Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 113 great research paper topics.

General Education

One of the hardest parts of writing a research paper can be just finding a good topic to write about. Fortunately we've done the hard work for you and have compiled a list of 113 interesting research paper topics. They've been organized into ten categories and cover a wide range of subjects so you can easily find the best topic for you.

In addition to the list of good research topics, we've included advice on what makes a good research paper topic and how you can use your topic to start writing a great paper.

What Makes a Good Research Paper Topic?

Not all research paper topics are created equal, and you want to make sure you choose a great topic before you start writing. Below are the three most important factors to consider to make sure you choose the best research paper topics.

#1: It's Something You're Interested In

A paper is always easier to write if you're interested in the topic, and you'll be more motivated to do in-depth research and write a paper that really covers the entire subject. Even if a certain research paper topic is getting a lot of buzz right now or other people seem interested in writing about it, don't feel tempted to make it your topic unless you genuinely have some sort of interest in it as well.

#2: There's Enough Information to Write a Paper

Even if you come up with the absolute best research paper topic and you're so excited to write about it, you won't be able to produce a good paper if there isn't enough research about the topic. This can happen for very specific or specialized topics, as well as topics that are too new to have enough research done on them at the moment. Easy research paper topics will always be topics with enough information to write a full-length paper.

Trying to write a research paper on a topic that doesn't have much research on it is incredibly hard, so before you decide on a topic, do a bit of preliminary searching and make sure you'll have all the information you need to write your paper.

#3: It Fits Your Teacher's Guidelines

Don't get so carried away looking at lists of research paper topics that you forget any requirements or restrictions your teacher may have put on research topic ideas. If you're writing a research paper on a health-related topic, deciding to write about the impact of rap on the music scene probably won't be allowed, but there may be some sort of leeway. For example, if you're really interested in current events but your teacher wants you to write a research paper on a history topic, you may be able to choose a topic that fits both categories, like exploring the relationship between the US and North Korea. No matter what, always get your research paper topic approved by your teacher first before you begin writing.

113 Good Research Paper Topics

Below are 113 good research topics to help you get you started on your paper. We've organized them into ten categories to make it easier to find the type of research paper topics you're looking for.

Arts/Culture

- Discuss the main differences in art from the Italian Renaissance and the Northern Renaissance .

- Analyze the impact a famous artist had on the world.

- How is sexism portrayed in different types of media (music, film, video games, etc.)? Has the amount/type of sexism changed over the years?

- How has the music of slaves brought over from Africa shaped modern American music?

- How has rap music evolved in the past decade?

- How has the portrayal of minorities in the media changed?

Current Events

- What have been the impacts of China's one child policy?

- How have the goals of feminists changed over the decades?

- How has the Trump presidency changed international relations?

- Analyze the history of the relationship between the United States and North Korea.

- What factors contributed to the current decline in the rate of unemployment?

- What have been the impacts of states which have increased their minimum wage?

- How do US immigration laws compare to immigration laws of other countries?

- How have the US's immigration laws changed in the past few years/decades?

- How has the Black Lives Matter movement affected discussions and view about racism in the US?

- What impact has the Affordable Care Act had on healthcare in the US?

- What factors contributed to the UK deciding to leave the EU (Brexit)?

- What factors contributed to China becoming an economic power?

- Discuss the history of Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies (some of which tokenize the S&P 500 Index on the blockchain) .

- Do students in schools that eliminate grades do better in college and their careers?

- Do students from wealthier backgrounds score higher on standardized tests?

- Do students who receive free meals at school get higher grades compared to when they weren't receiving a free meal?

- Do students who attend charter schools score higher on standardized tests than students in public schools?

- Do students learn better in same-sex classrooms?

- How does giving each student access to an iPad or laptop affect their studies?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Montessori Method ?

- Do children who attend preschool do better in school later on?

- What was the impact of the No Child Left Behind act?

- How does the US education system compare to education systems in other countries?

- What impact does mandatory physical education classes have on students' health?

- Which methods are most effective at reducing bullying in schools?

- Do homeschoolers who attend college do as well as students who attended traditional schools?

- Does offering tenure increase or decrease quality of teaching?

- How does college debt affect future life choices of students?

- Should graduate students be able to form unions?

- What are different ways to lower gun-related deaths in the US?

- How and why have divorce rates changed over time?

- Is affirmative action still necessary in education and/or the workplace?

- Should physician-assisted suicide be legal?

- How has stem cell research impacted the medical field?

- How can human trafficking be reduced in the United States/world?

- Should people be able to donate organs in exchange for money?

- Which types of juvenile punishment have proven most effective at preventing future crimes?

- Has the increase in US airport security made passengers safer?

- Analyze the immigration policies of certain countries and how they are similar and different from one another.

- Several states have legalized recreational marijuana. What positive and negative impacts have they experienced as a result?

- Do tariffs increase the number of domestic jobs?

- Which prison reforms have proven most effective?

- Should governments be able to censor certain information on the internet?

- Which methods/programs have been most effective at reducing teen pregnancy?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Keto diet?

- How effective are different exercise regimes for losing weight and maintaining weight loss?

- How do the healthcare plans of various countries differ from each other?

- What are the most effective ways to treat depression ?

- What are the pros and cons of genetically modified foods?

- Which methods are most effective for improving memory?

- What can be done to lower healthcare costs in the US?

- What factors contributed to the current opioid crisis?

- Analyze the history and impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic .

- Are low-carbohydrate or low-fat diets more effective for weight loss?

- How much exercise should the average adult be getting each week?

- Which methods are most effective to get parents to vaccinate their children?

- What are the pros and cons of clean needle programs?

- How does stress affect the body?

- Discuss the history of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

- What were the causes and effects of the Salem Witch Trials?

- Who was responsible for the Iran-Contra situation?

- How has New Orleans and the government's response to natural disasters changed since Hurricane Katrina?

- What events led to the fall of the Roman Empire?

- What were the impacts of British rule in India ?

- Was the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki necessary?

- What were the successes and failures of the women's suffrage movement in the United States?

- What were the causes of the Civil War?

- How did Abraham Lincoln's assassination impact the country and reconstruction after the Civil War?

- Which factors contributed to the colonies winning the American Revolution?

- What caused Hitler's rise to power?

- Discuss how a specific invention impacted history.

- What led to Cleopatra's fall as ruler of Egypt?

- How has Japan changed and evolved over the centuries?

- What were the causes of the Rwandan genocide ?

- Why did Martin Luther decide to split with the Catholic Church?

- Analyze the history and impact of a well-known cult (Jonestown, Manson family, etc.)

- How did the sexual abuse scandal impact how people view the Catholic Church?

- How has the Catholic church's power changed over the past decades/centuries?

- What are the causes behind the rise in atheism/ agnosticism in the United States?

- What were the influences in Siddhartha's life resulted in him becoming the Buddha?

- How has media portrayal of Islam/Muslims changed since September 11th?

Science/Environment

- How has the earth's climate changed in the past few decades?

- How has the use and elimination of DDT affected bird populations in the US?

- Analyze how the number and severity of natural disasters have increased in the past few decades.

- Analyze deforestation rates in a certain area or globally over a period of time.

- How have past oil spills changed regulations and cleanup methods?

- How has the Flint water crisis changed water regulation safety?

- What are the pros and cons of fracking?

- What impact has the Paris Climate Agreement had so far?

- What have NASA's biggest successes and failures been?

- How can we improve access to clean water around the world?

- Does ecotourism actually have a positive impact on the environment?

- Should the US rely on nuclear energy more?

- What can be done to save amphibian species currently at risk of extinction?

- What impact has climate change had on coral reefs?

- How are black holes created?

- Are teens who spend more time on social media more likely to suffer anxiety and/or depression?

- How will the loss of net neutrality affect internet users?

- Analyze the history and progress of self-driving vehicles.

- How has the use of drones changed surveillance and warfare methods?

- Has social media made people more or less connected?

- What progress has currently been made with artificial intelligence ?

- Do smartphones increase or decrease workplace productivity?

- What are the most effective ways to use technology in the classroom?

- How is Google search affecting our intelligence?

- When is the best age for a child to begin owning a smartphone?

- Has frequent texting reduced teen literacy rates?

How to Write a Great Research Paper

Even great research paper topics won't give you a great research paper if you don't hone your topic before and during the writing process. Follow these three tips to turn good research paper topics into great papers.

#1: Figure Out Your Thesis Early

Before you start writing a single word of your paper, you first need to know what your thesis will be. Your thesis is a statement that explains what you intend to prove/show in your paper. Every sentence in your research paper will relate back to your thesis, so you don't want to start writing without it!

