- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About Research Evaluation

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. research excellence framework and related literature, 3. methodology, 5. conclusions, acknowledgements, assessing research excellence: evaluating the research excellence framework.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Mehmet Pinar, Timothy J Horne, Assessing research excellence: Evaluating the Research Excellence Framework, Research Evaluation , Volume 31, Issue 2, April 2022, Pages 173–187, https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvab042

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Performance-based research funding systems have been extensively used around the globe to allocate funds across higher education institutes (HEIs), which led to an increased amount of literature examining their use. The UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF) uses a peer-review process to evaluate the research environment, research outputs and non-academic impact of research produced by HEIs to produce a more accountable distribution of public funds. However, carrying out such a research evaluation is costly. Given the cost and that it is suggested that the evaluation of each component is subject to bias and has received other criticisms, this article uses correlation and principal component analysis to evaluate REF’s usefulness as a composite evaluation index. As the three elements of the evaluation—environment, impact and output—are highly and positively correlated, the effect of the removal of an element from the evaluation leads to relatively small shifts in the allocation of funds and in the rankings of HEIs. As a result, future evaluations may consider the removal of some elements of the REF or reconsider a new way of evaluating different elements to capture organizational achievement rather than individual achievements.

Performance-based research funding systems (PRFS) have multiplied since the United Kingdom introduced the first ‘Research Selectivity Exercise’ in 1986. Thirty years on from this first exercise, Jonkers and Zacharewicz (2016) reported that 17 of the EU28 countries had some form of PRFS, and this had increased to 18 by 2019 ( Zacharewicz et al. 2019 ).

A widely used definition of what constitutes a PRFS is that they must meet the following criteria ( Hicks 2012 ):

Research must be evaluated, not the quality of teaching and degree programmes;

The evaluation must be ex post, and must not be an ex ante evaluation of a research or project proposal;

The output(s) of research must be evaluated;

The distribution of funding from Government must depend upon the evaluation results;

The system must be national.

Within these relatively narrow boundaries, there is significant variation between both what is assessed in different PRFS, and how the assessment is made. With regards to ‘what’, some focus almost exclusively on research outputs, predominantly journal articles, whereas others, notably the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF), assess other aspects of research such as the impact of research and the research environment. With regards to ‘how’, some PRFS use exclusively or predominantly metrics such as citations whereas others use expert peer review, and others still a mix of both methods ( Zacharewicz et al. 2019 ). 1

This article focuses on UK’s REF, which originated in the very first PRFS, the Research Selectivity Exercise in 1986. This was followed by a second exercise in 1989 and a series of Research Assessment Exercises (RAEs) in the 1990s and 2000s. Each RAE represented a relatively gentle evolution from the previous one, but there was arguably more of a revolution than evolution between the last RAE in 2008 and the first REF in 2014 ( REF 2014 ), with the introduction of the assessment of research impact into the assessment framework (see e.g., Gilroy and McNamara 2009 ; Shattock 2012 ; Marques et al. 2017 for a detailed discussion on the evolution of RAEs in the UK). Three elements of research, namely research outputs, the non-academic impact of research and the research environment, were evaluated in the REF 2014 exercise. Research outputs (e.g., journal articles, books and research-based artistic works) were evaluated in terms of their ‘originality, significance and rigour’. The assessment of the non-academic impact of research is based on the submission of impact case studies that describe the details of the ‘reach and significance’ of impacts on the economy, society and/or culture, that were underpinned by excellent research. The research environment consisted of both data relating to the environment and a narrative environment statement. The environment data consisted of the number of postgraduate research degree completions and total research income generated by the submitting unit. The research environment statement provided information on the research undertaken, the staffing strategy, infrastructure and facilities, staff development activities, and research collaborations and contribution to the discipline. The quality of the research environment was assessed in terms of its ‘vitality and sustainability’ based on the environment data and narrative environment statements (see REF 2012 for further details).

There has been criticism of several aspects of the assessment of research excellence in the REF, including the cost of preparation and evaluation of the REF, the potential lack of objectivity in assessing them and the effect of the quasi-arbitrary or opaque value judgements on the allocation of quality-related research (QR) funding (see Section 2 for the details). Furthermore, the use of multiple criteria, which is the case for the REF (i.e., environment, impact and outputs), in assessing university performance has been long criticized (see e.g., Saisana, d’Hombres and Saltelli 2011 ; Pinar, Milla and Stengos 2019 ). These multidimensional indices are risky as some of the index components have been considered redundant ( McGillivray 1991 ; McGillivray and White 1993 ). For instance, McGillivray (1991) , McGillivray and White (1993) and Bérenger and Verdier-Chouchane (2007) use correlation analysis to examine the redundancy of different components of well-being when the indices are constructed. The main argument of these papers is that if the index components are highly and positively correlated, then the inclusion of additional dimensions to the index does not add new information to that provided by any of the other components. Furthermore, Nardo et al. (2008) also point out that obtaining a composite index with the highly correlated components leads to a double weighting of the same information and so overweighting of the information captured by these components. Therefore, this literature argues that excluding any component from the evaluation does not lead to loss of information if the evaluation elements are highly and positively correlated. For instance, by using correlation analysis, Cahill (2005) showed that excluding any component from a composite index produces rankings and achievements similar to the composite index. To overcome these drawbacks, principal components analysis (PCA) has been used to obtain indices (see e.g., McGillivray 2005 ; Khatun 2009 ; Nguefack‐Tsague, Klasen and Zucchini 2011 for the use of PCA for well-being indices, and see Tijssen, Yegros-Yegros and Winnink 2016 and Robinson-Garcia et al. 2019 for the use of PCA for university rankings). The PCA transforms the correlated variables into a new set of uncorrelated variables using a covariance matrix, which explains most of the variation in the existing components ( Nardo et al. 2008 ).

This article will contribute to the literature by examining the redundancy of the three components of the REF by using the correlation analysis between them to examine the relevance of each component for the evaluation. If the three elements of the REF are highly and positively correlated, then excluding one component from the analysis will not result in major changes in the overall assessment of universities and funding allocated to them. This article will examine whether this would be the case. Furthermore, we will also carry out PCA to obtain weights that would produce an index that explains most of the variation in the three elements of the REF while obtaining an overall assessment of higher education institutes (HEIs) and distributing funding across them.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In Section 2, we will provide details on how the UK’s REF operates, identify the literature on the REF exercise and outline the hypotheses of the article. In Section 3, we provide the detailed data used in this article and examine the correlation between the environment, impact and output scores. In this section, we also provide the details of the QR funding formula used to allocate the funding and demonstrate the correlation between the funding distribution in the environment, impact and output pots. We also will carry out PCA by using the achievement scores and funding distributed in each element in this section. Finally, in this section, we provide an alternative approach to the calculation of overall REF scores and the distribution of QR funding based on the hypotheses of the article. Section 4 will consider the effect on the distribution of QR funding for English universities 2 and their rankings when each element is removed from the calculation one at a time and PCA weights are used. Finally, Section 5 will identify conclusions of our analyses and the implications for how future REF assessment exercises might be structured.

Research assessment exercises have existed in the UK since the first Research Selectivity Exercise was undertaken in 1986. A subsequent exercise was held in 1989, which was followed by RAEs in 1996, 2001 and 2008. Each HEI’s submission to the 1986 exercise comprised a research statement in one or more of 37 subject areas, together with five research outputs per area in which a submission was made (see e.g., Hinze et al. 2019 ). The complexity of the submissions has increased from that first exercise, and in 2014 the requirement to submit case studies and a narrative template to allow for the assessment of research impact was included for the first time, and the exercise was renamed to the REF.

The REF 2014 ‘Assessment Framework and Guidance on Submissions’ (REF 2011) indicated that a submission’s research environment would be assessed according to its ‘vitality and sustainability’, using the same five-point (4* down to unclassified) scale as for the other elements of the exercise. 3

Following the 2014 REF exercise, there have been many criticisms of REF. For instance, the effects of the introduction of impact as an element of the UK’s research assessment methodology has itself been the subject of many papers and reports in which many of the issues and challenges it has brought have been discussed (see e.g., Smith and Ward, House 2011 ; Penfield et al. 2014 ; Manville et al. 2015 ; Watermeyer 2016 ; Pinar and Unlu 2020a ). Manville et al. (2015) and Watermeyer (2016) show that academics in some fields were concerned about how their research focus would be affected by the impact agenda by forcing them to produce more ‘impactful’ research than carrying out their own research agenda. On the other hand, Manville et al. (2015 ) demonstrate that there have been problems with the peer reviewing of the impact case studies where reviewer panels struggled to distinguish between 2-star and 3-star and, most importantly, between 3-star and 4-star. Furthermore, Pinar and Unlu (2020a ) demonstrate that the inclusion of the impact agenda in REF 2014 increased the research income gap across HEIs. Similarly, the literature identifies some serious concerns with the assessment of the research environment ( Taylor 2011 ; Wilsdon et al. 2015 ; Thorpe et al. 2018a , b ). Taylor (2011) considered the use of metrics to assess the research environment, and found evidence of bias towards more research-intensive universities in the assessment of research environment in the 2008 RAE (see Pinar and Unlu 2020b for similar findings for the REF 2014). In particular, he argued that the judgement of assessors may have an implicit bias and be influenced by the ‘halo effect’, where assessors allocate relatively higher scores to departments with long-standing records of high-quality research, and showed that members of Russell Group universities benefited from a ‘halo effect’, after accounting for various important quantitative factors. Wilsdon et al. (2015) wrote in a report for the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), which ran the REF on behalf of the four countries of the UK, in which those who had reviewed the narrative research environment statements in REF 2014 as members of the panels of experts expressed concerns ‘that the narrative elements were hard to assess, with difficulties in separating quality in research environment from quality in writing about it.’ Thorpe et al. (2018a , b ) examined environment statements submitted to REF 2014, and their work indicates that the scores given to the overall research environment were influenced by the language used in the narrative statements, and whether or not the submitting university was represented amongst those experts who reviewed the statements. Finally, a similar peer-review bias has been identified in the evaluation of research outputs (see e.g., Taylor 2011 ). Overall, there have been criticisms about the evaluation biases in each element of the REF exercise.

Another criticism of the REF 2014 exercise has been that of the cost. HEFCE commissioned a review of it ( Farla and Simmonds 2015 ) which estimated the cost of the exercise to be £246 million ( Farla and Simmonds 2015 , 6), and the cost of preparing the REF submissions was £212 million. It can be estimated that roughly £19–27 million was spent preparing the research environment statements, 4 and £55 million was spent in preparation of impact case studies, and the remainder cost of preparation may be associated with the output submission. Overall, the cost of preparing each element was significant. Since there is a good agreement between bibliometric factors and peer review assessments ( Bertocchi et al. 2015 ; Pidd and Broadbent 2015 ), it has been argued that cost of evaluating outputs could be decreased with the use of bibliometric information (see e.g., De Boer et al. 2015 ; Geuna and Piolatto 2016 ). Furthermore, Pinar and Unlu (2020b ) found that the use of ‘environment data’ alone could minimize the cost of preparation of the environment part of the assessment as the environment data (i.e., income generated by units, number of staff and postgraduate degree completions) explains a good percentage of the variation between HEIs in REF environment scores.

