How COVID-19 Homeschooling Affected Parents' Mental Health

A study looked at couples' anxiety, depression, substance misuse, and coping..

Posted April 7, 2023 | Reviewed by Devon Frye

- A Parent's Role

- Find a family therapist near me

- Homeschooling parents experienced increased depression and anxiety during COVID-19 lockdowns, compared to childless couples.

- Homeschooling parents experienced increased conflict in their romantic relationships.

- Homeschooling parents experienced increased pandemic-specific stress and often resorted to alcohol and cannabis to cope.

Think back to March 2020—almost overnight, our lives turned upside down. The COVID-19 pandemic quickly spread, and the effects of the lockdowns followed.

Many parents once responsible for simply dropping off their kids at school now had to take on the roles of both parent and teacher, at least in part. From providing around-the-clock childcare to, in some cases, teaching children with different needs and grade levels, many parents had a whole new task on their plates: homeschooling.

When schools closed, the level of support offered by the school system varied widely across Canada, the country in which I live. Some children had a full day of online classes; some had a few hours of teaching and then "homework" to do on their own; and some were merely given a week's worth of material to cover at their own discretion.

No matter the method, many parents were left wrangling kids in front of a computer, making sure they stayed there, and often answering questions along the way. This was a true challenge because parents were already facing their own transitions to work from home and, let's face it, a computer screen doesn't offer the same kinds of stimulation a real classroom does.

Effects of COVID-19 Mandatory Homeschooling on Parenting, Relationships, and Mental Health

This unprecedented event led my colleagues and me to wonder: How did mandatory homeschooling affect Canadian couples’ mental health during COVID-19 lockdowns?

So, we conducted a study to answer this question. We compared the anxiety , depression , alcohol misuse, cannabis misuse, and coping mechanisms of couples with children in grades 1-12, whom they homeschooled, vs. couples without children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Here’s what we found:

1. Homeschooling was associated with increased depression and anxiety.

The more time parents spent homeschooling, the more anxiety and depression they experienced.

Overall, research shows adults with children experienced poorer mental health during lockdowns than those without. Our research indicates that this is likely correlated with the stress and demands of mandatory homeschooling.

2. Homeschooling was linked to increased COVID-19-specific stress.

On top of increased depression and anxiety, COVID-19–specific distress, such as socioeconomic struggles and traumatic stress, also went up the longer parents spent homeschooling their children. Adults were required to spend more time and energy parenting while navigating increased financial pressure and fear around current events. On top of it all, many parents didn’t have access to childcare or other resources they once relied on for support.

3. Homeschooling parents reported lower optimism .

Homeschooling couples also experienced lower optimism than those without kids. Constant exposure to stress can wear us down, leading us down a path of pessimism and depression.

4. Homeschooling parents reported using alcohol and cannabis more to cope with stress.

Adults often turn to substances like alcohol and cannabis during times of stress—and the pandemic and lockdowns created constant parenting stress for many. Our research found that homeschooling couples reported higher levels of coping with alcohol and cannabis for their increased anxiety, depression, and COVID-19-related stress.

5. One parent's homeschooling was correlated with the other partner's increased alcohol use.

Homeschooling likely affected more than parenting—it appeared to affect relationships, too. The more time a parent spent homeschooling, the more they reported that their partner turned to alcohol as a coping mechanism. These changes in parenting and family dynamics greatly affected relationships and individuals’ mental health.

Support and Relief for Parenting and Post-Pandemic Stress

Even with lockdowns lifted, the effects of the pandemic still impact our families, relationships, and parenting experiences today. We’re still struggling to figure out what the “new normal” is, but at least we now know that there is light at the end of the tunnel. Schools are open again, as are restaurants, theatres, stores, and other activities where we can spend time with friends and blow off steam.

What can stressed-out parents do? Take pride in knowing that you are resilient and coped during a global crisis. Take time to appreciate the things you missed when you were homebound, including your social circle and the world outdoors. And, if things still seem bleak, take care of yourself and reach out for help if you need it— therapy can help.

Deacon, S. H., Rodriguez, L. M., Elgendi, M., King, F. E., Nogueira-Arjona, R., Sherry, S. B., & Stewart, S. H. (2021). Parenting through a pandemic: Mental health and substance use consequences of mandated homeschooling. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 10 (4), 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/cfp0000171

Simon Sherry, Ph.D. , is a psychology professor at Dalhousie University. He is also a clinical psychologist at CRUX Psychology, a Canadian-based psychology practice offering online and in person services.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Open access

- Published: 17 January 2022

Psychosocial impacts of home-schooling on parents and caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Alison L. Calear 1 ,

- Sonia McCallum 1 ,

- Alyssa R. Morse 1 ,

- Michelle Banfield 1 ,

- Amelia Gulliver 1 ,

- Nicolas Cherbuin 2 ,

- Louise M. Farrer 1 ,

- Kristen Murray 3 ,

- Rachael M. Rodney Harris 4 , 5 &

- Philip J. Batterham 1

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 119 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

26k Accesses

29 Citations

28 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic has been highly disruptive, with the closure of schools causing sudden shifts for students, educators and parents/caregivers to remote learning from home (home-schooling). Limited research has focused on home-schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic, with most research to date being descriptive in nature. The aim of the current study was to comprehensively quantify the psychosocial impacts of home-schooling on parents and other caregivers, and identify factors associated with better outcomes.

A nationally representative sample of 1,296 Australian adults was recruited at the beginning of Australian COVID-19 restrictions in late-March 2020, and followed up every two weeks. Data for the current study were drawn from waves two and three. Surveys assessed psychosocial outcomes of psychological distress, work and social impairment, and wellbeing, as well as a range of home-schooling factors.

Parents and caregivers who were home-schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic experienced significantly higher levels of psychological distress and work/social impairment compared to those who were not home-schooling or had no school-aged children. A current mental health diagnosis or lower levels of perceived support from their child’s school negatively affected levels of psychological distress, work and social impairment, and wellbeing in parents and caregivers involved in home-schooling.

Conclusions

The mental health impacts of home-schooling were high and may rise as periods of home-schooling increase in frequency and duration. Recognising and acknowledging the challenges of home-schooling is important, and should be included in psychosocial assessments of wellbeing during periods of school closure. Emotional and instrumental support is needed for those involved in home-schooling, as perceived levels of support is associated with improved outcomes. Proactive planning by schools to support parents may promote better outcomes and improved home-schooling experiences for students.

Peer Review reports

By the end of March 2020, many countries had implemented strict physical distancing policies, including large-scale or national closure of schools, to reduce the transmission of COVID-19 [ 1 ]. According to the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), by the beginning of April 2020 an estimated 172 countries had instituted nation-wide school closures affecting over 1.4 billion learners [ 2 ]. In response, educators had to adapt curriculum and implement new modes of delivery to enable students to participate in remote learning from home (hereafter termed home-schooling), while parents and other caregivers had to manage the supervision of home-schooling alongside their other professional, personal, and parenting roles [ 3 , 4 ]. In Australia, schools closed nationally to the majority of students at the end of March 2020, with select schools remaining open for vulnerable children, based on young age, social disadvantage, or specific needs [ 5 ], and those whose parents or caregivers were healthcare or other essential frontline workers.