As some examples, if you're writing a research paper on if students learn better in same-sex classrooms, your thesis might be "Research has shown that elementary-age students in same-sex classrooms score higher on standardized tests and report feeling more comfortable in the classroom."

If you're writing a paper on the causes of the Civil War, your thesis might be "While the dispute between the North and South over slavery is the most well-known cause of the Civil War, other key causes include differences in the economies of the North and South, states' rights, and territorial expansion."

#2: Back Every Statement Up With Research

Remember, this is a research paper you're writing, so you'll need to use lots of research to make your points. Every statement you give must be backed up with research, properly cited the way your teacher requested. You're allowed to include opinions of your own, but they must also be supported by the research you give.

#3: Do Your Research Before You Begin Writing

You don't want to start writing your research paper and then learn that there isn't enough research to back up the points you're making, or, even worse, that the research contradicts the points you're trying to make!

Get most of your research on your good research topics done before you begin writing. Then use the research you've collected to create a rough outline of what your paper will cover and the key points you're going to make. This will help keep your paper clear and organized, and it'll ensure you have enough research to produce a strong paper.

What's Next?

Are you also learning about dynamic equilibrium in your science class? We break this sometimes tricky concept down so it's easy to understand in our complete guide to dynamic equilibrium .

Thinking about becoming a nurse practitioner? Nurse practitioners have one of the fastest growing careers in the country, and we have all the information you need to know about what to expect from nurse practitioner school .

Want to know the fastest and easiest ways to convert between Fahrenheit and Celsius? We've got you covered! Check out our guide to the best ways to convert Celsius to Fahrenheit (or vice versa).

These recommendations are based solely on our knowledge and experience. If you purchase an item through one of our links, PrepScholar may receive a commission.

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

65 Argumentative Research Topics For High School Students [PDF Included]

In today’s world, where information is readily available at our fingertips, it’s becoming increasingly important to teach students how to think critically, evaluate sources, and develop persuasive arguments. And one of the best ways to do this is through argumentative research topics.

In high school, students are often encouraged to learn and analyze factual information. However, much like other English and biology research topics , argumentative research topics offer a different kind of challenge. Instead of simply presenting facts, these topics require students to delve into complex issues, think critically, and present their opinions in a clear and convincing manner.

In this article, we will provide a list of compelling argumentative research topics for high school students. From education and politics to social issues and environmental concerns, these topics will challenge students to think deeply, evaluate sources critically, and develop and challenge their skills!

Argumentative research topics: Persuading the student to think and reason harder

Argumentative research topics are a fascinating and exciting way for students to engage in critical thinking and persuasive writing. This type of research topic encourages students to take a stance on a controversial issue and defend it using well-reasoned arguments and evidence. By doing so, students are not only honing their analytical skills and persuasive writing skills, but they are also developing a deeper understanding of their own beliefs and assumptions.

Unlike other research topics that may simply require students to regurgitate facts or summarize existing research, argumentative topics require students to develop and defend their own ideas.

Through argumentative research, students are encouraged to question their own biases and consider alternative perspectives. This type of critical thinking is a vital skill that is essential for success in any academic or professional context. Being able to analyze and evaluate information from different perspectives is an invaluable tool that will serve students well in their future careers.

Furthermore, argumentative research topics, are like writing prompts , which are meant to encourage students to engage in civil discourse and debate. These topics often involve controversial issues that can elicit strong emotions and passionate opinions from individuals with differing viewpoints.

By engaging in respectful, fact-based discussions and debates, students can learn how to engage with people who have different beliefs and opinions

Argumentative Research Topics

- The boundaries of free speech: where should the line be drawn?

- Internet privacy: Should websites and apps be restricted in collecting and utilizing user data?

- Has the internet been a force for progress or a hindrance?

- The role of public surveillance in modern society: is it necessary or invasive?

- Climate change and global warming: Are human activities solely responsible?

- Mandating physical education in schools to combat childhood obesity: Is it effective?

- The ethics of mandatory vaccination for high school students for public health reasons

- The ethics of wearing fur and leather: Is it always unethical?

- Keeping exotic pets: is it acceptable or inhumane?

- The impact of social media on mental health: Is it more positive or negative?

- Wildlife preserves: Are they suitable habitats for all species that reside there?

- Animal fashion: Should it be prohibited?

- Mental health services in schools: Should they be free or reduced-cost for students?

- Quality of high school education: Should teachers undergo regular assessments to ensure it?

- Healthy eating habits in schools: Should schools offer healthier food options in their cafeteria or allow students to bring food from home?

- Social media addiction: Is it a significant health concern for kids?

- Technology use and mental health problems: Is there a connection among high school students?

- Junk food in schools: Should schools ban it from vending machines and school stores to promote healthy eating habits?

- Dress codes in schools: Are they necessary or outdated

- Regulating social media: Should the government regulate it to prevent cyberbullying?

- Politicians and standardized testing: Should politicians be subject to standardized testing?

- Art vs Science: Are they equally challenging fields?

- School uniform and discrimination: Does it really reduce discrimination in schools?

- Teachers and poor academic performance: Are teachers the cause of poor academic performance?

- Physical discipline: Should teachers and parents be allowed to physically discipline their children?

- Telling white lies: Is it acceptable to tell a white lie to spare someone’s feelings?

- Sports in college: Should colleges promote sports as a career path?

- Gender and education: How does gender affect education?

- Refusing medical treatment: Is it acceptable to refuse medical treatment based on personal beliefs?

- Children’s rights and medical treatment: Do doctors violate children’s rights if they do not provide treatment when the parents refuse to treat the child?

- Parental influence on gender stereotypes: Do parents encourage gender stereotypes?

- Dating in schools: Should dating be permitted in schools with supervision?

- Human nature: Are people inherently good or evil by nature?

- Immigration and national economy: Can immigration benefit the national economy?

- Keeping animals in zoos: Is it appropriate?

- Cell phone use in schools: Should cell phone use be permitted in schools?

- Veganism: Should humans only consume vegan food?

- Animal testing: Should it be outlawed?

- Waste segregation: Should the government mandate waste segregation at home?

- Technology integration in schools: Is it beneficial for traditional learning?

- Homeschooling vs traditional schooling: Is homeschooling as effective as traditional schooling?

- Prohibition of smoking and drinking: Should it be permanently prohibited?

- Banning violent and aggressive video games: Should they be banned?

- Harmful effects of beauty standards on society: Are beauty standards harmful to society?

- The impact of advertising on consumer behavior

- The ethical considerations of artificial intelligence and its potential impact on society

- The impact of globalization on cultural diversity

- The effectiveness of alternative medicine in treating various illnesses

- The benefits and drawbacks of online learning compared to traditional classroom education

- The role of mass media in shaping public opinion and political discourse

- The impact of artificial intelligence on job automation and employment rates

- The impact of fast fashion on the environment and human rights

- The ethical considerations of using animals for entertainment purposes

- Parents are solely responsible for their child’s behavior.

- Is space exploration worth it or not?

- stricter regulations on the use of plastic and single-use products to reduce waste

- Is capitalism the best economic system

- Should there be limits on the amount of wealth individuals can accumulate?

- Is it ethical to use animals for food production?

- Is the concept of national borders outdated in the modern era?

- Should the use of nuclear power be expanded or phased out?

- Self-driving cars: Convenience or threat?

- The implications of allowing influencers to advertise dietary supplements and weight loss products.

- Faults in the education system: need change or modification?

- Are the intentions of “big pharma” genuinely aligned with the well-being of the public?

Argumentative research topics are an important tool for promoting critical thinking, and persuasive communication skills and preparing high school students for active engagement in society. These topics challenge students to think deeply and develop persuasive arguments by engaging with complex issues and evaluating sources. Through this process, students can become informed, engaged, and empathetic citizens who are equipped to participate actively in a democratic society.

Furthermore, argumentative research topics teach students how to engage in respectful, fact-based discussions and debates, and how to communicate effectively with people who have different beliefs and opinions. By fostering civil discourse, argumentative research topics can help bridge social, cultural, and political divides, and promote a more united and equitable society.

Overall, argumentative research topics are a crucial component of high school education, as they provide students with the skills and confidence they need to succeed in college, career, and life.