Because of these criticisms, together with Kelly (2016) and Pinar (2020 )’s works which show that a key outcome of the REF, which is to distribute ca. £1bn per annum of QR funding, is dependent upon somewhat arbitrary or opaque value judgements (e.g., the relative importance of world-leading research compared to internationally excellent research and the relative cost of undertaking research in different disciplines). In this article, we will contribute to the existing literature by using correlation analysis to examine the redundancy of each research element, and also use PCA to obtain weights for each element that overcome high correlation between three elements but explain most of the variation in achievements and funding distribution in each element.

The three components of the REF are highly and positively correlated (see next section for correlation analysis), and a high and positive correlation amongst the three components would suggest that removal of one component from the REF would have only a small effect on the QR funding distribution and overall performance rankings based on the redundancy literature (e.g., McGillivray 1991 ; McGillivray and White 1993 ; Bérenger and Verdier-Chouchane 2007 ). Therefore, based on the arguments put forward in the redundancy literature, we set the hypotheses of this article as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Exclusion of one of the REF elements from the distribution of the mainstream QR funding would lead to relatively small shifts in the allocation of funds if three components of the REF elements are positively and highly correlated. Hypothesis 2: Exclusion of one of the REF elements from the calculation of overall REF grade point averages (GPAs) obtained by HEIs would result in relatively small shifts in the rankings of HEIs when REF elements are positively and highly correlated. Hypothesis 3: Overall REF GPAs and allocation of funding with the PCA weights given to each element of REF would result in small shifts in rankings and funding allocation when three components of the REF are highly and positively correlated.

In this section, we will provide the details of the data sources for the REF results and QR funding allocation based on the REF results. We will also discuss the alternative ways of obtaining overall REF scores and QR funding allocation.

3.1 REF results data

In REF 2014, each participating UK institution submitted in one or more disciplinary areas, known as ‘units of assessment’ (UOAs). Each submission comprised three elements:

A number of research outputs. The expected number of research outputs submitted by each UOA was four times the full-time equivalent (FTE) staff included in that submission, unless one or more staff members was allowed a reduction in outputs. Each FTE staff member was expected to submit four research outputs, but reductions in outputs were allowed for staff members who had individual circumstances which included that they were early career researchers, had taken maternity, paternity or adoption leave during the assessment period, or had had health problems.

A number of case studies demonstrating the impact of research undertaken within that UOA, and a narrative ‘impact template’ which included a description of the UOA’s approach to generating impact from its research. Each case study was a maximum of four pages and the rules stipulated that the number of case studies required depended upon the number of FTEs submitted in the UOA, as was the length of the impact template. Ninety-five per cent of submissions by English universities comprised between two and seven case studies and narratives that were three or four pages long. 5

Information about the research environment, which comprised a narrative ‘environment statement’ describing the research environment, together with data on research income and PhD completions. As with the impact narrative the length of the environment statement was dependent upon the number of FTEs submitted, with 95% of submission from English universities comprising narratives which were between 7 and 12 pages long.

After the submission of UOAs, each individual component in these elements (e.g., a research output, an impact case study) was given a score on a five-point ‘star’ scale, namely 4* (world-leading), 3* (internationally excellent), 2* (internationally recognized), 1* (nationally recognized) and unclassified (for elements which were below the 1* standard) by the peer-reviewers. From the scores for each individual component in each element, a profile for each element was obtained and this was the information which was released by HEFCE. This profile for each element, obtained from REF (2014) gives the percentage of the research in each element (i.e., research outputs, environment and impact) that were rated as 4*, 3*, 2*, 1* or unclassified. Finally, an overall research profile of the UOA is calculated where each element’s score was weighted 65:20:15 for outputs: impact: environment.

To test whether the quality of the research environment, impact and outputs are correlated, we obtain each individual submissions’ weighted average environment, impact and output scores. 6 Table 1 provides a correlation matrix between GPA scores of different elements. This table shows that GPA scores are positively and significantly correlated with each other at the 1% level. Table 2 shows the results of PCA of the three elements when GPA scores in each element are used. The first principal component accounts for approximately 79.0% of the variation in three elements. In comparison, the first two principal components account for approximately 92.5% of the variation in three elements. Clearly, the first principal component contains most of the statistical information embedded in the three elements. Second, the first principal component results in roughly similar eigenvectors, suggesting that the overall GPA scores could be obtained using roughly equal weights given to each element when the eigenvectors are normalized to sum the weights to 1.

Correlation matrix between different element GPAs

Note: Asterisk (*) represents a significance level at the 1% level.

Results of PCA of the three elements using GPA scores

Since all the elements are positively and significantly correlated with each other, removing one of the elements from the REF assessment or an alternative combination of the REF elements (via PCA weights) might have a little overall effect on the distribution of QR income and overall achievement.

3.2 QR funding allocation data based on REF results

Based on the REF results obtained by UOAs, Research England describes how it distributes QR funding in Research England (2019a) . In brief, QR funding comprises six elements: (1) mainstream QR funding; (2) QR research degree programme supervision fund; (3) QR charity support fund; (4) QR business research element; (5) QR funding for National Research Libraries; and (6) the Global Challenge Research Fund. The mainstream QR funding is the largest, comprising approximately two-thirds of the overall QR funding, and is the element which is most directly related to an institution’s performance in REF 2014. The data for the mainstream QR funding allocations across panels, UOAs and HEIs during the 2019–20 funding period are obtained from Research England (2019b) .

In calculating an institution’s mainstream QR funding, Research England follows a four-stage process:

The mainstream QR funding is separated into three elements, for outputs, impact and environment, with 65% of funding for outputs, 20% for impact and 15% for environment.

The funding for each of the three elements is distributed amongst the four ‘main subject panels’ 7 in proportion to the volume of research in each main panel which was 3* or above, weighted to reflect an assumed relative cost of research in different disciplines.

Within each main panel, mainstream QR funding is distributed to each UOA according to the volume of research at 3* or above and the cost weights (which reflect the relative cost of undertaking research in different disciplines), and with an additional multiplier of 4 being given to research rated as world-leading, i.e., 4* research, compared to internationally excellent, or 3*, research.

The mainstream QR funding for each element in each UOA is then distributed to individual HEIs according to the volume of research at 3* or above produced by that HEI, with the cost and quality weights taken into account.

Therefore, a university’s total QR mainstream funding comprises an amount for each element of outputs, impact and environment, for each UOA in which it made a submission.

Since the allocation of the mainstream QR funding in each pot (environment, impact and output) is closely related to the performance of the UOAs in each respective research element, we also found positive and significant correlation coefficients between mainstream QR funding distributed to the UOAs in the environment, impact and output pots at the 1% level (see Table 3 ). Similarly, when we carried out PCA analysis, we found that the first principal component accounts for approximately 97% of the variation in the components, and the first principal component results in roughly similar eigenvectors (see Table 4 ), suggesting that equal funding could be distributed in the environment, impact and output pots.

Correlation matrix between different funding pots

Results of PCA of the three elements using funds distributed in each pot

3.3 Alternative ways of allocating QR funding and obtaining overall REF scores

Based on the arguments in the redundancy literature, we examine the effects of excluding one element of the evaluation while distributing QR funding and calculating overall REF scores. Initially, as described in Section 3.2, the mainstream QR funding is distributed across three pots (i.e., output, environment and impact) where 65%, 20% and 15% of the mainstream QR funding is distributed based on the performances of the submissions in output, impact and environment elements in REF 2014, respectively (i.e., step 1 of the funding formula). Similarly, the overall REF scores of units and HEIs were obtained by a weighted average of the three elements where the output, impact and environment performances were weighted 65%, 20% and 15%, respectively. If one of the elements (i.e., environment, impact and output) is excluded, the weight given to it should be allocated amongst the other two elements to redistribute the QR funding and to obtain the overall REF scores, so that the weights sum to 100%. In the first scenario, we exclude the environment element and reallocate the weight of environment to output and impact in proportion to their initial weights: 65:20, which becomes 76.5% and 23.5%. 8 For the second scenario, we exclude the impact element and reallocate the weight of impact to the environment and output in proportion to their initial weights: 15:65, which results in 18.75% and 81.25%. Finally, if we exclude the output element, then the environment and impact elements are allocated 43% and 57% weights based on their initial weight ratio of 15:20. Finally, as a fourth scenario, we rely on the results obtained with the PCA and that each element is kept in the calculation of the overall GPA and distribution of QR funding, but instead, each element is given equal weights (i.e., 33.33%).

Based on the funding formula of the mainstream QR funding allocation (see Research England 2019a , 16–9 for details on how the mainstream QR funding is allocated or Section 3.2 of this article for the steps), we follow the same steps to redistribute the mainstream QR funding across different panels, UOAs and HEIs based on the alternative scenarios. To obtain the overall REF scores of HEIs, the overall GPA of each unit is obtained by weighting the GPA of output, impact and environment elements with 65%, 20% and 15%, respectively. With the alternative scenarios, we will obtain the overall GPA of the HEIs by weighting elements with respective scenario weights as discussed above.

4.1 Alternative way of allocating QR funding

In this subsection, we will examine the effect of the mainstream QR funding distribution to different panels, UOAs, and HEIs in England with Scenarios 1–4 compared to the official mainstream QR funding allocation. To provide an overall picture of the amount of mainstream QR funding distributed in 2019–20 funding period, Table 5 provides the amount of mainstream QR funding distributed in each of the three pots with the official REF 2014 results, and mainstream QR funding distributed with the alternative scenarios proposed in this article. During the 2019–20 funding period, a total of £1,060 million (i.e., just over a billion pounds) was distributed under the mainstream QR funding and roughly £159 million, £212 million and £689 million of mainstream QR funding are distributed in the environment, impact and output pots across the English HEIs, respectively. 9 On the other hand, with Scenarios 1, 2 and 3, no mainstream QR funding is distributed in the environment, impact and output pots, respectively. Whereas, equal amounts of funds are distributed in each pot with Scenario 4. With Scenario 1, £249 million and £811 million of mainstream QR funding are distributed based on the REF 2014 performances in impact and output elements, indicating that an additional £37 million and £122 million are distributed in the impact and output pots compared to the official scenario, respectively. In contrast, with Scenario 2, £199 million and £862 million of mainstream QR funding are distributed in environment and output elements, indicating that additional £39 million and £72 million are distributed in the environment and output pots compared to the official scenario, respectively. In Scenario 3, £456 million and £605 million are distributed in environment and impact pots, respectively, suggesting that additional £297 million and £392 million were distributed in respective pots compared to the official scenario. Finally, with Scenario 4, an equal amount of funds (i.e., £353.5 million) are distributed in each pot where more funding is allocated in environment and impact pots and less funding is distributed in output pot.