For many parents and caregivers, home-schooling has placed considerable demands on time. It has often required them to balance multiple competing and unfamiliar roles without the usual support of grandparents, or other extended family, friends or teachers [ 3 , 6 ]. The challenges of home-schooling may be exacerbated by pressure to continue to work from home to keep jobs and businesses running [ 6 ]. As a result, some parents and caregivers have had to work longer hours each day to meet work and home-schooling obligations, potentially affecting sleep and reducing time for leisure activities [ 3 , 7 ].

The availability of resources for schools and families, such as electronic devices and adequate internet service, has also likely impacted home-schooling experiences. Carers of younger school-aged children or those with additional needs may have been particularly affected, as these children typically require closer supervision to complete home-schooling activities. A study in Hong Kong that surveyed parents about their experiences of home-schooling reported that only 14% of primary school students could complete activities without assistance [ 4 ].

School closures have been a highly disruptive element of the COVID-19 pandemic, altering the day-to-day lives of children and families. The sudden shift to home-schooling and the challenges it has presented based on factors such as the age and ability of their child(ren), parental income, living conditions (crowded housing or homelessness), and available additional support has placed added pressure on parents and caregivers [ 3 , 8 ]. In addition, the impact of home-schooling has not been evenly distributed, with caregivers of children with disabilities and diverse educational needs facing higher rates of stress and mental health problems [ 7 , 9 ]. In turn, increased parental stress may have negatively affected their mental health, the parent-child relationship, and the emotional wellbeing of the child [ 3 , 4 ]. These factors may have also impacted educational attainment [ 5 ].

Given the ongoing COVID-19 lockdowns internationally, and the potential for future pandemics and other system shocks (e.g., fires, floods, earthquakes), there is a clear need to comprehensively quantify the psychosocial impacts of home-schooling on parents and other caregivers, and to investigate individual and environmental characteristics that exacerbate them. Therefore, the current study aimed to (1) assess the impact of home-schooling on parent/caregiver psychological distress, work and social impairment, and wellbeing; and (2) identify factors associated with psychological distress, work and social impairment, and wellbeing among those engaged in home-schooling.

Participants and procedure

The Australian National COVID-19 Mental Health, Behaviour and Risk Communication (COVID-MHBRC) survey was established to longitudinally assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a representative sample of Australian adults aged 18 years and over [ 10 ]. The study consisted of seven waves of data collection, which were completed online on a fortnightly basis and administered through Qualtrics Research Services. Participants were emailed an invitation to complete each survey and were provided a one-week window in which to complete it. Participants received up to five reminders to complete a survey during the week of data collection. Quota sampling was used to obtain a sample of the Australian population from market research panels that was representative on the bases of age group, gender and State/Territory of residence. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation in the study. The current study was approved by The Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol 2020/152) and the full study protocol is available online ( https://psychology.anu.edu.au/files/COVID_MHBRCS_protocol.pdf ).

The first wave of data collection commenced on the 28th March 2020 ( N =1296). Besides demographics and background variables (collected in Wave 1), data for the current study were drawn from waves two (home-schooling variables) and three (mental health outcomes) collected between the 11th and 30th April 2020. Over 73% of the initial sample was retained at Wave 2 (W2; N =969). Attrition across subsequent waves was lower, consistently retaining over 90% wave-on-wave ( N W3=952, W4=910, W5=874; W6=820; W7=762).

Psychological Distress

The five-item Distress Questionnaire-5 (DQ5; [ 11 ]) was measured at wave 3 and used to assess psychological distress over the past two weeks. Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). Total scale scores ranged from 5 to 25, with higher scores indicating greater psychological distress. The scale had very good internal consistency in the current study sample (α = 0.93).

Work and social impairment

The extent to which work and social activities were impaired by COVID-19 was measured at wave 3 using the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; [ 12 ]). Participants were asked to rate the level of impairment COVID-19 had caused for five work and social domains (ability to work, home management, social leisure activities, private leisure activities, and ability to form and maintain close relationships) on a 9-point scale ranging from 0 (Not at all impaired) to 8 (Very severely impaired). Total scores on this scale ranged from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicative of greater work and social impairment as a result of COVID-19. The WSAS had very good internal consistency in the current study sample (α = 0.77).

Subjective wellbeing during the past two weeks was assessed at wave 3 using the 5-item World Health Organization Wellbeing Index (WHO-5; [ 13 ]). Items were responded to on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (At no time) to 5 (All of the time), multiplied by four to obtain total scale scores ranging between 0 and 100. Higher scores are indicative of greater wellbeing. The scale had very good internal consistency (α = 0.93).

Home-schooling factors

A range of factors associated with home-schooling were also assessed at wave 2 among respondents who reported home-schooling their children due to COVID-19. Respondents to these items could include parents, grandparents, or other caregivers, and included items on the school level of children (primary school/ secondary school), working from home (yes/no), sharing of home-schooling duties (yes/no), and perceived impact on work/daily activity (4-point scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘a lot’). The amount of support received from the school was also collated (e.g., online social interactions with teachers and/or peers; real-time lessons; pre-recorded teacher instruction videos; structured activities; list of optional activities; connected with other parents), with total scores on this item ranging from 0 to 6. The perceived support received from the school was assessed based on perceptions of school flexibility (e.g., advice from the school to do what best suits each family), how the school facilitated connection to peers, whether the school helped families to enjoy home-schooling, or whether the school caused parents to feel stress or worry about home-schooling. These four items were assessed on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely) and could range from 0 to 16 with higher scores indicating greater perceived support.

Demographic and background variables

At wave 1 participants also provided details on their age, gender, and level of educational attainment (Secondary school, certificate/diploma, Bachelor’s degree, higher degree [e.g., PhD]). Participants were also asked if they had ever been diagnosed (past/current) by a clinician (e.g., general practitioner, psychologist, psychiatrist) with anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, autism spectrum disorder, alcohol or substance use disorder, eating disorder, or other mental disorder (specify). For the purposes of the current study, these items were combined into a single variable assessing mental health diagnosis history (none/past/current).

Statistical analysis

Between-subject ANOVAs were conducted to compare participants who were home-schooling, with those who had children but were not home-schooling them (‘not home-schooling’) and those who did not have school-aged children, on the key psychosocial outcomes of (i) psychological distress, (ii) work and social impairment, and (iii) wellbeing. A series of linear regression analyses were conducted to identify if demographic, background and home-schooling variables collected at wave 2 were associated with higher levels of psychological distress and work and social impairment, and lower levels of wellbeing measured at wave 3.

Impact on psychosocial outcomes

Table 1 presents participant characteristics according to home-schooling status. For demographic factors, participants who reported home-schooling their children were significantly younger and more likely to have a Bachelor’s degree than participants without school-aged children or those not home-schooling their children. There were no significant differences between the three groups in terms of gender or mental health diagnosis.

The impact of home-schooling on psychological distress, work/social impairment and wellbeing at wave 3 is also presented in Table 1 . On average, home-schooling participants scored 1.6 points higher (Cohen’s d = 0.32) on the DQ5 measure of psychological distress, F (2,872)=7.19, p = 0.001, and 3.5 points higher ( d = 0.38) on the WSAS measure of work/social impairment, F (2,869)=9.90, p <0.001, compared to participants who were not home-schooling. No differences were observed in levels of wellbeing between groups, F (2,873)=0.35, p = 0.704.