Having a 10+ years of experience in teaching little budding learners, I am now working as a soft skills and IELTS trainers. Having spent my share of time with high schoolers, I understand their fears about the future. At the same time, my experience has helped me foster plenty of strategies that can make their 4 years of high school blissful. Furthermore, I have worked intensely on helping these young adults bloom into successful adults by training them for their dream colleges. Through my blogs, I intend to help parents, educators and students in making these years joyful and prosperous.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

50+ High School Research Paper Topics to Ace Your Grades

Table of contents

- 1 How to Choose High School Research Paper Topics

- 2.1 Education

- 2.2 World history

- 2.3 Mental Health

- 2.4 Science

- 2.6 Healthcare finance research topics

- 2.7 Environmental

- 2.8 Entrepreneurship

- 3 Conclusion

Research papers are common assignments in high school systems worldwide. It is a scientific term that refers to essays where students share what they’ve learned after thoroughly researching one specific topic. Why do high schools impose them?

Writing a well-structured and organized research paper is key to teaching students how to make critical connections, express understanding, summarize data, and communicate findings.

Students don’t only have to come up with several high school research paper topics, choose one, and produce a research paper. A good topic will help you connect with the evaluating public, or in this case, your professors and classmates. However, many students struggle with finding the right high school research topics.

This is why we’ve put together this guide on choosing topics for a high school research paper and over 50 topic ideas you can use or get inspired with.

How to Choose High School Research Paper Topics

Since you are about to go through over 50 high school research topics, you might get overwhelmed. To avoid it, you need to know how to choose the right research paper topic for you.

The most important thing to consider is the time needed to complete a paper on a particular topic. Too broad topics will wear you out, and you might fail to meet the deadline. This is why you should always stick to, shall we say, not-too-broad and well-defined topics.

Since you will spend some time researching and writing, you need to consider your motivation too. Choosing a topic that you find interesting will help you fuel your research and paper writing capabilities. If your efforts turn out to be futile and the deadline is dangerously close, you can always look for a research paper for sale to ace your grade.

Most Interesting & Easy Research Topics for High School students

Since there are many research paper ideas for high school students, we didn’t want to just provide you with a list. Your interest is an essential factor when choosing a topic. This is why we’ve put them in 8 categories. Feel free to jump to a category that you find the most engaging. If you don’t have the time, here at StudyClerk, we are standing by to deliver a completely custom research paper to you.

If you are interested in education, you should consider choosing an education research topic for high school students. Below you can find ten topics you can use as inspiration.

- Should High Schools Impose Mandatory Vaccination On Students?

- The Benefits Of Charter Schools For The Public Education System

- Homeschooling Vs. Traditional Schooling: Which One Better Sets Students For Success

- Should Public Education Continue To Promote Diversity? Why?

- The Most Beneficial Funding Programs For Students

- The Effects Of The Rising Price Of College Tuitions On High School Students

- Discuss The Most Noteworthy Advantages And Disadvantages Of Standardized Testing

- What Are The Alternatives To Standardized Testing?

- Does Gap Year Between High School And College Set Students For Success?

- Identify And Discuss The Major Benefits Of Group Projects For High Schoolers

World history

World history is rich, fun, and engaging. There are numerous attractive topics to choose from. If history is something that has you on your toes, you’ll find the following world history research topics for high school fascinating.

- The Origin Of The Israel-Palestine Conflict And Possible Resolutions

- The History Of The USA Occupation Of Iraq

- Choose A Famous Assassinated World Leader And Discuss What Led To The Assassination

- Discuss A Historical Invention And How It Changed The Lives Of People Worldwide

- Has The World’s Leading Countries’ Response To Climate Change Improved Or Declined Over The Last Decade?

- How The President Of Belarus Manages To Stay In Power For Over 25 Years

- Which Event In World History Had The Most Impact On Your Country?

Mental Health

Many governments worldwide work on increasing mental health awareness. The following mental health topics for high school research papers will put you in a position to contribute to this very important movement.

- Discuss The Main Ways Stress Affects The Body

- Can Daily Exercises Benefit Mental Health? How?

- Should More Counselors Work In High Schools? Why?

- Discuss The Major Factors That Contribute To Poor Mental And Physical Well-Being

