Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

Published on January 20, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on January 12, 2024.

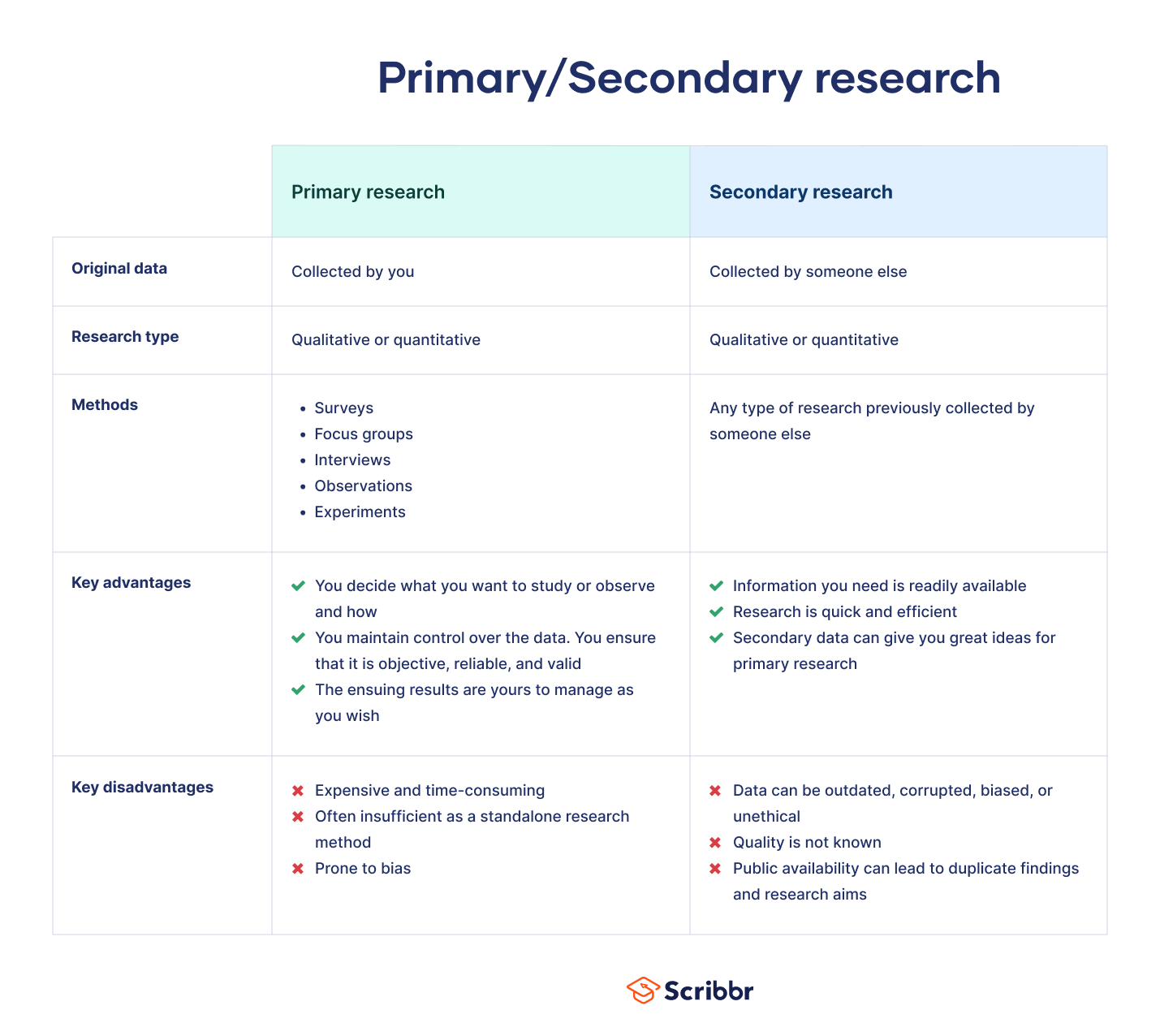

Secondary research is a research method that uses data that was collected by someone else. In other words, whenever you conduct research using data that already exists, you are conducting secondary research. On the other hand, any type of research that you undertake yourself is called primary research .

Secondary research can be qualitative or quantitative in nature. It often uses data gathered from published peer-reviewed papers, meta-analyses, or government or private sector databases and datasets.

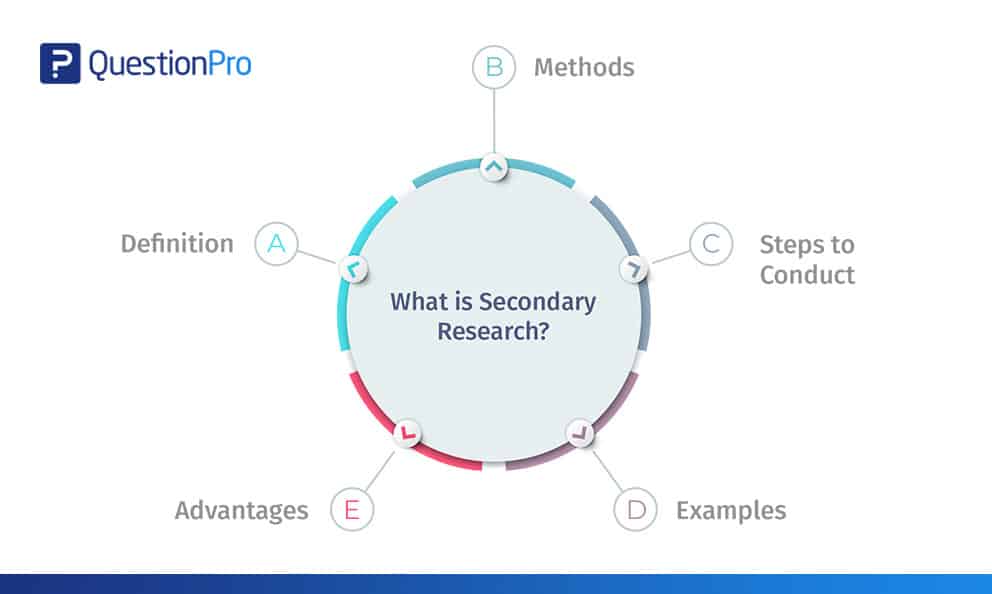

Table of contents

When to use secondary research, types of secondary research, examples of secondary research, advantages and disadvantages of secondary research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

Secondary research is a very common research method, used in lieu of collecting your own primary data. It is often used in research designs or as a way to start your research process if you plan to conduct primary research later on.

