The Bruin Post

The Student News Site of Mountain View High School

- April 15 The Impact of Visual Arts Classes in High School

- March 4 Boys basketball is playoff-bound

- February 27 The video production 2 class is making a short film

- February 27 Multicultural week at Mountain View

- February 12 Teacher Spotlight: Mr. Green

- February 7 Native Americans have a voice and they deserve to be heard

- January 18 A farewell to our Golf seniors

- January 18 The stigma surrounding teenagers' mental health

- January 16 Teacher Spotlight: Ms. Lant

- January 16 GSA: what is it and why is it important?

Why more people should learn American Sign Language

Caitlin Wilkinson | April 19, 2022

Why should American Sign Language (ASL) be the next language to learn? ASL is arguably the most important language out there. ASL is necessary to know and understand, and here are some reasons. People who sign and or deaf people should be able to communicate with others. It’s good for expressing how you feel, and it’s a beautiful language. You don’t have to speak/pronounce things. We should be more involved/aware of the deaf and hard of hearing community. I can list on and on and on, but I won’t. That would take too much time… Imagine being in a world where there are people all around you, and you can’t even communicate with most of them. You don’t speak their language, and they are too impatient to slow down and try to communicate with you. I’ve seen and experienced that before, and it’s definitely not fun. I know I’m not the only one who has experienced it. If you have experienced it, then you know how it feels. It makes you feel lonely, frustrated, and many other feelings. Last year, in my ASL class, I had to be deaf for a day for the end-of-term project. I would have to wear earplugs and not speak for 24 hours. I wanted to make it a bit of a challenge, so I went to school during it. I wrote a sign to let everyone know that I couldn’t talk or hear. As soon as I showed the sign to someone, I noticed that they would give up on talking to me that day. It definitely was an adjustment. I wasn’t used to not hearing anyone. I couldn’t even hear the teachers talking. That might sound great at first, but it was way less great after being handed an assignment that I didn’t hear. I definitely wish that more people knew sign language or made an effort to learn it. Once, I was at a fast-food restaurant with my siblings; the customers in front of me were deaf. They were trying to order their food, and the person taking their order was getting really impatient with them. They would point at the menu, try to say some words, and sign to the guy taking their order. He said that he couldn’t help them so he left them there. The two customers ended up leaving without getting food. I didn’t know sign language at the time, so I couldn’t help them. I felt helpless, and after that, I knew that one day I would learn ASL and help others with it. Another reason to learn ASL (If the first reason wasn’t good enough for you) is that it’s a great way to express yourself. Dominique Lozano’s article “ Self Expression ” talks about how people express themselves. The way you express yourself makes you who you are. Sign language is a really expressive language. I love ASL. I love signing because I can show my emotions through my body. I feel way more connected and in tune with my feelings when I sign. In my ASL class, I have this term project that I’m doing. I’m making an ASL music video. The song my partner and I chose is “Waving Through a Window” from Dear Evan Hansen Broadway Musical. The lyrics come alive when I sign them. I can have the character Evan Hansen come alive. The emotion truly flows through the words I’m signing. Do you know what else I love about ASL? I LOVE how you don’t have to speak. I’m definitely more on the introverted side, and I always struggle with talking to people. ASL has been great in helping me with my social anxiety. I don’t know why, but it’s way less scary to use sign language than to speak. Whenever I would try to learn a new language, I would always hate the speaking/pronouncing words portion of learning it. With ASL, speaking isn’t needed. That’s probably one of my favorite things about sign language. Have I convinced you that ASL is the best language yet? Yes? No? Well, here is one more reason why you should learn it. It is essential to be involved and aware of the deaf and hard of hearing community. We must spread deaf awareness to bridge the gap between hearing and deaf people. We shouldn’t let a language barrier get in the way. There are so many great people out there that you might miss out on. Even if you learn a couple words, or at the very least learn the alphabet, that would make a difference. It may not seem like a big deal, but it really is. When I was doing the deaf for a day project, I had that sign saying that I couldn’t hear and speak. When I got on the bus to school, I sat down next to this girl Olivia like I usually did. I showed her the sign, and then she started fingerspelling to me out of nowhere! I was caught off guard because I wasn’t expecting that at all. It was incredible how she tried her best to communicate with me! It was probably the highlight of my day. Now, that was me, and I’m not even deaf. I did that for one day. That meant a lot to me. I can’t imagine what it might mean to someone who deals with this every day. This shows that learning something small like the alphabet can make a big difference in someone’s day. That’s just my experience. There are a lot of different kinds of stories out there. Learning ASL is so important, and doing this will bring us a few steps closer to Unity. With Unity, there is a great strength. ASL is a beautiful language, and I’m so glad that I have the opportunity to learn it.

The stigma surrounding teenagers’ mental health

Veterans day at Mountain View and in our Community

Christmas in November?

National Honor Society: Why it’s Worth Coming

Period product dispensers remain empty

A four day weekend for students, a work day for teachers!

Opinion: Teen dating

Let us appreaciate our local bus drivers

‘Puss in Boots: The Last Wish’ review (Spoliers)

Indian Child Welfare Act must stay for the well being of the children

Comments (2)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Angelina • Aug 30, 2022 at 12:58 PM

I believe we should all learn this too.

Mario Pena • May 6, 2022 at 1:01 PM

Yes, I believe we should all learn this language because it can be helpful so everyone can communicate with eachother.

- Arts and Entertainment

The Wrangler

Should Sign Language Be Taught At Schools?

Katelyn Ruggles

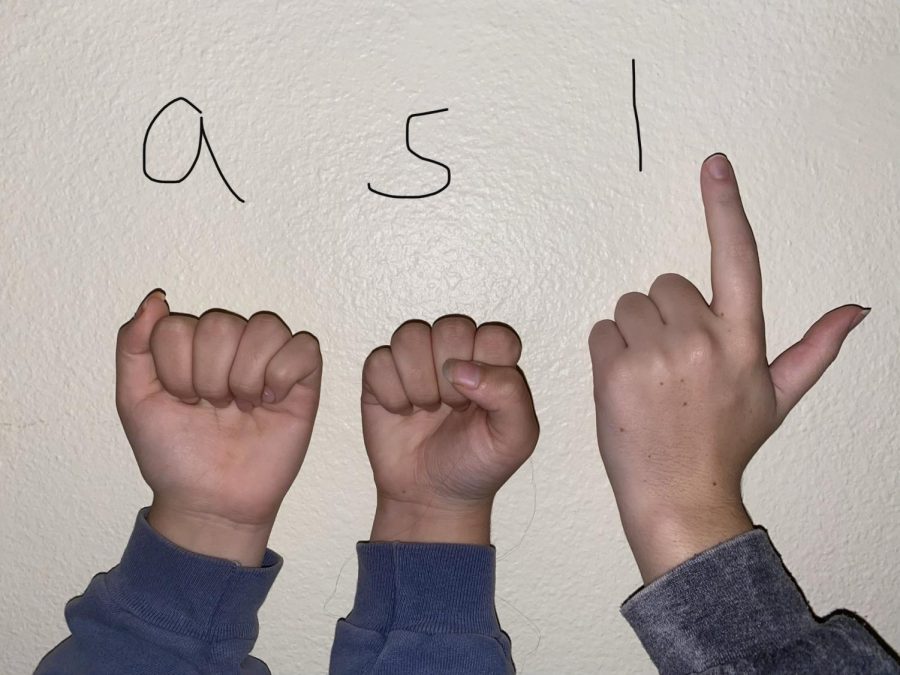

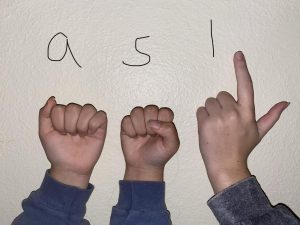

These are the letters a, s, and l in sign language, which stand for American Sign Language

Katelyn Ruggles , Photojournalist November 13, 2020

At almost every high school you go to, they always offer the basic languages to learn, commonly ranging from French to Spanish to German. However, one of the most common languages that are not taught in school is not a speaking language, but the language of the unspoken. Sign language is a popular and important language that many people across the world use to communicate, however, it is rarely offered to learn in schools. Here are several reasons why sign language is a valuable language to know, and therefore should be offered as a language to learn.

