Research Methodology

- Introduction to Research Methodology

- Research Approaches

- Concepts of Theory and Empiricism

- Characteristics of scientific method

- Understanding the Language of Research

- 11 Steps in Research Process

- Research Design

- Different Research Designs

Compare and Contrast the Main Types of Research Designs

- Cross-sectional research design

- Qualitative and Quantitative Research

- Descriptive Research VS Qualitative Research

- Experimental Research VS Quantitative Research

- Sampling Design

- Probability VS Non-Probability Sampling

- 40 MCQ on Research Methodology

- MCQ on research Process

- MCQ on Research Design

- 18 MCQ on Quantitative Research

- 30 MCQ on Qualitative Research

- 45 MCQ on Sampling Methods

- 20 MCQ on Principles And Planning For Research

Research designs vary in their approach to gathering data, the level of control over variables, and the extent to which they allow for making causal inferences or generalizations. Let’s compare and contrast the main types of research designs:

- Purpose: To describe characteristics, behaviors, or phenomena as they naturally occur without manipulating variables.

- Method: Often involves surveys, observations, and content analysis.

- Control: Minimal control over variables, as the focus is on observing and documenting existing conditions.

- Inference: Limited ability to establish causality or draw causal relationships.

- Generalization: Findings are specific to the sample studied and may not be generalizable to other populations.

- Purpose: To examine relationships between two or more variables and measure the strength and direction of their association.

- Method: Involves collecting data on variables and using statistical techniques to analyze correlations.

- Control: Little to moderate control over variables, as researchers do not manipulate them.

- Inference: Correlation does not imply causation; therefore, causal relationships cannot be established.

- Generalization: Limited ability to generalize beyond the sample studied.

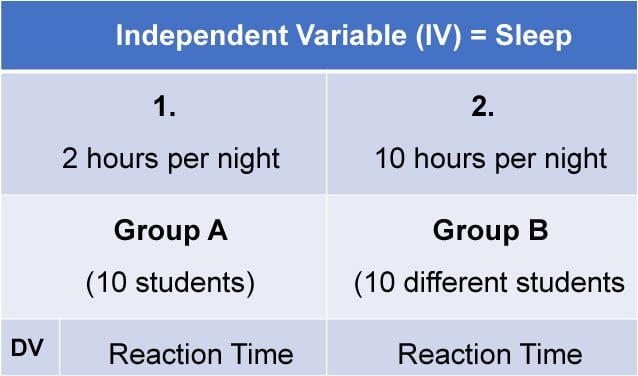

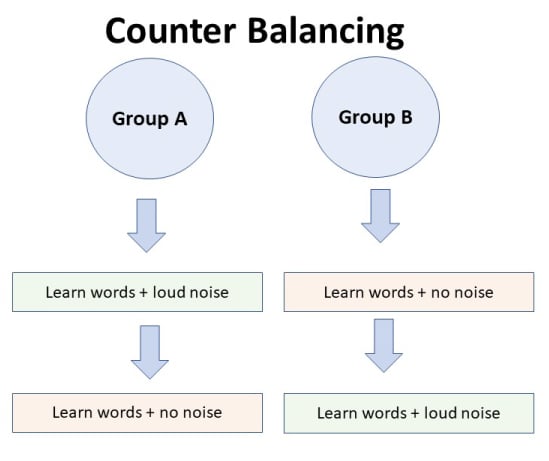

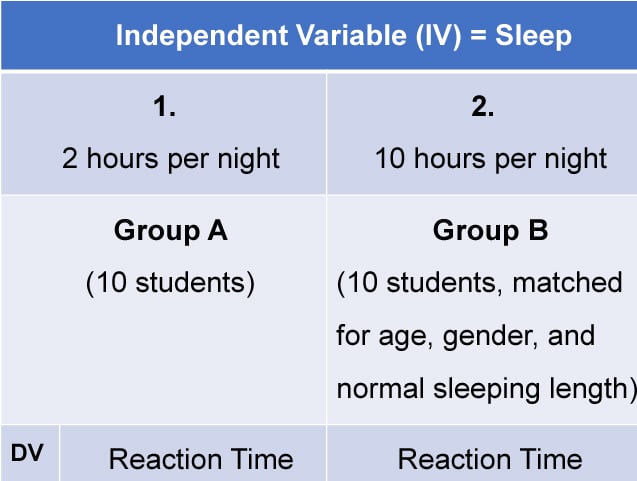

- Purpose: To establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables by manipulating one or more independent variables.

- Method: Involves random assignment of participants to experimental and control groups, followed by the manipulation of variables.

- Control: High control over variables, allowing for comparisons between groups and causal conclusions.

- Inference: With proper randomization and control, experimental designs support causal inferences.

- Generalization: Findings can be generalized to the population under study if the sample is representative.

- Purpose: To investigate cause-and-effect relationships when random assignment is not feasible or ethical .

- Method: Involves comparing groups that already exist based on specific characteristics.

- Control: Moderate control over variables, but not as strong as in true experimental designs.

- Inference: Causal claims are weaker than in true experiments due to potential confounding variables .

- Generalization: Generalizability depends on the representativeness of the sample.

- Purpose: To study changes or developments over an extended period by collecting data at multiple time points.

- Method: Involves repeated measures of the same participants over time.

- Control: Depending on the design, researchers may have varying degrees of control over external factors.

- Inference: Allows for the examination of trends and changes over time but may not establish causality.

- Generalization: Findings can be applicable to the studied population over time.

- Purpose: To collect data at a single point in time to study the relationships between variables.

- Method: Involves data collection from different participants representing different groups.

- Control: Minimal control over external factors, as researchers only observe the variables of interest.

- Inference: Provides a snapshot of the relationships between variables, but causality cannot be established .

Each research design has its strengths and limitations, and the choice of design depends on the research question, the level of control needed, and the resources available. Proper selection and execution of the research design are crucial to obtaining valid and reliable results.

Comparison table summarizing the main characteristics of different research designs:

| Research Design | Purpose | Methodology | Control over Variables | Causal Inference | Generalizability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive | Describe phenomena | Surveys, observations, content analysis | Minimal | Limited | Limited |

| Correlational | Examine relationships | Data collection and statistical analysis | Little to moderate | No causation implied | Limited |

| Experimental | Establish causality | Random assignment, manipulation of IVs | High | Supported | Generalizable (with care) |

| Quasi-Experimental | Investigate causality | Comparison of pre-existing groups | Moderate | Weaker than true exp. | Dependent on design |

| Longitudinal | Study changes over time | Repeated measures over an extended period | Varies | Trend analysis | Applicable over time |

| Cross-Sectional | Examine relationships | Data collected at a single point in time | Minimal | No causation implied | Limited |

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Types of Research Designs

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Introduction

Before beginning your paper, you need to decide how you plan to design the study .

The research design refers to the overall strategy and analytical approach that you have chosen in order to integrate, in a coherent and logical way, the different components of the study, thus ensuring that the research problem will be thoroughly investigated. It constitutes the blueprint for the collection, measurement, and interpretation of information and data. Note that the research problem determines the type of design you choose, not the other way around!

De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Trochim, William M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

General Structure and Writing Style

The function of a research design is to ensure that the evidence obtained enables you to effectively address the research problem logically and as unambiguously as possible . In social sciences research, obtaining information relevant to the research problem generally entails specifying the type of evidence needed to test the underlying assumptions of a theory, to evaluate a program, or to accurately describe and assess meaning related to an observable phenomenon.

