Political Instability And Uncertainty Loom Large In Nepal

By gaurab shumsher thapa.

- February 16, 2021

This article was originally published in South Asian Voices.

Nepal’s domestic politics have been undergoing a turbulent and significant shift. On December 20, 2020, at the recommendation of Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, President Bidya Devi Bhandari dissolved the House of Representatives, calling for snap elections in April and May 2021. Oli’s move was a result of a serious internal rift within the ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP) that threatened to depose him from power. Opposition parties and other civil society stakeholders have condemned the move as unconstitutional and several writs have been filed against the move at the Supreme Court (SC) with hearings underway. Massive protests have taken place condemning the prime minister’s move. If the SC reinstates the parliament, Oli is in course to lose the moral authority to govern and could be subject to a vote of no-confidence. If the SC validates his move, it is unclear if he would be able to return to power with a majority.

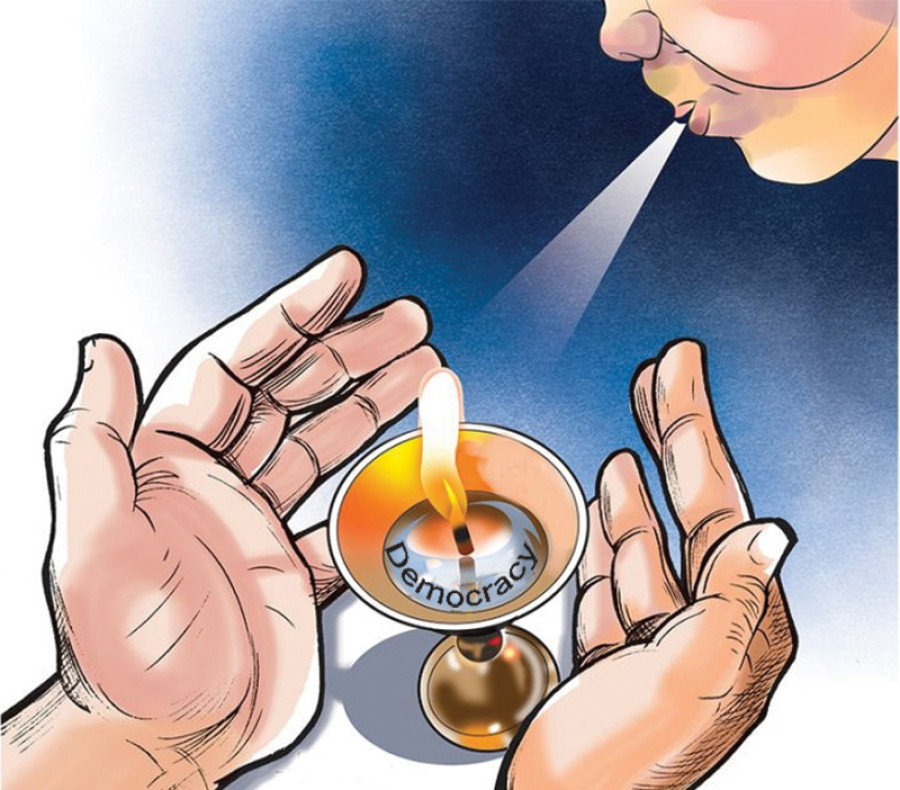

The formation of a strong government after decades of political instability was expected to lead to a socioeconomic transformation of Nepal. Regardless of the SC’s decision, the country is likely to see an escalation of political tensions in the days ahead. The internal rift that led to the December parliamentary dissolution and the political dimensions of the current predicament along with the domestic and geopolitical implications of internal political instability will lead to a serious and long-term weakening of Nepal’s democratic fabric.

Power Sharing and Legitimacy in the NCP

Differences between NCP chairs Oli and former Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal have largely premised on a power-sharing arrangement, leading to a vertical division in the party. In the December 2017 parliamentary elections, a coalition between the Oli-led Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist Leninist or UML) and the Dahal-led Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Center or MC) won nearly two-thirds of the seats. In May 2018, both parties merged to form the NCP. However, internal politics weakened this merger. While both the factions claim to represent the authentic party, the Election Commission has sought clarifications from both factions before deciding on the matter. According to the Political Party Act , the faction that can substantiate its claim by providing signatures of at least 40 percent of its central committee members is eligible to get recognized as the official party. The faction that is officially recognized will get the privilege of retaining the party and election symbol, while the unrecognized faction will have to register as a new party which can hamper its future electoral prospects. A faction led by Dahal and former Prime Minister Madahav Kumar Nepal, was planning to initiate a vote of no-confidence motion against Oli but, sensing an imminent threat to his position, Oli decided to motion for the dissolution of the parliament.

Internal Party Dynamics

Several internal political dynamics have led to the current state of turmoil within the NCP. Dahal has accused Oli of disregarding the power-sharing arrangement agreed upon during the formation of NCP according to which Oli was supposed to hand over either the premiership or the executive chairmanship of the party to Dahal. In September 2020, both the leaders reached an agreement under which Oli would serve the remainder of his term as prime minister and Dahal would act as the executive chair of the party. Yet, Oli failed to demonstrate any intention to relinquish either post, increasing friction within the party. Additionally, Oli made unilateral appointments to several cabinet and government positions, further consolidating his individual authority over the newly formed NCP. He also sidelined the senior leader of the NCP and former Prime Minister Madhav Kumar Nepal, leading Nepal to side with Dahal over Oli. Consequently, Oli chose to dissolve the parliament and seek a fresh mandate rather than face a vote of no-confidence. Importantly, party unity between the Marxist-Leninist CPN (UML) and the Maoist CPN (MC) did not lead to expected ideological unification.

Domestic Politics and Geopolitics

Geopolitical factors and external actors have historically impacted Nepal’s domestic political landscape. Recently, in a bid to cement his authority over the NCP, Oli has attempted to improve ties with India—lately strained due to Nepal’s inclusion of disputed territories in its new political map—resulting in recent high-level visits from both countries. India has also provided Nepal with one million doses of COVID-19 vaccines as part of its vaccine diplomacy efforts in the region. However, while India has previously interfered in Nepal’s domestic politics , it has described the current power struggle as an “ internal matter ” to prevent backlash from Nepali policymakers and to avoid a potential spillover of political unrest.

However, India’s traditionally dominant influence in Nepal has been challenged by China’s ascendancy in recent years. Due to fears of Tibetans potentially using Nepal’s soil to conduct anti-China activities, China considers Nepal important to its national security strategy. Beijing has traditionally maintained a non-interventionist approach to foreign policy; however, this approach is gradually changing as is evident from the Chinese ambassador to Nepal’s proactive efforts to address current crises within the NCP. Nepal’s media speculates that China is in favor of keeping the NCP intact as the ideological affinity between the NCP and the Communist Party of China could help China exert its political and economic influence over Nepal.

Although China is aware of India’s traditionally influential role in Nepal, it is also skeptical of growing U.S. interest in the Himalayan state; especially considering Oli’s push for parliamentary approval of the USD $500 million Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) grant assistance from the United States to finance the construction of electrical transmission lines in Nepal. In contrast, Dahal has opposed the MCC and has described it as part of the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Strategy to contain China. Given Nepal is a signatory to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing might prefer development projects under the BRI framework and could lobby the Nepali government to delay or reject U.S.-led projects.

Implications for Future Governance

After the political changes of 2006 which ended Nepal’s decade-long armed conflict, it was expected that political stability would usher in economic development to the country. Moreover, a strong majority government under Oli raised hopes of achieving modernization. Sadly, ruling party leaders have instead engaged in a bitter power struggle, and government corruption scandals have undermined trust in the administration.

Amidst the current turmoil within the NCP, the main opposition party, Nepali Congress (NC), is hoping that an NCP division will raise its prospects of coming to power in the future. Although the NC has denounced Oli’s move for snap elections as unconstitutional, it has also stated that it will not shy away from elections if the SC decides to dissolve the lower house. Sensing increasing instability, several royalist parties and groups have accused the government of corruption and protested on the streets for the reinstatement of the Hindu state and constitutional monarchy to reinvent and stabilize Nepal’s image and identity.

