An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE Open Nurs

- v.7; Jan-Dec 2021

Case Study Analysis as an Effective Teaching Strategy: Perceptions of Undergraduate Nursing Students From a Middle Eastern Country

Vidya seshan.

1 Maternal and Child Health Department, College of Nursing, Sultan Qaboos University, P.O. Box 66 Al-Khoudh, Postal Code 123, Muscat, Oman

Gerald Amandu Matua

2 Fundamentals and Administration Department, College of Nursing, Sultan Qaboos University, P.O. Box 66 Al-Khoudh, Postal Code 123, Muscat, Oman

Divya Raghavan

Judie arulappan, iman al hashmi, erna judith roach, sheeba elizebath sunderraj, emi john prince.

3 Griffith University, Nathan Campus, Queensland 4111

Background: Case study analysis is an active, problem-based, student-centered, teacher-facilitated teaching strategy preferred in undergraduate programs as they help the students in developing critical thinking skills. Objective: It determined the effectiveness of case study analysis as an effective teacher-facilitated strategy in an undergraduate nursing program. Methodology: A descriptive qualitative research design using focus group discussion method guided the study. The sample included undergraduate nursing students enrolled in the Maternal Health Nursing Course during the Academic Years 2017 and 2018. The researcher used a purposive sampling technique and a total of 22 students participated in the study, through five (5) focus groups, with each focus group comprising between four to six nursing students. Results: In total, nine subthemes emerged from the three themes. The themes were “Knowledge development”, “Critical thinking and Problem solving”, and “Communication and Collaboration”. Regarding “Knowledge development”, the students perceived case study analysis method as contributing toward deeper understanding of the course content thereby helping to reduce the gap between theory and practice especially during clinical placement. The “Enhanced critical thinking ability” on the other hand implies that case study analysis increased student's ability to think critically and aroused problem-solving interest in the learners. The “Communication and Collaboration” theme implies that case study analysis allowed students to share their views, opinions, and experiences with others and this enabled them to communicate better with others and to respect other's ideas which further enhanced their team building capacities. Conclusion: This method is effective for imparting professional knowledge and skills in undergraduate nursing education and it results in deeper level of learning and helps in the application of theoretical knowledge into clinical practice. It also broadened students’ perspectives, improved their cooperation capacity and their communication with each other. Finally, it enhanced student's judgment and critical thinking skills which is key for their success.

Introduction/Background

Recently, educators started to advocate for teaching modalities that not only transfer knowledge ( Shirani Bidabadi et al., 2016 ), but also foster critical and higher-order thinking and student-centered learning ( Wang & Farmer, 2008 ; Onweh & Akpan, 2014). Therefore, educators need to utilize proven teaching strategies to produce positive outcomes for learners (Onweh & Akpan, 2014). Informed by this view point, a teaching strategy is considered effective if it results in purposeful learning ( Centra, 1993 ; Sajjad, 2010 ) and allows the teacher to create situations that promote appropriate learning (Braskamp & Ory, 1994) to achieve the desired outcome ( Hodges et al., 2020 ). Since teaching methods impact student learning significantly, educators need to continuously test the effectives of their teaching strategies to ensure desired learning outcomes for their students given today's dynamic learning environments ( Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018 ).

In this study, the researchers sought to study the effectiveness of case study analysis as an active, problem-based, student-centered, teacher-facilitated strategy in a baccalaureate-nursing program. This choice of teaching method is supported by the fact that nowadays, active teaching-learning is preferred in undergraduate programs because, they not only make students more powerful actors in professional life ( Bean, 2011 ; Yang et al., 2013 ), but they actually help learners to develop critical thinking skills ( Clarke, 2010 ). In fact, students who undergo such teaching approaches usually become more resourceful in integrating theory with practice, especially as they solve their case scenarios ( Chen et al., 2019 ; Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018 ; Savery, 2019 ).

Review of Literature

As a pedagogical strategy, case studies allow the learner to integrate theory with real-life situations as they devise solutions to the carefully designed scenarios ( Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018 ; Hermens & Clarke, 2009). Another important known observation is that case-study-based teaching exposes students to different cases, decision contexts and the environment to experience teamwork and interpersonal relations as “they learn by doing” thus benefiting from possibilities that traditional lectures hardly create ( Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018 ; Garrison & Kanuka, 2004 ).

Another merit associated with case study method of teaching is the fact that students can apply and test their perspectives and knowledge in line with the tenets of Kolb et al.'s (2014) “experiential learning model”. This model advocates for the use of practical experience as the source of one's learning and development. Proponents of case study-based teaching note that unlike passive lectures where student input is limited, case studies allow them to draw from their own experience leading to the development of higher-order thinking and retention of knowledge.

Case scenario-based teaching also encourages learners to engage in reflective practice as they cooperate with others to solve the cases and share views during case scenario analysis and presentation ( MsDade, 1995 ).

This method results in “idea marriage” as learners articulate their views about the case scenario. This “idea marriage” phenomenon occurs through knowledge transfer from one situation to another as learners analyze scenarios, compare notes with each other, and develop multiple perspectives of the case scenario. In fact, recent evidence shows that authentic case-scenarios help learners to acquire problem solving and collaborative capabilities, including the ability to express their own views firmly and respectfully, which is vital for future success in both professional and personal lives ( Eronen et al., 2019 ; Yajima & Takahashi, 2017 ). In recognition of this higher education trend toward student-focused learning, educators are now increasingly expected to incorporate different strategies in their teaching.

This study demonstrated that when well implemented, educators can use active learning strategies like case study analysis to aid critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaborative capabilities in undergraduate students. This study is significant because the findings will help educators in the country and in the region to incorporate active learning strategies such as case study analysis to aid critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaborative capabilities in undergraduate students. Besides, most studies on the case study method in nursing literature mostly employ quantitative methods. The shortage of published research on the case study method in the Arabian Gulf region and the scanty use of qualitative methods further justify why we adopted the focus group method for inquiry.

A descriptive qualitative research design using focus group discussion method guided the study. The authors chose this method because it is not only inexpensive, flexible, stimulating but it is also known to help with information recall and results in rich data ( Matua et al., 2014 ; Streubert & Carpenter, 2011 ). Furthermore, as evidenced in the literature, the focus group discussion method is often used when there is a need to gain an in-depth understanding of poorly understood phenomena as the case in our study. The choice of this method is further supported by the scarcity of published research related to the use of case study analysis as a teaching strategy in the Middle Eastern region, thereby further justifying the need for an exploratory research approach for our study.

As a recommended strategy, the researchers generated data from information-rich purposively selected group of baccalaureate nursing students who had experienced both traditional lectures and cased-based teaching approaches. The focus group interviews allowed the study participants to express their experiences and perspectives in their own words. In addition, the investigators integrated participants’ self-reported experiences with their own observations and this enhanced the study findings ( Morgan & Bottorff, 2010 ; Nyumba et al., 2018 ; Parker & Tritter, 2006 ).

Eligibility Criteria

In order to be eligible to participate in the study, the participants had to:

- be a baccalaureate nursing student in College of Nursing, Sultan Qaboos University

- register for Maternity Nursing Course in 2017 and 2018.

- attend all the Case Study Analysis sessions in the courses before the study.

- show a willingness to participate in the study voluntarily and share their views freely.

The population included the undergraduate nursing students enrolled in the Maternal Health Nursing Course during the Academic Years 2017 and 2018.

