- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Research Methods in Sport

- Mark F. Smith - University of Lincoln, UK

- Description

Packed full of essential tools and tips, this second edition is your quick-start guide to undertaking research within real world of sport. Using clear, accessible language, Smith maps an easy-to-follow journey through the research process, drawing upon the most up-to-date evidence and resources to help you select the most appropriate research approach for your project. Throughout the book you will discover:

- Key points that highlight important definitions and theories;

- Reflection points to help you make connections between key concepts and your research;

- Learning activities to put your newfound knowledge into practice;

- Further reading to explore the wider context of sport research in the real world.

Featuring over thirty-five case studies of students’ and academics’ research in practice, this book is the perfect guide-by-your-side to have during your own sport research.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Students of sport often doubt the value of research. This book works to change that mindset. It explains what research is, how sports research is done, and shows how research in sport advances the discipline.

Needed something to bring Sports examples to my research methods class. some of the language is used differently than in the other textbook, which confused the students, but as a standalone it does not quite have enough detail. It is a very good introduction to use first.

Preview this book

For instructors, select a purchasing option, related products.

This title is also available on SAGE Knowledge , the ultimate social sciences online library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

- Kindle Store

- Kindle eBooks

- Education & Teaching

Promotions apply when you purchase

These promotions will be applied to this item:

Some promotions may be combined; others are not eligible to be combined with other offers. For details, please see the Terms & Conditions associated with these promotions.

- Highlight, take notes, and search in the book

- In this edition, page numbers are just like the physical edition

- Create digital flashcards instantly

Rent $38.48

Today through selected date:

Rental price is determined by end date.

Buy for others

Buying and sending ebooks to others.

- Select quantity

- Buy and send eBooks

- Recipients can read on any device

These ebooks can only be redeemed by recipients in the US. Redemption links and eBooks cannot be resold.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Research Methods for Sports Studies: Third Edition 3rd Edition, Kindle Edition

Research Methods for Sports Studies is a comprehensive, engaging and practical textbook that provides a complete grounding in both qualitative and quantitative research methods for the sports studies student. Leading the reader step-by-step through the entire research process, from identifying a research question and collecting and analyzing data to writing the research report, it is richly illustrated throughout with sport-related case-studies and examples from around the world.

Now in a fully revised, updated and expanded third edition, the book includes completely new chapters on using social media and conducting on-line research, as well as expanded coverage of key topics such as conducting a literature review, making the most of statistics, research ethics and presenting research.

Research Methods for Sports Studies is designed to be a complete and self-contained companion to any research methods course and contains a wealth of useful features, such as highlighted definitions of key terms, revision questions and practical research exercises. An expanded companion website offers additional material for students and instructors, including web links, multiple choice revision questions, an interactive glossary, PowerPoint slides and additional learning activities for use in and out of class. This is an essential read for any student undertaking a dissertation or research project as part of their studies in sport, exercise and related fields.

- ISBN-13 978-0415749336

- Edition 3rd

- Sticky notes On Kindle Scribe

- Publisher Routledge

- Publication date December 5, 2014

- Language English

- File size 2870 KB

- See all details

- Kindle (5th Generation)

- Kindle Keyboard

- Kindle (2nd Generation)

- Kindle (1st Generation)

- Kindle Paperwhite

- Kindle Paperwhite (5th Generation)

- Kindle Touch

- Kindle Voyage

- Kindle Oasis

- Kindle Scribe (1st Generation)

- Kindle Fire HDX 8.9''

- Kindle Fire HDX

- Kindle Fire HD (3rd Generation)

- Fire HDX 8.9 Tablet

- Fire HD 7 Tablet

- Fire HD 6 Tablet

- Kindle Fire HD 8.9"

- Kindle Fire HD(1st Generation)

- Kindle Fire(2nd Generation)

- Kindle Fire(1st Generation)

- Kindle for Windows 8

- Kindle for Windows Phone

- Kindle for BlackBerry

- Kindle for Android Phones

- Kindle for Android Tablets

- Kindle for iPhone

- Kindle for iPod Touch

- Kindle for iPad

- Kindle for Mac

- Kindle for PC

- Kindle Cloud Reader

Customers who bought this item also bought

Editorial Reviews

'Understanding the research process and the value of sport research should be a responsibility for all those engaged in the sport enterprise; academicians and practitioners alike. Ian Jones has provided a text that creates a common link between the two, so that researchers and sport practitioners can communicate in the theoretical and practical.'

Dr Ronald W. Quinn, Associate Professor, Department of Sport Studies, Xavier University, Cincinnati, USA

' Research Methods for Sports Studies is structured in an easy to follow, clearly written format providing a step-by-step roadmap for research. This is an essential text for students in how to do sport studies research. The supplementary resources will assist lecturers who are teaching sport studies research, and provide students with value adding learning resources.'

Professor Tracy Taylor, Business School Deputy Dean, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia

'Ian Jones has written a highly accessible introductory text for undergraduate sports students from a range of sport disciplines, who are about to embark on a substantial piece of research for the first time. Likewise, the book provides a structure by which lecturers and tutors can shape the delivery of research methods modules. The case study and supplementary material brings to life what can sometimes be a rather mundane endeavour.'

Dr Jimmy O'Gorman, Senior Lecturer in Sports Development, Edge Hill University, UK

About the Author

Ian Jones is the Associate Dean for Sport at Bournemouth University. His teaching and research interests focus upon the areas of sport behaviour, and research methodology for sport. He is the author of several research methods texts, and has published his research in a variety of journals

Product details

- ASIN : B00QMIEEP6

- Publisher : Routledge; 3rd edition (December 5, 2014)

- Publication date : December 5, 2014

- Language : English

- File size : 2870 KB

- Simultaneous device usage : Up to 4 simultaneous devices, per publisher limits

- Text-to-Speech : Enabled

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Not Enabled

- Word Wise : Enabled

- Sticky notes : On Kindle Scribe

- Print length : 365 pages

- #99 in Physical Education

- #145 in Sociology of Sports (Kindle Store)

- #219 in Sports & Entertainment Industry (Kindle Store)

About the author

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Entire Site

- Research & Funding

- Health Information

- About NIDDK

- Diabetes Overview

Healthy Living with Diabetes

- Español

On this page:

How can I plan what to eat or drink when I have diabetes?

How can physical activity help manage my diabetes, what can i do to reach or maintain a healthy weight, should i quit smoking, how can i take care of my mental health, clinical trials for healthy living with diabetes.

Healthy living is a way to manage diabetes . To have a healthy lifestyle, take steps now to plan healthy meals and snacks, do physical activities, get enough sleep, and quit smoking or using tobacco products.

Healthy living may help keep your body’s blood pressure , cholesterol , and blood glucose level, also called blood sugar level, in the range your primary health care professional recommends. Your primary health care professional may be a doctor, a physician assistant, or a nurse practitioner. Healthy living may also help prevent or delay health problems from diabetes that can affect your heart, kidneys, eyes, brain, and other parts of your body.

Making lifestyle changes can be hard, but starting with small changes and building from there may benefit your health. You may want to get help from family, loved ones, friends, and other trusted people in your community. You can also get information from your health care professionals.