With this in mind, a common mistake made by researchers is that they begin their investigations before they have thought critically about what information is required to address the research problem. Without attending to these design issues beforehand, the overall research problem will not be adequately addressed and any conclusions drawn will run the risk of being weak and unconvincing. As a consequence, the overall validity of the study will be undermined.

The length and complexity of describing the research design in your paper can vary considerably, but any well-developed description will achieve the following :

- Identify the research problem clearly and justify its selection, particularly in relation to any valid alternative designs that could have been used,

- Review and synthesize previously published literature associated with the research problem,

- Clearly and explicitly specify hypotheses [i.e., research questions] central to the problem,

- Effectively describe the information and/or data which will be necessary for an adequate testing of the hypotheses and explain how such information and/or data will be obtained, and

- Describe the methods of analysis to be applied to the data in determining whether or not the hypotheses are true or false.

The research design is usually incorporated into the introduction of your paper . You can obtain an overall sense of what to do by reviewing studies that have utilized the same research design [e.g., using a case study approach]. This can help you develop an outline to follow for your own paper.

NOTE: Use the SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases and the SAGE Research Methods Videos databases to search for scholarly resources on how to apply specific research designs and methods . The Research Methods Online database contains links to more than 175,000 pages of SAGE publisher's book, journal, and reference content on quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research methodologies. Also included is a collection of case studies of social research projects that can be used to help you better understand abstract or complex methodological concepts. The Research Methods Videos database contains hours of tutorials, interviews, video case studies, and mini-documentaries covering the entire research process.

Creswell, John W. and J. David Creswell. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2018; De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Leedy, Paul D. and Jeanne Ellis Ormrod. Practical Research: Planning and Design . Tenth edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2013; Vogt, W. Paul, Dianna C. Gardner, and Lynne M. Haeffele. When to Use What Research Design . New York: Guilford, 2012.

Action Research Design

Definition and Purpose

The essentials of action research design follow a characteristic cycle whereby initially an exploratory stance is adopted, where an understanding of a problem is developed and plans are made for some form of interventionary strategy. Then the intervention is carried out [the "action" in action research] during which time, pertinent observations are collected in various forms. The new interventional strategies are carried out, and this cyclic process repeats, continuing until a sufficient understanding of [or a valid implementation solution for] the problem is achieved. The protocol is iterative or cyclical in nature and is intended to foster deeper understanding of a given situation, starting with conceptualizing and particularizing the problem and moving through several interventions and evaluations.

What do these studies tell you ?

- This is a collaborative and adaptive research design that lends itself to use in work or community situations.

- Design focuses on pragmatic and solution-driven research outcomes rather than testing theories.

- When practitioners use action research, it has the potential to increase the amount they learn consciously from their experience; the action research cycle can be regarded as a learning cycle.

- Action research studies often have direct and obvious relevance to improving practice and advocating for change.

- There are no hidden controls or preemption of direction by the researcher.

What these studies don't tell you ?

- It is harder to do than conducting conventional research because the researcher takes on responsibilities of advocating for change as well as for researching the topic.

- Action research is much harder to write up because it is less likely that you can use a standard format to report your findings effectively [i.e., data is often in the form of stories or observation].

- Personal over-involvement of the researcher may bias research results.

- The cyclic nature of action research to achieve its twin outcomes of action [e.g. change] and research [e.g. understanding] is time-consuming and complex to conduct.

- Advocating for change usually requires buy-in from study participants.

Coghlan, David and Mary Brydon-Miller. The Sage Encyclopedia of Action Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014; Efron, Sara Efrat and Ruth Ravid. Action Research in Education: A Practical Guide . New York: Guilford, 2013; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 18, Action Research. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Kemmis, Stephen and Robin McTaggart. “Participatory Action Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2000), pp. 567-605; McNiff, Jean. Writing and Doing Action Research . London: Sage, 2014; Reason, Peter and Hilary Bradbury. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2001.

Case Study Design

A case study is an in-depth study of a particular research problem rather than a sweeping statistical survey or comprehensive comparative inquiry. It is often used to narrow down a very broad field of research into one or a few easily researchable examples. The case study research design is also useful for testing whether a specific theory and model actually applies to phenomena in the real world. It is a useful design when not much is known about an issue or phenomenon.

- Approach excels at bringing us to an understanding of a complex issue through detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships.

- A researcher using a case study design can apply a variety of methodologies and rely on a variety of sources to investigate a research problem.

- Design can extend experience or add strength to what is already known through previous research.

- Social scientists, in particular, make wide use of this research design to examine contemporary real-life situations and provide the basis for the application of concepts and theories and the extension of methodologies.

- The design can provide detailed descriptions of specific and rare cases.

- A single or small number of cases offers little basis for establishing reliability or to generalize the findings to a wider population of people, places, or things.

- Intense exposure to the study of a case may bias a researcher's interpretation of the findings.

- Design does not facilitate assessment of cause and effect relationships.

- Vital information may be missing, making the case hard to interpret.

- The case may not be representative or typical of the larger problem being investigated.

- If the criteria for selecting a case is because it represents a very unusual or unique phenomenon or problem for study, then your interpretation of the findings can only apply to that particular case.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 4, Flexible Methods: Case Study Design. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Greenhalgh, Trisha, editor. Case Study Evaluation: Past, Present and Future Challenges . Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing, 2015; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Stake, Robert E. The Art of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1995; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Theory . Applied Social Research Methods Series, no. 5. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2003.

Causal Design

Causality studies may be thought of as understanding a phenomenon in terms of conditional statements in the form, “If X, then Y.” This type of research is used to measure what impact a specific change will have on existing norms and assumptions. Most social scientists seek causal explanations that reflect tests of hypotheses. Causal effect (nomothetic perspective) occurs when variation in one phenomenon, an independent variable, leads to or results, on average, in variation in another phenomenon, the dependent variable.

Conditions necessary for determining causality:

- Empirical association -- a valid conclusion is based on finding an association between the independent variable and the dependent variable.

- Appropriate time order -- to conclude that causation was involved, one must see that cases were exposed to variation in the independent variable before variation in the dependent variable.

- Nonspuriousness -- a relationship between two variables that is not due to variation in a third variable.

- Causality research designs assist researchers in understanding why the world works the way it does through the process of proving a causal link between variables and by the process of eliminating other possibilities.

- Replication is possible.

- There is greater confidence the study has internal validity due to the systematic subject selection and equity of groups being compared.

- Not all relationships are causal! The possibility always exists that, by sheer coincidence, two unrelated events appear to be related [e.g., Punxatawney Phil could accurately predict the duration of Winter for five consecutive years but, the fact remains, he's just a big, furry rodent].

- Conclusions about causal relationships are difficult to determine due to a variety of extraneous and confounding variables that exist in a social environment. This means causality can only be inferred, never proven.

- If two variables are correlated, the cause must come before the effect. However, even though two variables might be causally related, it can sometimes be difficult to determine which variable comes first and, therefore, to establish which variable is the actual cause and which is the actual effect.

