Poverty: The Main Causes and Factors Essay

At the moment, there is a great deal of debate in the scientific community as to what exactly should be considered poverty. Because of the constant process of societal development, the concept of poverty changes rapidly, adapting to the new standards of modern human life. Thus, it is impossible to determine the causes of poverty with absolute precision. Still, a range of empirical knowledge about humanity allows identifying three groups of causes most likely to lead people and entire societies to poverty. Thus, this paper’s central thesis is that a person’s poverty can be influenced not only by the characteristics of his behavior but also by the circumstances in which he was born. These may include political and economic factors, which often cause poverty for the individual and the whole society.

There are various theories that summarize the causes of poverty. Brady (2019) writes that all theories about the emergence of poverty can be divided into three conditional groups: structural, behavioral, and political. The behavioral factor refers to the set of qualities of an individual that impede his financial well-being. These may include various addictions, insufficient level of education, a person’s worldview, and other reasons. Structural factors include labor market conditions, demographic context, and other socio-economic circumstances. An example is the increase in poverty associated with the development of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the World Bank (2022), declining incomes, job losses and work stoppages during the pandemic have significantly reduced household incomes. Finally, political causes refer to the policies pursued by the government and its institutions, which hinder the economic well-being of the citizen and society.

Observing the behavioral causes of poverty, it is worth noting several vital factors highlighted by scholars. Brown (2018) writes that given the same circumstances, some people may become more prosperous than others, which may be due to a number of their behavioral characteristics. Various studies have tested the correlation between different measures of human character and one’s financial situation. Still, one can assume the deductive argument that greater diligence, striving for growth and development, ambition, and other personality traits can affect whether or not one will be poor. According to behavioral theory, if people become poor, then they themselves are responsible for this, since their individual shortcomings, laziness or lack of qualifications necessary for society lead to the impossibility of finding a job. Mavroudeas et al. (2019) note that the character traits of the unemployed can vary widely, from a lack of hard work or good morals to a low level of education or competitive market skills. Moreover, it is worth considering that some illnesses prevent a person from reaching their goals. Such illnesses include disabilities, congenital problems, and other factors affecting a person’s future expenses and employment.

The next group of reasons is related to the demographic characteristics of the region and the conditions of the labor market there. Fewer children are born in countries where the second demographic transition has occurred. It allows parents to concentrate all their efforts on upbringing, education, and health. In less developed countries or countries with higher fertility rates, parents have to rely on the number of their children. High infant mortality forces parents to have more children than their financial situation can afford, which is also a significant cause of poverty in the developing world.

Several political, social, historical, and economic factors prevent certain societies, and therefore most of their members, from crossing the poverty threshold. Being in a prolonged military conflict, a severe financial crisis, and insufficient valuable resources for economic development are important causes of poverty for many African and Asian countries (Wijekoon, 2021). All these factors harm the region’s economic development, creating several behavioral and structural problems. For example, higher levels of unemployment often lead to problems with alcohol addiction in society. It is also worth noting that Greve (2019) identifies certain categories of citizens who, due to demographic, social and economic reasons, find themselves in a state of poverty. These include the disabled, pensioners, people with a high incidence of disease, and those with a large number of dependents. Thus, the cause of poverty is a person’s belonging to these groups.

The political reasons also include a high level of state corruption, leading to an unfair allocation of resources. In situations where a limited number of people own most of the country’s natural reserves, resources, and finances, essential to discuss unnatural causes of regional poverty caused by the incompetent work of the state apparatus. Correct distribution of resources in the economy, which promotes competition between businesses and individuals, can lead a country to develop and reduce the number of poor people.

Thus, many causes of poverty affect individuals and society in different ways. Although the definition of poverty is constantly changing and varies from country to country, there are several universal reasons for the poverty of some and the wealth of others. These reasons are historical, political, demographic, and others, as many factors, influence a person’s financial situation. Each of these causes can be a consequence of the previous one, just as alcohol addiction can follow a wage fall or an increase in unemployment.

Brady, D. (2019). Theories of the Causes of Poverty. Annual Review of Sociology , 45 , 155-175.

Brown, U., & Long, G. (2018). Poverty and welfare. In Social Welfare (pp. 19-34). Routledge.

Greve, B. (2019). Poverty: The Basics (1 st ed.). Routledge.

Mavroudeas, S., Akar, S., & Dobreva, J. (2019). Globalization, poverty, inequality, & sustainability. IJOPEC.

The World Bank. (2022). Poverty. The World Bank. Web.

Wijekoon, R., Sabri, M. F., & Paim, L. (2021). Poverty: A literature review of the concept, measurements, causes and the way forward. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences , 11 (15), 93-111.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, July 30). Poverty: The Main Causes and Factors. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-the-main-causes-and-factors/

"Poverty: The Main Causes and Factors." IvyPanda , 30 July 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-the-main-causes-and-factors/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Poverty: The Main Causes and Factors'. 30 July.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Poverty: The Main Causes and Factors." July 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-the-main-causes-and-factors/.

1. IvyPanda . "Poverty: The Main Causes and Factors." July 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-the-main-causes-and-factors/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Poverty: The Main Causes and Factors." July 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-the-main-causes-and-factors/.

- Alcohol Addiction: Biological & Social Perspective

- Structural Violence and Its Main Forms

- Misconceptions About Addiction

- How to Overcome Poverty and Discrimination

- Poverty and Homelessness in American Society

- Income and Wealth Inequality in Canada

- Connection of Poverty and Education

- The Opportunity for All Program: Poverty Reduction

Why Poverty Persists in America

A Pulitzer Prize-winning sociologist offers a new explanation for an intractable problem.

A mother and son living in a Walmart parking lot in North Dakota in 2012. Credit... Eugene Richards

Supported by

- Share full article

By Matthew Desmond

- Published March 9, 2023 Updated April 3, 2023

In the past 50 years, scientists have mapped the entire human genome and eradicated smallpox. Here in the United States, infant-mortality rates and deaths from heart disease have fallen by roughly 70 percent, and the average American has gained almost a decade of life. Climate change was recognized as an existential threat. The internet was invented.

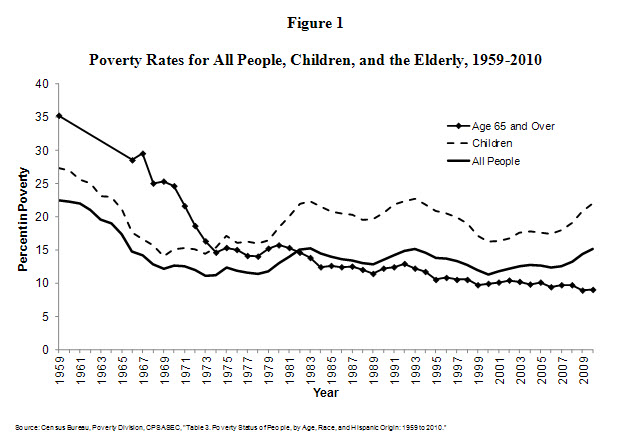

On the problem of poverty, though, there has been no real improvement — just a long stasis. As estimated by the federal government’s poverty line, 12.6 percent of the U.S. population was poor in 1970; two decades later, it was 13.5 percent; in 2010, it was 15.1 percent; and in 2019, it was 10.5 percent. To graph the share of Americans living in poverty over the past half-century amounts to drawing a line that resembles gently rolling hills. The line curves slightly up, then slightly down, then back up again over the years, staying steady through Democratic and Republican administrations, rising in recessions and falling in boom years.

