- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, purpose of the study, literature search and selection criteria, coding of the studies for exploration of moderators, decisions related to the computation of effect sizes.

- < Previous

The effectiveness of school-based sex education programs in the promotion of abstinent behavior: a meta-analysis

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Mónica Silva, The effectiveness of school-based sex education programs in the promotion of abstinent behavior: a meta-analysis, Health Education Research , Volume 17, Issue 4, August 2002, Pages 471–481, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/17.4.471

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This review presents the findings from controlled school-based sex education interventions published in the last 15 years in the US. The effects of the interventions in promoting abstinent behavior reported in 12 controlled studies were included in the meta-analysis. The results of the analysis indicated a very small overall effect of the interventions in abstinent behavior. Moderator analysis could only be pursued partially because of limited information in primary research studies. Parental participation in the program, age of the participants, virgin-status of the sample, grade level, percentage of females, scope of the implementation and year of publication of the study were associated with variations in effect sizes for abstinent behavior in univariate tests. However, only parental participation and percentage of females were significant in the weighted least-squares regression analysis. The richness of a meta-analytic approach appears limited by the quality of the primary research. Unfortunately, most of the research does not employ designs to provide conclusive evidence of program effects. Suggestions to address this limitation are provided.

Sexually active teenagers are a matter of serious concern. In the past decades many school-based programs have been designed for the sole purpose of delaying the initiation of sexual activity. There seems to be a growing consensus that schools can play an important role in providing youth with a knowledge base which may allow them to make informed decisions and help them shape a healthy lifestyle ( St Leger, 1999 ). The school is the only institution in regular contact with a sizable proportion of the teenage population ( Zabin and Hirsch, 1988 ), with virtually all youth attending it before they initiate sexual risk-taking behavior ( Kirby and Coyle, 1997 ).

Programs that promote abstinence have become particularly popular with school systems in the US ( Gilbert and Sawyer, 1994 ) and even with the federal government ( Sexual abstinence program has a $250 million price tag, 1997 ). These are referred to in the literature as abstinence-only or value-based programs ( Repucci and Herman, 1991 ). Other programs—designated in the literature as safer-sex, comprehensive, secular or abstinence-plus programs—additionally espouse the goal of increasing usage of effective contraception. Although abstinence-only and safer-sex programs differ in their underlying values and assumptions regarding the aims of sex education, both types of programs strive to foster decision-making and problem-solving skills in the belief that through adequate instruction adolescents will be better equipped to act responsibly in the heat of the moment ( Repucci and Herman, 1991 ). Nowadays most safer-sex programs encourage abstinence as a healthy lifestyle and many abstinence only programs have evolved into `abstinence-oriented' curricula that also include some information on contraception. For most programs currently implemented in the US, a delay in the initiation of sexual activity constitutes a positive and desirable outcome, since the likelihood of responsible sexual behavior increases with age ( Howard and Mitchell, 1993 ).

Even though abstinence is a valued outcome of school-based sex education programs, the effectiveness of such interventions in promoting abstinent behavior is still far from settled. Most of the articles published on the effectiveness of sex education programs follow the literary format of traditional narrative reviews ( Quinn, 1986 ; Kirby, 1989 , 1992 ; Visser and van Bilsen, 1994 ; Jacobs and Wolf, 1995 ; Kirby and Coyle, 1997 ). Two exceptions are the quantitative overviews by Frost and Forrest ( Frost and Forrest, 1995 ) and Franklin et al . ( Franklin et al ., 1997 ).

In the first review ( Frost and Forrest, 1995 ), the authors selected only five rigorously evaluated sex education programs and estimated their impact on delaying sexual initiation. They used non-standardized measures of effect sizes, calculated descriptive statistics to represent the overall effect of these programs and concluded that those selected programs delayed the initiation of sexual activity. In the second review, Franklin et al . conducted a meta-analysis of the published research of community-based and school-based adolescent pregnancy prevention programs and contrary to the conclusions forwarded by Frost and Forrest, these authors reported a non-significant effect of the programs on sexual activity ( Franklin et al ., 1997 ).

The discrepancy between these two quantitative reviews may result from the decision by Franklin et al . to include weak designs, which do not allow for reasonable causal inferences. However, given that recent evidence indicates that weaker designs yield higher estimates of intervention effects ( Guyatt et al ., 2000 ), the inclusion of weak designs should have translated into higher effects for the Franklin et al . review and not smaller. Given the discrepant results forwarded in these two recent quantitative reviews, there is a need to clarify the extent of the impact of school-based sex education in abstinent behavior and explore the specific features of the interventions that are associated to variability in effect sizes.

The present study consisted of a meta-analytic review of the research literature on the effectiveness of school-based sex education programs in the promotion of abstinent behavior implemented in the past 15 years in the US in the wake of the AIDS epidemic. The goals were to: (1) synthesize the effects of controlled school-based sex education interventions on abstinent behavior, (2) examine the variability in effects among studies and (3) explain the variability in effects between studies in terms of selected moderator variables.

The first step was to locate as many studies conducted in the US as possible that dealt with the evaluation of sex education programs and which measured abstinent behavior subsequent to an intervention.

The primary sources for locating studies were four reference database systems: ERIC, PsychLIT, MEDLINE and the Social Science Citation Index. Branching from the bibliographies and reference lists in articles located through the original search provided another source for locating studies.

The process for the selection of studies was guided by four criteria, some of which have been employed by other authors as a way to orient and confine the search to the relevant literature ( Kirby et al ., 1994 ). The criteria to define eligibility of studies were the following.

Interventions had to be geared to normal adolescent populations attending public or private schools in the US and report on some measure of abstinent behavior: delay in the onset of intercourse, reduction in the frequency of intercourse or reduction in the number of sexual partners. Studies that reported on interventions designed for cognitively handicapped, delinquent, school dropouts, emotionally disturbed or institutionalized adolescents were excluded from the present review since they address a different population with different needs and characteristics. Community interventions which recruited participants from clinical or out-of-school populations were also eliminated for the same reasons.

Studies had to be either experimental or quasi-experimental in nature, excluding three designs that do not permit strong tests of causal hypothesis: the one group post-test-only design, the post-test-only design with non-equivalent groups and the one group pre-test–post-test design ( Cook and Campbell, 1979 ). The presence of an independent and comparable `no intervention' control group—in demographic variables and measures of sexual activity in the baseline—was required for a study to be included in this review.

Studies had to be published between January 1985 and July 2000. A time period restriction was imposed because of cultural changes that occur in society—such as the AIDS epidemic—which might significantly impact the adolescent cohort and alter patterns of behavior and consequently the effects of sex education interventions.

Five pairs of publications were detected which may have used the same database (or two databases which were likely to contain non-independent cases) ( Levy et al ., 1995 / Weeks et al ., 1995 ; Barth et al ., 1992 / Kirby et al ., 1991 /Christoper and Roosa, 1990/ Roosa and Christopher, 1990 and Jorgensen, 1991 / Jorgensen et al ., 1993 ). Only one effect size from each pair of articles was included to avoid the possibility of data dependence.

The exploration of study characteristics or features that may be related to variations in the magnitude of effect sizes across studies is referred to as moderator analysis. A moderator variable is one that informs about the circumstances under which the magnitude of effect sizes vary ( Miller and Pollock, 1994 ). The information retrieved from the articles for its potential inclusion as moderators in the data analysis was categorized in two domains: demographic characteristics of the participants in the sex education interventions and characteristics of the program.

Demographic characteristics included the following variables: the percentages of females, the percentage of whites, the virginity status of participants, mean (or median) age and a categorization of the predominant socioeconomic status of participating subjects (low or middle class) as reported by the authors of the primary study.

In terms of the characteristics of the programs, the features coded were: the type of program (whether the intervention was comprehensive/safer-sex or abstinence-oriented), the type of monitor who delivered the intervention (teacher/adult monitor or peer), the length of the program in hours, the scope of the implementation (large-scale versus small-scale trial), the time elapsed between the intervention and the post-intervention outcome measure (expressed as number of days), and whether parental participation (beyond consent) was a component of the intervention.