Since it is often inexpensive or free to access, secondary research is a low-stakes way to determine if further primary research is needed, as gaps in secondary research are a strong indication that primary research is necessary. For this reason, while secondary research can theoretically be exploratory or explanatory in nature, it is usually explanatory: aiming to explain the causes and consequences of a well-defined problem.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

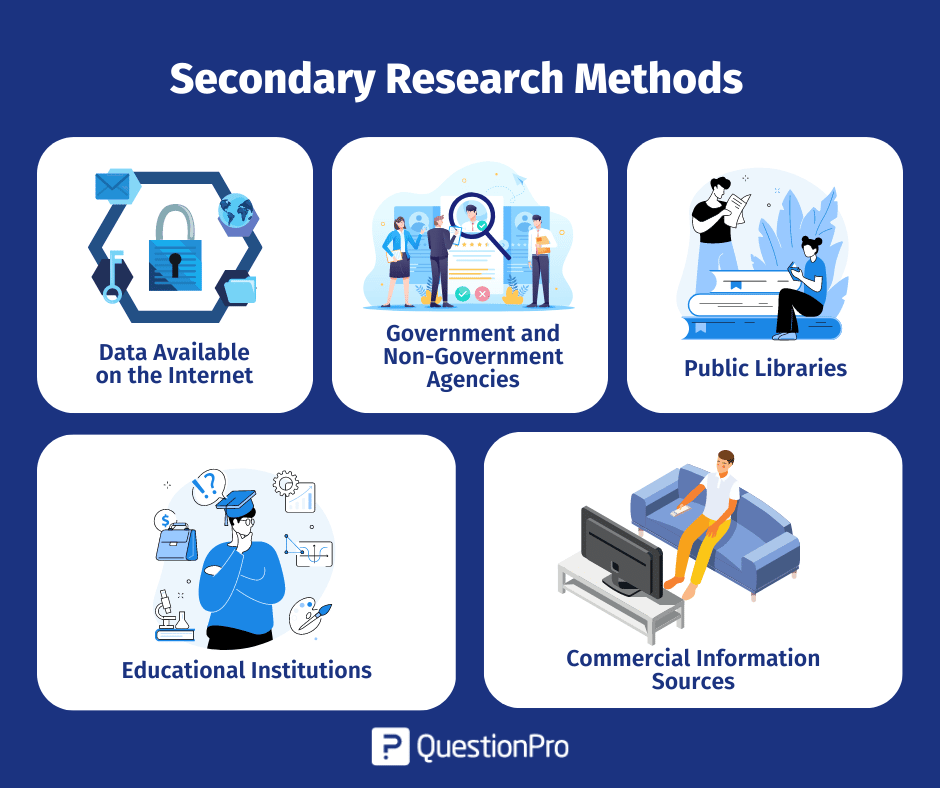

Secondary research can take many forms, but the most common types are:

Statistical analysis

Literature reviews, case studies, content analysis.

There is ample data available online from a variety of sources, often in the form of datasets. These datasets are often open-source or downloadable at a low cost, and are ideal for conducting statistical analyses such as hypothesis testing or regression analysis .

Credible sources for existing data include:

- The government

- Government agencies

- Non-governmental organizations

- Educational institutions

- Businesses or consultancies

- Libraries or archives

- Newspapers, academic journals, or magazines

A literature review is a survey of preexisting scholarly sources on your topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant themes, debates, and gaps in the research you analyze. You can later apply these to your own work, or use them as a jumping-off point to conduct primary research of your own.

Structured much like a regular academic paper (with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion), a literature review is a great way to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject. It is usually qualitative in nature and can focus on a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. A case study is a great way to utilize existing research to gain concrete, contextual, and in-depth knowledge about your real-world subject.

You can choose to focus on just one complex case, exploring a single subject in great detail, or examine multiple cases if you’d prefer to compare different aspects of your topic. Preexisting interviews , observational studies , or other sources of primary data make for great case studies.

Content analysis is a research method that studies patterns in recorded communication by utilizing existing texts. It can be either quantitative or qualitative in nature, depending on whether you choose to analyze countable or measurable patterns, or more interpretive ones. Content analysis is popular in communication studies, but it is also widely used in historical analysis, anthropology, and psychology to make more semantic qualitative inferences.

Secondary research is a broad research approach that can be pursued any way you’d like. Here are a few examples of different ways you can use secondary research to explore your research topic .

Secondary research is a very common research approach, but has distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of secondary research

Advantages include:

- Secondary data is very easy to source and readily available .

- It is also often free or accessible through your educational institution’s library or network, making it much cheaper to conduct than primary research .

- As you are relying on research that already exists, conducting secondary research is much less time consuming than primary research. Since your timeline is so much shorter, your research can be ready to publish sooner.

- Using data from others allows you to show reproducibility and replicability , bolstering prior research and situating your own work within your field.

Disadvantages of secondary research

Disadvantages include:

- Ease of access does not signify credibility . It’s important to be aware that secondary research is not always reliable , and can often be out of date. It’s critical to analyze any data you’re thinking of using prior to getting started, using a method like the CRAAP test .

- Secondary research often relies on primary research already conducted. If this original research is biased in any way, those research biases could creep into the secondary results.

Many researchers using the same secondary research to form similar conclusions can also take away from the uniqueness and reliability of your research. Many datasets become “kitchen-sink” models, where too many variables are added in an attempt to draw increasingly niche conclusions from overused data . Data cleansing may be necessary to test the quality of the research.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyze a large amount of readily-available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how it is generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2024, January 12). What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/secondary-research/

Largan, C., & Morris, T. M. (2019). Qualitative Secondary Research: A Step-By-Step Guide (1st ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Peloquin, D., DiMaio, M., Bierer, B., & Barnes, M. (2020). Disruptive and avoidable: GDPR challenges to secondary research uses of data. European Journal of Human Genetics , 28 (6), 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-0596-x

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, primary research | definition, types, & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a case study | definition, examples & methods, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Secondary Data – Types, Methods and Examples

Secondary Data – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Secondary Data

Definition:

Secondary data refers to information that has been collected, processed, and published by someone else, rather than the researcher gathering the data firsthand. This can include data from sources such as government publications, academic journals, market research reports, and other existing datasets.

