Schools has launched an innovative program, designed to provide each student with a personalized education plan. By pairing these students with school “navigators” — including teachers, librarians, and instructional coaches — the program aims to address each student’s particular needs.

“This is a chance to change the system,” said Reville. “By and large, our school systems are organized around a factory model, a one-size-fits-all approach. That wasn’t working very well before, and it’s working less well now.”

“Students have different needs,” agreed Long. “We just have to get a better understanding of what we need to prioritize and where students are” in all aspects of their home and school lives.

“By and large, our school systems are organized around a factory model, a one-size-fits-all approach. That wasn’t working very well before, and it’s working less well now,” says Paul Reville of the GSE.

Already, educators are discussing possible responses. Long and GSE helped create The Principals’ Network as one forum for sharing ideas, for example. With about 1,000 members, and multiple subgroups to address shared community issues, some viable answers have begun to emerge.

“We are going to need to expand learning time,” said Long. Some school systems, notably Texas’, already have begun discussing extending the school year, she said. In addition, Long, an internationally recognized economist who is a member of the National Academy of Education and the MDRC board, noted that educators are exploring innovative ways to utilize new tools like Zoom, even when classrooms reopen.

“This is an area where technology can help supplement what students are learning, giving them extra time — learning time, even tutoring time,” Long said.

Reimers, who serves on the UNESCO Commission on the Future of Education, has been brainstorming solutions that can be applied both here and abroad. These include urging wealthier countries to forgive loans, so that poorer countries do not have to cut back on basics such as education, and urging all countries to keep education a priority. The commission and its members are also helping to identify good practices and share them — globally.

Innovative uses of existing technology can also reach beyond traditional schooling. Reimers cites the work of a few former students who, working with Harvard Global Education Innovation Initiative, HundrED , the OECD Directorate for Education and Skills , and the World Bank Group Education Global Practice, focused on podcasts to reach poor students in Colombia.

They began airing their math and Spanish lessons via the WhatsApp app, which was widely accessible. “They were so humorous that within a week, everyone was listening,” said Reimers. Soon, radio stations and other platforms began airing the 10-minute lessons, reaching not only children who were not in school, but also their adult relatives.

Share this article

You might like.

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

An economist, a policy expert, and a teacher explain why learning losses are worse than many parents realize

Researchers scrutinize various facets of these types of bias, and note sometimes they both reside within the same person.

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Excited about new diet drug? This procedure seems better choice.

Study finds minimally invasive treatment more cost-effective over time, brings greater weight loss

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 04 August 2023

On the promise of personalized learning for educational equity

- Hanna Dumont ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2910-6311 1 &

- Douglas D. Ready 2

npj Science of Learning volume 8 , Article number: 26 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5201 Accesses

3 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

Students enter school with a vast range of individual differences, resulting from the complex interplay between genetic dispositions and unequal environmental conditions. Schools thus face the challenge of organizing instruction and providing equal opportunities for students with diverse needs. Schools have traditionally managed student heterogeneity by sorting students both within and between schools according to their academic ability. However, empirical evidence suggests that such tracking approaches increase inequalities. In more recent years, driven largely by technological advances, there have been calls to embrace students’ individual differences in the classroom and to personalize students’ learning experiences. A central justification for personalized learning is its potential to improve educational equity. In this paper, we discuss whether and under which conditions personalized learning can indeed increase equity in K-12 education by bringing together empirical and theoretical insights from different fields, including the learning sciences, philosophy, psychology, and sociology. We distinguish between different conceptions of equity and argue that personalized learning is unlikely to result in “equality of outcomes” and, by definition, does not provide “equality of inputs”. However, if implemented in a high-quality way, personalized learning is in line with “adequacy” notions of equity, which aim to equip all students with the basic competencies to participate in society as active members and to live meaningful lives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Dreams and realities of school tracking and vocational education

Elementary school teachers’ perspectives about learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

Real-world effectiveness of a social-psychological intervention translated from controlled trials to classrooms

From tracking to personalized learning.

Resulting from the complex interplay between genetic dispositions and unequal environmental conditions, students begin formal schooling with diverse sets of cognitive skills and socio-emotional characteristics 1 , 2 which are associated with how well and how fast students will learn. Schools around the world thus face the challenge of organizing instruction for large numbers of students while at the same time responding to their individual needs. Given that academic skills vary by student socio-economic background, how schools manage student heterogeneity influences the provision of equal opportunities and the capacity to promote educational equity.

Schools have traditionally treated academic differences as obstacles to be surmounted during classroom instruction, and sought to reduce student heterogeneity by grouping students with similar abilities together. The most obvious example of this is the worldwide practice of organizing students by age, driven by the assumption that students with similar ages have similar abilities and thus require similar instruction 3 , 4 . Schools also sort students according to their abilities into different courses, educational programs and schools, with the aim of creating even more homogeneous groups so that teachers can direct instruction towards the average ability level in a classroom 5 , 6 . However, robust empirical evidence now suggests that such tracking practices increase educational inequalities as less-demanding tracks and courses often provide less opportunities to learn, with disadvantaged students more often assigned to these lower-level tracks 6 , 7 .

In recent years, there have been calls to embrace students’ individual differences 8 through personalized learning—an umbrella term for the idea of adapting instruction to students’ individual needs and providing unique learning experiences for each student. Dockterman 3 even calls for “a new dominant pedagogy” in which “one would never expect all teachers to teach the same lesson on the same day in the same way to all students” (p.15). Technological advances together with major investments by governments, venture philanthropies and technology companies have vastly increased the availability and use of technological solutions for personalized learning in schools and thus contributed to this paradigm shift.