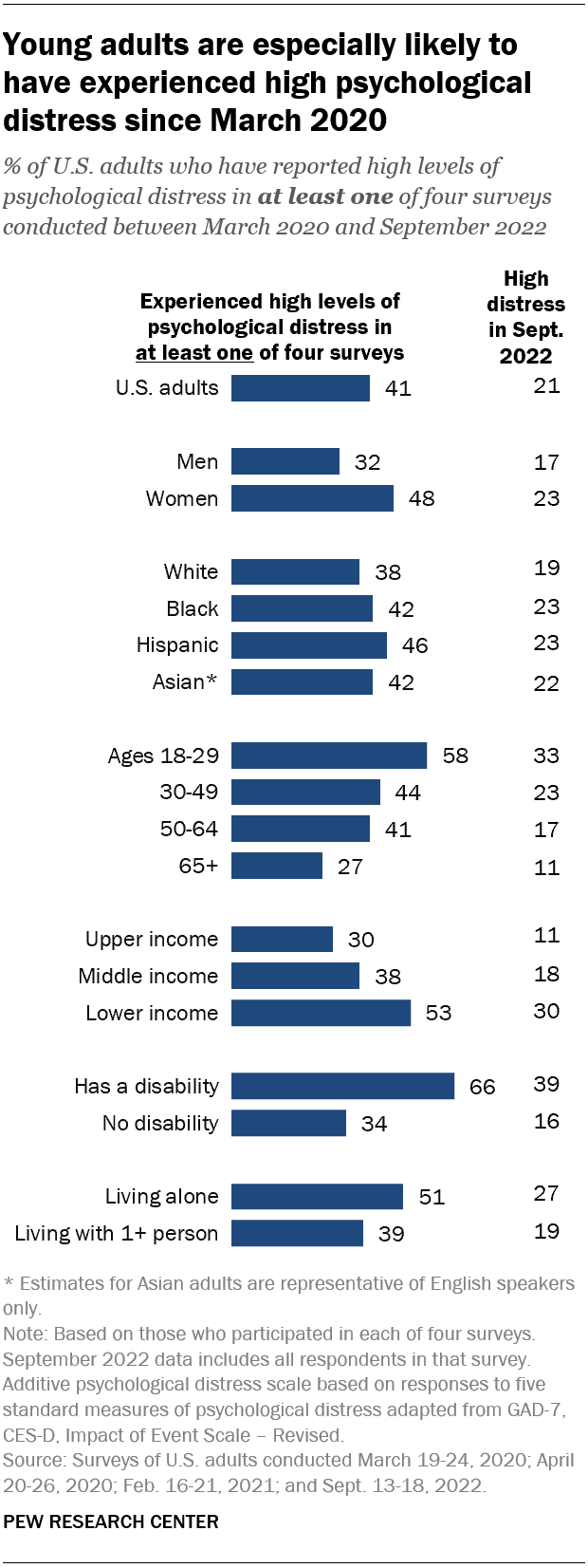

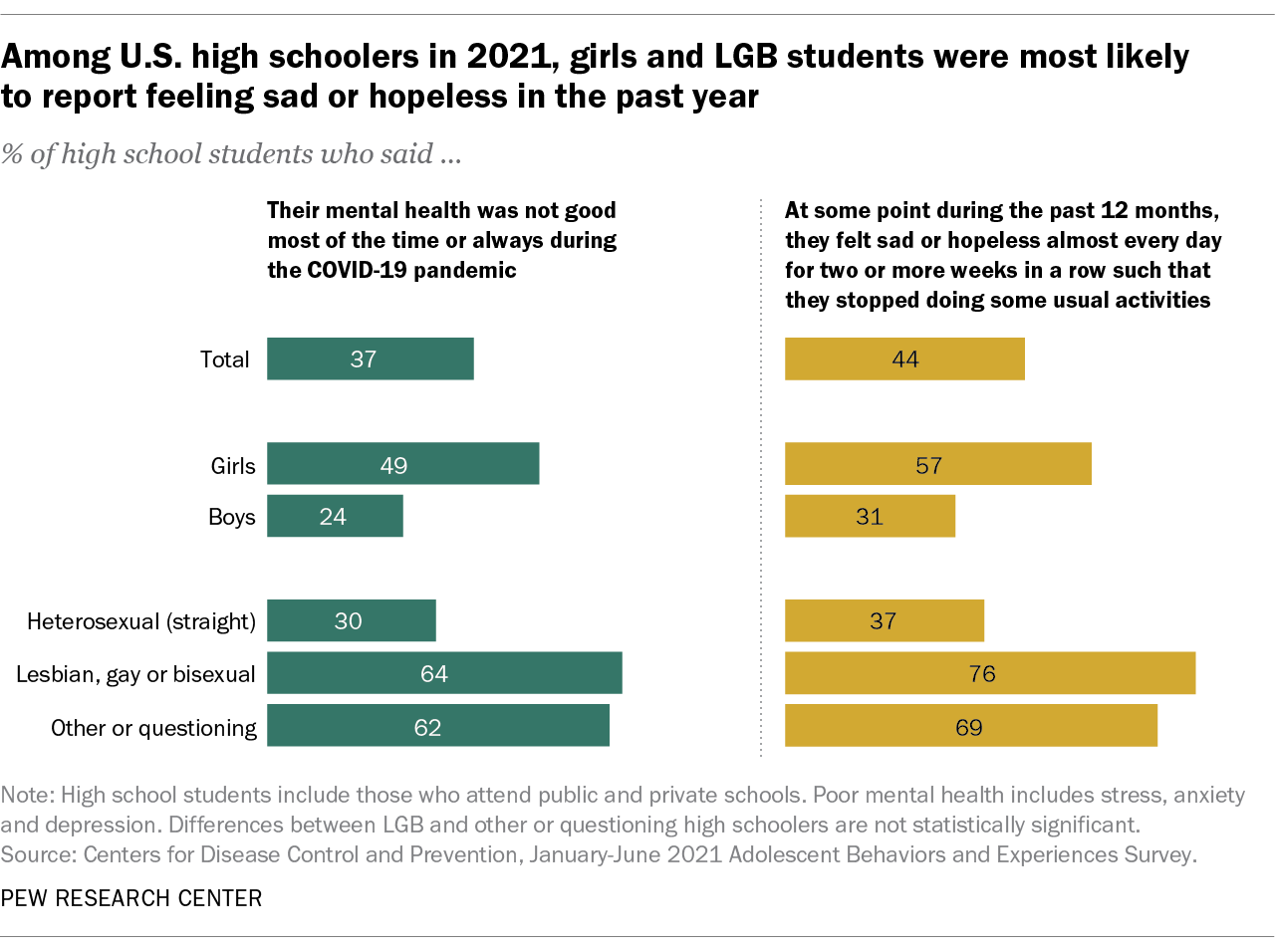

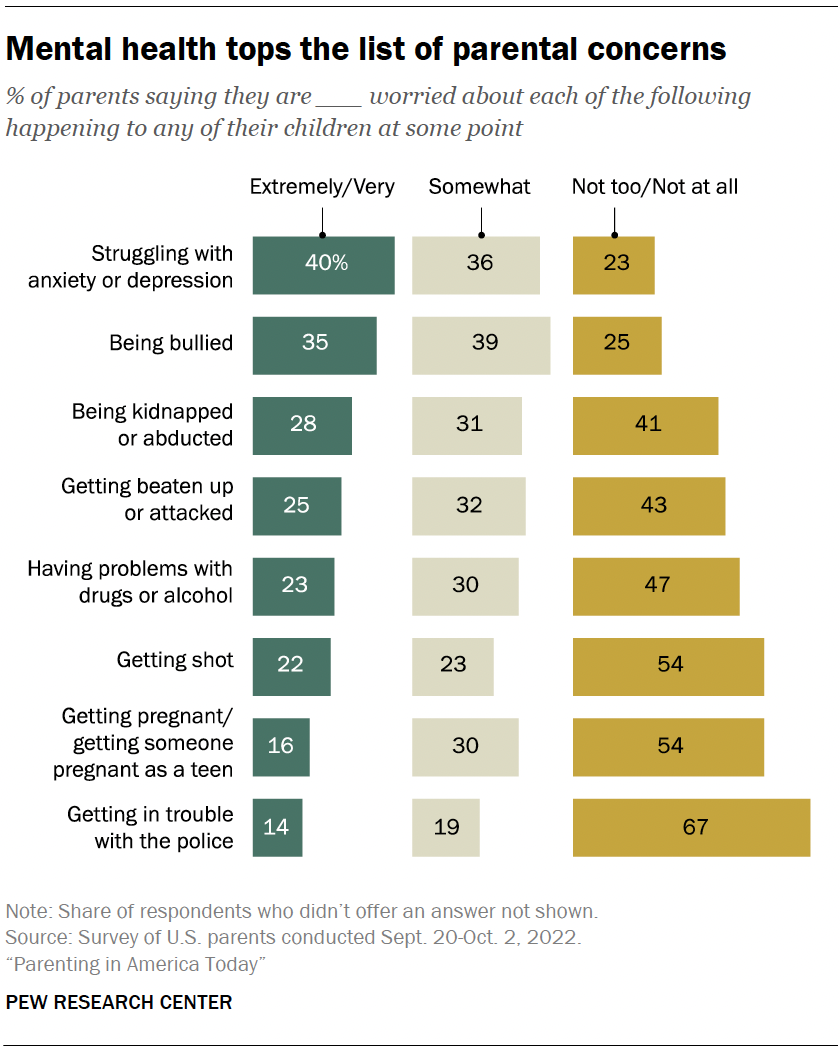

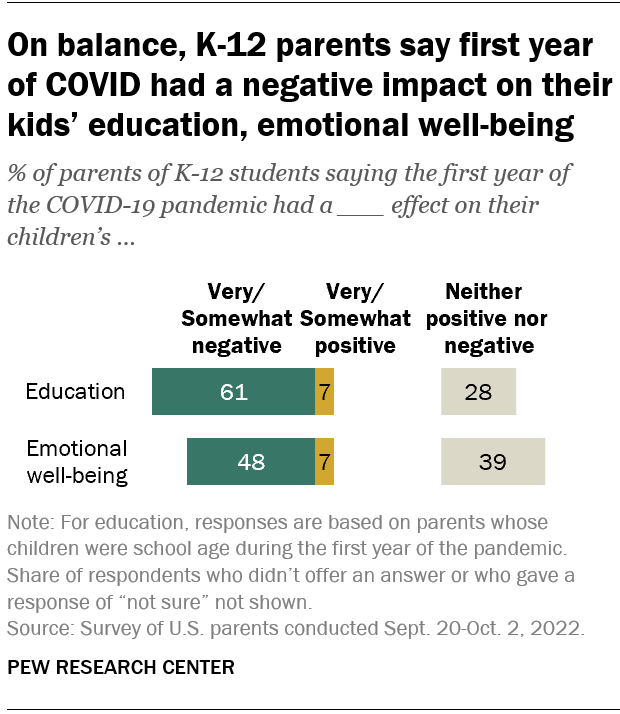

- In What Ways Has The Worldwide Pandemic Affected People’s Mental Health?

- Explore The Relationship Between Social Media And Mental Health Disorders

- How The Public School System Cares For The Mental Health Of Students

- What Is The Most Effective Psychotherapy For High Schoolers?

Science is one of those fields where there is always something new you can research. If you need a science research topic for high school students, feel free to use any of the following.

- How Can Civilization Save Coral Reefs?

- What Are Black Holes, And What Is Their Role?

- Explain Sugar Chemistry That Enables Us To Make Candies

- What Are The Biggest Successes Of The Epa In The Last Decade?

- Is There A Way To Reverse Climate Change? How?

- What Solutions Does Science Offer To Resolve The Drinking Water Crisis In The Future?

Many teenagers find inspiration in music, so why not choose some music high school research paper topics.

- In What Way Music Education Benefits High School Students?

- How Famous Musicians Impact Pop Music

- Classification Of Music Instruments: Discuss The Sachs-Hornbostel System

- Did Sound Effect Technology Change The Music Industry? How?

- How Did Online Streaming Platforms Help Music Evolve?

- How Does Music Software Emulate Sounds Of Different Instruments?

Healthcare finance research topics

Healthcare and finance go hand in hand. Shining light on some exciting correlations between these two fields can be engaging. Here are some topics that you can consider.

- How Can Patient Management Systems Save Money In Hospitals?

- The Pros And Cons Of The Public Healthcare System

- Should Individuals Or The Government Pay For Healthcare?

- What Is Obama-Care And How It Benefits Americans?

- The Most Noteworthy Developments In The History Of Healthcare Financing

Environmental

Our environment has been a hot topic for quite some time now. There is a lot of research to back up your claims and make logical assumptions. Here are some environmental high school research topics you can choose from.

- What Is The Impact Of Offshore Drilling On The Environment?

- Do We Need Climate Change Legislation? Why?

- Are Ecotourism And Tropical Fishing Viable Ways To Save And Recuperate Endangered Areas And Animals?

- The Impact Of Disposable Products On The Environment

- Discuss The Benefits Of Green Buildings To Our Environment

- Find And Discuss A Large-Scale Recent Project That Helped Restore Balance In An Area

Entrepreneurship

Many students struggle with having to find good entrepreneurship research paper ideas for high school. This is why we’ve developed a list of topics to inspire your research.