Secondary Data Types

Types of secondary data are as follows:

- Published data: Published data refers to data that has been published in books, magazines, newspapers, and other print media. Examples include statistical reports, market research reports, and scholarly articles.

- Government data: Government data refers to data collected by government agencies and departments. This can include data on demographics, economic trends, crime rates, and health statistics.

- Commercial data: Commercial data is data collected by businesses for their own purposes. This can include sales data, customer feedback, and market research data.

- Academic data: Academic data refers to data collected by researchers for academic purposes. This can include data from experiments, surveys, and observational studies.

- Online data: Online data refers to data that is available on the internet. This can include social media posts, website analytics, and online customer reviews.

- Organizational data: Organizational data is data collected by businesses or organizations for their own purposes. This can include data on employee performance, financial records, and customer satisfaction.

- Historical data : Historical data refers to data that was collected in the past and is still available for research purposes. This can include census data, historical documents, and archival records.

- International data: International data refers to data collected from other countries for research purposes. This can include data on international trade, health statistics, and demographic trends.

- Public data : Public data refers to data that is available to the general public. This can include data from government agencies, non-profit organizations, and other sources.

- Private data: Private data refers to data that is not available to the general public. This can include confidential business data, personal medical records, and financial data.

- Big data: Big data refers to large, complex datasets that are difficult to manage and analyze using traditional data processing methods. This can include social media data, sensor data, and other types of data generated by digital devices.

Secondary Data Collection Methods

Secondary Data Collection Methods are as follows:

- Published sources: Researchers can gather secondary data from published sources such as books, journals, reports, and newspapers. These sources often provide comprehensive information on a variety of topics.

- Online sources: With the growth of the internet, researchers can now access a vast amount of secondary data online. This includes websites, databases, and online archives.

- Government sources : Government agencies often collect and publish a wide range of secondary data on topics such as demographics, crime rates, and health statistics. Researchers can obtain this data through government websites, publications, or data portals.

- Commercial sources: Businesses often collect and analyze data for marketing research or customer profiling. Researchers can obtain this data through commercial data providers or by purchasing market research reports.

- Academic sources: Researchers can also obtain secondary data from academic sources such as published research studies, academic journals, and dissertations.

- Personal contacts: Researchers can also obtain secondary data from personal contacts, such as experts in a particular field or individuals with specialized knowledge.

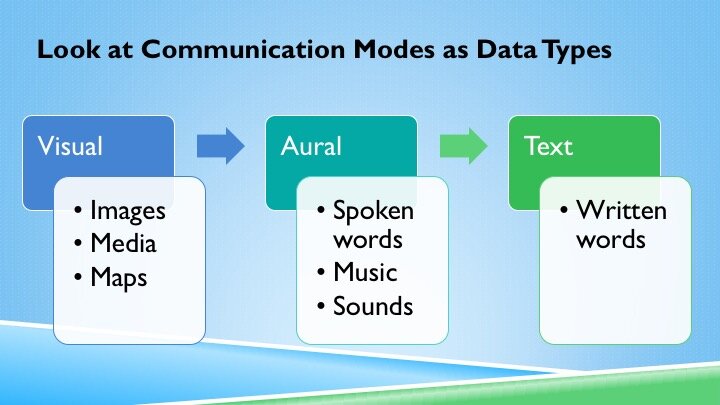

Secondary Data Formats

Secondary data can come in various formats depending on the source from which it is obtained. Here are some common formats of secondary data:

- Numeric Data: Numeric data is often in the form of statistics and numerical figures that have been compiled and reported by organizations such as government agencies, research institutions, and commercial enterprises. This can include data such as population figures, GDP, sales figures, and market share.

- Textual Data: Textual data is often in the form of written documents, such as reports, articles, and books. This can include qualitative data such as descriptions, opinions, and narratives.

- Audiovisual Data : Audiovisual data is often in the form of recordings, videos, and photographs. This can include data such as interviews, focus group discussions, and other types of qualitative data.

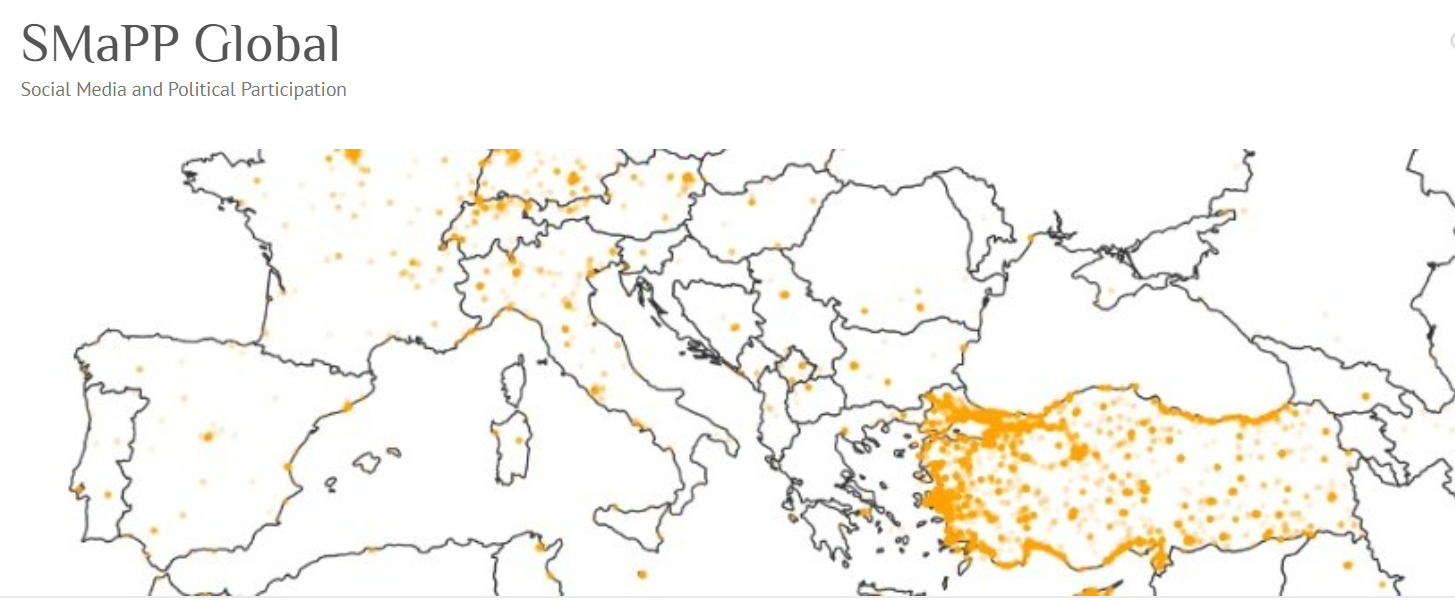

- Geospatial Data: Geospatial data is often in the form of maps, satellite images, and geographic information systems (GIS) data. This can include data such as demographic information, land use patterns, and transportation networks.