What you choose to eat, how much you eat, and when you eat are parts of a meal plan. Having healthy foods and drinks can help keep your blood glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels in the ranges your health care professional recommends. If you have overweight or obesity, a healthy meal plan—along with regular physical activity, getting enough sleep, and other healthy behaviors—may help you reach and maintain a healthy weight. In some cases, health care professionals may also recommend diabetes medicines that may help you lose weight, or weight-loss surgery, also called metabolic and bariatric surgery.

Choose healthy foods and drinks

There is no right or wrong way to choose healthy foods and drinks that may help manage your diabetes. Healthy meal plans for people who have diabetes may include

- dairy or plant-based dairy products

- nonstarchy vegetables

- protein foods

- whole grains

Try to choose foods that include nutrients such as vitamins, calcium , fiber , and healthy fats . Also try to choose drinks with little or no added sugar , such as tap or bottled water, low-fat or non-fat milk, and unsweetened tea, coffee, or sparkling water.

Try to plan meals and snacks that have fewer

- foods high in saturated fat

- foods high in sodium, a mineral found in salt

- sugary foods , such as cookies and cakes, and sweet drinks, such as soda, juice, flavored coffee, and sports drinks

Your body turns carbohydrates , or carbs, from food into glucose, which can raise your blood glucose level. Some fruits, beans, and starchy vegetables—such as potatoes and corn—have more carbs than other foods. Keep carbs in mind when planning your meals.

You should also limit how much alcohol you drink. If you take insulin or certain diabetes medicines , drinking alcohol can make your blood glucose level drop too low, which is called hypoglycemia . If you do drink alcohol, be sure to eat food when you drink and remember to check your blood glucose level after drinking. Talk with your health care team about your alcohol-drinking habits.

Find the best times to eat or drink

Talk with your health care professional or health care team about when you should eat or drink. The best time to have meals and snacks may depend on

- what medicines you take for diabetes

- what your level of physical activity or your work schedule is

- whether you have other health conditions or diseases

Ask your health care team if you should eat before, during, or after physical activity. Some diabetes medicines, such as sulfonylureas or insulin, may make your blood glucose level drop too low during exercise or if you skip or delay a meal.

Plan how much to eat or drink

You may worry that having diabetes means giving up foods and drinks you enjoy. The good news is you can still have your favorite foods and drinks, but you might need to have them in smaller portions or enjoy them less often.

For people who have diabetes, carb counting and the plate method are two common ways to plan how much to eat or drink. Talk with your health care professional or health care team to find a method that works for you.

Carb counting

Carbohydrate counting , or carb counting, means planning and keeping track of the amount of carbs you eat and drink in each meal or snack. Not all people with diabetes need to count carbs. However, if you take insulin, counting carbs can help you know how much insulin to take.

Plate method

The plate method helps you control portion sizes without counting and measuring. This method divides a 9-inch plate into the following three sections to help you choose the types and amounts of foods to eat for each meal.

- Nonstarchy vegetables—such as leafy greens, peppers, carrots, or green beans—should make up half of your plate.

- Carb foods that are high in fiber—such as brown rice, whole grains, beans, or fruits—should make up one-quarter of your plate.

- Protein foods—such as lean meats, fish, dairy, or tofu or other soy products—should make up one quarter of your plate.

If you are not taking insulin, you may not need to count carbs when using the plate method.

Work with your health care team to create a meal plan that works for you. You may want to have a diabetes educator or a registered dietitian on your team. A registered dietitian can provide medical nutrition therapy , which includes counseling to help you create and follow a meal plan. Your health care team may be able to recommend other resources, such as a healthy lifestyle coach, to help you with making changes. Ask your health care team or your insurance company if your benefits include medical nutrition therapy or other diabetes care resources.

Talk with your health care professional before taking dietary supplements

There is no clear proof that specific foods, herbs, spices, or dietary supplements —such as vitamins or minerals—can help manage diabetes. Your health care professional may ask you to take vitamins or minerals if you can’t get enough from foods. Talk with your health care professional before you take any supplements, because some may cause side effects or affect how well your diabetes medicines work.

Research shows that regular physical activity helps people manage their diabetes and stay healthy. Benefits of physical activity may include

- lower blood glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels

- better heart health

- healthier weight

- better mood and sleep

- better balance and memory

Talk with your health care professional before starting a new physical activity or changing how much physical activity you do. They may suggest types of activities based on your ability, schedule, meal plan, interests, and diabetes medicines. Your health care professional may also tell you the best times of day to be active or what to do if your blood glucose level goes out of the range recommended for you.

Do different types of physical activity

People with diabetes can be active, even if they take insulin or use technology such as insulin pumps .

Try to do different kinds of activities . While being more active may have more health benefits, any physical activity is better than none. Start slowly with activities you enjoy. You may be able to change your level of effort and try other activities over time. Having a friend or family member join you may help you stick to your routine.

The physical activities you do may need to be different if you are age 65 or older , are pregnant , or have a disability or health condition . Physical activities may also need to be different for children and teens . Ask your health care professional or health care team about activities that are safe for you.

Aerobic activities

Aerobic activities make you breathe harder and make your heart beat faster. You can try walking, dancing, wheelchair rolling, or swimming. Most adults should try to get at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity each week. Aim to do 30 minutes a day on most days of the week. You don’t have to do all 30 minutes at one time. You can break up physical activity into small amounts during your day and still get the benefit. 1

Strength training or resistance training

Strength training or resistance training may make your muscles and bones stronger. You can try lifting weights or doing other exercises such as wall pushups or arm raises. Try to do this kind of training two times a week. 1

Balance and stretching activities

Balance and stretching activities may help you move better and have stronger muscles and bones. You may want to try standing on one leg or stretching your legs when sitting on the floor. Try to do these kinds of activities two or three times a week. 1

Some activities that need balance may be unsafe for people with nerve damage or vision problems caused by diabetes. Ask your health care professional or health care team about activities that are safe for you.

Stay safe during physical activity

Staying safe during physical activity is important. Here are some tips to keep in mind.

Drink liquids

Drinking liquids helps prevent dehydration , or the loss of too much water in your body. Drinking water is a way to stay hydrated. Sports drinks often have a lot of sugar and calories , and you don’t need them for most moderate physical activities.

Avoid low blood glucose

Check your blood glucose level before, during, and right after physical activity. Physical activity often lowers the level of glucose in your blood. Low blood glucose levels may last for hours or days after physical activity. You are most likely to have low blood glucose if you take insulin or some other diabetes medicines, such as sulfonylureas.

Ask your health care professional if you should take less insulin or eat carbs before, during, or after physical activity. Low blood glucose can be a serious medical emergency that must be treated right away. Take steps to protect yourself. You can learn how to treat low blood glucose , let other people know what to do if you need help, and use a medical alert bracelet.

Avoid high blood glucose and ketoacidosis

Taking less insulin before physical activity may help prevent low blood glucose, but it may also make you more likely to have high blood glucose. If your body does not have enough insulin, it can’t use glucose as a source of energy and will use fat instead. When your body uses fat for energy, your body makes chemicals called ketones .

High levels of ketones in your blood can lead to a condition called diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) . DKA is a medical emergency that should be treated right away. DKA is most common in people with type 1 diabetes . Occasionally, DKA may affect people with type 2 diabetes who have lost their ability to produce insulin. Ask your health care professional how much insulin you should take before physical activity, whether you need to test your urine for ketones, and what level of ketones is dangerous for you.

