Rubric Design

Main navigation, articulating your assessment values.

Reading, commenting on, and then assigning a grade to a piece of student writing requires intense attention and difficult judgment calls. Some faculty dread “the stack.” Students may share the faculty’s dim view of writing assessment, perceiving it as highly subjective. They wonder why one faculty member values evidence and correctness before all else, while another seeks a vaguely defined originality.

Writing rubrics can help address the concerns of both faculty and students by making writing assessment more efficient, consistent, and public. Whether it is called a grading rubric, a grading sheet, or a scoring guide, a writing assignment rubric lists criteria by which the writing is graded.

Why create a writing rubric?

- It makes your tacit rhetorical knowledge explicit

- It articulates community- and discipline-specific standards of excellence

- It links the grade you give the assignment to the criteria

- It can make your grading more efficient, consistent, and fair as you can read and comment with your criteria in mind

- It can help you reverse engineer your course: once you have the rubrics created, you can align your readings, activities, and lectures with the rubrics to set your students up for success

- It can help your students produce writing that you look forward to reading

How to create a writing rubric

Create a rubric at the same time you create the assignment. It will help you explain to the students what your goals are for the assignment.

- Consider your purpose: do you need a rubric that addresses the standards for all the writing in the course? Or do you need to address the writing requirements and standards for just one assignment? Task-specific rubrics are written to help teachers assess individual assignments or genres, whereas generic rubrics are written to help teachers assess multiple assignments.

- Begin by listing the important qualities of the writing that will be produced in response to a particular assignment. It may be helpful to have several examples of excellent versions of the assignment in front of you: what writing elements do they all have in common? Among other things, these may include features of the argument, such as a main claim or thesis; use and presentation of sources, including visuals; and formatting guidelines such as the requirement of a works cited.

- Then consider how the criteria will be weighted in grading. Perhaps all criteria are equally important, or perhaps there are two or three that all students must achieve to earn a passing grade. Decide what best fits the class and requirements of the assignment.

Consider involving students in Steps 2 and 3. A class session devoted to developing a rubric can provoke many important discussions about the ways the features of the language serve the purpose of the writing. And when students themselves work to describe the writing they are expected to produce, they are more likely to achieve it.

At this point, you will need to decide if you want to create a holistic or an analytic rubric. There is much debate about these two approaches to assessment.

Comparing Holistic and Analytic Rubrics

Holistic scoring .

Holistic scoring aims to rate overall proficiency in a given student writing sample. It is often used in large-scale writing program assessment and impromptu classroom writing for diagnostic purposes.

General tenets to holistic scoring:

- Responding to drafts is part of evaluation

- Responses do not focus on grammar and mechanics during drafting and there is little correction

- Marginal comments are kept to 2-3 per page with summative comments at end

- End commentary attends to students’ overall performance across learning objectives as articulated in the assignment

- Response language aims to foster students’ self-assessment

Holistic rubrics emphasize what students do well and generally increase efficiency; they may also be more valid because scoring includes authentic, personal reaction of the reader. But holistic sores won’t tell a student how they’ve progressed relative to previous assignments and may be rater-dependent, reducing reliability. (For a summary of advantages and disadvantages of holistic scoring, see Becker, 2011, p. 116.)

Here is an example of a partial holistic rubric:

Summary meets all the criteria. The writer understands the article thoroughly. The main points in the article appear in the summary with all main points proportionately developed. The summary should be as comprehensive as possible and should be as comprehensive as possible and should read smoothly, with appropriate transitions between ideas. Sentences should be clear, without vagueness or ambiguity and without grammatical or mechanical errors.

A complete holistic rubric for a research paper (authored by Jonah Willihnganz) can be downloaded here.

Analytic Scoring

Analytic scoring makes explicit the contribution to the final grade of each element of writing. For example, an instructor may choose to give 30 points for an essay whose ideas are sufficiently complex, that marshals good reasons in support of a thesis, and whose argument is logical; and 20 points for well-constructed sentences and careful copy editing.

General tenets to analytic scoring:

- Reflect emphases in your teaching and communicate the learning goals for the course

- Emphasize student performance across criterion, which are established as central to the assignment in advance, usually on an assignment sheet

- Typically take a quantitative approach, providing a scaled set of points for each criterion

- Make the analytic framework available to students before they write

Advantages of an analytic rubric include ease of training raters and improved reliability. Meanwhile, writers often can more easily diagnose the strengths and weaknesses of their work. But analytic rubrics can be time-consuming to produce, and raters may judge the writing holistically anyway. Moreover, many readers believe that writing traits cannot be separated. (For a summary of the advantages and disadvantages of analytic scoring, see Becker, 2011, p. 115.)

For example, a partial analytic rubric for a single trait, “addresses a significant issue”:

- Excellent: Elegantly establishes the current problem, why it matters, to whom

- Above Average: Identifies the problem; explains why it matters and to whom

- Competent: Describes topic but relevance unclear or cursory

- Developing: Unclear issue and relevance

A complete analytic rubric for a research paper can be downloaded here. In WIM courses, this language should be revised to name specific disciplinary conventions.

Whichever type of rubric you write, your goal is to avoid pushing students into prescriptive formulas and limiting thinking (e.g., “each paragraph has five sentences”). By carefully describing the writing you want to read, you give students a clear target, and, as Ed White puts it, “describe the ongoing work of the class” (75).

Writing rubrics contribute meaningfully to the teaching of writing. Think of them as a coaching aide. In class and in conferences, you can use the language of the rubric to help you move past generic statements about what makes good writing good to statements about what constitutes success on the assignment and in the genre or discourse community. The rubric articulates what you are asking students to produce on the page; once that work is accomplished, you can turn your attention to explaining how students can achieve it.

Works Cited

Becker, Anthony. “Examining Rubrics Used to Measure Writing Performance in U.S. Intensive English Programs.” The CATESOL Journal 22.1 (2010/2011):113-30. Web.

White, Edward M. Teaching and Assessing Writing . Proquest Info and Learning, 1985. Print.

Further Resources

CCCC Committee on Assessment. “Writing Assessment: A Position Statement.” November 2006 (Revised March 2009). Conference on College Composition and Communication. Web.

Gallagher, Chris W. “Assess Locally, Validate Globally: Heuristics for Validating Local Writing Assessments.” Writing Program Administration 34.1 (2010): 10-32. Web.

Huot, Brian. (Re)Articulating Writing Assessment for Teaching and Learning. Logan: Utah State UP, 2002. Print.

Kelly-Reilly, Diane, and Peggy O’Neil, eds. Journal of Writing Assessment. Web.

McKee, Heidi A., and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss DeVoss, Eds. Digital Writing Assessment & Evaluation. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press, 2013. Web.

O’Neill, Peggy, Cindy Moore, and Brian Huot. A Guide to College Writing Assessment . Logan: Utah State UP, 2009. Print.

Sommers, Nancy. Responding to Student Writers . Macmillan Higher Education, 2013.

Straub, Richard. “Responding, Really Responding to Other Students’ Writing.” The Subject is Writing: Essays by Teachers and Students. Ed. Wendy Bishop. Boynton/Cook, 1999. Web.

White, Edward M., and Cassie A. Wright. Assigning, Responding, Evaluating: A Writing Teacher’s Guide . 5th ed. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2015. Print.

Know Your Terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single-Point Rubrics

May 1, 2014

Can't find what you are looking for? Contact Us

Whether you’re new to rubrics, or you just don’t know their formal names, it may be time for a primer on rubric terminology.

So let’s talk about rubrics for a few minutes. What we’re going to do here is describe two frequently used kinds of rubrics, holistic and analytic , plus a less common one called the single-point rubric (my favorite, for the record). For each one, we’ll look at an example and explore its pros and cons.

Holistic Rubrics

A holistic rubric is the most general kind. It lists three to five levels of performance, along with a broad description of the characteristics that define each level. The levels can be labeled with numbers (such as 1 through 4), letters (such as A through F) or words (such as Beginning through Exemplary ). What each level is called isn’t what makes the rubric holistic — it’s the way the characteristics are all lumped together.