Considering the number of people in the world that use sign language as communication, it should be important enough and qualified enough to be taught in schools. About 70 million people use sign language worldwide, and of that number, 13% are teenagers over the age of 12 (usahearingcenters.com). Offering sign language in school can allow students and teachers to communicate with their peers that are hearing impaired, and allow them to have an easier and smoother time communicating with others. While explaining her classes, Jenna Roncevich (10) states how she “wanted to learn sign language instead of the languages at the school, but she could not because it was not offered.” It can also provide more job opportunities for teachers that can teach sign language, which can overall help with the economy and unemployment rates.

Not only can sign language be beneficial during school, but it is also a skill that can be useful to know in the future. Having the ability to speak sign language on your resume is a unique feature that can make you stand out amongst others. Many jobs ranging from receptionists in offices to hostesses in restaurants can find sign language a valuable asset to have on a resume as coming across deaf guests who mainly use sign language as communication can be common. Teaching sign language in schools can increase the chances of someone getting a job or into a certain school, just like any other subject taught in schools.

Sign language being offered in schools can also help with socializing and interaction in school. Kids will be able to interact with each other in a new and different way, and can also reach out and interact with kids who are hearing impaired. It is also sensitive to kids with special needs that cannot communicate efficiently using words. Unfortunately, in most schools, kids with special needs are commonly looked over by the other students and do not interact with kids as normally as other students do. Teaching sign language can increase the number of students that reach out and talk to the students with special needs, which can immensely improve these students’ high school experiences and lives.

With the increase of sensitivity to special needs and hearing-impaired students, along with the ability to better interact and communicate with students, sign language should be a given to be taught in high school. Not only can this help with including all students at school, but it can also make many of these students’ lives much better, and their high school days go much smoother. But the benefits do not stop there. Sign language also can be a unique skill to have on resumes, increasing the chances of people getting jobs or getting into schools. Obviously, with the numerous pros, sign language is a valuable asset to have in life that should be more commonly known worldwide, which should start at schools by offering it to be taught as a language option for students to take.

Katelyn Ruggles is an upcoming senior at Yorba Linda High School. She is on the board of Political Social Activist club and enjoys giving back to her community....

- Polls Archive

How a Young Baker’s Dreams and Perseverance Gave Her the Recipe for Success • 92984 Views

Discover Your Perfect Palette: Dressing to Compliment Your Eye Color! • 55427 Views

The Pros and Cons of Each UC School • 37548 Views

Are You A Mirrorball, This is me trying, Goldrush, or Archer? • 31492 Views

Should Sign Language Be Taught At Schools? • 30923 Views

Should Parents Choose What Career Path Their Child Takes? • 25496 Views

Truth Behind Eating While Studying • 23642 Views

Why do We Stand, or not Stand, for the Pledge of Allegiance? • 20876 Views

Positive and Negative of Aspects of Amusement Parks • 19350 Views

The Importance of Reading From a Variety of News Sources • 16072 Views

Pros and Cons of Rushing a Sorority/Fraternity

Prom Trends!

Solving Senioritis

My Favorite High Protein Snacks

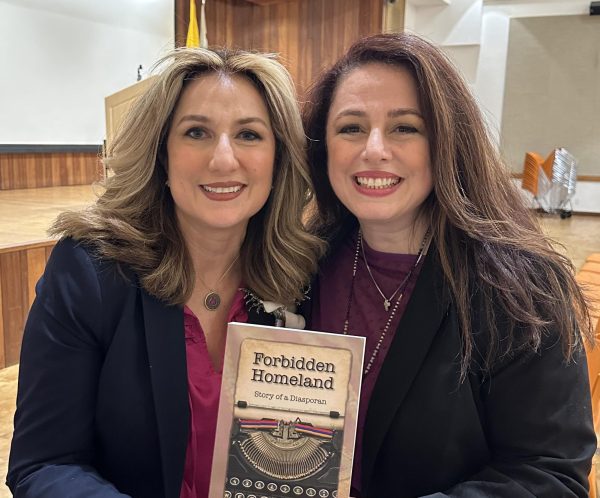

“Forbidden Homeland: Story of a Diasporan” Book Review

Spoiler Free Review of Dune Part Two

Winter Formal 2024 Review

Why do People Dislike Taylor Swift?

Diversifying Media: The Art of Inclusive Representation

The Importance of Water Safety

The #1 student news site of Yorba Linda High School

Comments (8)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Sharon Sun • May 15, 2021 at 4:16 PM

I also agree that ASL should be opened as an option for a language, especially considering that it still is a separate language that requires learning how to translate. I think it would be a great step to start being inclusive towards others!

Hayden MacDonald • Dec 10, 2020 at 8:35 PM

I wanted to take Sign Language and was very disappointed myself when hearing it was not offered at Yorba Linda. I think it is super important to be as inclusive as possible, and I believe this class is a big step in the right direction!

Blake Kingsbury • Dec 10, 2020 at 8:39 AM

Sign language is such a good thing to learn for communicating with those who need to use it. I absolutely support it being taught at schools!

faith desio • Nov 18, 2020 at 9:00 PM

I loved reading this article! Learning sign language has been a personal goal of mine for a long time. I think introducing it into the school system would be great, I know I would definitely take that class. Amazing article Katelyn!

Kylie de Best • Nov 18, 2020 at 7:12 PM

I love that you wrote this article! I feel that it is something very important to be offered at schools, and it is also seems a lot of fun to learn,

Fiona Salisbury • Nov 16, 2020 at 7:40 PM

I agree with you and I also believe that sign language should be taught in school as a class, and even if the school could not offer a class, I think it would be great if students were at least taught basic sign language.

Anita Tun • Nov 16, 2020 at 10:04 AM

I think it’s also important that more high schools should introduce asl which would be so useful communicating with others!

danielle huizar • Nov 15, 2020 at 3:13 PM

I loved this article and how it shows the reasons why sign language should be taught at schools. I personally want to learn sign language, and I would’ve loved to take it as a language in high school.

Advertisement

The moral case for sign language education

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 23 November 2019

- Volume 37 , pages 94–110, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Hilary Bowman-Smart ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2142-9696 1 , 2 ,

- Christopher Gyngell 1 , 2 ,

- Angela Morgan 3 , 4 &

- Julian Savulescu 1 , 5

35k Accesses

7 Citations

45 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Here, a moral case is presented as to why sign languages such as Auslan should be made compulsory in general school curricula. Firstly, there are significant benefits that accrue to individuals from learning sign language. Secondly, sign language education is a matter of justice; the normalisation of sign language education and use would particularly benefit marginalised groups, such as those living with a communication disability. Finally, the integration of sign languages into the curricula would enable the flourishing of Deaf culture and go some way to resolving the tensions that have arisen from the promotion of oralist education facilitated by technologies such as cochlear implants. There are important reasons to further pursue policy proposals regarding the prioritisation of sign language in school curricula.

Similar content being viewed by others

Assistive technology for the inclusion of students with disabilities: a systematic review

Intersectionality: A pathway towards inclusive education?

Does spelling instruction make students better spellers, readers, and writers? A meta-analytic review

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Learning another language is a life goal for many. We generally think that doing so is a form of self-improvement. We teach languages in our schools. Many people go out of their way to ensure that their child becomes bi- or multilingual. However, it is important to ask exactly why we choose certain languages above others, and which languages we should teach our children. The answer depends on assessing not just what is good for the individual child, but also what makes society better.

Languages taught in schools in English-speaking countries are often European or Asian languages. In Australia, Japanese, Italian, French, Indonesian, German and Chinese constitute 93% of enrolment numbers (Orton 2016 ). In both the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK), Spanish, French and German dominate (American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages 2011 ; Long and Bolton 2016 ). One set of languages that receives comparatively little attention are sign languages such as Australian Sign Language (Auslan), British Sign Language (BSL) and American Sign Language (ASL).

In December 2016 the first Australian national curriculum for Auslan was launched, as a result of much lobbying from the deaf (or Deaf) community (Dalzell 2016 ). This means there is a standard text for teaching Auslan that can be implemented around the country. Despite this, Auslan is still only taught in 4% of all Victorian public schools (Hore 2017 ). A recent push has occurred in the UK for BSL to be made available as a GCSE subject, with one child mounting a legal challenge in 2018 (Busby 2018 ). A 2017 petition to the government calling for BSL to be integrated into the national curriculum received over 35,000 signatures (“Make British Sign Language part of the National Curriculum” 2018 ). A 2017 survey by the National Deaf Children’s Society found that 92% of young people (both deaf and hearing) thought BSL should be taught in schools (National Deaf Children’s Society 2017 ). In the US, the provision of ASL in secondary schools is increasing, although it remains a very small minority of foreign language enrolments; teachers generally rely on a number of commercially-prepared curricula (Rosen 2010 ).