The increasing calls for personalized learning often go hand in hand with the premise that personalized learning will lead to more equitable academic outcomes among students of different social backgrounds 8 , 9 . The fact that children from low socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely to succeed in school than their peers from higher socioeconomic backgrounds continues to be a cause of concern for education systems worldwide 10 , 11 . Alarmingly, despite global educational expansions, socioeconomic disparities in academic achievement have remained stable over multiple generations 12 and have even increased in many countries over the past 50 years 13 . Given these inequalities, the aim of this paper is to discuss whether and under which conditions personalized learning can increase equity in K-12 education by bringing together empirical and theoretical insights from different fields, including the learning sciences, philosophy, psychology and sociology.

Educational equity: theoretical and empirical perspectives

As much as there is agreement on educational equity as a valuable goal, there is no agreement regarding its definition. In fact, very different and even contrasting (implicit or explicit) conceptions of equity exist among researchers, educators, and policy-makers and have been the subject of philosophical debates for decades 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 . In the present paper, we distinguish between prominent conceptions of equity and employ them as an analytic lens as we address the implications of personalized learning for educational equity.

One widely held notion of educational equity centers around educational outcomes, asserting that equity entails students of different backgrounds achieving equal outcomes such as academic performance 15 , 16 . This conception of equity, often referred to as “equality of outcomes”, is based on the premise that educational outcomes serve as a gateway to later life goods such as income, social status and health 16 . This perspective is also reflected in the way social inequalities in education are typically operationalized, particularly through SES achievement gaps, which highlight disparities in academic outcomes between students from different backgrounds.

A widespread counter-perspective to the “equality of outcomes” conception of equity argues that ensuring equality of opportunities is a more appropriate goal 15 . Complicating matters, equality of opportunity is in itself a concept with many different meanings 16 . One common understanding of equality of opportunity is the provision with equal inputs, or resources 16 , 17 . Schouten 16 , however, cautions that this “equality of inputs” conception “will do little more than reinforce unequal opportunities that already exist” (p. 2). In line with this concern, Sokolowski and Ansari 8 contend that “different children require different inputs” (p. 6) to ensure educational equity.

Another conception of educational equity, known as “sufficientarianism” or “adequacy” 16 , 17 , 18 takes into account both inputs and outputs. Scholars following this perspective argue that it may be morally acceptable or even necessary to treat individuals unequally by providing more resources to those who are at risk of falling short of achieving adequate outcomes. That is, the inputs provided should ensure that all students reach a minimum level of educational outcomes. Once this minimum level is achieved, any inequality in educational outcomes is seen to be no longer problematic 15 .

To gain a comprehensive understanding of how personalized learning can improve educational equity, we must also examine the role of schools in exacerbating or mitigating inequalities—a topic that has been the subject of scholarly debate for decades. A large group of scholars views schools as “sorting machines” that contribute to the (re-)production of social inequalities 19 . In contrast, considering the substantial inequalities in academic skills already present at kindergarten entry, others argue that schools serve as “great equalizers” because learning experiences in school are more equal than learning experiences out of school 20 , 21 . Importantly, there is robust empirical support for both arguments. While the two perspectives may seem contradictory, it is important to note that the two viewpoints employ different counterfactuals 22 . Scholars arguing that schools reproduce or even exacerbate inequality ask, “What would inequality look like if students attended identical schools?’’, scholars focusing on the potentially equalizing effects of schooling ask, “What would inequality look like if students did not attend school?’’ Therefore, when analyzing how personalized learning can improve educational equity, it is important to consider what the learning experience of students would be like without personalized learning, which may vary greatly depending on the respective socioeconomic context.

Personalized learning: the revival of a multifaceted concept

The idea of personalizing learning by adapting instruction to students’ individual differences has existed for centuries 3 , 23 . Notably, Dewey’s 24 progressive educational philosophy can be regarded a key historical root of personalized learning as he argued that education should be centered around students’ interests, experiences, and abilities. In the 1970’s, the notion of personalizing learning gained further prominence thanks to Vygotsky’s 25 theoretical concept of students’ “zone of proximal development” and Cronbach and Snow’s 26 empirical research on so-called “aptitude-treatment interactions”, which aimed to identify the most effective instructional strategies based on students' individual characteristics. Despite this long history in academic circles, personalization has not been widely implemented in practice, most likely because adapting instruction to individual students is highly challenging for teachers 27 . In recent years, however, technological advances have presented new opportunities to take students’ needs into account during classroom instruction, propelling the increased popularity of personalized learning 28 .

While personalized learning generally refers to the idea of responding to individual student needs during classroom instruction, it appears in many different forms 29 . In fact, the term personalized learning has been used to describe a wide range of different instructional approaches 30 , 31 . This lack of a shared definition is further complicated by the fact that other terms—such as adaptive teaching 32 , 33 , individualized instruction 34 , 35 , or differentiated instruction 36 , 37 —are often used interchangeably with the term personalized learning. One key difference between these other terms and personalized learning is that the latter is mostly used when classroom instruction involves learning technologies such as adaptive learning systems, intelligent tutoring systems or even educational robots 30 , 38 . Such learning technologies continuously collect data about students and adjust tasks, instructional materials or feedback accordingly via algorithms or artificial intelligence. To date, there are numerous technological solutions for personalized learning available, which differ greatly with respect to the data collected, the learner characteristics taken into account (e.g. prior knowledge, typical errors, motivation, self-regulation skills), the use of artificial intelligence and the role of teachers 39 , 40 However, despite the great advantages of learning technologies for personalized learning, scholars have noted that personalized learning does not necessarily require the use of technologies 41 .