- What Is Entrepreneurship?

- Are People Born With An Entrepreneurial Spirit, Or Can You Learn It?

- Discuss The Major Entrepreneurship Theories

- Does Entrepreneurship Affect The Growth Of The Economy?

- Which Character Traits Are Commonly Found In Successful Entrepreneurs?

- The Pros And Cons Of Having A Traditional Job And Being An Entrepreneur

- Discuss Entrepreneurship As One Of The Solutions To Unemployment

- What Is Crowdfunding, And How It’s Related To Entrepreneurship

- The Most Common Challenges Entrepreneurs Face

- How Social Media Made A Lot Of Successful Entrepreneurs

Hopefully, you’ll find these high school research paper topics inspirational. The categories are there to help you choose easily. Here at StudyClerk, we know how hard it is to complete all assignments in time and ace all your grades. If you are struggling with writing, feel free to contact us about our writing services, and we’ll help you come on top of your research paper assignment no matter how complex it is.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

Think Like a Researcher: Instruction Resources: #6 Developing Successful Research Questions

- Guide Organization

- Overall Summary

- #1 Think Like a Researcher!

- #2 How to Read a Scholarly Article

- #3 Reading for Keywords (CREDO)

- #4 Using Google for Academic Research

- #4 Using Google for Academic Research (Alternate)

- #5 Integrating Sources

- Research Question Discussion

- #7 Avoiding Researcher Bias

- #8 Understanding the Information Cycle

- #9 Exploring Databases

- #10 Library Session

- #11 Post Library Session Activities

- Summary - Readings

- Summary - Research Journal Prompts

- Summary - Key Assignments

- Jigsaw Readings

- Permission Form

Course Learning Outcome: Develop ability to synthesize and express complex ideas; demonstrate information literacy and be able to work with evidence

Goal: Develop students’ ability to recognize and create successful research questions

Specifically, students will be able to

- identify the components of a successful research question.

- create a viable research question.

What Makes a Good Research Topic Handout

These handouts are intended to be used as a discussion generator that will help students develop a solid research topic or question. Many students start with topics that are poorly articulated, too broad, unarguable, or are socially insignificant. Each of these problems may result in a topic that is virtually un-researchable. Starting with a researchable topic is critical to writing an effective paper.

Research shows that students are much more invested in writing when they are able to choose their own topics. However, there is also research to support the notion that students are completely overwhelmed and frustrated when they are given complete freedom to write about whatever they choose. Providing some structure or topic themes that allow students to make bounded choices may be a way mitigate these competing realities.

These handouts can be modified or edited for your purposes. One can be used as a handout for students while the other can serve as a sample answer key. The document is best used as part of a process. For instance, perhaps starting with discussing the issues and potential research questions, moving on to problems and social significance but returning to proposals/solutions at a later date.

- Research Questions - Handout Key (2 pgs) This document is a condensed version of "What Makes a Good Research Topic". It serves as a key.

- Research Questions - Handout for Students (2 pgs) This document could be used with a class to discuss sample research questions (are they suitable?) and to have them start thinking about problems, social significance, and solutions for additional sample research questions.

- Research Question Discussion This tab includes materials for introduction students to research question criteria for a problem/solution essay.

Additional Resources

These documents have similarities to those above. They represent original documents and conversations about research questions from previous TRAIL trainings.

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? - Original Handout (4 pgs)

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? Revised Jan. 2016 (4 pgs)

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? Revised Jan 2016 with comments

Topic Selection (NCSU Libraries)

Howard, Rebecca Moore, Tricia Serviss, and Tanya K. Rodrigues. " Writing from sources, writing from sentences ." Writing & Pedagogy 2.2 (2010): 177-192.

Research Journal

Assign after students have participated in the Developing Successful Research Topics/Questions Lesson OR have drafted a Research Proposal.

Think about your potential research question.

- What is the problem that underlies your question?

- Is the problem of social significance? Explain.

- Is your proposed solution to the problem feasible? Explain.

- Do you think there is evidence to support your solution?

Keys for Writers - Additional Resource

Keys for Writers (Raimes and Miller-Cochran) includes a section to guide students in the formation of an arguable claim (thesis). The authors advise students to avoid the following since they are not debatable.

- "a neutral statement, which gives no hint of the writer's position"

- "an announcement of the paper's broad subject"

- "a fact, which is not arguable"

- "a truism (statement that is obviously true)"

- "a personal or religious conviction that cannot be logically debated"

- "an opinion based only on your feelings"

- "a sweeping generalization" (Section 4C, pg. 52)

The book also provides examples and key points (pg. 53) for a good working thesis.

- << Previous: #5 Integrating Sources

- Next: Research Question Discussion >>

- Last Updated: Sep 29, 2023 2:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/think_like_a_researcher

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write a Research Paper in High School

What’s covered:, how to pick a compelling research paper topic, how to format your research paper, tips for writing a research paper, do research paper grades impact your college chances.

A research paper can refer to a broad range of expanded essays used to explain your interpretation of a topic. This task is highly likely to be a common assignment in high school , so it’s always better to get a grasp on this sooner than later. Getting comfortable writing research papers does not have to be difficult, and can actually be pretty interesting when you’re genuinely intrigued by what you’re researching.

Regardless of what kind of research paper you are writing, getting started with a topic is the first step, and sometimes the hardest step. Here are some tips to get you started with your paper and get the writing to begin!

Pick A Topic You’re Genuinely Interested In

Nothing comes across as half-baked as much as a topic that is evidently uninteresting, not to the reader, but the writer. You can only get so far with a topic that you yourself are not genuinely happy writing, and this lack of enthusiasm cannot easily be created artificially. Instead, read about things that excite you, such as some specific concepts about the structure of atoms in chemistry. Take what’s interesting to you and dive further with a research paper.

If you need some ideas, check out our post on 52 interesting research paper topics .

The Topic Must Be A Focal Point

Your topic can almost be considered as the skeletal structure of the research paper. But in order to better understand this we need to understand what makes a good topic. Here’s an example of a good topic:

How does the amount of pectin in a vegetable affect its taste and other qualities?

This topic is pretty specific in explaining the goals of the research paper. If I had instead written something more vague such as Factors that affect taste in vegetables , the scope of the research immediately increased to a more herculean task simply because there is more to write about, some of which is overtly unnecessary. This is avoided by specifications in the topic that help guide the writer into a focused path.

By creating this specific topic, we can route back to it during the writing process to check if we’re addressing it often, and if we are then our writing is going fine! Otherwise, we’d have to reevaluate the progression of our paper and what to change. A good topic serves as a blueprint for writing the actual essay because everything you need to find out is in the topic itself, it’s almost like a sort of plan/instruction.

Formatting a research paper is important to not only create a “cleaner” more readable end product, but it also helps streamline the writing process by making it easier to navigate. The following guidelines on formatting are considered a standard for research papers, and can be altered as per the requirements of your specific assignments, just check with your teacher/grader!

Start by using a standard font like Times New Roman or Arial, in 12 or 11 sized font. Also, add one inch margins for the pages, along with some double spacing between lines. These specifications alone get you started on a more professional and cleaner looking research paper.

Paper Citations

If you’re creating a research paper for some sort of publication, or submission, you must use citations to refer to the sources you’ve used for the research of your topic. The APA citation style, something you might be familiar with, is the most popular citation style and it works as follows:

Author Last Name, First Initial, Publication Year, Book/Movie/Source title, Publisher/Organization

This can be applied to any source of media/news such as a book, a video, or even a magazine! Just make sure to use citation as much as possible when using external data and sources for your research, as it could otherwise land you in trouble with unwanted plagiarism.

Structuring The Paper

Structuring your paper is also important, but not complex either. Start by creating an introductory paragraph that’s short and concise, and tells the reader what they’re going to be reading about. Then move onto more contextual information and actual presentation of research. In the case of a paper like this, you could start with stating your hypothesis in regard to what you’re researching, or even state your topic again with more clarification!

As the paper continues you should be bouncing between views that support and go against your claim/hypothesis to maintain a neutral tone. Eventually you will reach a conclusion on whether or not your hypothesis was valid, and from here you can begin to close the paper out with citations and reflections on the research process.

Talk To Your Teacher

Before the process of searching for a good topic, start by talking to your teachers first! You should form close relations with them so they can help guide you with better inspiration and ideas.

Along the process of writing, you’re going to find yourself needing help when you hit walls. Specifically there will be points at which the scope of your research could seem too shallow to create sizable writing off of it, therefore a third person point of view could be useful to help think of workarounds in such situations.