What accounts for this lack of progress? It cannot be chalked up to how the poor are counted: Different measures spit out the same embarrassing result. When the government began reporting the Supplemental Poverty Measure in 2011, designed to overcome many of the flaws of the Official Poverty Measure, including not accounting for regional differences in costs of living and government benefits, the United States officially gained three million more poor people. Possible reductions in poverty from counting aid like food stamps and tax benefits were more than offset by recognizing how low-income people were burdened by rising housing and health care costs.

The American poor have access to cheap, mass-produced goods, as every American does. But that doesn’t mean they can access what matters most.

Any fair assessment of poverty must confront the breathtaking march of material progress. But the fact that standards of living have risen across the board doesn’t mean that poverty itself has fallen. Forty years ago, only the rich could afford cellphones. But cellphones have become more affordable over the past few decades, and now most Americans have one, including many poor people. This has led observers like Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill, senior fellows at the Brookings Institution, to assert that “access to certain consumer goods,” like TVs, microwave ovens and cellphones, shows that “the poor are not quite so poor after all.”

No, it doesn’t. You can’t eat a cellphone. A cellphone doesn’t grant you stable housing, affordable medical and dental care or adequate child care. In fact, as things like cellphones have become cheaper, the cost of the most necessary of life’s necessities, like health care and rent, has increased. From 2000 to 2022 in the average American city, the cost of fuel and utilities increased by 115 percent. The American poor, living as they do in the center of global capitalism, have access to cheap, mass-produced goods, as every American does. But that doesn’t mean they can access what matters most. As Michael Harrington put it 60 years ago: “It is much easier in the United States to be decently dressed than it is to be decently housed, fed or doctored.”

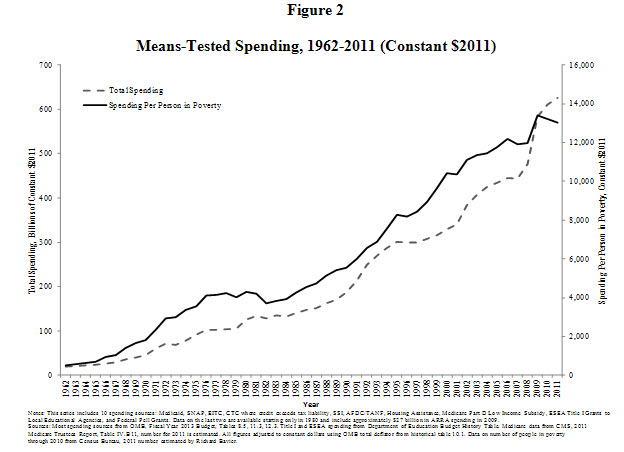

Why, then, when it comes to poverty reduction, have we had 50 years of nothing? When I first started looking into this depressing state of affairs, I assumed America’s efforts to reduce poverty had stalled because we stopped trying to solve the problem. I bought into the idea, popular among progressives, that the election of President Ronald Reagan (as well as that of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom) marked the ascendancy of market fundamentalism, or “neoliberalism,” a time when governments cut aid to the poor, lowered taxes and slashed regulations. If American poverty persisted, I thought, it was because we had reduced our spending on the poor. But I was wrong.

Reagan expanded corporate power, deeply cut taxes on the rich and rolled back spending on some antipoverty initiatives, especially in housing. But he was unable to make large-scale, long-term cuts to many of the programs that make up the American welfare state. Throughout Reagan’s eight years as president, antipoverty spending grew, and it continued to grow after he left office. Spending on the nation’s 13 largest means-tested programs — aid reserved for Americans who fall below a certain income level — went from $1,015 a person the year Reagan was elected president to $3,419 a person one year into Donald Trump’s administration, a 237 percent increase.

Most of this increase was due to health care spending, and Medicaid in particular. But even if we exclude Medicaid from the calculation, we find that federal investments in means-tested programs increased by 130 percent from 1980 to 2018, from $630 to $1,448 per person.

“Neoliberalism” is now part of the left’s lexicon, but I looked in vain to find it in the plain print of federal budgets, at least as far as aid to the poor was concerned. There is no evidence that the United States has become stingier over time. The opposite is true.

This makes the country’s stalled progress on poverty even more baffling. Decade after decade, the poverty rate has remained flat even as federal relief has surged.

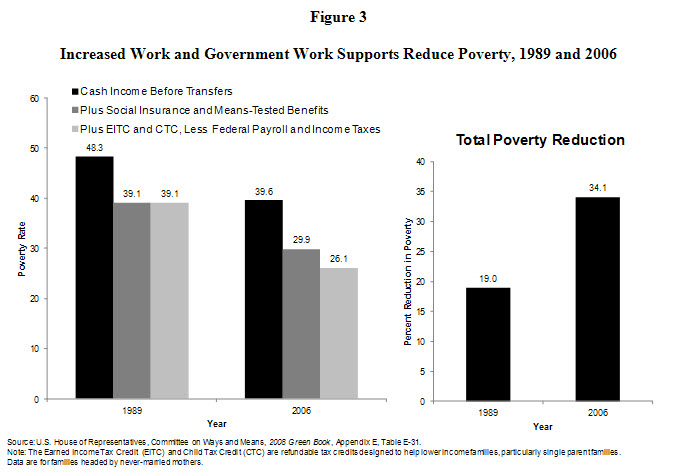

If we have more than doubled government spending on poverty and achieved so little, one reason is that the American welfare state is a leaky bucket. Take welfare, for example: When it was administered through the Aid to Families With Dependent Children program, almost all of its funds were used to provide single-parent families with cash assistance. But when President Bill Clinton reformed welfare in 1996, replacing the old model with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), he transformed the program into a block grant that gives states considerable leeway in deciding how to distribute the money. As a result, states have come up with rather creative ways to spend TANF dollars. Arizona has used welfare money to pay for abstinence-only sex education. Pennsylvania diverted TANF funds to anti-abortion crisis-pregnancy centers. Maine used the money to support a Christian summer camp. Nationwide, for every dollar budgeted for TANF in 2020, poor families directly received just 22 cents.

We’ve approached the poverty question by pointing to poor people themselves, when we should have been focusing on exploitation.

A fair amount of government aid earmarked for the poor never reaches them. But this does not fully solve the puzzle of why poverty has been so stubbornly persistent, because many of the country’s largest social-welfare programs distribute funds directly to people. Roughly 85 percent of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program budget is dedicated to funding food stamps themselves, and almost 93 percent of Medicaid dollars flow directly to beneficiaries.

There are, it would seem, deeper structural forces at play, ones that have to do with the way the American poor are routinely taken advantage of. The primary reason for our stalled progress on poverty reduction has to do with the fact that we have not confronted the unrelenting exploitation of the poor in the labor, housing and financial markets.

As a theory of poverty, “exploitation” elicits a muddled response, causing us to think of course and but, no in the same instant. The word carries a moral charge, but social scientists have a fairly coolheaded way to measure exploitation: When we are underpaid relative to the value of what we produce, we experience labor exploitation; when we are overcharged relative to the value of something we purchase, we experience consumer exploitation. For example, if a family paid $1,000 a month to rent an apartment with a market value of $20,000, that family would experience a higher level of renter exploitation than a family who paid the same amount for an apartment with a market valuation of $100,000. When we don’t own property or can’t access credit, we become dependent on people who do and can, which in turn invites exploitation, because a bad deal for you is a good deal for me.

Our vulnerability to exploitation grows as our liberty shrinks. Because labor laws often fail to protect undocumented workers in practice, more than a third are paid below minimum wage, and nearly 85 percent are not paid overtime. Many of us who are U.S. citizens, or who crossed borders through official checkpoints, would not work for these wages. We don’t have to. If they migrate here as adults, those undocumented workers choose the terms of their arrangement. But just because desperate people accept and even seek out exploitative conditions doesn’t make those conditions any less exploitative. Sometimes exploitation is simply the best bad option.