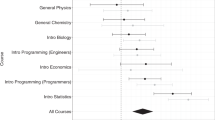

Personalized learning does find support in the recent literature, with some studies reporting that such approaches, especially those supported by adaptive learning technologies, are more effective in raising student achievement than traditional non-adaptive instruction 34 , 37 , 39 , 42 , 43 . Whereas the majority of this research occurred in high-income countries, technology-supported personalized learning has also been shown to be effective in low- and middle-income countries 29 , 44 . In contrast, the emerging evidence for the benefits of personalized learning to reduce educational inequalities is much more mixed: Some scholars have reported that technology-enabled personalized learning approaches particularly benefited low-performing students 45 . Others found that initially low-performing students 46 and students with lower working memory capacity 47 learned less than their more competent peers when using technology-enabled personalized learning systems. Experimentally addressing the question whether computer-assisted instruction can narrow the SES achievement gap, Chevalère et al. 48 found that students from low- and high-SES backgrounds benefited equally from such instruction in comparison to conventional teacher-led instruction. Importantly, even though the SES achievement gap remained the same, low-SES students receiving computer-assisted instruction performed comparably well to high-SES students receiving conventional instruction. Given these mixed findings, we will now take a closer look at the conditions that must be in place for personalized learning to provide greater educational equity. More specifically, we will consider the conditions related to the human cognitive architecture, the self-regulatory and socio-emotional needs of students and the broader context of schooling.

Considering the human cognitive architecture

Considering the human cognitive architecture is key to our understanding of whether personalized learning can improve educational equity. Over the past several decades, the learning sciences have compiled a large knowledge base on how people learn, in particular how complex knowledge is acquired beyond the mere memorization of facts. This research has shown that learning is a highly individual and active process, which happens through the interaction of individuals with their social environment 49 , 50 , 51 . Learners are not passive recipients of information; rather, they make sense of content by building a coherent and organized mental representation of that content and by integrating it with their prior knowledge 52 .

There are large individual differences between students in their learning potential 8 . Differences in learning potential mainly reflect differences in general cognitive abilities and in domain-specific prior knowledge, which individuals acquire via previous formal and informal learning opportunities 52 . Because prior knowledge in one domain is the foundation for acquiring new and more complex knowledge in the same domain, it is not surprising that students’ prior knowledge is the most important determinant of academic performance 53 . Importantly, differences in students’ learning potential are not stable, but dynamic and change over time 54 .

Psychological research suggests that instruction is most effective when these cognitive characteristics of students are continuously taken into account. That is, when content is too advanced given a students’ prior knowledge, there is a risk of cognitive overload whereby new knowledge is not learned or only learned on a very superficial level 55 . If the learning content is too easy and the learner is not cognitively challenged, learning can likewise be hampered. Hence, the targeted instruction associated with personalized learning should cognitively stimulate every student equally and result in learning gains of all students.

But what about educational equity? The answer greatly depends on the considered conception of equity. If equity is understood solely in terms of "equality of outcomes," personalized learning may have limited benefits. In fact, personalized learning, which helps all individuals reach their full potential, may accentuate and even exacerbate student differences in academic performance, as high-ability students are permitted to advance more quickly through curricular content and their initial advantage over their low-ability peers grows even wider 8 , 52 . And since academic achievement is often tied to socioeconomic status, personalized learning may then widen existing socioeconomic disparities in student outcomes.

The “equality of inputs” notion of equity also stands in contrast to personalized learning, as the explicit rationale for personalized learning is to treat students differently based on their respective needs. Hence, scholars who view equity as the provision of equal opportunities through differential treatments 8 , are likely to view personalized learning as a means of improving equity. Furthermore, the "adequacy" notion of equity, which aims to ensure that all students reach a minimum level of educational outcomes, also aligns with personalized learning, and we will explore this perspective further in the concluding section.

Considering students’ self-regulatory and socio-emotional needs

Learning is more than a cognitive activity; rather, it encompasses multiple emotional, motivational and social processes 50 , 56 , 57 . During classroom instruction, it is therefore vital to continuously take students’ diverse needs into account in an integrative manner. In particular, students’ self-regulatory and social-emotional needs are constantly subject to change and deserve attention during instruction.

Students’ self-regulatory skills are key to understanding whether and how personalized learning can foster educational equity. There is robust empirical evidence showing that students with lower cognitive abilities and lower levels of prior knowledge are less capable of self-regulating their own learning process and require increased instructional support and guidance, a phenomenon known as the “expertise-reversal effect” 58 . Although technology-enabled personalized learning approaches adjust the difficulty level of instructional tasks, they typically do not take into account students’ self-regulatory skills such as the use of meta-cognitive strategies 59 . This means that they do not systematically develop such skills in students, yet they place enormous self-regulatory burdens on students, which can result in off-task behaviors and a lack of engagement for some students. This is supported by a recent study. In the implementation of one personalized learning system that required considerable student autonomy and assumed a high degree of student self-regulation, low-performing students learned less than their high-performing peers, despite the fact that each student had in fact received academic content “just right” for their skill level 46 . However, it is important to note that the problem of overburdening students does not solely apply to technological solutions for personalized learning. If teachers equate personalized learning with a “student-centered” approach in which students can choose their own learning content and are responsible for their learning process without much interaction with their teachers, the same issue arises. Research has consistently shown that all students need explicit instruction in self-regulation strategies 60 , pointing to the important role of teachers in helping students acquire self-regulatory skills or in explicitly designing educational technologies which gradually develop self-regulatory skills 61 .

