Literature Reviews: Types of Clinical Study Designs

- Library Basics

- 1. Choose Your Topic

- How to Find Books

- Types of Clinical Study Designs

- Types of Literature

- 3. Search the Literature

- 4. Read & Analyze the Literature

- 5. Write the Review

- Keeping Track of Information

- Style Guides

- Books, Tutorials & Examples

Types of Study Designs

Meta-Analysis A way of combining data from many different research studies. A meta-analysis is a statistical process that combines the findings from individual studies. Example : Anxiety outcomes after physical activity interventions: meta-analysis findings . Conn V. Nurs Res . 2010 May-Jun;59(3):224-31.

Systematic Review A summary of the clinical literature. A systematic review is a critical assessment and evaluation of all research studies that address a particular clinical issue. The researchers use an organized method of locating, assembling, and evaluating a body of literature on a particular topic using a set of specific criteria. A systematic review typically includes a description of the findings of the collection of research studies. The systematic review may also include a quantitative pooling of data, called a meta-analysis. Example : Complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Wanchai A, Armer JM, Stewart BR. Clin J Oncol Nurs . 2010 Aug;14(4):E45-55.

Randomized Controlled Trial A controlled clinical trial that randomly (by chance) assigns participants to two or more groups. There are various methods to randomize study participants to their groups. Example : Meditation or exercise for preventing acute respiratory infection: a randomized controlled trial . Barrett B, et al. Ann Fam Med . 2012 Jul-Aug;10(4):337-46.

Cohort Study (Prospective Observational Study) A clinical research study in which people who presently have a certain condition or receive a particular treatment are followed over time and compared with another group of people who are not affected by the condition. Example : Smokeless tobacco cessation in South Asian communities: a multi-centre prospective cohort study . Croucher R, et al. Addiction. 2012 Dec;107 Suppl 2:45-52.

Case-control Study Case-control studies begin with the outcomes and do not follow people over time. Researchers choose people with a particular result (the cases) and interview the groups or check their records to ascertain what different experiences they had. They compare the odds of having an experience with the outcome to the odds of having an experience without the outcome. Example : Non-use of bicycle helmets and risk of fatal head injury: a proportional mortality, case-control study . Persaud N, et al. CMAJ . 2012 Nov 20;184(17):E921-3.

Cross-sectional study The observation of a defined population at a single point in time or time interval. Exposure and outcome are determined simultaneously. Example : Fasting might not be necessary before lipid screening: a nationally representative cross-sectional study . Steiner MJ, et al. Pediatrics . 2011 Sep;128(3):463-70.

Case Reports and Series A report on a series of patients with an outcome of interest. No control group is involved. Example : Students mentoring students in a service-learning clinical supervision experience: an educational case report . Lattanzi JB, et al. Phys Ther . 2011 Oct;91(10):1513-24.

Ideas, Editorials, Opinions Put forth by experts in the field. Example : Health and health care for the 21st century: for all the people . Koop CE. Am J Public Health . 2006 Dec;96(12):2090-2.

Animal Research Studies Studies conducted using animal subjects. Example : Intranasal leptin reduces appetite and induces weight loss in rats with diet-induced obesity (DIO) . Schulz C, Paulus K, Jöhren O, Lehnert H. Endocrinology . 2012 Jan;153(1):143-53.

Test-tube Lab Research "Test tube" experiments conducted in a controlled laboratory setting.

Adapted from Study Designs. In NICHSR Introduction to Health Services Research: a Self-Study Course. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/nichsr/ihcm/06studies/studies03.html and Glossary of EBM Terms. http://www.cebm.utoronto.ca/glossary/index.htm#top

Study Design Terminology

Bias - Any deviation of results or inferences from the truth, or processes leading to such deviation. Bias can result from several sources: one-sided or systematic variations in measurement from the true value (systematic error); flaws in study design; deviation of inferences, interpretations, or analyses based on flawed data or data collection; etc. There is no sense of prejudice or subjectivity implied in the assessment of bias under these conditions.

Case Control Studies - Studies which start with the identification of persons with a disease of interest and a control (comparison, referent) group without the disease. The relationship of an attribute to the disease is examined by comparing diseased and non-diseased persons with regard to the frequency or levels of the attribute in each group.

