EDITORIAL article

Editorial: emotional intelligence: current research and future perspectives on mental health and individual differences.

- 1 Giovanni Maria Bertin Department of Education Studies, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- 2 Department of Management, College of Business, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, United States

- 3 Department of Psychology, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Editorial on the Research Topic Emotional intelligence: Current research and future perspectives on mental health and individual differences

The last two decades have seen a steadily growing interest in emotional intelligence (EI) research and its applications. As a side effect of this boom in research activity, a flood of conceptualizations and measures of EI have been introduced. Consequently, the label “EI” has been used for a wide array of (often conflicting) models and measures, which has impeded consistent summaries of empirical evidence. This confusion among models/measures is problematic because different measurement approaches produce different results, which makes it difficult to theorize what EI really is or what it predicts since there is limited consistency in the empirical data. On one side there are proponents of the ability model (see Mayer et al., 2016 ) which recognizes that EI includes four distinct types of ability and defines EI as the ability to perceive and integrate emotion to facilitate thoughts, understand and regulate emotions to promote personal growth ( Mayer and Salovey, 1997 ). This kind of EI would only be measurable through maximum performance tests. On the opposite side, we find supporters of the trait model. In particular, Petrides et al. (2007) defines trait EI as a constellation of emotional perceptions assessed through questionnaires and rating scales. The theory of trait EI is summarized with applications from the domains of clinical, educational, and organizational psychology ( Petrides et al., 2016 ) and it's clearly distinguished from the notion of EI as a cognitive ability. Of course, there is no scarcity of other models and perspectives of EI, including mixed approaches, often used in professional setting to train and evaluate management potential and skills, that consider EI as a broad concept that includes (among others) motivations, interpersonal and intrapersonal abilities, empathy, personality factors and wellbeing (see Mayer et al., 2008 ).

In accordance with Hughes and Evans (2018) , we argue that various conceptualizations of EI may be considered constituents of existing perspectives of cognitive ability (ability EI), personality (trait EI), emotion regulation (EI competencies), and emotional awareness (the aptitude to conceptualize and describe one's own emotions and those of others). Across all models, EI involves handling emotions and putting them at the disposal of thinking activity. Although EI is an ability to understand and control emotions in general, this is only a small part of some models of EI. Indeed, trait EI concerns our perceptions of our emotional world and comprises a broad collection of traits linked to the opportunity of understanding, managing, and utilizing our own and other people's emotions, helping us figure out and dealing with emotional and social situations. All these facets are critical for intelligent behavior because they enable and facilitate our capacities for resilience, communication, and reasoning, to name a few, across the life span. Indeed, existing literature suggests that individual differences in EI consistently predict human behavior and EI is now recognized by the scientific community as a relevant psychological factor for several important real-life domains, including a successful socialization, community mental health and individual wellbeing. To advance the field both theoretically and practically, this special issue aims to provide new data which may help to critically review EI's theory.

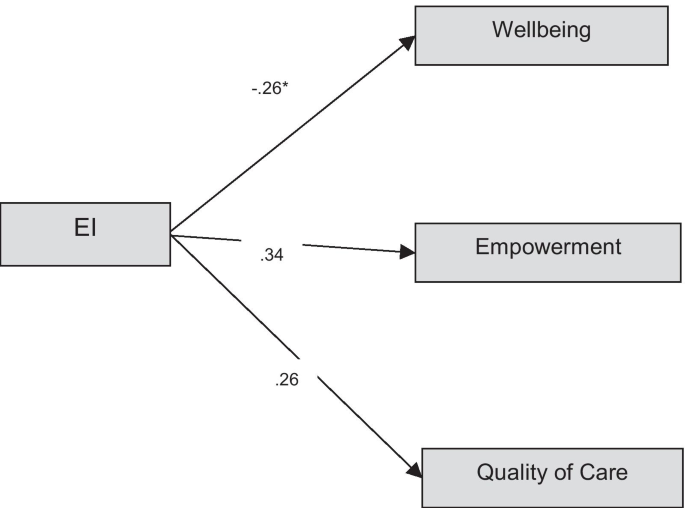

The collection of articles is quite diverse and covers a number of issues relevant to an advancement of the field by including participants from several cultural contexts (e.g., Italian, Brazilian, and Turkish). Seven articles used self-report tools for the assessment of EI, while only two studies employed an ability measure (the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test). With regards to the topic being addressed, one study focuses on psychometrics, and confirms the validity of the Trait EI Questionnaire as an assessment tool for trait EI in a large Brazilian sample ( Zuanazzi et al. ), while seven analyzed the relationship between EI and research questions pertaining the domain of psychological health and wellbeing. Among these, the papers by García-Martínez et al. and Kökçam et al. analyze instead the relationship between EI and stress management in university students. García-Martínez et al. found mixed results compared to existing literature on the path from EI and academic achievement, while Kökçam et al. found that EI plays an important role in the identification of stress profiles.

Through a systematic review Pérez-Fernández et al. highlights that EI may be a protective factor of emotional disorders in general population and offers a starting point for a theoretical and practical understanding of the role played by EI in the management of diabetes. Along these lines Sergi et al. showed that the domains of EI involved in emotion recognition and control in the social context to reduce the risk to be affected by depression and anxiety, while Pulido-Martos et al. show the contribution of socioemotional resources (including EI) to the preservation of mental health. Iqbal et al. considered the associations among EI, relational engagement (RE) and cognitive outcomes (COs) and found that EI directly and indirectly influenced COs during the pandemic: the students with higher levels of EI and RE may achieve better COs.

Last, the two articles using the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test show that coping strategies mediate the relationships of ability EI with both well- and ill-being ( MacCann et al. ), and give some preliminary evidence on the associations between ability EI, attachment security, and reflective functioning ( Rosso ).

Despite their specific aims, these studies demonstrate the importance to stake on individuals' EI to favor a high psychological and physical wellbeing. At the same time, the present articles collection highlights some open issues to be addressed by future research, including: putting order and possibly connecting the existence of many conflicting models and related measures of EI; deepen the study of the relation between EI with other partially overlapping constructs; identify the most helpful training to increase EI in individuals of all ages, such as children and their parents, adolescents, adults.

Author contributions

GM and FA drafted the editorial. RB, DJ, and ET participated in the discussion on the ideas presented and have edited and supervised the editorial. All authors approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Hughes, D. J., and Evans, T. R. (2018). Putting ‘emotional intelligences' in their place: introducing the integrated model of affect-related individual differences. Front. Psychol. 9, 2155. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02155

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., and Salovey, P. (2016). The ability model of emotional intelligence: principles and updates. Emot. Rev . 8, 290–300. doi: 10.1177/1754073916639667

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mayer, J. D., Roberts, R. D., and Barsade, S. G. (2008). Human abilities: emotional intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol . 59, 507–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093646

Mayer, J. D., and Salovey, P. (1997). “What is emotional intelligence?,” in Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Educators , eds P. Salovey and D. Sluyter (New York, NY: Basic Books), 3–31.

Google Scholar

Petrides, K. V., Mikolajczak, M., Mavroveli, S., Sanchez-Ruiz, M.-J., Furnham, A., and Pérez-González, J.-C. (2016). Developments in trait emotional intelligence research. Emot. Rev . 8, 335–341. doi: 10.1177/1754073916650493

Petrides, K. V., Pita, R., and Kokkinaki, F. (2007). The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. Br. J. Psychol. 98, 273–289. doi: 10.1348/000712606X120618

Keywords: emotional intelligence, mental health, psychological wellbeing, individual differences, emotions

Citation: Mancini G, Biolcati R, Joseph D, Trombini E and Andrei F (2022) Editorial: Emotional intelligence: Current research and future perspectives on mental health and individual differences. Front. Psychol. 13:1049431. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1049431

Received: 20 September 2022; Accepted: 04 October 2022; Published: 13 October 2022.

Edited and reviewed by: Stefano Triberti , University of Milan, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Mancini, Biolcati, Joseph, Trombini and Andrei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giacomo Mancini, giacomo.mancini7@unibo.it

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Emotional Intelligence Measures: A Systematic Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Basic Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Speech Therapy, Universitat de València, 46010 Valencia, Spain.

- 2 Psychology Research Institute, Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Lima 15102, Peru.

- 3 Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal, San Miguel 15088, Peru.