Additional student characteristics that most personalized learning systems to date do not take into account include students’ motivation, goals, beliefs, interests, emotional states and personality 28 , 30 . Strong evidence suggests that such socio-emotional needs must be fulfilled via high-quality social interactions. Not only is learning a deeply social activity, learners require emotional safety and a sense of belonging in order to cognitively engage in learning 57 . Therefore, academic success requires that teachers build strong, supportive relationships with their students, which is particularly important for students from less-advantaged backgrounds 62 . This stands in contrast to some technology-based personalized learning approaches in which teachers are reduced to “facilitators.” In fact, Lee et al. 4 found that many teachers in schools transitioning to a personalized learning approach heavily built on technologies were not able to build close relationships with their students. Similarly, Nitkin et al. 46 reported that low-achieving students working with a personalized learning system learned the most in instructional modalities where they worked closely with teachers, and learned the least in modalities where they worked alone.

In summary, these findings underscore the crucial role of teachers in personalized learning, especially for students who are struggling academically or come from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. Without strong instructional and emotional support from teachers, personalized learning is likely to harm educational equity, regardless of the conception of equity that is applied. If students’ self-regulatory and socio-emotional needs are not taken into account, differences in educational outcomes will widen—as indicated by a recent study, which showed that students with higher working memory capacity benefited more from technology-enabled personalized learning than their peers with lower working memory 47 . Not only would the “equality of outcome” notion of equity be violated, but the “equality of inputs” perspective and the perspective of providing equal opportunities based on students' needs would also be compromised. As a result, this would also violate the “adequate” principle of equity and put low-achieving students and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds at risk of not reaching the minimum proficiency level.

Considering the broader context

The extent to which personalized learning can contribute to educational equity also depends on the broader context in which teaching and learning takes place. Students’ experiences with personalized learning can vary widely across (and even within) schools 46 . In many countries, between-school social and academic stratification is primarily the result of residential segregation, because most children attend schools close to their homes. In other countries, tracking is the main force driving the large differences between schools, including disparities in their socioeconomic composition. Hence, students from low- and high socioeconomic backgrounds often attend schools that differ greatly in the quality of education they provide. More specifically, schools serving high concentrations of economically disadvantaged students not only cater to larger numbers of children with academic and behavioral problems, they also have fewer resources and attract less qualified teachers than schools serving students from high socioeconomic backgrounds 63 , 64 . This confluence of factors makes it more difficult to provide high-quality personalized learning. This especially applies to technology-enabled personalized learning approaches, as disadvantaged schools may not have the necessary technological equipment, software, reliable and robust internet access or technical support staff, let alone teachers who know how to effectively integrate technology into teaching 65 , 66 .

The implementation of personalized learning in low-income countries is even more challenging than in disadvantaged schools in high-income countries. Many of the assumptions under which technology-enabled personalization operates do not transfer to low-income countries, such as a 1:1 child-computer ratio 67 . Although there has been a rapid expansion of school enrollments in the past decades in low-income countries, including those in sub-Saharan Africa, the majority of students still do not possess basic competencies in reading and mathematics 68 . Many schools in low-income countries, especially in rural areas, are confronted with a lack of physical infrastructure (e.g. electricity, enough classrooms, access to reliable internet) and educational resources (e.g. textbooks, computers), and are often challenged by underqualified and inexperienced teachers, high rates of teacher absenteeism, student-teacher-ratios as high as 100:1 and high levels of student poverty and malnutrition 67 , 68 , 69 . However, this does not necessarily apply to all schools as there is evidence that schools in low-income countries are also characterized by stark segregation and large differences in school quality 68 . Even though the implementation of personalized leaning under such harsh circumstances is extremely challenging 69 , there is robust evidence that among myriad interventions, pedagogical interventions in which teacher instruction is adapted to student needs are the most effective in increasing student performance 44 .

Taken together, the potential of personalized learning for improving educational equity may be hampered by the unequal conditions of the broader context in which teaching and learning takes places. No pedagogical strategy will be able to compensate for stark socioeconomic inequalities between schools and districts. At the same time, the role of personalized learning, in particular technology-enabled personalized learning, for improving educational equity may depend on the context itself. In industrialized countries, the overuse of technology may crowd out the benefits of human contact between teachers and students, which could be particularly detrimental for low-achieving students. In low income-countries with no universal access to schooling and high numbers of unqualified teachers, technology-enabled personalized learning may have a greater potential to improve equity than in industrialized countries because the technology may be all that is available for some students.

Implications for the implementation of personalized learning

The potential of personalized learning to improve learning outcomes and educational equity can only be achieved as long as teachers continue to play a crucial role. Teachers can adapt to students’ needs in multiple ways, for instance by questioning, assessing, encouraging, modeling, managing, explaining, giving feedback, challenging, or making connections 70 . Instead of replacing teachers, learning technologies should empower teachers and facilitate learning and teaching processes 40 , 71 . New developments towards “hybrid intelligent learning technologies”, which have been developed in collaboration with teachers, offer great potential to rethink which teaching tasks can and should be offloaded to artificial intelligence—and which should remain the responsibility of teachers 40 . The further development of personalized learning technologies should also address whether and how students’ self-regulatory and socio-emotional needs can be taken into account. This implies addressing the role that students can play in co-constructing their learning experiences. Importantly, teachers should stay engaged with classroom learning activities at all times and monitor students’ learning whenever necessary. As long as personalized learning systems only adapt to students’ cognitive skills, teachers must respond to students’ self-regulatory skills and socio-emotional needs, which is particularly important for low-achieving and disadvantaged students 50 . Taken together, the effective incorporation of personalized learning technologies poses significant challenges for teachers, and this is likely to persist as these technologies continue to rapidly evolve through improved artificial intelligence.

