Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

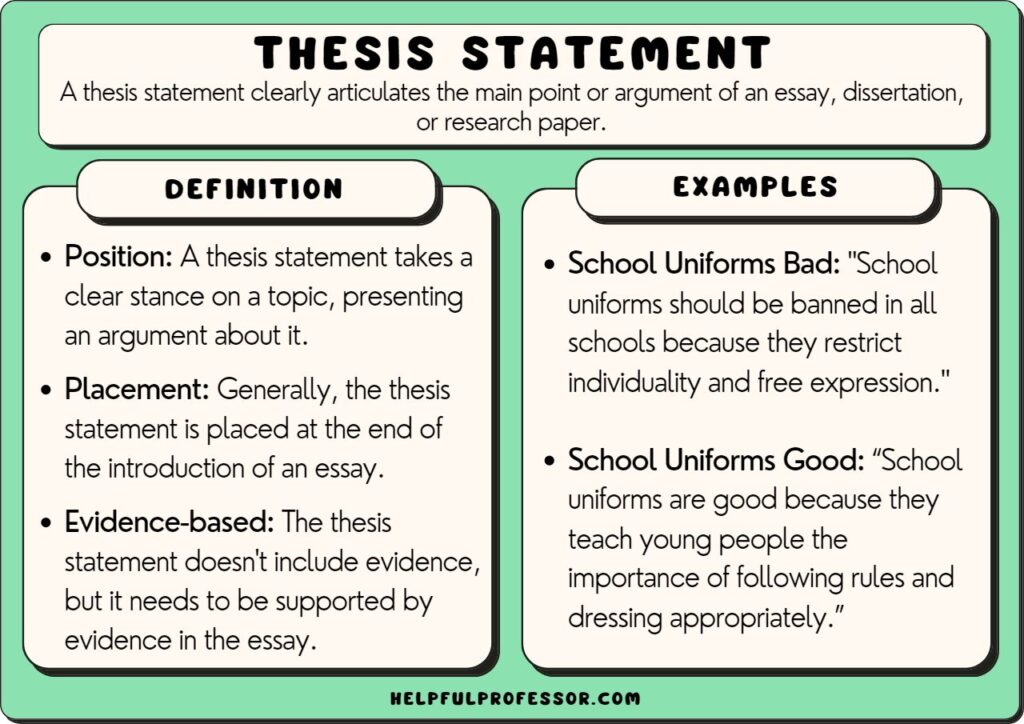

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

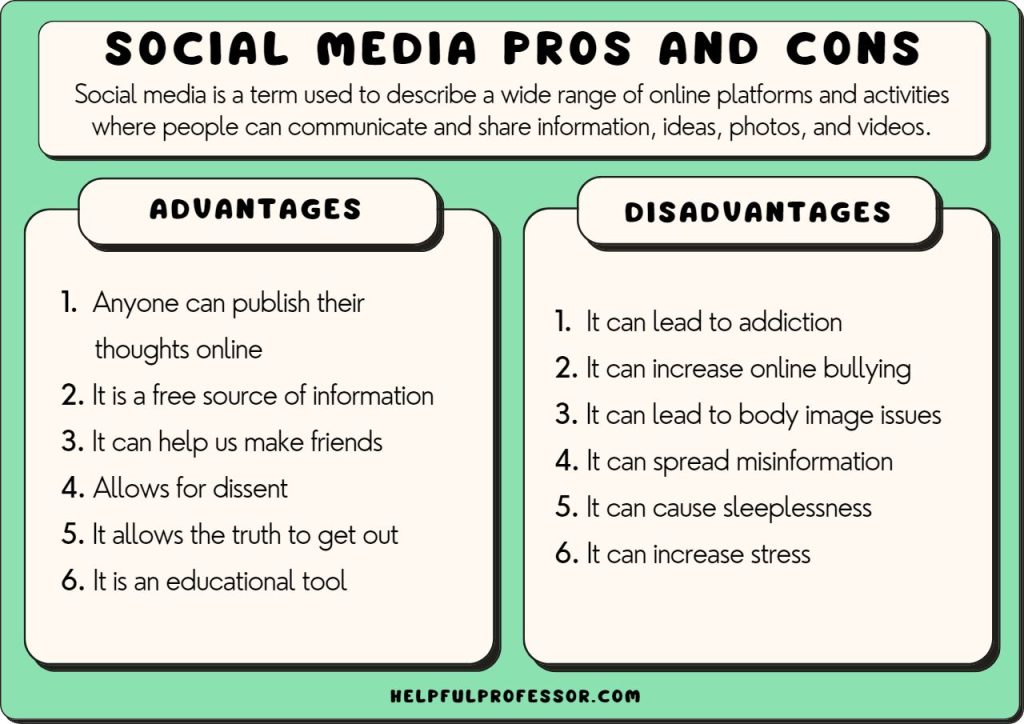

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Mind/Brain Identity Theory

The identity theory of mind holds that states and processes of the mind are identical to states and processes of the brain. Strictly speaking, it need not hold that the mind is identical to the brain. Idiomatically we do use ‘She has a good mind’ and ‘She has a good brain’ interchangeably but we would hardly say ‘Her mind weighs fifty ounces’. Here I take identifying mind and brain as being a matter of identifying processes and perhaps states of the mind and brain. Consider an experience of pain, or of seeing something, or of having a mental image. The identity theory of mind is to the effect that these experiences just are brain processes, not merely correlated with brain processes.

Some philosophers hold that though experiences are brain processes they nevertheless have fundamentally non-physical, psychical, properties, sometimes called ‘qualia’. Here I shall take the identity theory as denying the existence of such irreducible non-physical properties. Some identity theorists give a behaviouristic analysis of mental states , such as beliefs and desires, but others, sometimes called ‘central state materialists’, say that mental states are actual brain states. Identity theorists often describe themselves as ‘materialists’ but ‘physicalists’ may be a better word. That is, one might be a materialist about mind but nevertheless hold that there are entities referred to in physics that are not happily described as ‘material’.