- PMID: 34946422

- PMCID: PMC8701889

- DOI: 10.3390/healthcare9121696

Emotional intelligence (EI) refers to the ability to perceive, express, understand, and manage emotions. Current research indicates that it may protect against the emotional burden experienced in certain professions. This article aims to provide an updated systematic review of existing instruments to assess EI in professionals, focusing on the description of their characteristics as well as their psychometric properties (reliability and validity). A literature search was conducted in Web of Science (WoS). A total of 2761 items met the eligibility criteria, from which a total of 40 different instruments were extracted and analysed. Most were based on three main models (i.e., skill-based, trait-based, and mixed), which differ in the way they conceptualize and measure EI. All have been shown to have advantages and disadvantages inherent to the type of tool. The instruments reported in the largest number of studies are Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i), Schutte Self Report-Inventory (SSRI), Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test 2.0 (MSCEIT 2.0), Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS), Wong and Law's Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS), and Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue). The main measure of the estimated reliability has been internal consistency, and the construction of EI measures was predominantly based on linear modelling or classical test theory. The study has limitations: we only searched a single database, the impossibility of estimating inter-rater reliability, and non-compliance with some items required by PRISMA.

Keywords: emotional intelligence; measure; questionnaire; scale; systematic review; test.

Publication types

Emotional Intelligence as an Ability: Theory, Challenges, and New Directions

- Open Access

- First Online: 14 July 2018

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Marina Fiori 6 &

- Ashley K. Vesely-Maillefer 6

Part of the book series: The Springer Series on Human Exceptionality ((SSHE))

38k Accesses

35 Citations

11 Altmetric

- The original version of this chapter was revised. The correction to this chapter is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90633-1_17

About 25 years ago emotional intelligence (EI) was first introduced to the scientific community. In this chapter, we provide a general framework for understanding EI conceptualized as an ability. We start by identifying the origins of the construct rooted in the intelligence literature and the foundational four-branch model of ability EI, then describe the most commonly employed measures of EI as ability, and critically review predictive validity evidence. We further approach current challenges, including the difficulties of scoring answers as “correct” in the emotional sphere, and open a discussion on how to increase the incremental validity of ability EI. We finally suggest new directions by introducing a distinction between a crystallized component of EI, based on knowledge of emotions, and a fluid component, based on the processing of emotion information.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Current Concepts in the Assessment of Emotional Intelligence

Rasch model analysis of the Situational Test of Emotional Understanding – brief in a large Portuguese sample

Working memory updating of emotional stimuli predicts emotional intelligence in females

- Emotional intelligence

- Crystallized EI

- Emotion information processing

- Emotion knowledge

Research in the domains of psychology, education, and organizational behavior in the past 30 years has been characterized by a resurgence of interest for emotions, opening the door to new conceptualizations of intelligence that point to the role of emotions in guiding intelligent thinking (e.g., Bower, 1981 ; Zajonc, 1980 ). Earlier work often raised concern surrounding the compatibility between logic and emotion, and the potential interference of emotion in rational behavior, as they were considered to be in “opposition” (e.g., Lloyd, 1979 ). Research shifted into the study of how cognition and emotional processes could interact to enhance thinking, in which context Salovey and Mayer first introduced the construct of emotional intelligence (EI). Their initial definition described EI as the “ability to monitor one’s own and other’s feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions” (Salovey & Mayer, 1990 , p. 189).

The definition of EI was heavily influenced by early work focused on describing, defining, and assessing socially competent behavior such as social intelligence (Thorndike, 1920 ). The attempt to understand social intelligence led to further inquiries by theorists such as Gardner ( 1983 ) and Sternberg ( 1988 ), who proposed more inclusive approaches to understanding general intelligence. Gardner’s concepts of intrapersonal intelligence , namely, the ability to know one’s emotions, and interpersonal intelligence, which is the ability to understand other individuals’ emotions and intentions, aided in the development of later models in which EI was originally introduced as a subset of social intelligence (Salovey & Mayer, 1990 ). Further prehistory to EI involved the investigation of the relation of social intelligence to alexithymia , a clinical construct defined by difficulties recognizing, understanding, and describing emotions (e.g., MacLean, 1949 ; Nemiah, Freyberger, & Sifneos, 1976 ), as well as research examining the ability to recognize facial emotions and expressions (Ekman, Friesen, & Ancoli, 1980 ).

EI was popularized in the 1990s by Daniel Goleman’s ( 1995 ) best-selling book, Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ , as well as through a number of other popular books (e.g., Cooper & Sawaf, 1997 ). However, the lack of empirical evidence available at the time to support the “exciting” statements and claims about the importance of EI in understanding human behavior and individual differences (Davies, Stankov, & Roberts, 1998 ) prompted critiques and further investigation into the construct. Major psychological factors such as intelligence, temperament, personality, information processing, and emotional self-regulation have been considered in the conceptualization of EI, leading to a general consensus that EI may be multifaceted and could be studied from different perspectives (Austin, Saklofske, & Egan, 2005 ; Stough, Saklofske, & Parker, 2009 ; Zeidner, Roberts, & Matthews, 2008 ).

Two conceptually different approaches dominate the current study of EI: the trait and the ability approach (Petrides & Furnham, 2001 ). The trait approach conceives EI as dispositional tendencies, such as personality traits or self-efficacy beliefs (see Petrides, Sanchez-Ruiz, Siegling, Saklofske, & Mavroveli, Chap. 3 , this volume). This approach is often indicated in the literature as also including “mixed” models, although such models are conceptually distinct from conceptions of EI as personality because they consider EI as a mixture of traits, competences, and abilities (e.g., Bar-On, 2006 ; Goleman, 1998 ). Both the trait approach and the “mixed” models share the same measurement methods of EI, namely, self-report questionnaires. In contrast, the ability approach conceptualizes EI as a cognitive ability based on the processing of emotion information and assesses it with performance tests. The current chapter deals with the latter approach, where we first outline Mayer and Salovey’s ( 1997 ) foundational four-branch ability EI model, then describe commonly used and new measures of EI abilities, critically review evidence of EI’s predictive validity, and finally discuss outstanding challenges, suggesting new directions for the measurement and conceptualization of EI as an ability.

Although not the focus of the present contribution, it should be noted that some attempts to integrate both ability and trait EI perspectives exist in the literature, including the multi-level developmental investment model (Zeidner, Matthews, Roberts, & MacCann, 2003 ) and the tripartite model (Mikolajczak, 2009 ). For example, the tripartite model suggests three levels of EI: (1) knowledge about emotions, (2) ability to apply this knowledge in real-world situations, and (3) traits reflecting the propensity to behave in a certain way in emotional situations (typical behavior). Research and applications on this tripartite model are currently underway (e.g., Laborde, Mosley, Ackermann, Mrsic, & Dosseville, Chap. 11 , this volume; Maillefer, Udayar, Fiori, submitted ). More theory and research is needed to elucidate how the different EI approaches are related with each other. What all of these theoretical frameworks share in common is their conceptualization of EI as a distinct construct from traditional IQ and personality, which facilitates the potential for prediction of, and influence on, various real-life outcomes (Ciarrochi, Chan, & Caputi, 2000 ; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2008 ; Petrides, Perez-Gonzalez, & Furnham, 2007 ).

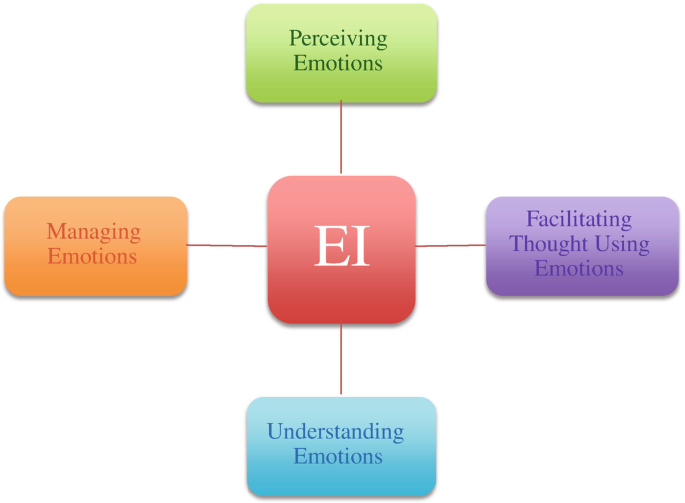

The Four-Branch Ability EI Model

The main characteristic of the ability approach is that EI is conceived as a form of intelligence. It specifies that cognitive processing is implicated in emotions, is related to general intelligence, and therefore ought to be assessed through performance measures that require respondents to perform discrete tasks and solve specific problems (Freeland, Terry, & Rodgers, 2008 ; Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 2016 ; Mayer & Salovey, 1997 ). The mainstream model of EI as an ability is the four-branch model introduced by Mayer and Salovey ( 1997 ), which has received wide acknowledgment and use and has been foundational in the development of other EI models and measures. The four-branch model identifies EI as being comprised of a number of mental abilities that allow for the appraisal, expression, and regulation of emotion, as well the integration of these emotion processes with cognitive processes used to promote growth and achievement (Salovey & Grewal, 2005 ; Salovey & Mayer, 1990 ). The model is comprised of four hierarchically linked ability areas, or branches: perceiving emotions, facilitating thought using emotions, understanding emotions, and managing emotions (see Fig. 2.1 ).