Beach, Derek and Rasmus Brun Pedersen. Causal Case Study Methods: Foundations and Guidelines for Comparing, Matching, and Tracing . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016; Bachman, Ronet. The Practice of Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice . Chapter 5, Causation and Research Designs. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press, 2007; Brewer, Ernest W. and Jennifer Kubn. “Causal-Comparative Design.” In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 125-132; Causal Research Design: Experimentation. Anonymous SlideShare Presentation; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 11, Nonexperimental Research: Correlational Designs. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007; Trochim, William M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

Cohort Design

Often used in the medical sciences, but also found in the applied social sciences, a cohort study generally refers to a study conducted over a period of time involving members of a population which the subject or representative member comes from, and who are united by some commonality or similarity. Using a quantitative framework, a cohort study makes note of statistical occurrence within a specialized subgroup, united by same or similar characteristics that are relevant to the research problem being investigated, rather than studying statistical occurrence within the general population. Using a qualitative framework, cohort studies generally gather data using methods of observation. Cohorts can be either "open" or "closed."

- Open Cohort Studies [dynamic populations, such as the population of Los Angeles] involve a population that is defined just by the state of being a part of the study in question (and being monitored for the outcome). Date of entry and exit from the study is individually defined, therefore, the size of the study population is not constant. In open cohort studies, researchers can only calculate rate based data, such as, incidence rates and variants thereof.

- Closed Cohort Studies [static populations, such as patients entered into a clinical trial] involve participants who enter into the study at one defining point in time and where it is presumed that no new participants can enter the cohort. Given this, the number of study participants remains constant (or can only decrease).

- The use of cohorts is often mandatory because a randomized control study may be unethical. For example, you cannot deliberately expose people to asbestos, you can only study its effects on those who have already been exposed. Research that measures risk factors often relies upon cohort designs.

- Because cohort studies measure potential causes before the outcome has occurred, they can demonstrate that these “causes” preceded the outcome, thereby avoiding the debate as to which is the cause and which is the effect.

- Cohort analysis is highly flexible and can provide insight into effects over time and related to a variety of different types of changes [e.g., social, cultural, political, economic, etc.].

- Either original data or secondary data can be used in this design.

- In cases where a comparative analysis of two cohorts is made [e.g., studying the effects of one group exposed to asbestos and one that has not], a researcher cannot control for all other factors that might differ between the two groups. These factors are known as confounding variables.

- Cohort studies can end up taking a long time to complete if the researcher must wait for the conditions of interest to develop within the group. This also increases the chance that key variables change during the course of the study, potentially impacting the validity of the findings.

- Due to the lack of randominization in the cohort design, its external validity is lower than that of study designs where the researcher randomly assigns participants.

Healy P, Devane D. “Methodological Considerations in Cohort Study Designs.” Nurse Researcher 18 (2011): 32-36; Glenn, Norval D, editor. Cohort Analysis . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Levin, Kate Ann. Study Design IV: Cohort Studies. Evidence-Based Dentistry 7 (2003): 51–52; Payne, Geoff. “Cohort Study.” In The SAGE Dictionary of Social Research Methods . Victor Jupp, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), pp. 31-33; Study Design 101. Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library. George Washington University, November 2011; Cohort Study. Wikipedia.

Cross-Sectional Design

Cross-sectional research designs have three distinctive features: no time dimension; a reliance on existing differences rather than change following intervention; and, groups are selected based on existing differences rather than random allocation. The cross-sectional design can only measure differences between or from among a variety of people, subjects, or phenomena rather than a process of change. As such, researchers using this design can only employ a relatively passive approach to making causal inferences based on findings.

- Cross-sectional studies provide a clear 'snapshot' of the outcome and the characteristics associated with it, at a specific point in time.

- Unlike an experimental design, where there is an active intervention by the researcher to produce and measure change or to create differences, cross-sectional designs focus on studying and drawing inferences from existing differences between people, subjects, or phenomena.

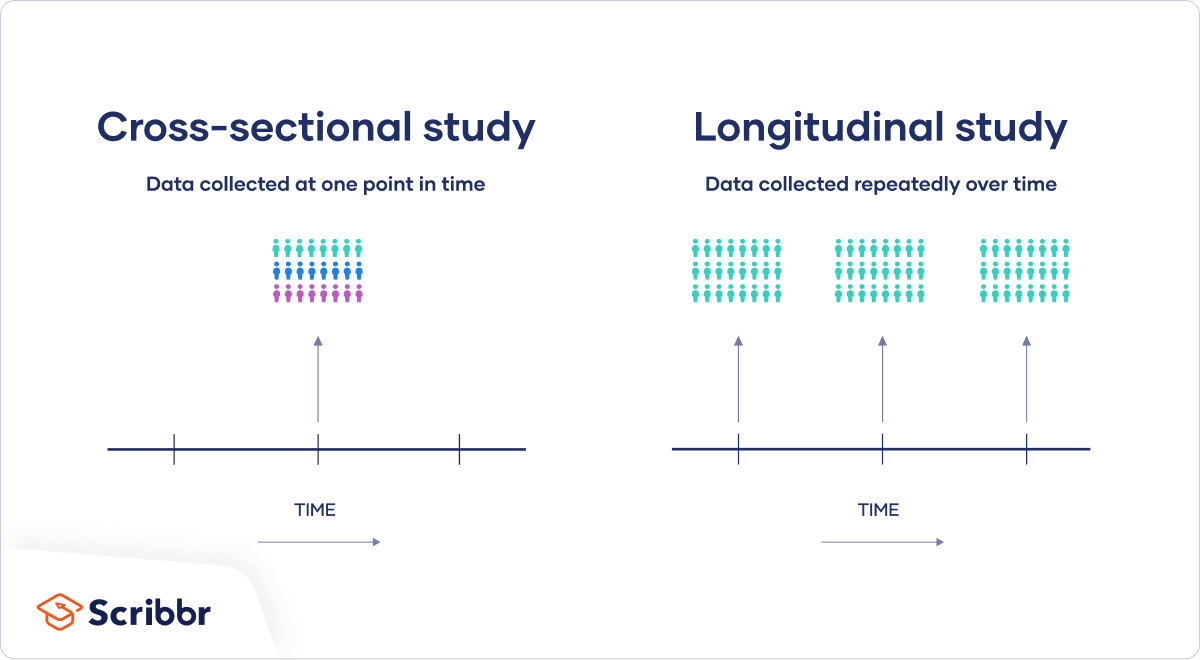

- Entails collecting data at and concerning one point in time. While longitudinal studies involve taking multiple measures over an extended period of time, cross-sectional research is focused on finding relationships between variables at one moment in time.

- Groups identified for study are purposely selected based upon existing differences in the sample rather than seeking random sampling.

- Cross-section studies are capable of using data from a large number of subjects and, unlike observational studies, is not geographically bound.

- Can estimate prevalence of an outcome of interest because the sample is usually taken from the whole population.

- Because cross-sectional designs generally use survey techniques to gather data, they are relatively inexpensive and take up little time to conduct.

- Finding people, subjects, or phenomena to study that are very similar except in one specific variable can be difficult.

- Results are static and time bound and, therefore, give no indication of a sequence of events or reveal historical or temporal contexts.

- Studies cannot be utilized to establish cause and effect relationships.

- This design only provides a snapshot of analysis so there is always the possibility that a study could have differing results if another time-frame had been chosen.

- There is no follow up to the findings.