In taking the identity theory (in its various forms) as a species of physicalism, I should say that this is an ontological, not a translational physicalism. It would be absurd to try to translate sentences containing the word ‘brain’ or the word ‘sensation’ into sentences about electrons, protons and so on. Nor can we so translate sentences containing the word ‘tree’. After all ‘tree’ is largely learned ostensively, and is not even part of botanical classification. If we were small enough a dandelion might count as a tree. Nevertheless a physicalist could say that trees are complicated physical mechanisms. The physicalist will deny strong emergence in the sense of some philosophers, such as Samuel Alexander and possibly C.D. Broad. The latter remarked (Broad 1937) that as far as was known at that time the properties of common salt cannot be deduced from the properties of sodium in isolation and of chlorine in isolation. (He put it too epistemologically: chaos theory shows that even in a deterministic theory physical consequences can outrun predictability.) Of course the physicalist will not deny the harmless sense of "emergence" in which an apparatus is not just a jumble of its parts (Smart 1981).

1. Historical Antecedents

2. the nature of the identity theory, 3. phenomenal properties and topic-neutral analyses, 4. causal role theories, 5. functionalism and identity theory, 6. type and token identity theories, 7. consciousness, 8. later objections to the identity theory, other internet resources, related entries.

The identity theory as I understand it here goes back to U.T. Place and Herbert Feigl in the 1950s. Historically philosophers and scientists, for example Leucippus, Hobbes, La Mettrie, and d'Holbach, as well as Karl Vogt who, following Pierre-Jean-Georges Cabanis, made the preposterous remark (perhaps not meant to be taken too seriously) that the brain secretes thought as the liver secretes bile, have embraced materialism. However, here I shall date interest in the identity theory from the pioneering papers ‘Is Consciousness a Brain Process?’ by U.T. Place (Place 1956) and H. Feigl ‘The "Mental" and the "Physical"’ (Feigl 1958). Nevertheless mention should be made of suggestions by Rudolf Carnap (1932, p. 127), H. Reichenbach (1938) and M. Schlick (1935). Reichenbach said that mental events can be identified by the corresponding stimuli and responses much as the (possibly unknown) internal state of a photo-electric cell can be identified by the stimulus (light falling on it) and response (electric current flowing) from it. In both cases the internal states can be physical states. However Carnap did regard the identity as a linguistic recommendation rather than as asserting a question of fact. See his ‘Herbert Feigl on Physicalism’ in Schilpp (1963), especially p. 886. The psychologist E.G. Boring (1933) may well have been the first to use the term ‘identity theory’. See Place (1990).

Place's very original and pioneering paper was written after discussions at the University of Adelaide with J.J.C. Smart and C.B. Martin. For recollections of Martin's contributions to the discussion see Place (1989) ‘Low Claim Assertions’ in Heil (1989). Smart at the time argued for a behaviourist position in which mental events were elucidated purely in terms of hypothetical propositions about behaviour, as well as first person reports of experiences which Gilbert Ryle regarded as ‘avowals’. Avowals were thought of as mere pieces of behaviour, as if saying that one had a pain was just doing a sophisticated sort of wince. Smart saw Ryle's theory as friendly to physicalism though that was not part of Ryle's motivation. Smart hoped that the hypotheticals would ultimately be explained by neuroscience and cybernetics. Being unable to refute Place, and recognizing the unsatisfactoriness of Ryle's treatment of inner experience, to some extent recognized by Ryle himself (Ryle 1949, p. 240), Smart soon became converted to Place's view (Smart 1959). In this he was also encouraged and influenced by Feigl's ‘"The Mental" and the "Physical" ’ (Feigl 1958, 1967). Feigl's wide ranging contribution covered many problems, including those connected with intentionality, and he introduced the useful term ‘nomological danglers’ for the dualists' supposed mental-physical correlations. They would dangle from the nomological net of physical science and should strike one as implausible excrescences on the fair face of science. Feigl (1967) contains a valuable ‘Postscript’.

Place spoke of constitution rather than of identity. One of his examples is ‘This table is an old packing case’. Another is ‘lightning is an electric discharge’. Indeed this latter was foreshadowed by Place in his earlier paper ‘The Concept of Heed’ (Place 1954), in which he took issue with Ryle's behaviourism as it applied to concepts of consciousness, sensation and imagery. Place remarked (p. 255)

The logical objections which might be raised to the statement ‘consciousness is a process in the brain’ are no greater than the logical objections which might be raised to the statement ‘lightning is a motion of electric charges’.

It should be noticed that Place was using the word ‘logical’ in the way that it was used at Oxford at the time, not in the way that it is normally used now. One objection was that ‘sensation’ does not mean the same as ‘brain process’. Place's reply was to point out that ‘this table’ does not mean the same as ‘this old packing case’ and ‘lightning’ does not mean the same as ‘motion of electric charges’. We find out whether this is a table in a different way from the way in which we find out that it is an old packing case. We find out whether a thing is lightning by looking and that it is a motion of electric charges by theory and experiment. This does not prevent the table being identical to the old packing case and the perceived lightning being nothing other than an electric discharge. Feigl and Smart put the matter more in terms of the distinction between meaning and reference. ‘Sensation’ and ‘brain process’ may differ in meaning and yet have the same reference. ‘Very bright planet seen in the morning’ and ‘very bright planet seen in the evening’ both refer to the same entity Venus. (Of course these expressions could be construed as referring to different things, different sequences of temporal stages of Venus, but not necessarily or most naturally so.)

There did seem to be a tendency among philosophers to have thought that identity statements needed to be necessary and a priori truths. However identity theorists have treated ‘sensations are brain processes’ as contingent. We had to find out that the identity holds. Aristotle, after all, thought that the brain was for cooling the blood. Descartes thought that consciousness is immaterial.

It was sometimes objected that sensation statements are incorrigible whereas statements about brains are corrigible. The inference was made that there must be something different about sensations. Ryle and in effect Wittgenstein toyed with the attractive but quite implausible notion that ostensible reports of immediate experience are not really reports but are ‘avowals’, as if my report that I have toothache is just a sophisticated sort of wince. Place, influenced by Martin, was able to explain the relative incorrigibility of sensation statements by their low claims: ‘I see a bent oar’ makes a bigger claim than ‘It looks to me that there is a bent oar’. Nevertheless my sensation and my putative awareness of the sensation are distinct existences and so, by Hume's principle, it must be possible for one to occur without the other. One should deny anything other than a relative incorrigibility (Place 1989).