Take care of your feet

People with diabetes may have problems with their feet because high blood glucose levels can damage blood vessels and nerves. To help prevent foot problems, wear comfortable and supportive shoes and take care of your feet before, during, and after physical activity.

If you have diabetes, managing your weight may bring you several health benefits. Ask your health care professional or health care team if you are at a healthy weight or if you should try to lose weight.

If you are an adult with overweight or obesity, work with your health care team to create a weight-loss plan. Losing 5% to 7% of your current weight may help you prevent or improve some health problems and manage your blood glucose, cholesterol, and blood pressure levels. 2 If you are worried about your child’s weight and they have diabetes, talk with their health care professional before your child starts a new weight-loss plan.

You may be able to reach and maintain a healthy weight by

- following a healthy meal plan

- consuming fewer calories

- being physically active

- getting 7 to 8 hours of sleep each night 3

If you have type 2 diabetes, your health care professional may recommend diabetes medicines that may help you lose weight.

Online tools such as the Body Weight Planner may help you create eating and physical activity plans. You may want to talk with your health care professional about other options for managing your weight, including joining a weight-loss program that can provide helpful information, support, and behavioral or lifestyle counseling. These options may have a cost, so make sure to check the details of the programs.

Your health care professional may recommend weight-loss surgery if you aren’t able to reach a healthy weight with meal planning, physical activity, and taking diabetes medicines that help with weight loss.

If you are pregnant , trying to lose weight may not be healthy. However, you should ask your health care professional whether it makes sense to monitor or limit your weight gain during pregnancy.

Both diabetes and smoking —including using tobacco products and e-cigarettes—cause your blood vessels to narrow. Both diabetes and smoking increase your risk of having a heart attack or stroke , nerve damage , kidney disease , eye disease , or amputation . Secondhand smoke can also affect the health of your family or others who live with you.

If you smoke or use other tobacco products, stop. Ask for help . You don’t have to do it alone.

Feeling stressed, sad, or angry can be common for people with diabetes. Managing diabetes or learning to cope with new information about your health can be hard. People with chronic illnesses such as diabetes may develop anxiety or other mental health conditions .

Learn healthy ways to lower your stress , and ask for help from your health care team or a mental health professional. While it may be uncomfortable to talk about your feelings, finding a health care professional whom you trust and want to talk with may help you

- lower your feelings of stress, depression, or anxiety

- manage problems sleeping or remembering things

- see how diabetes affects your family, school, work, or financial situation

Ask your health care team for mental health resources for people with diabetes.

Sleeping too much or too little may raise your blood glucose levels. Your sleep habits may also affect your mental health and vice versa. People with diabetes and overweight or obesity can also have other health conditions that affect sleep, such as sleep apnea , which can raise your blood pressure and risk of heart disease.

NIDDK conducts and supports clinical trials in many diseases and conditions, including diabetes. The trials look to find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease and improve quality of life.

What are clinical trials for healthy living with diabetes?

Clinical trials—and other types of clinical studies —are part of medical research and involve people like you. When you volunteer to take part in a clinical study, you help health care professionals and researchers learn more about disease and improve health care for people in the future.

Researchers are studying many aspects of healthy living for people with diabetes, such as

- how changing when you eat may affect body weight and metabolism

- how less access to healthy foods may affect diabetes management, other health problems, and risk of dying

- whether low-carbohydrate meal plans can help lower blood glucose levels

- which diabetes medicines are more likely to help people lose weight

Find out if clinical trials are right for you .

Watch a video of NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers explaining the importance of participating in clinical trials.

What clinical trials for healthy living with diabetes are looking for participants?

You can view a filtered list of clinical studies on healthy living with diabetes that are federally funded, open, and recruiting at www.ClinicalTrials.gov . You can expand or narrow the list to include clinical studies from industry, universities, and individuals; however, the National Institutes of Health does not review these studies and cannot ensure they are safe for you. Always talk with your primary health care professional before you participate in a clinical study.

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

NIDDK would like to thank: Elizabeth M. Venditti, Ph.D., University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Identification and Identity: Differentiating the Conceptual terms

- Iryna RAYEVSKA Odessa I. I. Mechnikov National University

- Prof. Olena Matuzkova Odesa I.I. Mechnikov University

- Prof. Olga Grynko Odesa I.I. Mechnikov University

The problem of identity and identification has been occupying a prominent place in research studies since the early 20th century and is one of the most relevant issues in the science of the late 20 th - early 21 st centuries. It is determined by the changes in socio-cultural reality in the post-modern societies of the second half of the 20th century, the crisis in the existential approach to the personality studies, enhanced integrative trends in the scientific thinking, its humanitarianization and anthropocentric nature.

This research paper looks at the actualization of the studies on identity and identification, describes the history and scope of the identification studies, substantiates the differentiation between the terms of individual/collective identity and identification.

The subject of the article is the phenomenological and conceptual essence of identity and identification. The goal of the article is to substantiate identity and identification as the phenomena and scientific concepts. The methodological basis of the research includes the complex of the general research methods, namely: observation, description, induction and deduction, analysis and synthesis, taxonomy and modelling.

The differentiation of the investigated terms reduces to the fact that identification serves as a foundation for constructing identity, so they correlate as a mechanism, process, and result of such mechanism’s operation in an individual self-conscious. Identification is seen as a cognitive-and-emotional mechanism of identity construction, due to which the subject constructs his or her own sameness. Identity is a result of recognition and emotional assessment of the individual-and-group and collective characteristics by an individual or group. Such characteristics have been endorsed by the relevant others as a result of constructing the world image, the image of the collective, of individual's or group's self and their place in there, basing on the specific identifying features.

Author Biographies

Iryna rayevska, odessa i. i. mechnikov national university.

(PhD in Philology) is Associate Professor of the Translation Department at Odesa I. I. Mechnikov University, Odesa, Ukraine. Her areas of interest include general linguistics, sociolinguistics, dialectology, translation studies. Rayevska is the author of 1 collective monograph, 4 teaching aids and nearly 20 scientific articles. Recent publications: “Italian Language of Mass Media: Trends and New Challenges”, “Rendering of Italian Dialectisms in Translation”, “Rendering of Author Occasionalisms in Translation into the Ukrainian Language”, “Dialects in Advertisement Discourse: Example of Italy”, “Subdialect of Perugia in the System of Umbrian Dialects: Comprehensive Study and Analysis”.

Prof. Olena Matuzkova, Odesa I.I. Mechnikov University

(Dr. of Science in Philology) is a Full Professor, Professor of the Translation Department at Odesa I. I. Mechnikov University, Odesa, Ukraine. Her areas of interest include linguoculturology, cognitive discursology, identity linguistic studies, linguistics of translation. O. Matuzkova is the author of 1 monograph, 4 collective monographs, 17 teaching aids and nearly 130 scientific articles. Recent publications: “English Identity as Linguocultural Phenomenon: Cognitive-Discursive Aspect”, “On Content and Correlation of Concepts English Identity and British Identity ”, “Rendering of Odessa Realia in English Fiction and Non-Fiction Texts”, “Linguoculture as Synergy of Language, Culture and Mind”.

Prof. Olga Grynko, Odesa I.I. Mechnikov University

(PhD in Philology) is Associate Professor of the Translation Department at Odesa I. I. Mechnikov University, Odesa, Ukraine. Her areas of interest include cognitive linguistics, archetypal concepts, and translation studies. Grynko is the author of 1 collective monograph, 2 teaching aids, and nearly 20 scientific articles. Recent publications: “Archetypal Concepts of the Elements in W. Golding’s Prose Fiction”, “Foreign Words: On the Issue of Their Functioning and Translation”, “Rendering the Predicate of State in Translation from the English Language”, “Artionyms: Structure Features and Translation into English”.