- Transactional Data : Transactional data is often in the form of digital records of financial and business transactions. This can include data such as purchase histories, customer behavior, and financial transactions.

- Social Media Data: Social media data is often in the form of user-generated content from social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. This can include data such as user demographics, content trends, and sentiment analysis.

Secondary Data Analysis Methods

Secondary data analysis involves the use of pre-existing data for research purposes. Here are some common methods of secondary data analysis:

- Descriptive Analysis: This method involves describing the characteristics of a dataset, such as the mean, standard deviation, and range of the data. Descriptive analysis can be used to summarize data and provide an overview of trends.

- Inferential Analysis: This method involves making inferences and drawing conclusions about a population based on a sample of data. Inferential analysis can be used to test hypotheses and determine the statistical significance of relationships between variables.

- Content Analysis: This method involves analyzing textual or visual data to identify patterns and themes. Content analysis can be used to study the content of documents, media coverage, and social media posts.

- Time-Series Analysis : This method involves analyzing data over time to identify trends and patterns. Time-series analysis can be used to study economic trends, climate change, and other phenomena that change over time.

- Spatial Analysis : This method involves analyzing data in relation to geographic location. Spatial analysis can be used to study patterns of disease spread, land use patterns, and the effects of environmental factors on health outcomes.

- Meta-Analysis: This method involves combining data from multiple studies to draw conclusions about a particular phenomenon. Meta-analysis can be used to synthesize the results of previous research and provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular topic.

Secondary Data Gathering Guide

Here are some steps to follow when gathering secondary data:

- Define your research question: Start by defining your research question and identifying the specific information you need to answer it. This will help you identify the type of secondary data you need and where to find it.

- Identify relevant sources: Identify potential sources of secondary data, including published sources, online databases, government sources, and commercial data providers. Consider the reliability and validity of each source.

- Evaluate the quality of the data: Evaluate the quality and reliability of the data you plan to use. Consider the data collection methods, sample size, and potential biases. Make sure the data is relevant to your research question and is suitable for the type of analysis you plan to conduct.

- Collect the data: Collect the relevant data from the identified sources. Use a consistent method to record and organize the data to make analysis easier.

- Validate the data: Validate the data to ensure that it is accurate and reliable. Check for inconsistencies, missing data, and errors. Address any issues before analyzing the data.

- Analyze the data: Analyze the data using appropriate statistical and analytical methods. Use descriptive and inferential statistics to summarize and draw conclusions from the data.

- Interpret the results: Interpret the results of your analysis and draw conclusions based on the data. Make sure your conclusions are supported by the data and are relevant to your research question.

- Communicate the findings : Communicate your findings clearly and concisely. Use appropriate visual aids such as graphs and charts to help explain your results.

Examples of Secondary Data

Here are some examples of secondary data from different fields:

- Healthcare : Hospital records, medical journals, clinical trial data, and disease registries are examples of secondary data sources in healthcare. These sources can provide researchers with information on patient demographics, disease prevalence, and treatment outcomes.

- Marketing : Market research reports, customer surveys, and sales data are examples of secondary data sources in marketing. These sources can provide marketers with information on consumer preferences, market trends, and competitor activity.

- Education : Student test scores, graduation rates, and enrollment statistics are examples of secondary data sources in education. These sources can provide researchers with information on student achievement, teacher effectiveness, and educational disparities.

- Finance : Stock market data, financial statements, and credit reports are examples of secondary data sources in finance. These sources can provide investors with information on market trends, company performance, and creditworthiness.

- Social Science : Government statistics, census data, and survey data are examples of secondary data sources in social science. These sources can provide researchers with information on population demographics, social trends, and political attitudes.

- Environmental Science : Climate data, remote sensing data, and ecological monitoring data are examples of secondary data sources in environmental science. These sources can provide researchers with information on weather patterns, land use, and biodiversity.

Purpose of Secondary Data

The purpose of secondary data is to provide researchers with information that has already been collected by others for other purposes. Secondary data can be used to support research questions, test hypotheses, and answer research objectives. Some of the key purposes of secondary data are:

- To gain a better understanding of the research topic : Secondary data can be used to provide context and background information on a research topic. This can help researchers understand the historical and social context of their research and gain insights into relevant variables and relationships.

- To save time and resources: Collecting new primary data can be time-consuming and expensive. Using existing secondary data sources can save researchers time and resources by providing access to pre-existing data that has already been collected and organized.

- To provide comparative data : Secondary data can be used to compare and contrast findings across different studies or datasets. This can help researchers identify trends, patterns, and relationships that may not have been apparent from individual studies.

- To support triangulation: Triangulation is the process of using multiple sources of data to confirm or refute research findings. Secondary data can be used to support triangulation by providing additional sources of data to support or refute primary research findings.

- To supplement primary data : Secondary data can be used to supplement primary data by providing additional information or insights that were not captured by the primary research. This can help researchers gain a more complete understanding of the research topic and draw more robust conclusions.

When to use Secondary Data

Secondary data can be useful in a variety of research contexts, and there are several situations in which it may be appropriate to use secondary data. Some common situations in which secondary data may be used include:

- When primary data collection is not feasible : Collecting primary data can be time-consuming and expensive, and in some cases, it may not be feasible to collect primary data. In these situations, secondary data can provide valuable insights and information.

- When exploring a new research area : Secondary data can be a useful starting point for researchers who are exploring a new research area. Secondary data can provide context and background information on a research topic, and can help researchers identify key variables and relationships to explore further.

- When comparing and contrasting research findings: Secondary data can be used to compare and contrast findings across different studies or datasets. This can help researchers identify trends, patterns, and relationships that may not have been apparent from individual studies.