As remarked above, Place preferred to express the theory by the notion of constitution, whereas Smart preferred to make prominent the notion of identity as it occurs in the axioms of identity in logic. So Smart had to say that if sensation X is identical to brain process Y then if Y is between my ears and is straight or circular (absurdly to oversimplify) then the sensation X is between my ears and is straight or circular. Of course it is not presented to us as such in experience. Perhaps only the neuroscientist could know that it is straight or circular. The professor of anatomy might be identical with the dean of the medical school. A visitor might know that the professor hiccups in lectures but not know that the dean hiccups in lectures.

Someone might object that the dean of the medical school does not qua dean hiccup in lectures. Qua dean he goes to meetings with the vice-chancellor. This is not to the point but there is a point behind it. This is that the property of being the professor of anatomy is not identical with the property of being the dean of the medical school. The question might be asked, that even if sensations are identical with brain processes, are there not introspected non-physical properties of sensations that are not identical with properties of brain processes? How would a physicalist identity theorist deal with this? The answer (Smart 1959) is that the properties of experiences are ‘topic neutral’. Smart adapted the words ‘topic-neutral’ from Ryle, who used them to characterise words such as ‘if, ‘or’, ‘and’, ‘not’, ‘because’. If you overheard only these words in a conversation you would not be able to tell whether the conversation was one of mathematics, physics, geology, history, theology, or any other subject. Smart used the words ‘topic neutral’ in the narrower sense of being neutral between physicalism and dualism. For example ‘going on’, ‘occurring’, ‘intermittent’, ‘waxing’, ‘waning’ are topic neutral. So is ‘me’ in so far as it refers to the utterer of the sentence in question. Thus to say that a sensation is caused by lightning or the presence of a cabbage before my eyes leaves it open as to whether the sensation is non-physical as the dualist believes or is physical as the materialist believes. This sentence also is neutral as to whether the properties of the sensation are physical or whether some of them are irreducibly psychical. To see how this idea can be applied to the present purpose let us consider the following example.

Suppose that I have a yellow, green and purple striped mental image. We may also introduce the philosophical term ‘sense datum’ to cover the case of seeing or seeming to see something yellow, green and purple: we say that we have a yellow, green and purple sense datum. That is I would see or seem to see, for example, a flag or an array of lamps which is green, yellow and purple striped. Suppose also, as seems plausible, that there is nothing yellow, green and purple striped in the brain. Thus it is important for identity theorists to say (as indeed they have done) that sense data and images are not part of the furniture of the world. ‘I have a green sense datum’ is really just a way of saying that I see or seem to see something that really is green. This move should not be seen as merely an ad hoc device, since Ryle and J.L. Austin, in effect Wittgenstein, and others had provided arguments, as when Ryle argued that mental images were not a sort of ghostly picture postcard. Place characterised the fallacy of thinking that when we perceive something green we are perceiving something green in the mind as ‘the phenomenological fallacy’. He characterizes this fallacy (Place 1956):

the mistake of supposing that when the subject describes his experience, when he describes how things look, sound, smell, taste, or feel to him, he is describing the literal properties of objects and events on a peculiar sort of internal cinema or television screen, usually referred to in the modern psychological literature as the ‘phenomenal field’.

Of course, as Smart recognised, this leaves the identity theory dependent on a physicalist account of colour . His early account of colour (1961) was too behaviourist, and could not deal, for example, with the reversed spectrum problem, but he later gave a realist and objectivist account (Smart 1975). Armstrong had been realist about colour but Smart worried that if so colour would be a very idiosyncratic and disjunctive concept, of no cosmic importance, of no interest to extraterrestrials (for instance) who had different visual systems. Prompted by Lewis in conversation Smart came to realize that this was no objection to colours being objective properties.

One first gives the notion of a normal human percipient with respect to colour for which there are objective tests in terms of ability to make discriminations with respect to colour. This can be done without circularity. Thus ‘discriminate with respect to colour’ is a more primitive notion than is that of colour. (Compare the way that in set theory ‘equinumerous’ is antecedent to ‘number’.) Then Smart elucidated the notion of colour in terms of the discriminations with respect to colour of normal human percipients in normal conditions (say cloudy Scottish daylight). This account of colour may be disjunctive and idiosyncratic. (Maxwell's equations might be of interest to Alpha Centaurians but hardly our colour concepts.) Anthropocentric and disjunctive they may be, but objective none the less. David R. Hilbert (1987) identifies colours with reflectances, thus reducing the idiosyncrasy and disjunctiveness. A few epicycles are easily added to deal with radiated light, the colours of rainbows or the sun at sunset and the colours due to diffraction from feathers. John Locke was on the right track in making the secondary qualities objective as powers in the object, but erred in making these powers to be powers to produce ideas in the mind rather than to make behavioural discriminations. (Also Smart would say that if powers are dispositions we should treat the secondary qualities as the categorical bases of these powers, e.g. in the case of colours properties of the surfaces of objects.) Locke's view suggested that the ideas have mysterious qualia observed on the screen of an internal mental theatre. However to do Locke justice he does not talk in effect of ‘red ideas’ but of ‘ideas of red’. Philosophers who elucidate ‘is red’ in terms of ‘looks red’ have the matter the wrong way round (Smart 1995).

Let us return to the issue of us having a yellow, purple and green striped sense datum or mental image and yet there being no yellow, purple and green striped thing in the brain. The identity theorist (Smart 1959) can say that sense data and images are not real things in the world: they are like the average plumber. Sentences ostensibly about the average plumber can be translated into, or elucidated in terms of, sentences about plumbers. So also there is having a green sense datum or image but not sense data or images, and the having of a green sense datum or image is not itself green. So it can, so far as this goes, easily be a brain process which is not green either.

Thus Place (1956, p. 49):

When we describe the after-image as green... we are saying that we are having the sort of experience which we normally have when, and which we have learned to described as, looking at a green patch of light.

and Smart (1959) says:

When a person says ‘I see a yellowish-orange after-image’ he is saying something like this: " There is something going on which is like what is going on when I have my eyes open, am awake, and there is an orange illuminated in good light in front of me".