Here, we argue that sign languages should be compulsorily integrated into the school curriculum, whether primary, secondary, or both. This would make sign language education accessible to both hearing and deaf or hard-of-hearing students. We will focus on English-speaking countries as examples, particularly Australia (with Auslan) and the UK (with BSL). In these two countries in particular, sign language education has been the matter of recent public debate. We do not propose a specific educational policy, but rather a moral case as to why sign languages should be prioritised in any approach to developing a school curriculum.

Although the strong version of our claim is that sign language should be made compulsory, we accept that there may be some situations and contexts where this may not be appropriate or possible. In these exceptions, we still argue that sign language education should at least be made accessible, prioritised, and/or incentivised.

Teaching a second language has many cognitive and social benefits. Teaching sign language, specifically, has further benefits. Firstly, learning sign language would benefit individual students, as it would improve each student’s overall communication skills and provide additional cognitive advantages that come from being bimodally bilingual. Secondly and critically, widespread knowledge of sign language would benefit numerous groups who are already disadvantaged, such as those with a communication disability, particularly those who are congenitally deaf or hard-of-hearing. These individuals are at risk for social isolation, stigmatisation, loss of independence, poorer literacy and academic outcomes, underemployment, and overrepresentation in the juvenile justice system (Bryan et al. 2010 ; Health Workforce Australia 2014 ; Law et al. 2009 ; Schoon et al. 2010 ; Snow and Powell 2007 ). This makes sign language education a question of justice. Thirdly, teaching sign language in schools will go some way to resolving the tension around new technologies and the erasure of Deaf culture.

We set out our case as follows. In Sect. 2 , we outline the benefits that learning sign language bestows on individuals. In Sect. 3 , we argue that considerations of justice favour prioritising the teaching of sign language over other second languages. In Sect. 4 , we discuss issues regarding identity and deaf culture. We conclude by endorsing the general principle that in a default curriculum, students should learn sign language. At the very least, sign languages should be much more widely taught than they are now, so that they are among the most widely taught languages.

2 Benefits to the individual

Learning a second language has a number of demonstrated benefits to the individual. It can foster analytic thinking (Jiang et al. 2016 ), enhance multitasking (Poarch and Bialystok 2015 ), and improve social cognition and executive control (Bialystok and Craik 2010 ; Carlson and Meltzoff 2008 ; Colzato et al. 2008 ; Cox et al. 2016 ; Hilchey and Klein 2011 ) among a number of other cognitive benefits. These benefits are most evident when the second language is supported with strong bilingual education rather than only speaking the language at home (Lauchlan et al. 2012 ). Numerous studies have indicated that bilingualism serves as protection against cognitive decline in older age, delaying the onset of dementia by 4 to 5 years (Alladi et al. 2013 ; Perani et al. 2017 ; Woumans et al. 2015 ). With this level of protection against age-related disease, language education could even be argued to be a kind of public health measure. Additionally, there is the simple positive aspect of being able to communicate directly with a larger number of people than one otherwise would be able to. This also means the opportunity to engage with other cultures to a deeper level.

Learning a sign language provides additional benefits, as not only does it make a person bilingual, but also bimodal. It provides several cognitive gains: it improves the use of co-gesture in speech (Casey et al. 2012 ), improves the ability to identify facial expressions (Bettger et al. 1997 ), enhances vocabulary development and literacy in young children (Daniels 1994 , 2004 ; Moses et al. 2015 ), and improves spatial cognition such as mental rotation (Emmorey et al. 1993 , 1998 ; Romero Lauro et al. 2014 ; Talbot and Haude 1993 ). Bimodal bilinguals can co-activate both languages during spoken comprehension (Shook and Marian 2012 ) and there is no cost to simultaneous speech and sign (Emmorey et al. 2016 ). Uniquely, sign language allows for simultaneous communication in two modalities; this is not possible with two oral languages.

There are additional social benefits to learning sign language. For example, it allows people to communicate in very noisy environments (such as a crowded bar or factory) or in an unobtrusive fashion where noise may not be allowed or may be distracting (such as the classroom). It facilitates effective communication with members of the deaf community who do not communicate orally, without the need of an interpreter or assistive device (including pen and paper). This can have advantages in both the personal and professional realm (for example, by making a business more accessible to deaf or hard-of-hearing people, thereby potentially increasing profit).

Gestures and visual communication are already an integral part of communication, with co-gestures representing an important visual modality that accompanies verbal output (Perniss et al. 2015 ). Sign language further provides another modality beyond the verbal to express oneself. A large part of communication is non-verbal, and the use of sign language integrates, formalises and expresses this non-verbal communication in an effective way. The strong link between sign language and emotional expression (Elliott and Jacobs 2013 ) may prove to be a positive outlet for some.

Learning sign language will also provide additional benefits to those who may become deaf. Hearing loss is associated with age (Oh et al. 2014 ). Australia’s population is ageing, and the proportion of Australians who are 65 or older is expected to continue to grow, projected to reach a quarter of the population by the end of this century (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018 ). The situation is similar in the UK (Office for National Statistics 2017 ). Therefore, the number of people in these countries who are deaf or hard-of-hearing is likely to increase. Admittedly, technological and medical progress may prevent this, but this is not guaranteed. Loss of hearing due to age has been associated with impacts on quality of life, social relationships, and cognitive function (Fortunato et al. 2016 ). Learning sign language prior to the advent of hearing loss could ameliorate these impacts and make this transition less distressing. Learning another language such as German does not necessarily provide a benefit in the same way. For example, if you failed to learn German before you moved to Germany, you would be in a difficult position. However, apart from taking language lessons, you could also turn to a translator to translate German into your primary language. If you become hard of hearing when you rely on oral communication, you have lost your full capacity to communicate in your primary language. Without knowledge of sign language, a translator will provide no additional benefit to you. You have not just moved to another country where people do not understand you; there is no chance of going home. This is a reason that teaching sign language specifically confers a benefit to the individual over the teaching of other second languages. Over time, as younger generations transition, it would allow effective communication with the elderly as they become hard of hearing, without requiring hearing assistive technology.

In sum, the learning of sign language will benefit individuals by promoting a bimodal form of communication that can facilitate expressive communication. These benefits will be particularly significant for those who are, or will become, deaf. It should be noted, however, that the degree to which individuals (as well as society in general) will benefit depends on the degree to which students successfully acquire sign language in school, and the extent to which they will retain it throughout their lifetime. This is hard to predict prospectively. We will simply note even if people only acquired a small amount of sign language, this could have significant benefits in terms of the social acceptance of deaf culture. Furthermore, learning a little sign language at school would provide a platform on which to learn further sign language when needed (for example, if they become deaf).

The Roman lawyer Cicero gives one of the earliest definitions of justice as “the virtue which assigns to each his due” (Cicero 1933 ). This broad definition still captures the core concerns of justice today. While justice encompasses many elements of ethics and law, it fundamentally represents a concern for giving people what they are ‘due’. Educational resources (such as a teacher’s time, a school’s budget) are limited. This raises the question of how we ought to allocate these resources in a way that assigns each their due.

There are several different theories of distributive justice which give different answers to the question of how we should distribute a limited resource. However, the most widely accepted theories are versions of ‘prioritarianism’ (Parfit 1997 ), which is the view that, other things being equal, benefits matter more, the more worse off their recipients. Footnote 1 One version of prioritarianism is John Rawls’ theory of justice, which includes the difference principle (Rawls 1999 ). It holds that differences between the best-off and the worst-off are only permissible if they raise the absolute standing of the worst off. On this view, we should distribute educational resources so that the worst off in society are as well off as they possibly can be.

Teaching sign language will benefit groups in society who are significantly marginalised. In many contexts, there will be strong reasons of justice to prioritise teaching sign language over other languages, as outlined further here.

Being able to communicate is an essential component of being able to participate fully in society. For this reason, it is more important to teach children a language that will allow them to communicate with those whose capacities for communication and engagement with society are limited by a language barrier. This is not necessarily the case with all second languages currently being taught, such as some European languages of wealthy countries where migrants are likely to be highly educated and already speak English. Therefore, linguistic minorities that are less likely or able to speak English have a greater claim to their language being represented on the educational curriculum than those who can speak English.