The type of sex education intervention was defined as abstinence-oriented if the explicit aim was to encourage abstinence as the primary method of protection against sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy, either totally excluding units on contraceptive methods or, if including contraception, portraying it as a less effective method than abstinence. An intervention was defined as comprehensive or safer-sex if it included a strong component on the benefits of use of contraceptives as a legitimate alternative method to abstinence for avoiding pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases.

A study was considered to be a large-scale trial if the intervention group consisted of more than 500 students.

Finally, year of publication was also analyzed to assess whether changes in the effectiveness of programs across time had occurred.

The decision to record information on all the above-mentioned variables for their potential role as moderators of effect sizes was based in part on theoretical considerations and in part on the empirical evidence of the relevance of such variables in explaining the effectiveness of educational interventions. A limitation to the coding of these and of other potentially relevant and interesting moderator variables was the scantiness of information provided by the authors of primary research. Not all studies described the features of interest for this meta-analysis. For parental participation, no missing values were present because a decision was made to code all interventions which did not specifically report that parents had participated—either through parent–youth sessions or homework assignments—as non-participation. However, for the rest of the variables, no similar assumptions seemed appropriate, and therefore if no pertinent data were reported for a given variable, it was coded as missing (see Table I ).

Once the pool of studies which met the inclusion criteria was located, studies were examined in an attempt to retrieve the size of the effect associated with each intervention. Since most of the studies did not report any effect size, it had to be estimated based on the significance level and inferential statistics with formulae provided by Rosenthal ( Rosenthal, 1991 ) and Holmes ( Holmes; 1984 ). When provided, the exact value for the test statistic or the exact probability was used in the calculation of the effect size.

Alternative methods to deal with non-independent effect sizes were not employed since these are more complex and require estimates of the covariance structure among the correlated effect sizes. According to Matt and Cook such estimates may be difficult—if not impossible—to obtain due to missing information in primary studies ( Matt and Cook, 1994 ).

Analyses of the effect sizes were conducted utilizing the D-STAT software ( Johnson, 1989 ). The sample sizes used for the overall effect size analysis corresponded to the actual number used to estimate the effects of interest, which was often less than the total sample of the study. Occasionally the actual sample sizes were not provided by the authors of primary research, but could be estimated from the degrees of freedom reported for the statistical tests.

The effect sizes were calculated from means and pooled standard deviations, t -tests, χ 2 , significance levels or from proportions, depending on the nature of the information reported by the authors of primary research. As recommended by Rosenthal, if results were reported simply as being `non-significant' a conservative estimate of the effect size was included, assuming P = 0.50, which corresponds to an effect size of zero ( Rosenthal, 1991 ). The overall measure of effect size reported was the corrected d statistic ( Hedges and Olkin, 1985 ). These authors recommend this measure since it does not overestimate the population effect size, especially in the case when sample sizes are small.

The homogeneity of effect sizes was examined to determine whether the studies shared a common effect size. Testing for homogeneity required the calculation of a homogeneity statistic, Q . If all studies share the same population effect size, Q follows an asymptotic χ 2 distribution with k – 1 degrees of freedom, where k is the number of effect sizes. For the purposes of this review the probability level chosen for significance testing was 0.10, due to the fact that the relatively small number of effect sizes available for the analysis limits the power to detect actual departures from homogeneity. Rejection of the hypothesis of homogeneity signals that the group of effect sizes is more variable than one would expect based on sampling variation and that one or more moderator variables may be present ( Hall et al ., 1994 ).

To examine the relationship between the study characteristics included as potential moderators and the magnitude of effect sizes, both categorical and continuous univariate tests were run. Categorical tests assess differences in effect sizes between subgroups established by dividing studies into classes based on study characteristics. Hedges and Olkin presented an extension of the Q statistic to test for homogeneity of effect sizes between classes ( Q B ) and within classes ( Q W ) ( Hedges and Olkin, 1985 ). The relationship between the effect sizes and continuous predictors was assessed using a procedure described by Rosenthal and Rubin which tests for linearity between effect sizes and predictors ( Rosenthal and Rubin, 1982 ).

Q E provides the test for model specification, when the number of studies is larger than the number of predictors. Under those conditions, Q E follows an approximate χ 2 distribution with k – p – 1 degrees of freedom, where k is the number of effect sizes and p is the number of regressors ( Hedges and Olkin, 1985 ).

The search for school-based sex education interventions resulted in 12 research studies that complied with the criteria to be included in the review and for which effect sizes could be estimated.

The overall effect size ( d +) estimated from these studies was 0.05 and the 95% confidence interval about the mean included a lower bound of 0.01 to a high bound of 0.09, indicating a very minimal overall effect size. Table II presents the effect size of each study ( d i ) along with its 95% confidence interval and the overall estimate of the effect size. Homogeneity testing indicated the presence of variability among effect sizes ( Q (11) = 35.56; P = 0.000).

An assessment of interaction effects among significant moderators could not be explored since it would have required partitioning of the studies according to a first variable and testing of the second within the partitioned categories. The limited number of effect sizes precluded such analysis.

Parental participation appeared to moderate the effects of sex education on abstinence as indicated by the significant Q test between groups ( Q B(1) = 5.06; P = 0.025), as shown in Table III . Although small in magnitude ( d = 0.24), the point estimate for the mean weighted effect size associated with programs with parental participation appears substantially larger than the mean associated with those where parents did not participate ( d = 0.04). The confidence interval for parent participation does not include zero, thus indicating a small but positive effect. Controlling for parental participation appears to translate into homogeneous classes of effect sizes for programs that include parents, but not for those where parents did not participate ( Q W(9) = 28.94; P = 0.001) meaning that the effect sizes were not homogeneous within this class.

Virginity status of the sample was also a significant predictor of the variability among effect sizes ( Q B(1) = 3.47 ; P = 0.06). The average effect size calculated for virgins-only was larger than the one calculated for virgins and non-virgins ( d = 0.09 and d = 0.01, respectively). Controlling for virginity status translated into homogeneous classes for virgins and non-virgins although not for the virgins-only class ( Q W(5) = 27.09; P = 0.000).

The scope of the implementation also appeared to moderate the effects of the interventions on abstinent behavior. The average effect size calculated for small-scale intervention was significantly higher than that for large-scale interventions ( d = 0.26 and d = 0.01, respectively). The effects corresponding to the large-scale category were homogeneous but this was not the case for the small-scale class, where heterogeneity was detected ( Q W(4) = 14.71; P = 0.01)

For all three significant categorical predictors, deletion of one outlier ( Howard and McCabe, 1990 ) resulted in homogeneity among the effect sizes within classes.

Univariate tests of continuous predictors showed significant results in the case of percentage of females in the sample ( z = 2.11; P = 0.04), age of participants ( z = –1.67; P = 0.09), grade ( z = –1.80; P = 0.07) and year of publication ( z = –2.76; P = 0.006).

All significant predictors in the univariate analysis—with the exception of grade which had a very high correlation with age ( r = 0.97; P = 0.000)—were entered into a weighted least-squares regression analysis. In general, the remaining set of predictors had a moderate degree of intercorrelation, although none of the coefficients were statistically significant.

In the weighted least-squares regression analysis, only parental participation and the percentage of females in the study were significant. The two-predictor model explained 28% of the variance in effect sizes. The test of model specification yielded a significant Q E statistic suggesting that the two-predictor model cannot be regarded as correctly specified (see Table IV ).

This review synthesized the findings from controlled sex education interventions reporting on abstinent behavior. The overall mean effect size for abstinent behavior was very small, close to zero. No significant effect was associated to the type of intervention: whether the program was abstinence-oriented or comprehensive—the source of a major controversy in sex education—was not found to be associated to abstinent behavior. Only two moderators—parental participation and percentage of females—appeared to be significant in both univariate tests and the multivariable model.

Although parental participation in interventions appeared to be associated with higher effect sizes in abstinent behavior, the link should be explored further since it is based on a very small number of studies. To date, too few studies have reported success in involving parents in sex education programs. Furthermore, the primary articles reported very limited information about the characteristics of the parents who took part in the programs. Parents who were willing to participate might differ in important demographic or lifestyle characteristics from those who did not participate. For instance, it is possible that the studies that reported success in achieving parental involvement may have been dealing with a larger percentage of intact families or with parents that espoused conservative sexual values. Therefore, at this point it is not possible to affirm that parental participation per se exerts a direct influence in the outcomes of sex education programs, although clearly this is a variable that merits further study.