The last parliamentary elections had provided a mandate of five years for the NCP to govern the country. However, Oli decided to seek a fresh mandate, claiming that the Dahal-Nepal faction obstructed the smooth functioning of the government. Unfortunately, domestic political instability has resurfaced as the result of an internal personality rift within the party. This worsening democratic situation will not benefit either India or China—both want to circumvent potential spillover effects. Even if the SC validates Oli’s move, elections in April are not confirmed. If elections were not held within six months from the date of dissolution, a constitutional crisis could occur. If the Supreme Court overturns Oli’s decision, he could lose his position as both the prime minister and the NCP chair. Regardless of the outcome, Nepali politics is bound to face deepening uncertainty in the days ahead.

This article was originally published in South Asian Voices.

Recent & Related

About Stimson

Transparency.

- 202.223.5956

- 1211 Connecticut Ave NW, 8th Floor, Washington, DC 20036

- Fax: 202.238.9604

- 202.478.3437

- Caiti Goodman

- Communications Dept.

- News & Announcements

Copyright The Henry L. Stimson Center

Privacy Policy

Subscription Options

Research areas trade & technology security & strategy human security & governance climate & natural resources pivotal places.

- Asia & the Indo-Pacific

- Middle East & North Africa

Publications & Project Lists South Asia Voices Publication Highlights Global Governance Innovation Network Updates Mekong Dam Monitor: Weekly Alerts and Advisories Middle East Voices Updates 38 North: News and Analysis on North Korea

- All News & Analysis (Approx Weekly)

- 38 North Today (Frequently)

- Only Breaking News (Occasional)

United States Institute of Peace

Home ▶ Publications

In Nepal, Post-Election Politicking Takes Precedence Over Governance

The latest bout of coalition politics glosses over the country’s troubling drift toward further political instability.

Wednesday, February 8, 2023

/ READ TIME: 9 minutes

By: Deborah Healy ; Sneha Moktan

This past November, Nepalis participated in the second federal and provincial election since its current constitution came into effect in 2015. With 61 percent voter turnout , notably 10 percent lower than the 2017 general elections, the polls featured a strong showing from independent candidates.

Almost half of the incumbent members of parliament — even former premiers, cabinet ministers and party leaders — lost their seats to independents or new political rivals. Amid the political instability that has wracked Nepal over the past several years, including a near constitutional crisis in 2021, the electorate appeared to be holding political leaders accountable at the ballot box for putting politicking above governing.

A Surprising Coalition in Parliament

However, what followed election day has dampened hopes for political reform or renewal. Spurred by public resentment toward the established parties, no single party or existing coalition secured a parliamentary majority. Most expected that the outgoing government, led by the Nepali Congress party, would form a new majority following a brief period of negotiation. However, talks between the Nepali Congress’ outgoing Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba and Pushpa Kamal Dahal, leader of Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist Centre (CPN-MC), broke down when the two failed to agree on who would hold the post of prime minister.

After talks with the Nepali Congress ended, Dahal, who is often known by his nom-de-guerre “Prachanda” from his time leading insurgent forces during Nepal’s decade-long civil war from 1996-2006, swiftly brokered a new alliance with his sometime rival, sometime ally KP Sharma Oli and the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist Leninist (CPN-UML). The two men agreed they would rotate the prime minister’s office between them, with Prachanda serving as prime minister first. With this agreement in hand, Prachanda was sworn in as prime minister on December 26.

Two weeks later, Prachanda was constitutionally obligated to face parliament for a confidence vote. In a surprising reversal, the Nepali Congress and other parties in the opposition announced that they, too, would support the new governing coalition — giving Prachanda a unanimous vote of confidence.

Some analysts suggest this was an attempt by the Nepali Congress to undermine Prachanda’s alliance from the outset by giving Prachanda and the CPN-MC a back-up coalition partner-in-waiting should their pact with the CPN-UML fall through. This would weaken Oli and the CPN-UML’s negotiating power in the new government. The move also dilutes parliamentary checks and balances and calls into question the opposition’s ability to independently scrutinize the actions of a prime minister and government that it helped put in place.

The unanimous vote of confidence creates issues for Prachanda as well, as he must now manage a multi-party coalition representing a spectrum from Marxists to monarchists. Meanwhile, Nepali citizens once again are frustrated and disappointed to see a government formed by parties that have lost a significant number of electoral seats acquire the lion’s share of cabinet positions.

Ongoing Struggle to Implement Federalism

Nepal’s political theme for the last decade has been precarity, and this latest political theater comes amid some worrying trends. Governments rarely run full terms and politicians have played musical chairs with political appointments. Meanwhile, closed-door power-grabs have undermined the electorate’s will. In the seven years since Nepal became a federal state, any initial optimism for the success of federalism has largely waned.

In 2021, only 32 percent of Nepalese said they were satisfied with provincial governments, and chief ministers have complained about the federal government’s reluctance to implement federalism. Provincial assemblies have received limited funding, resources and capacity building support to enable them to be an effective tier of government.

With the outcomes of the 2022 general elections, federalism will continue to face challenges. The governing coalition’s inclusion of the Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP), which served as an umbrella party for the election’s independent candidates, will likely disrupt decisions affecting provincial governments. The RSP are anti-federalism — they did not field any candidates for the provincial government elections, and there were incidents on election day where their supporters visibly rejected Provincial Assembly ballot papers.

With such divergent views within the government, it remains to be seen whether provincial governments will get the support they need to provide effective governance or whether federalism will be able to plant stronger roots in the governance system of Nepal.

Walking a Geopolitical Tightrope

Nepal is wedged between China and India, meaning the country must maintain a delicate balancing act to keep amiable relationships with both powers. While the “left-leaning” parties such as CPN-UML and CPN-MC, who have traditionally been seen as being close to China, seek to strengthen those ties, Nepal has deep historical, cultural and religious ties to India.

However, in recent years, the relationship between Nepal and India has at times been fractious — especially when communist parties have occupied the prime minister's office in Nepal and the right-leaning Modi has occupied the prime minister's office in Delhi.

When Nepal was reeling from devastating earthquakes in 2015, there was an unofficial Indian blockade at the border later that year, which soured India-Nepal relations and saw Oli look to Beijing for support. And in 2019-2020, nationalistic sentiment both in Delhi and Kathmandu — when Oli was prime minister — came to the fore over disputed territories along the border, with both governments re-drawing the demarcations set out in the Sugauli Treaty of 1816.

While accusations of foreign interference in domestic politics have increased over recent years, the domestic political flux has actually made it difficult for foreign powers to negotiate, influence or broker power dynamics in a sustained manner. With fluid alliances and an average of just under one prime minister per year for the past 15 years in Nepal, neither China nor India seems to be able to pull geopolitical strings in the country for a sustained period.

The rollercoaster fate of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) compact further emphasizes this point. The MCC agreement provides $500 million in U.S. grants to support programs to improve electricity and transportation in Nepal. And while the previous Nepali Congress-led government got MCC ratification over the line, it was only after months of protests against the MCC that were fuelled largely by misformation. Now that the MCC is ratified, high-level U.S. officials have been visiting Nepal in quick succession .

While Prachanda’s political victory was welcomed by media outlets in Beijing, given the diverse political ideologies among the coalition, foreign powers near and far will likely struggle to identify true power brokers and influence national politics. On the other hand, this diplomatic uncertainty also makes it harder to build long-term sustained international relations.

Disinformation Continues to Fuel Conflict

In addition to Nepal’s political instability and diplomatic balancing act, social media has been rife with false information on various issues over the past few years, most notably the MCC. Disinformation around the MCC stoked concerns around Nepal’s sovereignty and fuelled several protests in Nepal in 2022.