Consider how many employers now get one over on American workers. The United States offers some of the lowest wages in the industrialized world. A larger share of workers in the United States make “low pay” — earning less than two-thirds of median wages — than in any other country belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. According to the group, nearly 23 percent of American workers labor in low-paying jobs, compared with roughly 17 percent in Britain, 11 percent in Japan and 5 percent in Italy. Poverty wages have swollen the ranks of the American working poor, most of whom are 35 or older.

One popular theory for the loss of good jobs is deindustrialization, which caused the shuttering of factories and the hollowing out of communities that had sprung up around them. Such a passive word, “deindustrialization” — leaving the impression that it just happened somehow, as if the country got deindustrialization the way a forest gets infested by bark beetles. But economic forces framed as inexorable, like deindustrialization and the acceleration of global trade, are often helped along by policy decisions like the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement, which made it easier for companies to move their factories to Mexico and contributed to the loss of hundreds of thousands of American jobs. The world has changed, but it has changed for other economies as well. Yet Belgium and Canada and many other countries haven’t experienced the kind of wage stagnation and surge in income inequality that the United States has.

Those countries managed to keep their unions. We didn’t. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, nearly a third of all U.S. workers carried union cards. These were the days of the United Automobile Workers, led by Walter Reuther, once savagely beaten by Ford’s brass-knuckle boys, and of the mighty American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations that together represented around 15 million workers, more than the population of California at the time.

In their heyday, unions put up a fight. In 1970 alone, 2.4 million union members participated in work stoppages, wildcat strikes and tense standoffs with company heads. The labor movement fought for better pay and safer working conditions and supported antipoverty policies. Their efforts paid off for both unionized and nonunionized workers, as companies like Eastman Kodak were compelled to provide generous compensation and benefits to their workers to prevent them from organizing. By one estimate, the wages of nonunionized men without a college degree would be 8 percent higher today if union strength remained what it was in the late 1970s, a time when worker pay climbed, chief-executive compensation was reined in and the country experienced the most economically equitable period in modern history.

It is important to note that Old Labor was often a white man’s refuge. In the 1930s, many unions outwardly discriminated against Black workers or segregated them into Jim Crow local chapters. In the 1960s, unions like the Brotherhood of Railway and Steamship Clerks and the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America enforced segregation within their ranks. Unions harmed themselves through their self-defeating racism and were further weakened by a changing economy. But organized labor was also attacked by political adversaries. As unions flagged, business interests sensed an opportunity. Corporate lobbyists made deep inroads in both political parties, beginning a public-relations campaign that pressured policymakers to roll back worker protections.

A national litmus test arrived in 1981, when 13,000 unionized air traffic controllers left their posts after contract negotiations with the Federal Aviation Administration broke down. When the workers refused to return, Reagan fired all of them. The public’s response was muted, and corporate America learned that it could crush unions with minimal blowback. And so it went, in one industry after another.

Today almost all private-sector employees (94 percent) are without a union, though roughly half of nonunion workers say they would organize if given the chance. They rarely are. Employers have at their disposal an arsenal of tactics designed to prevent collective bargaining, from hiring union-busting firms to telling employees that they could lose their jobs if they vote yes. Those strategies are legal, but companies also make illegal moves to block unions, like disciplining workers for trying to organize or threatening to close facilities. In 2016 and 2017, the National Labor Relations Board charged 42 percent of employers with violating federal law during union campaigns. In nearly a third of cases, this involved illegally firing workers for organizing.

Corporate lobbyists told us that organized labor was a drag on the economy — that once the companies had cleared out all these fusty, lumbering unions, the economy would rev up, raising everyone’s fortunes. But that didn’t come to pass. The negative effects of unions have been wildly overstated, and there is now evidence that unions play a role in increasing company productivity, for example by reducing turnover. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics measures productivity as how efficiently companies turn inputs (like materials and labor) into outputs (like goods and services). Historically, productivity, wages and profits rise and fall in lock step. But the American economy is less productive today than it was in the post-World War II period, when unions were at peak strength. The economies of other rich countries have slowed as well, including those with more highly unionized work forces, but it is clear that diluting labor power in America did not unleash economic growth or deliver prosperity to more people. “We were promised economic dynamism in exchange for inequality,” Eric Posner and Glen Weyl write in their book “Radical Markets.” “We got the inequality, but dynamism is actually declining.”

As workers lost power, their jobs got worse. For several decades after World War II, ordinary workers’ inflation-adjusted wages (known as “real wages”) increased by 2 percent each year. But since 1979, real wages have grown by only 0.3 percent a year. Astonishingly, workers with a high school diploma made 2.7 percent less in 2017 than they would have in 1979, adjusting for inflation. Workers without a diploma made nearly 10 percent less.

Lousy, underpaid work is not an indispensable, if regrettable, byproduct of capitalism, as some business defenders claim today. (This notion would have scandalized capitalism’s earliest defenders. John Stuart Mill, arch advocate of free people and free markets, once said that if widespread scarcity was a hallmark of capitalism, he would become a communist.) But capitalism is inherently about owners trying to give as little, and workers trying to get as much, as possible. With unions largely out of the picture, corporations have chipped away at the conventional midcentury work arrangement, which involved steady employment, opportunities for advancement and raises and decent pay with some benefits.

As the sociologist Gerald Davis has put it: Our grandparents had careers. Our parents had jobs. We complete tasks. Or at least that has been the story of the American working class and working poor.

Poor Americans aren’t just exploited in the labor market. They face consumer exploitation in the housing and financial markets as well.

There is a long history of slum exploitation in America. Money made slums because slums made money. Rent has more than doubled over the past two decades, rising much faster than renters’ incomes. Median rent rose from $483 in 2000 to $1,216 in 2021. Why have rents shot up so fast? Experts tend to offer the same rote answers to this question. There’s not enough housing supply, they say, and too much demand. Landlords must charge more just to earn a decent rate of return. Must they? How do we know?

We need more housing; no one can deny that. But rents have jumped even in cities with plenty of apartments to go around. At the end of 2021, almost 19 percent of rental units in Birmingham, Ala., sat vacant, as did 12 percent of those in Syracuse, N.Y. Yet rent in those areas increased by roughly 14 percent and 8 percent, respectively, over the previous two years. National data also show that rental revenues have far outpaced property owners’ expenses in recent years, especially for multifamily properties in poor neighborhoods. Rising rents are not simply a reflection of rising operating costs. There’s another dynamic at work, one that has to do with the fact that poor people — and particularly poor Black families — don’t have much choice when it comes to where they can live. Because of that, landlords can overcharge them, and they do.

A study I published with Nathan Wilmers found that after accounting for all costs, landlords operating in poor neighborhoods typically take in profits that are double those of landlords operating in affluent communities. If down-market landlords make more, it’s because their regular expenses (especially their mortgages and property-tax bills) are considerably lower than those in upscale neighborhoods. But in many cities with average or below-average housing costs — think Buffalo, not Boston — rents in the poorest neighborhoods are not drastically lower than rents in the middle-class sections of town. From 2015 to 2019, median monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the Indianapolis metropolitan area was $991; it was $816 in neighborhoods with poverty rates above 40 percent, just around 17 percent less. Rents are lower in extremely poor neighborhoods, but not by as much as you would think.

Yet where else can poor families live? They are shut out of homeownership because banks are disinclined to issue small-dollar mortgages, and they are also shut out of public housing, which now has waiting lists that stretch on for years and even decades. Struggling families looking for a safe, affordable place to live in America usually have but one choice: to rent from private landlords and fork over at least half their income to rent and utilities. If millions of poor renters accept this state of affairs, it’s not because they can’t afford better alternatives; it’s because they often aren’t offered any.