Implementing personalized learning also requires a context-sensitive approach that takes into account the conditions under which learning occurs, particularly in low-income countries. In addition to obvious adjustments due to a lack of resources, an understanding of the local social environment is also needed. For instance, if high levels of teacher absenteeism are a problem, it is important that teachers do not feel obsolete when learning technologies are implemented, thus leading to even higher levels of disengagement. Hence, even though personalized learning holds great promise for improving school learning in low-income countries, the nature and form of personalized learning may be different than in high-income countries 67 . That is, personalized learning itself needs to be personalized.

Finally, whole-school approaches to implementing personalized learning may be particularly promising, because they also consider school organizational and institutional factors, which could otherwise hamper the potential of personalized learning. Two well-evaluated whole-school reform programs in the U.S. that were specifically designed for disadvantaged students—Success for All and the University of Chicago Charter School—have been shown to improve learning for disadvantaged students 72 , 73 . Interestingly, even though these programs do not call their instructional approach personalized learning, one key element is that teachers adapt their instruction to students’ needs.

Aiming for adequacy instead of equality of inputs or outcomes

Given the theoretical considerations and presented empirical evidence in this paper, which reflect insights from multiple academic disciplines, what can we conclude about the potential of personalized learning to improve educational equity? Learning is a highly individual process shaped by each student’s unique characteristics. Adapting instruction to students’ specific needs and personalizing students’ learning experience should—at least in theory and when implemented as outlined in the previous section—lead to learning gains for all students and support each individual student in reaching their full potential. However, as explained above, this is likely not to lead to “equality of outcomes” and may even increase inequalities, because high-ability students may learn at a faster rate than low-ability students. The solution is certainly not to deprive high-ability students of appropriate learning opportunities.

Moreover, by definition, personalized learning cannot increase equity defined in terms of “equality of inputs”, as the concept of personalized learning is based on the premise that unequal inputs are needed to provide students with equal opportunities to learn. The complicated issue, then, is deciding how much inequality of inputs is reasonable and fair, particularly given limited resources. We argue that the solution may be found in the “adequacy” conception of educational equity 16 , 17 , 18 . That is, inequality in outcomes are tolerable if all students develop the basic competencies necessary to fully participate in society as active members and to live meaningful and fulfilling lives. This also implies that inequality of inputs is appropriate to the extent that at-risk students are provided the resources necessary to develop these competencies. In fact, in the U.S., the notion of educational adequacy is increasingly framed as a constitutional right, where all citizens deserve schooling that at a minimum provides the knowledge and skills needed for success in the modern world, and the ability to assume adult roles as active and engaged citizens 74 .

Based on the adequacy understanding, personalized learning surely serves the interests of educational equity. At the same time, this opens up a number of new questions and issues, in particular how basic competencies are conceptualized and defined. While there may be a wide agreement that all students should be literate and numerate, given their importance in shaping outcomes across the life span 75 , there may not be shared definitions of “basic”, let alone consensus on the host of more complex skills that the economy will demand in the future. Hence, the implementation of personalized learning must be accompanied by deep normative discussions on the ultimate aims of education, and its role in the production of a more equitable and just society.

Bradley, R. H. & Corwyn, R. F. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53 , 371–399 (2002).

PubMed Google Scholar

Brooks-Gunn, J. & Duncan, G. J. The effects of poverty on children. Future Child. 7 , 55–71 (1997).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dockterman, D. Insights from 200+ years of personalized learning. Npj Sci. Learn. 3 , 15 (2018).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lee, D., Huh, Y., Lin, C. ‑Y. & Reigeluth, C. M. Personalized learning practice in U.S. learner-centered schools. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 14 , ep385 (2022).

Google Scholar

Domina, T. et al. Beyond tracking and detracking: the dimensions of organizational differentiation in schools. Sociol. Educ. 92 , 293–322 (2019).

Terrin, É. & Triventi, M. The effect of school tracking on student achievement and inequality: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 93 , 236–274 (2023).

Van de Werfhorst, H. G. & Mijs, J. J. B. Achievement inequality and the institutional structure of educational systems: a comparative perspective. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 36 , 407–428 (2010).

Sokolowski, H. M. & Ansari, D. Understanding the effects of education through the lens of biology. Npj Sci. Learn. 3 , 17 (2018).

Roberts-Mahoney, H., Means, A. J. & Garrison, M. J. Netflixing human capital development: personalized learning technology and the corporatization of K-12 education. J. Educ. Policy 31 , 405–420 (2016).

Kim, S. W., Cho, H. & Kim, L. Y. Socioeconomic status and academic outcomes in developing countries: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 89 , 875–916 (2019).

Liu, J., Peng, P., Zhao, B. & Luo, L. Socioeconomic status and academic achievement in primary and secondary education: a meta-analytic review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 34 , 2867–2896 (2022).

von Stumm, S., Cave, S. N. & Wakeling, P. Persistent association between family socioeconomic status and primary school performance in Britain over 95 years. Npj Sci. Learn. 7 , 4 (2022).

Chmielewski, A. K. The global increase in the socioeconomic achievement gap, 1964 to 2015. Am. Sociol. Rev. 84 , 517–544 (2019).

Jencks, C. Whom must we treat equally for educational opportunity to be equal. Ethics 98 , 518–533 (1988).

Levinson, M., Geron, T. & Brighouse, H. Conceptions of educational equity. AERA Open 8 , 1–12 (2022).

Schouten, G. In Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory (ed. Peters, M. A.) pp. 1–7 (Springer Singapore, 2018).

Temkin, L. S. The many faces of equal opportunity. Theory Res. Educ. 14 , 255–276 (2016).