Bethlehem, Jelke. "7: Cross-sectional Research." In Research Methodology in the Social, Behavioural and Life Sciences . Herman J Adèr and Gideon J Mellenbergh, editors. (London, England: Sage, 1999), pp. 110-43; Bourque, Linda B. “Cross-Sectional Design.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods . Michael S. Lewis-Beck, Alan Bryman, and Tim Futing Liao. (Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004), pp. 230-231; Hall, John. “Cross-Sectional Survey Design.” In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods . Paul J. Lavrakas, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 173-174; Helen Barratt, Maria Kirwan. Cross-Sectional Studies: Design Application, Strengths and Weaknesses of Cross-Sectional Studies. Healthknowledge, 2009. Cross-Sectional Study. Wikipedia.

Descriptive Design

Descriptive research designs help provide answers to the questions of who, what, when, where, and how associated with a particular research problem; a descriptive study cannot conclusively ascertain answers to why. Descriptive research is used to obtain information concerning the current status of the phenomena and to describe "what exists" with respect to variables or conditions in a situation.

- The subject is being observed in a completely natural and unchanged natural environment. True experiments, whilst giving analyzable data, often adversely influence the normal behavior of the subject [a.k.a., the Heisenberg effect whereby measurements of certain systems cannot be made without affecting the systems].

- Descriptive research is often used as a pre-cursor to more quantitative research designs with the general overview giving some valuable pointers as to what variables are worth testing quantitatively.

- If the limitations are understood, they can be a useful tool in developing a more focused study.

- Descriptive studies can yield rich data that lead to important recommendations in practice.

- Appoach collects a large amount of data for detailed analysis.

- The results from a descriptive research cannot be used to discover a definitive answer or to disprove a hypothesis.

- Because descriptive designs often utilize observational methods [as opposed to quantitative methods], the results cannot be replicated.

- The descriptive function of research is heavily dependent on instrumentation for measurement and observation.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 5, Flexible Methods: Descriptive Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Given, Lisa M. "Descriptive Research." In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics . Neil J. Salkind and Kristin Rasmussen, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2007), pp. 251-254; McNabb, Connie. Descriptive Research Methodologies. Powerpoint Presentation; Shuttleworth, Martyn. Descriptive Research Design, September 26, 2008; Erickson, G. Scott. "Descriptive Research Design." In New Methods of Market Research and Analysis . (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017), pp. 51-77; Sahin, Sagufta, and Jayanta Mete. "A Brief Study on Descriptive Research: Its Nature and Application in Social Science." International Journal of Research and Analysis in Humanities 1 (2021): 11; K. Swatzell and P. Jennings. “Descriptive Research: The Nuts and Bolts.” Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants 20 (2007), pp. 55-56; Kane, E. Doing Your Own Research: Basic Descriptive Research in the Social Sciences and Humanities . London: Marion Boyars, 1985.

Experimental Design

A blueprint of the procedure that enables the researcher to maintain control over all factors that may affect the result of an experiment. In doing this, the researcher attempts to determine or predict what may occur. Experimental research is often used where there is time priority in a causal relationship (cause precedes effect), there is consistency in a causal relationship (a cause will always lead to the same effect), and the magnitude of the correlation is great. The classic experimental design specifies an experimental group and a control group. The independent variable is administered to the experimental group and not to the control group, and both groups are measured on the same dependent variable. Subsequent experimental designs have used more groups and more measurements over longer periods. True experiments must have control, randomization, and manipulation.

- Experimental research allows the researcher to control the situation. In so doing, it allows researchers to answer the question, “What causes something to occur?”

- Permits the researcher to identify cause and effect relationships between variables and to distinguish placebo effects from treatment effects.

- Experimental research designs support the ability to limit alternative explanations and to infer direct causal relationships in the study.

- Approach provides the highest level of evidence for single studies.

- The design is artificial, and results may not generalize well to the real world.

- The artificial settings of experiments may alter the behaviors or responses of participants.

- Experimental designs can be costly if special equipment or facilities are needed.

- Some research problems cannot be studied using an experiment because of ethical or technical reasons.

- Difficult to apply ethnographic and other qualitative methods to experimentally designed studies.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 7, Flexible Methods: Experimental Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Chapter 2: Research Design, Experimental Designs. School of Psychology, University of New England, 2000; Chow, Siu L. "Experimental Design." In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 448-453; "Experimental Design." In Social Research Methods . Nicholas Walliman, editor. (London, England: Sage, 2006), pp, 101-110; Experimental Research. Research Methods by Dummies. Department of Psychology. California State University, Fresno, 2006; Kirk, Roger E. Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Trochim, William M.K. Experimental Design. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Rasool, Shafqat. Experimental Research. Slideshare presentation.

Exploratory Design

An exploratory design is conducted about a research problem when there are few or no earlier studies to refer to or rely upon to predict an outcome . The focus is on gaining insights and familiarity for later investigation or undertaken when research problems are in a preliminary stage of investigation. Exploratory designs are often used to establish an understanding of how best to proceed in studying an issue or what methodology would effectively apply to gathering information about the issue.

The goals of exploratory research are intended to produce the following possible insights:

- Familiarity with basic details, settings, and concerns.

- Well grounded picture of the situation being developed.

- Generation of new ideas and assumptions.

- Development of tentative theories or hypotheses.

- Determination about whether a study is feasible in the future.

- Issues get refined for more systematic investigation and formulation of new research questions.

- Direction for future research and techniques get developed.

- Design is a useful approach for gaining background information on a particular topic.

- Exploratory research is flexible and can address research questions of all types (what, why, how).

- Provides an opportunity to define new terms and clarify existing concepts.

- Exploratory research is often used to generate formal hypotheses and develop more precise research problems.

- In the policy arena or applied to practice, exploratory studies help establish research priorities and where resources should be allocated.

- Exploratory research generally utilizes small sample sizes and, thus, findings are typically not generalizable to the population at large.

- The exploratory nature of the research inhibits an ability to make definitive conclusions about the findings. They provide insight but not definitive conclusions.

- The research process underpinning exploratory studies is flexible but often unstructured, leading to only tentative results that have limited value to decision-makers.

- Design lacks rigorous standards applied to methods of data gathering and analysis because one of the areas for exploration could be to determine what method or methodologies could best fit the research problem.

Cuthill, Michael. “Exploratory Research: Citizen Participation, Local Government, and Sustainable Development in Australia.” Sustainable Development 10 (2002): 79-89; Streb, Christoph K. "Exploratory Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Albert J. Mills, Gabrielle Durepos and Eiden Wiebe, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 372-374; Taylor, P. J., G. Catalano, and D.R.F. Walker. “Exploratory Analysis of the World City Network.” Urban Studies 39 (December 2002): 2377-2394; Exploratory Research. Wikipedia.

Field Research Design

Sometimes referred to as ethnography or participant observation, designs around field research encompass a variety of interpretative procedures [e.g., observation and interviews] rooted in qualitative approaches to studying people individually or in groups while inhabiting their natural environment as opposed to using survey instruments or other forms of impersonal methods of data gathering. Information acquired from observational research takes the form of “ field notes ” that involves documenting what the researcher actually sees and hears while in the field. Findings do not consist of conclusive statements derived from numbers and statistics because field research involves analysis of words and observations of behavior. Conclusions, therefore, are developed from an interpretation of findings that reveal overriding themes, concepts, and ideas. More information can be found HERE .

- Field research is often necessary to fill gaps in understanding the research problem applied to local conditions or to specific groups of people that cannot be ascertained from existing data.