Causality - The relating of causes to the effects they produce. Causes are termed necessary when they must always precede an effect and sufficient when they initiate or produce an effect. Any of several factors may be associated with the potential disease causation or outcome, including predisposing factors, enabling factors, precipitating factors, reinforcing factors, and risk factors.

Control Groups - Groups that serve as a standard for comparison in experimental studies. They are similar in relevant characteristics to the experimental group but do not receive the experimental intervention.

Controlled Clinical Trials - Clinical trials involving one or more test treatments, at least one control treatment, specified outcome measures for evaluating the studied intervention, and a bias-free method for assigning patients to the test treatment. The treatment may be drugs, devices, or procedures studied for diagnostic, therapeutic, or prophylactic effectiveness. Control measures include placebos, active medicines, no-treatment, dosage forms and regimens, historical comparisons, etc. When randomization using mathematical techniques, such as the use of a random numbers table, is employed to assign patients to test or control treatments, the trials are characterized as Randomized Controlled Trials.

Cost-Benefit Analysis - A method of comparing the cost of a program with its expected benefits in dollars (or other currency). The benefit-to-cost ratio is a measure of total return expected per unit of money spent. This analysis generally excludes consideration of factors that are not measured ultimately in economic terms. Cost effectiveness compares alternative ways to achieve a specific set of results.

Cross-Over Studies - Studies comparing two or more treatments or interventions in which the subjects or patients, upon completion of the course of one treatment, are switched to another. In the case of two treatments, A and B, half the subjects are randomly allocated to receive these in the order A, B and half to receive them in the order B, A. A criticism of this design is that effects of the first treatment may carry over into the period when the second is given.

Cross-Sectional Studies - Studies in which the presence or absence of disease or other health-related variables are determined in each member of the study population or in a representative sample at one particular time. This contrasts with LONGITUDINAL STUDIES which are followed over a period of time.

Double-Blind Method - A method of studying a drug or procedure in which both the subjects and investigators are kept unaware of who is actually getting which specific treatment.

Empirical Research - The study, based on direct observation, use of statistical records, interviews, or experimental methods, of actual practices or the actual impact of practices or policies.

Evaluation Studies - Works consisting of studies determining the effectiveness or utility of processes, personnel, and equipment.

Genome-Wide Association Study - An analysis comparing the allele frequencies of all available (or a whole genome representative set of) polymorphic markers in unrelated patients with a specific symptom or disease condition, and those of healthy controls to identify markers associated with a specific disease or condition.

Intention to Treat Analysis - Strategy for the analysis of Randomized Controlled Trial that compares patients in the groups to which they were originally randomly assigned.

Logistic Models - Statistical models which describe the relationship between a qualitative dependent variable (that is, one which can take only certain discrete values, such as the presence or absence of a disease) and an independent variable. A common application is in epidemiology for estimating an individual's risk (probability of a disease) as a function of a given risk factor.

Longitudinal Studies - Studies in which variables relating to an individual or group of individuals are assessed over a period of time.

Lost to Follow-Up - Study subjects in cohort studies whose outcomes are unknown e.g., because they could not or did not wish to attend follow-up visits.

Matched-Pair Analysis - A type of analysis in which subjects in a study group and a comparison group are made comparable with respect to extraneous factors by individually pairing study subjects with the comparison group subjects (e.g., age-matched controls).

Meta-Analysis - Works consisting of studies using a quantitative method of combining the results of independent studies (usually drawn from the published literature) and synthesizing summaries and conclusions which may be used to evaluate therapeutic effectiveness, plan new studies, etc. It is often an overview of clinical trials. It is usually called a meta-analysis by the author or sponsoring body and should be differentiated from reviews of literature.

Numbers Needed To Treat - Number of patients who need to be treated in order to prevent one additional bad outcome. It is the inverse of Absolute Risk Reduction.

Odds Ratio - The ratio of two odds. The exposure-odds ratio for case control data is the ratio of the odds in favor of exposure among cases to the odds in favor of exposure among noncases. The disease-odds ratio for a cohort or cross section is the ratio of the odds in favor of disease among the exposed to the odds in favor of disease among the unexposed. The prevalence-odds ratio refers to an odds ratio derived cross-sectionally from studies of prevalent cases.