Abushenko, V. L. (1998). Identichnost’ (Identity, in Russian). In A. A. Gritsanov (Ed.), Modern Philosophy Dictionary (pp. 400-404). Minsk: Publ. V.M. Skakun.

Aslet, C. (1997). Anyone for England? London: Little Brown.

Bauman, Z. (2010). Identity. Conversations with Benedetto Vecchi. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Boiko, V. V. (2008). Identyfikatsiia (Identification, in Ukrainian). In V. G. Gorodianko (Ed.), Sociological Encyclopaedia (p. 147). Kyiv: Akademvydav.

Erikson, E. H. (1996). Identichnost’: yunost’ i krizis (Identity, Youth and Crisis, in Russian). ?oscow: Publishing group “Progress”.

Golenkova, Z. T. (2000). Identifikatsiya sotsial’naya (Social Identification, in Russian). In V. N. Ivanov & G. Yu. Semigin (Eds.), Political Encyclopedia (pp. 415-416). ?oscow: Mysl.

Grishayeva, L. I. (2007). Osobennosi ispolzovaniya yazyka i kul’turnaya identichnost’ kommunikantov (Peculiarities of the Language Use and Cultural Identity of Communicants, in Russian). Voronezh: VGU.

Katanova, E. N. (2007). Nominativnye strategii pri oboznachenii subjekta samoidentifikatsii v samoidentifitsyruyuschem vyskasyvanii (Nominative Strategies of Nominating a Subject of Self-Identification in a Self-Identifying Utterance, in Russian). Language, Communication, and Social Environment, 7, 251-260.

Kravchenko, A. I., & Anurin V. F. (2006). Sotsiologiya: Uchebnik dlya vuzov (Sociology: A Textbook for Higher Education, in Russian). Saint-Petersburg: Peter.

Krysko, V. G. (2001). Sotsialnaya psikhologiya: slovar’-spravochnik (Social Psychology: A Reference Dictionary, in Russian). Minsk: Harvest, Moscow: AST.

Malakhov, Yu. S. (2004). Identichnost’ (Identity, in Russian). In A. A. Ivin (Ed.) Philosophy: Encyclopaedical Dictionary (pp. 299-300). Moscow: Gardariki.

Malakhov, Yu. S. (2011). Identichnost’ (Identity, in Russian). In V. S. Stenin (Ed.), New Encyclopedia of Philosophy (pp. 78-79). Moscow: Mysl.

Matuzkova, E. P. (2014). Identichnost i lingvokul’tura: metodologiya izucheniya: monografiya (Identity and Linguoculture: Research Methodology: monograph, in Russian). Odessa: Izdatalstvo KP OGT.

Mescheryakov, B. G., Zinchenko, V. P. (Eds.). (2007). Bol’shoi psikhologicheskii slovar’ (The Big Dictionary of Psychology, in Russian). Saint-Petersburg: Praim-EVROZNAK.

Mukhina, V. S. (2000). Vozrastnaya psikhologiya (Developmental Psychology, in Russian). Moscow: Akademia.

Naumenko, L. I. (2003). Identifikatsiya (Identification, in Russian). In A. A.Gritsanov (Ed.) Sociology: Encyclopedia (p. 344). Minsk: Interpressservis; Knizhnyi dom.

Petrovsky, A. V., & Yaroshevsky, M. G. (Eds.) (1985). Kratkii psikhologicheskii slovar’ (Concise Dictionary of Psychology, in Russian). Moscow: Politizdat.

Polezhayeva (2004). Problema, opredeleniya identifikatsii kak kategorii v mezhdistsyplinarnom znanii (The Problem, Definition of Identification as a Category of the Interdisciplinary Knowledge, in Russian). In The Materials of the Third International Scientific Conference “Human in the Contemporary Philosophical Concepts” (pp. 156-159). Volgograd: PRINT.

Polezhayeva (2006). Sotsialno-filisofskiy aspekt osmysleniya identifikatsii i nositeley identifikatsionnykh praktik (Sociophilosophic aspect of Comprehension of Identification and Bearers of Identification Practices, in Russian). In A.Nekhayev (Ed.) Omsk Scientific Bulletin (pp. 40-42). Omsk: OmGTU.

Scruton, R. (2006). England: An Elegy. London: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd.

Stenin, V. S. (Ed.). (2011). Novaya filosofskaya entsyklopediya (New Philosophy Dictionary, in Russian). Moscow: Mysl.

Zakovorotnaya, M. V. (1999). Identishnost’ cheloveka. Sotsialno-filosofskiye aspekty (Human Identity, Socio-Philosophic Aspects, in Russian). Rostov-on-Don: SKNTS VSHD.

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2021 Author and scientific journal WISDOM

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License .

Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC) . CC BY-NC allows users to copy and distribute the article, provided this is not done for commercial purposes. The users may adapt – remix, transform, and build upon the material giving appropriate credit, and providing a link to the license. The full details of the license are available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

Unveiling the hidden struggle of healthcare students as second victims through a systematic review

- José Joaquín Mira 1 , 2 ,

- Valerie Matarredona 1 ,

- Susanna Tella 3 ,

- Paulo Sousa 4 ,

- Vanessa Ribeiro Neves 5 ,

- Reinhard Strametz 6 &

- Adriana López-Pineda 2

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 378 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

203 Accesses

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

When healthcare students witness, engage in, or are involved in an adverse event, it often leads to a second victim experience, impacting their mental well-being and influencing their future professional practice. This study aimed to describe the efforts, methods, and outcomes of interventions to help students in healthcare disciplines cope with the emotional experience of being involved in or witnessing a mistake causing harm to a patient during their clerkships or training.

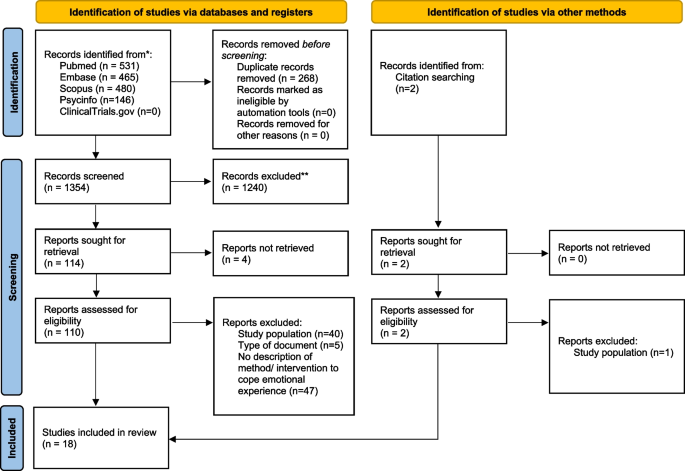

This systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines and includes the synthesis of eighteen studies, published in diverse languages from 2011 to 2023, identified from the databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, SCOPUS and APS PsycInfo. PICO method was used for constructing a research question and formulating eligibility criteria. The selection process was conducted through Rayyan. Titles and abstracts of were independently screened by two authors. The critical appraisal tools of the Joanna Briggs Institute was used to assess the risk of bias of the included studies.