Satz, D. Equality, adequacy, and education for citizenship. Ethics 117 , 623–648 (2007).

Domina, T., Penner, A. & Penner, E. Categorical inequality: schools as sorting machines. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 43 , 311–330 (2017).

Downey, D. B. & Condron, D. J. Fifty years since the Coleman Report: rethinking the relationship between schools and inequality. Sociol. Educ. 89 , 207–220 (2016).

Raudenbush, S. W. & Eschmann, R. D. Does schooling increase or reduce social inequality? Annu. Rev. Sociol. 41 , 443–470 (2015).

Dumont, H. & Ready, D. Do schools reduce or exacerbate inequality? How the associations between student achievement and achievement growth influence our understanding of the role of schooling. Am. Educ. Res. J. 57 , 728–774 (2020).

Washburne, C. W. In The Twenty-fourth Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education (ed G. M. Whipple) pp. 257–272 (University of Chicago Press, 1925).

Dewey, J. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education (Collier-Macmillan, 1916).

Vygotsky, L. S. Mind in Society: the Development of Higher Psychological Processes (Harvard University Press, 1978).

Cronbach, L. J. & Snow, R. E. Aptitudes and Instructional Methods: A Handbook for Research on Interactions (Irvington, New York, 1977).

Suprayogi, M. N., Valcke, M. & Godwin, R. Teachers and their implementation of differentiated instruciton in the classroom. Teach. Teach. Educ. 67 , 291–301 (2017).

Plass, J. L. & Pawar, S. Toward a taxonomy of adaptivity for learning. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 52 , 275–300 (2020).

Major, L., Francis, G. A. & Tsapali, M. The effectiveness of technology-supported personalised learning in low-and middle-income countries: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 52 , 1935–1964 (2021).

Bernacki, M. L., Greene, M. J. & Lobczowski, N. G. A systematic review of research on personalized learning: personalized by whom, to what, how, and for what purpose(s)? Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33 , 1675–1715 (2021).

Treviranus, J. In Springer International Handbooks of Education. Second Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education (eds Voogt, J. et al.) pp. 1025–1046 (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

Corno, L. On teaching adaptively. Educ. Psychol. 43 , 161–173 (2008).

Vaughn, M., Pearson, S. A. & Gallagher, M. A. Challenging scripted curricula with adaptive teaching. Educ. Res. 51 , 186–196 (2022).

Connor, C. M. et al. A longitudinal cluster-randomized controlled study on the accumulating effects of individualized literacy instruction on students' reading from first trough third grade. Psychol. Sci. 24 , 1408–1419 (2013).

Tetzlaff, L., Hartmann, U., Dumont, H. & Brod, G. Assessing individualized instruction in the classroom: comparing teacher, student, and observer perspectives. Learn. Instr. 82 , 101655 (2022).

Bondie, R. S., Dahnke, C. & Zusho, A. How does changing “one-size-fits-all” to differentiated instruction affect teaching? Rev. Res. Educ. 43 , 336–362 (2019).

Deunk, M. I., Smale-Jacobse, A., Boer, H., de, Doolaard, S. & Bosker, R. J. Effective differentiation practices: a sytsematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the cognitive effects of differentiation practices in primary education. Educ. Res. Rev. 24 , 31–54 (2018).

Baker, R. S. In OECD digital education outlook 2021: Pushing the frontiers with AI, blockchain, and robots (ed Vincent-Lancrin, S.) pp. 43–54 (OECD, 2021).

Aleven, V., McLaughlin, E. A., Glenn, R. A. & Koedinger, K. R. In Handbook of Research on Learning and Instruction (ed. Mayer, R. E. & Alexander, P.) pp. 522-560 (Routledge, New York, 2017).

Molenaar, I. Towards hybrid human-AI learning technologies. Eur. J. Educ. 57 , 632–645 (2022).

Walkington, C. & Bernacki, M. L. Appraising research on personalized learning: definitions, theoretical alignment, advancements, and future directions. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 52 , 235–252 (2020).

Ma, W., Adesope, O. O., Nesbit, J. C. & Liu, Q. Intelligent tutoring systems and learning outcomes: a meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 106 , 901–918 (2014).

Zhang, L., Basham, J. D. & Yang, S. Understanding the implementation of personalized learning: a research synthesis. Educ. Res. Rev. 31 , 100339 (2020).

Evans, D. K. & Popova, A. What really works to improve learning in developing countries? An analysis of divergent findings in systematic reviews. World Bank Res. Observer 31 , 242–270 (2016).

Hassler Hallstedt, M., Klingberg, T. & Ghaderi, A. Short and long-term effects of a mathematics tablet intervention for low performing second graders. J. Educ. Psychol. 110 , 1127–1148 (2018).

Nitkin, D., Ready, D. D. & Bowers, A. J. Using technology to personalize middle school math instruction: evidence from a blended learning program in five public schools. Front. Educ. 7 , 646471 (2022).

Chevalère, J. et al. Computer-assisted instruction versus inquiry-based learning: the importance of working memory capacity. PLoS ONE 16 , e0259664 (2021).

Chevalère, J. et al. Compensating the socioeconomic achievement gap with computer‐assisted instruction. J. Computer Assist. Learn. 38 , 366–378 (2022).

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L. & Cocking, R. R. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School . (National Academy Press, 2000).

Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. & Osher, D. Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 24 , 97–140 (2020).

Dumont, H., Istance, D. & Benavides, F. (Eds.), The Nature of Learning: Using Research to Inspire Practice . (OECD, Paris, 2010).

Stern, E. Individual differences in the learning potential of human beings. Npj Sci. Learn. 2 , 2 (2017).