The researcher used a purposive sampling technique to choose participants who were capable of actively participating and discussing their views in the focus group interviews. This technique enabled the researchers to select participants who could provide rich information and insights about case study analysis method as an effective teaching strategy. The final study sample included baccalaureate nursing students who agreed to participate in the study by signing a written informed consent. In total, twenty-two (22) students participated in the study, through five focus groups, with each focus group comprising between four and six students. The number of participants was determined by the stage at which data saturation was reached. The point of data saturation is when no new information emerges from additional participants interviewed ( Saunders et al., 2018 ).Focus group interviews were stopped once data saturation was achieved. Qualitative research design with focus group discussion allowed the researchers to generate data from information-rich purposively selected group of baccalaureate nursing students who had experienced both traditional lectures and case-based teaching approaches. The focus group interviews allowed the study participants to express their perspectives in their own words. In addition, the investigators enhanced the study findings by integrating participants’ self-reported experiences with the researchers’ own observations and notes during the study.

The study took place at College of Nursing; Sultan Qaboos University, Oman's premier public university, in Muscat. This is the only setting chosen for the study. The participants are the students who were enrolled in Maternal Health Nursing course during 2017 and 2018. The interviews occurred in the teaching rooms after official class hours. Students who did not participate in the study learnt the course content using the traditional lecture based method.

Ethical Considerations

Permission to conduct the study was granted by the College Research and Ethics Committee (XXXX). Prior to the interviews, each participant was informed about the purpose, benefits as well as the risks associated with participating in the study and clarifications were made by the principal researcher. After completing this ethical requirement, each student who accepted to participate in the study proceeded to sign an informed consent form signifying that their participation in the focus group interview was entirely voluntary and based on free will.

The anonymity of study participants and confidentiality of their data was upheld throughout the focus group interviews and during data analysis. To enhance confidentiality and anonymity of the data, each participant was assigned a unique code number which was used throughout data analysis and reporting phases. To further assure the confidentiality of the research data and anonymity of the participants, all research-related data were kept safe, under lock and key and through digital password protection, with unhindered access only available to the research team.

Research Intervention

In Fall 2017 and Spring 2018 semesters, as a method of teaching Maternal Health Nursing course, all students participated in two group-based case study analysis exercises which were implemented in the 7 th and 13 th weeks. This was done after the students were introduced to the case study method using a sample case study prior to the study. The instructor explained to the students how to solve the sample problem, including how to accomplish the role-specific competencies in the courses through case study analysis. In both weeks, each group consisting of six to seven students was assigned to different case scenarios to analyze and work on, after which they presented their collective solution to the case scenarios to the larger class of 40 students. The case scenarios used in both weeks were peer-reviewed by the researchers prior to the study.

Pilot Study

A group of three students participated as a pilot group for the study. However, the students who participated in the pilot study were not included in the final study as is general the principle with qualitative inquiry because of possible prior exposure “contamination”. The purpose of piloting was to gather data to provide guidance for a substantive study focusing on testing the data collection procedure, the interview process including the sequence and number of questions and probes and recording equipment efficacy. After the pilot phase, the lessons learned from the pilot were incorporated to ensure smooth operations during the actual focus group interview ( Malmqvist et al., 2019 .

Data Collection

The focus group interviews took place after the target population was exposed to case study analysis method in Maternal Health Nursing course during the Fall 2017 and Spring 2018 semesters. Before data collection began, the research team pilot tested the focus group interview guide to ensure that all the guide questions were clear and well understood by study participants.

In total, five (5) focus groups participated in the study, with each group comprising between four and six students. The focus group interviews lasted between 60 and 90 min. In addition to the interview guide questions, participants’ responses to unanswered questions were elicited using prompts to facilitate information flow whenever required. As a best practice, all the interviews were audio-recorded in addition to extensive field notes taken by one of the researchers. The focus group interviews continued until data saturation occurred in all the five (5) focus groups.

Credibility

In this study, participant's descriptions were digitally audio recorded to ensure that no information was lost. In order to ensure that the results are accurate, verbatim transcriptions of the audio recordings were done supported by interview notes. Furthermore, interpretations of the researcher were verified and supported with existing literature with oversight from the research team.

Transferability

The researcher provided a detailed description about the study settings, participants, sampling technique, and the process of data collection and analyses. The researcher used verbatim quotes from various participants to aid the transferability of the results.

Dependability

The researcher ensured that the research process is clearly documented, traceable, and logical to achieve dependability of the research findings. Furthermore, the researcher transparently described the research steps, procedures and process from the start of the research project to the reporting of the findings.

Confirmability

In this study, confirmability of the study findings was achieved through the researcher's efforts to make the findings credible, dependable, and transferable.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed manually after the lead researcher integrated the verbatim transcriptions with the extensive field notes to form the final data set. Data were analyzed thematically under three thematic areas of a) knowledge development; b) critical thinking and problem solving; and (c) communication and collaboration, which are linked to the study objectives. The researchers used the Six (6) steps approach to conduct a trustworthy thematic analysis: (1) familiarization with the research data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing the themes, (5) defining and naming themes, (6) writing the report ( Nowell et al., 2017 ).

The analysis process started with each team member individually reading and re-reading the transcripts several times and then identifying meaning units linked to the three thematic areas. The co-authors then discussed in-depth the various meaning units linked to the thematic statements until consensus was reached and final themes emerged based on the study objectives.

A total of 22 undergraduate third-year baccalaureate nursing students who were enrolled in the Maternal Health Nursing Course during the Academic Years 2017 and 2018 participated in the study, through five focus groups, with each group comprising four to six students. Of these, 59% were females and 41% were males. In total, nine subthemes emerged from the three themes. Under knowledge development, emerged the subthemes, “ deepened understanding of content ; “ reduced gap between theory and practice” and “ improved test-taking ability ”. While under Critical thinking and problem solving, emerged the subthemes, “ enhanced critical thinking ability ” and “ heightened curiosity”. The third thematic area of communication and collaboration yielded, “ improved communication ability ”; “ enhanced team-building capacity ”; “ effective collaboration” and “ improved presentation skills ”, details of which are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Objective Linked Themes and Student Perceptions of Outcome Case Study Analysis.

Theme 1: Knowledge Development

In terms of knowledge development, students expressed delight at the inclusion of case study analysis as a method during their regular theory class. The first subtheme related to knowledge development that supports the adoption of the case study approach is its perceived benefit of ‘ deepened understanding of content ’ by the students as vividly described by this participant:

“ I was able to perform well in the in-course exams as this teaching method enhanced my understanding of the content rather than memorizing ” (FGD#3).

The second subtheme related to knowledge development was informed by participants’ observation that teaching them using case study analysis method ‘ reduced the gap between theory and practice’. This participant's claim stem from the realization that, a case study scenario his group analyzed in the previous week helped him and his colleagues to competently deal with a similar situation during clinical placement the following week, as articulated below:

“ You see when I was caring for mothers in antenatal unit, I could understand the condition better and could plan her care well because me and my group already analyzed a similar situation in class last week which the teacher gave us, this made our work easier in the ward”. (FGD#7).

Another student added that:

“ It was useful as what is taught in the theory class could be applied to the clinical cases.”