With this line of argument, it is also important to establish the deaf or hard-of-hearing not only as a linguistic minority, but also as a marginalised minority who are worse-off in a way that is directly related to language. It is more difficult for people who are deaf to communicate with other members of society and go about their daily lives with the ease of those who are not deaf can do. Although many people do not recognise deafness as a disability in itself (Bauman et al. 2014 ), the social implications of not being able to communicate in the same way as the majority of society are clear (regardless of how we conceptualise these barriers). It is, for example, more difficult to order a coffee or open a bank account if there is nobody who can communicate with you simply and effectively by non-oral means—that is, through languages such as Auslan. These are relatively trivial tasks, but it is also evident in more serious and important moments in life, such as being unable to communicate with medical staff during the birth of your child (Browne 2016 ). There is evidence of discrimination against the deaf in both Australia and the UK. Those who are deaf have poorer employment outcomes (Hill et al. 2017 ; Willoughby 2011 ; Winn 2007 ); as of 2015 in Australia, people with a communication disability such as deafness have a labour participation rate of only 37.5% (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017a ). Deaf people have increased difficulty with accessing primary healthcare services (Kuenburg et al. 2016 ), and in the UK, deaf mental healthcare service users stay in hospital twice as long as hearing patients (Baines et al. 2010 ). Deaf people have increased barriers accessing the criminal justice system in the UK (Elder and Schwartz 2018 ) and are not able to serve as jurors in Australia (Napier and McEwin 2015 ). Parents of deaf children have had to resort to the courts to ensure that their children receive education that is accessible to them (Busby 2018 ; Komesaroff 2004 ). Although some of these problems are systemic and institutional, if the number of people who were able to communicate in sign languages were to increase, even if that level of communication is not particularly strong or skilled, this will go some way to ameliorating the difficulties deaf people face as they go about their daily life. It will also normalise the use of sign languages in various contexts and could provide a societal background where discrimination against the deaf is less accepted.

Deafness, as noted above, also intersects with other marginalised groups such as the elderly. Forms of sign language can also be useful for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities, such as autism spectrum disorder, Down syndrome (Toth 2009 ), or the plethora of genetic syndromes identified in this genomic era. Emphasising alternate modalities of language may help in making these communication methods more accessible and/or normalised. Modified forms of sign language, such as Key Word Sign or Makaton, have proved highly valuable for people with intellectual disabilities (Beecher and Childre 2012 ; Meuris et al. 2015 ; van der Meer et al. 2012 ). Teaching sign language may benefit individuals with, for example, autism, either directly or indirectly by making communication with their friends, family members and support staff easier. Varieties of sign languages can form a part of or a more natural alternative to augmented communication devices, and increased knowledge may be helpful for those who require access to alternative or augmented communication. However, it is important to recognise here that in this context we are not referring specifically to sign languages such as Auslan or BSL. Auslan and BSL are not in any way ‘easier’ or less complex than spoken languages. Rather, we argue that the broader implementation, integration and normalisation of bimodality may foster a more conducive environment for those with other forms of communication disabilities. Having some knowledge of sign language may make it more accessible for people to use other forms of signed language to facilitate communication.

There is an additional key difference that makes it more just to learn a sign language than the languages of other marginalised linguistic minorities. Simply put, it is possible for someone who speaks French to learn how to speak English. Although there may be barriers for many people to learn another language (including, for example, access to educational resources and/or time to learn), and this should certainly be taken into consideration, second language learning is still generally possible. It is very difficult or impossible for someone who is profoundly deaf to communicate verbally in English or comprehend spoken English, particularly if they have not learnt to do so at a young age or prior to hearing loss. Communication in writing is not sufficient compensation. The language barrier is one of function and cannot be overcome by the deaf party learning another language. Thus, it is the onus of those who speak English to learn the most effective language with which to communicate—that is, sign language.

The benefits to deaf people do not just extend to being able to access more goods and services directly. Even with widespread integration of sign language into a curriculum, there will remain many hearing people who require an interpreter when communicating with deaf people. Deaf people have a right to communicate through an interpreter, particularly when it comes to vital services such as medical care. There are a limited number of sign language interpreters, and more are needed. In Australia, with the recent introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), the demand has increased and it is a matter of justice for this demand to be met (Campbell 2018 ). Three out of five children under 12 living with a communication disability, including deafness, have unmet needs for formal communication assistance (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017a ). Similarly, a 2017 government review found that there is a significant shortage of interpreters in the UK, with only 908 registered sign language interpreters in the entire UK (Department of Work & Pensions 2017 ). Integrating sign language into school curriculums will increase the exposure of young people to sign language, and may influence the number of those who choose to become interpreters. There is also the risk that speech pathology services may deteriorate in quality due to the increase in demand caused by the NDIS (Health Workforce Australia 2014 ), and so the ability to use a non-oral language to communicate may become even more important.

It is important that the training and work of skilled and certified sign language interpreters would remain essential, even if there were more widespread knowledge of sign language. Some knowledge of a language would not be sufficient to provide translation services in an ad-hoc fashion in the context of medical care, education, or public events. A skilled interpreter would absolutely be required in many situations. There is the risk that some may overestimate their ability to communicate in sign language and thus counterproductively impair effective communication. However, in small daily tasks where an interpreter is unlikely to be resourced, some knowledge of a language—such as numbers, and common words—would facilitate effective communication.

A greater emphasis on learning sign language at schools can also serve to rectify historical injustices. The Milan conference of 1880 solidified the teaching of the oralist tradition and greatly discouraged the use of sign languages in deaf education (Moores 2010 ). This has had profound impacts on deaf pedagogy and the growth and development of sign languages. For a long time, sign languages were not seen as legitimate languages. Although the teaching of sign language in schools cannot rectify the harms already done to those who were unable to fully master, learn, or communicate in the most appropriate language for their needs, it can go some way to legitimising sign language as a valuable form of communication that should be encouraged.

Another justice-based reason to prioritise teaching sign language over other languages is that it would enable countries such as Australia and the UK to fulfil their obligations under The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which was ratified in 2009 by both Australia and the UK (Australian Law Reform Commission n.d.; Fraser Butlin 2011 ). By ratifying the CRPD, these governments imposed on themselves several obligations in relation to sign language including:

Facilitating the learning of sign language and the promotion of the linguistic identity of the deaf community; Taking appropriate measures to employ teachers, including teachers with disabilities, who are qualified in sign language and/or Braille, and to train professionals and staff who work at all levels of education.

Given the lack of easy access to sign language education, there is an imperative on these governments to undertake more drastic means to increase the uptake of Auslan or BSL. Making sign languages compulsory in schools would be the most effective way to discharge their obligations in relation to the CRPD.

Amongst all this, there is the question as to whether the teaching of sign language will come at a cost to the individual. If it does, then this must be weighed against the benefits to others who are currently worse off or marginalised (i.e., the deaf). This cost to the individual student may be the provision of sign language education at the expense of another language that it is more in the student’s interests to learn, and that it may reduce the frequency of other forms of bilingualism on a population level. If this cost is significant (i.e. it affects many students), then this is reason to reconsider our contention. However, we do not believe that a policy of compulsory sign language education will make a large number of students or society worse off, at least in Australia and the United Kingdom.

Firstly, as of the 2016 Census, 21% of Australians speak a language other than English at home (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017b ). However, less than 10% of students learn language to a Year 12 level (and this includes those who are already native language speakers) (Mayfield 2017 ). This suggests that most of those who speak a second language do not learn it at school. In addition, schools frequently offer multiple languages, so that students can continue to pursue learning several languages. We accept that in the event that a school only has the resources to teach one language, there may be considerations for an exception to making sign language education available if there is another language with a greater claim to be prioritised in a particular context. Depending on regional context, there may be a case for another language to be prioritised along with, or instead of, sign language. For example, if there is an area in an English-speaking country with a high number of unilingual Spanish speakers, and resources or individual capacity are not available to facilitate learning English (including resources such as a person’s time or capacity), then Spanish has a strong case to be prioritised alongside (or instead of) sign language. Additionally, there might be reasons to promote the teaching of Indigenous languages over sign language in certain areas, to promote the continued survival of particular cultures.