The elections saw an uptick in this misinformation and disinformation, with doctored images, forged documents and false claims regarding various political leaders, as well as the former U.S. ambassador to Nepal, circulating over social media. This only served to stoke further allegations of U.S. interference in Nepal’s politics. Should this narrative be allowed to continue, it has the potential to fuel further anti-American sentiment in Nepal.

As political parties, politicians and allegedly foreign actors continue to utilize social media to control or twist narratives, senior journalists fear that the worst is yet to come for Nepal in terms of organized disinformation campaigns. In a country where political dissatisfaction has been simmering for decades, and with the government preoccupied with smoothing over the differences in the coalition, such campaigns could trigger political unrest and violence.

The Lack of Women on the Ballot

Nepal’s parliamentary electoral system is split: Voters are asked to choose from a list of candidates for their district’s parliamentary seat as well as for a political party in the country’s proportional representation (PR) system. 165 members of parliament are directly elected to parliament, while the remaining 110 seats are filled based on parties’ vote share in PR list results.

Out of the 4,611 candidates who directly contested seats in the federal parliament, only 225 (9.3 percent) were women. Of this number, only 25 were fielded by the main political parties. The lack of female candidates on the ballot resulted in only nine being directly elected in the country’s first-past-the-post system — only three more than in 2017.

To meet the constitutionally mandated one-third female representation rule, political parties fielded more female candidates under the PR list system. The PR list system was meant to provide electoral opportunities to women and candidates from marginalized and indigenous communities — but members of parliament can only serve one term through the PR list. The intent was to give these underrepresented groups a chance to build experience, after which they could contest a directly elected seat.

Instead, Nepal’s major political parties have repeatedly taken the easy option of nominating new female candidates to the PR list system to ensure they meet the one-third quota rather than nominate experienced women for directly elected seats.

While the parties are fulfilling the constitutional obligations by meeting the quota, there seems to be little long-term investment in developing women leaders. Going forward, the parties need to do more to increase female and marginalized community representation and promote a more representative and inclusive parliament that reflects the spirit of the constitution — not one dominated by the same figures who wish to maintain the status quo.

Where Does Nepal Go from Here?

The past two decades have yielded significant transitions for Nepal: a peaceful resolution to the decade-long Maoist conflict, as well as the end of monarchy and the promulgation of a new constitution that upheld secularism, inclusion and federalism.

But this positive momentum seems to now be staggering, with the same actors from several decades ago largely interested in maintaining a status quo while inflation steadily rises and federalism struggles.

While political forecasting in Nepal continues to be as accurate as reading tea leaves, there continues to be concerns about prolonged political instability — as can be seen by the fragility of the current coalition, which is already in danger of collapsing with the withdrawal of RSP, the third largest coalition partner.

Throw in the upcoming and contentious question of which party gets to nominate the president, and the Nepali people are once again left to witness blatant politicking at the expense of timely attention to economic and governance challenges.

Meanwhile, the Finance Ministry has warned that funding to provincial and local governments could be cut as a result of economic concerns. The entire federal system will be undermined if governments cannot deliver on services and development. Federalism was envisaged as a vehicle for economic development and if it flounders, it could have an impact on Nepal’s graduation to a lower middle-income country in 2026 based on the World Bank’s projections .

Still, the U.S. government sees Nepal as one of two places in Asia with an excellent opportunity for inclusion in the Partnership for Democratic Development. And with high-profile visits from U.S. government officials and scheduled high-profile visits from European governments on the way, there is an opportunity for the international community to urge Nepal’s government to stop politicking and start governing so that Nepal can flourish as a truly democratic nation that respects the rights of the many and not the few.

Deborah Healy is the senior country director for Nepal at the National Democratic Institute.

Sneha Moktan is the program director for Asia-Pacific at the National Democratic Institute.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s).

PUBLICATION TYPE: Analysis

- Culture & Lifestyle

- Madhesh Province

- Lumbini Province

- Bagmati Province

- National Security

- Koshi Province

- Gandaki Province

- Karnali Province

- Sudurpaschim Province

- International Sports

- Brunch with the Post

- Life & Style

- Entertainment

- Investigations

- Climate & Environment

- Science & Technology

- Visual Stories

- Crosswords & Sudoku

- Corrections

- Letters to the Editor

- Today's ePaper

Without Fear or Favour UNWIND IN STYLE

What's News :

- 2008 Rautahat killings

- Air pollution affects Pokhara

- Water problems in Ilam

- Tarai faces extreme heat

- Apex court on release plea

Nepal’s democracy challenges

Seventy years ago, on this day (Falgun 7) Nepal ended 104-year-old Rana rule and ushered in democracy. Nepal’s first steps towards democracy, however, were clumsy. It saw five different governments until 1959 when the country held its first general election. The Nepali Congress, which played a key role in overthrowing the Rana regime, was voted to power with a two-thirds majority. Congress’ BP Koirala was elected prime minister. But Nepal’s democracy dreams were short-lived. Just a year later, in 1960, King Mahendra staged a coup, banned political parties and set up a party-less Panchayat rule, a system the monarch said was “suitable to the Nepali soil”.

It took 30 years before Nepal’s political parties could restore democracy that was snatched away by king Mahendra. In 1990, Nepal proclaimed the dawn of democracy. Maendra’s son Birendra was on the throne. Nepal adopted a multiparty system with the constitutional monarchy and wrote a new constitution in 1990.

But Nepal’s fledgling democracy was assaulted once again. This time by Mahendra’s second son–Gyanendra–in 2005. King Birendra and his family were killed in the 2001 royal massacre.

Nepal needed yet another people’s movement in 2006 which abolished the centuries-old monarchy. A Constituent Assembly in 2015 drew up a new constitution, which was promulgated amid reservations from various sections of society. But five years after the new “people’s” constitution, democracy is once again under threat—this time from KP Sharma Oli, an elected prime minister.

As Nepalis mark Democracy Day, to commemorate the historic day of 1951, the country is yet again facing a democratic crisis.

“We have failed to set up a system, especially after 1990,” said Daman Nath Dhungana, a former House Speaker, who was on the forefront of the 1990 people’s movement, which is also dubbed “first people’s movement”. “It’s unfortunate that even a constitution that was delivered by the Constituent Assembly could not establish a political system.”

Many blame a lack of political culture among the parties for why the country has failed to strengthen democracy.

As in after 1951, the Nepali Congress was voted to power after the restoration of democracy in 1990. Democracy hugely suffered because of the growing intra-party feud in the Congress. Despite leading a majority government, then prime minister Girija Prasad Koirala dissolved the Parliament and called snap polls. Congress senior leader Krishna Prasad Bhattarai had to face a defeat largely due to the internal conflict in the party.

Disenchantment started to grow among the people, politicians were failing to deliver on their promises despite adopting “the world’s best constitution”.

A section of politicians that was vehemently opposed to the parliamentary system was priming itself for a drastic movement, which would later be known as “people's war”—an armed struggle against the state.

As the governments were formed and pulled down in Kathmandu, the Maoists waged the war in 1996, which continued until 2006. By the time it ended, at least 17,000 people had died and thousands were disappeared and maimed.

In 2001, Nepal grabbed international headlines when Birendra, who now in the hindsight many believe was a benevolent monarch, was killed along with his family. His younger brother Gyanendra succeeded.

People’s growing frustrations with politicians and the ongoing armed insurgency prompted Gyanedra, an ambitious individual with less political and more business acumen, into adventurism. When he staged a royal military coup in 2005, borrowing heavily from his father Mahendra’s over decades-old playbook, Nepal’s ever-squabbling parties made a united front. The Maoists who were looking for a safe landing agreed to lend their support.

The 2006 movement thus managed to extract democracy back from Gyanendra’s clutches. Out of sheer people’s power—widespread demonstrations were held across the country—at the call of political parties, the Parliament was resurrected.

The same year, a historic peace deal brought the Maoists to mainstream politics. The parties agreed to Maoists’ Constituent Assembly demand. But the parties that were together to fight the king once again could not maintain their unity for the larger interest of the public and the nation.