You can read injunctions against usury in the Vedic texts of ancient India, in the sutras of Buddhism and in the Torah. Aristotle and Aquinas both rebuked it. Dante sent moneylenders to the seventh circle of hell. None of these efforts did much to stem the practice, but they do reveal that the unprincipled act of trapping the poor in a cycle of debt has existed at least as long as the written word. It might be the oldest form of exploitation after slavery. Many writers have depicted America’s poor as unseen, shadowed and forgotten people: as “other” or “invisible.” But markets have never failed to notice the poor, and this has been particularly true of the market for money itself.

The deregulation of the banking system in the 1980s heightened competition among banks. Many responded by raising fees and requiring customers to carry minimum balances. In 1977, over a third of banks offered accounts with no service charge. By the early 1990s, only 5 percent did. Big banks grew bigger as community banks shuttered, and in 2021, the largest banks in America charged customers almost $11 billion in overdraft fees. Previous research showed that just 9 percent of account holders paid 84 percent of these fees. Who were the unlucky 9 percent? Customers who carried an average balance of less than $350. The poor were made to pay for their poverty.

In 2021, the average fee for overdrawing your account was $33.58. Because banks often issue multiple charges a day, it’s not uncommon to overdraw your account by $20 and end up paying $200 for it. Banks could (and do) deny accounts to people who have a history of overextending their money, but those customers also provide a steady revenue stream for some of the most powerful financial institutions in the world.

Every year: almost $11 billion in overdraft fees, $1.6 billion in check-cashing fees and up to $8.2 billion in payday-loan fees.

According to the F.D.I.C., one in 19 U.S. households had no bank account in 2019, amounting to more than seven million families. Compared with white families, Black and Hispanic families were nearly five times as likely to lack a bank account. Where there is exclusion, there is exploitation. Unbanked Americans have created a market, and thousands of check-cashing outlets now serve that market. Check-cashing stores generally charge from 1 to 10 percent of the total, depending on the type of check. That means that a worker who is paid $10 an hour and takes a $1,000 check to a check-cashing outlet will pay $10 to $100 just to receive the money he has earned, effectively losing one to 10 hours of work. (For many, this is preferable to the less-predictable exploitation by traditional banks, with their automatic overdraft fees. It’s the devil you know.) In 2020, Americans spent $1.6 billion just to cash checks. If the poor had a costless way to access their own money, over a billion dollars would have remained in their pockets during the pandemic-induced recession.

Poverty can mean missed payments, which can ruin your credit. But just as troublesome as bad credit is having no credit score at all, which is the case for 26 million adults in the United States. Another 19 million possess a credit history too thin or outdated to be scored. Having no credit (or bad credit) can prevent you from securing an apartment, buying insurance and even landing a job, as employers are increasingly relying on credit checks during the hiring process. And when the inevitable happens — when you lose hours at work or when the car refuses to start — the payday-loan industry steps in.

For most of American history, regulators prohibited lending institutions from charging exorbitant interest on loans. Because of these limits, banks kept interest rates between 6 and 12 percent and didn’t do much business with the poor, who in a pinch took their valuables to the pawnbroker or the loan shark. But the deregulation of the banking sector in the 1980s ushered the money changers back into the temple by removing strict usury limits. Interest rates soon reached 300 percent, then 500 percent, then 700 percent. Suddenly, some people were very interested in starting businesses that lent to the poor. In recent years, 17 states have brought back strong usury limits, capping interest rates and effectively prohibiting payday lending. But the trade thrives in most places. The annual percentage rate for a two-week $300 loan can reach 460 percent in California, 516 percent in Wisconsin and 664 percent in Texas.

Roughly a third of all payday loans are now issued online, and almost half of borrowers who have taken out online loans have had lenders overdraw their bank accounts. The average borrower stays indebted for five months, paying $520 in fees to borrow $375. Keeping people indebted is, of course, the ideal outcome for the payday lender. It’s how they turn a $15 profit into a $150 one. Payday lenders do not charge high fees because lending to the poor is risky — even after multiple extensions, most borrowers pay up. Lenders extort because they can.

Every year: almost $11 billion in overdraft fees, $1.6 billion in check-cashing fees and up to $8.2 billion in payday-loan fees. That’s more than $55 million in fees collected predominantly from low-income Americans each day — not even counting the annual revenue collected by pawnshops and title loan services and rent-to-own schemes. When James Baldwin remarked in 1961 how “extremely expensive it is to be poor,” he couldn’t have imagined these receipts.

“Predatory inclusion” is what the historian Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor calls it in her book “Race for Profit,” describing the longstanding American tradition of incorporating marginalized people into housing and financial schemes through bad deals when they are denied good ones. The exclusion of poor people from traditional banking and credit systems has forced them to find alternative ways to cash checks and secure loans, which has led to a normalization of their exploitation. This is all perfectly legal, after all, and subsidized by the nation’s richest commercial banks. The fringe banking sector would not exist without lines of credit extended by the conventional one. Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase bankroll payday lenders like Advance America and Cash America. Everybody gets a cut.

Poverty isn’t simply the condition of not having enough money. It’s the condition of not having enough choice and being taken advantage of because of that. When we ignore the role that exploitation plays in trapping people in poverty, we end up designing policy that is weak at best and ineffective at worst. For example, when legislation lifts incomes at the bottom without addressing the housing crisis, those gains are often realized instead by landlords, not wholly by the families the legislation was intended to help. A 2019 study conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia found that when states raised minimum wages, families initially found it easier to pay rent. But landlords quickly responded to the wage bumps by increasing rents, which diluted the effect of the policy. This happened after the pandemic rescue packages, too: When wages began to rise in 2021 after worker shortages, rents rose as well, and soon people found themselves back where they started or worse.

Antipoverty programs work. Each year, millions of families are spared the indignities and hardships of severe deprivation because of these government investments. But our current antipoverty programs cannot abolish poverty by themselves. The Johnson administration started the War on Poverty and the Great Society in 1964. These initiatives constituted a bundle of domestic programs that included the Food Stamp Act, which made food aid permanent; the Economic Opportunity Act, which created Job Corps and Head Start; and the Social Security Amendments of 1965, which founded Medicare and Medicaid and expanded Social Security benefits. Nearly 200 pieces of legislation were signed into law in President Lyndon B. Johnson’s first five years in office, a breathtaking level of activity. And the result? Ten years after the first of these programs were rolled out in 1964, the share of Americans living in poverty was half what it was in 1960.

But the War on Poverty and the Great Society were started during a time when organized labor was strong, incomes were climbing, rents were modest and the fringe banking industry as we know it today didn’t exist. Today multiple forms of exploitation have turned antipoverty programs into something like dialysis, a treatment designed to make poverty less lethal, not to make it disappear.

This means we don’t just need deeper antipoverty investments. We need different ones, policies that refuse to partner with poverty, policies that threaten its very survival. We need to ensure that aid directed at poor people stays in their pockets, instead of being captured by companies whose low wages are subsidized by government benefits, or by landlords who raise the rents as their tenants’ wages rise, or by banks and payday-loan outlets who issue exorbitant fines and fees. Unless we confront the many forms of exploitation that poor families face, we risk increasing government spending only to experience another 50 years of sclerosis in the fight against poverty.

The best way to address labor exploitation is to empower workers. A renewed contract with American workers should make organizing easy. As things currently stand, unionizing a workplace is incredibly difficult. Under current labor law, workers who want to organize must do so one Amazon warehouse or one Starbucks location at a time. We have little chance of empowering the nation’s warehouse workers and baristas this way. This is why many new labor movements are trying to organize entire sectors. The Fight for $15 campaign, led by the Service Employees International Union, doesn’t focus on a single franchise (a specific McDonald’s store) or even a single company (McDonald’s) but brings together workers from several fast-food chains. It’s a new kind of labor power, and one that could be expanded: If enough workers in a specific economic sector — retail, hotel services, nursing — voted for the measure, the secretary of labor could establish a bargaining panel made up of representatives elected by the workers. The panel could negotiate with companies to secure the best terms for workers across the industry. This is a way to organize all Amazon warehouses and all Starbucks locations in a single go.