These reasons stem from the same considerations of justice we have outlined earlier. However, we do not believe that exceptions such as these need to be widespread. This is because when we are addressing prioritisation of sign language education, the cost should be considered within the context of the whole curriculum rather than only the languages curriculum. We do not believe that generally, making sign language a necessary part of the curriculum need be an either/or proposition; there will be ways to implement sign language education without seriously impacting the provision of other second languages. For example, for schools with extremely limited resources or very low enrolments, an external sign language educational course could be established within the overall public school system, and students could be incentivised to attend.

Secondly, sign language is unique in a certain respect; most deaf children are born to hearing parents (Mitchell and Karchmer 2004 ), and so parents will often learn sign language (if they do at all) alongside the child whose native language it is likely to be. Children who are deaf do not have the opportunity to learn a language at home in the same way as many second language speakers. Therefore, the school is a key nexus for the spread of languages such as Auslan or BSL. There is much to suggest that language education in general is in serious need of investment,but there is also a strong argument that any attempts to overhaul or prioritise language education curriculums should focus on sign language(s). Even basic communication skills in sign language, rather than fluency, may have an important impact on society.

4 Identity, Deaf culture, and language

There is significant tension between those who view deafness as something to be ‘fixed’, and those who view it as the basis for a rich cultural tradition (capital-D ‘Deaf’). This tension is exemplified in the debate around cochlear implants. Cochlear implants enable children with hearing loss to hear, with varying degrees of efficacy. It is generally encouraged to have cochlear implants implanted in children while they are very young, due to the sensitive period and neural plasticity that impacts their acquisition of oral communication (Tomblin et al. 2005 ). Implanting very young children with cochlear implants is done so that they grow up accustomed to the sensory input provided and more adequately adjust to oral communication methods.

However, some members of the Deaf community do not view cochlear implants as a positive development for deaf children. Rather, they view the advent of cochlear implants as facilitating a form of cultural erasure or ethnocide (Sparrow 2010 ). Deaf children undergoing cochlear implant surgery are thereafter generally raised in the ‘oralist’ tradition, where a strong emphasis is made on acquiring and practicing the skill of oral communication. This is at odds with a tradition more in line with the cultural model, which places an emphasis on sign language as a means of communication. Parents of children with cochlear implants have been discouraged by practitioners from signing with their children, with sign language viewed as a kind of ‘crutch’ that discourages effective oral communication (Humphries et al. 2017 ). Deaf children raised in an oralist tradition, with its strong emphasis on oral communication, are thus likely to learn sign language later in life, if they do at all. This may impact on their communication skills, their sense of identity, and their capacity to sign. Most deaf children are born to hearing parents (Mitchell and Karchmer 2004 ), and it is likely that hearing parents in general would wish their child to share their mode of communication—that is, oral language. This means that they may prioritise an oralist approach to what may be the detriment for the child.

Outcomes from cochlear implants vary greatly depending on the degree and nature of hearing loss (Cosetti and Waltzman 2012 ; Fontenot et al. 2018 ) and timing of implant (Dettman et al. 2016 ), and many children with cochlear implants do not attain the same level of spoken language outcomes as their non-deaf peers (Geers et al. 2009 ). Therefore, it would seem to remain beneficial on an individual level for children with cochlear implants to learn sign language. There is also, again, the level of group benefit. If there are fewer deaf people or people who view themselves as Deaf, the concern is that Deaf culture will lose many (potential) members. This sort of decrease in numbers of a cultural group is, naturally, generally seen as a negative by members of that culture who value its continued existence. Therefore, it would similarly be beneficial to a specific group of people (the culturally Deaf) that sign language be normalised and more widely taught and accessible, particularly to those who may otherwise have been discouraged from using it (deaf or hard-of-hearing people raised in an oralist tradition).

Much could be written on this source of disagreement between medical and cultural or social models of disability. However, this will not be explored at length here. It is sufficient to recognise that the Deaf community has a strong claim that their culture and practices are threatened by an emphasis on oral communication that is facilitated by the increased use of cochlear implants. However, there is concurrently a strong claim that children who are born deaf have the right to have access to the faculty of hearing if it is possible for them to do so (Byrd et al. 2011 ). It has been stated that cochlear implants provide the child with more of an ‘open future’ (Nunes 2001 ). Although the choice has been made by the parents to provide the deaf child with a degree of hearing, the child can later exercise that choice to reject the implant and the hearing abilities it provides. However, the reverse is not as true, as the older a child is when they receive a cochlear implant the less likely they are to effectively acquire oral communication (Boons et al. 2012 ). Therefore, providing young children with a cochlear implant may provide them with an increased range of options when making their life plans, if it is effective. Many culturally Deaf parents are now choosing cochlear implants for their children and raising them in a bimodal bilingual tradition (Mitchiner 2015 ).

It is important here not to assume that a deaf child would automatically be in favour of the use of a cochlear implant. Although teenagers with cochlear implants may generally view them positively (Wheeler et al. 2007 ), there are a number of cases where a cochlear implant may be rejected. This can be because the hearing facilitated by the cochlear implant is so poor as to be more of a hindrance than a help, dislike or pain associated with the sensation of hearing provided by the implant, difficulties with the extensive speech therapy generally required after cochlear implant surgery, or a rejection of the oralist tradition emblematised by the cochlear implant and concomitantly, an embracement of the Deaf identity (Watson and Gregory 2005 ). There are good reasons for the latter; involvement with the Deaf community has a positive impact on the mental health of deaf people (Fellinger et al. 2012 ). These may be valid and sensible reasons for an autonomous agent to reject the use of the cochlear implant in favour of their natural state of deafness.

However, while the decision to choose even a modicum of hearing over complete deafness is seen as the ‘obvious’ choice by hearing members of society, the converse choice to embrace deafness or Deafness is less understood and not necessarily seen as a reasonable choice to be supported. It is difficult to see how this choice between ‘hearing’ and ‘Deafness’ can be made in an autonomous fashion if the alternative option to oral culture—Deafness—is not sufficiently supported or validated by society. If a deaf person has not learnt sign language, how can it reasonably be said that they can make an autonomous and informed choice to embrace a Deaf identity with the ease that would have been provided to them if they had been raised in a manualist tradition? The debate may continue regarding the education of deaf children in their early years (a harm reduction approach would advocate for not depriving young deaf children of sign language regardless of cochlear implant status (Humphries et al. 2012 )), but at least if all children learn sign language in school, this will allow children full access to both worlds and facilitate fully autonomous choice later in life. All children who have difficulties with hearing will be able to make an informed and autonomous choice about whether they identify as deaf, or Deaf, even if they have been raised with a focus on oralism, because access to a key part of Deaf culture—the language—will be normalised and made accessible to them by default. Importantly, it will also encourage a wider intercultural understanding, and this will reduce some of the difficulties associated with embracing Deafness, decreasing some of the pressures that may compel someone to make the alternative choice when they would prefer not to.

In addition to the direct benefits to the deaf child and family gained through significantly increased availability of sign language, there will also be broader cultural benefits to the Deaf community. If the number of people who have familiarity with sign language greatly increases, there will be advantages beyond the direct facilitation of communication. Even if students at school only learn rudimentary levels of sign language, the availability of and increased familiarity with sign language may have a positive impact on the wellbeing of the members of the Deaf community. This would be because increased availability of sign language could make Deaf people feel more included and welcomed in society. It would also facilitate societal familiarity with Deaf culture and validate deaf needs amongst hearing peers. If children lack familiarity with deafness and the needs of deaf people, they are more likely to view deafness negatively and be less likely to accept deaf peers (Batten et al. 2013 ). Therefore, even if sign language education does not produce widespread fluency, increased familiarity with elements of Deaf culture, such as sign language, are likely to have a positive impact on the Deaf community.

5 Conclusion

There are a number of reasons why there is a strong moral claim for sign language to be compulsory, or at least highly prioritised, in the school curriculum. It would benefit individuals, and it would also benefit groups. The benefit to the deaf and/or culturally Deaf is a matter of justice, as the cost to the individual and other groups would be slight. Indeed, learning a sign language may provide hearing children with unique benefits. People living with a communication disability are also significantly marginalised, economically disadvantaged and have unmet needs for assistance; widespread knowledge of sign languages would ameliorate some of these associated negative impacts. It would also enable deaf or hard-of-hearing people to make an autonomous choice between hearing culture and Deaf culture, or embrace both.

As noted previously, this argument presents a moral perspective rather than a specific policy proposal. Here, we have outlined the ethical reasons why such policy proposals should be pursued and prioritised. In order to translate this into more concrete plans of action, extensive consultation would be required with the Deaf community, as well as service providers, teachers, and other education professionals.

It is a responsibility of society to create an environment that is most conducive to the welfare of everyone, including deaf people. Part of this process would be ensuring that as many people as possible can communicate in the most appropriate languages for the needs of this community, which are sign languages. The most effective way to ensure that as many people as possible would communicate in a sign language would be to integrate sign languages into the school curriculum.

Two other view of distributive justice are egalitarianism—which aims for a distribution in which all are equal; and utilitarianism, in which resources should be distributed to provide the greatest benefits to the greatest number. Both are subject to serious objections as theories of justice. For example see Crisp, Roger. 2003. ‘Equality, Priority, and Compassion’ Ethics vol. 113, Issue 4: 745–763 and Dworkin, Ronald, 2000, Sovereign Virtue: the theory and practice of equality , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Alladi, S., T.H. Bak, V. Duggirala, B. Surampudi, M. Shailaja, A.K. Shukla, S. Kaul, et al. 2013. Bilingualism delays age at onset of dementia, independent of education and immigration status. Neurology 81 (22): 1938.

Article Google Scholar

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. 2011. Foreign language enrollments in K–12 public schools: Are students prepared for a global society? Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://www.actfl.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/ReportSummary2011.pdf .

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2017a. Australians living with communication disability. Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/773675A7F2B7400ACA2581E80011A786/$File/australians%20living%20with%20communication%20disability.pdf .

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2017b. Census reveals a fast changing, culturally diverse nation. Retrieved May 1, 2019 from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/lookup/Media%20Release3 .

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2018. Older Australia at a glance. Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australia-at-a-glance/contents/demographics-of-older-australians/australia-s-changing-age-and-gender-profile .

Australian Law Reform Commission. n.d. Equality, capacity and disability in commonwealth laws: Legislative and regulatory framework. Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://www.alrc.gov.au/publications/equality-capacity-and-disability-commonwealth-laws/legislative-and-regulatory-framework .

Baines, D., N. Patterson, and S. Austen. 2010. An investigation into the length of hospital stay for deaf mental health service users. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 15 (2): 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enq003 .

Batten, G., P.M. Oakes, and T. Alexander. 2013. Factors associated with social interactions between deaf children and their hearing peers: A systematic literature review. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 19 (3): 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/ent052 .

Bauman, H., L. Dirksen, and J.J. Murray. 2014. Deaf gain: An introduction. In Deaf gain: Raising the stakes for human diversity , ed. H. Bauman, L. Dirksen, and J.J. Murray. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Google Scholar

Beecher, L., and A. Childre. 2012. Increasing literacy skills for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Effects of integrating comprehensive reading instruction with sign language. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities 47 (4): 487–501.

Bettger, J.G., K. Emmorey, S.H. McCullough, and U. Bellugi. 1997. Enhanced facial discrimination: Effects of experience with American sign language. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 2 (4): 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.deafed.a014328 .

Bialystok, E., and F.I.M. Craik. 2010. Cognitive and linguistic processing in the bilingual mind. Current Directions in Psychological Science 19 (1): 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721409358571 .

Boons, T., J.P.L. Brokx, I. Dhooge, J.H.M. Frijns, L. Peeraer, A. Vermeulen, A. van Wieringen, et al. 2012. Predictors of spoken language development following pediatric cochlear implantation. Ear and Hearing 33 (5): 617–639.

Browne, R. 2016. Childbirth not the same as ‘buying a bag of chips’: Disability discrimination case. The Sydney Morning Herald . Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://www.smh.com.au/national/childbirth-not-the-same-as-buying-a-bag-of-chips-disability-discrimination-case-20160823-gqzbs1.html .

Bryan, K., J. Freer, and C. Furlong. 2010. Language and communication difficulties in juvenile offenders. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 42 (5): 505–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820601053977 .

Busby, E. 2018. GCSE in British Sign Language may be introduced after deaf boy’s campaign. The Independent . Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/education-news/british-sign-launguage-gcse-government-campaign-daniel-jillings-department-education-a8474376.html .

Byrd, S., A.G. Shuman, S. Kileny, and P.R. Kileny. 2011. The right not to hear: The ethics of parental refusal of hearing rehabilitation. The Laryngoscope 121 (8): 1800–1804. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.21886 .

Campbell, C. 2018. Auslan interpreter shortage ‘getting worse with NDIS rollout’. ABC . Retrieved May 1, 2019 from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-07-11/auslan-interpreter-shortage-worsening-in-sa/9974142.

Carlson, S.M., and A.N. Meltzoff. 2008. Bilingual experience and executive functioning in young children. Developmental Science 11 (2): 282–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00675.x .

Casey, S., K. Emmorey, and H. Larrabee. 2012. The effects of learning American Sign Language on co-speech gesture. Bilingualism (Cambridge, England) 15 (4): 677–686. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728911000575 .

Cicero, M.T. 1933. On the Nature of the Gods (trans: Rackham, H.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Colzato, L.S., M.T. Bajo, W. van den Wildenberg, D. Paolieri, S. Nieuwenhuis, W. La Heij, and B. Hommel. 2008. How does bilingualism improve executive control? A comparison of active and reactive inhibition mechanisms. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition 34 (2): 302–312.

Cosetti, M.K., and S.B. Waltzman. 2012. Outcomes in cochlear implantation: Variables affecting performance in adults and children. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America 45 (1): 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2011.08.023 .

Cox, S.R., T.H. Bak, M. Allerhand, P. Redmond, J.M. Starr, I.J. Deary, and S.E. MacPherson. 2016. Bilingualism, social cognition and executive functions: A tale of chickens and eggs. Neuropsychologia 91: 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.08.029 .

Dalzell, S. 2016. Auslan national curriculum for Australian schools hailed as ‘huge step’ for deaf community. ABC News . Retrieved May 1, 2019 from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-12-19/deaf-community-hails-school-rollout-of-auslan-curriculum/8132474 .

Daniels, M. 1994. The effect of sign language on hearing children’s language development. Communication Education 43 (4): 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529409378987 .

Daniels, M. 2004. Happy hands: The effect of ASL on hearing children’s literacy. Reading Research and Instruction 44 (1): 86–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388070409558422 .

Department of Work & Pensions. 2017. Market review of British Sign Language and communications provision for people who are deaf or have hearing loss . Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/630960/government-response-market-review-of-bsl-and-communications-provision-for-people-who-are-deaf-or-have-hearing-loss.pdf .

Dettman, S.J., R.C. Dowell, D. Choo, W. Arnott, Y. Abrahams, A. Davis, R.J. Briggs, et al. 2016. Long-term communication outcomes for children receiving cochlear implants younger than 12 months: A multicenter study. Otology & Neurotology 37 (2): 82–95.

Elder, B.C., and M.A. Schwartz. 2018. Effective deaf access to justice. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 23 (4): 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/eny023 .

Elliott, E.A., and A.M. Jacobs. 2013. Facial expressions, emotions, and sign languages. Frontiers in Psychology 4: 115. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00115 .

Emmorey, K., M.R. Giezen, and T.H. Gollan. 2016. Psycholinguistic, cognitive, and neural implications of bimodal bilingualism. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19 (2): 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1366728915000085 .

Emmorey, K., E. Klima, and G. Hickok. 1998. Mental rotation within linguistic and non-linguistic domains in users of American sign language. Cognition 68 (3): 221–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(98)00054-7 .

Emmorey, K., S.M. Kosslyn, and U. Bellugi. 1993. Visual imagery and visual-spatial language: Enhanced imagery abilities in deaf and hearing ASL signers. Cognition 46 (2): 139–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(93)90017-P .

Fellinger, J., D. Holzinger, and R. Pollard. 2012. Mental health of deaf people. The Lancet 379 (9820): 1037–1044. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61143-4 .

Fontenot, T.E., C.K. Giardina, M.T. Dillon, M.A. Rooth, H.F. Teagle, L.R. Park, D.C. Fitzpatrick, et al. 2018. Residual cochlear function in adults and children receiving cochlear implants: Correlations with speech perception outcomes. Ear and Hearing . https://doi.org/10.1097/aud.0000000000000630 .

Fortunato, S., F. Forli, V. Guglielmi, E. De Corso, G. Paludetti, S. Berrettini, and A.R. Fetoni. 2016. A review of new insights on the association between hearing loss and cognitive decline in ageing. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica 36 (3): 155–166. https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-993 .

Fraser Butlin, S. 2011. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Does the Equality Act 2010 Measure up to UK International Commitments? Industrial Law Journal 40 (4): 428–438. https://doi.org/10.1093/indlaw/dwr015 .

Geers, A.E., J.S. Moog, J. Biedenstein, C. Brenner, and H. Hayes. 2009. Spoken language scores of children using cochlear implants compared to hearing age-mates at school entry. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 14 (3): 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enn046 .

Health Workforce Australia. 2014. Australia’s Health Workforce Series—Speech pathologists in focus. Retrieved May 1, 2019 from http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/133228/20150419-0017/www.hwa.gov.au/sites/default/files/HWA_Speech_Pathologists_in_Focus_V1.pdf .

Hilchey, M.D., and R.M. Klein. 2011. Are there bilingual advantages on nonlinguistic interference tasks? Implications for the plasticity of executive control processes. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 18 (4): 625–658. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-011-0116-7 .

Hill, S., R. Wicks, L. Cook, C. Regan, S. Fleming, and S. Hards. 2017. What works: Hearing loss and employment. Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/hearing-loss-what-works-guide-employment.pdf .

Hore, M. 2017. Call for sign language lessons in Vic schools. The Herald Sun . Retrieved May 1, 2019 from http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/victoria/sign-language-call-for-auslan-lessons-in-vic-schools/news-story/1d56f3adbac22448bf24ead546c12af3 .

Humphries, T., P. Kushalnagar, G. Mathur, D.J. Napoli, C. Padden, C. Rathmann, and S.R. Smith. 2012. Language acquisition for deaf children: Reducing the harms of zero tolerance to the use of alternative approaches. Harm Reduction Journal 9: 16–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-9-16 .

Humphries, T., P. Kushalnagar, G. Mathur, D.J. Napoli, C. Padden, C. Rathmann, and S. Smith. 2017. Discourses of prejudice in the professions: The case of sign languages. Journal of Medical Ethics 43 (9): 648.

Jiang, J., J. Ouyang, and H. Lui. 2016. Can learning a foreign language foster analytic thinking? Evidence from Chinese EFL learners’ writings. PLoS ONE 11 (10): e0164448. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164448 .

Komesaroff, L. 2004. Allegations of unlawful discrimination in education: Parents taking their fight for Auslan to the courts. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 9 (2): 210–218.

Kuenburg, A., P. Fellinger, and J. Fellinger. 2016. Health care access among deaf people. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 21 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/env042 .

Lauchlan, F., M. Parisi, and R. Fadda. 2012. Bilingualism in Sardinia and Scotland: Exploring the cognitive benefits of speaking a ‘minority’ language. International Journal of Bilingualism 17 (1): 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006911429622 .

Law, J., R. Rush, I. Schoon, and S. Parsons. 2009. Modeling developmental language difficulties from school entry into adulthood: Literacy, mental health, and employment outcomes. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 52 (6): 1401–1416. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0142) .

Long, R., and P. Bolton. 2016. Briefing paper: Language teaching in schools (England). (07388). House of Commons Library.

Make British Sign Language part of the National Curriculum. 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/200000 .

Mayfield, T. 2017. Australia’s ‘spectacular’ failure in languages. Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/australia-s-spectacular-failure-in-languages .

Meuris, K., B. Maes, and I. Zink. 2015. Teaching adults with intellectual disability manual signs through their support staff: A key word signing program. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 24 (3): 545–560. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0062 .

Mitchell, R.E., and M.A. Karchmer. 2004. Chasing the mythical ten percent: Parental hearing status of deaf and hard of hearing students in the United States. Sign Language Studies 4 (2): 138–163.

Mitchiner, J.C. 2015. Deaf parents of cochlear-implanted children: Beliefs on bimodal bilingualism. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 20 (1): 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enu028 .

Moores, D.F. 2010. Partners in progress: The 21st International Congress on Education of the Deaf and the Repudiation of the 1880 Congress of Milan. American Annals of the Deaf 155 (3): 309–310.

Moses, A.M., D.B. Golos, and C.M. Bennett. 2015. An alternative approach to early literacy: The effects of ASL in educational media on literacy skills acquisition for hearing children. Early Childhood Education Journal 43 (6): 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0690-9 .

Napier, J., and A. McEwin. 2015. Do deaf people have the right to serve as jurors in Australia? Alternative Law Journal 40 (1): 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969X1504000106 .

National Deaf Children’s Society. 2017. Right to Sign—British Sign Language in schools. Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://www.buzz.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/JR1219-Right-To-Sign-Report-AW-WEB.pdf .

Nunes, R. 2001. Ethical dimension of paediatric cochlear implantation. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 22 (4): 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011810303045 .

Office for National Statistics. 2017. National Population Projections: 2016-based statistical bulletin. Retrieved May 1, 2019 from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationprojections/bulletins/nationalpopulationprojections/2016basedstatisticalbulletin .

Oh, I.-H., J.H. Lee, D.C. Park, M. Kim, J.H. Chung, S.H. Kim, and S.G. Yeo. 2014. Hearing loss as a function of aging and diabetes mellitus: A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 9 (12): e116161. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116161 .

Orton, J. 2016. Issues in Chinese language teaching in Australian schools. Chinese Education & Society 49 (6): 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/10611932.2016.1283929 .

Parfit, D. 1997. Equality and priority. Ratio 10 (3): 202–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9329.00041 .

Perani, D., M. Farsad, T. Ballarini, F. Lubian, M. Malpetti, A. Fracchetti, J. Abutalebi, et al. 2017. The impact of bilingualism on brain reserve and metabolic connectivity in Alzheimer’s dementia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (7): 1690.

Perniss, P., A. Özyürek, and G. Morgan. 2015. the influence of the visual modality on language structure and conventionalization: Insights from sign language and gesture. Topics in Cognitive Science 7 (1): 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12127 .

Poarch, G.J., and E. Bialystok. 2015. Bilingualism as a model for multitasking. Developmental Review 35: 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.12.003 .

Rawls, J. 1999. A theory of justice . Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Romero Lauro, L.J., M. Crespi, C. Papagno, and C. Cecchetto. 2014. Making sense of an unexpected detrimental effect of sign language use in a visual task. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 19 (3): 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enu001 .

Rosen, R.S. 2010. American sign language curricula a review. Sign Language Studies 10 (3): 348–381.

Schoon, I., S. Parsons, R. Rush, and J. Law. 2010. Children’s language ability and psychosocial development: A 29-year follow-up study. Pediatrics 126 (1): e73.

Shook, A., and V. Marian. 2012. Bimodal bilinguals co-activate both languages during spoken comprehension. Cognition 124 (3): 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2012.05.014 .

Snow, P.C., and M.B. Powell. 2007. Oral language competence, social skills and high-risk boys: What are juvenile offenders trying to tell us? Children and Society 22 (1): 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2006.00076.x .

Sparrow, R. 2010. Implants and ethnocide: Learning from the cochlear implant controversy. Disability & Society 25 (4): 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687591003755849 .

Talbot, K.F., and R.H. Haude. 1993. The relation between sign language skill and spatial visualization ability: Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects. Perceptual and Motor Skills 77: 1387–1391. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1993.77.3f.1387 .

Tomblin, J.B., B.A. Barker, L.J. Spencer, X. Zhang, and B.J. Gantz. 2005. The effect of age at cochlear implant initial stimulation on expressive language growth in infants and toddlers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 48 (4): 853–867. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2005/059) .

Toth, A. 2009. Bridge of signs: Can sign language empower non-deaf children to triumph over their communication disabilities? American Annals of the Deaf 154 (2): 85–95.

van der Meer, L., D. Sutherland, M.F. O’Reilly, G.E. Lancioni, and J. Sigafoos. 2012. A further comparison of manual signing, picture exchange, and speech-generating devices as communication modes for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 6 (4): 1247–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.04.005 .

Watson, L.M., and S. Gregory. 2005. Non-use of cochlear implants in children: Child and parent perspectives. Deafness & Education International 7 (1): 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1179/146431505790560482 .

Wheeler, A., S. Archbold, S. Gregory, and A. Skipp. 2007. Cochlear implants: The young people’s perspective. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 12 (3): 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enm018 .