A total of 1354 studies were retrieved, 18 met the eligibility criteria. Most studies were conducted in the USA. Various educational interventions along with learning how to prevent mistakes, and resilience training were described. In some cases, this experience contributed to the student personal growth. Psychological support in the aftermath of adverse events was scattered.

Ensuring healthcare students’ resilience should be a fundamental part of their training. Interventions to train them to address the second victim phenomenon during their clerkships are scarce, scattered, and do not yield conclusive results on identifying what is most effective and what is not.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Students in healthcare disciplines often witness or personally face stressful clinical events during their practical training [ 1 , 2 ], such as unexpected patient deaths, discussions with patients' families or among healthcare team members, violence toward professionals, or inappropriate treatment toward themselves. When this occurs, the majority of students talk to other students about it (approximately 90%), and less frequently, they speak to healthcare team members or mentors (37%) [ 2 ]. This is because they usually believe they will not receive attention, will not be understood, or fear negative consequences in their evaluation [ 1 , 2 ].

A particular case of a stressful clinical event is being involved in an adverse event (AE) or making an honest mistake [ 2 ] due to circumstances beyond the student's control. Approximately three-quarters of nursing or medical students witness some AE during their professional development (clerkships and training in healthcare centers) [ 2 , 3 ] and studies show that 18%-30% of students report committing an error resulting in an AE [ 4 , 5 ]. Some of them may even experience humiliation or verbal abuse for that error [ 6 ]. The vast majority (85%) of these occurrences lead to a second victim experience [ 7 , 8 ]. Consistent with what we know about the second victim experience [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], it is common for students in these cases to experience hypervigilance, acute stress, and doubts about their own ability for this work [ 12 , 13 ]. These emotional disturbances are usually more intense among females than males [ 14 ] and people with high values in the personality trait of neuroticism [ 15 , 16 ].

They also observe the impact of clinical errors on other healthcare professionals, influencing their response [ 3 ]. All these situations affect their well-being and can shape their future professional practice style [ 17 , 18 ]. For example, they may develop defensive practices more frequently [ 5 , 17 ] or avoid informing patients in the future after an AE [ 4 ]. Educators should not overlook the emotional effects of AEs on students/trainees [ 19 ]. Indeed, patient safety topics, including the second victim, mental well-being, and resilience, are neglected in undergraduate medical and nursing curricula in Europe. Furthermore, over half (56%) according to the responses from the students they did not ‘speak up' during a critical situation when they felt they could or should have [ 20 ].

Recently, psychological interventions to promote resilience in students facing stressful situations have been reviewed [ 21 ]. These interventions are not widely implemented, and approximately only one-fourth of students report having sufficient resilience training during their educational period [ 2 ]. In the specific case of supporting students who experience the second victim phenomenon, we lack information about the approach, scope, and method of possible interventions. The objective of this systematic review was to describe the efforts, methods, and outcomes of interventions to help students in healthcare disciplines cope with the emotional experience (second victim) of being involved in or witnessing a mistake causing harm to a patient during their clerkships or training.

The review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 22 ]. The study protocol was registered at PROSPERO (International prospective register of systematic reviews) [ 23 ] under the registration number CRD42023442014.

Eligibility criteria

The research question and eligibility criteria were constructed using the PICO method as follows (see Supplemental material 1 ):

Population: Students of healthcare disciplines

Intervention: Any method or intervention addressing the second victim phenomenon

Comparator: If applicable, any other method or intervention

Outcomes: Any measure of impact

Eligible studies included those reporting any method or intervention to prevent and address the second victim experience among healthcare students involved in or witnessing a mistake causing adverse events during their clerkships or training. Additionally, studies reporting interventions addressing psychological stress or reinforcing competences to face highly stressful situations, enhancing resilience, or increasing understanding of honest errors in the clinical setting were also included. Regarding the study population, eligible studies included healthcare discipline students (e.g., medical, nursing, pharmacy students) enrolled in any year, level, or course, both in public and private schools or faculties worldwide. All quantitative studies (experimental, quasi-experimental, case–control, cohort, and cross-sectional studies) within the scope of educational activities, as well as all qualitative studies (e.g., focus groups, interviews) conducted to explore intervention outcomes, were included.

The exclusion criteria were interventions and data regarding residents or professionals as trainees, analysis aimed at preparing the curriculum content or evaluating academic performance (including regarding patient safety issues), and any type of review study, editorials, letters to the editor, comments, or other noncitable articles (such as editorials, book reviews, gr ey literature, opinion articles or abstracts). Conference abstracts were included if they contained substantial and original information not found elsewhere.

The search was conducted on August 5, 2023, in the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, SCOPUS and APS PsycInfo. The reference lists of relevant reviews and other selected articles were explored further to find any additional appropriate articles. Last, recommended websites (gray literature) found during the comprehensive reading of publications were included if they met the inclusion criteria.

Controlled vocabulary and free text were combined using Boolean operators and filters to develop the search strategy (Supplemental Material 1 ). The terminology used in this study was extracted from the literature while respecting the most common usage of the terms prior to initiation of this screening. No limitations were imposed regarding language or the publication date.

Study selection

The selection process was conducted through Rayyan [ 24 ]. After removal of duplicates, two researchers (JM and VM) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved publications to determine eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved by an arbiter (AL), who made the final decision after debate to obtain consensus. Afterwards, screening of the full texts of the preselected articles was carried out in the same manner.

Data extraction

After final inclusion, the following characteristics of each study were collected by two reviewers: publication details (first author, year of publication), country of the study location, aim/s, study design, setting, type of study participants, and sample size. Separately, the following information of the included studies was collected: the description of methods, support programs or study interventions to address the second victim phenomenon, the findings on their effectiveness (competences and attitudes changed) and participants’ views or experience, if applicable, and whether a ‘second victim’ term was used.

Quality appraisal

We used the critical appraisal tools of the Joanna Briggs Institute [ 25 ] to assess the risk of bias of the included studies, according to the study design. Those studies that did not meet at least 60% of the criteria [ 26 ] were considered to have a high risk of bias. The critical appraisal was performed by two independent reviewers, and the overall result was expressed as a percentage of items answered with “yes”. Additionally, the number of citations of each article was collected as a quality measure [ 27 ].

Data synthesis

A descriptive narrative synthesis of the studies (approaches and outcomes) was conducted comparing the type and content of the methods or interventions implemented. Before initiating our literature search, we drafted a thematic framework informed by our research objectives, anticipating potential themes. This framework guided our evidence synthesis, dynamically adapting as we analyzed the included studies. Our approach allowed systematic integration of findings into coherent themes, ensuring our narrative synthesis was both grounded in evidence and reflective of our initial thematic expectations, providing a nuanced understanding of the topic within the existing research context. All data collected from the data extraction were reported and summarized in tables. The main findings were categorized into broad themes: (1) Are students informed about the phenomenon of second victims or how to act in case of making a mistake or witnessing a mistake? (2) What do students learn about an honest mistake, intentional errors, and key elements of safety culture? (3) What kind of support do students value and receive to manage the second victim phenomenon? (4) Strategies for supporting students in coping with the second victim phenomenon after making or witnessing a mistake. We considered the effectiveness (measurement of the achieved change in knowledge, skills, or attitudes) and meaningfulness (individual experience, viewpoints, convictions, and understandings of the participants) of each intervention or support program.