After the first Constituent Assembly elections in 2008, the game of musical chairs began again. The assembly was held hostage to politicians’ petty interests.

It took seven years for the assembly to deliver a constitution–once again dubbed “the best in the world”. The constitution guaranteed Nepal as a secular federal republic.

But five years later, the country is running the risk of losing all those gains and democracy is under threats.

“One of the main reasons why democracy in Nepal has suffered one blow after another is we failed to build institutions and systems,” said Ujjwal Prasai, a writer and political commentator who is also a columnist for the Post’s sister paper Kantipur. “We failed to strengthen and build the system and institutions friendly to the people.”

Prasai is currently an active member of the ongoing civilian protest, being organised under the banner Brihat Nagarik Andolan, to protest Prime Minister Oli’s December 20 decision to dissolve the House.

The Supreme Court is testing the constitutionality of Oli’s House dissolution, as his move has been challenged saying he took an unconstitutional step because the current constitution does not allow him to dissolve the House.

“We consider democracy in a formal context because we are holding elections regularly, we have free press, or there is human rights,” said Prasai. “But that is not enough. A democracy should be able to establish a link with the general public and society. We failed to inject democratic values and ethos in society.”

Nepal’s democratic evolution has also been described by many as one step forward two steps back. When Nepal heralded democracy for the first time in 1951, it was crushed by Mahendra and the country suffered for three decades.

When democracy was restored in 1990, politicians instead of nurturing it, made it feeble, thereby offering Gyanendra an opportunity on a platter to seize power.

Today democracy is under threat from the same actors who once championed for the cause.

Oli has argued that he was forced to take the drastic step because he was being driven into a corner by his opponents, especially Pushpa Kamal Dahal.

In what makes the greatest example of politics making strange bedfellows, Oli and Dahal decided to embrace each other in 2018 with a promise to launch “a great communist movement” that would transform Nepal. Dahal led the decade-long Maoist war, and Oli is among those politicians in Nepal who has always been critical of Dahal.

When Oli returned to power in 2018, it appeared that political stability was finally here to stay. But the factional feud in the Nepal Communist Party, especially between Oli and Dahal, resulted in the House dissolution, in what comes as a repeat episode of 1994 when GP Koirala had dissolved the House over infighting in his party.

This time, however, Oli took the step despite the constitution restricting him to do so, displaying his totalitarian streak, say analysts.

“Earlier political parties had conflicts with the monarchy. Now we are fighting against totalitarian tendencies,” said Dhungana. “Political parties have deviated from their primary duty of nation-building to power-grabbing. In earlier days, it was the palace which had an insatiable desire for power, these days political parties have inherited that tendency.”

During the 30 years of Panchayat rule, power was largely exercised by the palace, with some spoils shared among a handful of royal sycophants.

After the restoration of democracy, just as power was transferred to political parties, Nepal started to see the advent of rent-seeking tendencies. By the time the country became a federal republic, patron-client relationship emerged strongly, corruption became the new cottage industry where politicians and cadres started to go to any extent to exploit state resources.

Analysts say Nepali politicians totally forgot the age-old maxim of the government of the people, by the people and for the people.

“Democracy should serve the aspirations of millions of people and it’s definitely a tall order. That’s why democracy is chaotic also,” said Prasai, the writer. “But by building robust institutions and systems, governments can address people’s grievances and needs. That’s how democracy functions.”

While Nepali politicians are blamed for democratic backsliding, there is a section that strongly believes that until Nepal defeats foreign intervention, it cannot attain stability and cannot make strides in socio-economic sectors.

“The role of foreign hands in every big change in Nepal is no secret–in 1950 or 1990 or 2006,” said CP Mainali, a senior communist leader. “We failed to find the leadership at home that could fight foreign intervention. This is the sole reason we have failed to sustain the achievements in the last 70 years and have not been able to bring changes in people’s lives.”

According to Mainali, once Oli’s mentor, Nepal’s democratic movements have been laudable but a lack of failure to find a true leader has meant people’s aspirations of democracy and development continue to remain unfulfilled.

“We rather allowed more space to foreign hands to expand their clout instead of trying to become strong and independent in our decision-making,” said Mainali. “Our leaders totally failed to comprehend the fact their fight for democracy meant creating an environment where people are served. It’s instead the opposite. It looks like leaders fought for democracy for their benefit.”

Most of today’s leaders in Nepali politics have quite a record of their own under their belts, most of them have served jail terms fighting against the Panchayat regime and then the monarchy. There is no denying that they exhibited their unwavering commitment to democratic values, equitable society and rule of law–and above all, for the people. But the moment they get to power, they tend to forget all these, according to analysts.

“From 1959 to 2006, we were in a direct conflict with the monarchy that always stood against the fundamentals of democracy,” said Prof Krishna Khanal, who teaches political science at Tribhuvan University. “We may have failed to nurture democracy well, but a reversal is unlikely.”

According to Khanal, in Nepal, people's power has always prevailed.

“A democracy also means accountability. The only solution is our managers [politicians] must learn how to manage the system,” Khanal told the Post. “Democracy often faces challenges and we can say it is in peril in Nepal today. But it stands an equal chance of becoming vibrant and functional… just that leaders need to be made accountable.”

Some analysts find an uncanny repeat of a cycle, as people once again are on the streets to fight for democracy, just as the country is celebrating its Democracy Day to mark the dawn of democracy in Nepal.

Prasai, the writer, said that unless political actors are constantly kept in check and made accountable to those who elect them, democracy will continue to face challenges.

“Democracy should be realised by the people, and it’s the political actors who can make this happen,” Prasai told the Post. “In our context, it looks like democracy will face some challenges like it is facing today for some decades more.”

Anil Giri Anil Giri is a reporter covering diplomacy, international relations and national politics for The Kathmandu Post. Giri has been working as a journalist for a decade-and-a-half, contributing to numerous national and international media outlets.

Related News

New provincial cabinets slow to take full shape

Top court intervenes in Gaur massacre case

No immediate chance of Congress, UML partnering for poll reforms, leaders hint

Oli, Dahal against communist reunification in haste

After Gandaki, government formation in Sudurpaschim challenged in court

UML chief’s political paper rules out communist unity as immediate need

Most read from politics.

Oli dismisses left unity, stresses national unity

- Publications

Nepal: A political economy analysis

Download this publication

This report is an integrated political economy analysis of Nepal. The main finding is that economic growth and poverty reduction have been steady in Nepal since the mid-1980s independently of a number of political upheavals, including ten years of civil war. The growth has been driven by remittances and an upward pressure on wages in local labor markets. As a result, poverty has declined and social indicators have improved. Despite the availability of private capital and increases in wages for the poor, there is still a massive need for public investments in infrastructure, agriculture, health, and education. In the political domain the recent local elections will reintroduce local democracy after 20 years. Elected local politicians are expected to boost local development efforts. The leading political forces in Nepal are the political parties. There are close links between politicians and business leaders, the political parties control the trade-unions, have links to civil society organizations, and the parties select high-level government officials. The civil war and the post-war ethnic uprising led to demands for an ethnic based federal republic. A compromise federal map was decided in 2015, with provincial elections scheduled for the fall of 2017. There are concerns that the ethnic agenda may escalate ethnic conflicts, and it will be essential for all parties to work for participation of all social groups within the recently established local units, as well as in the economy at large.

Magnus Hatlebakk

- [email protected]

- +47 47938121

Vern av eller mot flyktningar?

Arne Strand

Helhetlig innsats i krise og konflikt. Hva mer kan Norge gjøre?

Ottar Mæstad, Nikolai Hegertun, Hans Inge Corneliussen

Helhetlig innsats i krise og konflikt. Hva er utfordringene?

Nikolai Hegertun, Ottar Mæstad

Examining poverty and food insecurity in the context of long-term social-ecological changes in Kabul, Afghanistan

Yograj Gautam, Anwesha Dutta, Patrick Jantz, Alark Saxena, Antonio De Lauri

Select a language

Accord ISSUE 26 March 2017

Downloads: 1 available

Available in

- Introduction: Two steps forward, one step back

- Nepal's war and political transition: a brief history

- Section 1: Peace process

- Stability or social justice?