This ‘theory-practice’ connection was particularly useful in helping students to better understand how to manage patients with different health conditions. Interestingly, the students reported that they were more likely to link a correct nursing care plan to patients whose conditions were close to the case study scenarios they had already studied in class as herein affirmed:

“ …when in the hospital I felt I could perceive the treatment modality and plan for [a particular] nursing care well when I [had] discussed with my team members and referred the textbook resource while performing case study discussion”. (FGD#17).

In a similar way, another student added:

“…I could relate with the condition I have seen in the clinical area. So this has given me a chance to recall the condition and relate the theory to practice”. (FGD#2) .

The other subtheme closely related to case study scenarios as helping to deepen participant's understanding of the course content, is the notion that this teaching strategy also resulted in ‘ improved test taking-ability’ as this participant's verbatim statement confirms:

“ I could answer the questions related to the cases discussed [much] better during in-course exams. Also [the case scenarios] helped me a great deal to critically think and answer my exam papers” (FGD#11).

Theme 2: Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

In this subtheme, students found the case study analysis as an excellent method to learn disease conditions in the two courses. This perceived success with the case study approach is associated with the method's ability to ‘ enhance students’ critical thinking ability’ as this student declares:

“ This method of teaching increased my ability to think critically as the cases are the situations, where we need to think to solve the situation”. (FGD#5)

This enhanced critical thinking ability attributed to case study scenario analysis was also manifested during patient care where students felt it allowed them to experience a “ flow of patient care” leading to better patient management planning as would typically occur during case scenario analysis. In support of this finding, a participant mentioned that:

“ …I could easily connect the flow of patient care provided and hence was able to plan for [his] management as often required during case study discussion” (FGD#12)

Another subtheme linked with this theme is the “ heightened curiosity” associated with the case scenario discussions. It was clear from the findings that the cases aroused curiosity in the mind of the students. This heightened interest meant that during class discussion, baccalaureate nursing students became active learners, eager to discover the next set of action as herein affirmed:

“… from the beginning of discussion with the group, I was eager to find the answer to questions presented and wanted to learn the best way for patient management” (FGD#14)

Theme 3: Communication and Collaboration

In terms of its impact on student communication, the subtheme revealed that case study analysis resulted in “ improved communication ability” among the nursing students . This enhanced ability of students to exchange ideas with each other may be attributed to the close interaction required to discuss and solve their assigned case scenarios as described by the participant below:

“ as [case study analysis] was done in the way of group discussion, I felt me and my friends communicated more within the group as we discussed our condition. We also learnt from each other, and we became better with time.” (FGD#21).

The next subtheme further augments the notion that case study analysis activities helped to “ enhance team-building capacity” of students as this participant affirmatively narrates:

“ students have the opportunity to meet face to face to share their views, opinion, and their experience, as this build on the way they can communicate with each other and respect each other's opinions and enhance team-building”. (FGD#19).

Another subtheme revealed from the findings show that the small groups in which the case analysis occurs allowed the learners to have deeper and more focused conversations with one another, resulting in “ an effective collaboration between students” as herein declared:

“ We could collaborate effectively as we further went into a deep conversation on the case to solve”. (FGD#16).

Similarly, another student noted that:

“ …discussion of case scenarios helped us to prepare better for clinical postings and simulation lab experience” (FGD#5) .

A fourth subtheme related to communication found that students also identified that case study analysis resulted in “ improved presentation skills”. This is attributed in part to the preparation students have to go through as part of their routine case study discussion activities, which include organizing their presentations and justifying and integrating their ideas. Besides readying themselves for case presentations, the advice, motivation, and encouragement such students receive from their faculty members and colleagues makes them better presenters as confirmed below:

“ …teachers gave us enough time to prepare, hence I was able to present in front of the class regarding the finding from our group.” (FGD#16).

In this study, the researches explored learner's perspectives on how one of the active teaching strategies, case study analysis method impacted their knowledge development, critical thinking, and problem solving as well as communication and collaboration ability.

Knowledge Development

In terms of knowledge development, the nursing students perceived case study analysis as contributing toward: (a) deeper understanding of content, (b) reducing gap between theory and practice, and (c) improving test-taking ability. Deeper learning” implies better grasping and retention of course content. It may also imply a deeper understanding of course content combined with learner's ability to apply that understanding to new problems including grasping core competencies expected in future practice situations (Rickles et al., 2019; Rittle-Johnson et al., 2020 ). Deeper learning therefore occurs due to the disequilibrium created by the case scenario, which is usually different from what the learner already knows ( Hattie, 2017 ). Hence, by “forcing” students to compare and discuss various options in the quest to solve the “imbalance” embedded in case scenarios, students dig deeper in their current understanding of a given content including its application to the broader context ( Manalo, 2019 ). This movement to a deeper level of understanding arises from carefully crafted case scenarios that instructors use to stimulate learning in the desired area (Nottingham, 2017; Rittle-Johnson et al., 2020 ). The present study demonstrated that indeed such carefully crafted case study scenarios did encourage students to engage more deeply with course content. This finding supports the call by educators to adopt case study as an effective strategy.

Another finding that case study analysis method helps in “ reducing the gap between theory and practice ” implies that the method helps students to maintain a proper balance between theory and practice, where they can see how theoretical knowledge has direct practical application in the clinical area. Ajani and Moez (2011) argue that to enable students to link theory and practice effectively, nurse educators should introduce them to different aspects of knowledge and practice as with case study analysis. This dual exposure ensures that students are proficient in theory and clinical skills. This finding further amplifies the call for educators to adequately prepare students to match the demands and realities of modern clinical environments ( Hickey, 2010 ). This expectation can be met by ensuring that student's knowledge and skills that are congruent with hospital requirements ( Factor et al., 2017 ) through adoption of case study analysis method which allows integration of clinical knowledge in classroom discussion on regular basis.

The third finding, related to “improved test taking ability”, implies that case study analysis helped them to perform better in their examination, noting that their experience of going through case scenario analysis helped them to answer similar cases discussed in class much better during examinations. Martinez-Rodrigo et al. (2017) report similar findings in a study conducted among Spanish electrical engineering students who were introduced to problem-based cooperative learning strategies, which is similar to case study analysis method. Analysis of student's results showed that their grades and pass rates increased considerably compared to previous years where traditional lecture-based method was used. Similar results were reported by Bonney (2015) in an even earlier study conducted among biology students in Kings Borough community college students, in New York, United States. When student's performance in examination questions covered by case studies was compared with class-room discussions, and text-book reading, case study analysis approach was significantly more effective compared to traditional methods in aiding students’ performance in their examinations. This finding therefore further demonstrates that case study analysis method indeed improves student's test taking ability.

Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

In terms of critical thinking and problem-solving ability, the use of case study analysis resulted in two subthemes: (a) enhanced critical thinking ability and (b) heightened learner curiosity. The “ enhanced critical thinking ability” implies that case analysis increased student's ability to think critically as they navigated through the case scenarios. This observation agrees with the findings of an earlier questionnaire-based study conducted among 145 undergraduate business administration students at Chittagong University, Bangladesh, that showed 81% of respondents agree that case study analysis develops critical thinking ability and enables students to do better problem analysis ( Muhiuddin & Jahan, 2006 ). This observation agrees with the findings of an earlier study conducted among 145 undergraduate business administration students at Chittagong University, Bangladesh. The study showed that 81% of respondents agreed that case study analysis facilitated the development of critical thinking ability in the learners and enabled the students to perform better with problem analysis ( Muhiuddin & Jahan, 2006 ).