Factors associated with psychosocial outcomes among participants who home-schooled

Table 2 presents a summary of the home-schooling variables. The majority of home-schooling participants reported having at least one primary-school aged child (65.4%), while just over half reported working from home while home-schooling (53.8%) and/or sharing the home-schooling duties with another adult (51%). A little under half of home-schooling participants perceived home-schooling to have had some or much impact on their work or daily activities. On average, participants received two home-schooling supports from their school (e.g., structured activities).

Table 3 presents the results of the linear regression analyses. Higher levels of psychological distress were significantly associated with a current mental health diagnosis, lower levels of educational attainment, greater perceptions that home-schooling was having an impact on work and daily activities, and lower levels of perceived support from their child’s school. Higher levels of work and social impairment were significantly associated with a current mental health diagnosis, male gender, younger age, and lower levels of perceived support from their child’s school. Lastly, lower levels of wellbeing were significantly associated with past and current mental health diagnosis, and lower levels of perceived support from their child’s school.

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to comprehensively assess and quantify the psychosocial effects of home-schooling on parents and other caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, this study found that parents and caregivers who were home-schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic experienced higher levels of psychological distress and work/social impairment than those who were not home-schooling or had no school-aged children. Among those home-schooling, younger people with less education and a history of mental health problems had higher psychological distress and lower wellbeing. Work/social impairment was additionally associated with being male. Those who perceived home-schooling to have a higher impact on work and daily activities, and those who believed they had lower levels of support from the school, also experienced greater distress and work/social impairments. This key finding highlights the importance of communication between schools and parents in the context of home-schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, the need to acknowledge and support the diverse challenges faced when home-schooling, such as enabling flexibility in expectations and activities.

The findings are consistent with qualitative research suggesting that home-schooling puts enormous time demands and pressure on people who are required to fulfil multiple, and sometimes conflicting, roles [ 3 , 4 ]. For many parents and caregivers, the time needed to undertake home-schooling duties has adversely impacted their ability to work, or led to a reduction or reallocation of work hours, which may have also reduced their ability to engage in home management and leisure activities [ 3 , 7 ]. The distress, lowered wellbeing, and lack of support felt by parents during this time has likely been amplified by financial concerns, worries about the health risks of COVID-19, and the inability to draw on usual social networks for support, such as grandparents, friends and other family members, due to strict physical distancing restrictions during the pandemic [ 3 , 6 ]. The available “down-time” during this period may have been significantly reduced for many parents and caregivers and this is reflected in increased psychological distress, and work and social impairment.

The current study also found that the levels of psychological distress, work and social impairment, and wellbeing experienced by participants who were home-schooling during the pandemic was negatively affected by a current or past mental health diagnosis. People experiencing mental health difficulties may already have a reduced capacity to cope with stress and uncertainty [ 14 , 15 ]. As the COVID-19 pandemic progresses, and in future major crises, this points to a need to identify people who are highly likely to struggle with the additional responsibilities of home-schooling and ensure tailored support is available to minimise distress and maximise educational outcomes for children.

The importance of support is reinforced by the finding that perceived support from the child’s school was consistently related to all three psychosocial outcomes. Participants who reported higher perceived support from their child’s school tended to report lower levels of distress and impairment, and higher levels of wellbeing. This finding is in line with the wider mental health literature that associates social support with better mental health outcomes [ 16 ]. Specifically, it points to the importance of providing all schools with the capacity to deliver the required practical and social support, and appropriate resources to parents and caregivers, during enforced periods of home-schooling, with attention paid to factors that may increase vulnerability to distress. Support may include simple recognition of the challenges faced by non-teachers in education delivery, and reassurance that parents’ and caregivers’ efforts to support their children’s learning are “enough.” Further, cooperation and flexibility from workplaces to ensure parents and caregivers, especially those with a history of mental health problems and/or with young children requiring significant learning support, is also likely to reduce distress and perceived impairments.

Higher psychological distress was also associated with lower levels of educational attainment and higher perceived impact of home-schooling on work and daily activities. Parents and caregivers with lower levels of education may have been less confident in their ability to support learning or found it more challenging due to lower literacy or numeracy skills [ 17 ]. Higher perceptions of the negative impacts of home-schooling may have led to feelings of being overwhelmed or reduced feelings of control. This risks further entrenching the social disadvantage already prevalent in those with lower levels of education. Higher levels of work and social impairment were also observed in males and younger participants. Males may have been less accustomed to flexible work arrangements [ 18 ], as women are often the primary carers of children, or their positions may have been less amenable to home-schooling disruptions and thus they perceived greater impairments to their work and social functioning. Younger parents and caregivers may have been more likely to have younger children, and thus the time requirement and pressure on them to actively participate in remote home learning activities may have been greater and potentially more disruptive.

Recognising and acknowledging the challenges of home-schooling is important, and should be included in psychosocial assessments of wellbeing during periods of school closure. There is a clear need to provide emotional and instrumental support to parents and other caregivers during school closures so that they can manage all roles effectively, and minimise adverse psychosocial effects. Parents and caregivers need access to support from social networks if available [ 16 ], and need schools to communicate realistic expectations, provide adequate educational activities, and supportive feedback that accounts for the unequal spread of perceived impact. Similarly, as teachers are the primary point of contact for students during remote learning, they need to be adequately supported during this time so that they can be available to effectively support students and parents. Whilst the unexpected school closures as a result of COVID-19 necessitated a rapid response to educational support materials that may have been less than ideal in some cases, as the pandemic progresses, it is critical to record and act upon lessons learned about activities that facilitate supported and independent learning for children, and provide greater support for parents and caregivers who are not educators and trying to balance work responsibilities. This is particularly the case for parents and caregivers who may face additional struggles, including those with mental health issues or with lower levels of education, that may undermine confidence or ability to home-school [ 4 ] and perpetuate social disadvantage.

The current study has several strengths. Firstly, the data were collected at the peak of home-schooling in Australia in a generally representative population sample. Secondly, data were collected over multiple time points, reinforcing the temporal effects of the findings. However, the study also has some limitations. Although the study was designed to be representative of the Australian population, it is likely that under-privileged groups - those with low income, educational attainment, and employment - were not adequately represented and may have been even more affected by home-schooling [ 19 ]. We also did not separately consider the impacts of home-schooling on families with multiple children or on those who had children with a disability or diverse educational needs. Time-poor parents may be less inclined to participate in research panels, so the findings may provide a conservative estimate of the impacts of home-schooling on busy parents.

In summary, parents and caregivers engaged in home-schooling during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic reported higher levels of psychological distress and work and social impairment than their non-home-schooling peers – both those without school-aged children and those with children still in school. People who were younger, male, had a history of mental health difficulties and/or perceived the impacts of home-schooling on work and daily activities to be higher, or the support of schools to be lower, were particularly affected. Understanding the impacts of home-schooling on parents and caregivers is critical, as periods of home-schooling are likely to continue into the future. In addition, the functioning of parents and caregivers can impact upon the parent-child relationship, child wellbeing and potentially the academic outcomes of children during periods of lock-down.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Viner RM, Russell SJ, Croker H, Packer J, Ward J, Stansfield C, et al. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:397–404.

Article CAS Google Scholar

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. COVID-19 educational disruption and response 2020 [Available from: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse .

Griffith AK. Parental burnout and child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Violence. 2020:1–7.

Lau EYH, Lee K. Parents’ views on young children’s distance learning and screen time during COVID-19 class suspension in Hong Kong. Early Education and Development. 2020.