- When triangulating research findings: Triangulation is the process of using multiple sources of data to confirm or refute research findings. Secondary data can be used to support triangulation by providing additional sources of data to support or refute primary research findings.

- When validating research findings : Secondary data can be used to validate primary research findings by providing additional sources of data that support or refute the primary findings.

Characteristics of Secondary Data

Secondary data have several characteristics that distinguish them from primary data. Here are some of the key characteristics of secondary data:

- Non-reactive: Secondary data are non-reactive, meaning that they are not collected for the specific purpose of the research study. This means that the researcher has no control over the data collection process, and cannot influence how the data were collected.

- Time-saving: Secondary data are pre-existing, meaning that they have already been collected and organized by someone else. This can save the researcher time and resources, as they do not need to collect the data themselves.

- Wide-ranging : Secondary data sources can provide a wide range of information on a variety of topics. This can be useful for researchers who are exploring a new research area or seeking to compare and contrast research findings.

- Less expensive: Secondary data are generally less expensive than primary data, as they do not require the researcher to incur the costs associated with data collection.

- Potential for bias : Secondary data may be subject to biases that were present in the original data collection process. For example, data may have been collected using a biased sampling method or the data may be incomplete or inaccurate.

- Lack of control: The researcher has no control over the data collection process and cannot ensure that the data were collected using appropriate methods or measures.

- Requires careful evaluation : Secondary data sources must be evaluated carefully to ensure that they are appropriate for the research question and analysis. This includes assessing the quality, reliability, and validity of the data sources.

Advantages of Secondary Data

There are several advantages to using secondary data in research, including:

- Time-saving : Collecting primary data can be time-consuming and expensive. Secondary data can be accessed quickly and easily, which can save researchers time and resources.

- Cost-effective: Secondary data are generally less expensive than primary data, as they do not require the researcher to incur the costs associated with data collection.

- Large sample size : Secondary data sources often have larger sample sizes than primary data sources, which can increase the statistical power of the research.

- Access to historical data : Secondary data sources can provide access to historical data, which can be useful for researchers who are studying trends over time.

- No ethical concerns: Secondary data are already in existence, so there are no ethical concerns related to collecting data from human subjects.

- May be more objective : Secondary data may be more objective than primary data, as the data were not collected for the specific purpose of the research study.

Limitations of Secondary Data

While there are many advantages to using secondary data in research, there are also some limitations that should be considered. Some of the main limitations of secondary data include:

- Lack of control over data quality : Researchers do not have control over the data collection process, which means they cannot ensure the accuracy or completeness of the data.

- Limited availability: Secondary data may not be available for the specific research question or study design.

- Lack of information on sampling and data collection methods: Researchers may not have access to information on the sampling and data collection methods used to gather the secondary data. This can make it difficult to evaluate the quality of the data.

- Data may not be up-to-date: Secondary data may not be up-to-date or relevant to the current research question.

- Data may be incomplete or inaccurate : Secondary data may be incomplete or inaccurate due to missing or incorrect data points, data entry errors, or other factors.

- Biases in data collection: The data may have been collected using biased sampling or data collection methods, which can limit the validity of the data.

- Lack of control over variables: Researchers have limited control over the variables that were measured in the original data collection process, which can limit the ability to draw conclusions about causality.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Primary Data – Types, Methods and Examples

Qualitative Data – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Data – Types Methods and Examples

Quantitative Data – Types, Methods and Examples

Information in Research – Types and Examples

What Is Secondary Data? A Complete Guide

What is secondary data, and why is it important? Find out in this post.

Within data analytics, there are many ways of categorizing data. A common distinction, for instance, is that between qualitative and quantitative data . In addition, you might also distinguish your data based on factors like sensitivity. For example, is it publicly available or is it highly confidential?

Probably the most fundamental distinction between different types of data is their source. Namely, are they primary, secondary, or third-party data? Each of these vital data sources supports the data analytics process in its own way. In this post, we’ll focus specifically on secondary data. We’ll look at its main characteristics, provide some examples, and highlight the main pros and cons of using secondary data in your analysis.

We’ll cover the following topics:

What is secondary data?

- What’s the difference between primary, secondary, and third-party data?

- What are some examples of secondary data?

- How to analyse secondary data

- Advantages of secondary data

- Disadvantages of secondary data

- Wrap-up and further reading

Ready to learn all about secondary data? Then let’s go.

1. What is secondary data?

Secondary data (also known as second-party data) refers to any dataset collected by any person other than the one using it.

Secondary data sources are extremely useful. They allow researchers and data analysts to build large, high-quality databases that help solve business problems. By expanding their datasets with secondary data, analysts can enhance the quality and accuracy of their insights. Most secondary data comes from external organizations. However, secondary data also refers to that collected within an organization and then repurposed.

Secondary data has various benefits and drawbacks, which we’ll explore in detail in section four. First, though, it’s essential to contextualize secondary data by understanding its relationship to two other sources of data: primary and third-party data. We’ll look at these next.

2. What’s the difference between primary, secondary, and third-party data?

To best understand secondary data, we need to know how it relates to the other main data sources: primary and third-party data.

What is primary data?

‘Primary data’ (also known as first-party data) are those directly collected or obtained by the organization or individual that intends to use them. Primary data are always collected for a specific purpose. This could be to inform a defined goal or objective or to address a particular business problem.

For example, a real estate organization might want to analyze current housing market trends. This might involve conducting interviews, collecting facts and figures through surveys and focus groups, or capturing data via electronic forms. Focusing only on the data required to complete the task at hand ensures that primary data remain highly relevant. They’re also well-structured and of high quality.

As explained, ‘secondary data’ describes those collected for a purpose other than the task at hand. Secondary data can come from within an organization but more commonly originate from an external source. If it helps to make the distinction, secondary data is essentially just another organization’s primary data.

Secondary data sources are so numerous that they’ve started playing an increasingly vital role in research and analytics. They are easier to source than primary data and can be repurposed to solve many different problems. While secondary data may be less relevant for a given task than primary data, they are generally still well-structured and highly reliable.

What is third-party data?

‘Third-party data’ (sometimes referred to as tertiary data) refers to data collected and aggregated from numerous discrete sources by third-party organizations. Because third-party data combine data from numerous sources and aren’t collected with a specific goal in mind, the quality can be lower.