- The research helps contextualize already known information about a research problem, thereby facilitating ways to assess the origins, scope, and scale of a problem and to gage the causes, consequences, and means to resolve an issue based on deliberate interaction with people in their natural inhabited spaces.

- Enables the researcher to corroborate or confirm data by gathering additional information that supports or refutes findings reported in prior studies of the topic.

- Because the researcher in embedded in the field, they are better able to make observations or ask questions that reflect the specific cultural context of the setting being investigated.

- Observing the local reality offers the opportunity to gain new perspectives or obtain unique data that challenges existing theoretical propositions or long-standing assumptions found in the literature.

What these studies don't tell you

- A field research study requires extensive time and resources to carry out the multiple steps involved with preparing for the gathering of information, including for example, examining background information about the study site, obtaining permission to access the study site, and building trust and rapport with subjects.

- Requires a commitment to staying engaged in the field to ensure that you can adequately document events and behaviors as they unfold.

- The unpredictable nature of fieldwork means that researchers can never fully control the process of data gathering. They must maintain a flexible approach to studying the setting because events and circumstances can change quickly or unexpectedly.

- Findings can be difficult to interpret and verify without access to documents and other source materials that help to enhance the credibility of information obtained from the field [i.e., the act of triangulating the data].

- Linking the research problem to the selection of study participants inhabiting their natural environment is critical. However, this specificity limits the ability to generalize findings to different situations or in other contexts or to infer courses of action applied to other settings or groups of people.

- The reporting of findings must take into account how the researcher themselves may have inadvertently affected respondents and their behaviors.

Historical Design

The purpose of a historical research design is to collect, verify, and synthesize evidence from the past to establish facts that defend or refute a hypothesis. It uses secondary sources and a variety of primary documentary evidence, such as, diaries, official records, reports, archives, and non-textual information [maps, pictures, audio and visual recordings]. The limitation is that the sources must be both authentic and valid.

- The historical research design is unobtrusive; the act of research does not affect the results of the study.

- The historical approach is well suited for trend analysis.

- Historical records can add important contextual background required to more fully understand and interpret a research problem.

- There is often no possibility of researcher-subject interaction that could affect the findings.

- Historical sources can be used over and over to study different research problems or to replicate a previous study.

- The ability to fulfill the aims of your research are directly related to the amount and quality of documentation available to understand the research problem.

- Since historical research relies on data from the past, there is no way to manipulate it to control for contemporary contexts.

- Interpreting historical sources can be very time consuming.

- The sources of historical materials must be archived consistently to ensure access. This may especially challenging for digital or online-only sources.

- Original authors bring their own perspectives and biases to the interpretation of past events and these biases are more difficult to ascertain in historical resources.

- Due to the lack of control over external variables, historical research is very weak with regard to the demands of internal validity.

- It is rare that the entirety of historical documentation needed to fully address a research problem is available for interpretation, therefore, gaps need to be acknowledged.

Howell, Martha C. and Walter Prevenier. From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001; Lundy, Karen Saucier. "Historical Research." In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods . Lisa M. Given, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 396-400; Marius, Richard. and Melvin E. Page. A Short Guide to Writing about History . 9th edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2015; Savitt, Ronald. “Historical Research in Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 44 (Autumn, 1980): 52-58; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 16, Historical Research. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007.

Longitudinal Design

A longitudinal study follows the same sample over time and makes repeated observations. For example, with longitudinal surveys, the same group of people is interviewed at regular intervals, enabling researchers to track changes over time and to relate them to variables that might explain why the changes occur. Longitudinal research designs describe patterns of change and help establish the direction and magnitude of causal relationships. Measurements are taken on each variable over two or more distinct time periods. This allows the researcher to measure change in variables over time. It is a type of observational study sometimes referred to as a panel study.

- Longitudinal data facilitate the analysis of the duration of a particular phenomenon.

- Enables survey researchers to get close to the kinds of causal explanations usually attainable only with experiments.

- The design permits the measurement of differences or change in a variable from one period to another [i.e., the description of patterns of change over time].

- Longitudinal studies facilitate the prediction of future outcomes based upon earlier factors.

- The data collection method may change over time.

- Maintaining the integrity of the original sample can be difficult over an extended period of time.

- It can be difficult to show more than one variable at a time.

- This design often needs qualitative research data to explain fluctuations in the results.

- A longitudinal research design assumes present trends will continue unchanged.

- It can take a long period of time to gather results.

- There is a need to have a large sample size and accurate sampling to reach representativness.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 6, Flexible Methods: Relational and Longitudinal Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Forgues, Bernard, and Isabelle Vandangeon-Derumez. "Longitudinal Analyses." In Doing Management Research . Raymond-Alain Thiétart and Samantha Wauchope, editors. (London, England: Sage, 2001), pp. 332-351; Kalaian, Sema A. and Rafa M. Kasim. "Longitudinal Studies." In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods . Paul J. Lavrakas, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 440-441; Menard, Scott, editor. Longitudinal Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002; Ployhart, Robert E. and Robert J. Vandenberg. "Longitudinal Research: The Theory, Design, and Analysis of Change.” Journal of Management 36 (January 2010): 94-120; Longitudinal Study. Wikipedia.

Meta-Analysis Design

Meta-analysis is an analytical methodology designed to systematically evaluate and summarize the results from a number of individual studies, thereby, increasing the overall sample size and the ability of the researcher to study effects of interest. The purpose is to not simply summarize existing knowledge, but to develop a new understanding of a research problem using synoptic reasoning. The main objectives of meta-analysis include analyzing differences in the results among studies and increasing the precision by which effects are estimated. A well-designed meta-analysis depends upon strict adherence to the criteria used for selecting studies and the availability of information in each study to properly analyze their findings. Lack of information can severely limit the type of analyzes and conclusions that can be reached. In addition, the more dissimilarity there is in the results among individual studies [heterogeneity], the more difficult it is to justify interpretations that govern a valid synopsis of results. A meta-analysis needs to fulfill the following requirements to ensure the validity of your findings:

- Clearly defined description of objectives, including precise definitions of the variables and outcomes that are being evaluated;

- A well-reasoned and well-documented justification for identification and selection of the studies;

- Assessment and explicit acknowledgment of any researcher bias in the identification and selection of those studies;

- Description and evaluation of the degree of heterogeneity among the sample size of studies reviewed; and,

- Justification of the techniques used to evaluate the studies.

- Can be an effective strategy for determining gaps in the literature.

- Provides a means of reviewing research published about a particular topic over an extended period of time and from a variety of sources.

- Is useful in clarifying what policy or programmatic actions can be justified on the basis of analyzing research results from multiple studies.

- Provides a method for overcoming small sample sizes in individual studies that previously may have had little relationship to each other.

- Can be used to generate new hypotheses or highlight research problems for future studies.

- Small violations in defining the criteria used for content analysis can lead to difficult to interpret and/or meaningless findings.

- A large sample size can yield reliable, but not necessarily valid, results.

- A lack of uniformity regarding, for example, the type of literature reviewed, how methods are applied, and how findings are measured within the sample of studies you are analyzing, can make the process of synthesis difficult to perform.

- Depending on the sample size, the process of reviewing and synthesizing multiple studies can be very time consuming.