Interventions appeared to be more effective when geared to groups composed of younger students, predominantly females and those who had not yet initiated sexual activity. The association between gender and effect sizes—which appeared significant both in the univariate and multivariable analyses—should be explored to understand why females seem to be more receptive to the abstinence messages of sex education interventions.

Smaller-scale interventions appeared to be more effective than large-scale programs. The larger effects associated to small-scale trials seems worth exploring. It may be the case that in large-scale studies it becomes harder to control for confounding variables that may have an adverse impact on the outcomes. For example, large-scale studies often require external agencies or contractors to deliver the program and the quality of the delivery of the contents may turn out to be less than optimal ( Cagampang et al ., 1997 ).

Interestingly there was a significant change in effect sizes across time, with effect sizes appearing to wane across the years. It is not likely that this represents a decline in the quality of sex education interventions. A possible explanation for this trend may be the expansion of mandatory sex education in the US which makes it increasingly difficult to find comparison groups that are relatively unexposed to sex education. Another possible line of explanation refers to changes in cultural mores regarding sexuality that may have occurred in the past decades—characterized by an increasing acceptance of premarital sexual intercourse, a proliferation of sexualized messages from the media and increasing opportunities for sexual contact in adolescence—which may be eroding the attainment of the goal of abstinence sought by educational interventions.

In terms of the design and implementation of sex education interventions, it is worth noting that the length of the programs was unrelated to the magnitude in effect sizes for the range of 4.5–30 h represented in these studies. Program length—which has been singled out as a potential explanation for the absence of significant behavioral effects in a large-scale evaluation of a sex education program ( Kirby et al ., 1997a )—does not appear to be consistently associated with abstinent behavior. The impact of lengthening currently existing programs should be evaluated in future studies.

As it has been stated, the exploration of moderator variables could be performed only partially due to lack of information on the primary research literature. This has been a problem too for other reviewers in the field ( Franklin et al ., 1997 ). The authors of primary research did not appear to control for nor report on the potentially confounding influence of numerous variables that have been indicated in the literature as influencing sexual decision making or being associated with the initiation of sexual activity in adolescence such as academic performance, career orientation, religious affiliation, romantic involvement, number of friends who are currently having sex, peer norms about sexual activity and drinking habits, among others ( Herold and Goodwin, 1981 ; Christopher and Cate, 1984 ; Billy and Udry, 1985 ; Roche, 1986 ; Coker et al ., 1994 ; Kinsman et al ., 1998 ; Holder et al ., 2000 ; Thomas et al ., 2000 ). Even though randomization should take care of differences in these and other potentially confounding variables, given that studies can rarely assign students to conditions and instead assign classrooms or schools to conditions, it is advisable that more information on baseline characteristics of the sample be utilized to establish and substantiate the equivalence between the intervention and control groups in relevant demographic and lifestyle characteristics.

In terms of the communication of research findings, the richness of a meta-analytic approach will always be limited by the quality of the primary research. Unfortunately, most of the research in the area of sex education do not employ experimental or quasi-experimental designs and thus fall short of providing conclusive evidence of program effects. The limitations in the quality of research in sex education have been highlighted by several authors in the past two decades ( Kirby and Baxter, 1981 ; Card and Reagan, 1989 ; Kirby, 1989 ; Peersman et al ., 1996 ). Due to these deficits in the quality of research—which resulted in a reduced number of studies that met the criteria for inclusion and the limitations that ensued for conducting a thorough analysis of moderators—the findings of the present synthesis have to be considered merely tentative. Substantial variability in effect sizes remained unexplained by the present synthesis, indicating the need to include more information on a variety of potential moderating conditions that might affect the outcomes of sex education interventions.

Finally, although it is rarely the case that a meta-analysis will constitute an endpoint or final step in the investigation of a research topic, by indicating the weaknesses as well as the strengths of the existing research a meta-analysis can be a helpful aid for channeling future primary research in a direction that might improve the quality of empirical evidence and expand the theoretical understanding in a given field ( Eagly and Wood, 1994 ). Research in sex education could be greatly improved if more efforts were directed to test interventions utilizing randomized controlled trials, measuring intervening variables and by a more careful and detailed reporting of the results. Unless efforts are made to improve on the quality of the research that is being conducted, decisions about future interventions will continue to be based on a common sense and intuitive approach as to `what might work' rather than on solid empirical evidence.

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

Description of moderator variables

Effect sizes of studies

Tests of categorical moderators for abstinence

Weighted least-squares regression and test of model specification

Barth, R., Fetro, J., Leland, N. and Volkan, K. ( 1992 ) Preventing adolescent pregnancy with social and cognitive skills. Journal of Adolescent Research , 7 , 208 –232.

Billy, J. and Udry, R. ( 1985 ) Patterns of adolescent friendship and effects on sexual behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly , 48 , 27 –41.

Brown, L., Barone, V., Fritz, G., Cebollero, P. and Nassau, J. ( 1991 ) AIDS education: the Rhode Island experience. Health Education Quarterly , 18 , 195 –206.*

Cagampang, H., Barth, R., Korpi, M. and Kirby, D. ( 1997 ) Education Now And Babies Later (ENABL): life history of a campaign to postpone sexual involvement. Family Planning Perspectives , 29 , 109 –114.

Card, J. and Reagan, R. ( 1989 ) Strategies for evaluating adolescent pregnancy programs. Family Planning Perspectives , 21 , 210 –220.

Christopher, F. and Roosa, M. ( 1990 ) An evaluation of an adolescent pregnancy prevention program: is `just say no' enough? Family relations , 39 , 68 –72.

Christopher, S. and Cate, R. ( 1984 ). Factors involved in premarital sexual decision-making. Journal of Sex Research , 20 , 363 –376.

Coker, A., Richter, D., Valois, R., McKeown, R., Garrison, C. and Vincent, M. ( 1994 ) Correlates and consequences of early initiation of sexual intercourse. Journal of School Health , 64 , 372 –377.

Cook, T. and Campbell, D. (1979) Quasi-experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings . Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Denny, G., Young, M. and Spear, C. ( 1999 ) An evaluation of the Sex Can Wait abstinence education curriculum series. American Journal of Health Behavior , 23 , 134 –143.*

Dunkin, M. ( 1996 ) Types of errors in synthesizing research in education. Review of Educational Research , 66 , 87 –97.

Eagly, A. and Wood, W. (1994) Using research synthesis to plan future research. In Cooper, H. and Hedges, L. (eds), The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 485–500.

Franklin, C., Grant, D., Corcoran, J., Miller, P. and Bultman, L. ( 1997 ) Effectiveness of prevention programs for adolescent pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family , 59 , 551 –567.

Frost, J. and Forrest, J. ( 1995 ) Understanding the impact of effective teenage pregnancy prevention programs. Family Planning Perspectives , 27 , 188 –195.

Gilbert, G. and Sawyer, R. (1994) Health Education: Creating Strategies for School and Community Health. Jones & Bartlett, Boston, MA.

Guyatt, G., Di Censo, A., Farewell, V., Willan, A. and Griffith, L. ( 2000 ) Randomized trials versus observational studies in adolescent pregnancy prevention. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology , 53 , 167 –174.

Hall, J., Rosenthal, R., Tickle-Deignen, L. and Mosteller, F. (1994) Hypotheses and problems in research synthesis. In Cooper, H. and Hedges, L. (eds), The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 457–483.

Hedges, L. and Olkin, I. (1985) Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

Herold, E. and Goodwin, S. ( 1981 ) Adamant virgins, potential non-virgins and non-virgins. Journal of Sex Research , 17 , 97 –113.

Holder, D., Durant, R., Harris, T., Daniel, J., Obeidallah, D. and Goodman, E. ( 2000 ) The association between adolescent spirituality and voluntary sexual activity. Journal of Adolescent Health , 26 , 295 –302.

Holmes, C. ( 1984 ) Effect size estimation in meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Education , 52 , 106 –109.