The Mayer and Salovey ( 1997 ) four-branch model of emotional intelligence (EI) abilities

Perceiving emotions (Branch 1) refers to the ability to identify emotions accurately through the attendance, detection, and deciphering of emotional signals in faces, pictures, or voices (Papadogiannis, Logan, & Sitarenios, 2009 ). This ability involves identifying emotions in one’s own physical and psychological states, as well as an awareness of, and sensitivity to, the emotions of others (Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 1999 ; Papadogiannis et al., 2009 ).

Facilitating thought using emotions (Branch 2) involves the integration of emotions to facilitate thought. This occurs through the analysis of, attendance to, or reflection on emotional information, which in turn assists higher-order cognitive activities such as reasoning, problem-solving, decision-making, and consideration of the perspectives of others (Mayer & Salovey, 1997 ; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2002 ; Papadogiannis et al., 2009 ). Individuals with a strong ability to use emotions would be able to select and prioritize cognitive activities that are most conducive to their current mood state, as well as change their mood to fit the given situation in a way that would foster better contextual adaptation.

Understanding emotions (Branch 3) comprises the ability to comprehend the connections between different emotions and how emotions change over time and situations (Rivers, Brackett, Salovey, & Mayer, 2007 ). This would involve knowledge of emotion language and its utilization to identify slight variations in emotion and describe different combinations of feelings. Individuals stronger in this domain understand the complex and transitional relationships between emotions and can recognize emotional cues learned from previous experiences, thus allowing them to predict expressions in others in the future (Papadogiannis et al., 2009 ). For example, an understanding that a colleague is getting frustrated, through subtle changes in tone or expression, can improve individuals’ communication in relationships and their personal and professional performances.

Finally, managing emotions (Branch 4) refers to the ability to regulate one’s own and others’ emotions successfully. Such ability would entail the capacity to maintain, shift, and cater emotional responses, either positive or negative, to a given situation (Rivers et al., 2007 ). This could be reflected in the maintenance of a positive mood in a challenging situation or curbing elation at a time in which an important decision must be made. Recovering quickly from being angry or generating motivation or encouragement for a friend prior to an important activity are illustrations of high-level emotion management (Papadogiannis et al., 2009 ).

The four EI branches are theorized to be hierarchically organized, with the last two abilities (understanding and management), which involve higher-order (strategic) cognitive processes, building on the first two abilities (perception and facilitation), which involve rapid (experiential) processing of emotion information (Mayer & Salovey, 1997 ; Salovey & Grewal, 2005 ). It should be noted that the proposed hierarchical structure of the model, as well as its four distinctive branches, have been contradicted. First, developmental evidence suggests that abilities in different EI domains (e.g., perceiving, managing) are acquired in parallel rather than sequentially, through a complex learning process involving a wide range of biological and environmental influences (Zeidner et al., 2003 ). Though this conceptualization supports the notion that lower-level competencies aid in the development of more sophisticated skills, it also identifies ways in which the four EI branches are sometimes developed simultaneously, with lower-level abilities of perceiving, facilitating, understanding, and managing emotions at the same time leading to their later improvement.

The four-branch model has also been challenged through factor analysis in several cases, which did not support a hierarchical model with one underlying global EI factor (Fiori & Antonakis, 2011 ; Rossen, Kranzler, & Algina, 2008 ). Moreover, facilitating thought using emotions (Branch 2) did not emerge as a separate factor and was found to be empirically redundant with the other branches (Fan, Jackson, Yang, Tang, & Zhang, 2010 ; Fiori et al., 2014 ; Fiori & Antonakis, 2011 ; Gignac, 2005 ; Palmer, Gignac, Manocha, & Stough, 2005 ), leading scholars to adopt a revised three-branch model of ability EI, comprised of emotion recognition, emotion understanding, and emotion management (Joseph & Newman, 2010 ; MacCann, Joseph, Newman, & Roberts, 2014 ). Nevertheless, the four branches remain the foundation for current ability EI models, and their description aids in the theoretical understanding of the content domains covered by ability-based perspectives on EI (Mayer et al., 2016 ).

Measurement of EI Abilities

How ability EI is measured is critically important to how the results are interpreted. The fact that ability EI is measured by maximum-performance tests, as is appropriate for a form of intelligence, instead of self-report questionnaires, as is the case for trait EI (see Petrides et al., Chap. 3 , this volume) can, in itself, lead to different results (Brackett, Rivers, Shiffman, Lerner, & Salovey, 2006 ). This is analogous to asking people to provide evidence of their intelligence by utilizing a performance IQ measure versus asking them how high they think their IQ is. Although most individuals have insight with regard to their own abilities, there are those who do not. There are, of course, others who over- or underestimate their intelligence unintentionally or for social desirability purposes, resulting in different scores depending on the format of measurement. Thus, it would be challenging to determine whether the results are attributable to the construct itself or to the assessment methods that are being used (MacCann & Roberts, 2008 ).

Though this example is referring to empirically acknowledged problems with self-report measures in general, reflected in vulnerability to faking, social desirability, and ecological validity (Grubb & McDaniel, 2007 ; Roberts, Zeidner, & Matthews, 2007 ), problems with performance measures of EI that may alter the response outcome also exist. For instance, typical ability EI items require individuals to demonstrate their “ability” to perceive, use, understand, and manage emotions by responding to a variety of hypothetical scenarios and visual stimuli, thus deeming the incorrect/correct response format as a method of scoring. Although this may correlate with real-life outcomes, it may not be an accurate representation of EI in real-life social interactions (Vesely, 2011 ; Vesely-Maillefer, 2015 ).

With these considerations in mind , we provide below a short description of the most commonly used as well as some newly developed tests to measure EI abilities.

The Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test

The Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT; Mayer et al., 2002 ; Mayer, Salovey, Caruso, & Sitarenios, 2003 ) is the corresponding measure of the dominant-to-date four-branch theoretical model of ability EI (Mayer & Salovey, 1997 ). This is a performance-based measure that provides a comprehensive coverage of ability EI by assessing how people perform emotion tasks and solve emotional problems. It assesses the four EI branches with 141 items distributed across eight tasks (two tasks per branch). Perceiving emotions (Branch 1) is assessed with two emotion perception tasks: (1) the faces task involves identifying emotions conveyed through expressions in photographs of people’s faces; and (2) the pictures task involves identifying emotions in pictures of landscapes and abstract art. For both tasks, respondents are asked to rate on a 5-point scale the degree to which five different emotions are expressed in each stimulus. Facilitating thought (Branch 2) is assessed with two tasks: (1) the facilitation task involves evaluating how different moods may facilitate specific cognitive activities; and (2) the sensations task involves comparing emotions to other sensations, such as color, light, and temperature. For both tasks, respondents are asked to indicate which of the different emotions best match the target activity/sensation. Understanding emotions (Branch 3) is assessed with two multiple-choice tests: (1) the changes test involves questions about how emotions connect to certain situations and how emotions may change and develop over time; and (2) the blends test involves questions about how different emotions combine and interact to form new emotions. For both tests, respondents are asked to choose the most appropriate of five possible response options. Managing emotions (Branch 4) is assessed with two situational judgment tests (SJTs) using a series of vignettes depicting real-life social and emotional situations: (1) the emotion management test involves judgments about strategies for regulating the protagonist’s own emotions in each situation; and (2) the emotional relations test involves judgments about strategies for managing emotions within the protagonist’s social relationships. For both tests, respondents are asked to rate the level of effectiveness of several different strategies, ranging from 1 = very ineffective to 5 = very effective.