More recently, Suwono et al. (2017) found similar results in a quasi-experimental research conducted at a Malaysian university. The research findings showed that there was a significant difference in biological literacy and critical thinking skills between the students taught using socio-biological case-based learning and those taught using traditional lecture-based learning. The researchers concluded that case-based learning enhanced the biological literacy and critical thinking skills of the students. The current study adds to the existing pedagogical knowledge base that case study methodology can indeed help to deepen learner's critical thinking and problem solving ability.

The second subtheme related to “ heightened learner curiosity” seems to suggest that the case studies aroused problem-solving interest in learners. This observation agrees with two earlier studies by Tiwari et al. (2006) and Flanagan and McCausland (2007) who both reported that most students enjoyed case-based teaching. The authors add that the case study method also improved student's clinical reasoning, diagnostic interpretation of patient information as well as their ability to think logically when presented a challenge in the classroom and in the clinical area. Jackson and Ward (2012) similarly reported that first year engineering undergraduates experienced enhanced student motivation. The findings also revealed that the students venturing self-efficacy increased much like their awareness of the importance of key aspects of the course for their future careers. The authors conclude that the case-based method appears to motivate students to autonomously gather, analyze and present data to solve a given case. The researchers observed enhanced personal and collaborative efforts among the learners, including improved communication ability. Further still, learners were more willing to challenge conventional wisdom, and showed higher “softer” skills after exposure to case analysis based teaching method. These findings like that of the current study indicate that teaching using case based analysis approach indeed motivates students to engage more in their learning, there by resulting in deeper learning.

Communication and Collaboration

Case study analysis is also perceived to result in: (a) improved communication ability; (b) enhanced team -building capacity, (c) effective collaboration ability, and (d) enhanced presentation skills. The “ improved communication ability ” manifested in learners being better able to exchange ideas with peers, communicating their views more clearly and collaborating more effectively with their colleagues to address any challenges that arise. Fini et al. (2018) report comparable results in a study involving engineering students who were subjected to case scenario brainstorming activities about sustainability concepts and their implications in transportation engineering in selected courses. The results show that this intervention significantly improved student's communication skills besides their higher-order cognitive, self-efficacy and teamwork skills. The researchers concluded that involving students in brainstorming activities related to problem identification including their practical implications, is an effective teaching strategy. Similarly, a Korean study by Park and Choi (2018) that sought to analyze the effects of case-based communication training involving 112 sophomore nursing students concluded that case-based training program improved the students’ critical thinking ability and communication competence. This finding seems to support further the use of case based teaching as an effective teaching-learning strategy.

The “ enhanced team-building capacity” arose from the opportunity students had in sharing their views, opinions, and experiences where they learned to communicate with each other and respect each other's ideas which further enhance team building. Fini et al. (2018) similarly noted that increased teamwork levels were seen among their study respondents when the researchers subjected engineering students to case scenario based-brainstorming activities as occurs with case study analysis teaching. Likewise, Lairamore et al. (2013) report similar results in their study that showed that case study analysis method increased team work ability and readiness among students from five health disciplines in a US-based study.

The finding that case study analysis teaching method resulted in “ effective collaboration ability” among students manifested as students entered into deep conversation as they solved the case scenarios. Rezaee and Mosalanejad (2015) assert that such innovative learning strategies result in noticeable educational outcomes, such as greater satisfaction with and enjoyment of the learning process ( Wellmon et al., 2012 ). Further, positive attitudes toward learning and collaboration have been noted leading to deeper learning as students prepare for case discussions ( Rezaee & Mosalanejad, 2015 ). This results show that case study analysis can be utilized by educators to foster professional collaboration among their learners, which is one of the key expectations of new graduates today.

The finding associated with “improved presentation skills” is consistent with the results of a descriptive study in Saudi Arabia that compared case study and traditional lectures in the teaching of physiology course to undergraduate nursing students. The researchers found that case-based teaching improved student’ overall knowledge and performance in the course including facilitating the acquisition of skills compared to traditional lectures ( Majeed, 2014 ). Noblitt et al. (2010) report similar findings in their study that compares traditional presentation approach with the case study method for developing and improving student's oral communication skills. This finding extends our understanding that case study method improves learners’ presentation skills.

The study was limited to level third year nursing students belonging to only one college and the sample size, which might limit the transferability of the study findings to other settings.

Implications for Practice

These study findings add to the existing body of knowledge that places case study based teaching as a tested method that promotes perception learning where students’ senses are engaged as a result of the real-life and authentic clinical scenarios ( Malesela, 2009 ), resulting in deeper learning and achievement of long-lasting knowledge ( Fiscus, 2018 ). The students reported that case scenario discussions broadened their perspectives, improved their cooperation capacity and communication with each other. This teaching method, in turn, offers students an opportunity to enhance their judgment and critical thinking skills by applying theory into practice.

These skills are critically important because nurses need to have the necessary knowledge and skills to plan high quality care for their patients to achieve a speedy recovery. In order to attain this educational goal, nurse educators have to prepare students through different student- centered strategies. The findings of our study appear to show that when appropriately used, case-based teaching results in acquisition of disciplinary knowledge manifested by deepened understanding of course content, as well as reducing the gap between theory and practice and enhancing learner's test-taking-ability. The study also showed that cased based teaching enhanced learner's critical thinking ability and curiosity to seek and acquire a deeper knowledge. Finally, the study results indicate that case study analysis results in improved communication and enhanced team-building capacity, collaborative ability and improved oral communication and presentation skills. The study findings and related evidence from literature show that case study analysis is well- suited approach for imparting knowledge and skills in baccalaureate nursing education.

This study evaluated the usefulness of Case Study Analysis as a teaching strategy. We found that this method of teaching helps encourages deeper learning among students. For instructors, it provides the opportunity to tailor learning experiences for students to undertake in depth study in order to stimulate deeper understanding of the desired content. The researchers conclude that if the cases are carefully selected according to the level of the students, and are written realistically and creatively and the group discussions keep students well engaged, case study analysis method is more effective than other traditional lecture methods in facilitating deeper and transferable learning/skills acquisition in undergraduate courses.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ORCID iD: Judie Arulappan https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2788-2755

- Ajani K., Moez S. (2011). Gap between knowledge and practice in nursing . Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences , 15 , 3927–3931. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.396 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bean J. C. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing critical thinking and active-learning in the classroom (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bonney K. M. (2015). Case study teaching method improves student performance and perceptions of learning gains . Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 ( 1 ), 21–28. 10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Braskamp L. A., Ory J. C. (1994). Assessing faculty work: Enhancing individual and institutional performance . Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. Jossey-Bass Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Centra J. A. (1993). Reflective faculty evaluation: Enhancing teaching and determining faculty effectiveness . Jossey-Bass. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen W., Shah U. V., Brechtelsbauer C. (2019). A framework for hands-on learning in chemical engineering education—training students with the end goal in mind . Education for Chemical Engineers , 28 , 25–29. 10.1016/j.ece.2019.03.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clarke J. (2010). Student centered teaching methods in a Chinese setting . Nurse Education Today , 30 ( 1 ), 15–19. 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.05.009 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eronen L., Kokko S., Sormunen K. (2019). Escaping the subject-based class: A Finnish case study of developing transversal competencies in a transdisciplinary course . The Curriculum Journal , 30 ( 3 ), 264–278. 10.1080/09585176.2019.1568271 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Factor E. M. R., Matienzo E. T., de Guzman A. B. (2017). A square peg in a round hole: Theory-practice gap from the lens of Filipino student nurses . Nurse Education Today , 57 , 82–87. 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.07.004 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Farashahi M., Tajeddin M. (2018). Effectiveness of teaching methods in business education: A comparison study on the learning outcomes of lectures, case studies and simulations . The International Journal of Management Education , 16 ( 1 ), 131–142. 10.1016/j.ijme.2018.01.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fini E. H., Awadallah F., Parast M. M., Abu-Lebdeh T. (2018). The impact of project-based learning on improving student learning outcomes of sustainability concepts in transportation engineering courses . European Journal of Engineering Education , 43 ( 3 ), 473–488. 10.1080/03043797.2017.1393045 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fiscus J. (2018). Reflection in Motion: A Case Study of Reflective Practice in the Composition Classroom [ Doctoral dissertation ]. Source: http://hdl.handle.net/1773/42299 [ Google Scholar ]