Quoting these passages, David Chalmers (1996, p. 360) objects that if ‘something is going on’ is construed broadly enough it is inadequate, and if it is construed narrowly enough to cover only experiential states (or processes) it is not sufficient for the conclusion. Smart would counter this by stressing the word ‘typically’. Of course a lot of things go on in me when I have a yellow after image (for example my heart is pumping blood through my brain). However they do not typically go on then: they go on at other times too. Against Place Chalmers says that the word ‘experience’ is unanalysed and so Place's analysis is insufficient towards establishing an identity between sensations and brain processes. As against Smart he says that leaving the word ‘experience’ out of the analysis renders it inadequate. That is, he does not accept the ‘topic-neutral’ analysis. Smart hopes, and Chalmers denies, that the account in terms of ‘typically of’ saves the topic-neutral analysis. In defence of Place one might perhaps say that it is not clear that the word ‘experience’ cannot be given a topic neutral analysis, perhaps building on Farrell (1950). If we do not need the word ‘experience’ neither do we need the word ‘mental’. Rosenthal (1994) complains (against the identity theorist) that experiences have some characteristically mental properties, and that ‘We inevitably lose the distinctively mental if we construe these properties as neither physical nor mental’. Of course to be topic neutral is to be able to be both physical and mental, just as arithmetic is. There is no need for the word ‘mental’ itself to occur in the topic neutral formula. ‘Mental’, as Ryle (1949) suggests, in its ordinary use is a rather grab-bag term, ‘mental arithmetic’, ‘mental illness’, etc. with which an identity theorist finds no trouble.

In their accounts of mind, David Lewis and D.M. Armstrong emphasise the notion of causality. Lewis's 1966 was a particularly clear headed presentation of the identity theory in which he says (I here refer to the reprint in Lewis 1983, p. 100):

My argument is this: The definitive characteristic of any (sort of) experience as such is its causal role, its syndrome of most typical causes and effects. But we materialists believe that these causal roles which belong by analytic necessity to experiences belong in fact to certain physical states. Since these physical states possess the definitive character of experiences, they must be experiences.

Similarly, Robert Kirk (1999) has argued for the impossibility of zombies. If the supposed zombie has all the behavioural and neural properties ascribed to it by those who argue from the possibility of zombies against materialism, then the zombie is conscious and so not a zombie.

Thus there is no need for explicit use of Ockham's Razor as in Smart (1959) though not in Place (1956). (See Place 1960.) Lewis's paper was extremely valuable and already there are hints of a marriage between the identity theory of mind and so-called ‘functionalist’ ideas that are explicit in Lewis 1972 and 1994. In his 1972 (‘Psychophysical and Theoretical Identifications’) he applies ideas in his more formal paper ‘How to Define Theoretical Terms’ (1970). Folk psychology contains words such as ‘sensation’, ‘perceive’, ‘belief, ‘desire’, ‘emotion’, etc. which we recognise as psychological. Words for colours, smells, sounds, tastes and so on also occur. One can regard common sense platitudes containing both these sorts of these words as constituting a theory and we can take them as theoretical terms of common sense psychology and thus as denoting whatever entities or sorts of entities uniquely realise the theory. Then if certain neural states do so too (as we believe) then the mental states must be these neural states. In his 1994 he allows for tact in extracting a consistent theory from common sense. One cannot uncritically collect platitudes, just as in producing a grammar, implicit in our speech patterns, one must allow for departures from what on our best theory would constitute grammaticality.

A great advantage of this approach over the early identity theory is its holism. Two features of this holism should be noted. One is that the approach is able to allow for the causal interactions between brain states and processes themselves, as well as in the case of external stimuli and responses. Another is the ability to draw on the notion of Ramseyfication of a theory. F.P. Ramsey had shown how to replace the theoretical terms of a theory such as ‘the property of being an electron’ by ‘the property X such that...’. so that when this is done for all the theoretical terms, we are left only with ‘property X such that’, ‘property Y such that’ etc. Take the terms describing behaviour as the observation terms and psychological terms as the theoretical ones of folk psychology. Then Ramseyfication shows that folk psychology is compatible with materialism. This seems right, though perhaps the earlier identity theory deals more directly with reports of immediate experience.

The causal approach was also characteristic of D.M. Armstrong's careful conceptual analysis of mental states and processes, such as perception and the secondary qualities, sensation, consciousness, belief, desire, emotion, voluntary action, in his A Materialist Theory of the Mind (1968a) with a second edition (1993) containing a valuable new preface. Parts I and II of this book are concerned with conceptual analysis, paving the way for a contingent identification of mental states and processes with material ones. As had Brian Medlin, in an impressive critique of Ryle and defence of materialism (Medlin 1967), Armstrong preferred to describe the identity theory as ‘Central State Materialism’. Independently of Armstrong and Lewis, Medlin's central state materialism depended, as theirs did, on a causal analysis of concepts of mental states and processes. See Medlin 1967, and 1969 (including endnote 1).

Mention should particularly be made here of two of Armstrong's other books, one on perception (1961), and one on bodily sensations, (1962). Armstrong thought of perception as coming to believe by means of the senses (compare also Pitcher 1971). This combines the advantages of Direct Realism with hospitality towards the scientific causal story which had been thought to have supported the earlier representative theory of perception. Armstrong regarded bodily sensations as perceptions of states of our body. Of course the latter may be mixed up with emotional states, as an itch may include a propensity to scratch, and contrariwise in exceptional circumstances pain may be felt without distress. However, Armstrong sees the central notion here as that of perception. This suggests a terminological problem. Smart had talked of visual sensations. These were not perceptions but something which occurred in perception. So in this sense of ‘sensation’ there should be bodily sensation sensations. The ambiguity could perhaps be resolved by using the word ‘sensing’ in the context of ‘visual’, ‘auditory’, ‘tactile’ and ‘bodily’, so that bodily sensations would be perceivings which involved introspectible ‘sensings’. These bodily sensations are perceptions and there can be misperceptions as when a person with his foot amputated can think that he has a pain in the foot. He has a sensing ‘having a pain in the foot’ but the world does not contain a pain in the foot, just as it does not contain sense data or images but does contain havings of sense data and of images.