Sectoral bargaining, as it’s called, would affect tens of millions of Americans who have never benefited from a union of their own, just as it has improved the lives of workers in Europe and Latin America. The idea has been criticized by members of the business community, like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which has raised concerns about the inflexibility and even the constitutionality of sectoral bargaining, as well as by labor advocates, who fear that industrywide policies could nullify gains that existing unions have made or could be achieved only if workers make other sacrifices. Proponents of the idea counter that sectoral bargaining could even the playing field, not only between workers and bosses, but also between companies in the same sector that would no longer be locked into a race to the bottom, with an incentive to shortchange their work force to gain a competitive edge. Instead, the companies would be forced to compete over the quality of the goods and services they offer. Maybe we would finally reap the benefits of all that economic productivity we were promised.

We must also expand the housing options for low-income families. There isn’t a single right way to do this, but there is clearly a wrong way: the way we’re doing it now. One straightforward approach is to strengthen our commitment to the housing programs we already have. Public housing provides affordable homes to millions of Americans, but it’s drastically underfunded relative to the need. When the wealthy township of Cherry Hill, N.J., opened applications for 29 affordable apartments in 2021, 9,309 people applied. The sky-high demand should tell us something, though: that affordable housing is a life changer, and families are desperate for it.

We could also pave the way for more Americans to become homeowners, an initiative that could benefit poor, working-class and middle-class families alike — as well as scores of young people. Banks generally avoid issuing small-dollar mortgages, not because they’re riskier — these mortgages have the same delinquency rates as larger mortgages — but because they’re less profitable. Over the life of a mortgage, interest on $1 million brings in a lot more money than interest on $75,000. This is where the federal government could step in, providing extra financing to build on-ramps to first-time homeownership. In fact, it already does so in rural America through the 502 Direct Loan Program, which has moved more than two million families into their own homes. These loans, fully guaranteed and serviced by the Department of Agriculture, come with low interest rates and, for very poor families, cover the entire cost of the mortgage, nullifying the need for a down payment. Last year, the average 502 Direct Loan was for $222,300 but cost the government only $10,370 per loan, chump change for such a durable intervention. Expanding a program like this into urban communities would provide even more low- and moderate-income families with homes of their own.

We should also ensure fair access to capital. Banks should stop robbing the poor and near-poor of billions of dollars each year, immediately ending exorbitant overdraft fees. As the legal scholar Mehrsa Baradaran has pointed out, when someone overdraws an account, banks could simply freeze the transaction or could clear a check with insufficient funds, providing customers a kind of short-term loan with a low interest rate of, say, 1 percent a day.

States should rein in payday-lending institutions and insist that lenders make it clear to potential borrowers what a loan is ultimately likely to cost them. Just as fast-food restaurants must now publish calorie counts next to their burgers and shakes, payday-loan stores should publish the average overall cost of different loans. When Texas adopted disclosure rules, residents took out considerably fewer bad loans. If Texas can do this, why not California or Wisconsin? Yet to stop financial exploitation, we need to expand, not limit, low-income Americans’ access to credit. Some have suggested that the government get involved by having the U.S. Postal Service or the Federal Reserve issue small-dollar loans. Others have argued that we should revise government regulations to entice commercial banks to pitch in. Whatever our approach, solutions should offer low-income Americans more choice, a way to end their reliance on predatory lending institutions that can get away with robbery because they are the only option available.

In Tommy Orange’s novel, “There There,” a man trying to describe the problem of suicides on Native American reservations says: “Kids are jumping out the windows of burning buildings, falling to their deaths. And we think the problem is that they’re jumping.” The poverty debate has suffered from a similar kind of myopia. For the past half-century, we’ve approached the poverty question by pointing to poor people themselves — posing questions about their work ethic, say, or their welfare benefits — when we should have been focusing on the fire. The question that should serve as a looping incantation, the one we should ask every time we drive past a tent encampment, those tarped American slums smelling of asphalt and bodies, or every time we see someone asleep on the bus, slumped over in work clothes, is simply: Who benefits? Not: Why don’t you find a better job? Or: Why don’t you move? Or: Why don’t you stop taking out payday loans? But: Who is feeding off this?

Those who have amassed the most power and capital bear the most responsibility for America’s vast poverty: political elites who have utterly failed low-income Americans over the past half-century; corporate bosses who have spent and schemed to prioritize profits over families; lobbyists blocking the will of the American people with their self-serving interests; property owners who have exiled the poor from entire cities and fueled the affordable-housing crisis. Acknowledging this is both crucial and deliciously absolving; it directs our attention upward and distracts us from all the ways (many unintentional) that we — we the secure, the insured, the housed, the college-educated, the protected, the lucky — also contribute to the problem.

Corporations benefit from worker exploitation, sure, but so do consumers, who buy the cheap goods and services the working poor produce, and so do those of us directly or indirectly invested in the stock market. Landlords are not the only ones who benefit from housing exploitation; many homeowners do, too, their property values propped up by the collective effort to make housing scarce and expensive. The banking and payday-lending industries profit from the financial exploitation of the poor, but so do those of us with free checking accounts, as those accounts are subsidized by billions of dollars in overdraft fees.

Living our daily lives in ways that express solidarity with the poor could mean we pay more; anti-exploitative investing could dampen our stock portfolios. By acknowledging those costs, we acknowledge our complicity. Unwinding ourselves from our neighbors’ deprivation and refusing to live as enemies of the poor will require us to pay a price. It’s the price of our restored humanity and renewed country.

Matthew Desmond is a professor of sociology at Princeton University and a contributing writer for the magazine. His latest book, “Poverty, by America,” from which this article is adapted, is being published on March 21 by Crown.

An earlier version of this article referred incorrectly to the legal protections for undocumented workers. They are afforded rights under U.S. labor laws, though in practice those laws often fail to protect them.

An earlier version of this article implied an incorrect date for a statistic about overdraft fees. The research was conducted between 2005 and 2012, not in 2021.

How we handle corrections

Advertisement

7 Essays About Poverty: Example Essays and Prompts

Essays about poverty give valuable insight into the economic situation that we share globally. Read our guide with poverty essay examples and prompts for your paper.

In the US, the official poverty rate in 2022 was 11.5 percent, with 37.9 million people living below the poverty line. With a global pandemic, cost of living crisis, and climate change on the rise, we’ve seen poverty increase due to various factors. As many of us face adversity daily, we can look to essays about poverty from some of the world’s greatest speakers for inspiration and guidance.

There is nothing but a lack of social vision to prevent us from paying an adequate wage to every American citizen whether he be a hospital worker, laundry worker, maid or day laborer. There is nothing except shortsightedness to prevent us from guaranteeing an annual minimum—and livable—income for every American family. Martin Luther King Jr., Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

Writing a poverty essay can be challenging due to the many factors contributing to poverty and the knock-on effects of living below the poverty line . For example, homelessness among low-income individuals stems from many different causes.

It’s important to note that poverty exists beyond the US, with many developing countries living in extreme poverty without access to essentials like clean water and housing. For help with your essays, check out our round-up of the best essay checkers .

Essays About Poverty: Top Examples

1. pensioner poverty: fear of rise over decades as uk under-40s wealth falls, 2. the surprising poverty levels across the u.s., 3. why poverty persists in america, 4. post-pandemic poverty is rising in america’s suburbs.