You might be writing a research paper as a part of a submission in your applications to colleges, which is a great way to showcase your skills! Therefore, to really have a good chance to showcase yourself as a quality student, aim for a topic that doesn’t sell yourself short. It would be easier to tackle a topic that is not as intense to research, but the end results would be less worthwhile and could come across as lazy. Focus on something genuinely interesting and challenging so admissions offices know you are a determined and hard-working student!

Don’t Worry About Conclusions

The issue many students have with writing research papers, is that they aren’t satisfied with arriving at conclusions that do not support their original hypothesis. It’s important to remember that not arriving at a specific conclusion that your hypothesis was planning on, is totally fine! The whole point of a research paper is not to be correct, but it’s to showcase the trial and error behind learning and understanding something new.

If your findings clash against your initial hypothesis, all that means is you’ve arrived at a new conclusion that can help form a new hypothesis or claim, with sound reasoning! Getting rid of this mindset that forces you to warp around your hypothesis and claims can actually improve your research writing by a lot!

Colleges won’t ever see the grades for individual assignments, but they do care a bit more about the grades you achieve in your courses. Research papers may play towards your overall course grade based on the kind of class you’re in. Therefore to keep those grades up, you should try your absolute best on your essays and make sure they get high-quality reviews to check them too!

Luckily, CollegeVine’s peer review for essays does exactly that! This great feature allows you to get your essay checked by other users, and hence make a higher-quality essay that boosts your chances of admission into a university.

Want more info on your chances for college admissions? Check out CollegeVine’s admissions calculator, an intuitive tool that takes numerous factors into account as inputs before generating your unique chance of admission into an institute of your selection!

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

High school research writing: Getting started

by Misti Lacy | Feb 19, 2019 | College Prep , Essays & Research Papers , High school

This post contains affiliate links. Read our full disclosure policy .

Does the idea of high school research writing make you tremble? In this three-part series, I’ll walk you through the WHO, WHAT, WHEN, WHERE, and HOW of high school research writing, sharing tips and tricks I have learned during 25 years of teaching.

Juniors and seniors should tackle at least one substantial persuasive expository research paper before heading to college. Let’s get started!

Who should tackle a substantial research paper?

Because of the critical thinking and organization involved, this assignment must be reserved for older teens who have a solid foundation in five-paragraph essays and sentence structure . They should have already completed some research projects for essays or oral presentations.

If your student needs confidence in his or her writing skills, stop the presses and hit WriteShop I and WriteShop II . Older teens can zoom through the lessons in this curriculum and gain that solid foundation.

WriteShop I works on descriptive writing, sentence structure, and paragraph structure. WriteShop II allows the students to write persuasively, do some smaller research assignments, and gain experience in writing essays .

(For the sake of our discussion on high school research writing, I assume students have completed WriteShop I and II, or the equivalent.)

What should a high school research paper include?

- 1750-2500 word (7-10 page) persuasive exposition

- Reference page

- MLA or APA format

- At least 7 credible academic sources (.edu, .gov, .org)

What formatting should we use?

Not only must your teens know how to write well, they will also need to format their papers using a specific style , most commonly MLA and APA formatting .

Because college professors do not explain them, make sure students know the basics of these nationally accepted formats.

Details matter! Students must follow the guidelines for margins, reference pages, and in-text citations.

What research topics should we choose?

High school research writing gives teens the opportunity to choose relevant topics—and allows them to dig into and study those hard subjects for themselves. For instance:

Urban gardening Any current political issue Veganism Gun control Music education Recycling Computer gaming

Global warming Abortion Homeschooling Any one aspect of transhumanism Junk food Legalization of medical or recreational marijuana

Once he’s chosen a research topic, your student must choose a position and defend it with expert opinions, and call the reader to action.

Have fun—and don’t shy away from controversial “hot” topics ! Journal All Year Teen! Writing Prompt Calendar contains dozens of argumentative and persuasive topics to challenge your student.

This season of homeschooling presents a perfect time for your kids to study and make some decisions for themselves while you are around to give your input.

Pick a time and a place to do research writing—and stick with it. Using a calendar, decide together on dates for small deadlines . For example:

- Notes from three resources by March 1st

- Rough draft complete by March 25th

Meeting deadlines is a learned skill . Dock the grade if your teen has not met each stepping stone.

Students must have room to keep reference material organized and handy . If you have younger children, allowing your teen to wear noise-canceling headphones is a good idea.

When my kids worked on their research papers, I set up a long folding table in the middle of the living room. The computer, notes, books, and printed resources all stayed on the table until the project was finished.

Not surprisingly, my kids focused better in our living room than they did in a bedroom, where gaming or social media distracted them . Also, I could pop in and help them find sources or discuss an issue when they camped out next to the kitchen.

At a coffee shop

I feel “grown-up” when I work from a coffee shop. The general background noise of a coffee shop keeps me productive , whereas, noise from my family distracts me.

At the library

Ask for a study room; they’re great. Libraries, which have free Wi-Fi, allow you to talk (and sometimes even bring snacks and drinks) in study rooms. Plus, with reference materials and a helpful librarian just a few steps away, the library makes an ideal place to focus on research .

At home. In a cozy coffee shop. At your local library. Really, the WHERE can be anywhere these days.

Enjoy this season of homeschooling and come back next time when we delve into the HOW of high school research writing.

As WriteShop’s curriculum consultant , Misti Lacy draws from her years of experience as a veteran writing teacher and homeschool mom to help you build a solid writing foundation. Whether you’re deciding on products for your family , exploring our program for your school or co-op , or needing someone to walk you through your WriteShop curriculum, Misti is your girl! She has a heart for building relationships with you and your kids, and through her warm encouragement, she takes the fear out of teaching writing.

Contact Misti today! She’s delighted to walk with you along your WriteShop journey.

Essay writing skills lie at the foundation of research writing. WriteShop I teaches strong paragraph writing and more mature sentence structure. These skills pave the way for students to learn five-paragraph essay writing in WriteShop II .

To learn more about the WriteShop I and II program from a real mom, check out this video by Annie and Everything .

Let’s Stay Connected!

Subscribe to our newsletter.

- Gift Guides

- Reluctant or Struggling Writers

- Special Needs Writers

- Brainstorming Help

- Editing & Grading Help

- Encouragement for Moms

- Writing Games & Activities

- Writing for All Subjects

- Essays & Research Papers

- College Prep Writing

- Grammar & Spelling

- Writing Prompts

Recent Posts

- An exciting announcement!

- 10 Stumbling Blocks to Writing in Your Homeschool

- Help kids with learning challenges succeed at homeschool writing

- How to correct writing lessons without criticizing your child

How to Write a Research Paper as a High School Student

By Carly Taylor

Senior at Stanford University

6 minute read

Read our guide to learn why you should write a research paper and how to do so, from choosing the right topic to outlining and structuring your argument.

What is a research paper?

A research paper poses an answer to a specific question and defends that answer using academic sources, data, and critical reasoning. Writing a research paper is an excellent way to hone your focus during a research project , synthesize what you’re learning, and explain why your work matters to a broader audience of scholars in your field.

The types of sources and evidence you’ll see used in a research paper can vary widely based on its field of study. A history research paper might examine primary sources like journals and newspaper articles to draw conclusions about the culture of a specific time and place, whereas a biology research paper might analyze data from different published experiments and use textbook explanations of cellular pathways to identify a potential marker for breast cancer.

However, researchers across disciplines must identify and analyze credible sources, formulate a specific research question, generate a clear thesis statement, and organize their ideas in a cohesive manner to support their argument. Read on to learn how this process works and how to get started writing your own research paper.

Choosing your topic

Tap into your passions.

A research paper is your chance to explore what genuinely interests you and combine ideas in novel ways. So don’t choose a subject that simply sounds impressive or blindly follow what someone else wants you to do – choose something you’re really passionate about! You should be able to enjoy reading for hours and hours about your topic and feel enthusiastic about synthesizing and sharing what you learn.

We've created these helpful resources to inspire you to think about your own passion project . Polygence also offers a passion exploration experience where you can dive deep into three potential areas of study with expert mentors from those fields.

Ask a difficult question

In the traditional classroom, top students are expected to always know the answers to the questions the teacher asks. But a research paper is YOUR chance to pose a big question that no one has answered yet, and figure out how to make a contribution to answering that question. So don’t be afraid if you have no idea how to answer your question at the start of the research process — this will help you maintain a motivational sense of discovery as you dive deeper into your research. If you need inspiration, explore our database of research project ideas .