The MSCEIT assessment yields a total EI score, four-branch scores, and two area scores for experiential EI (Branches 1 and 2 combined) and strategic EI (Branches 3 and 4 combined). Consistent with the view of EI as a cognitive ability , the scoring of item responses follows the correct/incorrect format of an ability-based IQ test while also requiring the individual to be attuned to social norms (Salovey & Grewal, 2005 ). The correctness of the MSCEIT responses can be determined in one of two ways: (a) based on congruence with the answers of emotion experts (expert scoring) or (b) based on the proportion of the sample that endorsed the same answer (general consensus scoring) (Mayer et al., 2003 ; Papadogiannis et al., 2009 ; Salovey & Grewal, 2005 ). Mayer et al. ( 2003 ) reported high agreement between the two scoring methods in terms of correct answers ( r = 0.91) and test scores ( r = 0.98). The test internal consistency reliability (split half) is r = 0.91–0.93 for the total EI and r = 0.76–0.91 for the four-branch scores, with expert scoring producing slightly higher reliability estimates (Mayer et al., 2003 ).

The MSCEIT has been the only test available to measure EI as an ability for a long time, and much of the existing validity evidence on ability EI, which we review in the next section, is based on the MSCEIT, introducing the risk of mono-method bias in research. Although there are other standardized tests that can be used to measure specific EI abilities (described below), the MSCEIT remains the only omnibus test to measure all four branches of the ability EI model in one standardized assessment. Another attractive feature of the MSCEIT is the availability of a matching youth research version (MSCEIT-YRV; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2005 ; Rivers et al., 2012 ), which assesses the same four EI branches using age-appropriate items for children and adolescents (ages 10–17). However, a major barrier to research uses of the MSCEIT and its derivatives is that these tests are sold commercially and scored off-site by the publisher, Multi-Health Systems Inc. Furthermore, the MSCEIT has several well-documented psychometric limitations (Fiori et al., 2014 ; Fiori & Antonakis, 2011 ; Maul, 2012 ; Rossen et al., 2008 ), which have prompted researchers to develop alternative instruments, to generalize findings across assessments , and to create non-commercial alternatives for research.

Tests of Emotion Understanding and Management

Recently, there has been an important advancement in ability EI measurement: the introduction of a second generation of ability EI tests, notably the Situational Test of Emotional Understanding (STEU) and the Situational Test of Emotion Management (STEM) introduced by MacCann and Roberts ( 2008 ). Both the STEU and the STEM follow the SJT format similar to that used for the managing emotions branch of the MSCEIT, where respondents are presented with short vignettes depicting real-life social and emotional situations (42 on the STEU and 44 on the STEM) and asked to select, among a list of five, which emotion best describes how the protagonist would feel in each situation (STEU) or which course of action would be most effective in managing emotions in each situation (STEM). Correct answers on the STEU are scored according to Roseman’s (2001) appraisal theory (theory-based scoring), and correct answers on the STEM are scored according to the judgments provided by emotion experts (expert scoring). The reliability of the two tests is reported to be between alpha = 0.71 and 0.72 for STEU and between alpha = 0.68 and 0.85 for STEM (Libbrecht & Lievens, 2012 ; MacCann & Roberts, 2008 ). Brief forms of both tests (18–19 items) have also been developed for research contexts where comprehensive assessment of EI is not required (Allen et al., 2015 ). There is also an 11-item youth version of the STEM (STEM-Y; MacCann, Wang, Matthews, & Roberts, 2010 ) adapted for young adolescents. The STEU and STEM items are available free of charge in the American Psychological Association PsycTESTS database (see also https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012746.supp ). These tests look promising, although they have been introduced recently and more research is needed to ascertain their construct and predictive validity (but see Burrus et al., 2012 ; Libbrecht & Lievens, 2012 ; Libbrecht, Lievens, Carette, & Côté, 2014 ).

The text-based format of the SJT items on the STEU, STEM, and MSCEIT raises concerns about their ecological validity, as real-life social encounters require judgments of verbal as well as nonverbal cues . To address this concern, MacCann, Lievens, Libbrecht, and Roberts ( 2016 ) recently developed a multimedia test of emotion management, the 28-item multimedia emotion management assessment (MEMA) , by transforming the original text-based scenarios and response options from the STEM into a video format. MacCann et al.’s ( 2016 ) comparisons of the MEMA with the text-based items from the MSCEIT managing emotions branch produced equivalent evidence of construct and predictive validity for the two tests.

Tests of Emotion Perception

There are several long-existing standardized measures of perceptual accuracy in recognizing emotions, many of which were introduced even before the construct of EI. Therefore, these were not presented as EI tests but do capture the perceiving emotions branch of EI and could be considered as viable alternatives to the MSCEIT. Among the most frequently used of these tests are the Diagnostic Analysis of Nonverbal Accuracy (DANVA ; Nowicki & Duke 1994 ), the Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity (PONS ; Rosenthal, Hall, DiMatteo, Rogers, & Archer, 1979 ), and the Japanese and Caucasian Brief Affect Recognition Test (JACBART ; Matsumoto et al., 2000 ). Like the MSCEIT faces task, these tests involve viewing a series of stimuli portraying another person’s emotion, and the respondent’s task is to correctly identify the emotion expressed. However, unlike the rating-scale format of the MSCEIT faces items, these other tests use a multiple-choice format, where respondents must choose one emotion, from a list of several, that best matches the stimulus. This difference in response format could be one possible reason why performance on the MSCEIT perceiving branch shows weak convergence with these other emotion recognition tests (MacCann et al., 2016 ).

Different emotion recognition tests use different types of stimuli and modalities (e.g., photos of faces, audio recordings) and cover different numbers of target emotions. For example, the DANVA uses 24 photos of male and female facial expressions and 24 audio recordings of male and female vocal expressions of the same neutral sentence (“I am going out of the room now but I’ll be back later”), representing 1 of 4 emotions (happiness, sadness, anger, and fear) in 2 intensities, either weak or strong. The PONS is presented as a test assessing interpersonal sensitivity, or the accuracy in judging other people’s nonverbal cues and affective states. It includes 20 short audio and video segments of a woman for a total length of 47 minutes. The task is to identify which of two emotion situations best describes the woman’s expression. The JACBART uses 56 pictures of Japanese and Caucasian faces expressing 1 of 5 emotions (fear, happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, contempt, and disgust). The interesting feature of this test, in comparison to others, is that it employs a very brief presentation time (200 ms). Each expressive picture is preceded and followed by the neutral version of the same person expressing the emotion in the target picture, so as to reduce post effects of the pictures and get a more spontaneous evaluation of the perceived emotion.

Both the MSCEIT perceiving branch and the earlier emotion recognition tests have been critiqued for their focus on a single modality (i.e., still photos vs. audio recordings), as well as for their restricted range of target emotions (i.e., few basic emotions, only one of them positive), which limits their ecological validity and precludes assessing the ability to differentiate between more nuanced emotion states (Schlegel, Fontaine, & Scherer, 2017 ; Schlegel, Grandjean, & Scherer, 2014 ). The new wave of emotion recognition tests developed at the Swiss Center for Affective Sciences – the Multimodal Emotion Recognition Test (MERT ; Bänziger, Grandjean, & Scherer, 2009 ) and the Geneva Emotion Recognition Test (GERT ; Schlegel et al., 2014 ) – aim to rectify both problems by employing more ecologically valid stimuli, involving dynamic multimodal (vocal plus visual) portrayals of 10 (MERT) to 14 (GERT) different emotions, half of them positive. For example, the GERT consists of 83 videos (1–3 s long) of professional male and female actors expressing 14 emotions (joy, amusement, pride, pleasure, relief, interest, anger, fear, despair, irritation, anxiety, sadness, disgust, and surprise) through facial expressions, nonverbal gestural/postural behavior, and audible pseudo-linguistic phrases that resemble the tone of voice of the spoken language. A short version (GERT-S) is also available with 42 items only (Schlegel & Scherer, 2015 ). The reliability is 0.74 for the long version. The emerging evidence for the construct and predictive validity of the GERT looks promising (Schlegel et al., 2017 ).