Armstrong's central state materialism involved identifying beliefs and desires with states of the brain (1968a). Smart came to agree with this. On the other hand Place resisted the proposal to extend the identity theory to dispositional states such as beliefs and desires. He stressed that we do not have privileged access to our beliefs and desires. Like Ryle he thought of beliefs and desires as to be elucidated by means of hypothetical statements about behaviour and gave the analogy of the horsepower of a car (Place 1967). However he held that the dispute here is not so much about the neural basis of mental states as about the nature of dispositions. His views on dispositions are argued at length in his debate with Armstrong and Martin (Armstrong, Martin and Place, T. Crane (ed.) 1996). Perhaps we can be relaxed about whether mental states such as beliefs and desires are dispositions or are topic neutrally described neurophysiological states and return to what seems to be the more difficult issue of consciousness. Causal identity theories are closely related to Functionalism, to be discussed in the next section. Smart had been wary of the notion of causality in metaphysics believing that it had no place in theoretical physics. However even so he should have admitted it in folk psychology and also in scientific psychology and biology generally, in which physics and chemistry are applied to explain generalisations rather than strict laws. If folk psychology uses the notion of causality, it is no matter if it is what Quine has called second grade discourse, involving the very contextual notions of modality.

It has commonly been thought that the identity theory has been superseded by a theory called ‘functionalism’. It could be argued that functionalists greatly exaggerate their difference from identity theorists. Indeed some philosophers, such as Lewis (1972 and 1994) and Jackson, Pargetter and Prior (1982), have seen functionalism as a route towards an identity theory.

Like Lewis and Armstrong, functionalists define mental states and processes in terms of their causal relations to behaviour but stop short of identifying them with their neural realisations. Of course the term ‘functionalism’ has been used vaguely and in different ways, and it could be argued that even the theories of Place, Smart and Armstrong were at bottom functionalist. The word ‘functionalist’ has affinities with that of ‘function’ in mathematics and also with that of ‘function’ in biology. In mathematics a function is a set of ordered n-tuples. Similarly if mental processes are defined directly or indirectly by sets of stimulus-response pairs the definitions could be seen as ‘functional’ in the mathematical sense. However there is probably a closer connection with the term as it is used in biology, as one might define ‘eye’ by its function even though a fly's eye and a dog's eye are anatomically and physiologically very different. Functionalism identifies mental states and processes by means of their causal roles, and as noted above in connection with Lewis, we know that the functional roles are possessed by neural states and processes. (There are teleological and homuncular forms of functionalism, which I do not consider here.) Nevertheless an interactionist dualist such as the eminent neurophysiologist Sir John Eccles would (implausibly for most of us) deny that all functional roles are so possessed. One might think of folk psychology, and indeed much of cognitive science too, as analogous to a ‘block diagram’ in electronics. A box in the diagram might be labelled (say) ‘intermediate frequency amplifier’ while remaining) neutral as to the exact circuit and whether the amplification is carried out by a thermionic valve or by a transistor. Using terminology of F. Jackson and P. Pettit (1988, pp. 381–400) the ‘role state’ would be given by ‘amplifier’, the ‘realiser state’ would be given by ‘thermionic valve’, say. So we can think of functionalism as a ‘black box’ theory. This line of thought will be pursued in the next section.

Thinking very much in causal terms about beliefs and desires fits in very well not only with folk psychology but also with Humean ideas about the motives of action. Though this point of view has been criticised by some philosophers it does seem to be right, as can be seen if we consider a possible robot aeroplane designed to find its way from Melbourne to Sydney. The designer would have to include an electronic version of something like a map of south-eastern Australia. This would provide the ‘belief’ side. One would also have to program in an electronic equivalent of ‘go to Sydney’. This program would provide the ‘desire’ side. If wind and weather pushed the aeroplane off course then negative feedback would push the aeroplane back on to the right course for Sydney. The existence of purposive mechanisms has at last (I hope) shown to philosophers that there is nothing mysterious about teleology. Nor are there any great semantic problems over intentionality (with a ‘t’). Consider the sentence ‘Joe desires a unicorn’. This is not like ‘Joe kicks a football’. For Joe to kick a football there must be a football to be kicked, but there are no unicorns. However we can say ‘Joe desires-true of himself "possesses a unicorn" ’. Or more generally ‘Joe believes-true S’ or ‘Joe desires-true S’ where S is an appropriate sentence (Quine 1960, pp. 206–16). Of course if one does not want to relativise to a language one needs to insert ‘or some samesayer of S’ or use the word ‘proposition’, and this involves the notion of proposition or intertranslatability. Even if one does not accept Quine's notion of indeterminacy of translation, there is still fuzziness in the notions of ‘belief’ and ‘desire’ arising from the fuzziness of ‘analyticity’ and ‘synonymy’. The identity theorist could say that on any occasion this fuzziness is matched by the fuzziness of the brain state that constitutes the belief or desire. Just how many interconnections are involved in a belief or desire? On a holistic account such as Lewis's one need not suppose that individuation of beliefs and desires is precise, even though good enough for folk psychology and Humean metaethics. Thus the way in which the brain represents the world might not be like a language. The representation might be like a map. A map relates every feature on it to every other feature. Nevertheless maps contain a finite amount of information. They have not infinitely many parts, still less continuum many. We can think of beliefs as expressing the different bits of information that could be extracted from the map. Thinking in this way beliefs would correspond near enough to the individualist beliefs characteristic of folk and Humean psychology.

The notion ‘type’ and ‘token’ here comes by analogy from ‘type’ and ‘token’ as applied to words. A telegram ‘love and love and love’ contains only two type words but in another sense, as the telegraph clerk would insist, it contains five words (‘token words’). Similarly a particular pain (more exactly a having a pain) according to the token identity theory is identical to a particular brain process. A functionalist could agree to this. Functionalism came to be seen as an improvement on the identity theory, and as inconsistent with it, because of the correct assertion that a functional state can be realised by quite different brain states: thus a functional state might be realised by a silicon based brain as well as by a carbon based brain, and leaving robotics or science fiction aside, my feeling of toothache could be realised by a different neural process from what realises your toothache.