Be as specific as possible

It’s essential to be reasonable about what you can accomplish in one paper and narrow your focus down to an issue you can thoroughly address. For example, if you’re interested in the effects of invasive species on ecosystems, it’s best to focus on one invasive species and one ecosystem, such as iguanas in South Florida , or one survival mechanism, such as supercolonies in invasive ant species . If you can, get hands on with your project.

You should approach your paper with the mindset of becoming an expert in this topic. Narrowing your focus will help you achieve this goal without getting lost in the weeds and overwhelming yourself.

Would you like to write your own research paper?

Polygence mentors can help you every step of the way in writing and showcasing your research paper

Preparing to write

Conduct preliminary research.

Before you dive into writing your research paper, conduct a literature review to see what’s already known about your topic. This can help you find your niche within the existing body of research and formulate your question. For example, Polygence student Jasmita found that researchers had studied the effects of background music on student test performance, but they had not taken into account the effect of a student’s familiarity with the music being played, so she decided to pose this new question in her research paper.

Pro tip: It’s a good idea to skim articles in order to decide whether they’re relevant enough to your research interest before committing to reading them in full. This can help you spend as much time as possible with the sources you’ll actually cite in your paper.

Skimming articles will help you gain a broad-strokes view of the different pockets of existing knowledge in your field and identify the most potentially useful sources. Reading articles in full will allow you to accumulate specific evidence related to your research question and begin to formulate an answer to it.

Draft a thesis statement

Your thesis statement is your succinctly-stated answer to the question you’re posing, which you’ll make your case for in the body of the paper. For example, if you’re studying the effect of K-pop on eating disorders and body image in teenagers of different races, your thesis may be that Asian teenagers who are exposed to K-pop videos experience more negative effects on their body image than Caucasian teenagers.

Pro Tip: It’s okay to refine your thesis as you continue to learn more throughout your research and writing process! A preliminary thesis will help you come up with a structure for presenting your argument, but you should absolutely change your thesis if new information you uncover changes your perspective or adds nuance to it.

Create an outline

An outline is a tool for sketching out the structure of your paper by organizing your points broadly into subheadings and more finely into individual paragraphs. Try putting your thesis at the top of your outline, then brainstorm all the points you need to convey in order to support your thesis.

Pro Tip : Your outline is just a jumping-off point – it will evolve as you gain greater clarity on your argument through your writing and continued research. Sometimes, it takes several iterations of outlining, then writing, then re-outlining, then rewriting in order to find the best structure for your paper.

Writing your paper

Introduction.

Your introduction should move the reader from your broad area of interest into your specific area of focus for the paper. It generally takes the form of one to two paragraphs that build to your thesis statement and give the reader an idea of the broad argumentative structure of your paper. After reading your introduction, your reader should know what claim you’re going to present and what kinds of evidence you’ll analyze to support it.

Topic sentences

Writing crystal clear topic sentences is a crucial aspect of a successful research paper. A topic sentence is like the thesis statement of a particular paragraph – it should clearly state the point that the paragraph will make. Writing focused topic sentences will help you remain focused while writing your paragraphs and will ensure that the reader can clearly grasp the function of each paragraph in the paper’s overall structure.

Transitions

Sophisticated research papers move beyond tacking on simple transitional phrases such as “Secondly” or “Moreover” to the start of each new paragraph. Instead, each paragraph flows naturally into the next one, with the connection between each idea made very clear. Try using specifically-crafted transitional phrases rather than stock phrases to move from one point to the next that will make your paper as cohesive as possible.

In her research paper on Pakistani youth in the U.S. , Polygence student Iba used the following specifically-crafted transition to move between two paragraphs: “Although the struggles of digital ethnography limited some data collection, there are also many advantages of digital data collection.” This sentence provides the logical link between the discussion of the limitations of digital ethnography from the prior paragraph and the upcoming discussion of this techniques’ advantages in this paragraph.

Your conclusion can have several functions:

To drive home your thesis and summarize your argument

To emphasize the broader significance of your findings and answer the “so what” question

To point out some questions raised by your thesis and/or opportunities for further research

Your conclusion can take on all three of these tasks or just one, depending on what you feel your paper is still lacking up to this point.

Citing sources

Last but not least, giving credit to your sources is extremely important. There are many different citation formats such as MLA, APA, and Chicago style. Make sure you know which one is standard in your field of interest by researching online or consulting an expert.

You have several options for keeping track of your bibliography:

Use a notebook to record the relevant information from each of your sources: title, author, date of publication, journal name, page numbers, etc.

Create a folder on your computer where you can store your electronic sources

Use an online bibliography creator such as Zotero, Easybib, or Noodletools to track sources and generate citations

You can read research papers by Polygence students under our Projects tab. You can also explore other opportunities for high school research .

If you’re interested in finding an expert mentor to guide you through the process of writing your own independent research paper, consider applying to be a Polygence scholar today!

Your research paper help even you to earn college credit , get published in an academic journal , contribute to your application for college , improve your college admissions chances !

Feeling Inspired?

Interested in doing an exciting research project? Click below to get matched with one of our expert mentors!

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

student opinion

130 New Prompts for Argumentative Writing

Questions on everything from mental health and sports to video games and dating. Which ones inspire you to take a stand?

By The Learning Network

Note: We have an updated version of this list, with 300 new argumentative writing prompts .

What issues do you care most about? What topics do you find yourself discussing passionately, whether online, at the dinner table, in the classroom or with your friends?

In Unit 5 of our free yearlong writing curriculum and related Student Editorial Contest , we invite students to research and write about the issues that matter to them, whether that’s Shakespeare , health care , standardized testing or being messy .

But with so many possibilities, where does one even begin? Try our student writing prompts.

In 2017, we compiled a list of 401 argumentative writing prompts , all drawn from our daily Student Opinion column . Now, we’re rounding up 130 more we’ve published since then ( available here as a PDF ). Each prompt links to a free Times article as well as additional subquestions that can help you think more deeply about it.

You might use this list to inspire your own writing and to find links to reliable resources about the issues that intrigue you. But even if you’re not participating in our contest, you can use these prompts to practice the kind of low-stakes writing that can help you hone your argumentation skills.

So scroll through the list below with questions on everything from sports and mental health to dating and video games and see which ones inspire you to take a stand.

Please note: Many of these prompts are still open to comment by students 13 and up.

Technology & Social Media

1. Do Memes Make the Internet a Better Place? 2. Does Online Public Shaming Prevent Us From Being Able to Grow and Change? 3. How Young Is Too Young to Use Social Media? 4. Should the Adults in Your Life Be Worried by How Much You Use Your Phone? 5. Is Your Phone Love Hurting Your Relationships? 6. Should Kids Be Social Media Influencers? 7. Does Grammar Still Matter in the Age of Twitter? 8. Should Texting While Driving Be Treated Like Drunken Driving? 9. How Do You Think Technology Affects Dating?

10. Are Straight A’s Always a Good Thing? 11. Should Schools Teach You How to Be Happy? 12. How Do You Think American Education Could Be Improved? 13. Should Schools Test Their Students for Nicotine and Drug Use? 14. Can Social Media Be a Tool for Learning and Growth in Schools? 15. Should Facial Recognition Technology Be Used in Schools? 16. Should Your School Day Start Later? 17. How Should Senior Year in High School Be Spent? 18. Should Teachers Be Armed With Guns? 19. Is School a Place for Self-Expression? 20. Should Students Be Punished for Not Having Lunch Money? 21. Is Live-Streaming Classrooms a Good Idea? 22. Should Gifted and Talented Education Be Eliminated? 23. What Are the Most Important Things Students Should Learn in School? 24. Should Schools Be Allowed to Censor Student Newspapers? 25. Do You Feel Your School and Teachers Welcome Both Conservative and Liberal Points of View? 26. Should Teachers and Professors Ban Student Use of Laptops in Class? 27. Should Schools Teach About Climate Change? 28. Should All Schools Offer Music Programs? 29. Does Your School Need More Money? 30. Should All Schools Teach Cursive? 31. What Role Should Textbooks Play in Education? 32. Do Kids Need Recess?

College & Career

33. What Is Your Reaction to the College Admissions Cheating Scandal? 34. Is the College Admissions Process Fair? 35. Should Everyone Go to College? 36. Should College Be Free? 37. Are Lavish Amenities on College Campuses Useful or Frivolous? 38. Should ‘Despised Dissenters’ Be Allowed to Speak on College Campuses? 39. How Should the Problem of Sexual Assault on Campuses Be Addressed? 40. Should Fraternities Be Abolished? 41. Is Student Debt Worth It?