A total of 1622 titles were identified after the initial search. After removing duplicates, 1354 studies were screened. After the title, abstract and full text review, we identified and extracted information from 18 studies. The selection process is shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1 ).

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources

The articles included in this review are shown in Table 1 in alphabetical order of the first author, detailing the characteristics and overall result of the quality assessment (measured as the percentage of compliance with the JBI tool criteria) of each study. Most studies were conducted in the USA ( n = 7) [ 19 , 21 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ], followed by Korea ( n = 2) [ 33 , 34 ] and Australia ( n = 2) [ 35 , 36 ], and the rest were carried out in Denmark [ 37 ], China [ 38 ], Italy [ 39 ], the United Kingdom [ 40 ], Georgia [ 41 ], Brazil [ 42 ], and Canada [ 43 ] ( n = 1 each). The included studies cover a publication period that ranges from 2011 to 2023, with four of them being published in 2020. All these investigations were conducted within the academic setting, with the exception of one study, which took place in the Western Sydney Local Health District. Regarding the study participants, eleven studies were exclusively focused on medical students, six specifically targeted nursing students, and one included both medical and nursing students. In terms of study design, quasi-experimental ( n = 8), cross-sectional ( n = 2) and qualitative designs ( n = 6) were used, and two studies used a mixed-methods design.

Supplementary Tables 1 , 2 and 3 show the quality assessment of quasi-experimental, cross-sectional, and qualitative studies, respectively. Four of the included studies [ 19 , 28 , 41 , 44 ] did not meet at least 60% of items and were considered to have a high risk of bias. The five studies of highest quality [ 32 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 43 ] met 80% of the items. The study of Le et al. (2022) [ 30 ] did not have enough information to assess the risk of bias, as it was a conference abstract. The study cited the most is the Hanson et al. study, conducted in 2020 [ 35 ].

Table 2 shows educational interventions, support strategies and any method reported in the scientific literature to help healthcare students cope with the emotional experience (second victim) of being involved in or witnessing a mistake during their clerkships or training. Due to the heterogeneity of retrieved studies regarding the type of design, the intervention type and outcome measures, a statistical analysis of the dataset was not possible. Thus, the evidence was summarized in broad themes.

Are students informed about the phenomenon of second victims or how to act in case of making a mistake or witnessing a mistake?

Some authors focus on the identification and reporting of errors, assuming that this process helps to cope with the emotional experience after the safety incident. Their studies [ 19 , 33 , 34 , 41 , 44 ] reported information on trainings given to medical or nursing students based on how to disclose errors, without addressing the second victim phenomenon specifically. In 2011, Gillies et al. reported that a medical error apology intervention increased confidence in providing effective apologies and their comfort in disclosing errors to a faculty member or patient [ 41 ]. It included online content with interactive tasks, small-group tasks and discussion, a standardized patient interview, and anonymous feedback by peers on written apologies. In 2015, Roh et al. showed that understanding, attitudes, and sense of responsibility regarding patient safety improved after a three-day patient safety training. This study involved medical students who were instructed on error causes, error reporting, communication with patients and caregivers and other concepts of patient safety. They used interactive lectures with demonstrations, small group practices, role playing, and debriefing [ 34 ]. In 2019, Ryder et al. reported that an interactive Patient Safety Reporting Curriculum (PSRC) seems to improve attitudes toward medical errors and increase comfort with disclosing them [ 19 ]. This curriculum was developed to be integrated into the third-year internal medicine clerkship during an 8-week clinical experience. It aimed to enable students to identify medical errors and report them using a format similar to official reports. Students were instructed in the method of classifying AEs developed by Robert Wachter and James Reason's Swiss cheese model [ 12 , 45 ]. A 60-min session included demonstrating the system model of error through a focused case-based writing assignment and discussion. In 2019, Mohsin et al. showed that clinical error reporting increased after a 4-h workshop where in addition to other concepts, the importance of reporting errors was discussed [ 42 ]. Other authors [ 30 , 33 ] focused on students' ability to report these AEs with curricula and syllabi employing methods such as the use of standardized patients, facilitated reflection, feedback, and short didactics for summarization. These studies also reported that this type of education program seems to enhance students’ current knowledge [ 36 ] and abilities to disclose medical errors [ 30 , 33 ].

Only the educational intervention suggested by David et al. in 2020, based on the World Health Organization (WHO) Patient Safety Curriculum, addresses the consequences and effects of the second victim phenomenon [ 29 ]. A 3-h session that consisted of the presentation of an AE in the form of a video or narrative, a discussion of case studies in small groups, where students have the opportunity to share their personal experiences related to these situations, and a list of practical application measures such as conclusions, improved knowledge, application skills, and critical thinking of students.

What do students learn about honest and intentional errors and key elements of safety culture?

Most training for both medical and nursing students focuses on how to identify the occurrence of a medical error since students, when asked about it, show little confidence in their ability to recognize such errors because they are little exposed to clinical procedures during their learning, which makes it difficult for them to differentiate errors from normal practice. In addition to teaching them how to identify them, interventions have also focused on how to prevent these AEs before they happen, as well as how to talk about them once they occur [ 29 , 40 , 41 , 44 ]. None of the training mentioned in the studies included in this review incorporated education on honest or intentional errors. However, a patient safety curriculum for medical students designed by Roh et al. (2015) [ 34 ] and a medication safety science curriculum developed by Davis & Coviello (2020) [ 29 ] for nursing students were based on the WHO Patient Safety Curriculum [ 13 ], which includes key aspects such as patient safety awareness, effective communication, teamwork and collaboration, safety culture, and safe medication management.

What kind of support do students value and receive to manage the second victim phenomenon?

Students stated that the greatest support comes from their peers, followed by their mentors and, finally, their families and friends [ 32 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 42 , 43 ]. Most hospitals and some universities have support programs specifically tailored for such situations, offering psychological assistance [ 39 ]. However, as these are mostly voluntary aids, many students do not make use of them, and if they do, the support they receive is usually limited. Mousinho Tavares et al. (2022) found that the students did not know about the organizational support or protocols available to students who become second victims of patient safety incidents [ 42 ]. In 2020, in the USA, interactive sessions exploring the professional and personal effects of medical errors were designed to explain to medical students the support resources available to them [ 31 ].

Strategies for supporting students after making or witnessing a mistake

In 2019, Breslin et al. developed a 2.5-h seminar on resilience for fourth-year medical students (in the USA) consisting of an initial group discussion about the psychology of shame and the guilt responses that arise from medical error [ 28 ]. During this first group discussion, students had the opportunity to share their experiences related to these concepts encountered during their medical training. Following this, students formed small groups led by previously trained teachers to enhance their confidence in discussing shame and to further explore the topics covered in the group seminar. This training improved confidence in recognizing shame, distinguishing it from guilt, identifying shame reactions, and being willing to seek help from others. In 2020, Musunur et al. showed that an hour-long interactive group session for medical students in the USA increased awareness of available resources in coping with medical errors and self-reported confidence in detecting and coping with medical errors [ 31 ]. A 2022 Italian cross-sectional study on healthcare students and medical residents as second victims found no data on structured programs included in medical residency programs/specialization schools to support residents after the occurrence of an adverse event. The study also found that it might be interesting to design interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for this type of student, as the symptoms of second victims are similar to those of this disorder. Similarly, this study proposes a series of interventions that could be useful, such as psychological therapy, self-help programs, and even drug therapies, as they have been proven effective in treating PTSD [ 39 ].