- Flanagan N. A., McCausland L. (2007). Teaching around the cycle: Strategies for teaching theory to undergraduate nursing students . Nursing Education Perspectives , 28 ( 6 ), 310–314. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garrison D. R., Kanuka H. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education . The internet and higher education , 7 ( 2 ), 95–105. 10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.02.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hattie J. (2017). Foreword . In Nottingham J. (Ed.), The learning challenge: How to guide your students through the learning pit to achieve deeper understanding . Corwin Press, p. xvii. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hermens A., Clarke E. (2009). Integrating blended teaching and learning to enhance graduate attributes . Education+ Training , 51 ( 5/6 ), 476–490. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hickey M. T. (2010). Baccalaureate nursing graduates’ perceptions of their clinical instructional experiences and preparation for practice . Journal of Professional Nursing , 26 ( 1 ), 35–41. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2009.03.001 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hodges C., Moore S., Lockee B., Trust T., Bond A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning . Educause review , 27 , 1–12. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jackson N. R., Ward A. E. (2012). Curiosity based learning: Impact study in 1st year electronics undergraduates. 2012 International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET), Istanbul, pp. 1–6. 10.1109/ITHET.2012.6246005. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kolb A. Y., Kolb D. A., Passarelli A., Sharma G. (2014). On becoming an experiential educator: The educator role profile . Simulation & Gaming , 45 ( 2 ), 204–234. 10.1177/1046878114534383 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lairamore C., George-Paschal L., McCullough K., Grantham M., Head D. (2013). A case-based interprofessional education forum improves students’ perspectives on the need for collaboration, teamwork, and communication . MedEdPORTAL, The Journal of Teaching and learning resources , 9 , 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9484 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Majeed F. (2014). Effectiveness of case based teaching of physiology for nursing students . Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences , 9 ( 4 ), 289–292. 10.1016/j.jtumed.2013.12.005 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Malesela J. M. (2009). Case study as a learning opportunity among nursing students in a university . Health SA Gesondheid (Online) , 14 ( 1 ), 33–38. 10.4102/hsag.v14i1.434 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Malmqvist J., Hellberg K., Möllås G., Rose R., Shevlin M. (2019). Conducting the pilot study: A neglected part of the research process? Methodological findings supporting the importance of piloting in qualitative research studies . International Journal of Qualitative Methods , 18 . 10.1177/1609406919878341 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Manalo E. (ed.). (2019). Deeper learning, dialogic learning, and critical thinking: Research-based strategies for the classroom . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martinez-Rodrigo F., Herrero-De Lucas L. C., De Pablo S., Rey-Boue A. B. (2017). Using PBL to improve educational outcomes and student satisfaction in the teaching of DC/DC and DC/AC converters . IEEE Transactions on Education , 60 ( 3 ), 229–237. 10.1109/TE.2016.2643623 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Matua G. A., Seshan V., Akintola A. A., Thanka A. N. (2014). Strategies for providing effective feedback during preceptorship: Perspectives from an Omani Hospital . Journal of Nursing Education and Practice , 4 ( 10 ), 24. 10.5430/jnep.v4n10p24 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan D. L., Bottorff J. L. (2010). Advancing our craft: Focus group methods and practice . Qualitative Health Research , 20 ( 5 ), 579–581. 10.1177/1049732310364625 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MsDade S. A. (1995). Case study pedagogy to advance critical thinking . Teaching psychology , 22 ( 1 ), 9–10. 10.1207/s15328023top2201_3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muhiuddin G., Jahan N. (2006). Students’ perception towards case study as a method of learning in the field of business administration’ . The Chittagong University Journal of Business Administration , 21 , 25–41. [ Google Scholar ]

- Noblitt L., Vance D. E., Smith M. L. D. (2010). A comparison of case study and traditional teaching methods for improvement of oral communication and critical-thinking skills . Journal of College Science Teaching , 39 ( 5 ), 26–32. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nottingham J. (2017). The learning challenge: How to guide your students through the learning pit to achieve deeper understanding . Corwin Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nowell L. S., Norris J. M., White D. E., Moules N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria . International Journal of Qualitative Methods , 16 ( 1 ). 10.1177/1609406917733847 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nyumba T., Wilson K., Derrick C. J., Mukherjee N. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation . Methods in Ecology and evolution , 9 ( 1 ), 20–32. 10.1111/2041-210X.12860 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Onweh V. E., Akpan U. T. (2014). Instructional strategies and students academic performance in electrical installation in technical colleges in Akwa Ibom State: Instructional skills for structuring appropriate learning experiences for students . International Journal of Educational Administration and Policy Studies , 6 ( 5 ), 80–86. [ Google Scholar ]

- Park S. J., Choi H. S. (2018). The effect of case-based SBAR communication training program on critical thinking disposition, communication self-efficacy and communication competence of nursing students . Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society , 19 ( 11 ), 426–434. 10.5762/KAIS.2018.19.11.426 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parker A., Tritter J. (2006). Focus group method and methodology: Current practice and recent debate . International Journal of Research & Method in Education , 29 ( 1 ), 23–37. 10.1080/01406720500537304 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rezaee R., Mosalanejad L. (2015). The effects of case-based team learning on students’ learning, self-regulation and self-direction . Global Journal of Health Science , 7 ( 4 ), 295. 10.5539/gjhs.v7n4p295 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rickles J., Zeiser K. L., Yang R., O’Day J., Garet M. S. (2019). Promoting deeper learning in high school: Evidence of opportunities and outcomes . Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis , 41 ( 2 ), 214–234. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rittle-Johnson B., Star J. R., Durkin K., Loehr A. (2020). Compare and discuss to promote deeper learning. Deeper learning, dialogic learning, and critical thinking: Research-based strategies for the classroom . Routlegde, p. 48. 10.4324/9780429323058-4 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sajjad S. (2010). Effective teaching methods at higher education level . Pakistan Journal of Special Education , 11 , 29–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- Saunders B., Sim J., Kingstone T., Baker S., Waterfield J., Bartlam B., Burroughs H., Jinks C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization . Quality & Quantity , 52 ( 4 ), 1893–1907. 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Savery J. R. (2019). Comparative pedagogical models of problem based learning . The Wiley Handbook of Problem Based Learning , 81–104. 10.1002/9781119173243.ch4 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shirani Bidabadi N., Nasr Isfahani A., Rouhollahi A., Khalili R. (2016). Effective teaching methods in higher education: Requirements and barriers . Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism , 4 ( 4 ), 170–178. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Streubert H. J., Carpenter D. R. (2011). Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative . Wolters Kluwer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Suwono H., Pratiwi H. E., Susanto H., Susilo H. (2017). Enhancement of students’ biological literacy and critical thinking of biology through socio-biological case-based learning . JurnalPendidikan IPA Indonesia , 6 ( 2 ), 213–220. 10.15294/jpii.v6i2.9622 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tiwari A., Lai P., So M., Yuen K. (2006). A comparison of the effects of problem-based learning and lecturing on the development of students’ critical thinking . Medical Education , 40 ( 6 ), 547–554. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02481.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang V., Farmer L. (2008). Adult teaching methods in China and bloom's taxonomy . International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning , 2 ( 2 ), n2. 10.20429/ijsotl.2008 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wellmon R., Gilin B., Knauss L., Linn M. I. (2012). Changes in student attitudes toward interprofessional learning and collaboration arising from a case-based educational experience . Journal of Allied Health , 41 ( 1 ), 26–34. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yajima K., Takahashi S. (2017). Development of evaluation system of AL students . Procedia Computer Science , 112 , 1388–1395. 10.1016/j.procs.2017.08.056 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yang W. P., Chao C. S. C., Lai W. S., Chen C. H., Shih Y. L., Chiu G. L. (2013). Building a bridge for nursing education and clinical care in Taiwan—using action research and confucian tradition to close the gap . Nurse Education Today , 33 ( 3 ), 199–204. 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.02.016 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Educators’ perceptions of technology integration into the classroom: a descriptive case study

Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning

ISSN : 2397-7604

Article publication date: 14 June 2019

Issue publication date: 3 December 2019

The purpose of this paper is to supply an in-depth description of the educators’ values, beliefs and confidence changing from a traditional learning environment to a learning environment integrating technology.

Design/methodology/approach

The descriptive case study design was employed using descriptive statistical analysis and inductive analysis on the data collected.

Themes on a high level of confidence, the importance of professional development and training, self-motivation, and excitement about the way technology can enhance the learning, along with concerns over the lack of infrastructure and support for integrating technology, and about the ability of students to use the technology tools for higher ordered thinking surfaced.

Research limitations/implications

Additional research may include a more diverse population, including educators at the kindergarten to high school level. Another recommendation would be to repeat the study with a population not as vested in technology.

Practical implications

A pre-assessment of the existing values, beliefs and confidence of educators involved in the change process will provide invaluable information for stakeholders on techniques and strategies vital to a successful transition.

Social implications

To effectively meet the learning styles of Generation Z and those students following, educators need be able to adapt to quickly changing technology, be comfortable with students who multitask and be open to technology-rich teaching and learning environments.

Originality/value

This study filled a gap in the literature where little information on the humanistic challenges educators encounter when integrating technology into their learning environment providing insights into the values, beliefs and level of confidence of educators experiencing change.

- Educational technology

- Humanistic approach

- Integrating technology

Hartman, R.J. , Townsend, M.B. and Jackson, M. (2019), "Educators’ perceptions of technology integration into the classroom: a descriptive case study", Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning , Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 236-249. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-03-2019-0044

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Rita J. Hartman, Mary B. Townsend and Marlo Jackson

Published in Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

How students prefer to learn has changed dramatically since the introduction of the internet. Students no long prefer passive dissemination of information being delivered by a teacher. Students prefer to watch a task taking place, and then attempt to duplicate it instead of reading or being instructed about the topic ( Genota, 2018 ; Seemiller and Grace, 2017 ; Shatto and Erwin, 2017 ; Swanzen, 2018 ). For example, 59 percent of Generation Z, 14–23-year olds, access YouTube for learning and information, 55 percent believe YouTube contributed to their education and only 47 percent prefer textbooks as a learning tool ( Global Research and Insights, 2018 ). The findings indicate virtual applications integrated into the curriculum can enhance the cognitive and creative skills of students through a student-centered environment ( Steele et al. , 2019 ). Although the study indicated 78 percent of the Generation Z believed teachers were important to their learning, only 39 percent preferred teacher-led instruction.

During the last seven years, the number of technology devices has grown 363 percent in our public schools. However, the use of classroom computers that duplicate the passive pedagogy of traditional classrooms has become more common, and the percentage of educational professional development opportunities for technology integration has remained unchanged ( Genota, 2018 ). Most college courses, even those that use a learning management system (LMS), tend to be teacher centered and lecture based ( Vercellotti, 2018 ). Higher education tends to be slow at adopting innovations in part because of the risk and the time commitment involved in exploring new tools and ideas ( Serdyukov, 2017 ). Simply adding more devices into the classroom is not enough to change instructional practices.

To effectively meet the learning styles of Generation Z and those students following, educators need be able to adapt to quickly changing technology, be comfortable with students who multitask and be open to technology-rich teaching and learning environments. However, most educators do not have the adequate knowledge, skills and confidence to effectively or efficiently use the available technologies to support technology integration into the learning environment ( El Fadil, 2015 ; Ferdig and Kennedy, 2014 ; Somera, 2018 ). In order to generate a systemic and empathetic change that can be sustained over time, educational leaders would need to explore the humanistic aspect of the change process as experienced by the educators. Inherent in the shifting role of educators is an in-depth understanding of the values, beliefs and confidence educators bring to the integration of technology into their classrooms.

Accessing information

The creation of the internet in 1990 by Tim Berners Lee ( Patterson, 1999 ) greatly influenced how people accessed information, interacted socially and prefer to learn. Generation Z (those born between 1995 and 2010) have grown up with easy access to the internet and are accustomed to multitasking, accessing information with a few clicks and watching something being done before trying it themselves ( Seemiller and Grace, 2017 ). Generation Z students prefer working with peers in collaborative groups over lectures. These students desire active learning with demonstrations and hands-on participation ( Adamson et al. , 2018 ; Seemiller and Grace, 2016 ). The students are also known by the monikers Net Generation, iGeneration or digital natives. By the year 2020, digital natives will make up one-third of the population in the USA ( Seemiller and Grace, 2016 ). Technology is a dominant part of their existence.

The traditional educational setting no longer meets the needs of a generation of students who strive to design their own learning experience ( Office of Educational Technology, Department of Education, 2017 ). However, the change from a teacher-centered learning environment to a student-centered learning environment with the integration of technology creates challenges and creates opportunities for educators ( Nicol et al. , 2018 ). Some educators recognize the benefits of integrating technology into their classrooms, which includes the advantages over traditional teaching and additional opportunities for improving student learning. Educators also consider benefits such as the availability of equipment, ease of use and the interest the technology may spark in each student ( Porter and Graham, 2016 ).

The process of identifying and implementing instructional technology requires different levels of support. The transition from a traditional learning environment to a learning environment integrating technology requires a certain amount of self-education on the part of the instructor, and the change process may take years ( Nicol et al. , 2018 ). Some educators find the process of scheduling equipment and loading materials into online course shells frustrating, and others find professional development activities do not fulfill their needs. The professional development available to faculty may have the wrong instructional focus, may be the wrong type or format, or may not be at the appropriate instructional level of the learners involved ( Reid, 2017 ). Achieving the level of support required for educators to feel comfortable may be challenging to both the support staff and the educators.