Howard, M. and McCabe, J. ( 1990 ) Helping teenagers postpone sexual involvement. Family Planning Perspectives , 22 , 21 –26.*

Howard, M. and Mitchell, M. ( 1993 ) Preventing teenage pregnancy: some questions to be answered and some answers to be questioned. Pediatric Annals , 22 , 109 –118.

Hunter, J. ( 1997 ) Needed: a ban on the significance test. Psychological Science , 8 , 3 –7.

Jacobs, C. and Wolf, E. ( 1995 ) School sexuality education and adolescent risk-taking behavior. Journal of School Health , 65 , 91 –95.

Johnson, B. (1989) DSTAT: Software for the Meta-Analytic Review of Research Literatures . Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

Jorgensen, S. ( 1991 ) Project taking-charge: An evaluation of an adolescent pregnancy prevention program. Family Relations , 40 , 373 –380.*

Jorgensen, S, Potts, V. and Camp, B. ( 1993 ) Project Taking Charge: six month follow-up of a pregnancy prevention program for early adolescents. Family Relations , 42 , 401 –406

Kinsman, S., Romer, D., Furstenberg, F. and Schwarz, D. ( 1998 ) Early sexual initiation: the role of peer norms. Pediatrics , 102 , 1185 –1192.

Kirby, D. ( 1989 ) Research on effectiveness of sex education programs. Theory and Practice , 28 , 165 –171.

Kirby, D. ( 1992 ) School-based programs to reduce sexual risk-taking behaviors. Journal of School Health , 62 , 280 –287.

Kirby, D. and Baxter, S. ( 1981 ) Evaluating sexuality education programs. Independent School , 41 , 105 –114.

Kirby, D. and Coyle, K. ( 1997 ) School-based programs to reduce sexual risk-taking behavior. Children and Youth Services Review , 19 , 415 –436.

Kirby, D., Barth, R., Leland, N. and Fetro, J. ( 1991 ) Reducing the risk: impact of a new curriculum on sexual risk-taking. Family Planning Perspectives , 23 , 253 –263.*

Kirby, D., Short, L., Collins, J., Rugg, D., Kolbe, L., Howard, M., Miller, B., Sonenstein, F. and Zabin, L. ( 1994 ) School-based programs to reduce sexual-risk behaviors: a review of effectiveness. Public Health Reports , 109 , 339 –360.

Kirby, D., Korpi, M., Barth, R. and Cagampang, H. ( 1997 ) The impact of Postponing Sexual Involvement curriculum among youths in California. Family Planning Perspectives , 29 , 100 –108.*

Kirby, D., Korpi, M., Adivi, C. and Weissman, J. ( 1997 ) An impact evaluation of Project Snapp: an AIDS and pregnancy prevention middle school program. AIDS Education and Prevention , 9 (A), 44 –61.*

Levy, S., Perhats, C., Weeks, K., Handler, S., Zhu, C. and Flay, B. ( 1995 ) Impact of a school-based AIDS prevention program on risk and protective behavior for newly sexually active students. Journal of School Health , 65 , 145 –151.

Main, D., Iverson, D., McGloin, J., Banspach, S., Collins, J., Rugg, D. and Kolbe, L. ( 1994 ) Preventing HIV infection among adolescents: evaluation of a school-based education program. Preventive Medicine , 23 , 409 –417.*

Matt, G. and Cook, T. (1994) Threats to the validity of research synthesis. In Cooper, H. and Hedges, L. (eds), The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 503–520.

Miller, N. and Pollock, V. (1994) Meta-analytic synthesis for theory development. In Cooper, H. and Hedges, L. (eds), The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 457–483.

O'Donnell, L., Stueve, A., Sandoval, A., Duran, R., Haber, D., Atnafou, R., Johnson, N., Grant, U., Murray, H., Juhn, G., Tang, J. and Piessens, P. ( 1999 ) The effectiveness of the Reach for Health Community Youth Service Learning Program in reducing early and unprotected sex among urban middle school students. American Journal of Public Health , 89 , 176 –181.*

Peersman, G., Oakley, A., Oliver, S. and Thomas, J. (1996) Review of Effectiveness of Sexual Health Promotion Interventions for Young People . EPI Centre Report, London.

Quinn, J. ( 1986 ) Rooted in research: effective adolescent pregnancy prevention programs. Journal of Social Work and Human Sexuality , 5 , 99 –110.

Repucci, N. and Herman, J. ( 1991 ) Sexuality education and child abuse: prevention programs in the schools. Review of Research in Education , 17 , 127 –166.

Roche, J. ( 1986 ) Premarital sex: attitudes and behavior by dating stage. Adolescence , 21 , 107 –121.

Roosa, M. and Christopher, F. ( 1990 ) Evaluation of an abstinence-only adolescent pregnancy prevention program: a replication. Family Relations , 39 , 363 –367.*

Rosenthal, R. (1991) Meta-analytic Procedures for Social Research. Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Rosenthal, R. and Rubin, D. ( 1982 ) Comparing effect sizes of independent studies. Psychological Bulletin , 92 , 500 –504.

Sexual abstinence program has a $250 million price tag (1997) The Herald Times , Bloomington, Indiana, March 5, p. A3.

St Leger, L. ( 1999 ) The opportunities and effectiveness of the health promoting primary school in improving child health—a review of the claims and evidence. Health Education Research , 14 , 51 –69.

Thomas, G., Reifman, A., Barnes, G. and Farrell, M. ( 2000 ) Delayed onset of drunkenness as a protective factor for adolescent alcohol misuse and sexual risk taking: a longitudinal study. Deviant Behavior , 21 , 181 –210.

Visser, A. and Van Bilsen, P. ( 1994 ) Effectiveness of sex education provided to adolescents. Patient Education and Counseling , 23 , 147 –160.

Walter, H. and Vaughan, R. ( 1993 ) AIDS risk reduction among multiethnic sample of urban high school students. Journal of the American Medical Association , 270 , 725 –730.*

Weeks, K., Levy, S., Chenggang, Z., Perhats, C., Handler, A. and Flay, B. ( 1995 ) Impact of a school-based AIDS prevention program on young adolescents self-efficacy skills. Health Education Research , 10 , 329 –344.*

Zabin, L. and Hirsch, M. (1988) Evaluation of Pregnancy Prevention Programs in the School Context . Lexington Books, Lexington, MA.

- least-squares analysis

- sex education

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-3648

- Print ISSN 0268-1153

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Advertisement

“But Everything Else, I Learned Online”: School-Based and Internet-Based Sexual Learning Experiences of Heterosexual and LGBQ + Youth

- Open access

- Published: 21 November 2023

- Volume 46 , pages 461–485, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Joshua Gamson 1 &

- Rosanna Hertz 2

1531 Accesses

Explore all metrics

A Correction to this article was published on 06 December 2023

This article has been updated

Building upon scholarship on sex education, our research aims to understand how youth with a range of sexual identities have experienced school-based sex education, how they have explored sexual content online, and how they see the two in relation to each other. We thus ask: (1) How do youth with varied sexual identities recall experiencing formal school-based sex education from elementary through high school offerings? (2) How do heterosexual and LGBQ + youth utilize the Internet and social media sites for sexual learning? Through in-depth interviews with college students, we find that heterosexual and LGBQ + youth report that formal sex education was both limited and heteronormative; LGBQ + youth felt particularly unprepared for sexual experiences and health hygiene, and sometimes found ways to translate the information provided for their own needs. Despite some overall similarities in online sexual explorations, experiences of online sexual learning proved quite divergent for youth of different sexual identities. Heterosexual youth were likely to search for information on sexual pleasure and entertainment; in contrast, LGBQ + youth sought information to fill in knowledge gaps about non-conforming sexualities, and often used the digital space for identity discovery, confirmation, and affirmation. For both groups, online explorations interacted with offline ones through a back-and-forth in which youth tested out in one arena what they had learned in the other. These findings highlight the dynamic interaction between formal school curriculum, informal online sexual learning, and sexual scripts, identities and practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Role of Sexually Explicit Material in the Sexual Development of Same-Sex-Attracted Black Adolescent Males

Evidence for a comprehensive sexuality education intervention that enhances chinese adolescents’ sexual knowledge and gender awareness and empowers young women, the self-identification, lgbtq+ identity development, and attraction and behavior of asexual youth: potential implications for sexual health and internet-based service provision.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Contraceptives and stuff like that I think I learned mostly through sex ed class. But everything else, I learned online. Anal sex, learned online. Oral sex and the details about that, learned online. Self-pleasure, masturbation, learned that online. Histories of queer communities, different sexualities and gender identities, learned online. Different ways that queer communities engage in sex, learned it online. Everything except penis-penetration type of sex, I learned everything else online. Everything. – Abby (age 20, Latinx, queer, non-binary)

Our research aims to understand how youth with a range of sexual identities have experienced school-based sex education, how they have explored sexual content online and how they see the two in relation to each other. It emerges from a recognition that while the existing literature on sex education is well developed, the research on sexual learning online is less robust. In particular, we know little about how school-based and Web-based sexual learning experiences differ for youth with non-normative sexual and gender identities and those who identify as straight. We also know little about the interaction between school-based and online sexual learning.