Beck, Lewis W. "The Synoptic Method." The Journal of Philosophy 36 (1939): 337-345; Cooper, Harris, Larry V. Hedges, and Jeffrey C. Valentine, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis . 2nd edition. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2009; Guzzo, Richard A., Susan E. Jackson and Raymond A. Katzell. “Meta-Analysis Analysis.” In Research in Organizational Behavior , Volume 9. (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1987), pp 407-442; Lipsey, Mark W. and David B. Wilson. Practical Meta-Analysis . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2001; Study Design 101. Meta-Analysis. The Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, George Washington University; Timulak, Ladislav. “Qualitative Meta-Analysis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis . Uwe Flick, editor. (Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2013), pp. 481-495; Walker, Esteban, Adrian V. Hernandez, and Micheal W. Kattan. "Meta-Analysis: It's Strengths and Limitations." Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 75 (June 2008): 431-439.

Mixed-Method Design

- Narrative and non-textual information can add meaning to numeric data, while numeric data can add precision to narrative and non-textual information.

- Can utilize existing data while at the same time generating and testing a grounded theory approach to describe and explain the phenomenon under study.

- A broader, more complex research problem can be investigated because the researcher is not constrained by using only one method.

- The strengths of one method can be used to overcome the inherent weaknesses of another method.

- Can provide stronger, more robust evidence to support a conclusion or set of recommendations.

- May generate new knowledge new insights or uncover hidden insights, patterns, or relationships that a single methodological approach might not reveal.

- Produces more complete knowledge and understanding of the research problem that can be used to increase the generalizability of findings applied to theory or practice.

- A researcher must be proficient in understanding how to apply multiple methods to investigating a research problem as well as be proficient in optimizing how to design a study that coherently melds them together.

- Can increase the likelihood of conflicting results or ambiguous findings that inhibit drawing a valid conclusion or setting forth a recommended course of action [e.g., sample interview responses do not support existing statistical data].

- Because the research design can be very complex, reporting the findings requires a well-organized narrative, clear writing style, and precise word choice.

- Design invites collaboration among experts. However, merging different investigative approaches and writing styles requires more attention to the overall research process than studies conducted using only one methodological paradigm.

- Concurrent merging of quantitative and qualitative research requires greater attention to having adequate sample sizes, using comparable samples, and applying a consistent unit of analysis. For sequential designs where one phase of qualitative research builds on the quantitative phase or vice versa, decisions about what results from the first phase to use in the next phase, the choice of samples and estimating reasonable sample sizes for both phases, and the interpretation of results from both phases can be difficult.

- Due to multiple forms of data being collected and analyzed, this design requires extensive time and resources to carry out the multiple steps involved in data gathering and interpretation.

Burch, Patricia and Carolyn J. Heinrich. Mixed Methods for Policy Research and Program Evaluation . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2016; Creswell, John w. et al. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences . Bethesda, MD: Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health, 2010Creswell, John W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014; Domínguez, Silvia, editor. Mixed Methods Social Networks Research . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014; Hesse-Biber, Sharlene Nagy. Mixed Methods Research: Merging Theory with Practice . New York: Guilford Press, 2010; Niglas, Katrin. “How the Novice Researcher Can Make Sense of Mixed Methods Designs.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 3 (2009): 34-46; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Nancy L. Leech. “Linking Research Questions to Mixed Methods Data Analysis Procedures.” The Qualitative Report 11 (September 2006): 474-498; Tashakorri, Abbas and John W. Creswell. “The New Era of Mixed Methods.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1 (January 2007): 3-7; Zhanga, Wanqing. “Mixed Methods Application in Health Intervention Research: A Multiple Case Study.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 8 (2014): 24-35 .

Observational Design

This type of research design draws a conclusion by comparing subjects against a control group, in cases where the researcher has no control over the experiment. There are two general types of observational designs. In direct observations, people know that you are watching them. Unobtrusive measures involve any method for studying behavior where individuals do not know they are being observed. An observational study allows a useful insight into a phenomenon and avoids the ethical and practical difficulties of setting up a large and cumbersome research project.

- Observational studies are usually flexible and do not necessarily need to be structured around a hypothesis about what you expect to observe [data is emergent rather than pre-existing].

- The researcher is able to collect in-depth information about a particular behavior.

- Can reveal interrelationships among multifaceted dimensions of group interactions.

- You can generalize your results to real life situations.

- Observational research is useful for discovering what variables may be important before applying other methods like experiments.

- Observation research designs account for the complexity of group behaviors.

- Reliability of data is low because seeing behaviors occur over and over again may be a time consuming task and are difficult to replicate.

- In observational research, findings may only reflect a unique sample population and, thus, cannot be generalized to other groups.

- There can be problems with bias as the researcher may only "see what they want to see."

- There is no possibility to determine "cause and effect" relationships since nothing is manipulated.

- Sources or subjects may not all be equally credible.

- Any group that is knowingly studied is altered to some degree by the presence of the researcher, therefore, potentially skewing any data collected.

Atkinson, Paul and Martyn Hammersley. “Ethnography and Participant Observation.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 248-261; Observational Research. Research Methods by Dummies. Department of Psychology. California State University, Fresno, 2006; Patton Michael Quinn. Qualitiative Research and Evaluation Methods . Chapter 6, Fieldwork Strategies and Observational Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002; Payne, Geoff and Judy Payne. "Observation." In Key Concepts in Social Research . The SAGE Key Concepts series. (London, England: Sage, 2004), pp. 158-162; Rosenbaum, Paul R. Design of Observational Studies . New York: Springer, 2010;Williams, J. Patrick. "Nonparticipant Observation." In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods . Lisa M. Given, editor.(Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 562-563.

Philosophical Design

Understood more as an broad approach to examining a research problem than a methodological design, philosophical analysis and argumentation is intended to challenge deeply embedded, often intractable, assumptions underpinning an area of study. This approach uses the tools of argumentation derived from philosophical traditions, concepts, models, and theories to critically explore and challenge, for example, the relevance of logic and evidence in academic debates, to analyze arguments about fundamental issues, or to discuss the root of existing discourse about a research problem. These overarching tools of analysis can be framed in three ways:

- Ontology -- the study that describes the nature of reality; for example, what is real and what is not, what is fundamental and what is derivative?

- Epistemology -- the study that explores the nature of knowledge; for example, by what means does knowledge and understanding depend upon and how can we be certain of what we know?

- Axiology -- the study of values; for example, what values does an individual or group hold and why? How are values related to interest, desire, will, experience, and means-to-end? And, what is the difference between a matter of fact and a matter of value?

- Can provide a basis for applying ethical decision-making to practice.

- Functions as a means of gaining greater self-understanding and self-knowledge about the purposes of research.

- Brings clarity to general guiding practices and principles of an individual or group.

- Philosophy informs methodology.

- Refine concepts and theories that are invoked in relatively unreflective modes of thought and discourse.

- Beyond methodology, philosophy also informs critical thinking about epistemology and the structure of reality (metaphysics).

- Offers clarity and definition to the practical and theoretical uses of terms, concepts, and ideas.

- Limited application to specific research problems [answering the "So What?" question in social science research].

- Analysis can be abstract, argumentative, and limited in its practical application to real-life issues.

- While a philosophical analysis may render problematic that which was once simple or taken-for-granted, the writing can be dense and subject to unnecessary jargon, overstatement, and/or excessive quotation and documentation.

- There are limitations in the use of metaphor as a vehicle of philosophical analysis.