- 5. The Basic Facts About Children in Poverty

- 6. The State of America’s Children

- 7. COVID-19: This is how many Americans now live below the poverty line

10 Poverty Essay Topics

1. the causes of poverty, 2. the negative effects of poverty, 3. how countries can reduce poverty rates, 4. the basic necessities and poverty, 5. how disabilities can lead to poverty, 6. how the cycle of poverty unfolds , 7. universal basic income and its relationship to poverty, 8. interview someone who has experience living in poverty, 9. the impact of the criminal justice system on poverty, 10. the different ways to create affordable housing.

There is growing concern about increasing pensioner poverty in the UK in the coming decades. Due to financial challenges like the cost of living crisis, rent increases, and the COVID-19 pandemic, under 40s have seen their finances shrink.

Osborne discusses the housing wealth gap in this article, where many under the 40s currently pay less in a pension due to rent prices. While this means they will have less pension available, they will also retire without owning a home, resulting in less personal wealth than previous generations. Osborne delves into the causes and gaps in wealth between generations in this in-depth essay.

“Those under-40s have already been identified as facing the biggest hit from rising mortgage rates , and last week a study by the financial advice firm Hargreaves Lansdown found that almost a third of 18- to 34-year-olds had stopped or cut back on their pension contributions in order to save money.” Hilary Osborne, The Guardian

In this 2023 essay, Jeremy Ney looks at the poverty levels across the US, stating that poverty has had the largest one-year increase in history. According to the most recent census, child poverty has more than doubled from 2021 to 2022.

Ney states that the expiration of government support and inflation has created new financial challenges for US families. With the increased cost of living and essential items like food and housing sharply increasing, more and more families have fallen below the poverty line. Throughout this essay, Ney displays statistics and data showing the wealth changes across states, ethnic groups, and households.

“Poverty in America reflects the inequality that plagues U.S. households. While certain regions have endured this pain much more than others, this new rising trend may spell ongoing challenges for even more communities.” Jeremy Ney, TIME

In this New York Times article, a Pulitzer Prize-winning sociologist explores why poverty exists in North America.

The American poor have access to cheap, mass-produced goods, as every American does. But that doesn’t mean they can access what matters most. Matthew Desmond, The New York Times

The U.S. Census Bureau recently released its annual data on poverty, revealing contrasting trends for 2022. While one set of findings indicated that the overall number of Americans living in poverty remained stable compared to the previous two years, another survey highlighted a concerning increase in child poverty. The rate of child poverty in the U.S. doubled from 2021 to 2022, a spike attributed mainly to the cessation of the expanded child tax credit following the pandemic. These varied outcomes underscore the Census Bureau’s multifaceted methods to measure poverty.

“The nation’s suburbs accounted for the majority of increases in the poor population following the onset of the pandemic” Elizabeth Kneebone and Alan Berube, Brookings

5. The Basic Facts About Children in Poverty

Nearly 11 million children are living in poverty in America. This essay explores ow the crisis reached this point—and what steps must be taken to solve it.

“In America, nearly 11 million children are poor. That’s 1 in 7 kids, who make up almost one-third of all people living in poverty in this country.” Areeba Haider, Center for American Progress

6. The State of America’s Children

This essay articles how, despite advancements, children continue to be the most impoverished demographic in the U.S., with particular subgroups — such as children of color, those under five, offspring of single mothers, and children residing in the South — facing the most severe poverty levels.

“Growing up in poverty has wide-ranging, sometimes lifelong, effects on children, putting them at a much higher risk of experiencing behavioral, social, emotional, and health challenges. Childhood poverty also plays an instrumental role in impairing a child’s ability and capacity to learn, build skills, and succeed academically.” Children’s Defense Fund

7. COVID-19: This is how many Americans now live below the poverty line

This essay explores how the economic repercussions of the coronavirus pandemic 2020 led to a surge in U.S. poverty rates, with unemployment figures reaching unprecedented heights. The writer provides data confirming that individuals at the lowest economic strata bore the brunt of these challenges, indicating that the recession might have exacerbated income disparities, further widening the chasm between the affluent and the underprivileged.

“Poverty in the U.S. increased in 2020 as the coronavirus pandemic hammered the economy and unemployment soared. Those at the bottom of the economic ladder were hit hardest, new figures confirm, suggesting that the recession may have widened the gap between the rich and the poor.” Elena Delavega, World Econmic Forum

If you’re tasked with writing an essay about poverty, consider using the below topics. They offer pointers for outlining and planning an essay about this challenging topic.

One of the most specific poverty essay topics to address involves the causes of poverty. You can craft an essay to examine the most common causes of extreme poverty. Here are a few topics you might want to include:

- Racial discrimination, particularly among African Americans, has been a common cause of poverty throughout American history. Discrimination and racism can make it hard for people to get the education they need, making it nearly impossible to get a job.

- A lack of access to adequate health care can also lead to poverty. When people do not have access to healthcare, they are more likely to get sick. This could make it hard for them to go to work while also leading to major medical bills.

- Inadequate food and water can lead to poverty as well. If people’s basic needs aren’t met, they focus on finding food and water instead of getting an education they can use to find a better job.

These are just a few of the most common causes of poverty you might want to highlight in your essay. These topics could help people see why some people are more likely to become impoverished than others. You might also be interested in these essays about poverty .

Poverty affects everyone, and the impacts of an impoverished lifestyle are very real. Furthermore, the disparities when comparing adult poverty to child poverty are also significant. This opens the doors to multiple possible essay topics. Here are a few points to include:

- When children live in poverty, their development is stunted. For example, they might not be able to get to school on time due to a lack of transportation, making it hard for them to keep up with their peers. Child poverty also leads to malnutrition, which can stunt their development.

- Poverty can impact familial relationships as well. For example, members of the same family could fight for limited resources, making it hard for family members to bond. In addition, malnutrition can stunt the growth of children.

- As a side effect of poverty, people have difficulty finding a safe place to live. This creates a challenging environment for everyone involved, and it is even harder for children to grow and develop.

- When poverty leads to homelessness, it is hard for someone to get a job. They don’t have an address to use for physical communication, which leads to employment concerns.

These are just a few of the many side effects of poverty. Of course, these impacts are felt by people across the board, but it is not unusual for children to feel the effects of poverty that much more. You might also be interested in these essays about unemployment .

Different countries take different approaches to reduce the number of people living in poverty

The issue of poverty is a major human rights concern, and many countries explore poverty reduction strategies to improve people’s quality of life. You might want to examine different strategies that different countries are taking while also suggesting how some countries can do more. A few ways to write this essay include:

- Explore the poverty level in America, comparing it to the poverty level of a European country. Then, explore why different countries take different strategies.

- Compare the minimum wage in one state, such as New York, to the minimum wage in another state, such as Alabama. Why is it higher in one state? What does raising the minimum wage do to the cost of living?

- Highlight a few advocacy groups and nonprofit organizations actively lobbying their governments to do more for low-income families. Then, talk about why some efforts are more successful than others.

Different countries take different approaches to reduce the number of people living in poverty. Poverty within each country is such a broad topic that you could write a different essay on how poverty could be decreased within the country. For more, check out our list of simple essays topics for intermediate writers .

You could also write an essay on the necessities people need to survive. You could take a look at information published by the United Nations , which focuses on getting people out of the cycle of poverty across the globe. The social problem of poverty can be addressed by giving people the necessities they need to survive, particularly in rural areas. Here are some of the areas you might want to include:

- Affordable housing

- Fresh, healthy food and clean water

- Access to an affordable education

- Access to affordable healthcare

Giving everyone these necessities could significantly improve their well-being and get people out of absolute poverty. You might even want to talk about whether these necessities vary depending on where someone is living.