In this study, based on in-depth interviews with 56 college students from a variety of backgrounds and identities, we ask: (1) How do youth with varied sexual identities recall experiencing formal school-based sex education from elementary through high school offerings? (2) How do heterosexually-identified and LGBQ + -identified youth utilize the Internet and social media sites for self-discovery and for acquiring information not offered in their formal sex education curriculum, and how do they assess that information?

Bridging and building upon the scholarship on LGBQ + student experiences (Beattie et al. 2021 ) and on formal and informal sex education, we find that while both heterosexual and LGBQ + youth report that formal sex education was both limited and heteronormative, their experiences of online sexual learning are quite divergent. Largely excluded from their school’s sex education curriculum, LGBQ + youth often seek online content related to their identity or imagined partners and practices—in ways that may be both affirming and confusing. This dynamic points to ways the reform of school-based sex education remains significant, despite its diminished role as an information source (Lindberg et al. 2016 ), and highlights the interaction between formal school curriculum, informal online learning, and sexual “scripts” (Simon and Gagnon 1986 ), identities and practices.

Sex Education and Online Sexual Learning

Decades of research have established three clear characteristics of formal sex education in the USA: (1) governed largely at the local and state level, it varies widely from place to place; (2) it is usually both narrow in scope and short in duration; and (3) it is almost exclusively heteronormative.

Informed by competing sex education policy frameworks—one advocating “comprehensive” sex education and the other “abstinence” education (Fields 2012 ; Fine and McClelland 2006 ; Irvine 2002 ; Luker 2006 )—the curriculum runs the gamut from conservative just-say-no to liberal here’s-how-it-works to total silence (Kramer 2019 ). Regardless of ideological bent, American sex education tends to reinforce dominant understandings of race, class, gender, and sexuality (Connell and Elliott 2009 ; Fields 2005 , 2008 ; McNeill 2013 ). In particular, sex education in the USA has been almost exclusively focused on heterosexual identities and practices (Hirst 2004 ; Irvine 2002 ; Luker 2006 ; Fine and McClelland 2006 ; Pascoe 2007 ) and at times outright hostile towards non-normative ones (McNeil 2013; Gowen and Winges-Yanez 2014 ).

Formal sex education has been one major institutional source of sexual scripts at what Simon and Gagnon ( 1986 , 105) call the “cultural scenario” level, a kind of collective “instructional guide” specifying the “appropriate objects, aims, and desirable qualities of self-other relations,” instructing the “times, places, sequences of gesture and utterance and… what the actor and his or her coparticipants (real or imagined) are assumed to be feeling,” which are then “rehearsed at the time of our initial sexual encounters.” These cultural scripts are then adapted and molded by individuals into “interpersonal scripts” that shape “the materials of relevant cultural scenarios into scripts for behavior in particular contexts,” and brought into the self as “intrapsychic scripts,” the “private world of wishes and desires that are experienced as originating in the deepest recesses of the self” (Simon and Gagnon 1986 , 99–100).

Formal sex education, of course, is not the only source of sexual information, scripts, and learning. Young people also learn about sex and sexuality outside of schools from people around them (family, peers, community, and religious leaders) and, though often passively, through the consumption of popular culture. Since the inception of popular media in the early twentieth century, generally speaking, “depictions of sexual content and imagery abound in popular film, television, and advertising”; in centralized, risk-averse, commercial cultural industries, the sexual content was typically characterized by “regressive and often objectifying portrayals of sex and sexuality,” routinely rendering non-normative sexualities invisible or stigmatizing them, if still open to “queer readings” (Grossman 2020 , 281). That is, the cultural scripts and sexual content provided by popular culture was—until more recent structural changes such as the expansion of cable and then streaming outlets—quite a thin and narrow source for sexual learning, particularly for people experiencing desires and identities outside of the sexual and gender mainstream. Digital technologies have plainly altered that, rendering new popular culture far more diverse, more individualized, and more emphemeral, not only “personal, mass, and global but also decentralized” (Grossman 2020 , 286). This is, of course, a very different cultural environment for sexual learning.

While the relevance of school-based sex ed is in decline (Lindberg et al. 2016 ), in recent years social media and online spaces, and the popular culture circulating within them, have become a crucial informal curriculum through which young people learn about sexuality (Adams-Santos 2020 ; Boyd 2015 ; Fields 2012 ; Orenstein 2016 ; Orenstein 2020 ; Simon and Daneback 2013 ) and “craft and articulate their sexualities” (Adams-Santos 2020 , 2)—what some have called “the new sex ed” (Orenstein 2020 , 52). The Internet’s “availability, acceptability, affordability, anonymity, and aloneness” make it “unique in the delivery of sexual information in the digital age” (Simon and Daneback 2013 , 315, 306). For youth with non-normative sexual desires and identities, some researchers have found, the various available online platforms hold a particular draw, interacting with offline experiences “in ways that shape their emerging identities, social lives, romantic relationships, sexual behaviors, and physical and sexual health” (DeHaan et al. 2013 ). The prevalence of “techno-sexuality” (Waskul 2014 ), which allows youth to explore and experience sexuality beyond adult control, combined with the continued heteronormative emphasis of school-based sex education, points to the questions that animate our research.

While research on online sexual learning is increasing, and has established that “online sex education plays a role in adolescents’ lives,” just what sort of role, and how, and for whom, remains more poorly understood. Scholars have suggested, for instance, that “there is little knowledge on adolescents’ use of online sexual information for sexuality education in particular” (Nikkelen et al. 2020 , 190); that “the qualitative experiences of adolescents who engage with sex information online, from their initial interest in information to the effects such information could have on their lives,” the “process of applying online information offline” and “demographic differences” all remain understudied (Simon and Daneback 2013 , 312–314). Furthermore, the dynamic relationship between formal sex education—what it does and does not provide to youth—and online sexual explorations, the decentering of traditional sexual scripts (at the cultural, interpersonal, and intrapsychic levels) and the impact of this destabilization, have received scant scholarly attention (for an exception, see DeHaan et al. 2013 ). Our research addresses these gaps.

Methods and Data

We recruited college-age students between the ages of 18 and 22 years. Given national differences in sex education, we limited our respondents to the USA and territories. We found respondents primarily through posting flyers (online due to COVID restrictions) on websites affiliated with Boston-area colleges. These colleges attracted students from varied geographic locations in the USA and Puerto Rico, types of schooling, sexual identities, race and social class backgrounds (see Table 1 ).

On the flyers we indicated that we were interested in learning about sex education programs in their schools and also their use of digital spaces. We restricted the recruitment to young people enrolled in college because we wanted to understand how these youth made sense of the “sexual scripts” (Simon and Gagnon 1986 ), or social underpinnings of sexuality and sexual identity taught in high school sex ed programs and augmented or challenged by private Internet searches and social media interactions, once they were away from home. Given our particular interest in the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual (LGBQ +) youth, we indicated on organization posts that we were particularly interested in LGBQ + youth and their experiences. In total we conducted 56 in-depth interviews with college students.