Predictive Validity of Ability EI

Among the most researched and debated questions in the ability EI literature is whether ability EI can predict meaningful variance in life outcomes – does ability EI matter? (Antonakis, Ashkanasy, & Dasborough, 2009 ; Brackett, Rivers, & Salovey, 2011 ; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2008 ). Several studies have shown that ability EI predicts health-related outcomes, including higher satisfaction with life, lower depression, and fewer health issues (Fernández-Berrocal & Extremera, 2016 ; Martins, Ramalho, & Morin, 2010 ). Furthermore, high EI individuals tend to be perceived by others more positively because of their greater social-emotional skills (Fiori, 2015 ; Lopes, Cote, & Salovey, 2006 ) and thus enjoy better interpersonal functioning in the family (Brackett et al., 2005 ), at work (Côte & Miners, 2006 ), and in social relationships (Brackett et al., 2006 ). Ability EI has also been positively implicated in workplace performance and leadership (Côte, Lopes, Salovey, & Miners, 2010 ; O’Boyle, Humphrey, Pollack, Hawver, & Story, 2011 ).

Evidence for ability EI predicting academic success is mixed in post-secondary settings (see Parker, Taylor, Keefer, & Summerfeldt, Chap. 16 , this volume) but more consistent for secondary school outcomes, where ability EI measures have been associated with fewer teacher-rated behavioral and learning problems and higher academic grades (Ivcevic & Brackett, 2014 ; Rivers et al., 2012 ). There is also compelling evidence from over 200 controlled studies of school-based social and emotional learning (SEL) programs, showing that well-executed SEL programs reduce instances of behavioral and emotional problems and produce improvements in students’ academic engagement and grades (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011 ; see also Elias, Nayman, & Duffell, Chap. 12 , this volume). Hoffmann, Ivcevic, and Brackett (Chap. 7 , this volume) describe one notable example of such evidence-based SEL program, the RULER approach , which is directly grounded in the four-branch ability EI model.

Although these results are certainly encouraging regarding the importance of ability EI as a predictor of personal, social, and performance outcomes, there are several important caveats to this conclusion. First, ability EI measures may capture predominantly the knowledge aspects of EI, which can be distinct from the routine application of that knowledge in real-life social-emotional interaction. This disconnect between emotional knowledge and application of knowledge is also supported by the tripartite model of EI mentioned above (Mikolajczak, 2009 ), which separates the ability-based knowledge from trait-based applications within its theory. For example, it posits the possibility that a person with strong cognitive knowledge and verbal ability can describe which emotional expression would be useful in a given situation, but may not be able to select or even display the corresponding emotion in a particular social encounter. Indeed, many other factors, apart from intelligence, contribute to people’s actual behavior, including personality, motives, beliefs, and situational influences.

This leads to the second caveat: whether ability EI is distinct enough from other established constructs, such as personality and IQ, to predict incremental variance in outcomes beyond these well-known variables. Although the overlap of EI measures with known constructs is more evident for trait EI measures (Joseph, Jin, Newman, & O’Boyle, 2015 ), some studies have shown that a substantial amount of variance in ability EI tests, in particular the MSCEIT, was predicted by intelligence, but also by personality traits, especially the trait of agreeableness (Fiori & Antonakis, 2011 ). These results suggest that ability EI, as measured with the MSCEIT, pertains not only to the sphere of emotional abilities, as it was originally envisioned, but depends also on one’s personality characteristics, which conflicts with the idea that ability EI should be conceived (and measured) solely as a form of intelligence. Given these overlaps, the contribution of ability EI lowers once personality and IQ are accounted for. For example, the meta-analysis by Joseph and Newman ( 2010 ) showed that ability EI provided significant but rather limited incremental validity in predicting job performance over personality and IQ.

Of course, one may argue that even a small portion of incremental variance that is not accounted for by known constructs is worth the effort. Further and indeed, a more constructive reflection on the role of ability EI in predicting various outcomes refers to understanding why its contributions may have been limited so far. The outcomes predicted by ability EI should be emotion-specific, given that it is deemed to be a form of intelligence that pertains to the emotional sphere. There is no strong rationale for expecting ability EI to predict generic work outcomes such as job performance; for this type of outcome, we already know that IQ and personality account for the most variance. Instead, work-related outcomes that involve the regulation of emotions, such as emotional labor, would be more appropriate. This idea is corroborated by the meta-analytic evidence showing stronger incremental predictive validity of ability EI for jobs high in emotional labor, such as customer service positions (Joseph & Newman, 2010 ; Newman, Joseph, & MacCann, 2010 ).

Another reason why the incremental validity of ability EI measures appears to be rather small may be related to the limits of current EI measures. For example, the MSCEIT has shown to be best suited to discriminate individuals at the low end of the EI ability distribution (Fiori et al., 2014 ). For the other individuals (medium and high in EI), variation in the MSCEIT scores does not seem to reflect true variation in EI ability. Given that most of the evidence on ability EI to date is based on the MSCEIT, it is likely that some incremental validity of ability EI was “lost” due to the limitations of the test utilized to measure it.

Another caveat concerns making inferences about predictive validity of ability EI from the outcomes of EI and SEL programs. Here, the issue is in part complicated by the fact that terms such as “ability” and “competence” are often used interchangeably, but in fact reflect different characteristics, the latter being a trait-like solidification of the former through practice and experience. Many EI programs are in fact meant to build emotional competence, going beyond the mere acquisition of emotional knowledge and working toward the application of that knowledge across different contexts. As such, other processes and factors, apart from direct teaching and learning of EI abilities, likely contribute to positive program outcomes. For example, the most effective school-based SEL programs are those that also modify school and relational environments in ways that would model, reinforce, and provide opportunities for students to practice the newly acquired EI skills in everyday situations (see also Elias et al., Chap. 12 , this volume; Humphrey, Chap. 8 , this volume). Thus, it would be inappropriate to attribute the outcomes of such programs solely to increases in students’ EI abilities, without acknowledging the supportive social and contextual influences.

It is also important to better understand which processes mediate the role of ability EI in improving individuals’ emotional functioning. Social cognitive theories of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997 ) and self-concept (Marsh & Craven, 2006 ) can inform which types of processes might be involved in linking ability to behavioral change. Specifically, successful acquisition and repeated practice of EI skills can build individuals’ sense of confidence in using those skills (i.e., higher perceived EI self-efficacy), which would increase the likelihood of drawing upon those skills in future situations, in turn providing further opportunities to hone the skills and reinforce the sense of self-competence (Keefer, 2015 ). Research on self-efficacy beliefs in one’s ability to regulate emotions supports this view (Alessandri, Vecchione, & Caprara, 2015 ).

Mayer et al. ( 2016 ) cogently summarized the ambivalent nature of predictive validity evidence for ability EI: “the prediction from intelligence to individual instances of “smart” behavior is fraught with complications and weak in any single instance. At the same time, more emotionally intelligent people have outcomes that differ in important ways from those who are less emotionally intelligent” (p. 291). We concur with this conclusion but would treat it as tentative, given that there are several unresolved issues with the way ability EI has been measured and conceptualized, as discussed below. This opens the possibility that EI’s predictive validity would improve once these measurement and theoretical issues have been clarified.

Measurement and Conceptual Issues

Scoring of correct responses.

One of the greatest challenges of operationalizing EI as an ability has been (and still is) how to score a correct answer on an ability EI test. Indeed, in contrast to personality questionnaires in which answers depend on the unrestricted choice of the respondent and any answer is a valid one, ability test responses are deemed correct or wrong based on an external criterion of correctness. Among the most problematic aspects is the identification of such criterion; it is difficult to find the one best way across individuals who may differ with respect to how they feel and manage emotions effectively (Fiori et al., 2014 ). After all, the very essence of being intelligent implies finding the best solution to contextual adaptation given the resources one possesses. For example, one may be aware that, in principle, a good way to deal with a relational conflict is to talk with the other person to clarify the sources of conflict and/or misunderstanding. However, if one knows they and/or their partner are not good at managing interpersonal relationships , one may choose to avoid confrontation as a more effective strategy in the moment, given the personal characteristics of the individuals involved (Fiori et al., 2014 ).