Patient Selection - Criteria and standards used for the determination of the appropriateness of the inclusion of patients with specific conditions in proposed treatment plans and the criteria used for the inclusion of subjects in various clinical trials and other research protocols.

Predictive Value of Tests - In screening and diagnostic tests, the probability that a person with a positive test is a true positive (i.e., has the disease), is referred to as the predictive value of a positive test; whereas, the predictive value of a negative test is the probability that the person with a negative test does not have the disease. Predictive value is related to the sensitivity and specificity of the test.

Prospective Studies - Observation of a population for a sufficient number of persons over a sufficient number of years to generate incidence or mortality rates subsequent to the selection of the study group.

Qualitative Studies - Research that derives data from observation, interviews, or verbal interactions and focuses on the meanings and interpretations of the participants.

Quantitative Studies - Quantitative research is research that uses numerical analysis.

Random Allocation - A process involving chance used in therapeutic trials or other research endeavor for allocating experimental subjects, human or animal, between treatment and control groups, or among treatment groups. It may also apply to experiments on inanimate objects.

Randomized Controlled Trial - Clinical trials that involve at least one test treatment and one control treatment, concurrent enrollment and follow-up of the test- and control-treated groups, and in which the treatments to be administered are selected by a random process, such as the use of a random-numbers table.

Reproducibility of Results - The statistical reproducibility of measurements (often in a clinical context), including the testing of instrumentation or techniques to obtain reproducible results. The concept includes reproducibility of physiological measurements, which may be used to develop rules to assess probability or prognosis, or response to a stimulus; reproducibility of occurrence of a condition; and reproducibility of experimental results.

Retrospective Studies - Studies used to test etiologic hypotheses in which inferences about an exposure to putative causal factors are derived from data relating to characteristics of persons under study or to events or experiences in their past. The essential feature is that some of the persons under study have the disease or outcome of interest and their characteristics are compared with those of unaffected persons.

Sample Size - The number of units (persons, animals, patients, specified circumstances, etc.) in a population to be studied. The sample size should be big enough to have a high likelihood of detecting a true difference between two groups.

Sensitivity and Specificity - Binary classification measures to assess test results. Sensitivity or recall rate is the proportion of true positives. Specificity is the probability of correctly determining the absence of a condition.

Single-Blind Method - A method in which either the observer(s) or the subject(s) is kept ignorant of the group to which the subjects are assigned.

Time Factors - Elements of limited time intervals, contributing to particular results or situations.

Source: NLM MeSH Database

- << Previous: How to Find Books

- Next: Types of Literature >>

- Last Updated: Dec 29, 2023 11:41 AM

- URL: https://research.library.gsu.edu/litrev

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Research Methods and Design

- Action Research

- Case Study Design

Literature Review

- Quantitative Research Methods

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Mixed Methods Study

- Indigenous Research and Ethics This link opens in a new window

- Identifying Empirical Research Articles This link opens in a new window

- Research Ethics and Quality

- Data Literacy

- Get Help with Writing Assignments

A literature review is a discussion of the literature (aka. the "research" or "scholarship") surrounding a certain topic. A good literature review doesn't simply summarize the existing material, but provides thoughtful synthesis and analysis. The purpose of a literature review is to orient your own work within an existing body of knowledge. A literature review may be written as a standalone piece or be included in a larger body of work.

You can read more about literature reviews, what they entail, and how to write one, using the resources below.

Am I the only one struggling to write a literature review?

Dr. Zina O'Leary explains the misconceptions and struggles students often have with writing a literature review. She also provides step-by-step guidance on writing a persuasive literature review.

An Introduction to Literature Reviews

Dr. Eric Jensen, Professor of Sociology at the University of Warwick, and Dr. Charles Laurie, Director of Research at Verisk Maplecroft, explain how to write a literature review, and why researchers need to do so. Literature reviews can be stand-alone research or part of a larger project. They communicate the state of academic knowledge on a given topic, specifically detailing what is still unknown.

This is the first video in a whole series about literature reviews. You can find the rest of the series in our SAGE database, Research Methods:

Videos covering research methods and statistics

To login from SAGE, click Institution, then Access via Your Institution, then find and select City University of Seattle

Identify Themes and Gaps in Literature (with real examples) | Scribbr

Finding connections between sources is key to organizing the arguments and structure of a good literature review. In this video, you'll learn how to identify themes, debates, and gaps between sources, using examples from real papers.