Brown N, Te Riele K, Shelley B, Woodroffe J. Learning at home during COVID-19: Effects on vulnerable young Australians. Hobart: Peter Underwood Centre for Educational Attainment, University of Tasmania; 2020.

Google Scholar

Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14:20.

Article Google Scholar

Evans S, Mikocka-Walus A, Klas A, Olive L, Sciberras E, Karantzas G, et al. From “It has stopped our lives” to “Spending more time together has strengthened bonds”: The varied experiences of Australian families during COVID-19. Front Psychol. 2020;11:588667.

Cluver L, Lachman JM, Sherr L, Wessels I, Krug E, Rakotomalala S, et al. Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:e64.

Chafouleas SM, Iovino EA. Initial impact of COVID-19 on the well-being of caregivers of children with and without disabilities. Storrs, CT: UConn Collaboratory on School and Child Health; 2020.

Dawel A, Shou Y, Smithson M, Cherbuin N, Banfield M, Calear AL, et al. The effect of COVID-19 on mental health and wellbeing in a representative sample of Australian adults. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:579985.

Batterham PJ, Sunderland M, Carragher N, Calear AL, Mackinnon AJ, Slade T. The Distress Questionnaire-5: Population screener for psychological distress was more accurate than the K6/K10. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;71:35–42.

Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JH. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–4.

Topp CW, Ostergaard SD, Sondergaard S, Bech P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84:167–76.

Boelen PA, Lenferink LIM. Latent class analysis of indicators of intolerance of uncertainty. Scand J Psychol. 2018;59:243–51.

Yook K, Kim KH, Suh SY, Lee KS. Intolerance of uncertainty, worry, and rumination in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:623–8.

Gariépy G, Honkaniemi H, Quesnel-Vallée A. Social support and protection from depression: Systematic review of current findings in Western countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209:284–293.

Lamb S. Impact of learning from home on educational outcomes for disadvantaged children: Brief assessment. Victoria: Centre for International Research on Education Systems; 2020.

Ewald A, Gilbert E, Huppatz K. Fathering and flexible working arrangements: A systematic interdisciplinary review. J Fam Theory Rev. 2020;12:27–40.

Thomas J, Barraket J, Wilson C, Ewing S, MacDonald T, Tucker J, et al. Measuring Australia’s digital divide: The Australian digital inclusion index Melbourne: RMIT University; 2017.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the other team members of The Australian National COVID-19 Mental Health, Behaviour and Risk Communication survey who also contributed to the design and management of the study.

This project was supported by funding from the College of Health and Medicine at the Australian National University. ALC is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) fellowships 1173146. LMF is supported by Australian Research Council DECRA DE190101382. PJB is supported by NHMRC Fellowship 1158707. The funding body did not have a role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the paper; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Mental Health Research, Research School of Population Health, The Australian National University, 63 Eggleston Road, ACT 2601, Acton, Australia

Alison L. Calear, Sonia McCallum, Alyssa R. Morse, Michelle Banfield, Amelia Gulliver, Louise M. Farrer & Philip J. Batterham

Centre for Research on Ageing, Health and Wellbeing, Research School of Population Health, The Australian National University, Acton, Australia

Nicolas Cherbuin

Research School of Psychology, The Australian National University, Acton, Australia

Kristen Murray

National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Research School of Population Health, The Australian National University, Acton, Australia

Rachael M. Rodney Harris

Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Acton, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ALC, SM, ARM, and PJB were involved in formulating the research question, and designing the study. PJB analysed the data. All authors were involved in the design and conduct of the survey. ALC drafted the article, and all authors contributed to the writing and critical editing of the article. All authors approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alison L. Calear .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The ethical aspects of this study were approved by The Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol 2020/152) and conforms to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Calear, A.L., McCallum, S., Morse, A.R. et al. Psychosocial impacts of home-schooling on parents and caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 22 , 119 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12532-2

Download citation

Received : 12 October 2021

Accepted : 06 January 2022

Published : 17 January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12532-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Psychological distress

- Home-schooling

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- News & Announcements

- Subscribe to Taubman Center

- Journal Articles

- Policy Briefs

- Working Papers

- Autonomous Vehicles Policy Initiative

- Government Performance Lab

- Program on Crisis Leadership

- Program on Education Policy and Governance

- Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston

- Tony Gómez-Ibáñez Summer Fellowship Application

- Economic Development Post Graduate Fellowship

- Economic Development Seminar

- Transition Term

- The Taubman Center Urban Prize

- Student Treks

- Post-Pandemic Future of Homeschooling

In This Section

- A Modern Teaching Profession: Compensation, Preparation, Representation, Evaluation

- Colloquium Series

- Emerging School Models: Moving from Alternative to Mainstream

- Should School Boards Run Schools?

- Charting New Terrain: A Conference on Emerging School Models

- A Safe Place to Learn: Responding to Concerns about School Safety

- Conversations on Education in a Federal System

- School Choice in the Post-Pandemic Era

- Closing the Education Opportunity Gap: Strategies and Challenges

May 6 — June 17, 2021

Homeschooling has been undergoing a transformation in recent years. In the wake of Covid-19, early evidence also indicates that millions of parents began homeschooling during recent school closures. However, as homeschooling evolves, there remain many important questions about the practice. The purpose of this conference is to improve understanding of critical topics in homeschooling by considering empirical research, expert analysis, and parents’ experiences with homeschooling.

Podcast: Reactions to the Homeschooling Conference

Will the increase in homeschooling continue after the end of the pandemic? Should homeschooling be more tightly regulated? Paul E. Peterson and Daniel Hamlin discuss these questions and more following the completion of the Conference on the Post-Pandemic Future of Homeschooling.

Agenda and Video

Moderators Paul E. Peterson, Director, Program on Education Policy and Governance, Harvard University Daniel Hamlin, Professor, University of Oklahoma

Is it time for a change to homeschool law?

Does the law on homeschooling need to be revised? What are appropriate restrictions on homeschooling? What rights should homeschoolers have?

Panelists Elizabeth Bartholet, Professor, Harvard Law School Michael Donnelly, Senior Counsel, Homeschool Legal Defense Association Eric Wearne, Professor, Kennesaw State University James Dwyer, Professor, College of William and Mary

Michael Donnelly's slides from this presentation are available here .

Growth and diversity in post-pandemic homeschooling

What is homeschooling? Who homeschools their children? Has Covid-19 altered the homeschooling landscape?

Panelists Sarah Grady, Statistician, US Department of Education Brian Ray, President, National Home Education Research Institute

Commentator Cheryl Fields Smith, Professor, University of Georgia

Sarah Grady's slides from this presentation are available here . Brian Ray's slides from this presentation are available here .

Are homeschoolers prepared for life?

How is the academic preparation of homeschoolers? What trends do they see in life outcomes?

Panelists Christian Wilkens, Professor, State University of New York, Brockport Jennifer Jolly, Professor, University of Alabama

Commentator Robert Kunzman, Professor, Indiana University

Christian Wilkens' and Jennifer Jolly's slides from this presentation are available here .

Are homeschoolers socially isolated?

How involved are homeschoolers in their local communities?

Panelists Daniel Hamlin, Professor, University of Oklahoma David Sikkink, Professor, University of Notre Dame

Commentator Michael McShane, Director of National Research, EdChoice

Daniel Hamlin's slides from this presentation are available here .