Distribution of mainstream QR funding across different pots based on the REF2014 results and alternative scenarios

Table 6 provides the allocation of the mainstream QR funding to four main panels (i.e., Panel A: Medicine, Health and Life Sciences; Panel B: Physical Sciences, Engineering and Mathematics; Panel C: Social Sciences; Panel D: Arts and Humanities) with the REF 2014 results, and with alternative scenarios. This table also provides the change in the mainstream QR funding received by four main panels from the official allocation to alternative scenarios where a positive (negative) change indicates that the panel would have received more (less) funding with the alternative scenario compared to the official allocation. The results suggest that the panel B would have been allocated more funds, and panels A, C and D would have been allocated less QR funding with the alternative Scenarios 1 and 2 compared to the official allocation, suggesting that exclusion of environment and impact elements would have benefitted panel B. On the other hand, panel B (panels A, C and D) would have generated less (more) QR funding with the third and fourth scenarios (i.e., when the output element is excluded, and equal amount of funds distributed in each pot, respectively) compared to the official scenario. Overall, with the reallocation of QR funding with alternative Scenarios 1, 2, 3 and 4, only 0.34%, 0.64%, 2.29% and 1.08% of the total mainstream QR funding (i.e., £3.6 million, £6.8 million, £24.3 million and £11.5 million) would have been reallocated across the four main panels with the alternative allocation scenarios compared to the official one.

Allocation of the mainstream QR funding to four main panels with the alternative scenarios

Note: Panels A (Medicine, Health and Life Sciences), B (Physical Sciences, Engineering and Mathematics), C (Social Sciences) and D (Arts and Humanities) consist of the UoAs between 1 and 6, 7 and 15, 16 and 26, and 27 and 36, respectively.

Table 7 reports the official QR funding allocation and the QR funding allocation changes between alternative scenarios and official scenario in different UOAs where a positive (negative) figure suggests that the UOA received relatively more (less) QR funding with the alternative scenario compared to the official case. We find, for example, that the Computer Science and Informatics, and the Public Health, Health Services and Primary Care units would have received £2.0 million more and £1.2 million less QR funding when the environment element is excluded (Scenario 1) compared to the official scenario, respectively. On the other hand, when the impact element is excluded (Scenario 2), the Biological Sciences and Clinical Medicine units would have generated £3.0 million more and £4.3 million less than the official scenario, respectively. When the output element is excluded from the evaluation (Scenario 3), we find that the Clinical Medicine and Biological Sciences units would have generated £11.7 million more and £7.2 million less compared to the official scenario, respectively. Finally, if all three elements are weighted equally (Scenario 4), Clinical Medicine and Computer Science and Informatics units would have generated £5.1 million more and £3.5 million less than the official scenario, respectively. This evaluation clearly shows in which elements specific subjects perform better (worse) than other subject areas. Even though we observe changes in funds generated by each unit with alternative scenarios, there is a limited funding shift across units. Overall, the total amounts reallocated across different UOAs are £5.9 million, £11.5 million, £36.9 million and £17.2 million with Scenarios 1, 2, 3 and 4, which correspond to 0.55%, 1.08%, 3.48% and 1.62% of the total mainstream QR funding, respectively.

Allocation of mainstream QR funding across different UoAs and changes in funding allocation with alternative scenarios compared to benchmark

Note: A positive (negative) figure in changes columns suggests that the UOA received relatively more (less) QR funding with the respective alternative scenario compared to the official case.

Finally, we examine the effect of alternative QR funding allocations on the funding received by HEIs. Table 8 shows the five HEIs that would have generated the biggest increase (decrease) in mainstream QR funding with the alternative scenarios compared to the official allocation. The data show that the University of Leicester, University of Plymouth, University of East Anglia, University of Birmingham and the University of Surrey would have generated £745k, £552k, £550k, £522k and £464k more QR funding with the first scenario compared to the official scenario, whereas University College London, University of Cambridge, University of Oxford, University of Manchester and the University of Nottingham would have generated £3.4 million, £2.1 million, £2million, £1.5 million and £1.4 million less, respectively. On the other hand, the University of Cambridge would have generated £1.9 million more if the impact element is excluded (Scenario 2), and University College London would have generated £9.8 million and £5.6 million more if the output element is excluded (Scenario 3) and each element is weighted equally (Scenario 4), respectively. In comparison, the University of Leeds, University of Birmingham and University of Leicester would have generated £1 million, £2.4 million and £1.3 million less with Scenarios 2, 3 and 4, respectively. Overall, the total amounts reallocated across different HEIs are £15.5 million, £11.1 million, £46.7 million and £25.6 million with Scenarios 1, 2, 3 and 4, which correspond to just 1.46%, 1.05%, 4.41% and 2.42% of the total mainstream QR funding, respectively. Furthermore, only a handful of universities would have experienced a significant change in their funding allocation with alternative scenarios where 6, 3, 25 and 10 HEIs experienced a difference in their QR funding allocation of more than £1 million with Scenarios 1, 2, 3 and 4 compared to the official one, respectively (see Appendix Table A.1 for the allocation of the mainstream QR funding to the HEIs with the official case and also the difference in the allocation of QR funding between alternative scenarios and official one).

Five HEIs that would generate more (less) with the alternative scenarios compared to the official scenario

4.2 Ranking of HEIs

Since the REF exercise is used in the rankings of HEIs, in this subsection, we will evaluate the effect of different scenarios on the overall GPA and rankings of HEIs. Table 9 offers the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients between GPA scores obtained with the official scenario and the GPA scores obtained with the alternative scenarios. We find that the GPA scores obtained with the alternative scenarios are highly and positively correlated with the official GPA scores at the 1% level. Even though the correlation coefficients between GPA scores of HEIs with the alternative scenarios and official one are highly and positively correlated, some HEIs would have been ranked in relatively higher (lower) positions with the alternative scenarios compared to the official scenario. Amongst 111 HEIs, just 9, 5, 22 and 5 HEIs experienced more than 10 position changes in their ranking with the Scenarios 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively, compared to the official rankings. For instance, Guildhall School of Music & Drama would have experienced a major improvement in their ranking with the third scenario as it would have been ranked in the 53rd position when output element is excluded (i.e., Scenario 1) compared to the 89th position with the official scenario. On the other hand, London Business School would have been ranked in the 32nd position with the third scenario, but ranked 7th with the official scenario (see Appendix Table A.2 for the GPA scores and respective rankings of HEIs with the official case and Scenarios 1, 2, 3 and 4). However, with very few exceptions, it can be seen that the difference between the rankings in the alternative scenarios compared with the official rankings is relatively small.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients between official and alternative scenario GPAs

Note: Asterisk (*) represents significance level at the 1% level.

Given concerns over possible bias in the assessment of the three elements of the REF and the cost of preparing the REF return ( Farla and Simmonds 2015 ), we evaluated the implications of the exclusion of different elements from the REF. Since three components of the REF are positively and highly correlated, each of the elements of the REF could be considered redundant and therefore, this article examined the QR funding allocation implications to different panels, UOAs and HEIs when an element (environment, impact and output) of the REF was disregarded from the allocation of the QR funding and the effect on the obtaining the overall REF GPAs. Furthermore, we also use the PCA method to get weights that explain most of the variation in the funding distributed amongst three elements, which suggested that using equal weights to distribute funds explains most of the variation in funding distribution in three pots.

We found that the exclusion of one element from the REF or using equal weights would have benefited (disadvantaged) some HEIs, but at most £46.7 million (out of over £1 billion) would have been reallocated between HEIs when the output element is excluded from the evaluation. Furthermore, when different elements are excluded from the rankings and the weight of the excluded element redistributed between the other two (in proportion to their original weightings) to produce new rankings, these rankings are highly and significantly correlated with the official rankings, suggesting that alternative ways of obtaining composite scores lead to rankings similar to the official one. Overall, the main argument of this article is that given the high cost of preparing REF returns, the potential bias in assessing each component, and the relatively small effect on QR income distribution and universities’ relative rankings of removing some elements of the REF assessment, removal of some elements from the assessment process may be considered for future assessment exercises.

This article does not quantify the bias involved in the evaluation of each element of the REF exercise, and therefore, we do not provide any suggestion about which element should be removed from the REF. Instead, our findings demonstrate that excluding a component from the REF evaluation does not result in significant rank reversals in overall outcomes and reallocation of funds across units and HEIs.

In addition, the assessment of outputs and impact cases in the REF are both based on the submit-to-be-rated methodology from 1986 by which, in essence, the achievements of individuals, not of the organization, are summed up. Based on the definition of organizational evaluation by BetterEvaluation (2021) , impact and output evaluations of the REF are based on the achievements of individuals, and if the aim is to evaluate the organizations, then evaluation of the impact and output elements, which are in essence individual achievements, could be removed, and their removal from the evaluation will not result in significant effects as found in this article. Therefore, if the REF aims to evaluate the organizational performance, the choice of the components should be further motivated by and rely on the metrics that evaluate the organization rather than the individual achievements.

Furthermore, if future evaluations include new metrics that aim to measure organizational achievement, these metrics should be carefully chosen to provide a new set of information beyond the existing indicators. Therefore, these indicators should not be highly correlated with the already existing indicator set so that new information is captured through their assessment.

There is a significant body of literature on PRFS, and for a review of these systems, the reader is directed to a number of papers and references ( Rebora and Turri 2013 ; Bertocchi et al. 2015 ; De Boer et al. 2015 ; Hicks et al. 2015 ; Dougherty et al. 2016 ; Geuna and Piolatto 2016 ; Sivertsen 2017 ; Zacharewicz et al. 2019 , amongst many others).

Education is a devolved matter in the UK, and university funding and oversight in 2014 was the responsibility of the Higher Education Funding Council (HEFCE) in England, the Scottish Funding Council (SFC) in Scotland, the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales (HEFCW) in Wales and the Department for Employment and Learning (DELNI) in Northern Ireland. The formulae which converted REF performance into QR funding were different in the different administrations, and this article only examines the QR distribution across English HEIs.

An environment that is conducive to producing research of world-leading quality, internally excellent quality, international recognized quality and nationally recognized quality is given 4*, 3*, 2* and 1* scores, respectively. On the other hand, an environment that is not conducive to producing research of at least nationally recognized quality is considered as unclassified.

The cost to UK HEIs of submitting to REF, excluding the impact element was estimated at £157 million ( Farla and Simmonds 2015 , 6). It is further estimated that 12% of time spent at the central level was on the environment template and 17% of time at the UOA level (see Figures 5 and 6 of Farla and Simmonds 2015 , respectively). The estimate of £19–27 million is obtained as 12–17% of the overall £157 million non-impact cost of submission. Furthermore, it was found that the panel members spent on average 533 h on panel duties, which represented an estimated cost to the sector of £23 million (see Farla and Simmonds 2015 , 40, 41).

As stated previously, because the devolved administrations of the UK used different methods to calculate QR income, this article focusses just on English institutions.

The scores for each individual output, environment or impact component are not given on the REF 2014 website, www.ref.ac.uk/2014 . In other words, the ratings of each research output, research environment element and impact case study are not provided. However, the REF results instead provide the percentage of the overall research elements (i.e., research output, environment and impact) that were rated as 4*, 3*, 2* and 1* and unclassified. Therefore, the weighted average of the research elements (i.e., output, environment and impact) are obtained as follows. If the 35%, 30%, 20% and 15% of the research element of a given submission were rated as 4*, 3*, 2* and 1*, respectively, then the weighted average score of this element would be (35 * 4+30 * 3+20 * 2+15 * 1)/100=2.85.