- Role of the citizen in Nepal's transition: interview with Devendra Raj Panday

- Preparing for another transition?: interview with Daman Nath Dhungana

- Architecture of peace in Nepal

- International support for peace and transition in Nepal

- Transitional justice in Nepal

- Transformation of the Maoists

- Army and security forces after 2006

- People’s Liberation Army post-2006: integration, rehabilitation or retirement?

- Post-war Nepal - view from the PLA: interview with Suk Bahadur Roka

- PLA women's experiences of war and peace: interview with Lila Sharma

- Looking back at the CPA: an inventory of implementation

- Section 2: Political process

- Legislating inclusion: Post-war constitution making in Nepal

- Comparing the 2007 and 2015 constitutions

- Political parties, old and new

- Electoral systems and political representation in post-war Nepal

- Federal discourse

- Mapping federalism in Nepal

- Decline and fall of the monarchy

- Local governance and inclusive peace in Nepal

- Section 3: Inclusion

- Social movements and inclusive peace in Nepal

- Post-war armed groups in Nepal

- Secularism and statebuilding in Nepal

- Justice and human rights: interview with Mohna Ansari

- Gender first: rebranding inclusion in Nepal

- Inclusive state and Nepal’s peace process

- Inclusive development: interview with Shankar Sharma

- Backlash against inclusion

- Mass exodus: migration and peaceful change in post-war Nepal

- Section 4: Conclusion

- Uncertain aftermath: political impacts of the 2015 earthquakes in Nepal

- Conclusion More forward than back?: next steps for peace in Nepal

- Chronology of major political events in contemporary Nepal

Issue editors Deepak Thapa and Alexander Ramsbotham review the decade-long transition since the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Accord and consider whether Nepal is indeed post-conflict, or if the last ten years of fractious politics and episodic violence represent simply another phase of struggle. Regardless, they argue that the war and the peace process have brought significant change to Nepal’s social and political landscape, even if social justice remains a way off for many Nepalis outside the prevailing elite.

Peace by chance?

The manner in which the Maoist insurgency ended – with the removal of the monarchy – was far from inevitable. Indeed, chance was a recurrent motif in political developments in Nepal stretching from the early 1990s all the way to the 2006 CPA, facilitated by the capriciousness of the political parties and power struggles among political leaders. Nearly all the principal actors involved in the end of the war did little to address the insurgency in its early stages, and their paramount role in winding it down was not so much a deliberate strategy as following the old maxim that ‘the enemy of my enemy is my friend’.

Internal tussles in the Nepali Congress (NC) in particular accompanied significant developments in the Maoist conflict and how it ended. Factionalism began after the 1991 election, in which the NC won a majority. The three and a half years of the Girija Prasad Koirala-led government was the longest any had lasted in the post- 1990 period, but the latter stages were marred by bitter infighting. After losing a parliamentary vote in mid-1994, rather than step down, Koirala dissolved parliament in order to rein in his party’s dissidents. Significantly, this also spelt an end to parliamentary politics for the third largest force in the House of Representatives – the United People’s Front, the political wing of the semi-underground far-left party, a faction of which evolved into the insurgent Communist Party of Nepal–Maoist (CPN-M).

Koirala’s call for mid-term polls turned out to be a miscalculation. The NC was beaten by the CPN–Unified Marxist-Leninist (UML), but with only a plurality of parliamentary seats, the minority UML government lasted just nine months. Its removal set in motion a process of extremely unstable politics that saw a number of coalition governments, a situation that suited the Maoists and their budding insurgency very well.

The NC came back to power with a majority in 1999 and Koirala began his third term as prime minister in 2000. Factionalism was by now more or less institutionalised in the party and Sher Bahadur Deuba emerged as the leader of the anti-Koirala faction of the NC. Within a year of Koirala’s return to power, the Maoists clearly began favouring Deuba as someone with whom they could do business. Deuba had been prime minister when the insurgency began, but he had also been appointed to a committee to seek ways to bring a peaceful solution to the Maoist conflict.

The Deuba-Maoist detente played out in the 2001 ceasefire. However, when the Maoists quite suddenly resumed fighting, Deuba unleashed the full might of the state against the rebels, deploying the army for the first time. Now it was Koirala who moved closer to the Maoists, pressing for an end to the state of emergency in place at the time. The Koirala-Deuba feud ultimately resulted in Deuba dissolving parliament, just as Koirala had done nine years earlier. But, this time Deuba was expelled from the party, and he responded by splitting the NC itself.

In the meantime, the monarchy had become much more prominent in politics. King Gyanendra pounced on the opening provided by the disarray in the NC and the absence of parliament, but over the first years of his reign he managed to thoroughly alienate the political parties. The Maoists had hoped to exploit this gulf by striking a deal with Gyanendra, but the February 2005 royal takeover ensured an end to all overtures they had been making towards the king.

The king’s manoeuvres succeeded in bringing the parties and the Maoists to the realisation that their principal adversary was the palace. New Delhi also felt let down by the king studiously ignoring the long-held Indian position on what it viewed to be the twin pillars of political stability in Nepal: multiparty democracy and constitutional monarchy. The king’s snub came at a time when India had thrown itself firmly into the fight against the Maoists, such as by providing much-needed materiel to the Nepali Army. And although India had not realised the depth of popular anger against the palace, it had no choice but to go along with events that unfolded in the wake of the second People’s Movement and the complete sidelining of the monarchy.

Thus, political one-upmanship created the conditions for the Maoist movement to take off. But, its continuation over a decade also laid the foundations for the end of the conflict and the entry of the Maoists into mainstream politics.

Peace through inclusion

The government and political parties sought to undercut the Maoists’ progressive agenda with the introduction of a number of competing measures for reform. Many of these were what various social movements had long been agitating for. Steps such as the formation of the Committee for the Neglected, Oppressed and Dalit Class and the National Foundation for Development of Indigenous Nationalities were taken partly in response to pressure from social activists. But the insurgency brought home the depth of dissatisfaction with the status quo.

The Maoist movement pushed successive governments into adopting ever more inclusive provisions. Hence, while the Deuba government in 2001 had responded with a National Dalit Commission and the National Women’s Commission, among others, within a few years the idea of affirmative action policies had more or less become the accepted norm. The Maoists, too, were taken to task over the issue of inclusion, for despite their demands for gender equality, not a single woman was involved in their five- member negotiating team for the 2003 ceasefire.

By the time of the 2006 People’s Movement, it had been generally recognised that the state would have to become much more inclusive. The notion of state restructuring outlined in the CPA was clearly meant to accomplish that, but the momentum granted by the People’s Movement extended much further. When the First Madhes Movement erupted in early 2007, the public discourse was overwhelmingly in favour of Madhesis with a general excoriation of the state for the long subjugation they had experienced, and calls for addressing the sources of their dissatisfaction. Likewise, when the government later introduced reservations in elections and also in public sector jobs, the move met with hardly any opposition.

Such government policies have been instrumental in sustaining peace in the long term. The form of federalism may have been contested but despite misgivings expressed by more than a few influential people, there have been no considered attempts so far to roll back the achievements made towards a more inclusive state, whether through job reservations or electoral quotas – although the recent reduction of the number of seats to be elected through proportional reservations in the federal and provincial legislatures is considered by many to be exclusionary, as are steps such as the narrow definition provided for secularism, among others.

The integration of the Maoists into competitive politics may not have been achieved so easily had it not been for these measures. Their agenda was in part achieved even if their larger goal of a complete transformation of the socio- political structure could never be met, since the conflict was ended through a negotiated settlement with give and take from both sides. The core of the Maoist fighters who sustained the war against the state have been the most disappointed with the outcome. But, the training that had formed an intrinsic part of the party organisation, in which the military wing remained subservient to the political side, ensured compliance to all party decisions.