Simonsmeier, B. A., Flaig, M., Deiglmayr, A., Schalk, L. & Schneider, M. Domain-specific prior knowledge and learning: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. 57 , 31–54 (2022).

Tetzlaff, L., Schmiedek, F. & Brod, G. Developing personalized education: a dynamic framework. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33 , 863–882 (2021).

Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J. J. G. & Paas, F. G. Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 10 , 251–296 (1998).

Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L. & Rose, T. Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: how children learn and develop in context1. Appl. Dev. Sci. 23 , 307–337 (2019).

Nasir, N. S., Lee, C. D., Pea, R. & McKinney de Royston, M. Rethinking learning: what the interdisciplinary science tells us. Educ. Res. 50 , 557–565 (2021).

Kalyuga, S. Expertise reversal effect and its implications for learner-tailored instruction. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 19 , 509–539 (2007).

Molenaar, I. The concept of hybrid human-AI regulation: exemplifying how to support young learners' self-regulated learning. Comput. Educ.: Artif. Intell. 3 , 100070 (2022).

Dignath, C. & Veenman, M. V. J. The role of direct strategy instruction and indirect activation of self-regulated learning - Evidence from classroom observation studies. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33 , 489–533 (2021).

Brod, G., Kucirkova, N., Shepherd, J., Jolles, D. & Molenaar, I. Agency in educational technology: Interdisciplinary perspectives and implications for learning design. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 35 , 25 (2023).

Hamre, B. & Pianta, R. Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Dev. 76 , 949–967 (2005).

Goldhaber, D., Quince, V. & Theobald, R. Has it always been this way? tracing the evolution of teacher quality gaps in U.S. public schools. Am. Educ. Res. J. 55 , 171–201 (2018).

Reardon, S. F. & Owens, A. 60 Years after brown: trends and consequences of school segregation. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 40 , 199–218 (2014).

Rafalow, M. H. & Puckett, C. Sorting machines: digital technology and categorical inequality in education. Educ. Res. 51 , 274–278 (2022).

Warschauer, M., & Xu, F. In Springer International Handbooks of Education. Second Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education (ed Voogt, J. et al.) pp. 1064–1079 (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

Zualkernan, I. A. In Lecture Notes in Educational Technology. The Future of Ubiquitous Learning (eds Gros, B., Kinshuk & Maina, M.) pp. 241–258 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016).

Gruijters, R. J. & Behrman, J. A. Learning inequality in Francophone Africa: school quality and the educational achievement of rich and poor children. Sociol. Educ. 93 , 256–276 (2020).

Alhassan, A. ‑R. K. & Abosi, O. C. Teacher effectiveness in adapting instruction to the needs of pupils with learning difficulties in regular primary schools in Ghana. SAGE Open 4 , 215824401351892 (2014).

Parsons, S. A. et al. Teachers´ instructional adaptations: a research synthesis. Rev. Educ. Res. 88 , 205–242 (2018).

Dillenbourg, P. Design for classroom orchestration. Comput. Educ. 69 , 485–492 (2013).

Borman, G. D. et al. Final reading outcomes of the national randomized field trial of success for all. Am. Educ. Res. J. 44 , 701–731 (2007).

McGhee Hassrick, E., Raudenbush, S. W. & Rosen, L. The Ambitious Elementary School . Its Conception, Design, and Implications for Educational Equality (The University of Chicago Press, 2017).

Rebell, M. A. Flunking Democracy: Schools, Courts, and Civic Participation (University of Chicago Press, 2018).

Watts, T. W. Academic achievement and economic attainment: reexamining associations between test scores and long-run earnings. AERA Open . 6 (2020).

Download references

Funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project Number 491466077. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Sciences, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

Hanna Dumont

Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, USA

Douglas D. Ready

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

H.D. conceptualized the paper, wrote the original draft, and edited the paper. D.D.R. contributed to conceptualizing and editing the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hanna Dumont .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dumont, H., Ready, D.D. On the promise of personalized learning for educational equity. npj Sci. Learn. 8 , 26 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-023-00174-x

Download citation

Received : 15 December 2022

Accepted : 13 July 2023

Published : 04 August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-023-00174-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

COVID-19, the educational equity crisis, and the opportunity ahead

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, heather j. hough heather j. hough executive director - pace @hjhough.

April 29, 2021

As the one-year anniversary of campus closures due to COVID-19 passed last March, nearly half of America’s children were attending schools operating remotely or open only on a hybrid basis. In California, more than 70% of students were attending schools that were fully remote.

But spring brings new hope. Amid steps to ensure safe health practices and the acceleration of vaccinations, the rates of transmission have decreased from earlier peaks in the winter and students are beginning to return to school.

While the return of students to campus is something to celebrate, it is essential to note that the pandemic and related prolonged school disruptions have and will continue to have a profound impact on the lives and learning of students.

Due to inequitable access to health care, income inequality, and disproportionate employment in high-risk, “essential” jobs, low-income, Black, Latino, and Native American communities have borne the brunt of the pandemic, with dire health and economic impacts that hinder their children’s educational opportunities and learning. It is difficult for children to learn if they are sick or hungry, or if they have family members who are sick or even dying. Some students have found themselves without a safe, stable place to live, lacking basic necessities, and disconnected from needed services and supports when schools—a primary avenue for public service delivery—closed for months on end.

Making learning in the pandemic even more challenging, many of these students have lacked reliable access to the internet and computers. And working parents have often found themselves unable to stay at home with their children, sometimes leaving them without needed supervision and support. This has been especially difficult for children in the early grades who may not be able to independently follow directions or navigate online assignments, as well as for some students in upper grades, who may need support to stay on task and away from online distractions such as social media. These instructional support issues are only compounded for students learning English or those with special needs.