4 Tips for Writing a Literature Review's Intro, Body, and Conclusion | Scribbr

While each review will be unique in its structure--based on both the existing body of both literature and the overall goals of your own paper, dissertation, or research--this video from Scribbr does a good job simplifying the goals of writing a literature review for those who are new to the process. In this video, you’ll learn what to include in each section, as well as 4 tips for the main body illustrated with an example.

- Literature Review This chapter in SAGE's Encyclopedia of Research Design describes the types of literature reviews and scientific standards for conducting literature reviews.

- UNC Writing Center: Literature Reviews This handout from the Writing Center at UNC will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

- Purdue OWL: Writing a Literature Review The overview of literature reviews comes from Purdue's Online Writing Lab. It explains the basic why, what, and how of writing a literature review.

Organizational Tools for Literature Reviews

One of the most daunting aspects of writing a literature review is organizing your research. There are a variety of strategies that you can use to help you in this task. We've highlighted just a few ways writers keep track of all that information! You can use a combination of these tools or come up with your own organizational process. The key is choosing something that works with your own learning style.

Citation Managers

Citation managers are great tools, in general, for organizing research, but can be especially helpful when writing a literature review. You can keep all of your research in one place, take notes, and organize your materials into different folders or categories. Read more about citations managers here:

- Manage Citations & Sources

Concept Mapping

Some writers use concept mapping (sometimes called flow or bubble charts or "mind maps") to help them visualize the ways in which the research they found connects.

There is no right or wrong way to make a concept map. There are a variety of online tools that can help you create a concept map or you can simply put pen to paper. To read more about concept mapping, take a look at the following help guides:

- Using Concept Maps From Williams College's guide, Literature Review: A Self-guided Tutorial

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix is is a chart you can use to help you organize your research into thematic categories. By organizing your research into a matrix, like the examples below, can help you visualize the ways in which your sources connect.

- Walden University Writing Center: Literature Review Matrix Find a variety of literature review matrix examples and templates from Walden University.

- Writing A Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix An example synthesis matrix created by NC State University Writing and Speaking Tutorial Service Tutors. If you would like a copy of this synthesis matrix in a different format, like a Word document, please ask a librarian. CC-BY-SA 3.0

- << Previous: Case Study Design

- Next: Quantitative Research Methods >>

- Last Updated: Feb 6, 2024 9:20 AM

CityU Home - CityU Catalog

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 4:07 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

- Library Guides

- Literature Reviews

- Getting Started

Literature Reviews: Getting Started

What is a literature review.

A literature review is an overview of the available research for a specific scientific topic. Literature reviews summarize existing research to answer a review question, provide context for new research, or identify important gaps in the existing body of literature.

An incredible amount of academic literature is published each year, by estimates over two million articles .

Sorting through and reviewing that literature can be complicated, so this Research Guide provides a structured approach to make the process more manageable.

THIS GUIDE IS AN OVERVIEW OF THE LITERATURE REVIEW PROCESS:

- Getting Started (asking a research question | defining scope)

- Choosing a Type of Review

- Searching the Literature

- Organizing the Literature

- Writing the Literature Review (analyzing | synthesizing)

A literature search is a systematic search of the scholarly sources in a particular discipline. A literature review is the analysis, critical evaluation and synthesis of the results of that search. During this process you will move from a review of the literature to a review for your research. Your synthesis of the literature is your unique contribution to research.

WHO IS THIS RESEARCH GUIDE FOR?

— those new to reviewing the literature

— those that need a refresher or a deeper understanding of writing literature reviews

You may need to do a literature review as a part of a course assignment, a capstone project, a master's thesis, a dissertation, or as part of a journal article. No matter the context, a literature review is an essential part of the research process.

Literature Review Process

Purpose of a Literature Review

What is the purpose of a literature review.

A literature review is typically performed for a specific reason. Even when assigned as an assignment, the goal of the literature review will be one or more of the following:

- To communicate a project's novelty by identifying a research gap

- An overview of research issues , methodologies or results relevant to field

- To explore the volume and types of available studies

- To establish familiarity with current research before carrying out a new project

- To resolve conflicts amongst contradictory previous studies

Reviewing the literature helps you understand a research topic and develop your own perspective.