- There can be analytical difficulties in moving from philosophy to advocacy and between abstract thought and application to the phenomenal world.

Burton, Dawn. "Part I, Philosophy of the Social Sciences." In Research Training for Social Scientists . (London, England: Sage, 2000), pp. 1-5; Chapter 4, Research Methodology and Design. Unisa Institutional Repository (UnisaIR), University of South Africa; Jarvie, Ian C., and Jesús Zamora-Bonilla, editors. The SAGE Handbook of the Philosophy of Social Sciences . London: Sage, 2011; Labaree, Robert V. and Ross Scimeca. “The Philosophical Problem of Truth in Librarianship.” The Library Quarterly 78 (January 2008): 43-70; Maykut, Pamela S. Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophic and Practical Guide . Washington, DC: Falmer Press, 1994; McLaughlin, Hugh. "The Philosophy of Social Research." In Understanding Social Work Research . 2nd edition. (London: SAGE Publications Ltd., 2012), pp. 24-47; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Metaphysics Research Lab, CSLI, Stanford University, 2013.

Sequential Design

- The researcher has a limitless option when it comes to sample size and the sampling schedule.

- Due to the repetitive nature of this research design, minor changes and adjustments can be done during the initial parts of the study to correct and hone the research method.

- This is a useful design for exploratory studies.

- There is very little effort on the part of the researcher when performing this technique. It is generally not expensive, time consuming, or workforce intensive.

- Because the study is conducted serially, the results of one sample are known before the next sample is taken and analyzed. This provides opportunities for continuous improvement of sampling and methods of analysis.

- The sampling method is not representative of the entire population. The only possibility of approaching representativeness is when the researcher chooses to use a very large sample size significant enough to represent a significant portion of the entire population. In this case, moving on to study a second or more specific sample can be difficult.

- The design cannot be used to create conclusions and interpretations that pertain to an entire population because the sampling technique is not randomized. Generalizability from findings is, therefore, limited.

- Difficult to account for and interpret variation from one sample to another over time, particularly when using qualitative methods of data collection.

Betensky, Rebecca. Harvard University, Course Lecture Note slides; Bovaird, James A. and Kevin A. Kupzyk. "Sequential Design." In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 1347-1352; Cresswell, John W. Et al. “Advanced Mixed-Methods Research Designs.” In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research . Abbas Tashakkori and Charles Teddle, eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003), pp. 209-240; Henry, Gary T. "Sequential Sampling." In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods . Michael S. Lewis-Beck, Alan Bryman and Tim Futing Liao, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004), pp. 1027-1028; Nataliya V. Ivankova. “Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice.” Field Methods 18 (February 2006): 3-20; Bovaird, James A. and Kevin A. Kupzyk. “Sequential Design.” In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010; Sequential Analysis. Wikipedia.

Systematic Review

- A systematic review synthesizes the findings of multiple studies related to each other by incorporating strategies of analysis and interpretation intended to reduce biases and random errors.

- The application of critical exploration, evaluation, and synthesis methods separates insignificant, unsound, or redundant research from the most salient and relevant studies worthy of reflection.

- They can be use to identify, justify, and refine hypotheses, recognize and avoid hidden problems in prior studies, and explain data inconsistencies and conflicts in data.

- Systematic reviews can be used to help policy makers formulate evidence-based guidelines and regulations.

- The use of strict, explicit, and pre-determined methods of synthesis, when applied appropriately, provide reliable estimates about the effects of interventions, evaluations, and effects related to the overarching research problem investigated by each study under review.

- Systematic reviews illuminate where knowledge or thorough understanding of a research problem is lacking and, therefore, can then be used to guide future research.

- The accepted inclusion of unpublished studies [i.e., grey literature] ensures the broadest possible way to analyze and interpret research on a topic.

- Results of the synthesis can be generalized and the findings extrapolated into the general population with more validity than most other types of studies .

- Systematic reviews do not create new knowledge per se; they are a method for synthesizing existing studies about a research problem in order to gain new insights and determine gaps in the literature.

- The way researchers have carried out their investigations [e.g., the period of time covered, number of participants, sources of data analyzed, etc.] can make it difficult to effectively synthesize studies.

- The inclusion of unpublished studies can introduce bias into the review because they may not have undergone a rigorous peer-review process prior to publication. Examples may include conference presentations or proceedings, publications from government agencies, white papers, working papers, and internal documents from organizations, and doctoral dissertations and Master's theses.

Denyer, David and David Tranfield. "Producing a Systematic Review." In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods . David A. Buchanan and Alan Bryman, editors. ( Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2009), pp. 671-689; Foster, Margaret J. and Sarah T. Jewell, editors. Assembling the Pieces of a Systematic Review: A Guide for Librarians . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2017; Gough, David, Sandy Oliver, James Thomas, editors. Introduction to Systematic Reviews . 2nd edition. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2017; Gopalakrishnan, S. and P. Ganeshkumar. “Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis: Understanding the Best Evidence in Primary Healthcare.” Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2 (2013): 9-14; Gough, David, James Thomas, and Sandy Oliver. "Clarifying Differences between Review Designs and Methods." Systematic Reviews 1 (2012): 1-9; Khan, Khalid S., Regina Kunz, Jos Kleijnen, and Gerd Antes. “Five Steps to Conducting a Systematic Review.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 96 (2003): 118-121; Mulrow, C. D. “Systematic Reviews: Rationale for Systematic Reviews.” BMJ 309:597 (September 1994); O'Dwyer, Linda C., and Q. Eileen Wafford. "Addressing Challenges with Systematic Review Teams through Effective Communication: A Case Report." Journal of the Medical Library Association 109 (October 2021): 643-647; Okoli, Chitu, and Kira Schabram. "A Guide to Conducting a Systematic Literature Review of Information Systems Research." Sprouts: Working Papers on Information Systems 10 (2010); Siddaway, Andy P., Alex M. Wood, and Larry V. Hedges. "How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-analyses, and Meta-syntheses." Annual Review of Psychology 70 (2019): 747-770; Torgerson, Carole J. “Publication Bias: The Achilles’ Heel of Systematic Reviews?” British Journal of Educational Studies 54 (March 2006): 89-102; Torgerson, Carole. Systematic Reviews . New York: Continuum, 2003.

- << Previous: Purpose of Guide

- Next: Design Flaws to Avoid >>

- Last Updated: Oct 14, 2024 1:50 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Cross-Sectional Study | Definition, Uses & Examples

Cross-Sectional Study | Definition, Uses & Examples

Published on May 8, 2020 by Lauren Thomas . Revised on June 22, 2023.

A cross-sectional study is a type of research design in which you collect data from many different individuals at a single point in time. In cross-sectional research, you observe variables without influencing them.

Researchers in economics, psychology, medicine, epidemiology, and the other social sciences all make use of cross-sectional studies in their work. For example, epidemiologists who are interested in the current prevalence of a disease in a certain subset of the population might use a cross-sectional design to gather and analyze the relevant data.

Table of contents

Cross-sectional vs longitudinal studies, when to use a cross-sectional design, how to perform a cross-sectional study, advantages and disadvantages of cross-sectional studies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about cross-sectional studies.

The opposite of a cross-sectional study is a longitudinal study . While cross-sectional studies collect data from many subjects at a single point in time, longitudinal studies collect data repeatedly from the same subjects over time, often focusing on a smaller group of individuals that are connected by a common trait.