Research by my organization, Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE), has documented how student learning has suffered during the pandemic, leading to growing equity gaps. One study showed significant learning lag in both English language arts and math, with students in grades 4-6 the most impacted. As of fall 2020, students in these grades were between 5 and 25% behind where they would be in a typical year. These averages mask serious differences between student groups. In most grades, low-income students are substantially further behind than higher-income students. And in some grades, lower-income students are falling behind while higher-income students’ learning actually accelerated. Further, students learning English demonstrate substantially more learning lag than comparison students in nearly every grade in English language arts and in early grades for math. For example, on the MAP English language arts assessment, grade 5 students learning English are roughly 30% behind, while native English-speaking students are only 10% behind.

Another study , with colleagues at Stanford, examining oral reading fluency in grades 1-3 found that in the spring of 2020, the development of reading fluency largely stopped. Students’ reading fluency was again growing at normal rates by the fall, but the return to nearly average gains was not sufficient to recoup spring’s losses. No growth in the spring and summer meant that in fall 2020, students in 2 nd and 3 rd grade had fallen about a third of a year behind where they should be in terms of expected reading development. These findings also show that students in historically low-performing districts are falling behind at a faster rate.

In our studies and others like them, many students are missing from schools and assessments. We suspect some of the students that have missing data in our analyses may be disengaged or missing from school altogether. K-12 public school enrollment in California has dropped by a record 160,000 students (a 3% decline overall), a change about five times greater than the state’s annual rate of enrollment decline in recent years. It is likely that students missing from our analyses have experienced even larger learning losses than those students observed, meaning that the equity impact of the pandemic is almost certainly larger than we estimate.

As we move forward, we need to be particularly concerned for our youngest and oldest students. The biggest declines in enrollment are in the earliest grades , and preschool enrollment is down as well. Additionally, distance learning has been hardest for our youngest students , meaning that a large proportion of students are likely to start kindergarten and 1st grade very far behind. If these students in the early grades don’t develop the basic skills they need, it may be difficult for them to access future learning.

Additionally, older students have experienced more challenges around mental health, isolation, and disengagement , and with greater consequences. Across the state of California, there are troubling signs that high school students are not engaging with distance learning. In Sacramento City Unified School District, 10 times more students are significantly disengaged compared to last year. And in Los Angeles Unified , the number of Ds and Fs in grades 9-12 increased by 8.7 percentage points in the fall compared to the same time period last year, with greater increases among Black (23.2%) and Latino (24.9%) students. If educators don’t work hard to get these students back on track, graduation rates will decline and inequities in college access and success will increase.

Our educational system in the United States was already highly inequitable and plagued by opportunity gaps in learning that have widened during the pandemic. Although we may see the light at the end of the tunnel on the coronavirus crisis, the educational equity crisis is just beginning.

This unprecedented challenge requires unprecedented action. The good news is that new federal investments offer needed resources. California K-12 schools have received or are slated to receive roughly $28.6 billion in federal funds between spring 2020 and spring 2021 to address pandemic response and learning loss. About $129 billion in COVID-19 relief funds will go to K-12 schools nationally .

This money must be used to catalyze a transformation in our education systems. While many are eager for a return to normal, the old “normal” was under-serving our nation’s most vulnerable children and youth. As we respond to this public health and education emergency, we must build toward an education system that places equity at the center so that all students—and especially those most impacted by the pandemic and systemic racism—have the support and opportunities they need to achieve their potential.

We can begin by nurturing student social and emotional well-being to support academic progress. But we must also go further to reimagine the very systems in which students learn. By redesigning schools to be restorative places —places where students feel safe, known, supported, and fully engaged in learning—we can lay the groundwork for long-term and systemic transformation. Such a system should prioritize relationships between families, students, and educators, address whole-child needs, strengthen staffing and partnerships between schools and community partners, and empower teams to rebuild and reimagine systems. This transformation must happen in every school and district in the country, and especially in those serving low-income students and students of color who have for too long been ignored.

The new one-time federal funding for these efforts is critical, but local, state, and federal leaders should be planning now to improve and expand overall school funding in a way that provides sufficient funding for education systems and ensures the equitable distribution of funding to those schools and districts serving students with the highest levels of need. The old adage goes, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare the inequities in our society and in our schools, but the disruption in the status quo presents an opportunity to reimagine and rebuild our educational systems to better serve America’s students.

Related Content

Anna Saavedra, Morgan Polikoff, Dan Silver, Amie Rapaport

March 23, 2021

Daphna Bassok, Lauren Bauer, Stephanie Riegg Cellini, Helen Shwe Hadani, Michael Hansen, Douglas N. Harris, Brad Olsen, Richard V. Reeves, Jon Valant, Kenneth K. Wong

March 12, 2021

Education Access & Equity K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Katharine Meyer

May 7, 2024

Jamie Klinenberg, Jon Valant, Nicolas Zerbino

Thinley Choden

May 3, 2024

- Our Mission

Using Data to Advance Equity

Listening to students is a valuable source of data as schools seek to support students and create more equitable learning outcomes.

Equity now is anchored on an idea that students’ voices matter. If we listen to our students, they will tell us precisely what they need, but they might tell us things that we may not want to hear. Listening to students can be a valuable data point. There will be no need to guess or hypothesize about how we can best support them; we can go directly to the source. But we must be prepared to hear the honest, insightful, surprising, critical, and at times angry perceptions that young people can offer. I recently worked with a school district that has been focused on improving the experiences and outcomes of Black students. I was brought in to help the district “do better” by its Black students. The district asked me if I could help to create a plan of action or set of professional learnings to help improve Black student outcomes across the district.