Few training interventions exist to support healthcare students cope with emotional experiences of being involved in or witnessing a mistake causing harm to a patient during their clerkships. These interventions are scattered and not widely available. Additionally, there's uncertainty about their effectiveness.

In 2008, Martinez and Lo [ 3 ] highlighted that during students' studies, there are numerous missed opportunities to instruct them on how to respond to and learn from errors. This study seems to confirm this statement. Despite some positive published experiences, the provision of this type of training is limited. Deans, school directors, academic and clinical mentors, along with faculty members, have the opportunity to recognize the needs of their students, helping to prepare them for psychologically challenging situations. Such events occur frequently and are managed by professionals who rely on their own capacity for resilience. These sources of stress are not unknown to us, as they are a regular part of daily practice in healthcare settings. However, they do not always receive the necessary attention, and it is often assumed that they are addressed without difficulty [ 3 ].

Currently, we are aware that students also undergo the second victim experience [ 8 , 37 , 46 ], and it has been emphasized that this experience may impact their future professional careers and personal lives [ 39 ]. There is a wide diversity in training programs and local regulations regarding the activities that students in practice can undertake. Although there is a growing interest, the number of studies has increased since 2019, there are still many topics to address, and the extent of the experiences suggests that these are isolated initiatives without further development informed in other faculties or schools.

Over one-third of the studies have employed quasi-experimental designs with pre-post measures, although most studies have relied on qualitative methodologies to explore students' responses to specific issues [ 19 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 41 , 44 ]. These investigations do allow us to assert that we understand the problem, have quantified it, and have ideas to address it, but we lack a consensus-based and tested framework to ensure the capacity to confront these situations in the students. Moreover, similar to what occurs in the study of training in resilience or to face the second victim phenomenon in the case of healthcare workers [ 2 , 21 , 28 , 35 , 47 , 48 ], all of the studies have been focused on medical and nursing students. Other profiles (such as pharmacy or psychology students) have not been included until now.

The first study on the impact of unintended incidents on students in healthcare disciplines dates back to 2011. Patey et al. (in 2007) identified deficiencies in patient safety training among medical students and designed an additional training module alongside their educational program [ 6 ]. Other experiences have also focused on providing patient safety education [ 6 , 29 , 33 , 35 , 39 ].

The majority of studies included in this review focused on training students in providing information and apologies to patients who have experienced an AE (due to a clinical error). These studies have been conducted on every continent except Africa, and while they have different objectives, they share a similar focus: enhancing the skills to disclosure and altering defensive or concealment attitudes. Many students had difficulty speaking up about medical errors [ 49 ]. This fact poses a threat to patient safety. The early formative period is the optimal time to address this issue, provide skills, and overcome the traditional and natural barriers to discussing things that go wrong.

Students preparing for highly stressful situations in their future careers face a contrast between the interest in their readiness and the observed figures of clinical errors during practices. A 2010 study [ 37 ] in Denmark reported that practically all students (93% of 229) witnessed medical errors, with 62% contributing to them. In Belgium (thirteen years after), up to 85% of students witness mistakes [ 17 ], while US and Italy studies (2019–2022) showed lower figures. Among 282 American students, only 36% experienced AEs, and Italian nursing students reported up to 37% [ 4 , 8 , 10 ]. Students are witnessing 3.8 incidents every 10 days [ 48 ], although there are students who do not report witnessing any errors during their clinical placements, indicating difficulties with speaking up. Preparing students for emotional responses and reactions from their environment when an adverse event occurs seems necessary in light of these data.

Although the information is limited (a total of 125 students were involved), the data provided by Haglund et al. (in 2009) suggest that being involved in highly stressful situations contributes to reinforcing resilience and represents an opportunity for their personal growth [ 48 ]. Training to confront these stressful situations, including clinical errors, helps reduce reactive responses, although it does not guarantee maintaining the previous level of emotional well-being among students [ 21 ]. In this sense, the model proposed by Seys et al. [ 50 ], which defines 5 stages, with the first two focused on preventing second victim symptoms and ensuring self-care capacity (at the individual and team levels), could also be applied to the case of students and, by extension, to first-year residents to enhance their capacity to cope with an experience as a second victim.

AEs are often attributed to professional errors, perpetuating a blame culture in healthcare [ 51 ]. Students may adopt defensive attitudes, risking patient safety. Up to 47% [ 4 ] feel unprepared for assigned tasks, and 80% expect more support than received [ 39 ]. Emotional responses to EAs include fear, shame, anxiety, stress, loneliness, and moral distress [ 1 , 5 , 14 , 17 , 20 , 21 ],. Students face loss of psychological well-being, self-confidence, skills, job satisfaction, and high hypervigilance [ 10 , 13 , 17 ]. While distress diminishes over time, mistakes' impact may persist, especially if harm occurs [ 5 ]. Near misses can positively contribute to education, raising awareness. of patient safety [ 52 ]. Simulating situations using virtual reality enhances coping abilities and indirectly improves patient safety [ 53 ].

In spite of these data, students are typically not informed about the phenomenon of second victims or how to respond in the event of making or witnessing a mistake, including during their period of training in faculties and schools [ 54 ]. They express a desire for support from their workplace and believe that preparation for these situations should commence during their university education [ 4 ]. Students attribute errors to individual causes rather than factors beyond their control (considering them as intentional rather than honest mistakes). There have been instances of successful experiences demonstrating how this information can be effectively communicated and students can be equipped to deal with these stressful situations. Notably, there are training programs aimed at enhancing disclosure skills among medical and nursing students [ 33 , 36 ]. However, the dissemination of such educational packages in faculties and schools is currently limited. This study was unable to locate research where the concepts of honest or intentional errors were shared with students.

Support interventions for second victims should provide a distinct perspective on addressing safety issues, incorporating the principles of a just culture, and offering emotional support to healthcare professionals and teams, ultimately benefiting patients. These interventions have primarily been developed and implemented within hospital settings [ 55 ]. However, comprehensive studies are lacking, and experiences within schools and faculties, as well as extending support to students during their clinical placements, appear to be quite limited. Conversely, there exists a body of literature discussing the encounters of residents from various disciplines when they assume the role of second victims [ 38 ]. These experiences should be considered when designing support programs in schools and faculties. In fact, a recent study has described how students seem to cope with mistakes by separating the personal from the professional and seeking support from their social network [ 37 ]. Models such as SLIPPS (Shared Learning from Practice to Improve Patient Safety) is a tool for collecting learning events associated with patient safety from students or other implementers. This could prove beneficial in acquainting students with the concept of the second victim phenomenon. Interventions in progress to support residents when they become second victims from their early training years could be extended to faculties and schools to reduce the emotional impact of witnessing or being involved in a severe clinical error [ 56 ]. However, it is essential not to forget that healthcare professionals work in multidisciplinary teams, and resilience training for high-stress situations should, to align with the reality of everyday healthcare settings, encompass the response of the entire team, not just individual team members. Moreover, to date, cited studies have focused only on stages 1 and 2 at the individual level. However, we should not rule out the possibility that the other stages may need to be activated at any time to address students' needs.

Recently, Krogh et al. [ 37 ] summarized the main expectations that students have for dealing with errors in clinical practice, including more knowledge about contributing factors, strategies to tackle them, attention to learning needs and wishes for the future healthcare system. They have identified as trigger of the second victim syndrome the severity of patient-injury and that the AE be completely unexpected.

Implications for trainers & Health Policy

Collaboration among faculty, mentors, health disciplines students, and healthcare institutions is vital for promoting a learning culture that avoids blame, punishment, and shame and fear which will benefit the quality that patients received. This approach makes speak-up more straightforward, allowing continuous improvement in patient safety by installing a learning from errors culture. Ensuring safe practices requires close cooperation between the university and healthcare institutions [ 57 ]. Several practical implications of this study are summarized in Supplementary Table 4 .

Psychological traumatizing events such as life-threating events, needle sticks, dramatic deaths, violent and threatening situations, torpid patient evolution, resuscitations, complaints, suicidal tendencies, and harm to patients are in the daily bases of healthcare workers. Errors occur all too frequently in the daily work of healthcare professionals. It is not just a matter of doctors or nurses, but it affects all healthcare workers. Ensuring their resilience in these situations should be a fundamental part of their training. This can be achieved through simulation exercises within the context of clinical practices, as it should be one of the key educational objectives. Specifically, clinical mistakes often have a strong emotional impact on professionals, and it seems that students (future professionals) are not receiving the necessary training to cope with the realities of clinical practice. Furthermore, during their training period, they may be affected by witnessing the consequences of AEs experienced by patients, which can significantly influence how professionals approach their work (e.g., defensive practices) [ 58 ] and their overall experience (e.g., detachment) [ 59 ]. There are proposals for toolkits that have proven to be useful [ 31 , 60 ], and the data clearly indicate that educators should not delay further including educational content for their students to deal with errors and other highly stressful situations in healthcare practice [ 52 ]. Adapting measures within the academic environment and at healthcare facilities that host students in training programs is a task that we should no longer postpone.

Future research directions

Individual differences in reactions to stress can modulate the future performance of current students and condition their resilience capacity [ 61 ]. This aspect should be studied in more detail alongside gender bias regarding mistakes made by man and woman [ 62 ]. The student perception of psychological safety to speak openly with their mentors [ 63 ], is also a crucial aspect in this training phase. Additionally, their conceptualization of human fallibility [ 63 , 64 ] needs to be analyzed to identify the most appropriate educational contents.

Both witnessing errors with serious consequences and being involved in them can affect their subsequent professional development. Analyzing the impact of these incidents to prevent inappropriate defensive practices or dropouts requires greater attention. Future studies could link these experiences to attitudes towards incident reporting and open disclosure with patients.

Limitations of the study

This review was limited to publications available in selected databases and might be subject to publication bias. The selection of studies could have been biased by the search strategy (controlled using a very broad strategy) or by the databases selected (controlled by choosing the four most relevant databases). Despite employing a comprehensive search strategy, relevant studies not indexed in the chosen databases may have been omitted. In the case of three articles, access to the full text was not available. There were no language limitations since there was no restructuring of the search. On the other hand, selection bias was controlled because the review was carried out by independent parties and with a third party for discrepancies. Regarding the results, the included studies exhibited considerable variability in design, interventions, and outcomes. This heterogeneity reflects the diverse educational settings and methodologies employed to address the second victim phenomenon but limits the generalizability of findings. In addition, most of the studies were conducted in high-income countries, which may not reflect the experiences or interventions applicable in low- and middle-income settings.

In conclusion, students also undergo the second victim experience, which may impact their future professional careers and personal lives. Interventions aimed at training healthcare discipline students to address the emotional experience of being involved in or witnessing mistakes causing harm to patients during their clerkships are currently scarce, scattered, and do not yield conclusive results on their effectiveness. Furthermore, most studies have focused on medical and nursing students, neglecting other healthcare disciplines such as pharmacy or psychology.

Despite some positive experiences, the provision of this type of training remains limited. There is a need for greater attention in the academic and clinical settings to identify students' needs and adequately prepare them for psychologically traumatizing events that occur frequently attending complex patients.

Efforts to support students in dealing with witnessing errors and highly stressful situations in clinical practice are essential to ensure their resilience and well-being of the future generation of healthcare professionals and ensure patient safety.

Availability of data and materials

The authors verify that the data supporting the conclusions of this study can be found in the article and its supplementary materials. However, data regarding the quality assessment process can be obtained from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Guo L, et al. Impact of unacceptable behavior between healthcare workers on clinical performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31(9):679–87. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2021-013955 .

Article Google Scholar

Houpy JC, Lee WW, Woodruff JN, Pincavage AT. Medical student resilience and stressful clinical events during clinical training. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1320187. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2017.1320187 .

Martinez W, Lo B. Medical students’ experiences with medical errors: an analysis of medical student essays. Med Educ. 2008;42(7):733–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03109.x .

Kiesewetter J, et al. German undergraduate medical students’ attitudes and needs regarding medical errors and patient safety–a national survey in Germany. Med Teach. 2014;36:505–10. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2014.891008 .

Panella M, et al. The determinants of defensive medicine in Italian hospitals: The impact of being a second victim. Rev Calid Asist. 2016;31(Suppl. 2):20–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cali.2016.04.010 .

Patey R, et al. Patient safety: helping medical students understand error in healthcare. Qual Saf Healthcare. 2007;16:256–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2006.021014 .

Strametz R, et al. Prevalence of second victims, risk factors and support strategies among young German physicians in internal medicine (SeViD-I survey). J Occup Med Toxicol. 2021;16:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-021-00300-8 .

Van Slambrouck L, et al. Second victims among baccalaureate nursing students in the aftermath of a patient safety incident: An exploratory cross-sectional study. J Prof Nurs. 2021;37:765–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.04.010 .

Mira JJ, et al. A Spanish-language patient safety questionnaire to measure medical and nursing students’ attitudes and knowledge. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2015;38:110–9.

Google Scholar

Mira JJ, et al. Lessons learned for reducing the negative impact of adverse events on patients, health professionals and healthcare organizations. Int J Qual Healthcare. 2017;29:450–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzx056 .

Vanhaecht K, et al. An Evidence and Consensus-Based Definition of Second Victim: A Strategic Topic in Healthcare Quality, Patient Safety, Person-Centeredness and Human Resource Management. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(24):16869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416869 .

Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):768–70. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768 . Disponible en.

World Health Organization. Patient safety curriculum guide: multiprofessional edition. News. 2011. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241501958 (accessed 16 Nov 2023).

Seys D, et al. Supporting involved healthcare professionals (second victims) following an adverse health event: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:678–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.07.006 .

Marung H, et al. Second Victims among German Emergency Medical Services Physicians (SeViD-III-Study). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:4267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054267 .

Potura E, et al. Second Victims among Austrian Pediatricians (SeViD-A1 Study). Healthcare. 2023;11(18):2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182501 .

Liukka M. Action after Adverse Events in Healthcare: An Integrative Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4717. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134717 .

Ratanawongsa NT, Hauer AHE. Third Year Medical Students’ Experiences with Dying Patients during the Internal Medicine Clerkship: A Qualitative study of the Informal Curriculum. Acad Med. 2005;80(7):641–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200507000-00006 .

Ryder HF, et al. What Do I Do When Something Goes Wrong? Teaching Medical Students to Identify, Understand, and Engage in Reporting Medical Errors. Acad Med. 2019;94:1910–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000002872 .