As far as this goes a functionalist can at any rate accept token identities. Functionalists commonly deny type identities. However Jackson, Pargetter and Prior (1982) and Braddon-Mitchell and Jackson (1996) argue that this is an over-reaction on the part of the functionalist. (Indeed they see functionalism as a route to the identity theory.) The functionalist may define mental states as having some state or other (e.g., carbon based or silicon based) which accounts for the functional properties. The functionalist second order state is a state of having some first order state or other which causes or is caused by the behaviour to which the functionalist alludes. In this way we have a second order type theory. Compare brittleness. The brittleness of glass and the brittleness of biscuits are both the state of having some property which explains their breaking, though the first order physical property may be different in the two cases. This way of looking at the matter is perhaps more plausible in relation to mental states such as beliefs and desires than it is to immediately reported experiences. When I report a toothache I do seem to be concerned with first order properties, even though topic neutral ones.

If we continue to concern ourselves with first order properties, we could say that the type-token distinction is not an all or nothing affair. We could say that human experiences are brain processes of one lot of sorts and Alpha Centaurian experiences are brain processes of another lot of sorts. We could indeed propose much finer classifications without going to the limit of mere token identities.

How restricted should be the restriction of a restricted type theory? How many hairs must a bald man have no more of? An identity theorist would expect his toothache today to be very similar to his toothache yesterday. He would expect his toothache to be quite similar to his wife's toothache. He would expect his toothache to be somewhat similar to his cat's toothache. He would not be confident about similarity to an extra-terrestrial's pain. Even here, however, he might expect some similarities of wave form or the like.

Even in the case of the similarity of my pain now to my pain ten minutes ago, there will be unimportant dissimilarities, and also between my pain and your pain. Compare topiary, making use of an analogy exploited by Quine in a different connection. In English country gardens the tops of box hedges are often cut in various shapes, for example peacock shapes. One might make generalizations about peacock shapes on box hedges, and one might say that all the imitation peacocks on a particular hedge have the same shape. However if we approach the two imitation peacocks and peer into them to note the precise shapes of the twigs that make them up we will find differences. Whether we say that two things are similar or not is a matter of abstractness of description. If we were to go to the limit of concreteness the types would shrink to single membered types, but there would still be no ontological difference between identity theory and functionalism.

An interesting form of token identity theory is the anomalous monism of Davidson 1980. Davidson argues that causal relations occur under the neural descriptions but not under the descriptions of psychological language. The latter descriptions use intentional predicates, but because of indeterminacy of translation and of interpretation, these predicates do not occur in law statements. It follows that mind-brain identities can occur only on the level of individual (token) events. It would be beyond the scope of the present essay to consider Davidson's ingenious approach, since it differs importantly from the more usual forms of identity theory.

Place answered the question ‘Is Consciousness a Brain Process?’ in the affirmative. But what sort of brain process? It is natural to feel that there is something ineffable about which no mere neurophysiological process (with only physical intrinsic properties) could have. There is a challenge to the identity theorist to dispel this feeling.

Suppose that I am riding my bicycle from my home to the university. Suddenly I realise that I have crossed a bridge over a creek, gone along a twisty path for half a mile, avoided oncoming traffic, and so on, and yet have no memories of all this. In one sense I was conscious: I was perceiving, getting information about my position and speed, the state of the bicycle track and the road, the positions and speeds of approaching cars, the width of the familiar narrow bridge. But in another sense I was not conscious: I was on ‘automatic pilot’. So let me use the word ‘awareness’ for this automatic or subconscious sort of consciousness. Perhaps I am not one hundred percent on automatic pilot. For one thing I might be absent minded and thinking about philosophy. Still, this would not be relevant to my bicycle riding. One might indeed wonder whether one is ever one hundred percent on automatic pilot, and perhaps one hopes that one isn't, especially in Armstrong's example of the long distance truck driver (Armstrong 1962). Still it probably does happen, and if it does the driver is conscious only in the sense that he or she is alert to the route, of oncoming traffic etc., i.e. is perceiving in the sense of ‘coming to believe by means of the senses’. The driver gets the beliefs but is not aware of doing so. There is no suggestion of ineffability in this sense of ‘consciousness’, for which I shall reserve the term ‘awareness’.

For the full consciousness, the one that puzzles us and suggests ineffability, we need the sense elucidated by Armstrong in a debate with Norman Malcolm (Armstrong and Malcolm 1962, p. 110). Somewhat similar views have been expressed by other philosophers, such as Savage (1976), Dennett (1991), Lycan (1996), Rosenthal (1996). A recent presentation of it is in Smart (2004). In the debate with Norman Malcolm, Armstrong compared consciousness with proprioception. A case of proprioception occurs when with our eyes shut and without touch we are immediately aware of the angle at which one of our elbows is bent. That is, proprioception is a special sense, different from that of bodily sensation, in which we become aware of parts of our body. Now the brain is part of our body and so perhaps immediate awareness of a process in, or a state of, our brain may here for present purposes be called ‘proprioception’. Thus the proprioception even though the neuroanatomy is different. Thus the proprioception which constitutes consciousness, as distinguished from mere awareness, is a higher order awareness, a perception of one part of (or configuration in) our brain by the brain itself. Some may sense circularity here. If so let them suppose that the proprioception occurs in an in practice negligible time after the process propriocepted. Then perhaps there can be proprioceptions of proprioceptions, proprioceptions of proprioceptions of proprioceptions, and so on up, though in fact the sequence will probably not go up more than two or three steps. The last proprioception in the sequence will not be propriocepted, and this may help to explain our sense of the ineffability of consciousness. Compare Gilbert Ryle in The Concept of Mind on the systematic elusiveness of ‘I’ (Ryle 1949, pp. 195–8).

Place has argued that the function of the ‘automatic pilot’, to which he refers as ‘the zombie within’, is to alert consciousness to inputs which it identifies as problematic, while it ignores non-problematic inputs or re-routes them to output without the need for conscious awareness. For this view of consciousness see Place (1999).

Mention should here be made of influential criticisms of the identity theory by Saul Kripke and David Chalmers respectively. It will not be possible to discuss them in great detail, partly because of the fact that Kripke's remarks rely on views about modality, possible worlds semantics, and essentialism which some philosophers would want to contest, and because Chalmers' long and rich book would deserve a lengthy answer. Kripke (1980) calls an expression a rigid designator if it refers to the same object in every possible world. Or in counterpart theory it would have an exactly similar counterpart in every possible world. It seems to me that what we count as counterparts is highly contextual. Take the example ‘water is H 2 O’. In another world, or in a twin earth in our world as Putnam imagines (1975), the stuff found in rivers, lakes, the sea would not be H 2 O but XYZ and so would not be water. This is certainly giving preference to real chemistry over folk chemistry, and so far I applaud this. There are therefore contexts in which we say that on twin earth or the envisaged possible world the stuff found in rivers would not be water. Nevertheless there are contexts in which we could envisage a possible world (write a science fiction novel) in which being found in rivers and lakes and the sea, assuaging thirst and sustaining life was more important than the chemical composition and so XYZ would be the counterpart of H 2 O.