Is child abuse greater at school or homeschool?

What do we know about the incidence of child and sexual abuse that occurs in schools and in homeschool households?

Panelists Charol Shakeshaft, Professor, Virginia Commonwealth University Angela Dills, Professor, Western Carolina University

Commentator Martin West, Professor, Harvard Graduate School of Education

Charol Shakeshaft's slides from this presentation are available here . Angela Dills' slides from this presentation are available here .

Is homeschooling an international movement?

What trends in homeschooling are occurring internationally?

Panelists Ari Neuman & Oz Guterman, Professors, Western Galilee College Philippe Bongrand, Professor, CY Cergy Paris University Christine Brabant, Professor, University of Montreal

Commentator Albert Cheng, Professor, University of Arkansas

Ari Neuman's and Oz Guterman's slides from this presentation are available here . Philippe Bongrand's slides from this presentation are available here . Christine Brabant's slides from this presentation are available here . Works referenced by Albert Cheng are available here .

Parents’ experiences with homeschooling

What is it like to homeschool? What are the reasons? Has Covid-19 changed the homeschooling experience?

Lead Panelist Michael Horn, Co-Founder, Clayton Christensen Institute and Homeschooling Parent

Parent Panelists Valerie Bryant Caprice Corona Karen Dematos Ann McClure Douglas Pietersma

Homeschooling Up, Public Schooling Down during COVID-19, BU-Aided Research Finds, with Implications for School Reform

Findings suggest the need for school ref.

BU research shows that a notable surge in homeschooling occurred last year, as some American parents shunned in-person learning at public schools. Photo by nicomenijes/iStock

Homeschooling Up, Public Schooling Down during COVID-19, BU-Aided Research Finds

Findings suggest the need for school reforms, rich barlow.

It’s old news that the pandemic forced students into remote learning last year. But a BU-aided study adds a new twist: COVID-19 also drove many parents to remove their children from public schools altogether in favor of homeschooling or private schools.

The study came from a multi-institution team that included two Wheelock College of Education & Human Development scholars: Andrew Bacher-Hicks , an assistant professor of education policy, and Joshua Goodman , an associate professor of education and economics (with a joint appointment in the College of Arts & Sciences).

The researchers looked at student data gathered by the federal government and the state of Michigan, which warehouses additional information not collected by the feds. In fall 2020, public school enrollment in the Wolverine State dropped by 10 percent among kindergarteners; overall, kindergarten-through-12th grade enrollments fell 3 percent. Most of those students were homeschooled, the researchers found, with the biggest spikes in districts where public schools maintained in-person instruction. The rest moved to private schools.

Bacher-Hicks and Goodman recently discussed their findings with BU Today.

BU Today: You list Michigan’s percentages for shifts to homeschooling and private schooling in fall 2020. Did the same percentages occur nationally?

Bacher-Hicks: Yes. The trends that are possible to compare between national data and Michigan data are quite similar. For example, we find that enrollment declined by 3 percent among K-12 students and 10 percent among kindergartners in Michigan. National statistics are nearly identical. However, the Michigan data provide substantially more detail than data at the national level. For example, national data do not track student movement to private schools, which was something we were able to do in our Michigan analysis.

BU Today: Do you have any data on fall 2021, in terms of whether those people returned to public schools?

Goodman: One limitation to using these detailed records is that they are often not available in real time. We are eager to examine trends in real time, but detailed data for the fall of 2021 are not yet available.

BU Today: At some point, the pandemic will end. Might public school enrollments gradually return to pre-pandemic levels?

Bacher-Hicks: Absolutely. Some students who left the public school system during the pandemic will certainly return. The question is how many will return and whether they will all return at once or if reenrollment will be more gradual. Our research shows that sharpest declines in public school enrollment occurred in the earliest grades, particularly kindergarten. This suggests that the implications of returns to pre-pandemic levels will be most important for elementary schools. I suspect that we will begin hearing news reports of overall student enrollment counts from the fall of 2021 semester, which will begin to answer this question.

I think improving access to online learning—such as investing in broadband—will be an increasingly important strategy. Andrew Bacher-Hicks

BU Today: Homeschooling to avoid in-person learning during a pandemic makes sense, but why did some families merely shift to private school? Were private schools more likely to offer remote options?

Goodman: Though we can’t test this directly with our data, other studies have found that private schools were more likely to offer in-person instruction than public schools. In our study, we found that there were relatively larger shifts to private schooling among areas where the public school system offered only remote learning, suggesting that some families sought out in-person learning when the public education system did not offer it.

BU Today: What are the policy indications of your findings—what should states and school districts be doing? Is universal broadband access one of them, to redress the fact that some students cannot study remotely easily, or at all?

Bacher-Hicks: Absolutely. I think improving access to online learning—such as investing in broadband—will be an increasingly important strategy for equalizing learning opportunities. A prior study that we published earlier this year found that demand for online learning resources increased sharply during the pandemic, but that it was concentrated among more affluent geographic areas with high levels of existing broadband connections.

Goodman: Another key policy implication is that states and districts need to be prepared for lower than average student enrollments in the near term, but a rebound at some point. This means that the public education sector will need to be more nimble than in the past to make sure classrooms are fully staffed with effective educators. It may also suggest that state and local policymakers need to respond more effectively to future crises if public schools want to retain and attract families who have alternative schooling options.

Explore Related Topics:

- Share this story

- 0 Comments Add

Homeschooling Rising, Public Schooling Down during COVID-19, BU-Aided Research Finds

Senior Writer

Rich Barlow is a senior writer at BU Today and Bostonia magazine. Perhaps the only native of Trenton, N.J., who will volunteer his birthplace without police interrogation, he graduated from Dartmouth College, spent 20 years as a small-town newspaper reporter, and is a former Boston Globe religion columnist, book reviewer, and occasional op-ed contributor. Profile

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

Post a comment. Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Latest from BU Today

Dean sandro galea leaving bu’s school of public health for washu opportunity, stitching together the past, two bu faculty honored with outstanding teaching awards, advice to the class of 2024: “say thank you”, school of visual arts annual bfa thesis exhibitions celebrate works by 33 bfa seniors, killers of the flower moon author, and bu alum, david grann will be bu’s 151st commencement speaker, photos of the month: a look back at april at bu, q&a: why are so many people leaving massachusetts, bu track and field teams compete at 2024 patriot league outdoor championships this weekend, 22 charles river campus faculty promoted to full professor, this year’s commencement speaker we’ll find out thursday morning, the weekender: may 2 to 5, how to have ‘the talk’: what i’ve learned about discussing sex, university, part-time faculty tentatively agree to new four-year contract, pov: campus antisemitism can be addressed by encouraging more speech, not less, does caitlin clark signal a new era in women’s sports, a video tour of myles standish hall, student entrepreneurs competed for a chance at $72,000 in prizes at innovate@bu’s new venture night, all of boston’s a stage, bu plays a big role in new production from boston’s company one theatre.

Homeschooling during the coronavirus pandemic could change education forever, says the OECD

Education may never be the same again, thanks to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Image: REUTERS/Lindsey Wasson

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Douglas Broom

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- Homeschooling children during the COVID-19 crisis is changing our approach to education.

- Experts believe the innovations teachers use during the outbreak may lead to lasting change, with technology playing a bigger role in schools in the future.

- But advances in e-learning must not leave the educationally disadvantaged behind.

