- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- How does the printing press work?

- Why is the printing press important?

- When was the printing press invented?

- Who controls the Internet?

- Is the Internet “making us stupid”?

mass communication

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

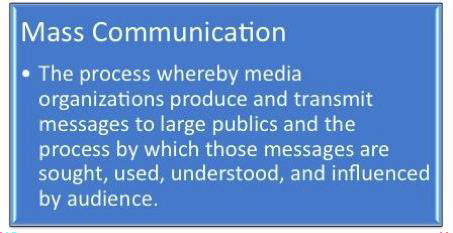

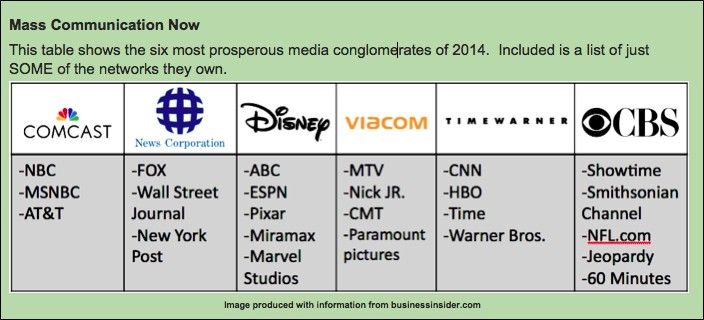

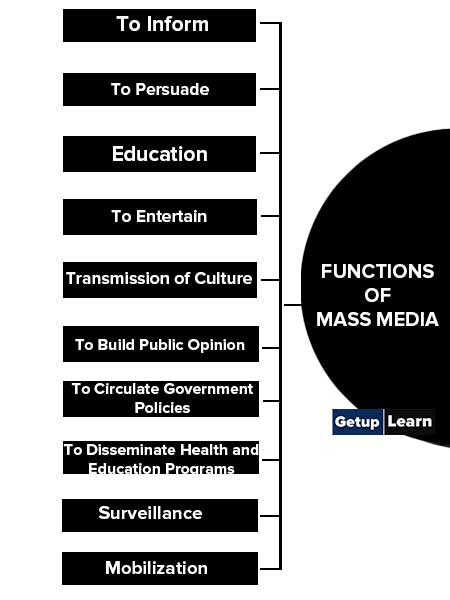

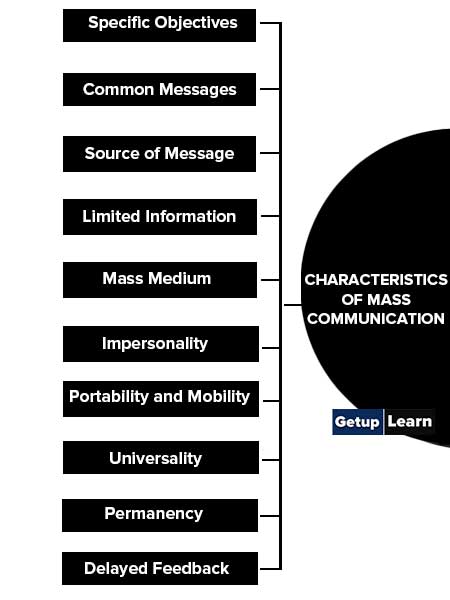

mass communication , process of sharing information with a large audience. Mass communication is accomplished via mass media —that is, technology capable of sending messages to great numbers of people, many of whom are unknown to the sender (e.g., television ). The purposes of mass communication include entertainment, education , and political propaganda . Among the fields of endeavour that engage in mass communication are marketing , public relations , and journalism .

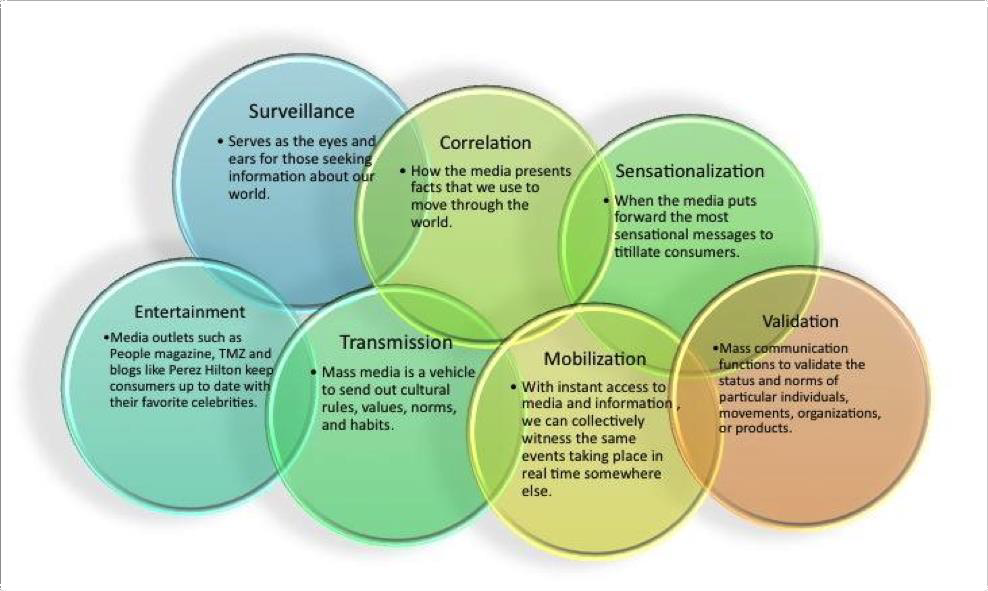

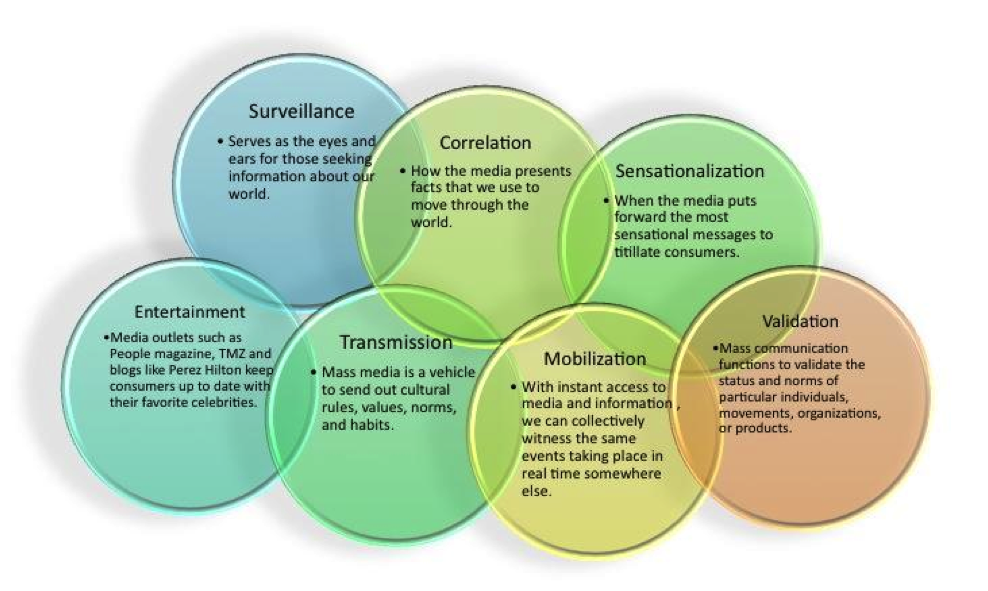

Mass communication is a complicated phenomenon. Its use has had a significant impact on society, shaping not only cultural norms and values but also the way people perceive and interact with the world. It disseminates new ideas and beliefs, and it affects its audiences’ buying habits, styles, schedules, and health. The producers of content for mass media have the power to set the agenda for public discourse by determining which issues are deemed most important—or, indeed, which issues receive any attention at all. Consequently, political power relies in part on the effective use of mass communication. The field of mass communication is therefore broad and encompasses many different areas. Scholars research how mass media is produced, deployed , consumed, and otherwise used, but they also study the legalities and ethics involved in mass communication, the ultimate effect of mass media on those who consume it, and other related political, social, and cultural issues. Among the many theories that have resulted from this intellectual inquiry are the two-step flow model of communication , which is concerned with how information is filtered through active media users who act as opinion leaders for less active media consumers; the spiral of silence theory , which suggests that people with minority opinions tend to censor themselves; and the uses and gratifications theory, which posits that people do not simply receive information but rather seek out the information that they need or want.