This example evokes another issue that has not been addressed in the literature on ability EI, namely, the potential difference between what response would be more “intelligent” personally versus socially. One may argue that the solution should fill both needs; however, these may be in contradiction. For instance, suppression of one’s own feelings may help to avoid an interpersonal conflict, an action seen as socially adaptive ; however, this same strategy maybe personally unhealthy if the person does not manage their suppressed emotion in other constructive ways. In this case, a more socially unacceptable response that releases emotion may have been more “emotionally intelligent” as it relates to the self but less so as it relates to others. The problematic part is that current measurement tools do not take these nuances into account. This relates also to the lack of distinction in the literature on emotion skills related to the “self” versus “others,” a criticism discussed below.

In addition, “correctness” of an emotional reaction may depend on the time frame within which one intends to pursue a goal that has emotional implications. For example, if a person is focused on the short-term goal of getting one’s way after being treated unfairly by his or her supervisor, the most “effective” way to manage the situation would be to defend one’s position in front of the supervisor regardless of possible ramifications . In contrast, if one is aiming at a more long-term goal, such as to preserve a good relationship with the boss, the person may accept what is perceived as an unfair treatment and try to “let it go” (Fiori et al., 2014 ).

Scholars who have introduced ability EI measures have attempted to address these difficulties by implementing one of these three strategies to find a correct answer: (a) judge whether an answer is correct according to the extent to which it overlaps with the answer provided by the majority of respondents, also called the consensus scoring ; (b) identify correctness according to the choice provided by a pool of emotion experts, or expert scoring ; and (c) identify whether an answer is correct according to the principles of emotion theories, or theoretical scoring . The consensus scoring was introduced by Mayer et al. ( 1999 ) as a scoring option for the MSCEIT, based on the idea that emotions are genetically determined and shared by all human beings and that, for this reason, the answer chosen by the majority of people can be taken as the correct way to experience emotions. Unfortunately, this logic appears profoundly faulty once one realizes that answers chosen by the majority of people are by definition easy to endorse and that tests based on this logic are not challenging enough for individuals with average or above average EI (for a thorough explanation of this measurement issue, see Fiori et al., 2014 ).

Furthermore, what the majority of people say about emotions may simply reflect lay theories, which, although shared by most, can still be incorrect. The ability to spot a fake smile is a good example of this effect. This task is challenging for all but a restricted group of emotion experts (Maul, 2012 ). In this case, the “correct” answer should be modeled on the few that can spot fake emotions, not on the modal answer in the general population. In fact, the emotionally intelligent “prototype” should be among the very few that can spot fake emotions, rather than among the vast majority of people that get them wrong. Thus, from a conceptual point of view, it would make better sense to score test takers’ responses with respect to a group of emotion experts (high EI individuals ), as long as items reflect differences between typical individuals and those that are higher than the norm (Fiori et al., 2014 ). Items for which the opinion of experts is very close to that of common people should be discarded in testing EI abilities, because they would not be difficult enough to discriminate among individuals with different levels of EI.

Finally, scoring grounded in emotion theories offers a valuable alternative, as it allows setting item difficulties and response options in correspondence with theory-informed emotion processes (Schlegel, 2016 ). Some of the recently developed ability EI tests have utilized this approach. For example, response options on the STEM-B (Allen et al., 2015 ) and MEMA (MacCann et al., 2016 ) map onto the various emotion regulation strategies outlined in Gross’ ( 1998 ) process model of emotion regulation. Based on this theory, certain strategies (e.g., positive reappraisal, direct modification) would be more adaptive than others (e.g., emotion suppression, avoidance), and the correct responses on the ability EI items can be set accordingly. However, this too may appear to be a “subjective” criterion because of the differences among theories regarding what is deemed the adaptive way to experience, label, and regulate emotions. For example, suppression is regarded as a deleterious strategy to manage emotions because of its negative long-term effects (Gross, 1998 ). However, evidence suggests (Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Westphal, & Coifman, 2004 ; Matsumoto et al., 2008 ) that the damaging effect of suppressing emotions may depend on how this strategy fits with the social and cultural contexts, as also discussed earlier in the example of the relational conflict. Moreover, there are systematic differences across cultures in how emotions are to be expressed, understood, and regulated “intelligently” (see Huynh, Oakes, & Grossman, Chap. 5 , this volume), which poses additional challenges for developing an unbiased scoring system for ability EI tests.

Self- vs. Other-Related EI Abilities

Another issue that has not received much attention in the literature and that might explain why ability EI contributions in predicting outcomes are limited refers to the fact that ability EI theorization, in particular Mayer and Salovey’s ( 1997 ) four-branch model, blurs the distinction between emotional abilities that refer to the self with those that refer to others (e.g., perceiving emotions in oneself vs. in others, understanding what one is feeling vs. someone else is feeling, etc.), as if using the abilities for perceiving/understanding/managing emotions in oneself would automatically entail using these abilities successfully with others. However, being good at understanding one’s own emotional reactions does not automatically entail being able to understand others’ emotional reactions (and vice versa). There is some intuitive evidence: some professionals (e.g., emotion experts, psychologists) may be very good at understanding their patients’ emotional reactions, but not as good at understanding their own emotional reactions. Further, scientific evidence also exists : knowledge about the self seems to be processed in a distinctive way compared to social knowledge. For example, brain imaging studies show that taking the self-perspective or the perspective of someone else activates partially different neural mechanisms and brain regions (David et al., 2006 ; Vogeley et al., 2001 ).

The most important implication of considering the two sets of abilities (e.g., employed for oneself or with respect to others) as distinct rather than equivalent is that each of them might predict different outcomes. Recent evidence comes from a program evaluation study of an EI training program for teachers investigating the mechanisms by which EI skills are learned (described in Vesely-Maillefer & Saklofske, Chap. 14 , this volume). Preliminary results showed differential perceived outcomes in self- versus other-related EI skills , dependent on which ones were taught and practiced. Specifically, practice of self-relevant EI skills was the primary focus of the program, and these were perceived to have increased by the program’s end more than the other-related EI skills (Vesely-Maillefer, 2015 ).

It is worth noting that some recently introduced measures of EI make the explicit distinction between the self- and other-oriented domains of abilities. For instance, the Profile of Emotional Competence (PEC; Brasseur, Grégoire, Bourdu, & Mikolajczak, 2013 ) is a trait EI questionnaire that distinguishes between intrapersonal and interpersonal EI competences, and the Genos emotional intelligence test (Gignac, 2008 ) measures awareness and management of emotions in both self and others separately. Additionally, a new ability EI test currently under development at the University of Geneva, the Geneva Emotional Competence Test (Mortillaro & Schlegel), distinguishes between emotion regulation in oneself (emotion regulation) and in others (emotion management). The adoption of these more precise operationalizations of self- and other-related EI abilities would allow collecting “cleaner” validity data for the ability EI construct.

Conscious vs. Automatic Processes

Among the most compelling theoretical challenges EI researchers need to address is to understand the extent to which ability EI depends on conscious versus automatic processes (Fiori, 2009 ). Most ability EI research, if not all, has dealt with the investigation of how individuals thoughtfully reason about their own and others’ emotional experience by consciously feeling, understanding, regulating, and recognizing emotions. However, a large portion of emotional behavior is, in fact, not conscious (Feldman Barrett, Niedenthal, & Winkielman, 2005 ). For example, individuals may process emotional signals, such as nonverbal emotional behavior, without having any hint of conscious perception (Tamietto & de Gelder, 2010 ). Applied to the domain of ability EI, this implies that individuals may be able to use emotions intelligently even without being aware of how they do it and/or without even realizing that they are doing it. Research on cognitive biases in emotional disorders supports this idea: systematic errors in the automatic processing of emotion information have been causally implicated in vulnerability for mood and anxiety disorders (Mathews & MacLeod, 2005 ).

EI scholars need to acknowledge the automaticity component of ability EI, first, because it is theoretically relevant and second, because it might explain additional variance in emotionally intelligent behavior due to subconscious or unconscious processes that have been ignored to date. Some contributions have provided conceptual models (Fiori, 2009 ) and raised theoretical issues (Ybarra, Kross, & Sanchez-Burks, 2014 ) that would help to move forward in this direction. Evidence-based research is the next step and would require scholars to employ experimental paradigms in which the level of emotional consciousness is manipulated in order to observe its effects on emotionally intelligent behavior.