Around the world, schools in over 100 countries are closed to protect against the spread of coronavirus, affecting the education of nearly 1 billion children . For the lucky ones, homeschooling will take the place of the classroom.

Have you read?

4 ways covid-19 could change how we educate future generations, 3 ways the coronavirus pandemic could reshape education, the world is failing miserably on access to education. here's how to change course.

In some parts of the world, it will be down to parents to keep their child's education going as best they can. But digital technologies are increasingly being used to deliver lessons to children at home.

Until the pandemic closed schools, only a minority of children were taught at home. In the United States, an estimated 1.7 million children were homeschooled out of a national school population of 56.6 million .

Today, things look very different. Around the world, schools are using existing platforms from the likes of Microsoft and Google as well as conferencing apps like Zoom to deliver lessons for their pupils. In the UK, virtual gym classes delivered by fitness instructor Joe Wicks have proved extremely popular. Meanwhile, France has created “Ma classe à la maison” (my classroom at home) , which can be accessed on devices such as a laptop or a smartphone. It provides four weeks of courses with what the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) describes as “confirmed pedagogical content”.

Education revolution?

The OECD is tracking how technology is replacing face-to-face teaching . “It is particularly inspiring to see entirely new ways of working emerging, ones that go beyond simply replacing physical schools with digital analogues,” says Tracey Burns, of the OECD Directorate for Education and Skills.

In Japan, private sector companies are offering free online courses to children in lockdown through a government digital platform which allows students and parents to choose which one they study.

“As more schools close, we must pay special attention to the most vulnerable, not just physically, but also academically and psychologically,” says Burns. “All responses must be designed to avoid deepening educational and social inequality.

“As systems massively move to e-learning, the digital divide in connectivity, access to devices and skill levels takes on more weight.”

She says it's too early to say that bricks-and-mortar schools will be replaced by e-learning anytime soon. But Andreas Schleicher, Director of Education and Skills at the OECD, sees the crisis as an opportunity to rethink how we organize education .

He argues schools and teachers should no longer be seen as “knowledge delivery systems” and that teachers should be empowered to take greater ownership of what they teach and how they teach it.

Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic requires global cooperation among governments, international organizations and the business community , which is at the centre of the World Economic Forum’s mission as the International Organization for Public-Private Cooperation.

Since its launch on 11 March, the Forum’s COVID Action Platform has brought together 1,667 stakeholders from 1,106 businesses and organizations to mitigate the risk and impact of the unprecedented global health emergency that is COVID-19.

The platform is created with the support of the World Health Organization and is open to all businesses and industry groups, as well as other stakeholders, aiming to integrate and inform joint action.

As an organization, the Forum has a track record of supporting efforts to contain epidemics. In 2017, at our Annual Meeting, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) was launched – bringing together experts from government, business, health, academia and civil society to accelerate the development of vaccines. CEPI is currently supporting the race to develop a vaccine against this strand of the coronavirus.

Empowering teachers

“I meet many people who say we cannot give teachers and education leaders greater autonomy because they lack the capacity and expertise to deliver on it,” added Schleicher. “But those asked only to reheat pre-cooked hamburgers are unlikely to become master chefs.

“Simply perpetuating our prescriptive approach to teaching will not hold up in this moment of crisis, which demands from teachers not just to replicate their lessons in another medium, but to find entirely new responses to what people learn, how people learn, where people learn and when they learn.”

Drawing on the results of the OECD’s global teaching survey TALIS , he says technology should have a much greater role in the classroom. “Technology cannot just change methods of teaching and learning, it can also elevate the role of teachers from imparting received knowledge towards working as co-creators of knowledge,” he says.

Teachers across the world told the survey a shortage of digital technology in the classroom was hindering learning. Just over half of teachers were able to let their students use computers for projects or classwork.

Only 60% of teachers had received professional development training in the use of technology and almost 20% said they had an urgent need for development in this area. But with the coronavirus pandemic giving us a glimpse of how education could evolve, this could change. Schools may never be the same again when they reopen after COVID-19.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Health and Healthcare Systems .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

5 conditions that highlight the women’s health gap

Kate Whiting

May 3, 2024

How philanthropy is empowering India's mental health sector

Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw

May 2, 2024

Immunization: How it started, how it's going – what we’ve achieved through 50 years of vaccination programmes

Shyam Bishen

May 1, 2024

70% of workers are at risk of climate-related health hazards, says the ILO

Johnny Wood

How communities can step up to provide long-term care for the world’s ageing population

Prakash Tyagi

Market failures cause antibiotic resistance. Here's how to address them

Katherine Klemperer and Anthony McDonnell

April 25, 2024

The Pandemic Has Parents Fleeing From Schools—Maybe Forever

COVID-19 is a catalyst for families who were already skeptical of the traditional school system—and are now thinking about leaving it for good.

When Sharon Jackson looks out on the mid-pandemic landscape of New York City, she sees a scary place for a sixth grader. Her daughter, Sophia, just graduated from the kind of Lower Manhattan public school where the PTA can easily raise money for iPads and SMART Boards. Jackson liked that Sophia’s days were structured, and that she was able to make a handful of close friends. The past six months, however, have left Jackson wary of how school might affect her child. For one thing, Sophia doesn’t like wearing masks. “If we go to Whole Foods, she’ll put it on, but she just feels very restricted,” Jackson told me. At home, there’s no need for such barriers: “She can do her studies in her underwear.”

Jackson has started noticing more unhoused people in the park near her apartment in Tribeca. The city “feels less safe in general to me right now,” Jackson, who is white, said, citing “the rioting, the rowdiness, the random acts of violence happening.” (While shootings have spiked in New York this summer, the overall crime rate has remained flat, and far below the high crime levels of the 1980s and ’90s, according to a recent New York Times report.) With protesters calling on the government to defund the police, she feels as if “there’s less protection” in the city. With families facing economic hardship and the city on edge, Jackson fears Sophia could be exposed to danger. “You don’t know if there’s a kid in the classroom [whose] parents are going through a tough time, and maybe that child would act out and snap and decide they want to hit another kid,” she said. And when a vaccine for COVID-19 eventually arrives, Jackson is worried that New York officials will make proof of vaccination mandatory for kids to attend public schools. “I’m not comfortable with a vaccine that’s not rigorously tested,” Jackson said. “To expose her to something that just is so questionable doesn’t seem like a sound decision.” Before the pandemic, she never wanted to homeschool her daughter. Now, she said, it seems like her best option.

COVID-19 has created a strange natural experiment in American education: Families who would have never otherwise considered taking their kids out of school feel desperate enough to try it. Reopening has been chaotic: In New York City, the start of school has been pushed back to late September, as teachers and principals scramble to prepare for a semester split between online and in-person learning, fighting to secure the extra staffing and testing needed to safely bring kids back to class.

Read: What we’ve stolen from our kids

Homeschooling organizations and consultants have faced a deluge of panicked parents frantic to find alternatives to regular school. Some families hate the idea of their kids sitting on Zoom for hours at a time. Others worry about exposing family members to the coronavirus or seeing schools close suddenly after a surge in cases. Although some of these parents will likely put their kids back in school once the pandemic is under control, homeschooling advocates see this period as an unlikely opportunity to evangelize their way of life, which they describe as more flexible, creative, and adaptable to each student than traditional school. Homeschooling families, which included roughly 3 percent of school-age children in the United States in 2016, have lots of different reasons for wanting to educate their own kids. But they’re united in a common assessment: They want out of the traditional system. The question is whether COVID-19 will cause a temporary bump in homeschooling as parents piece together their days during the pandemic or mark a permanent inflection point in education that continues long after the virus has been controlled. Some families may find that they want to exit the system for good.