Willoughby, L. 2011. Sign language users’ education and employment levels: Keeping pace with changes in the general Australian population? Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 16 (3): 401–413.

Winn, S. 2007. Employment outcomes for people in Australia who are congenitally deaf: Has anything changed? American Annals of the Deaf 152 (4): 382–390.

Woumans, E.V.Y., P. Santens, A. Sieben, J.A.N. Versijpt, M. Stevens, and W. Duyck. 2015. Bilingualism delays clinical manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease. Bilingualism 18 (3): 568–574. https://doi.org/10.1017/s136672891400087x .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Research conducted at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute was supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. This work was also supported by the Wellcome Trust [203132]. This research was supported by the Research Training Program (RTP).

Funding was provided by Wellcome Trust (Grant No. 203132), State Government of Victoria, Operational Infrastructure Support Program, Department of Education and Training and Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Biomedical Ethics Research Group, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, 50 Flemington Rd, Parkville, VIC, 3052, Australia

Hilary Bowman-Smart, Christopher Gyngell & Julian Savulescu

Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, 3010, Australia

Hilary Bowman-Smart & Christopher Gyngell

Speech and Language Group, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, 50 Flemington Rd, Parkville, VIC, 3052, Australia

Angela Morgan

Department of Audiology and Speech Pathology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, 3010, Australia

Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, University of Oxford, St Ebbes St, Oxford, OX1 1PT, UK

Julian Savulescu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Julian Savulescu .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Bowman-Smart, H., Gyngell, C., Morgan, A. et al. The moral case for sign language education. Monash Bioeth. Rev. 37 , 94–110 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40592-019-00101-0

Download citation

Published : 23 November 2019

Issue Date : December 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40592-019-00101-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Sign language

- Deaf culture

- Language education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Improve your practice.

Enhance your soft skills with a range of award-winning courses.

75 Persuasive Speech Topics and Ideas

October 4, 2018 - Gini Beqiri

To write a captivating and persuasive speech you must first decide on a topic that will engage, inform and also persuade the audience. We have discussed how to choose a topic and we have provided a list of speech ideas covering a wide range of categories.

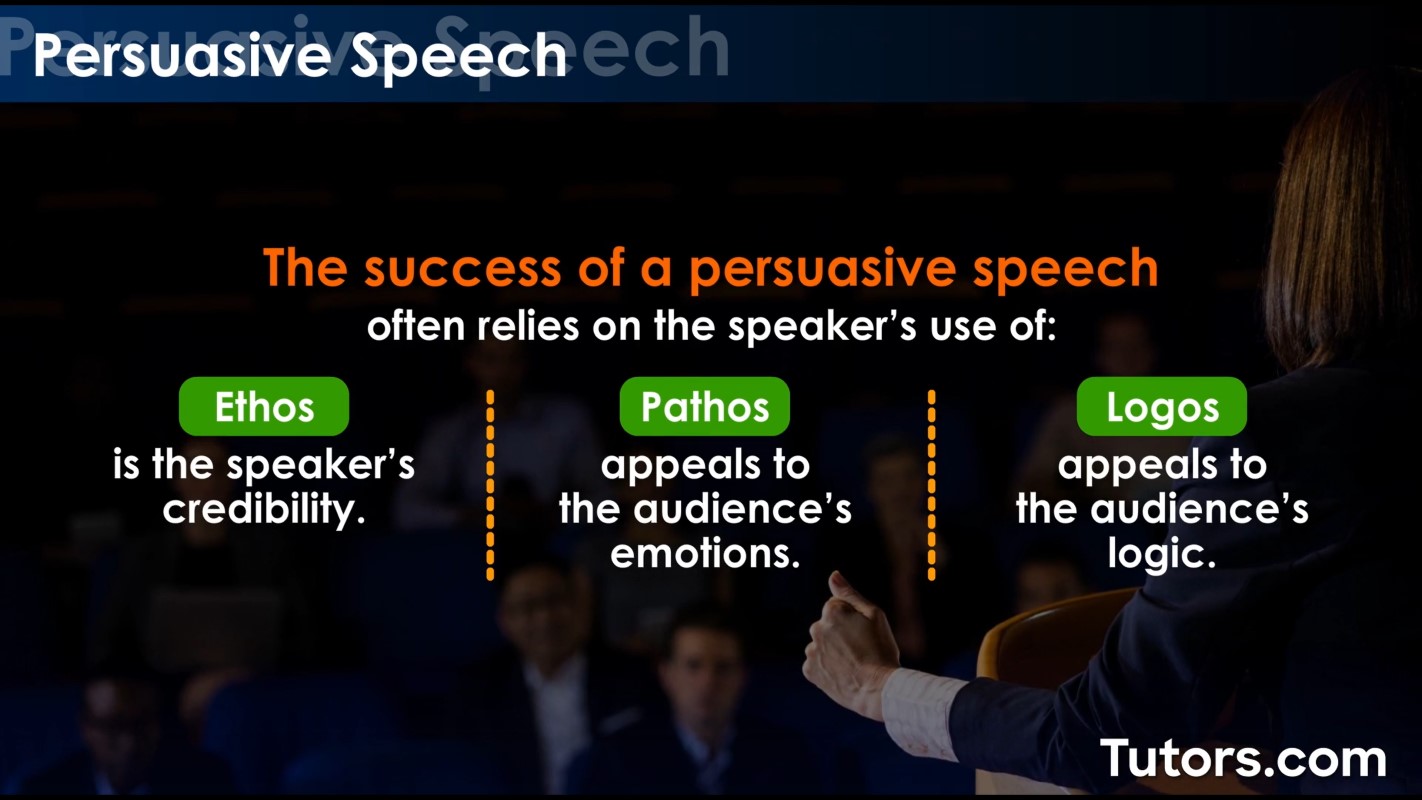

What is persuasive speech?

The aim of a persuasive speech is to inform, educate and convince or motivate an audience to do something. You are essentially trying to sway the audience to adopt your own viewpoint.

The best persuasive speech topics are thought-provoking, daring and have a clear opinion. You should speak about something you are knowledgeable about and can argue your opinion for, as well as objectively discuss counter-arguments.

How to choose a topic for your speech

It’s not easy picking a topic for your speech as there are many options so consider the following factors when deciding.

Familiarity

Topics that you’re familiar with will make it easier to prepare for the speech.

It’s best if you decide on a topic in which you have a genuine interest in because you’ll be doing lots of research on it and if it’s something you enjoy the process will be significantly easier and more enjoyable. The audience will also see this enthusiasm when you’re presenting which will make the speech more persuasive.

The audience’s interest

The audience must care about the topic. You don’t want to lose their attention so choose something you think they’ll be interested in hearing about.

Consider choosing a topic that allows you to be more descriptive because this allows the audience to visualize which consequently helps persuade them.

Not overdone

When people have heard about a topic repeatedly they’re less likely to listen to you as it doesn’t interest them anymore. Avoid cliché or overdone topics as it’s difficult to maintain your audience’s attention because they feel like they’ve heard it all before.

An exception to this would be if you had new viewpoints or new facts to share. If this is the case then ensure you clarify early in your speech that you have unique views or information on the topic.

Emotional topics

Emotions are motivators so the audience is more likely to be persuaded and act on your requests if you present an emotional topic.

People like hearing about issues that affect them or their community, country etc. They find these topics more relatable which means they find them more interesting. Look at local issues and news to discover these topics.

Desired outcome

What do you want your audience to do as a result of your speech? Use this as a guide to choosing your topic, for example, maybe you want people to recycle more so you present a speech on the effect of microplastics in the ocean.

Persuasive speech topics

Lots of timely persuasive topics can be found using social media, the radio, TV and newspapers. We have compiled a list of 75 persuasive speech topic ideas covering a wide range of categories.

Some of the topics also fall into other categories and we have posed the topics as questions so they can be easily adapted into statements to suit your own viewpoint.

- Should pets be adopted rather than bought from a breeder?

- Should wild animals be tamed?

- Should people be allowed to own exotic animals like monkeys?

- Should all zoos and aquariums be closed?

Arts/Culture

- Should art and music therapy be covered by health insurance?

- Should graffiti be considered art?

- Should all students be required to learn an instrument in school?

- Should automobile drivers be required to take a test every three years?

- Are sports cars dangerous?

- Should bicycles share the roads with cars?

- Should bicycle riders be required by law to always wear helmets?

Business and economy

- Do introverts make great leaders?