This paper compares college age youth who currently identify as heterosexual or straight (39.3%) with the experiences of those who identify as LGBQ + or queer (60.7%) youth. While we distinguish between straight and queer respondents on the basis of their current self-reported identities, many of our respondents described experiences of fluid or changing sexual practices and desires. While youth are coming out as lesbian, gay, queer, questioning, bisexual at younger ages than in the past, data indicates that most reveal their sexual identity to family and friends in college (Beattie et al. 2021 ; Dunlap 2016 ). For instance, 20% reported that in high school they either identified as heterosexual or were questioning their sexual or gender identities but currently identify as LGBQ + . In the sections that follow we capture this fluidity in their descriptions of identify shifts and discoveries, both in the context of sex education in schools and in online explorations, which we note when we introduce quotes from our respondents.

Online flyers included a link to a Google form that college students from 18 to 22 years old completed in order to volunteer. On the form we asked for contact information and background information (age, pronouns, race, sexual identity in high school and currently, gender identity, region of the country where they grew up). We re-checked this information at the time of the interview and used it for coding purposes. When we reached out to our respondents, we also sent then a consent form that included information on audio and video recording and confidentiality. Interviews lasted between 1.5 and 2 hours, were audio recorded and videotaped, and transcribed verbatim. Since Zoom allows us to record with simultaneous transcription, we destroyed the video recording within a week after checking the accuracy of the transcript. To protect our respondents’ confidentiality, we informed them that we would use pseudonyms in any publications and presentations.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards for the protection of human subjects at the University of San Francisco and Wellesley College (for Zoom interviews only because of pandemic restrictions on in-person interviewing in 2021). All interviews were conducted between March and November 2021.

We chose qualitative interviews as the most effective method to access interviewees’ opinions and recollections, within their social context, and for understanding multiple aspects of the same experience (Gerson and Damaske 2021 ). We developed a semi-structured interview guide that asked questions related to experiences of sex education both in their schools as well as in digital spaces, including what students recalled learning from elementary school through high school; what material was taught, for how long and by whom; the major messaging frameworks they encountered; how useful and inclusive they thought the curriculum was at the time and in retrospect; whether and how students sought information online, and if so what types of information; where they searched; and how they evaluated the information they found. We also asked for what they discussed with parents, other family members and their peers.

In the convention of interview data analysis, we developed a detailed coding scheme in order to discern patterns across interviews. Both inductive and deductive codes were developed. Construction of the codes was guided by the principles of grounded theory, with emerging themes identified and then reanalyzed for consistency and completeness (Charmaz 2006 ; Gerson and Damaske 2021 ; Glaser and Strauss 1967 ). We coded interviews to reveal the topics interviewees recalled learning in schools; how they were presented, where, for how long, and by whom; the frames through which the sexual information was presented; school-based learning outside of classroom settings; feelings and perceptions of inclusion in the curriculum; when they began consuming online content and what kinds of information or activities they sought; what sites they most frequently visited; whether they also created online content; with whom they discussed sex education content or online learnings; and how accurate and reliable they took sexually-related information to be both at schools and online. This allowed us to quantify the content, generating the figures and tables referred to in this paper.

In addition, we generated a related qualitative coding document in which interviewees’ quotes were gathered according to thematic content, in order to more deeply understand their accounts of their own learning and how they made sense of their experiences of school-based and online sexual learning, with particular attention to the divergent circumstances that led our interviewees to turn to the various online platforms available to them. Each interview was coded by at least two researchers to facilitate intercoder reliability. Coders met weekly to discuss their individual coding, referring back to the original interviews to reach consensus.

Since our respondents were in college at the time of the interviews the summer provided a natural break in interviewing. We used the summer to code the interviews conducted in the first round (March–June 2021). This allowed us to discuss where we had achieved “conceptual depth” (Nelson 2017 , 556) both with regard to the open-ended questions we were asking and also with regard to understanding the interplay between schools and online learning, and how they might differ for our two groups.

Our interviews were retrospective by necessity, and retrospective accounts hit up against the “limitations of chronological memory, the potential for hindsight-based rationalizations, as well as people’s tendencies to construct stories that place themselves in a favorable light” (Langley and Meziani 2020 , 373). People look back through the filters of the present, and details become fuzzy or distorted, and that was certainly the case in our research. Our investigations, however, are not so much aimed at a factual account of what took place in classrooms or online as at what stands out in participants’ memories, and the related “imagined meanings of their activities, their self-concepts, their fantasies about themselves” (Lamont and Swidler 2014 , 159); that is, how participants remember their sex education and online explorations, and how they understand those in relation to their life paths and identities.

Formal Sex Education: Experiences of a Limited and Heteronormative Curriculum

Most of our respondents recalled having some version of sex education, particularly in the latter parts of their schooling (see Table 1 ), though not a lot of it; what they did receive they report finding quite limited in scope and heterosexually focused. In elementary school, almost two thirds of the respondents (61.4%) had sex education, and most (77.1%) reported that it was for one class on puberty and hygiene. Almost three quarters recalled having sex education in middle school; of these, the majority (72%) said that the class was a module or a brief part of another course (such as health or biology). The largest portion of respondents (85.9%) reported having sex education in high school, again typically as a module of a course (60.4%), though a third (33.3%) recounted having a full sex education course for half a year.

Generally speaking, our respondents recall elementary school sex education focused on puberty and menstruation, typically in class meetings segregated by sex. Despite often having some exposure to this sort of information through parents (usually mothers), and finding the emphasis on bodily changes and hygiene “embarrassing,” many respondents recalled being excited for their first sex education class. As one respondent, Erika (21, Asian, cisgender woman, lesbian, attended public school in the Northeast) put it, “It was a really highly anticipated conversation. Everyone in the class knew the day we were going to talk about it and people were talking about it, like, ‘Wait, do you know this, this and this about [puberty]?’” Interestingly, our respondents recalled only learning information related to their sex assigned at birth.

By middle and high school, class content became more varied, in part to cover state-mandated material, and all students were in classes together. In some school districts these classes were supplemented by professionals from the community. In other schools, students could elect a human development course or a section of a biology course that presented information on reproduction. Respondents recalled putting condoms on bananas, learning about sexually transmitted infections (STIs), watching videos about birth, sometimes discussing consent and sexual assault and mostly being told not to have intercourse. Many noted that no answer to the central question “What is sex?” was provided.

Few of the respondents recalled learning much novel or in depth in school, regardless of whether they went to private or public schools. Some respondents told us that the sex education came too late: they had already learned quite a bit about sex from peers and other sources, and some were already involved in sexual activity. Others reported that they did not pay a lot of attention because the topics they were interested in, such as sexual pleasure and sexual practices, were not covered. All agreed that in addition to pleasures and practices, a vast range of sex- and sexuality-related topics were almost entirely absent from the curriculum, including cultural representations of sexuality, pornography, relationships and dating, non-cisgender and non-heterosexual identities, and abortion.

Overarching Cultural Scripts: Abstinence, Danger, Gender, and Heterosexuality

Our respondents articulated, looking back, the cultural scripting their school-based education provided, in terms of the appropriate “objects, aims, and desirable qualities,” as well as the appropriate “times, places, sequences” and emotional content, for sexual encounters (Simon and Gagnon 1986 , 105). The focus, they reported, was most often on the dangers of sex (disease, unplanned pregnancy) and ways to avert them (condoms, occasionally sexual consent tools), often with a fear or abstinence message, and often from a male perspective. (While we expected that secular private schools would be more progressive in sex education content, the evidence from our interviews suggested that this was not the case.)

For instance, John, a 21-year-old white, cisgender, straight man from rural Colorado, received minimal sex education from his private school. He recalled,

I don’t think I learned anything new. I think all I got out of it is like, “Oh that’s how you have heterosexual sex, this is what a penis looks like going into a vagina,” from a cheesy video – and I already kind of knew this… It was the biology of how it works. I wouldn’t say I remember anything about pleasure or things like that. It was mainly just the scientific aspects of it.