A LITERATURE REVIEW IS NOT :

- An annotated bibliography – which is a list of annotated citations to books, articles and documents that includes a brief description and evaluation for each entry

- A literary review – which is a critical discussion of the merits and weaknesses of a literary work

- A book review – which is a critical discussion of the merits and weaknesses of a particular book

Attribution

Thanks to Librarian Jamie Niehof at the University of Michigan for providing permission to reuse and remix this Literature Reviews guide.

The Library's Subject Specialists are happy to help with your literature reviews! Find your Subject Specialist here .

If you have questions about this guide, contact Librarians Matt Upson ([email protected]), Dr. Frances Alvarado-Albertorio ([email protected]), or Clarke Iakovakis ([email protected])

- Last Updated: Apr 4, 2024 4:51 PM

- URL: https://info.library.okstate.edu/literaturereviews

Study Design 101: Systematic Review

- Case Report

- Case Control Study

- Cohort Study

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- Practice Guideline

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Helpful Formulas

- Finding Specific Study Types

A document often written by a panel that provides a comprehensive review of all relevant studies on a particular clinical or health-related topic/question. The systematic review is created after reviewing and combining all the information from both published and unpublished studies (focusing on clinical trials of similar treatments) and then summarizing the findings.

- Exhaustive review of the current literature and other sources (unpublished studies, ongoing research)

- Less costly to review prior studies than to create a new study

- Less time required than conducting a new study

- Results can be generalized and extrapolated into the general population more broadly than individual studies

- More reliable and accurate than individual studies

- Considered an evidence-based resource

Disadvantages

- Very time-consuming

- May not be easy to combine studies

Design pitfalls to look out for

Studies included in systematic reviews may be of varying study designs, but should collectively be studying the same outcome.

Is each study included in the review studying the same variables?

Some reviews may group and analyze studies by variables such as age and gender; factors that were not allocated to participants.

Do the analyses in the systematic review fit the variables being studied in the original studies?

Fictitious Example

Does the regular wearing of ultraviolet-blocking sunscreen prevent melanoma? An exhaustive literature search was conducted, resulting in 54 studies on sunscreen and melanoma. Each study was then evaluated to determine whether the study focused specifically on ultraviolet-blocking sunscreen and melanoma prevention; 30 of the 54 studies were retained. The thirty studies were reviewed and showed a strong positive relationship between daily wearing of sunscreen and a reduced diagnosis of melanoma.

Real-life Examples

Yang, J., Chen, J., Yang, M., Yu, S., Ying, L., Liu, G., ... Liang, F. (2018). Acupuncture for hypertension. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11 (11), CD008821. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008821.pub2

This systematic review analyzed twenty-two randomized controlled trials to determine whether acupuncture is a safe and effective way to lower blood pressure in adults with primary hypertension. Due to the low quality of evidence in these studies and lack of blinding, it is not possible to link any short-term decrease in blood pressure to the use of acupuncture. Additional research is needed to determine if there is an effect due to acupuncture that lasts at least seven days.

Parker, H.W. and Vadiveloo, M.K. (2019). Diet quality of vegetarian diets compared with nonvegetarian diets: a systematic review. Nutrition Reviews , https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuy067

This systematic review was interested in comparing the diet quality of vegetarian and non-vegetarian diets. Twelve studies were included. Vegetarians more closely met recommendations for total fruit, whole grains, seafood and plant protein, and sodium intake. In nine of the twelve studies, vegetarians had higher overall diet quality compared to non-vegetarians. These findings may explain better health outcomes in vegetarians, but additional research is needed to remove any possible confounding variables.

Related Terms

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

A highly-regarded database of systematic reviews prepared by The Cochrane Collaboration , an international group of individuals and institutions who review and analyze the published literature.

Exclusion Criteria

The set of conditions that characterize some individuals which result in being excluded in the study (i.e. other health conditions, taking specific medications, etc.). Since systematic reviews seek to include all relevant studies, exclusion criteria are not generally utilized in this situation.

Inclusion Criteria

The set of conditions that studies must meet to be included in the review (or for individual studies - the set of conditions that participants must meet to be included in the study; often comprises age, gender, disease type and status, etc.).

Now test yourself!