Kripke considers the identity ‘heat = molecular motion’, and holds that this is true in every possible world and so is a necessary truth. Actually the proposition is not quite true, for what about radiant heat? What about heat as defined in classical thermodynamics which is ‘topic neutral’ compared with statistical thermodynamics? Still, suppose that heat has an essence and that it is molecular motion, or at least is in the context envisaged. Kripke says (1980, p. 151) that when we think that molecular motion might exist in the absence of heat we are confusing this with thinking that the molecular motion might have existed without being felt as heat. He asks whether it is analogously possible that if pain is a certain sort of brain process that it has existed without being felt as pain. He suggests that the answer is ‘No’. An identity theorist who accepted the account of consciousness as a higher order perception could answer ‘Yes’. We might be aware of a damaged tooth and also of being in an agitation condition (to use Ryle's term for emotional states) without being aware of our awareness. An identity theorist such as Smart would prefer talk of ‘having a pain’ rather than of ‘pain’: pain is not part of the furniture of the world any more than a sense datum or the average plumber is. Kripke concludes (p. 152) that the

apparent contingency of the connection between the mental state and the corresponding brain state thus cannot be explained by some sort of qualitative analogue as in the case of heat.

Smart would say that there is a sense in which the connection of sensations (sensings) and brain processes is only half contingent. A complete description of the brain state or process (including causes and effects of it) would imply the report of inner experience, but the latter, being topic neutral and so very abstract would not imply the neurological description.

Chalmers (1996) in the course of his exhaustive study of consciousness developed a theory of non-physical qualia which to some extent avoids the worry about nomological danglers. The worry expressed by Smart (1959) is that if there were non-physical qualia there would, most implausibly, have to be laws relating neurophysiological processes to apparently simple properties, and the correlation laws would have to be fundamental, mere danglers from the nomological net (as Feigl called it) of science. Chalmers counters this by supposing that the qualia are not simple but unknown to us, are made up of simple proto-qualia, and that the fundamental laws relating these to physical entities relate them to fundamental physical entities. His view comes to a rather interesting panpsychism. On the other hand if the topic neutral account is correct, then qualia are no more than points in a multidimensional similarity space, and the overwhelming plausibility will fall on the side of the identity theorist.

On Chalmers' view how are we aware of non-physical qualia? It has been suggested above that this inner awareness is proprioception of the brain by the brain. But what sort of story is possible in the case of awareness of a quale? Chalmers could have some sort of answer to this by means of his principle of coherence according to which the causal neurological story parallels the story of succession of qualia. It is not clear however that this would make us aware of the qualia. The qualia do not seem to be needed in the physiological story of how an antelope avoids a tiger.

People often think that even if a robot could scan its own perceptual processes this would not mean that the robot was conscious. This appeals to our intuitions, but perhaps we could reverse the argument and say that because the robot can be aware of its awareness the robot is conscious. I have given reason above to distrust intuitions, but in any case Chalmers comes some of the way in that he toys with the idea that a thermostat has a sort of proto-qualia. The dispute between identity theorists (and physicalists generally) and Chalmers comes down to our attitude to phenomenology. Certainly walking in a forest, seeing the blue of the sky, the green of the trees, the red of the track, one may find it hard to believe that our qualia are merely points in a multidimensional similarity space. But perhaps that is what it is like (to use a phrase that can be distrusted) to be aware of a point in a multidimensional similarity space. One may also, as Place would suggest, be subject to ‘the phenomenological fallacy’. At the end of his book Chalmers makes some speculations about the interpretation of quantum mechanics. If they succeed then perhaps we could envisage Chalmers' theory as integrated into physics and him as a physicalist after all. However it could be doubted whether we need to go down to the quantum level to understand consciousness or whether consciousness is relevant to quantum mechanics.

- Armstrong, D.M., 1961, Perception and the Physical World , London: Routledge.

- –––, 1961, Bodily Sensations , London: Routledge.

- –––, 1962, ‘Consciousness and Causality’, and ‘Reply’, in D.M. Armstrong N. Malcolm, Consciousness and Causality , Oxford: Blackwell.

- –––, 1968a, A Materialist Theory of the Mind , London: Routledge; second edition, with new preface, 1993.

- –––, 1968b, ‘The Headless Woman Illusion and the Defence of Materialism’, Analysis , 29: 48–49.

- –––, 1999, The Mind-Body Problem: An Opinionated Introduction , Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Armstrong, D.M., Martin, C.B. and Place, U.T., 1996, Dispositions: A Debate , T. Crane (ed.), London: Routledge.

- Braddon-Mitchell, D. and Jackson, F., 1996: Philosophy of Mind and Cognition , Oxford: Blackwell.

- Broad, C.D., 1937, The Mind and its Place in Nature , London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Campbell, K., 1984, Body and Mind , Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Carnap, R., 1932, ‘Psychologie in Physikalischer Sprache’, Erkenntnis , 3: 107–142. English translation in A.J. Ayer (ed.), Logical Positivism , Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1959.

- –––, 1963, ‘Herbert Feigl on Physicalism’, in Schilpp 1963, pp. 882–886.

- Chalmers, D.M., 1996, The Conscious Mind , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Clark, A., 1993, Sensory Qualities , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Davidson, D., 1980, ‘Mental Events’, ‘The Material Mind’ and ‘Psychology as Part of Philosophy’, in D. Davidson, Essays on Actions and Events , Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Dennett, D.C., 1991, Consciousness Explained , Boston: Little and Brown.

- Farrell, B.A., 1950, ‘Experience’, Mind , 50: 170–198.

- Feigl, H., 1958, ‘The “Mental” and the “Physical”’, in H. Feigl, M. Scriven and G. Maxwell (eds.), Concepts, Theories and the Mind-Body Problem (Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Volume 2), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; reprinted with a Postscript in Feigl 1967.

- –––, 1967, The ‘Mental’ and the ‘Physical’, The Essay and a Postscript , Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Heil, J., 1989, Cause, Mind and Reality: Essays Honoring C.B. Martin , Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Hilbert, D.R., 1987, Color and Color Perception: A Study in Anthropocentric Realism , Stanford: CSLI Publications.

- Hill, C.S., 1991, Sensations: A Defense of Type Materialism , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jackson, F., 1998, ‘What Mary didn't know’, and ‘Postscript on qualia’, in F. Jackson, Mind, Method and Conditionals , London: Routledge.

- Jackson, F. and Pettit, P., 1988, ‘Functionalism and Broad Content’, Mind , 97: 381–400.

- Jackson, F., Pargetter, R. and Prior, E., 1982, ‘Functionalism and Type-Type Identity Theories’, Philosophical Studies , 42: 209–225.

- Kirk, R., 1999, ‘Why There Couldn't be Zombies’, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society (Supplementary Volume), 73: 1–16.

- Kripke, S., 1980, Naming and Necessity , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Levin, M.E., 1979, Metaphysics and the Mind-Body Problem , Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Lewis, D., 1966, ‘An Argument for the Identity Theory’, Journal of Philosophy , 63: 17–25.

- –––, 1970, ‘How to Define Theoretical Terms’, Journal of Philosophy , 67: 427–446.

- –––, 1972, ‘Psychophysical and Theoretical Identifications’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy , 50: 249–258.

- –––, 1983, ‘Mad Pain and Martian Pain’ and ‘Postscript’, in D. Lewis, Philosophical Papers (Volume 1), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- –––, 1989, ‘What Experience Teaches’, in W. Lycan (ed.), Mind and Cognition , Oxford: Blackwell

- –––, 1994, ‘Reduction of Mind’, in S. Guttenplan (ed.), A Companion to the Philosophy of Mind , Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lycan, W.G., 1996, Consciousness and Experience , Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Medlin, B.H., 1967, ‘Ryle and the Mechanical Hypothesis’, in C.F. Presley (ed.), The Identity Theory of Mind , St. Lucia, Queensland: Queensland University Press.

- –––, 1969, ‘Materialism and the Argument from Distinct Existences’, in J.J. MacIntosh and S. Coval (eds.), The Business of Reason , London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Pitcher, G., 1971, A Theory of Perception , Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Place, U.T., 1954, ‘The Concept of Heed’, British Journal of Psychology , 45: 243–255.

- –––, 1956, ‘Is Consciousness a Brain Process?’, British Journal of Psychology , 47: 44–50.

- –––, 1960, ‘Materialism as a Scientific Hypothesis’, Philosophical Review , 69: 101–104.

- –––, 1967, ‘Comments on Putnam's “Psychological Predicates”’, in W.H. Capitan and D.D. Merrill (eds.), Art, Mind and Religion , Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press.

- –––, 1988, ‘Thirty Years on–Is Consciousness still a Brain Process?’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy , 66: 208–219.

- –––, 1989, ‘Low Claim Assertions’, in J. Heil (ed.), Cause, Mind and Reality: Essays Honoring C.B. Martin , Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- –––, 1990, ‘E.G. Boring and the Mind-Brain Identity Theory’, British Psychological Society, History and Philosophy of Science Newsletter , 11: 20–31.

- –––, 1999, ‘Connectionism and the Problem of Consciousness’, Acta Analytica , 22: 197–226.

- –––, 2004, Identifying the Mind , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Putnam, H., 1960, ‘Minds and Machines’, in S. Hook (ed.), Dimensions of Mind , New York: New York University Press.

- –––, 1975, ‘The Meaning of “Meaning”’, in H. Putnam, Mind, Language and Reality , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Quine, W.V.O., 1960, Word and Object , Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Reichenbach, H., 1938, Experience and Prediction , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rosenthal, D.M., 1994, ‘Identity Theories’, in S. Guttenplan (ed.), A Companion to the Philosophy of Mind , Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 348–355.

- –––, 1996, ‘A Theory of Consciousness’, in N. Block, O. Flanagan, and G. Güzeldere (eds.), The Nature of Consciousness , Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ryle, G., 1949, The Concept of Mind , London: Hutchinson.

- Savage, C.W., 1976, ‘An Old Ghost in a New Body’, in G.G. Globus, G. Maxwell and I. Savodnik (eds.), Consciousness and the Brain , New York: Plenum Press.

- Schilpp, P.A. (ed.), 1963, The Philosophy of Rudolf Carnap , La Salle, IL: Open Court.

- Schlick, M., 1935, ‘De la Relation des Notions Psychologiques et des Notions Physiques’, Revue de Synthese , 10: 5–26; English translation in H. Feigl and W. Sellars (eds.), Readings in Philosophical Analysis , New York: Appleton-Century Crofts, 1949.

- Smart, J.J.C., 1959, ‘Sensations and Brain Processes’, Philosophical Review , 68: 141–156.

- –––, 1961, ‘Colours’, Philosophy , 36: 128–142.

- –––, 1963, ‘Materialism’, Journal of Philosophy , 60: 651–662.

- –––, 1975, ‘On Some Criticisms of a Physicalist Theory of Colour’, in Chung-ying Cheng (ed.), Philosophical Aspects of the Mind-Body Problem , Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

- –––, 1978, ‘The Content of Physicalism’, Philosophical Quarterly , 28: 339–341.

- –––, 1981, ‘Physicalism and Emergence’, Neuroscience , 6: 109–113.

- –––, 1995, ‘“Looks Red” and Dangerous Talk’, Philosophy , 70: 545–554.

- –––, 2004, ‘Consciousness and Awareness’, Journal of Consciousness Studies , 11: 41–50.

How to cite this entry . Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society . Look up topics and thinkers related to this entry at the Internet Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO). Enhanced bibliography for this entry at PhilPapers , with links to its database.

[Please contact the author with suggestions.]

- Identity Theories , an incomplete paper by U.T. Place, published in the Field Guide to Philosophy of Mind

consciousness | functionalism

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my thanks to David Armstrong, Frank Jackson and Ullin Place for comments on an earlier draft of this article and David Chalmers for careful editorial suggestions.

Copyright © 2007 by J. J. C. Smart

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2023 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.