Third-party data also tend to be largely unstructured. This means that they’re often beset by errors, duplicates, and so on, and require more processing to get them into a usable format. Nevertheless, used appropriately, third-party data are still a useful data analytics resource. You can learn more about structured vs unstructured data here .

OK, now that we’ve placed secondary data in context, let’s explore some common sources and types of secondary data.

3. What are some examples of secondary data?

External secondary data.

Before we get to examples of secondary data, we first need to understand the types of organizations that generally provide them. Frequent sources of secondary data include:

- Government departments

- Public sector organizations

- Industry associations

- Trade and industry bodies

- Educational institutions

- Private companies

- Market research providers

While all these organizations provide secondary data, government sources are perhaps the most freely accessible. They are legally obliged to keep records when registering people, providing services, and so on. This type of secondary data is known as administrative data. It’s especially useful for creating detailed segment profiles, where analysts hone in on a particular region, trend, market, or other demographic.

Types of secondary data vary. Popular examples of secondary data include:

- Tax records and social security data

- Census data (the U.S. Census Bureau is oft-referenced, as well as our favorite, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics )

- Electoral statistics

- Health records

- Books, journals, or other print media

- Social media monitoring, internet searches, and other online data

- Sales figures or other reports from third-party companies

- Libraries and electronic filing systems

- App data, e.g. location data, GPS data, timestamp data, etc.

Internal secondary data

As mentioned, secondary data is not limited to that from a different organization. It can also come from within an organization itself.

Sources of internal secondary data might include:

- Sales reports

- Annual accounts

- Quarterly sales figures

- Customer relationship management systems

- Emails and metadata

- Website cookies

In the right context, we can define practically any type of data as secondary data. The key takeaway is that the term ‘secondary data’ doesn’t refer to any inherent quality of the data themselves, but to how they are used. Any data source (external or internal) used for a task other than that for which it was originally collected can be described as secondary data.

4. How to analyse secondary data

The process of analysing secondary data can be performed either quantitatively or qualitatively, depending on the kind of data the researcher is dealing with. The quantitative method of secondary data analysis is used on numerical data and is analyzed mathematically. The qualitative method uses words to provide in-depth information about data.

There are different stages of secondary data analysis, which involve events before, during, and after data collection. These stages include:

- Statement of purpose: Before collecting secondary data, you need to know your statement of purpose. This means you should have a clear awareness of the goal of the research work and how this data will help achieve it. This will guide you to collect the right data, then choosing the best data source and method of analysis.

- Research design: This is a plan on how the research activities will be carried out. It describes the kind of data to be collected, the sources of data collection, the method of data collection, tools used, and method of analysis. Once the purpose of the research has been identified, the researcher should design a research process that will guide the data analysis process.

- Developing the research questions: Once you’ve identified the research purpose, an analyst should also prepare research questions to help identify secondary data. For example, if a researcher is looking to learn more about why working adults are increasingly more interested in the “gig economy” as opposed to full-time work, they may ask, “What are the main factors that influence adults decisions to engage in freelance work?” or, “Does education level have an effect on how people engage in freelance work?

- Identifying secondary data: Using the research questions as a guide, researchers will then begin to identify relevant data from the sources provided. If the kind of data to be collected is qualitative, a researcher can filter out qualitative data—for example.

- Evaluating secondary data: Once relevant data has been identified and collates, it will be evaluated to ensure it fulfils the criteria of the research topic. Then, it is analyzed either using the quantitative or qualitative method, depending on the type of data it is.

You can learn more about secondary data analysis in this post .

5. Advantages of secondary data

Secondary data is suitable for any number of analytics activities. The only limitation is a dataset’s format, structure, and whether or not it relates to the topic or problem at hand.

When analyzing secondary data, the process has some minor differences, mainly in the preparation phase. Otherwise, it follows much the same path as any traditional data analytics project.

More broadly, though, what are the advantages and disadvantages of using secondary data? Let’s take a look.

Advantages of using secondary data

It’s an economic use of time and resources: Because secondary data have already been collected, cleaned, and stored, this saves analysts much of the hard work that comes from collecting these data firsthand. For instance, for qualitative data, the complex tasks of deciding on appropriate research questions or how best to record the answers have already been completed. Secondary data saves data analysts and data scientists from having to start from scratch.

It provides a unique, detailed picture of a population: Certain types of secondary data, especially government administrative data, can provide access to levels of detail that it would otherwise be extremely difficult (or impossible) for organizations to collect on their own. Data from public sources, for instance, can provide organizations and individuals with a far greater level of population detail than they could ever hope to gather in-house. You can also obtain data over larger intervals if you need it., e.g. stock market data which provides decades’-worth of information.

Secondary data can build useful relationships: Acquiring secondary data usually involves making connections with organizations and analysts in fields that share some common ground with your own. This opens the door to a cross-pollination of disciplinary knowledge. You never know what nuggets of information or additional data resources you might find by building these relationships.

Secondary data tend to be high-quality: Unlike some data sources, e.g. third-party data, secondary data tends to be in excellent shape. In general, secondary datasets have already been validated and therefore require minimal checking. Often, such as in the case of government data, datasets are also gathered and quality-assured by organizations with much more time and resources available. This further benefits the data quality , while benefiting smaller organizations that don’t have endless resources available.

It’s excellent for both data enrichment and informing primary data collection: Another benefit of secondary data is that they can be used to enhance and expand existing datasets. Secondary data can also inform primary data collection strategies. They can provide analysts or researchers with initial insights into the type of data they might want to collect themselves further down the line.

6. Disadvantages of secondary data

They aren’t always free: Sometimes, it’s unavoidable—you may have to pay for access to secondary data. However, while this can be a financial burden, in reality, the cost of purchasing a secondary dataset usually far outweighs the cost of having to plan for and collect the data firsthand.

The data isn’t always suited to the problem at hand: While secondary data may tick many boxes concerning its relevance to a business problem, this is not always true. For instance, secondary data collection might have been in a geographical location or time period ill-suited to your analysis. Because analysts were not present when the data were initially collected, this may also limit the insights they can extract.

The data may not be in the preferred format: Even when a dataset provides the necessary information, that doesn’t mean it’s appropriately stored. A basic example: numbers might be stored as categorical data rather than numerical data. Another issue is that there may be gaps in the data. Categories that are too vague may limit the information you can glean. For instance, a dataset of people’s hair color that is limited to ‘brown, blonde and other’ will tell you very little about people with auburn, black, white, or gray hair.