Opportunities for mass communication first appeared with the invention of writing . A pharaoh, for example, could make proclamations to his subjects via hieroglyphics on a monument. However, the age of widespread mass communication is often said to have begun in the 15th century with Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press , which made it possible to produce books, pamphlets, and other printed materials at relatively low cost. Gutenberg’s creation led not only to the dissemination of information but also to the spread of literacy and education, as people adapted to take advantage of the new opportunities the press offered. The technology of sharing the written word was thus democratized, making mass communication possible for the masses themselves.

Another leap forward occurred in the 19th century: In 1844 Samuel Morse completed the first large-scale telegraph line, allowing for the rapid transmission of messages over long distances using electrical signals. This system led to the development of the first news agencies, such as the Associated Press (AP) in the United States , which were able to gather and disseminate news from around the world in a matter of minutes. It has been argued that among the effects of this innovation was a consolidation of the national character as people in disparate regions simultaneously reacted to the same news, often with the same emotions.

In the early 20th century, mass communication became ubiquitous and instantaneous. The popularization of motion pictures in the first decades of the century and of radio in the 1920s brought heightened immediacy to mass communication and revolutionized not only the news but also music, politics, and entertainment. Celebrity culture , consumer culture, and other aspects of modern society all began to manifest in ways that are still recognizable today. Moreover, the effectiveness of these new methods of mass communication further homogenized their audiences, giving rise to an ever more identifiable mass culture . When the television replaced the radio as the public’s mass medium of choice in the 1950s, these societal changes only accelerated.

With the development of the Internet and the proliferation of digital media in the 21st century, almost every aspect of mass communication has again changed dramatically. Like Gutenberg’s press, new technologies have resulted in the more equitable distribution of the ability to communicate with large audiences. Once, only the owners of newspapers, radio stations, and television broadcasters possessed the means of influencing popular opinion, but now anyone can participate in the public forum through social media , blogs, and other online platforms. The effect of this more diverse and decentralized media landscape has been the dissemination of a wider range of voices and perspectives.

However, the age of information has also led to concerns about the spread of misinformation and “fake news.” The ease with which information can be shared and spread online has also made it easier for misinformation to be spread quickly and widely. Documented consequences include risks to public health , financial losses, and the spread of extreme ideologies . Calls for increased media literacy and education have been made so that people can better discern the credibility of the information they are consuming.

Mass Communication, Media, and Culture - An Introduction to Mass Communication

(32 reviews)

Copyright Year: 2016

ISBN 13: 9781946135261

Publisher: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Jenny Dean, Associate Professor, Texas Wesleyan University on 2/27/24

This book is pretty comprehensive, but it is getting old in the media world where things are changing at a great pace. The basic text is good, but needs supplementary materials to truly keep pace with technology today. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

This book is pretty comprehensive, but it is getting old in the media world where things are changing at a great pace. The basic text is good, but needs supplementary materials to truly keep pace with technology today.

Content Accuracy rating: 3

I am sure the book was accurate when it was published, but the world keeps changing, and it isn't as current as it needs to be. But, it still isn't bad for a free book to access.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 3

Once again, same issue. The book is almost seven years old and hasn't been updated. The issue is that the examples and illustrations are getting to be a bit dated. I suspect that there aren't any updates of this book planned, which is unfortunate. If updated, this would be a fantastic read for students.

Clarity rating: 5

It is simple to read and is easily accessible. It meets the needs of a young college student.

Consistency rating: 5

Yes, the textbook is internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework.

Modularity rating: 5

It is well-subdivided and easy to access. Good use of subheadlines. It is a smooth read, and easy to find information through headers, subheads, headlines, and blocks of type.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Everything is presented in a clear and concise manner.

Interface rating: 5

This textbook comes in a wide variety of formats and can be accessed by almost everyone through one method or another. It was super easy to access.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

The text is clean and clear of errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

I don't think this book is as inclusive as the typical book written today. This is simply because times have changed, and the need for inclusive and culturally sensitive books has escalated exponentially from the time this book was written. It needs more culturally relevant examples. I wouldn't say that anything in the book is culturally insensitive or offensive, but it isn't as diversified as it needs to be.

This is an excellent book for an introduction to mass communication or an introduction to media and society course. It covers all the basics that I would expect to cover. It just needs some updating which can be done through supplementary materials.

Reviewed by Ryan Stoldt, Assistant Professor, Drake University on 12/15/22

Understanding Media and Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication thoughtfully walks readers through popular media and connects these media to questions about culture as a way of life. The book undoubtedly is comprehensive in its scope of... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

Understanding Media and Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication thoughtfully walks readers through popular media and connects these media to questions about culture as a way of life. The book undoubtedly is comprehensive in its scope of American media but largely fails to consider how media and culture relate in more global settings. The book occasionally references conversations about global media, such as the differences between globalization and cultural imperialism approaches, but is limited in its engagement. As media have become more transnational their reach and scope (due to technological access, business models, and more), the American focus makes the text feel limited in its ability to explain the relationship between media and culture more broadly.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The text is accurate although it has limited engagement in some of the topics it explores. As such, this would be a good introductory text but would need to be paired with additional resources to dive into many topics in the book with both accuracy and nuance.

Many of the sections of the book are relevant, as the book often contextualizes media through a historical lens. However, the more current sections of the book (such as the section on the Internet and social media) have become outdated quickly. These, once again, would be useful starting places for classroom conversation about the topic but would need to be paired with more current readings to hold a deeper conversation about social media and society today.

Some terms could be further explained, but the text is overall well written and easy to understand.

Consistency rating: 4

The book pulls from multiple approaches to researching and discussing media and culture. The introductory chapter draws more heavily from critical media studies in its conceptualizations of the relationship between media and culture. The media effects chapters draw more heavily from more social scientific approaches to studying media. The author does a nice job weaving these approaches into a consistent conversation about media, but different approaches to studying media could be more forwardly discussed within the text.

The author has made the text extremely easy to use modularly. Chapters are self-contained, and readers could easily select sections of the book to read without losing clarity.

The book employs consistent organization across the subjects discussed. Each chapter follows a similar organizational structure as well.

Interface rating: 4

Because the text is so modular, the text does not flow easily when read on the publisher's website. Yet, downloading the text also raises some issues because of strange formatting around images.

I have not seen any grammatical errors.

As stated previously, the book is extremely biased in its international representation, primarily promoting Americans' engagements with media. The book could go further in being more representative of different American cultures, but it is far from culturally insensitive.

Understanding Media and Culture would be an extremely useful introductory text for a class focusing on American media and society. A more global perspective would require significant engagement with other texts, however.

Reviewed by David Fontenot, Assistant Professor, Metropolitan State University of Denver on 11/15/22

The text comprehensively covers forms of media used for mass communication and includes issues towards emerging forms of mass communication. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

The text comprehensively covers forms of media used for mass communication and includes issues towards emerging forms of mass communication.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

In some places there is nuance missing, where I feel brief elaboration would yield significantly clearer comprehension without bias or misleading associations about media's influence on behavior.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

Still relevant and up-to-date with a valuable emphasis on issues related to internet mass media.