There are a lot of medical and social issues that contribute to poverty, and you could write about how disabilities contribute to poverty. This is one of the most important essay topics because people could be disabled through no fault of their own. Some of the issues you might want to address in this essay include:

- Talk about the road someone faces if they become disabled while serving overseas. What is it like for people to apply for benefits through the Veterans’ Administration?

- Discuss what happens if someone becomes disabled while at work. What is it like for someone to pursue disability benefits if they are hurt doing a blue-collar job instead of a desk job?

- Research and discuss the experiences of disabled people and how their disability impacts their financial situation.

People who are disabled need to have money to survive for many reasons, such as the inability to work, limitations at home, and medical expenses. A lack of money, in this situation, can lead to a dangerous cycle that can make it hard for someone to be financially stable and live a comfortable lifestyle.

Many people talk about the cycle of poverty, yet many aren’t entirely sure what this means or what it entails. A few key points you should address in this essay include:

- When someone is born into poverty, income inequality can make it hard to get an education.

- A lack of education makes it hard for someone to get into a good school, which gives them the foundation they need to compete for a good job.

- A lack of money can make it hard for someone to afford college, even if they get into a good school.

- Without attending a good college, it can be hard for someone to get a good job. This makes it hard for someone to support themselves or their families.

- Without a good paycheck, it is nearly impossible for someone to keep their children out of poverty, limiting upward mobility into the middle class.

The problem of poverty is a positive feedback loop. It can be nearly impossible for those who live this every day to escape. Therefore, you might want to explore a few initiatives that could break the cycle of world poverty and explore other measures that could break this feedback loop.

Many business people and politicians have floated the idea of a universal basic income to give people the basic resources they need to survive. While this hasn’t gotten a lot of serious traction, you could write an essay to shed light on this idea. A few points to hit on include:

- What does a universal basic income mean, and how is it distributed?

- Some people are concerned about the impact this would have on taxes. How would this be paid for?

- What is the minimum amount of money someone would need to stay out of poverty? Is it different in different areas?

- What are a few of the biggest reasons major world governments haven’t passed this?

This is one of the best essay examples because it gives you a lot of room to be creative. However, there hasn’t been a concrete structure for implementing this plan, so you might want to afford one.

Another interesting topic you might want to explore is interviewing someone living in poverty or who has been impoverished. While you can talk about statistics all day, they won’t be as powerful as interviewing someone who has lived that life. A few questions you might want to ask during your interview include:

- What was it like growing up?

- How has living in poverty made it hard for you to get a job?

- What do you feel people misunderstand about those who live in poverty?

- When you need to find a meal, do you have a place you go to? Or is it somewhere different every day?

- What do you think is the main contributor to people living in poverty?

Remember that you can also craft different questions depending on your responses. You might want to let the interviewee read the essay when you are done to ensure all the information is accurate and correct.

The criminal justice system and poverty tend to go hand in hand. People with criminal records are more likely to be impoverished for several reasons. You might want to write an essay that hits on some of these points:

- Discuss the discriminatory practices of the criminal justice system both as they relate to socioeconomic status and as they relate to race.

- Explore just how hard it is for someone to get a job if they have a criminal record. Discuss how this might contribute to a life of poverty.

- Dive into how this creates a positive feedback loop. For example, when someone cannot get a job due to a criminal record, they might have to steal to survive, which worsens the issue.

- Review what the criminal justice system might be like for someone with resources when compared to someone who cannot afford to hire expert witnesses or pay for a good attorney.

You might want to include a few examples of disparate sentences for people in different socioeconomic situations to back up your points.

Affordable housing can make a major difference when someone is trying to escape poverty

Many poverty-related problems could be reduced if people had access to affordable housing. While the cost of housing has increased dramatically in the United States , some initiatives exist to create affordable housing. Here are a few points to include:

- Talk about public programs that offer affordable housing to people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

- Discuss private programs, such as Habitat for Humanity , doing similar things.

- Review the positive impacts that stable housing has on both adults and children.

- Dive into other measures local and federal governments could take to provide more affordable housing for people.

There are a lot of political and social angles to address with this essay, so you might want to consider spreading this out across multiple papers. Affordable housing can make a major difference when trying to escape poverty. If you want to learn more, check out our essay writing tips !

Meet Rachael, the editor at Become a Writer Today. With years of experience in the field, she is passionate about language and dedicated to producing high-quality content that engages and informs readers. When she's not editing or writing, you can find her exploring the great outdoors, finding inspiration for her next project.

View all posts

10 Common Root Causes of Poverty

Poverty is a global problem. According to the World Bank in 2015 , over 700 million people were living on less than $1.90 a day. While that represents a milestone (in 1990, it was over one billion ) that’s still way too many people. That number also includes extreme poverty that is defined by the UN as “a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information. It depends not only on income but also on access to services.”

What causes poverty in the first place? Here are ten root causes:

#1. Lack of good jobs/job growth

This is the first reason a lot of people think about. When you don’t have a good job, you aren’t getting a good income. In many countries, traditional jobs like farming are disappearing. The Democratic Republic of Congo is a good example, where most of the population live in rural areas stripped of natural resources from years of colonialism. Half of the DRC live below the poverty line. Even in nations like the United States where many people do have jobs, those jobs aren’t paying enough. According to the Economic Policy Institute , large groups of workers with full-time, year-round employment are still below federal poverty guidelines.

#2: Lack of good education

The second root cause of poverty is a lack of education. Poverty is a cycle and without education, people aren’t able to better their situations. According to UNESCO , over 170 million people could be free of extreme poverty if they only had basic reading skills. However, in many areas of the world, people aren’t getting educated. The reasons vary. Often times, families need kids to work, there aren’t schools close by, or girls aren’t being educated because of sexism and discrimination.

#3: Warfare/conflict

Conflict has a huge impact on poverty. In times of war, everything stops. Productivity suffers as well as a country’s GDP. It’s very difficult to get things going again as foreign businesses and countries won’t want to invest. For families and individuals, war and conflict can make it impossible to stay in one place. It’s also very common for women to become the primary breadwinners, and they deal with many barriers like sexual violence and discrimination.

#4: Weather/climate change

According to the World Bank , climate change has the power to impoverish 100 million people in the next decade or so. We know climate change causes drought, floods, and severe storms, and that can take down successful countries while pulling poor ones down even further. Recovering is extremely difficult, as well, especially for agricultural communities where they barely have enough to feed themselves, let alone prepare for the next harvest year.

#5: Social injustice

Whether it’s gender discrimination, racism, or other forms of social injustice, poverty follows. People who are victims of social injustice struggle with getting a good education, the right job opportunities, and access to resources that can lift them out of poverty. The United Nations Social Policy and Development Division identifies “inequalities in income distribution and access to productive resources, basic social services, opportunities” and more as a cause for poverty. Groups like women, religious minorities, and racial minorities are the most vulnerable.

#6: Lack of food and water

Without access to basic essentials like food and water, it’s impossible to get out of poverty’s cycle. Everything a person does will be about getting food and water. They can’t save any money because it all goes towards their daily needs. When there isn’t enough sustenance, they won’t have the energy to work. They are also way more likely to get sick, which makes their financial situation even worse.

#7: Lack of infrastructure

Infrastructure includes roads, bridges, the internet, public transport, and more. When a community or families are isolated, they have to spend a lot of money, time, and energy getting to places. Without good roads, traveling takes forever. Without public transport, it may be next to impossible to get a good job or even to the store. Infrastructure connects people to the services and resources they need to better their financial and life situation, and without it, things don’t get better.