Like many other students , Sophia pushed her way through the end of the school year in the spring, graduating from elementary school in a quickly coordinated Zoom ceremony. But Jackson wasn’t satisfied with the thought of another cobbled-together semester, so over the summer, she started investigating alternative options for the fall. She found her way to Joanna Allen Lodin, one of many former homeschooling moms who have set up shop as small-time sages for families interested in leaving the traditional school system. Since May, Lodin has received a “snowball” of requests for information, she told me, and has hosted one or two information sessions a week for curious families.

“I’m hearing everything, from parents who thought this spring was a disaster for their kids and who feel that they could do it better,” she said, to “people who said this spring was revelatory” and loved having their kids at home, concluding that “school is just babysitting, and I can do this better, and I’m going to homeschool them now.” The common thread, she said, is that “parents are terrified of failing their children.”

A wide range of parents are attempting to homeschool this fall, and families with experience are trying to help them along. Kristen Rhodes, a former public-school special-education teacher who lives near the Georgia-Florida border, decided not to put her 5-year-old son in kindergarten this year, because she was worried about him having to wear a mask, and instead joined a group of fellow Christian parents and kids who use a curriculum called Classical Conversations. Nicole Damick, a homeschooling mom of four in Pennsylvania, has been eager to talk up homeschooling to curious friends and acquaintances: Life is lovelier with kids around, she wrote me in an email, “instead of forcing them off every morning with a crappy sandwich to endure the small daily abuses of a system that treats them like a value-added commodity to shoot out the other end of the K–12 pipeline.” Erik and Emily Orton, who homeschooled their five kids in New York City long before the pandemic, have been fielding questions from families worried about the cost to families who hope their nanny might become their kid’s educator, which the Ortons had never heard of before COVID-19. “The larger misperception is that it’s expensive, that it’s complicated, and that it’s time-consuming,” Erik Orton told me. “In our experience, it’s none of those things.”

Read: Grandparents could ease the burden of homeschooling

The pandemic may play into some of the instincts of parents inclined toward homeschooling. There’s “this notion that school itself is kind of a risky place for children: They’re too fragile, that they’re more likely to get sick,” Mitchell Stevens, an education professor at Stanford University, told me. “If you have school anxiety about your child, COVID is your worst nightmare, because school is not a civic community; it’s a public-health risk.” American history is filled with people making the civic case for common schooling. Horace Mann, the 19th-century education reformer, argued that public school is essential for forming prudential citizens. This idea has never fully won out in American culture, however. The homeschooling world is dominated by parents “who believe that their family comes first and are less concerned with public health or the public good,” Jennifer Lois, a professor at Western Washington University, told me. These parents often “end up choosing those kind of family-first” options.

The problem is that in the chaos of the pandemic, it’s not clear how much common good any kind of school is doing. The children most likely to suffer under hybrid models of remote and in-person learning are those who don’t have access to the internet or whose parents have to work long hours outside the house, Cheryl Fields-Smith, an associate professor at the University of Georgia who studies Black homeschoolers, told me. These kids may have few other options—no matter how bad things get this fall, they’ll likely be stuck in traditional schools, while parents with more resources may decide to pursue alternatives. “I understand not wanting to send your child to school in a COVID context,” Fields-Smith said. But as families of all kinds face a potentially challenging fall, everyone seems to be in it for themselves, with no clear way to help other families thrive. “If you think about the American culture, it’s a lot of rugged individualism,” she said.

Academic studies of homeschooling tend to divide the community roughly into Christians and hippies, and Sharon Jackson falls more into the latter camp than the former. She and her husband both work as personal trainers and fitness consultants—Jackson once won second place at the Reebok National Aerobic Championship, which involves exactly as much colorful spandex as you’d imagine —and she’s not on a 9-to-5 schedule. As she read up on homeschooling, she found herself attracted to the concept of “unschooling,” which claims that children learn better when they direct their own studies, rather than following a set curriculum.

This was the argument I heard again and again from homeschooling advocates: Nontraditional schooling isn’t just about fear of regular school. It promotes academic excellence. “People have this idea in their head of what homeschooling is, and it isn’t,” Robert Bortins, the CEO of Classical Conversations, told me. “The thing people think about is the 1980s, jean-denim-skirt homeschoolers, and that’s not how it is anymore.” His company saw more than double the visitors to its website in July of this year compared with July 2019, he said. Rob and Jen Snyder, who oversee LEAH, a Christian organization that says it is the largest homeschooling group in New York, told me that they’ve gotten a huge surge in interest, building on last summer’s exodus from schools after the state repealed a religious exemption to vaccine requirements. While parents have been asking how to homeschool their children so that they can stay on track with traditional school, “there is no going back to normal,” Rob Snyder said. He believes that the pandemic will permanently reshape how parents think about school.

Read: Homeschooling without God

On every front, the pandemic has revealed the weaknesses in America’s public infrastructure: a health-care system that cannot broadly serve everyone who needs care. Sharp disparities in infection and death rates that underscore America’s existing inequalities . An education system that depends on children being together, in person, to function. Many of America’s most vulnerable families are going to spend the fall struggling through scattershot remote learning setups, assembling child-care coverage, and caring for family members who will inevitably get sick in a resurgence of cases. For people who were already inclined to doubt the system, the pandemic has just confirmed their suspicions about America. “Freedom is a state of being that is one’s birthright,” Jackson wrote me in an email. “The mainstream media just spews out propaganda to control people and a young person’s mind is so impressionable and that’s not how I want to raise Sophia.”

Even homeschooling will look different this fall, though. Around this time of year, a few hundred homeschooling families typically gather on the Great Hill in Central Park. They call it the “not-back-to-school picnic”—a chance to socialize with like-minded families who have found similar freedom in leaving traditional school behind. That won’t be happening this year, because of New York’s rules limiting large gatherings. And in normal times, many homeschoolers actually spend little time at home, so these students will feel the effects of museum closures and extracurricular-class cancellations. Still, Jackson told me that she is excited to begin Sophia’s studies. Without the pandemic, she said, “I would have just been staying in the system.”

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, remote education/homeschooling during the covid-19 pandemic, school attendance problems, and school return–teachers’ experiences and reflections.