New Developments and Future Directions

The domain of research on ability EI is in its early developmental stage, and there is still much to explore, both on the theoretical and the measurement side. The seminal four-branch model introduced by Mayer and Salovey ( 1997 ) needs to be further developed and refined on the basis of the most recent research findings. As mentioned above, the model of ability EI as composed of four hierarchically related branches underlying a latent global EI factor does not seem to be supported, at least in its original formulation (e.g., Fiori & Antonakis, 2011 ; Rossen et al., 2008 ). On the measurement side, it seems as if progress has been made in terms of introducing new tests to measure specific EI abilities. A further step is to clarify what exactly scores on these tests are measuring and what mechanisms account for test performance. For instance, in the past the possibility was raised that individuals high in EI might be overly sensitive to emotions felt by themselves and by others in a way that could in certain circumstances compromise their health (e.g., Ciarrochi et al., 2002 ) and social effectiveness (Antonakis et al., 2009 ). Recent empirical evidence (Fiori & Ortony, 2016 ) showed that indeed high EI individuals were more strongly affected by incidental anger in forming impressions of an ambiguous target (study 1) and that they amplified the importance of emotion information, which affected their social perception (study 2). This characteristic associated with being high in EI was called “hypersensitivity ,” and it was deemed to have either positive or negative effects depending on the context (Fiori & Ortony, 2016 ).

Further investigation should also clarify which aspects of ability EI may be missing in current measurement and theorization. Ability EI tests, including the second generation, show moderate correlations with measures of intelligence, a finding that supports the conceptualization of EI as a form of intelligence. Interestingly, the component of intelligence most strongly correlated with measures of EI abilities – particularly the strategic branches of understanding and managing – is crystallized intelligence , or g c (Farrelly & Austin, 2007 ; MacCann, 2010 ; Mayer, Roberts, & Barsade, 2008 ; Roberts et al., 2006 , 2008 ), which suggests that current tests represent especially the acquired knowledge about emotions people possess. Indeed, items of the STEU and the STEM (as well as most items of the MSCEIT) require respondents to identify the best strategy to cope with emotionally involving situations described in a short vignette or to understand the emotion one would feel in a hypothetical scenario. Individuals may correctly answer such items relying on what they know about emotions, leaving open the question of whether they would be able to apply that knowledge in novel situations. For instance, individuals with Asperger’s syndrome undertaking ability EI training improved their EI scores while still lacking fundamental interpersonal skills (Montgomery, McCrimmon, Schwean, & Saklosfke, 2010 ). All in all, it appears that the STEU and the STEM measure performance in hypothetical situations, rather than actual performance, the former being more dependent on the declarative knowledge individuals possess about emotions (Fiori, 2009 ; Fiori & Antonakis, 2012 ). Tests employed to measure emotion recognition ability (e.g., JACBART) are not based on hypothetical scenarios but on pictures or videos of individuals showing emotions. Although these tests require the use of perceptual skills – differently from the tests of strategic EI abilities – they still show a significant association with g c although to a lesser extent (Roberts et al., 2006 ). Indeed, individuals may rely on the knowledge they possess of how emotions are expressed to correctly identify emotions.

At the same time, ability EI measures show little associations with emotion-processing tasks that are more strongly related to the fluid component of intelligence, or g f , such as inspection time and selective attention to emotional stimuli (Farrelly & Austin, 2007 ; Fiori & Antonakis, 2012 ). For example, Fiori and Antonakis ( 2012 ) examined predictors of performance on a selective attention task requiring participants to ignore distracting emotion information. Results showed that fluid intelligence and the personality trait of openness predicted faster correct answers on the attentional task. Interestingly, none of the ability EI test facets (as measured with the MSCEIT) predicted performance, suggesting that the MSCEIT taps into something different from emotion information processing . Austin ( 2010 ) examined the associations of the STEU and the STEM with inspection time on an emotion perception task and found no relations for the STEM. The STEU scores predicted inspection time only at intermediate and long stimulus durations, but not at very brief exposures requiring rapid processing of the stimuli, suggesting that the STEU captures conscious rather than preconscious emotion information processing. MacCann, Pearce, and Roberts ( 2011 ) looked at the associations of the strategic EI abilities (measured with the STEU and STEM), fluid and crystallized intelligence , and emotion recognition tasks based on processing of visual and auditory emotional stimuli. Their results revealed an ability EI factor distinct from g, but with some subcomponents more strongly related to g f (particularly those involving visual perception of emotional stimuli ) and others to g c (those concerning strategic abilities and the auditory perception of emotional stimuli). This study suggested the presence of potentially distinct subcomponents of fluid and crystallized ability EI, although the authors did not investigate this possibility (MacCann et al., 2011 ).

The association between current ability EI tests and emotion-information processing tasks has not been systematically addressed in the literature and deserves further investigation. In fact, it is expected that high-EI individuals would have wider emotion knowledge but also stronger emotion-processing abilities in dealing with emotional stimuli, both accounting for how individuals perform in emotionally charged situations and each predicting distinct portions of emotionally intelligent behavior. The identification of a component of ability EI that is not (fully) captured by current tests is important because it would reveal an aspect of EI that is not measured (and therefore omitted) in current research. Yet, such a component may be relevant to predicting emotionally intelligent behavior. For example, Ortony, Revelle, and Zinbarg ( 2008 ), in making the case as to why ability EI would need a fluid , experiential component, cite the case of intelligent machines, which, on the basis of algorithmic processes, would be able to perform well on the ability EI test even without being able to experience any emotion. This example highlights the importance of measuring factors associated with emotional experience and the processing of emotion information, beyond emotion knowledge, which would be better captured by bottom-up processes generated by the encoding and treatment of emotion information.

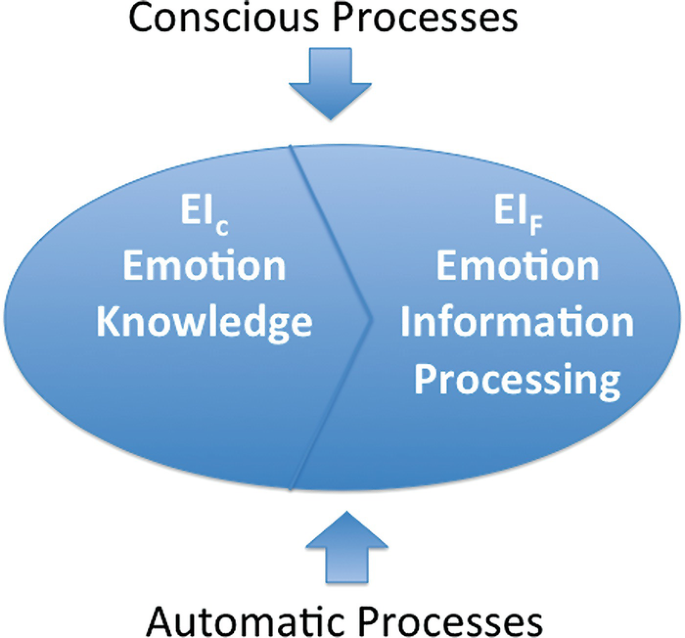

In sum, research suggests that within a broad conceptualization of ability EI as a unique construct, there might be two distinct components : one related to top-down, higher-order reasoning about emotions, depending more strongly on acquired and culture-bound knowledge about emotions, hereafter named the crystallized component of ability EI (EI c , or emotion knowledge ), and another based on bottom-up perceptual responses to emotion information, requiring fast processing and hereafter named the fluid component of ability EI (EI f , or emotion information processing ) (see Fig. 2.2 ).

Conceptualization of ability EI as composed of a fluid (EI f ) and crystallized (EI c ) component, both affected by conscious and automatic emotion processes

An additional way to look at the relationship between the two components underlying ability EI is by considering what might account for such differences, namely, the type of processing (conscious vs. automatic) necessary for ability EI tests. The role automatic processes might play in EI has been approached only recently (Fiori, 2009 ), and it is progressively gaining recognition and interest especially in organizational research (Walter, Cole, & Humphrey, 2011 ; Ybarra et al., 2014 ). With respect to the relationship between a crystallized and a fluid component of ability EI, it is plausible that answers to current ability EI tests strongly rely on conscious reasoning about emotions, whereas performance on emotional tasks, such as inspection time and fast categorization of emotional stimuli, for example, relies more on automatic processing. This may be the case as individuals in the latter tasks provide answers without being fully aware of what drives their responses. Thus, current ability EI tests and emotion information processing tasks may be tapping into different ways of processing emotion information (conscious vs. automatic; see also Fiori, 2009 ). The extent to which current ability EI tests depend on controlled processes and are affected by cognitive load is still unaddressed (Ybarra et al., 2014 ). Given that no task is process pure (Jacoby, 1991 ), both controlled and automatic processes are likely to account for responses in current ability EI tests. However, such tests require great effort and deep reasoning about emotions and thus likely tap mostly into controlled processes.