Both types are useful for answering different kinds of research questions . A cross-sectional study is a cheap and easy way to gather initial data and identify correlations that can then be investigated further in a longitudinal study.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

When you want to examine the prevalence of some outcome at a certain moment in time, a cross-sectional study is the best choice.

Sometimes a cross-sectional study is the best choice for practical reasons – for instance, if you only have the time or money to collect cross-sectional data, or if the only data you can find to answer your research question was gathered at a single point in time.

As cross-sectional studies are cheaper and less time-consuming than many other types of study, they allow you to easily collect data that can be used as a basis for further research.

Descriptive vs analytical studies

Cross-sectional studies can be used for both analytical and descriptive purposes:

- An analytical study tries to answer how or why a certain outcome might occur.

- A descriptive study only summarizes said outcome using descriptive statistics.

To implement a cross-sectional study, you can rely on data assembled by another source or collect your own. Governments often make cross-sectional datasets freely available online.

Prominent examples include the censuses of several countries like the US or France , which survey a cross-sectional snapshot of the country’s residents on important measures. International organizations like the World Health Organization or the World Bank also provide access to cross-sectional datasets on their websites.

However, these datasets are often aggregated to a regional level, which may prevent the investigation of certain research questions. You will also be restricted to whichever variables the original researchers decided to study.

If you want to choose the variables in your study and analyze your data on an individual level, you can collect your own data using research methods such as surveys . It’s important to carefully design your questions and choose your sample .

Like any research design , cross-sectional studies have various benefits and drawbacks.

- Because you only collect data at a single point in time, cross-sectional studies are relatively cheap and less time-consuming than other types of research.

- Cross-sectional studies allow you to collect data from a large pool of subjects and compare differences between groups.

- Cross-sectional studies capture a specific moment in time. National censuses, for instance, provide a snapshot of conditions in that country at that time.

Disadvantages

- It is difficult to establish cause-and-effect relationships using cross-sectional studies, since they only represent a one-time measurement of both the alleged cause and effect.

- Since cross-sectional studies only study a single moment in time, they cannot be used to analyze behavior over a period of time or establish long-term trends.

- The timing of the cross-sectional snapshot may be unrepresentative of behavior of the group as a whole. For instance, imagine you are looking at the impact of psychotherapy on an illness like depression. If the depressed individuals in your sample began therapy shortly before the data collection, then it might appear that therapy causes depression even if it is effective in the long term.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies are two different types of research design . In a cross-sectional study you collect data from a population at a specific point in time; in a longitudinal study you repeatedly collect data from the same sample over an extended period of time.

| Longitudinal study | Cross-sectional study |

|---|---|

| observations | Observations at a in time |

| Observes the multiple times | Observes (a “cross-section”) in the population |

| Follows in participants over time | Provides of society at a given point |

Cross-sectional studies are less expensive and time-consuming than many other types of study. They can provide useful insights into a population’s characteristics and identify correlations for further research.

Sometimes only cross-sectional data is available for analysis; other times your research question may only require a cross-sectional study to answer it.

Cross-sectional studies cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship or analyze behavior over a period of time. To investigate cause and effect, you need to do a longitudinal study or an experimental study .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Thomas, L. (2023, June 22). Cross-Sectional Study | Definition, Uses & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved October 17, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/cross-sectional-study/

Is this article helpful?

Lauren Thomas

Other students also liked, longitudinal study | definition, approaches & examples, correlational research | when & how to use, survey research | definition, examples & methods, what is your plagiarism score.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Types of Research Designs Compared | Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

When you start planning a research project, developing research questions and creating a research design , you will have to make various decisions about the type of research you want to do.

There are many ways to categorise different types of research. The words you use to describe your research depend on your discipline and field. In general, though, the form your research design takes will be shaped by:

- The type of knowledge you aim to produce

- The type of data you will collect and analyse

- The sampling methods , timescale, and location of the research

This article takes a look at some common distinctions made between different types of research and outlines the key differences between them.

Table of contents

Types of research aims, types of research data, types of sampling, timescale, and location.

The first thing to consider is what kind of knowledge your research aims to contribute.

| Type of research | What’s the difference? | What to consider |

|---|---|---|

| Basic vs applied | Basic research aims to , while applied research aims to . | Do you want to expand scientific understanding or solve a practical problem? |

| vs | Exploratory research aims to , while explanatory research aims to . | How much is already known about your research problem? Are you conducting initial research on a newly-identified issue, or seeking precise conclusions about an established issue? |

| aims to , while aims to . | Is there already some theory on your research problem that you can use to develop , or do you want to propose new theories based on your findings? |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

The next thing to consider is what type of data you will collect. Each kind of data is associated with a range of specific research methods and procedures.

| Type of research | What’s the difference? | What to consider |

|---|---|---|

| Primary vs secondary | Primary data is (e.g., through interviews or experiments), while secondary data (e.g., in government surveys or scientific publications). | How much data is already available on your topic? Do you want to collect original data or analyse existing data (e.g., through a )? |

| , while . | Is your research more concerned with measuring something or interpreting something? You can also create a research design that has elements of both. | |

| vs | Descriptive research gathers data , while experimental research . | Do you want to identify characteristics, patterns, and or test causal relationships between ? |

Finally, you have to consider three closely related questions: How will you select the subjects or participants of the research? When and how often will you collect data from your subjects? And where will the research take place?

| Type of research | What’s the difference? | What to consider |

|---|---|---|

| allows you to , while allows you to draw conclusions . | Do you want to produce knowledge that applies to many contexts or detailed knowledge about a specific context (e.g., in a )? | |

| vs | Cross-sectional studies , while longitudinal studies . | Is your research question focused on understanding the current situation or tracking changes over time? |

| Field vs laboratory | Field research takes place in , while laboratory research takes place in . | Do you want to find out how something occurs in the real world or draw firm conclusions about cause and effect? Laboratory experiments have higher but lower . |

| Fixed vs flexible | In a fixed research design the subjects, timescale and location are begins, while in a flexible design these aspects may . | Do you want to test hypotheses and establish generalisable facts, or explore concepts and develop understanding? For measuring, testing, and making generalisations, a fixed research design has higher . |

Choosing among all these different research types is part of the process of creating your research design , which determines exactly how the research will be conducted. But the type of research is only the first step: next, you have to make more concrete decisions about your research methods and the details of the study.

Read more about creating a research design

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Types of Research Designs Compared | Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 15 October 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/types-of-research-designs/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, sampling methods | types, techniques, & examples, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, between-subjects design | examples, pros & cons.

Comparing Types of Research Designs

- First Online: 10 November 2021

Cite this chapter

- Stefan Hunziker 3 &

- Michael Blankenagel 3

3752 Accesses

Every researcher chooses the research design that is best suited to generate the envisioned conclusions they like to draw. There are several types of research designs. Each is especially well suited to generate a specific type of conclusion. Commonly used research designs in business and management are design science, action research, single case, multiple case, cross-sectional, longitudinal, experimental and literature review research. The specific characteristics depicting these research design’s idiosyncrasies, differences, and fields of application of these research designs are gathered in a synopsis. Also, we pose questions that guide researchers to the research design, matching their objectives and personal preferences. This chapter also addresses the popular terms “triangulation” and “mixed methods” and puts them into the context of research design.