The four main panels are groupings of individual UOAs which broadly speaking encompass medical, and health and biological sciences (Panel A), physical sciences and engineering (Panel B), social sciences (Panel C) and humanities and arts (Panel D).

These percentage weights are obtained by (0.65/0.85)×100 and (0.2/0.85)×100, respectively.

Note that HEIs within inner and outer London area receive 12% and 8% (respectively) additional QR funding on top of their allocated mainstream QR funding but to examine the effect of the exclusion of alternative scenarios on the allocation of the mainstream QR funding, we do not consider the additional funding allocation that is based on the location of HEI.

We would like to thank the editor and three anonymous referees for very constructive and insightful reviews of earlier drafts of this article.

Conflict of interest statement . None declared.

Bertocchi G. , Gambardella A. , Jappelli T. , Nappi C. A. , Peracchi F. ( 2015 ) ‘ Bibliometric Evaluation vs. Informed Peer Review: Evidence from Italy ’, Research Policy , 44 : 451 – 66 .

Google Scholar

Bérenger V. , Verdier-Chouchane A. ( 2007 ) ‘ Multidimensional Measures of Well-Being: Standard of Living and Quality of Life across Countries ’, World Development , 35 : 1259 – 76 .

BetterEvaluation ( 2021 ) Evaluating the Performance of an Organisation < https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/theme/organisational_performance > accessed 15 October 2021.

Cahill M. B. ( 2005 ) ‘ Is the Human Development Index Redundant? ’, Eastern Economic Journal , 31 : 1 – 6 .

De Boer H. , Jongbloed B. , Benneworth P. , Cremonini L. , Kolster R. , Kottmann A. , Lemmens-Krug K. , Vossensteyn H. ( 2015 ) ‘Performance-based funding and performance agreements in fourteen higher education systems’, report for the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, The Hague: Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.

Dougherty K. J. , Jones S. M. , Lahr H. , Natow R. S. , Pheatt L. , Reddy V. ( 2016 ) Performance Funding for Higher Education , Baltimore, MD : Johns Hopkins University Press .

Google Preview

Farla K. , Simmonds P. ( 2015 ) ‘REF accountability review: Costs, benefits and burden’, report by Technopolis to the four UK higher education funding bodies. Technopolis Group < http://www.technopolis-group.com/report/ref-accountability-review-costs-benefits-and-burden/ > accessed 14 March 2021.

Geuna A. , Piolatto M. ( 2016 ) ‘ Research Assessment in the UK and Italy: Costly and Difficult, but Probably Worth It (at least for a while) ’, Research Policy , 45 : 260 – 71 .

Gilroy P. , McNamara O. ( 2009 ) ‘ A Critical History of Research Assessment in the United Kingdom and Its Post‐1992 Impact on Education ’, Journal of Education for Teaching , 35 : 321 – 35 .

Hicks D. ( 2012 ) ‘ Performance-Based University Research Funding Systems ’, Research Policy , 41 : 251 – 61 .

Hicks D. , Wouters P. , Waltman L. , de Rijcke S. , Rafols I. ( 2015 ) ‘ Bibliometrics: The Leiden Manifesto for Research Metrics ’, Nature , 520 : 429 – 31 .

Hinze S. , Butler L. , Donner P. , McAllister I. ( 2019 ) ‘Different Processes, Similar Results? A Comparison of Performance Assessment in Three Countries’, in Glänzel W. , Moed H. F. , Schmoch U. , Thelwall M. (eds) Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators , pp 465-484. Cham : Springer .

Jonkers K. , Zacharewicz T. ( 2016 ) ‘Research performance based funding systems: A comparative assessment’, JRC Science for Policy Report, European Commission: Joint Research Centre < https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC101043/kj1a27837enn.pdf > accessed 15 May 2021.

Kelly A. ( 2016 ) ‘Funding in English Universities and its Relationship to the Research Excellence Framework’, British Education Research Journal , 42 : 665 – 81 .

Khatun T. ( 2009 ) ‘ Measuring Environmental Degradation by Using Principal Component Analysis ’, Environment, Development and Sustainability , 11 : 439 – 57 .

McGillivray M. ( 1991 ) ‘ The Human Development Index: Yet Another Redundant Composite Development Indicator ’, World Development , 19 : 1461 – 8 .

McGillivray M. ( 2005 ) ‘ Measuring Non-Economic Wellbeing Achievement ’, Review of Income and Wealth , 51 : 337 – 64 .

McGillivray M. , White H. ( 1993 ) ‘ Measuring Development? The UNDP’s Human Development Index ’, Journal of International Development , 5 : 183 – 92 .

Manville C. , Guthrie, S. , Henham M. L. , Garrod B. , Sousa S. , Kirtley A., Castle-Clarke, S., Ling, T et al. ( 2015 ) ‘Assessing impact submissions for REF 2014: An evaluation’ < www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1000/RR1032/RAND_RR1032.pdf> accessed 7 April 2021.

Marques M. , Powell J. J. W. , Zapp M. , Biesta G. ( 2017 ) ‘ How Does Research Evaluation Impact Educational Research? Exploring Intended and Unintended Consequences of Research Assessment in the United Kingdom, 1986–2014 ’, European Educational Research Journal , 16 : 820 – 42 .

Nardo M. , Saisana M. , Saltelli A. , Tarantola S. ( 2008 ). Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide , Paris : OECD Publishing < https://www.oecd.org/sdd/42495745.pdf > accessed 15 October 2021.

Nguefack‐Tsague G. , Klasen S. , Zucchini W. ( 2011 ) ‘ On Weighting the Components of the Human Development Index: A Statistical Justification ’, Journal of Human Development and Capabilities , 12 : 183 – 202 .

Penfield T. , Baker M. , Scoble R. , Wykes M. ( 2014 ) ‘ Assessment, Evaluations, and Definitions of Research Impact: A Review ’, Research Evaluation , 23 : 21 – 32 .

Pidd M. , Broadbent J. ( 2015 ) ‘ Business and Management Studies in the 2014 Research Excellence Framework ’, British Journal of Management , 26 : 569 – 81 .

Pinar M. ( 2020 ) ‘ It is Not All about Performance: Importance of the Funding Formula in the Allocation of Performance-Based Research Funding in England ’, Research Evaluation , 29 : 100 – 19 .

Pinar M. , Milla J. , Stengos T. ( 2019 ) ‘ Sensitivity of University Rankings: Implications of Stochastic Dominance Efficiency Analysis ’, Education Economics , 27 : 75 – 92 .

Pinar M. , Unlu E. ( 2020a ) ‘ Evaluating the Potential Effect of the Increased Importance of the Impact Component in the Research Excellence Framework of the UK ’, British Educational Research Journal , 46 : 140 – 60 .

Pinar M. , Unlu E. ( 2020b ) ‘ Determinants of Quality of Research Environment: An Assessment of the Environment Submissions in the UK’s Research Excellence Framework in 2014 ’, Research Evaluation , 29 : 231 – 44 .

Rebora G. , Turri M. ( 2013 ) ‘ The UK and Italian Research Assessment Exercises Face to Face ’, Research Policy , 42 : 1657 – 66 .

REF ( 2011 ) Assessment Framework and Guidance on Submissions < https://www.ref.ac.uk/2014/media/ref/content/pub/assessmentframeworkandguidanceonsubmissions/GOS%20including%20addendum.pdf > accessed 7 April 2021.

REF ( 2012 ) Panel Criteria and Working Methods < https://www.ref.ac.uk/2014/media/ref/content/pub/panelcriteriaandworkingmethods/01_12_1.pdf > accessed 21 May 2021.

REF ( 2014 ) Results and Submissions < https://results.ref.ac.uk/(S(ag0fd0kpw5wgdcjk2rh1cwxr ))/> accessed 05 May 2021.

Research England ( 2019a ) Research England: How We Fund Higher Education Institutions < https://re.ukri.org/documents/2019/research-england-how-we-fund-higher-education-institutions-pdf/ > accessed 3 July 2020.

Research England ( 2019b ) Annual Funding Allocations 2019–20 < https://re.ukri.org/finance/annual-funding-allocations/annual-funding-allocations-2019-20/ > accessed 5 July 2020.

Robinson-Garcia N. , Torres-Salinas D. , Herrera-Viedma E. , Docampo D. ( 2019 ) ‘ Mining University Rankings: Publication Output and Citation Impact as Their Basis ’, Research Evaluation , 28 : 232 – 40 .

Saisana M. , d’Hombres B. , Saltelli A. ( 2011 ) ‘ Rickety Numbers: Volatility of University Rankings and Policy Implications ’, Research Policy , 40 : 165 – 77 .

Shattock M. ( 2012 ) Making Policy in British Higher Education 1945–2011 , Berkshire : McGraw-Hill .

Sivertsen G. ( 2017 ) ‘ Unique, but Still Best Practice? The Research Excellence Framework (REF) from an International Perspective ’, Palgrave Communications , 3 : 1 – 6 .

Smith S. , Ward V. , House A. ( 2011 ) ‘“ Impact” in the Proposals for the UK’s Research Excellence Framework: Shifting the Boundaries of Academic Autonomy ’, Research Policy , 40 : 1369 – 79 .

Taylor J. ( 2011 ) ‘ The Assessment of Research Quality in UK Universities: Peer Review or Metrics? ’, British Journal of Management , 22 : 202 – 17 .

Thorpe A. , Craig R. , Hadikin G. , Batistic S. ( 2018a ) ‘ Semantic Tone of Research “Environment” Submissions in the UK’s Research Evaluation Framework 2014 ’, Research Evaluation , 27 : 53 – 62 .

Thorpe A. , Craig R. , Tourish D. , Hadikin G. , Batistic S. ( 2018b ) ‘ Environment’ Submissions in the UK’s Research Excellence Framework 2014 ’, British Journal of Management , 29 : 571 – 87 .

Tijssen R. J. W. , Yegros-Yegros A. , Winnink J. J. ( 2016 ) ‘ University–Industry R&D Linkage Metrics: Validity and Applicability in World University Rankings ’, Scientometrics , 109 : 677 – 96 .

Watermeyer R. ( 2016 ) ‘ Impact in the REF: Issues and Obstacles ’, Studies in Higher Education , 41 : 199 – 214 .

Wilsdon J., Allen, L., Belfiore, E., Campbell, P., Curry, S., Hill, S., Jones, R., Kain, R., Kerridge, S., Thelwall, M., Tinkler, J., Viney, I., Wouters, P., Hill, J., Johnson, B. ( 2015 ) ‘The metric tide: Report of the independent review of the role of metrics in research assessment and management’. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.4929.1363.

Zacharewicz T. , Lepori B. , Reale E. , Jonkers K. ( 2019 ) ‘ Performance-Based Research Funding in EU Member States—A Comparative Assessment ’, Science and Public Policy , 46 : 105 – 15 .

Allocation of mainstream QR funding allocation to HEIs with the official and alternative scenarios

Notes: Official column presents the allocation of mainstream QR funding across HEIs with the official funding allocation.

Scenario 1—Official: This column provides the differences in the mainstream QR funding allocated to the HEIs between Scenario 1 and official case.

Scenario 2—Official: This column provides the differences in the mainstream QR funding allocated to the HEIs between Scenario 2 and official case.

Scenario 3—Official: This column provides the differences in the mainstream QR funding allocated to the HEIs between Scenario 3 and official case.

Scenario 4—Official: This column provides the differences in the mainstream QR funding allocated to the HEIs between Scenario 4 and official case.

A positive (negative) figure in changes columns suggests that the HEI received relatively more (less) QR funding with the respective alternative scenario compared to the official case.

GPA scores and respective rankings of HEIs with the official case and Scenarios 1, 2, 3 and 4

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1471-5449

- Print ISSN 0958-2029

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Contact sales

Start free trial

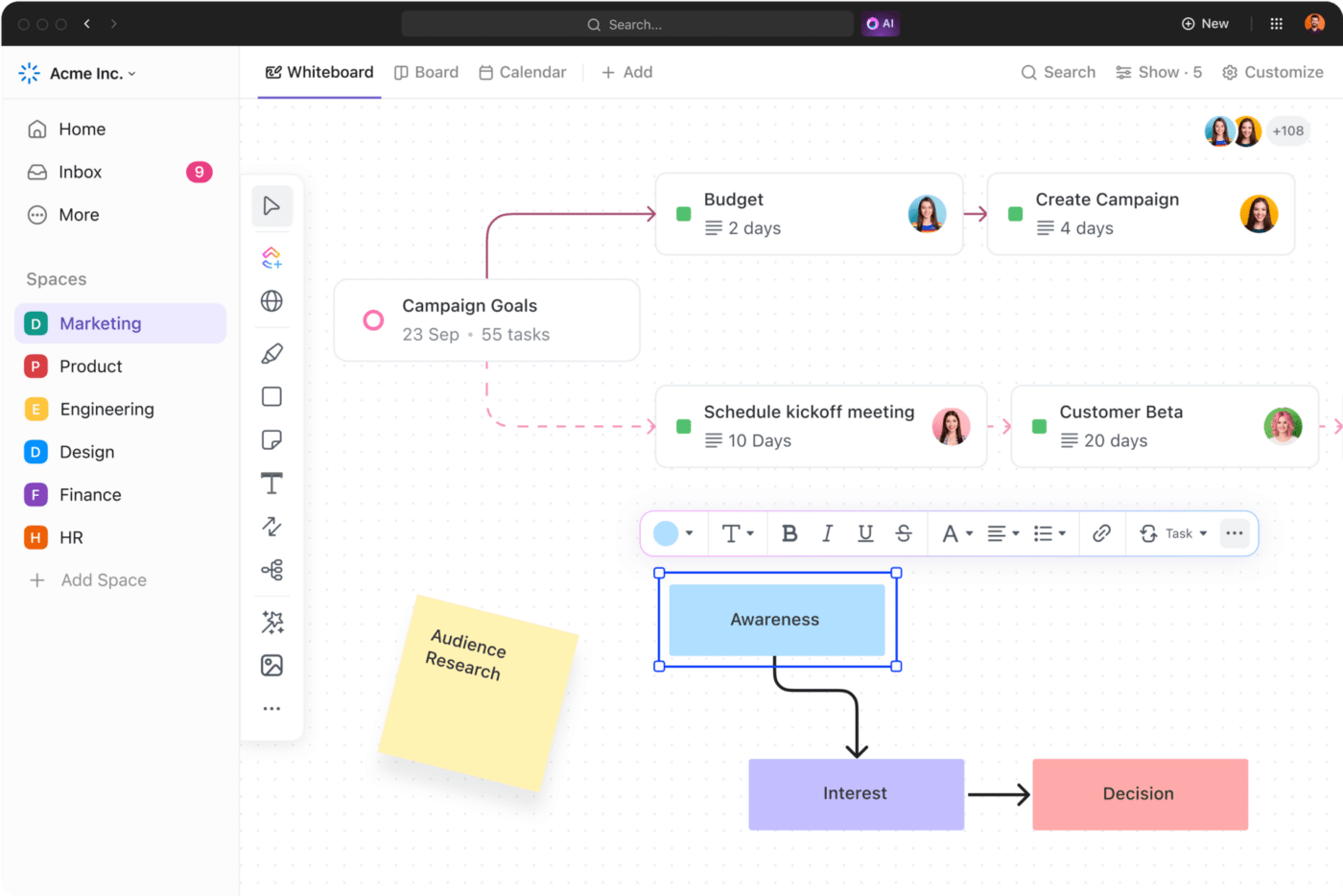

Project Evaluation Process: Definition, Methods & Steps

Managing a project with copious moving parts can be challenging to say the least, but project evaluation is designed to make the process that much easier. Every project starts with careful planning —t his sets the stage for the execution phase of the project while estimations, plans and schedules guide the project team as they complete tasks and deliverables.

But even with the project evaluation process in place, managing a project successfully is not as simple as it sounds. Project managers need to keep track of costs , tasks and time during the entire project life cycle to make sure everything goes as planned. To do so, they utilize the project evaluation process and make use of project management software to help manage their team’s work in addition to planning and evaluating project performance.

What Is Project Evaluation?

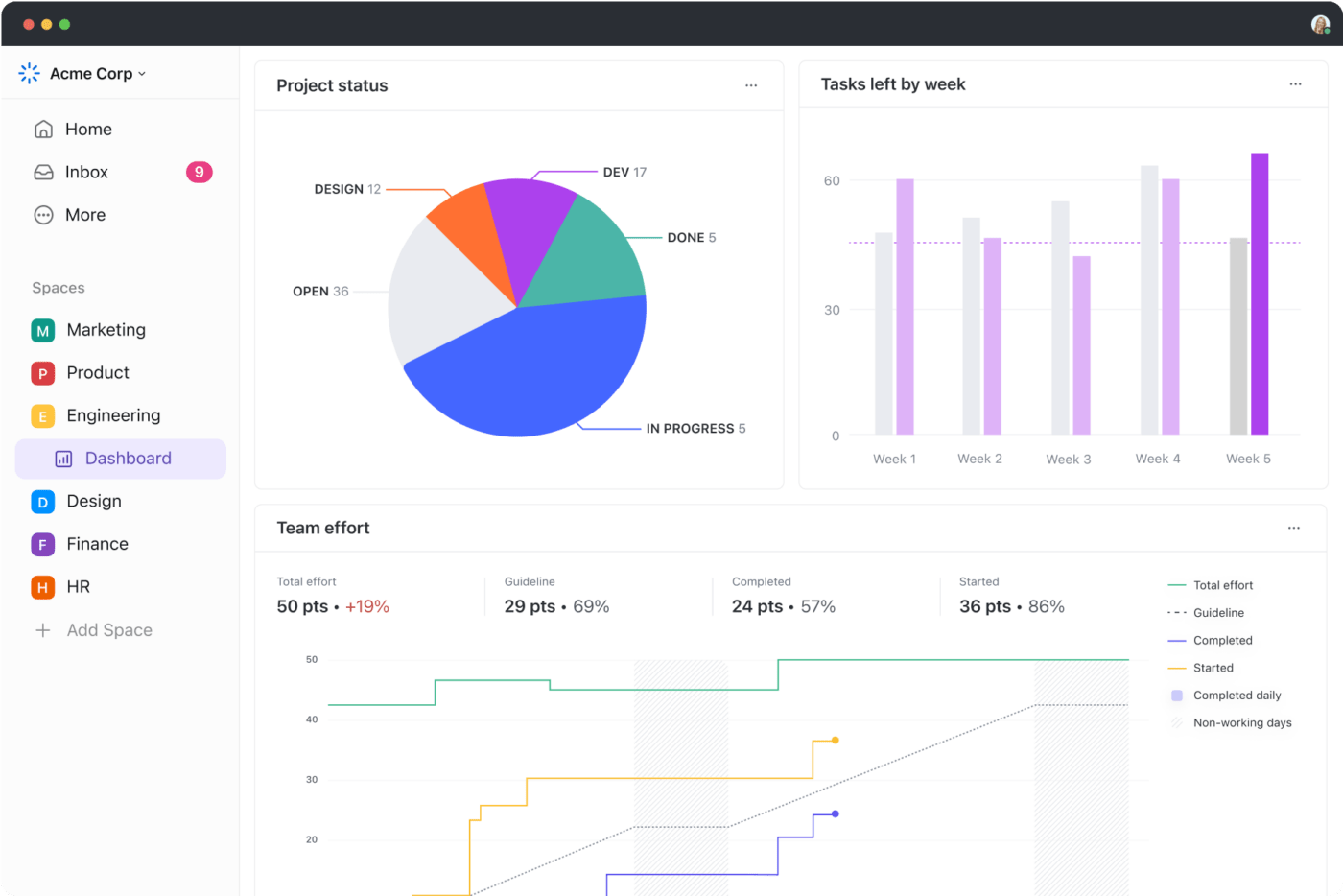

Project evaluation is the process of measuring the success of a project, program or portfolio . This is done by gathering data about the project and using an evaluation method that allows evaluators to find performance improvement opportunities. Project evaluation is also critical to keep stakeholders updated on the project status and any changes that might be required to the budget or schedule.

Every aspect of the project such as costs, scope, risks or return on investment (ROI) is measured to determine if it’s proceeding as planned. If there are road bumps, this data can inform how projects can improve. Basically, you’re asking the project a series of questions designed to discover what is working, what can be improved and whether the project is useful. Tools such as project dashboards and trackers help in the evaluation process by making key data readily available.

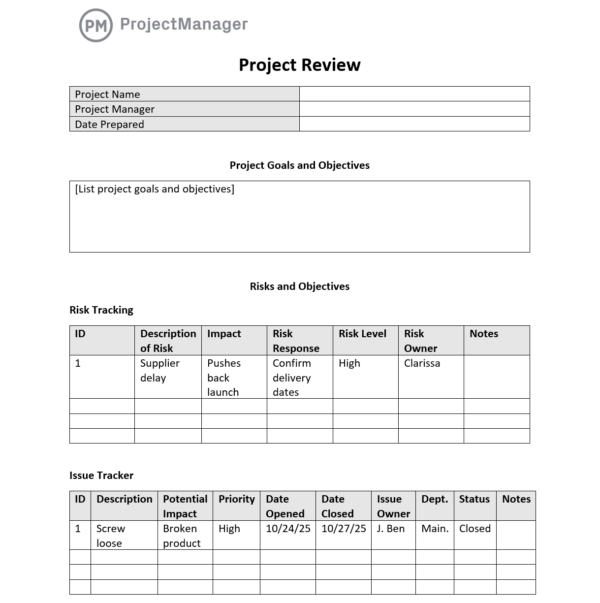

Get your free

Project Review Template

Use this free Project Review Template for Word to manage your projects better.

The project evaluation process has been around as long as projects themselves. But when it comes to the science of project management , project evaluation can be broken down into three main types or methods: pre-project evaluation, ongoing evaluation and post-project evaluation. Let’s look at the project evaluation process, what it entails and how you can improve your technique.

Project Evaluation Criteria

The specific details of the project evaluation criteria vary from one project or one organization to another. In general terms, a project evaluation process goes over the project constraints including time, cost, scope, resources, risk and quality. In addition, organizations may add their own business goals, strategic objectives and other project metrics .

Project Evaluation Methods

There are three points in a project where evaluation is most needed. While you can evaluate your project at any time, these are points where you should have the process officially scheduled.

1. Pre-Project Evaluation

In a sense, you’re pre-evaluating your project when you write your project charter to pitch to the stakeholders. You cannot effectively plan, staff and control a new project if you’ve first not evaluated it. Pre-project evaluation is the only sure way you can determine the effectiveness of the project before executing it.

2. Ongoing Project Evaluation

To make sure your project is proceeding as planned and hitting all of the scheduling and budget milestones you’ve set, it’s crucial that you constantly monitor and report on your work in real-time. Only by using project metrics can you measure the success of your project and whether or not you’re meeting the project’s goals and objectives. It’s strongly recommended that you use project management dashboards and tracking tools for ongoing evaluation.

Related: Free Project Dashboard Template for Excel

3. Post-Project Evaluation

Think of this as a postmortem. Post-project evaluation is when you go through the project’s paperwork, interview the project team and principles and analyze all relevant data so you can understand what worked and what went wrong. Only by developing this clear picture can you resolve issues in upcoming projects.

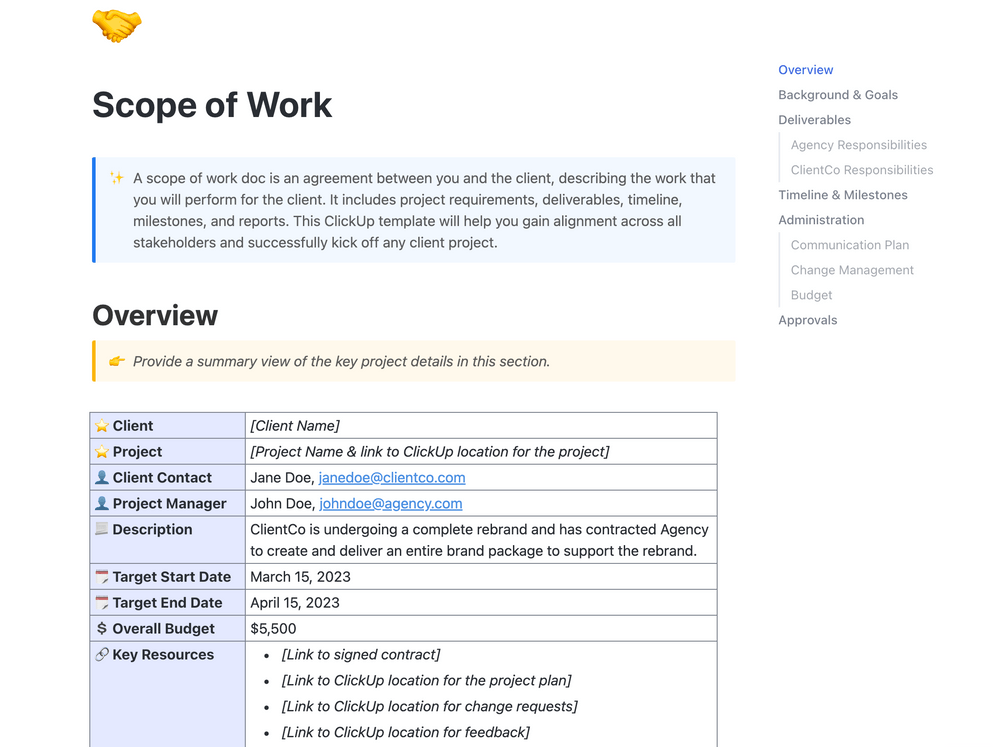

Free Project Review Template for Word

The project review template for Word is the perfect way to evaluate your project, whether it’s an ongoing project evaluation or post-project. It takes a holistic approach to project evaluation and covers such areas as goals, risks, staffing, resources and more. Download yours today.

Project Evaluation Steps

Regardless of when you choose to run a project evaluation, the process always has four phases: planning, implementation, completion and dissemination of reports.

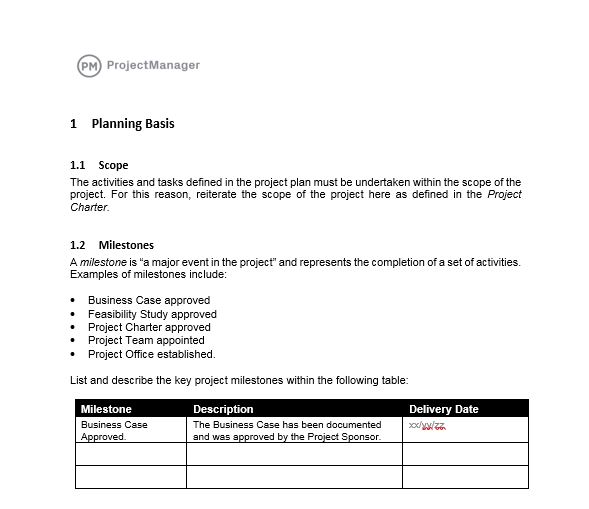

1. Planning

The ultimate goal of this step is to create a project evaluation plan, a document that explains all details of your organization’s project evaluation process. When planning for a project evaluation, it’s important to identify the stakeholders and what their short-and-long-term goals are. You must make sure that your goals and objectives for the project are clear, and it’s critical to have settled on criteria that will tell you whether these goals and objects are being met.

So, you’ll want to write a series of questions to pose to the stakeholders. These queries should include subjects such as the project framework, best practices and metrics that determine success.

By including the stakeholders in your project evaluation plan, you’ll receive direction during the course of the project while simultaneously developing a relationship with the stakeholders. They will get progress reports from you throughout the project life cycle , and by building this initial relationship, you’ll likely earn their belief that you can manage the project to their satisfaction.

2. Implementation

While the project is running, you must monitor all aspects to make sure you’re meeting the schedule and budget. One of the things you should monitor during the project is the percentage completed. This is something you should do when creating status reports and meeting with your team. To make sure you’re on track, hold the team accountable for delivering timely tasks and maintain baseline dates to know when tasks are due.

Don’t forget to keep an eye on quality. It doesn’t matter if you deliver the project within the allotted time frame if the product is poor. Maintain quality reviews, and don’t delegate that responsibility. Instead, take it on yourself.

Maintaining a close relationship with the project budget is just as important as tracking the schedule and quality. Keep an eye on costs. They will fluctuate throughout the project, so don’t panic. However, be transparent if you notice a need growing for more funds. Let your steering committee know as soon as possible, so there are no surprises.

3. Completion

When you’re done with your project, you still have work to do. You’ll want to take the data you gathered in the evaluation and learn from it so you can fix problems that you discovered in the process. Figure out the short- and long-term impacts of what you learned in the evaluation.

4. Reporting and Disseminating

Once the evaluation is complete, you need to record the results. To do so, you’ll create a project evaluation report, a document that provides lessons for the future. Deliver your report to your stakeholders to keep them updated on the project’s progress.

How are you going to disseminate the report? There might be a protocol for this already established in your organization. Perhaps the stakeholders prefer a meeting to get the results face-to-face. Or maybe they prefer PDFs with easy-to-read charts and graphs. Make sure that you know your audience and tailor your report to them.

Benefits of Project Evaluation

Project evaluation is always advisable and it can bring a wide array of benefits to your organization. As noted above, there are many aspects that can be measured through the project evaluation process. It’s up to you and your stakeholders to decide the most critical factors to consider. Here are some of the main benefits of implementing a project evaluation process.

- Better Project Management: Project evaluation helps you easily find areas of improvement when it comes to managing your costs , tasks, resources and time.

- Improves Team performance: Project evaluation allows you to keep track of your team’s performance and increases accountability.

- Better Project Planning: Helps you compare your project baseline against actual project performance for better planning and estimating.

- Helps with Stakeholder Management: Having a good relationship with stakeholders is key to success as a project manager. Creating a project evaluation report is very important to keep them updated.

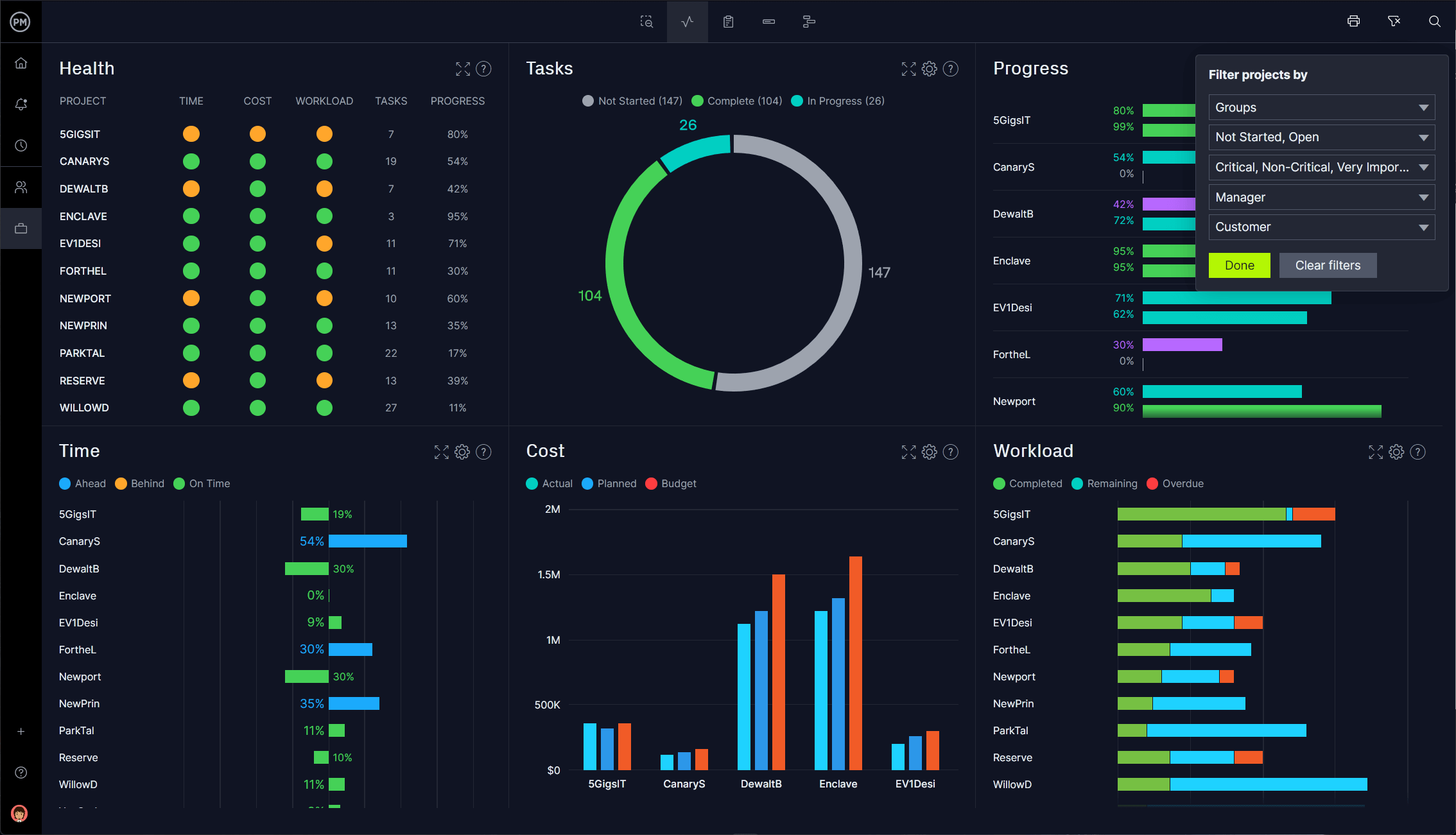

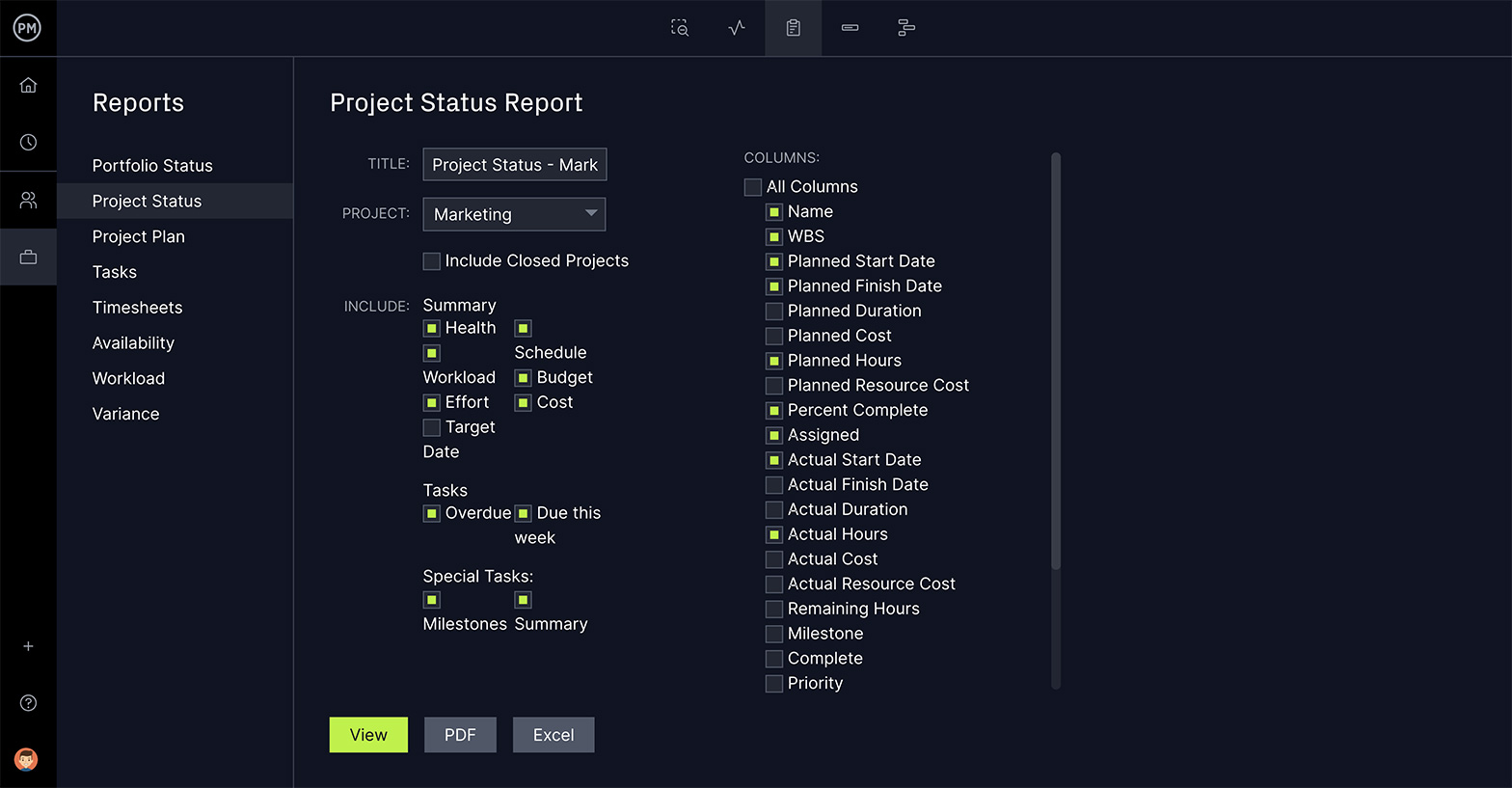

How ProjectManager Improves the Project Evaluation Process

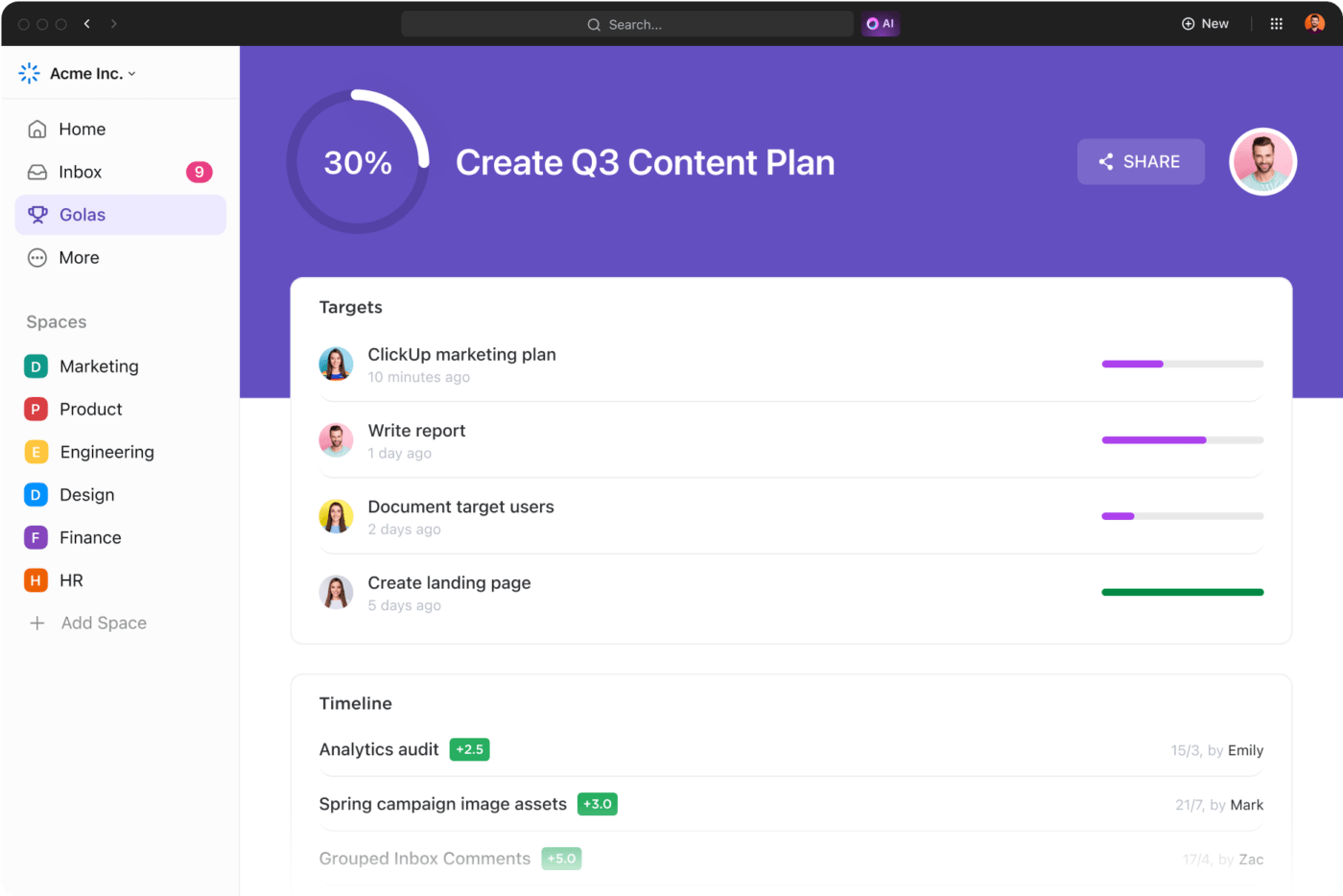

To take your project evaluation to the next level, you’ll want ProjectManager , an online work management tool with live dashboards that deliver real-time data so you can monitor what’s happening now as opposed to what happened yesterday.

With ProjectManager’s real-time dashboard, project evaluation is measured in real-time to keep you updated. The numbers are then displayed in colorful graphs and charts. Filter the data to show the data you want or to drill down to get a deeper picture. These graphs and charts can also be shared with a keystroke. You can track workload and tasks, because your team is updating their status in real-time, wherever they are and at whatever time they complete their work.

Project evaluation with ProjectManager’s real-time dashboard makes it simple to go through the evaluation process during the evolution of the project. It also provides valuable data afterward. The project evaluation process can even be fun, given the right tools. Feel free to use our automated reporting tools to quickly build traditional project reports, allowing you to improve both the accuracy and efficiency of your evaluation process.

ProjectManager is a cloud-based project management software that has a suite of powerful tools for every phase of your project, including live dashboards and reporting tools. Our software collects project data in real-time and is constantly being fed information by your team as they progress through their tasks. See how monitoring, evaluation and reporting can be streamlined by taking a free 30-day trial today!

Deliver your projects on time and under budget

Start planning your projects.