#8: Lack of government support

To combat many of the issues we’ve described, the government needs to be involved. However, many governments are either unable or unwilling to serve the poor. This might mean failing to provide (or cutting) social welfare programs, redirecting funds away from those who need it, failing to build good infrastructure, or actively persecuting the population. If a government fails to meet the needs of the poor, the poor will most likely stay that way.

#9: Lack of good healthcare

People who are poor are more likely to suffer from bad health, and those with bad health are more likely to be poor. This is because healthcare is often too expensive or inaccessible to those who need it. Without money for medicine and treatment, the poor have to make really tough decisions, and usually essentials like food take priority. People who are sick get sicker, and then they can’t work, which makes the situation even more dire. If people do seek treatment, the cost often ruins their finances. It’s a vicious cycle.

#10: High costs

The last root of poverty is simple: stuff costs too much. Even the basics can be too expensive. According to stats from the World Food Programme, the poorest households in the world are spending 60-80% of their incomes on food. Food prices are also very unpredictable in certain areas, so when they rise, the poor have to keep cutting out other essentials. Housing is another essential that is rising. Global house markets have been climbing, according to the International Monetary Fund. Income growth, however, has not.

You may also like

16 Inspiring Civil Rights Leaders You Should Know

15 Trusted Charities Fighting for Housing Rights

15 Examples of Gender Inequality in Everyday Life

11 Approaches to Alleviate World Hunger

15 Facts About Malala Yousafzai

12 Ways Poverty Affects Society

15 Great Charities to Donate to in 2024

15 Quotes Exposing Injustice in Society

14 Trusted Charities Helping Civilians in Palestine

The Great Migration: History, Causes and Facts

Social Change 101: Meaning, Examples, Learning Opportunities

Rosa Parks: Biography, Quotes, Impact

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

The World Bank Group is committed to fighting poverty in all its dimensions. We use the latest data, evidence and analysis to help countries develop policies to improve people's lives, with a focus on the poorest and most vulnerable.

Around 700 million people live on less than $2.15 per day, the extreme poverty line. Extreme poverty remains concentrated in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, fragile and conflict-affected areas, and rural areas.

After decades of progress, the pace of global poverty reduction began to slow by 2015, in tandem with subdued economic growth. The Sustainable Development Goal of ending extreme poverty by 2030 remains out of reach.

Global poverty reduction was dealt a severe blow by the COVID-19 pandemic and a series of major shocks during 2020-22, causing three years of lost progress. Low-income countries were most impacted and have yet to recover. In 2022, a total of 712 million people globally were living in extreme poverty, an increase of 23 million people compared to 2019.

We cannot reduce poverty and inequality without also addressing intertwined global challenges, including slow economic growth, fragility and conflict, and climate change.

Climate change is hindering poverty reduction and is a major threat going forward. The lives and livelihoods of poor people are the most vulnerable to climate-related risks.

Millions of households are pushed into, or trapped in, poverty by natural disasters every year. Higher temperatures are already reducing productivity in Africa and Latin America, and will further depress economic growth, especially in the world’s poorest regions.

Eradicating poverty requires tackling its many dimensions. Countries cannot adequately address poverty without also improving people’s well-being in a comprehensive way, including through more equitable access to health, education, and basic infrastructure and services, including digital.

Policymakers must intensify efforts to grow their economies in a way that creates high quality jobs and employment, while protecting the most vulnerable.

Jobs and employment are the surest way to reduce poverty and inequality. Impact is further multiplied in communities and across generations by empowering women and girls, and young people.

Last Updated: Apr 02, 2024

Closing the gaps between policy aspiration and attainment

Too often, there is a wide gap between policies as articulated and their attainment in practice—between what citizens rightfully expect, and what they experience daily. Policy aspirations can be laudable, but there is likely to be considerable variation in the extent to which they can be realized, and in which groups benefit from them. For example, at the local level, those who have the least influence in a community might not be able to access basic services. It is critical to forge implementation strategies that can rapidly and flexibly respond to close the gaps.

Enhancing learning, improving data

From information gathered in household surveys to pixels captured by satellite images, data can inform policies and spur economic activity, serving as a powerful weapon in the fight against poverty. More data is available today than ever before, yet its value is largely untapped. Data is also a double-edged sword, requiring a social contract that builds trust by protecting people against misuse and harm, and works toward equal access and representation.

Investing in preparedness and prevention

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that years of progress in reducing poverty can quickly disappear when a crisis strikes. Prevention measures often have low political payoff, with little credit given for disasters averted. Over time, populations with no lived experience of calamity can become complacent, presuming that such risks have been eliminated or can readily be addressed if they happen. COVID-19, together with climate change and enduring conflicts, reminds us of the importance of investing in preparedness and prevention measures comprehensively and proactively.

Expanding cooperation and coordination

Contributing to and maintaining public goods require extensive cooperation and coordination. This is crucial for promoting widespread learning and improving the data-driven foundations of policymaking. It is also important for forming a sense of shared solidarity during crises and ensuring that the difficult policy choices by officials are both trusted and trustworthy.

Overall, with more than 60 percent of the world’s extreme poor living in middle-income countries, we cannot focus solely on low-income countries if we want to end extreme poverty. We need to focus on the poorest people, regardless of where they live, and work with countries at all income levels to invest in their well-being and their future.

The goal to end extreme poverty works hand in hand with the World Bank Group’s goal to promote shared prosperity. Boosting shared prosperity broadly translates into improving the welfare of the least well-off in each country and includes a strong emphasis on tackling persistent inequalities that keep people in poverty from generation to generation.

Our work at the World Bank Group is based on strong country-led programs to improve living conditions—to drive growth, raise median incomes, create jobs, fully incorporate women and young people into economies, address environmental and climate challenges, and support stronger, more stable economies for everyone.

We continue to work closely with countries to help them find the best ways to improve the lives of their least advantaged citizens.

Last Updated: Oct 17, 2023

How the Pandemic Drove Increases in Poverty | Poverty & Shared Prosperity 2022

Around the bank group.

Find out what the World Bank Group's branches are doing to reduce poverty.

STAY CONNECTED

COVID-19 Dealt a Historic Blow to Poverty Reduction

The 2022 Poverty and Prosperity Report provides the first comprehensive analysis of the pandemic’s toll on poverty in developing countries and of the role of fiscal policy in protecting vulnerable groups.

Umbrella Facility for Poverty and Equity

The Umbrella Facility for Poverty and Equity (UFPE) is the first global trust fund to support the cross-cutting poverty and equity agenda.

IDA: Our Fund for the Poorest

The International Development Association (IDA) aims to reduce poverty by providing funding for programs that boost economic growth.

As the World Bank’s behavioral sciences team within the Poverty and Equity Global Practice, eMBeD uses behavioral sciences to fight global poverty and reduce inequality.

High-Frequency Monitoring Systems to Track the Impacts of COVID-19

The World Bank and partners are monitoring the crisis and the socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 through a series of high-frequency phone surveys.

An Adjustment to Global Poverty Lines

The World Bank uses purchasing power parities (PPPs) to estimate global poverty. With the release of 2017 PPPs, we’ll start using in Fall 2022 new poverty lines to determine the share of the world population in poverty.

Systematic Country Diagnostics

The SCD looks at issues in countries and seeks to identify barriers and opportunities for sustainable poverty reduction.

Poverty Podcast

Join us and poverty specialists as we explore the latest data and research on poverty reduction, shared prosperity, and equity around the globe in this new World Bank Group podcast series.

Correcting Course to Accelerate Poverty Reduction

Mari Pangestu, World Bank Managing Director of Development Policy and Partnerships, speaks about how we must respond to current challenges in ways that do not further impoverish the poor today and focus on creating ...

Stepping Up the Fight Against Extreme Poverty

To avert the risk of more backsliding, policymakers must put everything they can into the effort to end extreme poverty.

Additional Resources