You can’t be sure how the data were collected: A structured, well-ordered secondary dataset may appear to be in good shape. However, it’s not always possible to know what issues might have occurred during data collection that will impact their quality. For instance, poor response rates will provide a limited view. While issues relating to data collection are sometimes made available alongside the datasets (e.g. for government data) this isn’t always the case. You should therefore treat secondary data with a reasonable degree of caution.

Being aware of these disadvantages is the first step towards mitigating them. While you should be aware of the risks associated with using secondary datasets, in general, the benefits far outweigh the drawbacks.

7. Wrap-up and further reading

In this post we’ve explored secondary data in detail. As we’ve seen, it’s not so different from other forms of data. What defines data as secondary data is how it is used rather than an inherent characteristic of the data themselves.

To learn more about data analytics, check out this free, five-day introductory data analytics short course . You can also check out these articles to learn more about the data analytics process:

- What is data cleaning and why is it important?

- What is data visualization? A complete introductory guide

- 10 Great places to find free datasets for your next project

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Employee Exit Interviews

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

Market Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Secondary Research

Try Qualtrics for free

Secondary research: definition, methods, & examples.

19 min read This ultimate guide to secondary research helps you understand changes in market trends, customers buying patterns and your competition using existing data sources.

In situations where you’re not involved in the data gathering process ( primary research ), you have to rely on existing information and data to arrive at specific research conclusions or outcomes. This approach is known as secondary research.

In this article, we’re going to explain what secondary research is, how it works, and share some examples of it in practice.

Free eBook: The ultimate guide to conducting market research

What is secondary research?

Secondary research, also known as desk research, is a research method that involves compiling existing data sourced from a variety of channels . This includes internal sources (e.g.in-house research) or, more commonly, external sources (such as government statistics, organizational bodies, and the internet).

Secondary research comes in several formats, such as published datasets, reports, and survey responses , and can also be sourced from websites, libraries, and museums.

The information is usually free — or available at a limited access cost — and gathered using surveys , telephone interviews, observation, face-to-face interviews, and more.

When using secondary research, researchers collect, verify, analyze and incorporate it to help them confirm research goals for the research period.

As well as the above, it can be used to review previous research into an area of interest. Researchers can look for patterns across data spanning several years and identify trends — or use it to verify early hypothesis statements and establish whether it’s worth continuing research into a prospective area.

How to conduct secondary research

There are five key steps to conducting secondary research effectively and efficiently:

1. Identify and define the research topic

First, understand what you will be researching and define the topic by thinking about the research questions you want to be answered.

Ask yourself: What is the point of conducting this research? Then, ask: What do we want to achieve?

This may indicate an exploratory reason (why something happened) or confirm a hypothesis. The answers may indicate ideas that need primary or secondary research (or a combination) to investigate them.

2. Find research and existing data sources

If secondary research is needed, think about where you might find the information. This helps you narrow down your secondary sources to those that help you answer your questions. What keywords do you need to use?

Which organizations are closely working on this topic already? Are there any competitors that you need to be aware of?

Create a list of the data sources, information, and people that could help you with your work.

3. Begin searching and collecting the existing data

Now that you have the list of data sources, start accessing the data and collect the information into an organized system. This may mean you start setting up research journal accounts or making telephone calls to book meetings with third-party research teams to verify the details around data results.

As you search and access information, remember to check the data’s date, the credibility of the source, the relevance of the material to your research topic, and the methodology used by the third-party researchers. Start small and as you gain results, investigate further in the areas that help your research’s aims.

4. Combine the data and compare the results

When you have your data in one place, you need to understand, filter, order, and combine it intelligently. Data may come in different formats where some data could be unusable, while other information may need to be deleted.

After this, you can start to look at different data sets to see what they tell you. You may find that you need to compare the same datasets over different periods for changes over time or compare different datasets to notice overlaps or trends. Ask yourself: What does this data mean to my research? Does it help or hinder my research?

5. Analyze your data and explore further

In this last stage of the process, look at the information you have and ask yourself if this answers your original questions for your research. Are there any gaps? Do you understand the information you’ve found? If you feel there is more to cover, repeat the steps and delve deeper into the topic so that you can get all the information you need.

If secondary research can’t provide these answers, consider supplementing your results with data gained from primary research. As you explore further, add to your knowledge and update your findings. This will help you present clear, credible information.

Primary vs secondary research

Unlike secondary research, primary research involves creating data first-hand by directly working with interviewees, target users, or a target market. Primary research focuses on the method for carrying out research, asking questions, and collecting data using approaches such as:

- Interviews (panel, face-to-face or over the phone)

- Questionnaires or surveys

- Focus groups

Using these methods, researchers can get in-depth, targeted responses to questions, making results more accurate and specific to their research goals. However, it does take time to do and administer.

Unlike primary research, secondary research uses existing data, which also includes published results from primary research. Researchers summarize the existing research and use the results to support their research goals.

Both primary and secondary research have their places. Primary research can support the findings found through secondary research (and fill knowledge gaps), while secondary research can be a starting point for further primary research. Because of this, these research methods are often combined for optimal research results that are accurate at both the micro and macro level.

Sources of Secondary Research

There are two types of secondary research sources: internal and external. Internal data refers to in-house data that can be gathered from the researcher’s organization. External data refers to data published outside of and not owned by the researcher’s organization.

Internal data

Internal data is a good first port of call for insights and knowledge, as you may already have relevant information stored in your systems. Because you own this information — and it won’t be available to other researchers — it can give you a competitive edge . Examples of internal data include:

- Database information on sales history and business goal conversions

- Information from website applications and mobile site data

- Customer-generated data on product and service efficiency and use

- Previous research results or supplemental research areas

- Previous campaign results

External data

External data is useful when you: 1) need information on a new topic, 2) want to fill in gaps in your knowledge, or 3) want data that breaks down a population or market for trend and pattern analysis. Examples of external data include:

- Government, non-government agencies, and trade body statistics

- Company reports and research

- Competitor research

- Public library collections

- Textbooks and research journals

- Media stories in newspapers

- Online journals and research sites

Three examples of secondary research methods in action

How and why might you conduct secondary research? Let’s look at a few examples:

1. Collecting factual information from the internet on a specific topic or market

There are plenty of sites that hold data for people to view and use in their research. For example, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, or Wiley Online Library all provide previous research on a particular topic. Researchers can create free accounts and use the search facilities to look into a topic by keyword, before following the instructions to download or export results for further analysis.