Suppose you’re an unusually demanding person. You want your loved ones to know what you expect if they should ever make you breakfast in bed. So you give them this holistic rubric:

When your breakfast is done, you simply gather your loved ones and say, “I’m sorry my darlings, but that breakfast was just a 2. Try harder next time.”

The main advantage of a holistic rubric is that it’s easy on the teacher — in the short run, anyway. Creating a holistic rubric takes less time than the others, and grading with one is faster, too. You just look over an assignment and give one holistic score to the whole thing.

The main disadvantage of a holistic rubric is that it doesn’t provide targeted feedback to students , which means they’re unlikely to learn much from the assignment. Although many holistic rubrics list specific characteristics for each level, the teacher gives only one score, without breaking it down into separate qualities. This often leads the student to approach the teacher and ask, “Why did you give me a 2?” If the teacher is the explaining kind, he will spend a few minutes breaking down the score. If not, he’ll say something like, “Read the rubric.” Then the student has to guess which factors had the biggest influence on her score. For a student who really tries hard, it can be heartbreaking to have no idea what she’s doing wrong.

Holistic rubrics are most useful in cases when there’s no time (or need, though that’s hard to imagine) for specific feedback. You see them in standardized testing — the essay portion of the SAT is scored with a 0-6 holistic rubric. When hundreds of thousands of essays have to be graded quickly, and by total strangers who have no time to provide feedback, a holistic rubric comes in handy.

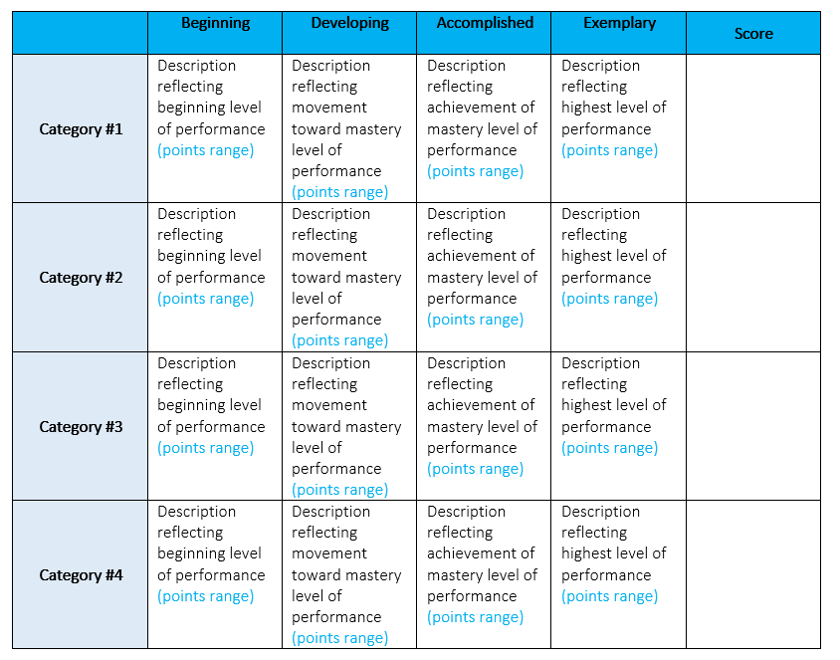

Analytic Rubrics

An analytic rubric breaks down the characteristics of an assignment into parts, allowing the scorer to itemize and define exactly what aspects are strong, and which ones need improvement.

So for the breakfast in bed example, an analytic rubric would look like this:

In this case, you’d give your loved ones a separate score for each category. They might get a 3 on Presentation , but a 2 on Food and just a 1 on Comfort . To make feedback even more targeted, you could also highlight specific phrases in the rubric, like, “the recipient is crowded during the meal” to indicate exactly what went wrong.

This is where we see the main advantage of the analytic rubric: It gives students a clearer picture of why they got the score they got. It is also good for the teacher, because it gives her the ability to justify a score on paper, without having to explain everything in a later conversation.

Analytic rubrics have two significant disadvantages , however: (1) Creating them takes a lot of time . Writing up descriptors of satisfactory work — completing the “3” column in this rubric, for example — is enough of a challenge on its own. But to have to define all the ways the work could go wrong, and all the ways it could exceed expectations, is a big, big task. And once all that work is done, (2) students won’t necessarily read the whole thing. Facing a 36-cell table crammed with 8-point font is enough to send most students straight into a nap. And that means they won’t clearly understand what’s expected of them.

Still, analytic rubrics are useful when you want to cover all your bases, and you’re willing to put in the time to really get clear on exactly what every level of performance looks like.

Single-Point Rubrics

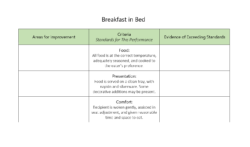

A single-point rubric is a lot like an analytic rubric, because it breaks down the components of an assignment into different criteria. What makes it different is that it only describes the criteria for proficiency ; it does not attempt to list all the ways a student could fall short, nor does it specify how a student could exceed expectations.

A single-point rubric for breakfast in bed would look like this:

Notice that the language in the “Criteria” column is exactly the same as the “3” column in the analytic rubric. When your loved ones receive this rubric, it will include your written comments on one or both sides of each category, telling them exactly how they fell short (“runny eggs,” for example) and how they excelled (“vase of flowers”). Just like with the analytic rubric, if a target was simply met, you can just highlight the appropriate phrase in the center column.

If you’ve never used a single-point rubric, it’s worth a try. In 2010, Jarene Fluckiger studied a collection of teacher action research studies on the use of single-point rubrics. She found that student achievement increased with the use of these rubrics, especially when students helped create them and used them to self-assess their work.

The single-point rubric has several advantages : (1) It contains far less language than the analytic rubric, which means students are more likely to read it and it will take less time to create , while still providing rich detail about what’s expected. (2) Areas of concern and excellence are open-ended . When using full analytic rubrics, I often find that students do things that are not described on the rubric, but still depart from expectations. Because I can’t find the right language to highlight, I find myself hand-writing justifications for a score in whatever space I can find. This is frustrating, time-consuming and messy. With a single-point rubric, there’s no attempt to predict all the ways a student might go wrong. Similarly, the undefined “Advanced” column places no limits on how students might stretch themselves. “If the highest level is already prescribed then creativity may be limited to that pre-determined level,” says Fluckiger. “Students may surprise us if we leave quality open-ended.”

The main disadvantage of single-point rubrics is that using them requires more writing on the teacher’s part. If a student has fallen short in many areas, completing that left-hand column will take more time than simply highlighting a pre-written analytic rubric.

Need Ready-Made Rubrics?

My Rubric Pack gives you four different designs in Microsoft Word and Google Docs formats. It also comes with video tutorials to show you how to customize them for any need, plus a Teacher’s Manual to help you understand the pros and cons of each style. Check it out here:

Fluckiger, J. (2010). Single point rubric: A tool for responsible student self-assessment. Teacher Education Faculty Publications. Paper 5. Retrieved April 25, 2014 from http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/tedfacpub/5 .

Mertler, C. A. (2001). Designing scoring rubrics for your classroom. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation , 7(25). Retrieved April 30, 2014 from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=7&n=25 .

Know Your Terms is my effort to build a user-friendly knowledge base of terms every educator should know. New items will be added on an ongoing basis. If you heard some term at a PD and didn’t want to admit you didn’t know what it meant, send it to me via the contact form and I’ll research it for you.

What to Read Next

Categories: Instruction , Learning Theory

Tags: assessment , college teaching , Grades 3-5 , Grades 6-8 , Grades 9-12 , Grades K-2 , know your terms , rubrics

69 Comments

Jen, This is an awesome, thoughtful post and idea. I’m using this in my class with a final project the kids are turning in this morning. I’m excited about the clarity with which I can evaluate their projects.

I’m so glad to hear it. If you’re willing to share what you made and tell me how it all went later on, I would be thrilled to hear it.

So appreciated! These practical, detailed applications are helpful! Mahalo from Kauai, Hi.

Rubrics are great tools for making expectations explicit. Thanks for this post which gives me some vocabulary to discuss rubrics. Though, I could use some resources on rubric scoring, b/c I see a lot of teachers simply adding up the number of squares and having that be the total point value of an assignment, which leads to incorrect grades on assignments. I’ve found some converters, but haven’t found a resource that has the math broken out.

Thanks for the feedback, Jeremey! You are not the first person to request a clearer breakdown on the math for this rubric (or others), and you’re right, teachers definitely have different approaches to this. I have some good ideas on this, so I will plan a post on it for the near future.

Did you do a post regarding grading a single rubric?

Yup! Here’s Meet the Single Point Rubric . You might also be interested in How To Turn Rubric Scores into Grades . Hope this helps!

Really rubric is a very useful tool when assessing students in class

There is no such thing as an appropriate converter. Levels are levels and points and percentages are points and percentages and never the twain should meet.

(I’m very late to the discussion.)

Years ago, Ken O’Connor was the person who turned my grading around. For that reason, I would be against using the “0-80%” or “0-80 points” piece. O’Connor is very clear about how grades below 50 ruin a grade average.

I would love to be able to grade with standards only, but what I do instead, to fit into our district grading software, is to grade by standards (using letters, where “proficient” is a “B”), and the traditional letters are equal to 95/85/75/65/55. That gives kids a chance if they ever somehow earn only a F. It doesn’t kill the rest of their grade.

(I forgot to say that I absolutely love the one-column rubric. It is going to be a huge help to me this year.)

This post was so helpful! I am struggling right now with assigning Habits of Work grades to my Spanish students in middle and high school. I was using an analytic rubric for both my assessment and the students’ self-assessment, but it’s possible the quantity of words was exacerbating the problem of students scoring themselves in the best column out of reflex or habit. I’m going to try a single-point rubric to see if that can lead us to some more reflective thought.

This website was very helpful. Thank you.

LOVELY post. So didactic and useful. After reading some quite dense posts on rubrics, I’ve enjoyed this a lot. You have now convinced me to use rubrics! THANK YOU Jenny and CONGRATS!!!

SINGLE-POINT rubrics

I have not seen or heard of single point rubrics. I’m really excited to try that out. Less wordy and easier for students to see what is expected of them and get meaningful feedback.

Oooh! I never thought I’d like a post on rubrics, but this was awesome! Thanks for your great explanations. I’m currently working my way through your Teacher’s Guide to Tech/Jumpstart program and I wanted to take a minute and tell you how much I appreciate your site and podcasts too. Everything is so concise, interesting and helpful!

Sariah, thank you!! I haven’t gotten a ton of feedback on the JumpStart program, so it’s really nice to hear that! Let me know if you have any questions!

I am Master of Mathematics Education student and I am busy compiling my assignments on rubrics. Your notes are well explained and straight to the point. However, my Professor have instructed as to look up on primarily rubrics and multi-trait rubrics that i seems not to get. Do you care to differentiate them for me? Thank you.

Hi Martha. I was not familiar with those two terms, so I did a bit of reading in this post: http://carla.umn.edu/assessment/vac/improvement/p_5.html It seems to me that a primary trait rubric focuses on a single, somewhat broad description of how well the student achieved a certain goal. Multi-trait rubrics allow teachers to assess a task on a variety of descriptors. To me, the primary trait seems very much like the holistic rubric, and the multi-trait rubric seems a lot like an analytic rubric. If anyone else reading this knows the finer points of the differences among these four, I would love to hear them!

How to better calculate a grade with a rubric. Please see: http://tinypic.com/r/2dl6d5c/9 .

Thank you so much for this humorous and informative approach to rubrics. It seems to me that the single-point rubric, which I agree makes the most sense for assignment specific rubrics, is really just a clear set of assignment instructions / expectations with the addition of over/under columns to make it rubric-ish.

I love to have students help create rubrics. By the end of the year, we often create the entire rubric together as a class, but often I allow them to start by assigning one “open” section that they think I should grade on for which I help them write “exceeds, meets, doesn’t meet” standards. Then we move on to them assigning points for each standard that I’ve written (this is fascinating for me to see what they weight more heavily), and finally on to writing their own categories for which I write the standards, and then we reverse so that I write the categories and they write the standards. I give a lot of writing and speaking assignments and they really like being involved in how and what and how much we grade. (I never find they are too easy on themselves, either.) I love the single-point rubric especially for assignments I come up with off the cuff and don’t have time to write an elaborate rubric for!

If you’re moving away from traditional grades, the single-point rubric is a perfect instrument for delivering specific feedback.

This is a great site and I really liked the one example used with the multiple rubric styles so we could really understand the difference in them. I am confused about the difference between a Single Point rubric and a Primary Trait rubric. You didn’t mention the Primary Trait rubric so I am wondering if they are the same. Thank you, Karen

Thanks for writing in and for your kind words! I work for Cult of Pedagogy, and in answering your question, I started scrolling myself. Jenn responded to another reader, and I think you might find her response helpful as well as the link:

http://carla.umn.edu/assessment/vac/improvement/p_5.html

“It seems to me that a primary trait rubric focuses on a single, somewhat broad description of how well the student achieved a certain goal. Multi-trait rubrics allow teachers to assess a task on a variety of descriptors. To me, the primary trait seems very much like the holistic rubric, and the multi-trait rubric seems a lot like an analytic rubric.”

Hope this helps!

I do a sort of analytic + single point. I don’t include lots of writing on an analytic rubric. I give them the thick descriptions printed out earlier and I go over them (so each category actually does have detailed descriptions), but the rubric I mark is made up of lots of space and numbers 1-10. I keep it to ten categories. I leave lots of space for comments and comment on every category (even if it’s just one word). I conference with each student briefly when I hand back the rubrics. Each student is given two attempts – first for feedback, second for growth and a final score. (I taught high school theatre, so this method worked the best for me.)

Jen, Thank you for succinctly explaining the types of rubrics and THANK YOU for the free downloadable templates. I will share them with my education senior students!!! AWEsome work you have done.

You are very welcome, Alberta!

Dear Jennifer,

Thank you for the detailed information. I have been using single point rubrics from last year and I love them, but do you think we should give students a checklist as well? If so, what should it look like? I don’t want to kill their creativity, though.

I think the rubric can contain a checklist if you want students to include specific things in their end product, or you could do a separate checklist, then add something like “all items from checklist are included” in your rubric language. There is definitely a gray area here: Defining requirements too narrowly could stifle creativity, but it’s also important to be clear about expectations.

I have been working on a variation of the single-point rubric that I think might be even more useful for communicating expectations and feedback to students. Check it out here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/12JBIcpjeDYuTbQhEgJg2LKC5YPMDwTcIYCtl6jSGTeE/edit?usp=sharing

Really appreciate this post! Thank you. I have used the analytic approach, but I can really see the benefits of a single-point system. Thanks for your clear explanation.

Saying that ‘analytical’ rubrics are difficult and time consuming to write is true, but is also a cop-out. Taking the time to clearly define and articulate student behaviours at each level promotes student independence and self-assessment, and results in better outcomes. The fact that students have departed from what’s written on your rubric suggests that either the assessment wasn’t explained well enough or the rubric itself is of poor quality.

The analytical rubrics provided here fall well short of quality rubric standards. I would suggest reading Patrick griffin’s Assessment for Teaching, and visit the ReliableRubrics websites for good examples.

Thanks for the book and website suggestions, Martin. I do think it’s possible to construct a clear 4-column analytical rubric, but I have rarely seen one that manages to cover all the bases. The ones that DO cover every possible outcome are often insanely long. I’m thinking of some I got in grad school that were–I kid you not–several pages long and written in 9-point font. Despite the fact that I am a diligent student, even I got to the point where I threw in the towel and stopped reading the whole thing. Instead, I just gave my attention to the “3” and “4” columns. I’m guessing that other students do the same thing. If our goal is to have students understand what’s being asked of them and to pay attention to the details, why spend so much time on defining what NOT to do?

Thank you Jennifer, I have shared this with fellow colleagues in Costa Rica. I know this will be of great use!!

Thank you for this work. Your site has been very helfpul to me.

Thank you so much Jennifer! You seem to be an expert in making rubrics! I really appreciate the simplicity of the delivery of your thoughts about rubrics. I just want to ask if there is such a rubric for a cooperative activity? I am Geraldine, by the way, and me and my classmates are planning to conduct cooperative listening activities among Grade 8 students. We are having a hard time looking for a rubric that will assess their outputs as a group. Can you suggest one? Your response will be of great help. Thank you so much. May God bless you more and always!

Hi Geraldine, I work with Cult of Pedagogy and although we can’t think of anything specific to what you’re looking for, I’m thinking you might want to check out our Assessment & Feedback Pinterest board — there are a ton or resources that might help you create a rubric that would be specific to your needs. The most important thing is to identify what you want students to be able to do in the end. For example: listen to others with eye contact. (Be sure to check out Understanding by Design .) Then you can choose a rubric structure that will best fit your needs and provide effective feedback. Other than that, you might be able to find some great ideas through a Google search.

Well, thank you so much! May God bless you!

Great information. Can you tell me how you come to a total/final score on an analytic rubric if the student receives a variety of scores in the different categories? Thanks.

This is a great question! I’d check out Jenn’s post, Speed Up Grading with Rubric Codes . Even if you don’t use the codes, you’ll see in the video how an overall score can be given to a paper, even when scores in indivual categories vary. Basically the overall score reflects where most criteria have been met, along with supportive feedback. Hope this helps!

I loved the all of the rubrics you created for “Breakfast In Bed”. Your topic was an awesome analogy for teacher created tasks. I personally prefer the analytic rubric because I believe it gives the most accurate feedback to the student. If you feel more information is needed, you could expand the categories in the rubric, for example in this case, you could add a column called “sensory enhancements” , such as music or table setting. If you want to add a more personal comment you can always add it in the margin.

This issue has always frustrated me. I have recently been a HUGE proponent of holistic rubrics, but I do see the disadvantage of the feedback issue. For my first time teaching college composition, I used analytic rubrics–and hated them. It wasn’t the making rubrics that was time consuming, but determining how to break up the points and how to assign earned points for a paper. I would score a paper, add up all the points, and realized the paper got a B when, in reality, I knew it was a C-level paper. So I would erase and recalculate until I got the points I thought were more accurate. It took FOREVER!!! After some research, I decided to move to a holistic rubric, and it made grading way faster, but more importantly, I thought the numerical grade was much more accurate and consistent. (Score 6 would get a 95, 5 would be 85, etc., and I would give + or – for 3 more or less points). For feedback, I would annotate and underline/circle the parts of the criteria that they struggled in or did well in and left an end comment. And while I had them turn in a draft that I would give feedback on, I didn’t use the rubric for the draft feedback. Just comments on the paper.

I’m willing to try to single-point, but to get to that final numerical grade (since a no-grade classroom isn’t allowed, unfortunately) you’d still have to break down the points arbitrarily like an analytic rubric. Who’s to say that “structure” should be 30 points while “grammar” should be 10? What’s the actual difference between a 40/50 in “analysis” and a 42/50? My grading PTSD is resurfacing just thinking about grading essays that way. But at the same time, I also don’t like the limited feedback of the holistic rubric.

This is a link to a site where you can download a PDF that talks about a lot of composition issues, but pages 74-76 is about rubrics. Curious to know everyone’s thoughts. https://community.macmillan.com/docs/DOC-1593

Thank you so much 🙂 I learned a lot from this kind of Rubrics 🙂 (y)

Thank you very much for the breakdown of the the types of rubrics. This was very informational!

Thank you for the fantastic article. I came here from the Single Point Rubric post, and I feel so much better equipped to grade my next assignment. Thank you again!

Radhika, Yay! We are glad you found what you needed for your next assignment!

Jennifer, the clear, concise explanations of three types of rubrics are very refreshing. I teach a course called “Assessment and Measurement” to pre-service teachers and I introduce the analytic and holistic rubrics for them to use in performance assessments. The pre-service teachers spend a lot of time with just the language they want to use and, although I think rubrics are the path to more accuracy in grading, I find the idea is overwhelming to novice teachers. May I share this with my students? Of course giving you due credit. This is excellent.

Hi Hazel! Thanks for the positive feedback. You are welcome to share this post with your students!

Thank you! Your picture at the very beginning (and your examples) made the difference between holistic and analytical instantly click for me! Also, I have never heard of single point rubrics before, so I am excited to try them out this fall with an assignment or two that I think they would go perfectly with! Lastly, thanks for the templates!

I’ve been using rubrics for a long time. I started with the most complex, comprehensive things you cannot even imagine. It drove the kids crazy, and me too. Now I teach English to adults (as a 2nd or nth language) and I write much simpler rubrics. But they still have too much information. You are brilliant here with the single point rubric. What do you need to do to get it right? Write in the ways they didn’t match it, which is what you need to do anyways. I’m changing immediately to single point rubrics. I’ll also read your other posting about single point rubrics to see if you have any other ideas. I just met your blog this week (Online Global Academy) and will return, I’m sure. Many thanks. Lee

This is great to hear, Lee! Thanks for sharing.

I’ve always used rubrics but especially appreciate the single point rubric.

Hi My name is Andrena Weir, I work at the American School of Marrakech. Thank you so much for your information. As a Physical Ed teacher these rubrics are great. I like the one column rubric. I feel I spent too much time grading in ways that consume too much time. This is so much appreciated. I need someone like you to be in-contact with if I’m struggling to retrieve new Ideas. Thank you so very much, have the best day.

How about this type of rubric. Al the benefits of analytic but without the verbiage.

The food is raw/burned under/over cooked perfectly cooked

The tray is missing missing some items complete and utensils are dirty clean well presented

You get the idea

e.g. For Maths projects

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/19MXAjBdiEHXwuxg0w7NkRIKuc4X7VNj1qOE74o_vNss/edit?usp=sharing

The blog destroyed my formatting.

The food is || raw/burned || under/over cooked || perfectly cooked

The tray is || missing || missing some items || complete and utensils are || dirty || clean || well presented

or check the linked example

I use rubrics with most of my practical assignments and yes they are very time consuming. After reading this post I’m very excited to try the single-point rubric. Most of the time my students just want to know what is needed. This way they can identify what I want them to be able to do. Thanks so much for this information about rubrics.

So glad this was helpful, Amy! I’ll be sure to let Jenn know.

Want to use analytical rubric

Thanks so much for all of the information. This is great to have as a resource!

I’ve never heard of a single-point rubric before but I love the idea! Your article totally spoke my language and touched on all of my concerns. Thanks for the tips!

Hi, Jennifer, I always come away with actionable tips. I am a faculty developer and Instructional Coach. Rubrics pose challenges for teachers, novice and seasoned alike, so thank you for these discussions to shine a light on rubrics, good and bad.

Meg, I am glad this post was helpful for you in your role! I will be sure to pass on your comments to Jenn.

Being in a rubricade, a crusade of rubrics, against the powers that might be from my school… I’m glad to read what you’ve made.

Neither the academic coordinator nor the headmaster seems to know anything about having more than four levels of achievement. Nothing about having single point rubrics or the ones needed for my laboratory reports which go up to 7 with numbers not correlative.

I’m a high (and middle) school natural sciences teacher, my specialty field is physics.

The rubric in question (rejected by my superiors) has been developped since my first days in the classroom, about 2 thousand eleven. I’ve been modifying it from time to time according to the new breakthroughs experienced in practice.

Maybe your really nice webpage will help me out in going past this nonsense.

Thanks a lot!

Glad you found this helpful!

A holistic rubric is only easier if the faculty are just slapping grades on assignments, which they shouldn’t be doing with any rubric, including a very detailed analytic one. There should be summary comments that explain how the student’s specific response to the assignment meets the descriptor for each score level and then suggestions for what they could do to improve (even if they got an A).

Thanks for your comment- as Jenn mentions in the post, holistic rubrics are limited in their space for feedback. Many teachers prefer the Single Point Rubric for personalized feedback. If the point of rubrics is to set students up with their next steps, this is one you might want to try!

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Rubric Best Practices, Examples, and Templates

A rubric is a scoring tool that identifies the different criteria relevant to an assignment, assessment, or learning outcome and states the possible levels of achievement in a specific, clear, and objective way. Use rubrics to assess project-based student work including essays, group projects, creative endeavors, and oral presentations.

Rubrics can help instructors communicate expectations to students and assess student work fairly, consistently and efficiently. Rubrics can provide students with informative feedback on their strengths and weaknesses so that they can reflect on their performance and work on areas that need improvement.

How to Get Started

Best practices, moodle how-to guides.

- Workshop Recording (Fall 2022)

- Workshop Registration

Step 1: Analyze the assignment

The first step in the rubric creation process is to analyze the assignment or assessment for which you are creating a rubric. To do this, consider the following questions:

- What is the purpose of the assignment and your feedback? What do you want students to demonstrate through the completion of this assignment (i.e. what are the learning objectives measured by it)? Is it a summative assessment, or will students use the feedback to create an improved product?

- Does the assignment break down into different or smaller tasks? Are these tasks equally important as the main assignment?

- What would an “excellent” assignment look like? An “acceptable” assignment? One that still needs major work?

- How detailed do you want the feedback you give students to be? Do you want/need to give them a grade?

Step 2: Decide what kind of rubric you will use

Types of rubrics: holistic, analytic/descriptive, single-point

Holistic Rubric. A holistic rubric includes all the criteria (such as clarity, organization, mechanics, etc.) to be considered together and included in a single evaluation. With a holistic rubric, the rater or grader assigns a single score based on an overall judgment of the student’s work, using descriptions of each performance level to assign the score.

Advantages of holistic rubrics:

- Can p lace an emphasis on what learners can demonstrate rather than what they cannot

- Save grader time by minimizing the number of evaluations to be made for each student

- Can be used consistently across raters, provided they have all been trained

Disadvantages of holistic rubrics:

- Provide less specific feedback than analytic/descriptive rubrics

- Can be difficult to choose a score when a student’s work is at varying levels across the criteria

- Any weighting of c riteria cannot be indicated in the rubric

Analytic/Descriptive Rubric . An analytic or descriptive rubric often takes the form of a table with the criteria listed in the left column and with levels of performance listed across the top row. Each cell contains a description of what the specified criterion looks like at a given level of performance. Each of the criteria is scored individually.

Advantages of analytic rubrics:

- Provide detailed feedback on areas of strength or weakness

- Each criterion can be weighted to reflect its relative importance

Disadvantages of analytic rubrics:

- More time-consuming to create and use than a holistic rubric

- May not be used consistently across raters unless the cells are well defined

- May result in giving less personalized feedback

Single-Point Rubric . A single-point rubric is breaks down the components of an assignment into different criteria, but instead of describing different levels of performance, only the “proficient” level is described. Feedback space is provided for instructors to give individualized comments to help students improve and/or show where they excelled beyond the proficiency descriptors.

Advantages of single-point rubrics:

- Easier to create than an analytic/descriptive rubric

- Perhaps more likely that students will read the descriptors

- Areas of concern and excellence are open-ended

- May removes a focus on the grade/points

- May increase student creativity in project-based assignments

Disadvantage of analytic rubrics: Requires more work for instructors writing feedback

Step 3 (Optional): Look for templates and examples.

You might Google, “Rubric for persuasive essay at the college level” and see if there are any publicly available examples to start from. Ask your colleagues if they have used a rubric for a similar assignment. Some examples are also available at the end of this article. These rubrics can be a great starting point for you, but consider steps 3, 4, and 5 below to ensure that the rubric matches your assignment description, learning objectives and expectations.

Step 4: Define the assignment criteria

Make a list of the knowledge and skills are you measuring with the assignment/assessment Refer to your stated learning objectives, the assignment instructions, past examples of student work, etc. for help.

Helpful strategies for defining grading criteria:

- Collaborate with co-instructors, teaching assistants, and other colleagues

- Brainstorm and discuss with students

- Can they be observed and measured?

- Are they important and essential?

- Are they distinct from other criteria?

- Are they phrased in precise, unambiguous language?

- Revise the criteria as needed

- Consider whether some are more important than others, and how you will weight them.

Step 5: Design the rating scale

Most ratings scales include between 3 and 5 levels. Consider the following questions when designing your rating scale:

- Given what students are able to demonstrate in this assignment/assessment, what are the possible levels of achievement?

- How many levels would you like to include (more levels means more detailed descriptions)

- Will you use numbers and/or descriptive labels for each level of performance? (for example 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 and/or Exceeds expectations, Accomplished, Proficient, Developing, Beginning, etc.)

- Don’t use too many columns, and recognize that some criteria can have more columns that others . The rubric needs to be comprehensible and organized. Pick the right amount of columns so that the criteria flow logically and naturally across levels.

Step 6: Write descriptions for each level of the rating scale

Artificial Intelligence tools like Chat GPT have proven to be useful tools for creating a rubric. You will want to engineer your prompt that you provide the AI assistant to ensure you get what you want. For example, you might provide the assignment description, the criteria you feel are important, and the number of levels of performance you want in your prompt. Use the results as a starting point, and adjust the descriptions as needed.

Building a rubric from scratch

For a single-point rubric , describe what would be considered “proficient,” i.e. B-level work, and provide that description. You might also include suggestions for students outside of the actual rubric about how they might surpass proficient-level work.

For analytic and holistic rubrics , c reate statements of expected performance at each level of the rubric.

- Consider what descriptor is appropriate for each criteria, e.g., presence vs absence, complete vs incomplete, many vs none, major vs minor, consistent vs inconsistent, always vs never. If you have an indicator described in one level, it will need to be described in each level.

- You might start with the top/exemplary level. What does it look like when a student has achieved excellence for each/every criterion? Then, look at the “bottom” level. What does it look like when a student has not achieved the learning goals in any way? Then, complete the in-between levels.

- For an analytic rubric , do this for each particular criterion of the rubric so that every cell in the table is filled. These descriptions help students understand your expectations and their performance in regard to those expectations.

Well-written descriptions:

- Describe observable and measurable behavior

- Use parallel language across the scale

- Indicate the degree to which the standards are met

Step 7: Create your rubric

Create your rubric in a table or spreadsheet in Word, Google Docs, Sheets, etc., and then transfer it by typing it into Moodle. You can also use online tools to create the rubric, but you will still have to type the criteria, indicators, levels, etc., into Moodle. Rubric creators: Rubistar , iRubric

Step 8: Pilot-test your rubric

Prior to implementing your rubric on a live course, obtain feedback from:

- Teacher assistants

Try out your new rubric on a sample of student work. After you pilot-test your rubric, analyze the results to consider its effectiveness and revise accordingly.

- Limit the rubric to a single page for reading and grading ease

- Use parallel language . Use similar language and syntax/wording from column to column. Make sure that the rubric can be easily read from left to right or vice versa.

- Use student-friendly language . Make sure the language is learning-level appropriate. If you use academic language or concepts, you will need to teach those concepts.

- Share and discuss the rubric with your students . Students should understand that the rubric is there to help them learn, reflect, and self-assess. If students use a rubric, they will understand the expectations and their relevance to learning.

- Consider scalability and reusability of rubrics. Create rubric templates that you can alter as needed for multiple assignments.

- Maximize the descriptiveness of your language. Avoid words like “good” and “excellent.” For example, instead of saying, “uses excellent sources,” you might describe what makes a resource excellent so that students will know. You might also consider reducing the reliance on quantity, such as a number of allowable misspelled words. Focus instead, for example, on how distracting any spelling errors are.

Example of an analytic rubric for a final paper

Example of a holistic rubric for a final paper, single-point rubric, more examples:.

- Single Point Rubric Template ( variation )

- Analytic Rubric Template make a copy to edit

- A Rubric for Rubrics

- Bank of Online Discussion Rubrics in different formats

- Mathematical Presentations Descriptive Rubric

- Math Proof Assessment Rubric

- Kansas State Sample Rubrics

- Design Single Point Rubric

Technology Tools: Rubrics in Moodle

- Moodle Docs: Rubrics

- Moodle Docs: Grading Guide (use for single-point rubrics)

Tools with rubrics (other than Moodle)

- Google Assignments

- Turnitin Assignments: Rubric or Grading Form

Other resources

- DePaul University (n.d.). Rubrics .

- Gonzalez, J. (2014). Know your terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single-Point Rubrics . Cult of Pedagogy.

- Goodrich, H. (1996). Understanding rubrics . Teaching for Authentic Student Performance, 54 (4), 14-17. Retrieved from

- Miller, A. (2012). Tame the beast: tips for designing and using rubrics.

- Ragupathi, K., Lee, A. (2020). Beyond Fairness and Consistency in Grading: The Role of Rubrics in Higher Education. In: Sanger, C., Gleason, N. (eds) Diversity and Inclusion in Global Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Analytic Rubrics

The who, what, why, where, when, and how of an analytic rubrics.

WHO : Analytic rubrics are for you and your students .

WHAT : An analytic rubric is a scoring tool that helps you identify the criteria that are relevant to the assessment and learning objectives. It is divided into components of the assignment contains a detailed description that clearly states the performance levels (unacceptable to acceptable) and allows you to assign points/grades/levels based on the students’ performance.

WHY: Rubrics help guide students when completing their assignments by giving the guidelines to follow. Students also know what you are looking for in an assignment, and this leads to fewer questions and more time engaged in the assessment and knowledge attainment. Rubrics help you or your assistant grade assignments objectively from the first submission to the last. Rubrics returned to students with the assignment, give the students basic feedback by selecting the correct criteria they met.

WHERE: Create a paper rubric or use the Canvas interactive grading rubric. Learn more about using Canvas Rubrics by selecting the following link https://guides.instructure.com/m/4152/l/724129-how-do-i-add-a-rubric-to-an-assignment

WHEN : Share the analytic rubric before the assessment to share the criteria they must meet and to help guide them when completing the assignment. After the assignment has been completed, return the marked rubric with the assignment as a form of feedback.

HOW: Watch the following video on Analytic Rubrics.

Optional Handouts: Blank rubric for the session (1)

Rubric Design Activity

Teaching Online: Course Design, Delivery, and Teaching Presence Copyright © by Analisa McMillan. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Open access

- Published: 26 September 2020

Examining consistency among different rubrics for assessing writing

- Enayat A. Shabani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7341-1519 1 &

- Jaleh Panahi 1

Language Testing in Asia volume 10 , Article number: 12 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

8514 Accesses

4 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

The literature on using scoring rubrics in writing assessment denotes the significance of rubrics as practical and useful means to assess the quality of writing tasks. This study tries to investigate the agreement among rubrics endorsed and used for assessing the essay writing tasks by the internationally recognized tests of English language proficiency. To carry out this study, two hundred essays (task 2) from the academic IELTS test were randomly selected from about 800 essays from an official IELTS center, a representative of IDP Australia, which was taken between 2015 and 2016. The test takers were 19 to 42 years of age, 120 of them were female and 80 were males. Three raters were provided with four sets of rubrics used for scoring the essay writing task of tests developed by Educational Testing Service (ETS) and Cambridge English Language Assessment (i.e., Independent TOELF iBT, GRE, CPE, and CAE) to score the essays which had been previously scored officially by a certified IELTS examiner. The data analysis through correlation and factor analysis showed a general agreement among raters and scores; however, some deviant scorings were spotted by two of the raters. Follow-up interviews and a questionnaire survey revealed that the source of score deviations could be related to the raters’ interests and (un)familiarity with certain exams and their corresponding rubrics. Specifically, the results indicated that despite the significance which can be attached to rubrics in writing assessment, raters themselves can exceed them in terms of impact on scores.

Introduction

Writing effectively is a very crucial part of advancement in academic contexts (Rosenfeld et al. 2004 ; Rosenfeld et al. 2001 ), and generally, it is a leading contributor to anyone’s progress in the professional environment (Tardy and Matsuda 2009 ). It is an essential skill enabling individuals to have a remarkable role in today’s communities (Cumming 2001 ; Dunsmuir and Clifford 2003 ). Capable and competent L2 writers demonstrate their idea in the written form, present and discuss their contentions, and defend their stances in different circumstances (Archibald 2004 ; Bridgeman and Carlson 1983 ; Brown and Abeywickrama 2010 ; Cumming 2001 ; Hinkel 2009 ; Hyland 2004 ). Writing correctly and impressively is vital as it ensures that ideas and beliefs are expressed and transferred effectively. Being capable of writing well in the academic environment leads to better scores (Faigley et al. 1981 ; Graham et al. 2005 ; Harman 2013 ). It also helps those who require admission to different organizations of higher education (Lanteigne 2017 ) and provides them with better opportunities to get better job positions. Business communications, proceedings, legal agreements, and military agreements all have to be well written to transmit information in the most influential way (Canseco and Byrd 1989 ; Grabe and Kaplan 1996 ; Hyland 2004 ; Kroll and Kruchten 2003 ; Matsuda 2002 ). What should be taken into consideration is that even well until the mid-1980s, L2 writing in general, and academic L2 writing in particular, was hardly regarded as a major part of standard language tests desirable of being tested on its own right. Later, principally owing to the announced requirements of some universities, it meandered through its path to first being recognized as an option in these tests and then recently turning into an indispensable and integral part of them.

L2 writing is not the mere adequate use of grammar and vocabulary in composing a text, rather it is more about the content, organization and accurate use of language, and proper use of linguistic and textual parts of the language (Chenoweth and Hayes 2001 ; Cumming 2001 ; Holmes 2006 ; Hughes 2003 ; Sasaki 2000 ; Weissberg 2000 ; Wiseman 2012 ). Essay, as one of the official practices of writing, has become a major part of formal education in different countries. It is used by different universities and institutes in selecting qualified applicants, and the applicants’ mastery and comprehension of L2 writing are evaluated by their performance in essay writing.

Essay, as one of the most formal types of writing, constitutes a setting in which clear explanations and arguments on a given topic are anticipated (Kane 2000 ; Muncie 2002 ; Richards and Schmidt 2002 ; Spurr 2005 ). The first steps in writing an essay are to gain a good grasp of the topic, apprehend the raised question and produce the response in an organized way, select the proper lexicon, and use the best structures (Brown and Abeywickrama 2010 ; Wyldeck 2008 ). To many, writing an essay is hampering, yet is a key to success. It makes students think critically about a topic, gather information, organize and develop an idea, and finally produce a fulfilling written text (Levin 2009 ; Mackenzie 2007 ; McLaren 2006 ; Wyldeck 2008 ).

L2 writing has had a great impact on the field of teaching and learning and is now viewed not only as an independent skill in the classroom but also as an integral aspect of the process of instruction, learning, and most freshly, assessment (Archibald 2001 ; Grabe and Kaplan 1996 ; MacDonald 1994 ; Nystrand et al. 1993 ; Raimes 1991 ). Now, it is not possible to think of a dependable test of English language proficiency without a section on essay writing, especially when academic and educational purposes are of concern. Educational Testing Service (ETS) and Cambridge English Language Assessment offer a particular section on essay writing for their tests of English language proficiency. The independent TOEFL iBT writing section, the objective of which is to gauge and assess learners’ ability to logically and precisely express their opinions using their L2 requires the learners to write well at the sentence, paragraph, and essay level. It is written on a computer using a word processing program with rudimentary qualities which does not have a self-checker and a grammar or spelling checker. Generally, the essay should have an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. A standard essay usually has four paragraphs, five is possibly better, and six is too many (Biber et al. 2004 ; Cumming et al. 2000 ). TOEFL iBT is scored based on the candidates’ performance on two tasks in the writing section. Candidates should at least do one of the writing tasks. Scoring could be done either by human rater or automatically (the eRater). Using human judgment for assessing content and meaning along with automated scoring for evaluating linguistic features ensures the consistency and reliability of scores (Jamieson and Poonpon 2013 ; Kong et al. 2009 ; Weigle 2013 ).

The Graduate Record Examination (GRE) analytic writing consists of two different essay tasks, an “issue task” and an “argument task”, the latter being the focus of the present study. Akin to TOELF iBT, the GRE is also written on a computer employing very basic features of a word processing program. Each essay has an introduction including some contextual and upbringing information about what is going to be analyzed, a body in which complex ideas should be articulated clearly and effectively using enough examples and relevant reasons for supporting the thesis statement. Finally, the claims and opinions have to be summed up coherently in the concluding part (Broer et al. 2005 ). The GRE is scored two times on a holistic scale, and usually, the average score is reported if the two scores are within one point; otherwise, a third reader steps in and examines the essay (Staff 2017 ; Zahler 2011 ).

IELTS essay writing (in both Academic and General Modules) involves developing a formal five-paragraph essay in 40 min. Similar to essays in other exams, it should include an introductory paragraph, two to three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph (Aish and Tomlinson 2012 ; Dixon 2015 ; Jakeman 2006 ; Loughead 2010 ; Stewart 2009 ). To score IELTS essay writing, the received scores for the (four) components of the rubric are averaged (Fleming et al. 2011 ).

The writing sections of the Cambridge Advanced Certificate in English (CAE) and the Cambridge English: Proficiency (CPE) exams have two parts. The first part is compulsory and candidates are asked to write in response to an input text including articles, leaflets, notices, and formal and/or informal letters. In the second part, the candidates must select one of the writing tasks that might be a letter, proposal, report, or a review (Brookhart and Haines 2009 ; Corry 1999 ; Duckworth et al. 2012 ; Evans 2005 ; Moore 2009 ). The essays should include an introduction, a body, and a conclusion (Spratt and Taylor 2000 ). Similar to IELTS essay writing, these exams are scored analytically. The scores are added up and then converted to a scale of 1 to 20 (Brookhart 1999 ; Harrison 2010 ).

Assessing L2 writing proficiency is a flourishing area, and the precise assessment of writing is a critical matter. Practically, learners are generally expected to produce a piece of text so that raters can evaluate the overall quality of their performance using a variety of different scoring systems including holistic and analytic scoring, which are the most common and acceptable ways of assessing essays (Anderson 2005 ; Brossell 1986 ; Brown and Abeywickrama 2010 ; Hamp-Lyons 1990 , 1991 ; Kroll 1990 ). Today, the significance of L2 writing assessment is on an increase not only in language-related fields of studies but also arguably in all disciplines, and it is a very pressing concern in various educational and also vocational settings.

L2 writing assessment is the focal point of an effective teaching process of this complicated skill (Jones 2001 ). A diligent assessment of writing completes the way it is taught (White 1985 ). The challenging and thorny natures of assessment and writing skills impede the reliable assessment of an essay (Muenz et al. 1999 ) such that, to date, a plethora of research studies have been conducted to discern the validity and reliability of writing assessment. Huot ( 1990 ) argues that writing assessment encounters difficulty because usually, there are more than two or three raters assessing essays, which may lead to uncertainty in writing assessment.

L2 writing assessment is generally prone to subjectivity and bias, and “the assessment of writing has always been threatened due to raters’ biasedness” (Fahim and Bijani 2011 , p. 1). Ample studies document that raters’ assessment and judgments are biased (Kondo-Brown 2002 ; Schaefer 2008 ). They also suggested that in order to reduce the bias and subjectivity in assessing L2 writing, standard and well-described rating scales, viz rubrics, should be determined (Brown and Jaquith 2007 ; Diederich et al. 1961 ; Hamp-Lyons 2007 ; Jonsson and Svingby 2007 ; Aryadoust and Riazi 2016 ). Furthermore, there are some studies suggesting the tendency of many raters toward subjectivity in writing assessment (Eckes 2005 ; Lumley 2005 ; O’Neil and Lunz 1996 ; Saeidi et al. 2013 ; Schaefer 2008 ). In light of these considerations, it becomes of prominence to improve consistency among raters’ evaluations of writing proficiency and to increase the reliability and validity of their judgments to avoid bias and subjectivity to produce a greater agreement between raters and ratings. The most notable move toward attaining this objective is using rubrics (Cumming 2001 ; Hamp-Lyons 1990 ; Hyland 2004 ; Raimes 1991 ; Weigle 2002 ). In layman’s terms, rubrics ensure that all the raters evaluate a writing task by the same standards (Biggs and Tang 2007 ; Dunsmuir and Clifford 2003 ; Spurr 2005 ). To curtail the probable subjectivity and personal bias in assessing one’s writing, there should be some determined and standard criteria for assessing different types of writing tasks (Condon 2013 ; Coombe et al. 2012 ; Shermis 2014 ; Weigle 2013 ).

Assessment rubrics (alternatively called instruments) should be reliable, valid, practical, fair, and constructive to learning and teaching (Anderson et al. 2011 ). Moskal and Leydens ( 2000 ) considered validity and reliability as the two significant factors when rubrics are used for assessing an individual’s work. Although researchers may define validity and reliability in various ways (for instance, Archibald 2001 ; Brookhart 1999 ; Bachman and Palmer 1996 ; Coombe et al. 2012 ; Cumming 2001 ; Messick 1994 ; Moskal and Leydens 2000 ; Moss 1994 ; Rezaei and Lovorn 2010 ; Weigle 2002 ; White 1994 ; Wiggan 1994 ), they generally agree that validity in this area of investigation is the degree to which the criteria support the interpretations of what is going to be measured. Reliability, they generally settle, is the consistency of assessment scores regardless of time and place. Rubrics and any rating scales should be so developed to corroborate these two important factors and equip raters and scorers with an authoritative tool to assess writing tasks fairly. Arguably, “the purpose of the essay task, whether for diagnosis, development, or promotion, is significant in deciding which scale is chosen” (Brossell 1986 , p. 2). As rubrics should be conceived and designed with the purpose of assessment of any given type of written task (Crusan 2015 ; Fulcher 2010 ; Knoch 2009 ; Malone and Montee 2014 ; Weigle 2002 ), the development and validation of rating scales are very challenging issues.

Writing rubrics can also help teachers gauge their own teaching (Coombe et al. 2012 ). Rubrics are generally perceived as very significant resources attainable for teachers enabling them to provide insightful feedback on L2 writing performance and assess learners’ writing ability (Brown and Abeywickrama 2010 ; Knoch 2011 ; Shaw and Weir 2007 ; Weigle 2002 ). Similarly, but from another perspective, rubrics help learners to follow a clear route of progress and contribute to their own learning (Brown and Abeywickrama 2010 ; Eckes 2012 ). Well-defined rubrics are constructive criteria, which help learners to understand what the desired performance is (Bachman and Palmer 1996 ; Fulcher and Davidson 2007 ; Weigle 2002 ). Employing rubrics in the realm of writing assessment helps learners understand raters’ and teachers’ expectations better, judge and revise their own work more successfully, promote self-assessment of their learning, and improve the quality of their writing task. Rubrics can be used as an effective tool enabling learners to focus on their efforts, produce works of higher quality, get better grades, find better jobs, and feel more concerned and confident about doing their assignment (Bachman and Palmer 2010 ; Cumming 2013 ; Kane 2006 ).

Rubrics are set to help scorers evaluate writers’ performances and provide them with very clear descriptions about organization and coherence, structure and vocabulary, fluent expressions, ideas and opinions, among other things. They are also practical for the purpose of describing one’s competence in logical sequencing of ideas in producing a paragraph, use of sufficient and proper grammar and vocabulary related to the topic (Kim 2011 ; Pollitt and Hutchinson 1987 ; Weigle 2002 ). Employing rubrics reduces the time required to assess a writing performance and, most importantly, well-defined rubrics clarify criteria in particular terms enabling scorers and raters to judge a work based on standard and unified yardsticks (Gustilo and Magno 2015 ; Kellogg et al. 2016 ; Klein and Boscolo 2016 ).

Selecting and designing an effective rating scale hinges upon the purpose of the test (Alderson et al. 1995 ; Attali et al. 2012 ; Becker 2011 ; East 2009 ). Although rubrics are crucial in essay evaluation, choosing the appropriate rating scale and forming criteria based on the purpose of assessment are as important (Bacha 2001 ; Coombe et al. 2012 ). It seems that a considerable part of scale developers prefers to adapt their scoring scales from a well-established existing one (Cumming 2001 ; Huot et al. 2009 ; Wiseman 2012 ). The relevant literature supports the idea of adapting rating scales used in large-scale tests for academic purposes (Bacha 2001 ; Leki et al. 2008 ). Yet, East ( 2009 ) warned about the adaptation of rating scales from similar tests, especially when they are to be used across languages.

Holistic and analytic scoring systems are now widely used to identify learners’ writing proficiency levels for different purposes (Brown and Abeywickrama 2010 ; Charney 1984 ; Cohen 1994 ; Coombe et al. 2012 ; Cumming 2001 ; Hamp-Lyons 1990 ; Reid 1993 ; Weir 1990 ). Unlike the analytic scoring system, the holistic one takes the whole written text into consideration. This scoring system generally emphasizes what is done well and what is deficient (Brown and Hudson 2002 ; White 1985 ). The analytic scoring system (multi-trait rubrics), however, includes discrete components (Bacha 2001 ; Becker 2011 ; Brown and Abeywickrama 2010 ; Coombe et al. 2012 ; Hamp-Lyons 2007 ; Knoch 2009 ; Kuo 2007 ; Shaw and Weir 2007 ). To Weigle ( 2002 ), accuracy, cohesion, content, organization, register, and appropriacy of language conventions are the key components or traits of an analytic scoring system. One of the early analytic scoring rubrics for writing was employed in the ESL Composition by Jacobs et al. 1981 , which included five components, namely language development, organization, vocabulary, language use, and mechanics).

Each scoring system has its own merits and limitations. One of the advantages of analytic scoring is its distinctive reliability in scoring (Brown et al. 2004 ; Zhang et al. 2008 ). Some researchers (e.g. Johnson et al. 2000 ; McMillan 2001 ; Ward and McCotter 2004 ) contend that analytic scoring provides the maximum opportunity for reliability between raters and ratings since raters can use one scoring criteria for different writing tasks at a time. Yet, Myford and Wolfe ( 2003 ) considered the halo effect as one of the major disadvantages of analytic rubrics. The most commonly recognized merit of holistic scoring is its feasibility as it requires less time. However, it does not encompass different criteria, affecting its validity in comparison to analytic scoring, as it entails the personal reflection of raters (Elder et al. 2007 ; Elder et al. 2005 ; Noonan and Sulsky 2001 ; Roch and O’Sullivan 2003 ). Cohen ( 1994 ) stated that the major demerit of the holistic scoring system is its relative weakness in providing enough diagnostic information about learners’ writing.

Many research studies have been conducted to examine the effect of analytic and holistic scoring systems on writing performance. For instance, more than half a century ago, Diederich et al. ( 1961 ) carried out a study on the holistic scoring system in a large-scale testing context. Three-hundred essays were rated by 53 raters, and the results showed variation in ratings based on three criteria, namely ideas, organization, and language. About two score years later, Borman ( 1979 ) conducted a similar study on 800 written tasks and found that the variations can be attributed to ideas, organizations, and supporting details. Charney ( 1984 ) did a comparison study between analytic and holistic rubrics in assessing writing performance in terms of validity and found a holistic scoring system to be more valid. Bauer ( 1981 ) compared the cost-effectiveness of analytic and holistic rubrics in assessing essay tasks and found the time needed to train raters to be able to employ analytic rubrics was about two times more than the required time to train raters to use the holistic one. Moreover, the time needed to grade the essays using analytic rubrics was four times the time needed to grade essays using holistic rubrics. Some studies reported findings that corroborated that holistic scoring can be the preferred scoring system in large-scale testing context (Bell et al. 2009 ). Chi ( 2001 ) compared analytic and holistic rubrics in terms of their appropriacy, the agreement of the learners’ scores, and the consistency of rater. The findings revealed that raters who used the holistic scoring system outperformed those employing analytic scoring in terms of inter-rater and intra-rater reliability. Thus, there is research to suggest the superiority of analytic rubrics in assessing writing performance in terms of reliability and accuracy in scoring (Birky 2012 ; Brown and Hudson 2002 ; Diab and Balaa 2011 ; Kondo-Brown 2002 ). It is, generally speaking, difficult to decide which one is the best, and the research findings so far can best be described as inconclusive.

Rubrics of internationally recognized tests used in assessing essays have many similar components, including organization and coherence, task achievement, range of vocabulary used, grammatical accuracy, and types of errors. The wording used, however, is usually different in different rubrics, for instance, “task achievement” that is used in the IELTS rubrics is represented as the “realization of tasks” in CPE and CAE, “content coverage” in GRE, and “task accomplishment” in TOEFL iBT. Similarly, it can be argued that the point of focus of the rubrics for different tests may not be the same. Punctuation, spelling, and target readers’ satisfaction, for example, are explicitly emphasized in CAE and CPE while none of them are mentioned in GRE and TOEFL iBT. Instead, idiomaticity and exemplifications are listed in the TOEFL iBT rubrics, and using enough supporting ideas to address the topic and task is the focus of GRE rating scales (Brindley 1998 ; Hamp-Lyons and Kroll 1997 ; White 1984 ).

Broadly speaking, the rubrics employed in assessing L2 writing include the above-mentioned components but as mentioned previously, they are commonly expressed in different wordings. For example, the criteria used in IELTS Task 2 rating scale are task achievement, coherence and cohesion, lexical resources, and grammatical range and accuracy. These criteria are the ones based on which candidates’ work is assessed and scored. Each of these criteria has its own descriptors, which determine the performance expected to secure a certain score on that criterion. The summative outcome, along with the standards, determines if the candidate has attained the required qualification which is established based on the criteria. The summative outcome of IELTS Task 2 rating scale will be between 0 and 9. Similar components are used in other standard exams like CAE and CPE, their summative outcomes being determined from 1 to 5. Their criteria are used to assess content (relevance and completeness), language (vocabulary, grammar, punctuation, and spelling), organization (logic, coherence, variety of expressions and sentences, and proper use of linking words and phrases), and finally communicative achievement (register, tone, clarity, and interest). CAE and CPE have their particular descriptors which demonstrate the achievement of each learners’ standard for each criterion (Betsis et al. 2012 ; Capel and Sharp 2013 ; Dass 2014 ; Obee 2005 ). Similar to the other rubrics, the GRE scoring scale has the main components like the other essay writing scales but in different wordings. In the GRE, the standards and summative outcomes are reported from 0–6, denoting fundamentally deficient, seriously flawed, limited, adequate, strong, and outstanding, respectively. Like the GRE, the TOEFL iBT is scored from 0–5. Akin to the GRE, Independent Writing Rubrics for the TOEFL iBT delineates the descriptors clearly and precisely (Erdosy 2004 ; Gass et al. 2011 ).

Abundant research studies have been carried out to show that idea and content, organization, cohesion and coherence, vocabulary and grammar, and language and mechanics are the main components of essay rubrics (Jacobs et al. 1981 ; Schoonen 2005 ). What has been considered a missing element in the analytic rating scale is the raters’ knowledge of, and familiarity with, rubrics and their corresponding elements as one of the key yardsticks in measuring L2 writing ability (Arter et al. 1994 ; Sasaki and Hirose 1999 ; Weir 1990 ). Raters play a crucial role in assessing writing. There is research to allude to the impact of raters’ judgments on L2 writing assessment (Connor-Linton 1995 ; Sasaki 2000 ; Schoonen 2005 ; Shi 2001 ).

The past few decades have witnessed an increasing growth in research on different scoring systems and raters’ critical role in assessment. There are some recent studies discussing the importance of rubrics in L2 writing assessment (e.g. Deygers et al. 2018 ; Fleckenstein et al. 2018 ; Rupp et al. 2019 ; Trace et al. 2016 ; Wesolowski et al. 2017 ; Wind et al. 2018 ). They commonly consider rubrics as significant tools for measuring L2 learners’ performances and suggest that rubrics enhance the reliability and validity of writing assessment. More importantly, they argue that employing rubrics can increase the consistency among raters.

Shi ( 2001 ) made comparisons between native and non-native, as well as between experienced and novice raters, and found that raters have their own criteria to assess an essay, virtually regardless of whether they are native or non-native and experienced or novice. Lumley ( 2002 ) and Schoonen ( 2005 ) conducted comparison studies between two groups of raters, one group trained expert raters provided with no standard rubrics, the other group novice raters with no training who had standard rubrics. The trained raters with no rubrics outperformed the other group in terms of accuracy in assessing the essays, implying the importance of raters. Rezaei and Lovorn ( 2010 ) compared the use of rubrics between summative and formative assessment. They argued that using rubrics in summative assessment is predominant and that it overshadows the formative aspects of rubrics. Their results showed that rubrics can be more beneficial when used for formative assessment purposes.