Very readable, with little jargon. Definitions are presented clearly and used in subsequent discussions.

Internal consistency is strong within the chapters.

Modularity rating: 4

The majority of chapters can be taken independently, with only a few larger structural pieces that lay the foundation for other sections.

The book takes an historical approach to media, which lends itself to a logical progression of topics. I might suggest, however, that for most students the material that is most accessible to their daily lives comes last with such an approach.

Interface rating: 3

The downloaded file has some very awkward spots where images seem clipped or on separate pages than the content that reference them. I only viewed this textbook in the online downloaded PDF format.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

No grammatical errors have jumped out at me in sections read so far.

There are quite a few opportunities to include discissions of media and culture that don't seem so anglo-centric but they are passed up.

I am using this textbook as the basis for an interdisciplinary class on media and the criminal justice system, and in that regard I think it will serve very well for an introductory level textbook. It provides a concrete set of core ideas that I can build off of by creating tailored content to my students' needs.

Reviewed by Elizabeth Johnson-Young, Assistant Professor, University of Mary Washington on 7/1/22

Appropriately comprehensive. Having some more up-to-date citations, particularly in the media effects theories criticisms section (with some more explanations) would be beneficial--perhaps supplementing with some ways these have been updated would... read more

Appropriately comprehensive. Having some more up-to-date citations, particularly in the media effects theories criticisms section (with some more explanations) would be beneficial--perhaps supplementing with some ways these have been updated would help a class.

Overall, content is clear and accurate.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

Mass media may always need updating, but this is appropriate and up-to-date.

Clarity rating: 4

Is an accessible text in terms of clarity and provides necessary definitions throughout in order to provide the reader with an understanding of the terminologies.

Text introduces terms and frameworks and uses them consistently throughout.

Small, easy to read blocks of text--could easily be used in a variety of courses and be reorganized for a particular course.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

Topics presented clearly and in an order that makes sense.

Easy to read through and images clear and displaying readily. It would help if there was a way to move forward without having to click on the table of contents, particularly in the online format.

No errors that stick out.

While appropriately comprehensive for an intro text, more examples and/or acknowledgment of who has been left out and those impacts could be helpful in the social values or culture discussions.

Overall, this is a great text and one that could be used in full for a course or in sections to supplement other communication/media studies courses!

Reviewed by David Baird, Professor of Communication, Anderson University on 4/18/22

I don’t know if any intro textbook can cover “all areas and ideas,” but this text was adequate to the task—basically on par with any other textbook in this space. I didn’t see a glossary in the chapters or an index at the back of the book. On the... read more

I don’t know if any intro textbook can cover “all areas and ideas,” but this text was adequate to the task—basically on par with any other textbook in this space. I didn’t see a glossary in the chapters or an index at the back of the book. On the other hand, the text is searchable, so the lack of an index is not a major problem as far as I’m concerned.

When the text was published, it would have been considered “accurate.” The content was competently conceptualized, well written and reflective of the standard approach to this kind of material. I didn’t notice any egregious errors of content aside from the fact that the book was published some years ago is no longer very current.

The primary weakness of the book is that it was published more than a decade ago and hasn’t been updated for a while. The text is relevant to the focus of the course itself, but the examples and illustrations are dated. For example, the book uses a graphic from the presidential election of 2008 in a treatment of politics, and “Who Wants to be a Millionaire?” is an example of current television programming.

I conducted a text search that tabulated the number of references to the following years, and these were the results: 2010: 588 2011: 49 2012: 8 2013: 4 2014: 0 2015: 2 2016: 0 2017: 0 2018: 1 2019: 1 2020: 0 2021: 1 2022: 1

The references to the more-recent years tended to crop up in forward-looking statements such as this one: “With e-book sales expected to triple by 2015, it’s hard to say what such a quickly growing industry will look like in the future.”

The second part of the question referred to the implementation of updates. I doubt that any updates are planned.

The text is well written and meets the usual standards for editorial quality.

The framework and "voice" are internally consistent.

The chapter structure provides the most obvious division of the text into accessible units. Each chapter also has well-defined subsections. Here’s an example from one chapter, with page numbers removed:

- Chapter 13: Economics of Mass Media

Economics of Mass Media Characteristics of Media Industries The Internet’s Effects on Media Economies Digital Divide in a Global Economy Information Economy Globalization of Media Cultural Imperialism

This aspect of the text makes sense and is largely consistent with similar textbooks in this area.

The text is available in these formats: online, ebook, ODF, PDF and XML. I downloaded the PDF for purposes of my review. The formatting was clean and easy to work with. I didn’t notice any problems that made access challenging.

I can’t say with certainty that a grammatical error or typo can’t be found in the textbook, but as I noted above, the writing is strong. I’ve seen much worse.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

The text seems to be around a dozen years old now, so it doesn’t include discussion of some of the high-profile perspectives that have surfaced in more recent years related to race, ethnicity, sexuality, etc. However, the book does discuss examples of media issues “inclusive of races, ethnicities, and backgrounds,” and this material is presented with sensitivity and respect.

This is a reasonably good resource for basic, intro-level definitions and explanations of some of the major concepts, issues and theories in the “Mass Communication” or “Media and Society” course, including:

• functions of the media • gatekeeping • media literacy • media effects • propaganda • agenda setting • uses and gratifications

The textbook also offers the standard chapters on the various media—books, newspapers, magazines, radio, television, etc. These chapters contextualize the various media with standard accounts of their historical development. My feeling is that much of the historical background presented in this book is more or less interchangeable with the material in newer textbooks.

However, the media industries have changed dramatically since the textbook was written, so all of the last decade’s innovations, developments and controversies are entirely missing. Of course, even a “new” textbook is going to be somewhat dated upon publication because of the book’s production timeline and the way that things change so quickly in the media industries—but a book published in 2021 or 2022 would be far more up-to-date than the book under review here.

The bottom line for me is that if one of an instructor’s highest priorities is to provide a free or low-cost textbook for students, this book could work with respect to the historical material—but it would have to be supplemented with carefully selected material from other sources such as trade publications, industry blogs and news organizations.

Reviewed by Kevin Curran, Clinical Assistant Professor, Loyola Marymount University on 3/21/22

This is one of the most comprehensive media studies books I’ve read. It attacks each media platform separately and with sufficient depth. That is followed by economics, ethics, government/law, and future predictions. Takeaways attend of each... read more

This is one of the most comprehensive media studies books I’ve read. It attacks each media platform separately and with sufficient depth. That is followed by economics, ethics, government/law, and future predictions.

Takeaways attend of each section will aid comprehension. Exercises at end of sections could be jumping off point for discussions or assignments. Chapters end with review and critical thinking connections plus career guidance.

The Chapter 2 rundown on both sides of media theories and summary of research methods was well-done.

Everything about this tome is good, except for its dating.

The book is well-researched and provides valuable, although often dated, information. The author used a variety of sources, effective illustrations, and applicable examples to support the points in the book.

It can be very hard to keep up with constant changes in the mass media industry. This book was reissued in 2016, but it has not been revised since the original copyright in 2010. The dated references start on page 2 when it speaks of Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey as existing, when that circus ceased in 2017. The medium-by-medium exploration is well done, although the passage of time affects the end of each chapter.

Adoption of the book as-is will mean developing an update lesson for each chapter. For example, while smartphones are mentioned, they had not achieved saturation status at the time this volume was published.

The points are presented clearly. References with hyperlinks are available at the end of each section for those who still have questions or want more information. However, it is possible that because of the age of the book, some of those links may no longer be available.

The media chapters each follow a similar pattern in writing and order.