1. Systematic Reviews are similar to Meta-Analyses, except they do not include a statistical analysis quantitatively combining all the studies.

a) True b) False

2. The panels writing Systematic Reviews may include which of the following publication types in their review?

a) Published studies b) Unpublished studies c) Cohort studies d) Randomized Controlled Trials e) All of the above

Evidence Pyramid - Navigation

- Meta- Analysis

- Case Reports

- << Previous: Practice Guideline

- Next: Meta-Analysis >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 10:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/studydesign101

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

- Open access

- Published: 06 December 2022

What improves access to primary healthcare services in rural communities? A systematic review

- Zemichael Gizaw 1 ,

- Tigist Astale 2 &

- Getnet Mitike Kassie 2

BMC Primary Care volume 23 , Article number: 313 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

9 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

To compile key strategies from the international experiences to improve access to primary healthcare (PHC) services in rural communities. Different innovative approaches have been practiced in different parts of the world to improve access to essential healthcare services in rural communities. Systematically collecting and combining best experiences all over the world is important to suggest effective strategies to improve access to healthcare in developing countries. Accordingly, this systematic review of literature was undertaken to identify key approaches from international experiences to enhance access to PHC services in rural communities.

All published and unpublished qualitative and/or mixed method studies conducted to improvement access to PHC services were searched from MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, WHO Global Health Library, and Google Scholar. Articles published other than English language, citations with no abstracts and/or full texts, and duplicate studies were excluded. We included all articles available in different electronic databases regardless of their publication years. We assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 to minimize the risk of bias. Data were extracted using JBI mixed methods data extraction form. Data were qualitatively analyzed using emergent thematic analysis approach to identify key concepts and coded them into related non-mutually exclusive themes.

Our analysis of 110 full-text articles resulted in ten key strategies to improve access to PHC services. Community health programs or community-directed interventions, school-based healthcare services, student-led healthcare services, outreach services or mobile clinics, family health program, empanelment, community health funding schemes, telemedicine, working with traditional healers, working with non-profit private sectors and non-governmental organizations including faith-based organizations are the key strategies identified from international experiences.

This review identified key strategies from international experiences to improve access to PHC services in rural communities. These strategies can play roles in achieving universal health coverage and reducing disparities in health outcomes among rural communities and enabling them to get healthcare when and where they want.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Universal health coverage (UHC) is used to provide expanding services to eliminate access barriers. Universal health coverage is defined by the world health organization (WHO) as access to key promotional, preventive, curative and rehabilitative health services for all at an affordable rate and ensuring equity in access. The term universal has been described as the State's legal obligation to provide healthcare to all its citizens, with particular attention to ensuring that all poor and excluded groups are included [ 1 , 2 , 3 ].

Strengthening primary healthcare (PHC) is the most comprehensive, reliable and productive approach to improving people's physical and mental wellbeing and social well-being, and that PHC is a pillar of a sustainable health system for UHC and health-related sustainable development goals [ 4 , 5 ]. Despite tremendous progress over the last decades, there are still unaddressed health needs of people in all parts of the world [ 6 , 7 ]. Many people, particularly the poor and people living in rural areas and those who are in vulnerable circumstances, face challenges to remain healthy [ 8 ].

Geographical and financial inaccessibility, inadequate funding, inconsistent medication supply and equipment and personnel shortages have left the reach, availability and effect of PHC services in many countries disappointingly limited [ 9 , 10 ]. A recent Astana Declaration recognized those aspects of PHC need to be changed to adapt adequately to current and emerging threats to the healthcare system. This declaration discussed that implementation of a need-based, comprehensive, cost-effective, accessible, efficient and sustainable healthcare system is needed for disadvantaged and rural populations in more local and convenient settings to provide care when and where they want it [ 8 ].

Different innovative approaches have been practiced in different parts of the world to improve access to essential healthcare services in rural communities. Systematically collecting and combining best experiences all over the world is important to suggest effective strategies to improve access to healthcare in developing countries. Accordingly, this systematic review of literature was undertaken to identify key approaches from international experiences to enhance access to PHC services in rural communities. The findings of this systematic literature review can be used by healthcare professionals, researchers and policy makers to improve healthcare service delivery in rural communities.

Methodology

Research question.