Peace and external support

While the push for greater inclusion came with the 1990 political change and was carried forward by the social movements and the Maoist insurgency, the government and its donor partners later became equally invested in supporting such an outcome. The government’s periodic plans in the 1990s had outlined ambitions to reach out to population groups that were increasingly being recognised as excluded from the development mainstream. But as the Maoist insurgency grew stronger and more widespread, there was a rising call from the donor community that it would also have to be countered by addressing the root causes of the conflict, which by definition meant opening up the state to greater levels of inclusion.

External actors have also had a more direct role in the unfolding of the peace process. Most consequential was the involvement of the United Nations, beginning with the Maoists’ initial response to the UN’s offer in 2002 to provide help in reaching a negotiated settlement to the conflict. For a group that had managed to isolate itself through its pronouncements (calling India ‘hegemonic’ and the United States ‘imperialist’) and its actions (killing Nepali staffers employed by the US embassy and targeting programmes funded by western countries, particularly by the US), an international guarantor was required for any agreement reached, not to mention for the Maoists’ personal safety.

But UN involvement would have been impossible without the acquiescence of India. The two countries routinely vilified by the Maoists, India and the US, had both labelled the CPN-M a terrorist organisation. India still clung to its ‘twin-pillar’ policy while the US had tried without success to effect a rapprochement between the palace and the mainstream parties. King Gyanendra’s obduracy slowly pushed India towards acceptance of UN involvement in bringing the conflict to a close. That the UN was even mentioned in the 12-Point Understanding signed in New Delhi in November 2005 is instructive of this change. Even earlier, India had gone along with setting up the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Kathmandu. Established in May 2005, soon after the royal coup, its presence in the streets has been credited with the comparatively restrained response by the security forces during the April 2006 People’s Movement.

The UN Mission in Nepal (UNMIN) was deployed in January 2007 with the mandate to monitor arms, armies and the ceasefire, and to oversee the election of the Constituent Assembly. This limited mandate was primarily to allay Indian concerns. But contradictory interpretations of UNMIN’s role proved highly controversial over the four years of its tenure – on the one hand the failure to fully appreciate the specific tasks UNMIN had been given, and on the other the perception that the UN was somehow all-powerful. Thus, a meeting by the head of UNMIN with Madhesi leaders was criticised for overreach. At other times, UNMIN was accused of doing too little to rein in the Maoists. And the Maoists spoke out against UNMIN’s intrusive scrutiny of their activities. To its credit, UNMIN succeeded in seeing through the election to the 2008 Constituent Assembly, and even though the Maoist combatants were still in the cantonments by the time its mission ended, it preserved the peace between the two sides and laid the ground for the eventual disbandment of the Maoist army.

Over time there has been some concern about the direction the country has taken. Conflating the related but separate concepts of federalism and inclusion, influential sections in the government, the political parties and the media have pressured donors to ease off on the social inclusion agenda. Even India has not been able to make much headway in its call for a more inclusive polity. New Delhi’s position today is a far cry from the post- 2006 period, when it was viewed almost as an arbiter of Nepal’s fate, having stood with the political parties and the Maoists against the monarchy and enforcing an end to the second People’s Movement by leaning hard on the king. But, India continued with its political games, such as engineering the formation of a political party, the Tarai Madhes Loktantrik Party, to counter the Madhesi Janadhikar Forum Nepal, which was viewed as being too independent with its own power base. It coddled the NC and the UML, to act as a counterpoise to the Maoists and their radical agenda, only to realise later that the NC-UML combination is in general a conservative force, and that this conservatism would affect how they would deal with the grievances of Madhesis as well.

The fracas over the 2015 constitution, including the blockade at the border with India, and the tepid concession to Madhesi demands granted by the UML government with the first amendment to the constitution, has laid bare the limits of India’s power. There is no sign at the time of writing that the second amendment, introduced in November 2016 to further assuage Madhesis, is going to get anywhere. But although India has lost a lot of leverage recently, geopolitical reality dictates that New Delhi will always remain a major player in Nepal’s politics. And, the terms and conditions of that engagement that will be decided by political developments on the Madhes issue.

Whether one sees Nepal as post-conflict or in a new period of intense transition, it is clear that the war and the peace process have brought significant change. Communities on the periphery of Nepali politics and society – whether marginalised by culture, class, geography, gender or caste and ethnicity, or some configuration of these – have been at the centre of the struggle. But social justice is still a long way off for many Nepalis outside the prevailing elite. With the new constitution in place, which has been so symbolic as the culmination of Nepal’s transition ‘from war to peace’, advocates for inclusion may need to find new forums in which to negotiate change.

All authors and contributors

- Dr Alexander Ramsbotham

- Deepak Thapa

- Bishnu Sapkota

- Aditya Adhikari

- Mandira Sharma

- Jhalak Subedi

- Sudheer Sharma

- Chiranjibi Bhandari

- Suk Bahadur Roka ‘Sarad’

- Lila Sharma ‘Asmita’

- Krishna Hachhethu

- Dipendra Jha

- Sujeet Karn

- Kåre Vollan

- Krishna Khanal

- Gagan Thapa

- Bandita Sijapati

- Mukta S. Tamang

- Chiara Letizia

- Mohna Ansari

- Lynn Bennett

- Yam Bahadur Kisan

- Shankar Sharma

- Shradha Ghale

- Amrita Limbu

- Austin Lord

- Sneha Moktan

Accord Issue Issue 26

Pradip Timsina

Social, economic and political context in nepal, political context.

A large section of the population in Nepal cannot access political participation and representation to public affairs due to economic and social conditions, social stigma and lack of access to information, among other reasons. Nepal retains its centuries-old caste system. Dalits , the most discriminated people under this system, suffer from restriction on the use public amenities, deprivation of economic opportunities, and general neglect by the state and society.

In 1996, the Nepal’s Maoist Communist party launched a violent campaign to replace the royal parliamentary system with a people’s socialist republic. The ensuing ten years civil war had several origins, including overall poverty and the lack of economic development, long periods of landlessness and deprivation of lower castes and lower-status ethnic groups generating anger at the country’s elites, as well as dissatisfaction against the government’s targeting of Maoist activists. The conflict resulted in the death of over 12,000 people, the displacement of more than 100,000 people, and the devastation of public infrastructures.

The conflict officially ended in 2006, with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Accord (CPA). In 2007, the Interim Constitution of Nepal was adopted, replacing the 1990 Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal. It created an interim Legislature-Parliament, a transitional government reflecting the goals of the 2006 People’s Movement – the mandate of which was for peace, change, stability, establishment of the competitive multiparty democratic system of governance, rule of law, promotion and protection of human rights, full press freedom and independence of judiciary based on democratic values and norms.

In 2008, a Constituent Assembly (CA) was established. That same year, the CA resolved to end the 239 year-old monarchy and declare Nepal a federal democratic republic. The CA is responsible for electing the President (the head of state) and the Prime Minister (head of government). In 2010, almost a third of the members of the CA were women, and a record number of Dalits and other marginalised groups were elected.

As part of the process of drafting Nepal’s new constitution, regional consortiums of NGOs have held ‘democracy dialogues,’ including over 400,000 people, to help ensure that the constitution represents Nepal’s diverse population, as well as to increase citizens’ confidence in, and understanding of the process. New constitutional provisions include new economic, social and cultural rights; new voting systems; and affirmative action for marginalised groups. It is expected that women will be assured 33% representation in the new Parliament. The new constitution has not been finalised, largely due to disagreements on whether to determine Nepal state boundaries on the basis of ethnicity. In May 2012, Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai dissolved the Constituent Assembly after it failed to finish the constitution in its last time extension, leaving the country in a legal vacuum. Election of the new Constituent Assembly was due in spring 2013.

Social and economic context

The international community has been heavily involved in supporting Nepal’s democratic transition and making progress toward the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. UNDP’s Nepal Human Development Report 2009 found that the underlying causes of conflict have not been resolved (such as poverty and discrimination on the basis of caste and ethnicity), nor have most of the consequences of the conflict (for example, 50,000-70,000 people were thought to still be displaced). Although the UN estimates that poverty in Nepal dropped from 42% in 1996 to approximately 25% in 2009, that trend was not sustained; recent estimates indicate that a quarter of the population are still below the poverty line. Nepal’s governance and development challenges have been exacerbated by frequent changes in government and the absence of elected local bodies since 2002.

Policy and legal framework

Nepal has acceded to all major human rights treaties, and the Nepal Treaty Act of 1990 stipulated that provisions in international treaties to which Nepal is a party will supersede Nepalese law where there is divergence. In 2003, the government, in cooperation with civil society, has drawn up Nepal’s first National Human Rights Action Plan (NHRAP). The first of its kind in the region, the Action Plan is intended to give equal attention to civil, political, cultural, economic and social rights.

The Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare has the role of coordinating gender mainstreaming efforts in Nepal. Key legislative measures aimed at the promotion of gender equality and the elimination of discrimination against women in Nepal include: the five-year strategic plan of the National Women’s Commission (2009-2014); the Domestic Violence (Crime and Punishment) Act, 2009; the Human Trafficking and Transportation (Control) Act, 2007; the National Women’s Commission Act, 2007; and the Gender Equality Act, 2006. The National Women Commission (NWC) was established by the Government of Nepal through an executive decision in 2002 and a separate Act was promulgated in 2007. It has a legal mandate to monitor and investigate cases of violence against women, providing legal aid, monitor the state obligations to UN reporting under CEDAW, coordinate with government and other agencies for mainstreaming gender policy in national development and recommending and monitoring for the reforms by making research.

Civil society

Nepal’s civil society played a crucial role in the 2006 People’s Movement, but has become fractured in recent years. Social unity is disintegrating due to identity politics based on ethnicity and regionalism.

The NGO Federation of Nepal (NFN) emerged as an umbrella organisation of NGOs in 1990. In addition to defending NGOs’ autonomy, the NFN advocates human rights, social justice and pro-poor development. Today, it has evolved as a leading civil society organisation in Nepal with over 5,370 affiliated NGOs across the country.

In 2003, the Human Rights Treaty Monitoring Coordination Center (HRTMCC) was established. The HRTMCC is a coalition of human rights organisations established to monitor the implementation of the international human rights treaties the country has ratified.

In 2013, a group of former bureaucrats, professionals and individuals from various sectors in Nepal formed an independent civil society organisation, the Citizens Assembly. Its objective is to exert pressure on state authorities, political leadership and policymakers to work for the interests of the country and the public.

Asian Development Bank “Nepal Overview”

Asian Development Bank (2013) “Nepal Fact Sheet”

Government of Nepal (2010) “Second, third and fourth periodic reports of the government of Nepal on measures taken to give effect to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights” (ICCPR)

Government of Nepal (2011)“The Combined 4th and 5th Periodic Report of the Government of the Republic of Nepal on Implementation of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)”

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (2013) “International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Shadow Report”, Second, third & fourth periodic reports of the government of Nepal on measures taken to give effect to ICCPR

Menon, N., Rodgers, Y. (August 2011) “War and women’s work: evidence from the conflict in Nepal”, The World Bank

National Women’s Commission of Nepal (2011) “Nepal’s Implementation Status of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)”

NGO Federation of Nepal 3-Year Strategic Plan (October 2012-September 2015)

UNDP “In Nepal new voices speak through people’s constitution” (accessed 09 July 2013)

UNDP (2012) “Nepal: Training promotes peace and gets political parties talking”

UNDP (2009) “Nepal Human Development Report 2009”

The World Bank “Nepal country data”

Source: http://interactions.eldis.org/unpaid-care-work/country-profiles/nepal/social-economic-and-political-context-nepal

- International

- Today’s Paper

- Premium Stories

- Express Shorts

- Health & Wellness

- Board Exam Results

Explained: What is at stake in Nepal’s political crisis?

Nepal's political crisis: the lower house of parliament has been dissolved at the recommendation of prime minister oli, who is fighting a losing battle in his party. a look at the questions it raises over the constitution and left unity.

On Sunday, Nepal Prime Minister K P Oli recommended dissolution of the House of Representatives, the lower of Parliament, a move promptly approved by President Bidhya Devi Bhandari.

This effectively ended the unity forced among the left forces that had led to the creation of the single, grand Nepal Communist Party three years ago. It plunged national politics into turmoil and the five-year-old Constitution into uncertainty, and raised questions about the haste with which the President approved Oli’s recommendation.

Oli took the step when he realised that a factional feud within the party had reached the point of no return and he faced possible expulsion both as party chief and as Prime Minister. Since then, a dozen petitions have been filed in the Supreme Court challenging the dissolution with two years left of the present House’s tenure. Each faction has also approached the Election Commission claiming it is the real party.

Oli’s battles

Oli is fighting a losing battle in the party. He has declared that the next election will be held on April 30 and May 10 next year with him leading a caretaker government, but his fate will be decided by agitating crowds and the Supreme Court. There’s also a movement for restoration of Nepal as a Hindu kingdom.

His move has created bitterness between the breakaway communist group he leads and other parties. On Monday evening, Oli got his followers to padlock the party office, effectively bringing it under his control, but going by the numbers in the dissolved Parliament, the Central Secretariat, the Standing Committee and the Central Committee, Oli is in a minority. But with Parliament dissolved and with a President seen as favourable to him, Oli will have the power to rule without being accountable to none.

The dissolution came hours before a Standing Committee meeting that was expected to order a probe into corruption charges levelled against him by party co-chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal Prachanda.

The unification & its end

Prachanda led the Maoist insurgency for a decade (1996-2006) before joining mainstream politics. Oli was a fierce critic of the politics of violence that caused more than 17,000 deaths. But Oli approached the Maoists in 2017 for a merger between their parties, pre-empting the possibility of an alliance between the Maoists and the Nepali Congress that may have come in the way of Oli’s prime ministerial ambitions.

Oli was leading the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist Leninist, and Prachanda represented the Nepal Communist Party (Maoist). Following the merger, the two leaders agreed that they would lead the government by turn, a promise that Oli did not honour at the end of his two-and-a-half years, thus sowing the seeds of separation. Now, as a split appears inevitable, Oli is hoping to continue in power with those following him.

📣 JOIN NOW 📣: The Express Explained Telegram Channel

Questions over Constitution

What has happened has left a question mark over the Constitution of 2015, and its key features like federalism, secularism and republic. There are already popular protests on the streets.

The split in a party with a two-thirds majority has raised concerns that it may lead to a systemic collapse. “We will go for a decisive nationwide movement to have this Constitution dumped,” said Balakrishna Neupane, convener of an ongoing citizens’ movement.

Constitution & dissolution

Dissolution of the House is not new in Nepal, but this is the first such instance after the new Constitution of 2015 that places safeguards against dissolution. “The new constitution does not envisage such a step without exploring formation of an alternative government,” said Dr Bhimarjun Acharya, a leading constitutional lawyer.

The 1991 Constitution, scrapped in 2006, had provisions for dissolution of Parliament at the Prime Minister’s prerogative. During the time it was in force, Parliament was dissolved thrice. The first Parliament elected in 1991 was dissolved on the recommendation of Prime Minister G P Koirala after he failed to have a vote on thanks motion by the King passed in the House. The Supreme Court upheld that dissolution.

But in 1995, the Supreme Court rejected the dissolution by Prime Minister Manmohan Adhikary after a no-trust motion had been tabled but before the loss of majority was proved. The court held that the executive did not have the right to snatch an issue under consideration of the legislature.

The third time, Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba dissolved Parliament in 2002 and the Supreme Court upheld it. King Gyanendra revived Parliament in April 2006.

- The story of indelible ink, a lasting symbol of Indian elections, and who makes it

- What is the Army Tactical Missile System, which the US has sent to Ukraine?