This can be useful for exploring a new market that your organization wants to consider entering. For instance, by viewing the U.S Census Bureau demographic data for that area, you can see what the demographics of your target audience are , and create compelling marketing campaigns accordingly.

2. Finding out the views of your target audience on a particular topic

If you’re interested in seeing the historical views on a particular topic, for example, attitudes to women’s rights in the US, you can turn to secondary sources.

Textbooks, news articles, reviews, and journal entries can all provide qualitative reports and interviews covering how people discussed women’s rights. There may be multimedia elements like video or documented posters of propaganda showing biased language usage.

By gathering this information, synthesizing it, and evaluating the language, who created it and when it was shared, you can create a timeline of how a topic was discussed over time.

3. When you want to know the latest thinking on a topic

Educational institutions, such as schools and colleges, create a lot of research-based reports on younger audiences or their academic specialisms. Dissertations from students also can be submitted to research journals, making these places useful places to see the latest insights from a new generation of academics.

Information can be requested — and sometimes academic institutions may want to collaborate and conduct research on your behalf. This can provide key primary data in areas that you want to research, as well as secondary data sources for your research.

Advantages of secondary research

There are several benefits of using secondary research, which we’ve outlined below:

- Easily and readily available data – There is an abundance of readily accessible data sources that have been pre-collected for use, in person at local libraries and online using the internet. This data is usually sorted by filters or can be exported into spreadsheet format, meaning that little technical expertise is needed to access and use the data.

- Faster research speeds – Since the data is already published and in the public arena, you don’t need to collect this information through primary research. This can make the research easier to do and faster, as you can get started with the data quickly.

- Low financial and time costs – Most secondary data sources can be accessed for free or at a small cost to the researcher, so the overall research costs are kept low. In addition, by saving on preliminary research, the time costs for the researcher are kept down as well.

- Secondary data can drive additional research actions – The insights gained can support future research activities (like conducting a follow-up survey or specifying future detailed research topics) or help add value to these activities.

- Secondary data can be useful pre-research insights – Secondary source data can provide pre-research insights and information on effects that can help resolve whether research should be conducted. It can also help highlight knowledge gaps, so subsequent research can consider this.

- Ability to scale up results – Secondary sources can include large datasets (like Census data results across several states) so research results can be scaled up quickly using large secondary data sources.

Disadvantages of secondary research

The disadvantages of secondary research are worth considering in advance of conducting research :

- Secondary research data can be out of date – Secondary sources can be updated regularly, but if you’re exploring the data between two updates, the data can be out of date. Researchers will need to consider whether the data available provides the right research coverage dates, so that insights are accurate and timely, or if the data needs to be updated. Also, fast-moving markets may find secondary data expires very quickly.

- Secondary research needs to be verified and interpreted – Where there’s a lot of data from one source, a researcher needs to review and analyze it. The data may need to be verified against other data sets or your hypotheses for accuracy and to ensure you’re using the right data for your research.

- The researcher has had no control over the secondary research – As the researcher has not been involved in the secondary research, invalid data can affect the results. It’s therefore vital that the methodology and controls are closely reviewed so that the data is collected in a systematic and error-free way.

- Secondary research data is not exclusive – As data sets are commonly available, there is no exclusivity and many researchers can use the same data. This can be problematic where researchers want to have exclusive rights over the research results and risk duplication of research in the future.

When do we conduct secondary research?

Now that you know the basics of secondary research, when do researchers normally conduct secondary research?

It’s often used at the beginning of research, when the researcher is trying to understand the current landscape . In addition, if the research area is new to the researcher, it can form crucial background context to help them understand what information exists already. This can plug knowledge gaps, supplement the researcher’s own learning or add to the research.

Secondary research can also be used in conjunction with primary research. Secondary research can become the formative research that helps pinpoint where further primary research is needed to find out specific information. It can also support or verify the findings from primary research.

You can use secondary research where high levels of control aren’t needed by the researcher, but a lot of knowledge on a topic is required from different angles.

Secondary research should not be used in place of primary research as both are very different and are used for various circumstances.

Questions to ask before conducting secondary research

Before you start your secondary research, ask yourself these questions:

- Is there similar internal data that we have created for a similar area in the past?

If your organization has past research, it’s best to review this work before starting a new project. The older work may provide you with the answers, and give you a starting dataset and context of how your organization approached the research before. However, be mindful that the work is probably out of date and view it with that note in mind. Read through and look for where this helps your research goals or where more work is needed.

- What am I trying to achieve with this research?

When you have clear goals, and understand what you need to achieve, you can look for the perfect type of secondary or primary research to support the aims. Different secondary research data will provide you with different information – for example, looking at news stories to tell you a breakdown of your market’s buying patterns won’t be as useful as internal or external data e-commerce and sales data sources.

- How credible will my research be?

If you are looking for credibility, you want to consider how accurate the research results will need to be, and if you can sacrifice credibility for speed by using secondary sources to get you started. Bear in mind which sources you choose — low-credibility data sites, like political party websites that are highly biased to favor their own party, would skew your results.

- What is the date of the secondary research?

When you’re looking to conduct research, you want the results to be as useful as possible , so using data that is 10 years old won’t be as accurate as using data that was created a year ago. Since a lot can change in a few years, note the date of your research and look for earlier data sets that can tell you a more recent picture of results. One caveat to this is using data collected over a long-term period for comparisons with earlier periods, which can tell you about the rate and direction of change.

- Can the data sources be verified? Does the information you have check out?

If you can’t verify the data by looking at the research methodology, speaking to the original team or cross-checking the facts with other research, it could be hard to be sure that the data is accurate. Think about whether you can use another source, or if it’s worth doing some supplementary primary research to replicate and verify results to help with this issue.

We created a front-to-back guide on conducting market research, The ultimate guide to conducting market research , so you can understand the research journey with confidence.

In it, you’ll learn more about:

- What effective market research looks like

- The use cases for market research

- The most important steps to conducting market research

- And how to take action on your research findings

Download the free guide for a clearer view on secondary research and other key research types for your business.

Related resources

Market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology