What are You Looking for?

What Does Essayed Mean Sexually Urban Dictionary

When it comes to navigating the world of sexuality and relationships, it’s important to understand the various terms and slang that may pop up. One such term that has gained popularity in recent years is ‘essayed,’ as defined by the Urban Dictionary. So, what does ‘essayed’ mean in a sexual context?

According to the Urban Dictionary, ‘essayed’ refers to the act of exploring or attempting something sexually. It can be used to describe trying out new techniques, positions, or experiences with a partner. Essentially, it’s about experimenting and pushing boundaries in the bedroom.

For example, a couple might decide to essayed a new kink they’ve been curious about, or a person could essayed incorporating toys into their solo play. The term encompasses a wide range of sexual activities and interests, emphasizing the importance of exploration and open communication in sexual relationships.

Case studies have shown that essayed can lead to increased satisfaction and intimacy in relationships. By being open to trying new things and discussing desires with partners, individuals can discover new depths of pleasure and connection. This can help keep relationships exciting and fulfilling over time, preventing stagnation and boredom.

Statistics also support the benefits of essayed in sexual relationships. A survey conducted by a leading relationship research institute found that couples who regularly essayed new activities in the bedroom reported higher levels of sexual satisfaction and overall relationship happiness. This highlights the importance of keeping an open mind and being willing to step outside of one’s comfort zone when it comes to sex.

In conclusion, understanding what ‘essayed’ means in a sexual context can help individuals navigate their relationships and explore new avenues of pleasure. By embracing the spirit of essayed, people can foster greater intimacy, satisfaction, and excitement in their sexual experiences. So don’t be afraid to essayed new things and push the boundaries of your sexual boundaries!

Woke Meaning Urban Dictionary

Snail Trail Urban Dictionary

PMO Urban Dictionary

Moon Cricket Urban Dictionary

Got a different take cancel reply.

Every slang has its story, and yours matters! If our explanation didn’t quite hit the mark, we’d love to hear your perspective. Share your own definition below and help us enrich the tapestry of urban language.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Share Your Definition:

Your Name *

Email Address *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Your Definition!

NEWS... BUT NOT AS YOU KNOW IT

Sex slang glossary: 20 naughty terms from rail to Netflix and Chill

Share this with

To quote Salt-N-Pepa, let’s talk about sex , baby. Or, rather, let’s talk about how we talk about sex.

Whether it’s a euphemism used to shy away from talking about a topic that’s too taboo from some, or the complete opposite and a visceral, visual slang term that penetrates the mind, we’ve invented a lot of ways to start discourse around intercourse.

There’s a popular tidbit about the Inuit people having over 50 words for snow, but we might have them beat for the different terms for sex.

Here, we take a look at some of the favourite phrases used to discuss doing the deed…

What does getting railed mean?

Let’s start off with one of the more uncouth phrases – since Google search results indicate a lot of people are curious as to what this particular saying means.

Getting railed, quite literally, means having sex – or, if you prefer to take the cue from Urban Dictionary, it means the act of having wild, wild sex.

So, making romantic, meaningful love, this is not.

Netflix and Chill

Netflix and chill has become the most common mating call for a modern day audience.

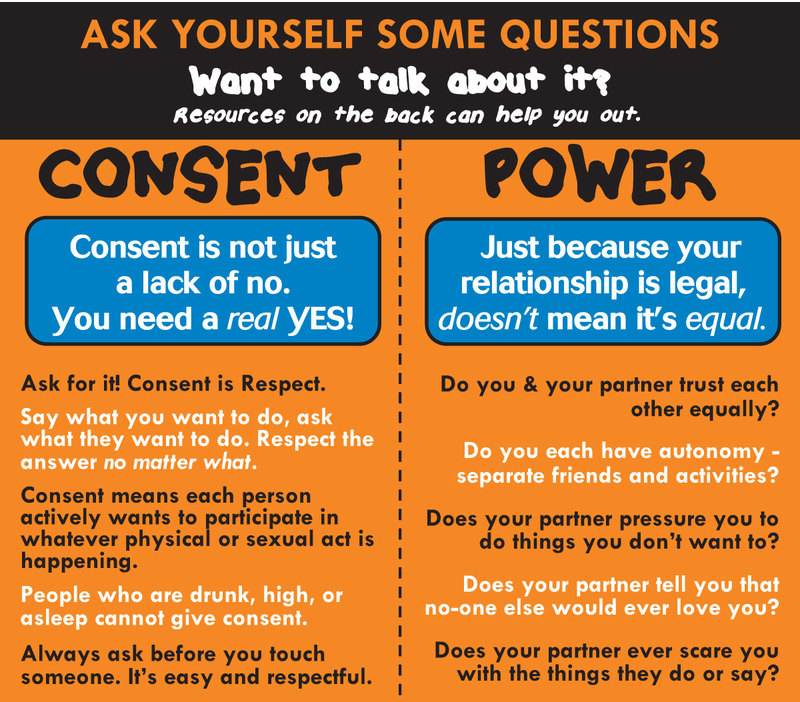

To Netflix and Chill implies putting on Netflix as background noise – or a convincing alibi – as you and your partner(s) engage in a bit of consensual fun.

Some of these terms get their names from the implication that a penis is involved in the act.

Boning is such a term – entering the lexicon most likely as an after-effect to boner becoming a popular term for an erect penis.

D***ing down

If you have been d***ed down, you have had vigorous sex – this one is fairly self-explanatory.

Clapping cheeks

Getting one’s cheeks clapped is a newer term which is rising in popularity.

The name comes from the idea that, when you are in the throes of very intense sex, bum cheeks could make a clapping sound.

Porking is another term people use forhaving sex.

We wouldn’t suggest Googling the term, but there are some who think the term came about because squealing, the sound associated with pigs, is sometimes the sign that sexual partners are having a good time.

The origins of this term should be fairly obvious for anyone with, or who has sex with people with, a penis, sometimes colloquially called a shaft.

Nothing to do with the crime fighting cop.

This is a term most often associated with sexual acts between people who identify as men.

Breeding, or to be bred, generally means having unprotected anal sex.

There are too many to name, but other phrases for having sex that deserve a shoutout include:

- Laying pipe

- Taking the skin boat to tuna town

- Getting drilled

- Nutting/Busting a nut

Euphemisms for having sex

In Human Nature, Queen of Pop and queen of never shying away from the subject, Madonna proclaimed ‘oops, I didn’t know I couldn’t talk about sex’ – and she was on to something.

Some people are more comfortable using gentler language to avoid any blushes.

Some euphemisms that actually mean having sex include:

- Making love

- Knocking boots

- Hitting the sheets

- Going all the way

- Getting lucky

MORE : Woman reveals how to have an orgasm by rubbing your lower back

MORE : Mindful sex could give your sex life the boost you’ve been looking for

Follow Metro across our social channels, on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram .

More from Metro

I'm second-fiddle to everything my partner does – are we drifting apart?

Share your views in the comments below.

To the lady buying coffee, wearing a green leather jacket at South Ealing…

You were tall, dark and handsome and dressed smartly for work, with a…

Get us in your feed

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Pride Month

A guide to gender identity terms.

Laurel Wamsley

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara, a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity." Kaz Fantone for NPR hide caption

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara, a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity."

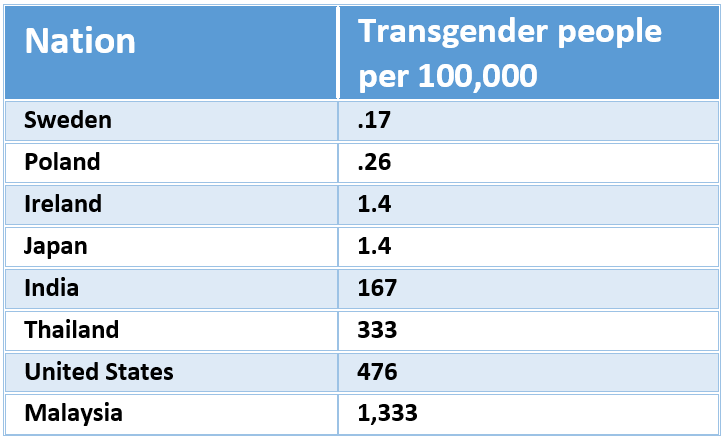

Issues of equality and acceptance of transgender and nonbinary people — along with challenges to their rights — have become a major topic in the headlines. These issues can involve words and ideas and identities that are new to some.

That's why we've put together a glossary of terms relating to gender identity. Our goal is to help people communicate accurately and respectfully with one another.

Proper use of gender identity terms, including pronouns, is a crucial way to signal courtesy and acceptance. Alex Schmider , associate director of transgender representation at GLAAD, compares using someone's correct pronouns to pronouncing their name correctly – "a way of respecting them and referring to them in a way that's consistent and true to who they are."

Glossary of gender identity terms

This guide was created with help from GLAAD . We also referenced resources from the National Center for Transgender Equality , the Trans Journalists Association , NLGJA: The Association of LGBTQ Journalists , Human Rights Campaign , InterAct and the American Psychological Association . This guide is not exhaustive, and is Western and U.S.-centric. Other cultures may use different labels and have other conceptions of gender.

One thing to note: Language changes. Some of the terms now in common usage are different from those used in the past to describe similar ideas, identities and experiences. Some people may continue to use terms that are less commonly used now to describe themselves, and some people may use different terms entirely. What's important is recognizing and respecting people as individuals.

Jump to a term: Sex, gender , gender identity , gender expression , cisgender , transgender , nonbinary , agender , gender-expansive , gender transition , gender dysphoria , sexual orientation , intersex

Jump to Pronouns : questions and answers

Sex refers to a person's biological status and is typically assigned at birth, usually on the basis of external anatomy. Sex is typically categorized as male, female or intersex.

Gender is often defined as a social construct of norms, behaviors and roles that varies between societies and over time. Gender is often categorized as male, female or nonbinary.

Gender identity is one's own internal sense of self and their gender, whether that is man, woman, neither or both. Unlike gender expression, gender identity is not outwardly visible to others.

For most people, gender identity aligns with the sex assigned at birth, the American Psychological Association notes. For transgender people, gender identity differs in varying degrees from the sex assigned at birth.

Gender expression is how a person presents gender outwardly, through behavior, clothing, voice or other perceived characteristics. Society identifies these cues as masculine or feminine, although what is considered masculine or feminine changes over time and varies by culture.

Cisgender, or simply cis , is an adjective that describes a person whose gender identity aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Transgender, or simply trans, is an adjective used to describe someone whose gender identity differs from the sex assigned at birth. A transgender man, for example, is someone who was listed as female at birth but whose gender identity is male.

Cisgender and transgender have their origins in Latin-derived prefixes of "cis" and "trans" — cis, meaning "on this side of" and trans, meaning "across from" or "on the other side of." Both adjectives are used to describe experiences of someone's gender identity.

Nonbinary is a term that can be used by people who do not describe themselves or their genders as fitting into the categories of man or woman. A range of terms are used to refer to these experiences; nonbinary and genderqueer are among the terms that are sometimes used.

Agender is an adjective that can describe a person who does not identify as any gender.

Gender-expansive is an adjective that can describe someone with a more flexible gender identity than might be associated with a typical gender binary.

Gender transition is a process a person may take to bring themselves and/or their bodies into alignment with their gender identity. It's not just one step. Transitioning can include any, none or all of the following: telling one's friends, family and co-workers; changing one's name and pronouns; updating legal documents; medical interventions such as hormone therapy; or surgical intervention, often called gender confirmation surgery.

Gender dysphoria refers to psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one's sex assigned at birth and one's gender identity. Not all trans people experience dysphoria, and those who do may experience it at varying levels of intensity.

Gender dysphoria is a diagnosis listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Some argue that such a diagnosis inappropriately pathologizes gender incongruence, while others contend that a diagnosis makes it easier for transgender people to access necessary medical treatment.

Sexual orientation refers to the enduring physical, romantic and/or emotional attraction to members of the same and/or other genders, including lesbian, gay, bisexual and straight orientations.

People don't need to have had specific sexual experiences to know their own sexual orientation. They need not have had any sexual experience at all. They need not be in a relationship, dating or partnered with anyone for their sexual orientation to be validated. For example, if a bisexual woman is partnered with a man, that does not mean she is not still bisexual.

Sexual orientation is separate from gender identity. As GLAAD notes , "Transgender people may be straight, lesbian, gay, bisexual or queer. For example, a person who transitions from male to female and is attracted solely to men would typically identify as a straight woman. A person who transitions from female to male and is attracted solely to men would typically identify as a gay man."

Intersex is an umbrella term used to describe people with differences in reproductive anatomy, chromosomes or hormones that don't fit typical definitions of male and female.

Intersex can refer to a number of natural variations, some of them laid out by InterAct . Being intersex is not the same as being nonbinary or transgender, which are terms typically related to gender identity.

The Picture Show

Nonbinary photographer documents gender dysphoria through a queer lens, pronouns: questions and answers.

What is the role of pronouns in acknowledging someone's gender identity?

Everyone has pronouns that are used when referring to them – and getting those pronouns right is not exclusively a transgender issue.

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara , a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity."

"So, for example, using the correct pronouns for trans and nonbinary youth is a way to let them know that you see them, you affirm them, you accept them and to let them know that they're loved during a time when they're really being targeted by so many discriminatory anti-trans state laws and policies," O'Hara says.

"It's really just about letting someone know that you accept their identity. And it's as simple as that."

Getting the words right is about respect and accuracy, says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen, deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality. Kaz Fantone for NPR hide caption

Getting the words right is about respect and accuracy, says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen, deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality.

What's the right way to find out a person's pronouns?

Start by giving your own – for example, "My pronouns are she/her."

"If I was introducing myself to someone, I would say, 'I'm Rodrigo. I use him pronouns. What about you?' " says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen , deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality.

O'Hara says, "It may feel awkward at first, but eventually it just becomes another one of those get-to-know-you questions."

Should people be asking everyone their pronouns? Or does it depend on the setting?

Knowing each other's pronouns helps you be sure you have accurate information about another person.

How a person appears in terms of gender expression "doesn't indicate anything about what their gender identity is," GLAAD's Schmider says. By sharing pronouns, "you're going to get to know someone a little better."

And while it can be awkward at first, it can quickly become routine.

Heng-Lehtinen notes that the practice of stating one's pronouns at the bottom of an email or during introductions at a meeting can also relieve some headaches for people whose first names are less common or gender ambiguous.

"Sometimes Americans look at a name and are like, 'I have no idea if I'm supposed to say he or she for this name' — not because the person's trans, but just because the name is of a culture that you don't recognize and you genuinely do not know. So having the pronouns listed saves everyone the headache," Heng-Lehtinen says. "It can be really, really quick once you make a habit of it. And I think it saves a lot of embarrassment for everybody."

Might some people be uncomfortable sharing their pronouns in a public setting?

Schmider says for cisgender people, sharing their pronouns is generally pretty easy – so long as they recognize that they have pronouns and know what they are. For others, it could be more difficult to share their pronouns in places where they don't know people.

But there are still benefits in sharing pronouns, he says. "It's an indication that they understand that gender expression does not equal gender identity, that you're not judging people just based on the way they look and making assumptions about their gender beyond what you actually know about them."

How is "they" used as a singular pronoun?

"They" is already commonly used as a singular pronoun when we are talking about someone, and we don't know who they are, O'Hara notes. Using they/them pronouns for someone you do know simply represents "just a little bit of a switch."

"You're just asking someone to not act as if they don't know you, but to remove gendered language from their vocabulary when they're talking about you," O'Hara says.

"I identify as nonbinary myself and I appear feminine. People often assume that my pronouns are she/her. So they will use those. And I'll just gently correct them and say, hey, you know what, my pronouns are they/them just FYI, for future reference or something like that," they say.

O'Hara says their family and friends still struggle with getting the pronouns right — and sometimes O'Hara struggles to remember others' pronouns, too.

"In my community, in the queer community, with a lot of trans and nonbinary people, we all frequently remind each other or remind ourselves. It's a sort of constant mindfulness where you are always catching up a little bit," they say.

"You might know someone for 10 years, and then they let you know their pronouns have changed. It's going to take you a little while to adjust, and that's fine. It's OK to make those mistakes and correct yourself, and it's OK to gently correct someone else."

What if I make a mistake and misgender someone, or use the wrong words?

Simply apologize and move on.

"I think it's perfectly natural to not know the right words to use at first. We're only human. It takes any of us some time to get to know a new concept," Heng-Lehtinen says. "The important thing is to just be interested in continuing to learn. So if you mess up some language, you just say, 'Oh, I'm so sorry,' correct yourself and move forward. No need to make it any more complicated than that. Doing that really simple gesture of apologizing quickly and moving on shows the other person that you care. And that makes a really big difference."

Why are pronouns typically given in the format "she/her" or "they/them" rather than just "she" or "they"?

The different iterations reflect that pronouns change based on how they're used in a sentence. And the "he/him" format is actually shorter than the previously common "he/him/his" format.

"People used to say all three and then it got down to two," Heng-Lehtinen laughs. He says staff at his organization was recently wondering if the custom will eventually shorten to just one pronoun. "There's no real rule about it. It's absolutely just been habit," he says.

Amid Wave Of Anti-Trans Bills, Trans Reporters Say 'Telling Our Own Stories' Is Vital

But he notes a benefit of using he/him and she/her: He and she rhyme. "If somebody just says he or she, I could very easily mishear that and then still get it wrong."

What does it mean if a person uses the pronouns "he/they" or "she/they"?

"That means that the person uses both pronouns, and you can alternate between those when referring to them. So either pronoun would be fine — and ideally mix it up, use both. It just means that they use both pronouns that they're listing," Heng-Lehtinen says.

Schmider says it depends on the person: "For some people, they don't mind those pronouns being interchanged for them. And for some people, they are using one specific pronoun in one context and another set of pronouns in another, dependent on maybe safety or comfortability."

The best approach, Schmider says, is to listen to how people refer to themselves.

Why might someone's name be different than what's listed on their ID?

Heng-Lehtinen notes that there's a perception when a person comes out as transgender, they change their name and that's that. But the reality is a lot more complicated and expensive when it comes to updating your name on government documents.

"It is not the same process as changing your last name when you get married. There is bizarrely a separate set of rules for when you are changing your name in marriage versus changing your name for any other reason. And it's more difficult in the latter," he says.

"When you're transgender, you might not be able to update all of your government IDs, even though you want to," he says. "I've been out for over a decade. I still have not been able to update all of my documents because the policies are so onerous. I've been able to update my driver's license, Social Security card and passport, but I cannot update my birth certificate."

"Just because a transgender person doesn't have their authentic name on their ID doesn't mean it's not the name that they really use every day," he advises. "So just be mindful to refer to people by the name they really use regardless of their driver's license."

NPR's Danielle Nett contributed to this report.

- transgender

- gender identity

60 Sex-Relevant Terms You May Not Know — and Why You Should

As sex-relevant words proliferate, so do our ways of living and loving..

Posted April 6, 2017 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- The Fundamentals of Sex

- Find a sex therapist near me

Matters of sex, relationships, sexual orientation , and gender identity all used to seem much simpler than they are now — even if they really weren’t. Now, the list of letters that used to be limited to LGBT never stops growing.

The additions to all the sexual orientations include some non-sexual , or not very sexual, orientations. We’ve also learned to appreciate orientations other than sexual ones, such as orientations toward relationships. A binary that once seemed utterly self-evident, male vs. female, is now routinely questioned.

Reading a terrific thesis, “Party of One,” by Kristen Bernhardt, woke me up to the proliferation of new concepts relevant to relationships, sexual orientations, gender identities, and more. (Thank you, Kristen.) So I set out to spend an evening gathering some relevant definitions.

Many days later, I was still at it. I admit to shaking my head in exasperation a few times along the way. Ultimately, though, I ended up feeling enormously optimistic . No longer is there just one way to approach sex, love, or relationships that is valued and appreciated.

People who, not so very long ago, may have wondered what was wrong with them now have a new answer: Nothing. People who secretly wondered why romantic relationships were valued above all others can now find validation for their perspective. Maybe they aren’t oddballs, but forward-looking, open-minded, democratic thinkers.

I’ll share definitions for 60 terms — just a sampling of the universe of possibilities that are out there. One of the most comprehensive sources I found was a glossary provided by the University of California at Davis. Unless I specifically mention one of the other sources I drew from, my definitions are from that glossary.

To try to make sense of the 60 terms, I’ve organized them into five sections. Other categorizations would have been possible.

- Sex vs. gender: What’s the difference? And what about sexual orientation vs. gender identity ?

- What is your sexual orientation?

- What kind of attraction do you feel toward other people?

- What is your orientation toward relationships?

- How do you value different relationships?

I. Sex vs. gender: what’s the difference? And what about sexual orientation vs. gender identity?

“Sex” and “gender” aren’t the same.

- Sex (1) is “a medically constructed category often assigned based on the appearance of the genitalia, either in ultrasound or at birth.”

- Gender (2) is “a social construct used to classify a person as a man, woman, or some other identity.”

Remember when we thought there were just two sexes, male and female, and everyone just assumed that anyone born male or female was, in fact, a male or a female? Now it is much more complicated. Here are some of the concepts that challenge those notions:

- Non-binary (3) : “A gender identity and experience that embraces a full universe of expressions and ways of being that resonate for an individual. It may be an active resistance to binary gender expectations and/or an intentional creation of new unbounded ideas of self within the world. For some people who identify as non-binary there may be overlap with other concepts and identities like gender expansive and gender non-conforming.”

- Gender expansive (4) : “An umbrella term used for individuals who broaden their own culture’s commonly held definitions of gender, including expectations for its expression, identities, roles, and/or other perceived gender norms. Gender expansive individuals include those who identify as transgender , as well as anyone else whose gender in some way is seen to be stretching the surrounding society’s notion of gender.”

- Gender non-conforming (5) : “People who do not subscribe to gender expressions or roles expected of them by society.”

- Gender fluid (6) : “A person whose gender identification and presentation shifts, whether within or outside of societal, gender-based expectations. Being fluid in motion between two or more genders.”

- Bigender (7) : “Having two genders, exhibiting cultural characteristics of masculine and feminine roles.”

- Gender queer (8) : “A person whose gender identity and/or gender expression falls outside of the dominant societal norm for their assigned sex, is beyond genders, or is some combination of them.”

- Polygender (9) or Pangender (10) : “Exhibiting characteristics of multiple genders, deliberately refuting the concept of only two genders.”

- Neutrois (11) : “A non-binary gender identity that falls under the genderqueer or transgender umbrellas. There is no one definition of Neutrois, since each person that self-identifies as such experiences their gender differently. The most common ones are: Neutral-gender (12), Null-gender (13), Neither male nor female (14), Genderless (15) and/or Agender (16) .”

At Aeon , Rebecca Reilly-Cooper challenged the notion that gender is a spectrum . At Vox , 12 people explained why the male/female binary doesn’t work for them .

Sexual orientation and gender identity aren’t the same.

- Gender identity (17) : When you say that you are a man or a woman, you are describing your gender identity. Gender identity is “a sense of one’s self as trans,* genderqueer, woman, man, or some other identity, which may or may not correspond with the sex and gender one is assigned at birth.” (For more on trans* and genderqueer, see the section below, “What is your sexual orientation?”) Transgender is a gender orientation; it is also included in the list of letters referring to sexual orientations.

- Sexual orientation (18) : “an enduring emotional, romantic, sexual or affectional attraction or non-attraction to other people.”

II. What is your sexual orientation?

If you are old enough, you may remember a time when “straight” and “gay” (or heterosexual and homosexual) covered all the sexual orientations that got any attention . Gay people were often described as queer (and worse) when the word was still solely a pejorative.

The terms then expanded to include LGBT : lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. A lesbian (19) is “a woman whose primary sexual and affectional orientation is toward people of the same gender.” Although “gay” (20) has often been used to refer to men who are attracted to other men, it is also used more broadly to refer to anyone attracted to someone of the same sex. Bisexuals (21) are attracted to both men and women, though not always to the same degree. Transgender (22) people are also called “trans” (23) or “trans*” (24) (the asterisk “indicates the option to fill in the appropriate label, i.e., Trans man”). The term “describes a wide range of identities and experiences of people whose gender identity and/or expression differs from conventional expectations based on their assigned sex at birth.”

Trans Man and Trans Woman are further explained by the Resource Center at the University of California at San Diego:

- Trans Man/Trans Male (25) : “A female-to-male (FTM) transgender person who was assigned female at birth, but whose gender identity is that of a man.” FTM is sometimes expressed as F2M.

- Trans Woman/Trans Female (26) : “A male-to-female (MTF) transgender person who was assigned male at birth, but whose gender identity is that of a woman.” MTF is sometimes expressed as M2F.

If you are not transgender, you may think that you don’t need a special term. But you have one. You are cisgender (28) : “a gender identity, or performance in a gender role, that society deems to match the person’s assigned sex at birth. The prefix cis- means ‘on this side of’ or ‘not across’.”

The list of letters has continued to expand. The letters added most often are QIA, giving us LGBTQIA .

- Q stands for Queer or for Questioning.

- Queer (29) is a broad label, which can refer to “people whose gender, gender expression and/or sexuality do not conform to dominant expectations.” It is sometimes used even more broadly to refer to “not fitting into norms” of all sorts, including size, physical abilities, and more.

- Questioning (30) is “the process of exploring one’s own gender identity, gender expression, and/or sexual orientation.”

- I is for Intersex (31) : “People who naturally (that is, without any medical intervention) develop primary or secondary sex characteristics that do not fit neatly into society's definitions of male or female… Hermaphrodite (32) is an outdated and inaccurate term that has been used to describe intersex people in the past.”

[Another A word is Allosexual, which is very different from Asexual. Allosexual (36) is “a sexual orientation generally characterized by feeling sexual attraction or a desire for partnered sexuality.”]

[Still another A word — one that does not describe a sexual orientation — is ally. Allyship (37) is “the action of working to end oppression through support of, and as an advocate with and for, a group other than one’s own.”]

There’s more. Among the other letters sometimes added to the list are P and K, giving us LGBTQIAPK .

- P can refer to Pansexual (or Omnisexual) or Polyamorous .

- Pansexual (38) and Omnisexual (39) are “terms used to describe people who have romantic, sexual or affectionate desire for people of all genders and sexes.”

- Polyamory (40) “denotes consensually being in/open to multiple loving relationships at the same time. Some polyamorists (polyamorous people) consider ‘poly’ to be a relationship orientation. Sometimes used as an umbrella term for all forms of ethical, consensual, and loving non-monogamy.”

- K stands for Kink (41) . According to Role/Reboot , “‘K’ would cover those who practice bondage and discipline, dominance-submission and/or sado-masochism, as well as those with an incredibly diverse set of fetishes and preferences.” If you are rolling your eyes, consider this: “According to survey data, around 15% of adults engage in some form of consensual sexual activity along the ‘kink’ spectrum. This is a higher percentage than those who identify as gay or lesbian.”

Not everyone identifies as either sexual or asexual. Some consider asexuality as a spectrum that includes, for example, demisexuals and greysexuals. These definitions are from AVEN :

- Demisexual (42) : “Someone who can only experience sexual attraction after an emotional bond has been formed. This bond does not have to be romantic in nature.”

- Gray-asexual (gray-a) (43) or gray-sexual (44) : “Someone who identifies with the area between asexuality and sexuality, for example because they experience sexual attraction very rarely, only under specific circumstances, or of an intensity so low that it's ignorable.” (Colloquially, sometimes called grey-ace (45) .)

There is also more than one variety of polyamory. An important example is solo polyamory. At Solopoly , Amy Gahran describes it this way:

- Solo polyamory (46) : “What distinguishes solo poly people is that we generally do not have intimate relationships which involve (or are heading toward) primary-style merging of life infrastructure or identity along the lines of the traditional social relationship escalator. For instance, we generally don’t share a home or finances with any intimate partners. Similarly, solo poly people generally don’t identify very strongly as part of a couple (or triad etc.); we prefer to operate and present ourselves as individuals.” As Kristen Bernhardt pointed out in her thesis, solo poly people often say: “I am my own primary partner.”

(For a definition of “relationship elevator,” see the section below, “What is your orientation toward relationships?”)

III. What kind of attraction do you feel toward other people?

Interpersonal attraction is not just sexual. AVEN lists these different kinds of attraction (47) (“emotional force that draws people together”):

- Aesthetic attraction (48) : “Attraction to someone’s appearance, without it being romantic or sexual.”

- Romantic attraction (49) : “Desire of being romantically involved with another person.”

- Sensual attraction (50) : “Desire to have physical non-sexual contact with someone else, like affectionate touching.”

- Sexual attraction (51) : “Desire to have sexual contact with someone else, to share our sexuality with them.”

Asexual is the term used for people who do not feel sexual attraction. Another term, aromantic, describes something different. According to the AVEN wiki :

- Aromantic (52) : “A person who experiences little or no romantic attraction to others. Where romantic people have an emotional need to be with another person in a romantic relationship, aromantics are often satisfied with friendships and other non-romantic relationships.” (Want to know more? Check out these five myths about aromanticism from Buzzfeed .)

People who experience romantic attraction have crushes. Aromantics have squishes. Again, from the AVEN wiki :

- Squish (53) : “Strong desire for some kind of platonic (nonsexual, nonromantic) connection to another person. The concept of a squish is similar in nature to the idea of a ‘friend crush.’ A squish can be towards anyone of any gender and a person may also have many squishes, all of which may be active.”

IV. What is your orientation toward relationships? (For example, do you prefer monogamy? Do you think your relationships should progress in a certain way?)

Many of the alternatives to monogamy fit under the umbrella term of “ethical non-monogamy.”

- Monogamy (54) : “Having only one intimate partner at a time.”

- Consensual non-monogamy ( or ethical non-monogamy) (55) : “all the ways that you can consciously, with agreement and consent from all involved, explore love and sex with multiple people.” (The definition is from Gracie X, who explores six varieties here . Polyamory is just one of them.)

According to the conventional wisdom , romantic relationships are expected to progress in a certain way. That’s called the “ relationship escalator .” Amy Gahran describes it this way:

- Relationship escalator (56) : “The default set of societal expectations for intimate relationships. Partners follow a progressive set of steps, each with visible markers, toward a clear goal. The goal at the top of the Escalator is to achieve a permanently monogamous (sexually and romantically exclusive between two people), cohabitating marriage — legally sanctioned if possible. In many cases, buying a house and having kids is also part of the goal. Partners are expected to remain together at the top of the Escalator until death. The Escalator is the standard by which most people gauge whether a developing intimate relationship is significant, ‘serious,’ good, healthy, committed or worth pursuing or continuing.”

V. How do you value different relationships?

Do you think that everyone should be in a romantic relationship, that everyone wants to be in a romantic relationship, and that such a relationship is more important than any other? Thanks to the philosopher Elizabeth Brake , there’s a name for that assumption, amatonormativity . Importantly, amatonormativity is an assumption, not a fact. A related concept is mononormativity. (The definition below is Robin Bauer’s, as described in Kristen Bernhardt’s thesis.) In the same family of concepts is heteronormativity. (Definition below is from Miriam-Webster .) An entirely different way of thinking about relationships has been described by Andie Nordgren in her concept of “relationship anarchy.”

- Amatonormativity (57) : “The assumption that a central, exclusive, amorous relationship is normal for humans, in that it is a universally shared goal, and that such a relationship is normative, in the sense that it should be aimed at in preference to other relationship types.” (Drake Baer’s discussion of the concept in New York magazine is excellent.)

- Mononormativity (58) : “Based on the taken for granted allegation that monogamy and couple-shaped arranged relationships are the principle of social relations per se, an essential foundation of human existence and the elementary, almost natural pattern of living together.”

- Heteronormative (59) : “Of, relating to, or based on the attitude that heterosexuality is the only normal and natural expression of sexuality.”

- Relationship anarchy (60) : “Relationship anarchists are often highly critical of conventional standards that prioritize romantic and sex-based relationships over non-sexual or non-romantic relationships. Instead, RA seeks to eliminate specific distinctions between or hierarchical valuations of friendship versus love-based relationships, so that love-based relationships are no more valuable than are platonic friendships.”

Bella DePaulo, Ph.D. , an expert on single people, is the author of Single at Heart and other books. She is an Academic Affiliate in Psychological & Brain Sciences, UCSB.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Feminist Perspectives on Sex and Gender

Feminism is said to be the movement to end women’s oppression (hooks 2000, 26). One possible way to understand ‘woman’ in this claim is to take it as a sex term: ‘woman’ picks out human females and being a human female depends on various biological and anatomical features (like genitalia). Historically many feminists have understood ‘woman’ differently: not as a sex term, but as a gender term that depends on social and cultural factors (like social position). In so doing, they distinguished sex (being female or male) from gender (being a woman or a man), although most ordinary language users appear to treat the two interchangeably. In feminist philosophy, this distinction has generated a lively debate. Central questions include: What does it mean for gender to be distinct from sex, if anything at all? How should we understand the claim that gender depends on social and/or cultural factors? What does it mean to be gendered woman, man, or genderqueer? This entry outlines and discusses distinctly feminist debates on sex and gender considering both historical and more contemporary positions.

1.1 Biological determinism

1.2 gender terminology, 2.1 gender socialisation, 2.2 gender as feminine and masculine personality, 2.3 gender as feminine and masculine sexuality, 3.1.1 particularity argument, 3.1.2 normativity argument, 3.2 is sex classification solely a matter of biology, 3.3 are sex and gender distinct, 3.4 is the sex/gender distinction useful, 4.1.1 gendered social series, 4.1.2 resemblance nominalism, 4.2.1 social subordination and gender, 4.2.2 gender uniessentialism, 4.2.3 gender as positionality, 5. beyond the binary, 6. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the sex/gender distinction..

The terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ mean different things to different feminist theorists and neither are easy or straightforward to characterise. Sketching out some feminist history of the terms provides a helpful starting point.

Most people ordinarily seem to think that sex and gender are coextensive: women are human females, men are human males. Many feminists have historically disagreed and have endorsed the sex/ gender distinction. Provisionally: ‘sex’ denotes human females and males depending on biological features (chromosomes, sex organs, hormones and other physical features); ‘gender’ denotes women and men depending on social factors (social role, position, behaviour or identity). The main feminist motivation for making this distinction was to counter biological determinism or the view that biology is destiny.

A typical example of a biological determinist view is that of Geddes and Thompson who, in 1889, argued that social, psychological and behavioural traits were caused by metabolic state. Women supposedly conserve energy (being ‘anabolic’) and this makes them passive, conservative, sluggish, stable and uninterested in politics. Men expend their surplus energy (being ‘katabolic’) and this makes them eager, energetic, passionate, variable and, thereby, interested in political and social matters. These biological ‘facts’ about metabolic states were used not only to explain behavioural differences between women and men but also to justify what our social and political arrangements ought to be. More specifically, they were used to argue for withholding from women political rights accorded to men because (according to Geddes and Thompson) “what was decided among the prehistoric Protozoa cannot be annulled by Act of Parliament” (quoted from Moi 1999, 18). It would be inappropriate to grant women political rights, as they are simply not suited to have those rights; it would also be futile since women (due to their biology) would simply not be interested in exercising their political rights. To counter this kind of biological determinism, feminists have argued that behavioural and psychological differences have social, rather than biological, causes. For instance, Simone de Beauvoir famously claimed that one is not born, but rather becomes a woman, and that “social discrimination produces in women moral and intellectual effects so profound that they appear to be caused by nature” (Beauvoir 1972 [original 1949], 18; for more, see the entry on Simone de Beauvoir ). Commonly observed behavioural traits associated with women and men, then, are not caused by anatomy or chromosomes. Rather, they are culturally learned or acquired.

Although biological determinism of the kind endorsed by Geddes and Thompson is nowadays uncommon, the idea that behavioural and psychological differences between women and men have biological causes has not disappeared. In the 1970s, sex differences were used to argue that women should not become airline pilots since they will be hormonally unstable once a month and, therefore, unable to perform their duties as well as men (Rogers 1999, 11). More recently, differences in male and female brains have been said to explain behavioural differences; in particular, the anatomy of corpus callosum, a bundle of nerves that connects the right and left cerebral hemispheres, is thought to be responsible for various psychological and behavioural differences. For instance, in 1992, a Time magazine article surveyed then prominent biological explanations of differences between women and men claiming that women’s thicker corpus callosums could explain what ‘women’s intuition’ is based on and impair women’s ability to perform some specialised visual-spatial skills, like reading maps (Gorman 1992). Anne Fausto-Sterling has questioned the idea that differences in corpus callosums cause behavioural and psychological differences. First, the corpus callosum is a highly variable piece of anatomy; as a result, generalisations about its size, shape and thickness that hold for women and men in general should be viewed with caution. Second, differences in adult human corpus callosums are not found in infants; this may suggest that physical brain differences actually develop as responses to differential treatment. Third, given that visual-spatial skills (like map reading) can be improved by practice, even if women and men’s corpus callosums differ, this does not make the resulting behavioural differences immutable. (Fausto-Sterling 2000b, chapter 5).

In order to distinguish biological differences from social/psychological ones and to talk about the latter, feminists appropriated the term ‘gender’. Psychologists writing on transsexuality were the first to employ gender terminology in this sense. Until the 1960s, ‘gender’ was often used to refer to masculine and feminine words, like le and la in French. However, in order to explain why some people felt that they were ‘trapped in the wrong bodies’, the psychologist Robert Stoller (1968) began using the terms ‘sex’ to pick out biological traits and ‘gender’ to pick out the amount of femininity and masculinity a person exhibited. Although (by and large) a person’s sex and gender complemented each other, separating out these terms seemed to make theoretical sense allowing Stoller to explain the phenomenon of transsexuality: transsexuals’ sex and gender simply don’t match.

Along with psychologists like Stoller, feminists found it useful to distinguish sex and gender. This enabled them to argue that many differences between women and men were socially produced and, therefore, changeable. Gayle Rubin (for instance) uses the phrase ‘sex/gender system’ in order to describe “a set of arrangements by which the biological raw material of human sex and procreation is shaped by human, social intervention” (1975, 165). Rubin employed this system to articulate that “part of social life which is the locus of the oppression of women” (1975, 159) describing gender as the “socially imposed division of the sexes” (1975, 179). Rubin’s thought was that although biological differences are fixed, gender differences are the oppressive results of social interventions that dictate how women and men should behave. Women are oppressed as women and “by having to be women” (Rubin 1975, 204). However, since gender is social, it is thought to be mutable and alterable by political and social reform that would ultimately bring an end to women’s subordination. Feminism should aim to create a “genderless (though not sexless) society, in which one’s sexual anatomy is irrelevant to who one is, what one does, and with whom one makes love” (Rubin 1975, 204).

In some earlier interpretations, like Rubin’s, sex and gender were thought to complement one another. The slogan ‘Gender is the social interpretation of sex’ captures this view. Nicholson calls this ‘the coat-rack view’ of gender: our sexed bodies are like coat racks and “provide the site upon which gender [is] constructed” (1994, 81). Gender conceived of as masculinity and femininity is superimposed upon the ‘coat-rack’ of sex as each society imposes on sexed bodies their cultural conceptions of how males and females should behave. This socially constructs gender differences – or the amount of femininity/masculinity of a person – upon our sexed bodies. That is, according to this interpretation, all humans are either male or female; their sex is fixed. But cultures interpret sexed bodies differently and project different norms on those bodies thereby creating feminine and masculine persons. Distinguishing sex and gender, however, also enables the two to come apart: they are separable in that one can be sexed male and yet be gendered a woman, or vice versa (Haslanger 2000b; Stoljar 1995).

So, this group of feminist arguments against biological determinism suggested that gender differences result from cultural practices and social expectations. Nowadays it is more common to denote this by saying that gender is socially constructed. This means that genders (women and men) and gendered traits (like being nurturing or ambitious) are the “intended or unintended product[s] of a social practice” (Haslanger 1995, 97). But which social practices construct gender, what social construction is and what being of a certain gender amounts to are major feminist controversies. There is no consensus on these issues. (See the entry on intersections between analytic and continental feminism for more on different ways to understand gender.)

2. Gender as socially constructed

One way to interpret Beauvoir’s claim that one is not born but rather becomes a woman is to take it as a claim about gender socialisation: females become women through a process whereby they acquire feminine traits and learn feminine behaviour. Masculinity and femininity are thought to be products of nurture or how individuals are brought up. They are causally constructed (Haslanger 1995, 98): social forces either have a causal role in bringing gendered individuals into existence or (to some substantial sense) shape the way we are qua women and men. And the mechanism of construction is social learning. For instance, Kate Millett takes gender differences to have “essentially cultural, rather than biological bases” that result from differential treatment (1971, 28–9). For her, gender is “the sum total of the parents’, the peers’, and the culture’s notions of what is appropriate to each gender by way of temperament, character, interests, status, worth, gesture, and expression” (Millett 1971, 31). Feminine and masculine gender-norms, however, are problematic in that gendered behaviour conveniently fits with and reinforces women’s subordination so that women are socialised into subordinate social roles: they learn to be passive, ignorant, docile, emotional helpmeets for men (Millett 1971, 26). However, since these roles are simply learned, we can create more equal societies by ‘unlearning’ social roles. That is, feminists should aim to diminish the influence of socialisation.

Social learning theorists hold that a huge array of different influences socialise us as women and men. This being the case, it is extremely difficult to counter gender socialisation. For instance, parents often unconsciously treat their female and male children differently. When parents have been asked to describe their 24- hour old infants, they have done so using gender-stereotypic language: boys are describes as strong, alert and coordinated and girls as tiny, soft and delicate. Parents’ treatment of their infants further reflects these descriptions whether they are aware of this or not (Renzetti & Curran 1992, 32). Some socialisation is more overt: children are often dressed in gender stereotypical clothes and colours (boys are dressed in blue, girls in pink) and parents tend to buy their children gender stereotypical toys. They also (intentionally or not) tend to reinforce certain ‘appropriate’ behaviours. While the precise form of gender socialization has changed since the onset of second-wave feminism, even today girls are discouraged from playing sports like football or from playing ‘rough and tumble’ games and are more likely than boys to be given dolls or cooking toys to play with; boys are told not to ‘cry like a baby’ and are more likely to be given masculine toys like trucks and guns (for more, see Kimmel 2000, 122–126). [ 1 ]

According to social learning theorists, children are also influenced by what they observe in the world around them. This, again, makes countering gender socialisation difficult. For one, children’s books have portrayed males and females in blatantly stereotypical ways: for instance, males as adventurers and leaders, and females as helpers and followers. One way to address gender stereotyping in children’s books has been to portray females in independent roles and males as non-aggressive and nurturing (Renzetti & Curran 1992, 35). Some publishers have attempted an alternative approach by making their characters, for instance, gender-neutral animals or genderless imaginary creatures (like TV’s Teletubbies). However, parents reading books with gender-neutral or genderless characters often undermine the publishers’ efforts by reading them to their children in ways that depict the characters as either feminine or masculine. According to Renzetti and Curran, parents labelled the overwhelming majority of gender-neutral characters masculine whereas those characters that fit feminine gender stereotypes (for instance, by being helpful and caring) were labelled feminine (1992, 35). Socialising influences like these are still thought to send implicit messages regarding how females and males should act and are expected to act shaping us into feminine and masculine persons.

Nancy Chodorow (1978; 1995) has criticised social learning theory as too simplistic to explain gender differences (see also Deaux & Major 1990; Gatens 1996). Instead, she holds that gender is a matter of having feminine and masculine personalities that develop in early infancy as responses to prevalent parenting practices. In particular, gendered personalities develop because women tend to be the primary caretakers of small children. Chodorow holds that because mothers (or other prominent females) tend to care for infants, infant male and female psychic development differs. Crudely put: the mother-daughter relationship differs from the mother-son relationship because mothers are more likely to identify with their daughters than their sons. This unconsciously prompts the mother to encourage her son to psychologically individuate himself from her thereby prompting him to develop well defined and rigid ego boundaries. However, the mother unconsciously discourages the daughter from individuating herself thereby prompting the daughter to develop flexible and blurry ego boundaries. Childhood gender socialisation further builds on and reinforces these unconsciously developed ego boundaries finally producing feminine and masculine persons (1995, 202–206). This perspective has its roots in Freudian psychoanalytic theory, although Chodorow’s approach differs in many ways from Freud’s.

Gendered personalities are supposedly manifested in common gender stereotypical behaviour. Take emotional dependency. Women are stereotypically more emotional and emotionally dependent upon others around them, supposedly finding it difficult to distinguish their own interests and wellbeing from the interests and wellbeing of their children and partners. This is said to be because of their blurry and (somewhat) confused ego boundaries: women find it hard to distinguish their own needs from the needs of those around them because they cannot sufficiently individuate themselves from those close to them. By contrast, men are stereotypically emotionally detached, preferring a career where dispassionate and distanced thinking are virtues. These traits are said to result from men’s well-defined ego boundaries that enable them to prioritise their own needs and interests sometimes at the expense of others’ needs and interests.

Chodorow thinks that these gender differences should and can be changed. Feminine and masculine personalities play a crucial role in women’s oppression since they make females overly attentive to the needs of others and males emotionally deficient. In order to correct the situation, both male and female parents should be equally involved in parenting (Chodorow 1995, 214). This would help in ensuring that children develop sufficiently individuated senses of selves without becoming overly detached, which in turn helps to eradicate common gender stereotypical behaviours.

Catharine MacKinnon develops her theory of gender as a theory of sexuality. Very roughly: the social meaning of sex (gender) is created by sexual objectification of women whereby women are viewed and treated as objects for satisfying men’s desires (MacKinnon 1989). Masculinity is defined as sexual dominance, femininity as sexual submissiveness: genders are “created through the eroticization of dominance and submission. The man/woman difference and the dominance/submission dynamic define each other. This is the social meaning of sex” (MacKinnon 1989, 113). For MacKinnon, gender is constitutively constructed : in defining genders (or masculinity and femininity) we must make reference to social factors (see Haslanger 1995, 98). In particular, we must make reference to the position one occupies in the sexualised dominance/submission dynamic: men occupy the sexually dominant position, women the sexually submissive one. As a result, genders are by definition hierarchical and this hierarchy is fundamentally tied to sexualised power relations. The notion of ‘gender equality’, then, does not make sense to MacKinnon. If sexuality ceased to be a manifestation of dominance, hierarchical genders (that are defined in terms of sexuality) would cease to exist.

So, gender difference for MacKinnon is not a matter of having a particular psychological orientation or behavioural pattern; rather, it is a function of sexuality that is hierarchal in patriarchal societies. This is not to say that men are naturally disposed to sexually objectify women or that women are naturally submissive. Instead, male and female sexualities are socially conditioned: men have been conditioned to find women’s subordination sexy and women have been conditioned to find a particular male version of female sexuality as erotic – one in which it is erotic to be sexually submissive. For MacKinnon, both female and male sexual desires are defined from a male point of view that is conditioned by pornography (MacKinnon 1989, chapter 7). Bluntly put: pornography portrays a false picture of ‘what women want’ suggesting that women in actual fact are and want to be submissive. This conditions men’s sexuality so that they view women’s submission as sexy. And male dominance enforces this male version of sexuality onto women, sometimes by force. MacKinnon’s thought is not that male dominance is a result of social learning (see 2.1.); rather, socialization is an expression of power. That is, socialized differences in masculine and feminine traits, behaviour, and roles are not responsible for power inequalities. Females and males (roughly put) are socialised differently because there are underlying power inequalities. As MacKinnon puts it, ‘dominance’ (power relations) is prior to ‘difference’ (traits, behaviour and roles) (see, MacKinnon 1989, chapter 12). MacKinnon, then, sees legal restrictions on pornography as paramount to ending women’s subordinate status that stems from their gender.

3. Problems with the sex/gender distinction

3.1 is gender uniform.

The positions outlined above share an underlying metaphysical perspective on gender: gender realism . [ 2 ] That is, women as a group are assumed to share some characteristic feature, experience, common condition or criterion that defines their gender and the possession of which makes some individuals women (as opposed to, say, men). All women are thought to differ from all men in this respect (or respects). For example, MacKinnon thought that being treated in sexually objectifying ways is the common condition that defines women’s gender and what women as women share. All women differ from all men in this respect. Further, pointing out females who are not sexually objectified does not provide a counterexample to MacKinnon’s view. Being sexually objectified is constitutive of being a woman; a female who escapes sexual objectification, then, would not count as a woman.

One may want to critique the three accounts outlined by rejecting the particular details of each account. (For instance, see Spelman [1988, chapter 4] for a critique of the details of Chodorow’s view.) A more thoroughgoing critique has been levelled at the general metaphysical perspective of gender realism that underlies these positions. It has come under sustained attack on two grounds: first, that it fails to take into account racial, cultural and class differences between women (particularity argument); second, that it posits a normative ideal of womanhood (normativity argument).

Elizabeth Spelman (1988) has influentially argued against gender realism with her particularity argument. Roughly: gender realists mistakenly assume that gender is constructed independently of race, class, ethnicity and nationality. If gender were separable from, for example, race and class in this manner, all women would experience womanhood in the same way. And this is clearly false. For instance, Harris (1993) and Stone (2007) criticise MacKinnon’s view, that sexual objectification is the common condition that defines women’s gender, for failing to take into account differences in women’s backgrounds that shape their sexuality. The history of racist oppression illustrates that during slavery black women were ‘hypersexualised’ and thought to be always sexually available whereas white women were thought to be pure and sexually virtuous. In fact, the rape of a black woman was thought to be impossible (Harris 1993). So, (the argument goes) sexual objectification cannot serve as the common condition for womanhood since it varies considerably depending on one’s race and class. [ 3 ]

For Spelman, the perspective of ‘white solipsism’ underlies gender realists’ mistake. They assumed that all women share some “golden nugget of womanness” (Spelman 1988, 159) and that the features constitutive of such a nugget are the same for all women regardless of their particular cultural backgrounds. Next, white Western middle-class feminists accounted for the shared features simply by reflecting on the cultural features that condition their gender as women thus supposing that “the womanness underneath the Black woman’s skin is a white woman’s, and deep down inside the Latina woman is an Anglo woman waiting to burst through an obscuring cultural shroud” (Spelman 1988, 13). In so doing, Spelman claims, white middle-class Western feminists passed off their particular view of gender as “a metaphysical truth” (1988, 180) thereby privileging some women while marginalising others. In failing to see the importance of race and class in gender construction, white middle-class Western feminists conflated “the condition of one group of women with the condition of all” (Spelman 1988, 3).

Betty Friedan’s (1963) well-known work is a case in point of white solipsism. [ 4 ] Friedan saw domesticity as the main vehicle of gender oppression and called upon women in general to find jobs outside the home. But she failed to realize that women from less privileged backgrounds, often poor and non-white, already worked outside the home to support their families. Friedan’s suggestion, then, was applicable only to a particular sub-group of women (white middle-class Western housewives). But it was mistakenly taken to apply to all women’s lives — a mistake that was generated by Friedan’s failure to take women’s racial and class differences into account (hooks 2000, 1–3).

Spelman further holds that since social conditioning creates femininity and societies (and sub-groups) that condition it differ from one another, femininity must be differently conditioned in different societies. For her, “females become not simply women but particular kinds of women” (Spelman 1988, 113): white working-class women, black middle-class women, poor Jewish women, wealthy aristocratic European women, and so on.

This line of thought has been extremely influential in feminist philosophy. For instance, Young holds that Spelman has definitively shown that gender realism is untenable (1997, 13). Mikkola (2006) argues that this isn’t so. The arguments Spelman makes do not undermine the idea that there is some characteristic feature, experience, common condition or criterion that defines women’s gender; they simply point out that some particular ways of cashing out what defines womanhood are misguided. So, although Spelman is right to reject those accounts that falsely take the feature that conditions white middle-class Western feminists’ gender to condition women’s gender in general, this leaves open the possibility that women qua women do share something that defines their gender. (See also Haslanger [2000a] for a discussion of why gender realism is not necessarily untenable, and Stoljar [2011] for a discussion of Mikkola’s critique of Spelman.)

Judith Butler critiques the sex/gender distinction on two grounds. They critique gender realism with their normativity argument (1999 [original 1990], chapter 1); they also hold that the sex/gender distinction is unintelligible (this will be discussed in section 3.3.). Butler’s normativity argument is not straightforwardly directed at the metaphysical perspective of gender realism, but rather at its political counterpart: identity politics. This is a form of political mobilization based on membership in some group (e.g. racial, ethnic, cultural, gender) and group membership is thought to be delimited by some common experiences, conditions or features that define the group (Heyes 2000, 58; see also the entry on Identity Politics ). Feminist identity politics, then, presupposes gender realism in that feminist politics is said to be mobilized around women as a group (or category) where membership in this group is fixed by some condition, experience or feature that women supposedly share and that defines their gender.

Butler’s normativity argument makes two claims. The first is akin to Spelman’s particularity argument: unitary gender notions fail to take differences amongst women into account thus failing to recognise “the multiplicity of cultural, social, and political intersections in which the concrete array of ‘women’ are constructed” (Butler 1999, 19–20). In their attempt to undercut biologically deterministic ways of defining what it means to be a woman, feminists inadvertently created new socially constructed accounts of supposedly shared femininity. Butler’s second claim is that such false gender realist accounts are normative. That is, in their attempt to fix feminism’s subject matter, feminists unwittingly defined the term ‘woman’ in a way that implies there is some correct way to be gendered a woman (Butler 1999, 5). That the definition of the term ‘woman’ is fixed supposedly “operates as a policing force which generates and legitimizes certain practices, experiences, etc., and curtails and delegitimizes others” (Nicholson 1998, 293). Following this line of thought, one could say that, for instance, Chodorow’s view of gender suggests that ‘real’ women have feminine personalities and that these are the women feminism should be concerned about. If one does not exhibit a distinctly feminine personality, the implication is that one is not ‘really’ a member of women’s category nor does one properly qualify for feminist political representation.

Butler’s second claim is based on their view that“[i]dentity categories [like that of women] are never merely descriptive, but always normative, and as such, exclusionary” (Butler 1991, 160). That is, the mistake of those feminists Butler critiques was not that they provided the incorrect definition of ‘woman’. Rather, (the argument goes) their mistake was to attempt to define the term ‘woman’ at all. Butler’s view is that ‘woman’ can never be defined in a way that does not prescribe some “unspoken normative requirements” (like having a feminine personality) that women should conform to (Butler 1999, 9). Butler takes this to be a feature of terms like ‘woman’ that purport to pick out (what they call) ‘identity categories’. They seem to assume that ‘woman’ can never be used in a non-ideological way (Moi 1999, 43) and that it will always encode conditions that are not satisfied by everyone we think of as women. Some explanation for this comes from Butler’s view that all processes of drawing categorical distinctions involve evaluative and normative commitments; these in turn involve the exercise of power and reflect the conditions of those who are socially powerful (Witt 1995).

In order to better understand Butler’s critique, consider their account of gender performativity. For them, standard feminist accounts take gendered individuals to have some essential properties qua gendered individuals or a gender core by virtue of which one is either a man or a woman. This view assumes that women and men, qua women and men, are bearers of various essential and accidental attributes where the former secure gendered persons’ persistence through time as so gendered. But according to Butler this view is false: (i) there are no such essential properties, and (ii) gender is an illusion maintained by prevalent power structures. First, feminists are said to think that genders are socially constructed in that they have the following essential attributes (Butler 1999, 24): women are females with feminine behavioural traits, being heterosexuals whose desire is directed at men; men are males with masculine behavioural traits, being heterosexuals whose desire is directed at women. These are the attributes necessary for gendered individuals and those that enable women and men to persist through time as women and men. Individuals have “intelligible genders” (Butler 1999, 23) if they exhibit this sequence of traits in a coherent manner (where sexual desire follows from sexual orientation that in turn follows from feminine/ masculine behaviours thought to follow from biological sex). Social forces in general deem individuals who exhibit in coherent gender sequences (like lesbians) to be doing their gender ‘wrong’ and they actively discourage such sequencing of traits, for instance, via name-calling and overt homophobic discrimination. Think back to what was said above: having a certain conception of what women are like that mirrors the conditions of socially powerful (white, middle-class, heterosexual, Western) women functions to marginalize and police those who do not fit this conception.

These gender cores, supposedly encoding the above traits, however, are nothing more than illusions created by ideals and practices that seek to render gender uniform through heterosexism, the view that heterosexuality is natural and homosexuality is deviant (Butler 1999, 42). Gender cores are constructed as if they somehow naturally belong to women and men thereby creating gender dimorphism or the belief that one must be either a masculine male or a feminine female. But gender dimorphism only serves a heterosexist social order by implying that since women and men are sharply opposed, it is natural to sexually desire the opposite sex or gender.

Further, being feminine and desiring men (for instance) are standardly assumed to be expressions of one’s gender as a woman. Butler denies this and holds that gender is really performative. It is not “a stable identity or locus of agency from which various acts follow; rather, gender is … instituted … through a stylized repetition of [habitual] acts ” (Butler 1999, 179): through wearing certain gender-coded clothing, walking and sitting in certain gender-coded ways, styling one’s hair in gender-coded manner and so on. Gender is not something one is, it is something one does; it is a sequence of acts, a doing rather than a being. And repeatedly engaging in ‘feminising’ and ‘masculinising’ acts congeals gender thereby making people falsely think of gender as something they naturally are . Gender only comes into being through these gendering acts: a female who has sex with men does not express her gender as a woman. This activity (amongst others) makes her gendered a woman.

The constitutive acts that gender individuals create genders as “compelling illusion[s]” (Butler 1990, 271). Our gendered classification scheme is a strong pragmatic construction : social factors wholly determine our use of the scheme and the scheme fails to represent accurately any ‘facts of the matter’ (Haslanger 1995, 100). People think that there are true and real genders, and those deemed to be doing their gender ‘wrong’ are not socially sanctioned. But, genders are true and real only to the extent that they are performed (Butler 1990, 278–9). It does not make sense, then, to say of a male-to-female trans person that s/he is really a man who only appears to be a woman. Instead, males dressing up and acting in ways that are associated with femininity “show that [as Butler suggests] ‘being’ feminine is just a matter of doing certain activities” (Stone 2007, 64). As a result, the trans person’s gender is just as real or true as anyone else’s who is a ‘traditionally’ feminine female or masculine male (Butler 1990, 278). [ 5 ] Without heterosexism that compels people to engage in certain gendering acts, there would not be any genders at all. And ultimately the aim should be to abolish norms that compel people to act in these gendering ways.

For Butler, given that gender is performative, the appropriate response to feminist identity politics involves two things. First, feminists should understand ‘woman’ as open-ended and “a term in process, a becoming, a constructing that cannot rightfully be said to originate or end … it is open to intervention and resignification” (Butler 1999, 43). That is, feminists should not try to define ‘woman’ at all. Second, the category of women “ought not to be the foundation of feminist politics” (Butler 1999, 9). Rather, feminists should focus on providing an account of how power functions and shapes our understandings of womanhood not only in the society at large but also within the feminist movement.

Many people, including many feminists, have ordinarily taken sex ascriptions to be solely a matter of biology with no social or cultural dimension. It is commonplace to think that there are only two sexes and that biological sex classifications are utterly unproblematic. By contrast, some feminists have argued that sex classifications are not unproblematic and that they are not solely a matter of biology. In order to make sense of this, it is helpful to distinguish object- and idea-construction (see Haslanger 2003b for more): social forces can be said to construct certain kinds of objects (e.g. sexed bodies or gendered individuals) and certain kinds of ideas (e.g. sex or gender concepts). First, take the object-construction of sexed bodies. Secondary sex characteristics, or the physiological and biological features commonly associated with males and females, are affected by social practices. In some societies, females’ lower social status has meant that they have been fed less and so, the lack of nutrition has had the effect of making them smaller in size (Jaggar 1983, 37). Uniformity in muscular shape, size and strength within sex categories is not caused entirely by biological factors, but depends heavily on exercise opportunities: if males and females were allowed the same exercise opportunities and equal encouragement to exercise, it is thought that bodily dimorphism would diminish (Fausto-Sterling 1993a, 218). A number of medical phenomena involving bones (like osteoporosis) have social causes directly related to expectations about gender, women’s diet and their exercise opportunities (Fausto-Sterling 2005). These examples suggest that physiological features thought to be sex-specific traits not affected by social and cultural factors are, after all, to some extent products of social conditioning. Social conditioning, then, shapes our biology.