Mental & Physical Health

42. Should Students Get Mental Health Days Off From School? 43. Is Struggle Essential to Happiness? 44. Does Every Country Need a ‘Loneliness Minister’? 45. Should Schools Teach Mindfulness? 46. Should All Children Be Vaccinated? 47. What Do You Think About Vegetarianism? 48. Do We Worry Too Much About Germs? 49. What Advice Should Parents and Counselors Give Teenagers About Sexting? 50. Do You Think Porn Influences the Way Teenagers Think About Sex?

Race & Gender

51. How Should Parents Teach Their Children About Race and Racism? 52. Is America ‘Backsliding’ on Race? 53. Should All Americans Receive Anti-Bias Education? 54. Should All Companies Require Anti-Bias Training for Employees? 55. Should Columbus Day Be Replaced With Indigenous Peoples Day? 56. Is Fear of ‘The Other’ Poisoning Public Life? 57. Should the Boy Scouts Be Coed? 58. What Is Hard About Being a Boy?

59. Can You Separate Art From the Artist? 60. Are There Subjects That Should Be Off-Limits to Artists, or to Certain Artists in Particular? 61. Should Art Come With Trigger Warnings? 62. Should Graffiti Be Protected? 63. Is the Digital Era Improving or Ruining the Experience of Art? 64. Are Museums Still Important in the Digital Age? 65. In the Age of Digital Streaming, Are Movie Theaters Still Relevant? 66. Is Hollywood Becoming More Diverse? 67. What Stereotypical Characters Make You Cringe? 68. Do We Need More Female Superheroes? 69. Do Video Games Deserve the Bad Rap They Often Get? 70. Should Musicians Be Allowed to Copy or Borrow From Other Artists? 71. Is Listening to a Book Just as Good as Reading It? 72. Is There Any Benefit to Reading Books You Hate?

73. Should Girls and Boys Sports Teams Compete in the Same League? 74. Should College Athletes Be Paid? 75. Are Youth Sports Too Competitive? 76. Is It Selfish to Pursue Risky Sports Like Extreme Mountain Climbing? 77. How Should We Punish Sports Cheaters? 78. Should Technology in Sports Be Limited? 79. Should Blowouts Be Allowed in Youth Sports? 80. Is It Offensive for Sports Teams and Their Fans to Use Native American Names, Imagery and Gestures?

81. Is It Wrong to Focus on Animal Welfare When Humans Are Suffering? 82. Should Extinct Animals Be Resurrected? If So, Which Ones? 83. Are Emotional-Support Animals a Scam? 84. Is Animal Testing Ever Justified? 85. Should We Be Concerned With Where We Get Our Pets? 86. Is This Exhibit Animal Cruelty or Art?

Parenting & Childhood

87. Who Should Decide Whether a Teenager Can Get a Tattoo or Piercing? 88. Is It Harder to Grow Up in the 21st Century Than It Was in the Past? 89. Should Parents Track Their Teenager’s Location? 90. Is Childhood Today Over-Supervised? 91. How Should Parents Talk to Their Children About Drugs? 92. What Should We Call Your Generation? 93. Do Other People Care Too Much About Your Post-High School Plans? 94. Do Parents Ever Cross a Line by Helping Too Much With Schoolwork? 95. What’s the Best Way to Discipline Children? 96. What Are Your Thoughts on ‘Snowplow Parents’? 97. Should Stay-at-Home Parents Be Paid? 98. When Do You Become an Adult?

Ethics & Morality

99. Why Do Bystanders Sometimes Fail to Help When They See Someone in Danger? 100. Is It Ethical to Create Genetically Edited Humans? 101. Should Reporters Ever Help the People They Are Covering? 102. Is It O.K. to Use Family Connections to Get a Job? 103. Is $1 Billion Too Much Money for Any One Person to Have? 104. Are We Being Bad Citizens If We Don’t Keep Up With the News? 105. Should Prisons Offer Incarcerated People Education Opportunities? 106. Should Law Enforcement Be Able to Use DNA Data From Genealogy Websites for Criminal Investigations? 107. Should We Treat Robots Like People?

Government & Politics

108. Does the United States Owe Reparations to the Descendants of Enslaved People? 109. Do You Think It Is Important for Teenagers to Participate in Political Activism? 110. Should the Voting Age Be Lowered to 16? 111. What Should Lawmakers Do About Guns and Gun Violence? 112. Should Confederate Statues Be Removed or Remain in Place? 113. Does the U.S. Constitution Need an Equal Rights Amendment? 114. Should National Monuments Be Protected by the Government? 115. Should Free Speech Protections Include Self Expression That Discriminates? 116. How Important Is Freedom of the Press? 117. Should Ex-Felons Have the Right to Vote? 118. Should Marijuana Be Legal? 119. Should the United States Abolish Daylight Saving Time? 120. Should We Abolish the Death Penalty? 121. Should the U.S. Ban Military-Style Semiautomatic Weapons? 122. Should the U.S. Get Rid of the Electoral College? 123. What Do You Think of President Trump’s Use of Twitter? 124. Should Celebrities Weigh In on Politics? 125. Why Is It Important for People With Different Political Beliefs to Talk to Each Other?

Other Questions

126. Should the Week Be Four Days Instead of Five? 127. Should Public Transit Be Free? 128. How Important Is Knowing a Foreign Language? 129. Is There a ‘Right Way’ to Be a Tourist? 130. Should Your Significant Other Be Your Best Friend?

The Complete Guide to Independent Research Projects for High School Students

Indigo Research Team

If you want to get into top universities, an independent research project will give your application the competitive edge it needs.

Writing and publishing independent research during high school lets you demonstrate to top colleges and universities that you can deeply inquire into a topic, think critically, and produce original analysis. In fact, MIT features "Research" and "Maker" portfolio sections in its application, highlighting the value it places on self-driven projects.

Moreover, successfully executing high-quality research shows potential employers that you can rise to challenges, manage your time, contribute new ideas, and work independently.

This comprehensive guide will walk you through everything you need to know to take on independent study ideas and succeed. You’ll learn how to develop a compelling topic, conduct rigorous research, and ultimately publish your findings.

.png)

What is an Independent Research Project?

An independent research project is a self-directed investigation into an academic question or topic that interests you. Unlike projects assigned by teachers in class, independent research will allow you to explore your curiosity and passions.

These types of projects can vary widely between academic disciplines and scientific fields, but what connects them is a step-by-step approach to answering a research question. Specifically, you will have to collect and analyze data and draw conclusions from your analysis.

For a high school student, carrying out quality research may still require some mentorship from a teacher or other qualified scholar. But the project research ideas should come from you, the student. The end goal is producing original research and analysis around a topic you care about.

Some key features that define an independent study project include:

● Formulating your own research question

● Designing the methodology

● Conducting a literature review of existing research

● Gathering and analyzing data, and

● Communicating your findings.

The topic and scope may be smaller than a professional college academic project, but the process and skills learned have similar benefits.

Why Should High School Students Do Independent Research?

High school students who engage in independent study projects gain valuable skills and experiences that benefit and serve them well in their college and career pursuits. Here's a breakdown of what you will typically acquire:

Develop Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving Skills

Research and critical thinking are among the top 10 soft skills in demand in 2024 . They help you solve new challenges quickly and come up with alternative solutions

An independent project will give you firsthand experience with essential research skills like forming hypotheses, designing studies, collecting and analyzing data, and interpreting results. These skills will serve you well in college and when employed in any industry.

Stand Out for College Applications

With many applicants having similar GPAs and test scores, an Independent research study offer a chance to stand out from the crowd. Completing a research study in high school signals colleges that you are self-motivated and capable of high-level work. Showcasing your research process, findings, and contributions in your application essays or interviews can boost your application's strengths in top-level colleges and universities.

Earn Scholarship Opportunities

Completing an independent research project makes you a more preferred candidate for merit-based scholarships, especially in STEM fields. Many scholarships reward students who show initiative by pursuing projects outside of class requirements. Your research project ideas will demonstrate your skills and motivation to impress scholarship committees. For example, the Siemens Competition in Math, Science & Technology rewards students with original independent research projects in STEM fields. Others include the Garcia Summer Program and the BioGENEius challenge for life sciences.

Gain Subject Area Knowledge

Independent projects allow you to immerse yourself in a topic you genuinely care about beyond what is covered in the classroom. It's a chance to become an expert in something you're passionate about . You will build deep knowledge in the topic area you choose to research, which can complement what you're learning in related classes. This expertise can even help inform your career interests and goals.

Develop Time Management Skills