- Project Management Methodologies

- Project Management Metrics

- Project Portfolio Management

- Proof of Concept Templates

- Punch List Templates

- Requirement Gathering Process

- Requirements Traceability Matrix

- Resource Scheduling

- Roles and Responsibilities Template

- Stakeholder Mapping

- Team Charter

- Templates for Managers

- What is Project Baseline

- Work Log Templates

- Workback Schedule

- Workload Management

- Work Breakdown Structures

- Agile Team Structure

- Avoding Scope Creep

- Cross-Functional Flowcharts

- Precision VS Accuracy

- Scrum-Spike

- User Story Guide

- Creating Project Charters

- Guide to Team Communication

- How to Prioritize Tasks

- Mastering RAID Logs

- Overcoming Analysis Paralysis

- Understanding RACI Model

- Eisenhower Matrix Guide

- Guide to Multi Project Management

- Procure-to-Pay Best Practices

- Procurement Management Plan Template to Boost Project Success

- Project Execution and Change Management

- Project Plan and Schedule Templates

- Resource Planning Templates for Smooth Project Execution

- Risk Management and Quality Management Plan Templates

- Risk Management in Software Engineering

- Stage Gate Process

- Stakeholder Management Planning

- Understanding the S-Curve

- Visualizing Your To-Do List

- 30-60-90 Day Plan

- Work Plan Template

- Weekly Planner Template

- Task Analysis Examples

- Cross-Functional Flowcharts for Planning

- Inventory Management Tecniques

- Inventory Templates

- Six Sigma DMAIC Method

- Visual Process Improvement

- Value Stream Mapping

- Creating a Workflow

- Fibonacci Scale Template

- Supply Chain Diagram

- Kaizen Method

- Procurement Process Flow Chart

- UML Activity Diagrams

- Class Diagrams & their Relationships

- Visualize flowcharts for software

- Wire-Frame Benefits

- Applications of UML

- Selecting UML Diagrams

- Create Sequence Diagrams Online

- Activity Diagram Tool

- Archimate Tool

- Class Diagram Tool

- Graphic Organizers

- Social Work Assessment Tools

- Using KWL Charts to Boost Learning

- Editable Timeline Templates

- Guides & Best Practices

- Kinship Diagram Guide

- Graphic Organizers for Teachers & Students

- Visual Documentation Techniques

- Visual Tool for Visual Documentation

- Visualizing a Dichotomous Key

- 5 W's Chart

- Circular Flow Diagram Maker

- Cladogram Maker

- Comic Strip Maker

- Course Design Template

- AI Buyer Persona

- AI Data Visualization

- AI Diagrams

- AI Project Management

- AI SWOT Analysis

- Best AI Templates

- Brainstorming AI

- Pros & Cons of AI

- AI for Business Strategy

- Using AI for Business Plan

- AI for HR Teams

- BPMN Symbols

- BPMN vs UML

- Business Process Analysis

- Business Process Modeling

- Capacity Planning Guide

- Case Management Process

- How to Avoid Bottlenecks in Processes

- Innovation Management Process

- Project vs Process

- Solve Customer Problems

- Startup Templates

- Streamline Purchase Order Process

- What is BPMN

- Approval Process

- Employee Exit Process

- Iterative Process

- Process Documentation

- Process Improvement Ideas

- Risk Assessment Process

- Tiger Teams

- Work Instruction Templates

- Workflow Vs. Process

- Process Mapping

- Business Process Reengineering

- Meddic Sales Process

- SIPOC Diagram

- What is Business Process Management

- Process Mapping Software

- Business Analysis Tool

- Business Capability Map

- Decision Making Tools and Techniques

- Operating Model Canvas

- Mobile App Planning

- Product Development Guide

- Product Roadmap

- Timeline Diagrams

- Visualize User Flow

- Sequence Diagrams

- Flowchart Maker

- Online Class Diagram Tool

- Organizational Chart Maker

- Mind Map Maker

- Retro Software

- Agile Project Charter

- Critical Path Software

- Brainstorming Guide

- Brainstorming Tools

- Visual Tools for Brainstorming

- Brainstorming Content Ideas

- Brainstorming in Business

- Brainstorming Questions

- Brainstorming Rules

- Brainstorming Techniques

- Brainstorming Workshop

- Design Thinking and Brainstorming

- Divergent vs Convergent Thinking

- Group Brainstorming Strategies

- Group Creativity

- How to Make Virtual Brainstorming Fun and Effective

- Ideation Techniques

- Improving Brainstorming

- Marketing Brainstorming

- Rapid Brainstorming

- Reverse Brainstorming Challenges

- Reverse vs. Traditional Brainstorming

- What Comes After Brainstorming

- Flowchart Guide

- Spider Diagram Guide

- 5 Whys Template

- Assumption Grid Template

- Brainstorming Templates

- Brainwriting Template

- Innovation Techniques

- 50 Business Diagrams

- Business Model Canvas

- Change Control Process

- Change Management Process

- NOISE Analysis

- Profit & Loss Templates

- Scenario Planning

- Winning Brand Strategy

- Work Management Systems

- Developing Action Plans

- Guide to setting OKRS

- How to Write a Memo

- Improve Productivity & Efficiency

- Mastering Task Batching

- Monthly Budget Templates

- Top Down Vs. Bottom Up

- Weekly Schedule Templates

- Kaizen Principles

- Opportunity Mapping

- Strategic-Goals

- Strategy Mapping

- T Chart Guide

- Business Continuity Plan

- Developing Your MVP

- Incident Management

- Needs Assessment Process

- Product Development From Ideation to Launch

- Visualizing Competitive Landscape

- Communication Plan

- Graphic Organizer Creator

- Fault Tree Software

- Bowman's Strategy Clock Template

- Decision Matrix Template

- Communities of Practice

- Goal Setting for 2024

- Meeting Templates

- Meetings Participation

- Microsoft Teams Brainstorming

- Retrospective Guide

- Skip Level Meetings

- Visual Documentation Guide

- Weekly Meetings

- Affinity Diagrams

- Business Plan Presentation

- Post-Mortem Meetings

- Team Building Activities

- WBS Templates

- Online Whiteboard Tool

- Communications Plan Template

- Idea Board Online

- Meeting Minutes Template

- Genograms in Social Work Practice

- How to Conduct a Genogram Interview

- How to Make a Genogram

- Genogram Questions

- Genograms in Client Counseling

- Understanding Ecomaps

- Visual Research Data Analysis Methods

- House of Quality Template

- Customer Problem Statement Template

- Competitive Analysis Template

- Creating Operations Manual

- Knowledge Base

- Folder Structure Diagram

- Online Checklist Maker

- Lean Canvas Template

- Instructional Design Examples

- Genogram Maker

- Work From Home Guide

- Strategic Planning

- Employee Engagement Action Plan

- Huddle Board

- One-on-One Meeting Template

- Story Map Graphic Organizers

- Introduction to Your Workspace

- Managing Workspaces and Folders

- Adding Text

- Collaborative Content Management

- Creating and Editing Tables

- Adding Notes

- Introduction to Diagramming

- Using Shapes

- Using Freehand Tool

- Adding Images to the Canvas

- Accessing the Contextual Toolbar

- Using Connectors

- Working with Tables

- Working with Templates

- Working with Frames

- Using Notes

- Access Controls

- Exporting a Workspace

- Real-Time Collaboration

- Notifications

- Meet Creately VIZ

- Unleashing the Power of Collaborative Brainstorming

- Uncovering the potential of Retros for all teams

- Collaborative Apps in Microsoft Teams

- Hiring a Great Fit for Your Team

- Project Management Made Easy

- Cross-Corporate Information Radiators

- Creately 4.0 - Product Walkthrough

- What's New

What is Project Evaluation? The Complete Guide with Templates

Project evaluation is an important part of determining the success or failure of a project. Properly evaluating a project helps you understand what worked well and what could be improved for future projects. This blog post will provide an overview of key components of project evaluation and how to conduct effective evaluations.

What is Project Evaluation?

Project evaluation is a key part of assessing the success, progress and areas for improvement of a project. It involves determining how well a project is meeting its goals and objectives. Evaluation helps determine if a project is worth continuing, needs adjustments, or should be discontinued.

A good evaluation plan is developed at the start of a project. It outlines the criteria that will be used to judge the project’s performance and success. Evaluation criteria can include things like:

- Meeting timelines and budgets - Were milestones and deadlines met? Was the project completed within budget?

- Delivering expected outputs and outcomes - Were the intended products, results and benefits achieved?

- Satisfying stakeholder needs - Were customers, users and other stakeholders satisfied with the project results?

- Achieving quality standards - Were quality metrics and standards defined and met?

- Demonstrating effectiveness - Did the project accomplish its intended purpose?

Project evaluation provides valuable insights that can be applied to the current project and future projects. It helps organizations learn from their projects and continuously improve their processes and outcomes.

Project Evaluation Templates

These templates will help you evaluate your project by providing a clear structure to assess how it was planned, carried out, and what it achieved. Whether you’re managing the project, part of the team, or a stakeholder, these template assist in gathering information systematically for a thorough evaluation.

Project Evaluation Template 1

- Ready to use

- Fully customizable template

- Get Started in seconds

Project Evaluation Template 2

Project Evaluation Methods

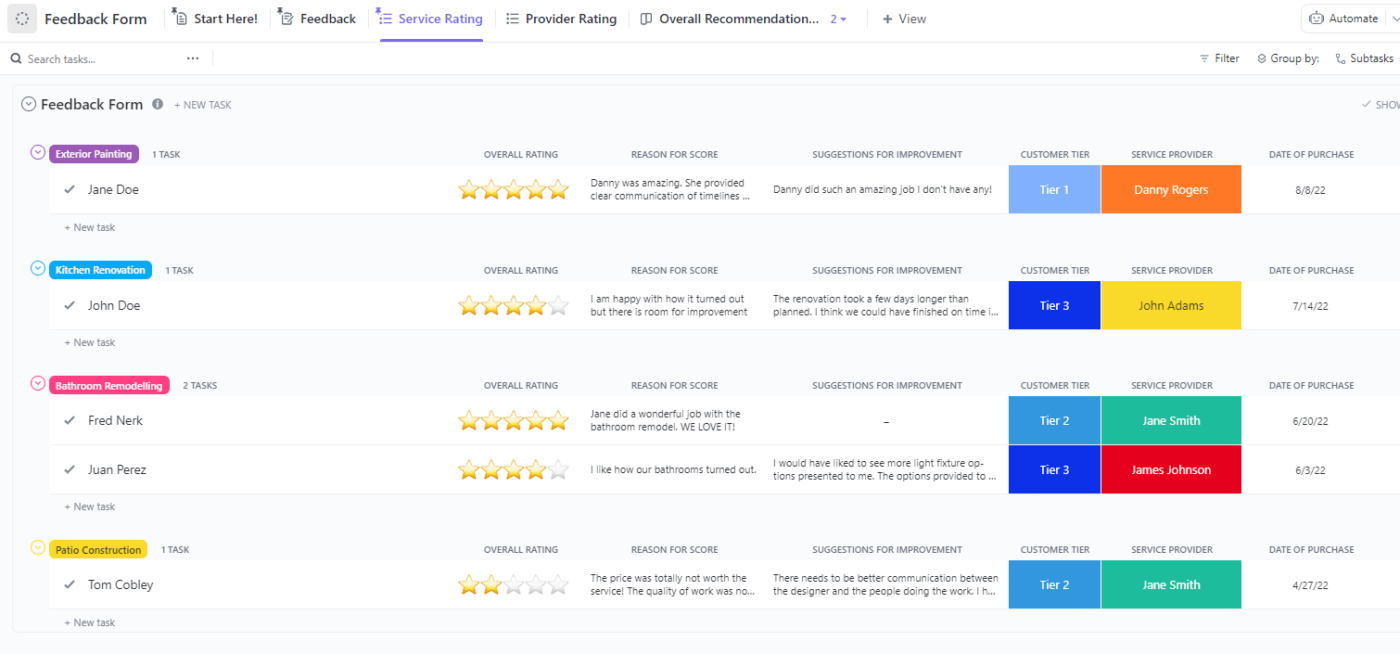

Project evaluation involves using various methods to assess the performance and impact of a project. The choice of methods depends on the nature of the project, its objectives, and the available resources. Here are some common project evaluation methods:

Pre-project evaluation

Pre-project evaluations are done before a project begins. This involves evaluating the project plan, scope, objectives, resources, and budget. This helps determine if the project is feasible and identifies any potential issues or risks upfront. It establishes a baseline for later evaluations.

Ongoing evaluation

Ongoing evaluations happen during the project lifecycle. Regular status reports track progress against the project plan, budget, and deadlines. Any deviations or issues are identified and corrective actions can be taken promptly. This allows projects to stay on track and make adjustments as needed.

Post-project evaluation