- Why a US court overturned Harvey Weinstein’s 2020 rape conviction

Opposition stakes

The opposition Nepali Congress and the Madhes-based Janata Samajbadi Party have reasons to hope than an early poll will earn them a bigger space in Parliament. But it fears that the likely street protest and violence, besides the onset of rain in late April and early May, could be used as an excuse to further defer the election.

“I doubt elections will be held on the prescribed dates,” said Shekhar Koirala, member of the Nepali Congress central committee. The Nepali Congress or the Janata Samajbadi Party have, however, not been very proactive in Parliament in countering the government.

The Nepal Army has made it clear that it will remain neutral in the ongoing political developments. This implies that if Oli tries to rule with the help of security forces to maintain law and order and contain protests, it is uncertain how far the Army will play along.

The China factor

China has been a big factor in Nepal’s internal politics since 2006. It is seen as having lobbied, visible or secret, to prevent the split. China has also invested in crucial sectors like trade and Investment, energy, tourism and post-earthquake reconstruction, and is Nepal’s biggest FDI contributor. It has increased its presence in Nepal because of a perception that India played a crucial role in the 2006 political change.

What phase 1 voter turnout says about BJP’s chances in Subscriber Only

UPSC Essentials | Daily quiz: environment, geography, & more Sign In to read

Case before SC: Can govt redistribute privately owned property? Subscriber Only

Road ahead for Tesla: Why EV sector is struggling Subscriber Only

Engineering in local language sees uptick in students in UP, Subscriber Only

How Bengaluru’s lakes disappeared Subscriber Only

After wars, deaths, political turmoil, the era of Indira Gandhi Subscriber Only

Faced with coastal Karnataka ‘saffron wall’, Cong counts on welfare Subscriber Only

India’s trade with Israel & Iran, and impact of regional Subscriber Only

- Explained Global

- Express Explained

- K P Sharma Oli

Acting is about convincing others, and the best actors can become anyone. Legendary actors like Mammootty, Kamal Haasan, Shah Rukh Khan have played versions of themselves, and now Nivin Pauly is attempting something similar in Varshangalkku Shesham. This takes courage and skill, but it can create a powerful and memorable performance.

More Explained

Best of Express

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01 Study says it’s likely a warmer world made deadly Dubai downpours heavier

- 02 Richa Chadha calls her character in Heeramandi ‘female Devdas’, says she is scared to get ‘stereotyped as a drunkard woman’

- 03 SRH vs RCB Emotional Rollercoaster: A glimpse of how Pat Cummins bowls perfect T20 over and Patidar completes what Kohli started

- 04 BTS’ RM set to release solo album Right Place, Wrong Person

- 05 UAE announces $544.6 million to repair homes: How the flood-hit country is inching back to normalcy

- Elections 2024

- Political Pulse

- Entertainment

- Movie Review

- Newsletters

- Gold Rate Today

- Silver Rate Today

- Petrol Rate Today

- Diesel Rate Today

- Web Stories

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Qatari emir in Nepal, expected to tackle migrant conditions and Nepali student held hostage by Hamas

Nepal’s President Ram Chandra Poudel checks his watch as he and Minister of Foreign Affairs Narayan Kaji Shrestha, wait for Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al arrival at Tribhuvan international airport in Kathmandu, Nepal, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. The emir arrived on a two-days visit to the Himalayan nation. (AP Photo/Niranjan Shreshta)

Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al arrives at Tribhuvan international airport in Kathmandu, Nepal, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. The emir is on a two-days visit to the Himalayan nation. (AP Photo/Niranjan Shreshta)

Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, is received by Nepal President Ram Chandra Poudel, left as he arrives at the airport in Kathmandu, Nepal, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. The emir is on a two-days visit to the Himalayan nation. (AP Photo/Niranjan Shreshta)

Nepal’s president Ram Chandra Poudel, right, introduces Nepal’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Narayan Kaji Shrestha to Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al arrival at Tribhuvan international airport in Kathmandu, Nepal, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. The emir is on a two-days visit to the Himalayan nation. (AP Photo/Niranjan Shreshta)

Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, is received by Nepal President Ram Chandra Poudel, right as he arrives at the airport in Kathmandu, Nepal, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. The emir is on a two-days visit to the Himalayan nation. (AP Photo/Niranjan Shreshta)

Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, center left, stands with Nepal’s President Ram Chandra Poudel, center right as he receives guard of honor at his arrival at the airport in Kathmandu, Nepal, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. The emir is on a two-days visit to the Himalayan nation. (AP Photo/Niranjan Shreshta)

Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, center right, walks with Nepal’s President Ram Chandra Poudel, center right as he receives guard of honor at his arrival at the airport in Kathmandu, Nepal, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. The emir is on a two-days visit to the Himalayan nation. (AP Photo/Niranjan Shreshta)

Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, greets one of the children who received him upon his arrival at the airport in Kathmandu, Nepal, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. The emir is on a two-days visit to the Himalayan nation. (AP Photo/Niranjan Shreshta)

Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, center behind, stands with Nepal’s President Ram Chandra Poudel, center front as he receives guard of honor at his arrival at the airport in Kathmandu, Nepal, Tuesday, April 23, 2024. The emir is on a two-days visit to the Himalayan nation. (AP Photo/Niranjan Shreshta)

- Copy Link copied

KATHMANDU, Nepal (AP) — The emir of Qatar landed in Nepal Tuesday on his first-ever visit to the South Asian country, after visiting Bangladesh and the Philippines, where improving migrant workers’ conditions in the Gulf state and a Nepali student still held hostage by Hamas are expected to be on the agenda.

Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani is set to meet Nepali dignitaries, including President Ram Chandra Poudyal and Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal during his two-day visit.

Qatar hosts an estimated 400,000 Nepali workers, most in construction and manual labor. Concerns about working in extreme heat — that could reach over 40 C (104 F) — inadequate living facilities and abuse have risen in recent years.

New York-based Human Rights Watch called on Qatar, Nepal and Bangladesh in a statement Sunday to prioritize labor protection for migrant workers during the emir’s visit.

“It is important ... to go beyond exchanging diplomatic pleasantries over their longstanding labor ties and seize this moment to publicly commit to concrete, enforceable protections that address the serious abuses that migrant workers in Qatar continue to face,” the statement quoted Michael Page, the agency’s deputy Middle East and North Africa director, as saying.

The statement added that while Qatar-based jobs have allowed migrant workers “to send remittances back home to their families,” many experience abuse, including “wage theft, contract violations, and chronic illness linked to unsafe working conditions.”

Nepali officials are also likely to seek Al Thani’s help in freeing a local , Bipin Joshi, who is held hostage by the Palestinian militant group Hamas. Joshi was among 17 Nepali students studying agriculture in Alumim kibbutz, near the Gaza Strip, when Hamas attacked Southern Israel on Oct.7. Ten of the students were killed, six injured and Joshi was held captive.

Though there has been no information on his condition or whereabouts, Nepali officials said they believed he was still alive.

Hamas’ sudden attack in October killed 1,200 people and some 250 others hostage were taken hostage. This has sparked a war that has so far killed more than 34,000 Palestinians in Gaza, at least two-thirds of them women and children, according to the local health ministry.

Qatar has been a key intermediary throughout the war in Gaza. It, along with the U.S. and Egypt, was instrumental in helping negotiate a brief halt to the fighting in November that led to the release of dozens of hostages.

A spokesman for Qatar’s Foreign Ministry said Tuesday his country was undergoing an assessment of its role in mediating talks between Israel and Hamas over a cease-fire in the Gaza Strip. He also said discussions were ongoing about Hamas’ presence in Qatar where the militant group has had a political office in the capital, Doha, for years.

France and Qatar mediated a deal in January for the shipment of medicine for the dozens of hostages held captive by Hamas.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Nepal's domestic politics have been undergoing a turbulent and significant shift. On December 20, 2020, at the recommendation of Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, President Bidya Devi Bhandari dissolved the House of Representatives, calling for snap elections in April and May 2021. Oli's move was a result of a serious internal rift within the ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP) that threatened ...