As Jessica, a 20-year-old, white, cisgender woman from the Northeast who came out as bisexual in her junior year of high school, put it, “teachers had to walk a fine line between informing us and not seeming like they were encouraging us to have sex.” Even so, she recalls, the focus was on male pleasure. “Male ejaculation was discussed. Why was there no discussion of oral sex or lube or that women could have an orgasm?” Elena, age 20, Latinx, non-binary, queer and asexual, who attended public school in southeast LA, echoed this view. Her elementary school sex education was brief (“a one-time, thirty-minute to an hour class”) and focused on puberty, and her middle school offered one session in seventh grade (“how to put a condom on a banana”). Recalling her “penis-heavy” 9 th grade health class, she said:

The biggest thing I remember was just abstinence. “Don't have sex. The best contraceptive is never have sex, so just don't have sex." Which is not helpful at all, because most people engage in sexual activity. I don't remember anything about other forms of sex ed, like how to have sex or different forms of pleasure or anything like that. The knowledge about how to apply a condom and what you can catch is not really helpful because then you don't even know how to engage in sex…. So then, well, I know that I can catch chlamydia, for example, but what are ways that I can prevent it? None of that. What ways can I engage in sex? Never taught. So were they ever that helpful? Not really.

As another respondent put it, “Abstinence is [presented as] the gold standard.”

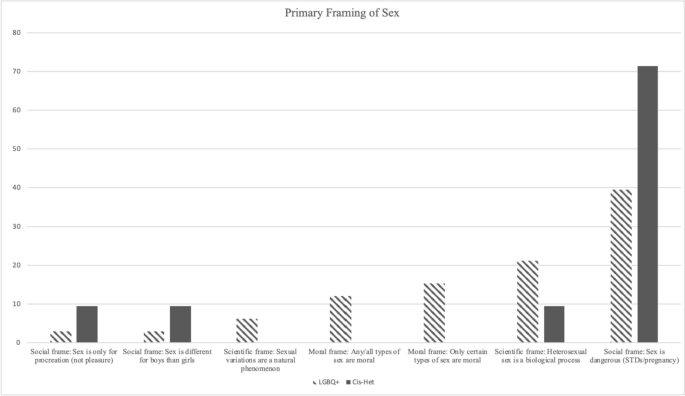

The majority of our respondents, regardless of identity, understood the focus on abstinence to be tied to the primary framing of sex as risky, dangerous, and fearful; their classes focused primarily on disease and pregnancy (See Fig. 1 ). As Jocelyn (African American, cisgender, straight woman, from an urban, East Coast public school) recalled, the message was: “If you want to avoid STI, don’t have sex. If you don’t want to get pregnant, don’t have sex.” Similarly, Shenita, a 21-year-old, African American, cisgender, straight woman who attended a public school in the mid-Atlantic suburbs, recalled her teacher comparing sex to “operating heavy machinery, dangerous” and telling the class of 13-year-olds that “none of us should be having sex within the next ten years.”

Primary Framing of the Sex Ed Curriculum

We also found a general consensus—again in line with most popular and academic accounts of American sex education (Gowen and Winges-Yanez 2014 ; McNeill 2013 ) —that the sex ed curriculum youth encountered generally assumed everyone in the room was heterosexual, implicitly or explicitly equated heterosexuality with sexual normalcy, and treated non-heterosexual sexualities as rare, a side note, or nonexistent. Youth repeatedly recalled that teachers “very much emphasized that heterosexual dynamic” (Ana Luisa, 18, Latinx, cisgender woman, lesbian and educated in public school), with a “very heterosexual” take on pregnancy and an “overall emphasis on heterosexual couples” in discussions of and videos about sexually transmitted infections (Lizzie, 19, white, cisgender woman, asexual, queer, public school-educated). Nearly three-quarters of the LGBQ + youth, and more than nine-tenths of the heterosexual youth, said that only heterosexual relationships were discussed in their sex ed classes; four-fifths of the LGBQ + youth and all of their heterosexual counterparts indicated that non-cisgender identities were never discussed. LGBQ + youth rarely asked for information that might be more applicable to their lives because, some reported, they felt they would be “flagged” in school peer cultures that emphasized heteronormativity.

When non-normative sexualities were discussed, a few respondents noted, it was often in the context of HIV. For instance, Julia, a 19-year-old, Latinx/white, nonbinary, lesbian, educated in public school in rural Georgia, recalls:

I knew I was queer in middle school and I was hoping to hear something. The only time I ever heard about queer people in sex ed was when they were talking about HIV and AIDS. So that was a scary thing because I had just figured out I was queer, and then the gym teacher comes in and says, “This is a bunch of dead gay people, and you can be like them, too,” and I was like, “I could be like them too?”

The absence of information about non-heterosexual practices was, not surprisingly, less directly concerning to cisgender heterosexual respondents than their LGBQ + counterparts. Thus, their experiences diverged quite significantly. LGBQ + youth in particular recall the heteronormative bent of their school-based sex education as rendering it at best unhelpful to their understanding of sexual identities and practices. As Ana Luisa put it, at the time she already knew that heterosexual dynamics were “just not something I would have encountered,” so sex ed “was just useless to me personally.” She and her similarly positioned peers simply did not find much material from the cultural scripts offered by formal sex education with which to develop interpersonal scripts for their sexual interactions, or that affected the shape of their intrapsychic scripts of sexual desire.

Another absence is worth noting: although we did not query them about it directly, none of our respondents reported themes of love, care, and affection for others as a prominent theme in their formal sex education. Hints of such a framework in which to place sex occasionally came through in, for instance, lessons on consent, which tied sexual behavior to a kind of ethics of care for the other, and in lessons on sexual safety and health, which tied sexual behavior to a care of oneself and others. Yet, the notion that love is a necessary component of sex (or a precursor for sexual activity) appears to have been weak enough in the curriculum to not emerge organically in our respondents’ memories.

LGBQ + Youth and School-Based Sex Ed: Absences, Improvisations, and Memory

While all youth reported that there was limited information that was useful for first sexual encounters, LGBQ + youth felt particularly unprepared for sexual experiences and health hygiene. As Karl, who identifies as a cisgender gay man and Latinx, and went to public schools in the Northeast, put it, “They never really went over things like mouth guards or finger ones. For other people who do not practice actual intercourse, how are they going to know how to protect themselves?” Marlie, who went to private school in California and identifies as Latinx, bisexual/queer and a cisgender woman, similarly noted:

I don’t think there was any information that prepared me for my first sexual encounters, which started actually that year when I was 15 years old. In the classes, there wasn’t as much of an emphasis on the actual act of sex and what that is like and what happens. It is not that they emphasized heterosexual sex, it is that they did not talk about queer sex…. We definitely did not talk about what fingering is, what vulva on vulva sex is like, what penis on penis sex is like, any of that. My first sexual encounters were not with somebody with a penis, so I didn’t feel prepared to know about proper hygiene regarding fingering or dental dams or any of that stuff.

Other respondents found ways to translate—or perhaps more accurately, to hack—the heterosexually-directed information they encountered. For instance, Rhonda, age 22, Native American and white, cisgender lesbian woman, reported that in her public school in Kansas teachers focused a lot on preventing STDs and “keeping safe” through condom use, but “we never learned about LGBQ sex ed at all.”

So when a lot of us started coming out, we were like, “Well, what do we do now?” We knew condoms, in heterosexual relations, could help prevent STDs, but we didn’t know how that worked if we were having sex with women or AFAB [assigned female at birth] people. One thing that was very novel to us was that you could cut open a condom and make a dental dam – because you couldn’t buy dental dams where we lived, they just weren’t available anywhere. So, we just compared what we needed to use with what we had learned from our health classes. And whenever one of our friends was going to meet someone new, we would tell them, ”Hey, don’t forget about this cool trick you can use, because you don’t want to get an STD.”

In effect, through efforts such as these condom displays, queer youth found it necessary and possible to create new “interpersonal scripts”: The “disjunctures of meaning between distinct spheres of life,” as Simon and Gagnon pointed out ( 1986 , 99, 102, 106) created moments of “ad hoc improvisation” at the interpersonal level.

While a few respondents reported seeking support from queer-friendly teachers outside of sex ed classes, still others internalized the notion that their sexual desires and curiosities were irrelevant. Emily, for example, who identifies as a white, asexual, cis-gender woman, who went to a public school in the Northeast, noted that.

just one mention of there being other sexualities than straight, gay and bi, would’ve been useful for me, just off-hand, in a context that conveys authority would have been helpful…. I just figured I was wired differently and just left it at that.