What improves access to PHC services in rural communities? We used the PICO (population, issue/intervention, comparison/contrast, and outcome) construct to develop the search question [ 11 ]. The population is rural communities or remote communities in developing countries who have limited access to healthcare services. Moreover, we extended the population to developed countries to capture experiences of both developing and developed countries. The issue/intervention is implementation of different community-based health interventions to access to essential healthcare services. In this systematic review, we focused on PHC health services, mainly essential or basic healthcare services, community or public health services, and health promotion or health education. Primary healthcare is “a health care system that addressed social, economic, and political causes of poor health promotes health though health services at the primary care level enhances health of the community” [ 12 ]. Comparison/contrast is not appropriate for this review. The outcome is improved access to essential healthcare services.

Outcome measures

The outcome of this review is access to PHC services, such as preventive, promotive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative health services which are affordable, convenient or acceptable, and available to all who need care.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

All published and unpublished qualitative and/or mixed method studies conducted to improve access to PHC services were included. Government and international or national organizations reports were also included. Different organizations whose primary mission is health or promotion of community health were selected. We included articles based on these eligibility criteria: context or scope of studies (access to PHC services), article type (primary studies), and publication language (English). Articles published other than English language, citations with no abstracts and/or full texts, reviews, and duplicate studies were excluded. We included all articles available in different electronic databases regardless of their publication years. We didn’t use time of publication for screening.

Information sources and search strategy

We searched relevant articles from MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, WHO Global Health Library, and Google Scholar to access all forms of evidence. An initial search of MEDLINE was undertaken followed by analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract, and of the index terms used to describe articles. We used the aforementioned performance indicators of PHC delivery and the PICO as we described above to choose keywords. A second search using all identified keywords and index terms was undertaken across all included databases. Thirdly, references of all identified articles were searched to get additional studies. The full electronic search strategy for MEDLINE, a major database we used for this review is included as a supplementary file (Additional file 1 : Appendix 1).

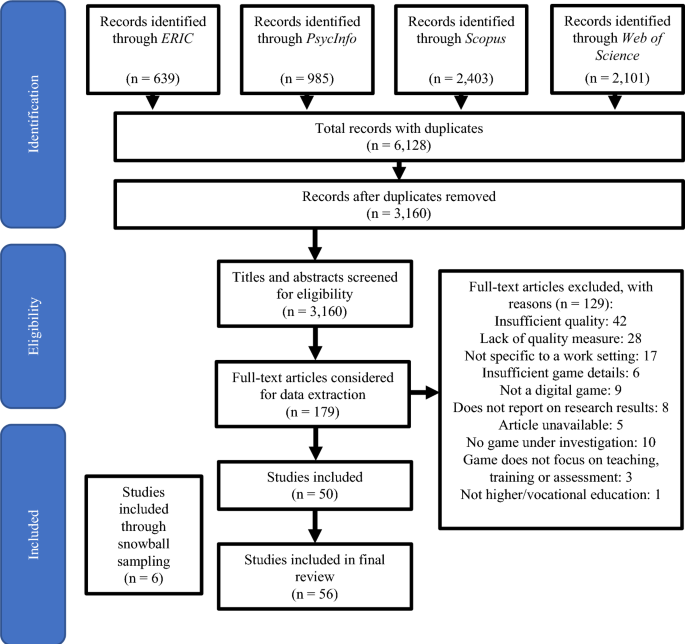

Study selection and assessment of methodological quality

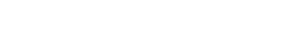

Search results from different electronic databases were exported to Endnote reference manager version 7 to remove duplication. Two independent reviewers (ZG and BA) screened out records. An initial screening of titles and abstracts was done based on the PICO criteria and language of publication. Secondary screening of full-text papers was done for studies we included at the initial screening phase. We further investigated and assessed records included in the full-text articles against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We sat together and discussed the eligibility assessment. The interrater agreement was 90%. We resolved disagreements by consensus for points we had different rating. We used the PRISMA flow diagram to summarize the study selection processes.

Methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 [ 13 ]. As it is clearly indicated in the user guide of the MMAT tool, it is discouraged to calculate an overall score from the ratings of each criterion. Instead, it is advised to provide a more detailed presentation of the ratings of each criterion to better inform quality of the included studies. The rating of each criterion was, therefore, done as per the detail explanations included in the guideline. Almost all the included full text articles fulfilled the criteria and all the included full text articles were found to be better quality.