Change process

Learning how to enhance teaching with technology can be difficult ( Reid, 2017 ). Some educators approach instruction with very traditional methods. Teacher-centered lectures, pages of notes and assigned readings represent traditional or old-school instructional practices. Few post-secondary instructors are taught how to teach and most learn by modeling the teaching style of others. Teachers have not been taught how to be a facilitator in a technology-rich classroom ( Nicol et al. , 2018 ). Those teachers who do not acknowledge the changes in learning preferences may find it more difficult to teach the new generation.

Not all educators have the ability to embrace change. They may approach change with a fixed-mindset attempting to use a new technology tool and giving up easily at the first sign of difficulty. They do not see themselves as capable of learning to use the new technology tools and fear the risk of failure when trying new things ( Dress, 2016 ). The transition from teacher centered to student centered is a significant change and may be seen as a relinquishment of control by the teacher. Educators who are most comfortable in a traditional approach to education need more support when changing to a student-centered approach.

Humanistic influence on technology integration

The humanistic approach is described as involving the whole person and is manifested in the values, beliefs, confidence and emotions of the individual ( Fedorenko, 2018 ). Teaching is a humanistic endeavor, and educators find joy in being able to interact with their students and in being able to share their knowledge directly ( Azzaro, 2014 ). Learning organizations need educators who can bridge the gap between human and technological cultures ( Dominici, 2018 ). However, changing from a teacher-centered approach to a student-centered approach to instruction and learning may be difficult, and requiring the use of technology may seem too impersonal for educators to accept.

The educators’ values, beliefs and level of confidence are factors in the adoption of new technologies and pedagogies. A positive attitude toward using technology was found to be a significant factor in the intention to use educational technology. Positive attitudes have a major influence on the acceptance or rejection of the new technology integration. The change may come in the form of an educational change initiated by the college or university.

An educator’s beliefs about using technology become a factor in the ability to adopt the new technology into their pedagogy. If the transition was smooth and the process was positive, educators may be more open to accepting the change. If the change was not positive, the announcement may produce negative feelings and doubt related to any new initiative. The change may produce resistance, self-doubt and uncertainties ( Kilinc et al. , 2017 ; Reid, 2017 ). The doubt causes them to question the change and their belief system. Past experiences may also influence educators’ ability to be successful with the implementation of a new innovation, such as technology ( Demirbağ and Kılınç, 2018 ; Reid, 2017 ). If the focus of the change contradicts the current belief system, teachers are less likely to put the reforms into practice; therefore, they become resistant to the change. Changes that align with core beliefs are more likely to be successful ( Demirbağ and Kılınç, 2018 ). The alignment allows teachers to feel confident about the change process and more likely to be a user of technology.

Educators produce resistance by using the technology superficially or not at all. The resistance builds when the educational technology seemingly does not contribute to their traditional teaching ( Demirbağ and Kılınç, 2018 ). Educators may perceive learning to use the newly adopted technology as a burden ( Cheung et al. , 2018 ). The educational technology may be meaningful, but the resistance prevents them from exploring further opportunities for using the technology.

Resistance to technology can also be in association with an educator’s efficacy. Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s own ability to succeed in a context-specific task or behavior ( Bandura, 1986 ; Alenezi, 2017 ). Confidence and knowledge with using technology and computers is known as computer self-efficacy (CSE). CSE refers to the ability and the application of skills to achieve a result ( Alshammari et al. , 2016 ). The importance of CSE increased since the implementation of computer-based learning at all educational levels ( Bhatiasevi and Naglis, 2016 ). Educators with limited exposure to technology in their everyday and personal lives or with limited or nonexistent support will be resistant to using technology ( Kilinc et al. , 2017 ). An educator who demonstrates higher levels of CSE will have less frustration and will increase their use of technology in the future ( Cheung et al. , 2018 ). Users of technology tend to believe in the value of technology if it is easy to use and makes completing tasks simpler ( Bhatiasevi and Naglis, 2016 ). Lower levels of CSE coincide with low motivation and the perception of the technology as difficult and useless ( Alshammari et al. , 2016 ). CSE is a major factor in the resistance of the change, but it is a barrier which is difficult to detect. However, when combining CSE with an educator’s background experiences, one may have the ability to determine an educator’s resistance to technology.

Educators who are comfortable with traditional teaching methods may feel more comfortable with a colleague or mentor easing them into the process of integrating technology. This mentor or colleague would be the change agent. The change agent would provide reassurance and support. It would not only require a change in an educators’ knowledge of pedagogy and technology but also in their self-efficacy ( Reid, 2014 ). These mentors can provide just-in-time support and help ease the educator into increasing the use of technology.

Purpose statement and research question

What were the values, beliefs, confidence and level of preparedness of educators making the change from a traditional learning environment to a learning environment integrating technology?

Method and design

Descriptive case studies provide insight into complex issues and describe natural phenomenon within the context of the data that are being questioned ( Zainal, 2007 ). The goal of a qualitative descriptive study is to summarize the experience of the individuals or participants ( Lambert and Lambert, 2012 ). The design is appropriate for this study as the researchers were seeking to gain a rich description of educators’ experiences transitioning from a traditional learning environment to a learning environment integrating technology (Harrison, 2017; Yin, 2013 ). A descriptive statistical analysis was conducted on the 12 Likert-type questions and an inductive analysis was conducted on the narrative data collected from five open-ended questions included in the survey.

Participants

The sample recruited from the membership of Association for Educational Communication and Technology (AECT) during the fall of 2018 were community college, university, graduate level educators and others who had experienced changing from a traditional learning environment to a learning environment integrating technology. AECT has a membership of about 2,000 individuals from 50 countries (T. Lawson, personal communication, September 10, 2018). This population was of special interest because of the value and experience that they place on technology as evidence by their membership in AECT. The members of this group are familiar with technology and embrace the use of technology leaving the move from teacher centered to student centered as the key challenge. An invitation was sent out to the membership through the AECT website, and members of the organization self-selected to take part in the survey by clicking on the Member Consent, “Yes, I agree to participate.” An informed Consent approval was electronically signed through the SurveyMonkey tool describing the purpose and intent of the research study and describing how the participant’s identity and responses would remain protected.

In total, 42 participants started the survey. Tables I–IV provide the demographic information collected from the first four questions of the survey.

Data collection

After an invitation was sent out to the membership through the AECT website, members of the organization self-selected to take part in the survey. Participants were provided with a link to SurveyMonkey where they were asked to complete 12 Likert-type items and five open-ended questions. Descriptive statistics were collected from the Likert-type items. Participants responded to a series of statements indicating he or she strongly agree, agree, neither agree or disagree, disagree, or strongly disagree ( Croasmun and Ostrom, 2011 ; Salkind, 2009 ). Three of the items (7, 10 and 17) were negatively worded requiring the participants to think about the statement avoiding automated responses to the items ( Croasmun and Ostrom, 2011 ). The three items and corresponding responses were translated to a positive wording for analysis purposes. The results of the Likert-type items are displayed in Figures 1–3 . In the final section of the survey, participants were asked to respond to five open-ended questions. SurveyMonkey generated a document with each participants’ narrative comments. Survey results retrieved from SurveyMonkey were anonymous with no participant names or identifiers, other than the demographic information collected was accessible to the researchers.

Procedure for analysis

SurveyMonkey site generated a graphic representing the responses of participants to the 12 Likert-type items. Due to the nature of the 12 items, descriptive statistics analysis was appropriate for describing the qualitative data in terms of percentages ( Hussain, 2012 ). A content analysis approach was used to analysis the narrative responses to the five open-ended questions allowing us to systematically describe the data surfacing descriptive codes leading to major themes ( Finfgeld-Connett, 2013 ; Miles and Huberman, 1994 ; White and Marsh, 2006 ). Researchers initially coded the narrative statements independently, then engaged in a process of reviewing and analyzing the codes through four rounds until consensus was reached on the cluster of codes leading to emerging themes. The codes were unique and used to describe the educators’ experiences and perceptions changing from a traditional learning environment to a learning environment integrating technology ( Hseih and Shannon, 2005 ; Merriam, 2009 ; Vaismoradi et al. , 2013 ).

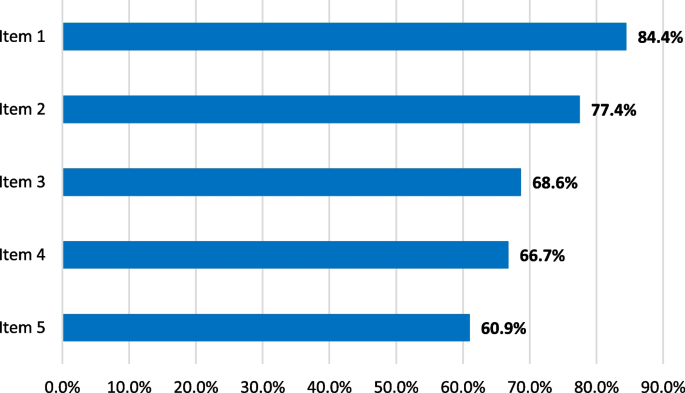

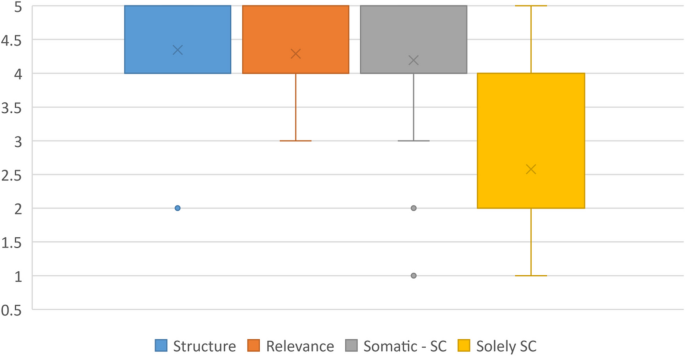

Responses to the Likert-type questions were combined into three figures. The related questions are grouped together for easier analysis. The questions related to confidence are organized into Figure 1 . The questions that addressed beliefs are organized into Figure 2 . The questions that addressed the values of participants are organized in Figure 3 . A detailed description of each figure is provided below.

Likert-type items

Responses to the Likert-type items 6, 9, 10 and 15 focused on the confidence of level participants integrating technology. The results can be seen in Figure 1 . Combining the responses of strongly agree and agree, 97 percent of the participants indicated they had a high level of confidence in integrating technology into their learning environment. In total, 95 percent of the participants had confidence in their abilities to enhance the learning environment with the integration of technology. In total, 81 percent indicated they were prepared for moving from a teacher-centered learning environment to a student-centered learning environment. There was an 86 percent response to the participants’ confidence in technology to enrich and deepen the learning experience for students.

Likert-type items 7, 12, 13, 14 and 17 addressed participants beliefs in technology integration into the classroom with the results displayed in Figure 2 . While the participant responses indicated confidence in technology integration, the beliefs of participations in how the technology contributed to student learning were more varied. In total, 86 percent believed technology contributed to the success of students. The responses to the extent to which technology engages students in higher order thinking indicated 69 percent either strongly agreed or agreed, while 29 percent indicated they neither agree or disagree. In total, 71 percent believed their value as a teacher was enhanced with the integration of technology, 72 percent believe the culture of their organization supports technology integration and 81 percent believed they had adequate training in technology integration.

Participants responses to the value of technology integration were high, at least 95 percent in each item as shown in Figure 3 . There was a 98 percent strongly agreed or agreed to the additional functions technology provides to monitor, adjust and extend student learning. In total, 95 percent of the participants value the opportunities technology integration provided them in creating and generating relevant lessons for students. In addition, 95 percent also valued ongoing training and professional development in integrating technology.

Open-ended questions

A systematic process was used for coding the responses to the open-ended questions. The process began with open coding in which similarities and differences in the responses were identified. Labels were created and examined for the emerging concepts. Axial coding was used to generate relationships between the categories, and these were tested against the theoretical framework. This process was repeated for each of the open-ended questions.

Participants reflected on some of the ways their personal values and beliefs were challenged in Question 18. Of the sample, 36 people responded to the question. Through the analysis of the question, several themes and subthemes were uncovered. These themes were: no impact, concerns about confidence and a change to student-centered instruction.

In total, 16 participants indicated a positive feeling toward technology or that there was no impact on their values or beliefs. One participant stated, “I’ve always believed in the value of technology.” Another said, “My personal beliefs were not challenged. I was one of the teachers leading the technology parade.” Under the theme of confidence, nine of the respondents indicated they had challenges to their beliefs due to concerns of their ability to use technology. One participant stated, “It took me several weeks to feel comfortable combining teaching and using the technology.” Another shared, “I was not sure I could truly deliver as engaging a lesson as I could face-to-face.” A similar comment was related to being able to manage students when technology was added, “My confidence in students’ ability to self-regulate has been challenged more than ever recently […] especially in terms of their unbelievable ability to distract themselves […].” In addition, nine of the respondents indicated the change to a student-centered approach brought about by the technology changes created challenges to their values and beliefs. One respondent shared, “The main challenge was in accepting a more learner-centered approach after decades of using the traditional approach to teaching.” This finding is significant, because it would be anticipated the participants would be comfortable with technology and yet, the move from teacher centered to student centered still held some challenges.

The ways participants were prepared for the change to a learning environment integrating technology was explored through Question 19. There were 36 responses to this question. Through the analysis of the responses, two main themes were uncovered. The themes were: prior experience with technology or formal training with the technology and being self-motivated to learn about the technology. Some of the respondents stated more than one thing that helped them prepare to use technology.

In total, 21 shared they had prior experience with the technology or formal training with technology that helped prepared them. “I was enrolled in technology classes that helped me in college and this opened many avenues for my learning.” Another subject stated, “I was a TA for two semesters for the course I taught. I attended the class and corrected papers, which helped me become familiar the Canvas, the LMS we use.” Other examples of formal training were, “Lots of grad school, at my own expense.” and, “My field is instructional design – it’s what I’m trained to do.”

In total, 18 of the respondents shared they were self-motivated to learn. Their responses included comments such as, “Trying out the technology before bringing it into the classroom.” Another participant stated, “Because of a personal interest in technology, I had been learning on my own.” Watching how-to videos on YouTube was another example of how participants were teaching themselves. There were some comments that were not common enough to merit a theme, but that still seemed worth mentioning. These referenced the importance of collaboration among peers. The comment, “Familiarity with the technology tools was important, but more important was the discourse with colleagues and former students about instructional strategies that allow students to grasp complexity,” reflected the value put on collaboration.