She reached the conclusion, she said, that “I was an outlier and did not count.”

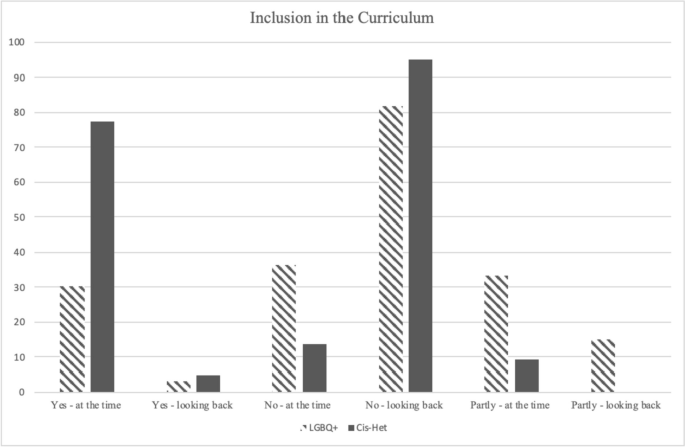

Interestingly, LGBQ+ youth also were less likely than their straight counterparts to recall a framing of sex as dangerous (39% of LGBQ+ youth vs. 71% of heterosexual youth). Queer identifying youth reported more often that their sex education classes framed sex scientifically, as a heterosexual biological process (21% of LGBQ+ youth vs. 9.5% of heterosexual youth). Furthermore, while no heterosexual youth recalled receiving sex education through a moral frame, LGBQ+ youth were more likely to recall a moral frame in the curriculum, either one that treated certain kinds of sex as immoral (15%) or all sex as morally acceptable (12%) (see Fig. 1 ). Finally, heterosexual youth recalled feeling in high school that the curriculum included material relevant to them (77%), but only 30% of the LGBQ+ youth felt the same way. Those who felt included or even partly included often recalled that same sex relationships were briefly mentioned, and that this mention made them feel included. However, at the time of the interview, and now in college, regardless of sexual identity, the majority did not feel that the curriculum was inclusive of them or of their LGBQ+ friends (see Fig. 2 ).

Inclusion in the Curriculum

While at first glance these findings seem counterintuitive, we suggest that they are outcomes of a nascent or developed identity difference that shapes the reception and memory of sex education. The broader range of sex ed frames LGBQ + respondents recall may have to do with their heightened sensitivity to the cultural frames surrounding non-normative sexualities and genders (Weeks 2023 ), the “paradigmatic” scripting of sexuality (Simon and Gagnon 1986 , 102)—as morally questionable, unnatural, or scientifically explicable deviations—that have less personal resonance for heterosexual respondents. The greater inclusivity that almost a third of LGBQ + students recall may have to do with the identity needs through which they filtered the curriculum, in which any mention of non-normative sexualities, and of ways to manage heterosexual situations as an outsider to them, stood out as memorable. Their overall irrelevance and invisibility within the curriculum—and within the cultural scenario scripting more broadly—we suggest, made moments of relevance and visibility particularly memorable.

Pleasure, Identity, and Online Sexual Learning: Convergent and Divergent Experiences

Online sexual explorations started early for the youth we interviewed, and were both constant and extensive. The Internet and its myriad platforms—including not just websites but interactive social media and online communities—was robust by the time all of our interviewees entered middle school. Our oldest interviewees at age 22 were 12–14 years old in 2011–2013; while our youngest interviewees at age 18 were 12–14 years old in 2015–2017.

Internet searches for almost two-thirds of our respondents began in middle school between the ages of 12–14, with just over a quarter searching the Internet even earlier (See Table 1 ). Although parents rarely monitored their children’s Internet searches, many of our respondents told us that they would sneak down early in the morning or late at night to the family computer or iPad hoping that their parents would not discover their activities. By high school all of our respondents, who completed high school between 2017 and 2020, had their own devices (phones, iPads, computers) in their rooms. Still, they were careful to hide their Internet Web search history.

Online Explorations: Finding and Making New Sexual Scripts

Our respondents used a variety of online platforms, each facilitating different kinds of activity, to seek out information, explore identities, compare themselves to their peers, and for entertainment and fun, regardless of their sexual identity. Online space—whether social network, content, or media-sharing platforms—of course, offers significant communication changes not readily found offline, serving as “a massive expert database,” providing easy access to the kind of credentialed expertise found in formal sex education; as a “global broker, a way for individuals with special concerns to find each other,” allowing for the dissemination of alternative and sometimes counter-normative sexual expertise, as well as sexuality-based community formation; and as a “global collective memory, allowing people to contribute, store, and annotate comments” (Radin 2006 , 593), facilitating alternative sexual storytelling. Accordingly, our respondents’ explorations ranged from information on how to “do sex,” to how people think about and label themselves sexually, to how to get sexual pleasure or give it to others, to topics like consent, disease, and activism; many also reported using online explorations to assess where they stood in terms of “normal” physical and sexual development.

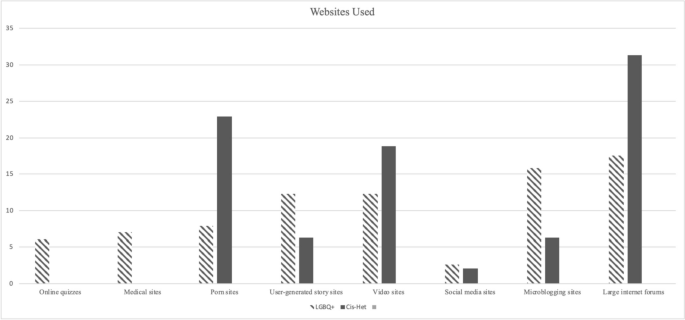

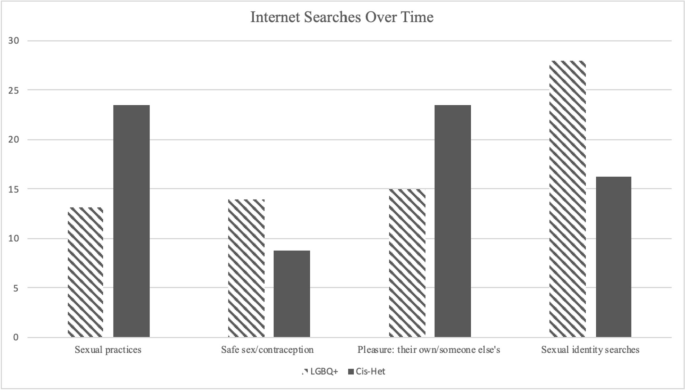

Unlike school-based sexual learning, online explorations were not dominated by any “master” script, but involved a youth’s transformation from “being exclusively an actor trained in his or her role(s)” to “being a partial scriptwriter or adaptor,” as Simon and Gagnon ( 1986 , 99) describe interpersonal scripting. Respondents went all over the Internet for sex- and sexuality-related content. In Fig. 3 we have grouped these sites into various categories that our respondents used for learning online. We asked our interviewees what websites they accessed and what they remembered learning online; the answers showed widely ranging exploration. They reported taking online sex quizzes on Buzzfeed (“15 Things You Need to Know About Your Sex Life”), looking at medical sites (for “information about asexuality and attraction”) and sexuality education sites (such as Scarleteen, “a one-stop shop for LGBQ youth”), consulting Wikipedia and Google (for instance, for articles on “how to make out or give a blow job,”) watching porn sites (such as PornHub); enjoying fan fiction (Wattpad) and “smut” fan fiction (“it’s just like porn but it’s words”) on user-generated story sites; watching video sites (such as You Tube videos on sex positions, “the arousal of the vulva,” and masturbation, and TED Talks about the effects of porn), spending time on social networking sites (such as Grindr), in video chat rooms, on microblogging and networking sites (such as Tumbir), and in large online forums like Yahoo and Autostraddle.

Websites Used

Julia, quoted earlier, who identified as queer in middle school, described their explorations in a way that echoed throughout our interviews: secretive, exciting, voracious, and curiosity-driven.