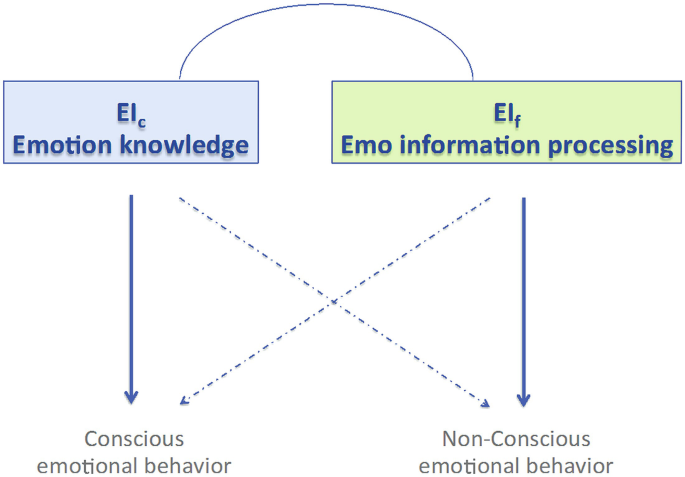

The most important implication of the engagement of two types of processing in ability EI is that each of them may predict a different type of emotional performance. More specifically, ability EI tests that rely more on emotion knowledge or the crystallized component of EI may be more suited to predict effortful and consciously accessible emotional behavior, whereas tasks meant to “catch the mind in action” (Robinson & Neighbors, 2006 ), such as those based on emotion information processing , may account mostly for spontaneous and unintentional behavior . If this is the case, then current ability EI tests may predict to a greater extent consciously accessible performance and to a lower extent emotionally intelligent behaviors that depend on spontaneous/automatic processing (Fiori, 2009 ; Fiori & Antonakis, 2012 ). The hypothesized relationship is illustrated in Fig. 2.3 .

Hypothesized effects of the fluid (EI f ) and crystallized (EI c ) ability EI components on emotional behavior

The next generation of ability EI tests will hopefully incorporate more recent theoretical advancements related to additional components of EI – such as sub- or unconscious processes or the fluid , emotion-information processing component of EI. Some may ask how the perfect measure would look like. Knowing that EI is a complex construct, it seems unlikely that “one perfect” measure that would capture all the different components of EI is in the near future. It may be more realistic to aim for “several good” measures of EI, each of them capturing key aspects of this construct with satisfactory reliability and validity. Despite some noted theoretical and practical gaps in the current literature on ability EI, the construct of EI is still in its developmental stages. With increasing interest in EI’s potential for real-world applications and its growing literature, this domain of research provides a challenging yet exciting opportunity for innovative researchers.

Change history

31 december 2019.

Chapter 2 of this book has been converted to open access and the copyright holder has been changed to ‘The Author(s)’.The book has also been updated with these changes.

Alessandri, G., Vecchione, M., & Caprara, G. V. (2015). Assessment of regulatory emotional self-efficacy beliefs: A review of the status of the art and some suggestions to move the field forward. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 33 (1), 24–32.

Google Scholar

Allen, V., Rahman, N., Weissman, A., MacCann, C., Lewis, C., & Roberts, R. D. (2015). The Situational Test of Emotional Management–Brief (STEM-B): Development and validation using item response theory and latent class analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 81 , 195–200.

Antonakis, J., Ashkanasy, N. M., & Dasborough, M. T. (2009). Does leadership need emotional intelligence? The Leadership Quarterly, 20 (2), 247–261.

Austin, E. J. (2010). Measurement of ability emotional intelligence: Results for two new tests. British Journal of Psychology, 101 (3), 563–578.

PubMed Google Scholar

Austin, E. J., Saklofske, D. H., & Egan, V. (2005). Personality, well-being and health correlates of trait emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 38 , 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.009

Article Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Bänziger, T., Grandjean, D., & Scherer, K. R. (2009). Emotion recognition from expressions in face, voice, and body: The Multimodal Emotion Recognition Test (MERT). Emotion, 9 , 691–704.

Bar-On, R. (2006). The Bar-On model of Emotional-Social Intelligence (ESI). Psicothema, 18 , 13–25.

Bonanno, G. A., Papa, A., Lalande, K., Westphal, M., & Coifman, K. (2004). The importance of being flexible: The ability to both enhance and suppress emotional expression predicts long-term adjustment. Psychological Science, 15 (7), 482–487.

Bower, G. H. (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36 , 129–148.

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., & Salovey, P. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5 , 88–103.

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., Shiffman, S., Lerner, N., & Salovey, P. (2006). Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: A comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91 , 780–795. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.780

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brackett, M. A., Warner, R. M., & Bosco, J. S. (2005). Emotional intelligence and relationship quality among couples. Personal Relationships, 12 , 197–212.

Brasseur, S., Grégoire, J., Bourdu, R., & Mikolajczak, M. (2013). The profile of emotional competence (PEC): Development and validation of a self-reported measure that fits dimensions of emotional competence theory. PLoS One, 8 (5), e62635.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Burrus, J., Betnacourt, A., Holtzman, S., Minsky, J., MacCann, C., & Roberts, R. D. (2012). Emotional intelligence relates to wellbeing: Evidence from the situational judgment test of emotional management. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being, 4 , 151–166.

Ciarrochi, J. V., Chan, A. Y. C., & Caputi, P. (2000). A critical evaluation of the emotional intelligence construct. Personality and Individual Differences, 28 , 539–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00119-1

Ciarrochi, J., Deane, F. P., & Anderson, S. (2002). Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between stress and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 32 (2), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00012-5

Cooper, R. K., & Sawaf, A. (1997). Executive EQ: Emotional intelligence in leadership and organizations . New York: Grosset/Putnam.

Côté, S., & Miners, C. T. (2006). Emotional intelligence, cognitive intelligence, and job performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51 (1), 1–28.

Côte, S., Lopes, P. N., Salovey, P., & Miners, C. T. H. (2010). Emotional intelligence and leadership emergence in small groups. The Leadership Quarterly, 21 , 496–508.

David, N., Bewernick, B. H., Cohen, M. X., Newen, A., Lux, S., Fink, G. R., … Vogeley, K. (2006). Neural representations of self versus other: Visual-spatial perspective taking and agency in a virtual ball-tossing game. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18 (6), 898–910.

Davies, M., Stankov, L., & Roberts, R. D. (1998). Emotional intelligence: In search of an elusive construct. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75 , 989–1015. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.75.4.989

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82 (1), 405–432.

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., & Ancoli, S. (1980). Facial signs of emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39 (6), 1125–1134.

Fan, H., Jackson, T., Yang, X., Tang, W., & Zhang, J. (2010). The factor structure of the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test V 2.0 (MSCEIT): A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 48 (7), 781–785.

Farrelly, D., & Austin, E. J. (2007). Ability EI as an intelligence? Associations of the MSCEIT with performance on emotion processing and social tasks and with cognitive ability. Cognition and Emotion, 21 (5), 1043–1063.

Feldman-Barrett, L., Niedenthal, P. M., & Winkielman, P. (Eds.). (2005). Emotion: conscious and unconscious . New York: Guilford Press.

Fernández-Berrocal, P., & Extremera, N. (2016). Ability emotional intelligence, depression, and well-being. Emotion Review, 8 , 311–315.

Fiori, M. (2009). A new look at emotional intelligence: A dual process framework. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13 , 21–44.

Fiori, M., & Antonakis, J. (2011). The ability model of emotional intelligence: Searching for valid measures. Personality and Individual Differences, 50 , 329–334.

Fiori, M., & Antonakis, J. (2012). Selective attention to emotional stimuli: What IQ and openness do, and emotional intelligence does not. Intelligence, 40 (3), 245–254.