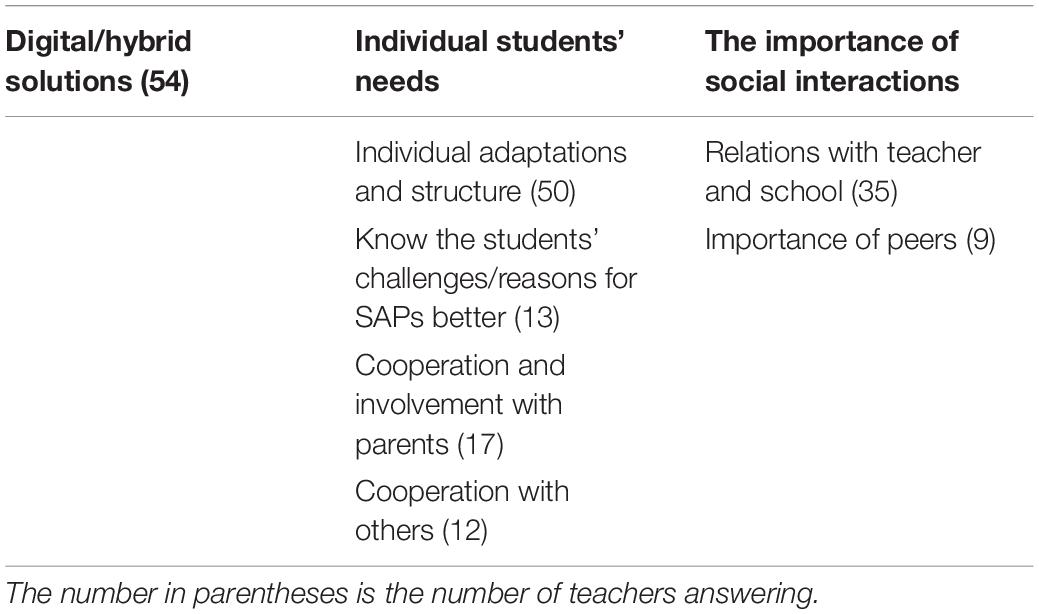

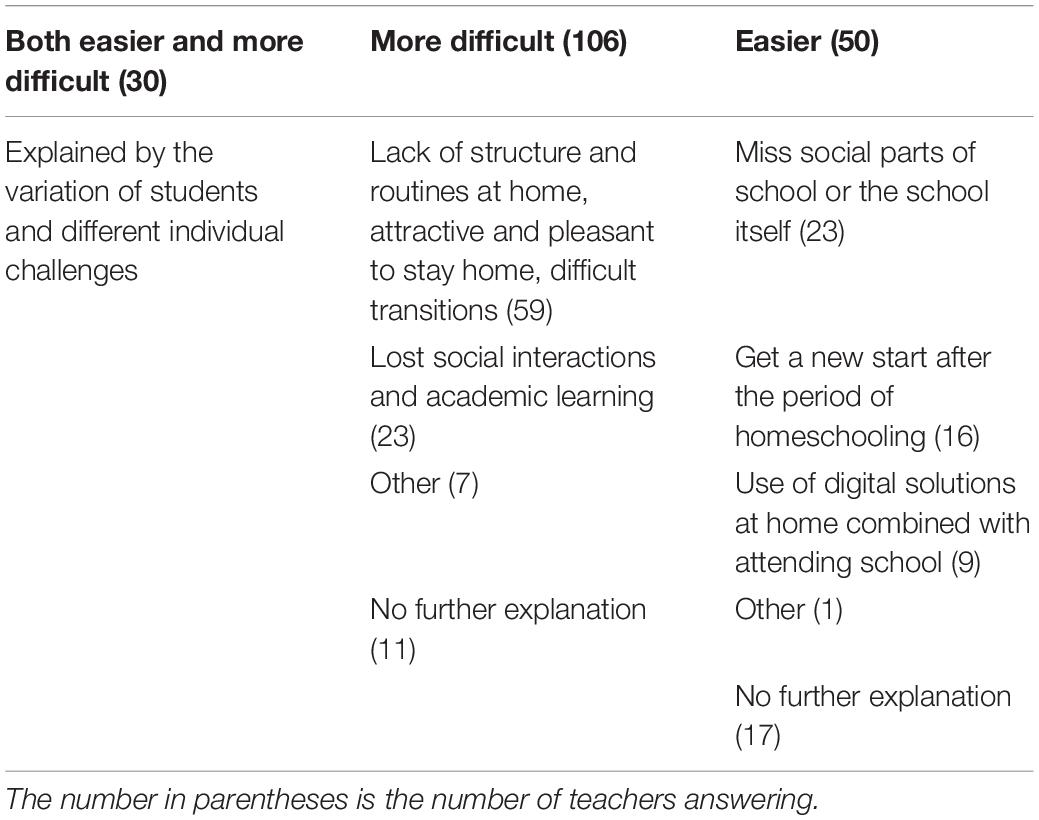

- 1 Norwegian Centre for Learning Environment and Behavioural Research in Education, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

- 2 Department of Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Regional Centre for Child and Youth Mental Health and Child Welfare, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

According to Norway’s Educational Act (§2-1), all children and youths from age 6 to 16 have a right and an obligation to attend free and inclusive education, and most of them attend public schools. Attending school is important for students’ social and academic development and learning; however, some children do not attend school caused by a myriad of possible reasons. Interventions for students with school attendance problems (SAPs) must be individually adopted for each student based on a careful assessment of the difficulties and strengths of individuals and in the student’s environment. Homeschooling might be one intervention for students with SAPs; however, researchers and stakeholders do not agree that this is an optimal intervention. Schools that were closed from the middle of March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to investigate remote education more closely. An explorative study was conducted that analyzed 248 teachers’ in-depth perspectives on how to use and integrate experiences from the period of remote education for students with SAPs when schools reopen. Moreover, teachers’ perspectives on whether school return would be harder or easier for SAP students following remote education were investigated. The teachers’ experiences might be useful when planning school return for students who have been absent for prolonged periods.

Introduction

School attendance problems (SAPs) are a concern in many countries because attending school is important for students’ academic, emotional, and social learning (e.g., Kearney, 2008 ). Home education or homeschooling is an intervention for some students who have been absent for a prolonged period, as a part of a gradual return that connects the student to school and to schoolwork at home. However, this is a controversial topic in the literature ( Kearney, 2016 ). Some researchers (e.g., McShane et al., 2004 ; Melvin and Tonge, 2012 ) claim that students should not do schoolwork at home because it is believed to prolong absence. Others (e.g., Kearney, 2016 ) argue that doing schoolwork at home might reduce the anxiety of falling behind academically and ultimately make school return easier. When schools in many countries closed in the middle of March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers had to immediately provide education at home to teach their students using various digital solutions, tools, and skills. The concept “emergency remote education” clearly separate the practice during the period of closed schools from planned practices such as distance education, e-learning, online education, homeschooling, or other concepts being used in different countries, and ( Bozkurt et al., 2020 ). 1 No national guidelines existed in Norway about how to do remote education; however, the curriculum and the Education Act were still applicable. The main aim of this study was to investigate teachers’ perspectives on how to integrate their experiences of remote education during the pandemic for students with SAPs when schools reopen and to investigate their perceptions of how the experiences from remote education could impact school return.

School Attendance Problems

Attending school is important for students’ behavioral, social, economic, and educational learning (e.g., Kearney, 2008 ; Ansari et al., 2020 ), in addition to the fact that in Norway, education is a right and an obligation from age 6 to 16 (grade level 1–10). However, SAPs are a concern in many countries, and research in this area is increasing. SAPs are usually seen as unauthorized absences, which are absences not recorded as illnesses or with permission from the school ( Dalziel and Henthorne, 2005 ). Many types of SAPs exist, such as truancy, school refusal, school withdrawal, and school exclusion (e.g., Heyne et al., 2019 ). In this study, all types of unauthorized/undocumented SAPs are included based on criteria adapted from Kearney (2008) . The reasons for SAPs are multiple and often complex ( Egger et al., 2003 ; Heyne et al., 2011 ; Ingul and Nordahl, 2013 ; Havik et al., 2014 , 2015 ; Blöte et al., 2015 ).