This will break up easily. The first chapter gives a good taste of what is to come. The book provides a comprehensive look at the history and influence of each medium individually. The last group of chapters necessarily contains many flashbacks to the medium sections.

It follows a logical pattern from the introduction to the individual medium chapters to the “big picture” chapters. That does require signposting between the two sets of chapters that some might find frustrating.

Interface rating: 2

The book is a standard PDF with links. The scan could have been better, as there is a lot of white space and illustrations are inconsistently sized. Users hoping for lots of interactivity are going to be disappointed.

The book is well edited. It is hard to find errors in writing mechanics.

The authors took a broad view of the mass media world. The music chapter was very well done.

Reviewed by Lisa Bradshaw, Affiliate Faculty, Metropolitan State University of Denver on 11/26/21

This textbook, downloaded as a 695-page PDF, contains 16 chapters and covers a variety of media formats, how they evolved, and how they are created and used, as well as issues related to media impact on society and culture. It is quite... read more

This textbook, downloaded as a 695-page PDF, contains 16 chapters and covers a variety of media formats, how they evolved, and how they are created and used, as well as issues related to media impact on society and culture. It is quite comprehensive in its coverage of media for the time of its writing (copyright year 2016, “adapted from a work originally produced in 2010”).

Content seems accurate for its time, but as technology and media have evolved, it omits current references and examples that did not exist when it was written. There does not seem to be bias and a wide variety of cultural references are used.

As mentioned previously, this textbook’s copyright year was 2016, and it was adapted from a 2010 work. It’s not clear how much of the content was updated between 2010 and 2016, but based on the dates in citations and references, the last update appears to have been in 2011. Even if it had been updated for the year 2016, much of the information is still out-of-date.

There is really no way to write a textbook about media that would not be at least partially out of date in a short time. This text’s background and history of the evolution of the various media forms it covers is still accurate, but there is much about the media landscape that has changed since 2010–2016.

Due to the textbook’s age, references to media platforms and formats such as MySpace, Napster, and CDs seem outdated for today’s media market. The textbook refers to previous political figures, and its omission of more recent ones (who were not on the political landscape at the time of writing) makes it seem out-of-date. To adapt it for modern times, these references need to be updated with fresh examples.

The writing level is relatively high. A spot check of the readability level of several passages of text returned scores of difficult to read, and reading level 11-12 grade to college level. The author does a good job of explaining technical terminology and how different media work. If adapting the text for students with a lower level of reading, some of the terminology might need to be revised or explained more thoroughly.

The text is consistent in its chapter structure and writing style. The order of topics makes sense in that chapters are mostly structured by media type, with beginning and end sections to introduce each respective media type in general, and conclude with a look to the future.

If adapting and keeping the same structure (intro to media in general, coverage of different media types in their own chapters, and main issues related to media), this 695-page textbook could be condensed by eliminating some of the detail in each chapter. There are a number of self-referential sentences that might need to be removed. If adapting the text to a more specific subject, the instructor would need to go through the text and pick out specific points relevant to that subject.

Each chapter introduces the respective media type and concludes with a summary that reflects on the future of that type and how it might evolve further. The chapters overall follow the same structure for consistency: overview, history, the media in popular culture, current trends, and potential influence of new technologies, with end-of-chapter Key Takeaways, Exercises, Assessment, Critical Thinking Questions, Career Connection, and References.

The text is well written and logically structured and sequenced. Despite its length, it’s easy to find information, as it’s ordered by chapters that address each media type and major issues related to media, and each chapter has a parallel structure with the others, all following mostly the same pattern.

I did not notice grammatical errors. The text is clearly and accurately written, and appears to have been thoroughly copyedited and proofread.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

I did not notice cultural insensitivity in the text. A wide variety of cultural references are used. Examples from around the world and from many different cultures are included, including discussions of digital divide and inequity issues related to media access in disadvantaged populations.

Reviewed by Adria Goldman, Assistant Professor of Communication, University of Mary Washington on 7/11/21

The text nicely breaks down different forms of mass communication. The text provides some historical background and discussion of theory to provide context for discussing mass media, which is all useful in helping students understand media and... read more

The text nicely breaks down different forms of mass communication. The text provides some historical background and discussion of theory to provide context for discussing mass media, which is all useful in helping students understand media and communication. There is not much discussion about the cultural significance of media. If using the text in a course, supplemental readings on the significance of culture and diversity, the importance of media representation, and media influence on an individual level (ex: impact on identity), would be especially helpful for a course exploring media and culture. The text does not feature a glossary or index, however the bolding of key concepts throughout the text is helpful in defining key terms.

The content is error-free. More discussion on culture would provide a more accurate account of mass communication and its significance.

The subject is very relevant and the book features topics important for a discussion on mass communication. As mentioned in other parts of this review, there is not much diversity featured throughout the text, which can impact the relevancy of the material to audiences and impacts the relevancy of the content in discussions on mass media and society. Updates would be straightforward to implement.

The text is clear and easy to follow.

The text is consistent in its use of terms and its framework. Since the book title mentions a focus on culture, an interesting add-on would be to have each section (on a specific type of mass communication) feature a discussion of culture and its significance.

The text's modularity is useful. It looks like it would be easy for students to follow and for instructors to re-structure in order to fit their course design.

The information follows a logical order, beginning with a discussion on the significance of mass communication and then going into each type.

No issues with interface noted.

No glaring grammatical issues noted.

Cultural Relevance rating: 2

There is not much focus on the significance of culture. More discussion on the role of race, class, sex, gender, religion and other elements of identity would be helpful in exploring mass communication--past, present, and potential for the future. The text could also use an update in images and examples to include diverse representation and to further communicate the role of culture, diversity, and representation in communication and mass media.

The book provides an understanding of mass communication that would be easy for undergraduate college students to follow. The optional activities would also spark interesting discussion and give students the opportunity to apply concepts. Students using the text would benefit from (1) more discussion on culture's significance in media and communication and (2) more diversity in the images and examples used.

Reviewed by Brandon Galm, Instructor in English/Speech, Cloud County Community College on 5/4/21

One of the strong suits of this particular resource is its comprehensiveness, with topics ranging from specific mass comm mediums to the intersections/impacts of media on culture, politics, and ethics. There's enough here to easily cover a full... read more

One of the strong suits of this particular resource is its comprehensiveness, with topics ranging from specific mass comm mediums to the intersections/impacts of media on culture, politics, and ethics. There's enough here to easily cover a full semester's worth of material and then some.

The content is well-sourced throughout with a list of references at the end of each chapter. The hyperlinks on the references page all seem functional still. Hyperlinks within the chapters themselves--either sending the reader to the reference list or to the articles themselves--would be helpful.

As of this review writing, some of the content is relatively up-to-date. However, with a quickly changing landscape in mass communications and media, certain chapters are becoming out-of-date more quickly than others. The information discussed is more current than most of the information cited. The structure of the book lends itself to easy updating as technologies and culture shift, but whether or not those updates will take place seems unclear with the most recent edition being 5 years old at this point.

All information is presented in a way that is very clear with explanations and examples when further clarification is needed.

For a book covering as many different topics as it does, the overall structure and framework of this textbook is great. Chapter formats stay consistent with clearly stated Objectives at the start and Key Takeaways at the end. Visual examples are provided throughout, and each chapter also includes various questions for students to respond to.

Chapters are broken down into smaller sub-chapters, each with their own sub-headings hyperlinked in the Table of Contents. Each sub-chapter also includes the above-mentioned Objects, Key Takeaways, and questions for students. Chapters and/or sub-chapters could easily be assigned in an order that fits any syllabus schedule and are in no way required to be read in order from Chapter 1 to Chapter 16.

I would like to have seen the book laid out a bit differently, but this is a minor concern because of the overall flexibility of assigning the chapters. The book starts with broad discussions about media and culture, then shifts into specific forms of media (books, games, tv, etc.), then returns to more broad implications of media and culture. Personally, I'd like to see all of those chapters grouped together--with all of the media and culture chapters in one section, and all of the specific forms chapters in another. Again, this is a minor issue because of the overall flexibility of the book.

As mentioned above, hyperlinks--including in the Table of Contents and references--are all functional. I would have liked to have hyperlinks for the references in the text itself, either as a part of the citation or with a hyperlinked superscript number, rather than just in the references page. All images are easily readable and the text itself is easy to read overall.

No grammatical errors that immediately jumped out. Overall seems clear and well-written.

The text provides lots of examples, though most do come from US media. The sections dealing with the intersections between media and culture are similarly US-centric.

Overall, a solid introductory textbook that covers a wide range of topics relevant to mass communications, media, and culture. The text is bordering on out-of-date at this point, but could easily be updated on a chapter-by-chapter basis should the publisher/author wish to do so.

Reviewed by Dong Han, Associate Professor, Southern Illinois University Carbondale on 3/30/21

It covers all important areas and topics regarding media, culture, and society. Different media forms and technologies from printing media to social media all have their own chapters, and academic inquiries like media effects, media economics,... read more

It covers all important areas and topics regarding media, culture, and society. Different media forms and technologies from printing media to social media all have their own chapters, and academic inquiries like media effects, media economics, and media and government also receive due attention. This textbook will meet the expectation of students of all backgrounds while introducing them to theoretical concerns of the research community. Its chapter layout is properly balanced between comprehensiveness and clarity.

Its content is accurate and unbiased. The textbook is written with ample research support to ensure accuracy and credibility. References at the end of each chapter allow readers to track sources of information and to locate further readings.

It is up-to-date in that the major cultural and media issues it identifies remain highly relevant in today’s world. However, since it was first produced in 2010, some more recent occurrences are not part of the discussion. This is not meant to be a criticism but a reminder that an instructor may want to supplement with more recent materials.

It is written with clear, straight-forward language well-suited an introductory textbook. The chapter layout, as mentioned earlier, is easy to access.

The book is consistent in terms of terminologies and its historical approach to media growth and transformation.

Each chapter is divided in sections, and sections in turn have various reading modules with different themes. For undergraduates taking an introductory course, this textbook will work well.

The topics are presented in an easy-to-access fashion. The textbook starts with a general overview of media and culture and a persistent scholarly concern with the media: media effects. Then it moves through different media in alignment with the chronological order of their appearance in history. The last few chapters focus on important but non-technology-specific topics including advertising and media regulations. For an introductory textbook, it is very accessible to the general student body.

The textbook does not have significant interface issues. Images, charts, and figures all fit well with the text.

There are no grammatical errors.

The textbook has a number of examples of minority cultures and ethnicities. It does not, however, have ample discussions on media and culture phenomena outside of the US, except those that have had significant impact on American culture (e.g., Beatlemania).

All considered, this is a very good textbook to be used in an introductory course. It is comprehensive, easy-to-read, and can help prepare students for future in-depth discussions on media, culture, and society.

Reviewed by Elizabeth Johnson-Young, Assistant Professor, University of Mary Washington on 7/6/20

Comprehensive text regarding mass communication, culture, and effects. The historical perspectives are helpful for understanding, particularly as it goes on to focus in on convergence throughout the text. A more complete glossary or index would be... read more

Comprehensive text regarding mass communication, culture, and effects. The historical perspectives are helpful for understanding, particularly as it goes on to focus in on convergence throughout the text. A more complete glossary or index would be helpful for terms for an introduction text, but key terms are highlighted and defined throughout. Extra examples would help throughout, particularly with theories and research methods.

Accurate, up to date information on history, concepts, and theories.

The information focuses on important historical moments, theories, cultural impacts, and moves to the present with ideas and examples that will likely remain relevant for quite some time.

Clear, easy to read text that would benefit introductory students of mass comm.

Introduces terms and concepts and then utilizes them throughout.

The separation of the larger text into smaller sections is incredibly helpful and makes reading and assignments of readings easy, leading also to the ability to separate into sections that would be appropriate for any course organization.

Organization is logical and easy to follow. Importantly, because of the modularity, it would also be easy to re-organize for one's course.

Navigation works, images clear and detailed.

No glaring grammatical errors.

The examples and images demonstrate diversity in race and also provides examples outside of the United States, which is important. There is some diversity in terms of gender and sexual diversity, more of which would be beneficial and various sections would be appropriate for that inclusion.

This is an excellent and comprehensive text for intro students that includes important historical moments and thorough coverage of main concepts and theories in the field, with a diverse set of moments and examples.

Reviewed by Emily Werschay, Communication Studies Instructor, Minnesota State University System on 10/22/19

Overall, this textbook is quite comprehensive in covering various channels of media, particularly from a historical perspective, and would work well for an introductory course. It features the same focused areas of content that are in my current... read more

Overall, this textbook is quite comprehensive in covering various channels of media, particularly from a historical perspective, and would work well for an introductory course. It features the same focused areas of content that are in my current publisher textbook and incorporates elements of culture as well. It does not provide a glossary or index, which would be helpful, but key terms are in bold.

The text contains accurate research with clearly-cited references that give credibility to the content.

The historical content is well-crafted. The text provides a clear and informative introduction to the history of media and does well with the rise of newspapers, television, and movies. You will not, however, find a reference more recent than 2010, which means any advancements in media and technology in the past decade are not covered. An instructor using this text would have to supplement content on current types of media such as streaming television and music services and the current debate of social media shifting toward news publishing in terms of content delivery. While the text includes culture and political climate of the past, much would need to be supplemented for the last ten years.

The text is professional and well-written. It is well-suited to a college reading level.

The chapter format, writing style, and overall presentation of information are consistent throughout the text. I appreciate the defined learning outcomes and key takeaways pulled out in each chapter.

The text is divided into clear chapters focusing on one medium at a time, much like other publisher texts for mass communication. For example, books, newspapers, magazines, music, radio, movies, and television each get their own chapter. Each chapter begins with clearly defined learning outcomes, and features key takeaways, exercises, assessments, and critical thinking questions at the end, as well as a section on career connections.

The topics are presented in chronological order from the history of mass communication, through the various mediums, and finally to the future of mass communication (though most will find the content particularly about recent and current trends will need to be supplemented as it is outdated).

I didn't find any problems with the interface as it is a standard text that can be viewed as a PDF, but an index would really help navigation. I will say that it's not particularly user-friendly, so I may try integrating the online format chapter-by-chapter into D2L so that I can break it up by modules and add links to make it more interactive with supplemental resources.

Professional, well-written text with no errors.

I don't believe readers will find any of the text culturally insensitive or offensive. The text is focused on U.S. media, however, so some supplemental content may be needed.

This textbook is very comprehensive and will work well for an introductory course. It covers the same focus areas as my publisher text, so I feel comfortable switching to this textbook for my Introduction to Mass Communication course with the awareness that it does not cover the past decade. I will need to provide supplemental information to update examples and cover current topics, but that is generally accepted in this particular field as it is continually changing with advancements in technology.

Reviewed by Bill Bettler, Professor, Hanover College on 3/8/19

This text is comprehensive on several levels. Theoretically, this text echoes the framework employed by Pavlik and McIntosh, which displays sensitivity to convergence. However, this text understands convergence on multiple levels, not just the... read more

This text is comprehensive on several levels. Theoretically, this text echoes the framework employed by Pavlik and McIntosh, which displays sensitivity to convergence. However, this text understands convergence on multiple levels, not just the three employed by P and M. This text is well-researched, with ample citations on a whole host of media topics. Each chapter has multiple ways that it tests the reader, with "Key Takeaways," "Learning Objectives," etc. And finally, the text features chapters on the history and development of key historical media, as well as key emerging media.

Some students find Pavlik and McIntosh a bit too transparent in their Marxist assumptions. While this text certainly introduces Marx-based theories about media, it seems to do a better job of contextualizing them among several other competing perspectives.

Some of the popular culture texts felt a bit dated--for example, opening the "Music" chapter (Chapter 6) with an extended case study about Colbie Caillat. Unfortunately, this is the nature of mass media studies--as soon as books come into print, they are out of date. But I have a hard time imagining my mass communication students being inspired and engaged by a Colbie Caillat case study. I'm not sure what the alternative is; but it seemed worth mentioning. Other examples are much more effective and successful. The historical examples from different types of media are well-chosen, thoroughly explained, and insightful. Also, this text discusses emerging media more successfully than any other texts I have used.

The style of this text is straightforward and scholarly. It seems to strike an effective balance between accessibility and specialized language. For example, key concepts such as "gatekeeper" and "agenda setting theory" are introduced early and applied in several places throughout the text.

Like Pavlik and McIntosh, this text uses the concept of "convergence" to explain several key phenomena in mass communication. Unlike P and M, this text understands "convergence" on more than three levels. Like P and M, this concept becomes the "glue" that holds the various topics and levels of analysis together. As mentioned before, this text is especially effective in that it introduces foundational concepts early on and applies them consistently across succeeding chapters.

On one hand, this text rates highly in "modularity," because I could imagine myself breaking its chapters apart and re-arranging them in a different order than they are presented here. This is in no way meant as a criticism. I routinely have to assign chapters in more conventional texts in a different order. The fact that the technology involved in delivering this text makes it easier to re-arrange is one of its best selling points. The reason I scored this as a "4" is because some of the chapters are quite dense, in terms of volume (not in terms of difficulty). Therefore, I could see students perhaps losing focus to some degree. I might combat this by making further breakdowns and re-arrangements within chapters. This is not a fatal flaw--but it does seem like a practical challenge of using this text.

As mentioned above, some of the chapters are quite dense, in terms of volume. Chapter One is such a chapter, for example. I could easily see Chapter One comprising two or three chapters in another textbook. Consequently, there is a likelihood that students would need some guidance as they read such a dense chapter; and they would likely benefit from cutting the chapter down into smaller, more easily digestible samples. On the other hand, the Key Takeaways, and Learning Objectives, will counteract this tendency for students to be overwhelmed or confused. They are quite helpful, as are the summarizing sections at the ends of each chapter.

I did not encounter any problems with interface. In fact, the illustrations, figures, charts, photographs, etc. are a real strength of this text. They are better than any other text I have seen at creating "symbolic worlds" from different forms of media.

The writing style is professional and free of errors.

This is a genuine concern for mass media texts. Media content is a direct reflection of culture, and today's culture is characterized by a high level of divisiveness. I did not detect any examples or samples that were outwardly offensive or especially controversial. But, perhaps, there is a slight bias toward "the status quo" in the case studies and examples--meaning that many (but certainly not all) of them seem to be "Anglo," Caucasian artists. Looking at the "Music" chapter, for example, some popular culture critics (and students) might lament that Taylor Swift is an exemplar. While this choice is undeniable in terms of the popularity of her recordings and concerts, some might hope for examples that represent stylistic originality, genre-transcending, and progressive ideas (Bruno Mars, Kendrick Lamar, Jay-Z, Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, etc.).

I have been using the same text for seven years (Pavlik and McIntosh). I have decided to adopt Understanding Media and Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication. It is simply more thorough in its sweep of history and contextualization of culture, more multi-layered in its theoretical perspectives, and more rich in its examples and insights. This books is recommendable not just as an open source text, but as it compares to any conventional text. Students will benefit greatly from reading this text.

Reviewed by Hsin-Yen Yang, Associate Professor, Fort Hays State University on 11/29/18

Understanding Media and Culture: an Introduction to Mass Communication covers all the important topics in mass communication and media history. It also provides case studies, Key Takeaways, Exercises, End-of-Chapter Assessment, Critical Thinking... read more

Understanding Media and Culture: an Introduction to Mass Communication covers all the important topics in mass communication and media history. It also provides case studies, Key Takeaways, Exercises, End-of-Chapter Assessment, Critical Thinking Questions, and Career Connections in every chapter. Although this book does not provide a glossary, the comprehensiveness of the book still makes it a great textbook choice.

While the information was accurate and the discussions on key issues were supported by good references, it was odd to see the questionable formatting and quality of the first reference on page 3: Barnum, P. T.” Answers.com, http://www.answers.com/topic/p-t-barnum. --> First of all, Answers.com is not considered as a credible source by many scholars and the other half of the quotation marks was missing.

The major weakness of this book is the fact that many of the references were outdated. For example, on page 479, the statistics in the section, "Information Access Like Never Before," the cited reports were from 2002 and 2004. When discussing topics such as Net Neutrality, digital service providers, new policies and technologies, the urgency for updated information becomes evident. However, as the author correctly pointed out: "Although different forms of mass media rise and fall in popularity, it is worth noting that despite significant cultural and technological changes, none of the media discussed throughout this text has fallen out of use completely."

The writing in this book is very clear and easy to understand. The colored images, figures and tables should be very helpful in terms of student comprehension and engagement.

The framework and terminology are consistent throughout the book.

Each chapter can be assigned to students as a stand-along reading, and can be used to realign with other subunits should an instructor decide to compile reading within this book or from different sources.

Each chapter follows similar flow/ format: the history, evolution, economics, case studies and social impact of a mass medium, followed by Key Takeaways, Exercises, End-of-Chapter Assessment, Critical Thinking Questions, Career Connections and References. It was easy to navigate the topics and sections in this book.

I downloaded the book as a PDF and had no problem to search or navigate within the file. The book can also be viewed online or in a Kindle reader.

I spotted a few minor formatting or punctuation issues such as the missing quotation marks stated earlier, but no glaring errors as far as I know.

While it mainly focuses on American media and culture, this book contains statistics and cases from many countries (e.g. Figure 11.7), provides many critical thinking exercises and is sensitive towards diverse cultures and backgrounds.

Overall, this is a high-quality textbook and it contains almost all the key issues in today's media studies in spite of the somewhat outdated data and statistics. The strengths of this book are: Excellent historical examples, critical analysis and reflections, clearly defined key issues and in-depth discussions. Even when using the most recent edition of textbooks, I always research for updates and recent cases. This open resource textbook makes an outstanding alternative to those high-priced textbooks.

Reviewed by Hayden Coombs, Assistant Professor, Southern Utah University on 8/2/18

Perhaps the best quality of this text, Understanding Media and Culture is a very comprehensive textbook. I have used this text in my Mass Media & Communication course for two years now. Each chapter focuses on a different type of medium,... read more

Perhaps the best quality of this text, Understanding Media and Culture is a very comprehensive textbook. I have used this text in my Mass Media & Communication course for two years now. Each chapter focuses on a different type of medium, starting with the earliest books and working its way up to the latest technological advancements in mass media. Other beneficial topics include: Media & Culture, Media Effects, Economics of Mass Media, Media Ethics, Media and Government, and the Future of Mass Media. These topics provide a solid base for a 100 or 200-level introductory communication course. They also were written in a way that each chapter provided sufficient material for a week's worth of discussion.

This book was written in a very unbiased manner. It is completely factual, and not much room is left for subjective interpretation. The discussion questions allowed multiple themes and schools of thought to be explored by the students. Because this book is intended for an introductory course, the information is fairly basic and widely-accepted.

My biggest issue with this title was that the latter chapters were not written with the same quality as the first ten or so chapters. However, that was the thought I had after the first semester I used this text. Since then, multiple updates have been written and the entire text is now written in the same high-quality throughout. Because this title is being constantly updated by its authors and publishers, the text is never obsolete.

Terminology is clearly defined, and students have little trouble finding definitions in the glossary. Because this text is written for an introductory course, there are not many intense or confusing concepts for students to understand.

Consistency rating: 3

As previously mentioned, the biggest struggle I've had with this text is the fact that the latter third was not written to the same quality of the first ten chapters. However, this issue seems to have been remedied in the latest edition of this text.

The modularity was the biggest selling point for me with this text. Our semester runs 15 weeks, the same number of chapters in this text. I was able to easily focus our classroom discussions and assignments on the chapter theme each week. The text also provides plenty of material for two or three discussions.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 3

The text starts by introducing some basic concepts like culture and effects. From there, it focuses on ten different types of media (books, newspaper, radio, television, etc.). The concluding three chapters go back to concepts such ethics and the future of mass media. While not a major issue, there was a major difference in the tone of the two types of chapters.

This text is available in .pdf, kindle, .epub, and .mobi formats, as well as in browser. While nothing fancy or groundbreaking in terms of usability, it is simple and all of my students were able to download the format that best suited their individual needs.

The text contained no grammatical errors that I noticed in the latest edition, a tremendous improvement from the first semester I used this text.

I did not find the content to be culturally insensitive or offensive in any way. It used a variety of examples from the world's history, but I found none of them to be inherently offensive. The subject matter and the fact that this is an introductory text probably assist with the cultural relevance because it is easy to understand, but the themes rarely get into "deep" discussion.

This is a fantastic text. Comparing it to other texts for my COMM 2200 Mass Media & Society text, this textbook was not only easier for my students to understand, but it was written and compiled in a way that made teaching the material enjoyable and easy. I have recommended this book to the other instructors of this course because it allows our students to save money without sacrificing anything in terms of content or learning.

Reviewed by Heather Lubay, Adjunct Faculty, Portland Community College on 8/2/18

Overall the book is comprehensive, covering everything from books to radio to electronic media & social media. Each topic has a descent amount of information on both the history and evolution, as well as where we are today (though, as tends to... read more

Overall the book is comprehensive, covering everything from books to radio to electronic media & social media. Each topic has a descent amount of information on both the history and evolution, as well as where we are today (though, as tends to be the nature of the industry, the “today” piece gets outdated quickly. However, the text covers the topics that most other texts of this subject cover as well. I would have liked to have seen just a bit more depth and analysis, instead of the broad, surface-level coverage.

The text is fairly accurate, though, with the rapid rate of change, it’s difficult to be accurate shortly after publication. Using sites such as MySpace as an example, or only looking at movies put out through about 2007, impacts the accuracy as society has changed and moved on. Students in 2018 are given more of a historical perspective from when they were kids more so than having a representation of what media means in today’s world.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 2

This is a hard one because the historical information stands the test of time, but many of the examples fall short for today’s students. The Social Media chapter still references MySpace and Friendster as current platforms and only goes as far as FaceBook & Twitter. The author makes it a point to clarify when the book what published, which helps, but, again, it’ll be hard for a current student to see past that when they’ve grown up with the platform being discussed as “new” and have moved on.

The book is fairly fast-paced and easy enough to follow for lower level or beginner students. Examples are easy to follow and the key takeaway boxes and exercises help further basic understanding.

The chapters are fairly consistent, covering the basic history, evolution, and influence/impact.

The text can easily be used as formatted, or broken up into sections and moved around.

The organization is fairly straightforward. Earlier forms of mass communication are covered first, moving on to newer forms. Once students have a basic understanding of each form, they can then move on to topics like ethics, government, and economics, which need that basic understanding to fully grasp the larger concepts.

The book is easy to navigate with had no issues viewing the photos or charts.

The book is well written and free of any gratuitous errors.

The book does a good job of focusing on US media and society. It uses pretty typical examples, though it could incorporate more relevant examples to today’s students. Some case studies reference minority groups, but it would have been nice to see even more examples featuring minority groups. Also, Using YouTube as a “new” viewing outlet and discussing “The war between satellite and cable television” and DirectTV versus Dish makes the cultural relevance more towards older generations than younger ones.

Overall the book does a great job with the history of mass communication and society. It would work for any lower level course. However, the examples are fairly out of date and the instructor would have to present more recent and relevant examples in class.

Reviewed by Randy (Rachel) Kovacs, Adjunct Associate Professor, City University of New York on 6/19/18

I like the way that the author has broadened the scope of the book to incorporate so many aspects of culture, society, politics and economics that some people would be inclined to distinguish from the mass media, when in reality, all these aspects... read more

I like the way that the author has broadened the scope of the book to incorporate so many aspects of culture, society, politics and economics that some people would be inclined to distinguish from the mass media, when in reality, all these aspects of contemporary life are intertwined with and influenced by media messages. It provides an historical retrospective but also shows how convergence and constantly-evolving technologies have driven the way consumers use the media and the way producers will use those technologies to rivet the attention (and influence the purchasing choices) of today’s consumers. The text incorporates the most salient areas of media’s evolution and influence.

The book appears to be objective and adopts a critical but non-partisan perspective. It presents data, including media laws and policies, accurately, and the cases it cites are well documented. The author provides sufficient references to support the facts he states and the conclusions he draws. Caveat--The media landscape and technologies are constantly evolving, so the book is accurate for its time of publication but needs to be updated to include new developments.

The way that the author integrates the historical perspective with current roles of social media in is a clear indication of its relevance. The dates may change, as may the celebrities, industrialists, spokespersons, and there may be geopolitical and cultural shifts, but the author’s explanation of theories/principles and the cases selected show how mass media power and influence are here to stay. The author advances the salient issues at each juncture and contextualizes so they we can relate them to current events. The book could be updated but is still has relevance/longevity.

The book is written in a language that is accessible to the layman/beginning student of mass media. The cases that are boxed, and key takeaways at the end of each chapter further distill what is already explicated. There are many concrete facts but a minimum of jargon and any terms used are adequately explained.

The framework and the terminology are consistent. There is also a consistent structure in terms of the visual layout and breakdown of each chapter’s sections, which makes the material far more accessible to students. It’s reassuring in a way, because students know where to go in each chapter for clarification of terms and restatement of the major media developments or areas of impact.

The book’s content is broken down within chapters into (pardon the expression) digestible chunks. The way each subsection is organized makes sense. The major sections where media, developments, policies, etc., are first introduced are illustrated by boxed portions and then reiterated clearly at the end of the chapter with small, chunked takeaways and questions that challenge the students to ponder issues more deeply. The modules are distinguished by color, typset, size of font, etc. which is aesthetically appealing.

The organization makes sense and the topics segue smoothly from one area of media focus to another. Also, the way the book opens with an overview of mass media and cultural is a good starting point from which to document specific historical eras in the development of communication and to transition from one era of communication to another within a context of technology, politics, industry and other variables.

: The text does not have any interface issues, as it is easy to navigate, all illustrations, charts, and other visuals are clear and distortion-free. All features of the book are legible and all display features are legible and functional.

The book is grammatically accurate and error-free.

The book represents a range of cultural groups in a sensitive and bias-free way. Its discussions of media with regard to both dominant cultures and various minority cultures is respectful, bias-free, and non-stereotypical. It is culturally relevant and inclusive.

For many years, I have used a textbook that I have regarded as very high quality and comprehensive, but as it has become increasingly expensive and out of reach financially for many of my students, I find it hard to justify asking my struggling students to add another financial burden to them. Why should I when they can use this OER textbook? I am seriously considering using Understanding Media and Culture in future semesters and recommending it to my colleagues.

Reviewed by Stacie Mariette, Mass Communication instructor, Anoka-Ramsey Community College on 5/21/18

This OER is very comprehensive. I used it for an online course as a PDF textbook. While this discipline evolves faster than any other communication area I teach, this book remains solidly grounded in a wide variety of resources and foundational... read more

This OER is very comprehensive. I used it for an online course as a PDF textbook. While this discipline evolves faster than any other communication area I teach, this book remains solidly grounded in a wide variety of resources and foundational theories.

As I use it more often, I find myself wanting to update it only for examples regarding the evolution in technology/platforms and the societal/cultural changes that result – not to change the historical content of what is already there.

I haven't come across any factual errors at all.

The examples in this book are often dated. This is my one very mild criticism of this text and only reflects the nature of the information. As we grow into new media and adapt as a society to those delivery methods, it's only natural. I actually use updating the examples in the textbook as an assignment for students.

Some closer to up-to-date examples that I have added into my teaching of the course and to the materials are:

"Fake news" and social media's role in spreading it, especially in terms of Facebook and the last election

Data mining and algorithm practices

"Listening" devices and digital assistants, like Siri and Alexa

The subculture of podcasts

Business models – both for artists and consumers – of streaming services across all media

The chapter on convergence is short and could be a text all on its own. Information relating to this topic is sprinkled throughout the book, but the concept itself is so important to analyze that I like to think about it on its own. This is an area I will beef up in future semesters for my own students.

Streaming services and online journalism overall are two areas that I have noted to update and reference in nearly every chapter.

The short segments and snippets of information are very helpful and clear for students. It's all very digestible and the vocabulary is at just the right level.

The discussion questions and further reading/information are placed in logical places in each chapter. And this consistency helps the reader understand their prompts and what to do next – and additionally the important topics to take away.

I love how this text can be reordered very easily. Since it's so comprehensive, I actually omit a couple of the chapters (radio and magazines) to take the info at a slower pace and have never struggled with remixing other chapters.

In fact, I plan to blend Chapters 11 and 16 (Social Media and New Technology) for my upcoming semesters and have no doubt the text and materials will allow for this.

I like how the chapters primarily focus on one medium at a time. From there, the structure of evolution, technological advancements, social/cultural implications and then a look at trends and emerging controversies helps to build to exciting and relevant discussions and for students to have the backdrop to bring their own insights.

The interface is reliable and easy-to-use. I deliver it as a PDF within my online classroom software. I have never had issues with students downloading and reading on multiple devices – or even printing and referencing – based on their preferences.

This book is very concise and grammatically crisp. It's clear that the authors of the version I am using valued precision in their language and it helps students to see this resource as high-quality!

Cultural and societal relevance are important in this discipline and it's purposely covered in each and every chapter. However, as I mentioned earlier, the examples are outdated in many cases. So I layer this into class discussions and supplement with further readings and assignments. Some of the topics I add are: Representation in entertainment media, like TV and film, for example how the #MeToo movement gained ground based on the film industry Ways that online gaming culture is permissive of the communication of –isms, like sexism and racism Ways that social media and screen time are impacting attention spans, interpersonal relationships/communication and child development How citizen-sourced video and reporting differs from that of trained journalists and how important the differences are The section on media effects is helpful and thorough. I always include a key assignment on this topic. It's also an area I plan to emphasize even more in the future – particularly the idea of tastemaking and gatekeeping. There are many crossovers to many examples that are more up-to-date than the version of the text I have been using.

I love this book and it is on-par with many others I have reviewed for my Introduction to Mass Communication class.

Reviewed by Stacy Fitzpatrick, Professor, North Hennepin Community College on 5/21/18

The presentation of the historical context of media evolution in the US is clear and reasonably detailed, providing a good foundation for an introductory level course. As other reviewers have mentioned, this text was published in 2010 and is out... read more

The presentation of the historical context of media evolution in the US is clear and reasonably detailed, providing a good foundation for an introductory level course. As other reviewers have mentioned, this text was published in 2010 and is out of date in multiple areas, particularly with respect to media laws and regulation, social media, and newer developments of technology (e.g. preference for streaming television, technological and social advancements in gaming). Beyond needing updates to reflect newer advancements in media, this text would benefit from more attention to global media structures, including how they vary across political systems and how they impact how citizens use media to communicate. Additionally, an index and glossary would be helpful for navigation.

I am basing this on the fact that this was published in 2010. Considering the publication date, the factual content for that particular time frame is presented accurately, clearly cited, and reasonably unbiased. There is perhaps an unintended gender bias in the presentation of some content (e.g. Sister Rosetta Tharpe is absent in the music section, as is Nina Simone), though this could be a result of a broader, societal gender bias. Images, charts, and graphs are used well and clearly explained.

The historical content is fine, but the text is almost 9 years out of date and there is a great deal of content that needs to be updated. Making the necessary updates may take some time since the content is tightly written and there are reflections of the date of publication throughout the examples used, images presented, and media discussed. Using this text in class would require the instructor to provide supplemental content on newer advancements in media.

This text is appropriate for a freshman/sophomore level course and reads well. Important terms are defined and each section includes an overview to set a context and clearly defined learning objectives.

The language, terminology, and organization of the text is consistent throughout. This makes moving between chapters easy since they follow a similar format.

With a few exceptions (chapters 1 and 2), the text lends itself well to using different sections at different points. Where there are self-references, there is typically a hyperlink to the section referenced. This is useful for those reading the text online, but less useful if printed sections of text were used.

Chapters 1 and 2 clearly present a structure that the following chapters follow. The only chapter that seems to really break that flow is Chapter 16, but that is more a result of the text being so out of date than a significant change in structure.

I found the online reading format the easiest to navigate. The Word and PDF versions are somewhat more awkward to navigate without using a search keyboard function.

There were a couple minor typos, but no significant grammatical errors that might impact comprehension. The readability assessment (via MS Word) indicated a reading grade level of 13.1, which is consistent with lower division college coursework.

There is a heavy focus on US media, which is acknowledged early on in the text. More integration of content related to global media would strengthen the text. There should be more examples that integrate multiple forms of diversity, such as gender, ability, age, sexuality, race, and ethnicity. Additionally, without an update, younger students may not understand some of the references. For example, younger students in 2018 don’t know Napster as a file-sharing site since it has rebranded to become a streaming site more similar to Spotify.

It would be great to see an update in the content of this text for 2018 that also incorporates broader perspectives of multiple identities and global perspectives. As is, I would use sections of the text and supplement that content with more current examples and issues. Balancing the cost of textbooks in this field with the quality and recency of the content is an ongoing challenge.

Reviewed by Craig Freeman, Director, Oklahoma State University on 5/21/18

The book covers all of the topics you would expect in an inter/ survey course. read more

The book covers all of the topics you would expect in an inter/ survey course.

The book does a good job of accurately surveying mass communications. Good job sourcing information.

The most recent citations are from 2010. That's just too far in the past for a rapidly changing subject like mass communication.

The book is clear and easy to read. Well written.

The book is internally consistent, with recurring sections.

The book does a good job breaking the information down into smaller reading sections.

The book follows the standard structure and flow for introductory texts in mass communication.

The interface is fine. It's a big book. Would appreciate active links to help skip chapters.

No grammatical errors.

I would appreciate a little more diversity in the examples used.

Really wish the authors would update this a bit. It does a great job with the history. Needs updating on the modern issues.

Reviewed by Kateryna Komarova, Visiting Instructor, University of South Florida on 3/27/18

The title Understanding Media and Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication suggests that we are looking at a comprehensive introductory text. In my opinion, this book is the most valuable to GE courses and entry level courses across Mass... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 2 see less