Data extraction

We independently extracted data from papers included in the review using JBI mixed methods data extraction form. This form is only used for reviews that follow a convergent integrated approach, i.e. integration of qualitative data and qualitative data [ 14 ]. The data extraction form was piloted on randomly selected papers and modified accordingly. One reviewer extracted the data from the included studies and the second reviewer checked the extracted data. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers. Information was extracted from each included study on: list of authors, year of publication, study area, population of interest, study type, methods, focus of the studies, main findings, authors’ conclusion, and limitations of the study.

Synthesis of findings

The included full-text articles were qualitatively analyzed using emergent thematic analysis approach to identify key concepts and coded them into related non-mutually exclusive themes. Themes are strategies mentioned or discussed in the included records to improve access to PHC services. Themes were identified manually by reading the included records again and again. We then synthesized each theme by comparing the discussion and conclusion of the included articles.

Systematic review registration number

The protocol of this review is registered in PROSPERO (the registration number is: CRD42019132592) to avoid unplanned duplication and to enable comparison of reported review methods with what was planned in the protocol. It is available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42019132592 .

Schematic of the systematic review and reporting of the search

We used PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2009 checklist [ 15 ] for reporting of this systematic review.

Study selection

The search strategy identified 1148 titles and abstracts [914 from PubMed (Table 1 ) and 234 from other sources] as of 10 March 2022. We obtained 900 after we removed duplicated articles. Following assessment by title and abstract, 485 records were excluded because these records did not meet the criteria as mentioned in the method section. Additional 256 records were discarded because the records did not discuss the outcome of interest well and some records were systematic reviews. The full text of the remaining 159 records was examined in more detail. It appeared that 49 studies did not meet the inclusion criteria as described in the method section. One hundred ten records met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review or synthesis (Fig. 1 ).

Study selection flow diagram

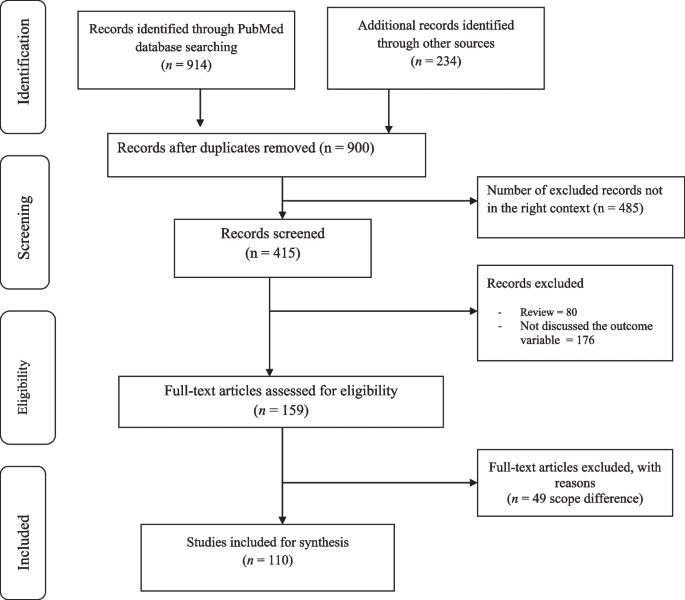

Of 900 articles resulting from the search term, 110 (12.2%) met the inclusion criteria. The included full-text articles were published between 1993 and 2021. Ninety-two (83.6%) of the included full-text articles were research articles, 5(4.5%) were technical reports, 3 (2.7%) were perspective, 4 (3.6%) was discussion paper, 3(2.7%) were dissertation or thesis, 2 (1.8%) were commentary, and 1 (0.9) was a book. Thirty-six (33%) and 29 (26%) of the included full-text articles were conducted in Africa and North America, respectively (Fig. 2 ).

Regions where the included full-test articles conducted

Key strategies identified

The analysis of 110 full-text articles resulted in 10 themes. The themes are key strategies to improve access to PHC services in rural communities. The key strategies identified are community health programs or community-directed healthcare interventions, school-based healthcare services, student-led healthcare services, outreach services or mobile clinics, family health program, empanelment, community health funding schemes, telemedicine, promoting the role of traditional medicine, working with non-profit private sectors and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) including faith-based organizations (Table 2 ).

Description of strategies

a. Community health programs or community-directed healthcare interventions